Understanding decision making around changing the State Pension age: A review of international evidence

Published 30 March 2023

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the project team at the Department for Work and Pensions for their support throughout this study. In particular, we are grateful to Christopher Steer and Joshua Meakings for their guidance during the study.

We thank our two quality assurance reviewers at RAND Europe, Lucy Hocking and Silvia Galimberti, for their helpful suggestions, and Giovanni Maria Amodeo (RAND Europe), Professor Anne Balter (Tilburg University), Lucy Gilder (RAND Europe), Dr Lydia Lymperis (RAND Europe), Emmanuel Nielsen (RAND Europe), Dr Mafalda Pardal (RAND Europe), and Professor Anja De Waegenaere (Tilburg University) for their assistance and/or advice. This report represents the views of the authors.

The authors

Natalie Picken, RAND Europe

Merrilyn Groom, RAND Europe

Frederico Cardoso, RAND Europe

Dr Madeline Nightingale, RAND Europe

Joanna Hofman, RAND Europe

Professor David Blake, Pensions Institute, Bayes Business School, City University of London

Executive summary

This report presents findings from a review commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) to investigate how high-income Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries change State Pension age (SPa) and the variables considered when they changed the SPa. The objective of the study was to present available evidence on how other high-income OECD countries have approached the issue of determining the SPa, to generate knowledge and understanding that might be transferable to the UK. The SPa is an important element of a pension system’s viability and sustainability in each country, but financing pension expenditure in the longer term may require wider reforms, which are beyond the scope of this review.

This study was guided by the following research questions: (i) What factors affect the decision to change the SPa? (ii) How are changes made to the SPa internationally? (iii) What criteria are used (and how are they used) to change and determine the SPa? These research questions are addressed in sections 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3, respectively.

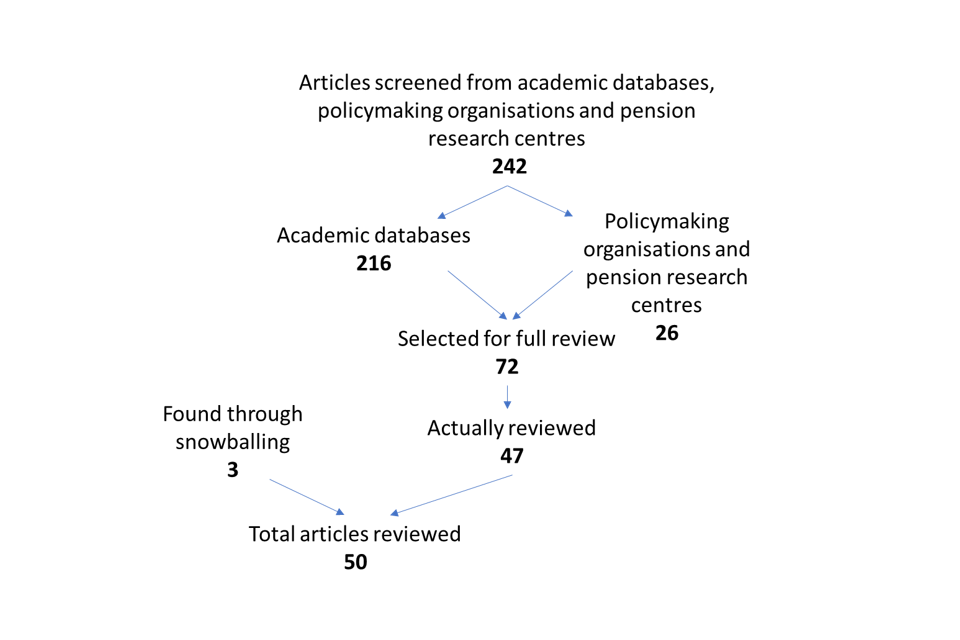

To answer these questions, we used a targeted literature review. The search identified 242 sources for screening. After screening and snowballing, we included 50 sources in a more detailed review. Appendix A details the methodology and inclusion and exclusion criteria applied in the search.

The key findings are:

- Throughout the OECD, SPa increases have been caused by gains in life expectancy and increases in the old-age dependency ratio, which risk increasing pension expenditure, bringing about intergenerational inequity and challenging fiscal sustainability.

- Increases in the SPa are frequently accompanied by other pension and wider policy reforms to increase the effective retirement age, but the ability to do this depends on political will.

- How effective changes to the SPa are depends greatly on the pension system and other reforms. Changes may be influenced by population heterogeneity – for example, the socio-economic differences in life expectancies.

- Changes to the SPa may come about through various decision-making processes, including government commissions, legislated measures and automatic adjustment mechanisms. However, in practice, these processes are not always sequential, and changes that do take place are often the outcome of various social, economic and political forces.

- Increasing the SPa is the most common legislative measure adopted to address pension viability and sustainability challenges. The SPa may be changed by setting a given SPa in legislation (for example, France); detailing a fixed schedule of review to the SPa in legislation (for example, Malta); setting up an automatic adjustment mechanism (AAM; for example, Italy, Portugal, Denmark); or using some combination of these (for example, Slovakia, the Netherlands). Legislation may be used to equalise the SPa for men and women.

- The way in which the SPa is changed may be informed by different policy targets – most frequently setting a particular ratio of adult life or a set number of years in retirement while receiving State Pension. However, legislation is sometimes used to alter or reverse previous increases and changes in the SPa.

- Changes in the SPa are often accompanied, or affected, by other pension reforms, including changes to early retirement policies, policies encouraging later retirement and the provision of an earlier SPa for those who started their careers earlier.

- A number of countries have recent experience of automatic or semi-automatic adjustment mechanisms (semi-AAMs), which are mechanisms whereby the SPa changes depending on changes in life expectancy. When deciding how an AAM will operate, there are 10 main areas where decisions can be made (including the age at which the link to life expectancy is set, the rate at which the SPa is changed compared with life expectancy changes, how often and when the mechanism is triggered, and when changes come into effect).

- These adjustment mechanisms are established and amended through legislation and can either be applied directly (AAM) or need prior approval for the changes to come into force (semi-AAM). There are several examples of recent reversals or changes to an AAM.[footnote 1]

- Life expectancy is the main variable used to determine changes in the SPa, with two main methods of calculating life expectancy: Period-based life expectancy (PLE) estimates life expectancy using recent mortality data (assuming mortality remains static). Cohort-based life expectancy (CLE) uses projected mortality rates to estimate life expectancy. All OECD countries that have adopted an AAM for changes to the SPa to date use PLE as the basis for their life expectancy calculations.

- Research demonstrates that PLE consistently underestimates life expectancy, and that, when used as the basis for a (semi-)AAM, using PLE leads to longer time spent in receipt of State Pension than expected and higher total pension expenditure.

- Other factors that may be relevant to consider when linking the SPa to life expectancy include healthy life expectancy, socio-economic disparities and the age at which adult life is considered to start.

1. Introduction

1.1. Policy context and background information: what is the State Pension age?

In this report, we use the term State Pension age (SPa) to mean the age at which people can draw upon a State Pension in different countries.[footnote 2]

Different OECD countries stipulate various ages at which people can receive their State Pension. Across OECD countries, the age at which an individual was eligible for retirement benefits without penalty in 2020 tended to sit between 62 years old (Costa Rica, Greece, Italy, Korea, Luxembourg, Slovenia) and 67 years old (Iceland, Norway), as shown in Figure 1. However, in many countries, people may also retire at an earlier age and (in a subset of these countries) be able to receive some or all of their State Pension then.

Figure 1: Current normal retirement age by gender across OECD countries, for an individual retiring in 2020

| Country | Women | Additional years for men (if different) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iceland | 67 | 0 | 67 |

| Norway | 67 | 0 | 67 |

| Israel | 62 | 5 | 67 |

| Netherlands | 66.33 | 0 | 66.33 |

| Australia | 66 | 0 | 66 |

| Ireland | 66 | 0 | 66 |

| United Kingdom | 66 | 0 | 66 |

| United States | 66 | 0 | 66 |

| Germany | 65.67 | 0 | 65.67 |

| Denmark | 65.5 | 0 | 65.5 |

| Portugal | 65.33 | 0 | 65.33 |

| Belgium | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| Canada | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| Chile | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| Finland | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| Japan | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| Mexico | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| New Zealand | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| Spain | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| Sweden | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| Switzerland | 64 | 1 | 65 |

| Austria | 60 | 5 | 65 |

| Poland | 60 | 5 | 65 |

| France | 64.5 | 0 | 64.5 |

| Hungary | 62 | 2.5 | 64.5 |

| OECD | 63.45 | 0.78 | 64.23 |

| Lithuania | 63 | 1 | 64 |

| Estonia | 63.75 | 0 | 63.75 |

| Latvia | 63.75 | 0 | 63.75 |

| Czech Republic | 63.67 | 0 | 63.67 |

| Slovak Republic | 62.67 | 0.17 | 62.83 |

| Italy | 62 | 0 | 62 |

| Greece | 62 | 0 | 62 |

| Korea | 62 | 0 | 62 |

| Luxembourg | 62 | 0 | 62 |

| Slovenia | 62 | 0 | 62 |

| Colombia | 57 | 5 | 62 |

| Costa Rica | 59.92 | 2 | 61.92 |

| Turkey | 49 | 3 | 52 |

| Argentina | 60 | 5 | 65 |

| Brazil | 57 | 5 | 62 |

| Russian Federation | 56.5 | 5 | 61.5 |

| South Africa | 60 | 0 | 60 |

| China | 55 | 5 | 60 |

| India | 58 | 0 | 58 |

| Indonesia | 57 | 0 | 57 |

| Saudi Arabia | 47 | 0 | 47 |

| EU27 | 63.46 | 0.84 | 64.30 |

| Bulgaria | 61.5 | 2.75 | 64.25 |

| Croatia | 62.5 | 2.5 | 65 |

| Cyprus | 65 | 0 | 65 |

| Malta | 63 | 0 | 63 |

| Romania | 61.25 | 3.75 | 65 |

Source: OECD (2021a). Permanent location of this file: https://stat.link/3vszen. For an individual retiring after an uninterrupted career from age 22.

Looking ahead – and based on current legislation – the OECD projects that the age at which State Pensions can be received will rise. Those joining the labour market at the age of 22 in 2020, the OECD estimates, would not be eligible for a State Pension until 2064, when the normal retirement age for men is estimated to be 66.1 years, and for women, 65.5 years, across the OECD.[footnote 3]

As in other OECD countries, in the UK, the SPa has shifted over time (see Table 1 for recent and planned changes). This has most recently been caused by efforts to equalise the SPa for men and women and to increase the SPa gradually for both genders.

Table 1: Recent changes in State Pension age in the United Kingdom

| Gender | Date of birth | State Pension age |

|---|---|---|

| Women | Before 6 April 1950 | 60 |

| Women | Between 6 April 1950 and 5 December 1953 | Between 60 and 65 (incremental increase depending on month of birth) |

| Men | Before 6 December 1953 | 65 |

| Men and women | Between 6 December 1953 and 5 October 1954 | Between 65 and 66 (incremental increase depending on month of birth) |

| Men and women | Between 6 October 1954 and 5 April 1960 | 66 |

| Men and women | Between 6 April 1960 and 5 March 1961 | Between 66 and 67 (incremental increase depending on month of birth) |

| Men and women | Between 6 March 1961 and 5 April 1977 | 67 |

| Men and women | Between 6 April 1977 and 5 April 1978 | Between 67 and 68 (incremental increase depending on month of birth) |

| Men and women | After 6 April 1978 | 68 |

Sources: DWP (2014a, 2014b).

The Pensions Act 2014 stipulates that the UK government must periodically review whether the SPa is appropriate, taking into consideration life expectancy and other specified factors, and that it must produce a report on this at six-year intervals. The aim of this policy is to ensure intergenerational fairness in sharing the costs of increased longevity, while also providing greater clarity around future changes in the SPa.[footnote 4] The first statutory review took place in 2017, and the second statutory review must be published by 7th May 2023.[footnote 5]

1.2. Research objectives and questions

The Department for Work and Pensions commissioned this report to inform the second statutory SPa review and to better understand the mechanisms and variables used to change the SPa internationally.

While overviews of national pension systems are available from OECD,[footnote 6] European Commission[footnote 7] or Mercer[footnote 8] publications or government websites, the mechanisms used to increase the SPa, as well as the specific variables and formulae or targets used, are rarely presented in a systematic fashion.

Therefore, this report responds to the following research questions:

- What factors affect changing the SPa?

- How are changes made to SPa internationally?

- What variables are used (and how are they used) to change and determine the SPa?

1.3. Method

To address the research questions above, the study uses a quick scoping review of the literature. This type of review was chosen because the scope is broad and open-ended, and the quality or robustness of the evidence was not an important consideration in the initial scoping. The search was limited to sources published between 2001 and 2021. The geographical scope of the review was limited to the OECD countries. The keyword search yielded 242 sources, of which we screened titles and abstracts, and from which we reviewed 47 sources. In addition, we identified 3 articles through snowballing (identifying articles of interest through those already reviewed). The total number of articles reviewed was 50.

We identified four countries of interest, in collaboration with the DWP: Denmark, France, Italy and Portugal. These were selected purposefully, given that they represented different approaches to determining the SPa – from direct legislation to AAM and semi-AAM. Where there were questions or gaps remaining in the literature for these countries, researchers with Danish, French, Italian and Portuguese language skills reviewed national government policy documents and legislation to add further information. This information is included throughout the report, with references to relevant documentation available in national languages.

We found that a small number of sources were particularly valuable for the topic at hand and frequently cited. These include academic articles by Ayuso and others[footnote 9] and Bravo and others,[footnote 10] as well as literature from the Economic Policy Committee and Social Protection Committee of the European Union[footnote 11] and the OECD ‘Pensions at a Glance 2021’.[footnote 12]

Further details about the methodology and inclusion and exclusion criteria are detailed in Appendix A.

1.4. Structure of report

The remainder of this report is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the main findings of the review, organised around the research questions. Section 2.1 introduces factors that lead to changes in the SPa. Section 2.2 investigates the mechanisms through which changes are made to the SPa internationally, illustrating these with examples from multiple countries. Section 2.3 discusses variables that are used to determine the SPa and the ways in which they are used.

Section 3 follows with important conclusions of the review and takeaway points for decision makers. Appendix A provides a methodological overview. Appendix B provides a list of sources identified through the quick scoping review.

2. Key findings

In this section, we outline findings to each of the three research questions. We draw out findings from the literature reviewed, illustrating points with examples from OECD countries where useful. We added to the information available from the literature review by including further detail (where available) from the legislation and national policy documents of four countries (Denmark, Portugal, France, Italy).

2.1. What factors affect changing State Pension age?

This section explores factors that affect decision making and changes to the SPa in the international context.

2.1.1. Rising life expectancy challenges the sustainability and intergenerational fairness of pension systems

Life expectancy is rising, meaning that there are more people in retirement than ever before, creating challenges for the sustainability of pension systems. Across the OECD, average life expectancy at age 65 is projected to increase by around 4 years for men and women (Table 2). Similarly, across the EU, the improvements in life expectancy (coupled with the ‘baby boomer’ generation reaching the SPa) resulted in a higher number of people in retirement than ever before (estimated at a quarter of the EU population in 2019).[footnote 13]

Table 2: The remaining average life expectancy of people aged 65 in 2015 to 2020 and in 2060 to 2065 across the OECD

| Gender | Remaining life expectancy for those aged 65 in 2015 to 2020 | Remaining life expectancy for those aged 65 in 2060 to 2065 |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 18.1 years | 22.5 years |

| Women | 21.3 years | 25.2 years |

Source: OECD (2021a). Note: This table shows the average number of additional years that a person aged 65 is expected to live.

The rising numbers of retired individuals, combined with lower fertility rates, means that the old-age dependency ratio (OADR) is increasing. The OADR looks at the pensionable population (aged above the SPa) divided by the working-age population.[footnote 14] When the OADR is high, a relatively large group of retired people must be supported by a relatively small group of people of working age. In 2021, the OADR across OECD countries was projected to increase by 23 percentage points between 2020 and 2050.[footnote 15] In the UK, the OADR is projected to increase from 280 persons of pensionable age per 1,000 persons of working age[footnote 16] in 2020 to 298 in mid-2030 and to 341 by mid-2045. This is despite legislated increases in the SPa to age 67 in 2028, and to age 68 between 2044 and 2046.[footnote 17]

While life expectancy continues to increase, the rate at which it is increasing has slowed.[footnote 18] The OECD estimates that this decline began in 2010: between the mid-1990s and 2010, average OECD life expectancy increased at a rate of 1.6 years per decade for men and 1.4 years per decade for women. Between 2010 and 2020, the increase was slower (1.3 years per decade for men and 1.1 years per decade for women).[footnote 19] Mortality data from 20 countries analysed in 2018 show that life expectancy at age 65 increased less in the previous six years than it had in the six years prior to that.[footnote 20] This slowdown has been attributed in part to high mortality rates from heart diseases and stroke, linked to such risk factors as smoking, high blood pressure and obesity.[footnote 21] Projections made by ONS in 2020 note declines for remaining CLE at age 65 for men and women, compared with estimates from previous years.[footnote 22]

It is not yet clear whether this is a temporary or permanent change in trends: some consider that life expectancy will be increasingly limited by health factors,[footnote 23] and others consider that there may be no natural barrier to life expectancy improvements.[footnote 24] The outbreak of COVID-19 has led to some observed changes in life expectancy in some countries. Between 2019 and 2020, life expectancy at the age of 65 declined in 18 of the 25 OECD countries for which there are data, by an average of 7.4 months (7.1 months for women and 7.7 months for men).[footnote 25]

Increases in life expectancy (and the OADR) can bring financial pressure to pension systems, which increases in the SPa could (partially) counteract. Demographic ageing increases the number of pension recipients and the OADR, directly increasing pension expenditure and reducing the tax base. In 2021, the OECD estimated that, without any further increases in the SPa, the increase in the OADR would increase OECD country State Pension expenditure by around 3.5 percentage points of GDP on average between 2019 and 2035.[footnote 26]

Increasing the SPa can have further indirect positive benefits on pension sustainability and net budget balance. Increasing the SPa is one means by which retirement can be delayed. From the literature, we can see that a delay in retirement produces positive effects on labour supply and employment, with older workers delaying their labour market exit.[footnote 27] This in turn can increase potential GDP, further improving the budget balance and debt-to-GDP ratio. Increasing the SPa can also prolong the period in which individuals remain net contributors to pension expenditure, by increasing the period over which they pay their contributions and cannot claim a State Pension.[footnote 28]

2.1.2. Increased life expectancy without corresponding changes in the SPa can adversely affect intergenerational fairness

Increasing the SPa, and linking this to life expectancy, is one way to support intergenerational fairness. Changes in the SPa can act both to maintain a consistent time spent in retirement and in receipt of State Pension across generations, and to reduce the fiscal burden of the State Pension system on future generations, by extending working lives. Linking the SPa to life expectancy may also ensure intergenerational equity in the time spent in receipt of a State Pension by fixing, in expectation, either a constant length or ratio of time spent above the SPa.[footnote 29]

However, SPa increases alone are unlikely to be sufficient to counteract wider inequities in the division of risks and resources between the generations.[footnote 30] This is particularly the case when population ageing is combined with economic downturns.[footnote 31] Increasing the effective retirement age (the average age of labour market exit, or the age at which people actually retire) by, for example, increasing the SPa, has been described as the only solution that maintains intergenerational equity regarding the time spent receiving State Pension.[footnote 32]

2.1.3. Various factors affect both how the SPa is raised and what effect the increase has on the SPa

Increases in the SPa do not always lead to proportional increases in the effective retirement age.[footnote 33] In many OECD countries, the effective retirement age remains lower than the SPa, despite several pension reforms tightening early retirement eligibility or establishing early retirement penalties (see section 2.2).[footnote 34]

The effective retirement age is governed by individual level factors, which are likely to be slower to change than the SPa.[footnote 35] These include:

- Health. Deteriorating health is considered a more important determinant of early retirement than economic or financial factors.[footnote 36]

- Social factors. Education, social class and gender can have a substantial effect on length of time spent in work and on motivations regarding early retirement or extending working lives.[footnote 37]

- Workplace factors. Levels of job satisfaction are important in determining effective retirement age.[footnote 38] There are factors that help facilitate longer working lives (e.g. flexible working conditions, support from management) and recognised barriers (e.g. workplace conflict, poor working conditions) to extending working lives.[footnote 39]

- Perceived health of the economy. Periods of low unemployment encourage the postponement of retirement.[footnote 40]

- Individual financial security and pension arrangements.[footnote 41]

Increasing the SPa in conjunction with other pension and policy reforms may be more effective in increasing effective retirement age.[footnote 42] Broader policy changes adopted by countries across the OECD are discussed in section 2.2. The gradual increases in early retirement age evident in recent years across the EU are in part attributable to pensions policy reform and in part to general societal changes and structural reforms, such as the rising economic activity of women, increases in educational attainment levels, and improvements in health.[footnote 43]

Heterogeneity among the population can mean that SPa changes affect groups differently – including men vs women. At the SPa, remaining life expectancy is not evenly distributed across the retiring population.[footnote 44] Life expectancy and pension wealth differ by socio-economic class, gender, type of work, income levels, labour market entry points, health and geography.[footnote 45] Having a universal SPa may therefore subsidise wealthier individuals over those from lower socio-economic groups.[footnote 46] The same holds true by region: both the remaining life expectancy and the rate of gains to life expectancy differ significantly by region.[footnote 47] While women tend to have longer life expectancy at the SPa (therefore standing to receive more in State Pension funding over their lifetime),[footnote 48] women also tend to reach the SPa with lower pension wealth due to gaps in pay, shorter career length and work intensity.[footnote 49] This gender pension gap was 29.4% across the EU in 2019, resulting in a 3.9 percentage point gender gap in the poverty rate risk for retired individuals.[footnote 50] As a result, women are more likely to take on employment while receiving their pension than men.[footnote 51]

Changes to the SPa do not occur in isolation; their effect depends on the current pension system and other reforms that might be concurrently implemented. Pension systems can vary in terms of their funding (combining public and private), their nature (whether they are mandatory or voluntary),[footnote 52] and their intended purpose (whether they are intended to provide all income in retirement, referred to as the Bismarckian model, or are intended to be supplemented by additional contributions, referred to as the Beveridgean model).[footnote 53] However, within these parameters, all pension systems reflect and compound differences across countries that adopt them, with a wide variety of design features.[footnote 54]

External factors (such as an increase in immigration) may reduce the pressure on pensions by broadening the tax base and reducing the OADR.[footnote 55] This is particularly the case because immigrants tend to be, on average, younger than the domestic adult population.[footnote 56] However, the effect depends on the country: those with higher levels of immigration, permanent and consistent movement of immigration, and higher-skilled immigrants stand to benefit most.[footnote 57] For example, the estimated gains to projected immigration flows from 2015 onwards range from 14.3 percentage points of labour income taxes in Austria, to 1.7 percentage points in Poland.[footnote 58]

2.2. How are changes made to State Pension age internationally?

This section describes the ways by which changes to the SPa come into place. We explore various mechanisms and processes, which have been identified primarily by drawing on reviewed literature:[footnote 59]

- changes suggested by government commissions on pensions or welfare reforms

- changes stipulated in legislated measures

- changes calculated by AAMs and semi-AAMs

Each mechanism is described in more detail below and examples of changes in individual countries are provided where available. While these three processes can sometimes be sequential components of changing the SPa (starting with a government commission, followed by legislation that introduces an automatic, semi-automatic or discretionary adjustment mechanism) in practice, this does not necessarily follow this sequential logic.

2.2.1. Government commissions on pensions or welfare reforms may make recommendations for SPa and other pension reform

Pensions or welfare commissions can be influential in bringing about policy reforms, including those in the SPa. This was the case in Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland and Norway, as explored in Table 3.

These commissions often recommended increasing SPa, giving a notice period of around 7 to 8 years, and recommended increases were typically incremental, amounting to around 1 to 3 months per year. However, the issue of raising SPa was never considered in isolation by the commissions. Table 3 details other, but related, measures that were recommended by commissions on pensions or welfare reforms, including:

- restricting early retirement schemes (Germany, Denmark)

- introducing an automatic stabiliser[footnote 60] to reduce the amount of pension if the dependency ratio deteriorates (Germany, Norway)

- making the amount of pension received dependent on the timing of retirement, calculating pension benefits based on all working years, and indexing pensions to mean price and wage increases, not just wages (Norway)[footnote 61]

Attributing change to commissions is difficult, given the absence of counterfactual and compounding factors over the length of time before any changes materialise. Whether, or to what extent, the recommendations of these commissions on pensions and welfare reforms are adopted depends on a number of factors, and has been a subject of comparative research not repeated here.[footnote 62]

Table 3: Government commissions on pensions or welfare reforms: recommendations on State Pension age and other aspects of pension system

| Country | Scope of commission | Date of commission | Recommendations relating to the SPa | Recommendations made by commissions relating to other aspects of pension system |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | Welfare | 2003 to 2005 | Raise the age of eligibility for pensions from 65 to 68 (by one month each year from 2013 onwards) | - Abolish the early retirement scheme (increasing the pre-retirement age by 4 months each year from 2009 until 2028, when it will be abolished) - Introduce compulsory private pension savings paid by employers and employees - Increase pensions payments from 2010 until the compulsory private pension savings has an effect |

| Denmark | Pension | 2020 to 2022 | Reduce the rate at which the State Pension age will increase from 2040 onwards (see Box 7) | - Require people with no or limited pension contributions to contribute 3.3% of business income |

| Ireland [footnote 63] | Pensions | 2021 | Raise the State Pension age by 3 months each year (starting in 2028) reaching the age of 67 in 2031 and 68 in 2039 | - Continue to finance the pension on a pay-as-you-go basis - Ensure an annual exchequer contribution to the State Pension account of the Self-Invested Fund - Introduce an automatic enrolment retirement savings system to improve retirement income adequacy - Continue to benchmark and index State Pension payments - Establish an independent body to advise government on pension payments - Align retirement ages in employment contracts with SPa, by introducing legislation that allows but does not compel an employee to stay in employment until SPa |

| France [footnote 64] | Pensions | 2019-ongoing | Raise the SPa from 62, with various suggestions put forward in 2019 which would result in a SPa of between 63.1 and 64.3 years. See Box 1 for more information | Some of the possible scenarios for a 2025 reform include: - an increase in contributions - an under-indexation of pensions in payment - several ‘age-related’ measures aimed at shifting the average effective retirement age of insured persons - a postponement of the age of entitlement - an increase in the length of insurance period |

| Germany | Social security systems | 2002 to 2003 | Raise the age of eligibility for pensions from 65 to 67 in the period 2011 to 2035 (with 1 month increase each year) | - Increase the age limit for early retirement benefits by 2 years - Introduce an automatic stabilisation factor to reduce pensions if the OADR increases |

| Norway | Pensions (except the early retirement scheme) | 2001 to 2004 | - Encourage people to work until SPa - Have flexible retirement age between 62 and 70 years (the longer one works, the higher the pension) - Allow pensioners to combine work and pensions, i.e. work income should not result in a corresponding reduction in pensions payment |

- Introduce an automatic stabilisation factor to reduce amount of pension received if the OADR deteriorates - Make amount of pension dependent on the timing of the retirement - Calculate amount of pension on all working years (not 20 years of highest income) - Index pensions based on price and wage increases (not just wage increases) - Change the public sector occupational pension scheme, so it does not guarantee two thirds of final salary - Discuss the increasing trend of early retirement with the social partners |

Sources: Beskæftigelsesministeriet (2022); Conseil d’Orientation des Retraites (2019); An Coimisiún Pinsean (2021); Lindén (2012); OECD (2021a)

2.2.2. Legislated measures can bring about changes in the SPa – either directly or indirectly

National legislation covers a wide range of linked aspects of a pension system in each country, with SPa being one of them.[footnote 65] This section first examines how legislation is used to directly change and establish a SPa. It then provides a brief overview of other legislative changes linked to the SPa.

Increasing SPa was the most common legislative measure adopted to address pension sustainability challenges.[footnote 66] Sixteen OECD countries have passed legislation to increase the SPa,[footnote 67] with examples including Bulgaria, Finland, Slovakia and France (see Box 1).[footnote 68] How SPa was changed and increased could take a number of forms in legislation. An SPa may be directly stated in legislation. This could take the form of establishing a new minimum[footnote 69] or target[footnote 70] retirement age that is designed to be in place for the foreseeable future or is revisited each year. SPa changes may also be legislated by setting out fixed schedules of the SPa for a certain number of years, which may be informed by the requirement for a review or report to be published. Countries may also set out automatic or semi-AAMs, which are then used to determine SPa (see section 2.3).

There are various factors that may lead to the legislated increase of SPa (as explored in section 2.1). In addition, what the SPa is set as may be informed by various policy targets adopted by governments. These include:

- ensuring a single SPa between men and women (see below)

- establishing a constant expected period above SPa (e.g. the Netherlands, Denmark)[footnote 71]

- establishing a constant ratio of adult life (or total lifespan) spent above SPa (e.g. Portugal, Czechia[footnote 72]

- targeting a constant balance (ratio) between time spent in work (contributing) and above SPa (e.g. France, Italy, Czechia, Malta)[footnote 73]

- linking the eligibility age for pensions to the eligibility age for other benefits, such as public healthcare (e.g. the United States)[footnote 74]

- using a combination of targets that are prioritised in different ways. For example, in Czechia, the current policy directive is to ensure an SPa of 65 years for both genders by 2030. From 2030, however, policy will aim to ensure that 25% of life is spent in retirement while receiving State Pension (with monitoring of life expectancy every five years to ensure that this is the case)[footnote 75]

We did not find comprehensive information about how frequently SPa was changed in national legislation, except when countries used automated adjustment mechanisms (section 2.2.3). As discussed in section 1.1, changes in the SPa legislation are made following major shifts in socio-economic circumstances. For example, there was an increase in the number of pension reforms since 2010, following the global financial crisis.[footnote 76] However, according to preliminary work carried out by the OECD in their ‘Pensions at a Glance 2021’ report, the COVID-19 pandemic has not yet had a major effect on the pension system or brought about significant changes to the SPa.[footnote 77]

Box 1: Reforms to State Pension age in France

France is one of the countries that sets out the SPa directly in legislation. In 2019, the pension system in the private sector in France had two public mandatory tiers: a defined benefit public pension and occupational schemes based on a points system.

Qualifying conditions for a full pension:

- a minimum contributory period of 41.5 years and meeting the minimum legal pension age (e.g. 62 years in 2019 for people born in 1957) or

- a minimum age of 67 (e.g. for people born in 1957)

Based on the 2014 reform, the minimum contributory period will increase from 41.25 years (165 quarters) for people born in 1954 to 43 years (172 quarters) for people born in 1973 or later.

There is limited public information about how the SPa is calculated and its relationship to life expectancy. While the factual information about the SPa (and plans for reforms) is in the public domain, the reasons for setting specific qualifying conditions for different SPa are not transparent, and we understand that these vary among the 42 pension schemes in play (11 of which do not connect the SPa to life expectancy).

Unlike in automatic mechanisms (see section 2.2.3), the basic parameters of changing SPa (e.g. the link to life expectancy, the rate or frequency of changes) are not clear from public information and, in any event, are subject to future legislation.

France allows early retirement (before SPa).

- Main public pension scheme: allowed for people at age 60 with a full contributory record and who started to work before age 20

- Occupational pension: allowed but subject to reductions related to either age of retirement or years of contributions or both

France also encourages later retirement (after SPa).

- Main public pension scheme: for each additional quarter after reaching State Pension age that is spent in employment, the individual’s contribution is increased by 1.25% (5% per year)

- The occupational scheme covering private and agricultural sector employees: workers continue to accumulate points during the period of delayed retirement; work income and pension benefit can be received together without restrictions if people have full-rate pensions (otherwise there are some restrictions)

There are ongoing changes to the French pension system and the SPa.

- France planned to adopt a universal points system covering workers from both the public and private sectors, including the self-employed. The proposal aimed to combine the 42 mandatory pension schemes. The reform was suspended in 2020 with the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

- There have been various proposals to increase the SPa from 62. As explored in Table 3, various scenarios have been put forward by the Conseil d’Orientation des Retraites. A 2019 recommendation included increasing the SPa, considering different scenarios depending on different types of accounting regimes possible. This resulted in suggestions with a 1 to 1.8% variation in contribution and with an overall SPa between 63.1 years and 64.3 years.[footnote 78]

Sources: OECD (2019b); OECD (2021a); Conseil d’Orientation des Retraites (2019)

Legislation is also frequently used to reverse or alter previous increases or changes in the SPa. There are multiple examples of legislative measures that set to change or reverse previous changes. Examples are set out in Table 4 and include:

- Croatia accelerated the convergence of SPa and early retirement ages for women to the standard regime by 2027, after which SPa was expected to rise to 67 by 2038. However, the increase to the SPa (and in the early retirement age) is expected to be cancelled.[footnote 79]

- In Czechia, the 2011 policy decision was that, once SPa reached 65 years, in 2030, the SPa would increase by 2 months per year indefinitely (resulting in a faster rate of SPa growth than elsewhere). However, in 2016, the SPa was capped at 65.[footnote 80]

- In Denmark, the commission examining pensions established by the government has recommended that changes be made to the AAM governing the SPa (see Box 7).

- In Ireland, there have been several changes in the direction of policy around SPa increases. While legislation from 2011 stated that the SPa would rise from 66 to 67 (in 2021) and then 68 (in 2028), this was deferred by the government in 2020.[footnote 81] However, in 2021, the Commission on Pensions recommended an increase in the SPa to 67 in 2031 and to 68 in 2039.[footnote 82] It is as yet uncertain whether and how this increase will be brought about in legislation, given that there is some opposition in parliament.[footnote 83]

- The previous decision to raise the SPa in Poland was cancelled in 2017.[footnote 84]

- As part of a pension reform agreement reached by the Dutch government and social partners (employer groups and labour unions), the Netherlands postponed the planned increase in the SPa for two years and then changed the way in which SPa was linked to life expectancy (see Box 8 for further information).[footnote 85]

- Slovakia adopted constitutional amendments to cap the SPa at 64 (for men and women without children) and to undo the automatic adjustments to the SPa to gains in life expectancy (see Box 11).[footnote 86] A year later, in 2021, the government planned to re‑establish a link between SPa and life expectancy.[footnote 87] The OECD attributes this shift to a lack of widespread political agreement on the initial policy.

Table 4: Reversal of changes to State Pension age legislation

| Reversal of changes to the SPa legislation | Countries |

|---|---|

| Reversing or delaying increases in the SPa | Croatia, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland |

| Removing or loosening the link between SPa and life expectancy | The Netherlands, Slovakia*, Denmark** |

Sources: Economic Policy Committee and Social Protection Committee (2020); Finnish Centre for Pensions (n.d.); OECD (2021a). Notes: *The link is expected to be re-established. **Proposed only.

There have been several legislative efforts throughout OECD and EU countries to equalise SPa between men and women.[footnote 88] Historically, women often had a lower State Pension age than men. Most recently, gender differences in the SPa have been phased out by Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Greece, Italy, Japan, Malta, Slovenia, Slovakia and the UK.[footnote 89] Other OECD countries have legislative plans or policies to phase out gender differences in the coming years, including Austria, Costa Rica, Croatia, Lithuania, Switzerland and Turkey.[footnote 90] Only a few countries in the OECD (Colombia, Romania, Hungary, Israel, Poland) plan to retain a gender difference in the SPa in the future.[footnote 91]

There remain some specific arrangements included in legislation relating to parents in a few countries. In Slovakia, Czechia, and Slovenia, SPa may be lowered if those retiring have children:

- In Slovakia, changes made in 2019 enabled the SPa of mothers to be reduced by 6 months for each child (up to three children). This right may be transferred to fathers if the mother is unable to benefit.[footnote 92]

- In Slovenia, women with 5+ children can have their SPa lowered by up to 4 years. Men with 5+ children can also retire up to 2 years earlier.[footnote 93]

- In Czechia, women who raised children have a lower SPa.[footnote 94]

- In Italy, reforms made in 2017 allowed women to retire at the age of 58 (or 59 if self-employed), after a 35-year career. While initially intended to expire in 2020, this policy was extended to the end of 2021.[footnote 95]

Legislation bringing about other pension reforms. Other legislative reforms may indirectly affect decisions made about the SPa and the extent and nature of changes made. In particular, legislative reforms around early retirement and encouraging longer working lives affect whether and how the SPa is changed.

Countries may restrict or widen access to early retirement. Some countries have phased out special pensions that grant preferential treatment to certain groups of the population (Austria, France, the Netherlands, Romania, Finland, Spain, Sweden).[footnote 96] In Spain, for example, the more generous conditions for partial retirement in the industrial sector are expected to end in 2022.[footnote 97] However, alongside these policies, other countries took measures to extend early retirement options in recent years. These include Denmark (see Box 2), Ireland, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands and Lithuania.[footnote 98] Other countries allow an earlier SPa for workers with long careers (as explored in Table 5 and Box 3).

Box 2: Expanding early retirement in Denmark and the Netherlands

In Denmark, from January 2022, people who have been employed for at least 42 years before the age of 61 are able to retire and receive a pension up to 3 years before the State Pension age, of 67, with a benefit reduction of 4.2% per year.

In the Netherlands, a new early retirement option was created for those working in ‘arduous occupations’. From 2021 to 2025, employers could allow employees in such positions to retire up to 3 years before the SPa with an early retirement benefit and without a tax penalty for the employer. Criteria to establish these occupations will depend on the individual sectors, and the scheme is employer financed.

Sources: OECD (2021a); Social Security Administration (2019)

Table 5: EU and OECD countries where people with long contributory periods are offered an earlier SPa

| Country | Years of contribution/work needed to ensure an earlier SPa than rest of population | Years difference in the SPa with a longer working life |

|---|---|---|

| Spain | 37 years and 3 months (38.5 years in 2027) | 1 year less (65 vs 66) |

| Italy[footnote 99] | 38 years | 5 years less (62 vs 67) |

| Greece | 40 years | 5 years less (62 vs 67) |

| Croatia | 41 years | 5 years less (60 vs 65) |

| Malta | 35 years | 2 years less (61 vs 63) |

| France | 41.5 years | 5 years and 7 months less (62 vs 66 and 7months) |

| Denmark (from January 2022) | 42 years before age 61 | 3 years less (64 vs 67) |

Note: In Belgium, Austria, Germany and Russia, it is possible to retire earlier than the SPa if one’s working life has been longer. Further information is not given. Sources: Ayuso and others (2021a); OECD (2021a); Finnish Centre for Pensions (n.d.).

Box 3: Lower pension ages for workers with long careers in Portugal

In Portugal, workers aged 60 or older and with at least 40 years of contributory periods can retire early, with the early retirement pension reduced by 0.5% for each month before the SPa (penalty) and multiplied by the sustainability factor (the ratio of life expectancy at 65 in 2000 over life expectancy at 54 the year before the old-age pension is accessible). If the contributory period is longer than 40 years, the SPa is reduced by 4 months for each additional year.

Source: OECD (2021a).

Policies may be enacted that aim to encourage later retirement at an age beyond the SPa. This includes introducing bonuses and penalties for retiring after and before the normal pension age, respectively (see Table 6 – and as in 18 EU countries, as mapped in 2018).[footnote 100] Other policies include:

- introducing flexible retirement pathways and generalising the right to work beyond the SPa and flexible retirement (as recommended by the 2021 pensions commission in Ireland – see Table 1)

- facilitating longer working lives and smoothing transition into retirement, through easing rules to combine work and pensions (e.g. Canada,[footnote 101] Czechia,[footnote 102]Greece,[footnote 103] Japan,[footnote 104] Romania,[footnote 105] Slovenia,[footnote 106] Spain,[footnote 107] UK[footnote 108])

- exempting workers claiming old-age pension from paying pension contributions (e.g. Hungary)[footnote 109]

- introducing a ‘target retirement age’ to nudge people to work longer to offset the effect of the life expectancy coefficient on replacement rates (e.g. Finland, Sweden; see Box 5).

Table 6: Penalties for early retirement and incentives for later retirement in EU countries

| Bonus for later retirement and penalty for early retirement | Bonus for later retirement only | Penalty for early retirement only |

|---|---|---|

| Austria, Bulgaria, Czechia, Croatia, Cyprus, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Lithuania, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain | Hungary, Malta | Greece, Latvia |

Source: Economic Policy Committee and Social Protection Committee (2020).

Box 4: How Hungary and Spain encourage later retirement

In Hungary, since 2020, there is an exemption for people over the SPa who combine work and claiming a pension from paying pension contributions: neither the worker nor the employer is required to pay pension contributions. The OECD considers that this provides a strong incentive for people to work later.

Ongoing legislative efforts in Spain seek to increase incentives for working later and to discourage early retirement. A legislative proposal would increase contribution rates for those working past the SPa to 4% (regardless of the length of the contribution period) and provide people working past the SPa without claiming a pension to receive 1 year’s bonus for deferring retirement, as a lump-sum payment (expected to be around 30% to 50% of yearly benefits). The proposal also changes the current penalties for early retirement. The proposal has been accepted by the government and social partners and is expected to be implemented by the end of 2023.

Source: OECD (2021a).

Box 5: Flexible and ‘target’ retirement age in Sweden

In Sweden, individuals are able to draw an earnings-related national pension from the age of 62 and a guaranteed pension benefit from the age of 54 but are entitled to stay in employment until they are 68 years old (the current mandatory retirement age, which is intended to increase to 69 from 2024).

In 2019, Sweden introduced the ‘target retirement age’ to nudge workers to delay their retirement, by indicating what the age to retire should be to compensate for the effect of the life expectancy coefficient on replacement rates. This has been set at the age of 67 and is effective from 2026.

Other changes to the SPa in Sweden include:

- Increasing the minimum SPa for public earnings-related pensions from 61 to 62 years and planning further increases to 64 in 2026

- Linking the SPa to life expectancy from 2026 (transferring two thirds of gains in life expectancy into time spent in retirement)

- Increasing the eligibility age to the basic pension from 65 to 67 years in 2027

Source: OECD (2021a).

Finally, there have been some developments to improve access to pension systems for people in types of work other than permanent, full-time employment. This has included granting legal access to previously excluded categories or making statutory access compulsory for the self-employed (e.g. Lithuania, Romania)[footnote 110] and harmonising and improving the ability to transfer entitlements between old-age schemes related to different categories of workers (e.g. France, Greece, Italy, Poland).[footnote 111]

2.2.3. Automatic adjustment mechanisms link the SPa to life expectancy

AAMs are predefined rules that automatically change set parameters, based on demographic, economic or financial indicators. One way in which an AAM can be used is to link the SPa to life expectancy.

The OECD recommends the use of AAMs because they are transparent. In the case of indexation to life expectancy, using AAMs can make it clearer how changes to the SPa are made. The OECD considers that AAMs are the best way to solve challenges of demographic changes caused by higher life expectancy because of their transparency, ability to react quickly to changes in life expectancy and generate smoother change, and because they allow more frequent reform of pensions without the need for political intervention.[footnote 112]

The OECD also notes, however, that for AAMs to achieve their objectives, it is important that AAMs be designed to endure over time and throughout shifts in political systems and to avoid the suspension or bypass of existing AAMs.[footnote 113] Suggestions on how to do so include:

- concentrating on small adjustments over large adjustments

- using separate measures to bring about bold discretionary changes

- building and ensuring broad political and popular support for the particular AAM[footnote 114]

- ensuring that AAMs are designed appropriately, using accurate and relevant projections[footnote 115]

- designing sufficient administrative capacity to manage updates[footnote 116]

Use of adjustment mechanisms to link the SPa to life expectancy

AAMs have been recently used to link the SPa to life expectancy in various ways in eight countries (Estonia, Finland, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark, Portugal, Slovakia) and are planned for use in Sweden from 2026.[footnote 117] There is considerable variation between different AAMs. From the literature, we identify 10 important variables in which AAMs can differ (see Table 7):

- Age at which the link to life expectancy is set: The age at which the link to life expectancy is calculated can vary. In most countries, this is set at 65 (which may be because 65 is either the current SPa or the target retirement age in most OECD countries).[footnote 118]

- Rate: The rate at which life expectancy increases translate to SPa increases can vary. If the rate is set as one-to-one (Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Italy), then all additional years of life expectancy will be added to the working life. If the rate is set at two thirds (Finland, the Netherlands, Portugal), then only 8 months of each additional year of life expectancy will be added to the working life. See Box 6 for more detail.

- Frequency of revisions: How frequently the AAM is set up to trigger changes in the SPa can vary. Changes may take place annually (Estonia, Finland, the Netherlands, Portugal); every few years (Italy, Greece); or every 5 years (Denmark).

- Notice period: The time between the AAM establishing a new SPa and the new SPa coming into practice may vary between countries. The shorter the period, the more ‘aligned’ the AAM is with changes in life expectancy. In Greece, the notice period is 1 year while Estonia, Italy and Portugal use 2 years for their notice period. Longer notice periods are found in the Netherlands (5 years) and Denmark (15 years).

- Minimum SPa increase: The AAM may stipulate the shortest amount of increase in the SPa that the AAM can trigger. In most countries, an increase in the SPa period is set at 1 month (Estonia, Finland, Italy, Portugal), although the Netherlands sets 3 months and Denmark sets 6 months. A few countries do not set out a minimum increase (Greece, Slovakia). AAMs that have no minimum or only a small minimum may be considered the most sensitive to life expectancy increases, while those that set larger minimums may do more to smooth the increases in SPa for those experiencing them.

- Maximum SPa increase: The AAM may stipulate the largest amount of increase in the SPa that can be triggered at each point. The maximum increase is set as 2 months in Finland; 3 months in Estonia, Italy and the Netherlands; and 1 year in Denmark. There is no maximum increase set in Greece, Portugal, and Slovakia.[footnote 119] AAMs that have no maximums may be considered the most sensitive to life expectancy increases, while those that do set maximums may do more to smooth the increases in SPa for those experiencing them.

- Direction of change: In some countries, policy stipulates that the AAM can only change the SPa when there is an increase in life expectancy (Denmark, Italy, the Netherlands). In other countries, the AAM may be used to decrease the SPa, should life expectancy decline (Estonia, Finland, Greece, Portugal).

- Time period of data used to consider life expectancy: Different countries use data from different ranges. For example, Italy uses an average of preceding 4 years (Denmark uses an average of preceding 2 years).

- Life expectancy type: Legislation may stipulate the type of life expectancy estimates that it is based upon, that is, whether PLE or CLE. See section 2.3 for more information.

- Level of automation: The AAM may be established in legislation to come into place automatically (‘fully automatic’) or may require parliamentary or other approval before entering into force (‘semi-automatic’). See below for more information.

Box 6: Rate of linking State Pension age with life expectancy

There are two main ways in which AAMs have linked the SPa to life expectancy:

-

Two thirds link: Under this linkage, two thirds of longevity gains are passed into the SPa increases (Finland, the Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden). This keeps the proportion of adult life that people can expect to spend over the SPa roughly the same across cohorts. According to the OECD, this helps to ensure a stable pension rate across generations if fertility rates are equal to a population replacement rate of around 2.1. Lower fertility rates may require a faster link.

-

One-to-one link: Under this linkage, all longevity gains are passed into SPa increases (Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Italy). This leads to a steady decline in the length of the period spent above the SPa relative to the period spent working.

These different ways of linking the SPa to life expectancy have different effects on the rate of SPa change. As seen in Figure 2, when a one-to-one link is used, the SPa rises more sharply and to a greater extent than when a two thirds link is used. The OECD ‘Pensions at a Glance 2021’ report flags that one-to-one links may not be politically sustainable, given the steady reduction of the share of life spent in retirement compared with the share of life spent in work, and the report cites recent changes in policy from the Netherlands and Slovakia.

Figure 2: Change in normal retirement age for those retiring between 2005 and 2050 in countries now linking the State Pension age to life expectancy

One-to-one link:

| Country | 2005 | 2021 | 2035 | 2050 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark (2030) | 65 | 66.5 | 69 | 71 |

| Estonia (2027) | 63 | 64.25 | 66.6 | 68.8 |

| Greece (2021) | 58 | 62 | 63.5 | 64.83 |

| Italy (2013) | 57 | 67 | 68.25 | 69.5 |

Two-thirds link:

| Country | 2005 | 2021 | 2035 | 2050 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finland (2030) | 65 | 65 | 65.58 | 66.92 |

| Netherlands (2026) | 65 | 66.33 | 67.5 | 68.33 |

| Portugal (2015) | 65 | 66.42 | 67.5 | 68.37 |

The year in parentheses is the year from which the link started or will start to apply. The numbers shown also include discretionary increases before the link kicks in. For Denmark, the SPa projected for 2050 is slightly lower than in the most recent projections from the national statistics institute, according to which it would be 71.5 years. The data for Estonia in 2005 show the normal retirement age for men; the SPa for women was at 59 years during the first half of 2005 and at 59 years and 6 months in the second half of that year. The data for Finland show the age from which a person has access both to the earnings-related and the targeted pension scheme. In the earnings-related scheme, the normal retirement age was 63 years in 2005 and is 63 years and 9 months in 2021.

Source: OECD (2021a).

Table 7: Characteristics of AAMs that index State Pension age in eight OECD countries

| Country | Estonia | Finland | Greece | Italy | The Netherlands (from 2019) | Portugal | Slovakia (2012 to 2019) | Denmark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year legislated | Not available | 2015 | 2010 | 2010 | 2012 (1 to 1 link), 2026 (2/3 link) | 2013 | 2012 to 2019 | 2006 |

| Age at which link to life expectancy is set | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 63 | 60 |

| Rate at which life expectancy increases translate | 1 to 1 | 2/3 | 1 to 1 | 1 to 1 | 2/3* | 2/3** | 1 to 1 | 1 to 1 |

| Frequency of revision | 1 year | 1 year | 3 years | 2 years | 1 year | 1 year | Not given | 5 years |

| Notice period | 2 years | 3 years | Max. 1 year | 2 years | 5 years | 2 years | Not given | 15 years |

| Minimum SPa increase possible | 1 month | 1 month | No | 1 month | 3 months | 1 month | No | 6 months |

| Maximum SPa increase possible | 3 months | 2 months | No | 3 to 5 months | 3 months | No | No | 1 year |

| Direction of change | Two-way | Two-way | Two-way | One-way | One-way | Two-way | Not given | One-way |

| Time period of data used | Not given | Not given | Not given | Average of preceding 4 years | 5 years in advance | Average of preceding 3 years | From 4 to 8 years previously | Average of preceding 2 years |

| Type of life expectancy calculation | PLE | PLE | PLE | PLE | PLE | PLE | PLE | PLE |

| Level of automation | Automatic | Automatic | Automatic | Automatic | Automatic | Automatic | Automatic | Semi-automatic |

Sources: Ayuso and others (2021a); Economic Policy Committee and Social Protection Committee (2020); OECD (2019a, 2021a); Ministero dell’Economia e delle Finanze (2017); Camera dei Deputati, Servizio Studi, XVIII Legislatura (2022); Retsinformation (2011). Notes: * The Netherlands had a previous AAM in place that had a 1 to 1 rate. ** For someone with more than 40 years of contributions, the State Pension age increases by only half of life expectancy gains.

An AAM may be overseen and amended through legislation or through being set up as semi-automatic adjustment mechanism. As explored in Table 7, Denmark has a semi-automatic mechanism in place, meaning that the AAM requires external approval to be put into action. In Denmark, parliamentary approval is required to apply the link and change the SPa in line with the AAM. This allows the Danish parliament to exercise additional control and make any changes subject to political approval. Perhaps as a result of these conditions, we found that the Danish AAM has several characteristics that mean the link with life expectancy is moderated: it is less frequently updated (every 5 years); slower to take effect (with a 15-year notice period); and has a higher minimum and maximum increase that is possible (6 months to 1 year). These features are, however, to some extent offset by the earlier age for which the link to life expectancy is based (60 years, as opposed to 65 years in other countries) and the fact that the rate of matching is one-to-one (all extra years of life expectancy translate to extra years in work). However (as explored in Box 7), there are current proposals that would change both features. In Denmark, the period that people can expect to live in retirement while receiving State Pension, on average, is fixed at 14.5 years.[footnote 120]

While other AAMs are, in practice, fully automatic and do not require political intervention to operate, we note that there have been several recent examples of changes made to AAMs (including in the Netherlands and Slovakia, as explored in section 2.2).

Box 7: Proposed changes to the automatic adjustment mechanism used in Denmark

In 2020, an independent commission was set up to examine the State Pension system in Denmark and whether any changes were needed. Findings from the commission released in May 2022 recommended a few changes to the way in which the SPa is calculated, including:

- Age at which link to life expectancy will be set: the commission recommended that remaining life expectancy at the SPa is used (instead of the life expectancy at age 60)

- Rate: the commission recommended that 80% of the increase in life expectancy is spent in work and 20% is spent in retirement (instead of 100% of increase being spent in work, or one-to-one matching)

- Direction of change: the commission recommended that the AAM allows the SPa to decrease as well as increase, by at least six months and by no more than 1 year

The commission proposed no changes to the semi-automatic processes, the maximum and minimum increases, the frequency of regulation, and the notice period.

The rationale for the changes, cited by the commission, is that life expectancy has increased more than it had been expected to do at the time the initial AAM was put into place, and the corresponding increase in the SPa means that future generations will spend a greater proportion of their life in work than previous generations.

The commission’s recommendations will now be considered by the government and parliament, who will decide whether and how to adopt the recommendations. If adopted as proposed, changes will come into force in 2040 and into effect in 2045.

Source: Beskæftigelsesministeriet (2022).

Other automatic indexation mechanisms are used to determine other aspects of the pension system, and these interact with indexation to the SPa.

Many countries use AAMs to determine other aspects of pension policy, including the amount of pension benefit received. In various countries within the OECD, this may be determined through an AAM that links life expectancy, the size of the working population, or various financial factors to the amount of benefit that is paid.

Almost two thirds of OECD countries have at least one AAM, while 10 countries have multiple AAMs in place (Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Sweden). For example, Sweden has multiple AAMs governing their pensions system, including benefits that are adjusted to life expectancy, and a balancing mechanism that considers both the contribution assets and the value of the reserve fund.[footnote 121] Further information on other AAMs may be found in OECD (2021a).

2.3. What variables are used (and how are they used) to change and determine the State Pension age?

This section sets out how variables are used to change and determine the SPa. As explored in section 2.2, the main variable used to determine the SPa is life expectancy, with AAM linking the two.

Therefore, this section concentrates on the way in which life expectancy is used when determining the SPa (including considerations around how it is calculated and how it interacts with other variables). In this section, we draw particularly upon a few sources that concentrated on variations in life expectancy calculation (including Ayuso and others 2021a, 2021b; Bravo and others 2021a, 2021b).

2.3.1. Formulae can represent how the SPa is calculated in countries with AAM

Eight OECD countries have recent experience of using automatic or semi-automatic indexation mechanisms that link the SPa to life expectancy.[footnote 122] Table 7 outlines the basic characteristics of these mechanisms and how they feature in the eight countries. This section looks in more detail at the formulae used to calculate the SPa in four countries.[footnote 123]

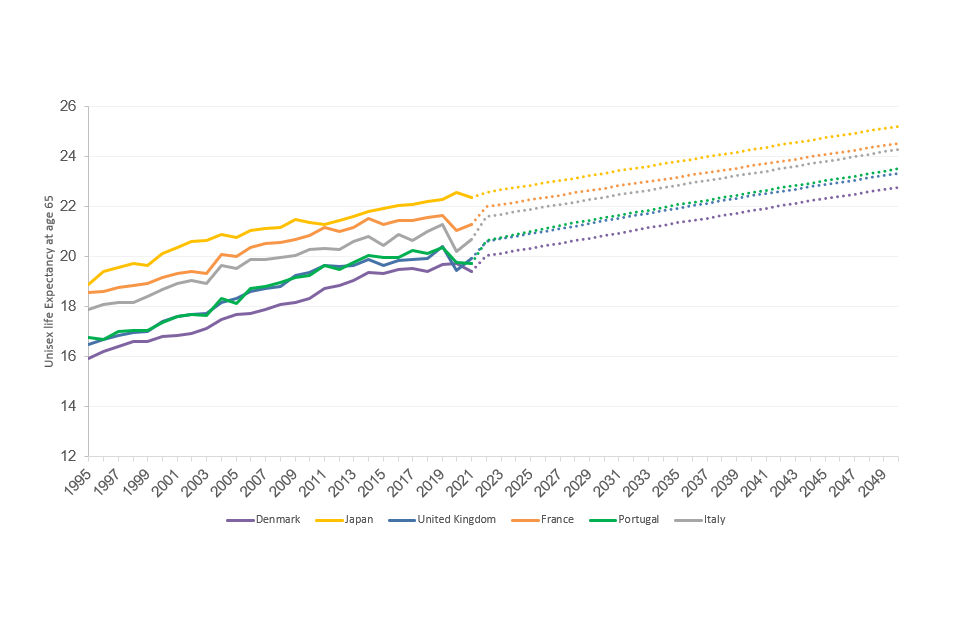

Across all countries explored here, life expectancy at age 65 (as calculated by the Human Mortality Database) is increasing, albeit from different starting points (as shown in Figure 3).

Figure 3: Projected increases in life expectancy in Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, Portugal and United Kingdom

Line chart showing the projected increases in life expectancy in Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, Portugal and the United Kingdom until 2050.

Source: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022). World Population Prospects 2022, Online Edition.[footnote 124]

Box 8: How State Pension age was calculated in the Netherlands until June 2019

Until June 2019, the SPa was automatically indexed to life expectancy in the Netherlands in a way that can be represented by the following formula:

V = (L – 18.26) – (P – 65)

Within this formula:

- V = increase of eligibility age in years

- L = the remaining unisex PLE at the age of 65 as projected by the national statistics institute (Statistics Netherlands)

- P = the eligibility age in the year before the year in which the rise is considered

- 18.26 = the average time (in years) that Dutch policy aims for all people to spend in retirement while receiving State Pension; this represents the average PLE at 65 for the years 2000 to 2009

- 65 = the age at which life expectancy is calculated

This formula was designed to allow each person to spend an average of 18.26 years in retirement. As a result, all additional years of life are meant to be spent in employment (see Box 6 for more detail).[footnote 125]

If the increase in the eligibility age (V) as determined by the above formula is negative or less than 0.25 years, then the value of V is set at 0 (as the legislation does not allow for a decrease in the State Pension age on the basis of life expectancy – see Table 7. If the increase of eligibility age (V) is 0.25 years or higher, then increases can be no more than 3 months per year. If it is more, the excess is moved to the next year’s revision. The pensions law also requires the national statistics institute to publish life expectancy projections, with explanations of their uncertainty, and it requires that projections of the pension age be published with probability distributions and uncertainty intervals.

- However, in June 2019, the Dutch government agreed to slow down scheduled increases in the State Pension age due to the deceleration of increases in life expectancy as calculated by Statistics Netherlands. From June 2019, the SPa at that time (66 years, 4 months) was frozen for 2 years.[footnote 126]

- The Dutch government plans to revert to an AAM from 2025, with a change in the rate of indexation to life expectancy. Rather than a one-to-one matching (where every year of life translates into an additional year of work), the SPa will be increased by two thirds for every additional year of life expectancy from 2025.[footnote 127]

Sources: Formula from Ayuso and others (2021a); Royal Dutch Actuarial Association (2020). Additional information from Anderson (2019); OECD (2021a); Van Duin (2013).

Box 9: How State Pension age is calculated in Denmark

In Denmark, the indexation formula for the SPa has been represented as:

xrDNK(t) = 60 + [(e.P60 (t-15) + 0.6) – 14.5]

Within this formula:

- xrDNK(t) = SPa in year t in Denmark

- e.P60 = remaining life expectancy observed for people aged 60 over the past 2 years (using unisex PLE that takes life expectancy in 2004 to 2005 as a model)

- (t-15) = indexing variable that takes into consideration the notice period before the change in the SPa takes effect (i.e. the expected remaining life expectancy at 60 of those who are currently 45)

- 0.6 = the assumed increase in life expectancy (in years)

- 14.5 = the time (in years) that Danish policy aims for all people to spend in retirement while receiving State Pension

Danish policy is that people spend an average of 14.5 years in retirement: as a result, all additional years of life are meant to be spent in employment (see Box 6 for more detail). According to Ayuso and others (2021a), the overall aim of the current Danish indexation of State Pension age to life expectancy (as established in 2007) was to restore financial equilibrium.[footnote 128]

Life expectancy at 60 is calculated every 2 years using base and unisex data from Statistics Denmark.[footnote 129] The maximum increase in the State Pension age that can be approved is 1 year every 5 years (see Table 7). All increases are rounded to the nearest half year.[footnote 130] Any excess is moved to the next planned revision.

As a semi-automatic indexation, all pension age adjustments must be approved by the Danish parliament and take effect only 15 years later. The time lag is factored into the indexation mechanism used.[footnote 131]

Changes to the AAM used by Denmark have been proposed by an independent commission. Please see Box 7 for more information.

Sources: The formula is used in Ayuso and others (2021a), which cites no original sources. The formula incorporates additions from Nordic Social-Statistical Committee (2008). The original source for the 2007 introduction of the automatic mechanism is Beskæftigelsesministeriet (2007). The original source for the 2011 reform of the pension age is Retsinformation (2011).

Box 10: How State Pension age is calculated in Portugal

In Portugal, additions to the SPa after 2014 are most recently represented in national legislation by the formula:

Mn = ∑n t=2015 (EMVt-2 – EMVt-3) x 12 x 2/3

In this formula:

- M = the number of months to be added to the pension age as it was in 2014

- N = the year in which someone would be entitled to start to receive their pension

- EMV = life expectancy at age 65. Life expectancy is published annually by the Instituto Nacional de Estatistica, using an average from the preceding 3 years

- (EMVt-2 – EMVt-3) = the difference between life expectancy published 2 years previously (t-2) and that published the year before that, (t-3)

- 12 x 2/3 = this represents two thirds of any increase in observed life expectancy being added to the months of additional work life

The Portuguese system calculates additional SPa in months, which are then added to the existing SPa. There is no maximum or minimum increase possible that is included in the legislation.

Source: Formula from Presidência do Conselho de Ministros (2021). While not cited here, an earlier formulation of this indexation is also represented in Ayuso and others (2021b), which drew on Ministério da Solidariedade, Emprego e Segurança Social (2013).

Box 11: How State Pension age was calculated in Slovakia

The formula that represents the indexation of the SPa to life expectancy in Slovakia between 2012 and 2019 can be represented as:

xrSVK(t) = xrSVK(t-1) + [e.PX(t-7:t-3) – e.PX(t-8:t-4)]

Within this formula:

- xrSVK(t) = SPa in year t in Slovakia

- xrSVK(t-1) = SPa in the year before year t in Slovakia

- e.PX(t-7:t-3) = the five-year moving average in PLE observed between t - 7 and t -3

- e.PX(t-8:t-4) = the five-year moving average in PLE observed between t - 8 and t - 4

The State Pension age therefore builds on the previous year’s State Pension age: the difference between the newer life expectancy average (e.PX(t-7:t-3)) and the older life expectancy average (e.PX(t-8:t-4)) is added to the previous year’s SPa. Calculating the SPa based on moving averages in this way is recommended by the OECD.

The formula above calculates the difference between life expectancy in days. Under this formula, the State Pension age changes each year, and this could result in small incremental changes (a matter of days). This formula also incorporates one-to-one indexation: all additions to life expectancy are expected to be spent in work – with no corresponding increase to the proportion of time spent receiving State Pension.

- As discussed in section 2.2, a reform in 2019 changed how Slovakia calculated its SPa. From 2019, rather than being indexed to life expectancy, the SPa increased by 2 months per year until the SPa reaches 64 years.[footnote 132]

Source: Ayuso and others (2021a), which cites no primary sources.

2.3.2. Life expectancy is also considered when determining the SPa through mechanisms other than AAM

While only a few countries may formally have an AAM (as categorised by the OECD in 2021), other countries follow processes that involve consideration of the life expectancy changes in the country. These typically include having a statutory requirement to publish updates on life expectancy in relation to State Pension age, which governments and decision makers can then consider in terms of reform. Examples include:

- Czechia. According to the OECD, Czechia has a long-term planning policy that resembles a semi‑AAM of the SPa to life expectancy. The policy aims for 25% of life to be spent in retirement while receiving State Pension. This is put into practice by a report published annually that includes life expectancy calculations for every cohort between ages 25 and 54.[footnote 133] If life expectancy for at least one of these cohorts is calculated in a way that would mean more than 26% or less than 24% of life would be spent in receipt of State Pension, then the report signals this and considers what SPa would achieve 25% of life in retirement. However, there is no (legal or other) mechanism to translate these targets to changes in the statutory State Pension age.[footnote 134]

- Malta. In Malta, legislation requires that a report be provided by the Ministry for Social Security to parliament every five years. This report reviews the state of the pensions system and considers the changes in life expectancy, with the aim of ensuring that there is a stable ratio achieved between time spent contributing and time spent in retirement while receiving a State Pension. The report then prepares recommendations for any changes deemed appropriate.[footnote 135] This information is used by the Maltese government to decide any changes to the SPa.

- Current policy in the UK. As discussed in section 1.1, the Pensions Act 2014 requires consideration of the State Pension age in reference to life expectancy and other relevant factors via a statutory review every six years.

2.3.3. There are two main methods of calculating life expectancy

These two main ways are:[footnote 136]

- Period-based life expectancy: This is estimated using mortality data from across the population for a recent period (for example, a three-year average). In predicting life expectancy, these mortality rates are assumed to remain unchanged.[footnote 137] These calculations may be made by national statistics institutes (most common in developed countries).

- Cohort-based life expectancy: In this method, projected changes in mortality are used to estimate the life expectancy of each cohort (i.e. those born in the same year) depending on their gender.

In practice, there are different ways of estimating both PLE and CLE. Through national statistics institutes, countries frequently estimate population-wide life expectancy using observed and projected data. International bodies also produce life expectancy estimates for a number of countries which may be then used for international calculations.[footnote 138] For example, the United Nations produce country-specific projections of mortality rates based on projected changes in mortality rates after the SPa (i.e. cohort-based mortality projections); these are used to estimate life expectancy in Figure 3.[footnote 139]