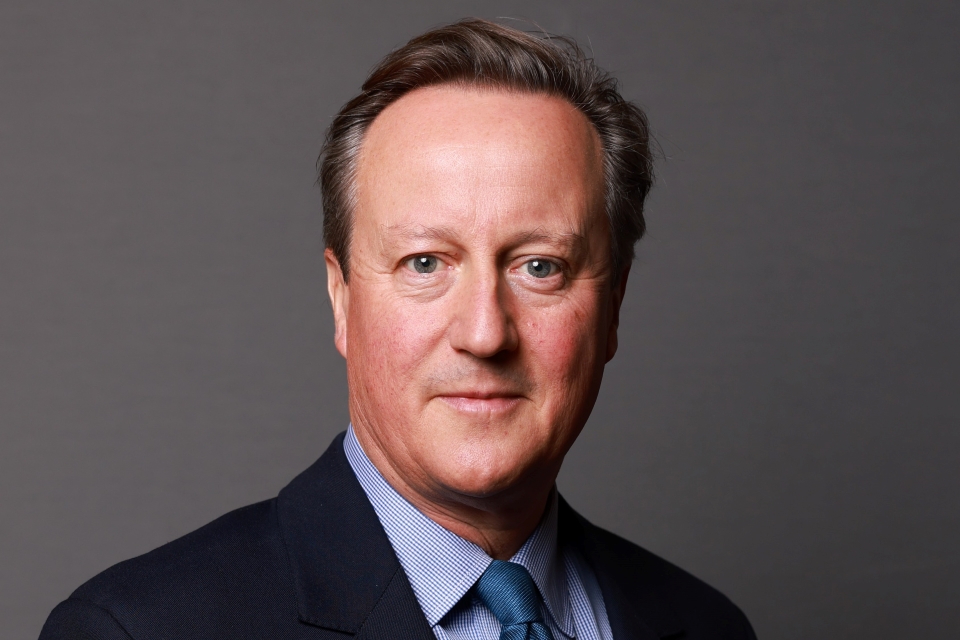

JCB Staffordshire: Prime Minister’s speech

The Prime Minister delivered this speech at JCB, Staffordshire. It includes proposals made as Leader of the Conservative Party.

Thank you very much. Well thank you very much indeed for that introduction, and it’s great to be back at this inspirational company that has had such success in recent years, not only here but around the world: in India, in Brazil, and elsewhere. You are an absolute magnet for talent, and I think a great British company that’s investing in skills, that is making, investing, selling around the world, doing all the things that we want you to as part of our long-term economic plan.

Immigration

Now today I want to talk about immigration, and, just as this government has a long-term plan for where we’re taking our country, so within that, we have a long-term plan for immigration. Immigration benefits Britain, but it needs to be controlled, it needs to be fair, and it needs to be centred around our national interest. That is what I want. And I want to tell you today why I care so passionately about getting this right, and getting the whole debate on immigration right in our country. When I think about what makes me proud to be British, yes, it’s our history, our values, our creativity, our compassion. But there is something else too. I am extremely proud that together we have built a successful, multi racial democracy. A country where, in 1 or 2 generations, people can come with nothing, and rise as high as their talent allows. A country whose success has been founded not on building separate futures, but rather on coming together to build a common home.

Openness

We’ve always been an open nation, welcoming those who want to make a contribution and build a decent life for themselves and their families. From the Jewish communities who came to Britain before World War I, to the West Indians who docked at Tilbury on the Windrush and helped to rebuild our country after World War II. Even at times of war and danger, when our island status has protected us, we’ve offered sanctuary to those fleeing tyranny and persecution. We’ll never forget the Polish and Czech pilots who helped save this country in its hour of need, and the Poles who went on to settle here, to help build post war Britain, and indeed who contribute so much to our country today. And we’re proud, very proud, of the role that we played in providing a haven to, for instance, the Ugandan Asians in the early 1970s, who now count amongst their number 4 members of the House of Lords, some of the UK’s most successful businessmen, a BBC news presenter and the owner of a company providing china to the royal households.

Our openness is part of who we are. We should celebrate it. We should never allow anyone to demonise it. And we must never give in to those who would throw away our values with the appalling prospect of repatriating migrants who are here totally legally and have lived here for years. We are Great Britain because of immigration, not in spite of it.

So it’s fundamental to the future of our country that we get this issue right, and in doing so there are 3 dangerous views that we need to confront. First is the complacent view, the view that says the levels of immigration we’ve seen in the past decade aren’t really a problem at all. The view that says that mass migration is just an unavoidable by-product of a new world order of globalisation, and that that globalisation is an unalloyed good, and those complaining about immigration just need to get with the modern world. Now often the people who have these views are people who have no direct experience of the impact of high levels of migration. They’ve never waited on a social housing list, or found that their child’s classroom is overcrowded, or felt that their community has changed too fast. And what makes everyone else really angry is that, if they dare to express these concerns, they can be made to feel guilty about doing so. So we should be clear: it is not wrong to express concern about the scale of people coming into our country.

Control

People have understandably become frustrated, and it boils down to 1 word: control. People want government to have control over the number of people coming here, and the circumstances in which they come, both from around the world and from within the European Union. They want control over who has the right to receive benefits and what is expected of them in return. They want to know that foreign criminals can be excluded, or if already here, removed. And they want us to manage carefully the pressure on our schools, on our hospitals, and on our housing. If we are to maintain this successful, open, meritocratic democracy that we treasure, we have to maintain faith in government’s ability to control the rate at which people come to our country.

And yet, in recent years, it has become clear that successive governments lack control. People want grip. I get that. I completely agree with that, and to respond to this view with complacency is both wrong and dangerous.

Isolationism

Now the second dangerous view is to think that we can somehow pull up the drawbridge, retreat from the world, and just shut off immigration altogether. Now people who make this argument try to dress it up as speaking up for our country, but this isolationism is actually deeply unpatriotic. Yes, Britain is an island nation, but we’ve never been an insular one. Throughout our long history, we’ve always looked outward, not inward. We’ve used the seas that surround our shores not to cut ourselves off from the world, but to reach out to it, to carry our trade to the four corners of the earth. And with that trade has come people, companies, jobs and investment. And we’ve always understood that our national greatness is built on our openness.

And we see that every day. We see it in our National Health Service, which would grind to a halt without the hundreds of thousands who come from overseas to help run it. We see it in the City of London, the financial epicentre of the world, where so many from so many different countries have come to make Britain their home. We have it in the Bank of England, where the best central bank governor in the world, a Canadian, is our governor. We see it in our world class universities, where students and professors have come from all over the world. This is modern Britain, a country that’s come out of recession to become the fastest growing advanced economy in the world. And that has happened in part because we are an open nation. And for the sake of British jobs, British livelihoods, British opportunities, we must fight this dangerous and misguided view that our nation can withdraw from the world and somehow all will be well.

Education

Now the third view that we need to confront is the idea that a successful plan to control immigration is only about immigration policy and immigration controls. A modern immigration plan is not just about the decisions you take on the people you allow into your country. It’s also about the education you provide to your own people, and the rights and responsibilities that you have at the heart of your own welfare system. Because let’s be frank, the problem hasn’t just been a simplistic one of too many people coming here, it’s also been a problem of too many British people untrained, too many British people without the incentive to work because they can get a better income living on benefits. Even at the end of the so called boom years, there were around 5 million people in our country of working age but on out of work benefits. And this was at the same time as the last government enabled the largest wave of migration in our country’s history.

So I want young British people schooled enough, skilled enough and keen enough to work, so there is less demand for foreign workers. Put simply, our job is to educate and train up our youth, so that we’re less reliant on immigration to fill our skills gap. And any politician who doesn’t have a serious plan for welfare and education does not have a serious long-term plan for controlling immigration either.

So in taking on these views, we also need to choose our language carefully. We must anchor this debate in fact, not prejudice. We must have no truck with those who use immigration to foment division or as a surrogate for other agendas. And we should distrust those who sell the snake oil of simple solutions. There are no simple solutions. Managing immigration is hard, not only here but in every developed country – certainly in Europe. Look at Italy where migration from North Africa is a vital issue. Look at Germany where benefit tourism is a huge concern. Look at the United States, the ultimate melting pot, where President Obama has just announced sweeping reforms. Look at Australia – whose points-base system we now operate in Britain – where the issue of immigration dominated their last election campaign but where migrant numbers are actually higher pro rata than here in the UK.

Now, I think the British people understand this. They know that a modern, knowledge-based economy like ours needs immigration. And there is, if you like, a parallel here. On the European Union, most British people don’t want a false choice between the status quo or leaving; they want reform and then a referendum. And on immigration, they don’t want limitless immigration, and they don’t want no immigration; they want controlled immigration, and so do I.

So what are the facts? Over the last 10 years, immigration to the United Kingdom has soared while the number of Britons going to work aboard has remained roughly the same. As a result, net migration, a reasonably good way of measuring the pressure of immigration, has gone up significantly. Let me give you some idea of the scale. In terms of net figures, in the 30 years leading up to 2004, net migration to the UK was around 1 million. In the next 7 years, it was 1.5 million. The gross figures are that 8.3 million people came to the UK as long-term migrants in the 30 years in the run-up to 2004, but a further 4 million came in just the next 7 years. What caused this increase? Now, certainly, a lax approach to immigration by the last government which they themselves have since admitted. For example, their points system included an entire category for people from outside the European Union with no skills at all to come to the United Kingdom. That was clearly mad.

It was too easy also for foreign nationals to become citizens. There was a huge increase in asylum claims. There were disproportionate numbers of jobs going to foreign workers. The welfare system allowed new EU migrant workers to claim immediately without having paid in, which is in contrast to many, many other countries. And of course there was the decision by the last government not to impose transitional controls on the 8 new countries which entered the European Union in 2004. Now, with their economies considerably poorer than ours, and with almost every other EU country opting to keep those controls, it made the UK a uniquely attractive destination for the citizens of those countries, and a million people came to Britain after that decision.

Immigration reform

So when we came to office in 2010, we were determined to get to grips with this problem. So we set a clear target to return net migration to 1990s levels when, even though we had an open economy, we had proper immigration controls, and that meant that immigration was in the tens of thousands, not the hundreds of thousands. And we set to work on it immediately with a clear plan to tackle the non-EU migration in a targeted way while continuing to permit companies to bring in the skilled workers they need and allowing universities to attract the best talent from around the world.

So we took action to cut numbers, to tackle abuse on every one of the visa routes for those coming to Britain from outside Europe. We imposed an annual cap on economic migration of 20,700. We clamped down on the bogus students and we stopped nearly 800 fake colleges from bringing people in. We insisted that those wishing to have family come and join them had to earn at least £18,600 a year, and they had to pass an English language test.

And in addition, we’ve made Britain a much harder place to exist if you are an illegal migrant. This is all relentless, painstaking work. I’ve been out on the ground with the Border Force staff. I’ve talked with immigration officers who used to have no choice but to admit what they felt sure were fake students, claiming to come here to study but not really being able to speak a word of English. So we’ve tightened up across the board: not only at the border but also inside the country too, stopping illegal immigrants from opening a bank account, or obtaining a driving licence or renting a home. These are measures which other parties did not support but which I believe are essential and need to be carried out forward, faster and further.

We brought back also vital exit checks at our ports and airports. And by April next year, those checks will be enforced at all our major ports and airports. So we’ll be able not only to count people in but also to count them out again. And in Calais, we’ve created a £12 million fund to strengthen security and we’re working more closely than ever with our French partners to tackle the illegal immigration and track down the people smugglers which people see with such frustration on their television screens every night.

This determined effort is making a real difference. Even after yesterday’s disappointing figures, net migration from outside Europe is down by almost a quarter and falling close to the levels seen in the late 1990s. Without our reforms, in the last year alone, 50,000 more migrants from outside the EU would have come to the UK.

But if I’m Prime Minister after the next election, we will go further. We will revoke licences from colleges and businesses which fail to do enough to prevent large numbers of migrants that they sponsor overstaying their visas. We will extend our new policy of deport first, appeal later to cover all immigration appeals where a so-called right to family life is invoked. We will rapidly implement the requirement, including in our 2014 Immigration Act, for landlords to check the immigration status of their tenants.

We’ll do all of these things and we will continue with our welfare and education reforms, making sure it always pays to work, training more British workers right across the country but especially in local areas that are heavily reliant on migrant labour and supporting those communities with a new fund to help meet additional demands on local services. We’ll also introduce stronger powers to tackle the criminal gangs who bring people into our country and then withhold their passports and their pay.

And I’m proud today that we’ll be publishing our modern slavery strategy, clamping down on those appalling criminals who try and traffic people into our country. But our action to cut migration from outside the EU has not been enough to meet our target of cutting the overall numbers to the tens of thousands. The figures yesterday demonstrate that again. As we’ve reduced the numbers coming to the UK from outside the European Union, the numbers from inside the European Union have risen. In other words, the squeeze in one area has been offset by a bulge in the other. But the ambition remains the right one, but it’s clear it’s going to take more time, more work and more difficult long-term decisions in order to get there.

Now some people disagree with the whole concept of a net migration target because they say you can be blown off course by the numbers of people emigrating, the numbers of people leaving Britain each year. But I think there are two reasons why it is worthwhile. First of all, it measures the overall impact – the impact of migration on our country. And secondly, emigration figures from Britain have been and still are relatively constant. But I accept the logic of the argument from these people who make that point. So as well as sticking to our ambition, we’ll set out additional metrics in the future so that people can clearly chart the progress on the scale of migration from outside the EU and from within it.

EU net migration

So let me set out why net migration from the EU is rising and exactly what we’re going to do about it. The first thing to say though is it is a tribute to Britain that so many people want to come here. This has not always been the case. In the 1970s, when Britain was the sick man of Europe, more people were leaving Britain than coming here. Today, they’re coming for perfectly understandable reasons. We are currently the jobs factory of Europe. Our unemployment is tumbling and is now about half the level that it is in France and a quarter of the level it is in Spain.

And whereas in the past, the majority of the growth in employment was taken up by foreign nationals, last year 2 thirds of the growth benefited British workers. Now, while some eurozone economies remain weak, our economy is now growing faster than every major economy in Europe and indeed is the fastest growing economy in the G7. That fact, combined with our generous welfare system, including for those in work, makes the United Kingdom a magnetic destination for workers from other European countries.

But let me be clear. The great majority of those who come here from Europe come to work, work hard, and they pay their taxes. They contribute to our country. They’re willing to travel across the continent in search of a better life for them and their families. Many of them come for just a short period, a year or two before then returning home. And once economic growth returns to the countries of the eurozone and those economies start to grow and prosper, the economic pendulum will start to swing back, and that will require far-reaching structural reform in Europe and removing barriers to job creation in other countries. And I welcome the intention of the new European Commission to tackle these issues. They will have the wholehearted support of the United Kingdom in doing so.

“So what,” sometimes my European counterparts say to me; “What’s the issue?” They say, “You’ve got unemployment falling. Your economy is growing. This doesn’t look to us like a serious problem.” Indeed, many say, “We wish we had the sort of problems that you’ve got in Britain.” And some in Europe just think our problems are because our welfare system is a soft touch. But this government has already taken unprecedented action to make sure our welfare system is fairer and less open to abuse, all within the current rules. And these reforms, including restricting EU jobseeker entitlements, they will save our tax payers £0.5 billion over the next 5 years.

But even with these changes, the pressure is still very great. In some areas, the number of migrants we’re seeing is far higher than our local authorities, our schools and our hospitals can cope with. They’re much higher than anything the EU has known before in its history. They’re far higher than what the founding fathers envisaged when the European Economic Community was established in 1957 or what Margaret Thatcher and Helmut Kohl envisaged when they signed the Single European Act in 1986.

One million people coming to 1 member state: that is a vast migration on a scale that has not happened before in peacetime. And yesterday’s figures show that the scale of migration is still very great. So many people, so fast is placing real burdens on our public services. There are secondary schools where the turnover of pupils can be as high as 1 third of the whole school inside a year. There are primary schools where dozen of languages are spoken, with only a small minority speaking English as their first language. There are hospitals where maternity units are under great pressure because birth rates have increased dramatically. There are accident and emergency departments, as we know, under serious pressure. There’s pressure on social housing that can’t be met. And all this in a country with a generous non-contributory welfare system. All of this is raising real issues of fairness.

People cannot understand how those who have not paid in can immediately take out, and they find it incomprehensible that a family coming from another EU country can claim child benefit from the UK at UK rates and send it back to children still living in their home country. When trust in the European Union is already so low, we cannot leave injustices like this to fester.

Now some of our partners will say, “But you’re not unique. Germany, for instance, has had more EU migrants than the UK.” But Germany is in a different situation. Germany’s population is falling whereas Britain’s is rising.

Freedom of movement

Now dealing with this issue in the European Union is not straightforward because of the freedom of movement to which all EU member states signed up. And I want to be clear again, Britain supports the principle of the free movement of workers. We benefit from it. And 1.3 million British citizens exercise their right to go and live and work, and, in many cases, retire in other European countries. Accepting the principle of free movement of workers is a key to being part of the single market, a market from which Britain has clearly benefited enormously. So we don’t want to destroy that principle or turn it on its head. Those who argue that Norway or Switzerland offer a better model for Britain, they ignore 1 crucial fact; they have each had to sign up to the principle of the freedom of movement in order to get access to the single market. And both countries actually have higher per capita immigration than the United Kingdom.

But freedom of movement has never been an unqualified right, and we now need to allow it to operate on a more sustainable basis, in the light of experience in recent years. But that doesn’t mean a closed door regime or a fundamental assault on the principle of free movement. But what it does mean is finding arrangements to allow a member state like the United Kingdom to restore a sense of fairness and to bring down the current spike in numbers.

My objective is simple, to make our immigration system fairer and to reduce the exceptionally high level of migration from within the EU into the UK. I’m completely committed to delivering that and I’m ready to discuss with our partners any methods which achieve it while maintaining the overall principle to which they and we attach such importance.

Let me set out the action we intend to take to cut migration from within Europe by dealing with abuse, by restricting the ability of migrants to stay here without a job, and by reducing the incentives for lower-paid, lower-skilled workers to come here in the first place.

First, we want to create the toughest system in the EU for dealing with the abuse of free movement. This includes stronger powers to deport criminals and to stop them coming back. And it includes tougher and longer re-entry bans for all of those who abuse free movement, including beggars, rough sleepers, fraudsters and people who collude in sham marriages. And we must also deal with the extraordinary situation where it’s easier for an EU citizen to bring a non-EU spouse to Britain than it is for a British citizen to do exactly the same thing.

At the moment, if a British citizen wants to bring, say, a South American partner to the UK, then we, quite sensibly, ask for proof that they meet an income threshold and that they can speak English. But the EU law means that we cannot apply these tests to EU migrants. Their partners can just come straight into our country without any proper controls at all. And this has driven a new industry in sham marriages, with this loophole accounting for most of the 4,000 bogus marriages that are thought to take place in our country every year. We have got to end this abuse.

Second, we want EU jobseekers to have a job offer before they come here and to stop UK taxpayers having to support them if they don’t. This government inherited an indefensible system where the state – our taxpayers – paid EU jobseekers to look for work indefinitely and even paid their rent while they did so. In total, that meant that the British taxpayer was supporting a typical EU jobseeker with £600 a month.

Now we’ve already begun to change this. We’ve scrapped housing benefit for EU jobseekers and we’ve limited benefit claims to 3 months for those EU migrants who have no prospect of a job.

But now, we are going to go further. We are overhauling our welfare system with a new benefit called Universal Credit. This will replace existing benefits, such as Jobseeker’s Allowance, that support people when they’re out of work. And its legal status means that we can regain control over who we pay it to. So as Universal Credit is introduced, we’ll pass a new law that means EU jobseekers will not be able to claim it and we’ll do this within existing EU law. So instead of £600, they will get nothing.

We also want to restrict the time that jobseekers can legally stay in this country. Let’s be clear about what this will mean: if an EU jobseeker has not found work within 6 months, they will be required to leave. Now, why this matters is that, at the moment, 40% of those coming to work in the UK don’t actually have a job offer when they arrive. That is the highest proportion for any EU country and, I believe, with this change, many of those will now longer come.

EU jobseekers who don’t pay in will no longer get anything out, and those who do come will no longer be able to stay if they can’t find work. There was a time when freedom of movement meant member states could expect workers to have a job offer before they arrived, and these measures will return us to closer to that position.

Third, we want to reduce the number of EU workers coming to the UK. Of course, that means never repeating the mistake that was made in 2004, so we will insist that, when new countries are admitted to the EU, in the future, free movement will not apply to those new members until their economies have converged much more closely with existing member states. Further accession treaties – when a new country joins – they require unanimous agreement of all member states, so we are perfectly able to ensure that this change is included in each and every case in future.

But we also need to do more now to reduce migration from current member states, and that means reducing the incentives for lower paid, lower skilled EU workers to come here in the first place. Now, our welfare system is unusual in Europe. It pays out before you pay into it. This gives us particular difficulties, especially in respect of benefits while you’re working, the so called ‘in work benefits’. Someone coming to the UK from elsewhere in Europe, who’s employed on the medium wage and who has 2 children back in their home country, they today will receive around £700 per month in benefits in the UK. That is more than twice what they’d receive in Germany, and 3 times more than they would receive in France. No wonder so many people want to come to Britain. These tax credits and other welfare payments are a big financial incentive, and we know that over 400,000 EU migrants take advantage of them. This has got to change.

I will insist that, in the future, those who want to claim tax credits and child benefit must live here and contribute to our country for a minimum of 4 years. If their child is living abroad, then there should be no child benefit or no tax credit at all, no matter how long they’ve worked in the UK and no matter how much tax they’ve paid. We’ll introduce a new residency requirement for social housing, meaning that you can’t even be considered for a council house, unless you’ve been here again for at least 4 years.

This is about saying our welfare system, in a way, should be like a national club. It’s made up of the contributions of hardworking British taxpayers, millions of people doing the right thing, paying into the system, generation after generation. It cannot be right that migrants can turn up and claim full rights to this club straight away.

So let’s be clear what all these changes taken together will mean. EU migrants should have a job offer before they come here. UK taxpayers will not support them if they don’t. And once they’re in work, they won’t get benefits or social housing from Britain unless they’ve been here for at least 4 years. Yes, these are radical reforms, but they are also reasonable and fair. And the British people need to know that changes to welfare to cut EU migration, they will be an absolute requirement in the negotiation that I’m going to undertake. I’m confident that they will reduce significantly EU migration to the UK, and that is what I’m determined to deliver.

My very clear aim is to be able to negotiate these changes for the whole EU, because I believe they’d benefit the whole EU. They take account of the particular circumstances of our own welfare system and they go with the grain of what other member states, with high numbers of EU benefit claimants, are considering. And of course, we’d expect them to apply on a reciprocal basis to British citizens elsewhere in the EU. If negotiating for the whole EU should not prove possible, I would want to see them in a UK only settlement.

Now, I know that many people will say, “This is impossible, just impossible”. Some of the most ardent supporters of the European Union will say it’s impossible, fearing that, if an accommodation is made for Britain, the whole European Union will unravel. And those who passionately want Britain to leave, they will say, “It is impossible, and the only way to control immigration is for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union”. On this, at least they would agree.

To those who claim that change is impossible, I respond with 1 word, the most powerful word in the English language: why? Why is it impossible? Why is it impossible to find a way forward on this issue and on other issues that meet the real concerns of a major member state, 1 of the biggest net contributors to the EU budget? I simply don’t accept such defeatism.

I say to our European partners we have real concerns. Our concerns are not outlandish or unreasonable. We deserve to be heard and we must be heard, not only for Britain’s sake, but for the rest of Europe as a whole, because what’s happening in Britain is not unique to Britain. Across the European Union, issues of migration are causing real concern and raising real questions. Can movements on the scale we’ve seen in recent years always be in the best interests of the EU and wider European solidarity? Can it be in the interests of Central and Eastern European member states that so many of their brightest and best are drawn away from home when they’re needed most? This concern takes a different form in different member states, and has different causes, but it has 1 common feature: it is contributing to a corrosion of trust in the European Union and the rise of populist parties. And if we ignore it, it will not go away.

Across the European Union, we’re seeing the frustration of our citizens demonstrated in the results of the recent European elections. Leadership means dealing with those frustrations, not turning a deaf ear to them, and we have a duty to act on them to restore the democratic legitimacy of the EU.

So I say to our friends in Europe: it is time we talked about this properly, and a conversation cannot begin with the word no. The entire European Union is built on a gift for compromise, for finding difficult ways around difficult corners, for accepting that sometimes we have to avoid making the perfect the enemy of the good. That is the way the EU operates; that is the way a union of 28 democracies has to operate: flexibility, not rigidity; creativity, not dogma. Only this month, a way was found to accommodate France breaching its budget deficit limit, as everyone knew it would be, and it can be done again.

Two years ago at Bloomberg, I set out my vision for a reformed European Union. I stand by every word of that speech today, a reformed EU, in the interest not only of Britain but of every member state. Now, of course I know the arguments that will be put. It will be argued that freedom of movement is a holy principle, 1 of the 4 cardinal principles of the EU, alongside freedom of capital, of services and of goods. People will say what we’re suggesting is heresy, to which I would say hang on a minute. No one claims that the other freedoms have been yet fully implemented; far from it. It’s still not possible for a British optician to trade freely in Italy, or for a French company to raise funds in Germany. It’s still not possible for consumers to access their Netflix or their iTunes accounts across the borders of the EU.

Freedom of movement itself is not absolute. There are new rules for when member states join the EU precisely to cope with excessive numbers, so why can’t there be steps to allow member states a greater degree of control in order to uphold a general and important principle, but one which is already qualified.

And of course, freedom of movement has evolved significantly over the years, from applying to job holders to jobseekers too, from jobseekers to their non European family members, and from a right to work to a right to claim a range of benefits.

So I’m saying to our European partners, I ask you to work with us on this. I know some of you will be saying, “Why bother?” Some of you may even say it in public, to which my answer is clear: because it is worth it. Look at what Britain brings to Europe: the fastest growing economy and the second largest; 1 of Europe’s strongest powers, a country which in many ways invented the single market and which brings real heft to Europe’s influence on the world stage. Here is an issue which matters to the British people and to our future in the European Union. The British people will not understand – frankly, I will not understand – if a sensible way through cannot be found which will help settle this country’s place in the EU, once and for all.

And to the British people I say this: I share your concern and I’m acting on it. I know how much this matters. Judge me by my record in Europe. I promised we would cut the EU budget, and we have. I said I would veto a treaty if it wasn’t in our interests, and I did. I do not pretend that this will be easy. It won’t be. It will require a lot of hard pounding, a lot of hard negotiation, but it will be worth it.

Because those who promise you simple solutions are betraying you. Those who say we would certainly be better off outside the EU, only tell you one part of the story. Of course we could survive. There’s no doubt about that, but we’d need to weigh in the balance the loss of our instant access to the single market and our right to take the decisions that regulate it, and of course we’d lose the automatic right for the 1.3 million British citizens who today are living and working elsewhere in Europe to do so. That is something we would want to think about carefully before giving up.

For me, I have 1 test and 1 test only. What is in the best long term interests of the people of our country? That is the measure against which everything must be judged. If you elect me as Prime Minister in May, I will negotiate to reform the European Union and Britain’s relationship within it. This issue of free movement will be a key part of that negotiation. If I succeed, I will, as I’ve said, campaign to keep our country in a reformed European Union. If our concerns fall on deaf ears and we cannot put our relationship with the EU on a better footing, then of course I rule nothing out. But I’m confident that, with good will and understanding, we can and we will succeed.

At the end of the day, whatever happens, the final decision will be yours when you place your cross on the ballot paper in the referendum to decide whether Britain remains in the European Union or not. That decision is for you – for the British people – and for you alone. Thank you.

Thank you very much. We’ve got some time for questions from the media.

Question

Prime Minister, thank you very much indeed. You made a promise to cut immigration; you failed to deliver that promise. Do you not owe the British people an apology, no ‘ifs’, no ‘buts’?

Can you explain on policy: you have endlessly floated, or it’s been floated on your behalf – it’s been endlessly suggested you would look at a limit or a cap or an emergency brake to the numbers coming. Why, at the last minute, have you abandoned that idea?

Prime Minister

First of all, look, of course I want to get net migration back to the tens of thousands, which it was in the 1990s. This is not some outlandish unachievable pledge. We were an open economy then. We were a trading economy then. We welcomed students from around the world then. Obviously when I made that commitment, I didn’t know that the eurozone was going to be potentially having 3 recessions in 6 years, and that has been a major barrier to its achievement. As I said in my speech, there’s more that needs to be done, more time required, more long term decisions, and I’ve set those out today.

What I’ve tried to do today is to examine, really carefully, what will work. And to me, what is most important here is the economic incentives there are that are bringing people to our country. That is both the incentives we create by not having a hardworking welfare system and by not improving fast enough our education standards, but also what we do to attract people from within the EU to come. Changing those economic regards will be the biggest change that we can make. That will be effective.

When I compare that with negotiating some sort of EU led, EU determined brake, which would be determined and applied probably by the European Commission, I don’t actually think that would be effective, because there are countries in Europe with very high levels of immigration that don’t want the sort of controls that I want to put in place. So this is what will work.

You’ve heard the figures: jobseekers being able to get £600 a month; people being able to get, if they’re working in Britain with a couple of children at home, effectively, £8,000 a year of in work welfare. Removing that economic incentive is the most powerful thing we can do to reduce levels of migration back to what the British people and I want to see.

Question

Prime Minister, you say if you don’t get your way in the renegotiation, you rule nothing out. For the purposes of clarity for the British people, does that mean, if you do not get what you’re laying out here, you would be prepared to say it is time to leave the EU?

Prime Minister

What it means is exactly what it says. Everyone knows what I want to achieve. As Prime Minister, I want to go to Brussels. I want to achieve the negotiation. You can hear from me today that what we’re changing in welfare to cut migration is absolutely key to that negotiation, and I want to come back; I want to put that in a referendum to the British people, on an in/out basis, and I want to say, I think, on that basis, we should stay in the European Union. That is what I want to achieve.

Now, people have asked me a lot, “What if you fail”? I don’t want to fail. I don’t believe I’m going to fail, but to put it beyond doubt, I’m saying today, if I do fail, I rule absolutely nothing out. If I fail, we’ll have a press conference like this. You can come along and ask me the question, “Mr Cameron, what do you now advise the British people to do?”, and I’ll give you a very clear answer.

But people know what I want. I want this change. We shouldn’t have to leave the European Union because we can’t fix some of these key problems. Fix the problems; hold the referendum; advise to stay in. That’s what I want to achieve but, if I don’t, I’m absolutely clear, nothing – and I mean nothing – is ruled out.

Question

Prime Minister, at the beginning of the speech, you said that this boiled down to the issue of control. What new controls are there here? It did seem that you failed in that control of trying to get immigration down to tens of thousands, so what new actual controls? It’s all about incentives, isn’t it?

Prime Minister

The biggest control contained in this speech is that, if you reduce the massive cash incentive for people to come from Europe to our country, they are less likely to come. I think that’s absolutely clear from all the work done by the analysts and the experts and Open Europe and everybody else. That is far more powerful than trying to negotiate some arcane mechanism within the EU, which would probably be triggered by the European Commission and not by us. So this is the way to cut migration within the EU.

You’ve heard the figures: over £8,000 a year of in work benefits for people who come and work here. I think the British people will understand that is a bigger incentive, a bigger element of control, than anything else that is available, so let’s do everything that we can to deal with these issues of welfare, because therein lies the answer to the question that we seek.

I think it’s a very simple thing to explain to people, very clear. In future, if you are from the European Union and you come to Britain looking for a job, we will not pay you unemployment benefit, point 1. If you stay for longer than 6 months without a job, you will go home, point 2. If you get a job and you stay here in Britain, you will not get in work benefits, housing benefit, Universal Credit, all the other benefits. You will not get those until you’ve paid into the system for four years, point 3. Point 4, if you come here and you work and, even after the 4 years when you get those in work benefits, if your children and your family is at home in your home country while you’re working here, the child benefit will not go from Britain to that country, point 4. Those, I think, are very significant very clear changes, changes that I think every family in Britain will identify with, understand and support.

And so I believe, when I go to Europe to make these negotiations, I will have the overwhelming support of the British people behind me saying, “What the Prime Minister is asking for is plain, decent, reasonable, fair common sense”. And if Europe says no to that as the basis of our country staying in this organisation, then people will want a pretty good explanation why and, frankly, so will I. That is what we’re going to do. I think it’s very clear, very powerful, far more powerful than any mechanism determined by the European Commission or anyone else. And it’s an argument I look forward to taking on to every doorstep of this country between now and the next election.

Question

You say you want to cut the number of EU migrants to this country. I wonder what you’d say to businesspeople who’ve relied on the flow of EU migrants to provide a flow of skilled labour and, let’s be honest, also cheap labour. And do you accept that this – your proposal to cut tax credits being paid to people on low wages – will affect the business models of some employers?

Prime Minister

Well, I look forward to the debate with business leaders about this. I think they recognise that overwhelmingly Britain’s place in Europe needs to change, and on the basis of that change we should stay in a reformed Europe, so I sense very strong support on that agenda.

I think on the agenda of making sure we have well trained, well paid and an effective workforce in Britain, business knows, as I said in my speech, we need to continue to reform education so that we’re turning out of our schools and universities, people who are job-ready, work-ready and effective, and we need a welfare system where it pays to work, not to stay idle. And if we change those 2 things and we work with business in order to deliver that, I see no problems from any of these proposals.

And here we are in a business that is massively invested in the government’s apprenticeship programme. During this parliament, we would have trained 2 million apprentices. In the next parliament, we’re going to train 3 million apprentices. It’s that sort of work that is going to make sure we can train up people in our country, far too many of whom are still unemployed, in order to do these jobs.

A figure I saw the other day struck me: in London in the last 4 years, we’ve created a third of a million new jobs. 330,000 more people are employed in our capital. How much has unemployment come down in our capital? It’s a figure of 60,000 to 70,000, so we need to make sure that, as we create jobs, we are more effectively reducing unemployment, under-employment, non-participation, and that we don’t leave behind people who leave our schools without the qualifications that they need. Business, I think, is totally up for this agenda; they know that’s a much more secure and strong way to grow your economy over the medium and long term.

Question

Prime Minister, why on earth has this taken so blinking long? There are Tory MPs, there are Tory activists who’ve been saying this for 10 years. This is like a rotten old tooth that you’ve been ignoring, and that is the real problem here and that is why UKIP have gone so far.

Prime Minister

What I’d say is, look, first of all, we haven’t ignored it. I got in as Prime Minister and immediately took a whole series of steps on immigration that have made a difference: the closing of the bogus colleges; the cap of 20,000 on economic migration; we’ve cut family reunion by a third; we reduced the number of student visas because of the bogus colleges. We took a lot of steps that made a difference.

But I think you make an important point in 2 regards. One is, I have been in a coalition government with a group of people who are not knowingly enthusiastic about controlling immigration. For instance, the changes we’ve just made, which are important, saying we’re going to make it more difficult to get a driving licence, to get a bank account, to get a council house, to have privately rented accommodation; that was like pulling a tooth. I got it through and it’s coming into place. But for instance, the checks I want private landlords to make, they start in the next couple of weeks, they start actually in the West Midlands. I want them to be all over the country tomorrow, but I’m in a coalition and sometimes that can be frustrating, trying to bring the brethren who care less about these issues along with you. So that will make a big change.

But, I think where you make an important point is these economic incentives, I think, which are so much at the heart of the change we need to make. And I think we’ve done some things on those, as I said, taking away housing benefit from EU jobseekers who come here, but we need to go much further and much faster, and I think this is the absolute key to solving this problem. And sometimes in politics things take time because you’ve got to think through all of the angles and work out how you’re going to achieve it.

But look, I want to be Prime Minister after 7 May. I believe if we fight a hard campaign I can be Prime Minister after 7 May. I don’t want to do it on promises I can’t keep. What I’m saying today is negotiable, it’s doable and, what’s more, it will work. Now, I would agree with you, I wish we’d done more of these things 2, 3, 4 years ago, but I’ve got a very clear set of measures that will make a very big difference and it builds on work that’s already done.

Question

You cited Open Europe in your speech; Open Europe’s figures show that, even if you’re on the minimum wage and you lose your tax credits, a Pole or a Bulgarian will have a financial incentive to come to the UK. Why are you sure that these measures will repel people from coming to the UK? And secondly, does this require treaty change in your mind?

Prime Minister

The answer to the second question is yes. These changes, taken together, they will require some treaty changes. There’s a debate in Europe about exactly which bits of legislation, which bits of the treaty you’ll need to change, but there’s no doubt this package as a whole will require some treaty change, and I’m confident we can negotiate that.

On the point about Open Europe, I’d make 2 points. One is, of course, if you reduce – you know, take away over £8,000 of potential cash incentive in a year, that makes a huge difference whichever European country you’re coming from. But if you look at the Open Europe report, they actually find – and they’re issuing some research on this, I think – they actually find that this will radically reduce the incentives for people coming from some countries to such an extent that they would actually be better off staying in their own countries and working in their own country’s wage and benefit structure rather than coming here. So I think you’ll find that the evidence is pretty compelling for that too.

Question

Prime Minister, 2 quick questions: you talk of a new fund to help schools that have issues with immigration and public services. Any more detail on that, how much money will be in that fund?

And secondly, if I may, on the separate issue of Andrew Mitchell. Do you see him returning to government? Should he even resign his seat? And do you think PC Toby Rowland is owed an apology, please?

Prime Minister

Taking the first question: the fund, I think it’s – look, it is important, even with a reduction in immigration, there’s no doubt that some communities face particular pressures because of the structure of the labour market and other factors, and so I think a fund that can more directly help those communities would be very worthwhile and that’s what we’ll put in our manifesto and put in place.

On the issue of Andrew Mitchell, I mean let me be clear, you know, it is never right to be abusive or rude to a police officer. I think that’s extremely important. But look, we’ve had a court case now, that’s how we do things in this country. The judge has made very clear his verdict, and I think everyone should accept that verdict and move on.

Question

I wanted to ask you, why do you think non-EU migration has reached 168,000 in the past year, and what do you intend to do about that?

Prime Minister

On the non-EU migration, as I said, we took a number of steps that have made a difference. If you look across the sort of 3 big areas which are students, family migration and economic migration, putting a cap on the economic migration has been effective. Also getting rid of, completely, the ludicrous situation the last government had where they had a whole tier of their immigration system for non-skilled migrants from outside the EU; we just closed that down altogether. In terms of family reunion, because we’ve said the families you come to need to have a certain income, that has cut visas by around a third.

But what we’ve seen, I think, in recent years is just huge pressures that, wherever you find a change, people find another way around it and so we need to take further action, such as the further action I’ve set out in this report today. And I think that the key thing is, as I’ve said, it isn’t just the action you take at your borders, it’s also, you have to take action inside your country, to make sure that people who are here have a right to be here in terms of housing, health service, driving licence, bank account and all those other measures. If we take all of those measures, I see no reason why we can’t make further progress to get the non-EU migration down to a reasonable level.

And, that shouldn’t disadvantage bona fide universities attracting bona fide students. But we’ve seen appalling examples of bogus students and indeed bogus colleges which we need to keep a permanent watch out for and close them down as they appear.