When laws become too complex

Published 16 April 2013

1. Foreword

Legislation affects us all. And increasingly, legislation is being searched for, read and used by a broad range of people. It is no longer confined to professional libraries; websites like legislation.gov.uk have made it accessible to everyone. So the digital age has made it easier for people to find the law of the land; but once they have found it, they may be baffled. The law is regarded by its users as intricate and intimidating.

That experience echoes observations that have been made about statute law for many years. The volume of legislation, its piecemeal structure, its level of detail and frequent amendments, and the interaction with common law and European law, mean that even professional users can find law complex, hard to understand and difficult to comply with.

Should we be concerned about any of this? After all, modern life in a developed country like the UK is complicated, and we use the law to govern many aspects of it. So it is not surprising that statutes and their subordinate regulations are complex; and it is perhaps reasonable to assume that citizens will need help or guidance in understanding the raw material of law.

But in my view, we should regard the current degree of difficulty with law as neither inevitable nor acceptable. We should be concerned about it for several reasons. Excessive complexity hinders economic activity, creating burdens for individuals, businesses and communities. It obstructs good government. It undermines the rule of law.

Last year I commissioned a review of the causes of complexity in legislation. This is the report. It suggests that there is no single cause of complexity, but many. That is perhaps not surprising. But for me, a striking theme of this report is that while there are many reasons for adding complexity, there is no compelling incentive to create simplicity or to avoid making an intricate web of laws even more complex. That is something I think we must reflect upon.

I believe that we need to establish a sense of shared accountability, within and beyond government, for the quality of what (perhaps misleadingly) we call our statute book, and to promote a shared professional pride in it. In doing so, I hope we can create confidence among users that legislation is for them.

That thought is at the heart of the good law initiative, which the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel is launching with the support of Ministers. Good law is necessary, effective, clear, coherent and accessible. It is about the content of law, its architecture, its language and its accessibility – and about the links between those things. It is an initiative that I hope will engage government departments, drafters, the policy profession, parliamentarians, the judiciary - and, crucially, the users of legislation.

Richard Heaton First Parliamentary Counsel and Permanent Secretary of the Cabinet Office

Stay up to date with the latest good law publications, news stories and guides.

Watch a video of Richard Heaton speaking at TEDx Houses of Parliament

Richard Heaton at TEDx Houses of Parliament

2. Background

I wish that the superfluous and tedious statutes were brought into one sum together, and made more plain and short.

Edward VI (1537 – 1553)

A number of government commissions and parliamentary committees have attempted to revise and reorganise the statute book:

- One Act of 1867 alone repealed over 1300 statutes.

- In 1875 a select committee was appointed to consider “whether any and what means can be adopted to improve the manner and language of current legislation”.

- In 1965 the Law Commission was established “for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law”.

- In 1975, the Renton Report made presented 121 recommendations to improve the form and drafting of legislation.

Most recently, the Commons Select Committee for Political and Constitutional Reform launched an inquiry on Ensuring standards in the quality of legislation in January 2012. It is due to publish its report later this year.

And much has been done in response. The Law Commission has, in its 47 years, promoted a large number of reforming, repealing or consolidating Bills.

Parliamentary Counsel has adopted a plain English style which would have been unrecognisable to their 1970s predecessors, as well as a culture of innovation over precedent.

Improving Parliamentary and public scrutiny of legislation has been a government objective in recent years, seeking to improve both democratic engagement and legislative quality. Bills are often now published in draft.

The government is also pursuing a drive to remove unnecessary burdens on citizens and businesses. The Red Tape Challenge, and a ‘One In, Two Out’ approach (this measure has been introduced in January 2013 and builds on the positive results obtained by the previous One In One Out approach), characterise this:

- controlling the number of new regulatory measures;

- assessing the impact of each regulation;

- reviewing the effectiveness of regulatory measures;

- reducing regulation for small businesses;

- improving enforcement of regulatory measures;

- promoting the use of alternatives to regulation; and

- reducing the cost of EU regulation on UK business.

Red Tape Challenge reforms are already saving businesses over £155 million per year, with many further savings not yet quantified. By removing and reducing the burden of red tape, it is estimated that by July 2013 Government deregulation will reduce the annual cost to business by around £919 million. (See the Fifth Statement on New Regulation. The government is committed to publishing a Statement of New Regulation (SNR) every six months, giving an account of all the regulatory measures which are scheduled to be introduced in that SNR. The latest statement covers activities planned until June 2013, therefore savings from most of these measures have not come into effect yet.) 90 One In Two Out measures will be implemented over the first half of 2013 with an anticipated net annual saving of £71 million to business. Over 50 RTC measures will generate a further net annual saving of about £12 million.

Other countries too have made efforts to simplify and systematically reshape their statute book.

The Australian government recently adopted new standards for clearer and simpler legislation. In the United States deregulation has been a priority for virtually every administration since the Nixon presidency.

Most European countries have set up processes to simplify national legislation and established departments dedicated entirely to better regulation and reform of the law.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has been championing better regulation practices and has launched a number of initiatives to harmonise legislative codes of practice. The 2005 Guiding Principles for Regulatory Quality and Performance, endorsed by all OECD member countries, advised governments to “minimise the aggregate regulatory burden on those affected as an explicit objective, to lessen administrative costs for citizens and businesses”, and to “measure the aggregate burdens while also taking account of the benefits of regulation”. The 2005 Integrated Checklist on Regulatory Reform promotes regulation that “avoids unnecessary burdens on economic actors”. Analyses in this policy area have been presented in different publications such as Cutting Red Tape: National Strategies for Administrative Simplification (OECD, 2006) and From Red Tape to Smart Tape (OECD, 2003). Find out more, including by country.

Emerging economies are piloting innovative approaches to drafting (such as the collaborative lawmaking project Zakon in Russia) and highly participatory legislative processes (for example, the e-Democracia initiative in Brazil promoted by the Brazilian Parliament).

2.1 Government drafters

The Office of the Parliamentary Counsel was established in 1869 in order to professionalise and improve the drafting of government bills.

The Office comprises a team of experienced government lawyers who specialise in preparing legislation. It is responsible for drafting all government bills, translating policy into laws which are as clear, effective and readable as possible.

The key responsibility of Parliamentary Counsel is to subject policy ideas to a rigorous intellectual and legal analysis, and to clarify and express legislative propositions. The drafting stage is often the first at which the policy as a whole is subjected to meticulous scrutiny.

Departmental lawyers, rather than counsel, are generally responsible for drafting secondary legislation. But counsel will usually be consulted if the secondary legislation amends primary legislation, or if it raises a particularly important question of law or drafting.

Having a dedicated and autonomous division of senior lawyers responsible for drafting primary legislation is a common arrangement in most commonwealth countries. Elsewhere, for example in the US, France, Germany and the rest of the EU, practice varies. Legislative drafting is often a responsibility of Parliament or of individual departments.

Counsel also advise departments and ministers on Parliamentary procedure, and on handling Bills during their passage.

3. Features of complex legislation

Often, when complaining about poor quality legislation, commentators are really criticising the political and ideological considerations that lie behind a Bill. A judgement on the substantive merits and objectives of legislation is outside the scope of this paper. We will instead consider the confluence of factors that affect users’ experience of legislation, including aspects related to:

- volume

- quality

- perception of disproportionate complexity

3.1 Volume – the length of the Statute Book

There seem to be several different approaches to measuring the volume of legislation. Some reports only consider the number and page-count of Bills introduced to Parliament; others refer to government-sponsored Acts and Statutory Instruments or include legislation passed by devolved administrations. Some data-sets are based on parliamentary sessions and others on calendar years.

However, there seems to be no disagreement on overall historical trends:

- The volume of legislation increased significantly in the inter-war period, a period of radical social and economic changes.

- The average number of government Bills in a typical parliamentary session is between 35 and 50 depending on the length of the session.

- The number of Acts promulgated in recent years is consistent with trends in previous decades; in fact, the average number of Acts has slightly declined over the past 40 years.

However:

- It is extremely difficult to estimate how much legislation is in force at any one time.

- The average length of Bills introduced to Parliament seems to be significantly greater than in previous decades.

- Multi-purpose Bills (sometimes called ‘Christmas Tree’ Bills) are more common than they were.

- Between 1983 and 2009 Parliament approved over 100 criminal justice Bills, and over 4,000 new criminal offences were created. In response to that trend the Ministry of Justice has established a procedure to limit the creation of new criminal offences.

The total number of pages of legislation passed each year, and the average number of pages per Act, are often used to demonstrate an increased volume of legislation. But modern drafting styles and publishing formats have increased the amount of white space and therefore the page count; and therefore this is only a partial indicator.

The amount of delegated legislation has increased significantly in the past decades, both in terms of the number and length of SIs: from around 2,000 a year until the late 1980s to around double that in 2006.

It is important to note that the increased length of Acts is not automatically and in itself a feature of complex legislation. Shorter Acts can be even more complicated than long ones as they may not include all the detail and explanation required for the law to achieve the policy objectives effectively. A short Act that requires the user to go to a complicated set of Regulations is not, overall, a simplifying measure.

3.2 Volume of Government Primary Legislation

| Year | No of Acts | Total no of pages | Average no of pages |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1959 | 69 | 1163 | 17 |

| 1969 | 59 | 1542 | 26 |

| 1979 | 40 | 688 | 17 |

| 1989 | 40 | 2290 | 57 |

| 1999 | 32 | 2003 | 63 |

| 2009 | 23 | 2247 | 98 |

(House of Lords, Library Note, LLN 2011/028)

One of the key reasons for the increased volume of legislation may be that interest groups and individuals are becoming increasingly demanding of each other and expect the legislature to arbitrate on respective rights and duties, defining rules of engagement and setting boundaries to the unpredictability of life.

As well as creating or abolishing enforceable rights, legislation plays a role in reinforcing policy initiatives, reiterating collective commitment to specific targets, reaffirming moral or ideological principles, or simply reassuring the public that their concerns are taken seriously and their interests are respected by lawmakers.

Historically, legislation has been regarded as a relatively straightforward tool to influence the political debate inside and outside Parliament. It can be a currency in negotiating alliances and building consensus, and a system to limit the discretion of future administrations. Non-legislative approaches often require lengthy negotiation with external stakeholders and do not always guarantee immediate certainty of result. Nor do they have the democratic endorsement that legislation implies.

Setting out policy targets in legislation (a trend that has emerged in the past 30 years) can be “a low-cost way for governments to give the appearance of vigorous action” and a way to strategically influence (or limit) the decision-making of future governments (see ‘Legislated policy targets: committment device, political gesture or constitutional outrage?’, Jill Rutter and William Knighton, August 2012).

Moreover there seems to be an asymmetry in legislation: to legislate is usually considered to be a more effective approach than non-legislative options and, historically, it has been easier to legislate than to repeal. Legislation is perceived as a sign of action and therefore it is a powerful communication tool.

3.3 The impact of EU obligations

In the past, various attempts to assess the role that EU (and other international) obligations play in increasing the volume of UK legislation failed to provide consistent conclusions. Nevertheless, a paper commissioned by the House of Commons in 2010 reviews various assessments (see ‘How much legislation comes from Europe’, House of Commons Research Paper 10/62 13 October 2010) and suggests that:

- From 1980 to 2010, out of 1300 Acts, 10% incorporated one or more EU obligations and in the period from 1997 to 2009 the percentage of SIs made under the European Community Act 1972 ranged between 9% and 14%. (Varying from 0% of the Ministry of Defence to almost 60% of DEFRA.)

- The estimated impact of EU laws on other member states’ statute books ranges from 6% to 80% for new members. In Germany around 38% of federal legislation is influenced by EU law.

- EU law has a similar impact even on countries that are not members of the Union. For example, the Icelandic Government estimated that 20% of the national legislation passed between 1994 and 2004 originated in the EU.

Moreover, it has been estimated that between one-third and one-half of the total administrative burden on businesses in Europe derives from EU regulation.

Gold-plating (referring to government departments adding burdens to EU laws which imposed extra costs and restrictions on business) has been said to be a ‘British problem’ as most other EU member states have historically adopted a ‘copy out’ approach (see ‘Comparative Study on the Transposition of EC law in the member states’, European Parliament, July 2007 and ‘Burdened by Brussels or the UK? Improving Implementation of EU Directives’, Report for the Foreign Policy Center, Sarah Shaefer and Edward Young, August 2006). A 2003 British Chamber of Commerce study (‘How Much Regulation is Gold Plate?’, Tim Ambler, Francis Chittenden and Mikhail Obodovski, BCC, 2003) attempting to assess the incidence of gold plating calculated that:

- On average, the UK provides 2.6 implementing documents per EU Directive, compared with 1 in Germany and 0.8 in Portugal.

- In 2003 there was an average “elaboration ratio” for the UK of 330%. In an extreme example, Directive 2002/42/EC consisted of 1,167 words in its original English text but resulted in 27,000 words of implementing regulation in the UK.

The Coalition Programme for Government made a commitment to ‘end the so-called ‘gold-plating’ of EU rules’. In 2011 the Government issued the Guiding Principles for EU Legislation (pdf, 83.3 KB), establishing that whenever possible a “copy out” approach should be adopted.

BIS and the BRE are working with their EU counterparts and the OECD to simplify and reduce regulation. A recent BIS report (Gold Plating Review - The Operation of the Transposition Principles in the Government’s Guiding Principles for EU Legislation, BIS, March 2013) shows that the government has been successful in preventing the ‘gold-plating’ of EU legislation. Since the 2011 Guiding Principles have been in place, there has been very little evidence of gold-plating of EU legislation placing new burdens on business.

However, regulation implementing EU directives is currently outside the scope of the “One In, Two Out” programme and is exempted from the scrutiny of the Regulatory Policy Committee.

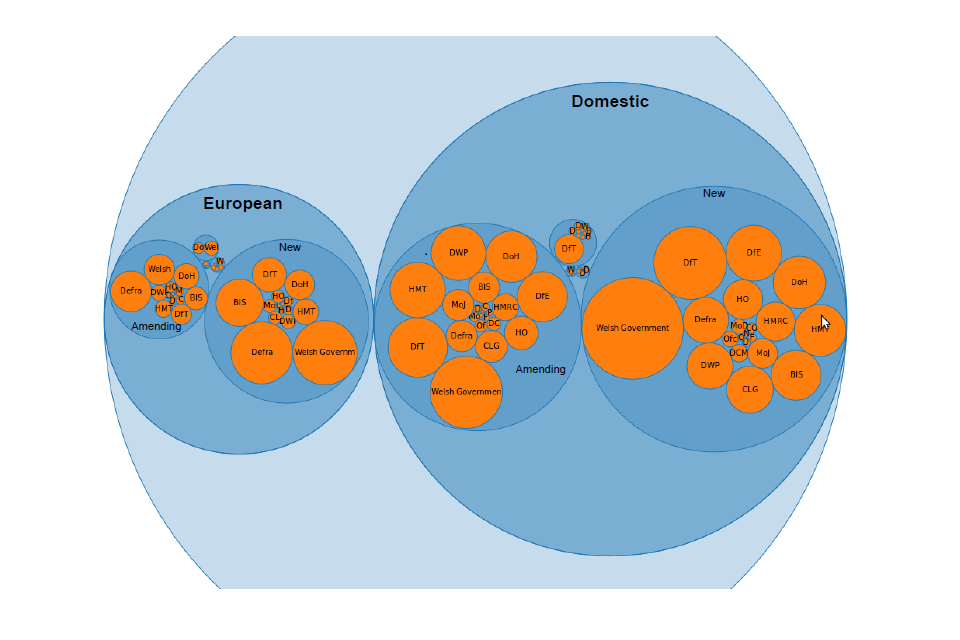

The following diagram, compiled by legislation.gov.uk illustrates the volume of new regulation originated in the EU and clearly shows that Defra and BIS have been the large implementers of new EU driven regulations. The diagram also shows the impact of devolution to Wales.

Chart showing European and domestic regulations by size, indicating that Defra and BIS have been the largest implementers of new EU driven regulations. The diagram also shows that Welsh devolution has had a big impact on creating new legislation.

3.4 Quality

When asked to describe the characteristics of good legislation, those involved in its preparation tend to mention various combinations of the following features:

- it addresses political objectives

- it addresses social objectives

- it addresses legal objectives

- it operates as efficiently as is practicable

- it is intra vires (the lawmaker has sufficient legal authority to make the legislation)

- it is consistent with (or effective in overriding) identified basic principles

- it is sound in substance: a well-thought-out, full and harmonious scheme

- it is clear, as simple as possible and well-integrated with other laws

- is consistent with current legislative drafting styles and best practice

- has been produced in time and efficiently (without using excessive resources).

But these are contributing factors, and our contributors did not feel confident that an exhaustive and agreed definition of high quality legislation was achievable, nor that a checklist approach should be adopted.

3.5 Engagement and the Public Reading Stage

Transparency, engagement and innovation are Government priorities that are seen in projects such as data.gov and the Red Tape Challenge.

Could public engagement by digital channels also improve the quality of legislation?

Participatory lawmaking may seem a radical direction to take; but there could be specific cases where a more collaborative approach would help to identify pitfalls in the legislation and ensure that implementation is as efficient and effective as possible. A participatory, yet controlled, digital environment could ensure that relevant contributions and specific expertise are harnessed and translated into legislative text.

Public participation could be particularly appropriate and beneficial to the preparation of selected secondary legislation. A more participatory process combined with increased emphasis on alternatives to regulation may help to substantially reduce the burden of regulation on communities and businesses.

After piloting a Public Reading Stage the Coalition Government has reconfirmed its commitment to such engagement. (The Government has conducted two pilot public reading stages on the Cabinet Office website, in respect of the Protection of Freedoms Bill in February/March 2011 and the Small Charitable Donations Bill in August/September 2012. In addition, an online consultation was conducted by the Department of Health on the draft Care and Support Bill, which is currently undergoing pre-legislative scrutiny by a joint committee of both Houses.) The pilot results indicate that approaches to consultation should be carefully tailored to the bill and the Government has therefore decided that the public reading stage will not be introduced as a matter of routine for bills. Instead the Government will consult on legislation according to the Consultation Principles introduced last year. These seek to ensure a more proportionate and targeted approach, so that the type and scale of engagement is proportional to the potential impact of the proposal.

At an international level, there are several successful initiatives that draw together the diffuse participation of individuals and minority groups: e.g. regulations.gov in the US, osale.ee in Estonia and edemocracia.camara.gov.br in Brazil.

Interest groups and constituents already draft amendments for MPs in the UK. Platforms like POPVOX in the US and eDemocracia in Brazil help to make this process more transparent and allow citizens to lobby and inform their MPs more effectively and in a open forum.

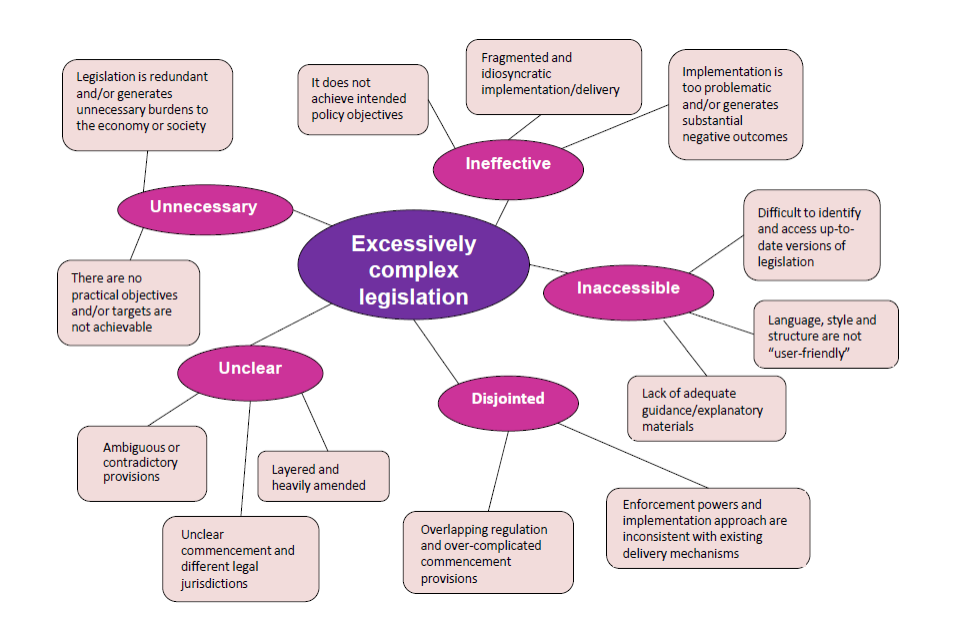

Chart showing reasons for excessive complexity in legislation - these include the legislation being unnecessary, unclear, ineffective, inaccessible and disjointed.

3.6 Perceptions of over-complexity

Although legal education modules are available to secondary school students and adult learners, the level of confidence of the public when dealing with legislation is very low. Citizens tend to find the statutes and regulations difficult and intimidating.

Even legally qualified users frequently complain about the excessive complexity of legislation and often tend to read the explanatory notes accompanying the Bill, rather than the legislative text.

The architecture of the statute book further discourages users because changes to existing legislation (generating very complicated sets of interrelationships or ‘legal effects’) are not explicit and new and existing legislation can appear inconsistent. Regulation emanating from different sources sometimes overlaps and commencement can be difficult to follow.

Every year, new legislation and amendments result in over 15,000 (over 30,000 when considering secondary legislation) legislative effects. The statute book therefore is an ever-evolving network of complex information that expands organically and is extremely difficult to map.

The vast number of legislative effects and their complex interconnections mean that currently the legislation.gov.uk database is not currently entirely up-to-date. However, the National Archives are tackling this problem via their Expert Participation Programme.

3.7 Legislation as data and the architecture of the statute book

The sheer volume and variety of legislation creates an information-access problem that can be detrimental to businesses and discourages public understanding of government aims and priorities. Computational legal studies offer the opportunity to develop formal, practical infrastructures to enhance access to legislation.

Computational legal studies emerged over a decade ago in the US and are based on the premise that legislation, as any other sets of complex and intertwined information, can be analysed and organised according to mathematical models. Adapting scientific research approaches to the study of social sciences is increasingly common (e.g. behavioural economics borrows methodologies and research approach from game theory and biology).

If we look at statutes as data, then legislation can be formalised (and visualised) as a mathematical object, a hierarchically organised structure containing language and explicit interdependence between provisions. (See work done by Daniel Katz and Michael Bommarito, including their analysis and visualisation of the full US Code: ‘A Mathematical Approach to the Study of the United States Code’, Michael Bommarito and Daniel Martin Katz, 2010.)

It is possible to process and organise a vast quantity of data (consider the amount of data on the internet and how search engines allow us to access it in a relevant, fast and consistent way). Therefore, practical application of computational legal studies can include visual representation and analysis of legal information and ways to process and exploit information expressed within these representations.

This approach could potentially be used to provide access to legislation in a more user-friendly and efficient way. For example, providing legal information that is highly tailored to a specific problem, linked to relevant guidance materials and with up-to-date notifications on commencement.

Legal information is most useful if it is understandable, timely and relevant to the issue we are trying to address. Preferably, it should be enough to cope with the problem and offer defined options. It should also be easy to put into practice and provide reassurance to the user.

The potential application of computational law principles to improve the accessibility and usability of legislation (and related guidance) could be especially crucial in changing users’ negative attitudes toward legislation, helping individuals and businesses to feel relieved of excessive burdens of regulation.

legislation.gov.uk is already committed to radically improving the way users access and interact with legislation. It is also championing the transparency and open data agenda (e.g. the site’s application programming interface or API allows open access to the government’s legislative database - find out more).

The Expert Participation Programme, announced in July 2012, is a pioneering initiative to bring legislation on the site fully up-to-date. The programme involves developing new tools to make use of natural language processing to automatically detect changes in legislation and to obtain information earlier from government departments drafting new laws.

The diagram below is a visualisation of the legal effects related to one Act (the Companies, Audit, Investigations and Community Enterprise Act 2004). It represents the proportion of the statute book to be taken into consideration when looking at the current in-force state of just that one Act.

Visualisation of the legal effects related to one Act (the Companies, Audit, Investigations and Community Enterprise Act 2004). It represents the proportion of the statute book to be taken into consideration when looking at the current in-force state of j

However, providing up to date and available sources of legislation is not the end of the issue. Even when legislation is up to date and physically accessible to users, the interconnection between various laws, their geographical scope and their application may not be explicit or may be inconsistent. Implementation procedures (rather than the legislation itself) can intensify the general negative attitude toward the law.

This has obvious implications for the users’ ability to access and comprehend the objectives and impact of legislation. In the case of regulatory legislation, users perceive complying with legislation to be onerous and the law as being extremely difficult to navigate. In particular, in the areas of planning and environmental applications, procedural bureaucracy is perceived to be a problem for businesses. For example, SMEs claim that having the flexibility to decide the sequencing of their planning applications would considerably facilitate compliance. This is why, as part of the Red Tape Challenge, Government is focusing on “smarter implementation” of regulations.

According to ‘Business Perception of Regulatory Burden’, May 2012 (a report by the University of Cumbria’s Centre for Regional Economic Development (CRED) commissioned by BIS), SMEs find it particularly taxing to comply with legislation that they perceive as disproportionately complex and obscure. SMEs often do not have the expertise or resources to keep track of legislation and this increases their apprehension about having to deal with legal requirements.

Terms surrounding the word ‘burden’ (Business Perception of Regulatory Burden, May 2012):

- Threat of being sued

- Compensation culture

- Civil action

- Unreasonable outcomes

- Growth prevention

- Constant regulatory change

- Cost of keeping up-to-date

- Inconsistency

- Confusion

- Tidal wave of information

- Loss of control

Recent studies, including Business Perceptions Survey 2012,, prepared for NAO/LBRO/BRE by IFF Research, ‘Business Perception of Regulatory Burden’, a CRED report for BIS (May 2012) and UKELA and NAO analysis in the ‘State of UK Environmental Law in 2011-2012’ report (May 2012), on the perception of regulatory burden show that:

- ‘Legislative burden’ cannot simply be equated to measureable costs. It embraces other aspects such as anxiety generated by the threat of litigation, uncertainty, the pace of change and sense of inequity.

- SMEs’ perception of regulatory burdens tends to reflect general attitudes towards the law.

- Some SMEs feel so intimidated by employment law that they limit their engagement to the bare minimum, preferring to take the risk of being challenged or fined for non- compliance.

- Users struggle to distinguish between regulatory requirements originating from national government, industry self-regulation and codes of conduct.

- Large deregulatory exercises can have the unintended consequence of increasing the awareness of regulatory burden and therefore increasing the perception of the burden.

- In the assessed companies, legislative changes were almost always perceived as negative when, in practice, they had little impact in most cases.

- SMEs often fail to notice new legislation introducing beneficial changes, for example, when regulatory changes make it more convenient to hire new personnel or apprentices.

- Media “noise” and an emphasis on negative and unintended consequences of legislation exacerbate the perception of unnecessary complexity. Problems often derive more from communication about legislation than from the legislation itself.

Communication about legislation is itself a complex social and political process. However an improvement in the way legislation is presented, made available and explained could dramatically reduce the perception of disproportionate complexity. The mystification of legislation though, seems to be generated by the difficulty that users experience in accessing reliable, clear information on their rights and duties, combined with a lack of guidance on the compliance requirements relevant to them and their specific circumstances.

Behavioural economics suggests that the way information is presented and instructions are perceived, changes people’s attitudes and the way they act/react to certain stimuli.

The CRED analysis found that the way the media deliver information about regulation can generate misunderstandings and, consequently, increase the perception of unnecessary complexity. The resulting potential misinformation and other communication failures could have an impact on the understanding of proposed legislative changes among all legislation users, including Parliamentarians and legally qualified users.

Although after parliamentary debate and amendments only some legislative proposals become law, communication about those provisions has been influenced by the numerous events and interactions that occurred at previous stages in the legislative process.

The way in which information is heard is influenced by the messages users receive, and the user’s interpretation of information is shaped by the specific socio-economic context in which the user operates.

4. Causes of excessively complex legislation

There is no single cause of excessively complex legislation. Complicated procedures, imperfect interactions between the stakeholders involved and the unpredictability of external factors, all contribute – in different ways and at different stages during the life-cycle of law-making – to the creation of unnecessarily complex legislation.

4.1 The audience(s) for legislation and their conflicting requirements

The likely audience for a specific law depends on the context. It is therefore important to identify the likely audiences and their expectations in order to understand what the causes of unsatisfactory legislation are.

The audience of legislation has steadily increased for the past 20 years. In the past, users of legislation tended to be legally qualified; but today’s users are a far wider group of people thanks to the web (legislation.gov.uk has over 2 million unique visitors per month). Government and Parliament, as well as their constitutional roles, are also users of legislation; and their specific requirements have a dramatic impact on laws throughout their ‘life-cycle’. It is not surprising that what is found to be user-friendly for Government and in Parliament may not be the same for the judiciary, who use legislation in an entirely different context. Citizens or businesses will in turn have a different set of expectations and requirements.

Historically we have tended to be more aware of the needs of institutional users (including public bodies such as regulators, devolved administrations, and local authorities). We need to understand better the expectations of the new users of legislation. This group includes a variety of people who access legislation for professional or personal reasons and who may not be familiar with the architecture of the statute book, may not know how to find and access legislation and guidance about legislative changes.

Evidence recently collected by Parliamentary Counsel and legislation.gov.uk suggests that those new users could be, for example:

- human resources staff from a mid-size company who need to understand what impact the Pensions Act 2011 can have on the company

- policy advisors from a local authority, keen to keep up to date with environmental regulation

- landlords who are in dispute with their tenants and may want to represent themselves in court

- Law Centre volunteers who want to understand better the Welfare Reform Act 2012

(See ‘The National Archives & the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel: Legislation.gov.uk and drafting techniques’, a study by BunnyFoot commissioned by TNA and OPC in 2012. The research involved user testing, a survey, and one-to-one interviews with a number of volunteers matching the ‘personas’ that the National Archives have identified as typical users of the legislation.gov.uk website.)

The legislation.gov.uk user study also found that the comprehension level of legislative texts by both legally qualified and non-legally qualified users was generally quite low and that all users found it challenging to read legislation and demonstrate their understanding of it.

- Most users interviewed said that they expect legislation to be hard to read – even barristers. They found that legislation is “convoluted and involves a lot of going back and forward”;

- Navigating a legislative text was problematic – several users did not know what sections or schedules were;

- Users’ understanding of what happens to legislation after it has been enacted is poor – many participants assumed that all legislation on legislation.gov.uk is necessarily in force.

Predictably a lack of familiarity with legislative texts seems to exacerbate problems with usability and perpetuate misconceptions associated with the law.

Unexpectedly, even barristers, judges and academics may find legislation unclear and, occasionally, quite problematic. The Statute Law Society in 2009 found (see ‘The Teaching of Legislation’) that until recently, legislation, legislative techniques and interpretation were often neglected in undergraduate teaching. In order to monitor and improve the quality of legal education, the government established The Advisory Committee on Legal Education and Conduct (ACLEC) under the Courts and Legal Services Act 1990.

The following table summarises the key concerns, expectations and priorities for four of the audience groups for legislation.

| Government | Parliamentarians | The Judiciary | Public users | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concerns: | Concerned about public response to legislation, and about the inherent intricacy of the legislative process (and resulting potential obstacles to enactment) | Concerned about ‘principle legislation’ if uncertain how the Government will implement it. Concerned about bills including obscure and unsubstantiated technical details | Concerned about possible difficulties in interpreting legislation and the unexpected consequences that implementation may produce | Concerned about the burdens that new legislation can cause them and nervous about overlooking changes & their implications |

| Expectations: | Expects legislation that achieves policy (or political) objectives. May require either considerable detail to control delivery, or “principle” or enabling legislation to allow flexibility in policy implementation at a later stage. | Expect legislation that is fit for purpose e.g. properly prepared, with clear policy objectives. Expect legislation that is drafted in a way that is intelligible and supported by explanatory material which substantiates more technical details. | Expect objectives of legislation (and intentions of legislators) to be clear and unambiguous. Expect provisions that allow for flexible interpretation. Expect definitive and coherent commencement orders. | Expect legislation with obvious objectives and clearly defined implications for them/their organisation or community. |

| Priorities: | Bills that get approved in a short time, with few amendments, and that guarantee immediate certainty of result and a positive response from the public. | Bills structured in a way that reflects (and facilitates) the intricate parliamentary scrutiny and amendment procedures. | Legislation ‘drafted for posterity’ that does not limit their ability to apply the law to circumstances that were unforeseeable by legislators | Legislation that is simple, accessible, and easy to comply with and not unnecessarily burdensome. |

4.2 Mapping the causes of unnecessary complexity

The preparation of primary legislation can be broadly described in three main phases.

Phase One starts during the development of policy. The lead department assesses the need for legislation, and conducts a review of the legislative landscape. It then instructs Parliamentary Counsel, who draft a Bill.

In Phase Two, the Bill is introduced to Parliament where it is subjected to scrutiny (and may be amended). It follows established Parliamentary procedures; and if it is passed by each House, the Bill receives Royal Assent and becomes an Act.

In Phase Three the Act is promulgated and implemented.

During each phase there may be a variety of problems and inefficiency that can generate unnecessary complexity, limit the effectiveness of the law or make its use and interpretation difficult.

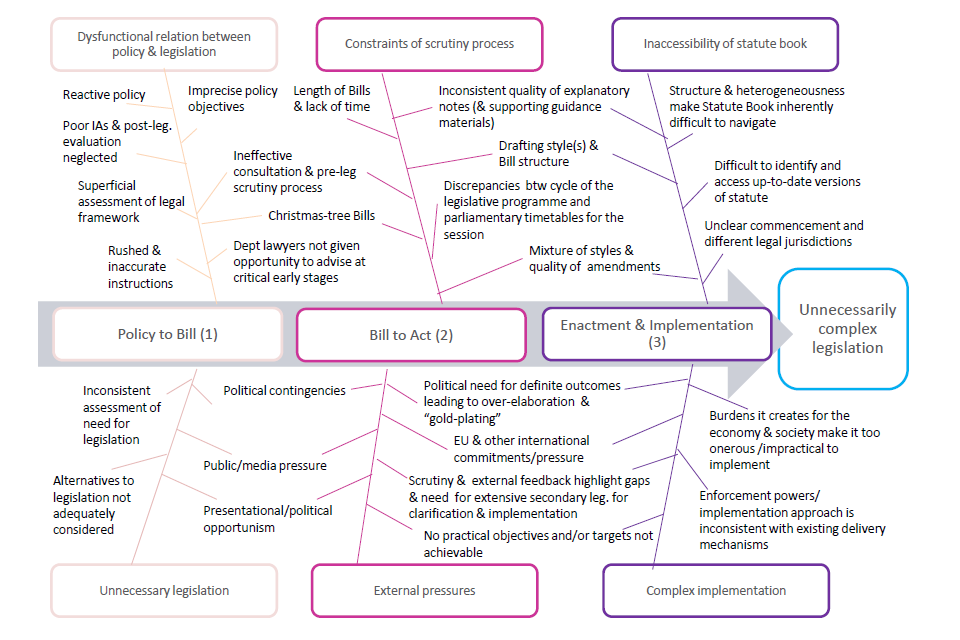

The following diagram summarises the most common criticisms that various audiences expressed about legislation during the course of this review.

A chart mapping the causes of unnecessarily complex legislation as it moves from policy to Bill, Act and finally enactment and implementation. Causes include the dysfunctional relation between policy and legislation; the constraints of the scrutiny proces

4.3 Upstream causes of unnecessary complexity in legislation

A number of public bodies play crucial roles in the various phases of the legislative cycle. They are, with their partners, addressing several of the issues identified in the diagram above. For example:

- Parliamentary Counsel is committed to continuous improvement in the quality of their drafting. The office works with colleagues in the legal profession to test new drafting techniques and to champion drafting best practice.

- Each House of Parliament, with government support, has promoted changes to modernise elements of parliamentary procedure.

- The National Archives are working with the Government Digital Service, other government departments and external stakeholders to improve the accessibility and usability of legislation.

- A number of cross-government initiatives to simplify and improve secondary legislation are already in progress (such as the Red Tape Challenge).

- The Office for Tax Simplification, established in 2010, is identifying areas where complexities in the tax system for both businesses and individual taxpayers can be reduced.

For this reason we decided to focus on causes of inadequate legislation that can emerge in the “Policy to Bill” phase and review the “upstream” causes of unnecessary complexity.

The role of the civil service is particularly crucial at this early stage, in preventing unnecessary complexity and mitigating potential technical defects of the law.

At this stage, each interaction between teams involved in the preparation of legislation can be a potential source of imprecision and inefficiencies: systemic short-circuits, procedural broken links and external contingency can add unnecessary complexity and generate unexpected or negative outcomes, difficult to rectify by means of amendments.

The legislative project changes substantially after each interaction and is the product of sensitive negotiations and compromises between stakeholders with conflicting objectives.

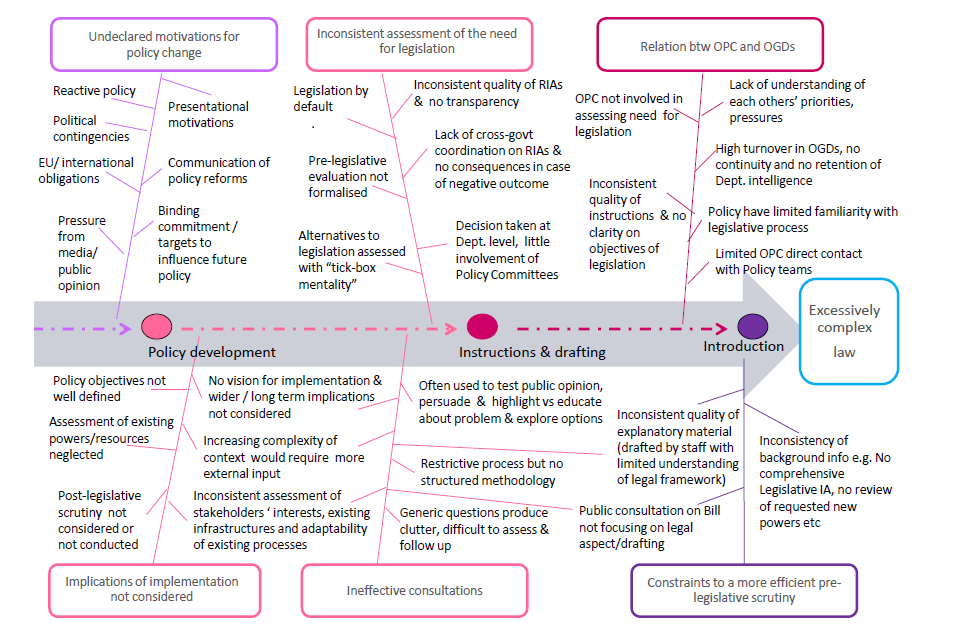

The following diagram summarises potential issues that may emerge in the Policy to Bill phase and can cause unnecessary complexity in Bills introduced to Parliament.

A chart showing causes of excessively complex legislation between policy and Bill stages. These include undeclared motivations for policy change; inconsistent assessment of the need for legislation and the relationship between Office of the Parliamentary

The review identified six aspects of the legislative process which are regarded as particularly significant for the effect that they have on the law. For each aspect there are potentially problematic elements that can generate unnecessary complexity in legislation.

4.4 Assessment of the need for legislation

Laws provide solutions to policy challenges, and they give effect to political vision. So effective legislation is linked to clear, coherent policy objectives.

During the policy development process things can happen that can generate unnecessarily complex legislation. Legislation is often regarded as the only option that will guarantee certainty of results and deliver direct and prompt outcomes. So alternatives to legislation may not be given serious consideration, or may be presented in a non-specific and unappealing way. Processes and standards for the assessment of proposals are not formalized. There is no agreed method for assessing the need for legislation. The type of data, the evidence collected and the methodology for modelling potential outcomes can be used inconsistently across departments.

4.5 Policy development and formulation of objectives

Policy-making and legislation happen in a political context, and are influenced by events and unforeseen circumstances. That is an inescapable feature of a democracy. One result is that legislation may be introduced for demonstrative or declaratory purposes, perhaps with the aim of signaling Parliament’s attachment to certain ideals or principles, rather than of achieving specific legal effects.

Policy making that responds urgently to external pressures may produce legislation which generates clear short term outcomes but which may not be as effective in achieving longer term objectives.

Another risk that needs to be managed when legislation is promoted at speed is that of missing opportunities to use existing legislation, leading to potential duplication or inconsistencies in the statute book. Moreover, legal barriers to implementation may become apparent only at a later stage, potentially jeopardising outcomes.

The increasing complexity of the social, economic and technological context in which policy-makers operate, suggests that policy development would often benefit from external input. This is one of the thoughts behind open policy-making, which itself is part of civil service reform plan. Digital channels make open policy-making easier and more effective.

The limitations and other characteristics of existing implementation infrastructures must form part of legislative planning. If that does not happen, legislation will generate disproportionate burdens, or may be too onerous or impractical to implement without major adjustments.

4.6 From policy to draft

Policy teams do not always have a profound understanding of the intricacies of the legislative process and are not necessarily familiar with parliamentary procedure. An insufficient understanding of the implications of legislation and the legislative process can sometimes limit the effectiveness of policy.

This is especially problematic when legislation is recommended without a preliminary assessment of the legal context. In those cases there could be the risk that a legislative proposal has already been developed by the time departmental lawyers are consulted.

If consulted early in the process, departmental lawyers and Parliamentary Counsel can help to identify potential duplication or inconsistency in the law and add weight to the preliminary assessment process. Legal expertise and knowledge of the statute book at this crucial stage may prevent legal pitfalls that could manifest themselves only during parliamentary scrutiny or sometimes after enactment.

The legislation secretariat within the Cabinet Office is working with Parliamentary Counsel to promote learning within departments about legislation and the legislative process.

Drafters tend to work mainly with bill teams and departmental lawyers. They only occasionally deal directly with policy officials and Ministers. This means that, at the earlier stages in the process, drafters tend not to work with departmental lawyers on advice to Ministers on how to leverage existing legislation nor can they alert the department to common traps and gaps in their legislative plan. An attenuated chain of communication between ministers, policy officials, lawyers and drafters also brings the risk of concepts being lost in translation or of accumulated complexity.

In short, Parliamentary Counsel and departmental teams face very different challenges, and they may not always fully appreciate each other’s priorities and pressures. In order to avoid instructing and drafting processes that generate burden and confusion, drafters and departments should continue to improve their understanding of each other’s roles and responsibilities.

4.7 Consultations and pre-legislative scrutiny

When external expertise is not properly harnessed there is a risk that gaps in the implementation plan may be missed or, when identified, may not be fully addressed. The long term effects of provisions may not be fully taken into consideration and stakeholders’ interests may be overlooked or assessed in an inconsistent way.

So consultation and engagement are important. But traditional consultation exercises can feel burdensome and unrewarding; and generic questions asked in a consultation may generate cluttered feedback that is difficult to analyse and to integrate into the policy or the draft bill.

In an increasingly complicated policy-making context, consultations that are not predominantly reactive often work better than the traditional model.

The two pilot Public Reading Stages conducted on the Cabinet Office website (for the Protection of Freedoms Bill in 2011 and the Small Charitable Donations Bill in 2012) and the online consultation conducted by the Department of Health on the draft Care and Support Bill demonstrate that a more participatory approach can help to improve the quality of legislation. Levels of participation and the diversity of feedback received varies substantially, indicating that approaches to consultation should be carefully tailored to the Bill. Government will consider a more targeted approach (as announced by the Leader of the House of Commons on 17 January 2013), where the type and scale of engagement is proportional to the potential impact of the proposal. This should produce more meaningful contributions to the pre-legislative scrutiny process ultimately improving the quality of the bill.

4.8 Explanatory notes and other supporting materials and guidance

Recurrently, when commenting on the excessive complexity of legislation, critics refer to the poor quality of explanatory notes, often regarded as unhelpful and occasionally misleading. Explanatory notes could be a very valuable asset for those interested in understanding the objectives, purpose and main effects of the bill. However, explanatory notes can frequently be mere summaries of the bill itself or revised versions of relevant policy papers.

The current template for explanatory notes ensures a consistent format, but the quality itself is variable. It may that a more flexible and innovative approach would be more helpful to readers within and beyond Parliament.

4.9 Negative perception of legislation

The architecture and heterogeneity of the statute book can make legislation difficult. Users perceive legislation as more complex and burdensome that it actually is because of the barriers to accessing and using it. Navigation between pieces of legislation is often a problem.

Users also appear to find it difficult to find reliable explanatory information and relevant guidance.

5. Conclusions and a vision for good law

5.1 Mitigating causes of complex legislation

In the course of this review it appeared evident that while users would like legislation that is simple, accessible, easy to comply with and not unnecessarily burdensome, at present those are not the features of modern legislation.

Some of the reasons for legislation falling short of what users hope for are inescapable. But there are other factors which ought to be within reach of government, Parliament, publishers and others – either acting in their own sphere of influence or in partnership.

For that to happen, there needs to be a shared ownership of, and pride in, our legislation. And pieces of legislation need to be regarded not just as documents in their own right, but as parts of a larger mosaic of legislation. It is the aggregate to which the user will have access to.

There also needs to be a stronger incentive on all involved in the process to avoid generating excessively complex law, or to act positively to promote accessibility, ease of navigation, and simplification.

The responsibility for improving outcomes sits in many places. Findings solutions requires a number of partners – in Government, in Parliament and beyond – to challenge their current approach to making and promoting legislation. A more collaborative approach, combined with simplified internal procedures, could facilitate the work of all those involved in the preparation of legislation, ultimately mitigating the manifestations (and causes) of complex laws.

The principles of collaboration and openness that form part of civil service reform could be applied to the preparation of legislation, as could the Government’s emphasis on simplification and transparency. Laws are not abstract sets of instructions and during their preparation the practicalities of how they will be promulgated, used and implemented should be carefully considered.

There may well be process changes which would help improve legislation – and a number of changes already under way have been mentioned in this report. But reaching a consensus around the principles of good law, and a sense of shared responsibility to promote it, could be more effective in improving the quality of statute law than stricter procedures and more prescriptive templates.

5.2 Good law

The Office of Parliamentary Counsel are launching a good law initiative. We are asking our partners and colleagues to agree that statutory law should be necessary, effective, clear, accessible and coherent.

As drafters, we play an important part in reaching that goal. We are always looking for better ways to write laws, and we would like to see more feedback from readers and users on what we do. But there are many other players, both in the preparation of legislation and involved more “upstream” in the policy process.

So we aim to:

- build a shared understanding of the importance of good law;

- ensure that legislation is as accessible as possible, and consider what more can be done to improve readability;

- reduce the causes and perception of unnecessary complexity;

- talk to the judges who authoritatively interpret the law and to the universities which teach it, to avoid confusion and facilitate interpretation.

In the UK we have one of the most sophisticated and capable platforms for managing legislation in the world (legislation.gov.uk). We have skilled drafters and a professional civil service committed to reform and innovation. We would like good law to be an integral part of the new approach to government where openness, collaboration and efficiency define the way Whitehall works with its partners and serves citizens.

6. Literature reviewed

A Mathematical Approach to the Study of the United States Code, Michael Bommarito and Daniel Martin Katz, 2010 A View on Legislation, Parliamentary Papers II, 1991

Assessing Legislation – a Manual for Legislators, Ann Seidman et alt.

Better Regulation in Europe: an assessment of Regulatory Capacity in 15 Member States, OECD, 2009

Burdened by Brussels or the UK? Improving Implementation of EU Directives, Report for the Foreign Policy Center, Sarah Shaefer and Edward Young, 2006

Business Perceptions Survey 2012, Prepared for NAO/LBRO/BRE by IFF Research, June 2012

Comparative Study on the Transposition of EC law in the member states, European Parliament, July 2007

Cutting Red Tape: National Strategies for Administrative Simplification, OECD, 2006

Draftsman’s Contract, OPC archives

Estimating the cost of legislation, Prof. St John Bates in: Evaluation of legislation: Proceedings of the Council of Europe’s legal co-operation and assistance activities, (2001), Strasbourg

Ex-Ante Evaluation and Alternatives to Legislation: Going Dutch?, Statute Law Review, Volume 32, Number 3, 2011

Explaining Yourself, Statute Law Review, Volume 31, Number 3, 2010

From Red Tape to Smart Tape, OECD, 2003

High Quality legislation – (How) Can drafters facilitate it?, Ross Carter, The Loophole, November 2011

How Much Legislation Comes from Europe, Vaughne Miller, 2010

How much legislation comes from Europe? House of Commons Research Paper 10/62 13 October 2010

Implementation of EU Legislation - Bellis Report, FCO, November 2003

Laying Down the Law, Daniel Greenberg, 2011

Legal Transplants in Legislation: Defusing the Trap, H. Xanthaki, 2008

Legislation.gov.uk and drafting techniques, a study by BunnyFoot for the National Archives and the Office of the Parliamentary Counsel. OPC archives, 2012

Legislative Section Heading: Drafting Techniques, Plain Language, and Redundancy, Statute Law Review, Volume 32, Number 3, 2011

Lost in Translation? Responding to the Challenges of European Law, NAO, May 2005

Lucida Law, Martin Cutts, Plain Language Commission, 1994

Making Better Law, Ruth Fox and Matt Korris, 2010

National Strategies for Administrative Simplification, OECD, 2006

Oral and written evidence, presented to the Political and Constitutional Reform Committee during the course of the ‘Ensuring standards in the quality of legislation’ inquiry from January 2012 to January 2013

Parliament and the Legislative Process, Select Committee on Constitution, Fourteenth Report, 2004

Parliament and the Legislative Process: the Government Response, Select Committee on Constitution, Sixth Report, 2005

Pre-Legislative Scrutiny in the 2008-09 and 2009-10 Sessions, Constitution Committee - Eighth Report

Public Bill Procedure, Select Committee on Procedure, 1985

Regulatory Quality in Europe, De Francesco, 2007

Report from Rippon Commission, 2003

Review of Government Legal Services, a report by Sir Robert Andrew KCB, 1988

Tax Law Rewrite, OPC archives

The Civil Servant as Legislator: Law Making in British Administration, Edward Page, 2003

The Drafting of Criminal Legislation: Need it be so impenetrable?, J.R. Spencer, Cambridge Law Journal, Number 67, 2008

The end of Legalese: the Game is Over, Robert Benson, 1985

The Preparation of Legislation, Report of a Committee Appointed by the Lord President of the Council, Sir David Renton et alt., 1975

The Role of Legislative Counsel: wordsmith or Counsel? David Hull, The Loophole, August 2008

The Text through Time, Statute Law Review, Volume 31, Number 3, 2010

Their Word is Law: Parliamentary Counsel and Creative Policy Analysis, Edward C. Page, 2009

What Regulatory Impact Assessment Tell Us?, F. De Francesco, 2008

When to Begin: a Study of New Zealand Commencement Clauses with Regard to those Used in the United Kingdom, Statute Law Review, Volume 31, Number 3, 2010

Why is there a Parliamentary Counsel Office, Geoffrey Bowman, Statute Law Review ( 2005) 26 (2): 69

Other resources include:

- Computational Legal Studies

- Participedia

- innovations.harvard.edu

- Legal Informatics Blog

- legislation.gov.uk

- Regulations.gov

- osale.ee

- edemocracia.camara.gov.br

The Office of the Parliamentary Counsel is grateful to colleagues from the following units and organisations, for providing informal advice and information:

- Better Regulation Executive

- Cabinet Office

- Clarity in Legislation Group

- Department for Business, Innovation and Skills

- Department for Transport

- Government Digital Service

- Home Office

- Law Commission

- Ministry of Justice

- National Audit Office

- Office for Tax Simplification

- Offices of the Parliamentary Business Managers

- Office of the Parliamentary Counsel, Australia

- Office of the Parliamentary Counsel, Scotland

- The Court of Appeal of England and Wales

- The House of Commons

- The House of Lords

- The National Archives

- The Queen’s Bench Division