Artistic Tensions

A speech by Glenys Stacey, Chief Regulator at the ASCL (Association of School and College Leaders) Annual Conference

I would like to start by apologising for the terrible play on words that provides the title for this speech. I use it as it does serve rather neatly to summarise both the complexity of educational systems and our job, as the regulator, to design a ‘multi-coloured’ assessment approach on the blank canvas that has been provided by GCSE reform.

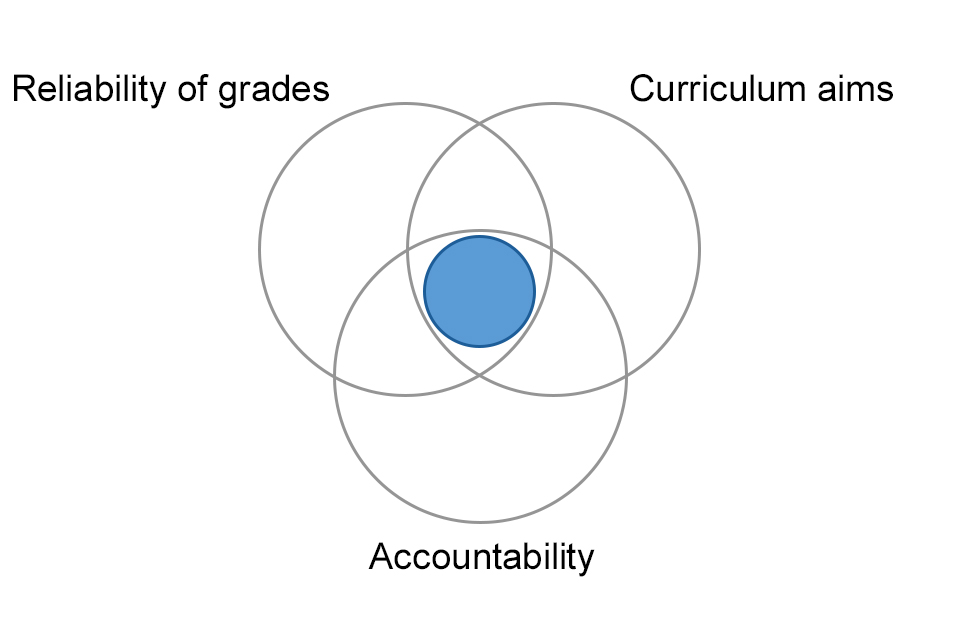

Let me begin by outlining why the qualification and assessment system, and decisions about the shape of key qualifications are particularly testing - so to speak. We (students, schools, society at large) have three essential expectations of GCSE, AS and A levels. First and foremost, they must meet and deliver the curriculum aims in each and every subject. I say first and foremost, because it is just that. The most important expectation we should all have of these qualifications is that they meet and deliver the curriculum aims - and yet this is rarely given prominence in public debate.

Secondly, in this country we put a great deal of reliance on individual grades, on results: employers and those in further and higher education expect to be able to rely unquestionably on those grades to differentiate between individuals, for selection purposes. These expectations are not always as strong in other countries, or grades so granular.

And thirdly, the grades students achieve are central to how schools are judged - central to accountability. And for the first time, as one of the stated purpose of new GCSEs, they should be able to be relied upon for accountability purposes.

So, three different expectations: curriculum, reliability, accountability. That is straightforward enough, you might think. But in practice, they are often enough in tension, pulling any one qualification in several directions at once. I appreciate that not everyone thinks of qualifications in quite this way. It may be the particular perspective of the regulator, and how we see things. Let me paint a simple picture for you - not a work of art, but three circles showing how the three different expectations relate.

Looking at the curriculum first of all, back in 2013, the then Secretary of State for Education called for GCSEs to be made more challenging so pupils are in future better prepared for further academic or vocational study, or for work. As a result, new GCSEs generally have a fuller curriculum, and more curriculum specificity - more detail.

Turning to accountability, the way schools are to be judged is changing, with the move to Best 8, away from the strong emphasis on grade C towards attention to all grades for all students. There is a strong desire to know how well schools deliver across the whole curriculum, with GCSEs in particular embodying the curriculum. And performance league tables are often considered by parents to be an important source of information when looking to decide the right school for them, for their children.

In turn, we, as the assessment regulator, want to know that grades are reliable, as do others who rely on them. We want to know that each qualification differentiates fairly between individual students, as they and others make decisions about their futures.

These are three strong, competing pressures. In considering how assessment should be designed for each qualification, we always look to find the small zone of possibility, where the circles overlap.

In considering how assessment should be designed for each qualification, we always look to find the small zone of possibility, where the reliability of grades, curriculum aims and accountability are all considered.

Sometimes this is straightforward. An example would be our decision to move from modular assessment for GCSEs, with students now assessed at the end of their period of study. In other cases a default position can be reached. In 2013, for example, we proposed that reformed GCSEs should be untiered, so that all students are prepared and entered for one common set of assessments. However, there are some exceptions – in maths for example – so as to provide valid assessments and reliable results for all students. If untiered, maths exams would inevitably include some questions that would be too challenging for some students and insufficiently challenging for others. That could the case for any subject, you may say, but it is a significant issue in maths, given the nature, the breadth of the subject and the unusual spread of student ability as they begin their GCSE maths studies.

So, we’re often not looking for just one answer; the tensions typically play out differently between qualifications. And as a result, we have considered each GCSE, and A level, subject by subject, considering these tensions and how each qualification may play out in practice, in schools, in the real world.

In addition to tiering, we have considered in each case whether a minimum exam time should be specified; whether non-exam assessment should be used, and if so its weighting; whether non-exam assessment should be externally set and/or externally marked, and how it should and could be moderated. As we have considered these things we have kept at the forefront of our minds two things in particular: the curriculum aims, and what is manageable and deliverable in schools.

Before reaching any conclusions we have consulted, to ensure we have heard the views of stakeholders, such as yourselves. We have then reflected on what we are told, and thought carefully before making what are sometimes difficult and finely balanced decisions.

Some of these have been contentious. In GCSE science for example, it is abundantly clear that non-exam assessment has not worked in this subject. Accountability has squeezed out the curriculum aims, and also brought the reliability of grades into question. We’re looking to reset the balance. In our view, given the competing tensions I have spoken of, non-exam assessment should be used when it is the only valid way to assess essential elements of the subject. For the sciences, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that well-written questions can appropriately test candidates knowledge of scientific experimentation, and that is the route we have chosen - to protect the curriculum aims and restore practical work to its proper place, enabling students to learn from it throughout their course of study rather than simply rehearse it for summative purposes at the end.

I hope that provides an outline of what we are trying to achieve, and how we approach things. Some people express concerns that we are not finishing our ‘masterpiece’ in one sitting. Indeed, our canvas will not be complete for three years. It would simply not have been possible for either us or the exam boards to have been deliberate enough with our strokes if attempting to reform all qualifications simultaneously. We would have more likely ended up with a Pollock than a Constable (no disrespect to Pollock). So ours is a pragmatic approach, doing what is possible, and delivering reform over a relatively short period.

Most decisions have now been taken. The three GCSEs that have the highest entries, and were most in need of reform - Maths, English language and English literature – will be first taught in September. Another 20 subjects will follow in September 2016 and a range of new GCSEs will be available from September 2017. This last group is not yet confirmed. We have asked exam boards to make proposals to us for the development of new subjects and we have judged their submissions against a number of principles - for example, that they can differentiate students sufficiently well on assessment. We will next week publish a list of those subjects that have met our principles and those which we believe require more work. However, I should stress that meeting the principles is not a guarantee that a subject will follow in 2017, nor is not being on the list confining the subject to the cutting-room floor. If a proposal can be brought forward we will consider it, and if good content that can be well assessed cannot be developed we may have to think again.

Another good example of giving ourselves time to think is the work we are currently undertaking to reassure ourselves, the exam boards, students and other stakeholders about the level of demand and difficulty across the sample assessment materials for the four newly accredited GCSE maths specifications. More than ever, schools presume the standard is embodied in the sample assessment materials, and yet in maths they look different in style, board by board. We are testing the demand of each board’s sample assessment materials and comparing them to current maths GCSEs and equivalent qualifications in other countries. Some 4,000 students across England are sitting the sample assessments as part of our research.

We’re now roughly halfway through that research and are making good progress. We have gathered all the data we require against two of three research strands and that is now being analysed. In addition, we are today announcing a fourth strand to provide further reassurance, with no delay to our end-April deadline for completing this work.

As well as taking time to get the design right, we want to be in a position to ensure the final results are framed correctly. We know that it takes a few years following any programme of reform for the system to settle down. It takes time for teachers to gain confidence in their ability to teach the new curriculum and those who use and observe new assessments to be reassured that they are achieving their goals. It is therefore important that early students are not disadvantaged in any way relative to those that have gone before or will come in the future. When the first results for reformed qualifications in Maths, English language and English literature are delivered in 2017, we will have used statistical evidence to make sure, as far as possible, that does not happen.

In the future, we will complement these data with evidence drawn from a national reference test. Such a test is not a panacea, but we know from the deployment of similar tests in other parts of the world that they can provide a rich source of additional information. We are planning a small trial of a test later this year, with a full cohort trial in 2016. The test will become live in 2017, but we would not want to read too much into one year’s data. Only after a few years will we be truly able to assess the weight we should place on it relative to our other sources of information.

Finally today, I’d like to talk about how I believe we, as the regulator, and you, as the teaching profession, have a shared a responsibility to hold the brush of qualification reform. When I last came to speak at ASCL in 2012, I said that Ofqual should make commitments to the teaching community in three areas:

- first, we should listen and engage more deeply than we had managed previously;

- second, we needed to explain better how the system works;

- third, we needed to manage qualifications reforms in a way that minimises the risks and reflects the challenges you face.

I also tentatively suggested some commitments that you - the leaders of schools and colleges - might consider in return. They included supporting a culture of professional ethics.

I hope from what I have said today, and the way we have conducted ourselves over the past few years, that you will agree we have tried hard to meet our commitments. And I am delighted that ASCL has recently published its Blueprint for a Self-Improving System. We can both see that collaboration and partnership will help to deliver success, and that teachers must be the agents of their own accountability. So we are working to match your commitment to develop an assessment ethics framework, with a commitment of our own, to work with you to deter malpractice and ensure a more level playing field for all students. If we work towards these commitments together, I believe on final viewing our assessment picture will be well received by the critics.

Thank-you.