4. Ways to secure a load in an HGV or goods vehicle

Equipment and methods you can use to secure a load in a goods vehicle and how to use it safely.

The equipment and methods in this section are listed in alphabetical order.

You can attach load securing equipment to:

- the vehicle chassis

- the side raves

- dedicated anchorage points

Any attachment point must be strong enough to withstand the expected loads.

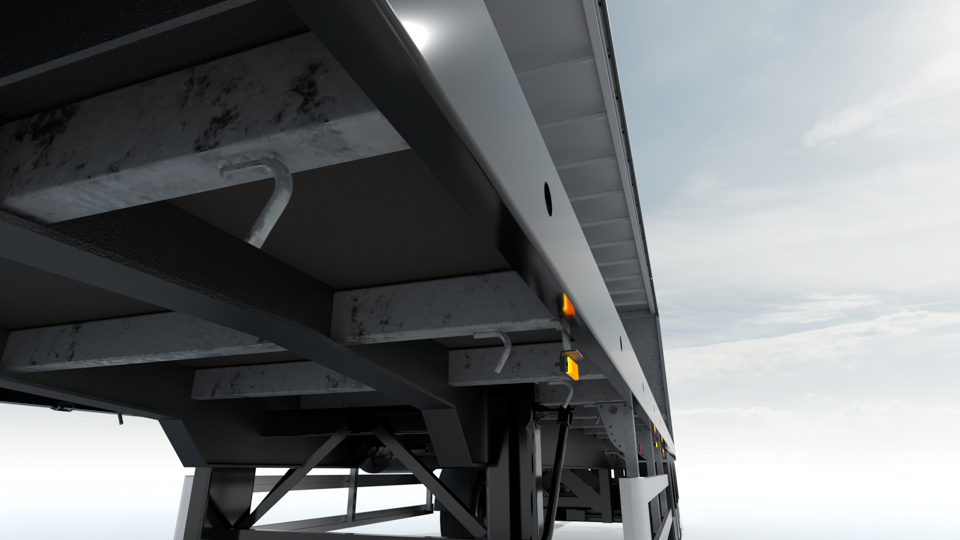

Side raves

A side rave is the steel edging of a vehicle load bed.

You can use side raves to attach securing equipment to the vehicle.

Check that the raves are compatible with the type of securing equipment you’re using.

Visually check the raves regularly for signs of:

- damage

- distortion

- corrosion

Arrange for the raves to be repaired as soon as possible if you notice any damage.

The raves may not be strong enough to use if they’re in poor condition.

Anchorage points

Check that:

- the anchorage points are compatible with the type of securing equipment you’re using

- there’s as little movement as possible in the anchorage point – restraints will not work as well if the anchorage point can move

- there are no signs of damage or distortion

You must not:

- attach more than one lashing to an anchorage point

- thread a lashing through an anchorage point and hook it back onto itself

Sheeting hooks

You should only use sheeting hooks to tie a sheet over the load to:

- cover loose loads

- protect the load from the weather

You must not use sheeting hooks or rope hooks as an anchor for straps or chains, even if they’re attached to side raves. They’re not designed for load securing.

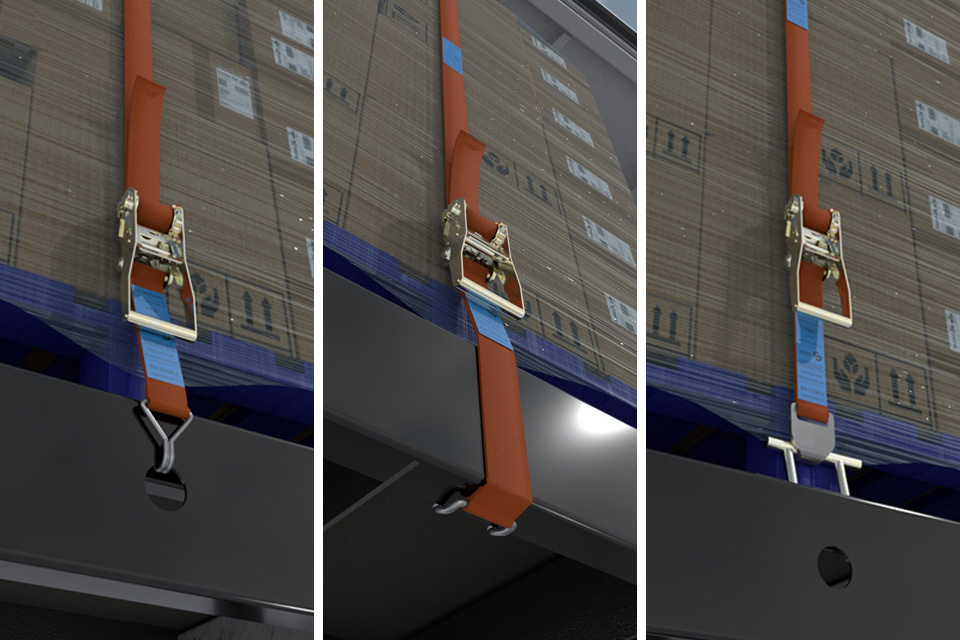

You can use buckle straps (hanging black straps) and internal nets on roof rails to contain loads on standard curtainsiders.

The individual load items or stacks being secured can weigh up to a maximum of 400kg. You must not use buckle straps and internal nets to secure items or stacks weighing over 400kg.

If the load does not fill the load bed, you should either:

- secure the last row using a ratchet strap, with the load blocked to fill the gap

- use buckle straps or an internal net to form a rear bulkhead

You can use buckle straps and internal nets as a secondary securing method in case the main securing method fails. They’re generally not as strong as other securing methods and may not be suitable for all loads.

You can use bungee securing systems and kites to secure fragile or crushable loads that might be damaged by lashing straps.

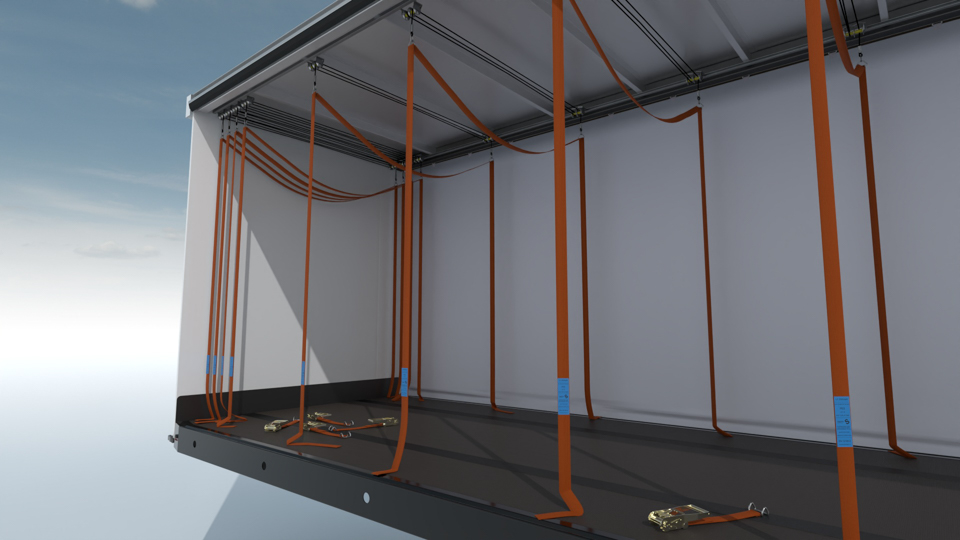

Bungee securing systems

Bungee securing systems consist of ratchet straps, nets, or sheets that are:

- held into the roof of the vehicle

- brought down over the load

- secured in the same way as a normal ratchet strap

The straps should be manufactured to BS EN 12195-2.

Although the system might be held into the roof when it’s not in use, its strength does not rely on the roof structure.

Kites

You can suspend kites vertically to reduce the effect of gaps in a load. This will stop the load moving up and down the length of the vehicle.

When deciding whether to use kites you should make sure they’re strong enough for the forces likely to be exerted on them.

Chains may be more suitable than lashing straps for some loads, as chains are usually much stronger and less vulnerable to damage.

You should:

- check the condition of the chains before using them and visually inspect them for damage on a regular basis

- store chains in a compartment or a box with a lid when they’re not being used – this protects them from environmental damage and stops them sliding or bouncing off the load bed

When you use chains to secure heavy equipment like engineering plant and machinery, you must:

- use at least 4 chains when securing it with direct lashing

- attach each chain to different points on both the equipment and the vehicle

- attach the chains to suitable attachment points to secure the load properly

Chains are only as strong as the weakest component in the restraint system. You must not:

- use a combination of straps and chains in the same lashing to secure a load – straps and chains stretch differently (often referred to as elongation properties)

- use straps as anchor points for chains

- use chains as anchor points for straps

You can stop loads moving by using:

- coil wells

- rubber, plastic, or wooden chocks

- cradles

These pieces of equipment work by providing a physical barrier to movement. You will normally need to use an additional method of securing the load, but you may not need to use as many lashings.

You may need to use wheel chocks or timbers in addition to lashings when you transport plant equipment on flatbed, lowloader, and curtainsider vehicles. Make sure that the chocks or timbers are also secured to the load bed.

You may not need to use separate chocks if the vehicles are fitted with wheel recesses or an auto-chock system.

A high friction surface can be very effective as part of a load securing system, but you must not use it by itself. You cannot rely on friction alone to secure a load.

You should use friction matting or a high-friction floor for some load types, for example paper reels or work cabins not transported on twist locks.

You can fit a high friction surface across the full load area on a vehicle, or you can use individual mats strategically under a load.

High friction surfaces increase the coefficient of friction between the load and the load bed, so you will need fewer lashings. High-friction surfaces should have a coefficient of friction of at least 0.6 to be effective.

A headboard or a bulkhead is a physical barrier. It’s generally attached directly to the vehicle between the cab and the load area, or within the load area itself.

If the vehicle has a headboard or bulkhead that is used as part of the load securing system, you must place the load in contact with the headboard or bulkhead or within 30cm of it wherever possible. This will stop the load moving forward when the vehicle brakes.

If this is not possible (for example, if it would overload an axle), you must use additional securing methods to prevent the load moving forward. You could:

- fit an obstacle, such as stacked timbers strapped to the vehicle - this effectively moves the headboard towards the back of the vehicle

- use blocks, timbers, dunnage, or chocks to prevent items moving forward - make sure that they’re properly secured to the vehicle

- use additional lashing

If you’re carrying a load in a van, you should:

- use straps secured to the vehicle body or pack any gaps between the load and the vehicle body

- load to the bulkhead between the cargo space and the cab

Loading over the headboard

Divisible loads

A divisible load is a load that can be broken down into multiple smaller parts, such as a bundle of pipes or bars.

When parts of a divisible load are higher than the headboard, you must use additional load securing methods to stop the load moving forward when the vehicle brakes.

Indivisible loads

An indivisible load is a load that cannot be broken down into smaller parts.

You should only load an indivisible load higher than the headboard if the headboard is as high as the centre of gravity of the load. This will stop the load toppling forward over the bulkhead when the vehicle brakes.

You can use lashing straps (also known as webbing ratchet straps) to secure a wide variety of loads.

They’re an effective load securing method when used correctly, but they can be damaged easily.

You must not:

- use a combination of ratchet straps and chains to secure a load – straps and chains stretch differently (often referred to as elongation properties) and one could break before the other

- use straps and chains in the same lashing – for example, you must not use a strap as an anchor point for a chain

Keeping straps in a usable condition

The webbing material is vulnerable to damage from many sources, including:

- sharp or abrasive edges

- the weather

- contamination by oil and dirt

You can keep your straps in a usable condition by using sleeves or protectors over corners and sharp or abrasive edges.

You should:

- store your straps somewhere dry and covered when they’re not being used

- use a storage box or compartment on the vehicle wherever possible

- check all straps at least every 6 months and record the condition

- look for any signs of damage on the straps before using them - you must replace any straps that are significantly damaged

- inspect any straps involved in a load shift incident – do not use them if they’re worn or damaged, even if the damage appears to be minor

The end fittings (hooks or delta fittings) are designed to withstand the forces on the strap when in use. You should replace the strap if the fittings are missing. Never tie a knot in any part of the strap that is under tension.

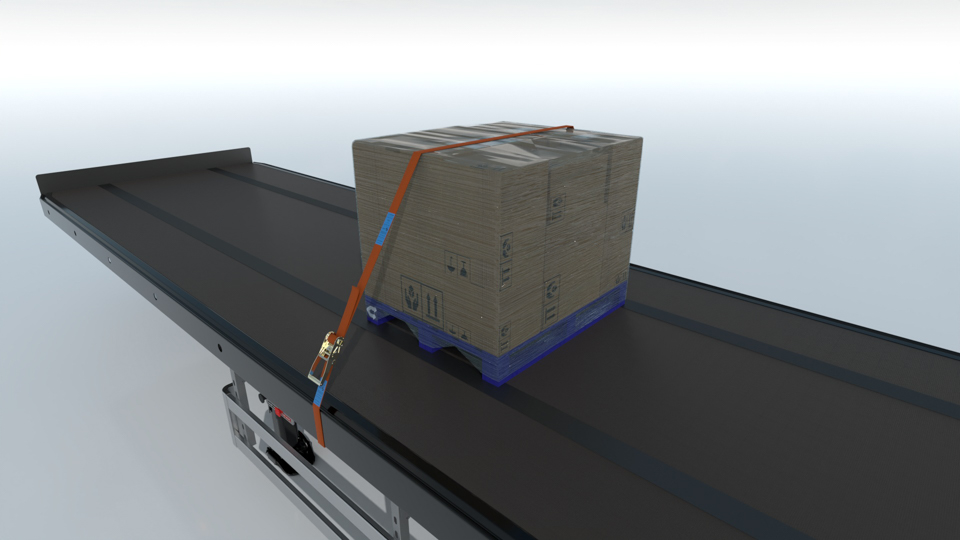

Lashing method

Lashing straps are most effective when a suitable lashing method is used.

The most common lashing methods are:

- frictional (tie-down)

- direct – where one end of the lashing is attached to the load and the other end is attached to the vehicle

- loop (choke) – where the lashing wraps around the load

Frictional lashing

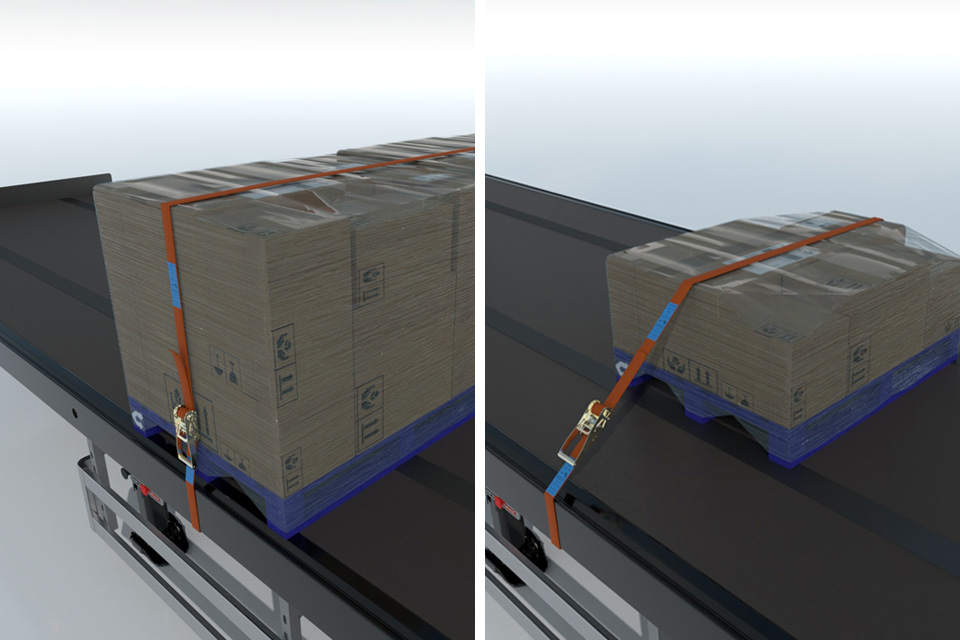

Frictional lashing is most effective when the angle of the lashing relative to the load bed is as close to vertical as possible. If the angle is less than 30°, the lashing will not be effective.

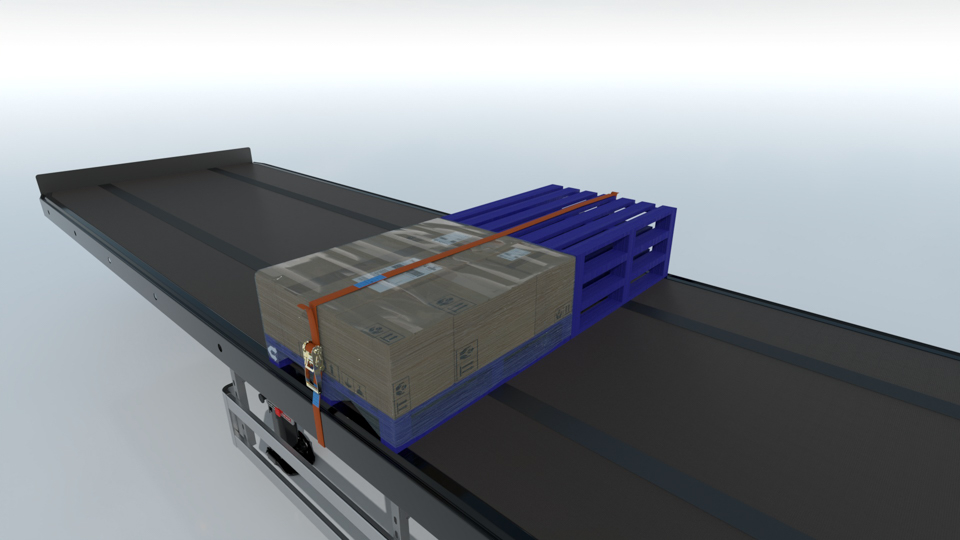

When securing a load in the middle of the load bed, or a load that is not very tall, you should either:

- increase the height of the load (for example, by placing empty pallets or other suitable item on top of it)

- change the angle of the strap using a pallet to the side

Alternatively, you could use a different method of securing.

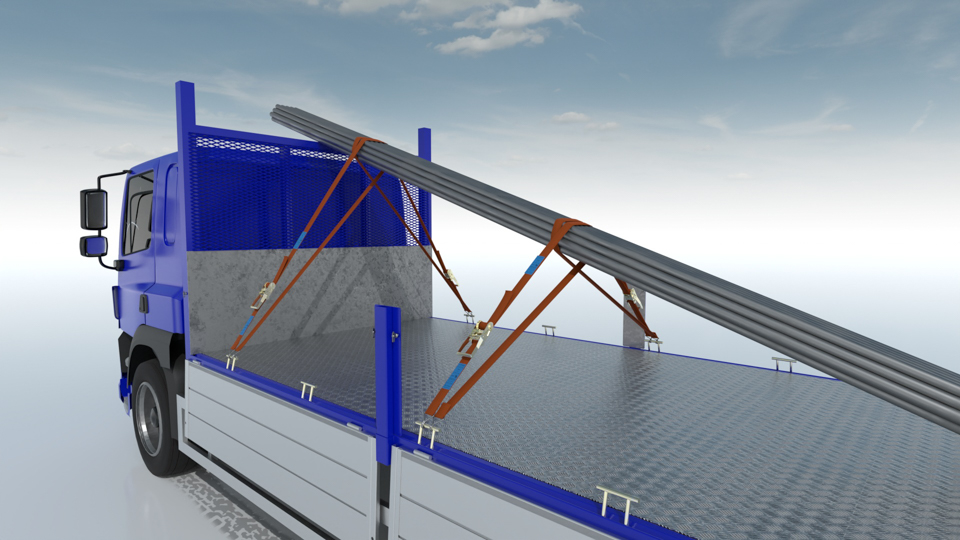

Loop (choke) lashing

You can use loop (choke) lashing for loads such as:

- wooden boards

- planks

- poles

- pipes

Loop (choke) lashing is particularly effective when these loads are carried at an angle over the headboard of a vehicle. You must use a minimum of 2 loop (choke) lashings for this type of load unless each item is individually clamped to the headboard.

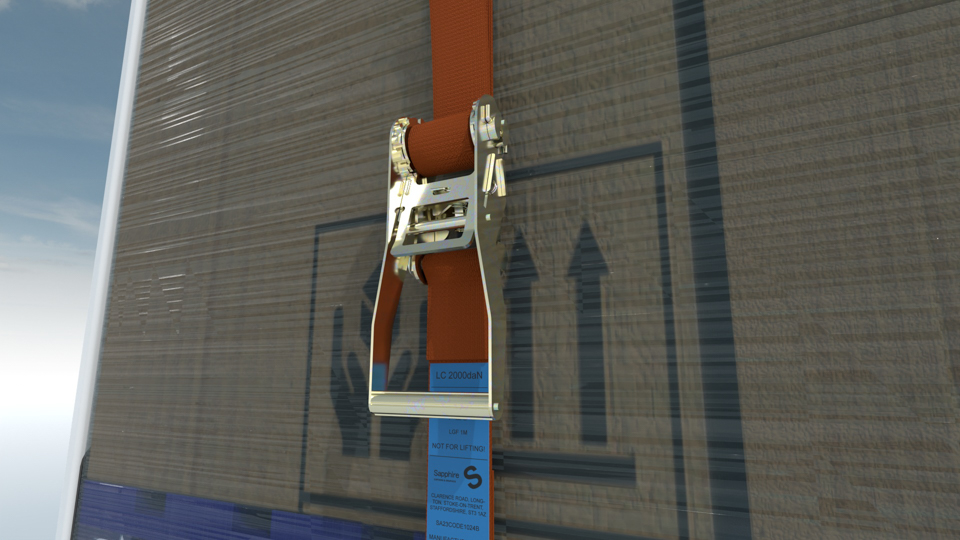

Understanding the strap label

Most ratchet straps used in the UK have a label attached to them with information about their strength and how they can be used.

Check the label to make sure you’re using the best strap for the load you want to secure. Any lashing is only as strong as its weakest component, so you need to make sure that all parts of the lashings and the attachment points are in good condition and suitable for what you intend to use them for.

Strap labels often get damaged or torn off, so it’s a good idea to keep a record of the strap rating in case you need to check it later.

The most important information on the label is the:

- lashing capacity (LC) in decaNewtons (daN)

- standard tension force (STF) in daN

Lashing capacity (LC)

The LC is the maximum force the lashing can safely withstand without damage when pulled in a straight line. It’s only used to calculate the number of lashings needed in direct lashing.

Standard tension force (STF)

The STF is the working tension in the strap created when the lashing is ratcheted down over the load. It’s only used to calculate the number of lashings needed in frictional lashing.

The number of straps needed for frictional lashing will also depend on:

- whether the load is loaded to the headboard or blocked from forward movement – you’ll need to use extra straps if there’s an uncontrolled gap of more than 30cm between the load and the headboard

- the friction between the load and the load bed

- the angle of the straps relative to the load bed

Straps used in the UK usually have an STF of 350daN or lower. For some loads, you may need to use straps with an STF of 500daN or more to reduce the number of lashings required.

Other information on the strap

The strap label should also tell you:

- when the strap was manufactured

- that it was manufactured in accordance with BS EN 12195-2

Some strap labels have a ‘breaking strength’ or ‘breaking force’, but you do not need this to work out how many straps you need to secure the load.

Ratchets

Make sure that the ratchet is locked once you’ve applied the correct tension. Depending on how much friction is needed to secure a load, it may be better to use a downward pull ratchet. This allows you to apply more pressure than an upward push ratchet.

Positive fit is a way of securing a load inside a trailer or vehicle body that’s strong enough to withstand the forces likely to be exerted on it during the journey, for example a vehicle constructed to the BS EN 12642 XL standard.

The load itself should fill the load bed with minimal gaps wherever possible.

For effective positive fit, the load must be:

- against or within 30cm of the headboard

- loaded tightly along the length without a gap or cumulative gaps of more than 30cm

- within 30cm of the rear doors

- within 8 cm of either side

If you cannot achieve this with the load alone, you can fill the gaps with:

- packing material

- dunnage

- empty pallets

- timbers

If you cannot fill the gaps, you must secure the load as in any non-XL rated vehicle.

You can achieve positive fit with cylindrical loads (such as paper reels) when the extremity of either one reel or two reels side by side is within 8cm of the side of the vehicle.

You can use rope for:

- sheeting or netting a light load to prevent it moving upwards

- attaching weather protection on loads that have already been secured

You may decide to use rope to increase safety when unloading, but it cannot be used for load securing for the journey.

Rope is not suitable for securing loads because it’s difficult to establish its load capacity and age. Ropes can also wear or deteriorate more quickly than lashing straps.

To stop items bouncing out of a vehicle (for example sided flatbeds and bulk tippers), or loose loads like sand being blown from a vehicle, you can use:

- sheets (sometimes called tarpaulins) – these are solid

- nets – these have gaps in the material, so are not suitable for all types of load

Sheets and nets are used to contain a load but not to secure it. They must only be used with other suitable measures such as lashings.

Sheets and nets used to contain a load must:

- be in good condition – there must be no rips or tears

- be suitable for the load carried

- cover the entire load bed so that no part of the load can escape

- be secured down to the vehicle so they do not come loose when the vehicle is moving

Some flatbed vehicles have a crane fitted for loading and unloading. You must not use the crane or any lifting accessories to secure a load.

If you lay down a crane, grab arm or boom over a load, you must secure it separately with lashings or a mechanical interlock.

You can use the rigid sides of a tipper if:

- the boom sits well below the vehicle sides

- it has been designed to withstand this kind of force

You could put other road users or pedestrians at risk if you do not secure the boom for travel, as it could result in uncontrolled slewing from side to side.

You must stow and lock any stabiliser legs before the start of the journey. Any alarms and sensors that monitor the position of the legs and alert the driver if there is a dangerous situation must be in working order.

Lifting equipment must be maintained and regularly inspected as required by the Lifting Operations and Lifting Equipment Regulations (LOLER). It must only be operated by people who are trained and competent to do so.