Income Dynamics: income movements and the persistence of low income, 2010 to 2019

Updated 26 August 2021

Income Dynamics (ID) presents information on changes in income over time. Its main findings relate to persistent low income. Individuals are in persistent low income if they are in relative low income for at least three out of four consecutive annual interviews. Analysis of entries into and exits from persistent low income is also included, as well as individual movements within the overall income distribution over time.

1. Main stories

The main stories are:

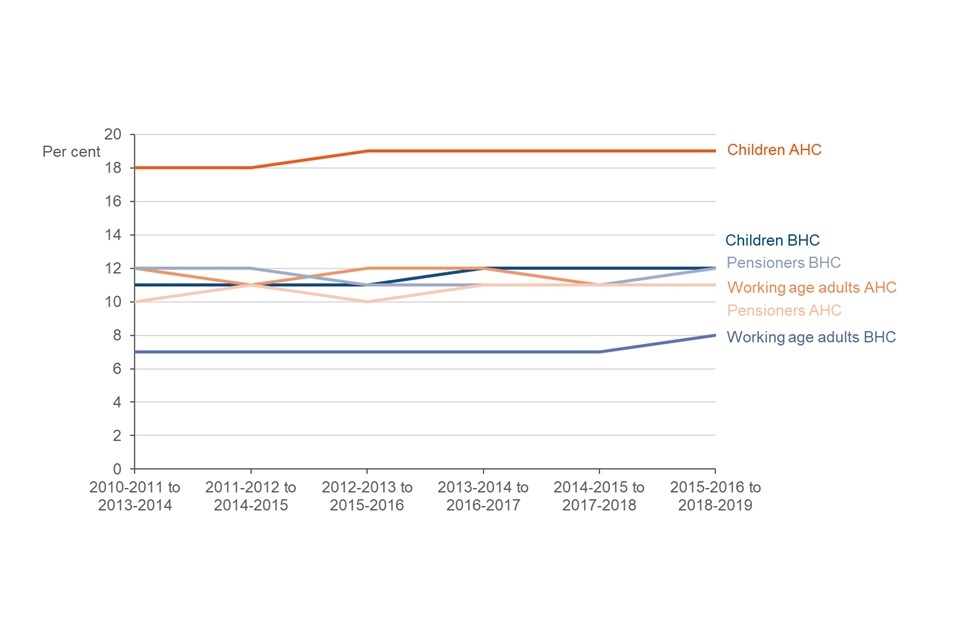

- between 2015 to 2016 and 2018 to 2019, 9% of all individuals were in persistent low income before housing costs (BHC), and 13% after housing costs (AHC). These rates have remained stable over time

- children and pensioners had higher rates of persistent low income than working-age adults BHC. AHC rates for children were considerably higher than rates for working-age adults and pensioners. Rates for individual population groups have changed little over time

- over the period 2010 to 2019, most individuals moved within the income distribution, although those in the top and bottom income quintiles in 2010 to 2011 experienced less movement than those in other income quintiles

- between 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019, roughly equivalent numbers of individuals moved into low income as moved out of low income. Analysis indicates that earnings and benefits changes, as well as changes in employment, are closely associated with these movements

2. What you need to know

This is the fifth annual statistics publication on Income Dynamics (ID). It provides data on changes in household incomes in the UK, including information on individuals in persistent low income. This publication meets DWP’s statutory obligation to publish a measure of persistent low income for children under Section 4 of the Welfare Reform and Work Act 2016. Findings on persistent low income among pensioners and working-age adults are also presented.

Persistent low income rates are lower than the single year rates published by Households Below Average Income. This is because fewer people remain in low income for three years out of four than experience low income in any single year.

Income measures

ID uses a disposable household income measure, adjusted for household size and composition, as a proxy for living standards. Statistics are routinely reported both before and after housing costs. A household is said to be in relative low income if their equivalised income is below 60% of median income. The income measures used in ID are subject to several statistical adjustments in line with international best practice. This means they may not always be directly relatable to the amounts understood by individuals on a day-to-day basis. These adjustments are necessary however, to allow us to make comparisons over time and across household compositions on a consistent basis. Please refer to Section 11 below as well as the Background information and methodology report published alongside this release.

Survey data

ID estimates are based on Understanding Society, a longitudinal survey run by the University of Essex, which follows sampled individuals over time. It has a two-year survey period (“wave”) based upon calendar years, with individuals interviewed once a year.

In 2018 to 2019, the Wave 10 longitudinal sample included over 29,000 individuals. For the purposes of this analysis, individuals are classified according to their characteristics at the first wave in the analysis. For example, where analysis covers the period between 2015 to 2016 and 2018 to 2019, working-age adults are adults who were below State Pension age (SPa) and over 16, not in further education and not classed as a dependent child, when they were interviewed for the 2015 to 2016 wave.

Use of survey data means that estimates in this report are subject to a margin of error. Care should therefore be taken in interpreting apparent change over time, which may reflect sampling error rather than real change from one year to the next. This holds particularly true over the short term and where percentage point differences are small. Percentages are rounded to the nearest percentage point independently, and as a result may not sum to 100.

Please refer to the accompanying Background information and methodology report for more information.

Additional tables

Data tables have been published alongside this release. Relevant table references are provided within the text.

3. An overview of persistent low income

Between 2015 to 2016 and 2018 to 2019 the rate of persistent low income for all individuals was 9% before housing costs (BHC) and 13% after housing costs (AHC). Both rates have remained stable throughout the series.

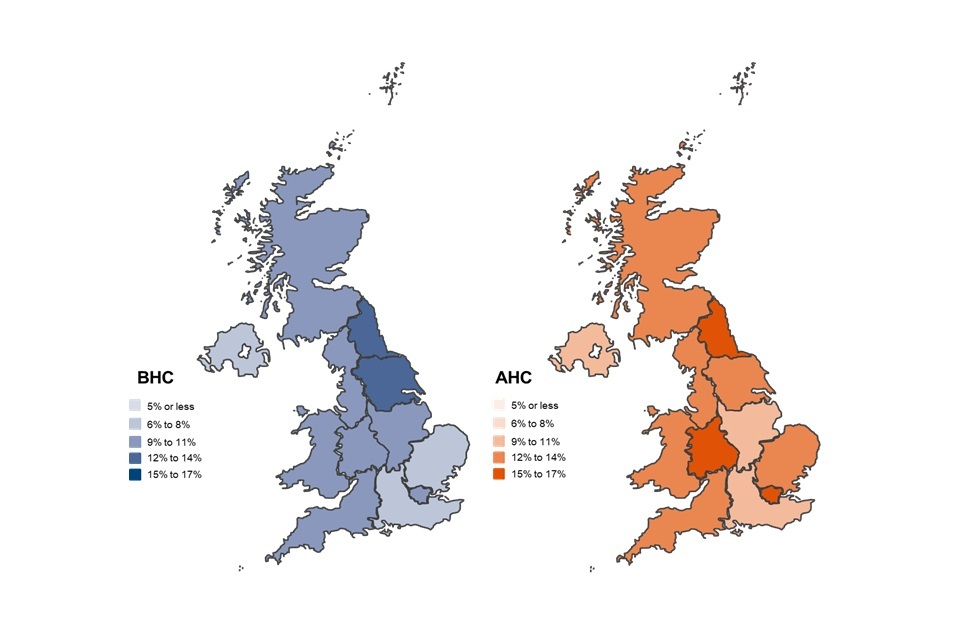

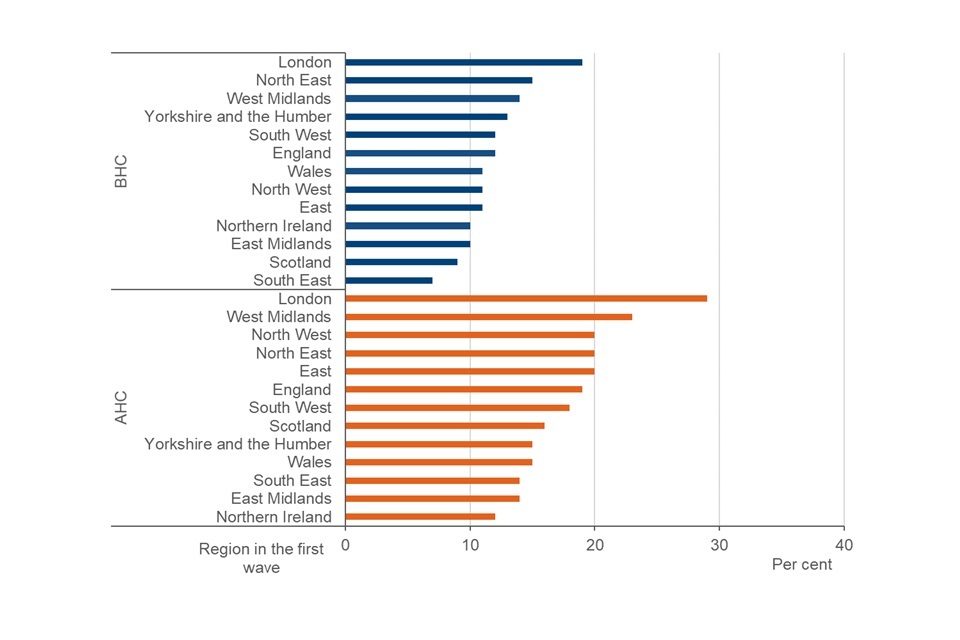

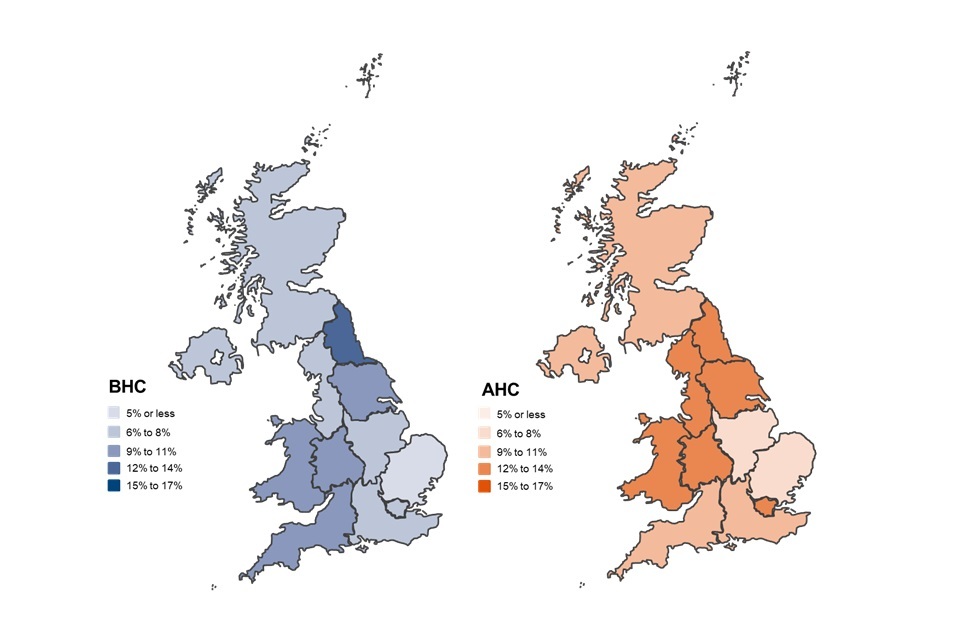

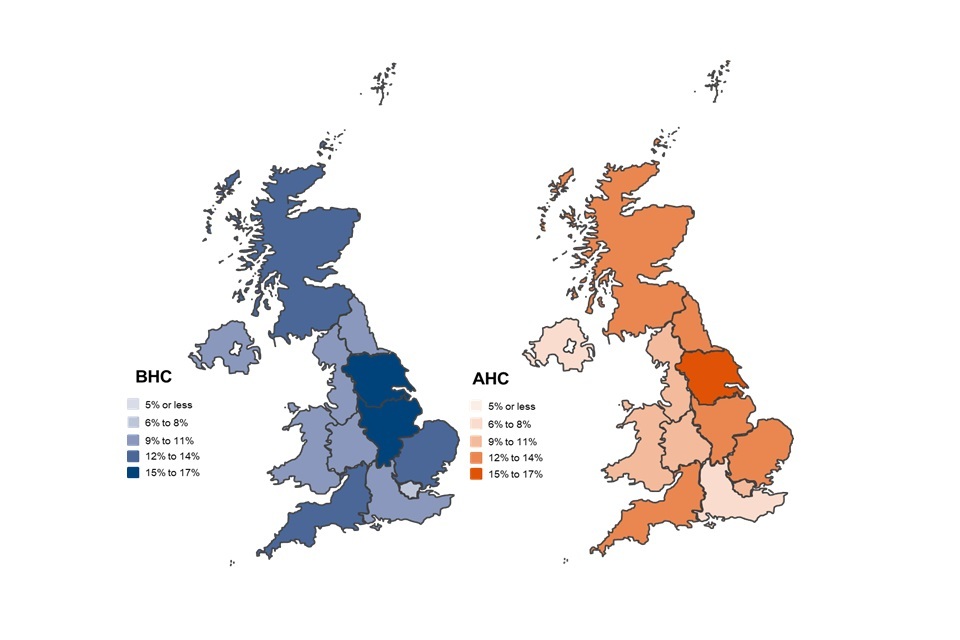

Rates of persistent low income varied across the regions and countries of the UK

Within the four countries of the United Kingdom (UK), there was little variation in the rate of persistent low income BHC, ranging from 8% to 10%. This rate has varied little over the period 2010-2019, although Wales has tended to have slightly higher rates than other countries of the UK throughout this period. Within England the highest rates of persistent low income were in the North East and Yorkshire and the Humber, both at 12%. The lowest rates of persistent low income were in the East and South East (8% and 7% respectively).

When looking at persistent low income after housing costs (AHC) across the countries of the UK, Northern Ireland had a slightly lower rate (9%) compared to the other three countries of the UK (12-13%). Within England, the regional pattern varied from that seen when looking at persistent low income BHC. While the North East again had relatively high rates of persistent low income (15%), London had the highest rate (16%), and the West Midlands also had a relatively high rate at 15%. The South East and East Midlands had the lowest rates (10% each). The higher rate seen in London is likely to reflect relatively high housing costs.

See Tables 2.2p and 2.8p for more information.

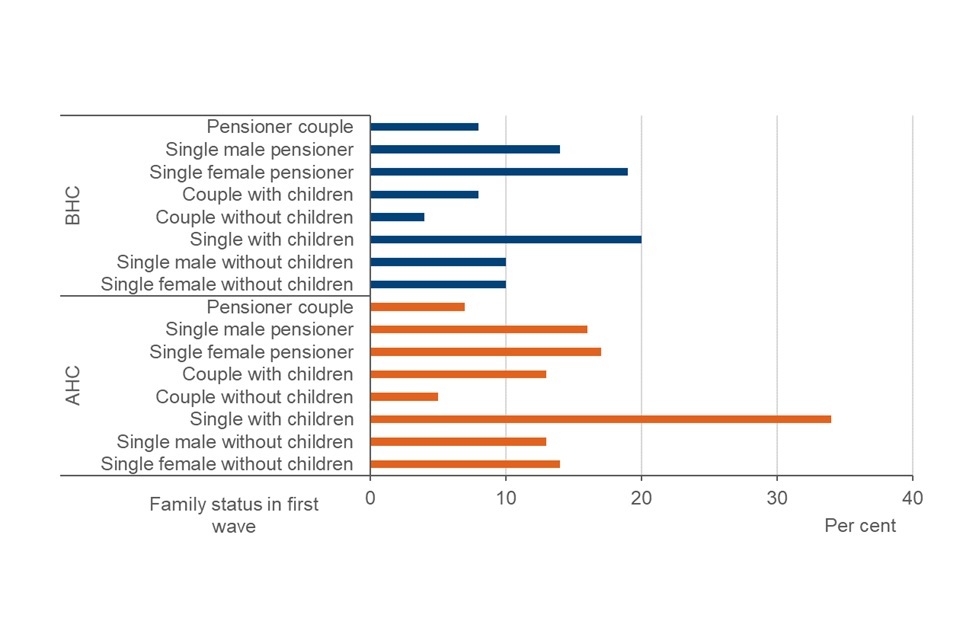

Households headed by couples tended to have lower rates of persistent low income

Couples without children had the lowest rates of persistent low income BHC (4%). Couples with children and pensioner couples also had relatively low rates of persistent low income BHC (both 8%), indicating that those living in households headed by couples benefit from the pooling of resources. This is particularly evident when comparing rates of persistent low income for couples with children (8%) to single adults with children (20%), who had the highest rates of persistent low income of all family types. Single female pensioners had a relatively high rate of persistent low income BHC (19%) compared to single male pensioners (14%).

When looking at rates of persistent low income AHC, pensioner couples and couples without children again had relatively low rates of persistent low income, at 7% and 5% respectively. Taking housing costs into account resulted in notable increases in rates of persistent low income for households with children. There was an increase to 13% for couples with children, and an increase to 34% for single adults with children. While individuals living in single parent households made up just 7% of the sample population, they represented 18% of those in persistent low income AHC.

See Tables 2.1p, 2.7p, 2.7c and 2.13c.

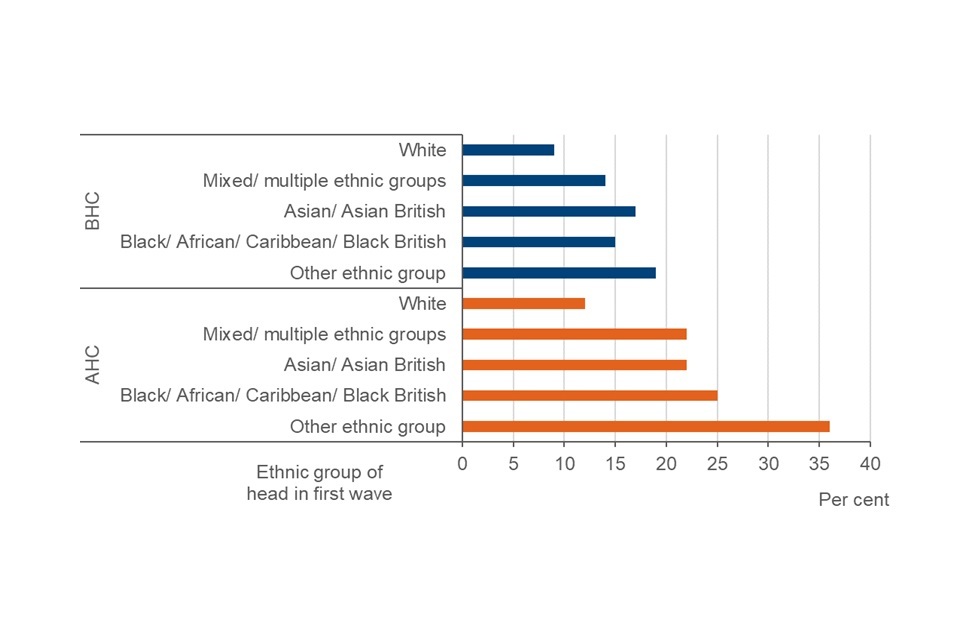

Individuals with a White head of household had lower rates of persistent low income than individuals from other ethnic groups

Individuals with a White head of household had the lowest rates of persistent low income at 9% BHC. Individuals with heads of household from the Other ethnic group had the highest rates of persistent low income BHC at 19%. Care should be taken when interpreting figures relating to the Other ethnic group due to a relatively low sample size. Individuals with an Asian/Asian British head of household had the second highest rates of persistent low income (17%) followed by those with Black/African/Caribbean/Black British heads of household (15%).

Housing costs accentuated differences in rates of persistent low income between individuals with a White head of household and those from households headed by individuals from other ethnic groups. Individuals from the White ethnic group had the lowest AHC persistent low income (12%). Those from the Other ethnic group showed the highest rates of persistent low income at 36%. Individuals from a Black, Asian or Mixed ethnic group all had persistent low income rates of between 22% and 25% AHC.

See Tables 2.1p, 2.7p, 2.13p, 2.1c and 2.7c. for more information.

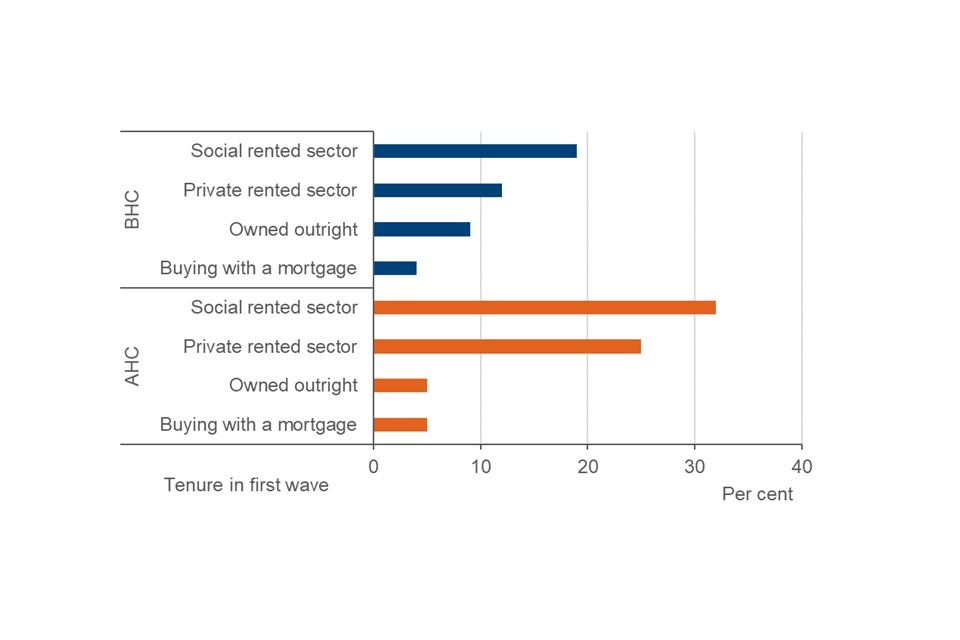

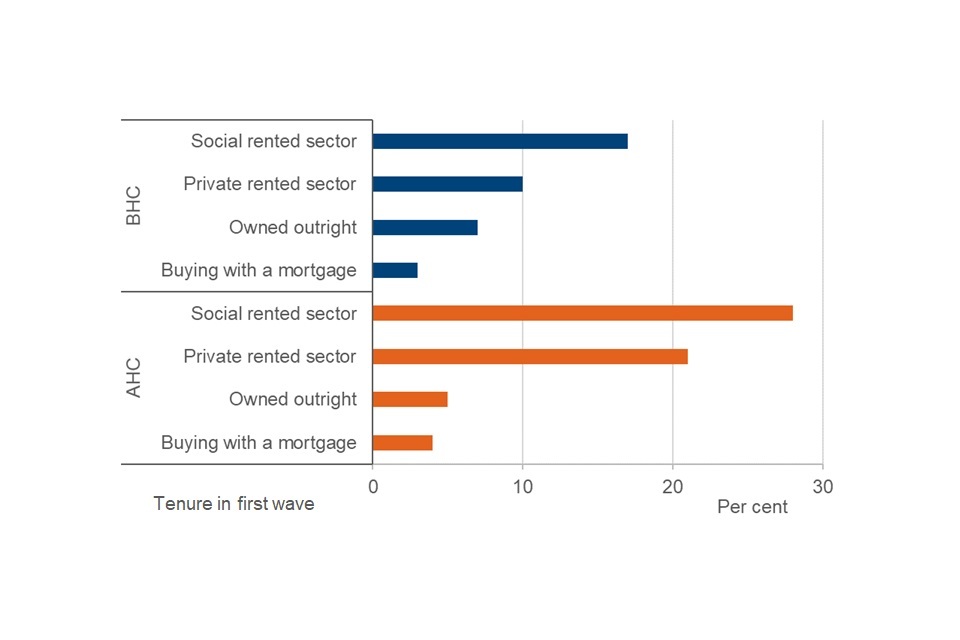

Renters had higher rates of persistent low income than non-renters

Higher rates of persistent low income BHC were seen among individuals living in the private and social rented sectors (12% and 19% respectively) compared to those who owned their homes outright (9%) and those who were buying their homes with a mortgage (4%).

The effect of housing costs on rates of persistent low income among individuals who were renting in the social and private sector resulted in notably higher rates AHC than BHC (32% and 25% respectively).

See Tables 2.2p and 2.8p for more information.

4. Children in persistent low income

Between 2015 to 2016 and 2018 to 2019, 12% of children were living in persistent low income before housing costs (BHC) and 19% after housing costs (AHC). These figures have remained relatively stable over time.

Rates of AHC persistent low income among children were higher than BHC rates across every country and region of the UK

Across the countries of the UK, the highest rates of persistent low income among children were in England, both BHC and AHC (12% and 19% respectively). Scotland had the lowest rates of persistent low income among children BHC (9%), and Northern Ireland had the lowest AHC rate (12%).

Within England, rates of persistent low income BHC ranged from 7% in the South East to 19% in London. For all regions, rates of persistent low income AHC were higher than BHC rates. The difference was most marked in London, where AHC rates of persistent low income were highest (29%). AHC rates were also notably higher than BHC rates in the North West, the West Midlands and the East. Housing costs tend to have a particularly negative effect on rates of persistent low income for children. This may be due to a number of factors such as the need for households with children to live in larger homes with higher associated costs.

See Tables 3.2p and 3.8p for more information.

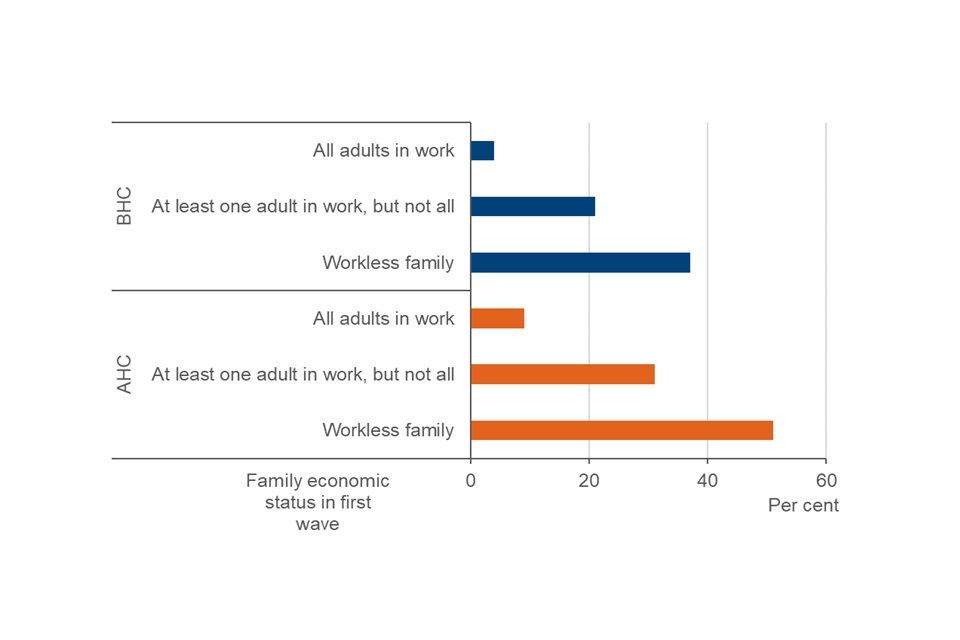

Children who lived in workless families had higher rates of persistent low income

Rates of persistent low income among children were affected by whether adults in the household were working or not: children who lived in workless families had higher rates of persistent low income both BHC and AHC (37% and 51% respectively) compared to those where all adults were in work (4% BHC and 9% AHC). Children who lived in families where at least one adult was in work but not all had lower rates of persistent low income than those in workless families, but were more likely to be in persistent low income than those where all adults were in work.

See Tables 3.1p and 3.7p for more information.

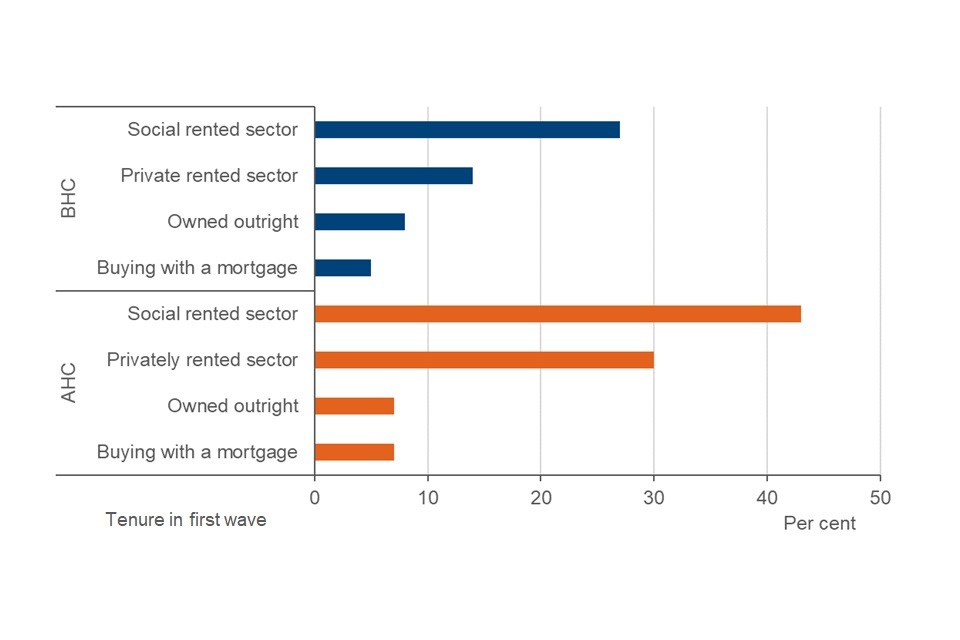

Children in rented accommodation were more likely to be in persistent low income

Children living in homes that were owned outright or were being bought with a mortgage had relatively low rates of persistent low income BHC (8% and 5% respectively). Children living in the social rented sector had the highest rates of persistent low income BHC (27%). Housing costs had a big effect on rates of persistent low income for children in rented homes.

For children living in the social rented sector, the rate of persistent low income AHC was 43%. For children in the private rented sector, the rate of persistent low income AHC (30%) was more than double the BHC rate (14%). While children living in rented homes made up 39% of children in the four-wave sample, they were over-represented among those children in persistent low income: they accounted for 71% of children in persistent low income BHC and 79% of children in persistent low income AHC.

See Tables 3.2p, 3.8p, 3.2c, 3.8c and 3.14c for more information.

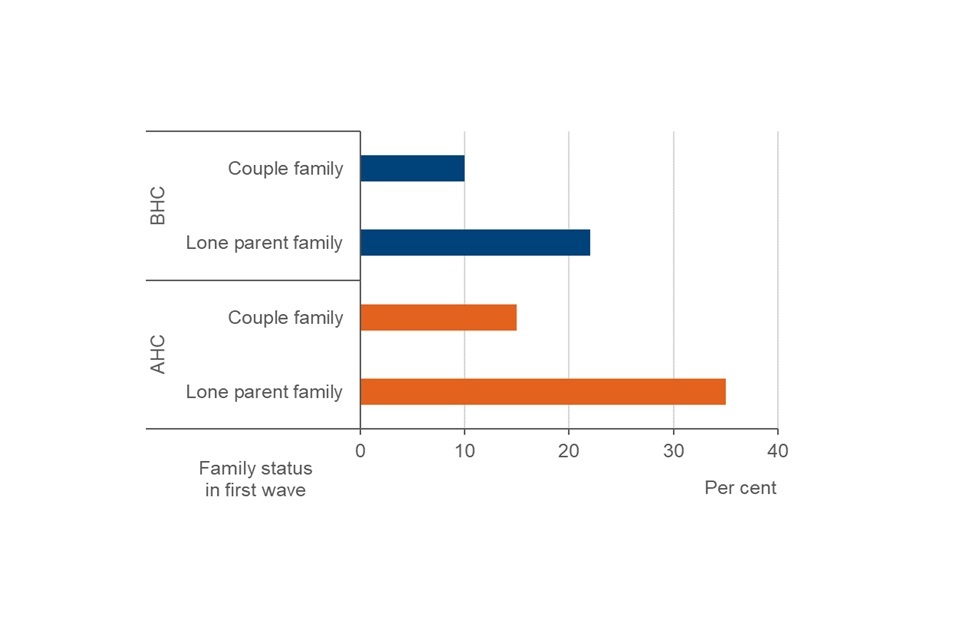

Rates of persistent low income in children were lower in families headed by couples

Children in a couple family had lower rates of persistent low income BHC, at 10% compared to children in a lone parent family where the rate of persistent low income BHC was 22%. This pattern was also evident AHC, where children in families headed by a couple had lower rates of persistent low income compared to those in lone parent families (15% and 35% respectively). While children living in lone parent families comprised 18% of the sample population, they accounted for 35% of children in persistent low income both BHC and AHC.

See Tables 3.1p, 3.7p, 3.1c, 3.7c and 3.13c for more information.

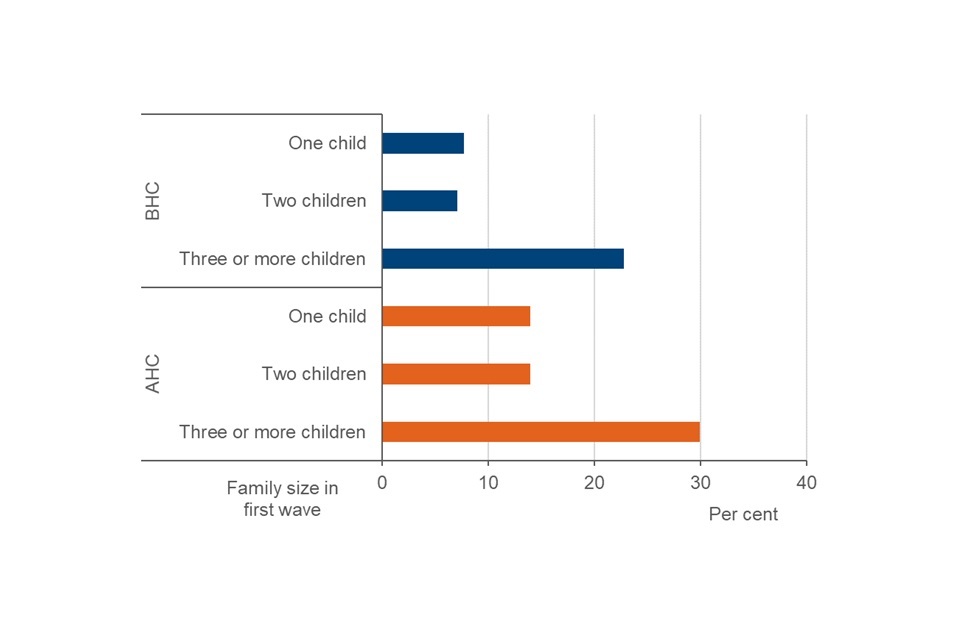

Children in families with more children were more likely to be in persistent low income than those in families with fewer children

Children in families with one or two children had BHC persistent low income rates of 8% and 7% respectively, compared to children in families with three or more children (23%). This trend was evident AHC, where children in families with one or two children had similar rates of persistent low income of 14% each, compared to 30% for children in families with three or more children. Children in families with three or more children made up 31% of the sample population, yet comprised 58% of children in persistent low income BHC and 49% AHC.

See Tables 3.1p, 3.7p, 3.1c, 3.7c and 3.13c for more information.

5. Working-age adults in persistent low income

Between the period 2015 to 2016 and 2018 to 2019, the rate of persistent low income for working-age adults was 8% before housing costs (BHC) and 11% after housing costs (AHC). This rate has been relatively stable over time.

Rates of persistent low income among working-age adults varied relatively little by country of the UK, but more by region

The rate of persistent low income BHC for working-age adults was relatively similar for the four countries of the UK, ranging from 7% in England to 9% in Wales. Within England, the North East had a higher rate of persistent low income BHC (12%), closely followed by Yorkshire and the Humber and the West Midlands, both with a rate of 10%. Lower rates of persistent low income BHC were seen in the East (5%), and in London and the South East (both 6%).

Across the four countries of the UK, rates of AHC persistent low income for working-age adults were also relatively similar, ranging from 9% in Northern Ireland, 11% in both England and Scotland, and 12% in Wales. Within England, much of the regional pattern of persistent low income BHC for working-age adults was unaltered when taking housing costs into consideration. The North East and West Midlands had higher rates of persistent low income for working-age adults (14% each), whereas the East and the East Midlands had lower rates (8% each). However, housing costs had a notable effect on rates of persistent low income in London, where the rate of persistent low income AHC was 12% compared to 6% BHC, and in the North West, where the rate of persistent low income was 12% AHC compared to 7% BHC.

See Tables 4.2p and 4.8p for more information.

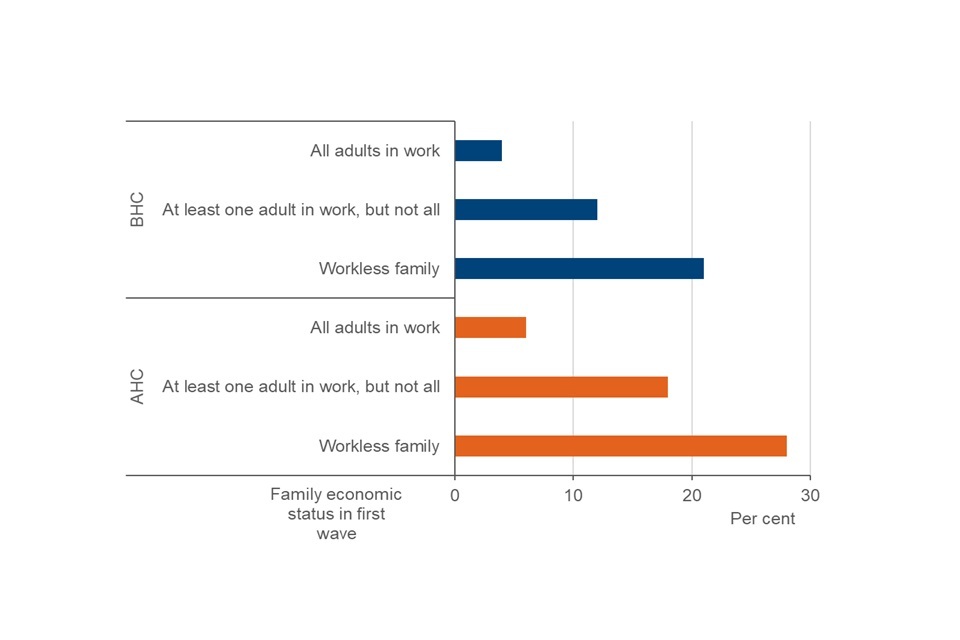

Working-age adults in workless families were more likely to be in persistent low income than those in families where someone was in work

Working-age adults in workless households had higher rates of persistent low income both BHC and AHC (21% and 28% respectively) compared to working-age adults in households where at least one adult was in work but not all (12% BHC and 18% AHC) and where all adults were in work (4% BHC and 6% AHC).

Rates of persistent low income among working-age adults where all adults are in work have remained relatively stable over time. There have been small increases in the rate of persistent low income for working-age adults where one adult is in work but not all since 2010 to 2011, and a gradual decrease in the percentage of working-age adults in workless households who are in persistent low income over the same period. The percentage of working-age adults living in workless households in successive four-wave samples has remained relatively stable over time. However, they have accounted for a decreasing share of working-age adults in persistent low income, from 60% to 44% BHC and 53% to 41% AHC since 2010 to 2011.

See Tables 4.1p, 4.7p, 4.1c, 4.7c and 4.13c for more information.

Working-age adults who rented had higher rates of persistent low income

Working-age adults who were buying their homes with a mortgage or those who owned their homes outright had the lowest rates of persistent low income BHC (3% and 7% respectively) compared to those who rented either in the social or private sectors (17% and 10% respectively).

The effect of housing costs on rates of persistent low income varied considerably by tenure: for those renting in the private sector, the rate of AHC persistent low income was 21%, double the BHC rate. Working-age adults who rented in the social rented sector also had much higher rates of persistent low income AHC than BHC, at 28%. Compared to this, rates of persistent low income for working-age adults who owned their homes outright or who were buying with a mortgage were not affected that much when housing costs were taken into account (AHC rates were 5% and 4% respectively). Although only 33% of working-age adults in our sample population rented in the private or social sector, they were over-represented among working-age adults in persistent low income (renters accounted for 62% of working-age adults in persistent low income BHC, and 75% AHC).

See Tables 4.2p, 4.8p, 4.2c, 4.8c and 4.14c for more information.

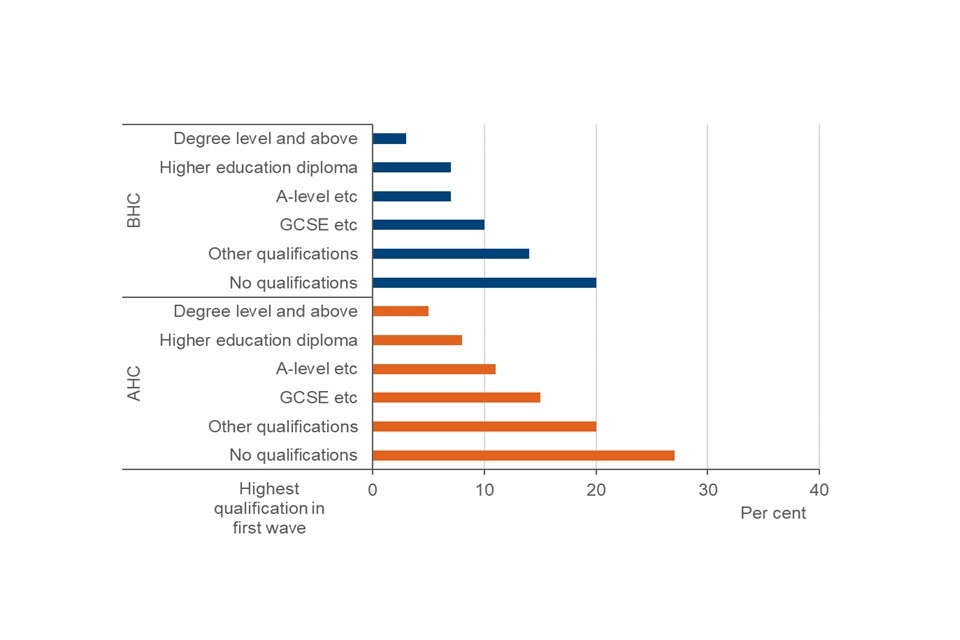

Among working-age adults, rates of persistent low income decreased with higher levels of educational qualification, both BHC and AHC

Working-age adults who had degree level qualifications had the lowest rate of persistent low income BHC (3%) and AHC (5%). Rates of persistent low income increased as level of education decreased, and working-age adults with no qualifications had the highest rates (20% BHC and 27% AHC). This is likely to be because working-age adults with higher levels of educational qualifications have access to a wider range of employment opportunities with higher pay than those with lower levels of qualifications.

See Tables 4.2p and 4.8p for more information.

6. Pensioners in persistent low income

Between the period 2015 to 2016 and 2018 to 2019, the rate of persistent low income for pensioners was 12% before housing costs (BHC) and 11% after housing costs (AHC). Both rates have varied little over time. Unlike children and working-age adults, rates of BHC and AHC persistent low income were roughly the same for pensioners. This reflects trends in tenure, with the majority of pensioners owning their homes outright.

Persistent low income varied for pensioners by region, both BHC and AHC

The four countries of the UK had similar rates of persistent low income BHC for pensioners ranging from 9% in Northern Ireland to 12% in England and in Scotland. Rates of persistent low income AHC were similar to BHC rates for all countries except Northern Ireland, where the rate of persistent low income for pensioners was 6%.

Within England, pensioners in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber had the highest rates of BHC persistent low income, at 17% and 16% respectively. BHC rates were lowest in London and the South East (7% and 9% respectively). Rates of persistent low income AHC varied from 15% in Yorkshire and the Humber to 6% in the South East.

See Tables 5.2p and 5.8p for more information.

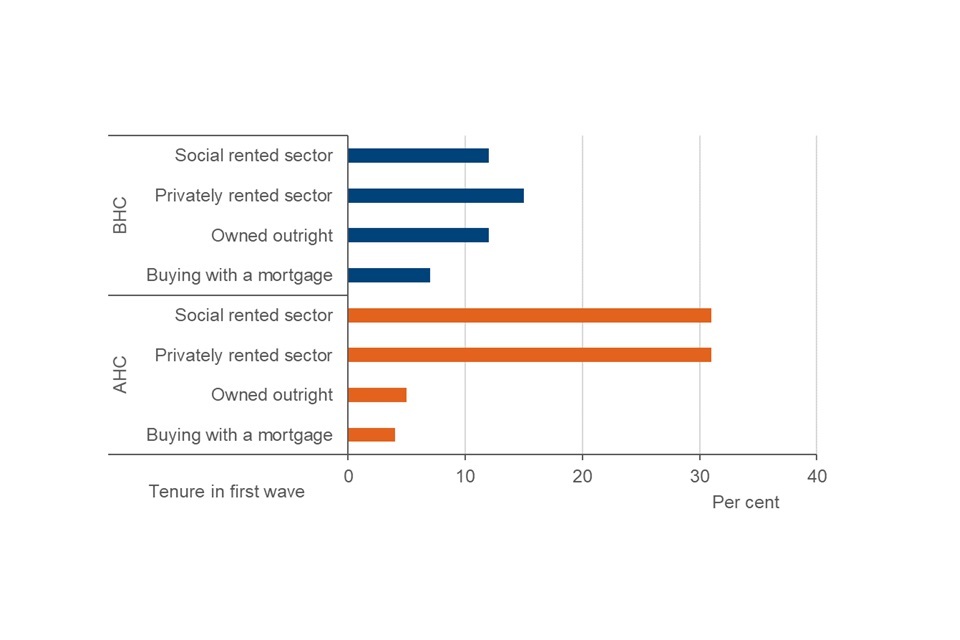

Rates of persistent low income among pensioners varied more by tenure AHC than BHC

Pensioners who were buying their homes with a mortgage had the lowest rates of persistent low income BHC of all tenures, at 7%. Pensioners who owned their homes outright had higher rates of BHC persistent low income (12%), as did those who rented in the social or private sectors (12% and 15% respectively).

The effect of housing costs on rates of persistent low income among pensioners varied considerably by tenure: those pensioners who were buying their homes with a mortgage or who owned their homes outright had much lower rates of persistent low income AHC (4% and 5% respectively) than pensioners who were renting (31% in both the private and social rented sectors). While most (72%) pensioners in the sample population owned their homes outright, and just 21% were renting, the higher rates of AHC persistent low income for pensioners who were in rented homes meant they accounted for 62% of pensioners in persistent low income AHC.

See Tables 5.2p, 5.8p, 5.8c and 5.14c for more information.

7. Long-standing illness or disability and persistent low income

Overall, working-age adults were less likely than pensioners to report having a long standing illness or disability (30% compared to 55%).

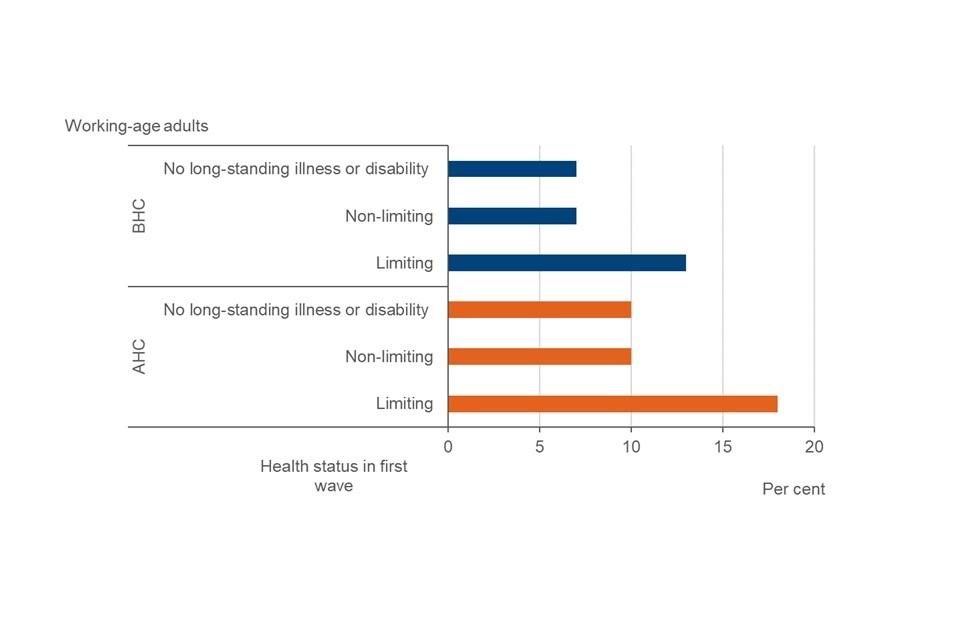

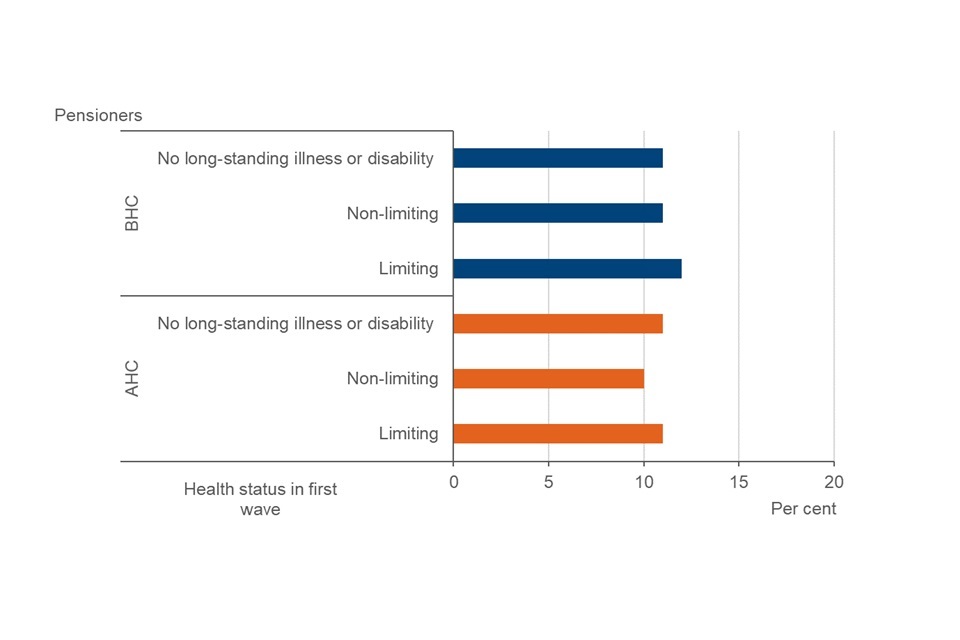

Limiting long-standing illness or disability was associated with higher rates of persistent low income for working-age adults. This pattern was not observed among pensioners

The likelihood of being in persistent low income BHC for working-age adults with a long-standing illness or disability was roughly the same as for pensioners (11% and 12% respectively). Whether that illness or disability was limiting or not made little difference to rates of BHC persistent low income for pensioners. For working-age adults however, if their illness or disability was limiting, their rate of persistent low income BHC was 13%, compared to 7% for those with a non-limiting long-standing illness or disability. This is likely to reflect the effect of having a limiting illness or disability on income from employment for working-age adults, compared to pensioners, whose income is less dependent upon employment earnings.

A similar pattern is seen across persistent low income AHC, in that whether the illness or disability was limiting or not had a greater effect on rates of persistent low income for working-age adults than for pensioners: 18% of working-age adults with a limiting long-standing illness or disability were in persistent low income AHC compared to 10% of working-age adults for whom that illness or disability was non-limiting. For pensioners, rates of persistent low income AHC were roughly the same whether that illness or disability was limiting (11%) or not (10%). For pensioners, AHC rates were also similar to BHC rates. This is likely to reflect higher levels of home ownership among pensioners which means that housing costs are less of a consideration for them.

Working-age adults with a long standing illness or disability were over-represented among working-age adults who were in persistent low income: while 18% of working-age adults in the sample population reported a long-standing limiting illness or disability, they accounted for 30% of working-age adults in persistent low income (BHC), and 29% of working-age adults in persistent low income (AHC).

See Tables 4.1p, 5.1p, 4.7p, 5.7p, 4.1c, 4.7c, 4.13c and 5.13c for more information. See also the Background information and methodology report for definitions of long-standing illness and disability and details of how this information is collected from survey respondents.

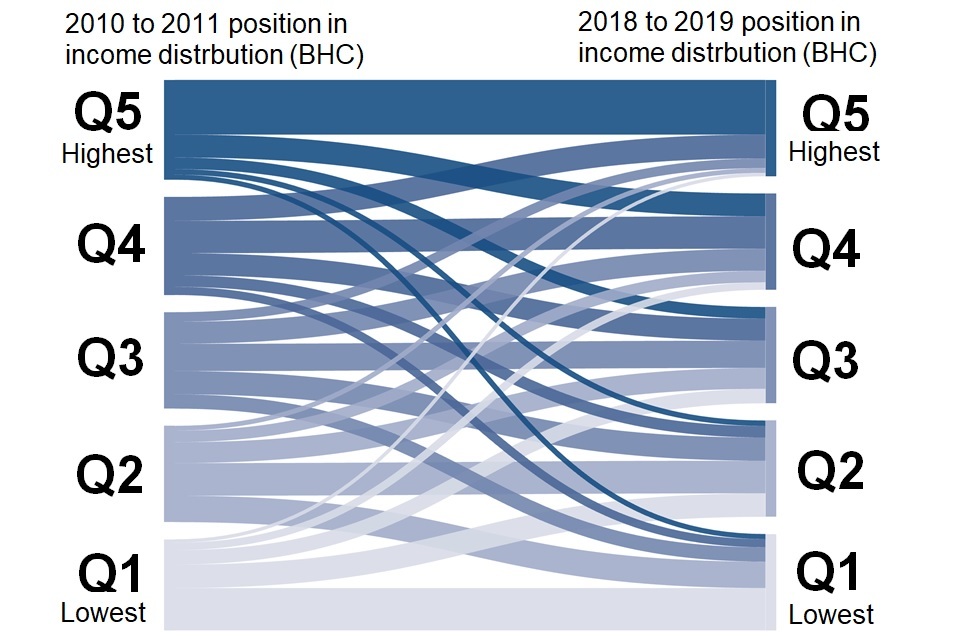

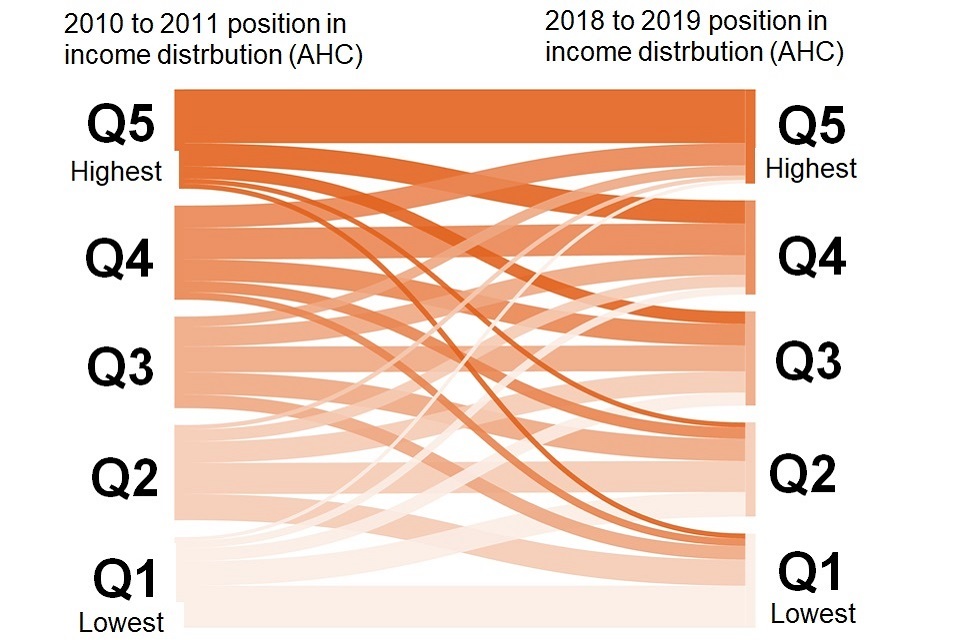

8. Movement between income quintiles

The data used in Income Dynamics is longitudinal, meaning that it follows the same individuals over time. This section compares where individuals were in the income distribution in 2010 to 2011 to where they were in the income distribution in 2018 to 2019. It does this using income quintiles, both before and after housing costs. It does not look at where individuals were in the income distribution in the intervening years.

Income quintiles divide the population, when ranked by household income, into five equally sized groups. Quintile 1 (Q1) represents the fifth of the population with the lowest household incomes. Quintile 5 (Q5) represents the fifth of the population with the highest household incomes.

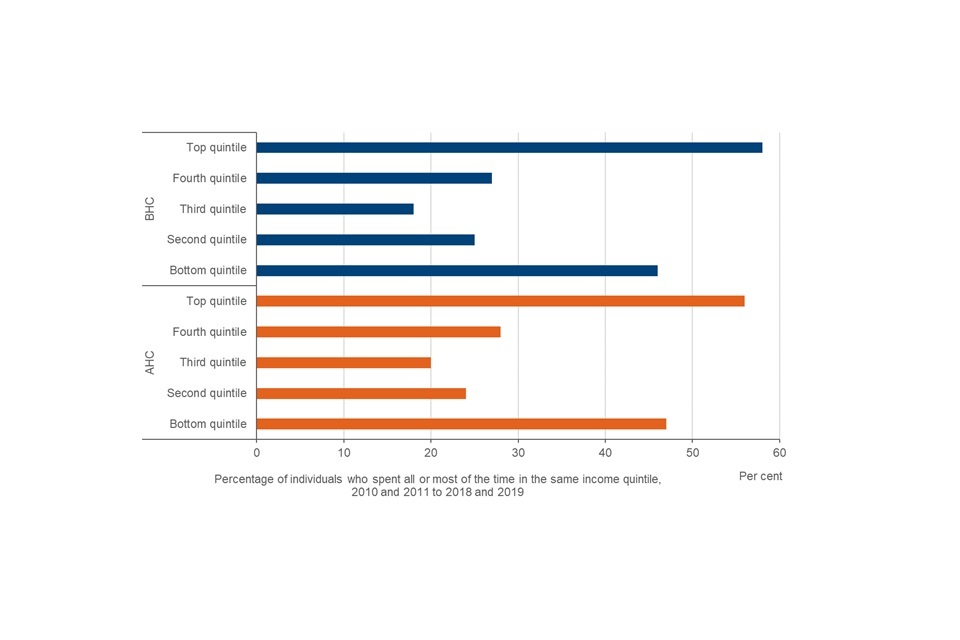

Individuals in the top and bottom income quintiles in 2010 to 2011 were more likely to be in the same income quintile in 2018 to 2019 than those in other income quintiles, both BHC and AHC

Individuals in the top (5th) quintile in 2010 to 2011 were more likely to be in the same quintile in 2018 to 2019 (56% both BHC and AHC) than individuals in any other income quintile in 2010 to 2011. Those in the bottom (1st) quintile in 2010 to 2011 were the individuals next most likely to be in the same quintile in 2018 to 2019 (41% BHC and 44% AHC). Those in the second to fourth quintiles were more likely to have moved into adjacent income quintiles by 2018 to 2019: for example, just 28% of those in the third income quintile in 2010 to 2011 (BHC and AHC) were still in the third income quintile in 2018 to 2019. Where individuals were in a different income quintile in 2018 to 2019 compared to 2010 to 2011, most had only moved by one quintile: for example, 46% of those in the third income quintile BHC in 2010 to 2011 had moved to an adjacent income quintile by 2018 to 2019, while a smaller 26% had moved to either the top or bottom quintile.

A closer look at the income quintiles in which individuals spent most of their time in the years between 2010 to 2011 and 2018 to 2019 shows that there is movement across income quintiles year on year. Most individuals experienced movement into other income quintiles at some point, although those in the top quintile were most likely to spend all or most of the intervening years in the same quintile (58% BHC and 56% AHC), followed by those in the bottom quintile (46% BHC and 47% AHC).

See Tables 6.1 and 7.1 for more information.

9. Entries into and exits from low income

The number of individuals in the sample who entered and exited low income across the period 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019 were very similar, both BHC and AHC. Rates of entry and exit are, however, very different because they are based upon different sized populations.

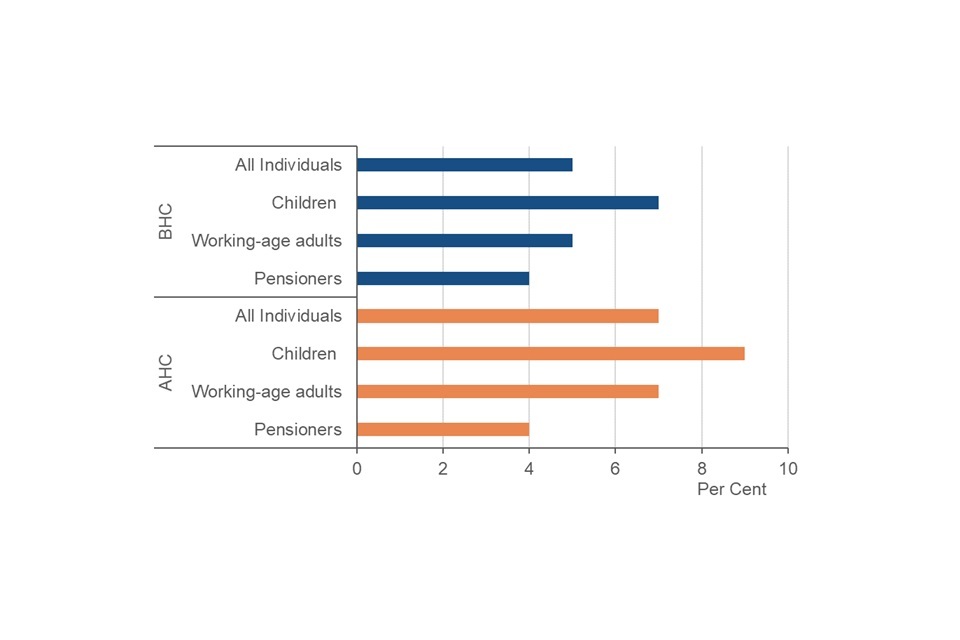

Rates of entry into low income between 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019

The rate of entry into low income for all individuals was 5% BHC and 7% AHC. Rates of entry varied less by type of individual BHC than AHC. Overall, children (AHC) had the highest risk of entering low income (9%). Pensioners were least likely to enter low income (4% BHC and AHC). Rates of entry - including for different types of individual - have remained stable over time both BHC and AHC.

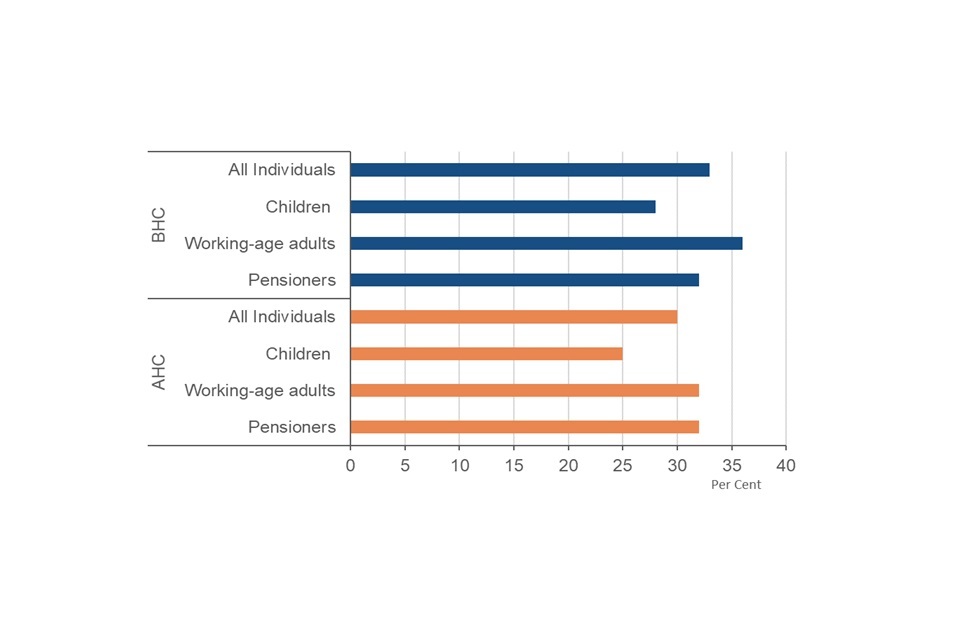

Rates of exit from low income between 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019

Note: Numbers entering and exiting low income are roughly equivalent. However, because those in low income are a smaller group than those who are not, rates of exit from low income are greater than rates of entry.

The rate of exit for all individuals was 33% BHC and 30% AHC. As with rates of entry, there was less variation by type of individual BHC than AHC. Children AHC were the group least likely to exit low income (25%), a finding which may not be surprising given other findings on rates of persistent low income and the fact that, as noted above, children AHC were at a slightly higher risk of entering low income. Rates of exit for all groups show more volatility over time than rates of entry. This may be due to smaller sample sizes.

Across the period 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019, for all groups apart from pensioners, entry rates were slightly higher AHC than BHC, and exit rates were slightly higher BHC than AHC. This indicates that housing costs may play a role in low income entry and exit for children and working-age adults but, as might be expected given tenure patterns, have a negligible effect on pensioners.

Analysis of entries and exits only includes ‘clear’ transitions. For an entry or exit to count, household incomes must cross the 60% of median income threshold and be at least 10% higher or lower than the threshold in the following wave. As individuals live in households and we assume that all members of the household benefit equally from the household’s income, they will be affected by changes at the household level.

See Tables 8.1 to 8.16 for more information, including breakdowns by demographic and other factors.

10. Events associated with entries into and exits out of low income

The previous section presented analysis on movements into and out of low income between two waves (2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019). The role of different events associated with those movements into and out of low income are explored in this section. We consider the role of changes in income components, as well as changes in employment within a household, and in the demographic composition of a household. We also consider changes in housing costs and tenure, but only on an AHC basis. Only the AHC findings over the most recent two waves are presented in this section, but BHC tables and data from previous waves are available as part of this release.

For each event, we present 3 statistics:

-

Prevalence – this tells us how common an event is among the population at risk of either entering or exiting low income. When considering the relationship between a fall in earnings and low income entry, the prevalence statistic tells us that 9% of those who were not in low income in the first wave experienced a fall in earnings between the two waves.

-

Rate of entry or exit if experienced event – in the above example, 22% of those who were not in low income in 2017 to 2018 and who experienced a decrease in earnings, entered low income in 2018 to 2019.

-

Share of entries – this tells us what percentage of all those who entered or exited low income experienced each event. In the above example, 31% of all those who entered low income experienced a fall in earnings.

In defining these events, attempts have been made to limit the effects of other, potentially important factors, which might have a bearing on the event. For example, when looking at a change in earnings, there must be no change in the number of workers in the household. It is important to note that not all such factors are controlled for.

Events associated with entering low income between 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019, AHC

| Event | Prevalence (%) | Entry rate (%) | Share of entries (%) [1] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fall in earnings [2] | 9 | 22 | 31 |

| Fall in benefit income [2] | 18 | 15 | 40 |

| Fall in investment income [2] | 14 | 6 | 11 |

| Fall in occupational pension income [2] | 5 | 7 | 6 |

| Fall in other income [2] | 5 | 12 | 9 |

| Fall in the number of workers in household - same household size | 9 | 11 | 16 |

| Fall in the number of full-time workers in household - same household size | 10 | 14 | 20 |

| Fall in the number of workers in household - change in household size | 4 | 18 | 11 |

| Fall in the number of full-time workers in household - change in household size | 3 | 17 | 9 |

| Change in household type | 13 | 9 | 18 |

| Change to a lone parent household | 1 | 35 | 3 |

| Change from a couple to single household [3] | 1 | 18 | 1 |

| Change from single to couple household [3] | 1 | 7 | 1 |

| Increase in number of children | 3 | 7 | 3 |

| Change in tenure | 5 | 13 | 9 |

| Rise in housing costs | 8 | 7 | 9 |

Notes:

[1] The share of entries column does not sum to 100% as individuals can experience more than one event.

[2] For a change in monthly income or housing costs to be considered an event, it must have risen or fallen by at least 20% and a minimum of £10. Certain demographic changes are controlled for when examining income events: changes in household earnings are only included if the number of workers stays the same. For all other income events, the number of people in the household must not change.

[3] Couple and single person households do not have children.

The percentage of individuals that were not in low income in 2017 to 2018 who experienced a fall in household earnings between 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019 was 9%. Although just 9% of individuals not in low income experienced a fall in household income, of those that did, 22% moved into low income. As such, it was the most relevant income-based risk factor for the individuals who experienced it, and almost one third (31%) of people who entered low income had a fall in household earnings.

The most commonly experienced event was a fall in benefit income, with 18% of individuals not in low income in 2017 to 2018 experiencing this over the two wave period. Although just 15% of those who experienced a fall in benefit income entered low income in 2018 to 2019, 40% of those who entered low income experienced a fall in benefit income, showing that it was closely associated with low income entry overall.

Four scenarios are considered relating to changes in the number of workers. These entail changes in the number of workers in total and the number of full-time workers, and, for each, whether the size of the household stayed the same or changed. Cases where the number of workers fell but the size of the household changed were less prevalent but more closely associated with an entry into low income for those who experienced them: 18% of households not in low income in 2017 to 2018 who experienced a fall in the number of workers and a household size change entered low income compared to 11% of cases where the household size remained the same. A similar but less pronounced pattern was observed for full-time workers. Cases where the household experienced a fall in the number of workers (either all workers or just full time workers) but retained the same household size accounted for a greater share of low income entries than where the household size changed. This may be a reflection of the overall prevalence of these events.

A change in household type included any change in the structure of the household. There are many different categories of household type so a relatively high prevalence (13%) in this event might be expected. Several specific demographic changes have been examined individually. The creation of a lone parent household was relatively uncommon among those not in low income in 2017 to 2018 (1%), but 35% of individuals who experienced this transition entered low income in 2018 to 2019. Moving from a couple to a single person household, although uncommon overall and as a share of low income entries, resulted in an 18% risk of entering low income for those individuals who experienced it.

See Tables 9.1n to 9.16n.

Events associated with exiting low income between 2017 to 2018 and 2018 to 2019, AHC

| Event | Prevalence (%) | Exit rate (%) [1] | Share of entries (%) [2] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rise in household earnings [3] | 20 | 50 | 34 |

| Rise in benefit income[3] | 28 | 49 | 45 |

| Rise in investment income[3] | 8 | 55 | 15 |

| Rise in occupational pension income[3] | 6 | 71 | 14 |

| Rise in other income [3] | 7 | 49 | 12 |

| Rise in the number of workers in household - same household size | 12 | 53 | 21 |

| Rise in the number of full-time workers in household - same household size | 11 | 57 | 20 |

| Rise in the number of workers in household - change in household size | 2 | 44 | 3 |

| Rise in the number of full-time workers in household - change in household size | 2 | .. | 3 |

| Change in household type | 14 | 41 | 19 |

| Change from a lone parent household | 2 | .. | 2 |

| Change from a couple to single household [4] | - | .. | - |

| Change from single to couple household [4] | 1 | .. | 1 |

| Decrease in number of children | 5 | 47 | 8 |

| Change in tenure | 8 | 39 | 10 |

| Decrease in housing costs | 8 | 24 | 7 |

Notes:

“..” indicates that the figure has been suppressed due to small sample size.

“-” indicates that the figure is negligible (less than 0.5%).

[1] Because those in low income are a smaller group than those who are not, and are, by definition, closer to the low income threshold, they have a greater chance of exiting low income if they experience a particular event than those not in low income have of entering low income if they experience the same event. This explains why exit rates tend to be higher than entry rates.

[2] The share of entries column doesn’t sum to 100% as individuals can experience more than one event.

[3] For a change in monthly income or housing costs to be considered an event, it must have risen or fallen by at least 20% and a minimum of £10. Certain demographic changes are controlled for when examining income events: changes in household earnings are only included if the number of workers stays the same. For all other income events, the number of people in the household must not change.

[4] Couple and single person households do not have children.

An increase in benefit income was the most prevalent event experienced by those in low income in 2017 to 2018 (28%), followed by an increase in household earnings (20%). While increases in other forms of income were much less prevalent, all income events were closely associated with an exit from low income for individuals who experienced them. An increase in benefit income was also the most common event experienced by those who exited low income (45% of those who exited low income experienced this) followed by an increase in household earnings (experienced by 34% of those who exited low income). The fact that changes in earnings and benefits are the events which account for the largest single shares of both low income entries and exits suggests that these events are closely linked to low income transitions.

While just 6% of those in low income experienced an increase in income from an occupational pension, it was associated with the highest exit rate (71%), and this event accounted for 14% of all low income exits.

An increase in the number of workers where the household size stayed the same was associated with a low income exit rate of 53%. An increase in the number of full-time workers, with no change in household size, had a slightly higher exit rate of 57%. Both events each comprised around a fifth of all low income exits, highlighting the link between increased employment and low income exit. Cases where there was an increase in the number of workers as well as a change in household size were far less frequent.

While 14% of individuals in low income in 2017 to 2018 experienced a change in their household type in 2018 to 2019, the prevalence of specific demographic events considered here means that results have been suppressed due to small sample sizes.

See Tables 9.1x to 9.16x

More information on the definitions and approach used for this analysis is available in the ID Background information and methodology report. We would welcome feedback on this new analysis. Please send any comments to: teamincome.dynamics@dwp.gov.uk.

11. About these statistics

ID uses data from Understanding Society to derive a measure of disposable household income. Adjustments are made to take into account the size and composition of households to make figures comparable.

Definitions

Understanding Society

Understanding Society, led by the University of Essex, is a longitudinal survey of individuals in the United Kingdom which has been running since 2009. Between 2018 to 2019, the sample included over 29,000 individuals. Those not in private households at the start of the survey in 2009 are not included.

Income

This includes:

- Labour income – usual pay and self-employment earnings. Includes income from second jobs

- Miscellaneous income – educational grants, payments from family members and any other regular payments

- Private benefit income – includes trade union/friendly society payments, maintenance or alimony and sickness or accident insurance

- Investment income – private pensions/annuities, rents received, income from savings and investments

- Pension income – occupational pensions income

- State support – tax credits and all state benefits including State Pension

A household income measure implicitly assumes that all members of the household benefit equally from the household’s income and so appear at the same position in the income distribution.

Before Housing Costs (BHC) income

Often used for non-pensioner analysis and is net of the following:

- Income tax payments and National Insurance

- Contributions

- Council tax

After Housing Costs (AHC) income

Derived by deducting housing costs (mortgage interest and rent payments) from the BHC income measure. It is often used for pensioner analysis.

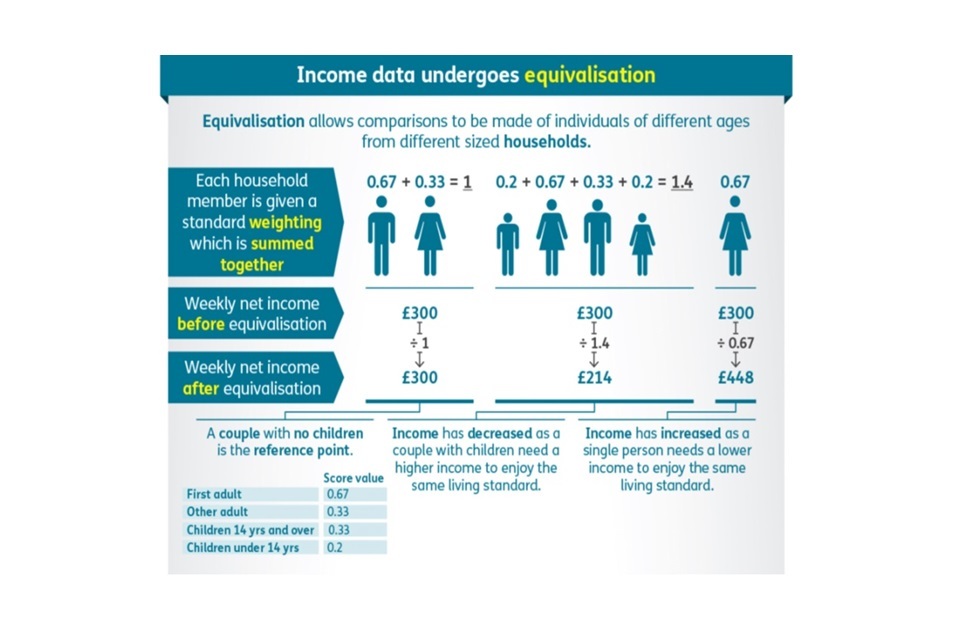

Equivalisation

An adjustment is made to income to make it comparable across households of different size and composition. For example, this process of equivalisation would adjust the income of a single person upwards, so their income can be compared directly to that of a couple.

Relative Low Income

This is defined for this publication as an individual in a household with an equivalised household income of less than 60% of median income. A household is in persistent low income if they are in low income for at least three of the last four survey periods.

Inflation

This concerns how goods and services increase in price (generally) over time. ID uses an adjustment based on the Consumer Prices Index (CPI), also used in HBAI, to compensate for the effects of inflation over time.

Sampling Error

Results from surveys are estimates and not precise figures – in general terms the smaller the sample size, the larger the uncertainty. We are unable to calculate sampling uncertainties for these statistics, but please note that small changes are unlikely to be statistically significant.

Non-sampling Error

Survey data represents the best data from respondents to the survey. If people give inaccurate responses or certain groups of people are less likely to respond, this can introduce bias and error. This non-sampling error can be minimised through effective and accurate sample and questionnaire design and extensive quality assurance of the data. However, it is not possible to eliminate it completely, nor can it be quantified.

Equivalisation explained

Equivalisation allows comparisons of income levels to be made between individuals of different ages from different sized households. Each household member is given a weighting which is summed together to provide a household weighting factor. Household weekly net income is divided by that factor to give equivalised income. A couple with no children is the reference point.

Weights are: first adult 0.67; other adult or child 14 years and over 0.33; child under 14 years 0.2.

Official Statistics

Income Dynamics is Official Statistics.

National, Official and Experimental Statistics are produced in accordance with the Statistics and Registration Service Act 2007 and the Code of Practice for Statistics. National Statistics status means that official statistics meet the highest standards of trustworthiness, quality and public value, signifying compliance with all aspects of the Code. Official and Experimental Statistics may be awarded National Statistics status following an assessment by the Office for Statistics Regulation, the regulatory arm of the UK Statistics Authority.

Further information about National, Official and Experimental Statistics status can be found in the Code glossary.

Contact information and feedback

DWP would like to hear your views on our statistical publications. If you use any of our statistics publications, we would be interested in hearing what you use them for and how well they meet your requirements.

Press enquiries should be directed to the:

DWP Press Office

Telephone: 0203 267 5144.

Enquiries about these statistics should be directed by email to: teamincome.dynamics@dwp.gov.uk

Lead Analyst: Helen Smith

ISBN: 978-1-78659-312-2

12. Related statistics

Reference tables from Income Dynamics analysis, alongside our ID Background information and methodology report which provides further detail on how we estimate the measures reported here,

Analysis of Income Dynamics data from previous years, as well as further guidance and information about the statistics.

Estimates of numbers in low income in a single year from Households Below Average Income are available.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) produce a National Statistics series on persistent low income based on EU-SILC data. This is based on a different data source (the Survey of Living Conditions) and has a different definition of persistent low income (see ID Background information and methodology report for further details).

The following ONS publications provide useful information and guidance on alternative sources of data on earnings and income:

Details of other National and Official Statistics produced by the Department for Work and Pensions can be found via the following links:

-

a schedule of statistical releases over the next 12 months and a list of the most recent releases

-

in accordance with the Code of Practice for Statistics, all DWP National Statistics are also announced in the statistics release calendar