Green Finance: Voluntary Carbon Markets in ASEAN, challenges and opportunities for scaling up

Published 20 October 2021

Voluntary carbon markets in ASEAN: challenges and opportunities for scaling up

Authors: Raúl C. Rosales (lead author), Priya Bellino, Marwa Elnahass, Harald L. Heubaum, Philip Lim, Paul Lemaistre, Kelly Siman, Sofie Sjögersten.

This report is the independent opinion of the authors.

Co-authors: Centre for Sustainable Finance, SOAS, University of London; Business School, Newcastle University; The University of Nottingham; National University of Singapore, Centre for Nature-based Climate Solutions; ARSARI Group; RHT Green

Industry contributors: Carbon TradeXchange; AXA Investment Managers; AirCarbon Exchange; Sylvera; ClimateSeed; Soil Capital Carbon; BNP Paribas

About this paper

This report is part of an overarching project developed in collaboration with the COP26 Universities Network and the British High Commission. The COP26 Universities Network is a growing group of over 80 UK-based universities working together to help deliver an ambitious outcome at COP26 and beyond. In this first ever collaboration of its kind, the network has brought together researchers and academics from the UK and Singapore to publish a series of four reports aimed at supporting policy development and the UK’s international COP26 objectives in Singapore and across Southeast Asia.

The reports focus on the following areas:

1) energy transition

2) nature-based solutions

3) green finance

4) adaptation and resilience

The bite-size and highly condensed papers provide a high-level understanding of the challenges and opportunities arising from climate science and policymaking in the ASEAN region, as we seek to transition to a greener economy. Readers are encouraged to review all four reports to gain a more comprehensive picture of climate change issues in the ASEAN region.

This report addresses the third thematic area: green finance. Written with the support of industry partners, it examines the rationale for carbon credits to be traded across ASEAN and assesses the role of institutional investors and regulators in developing a regional voluntary carbon market (VCM).

Carbon markets allow companies to buy or sell greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions allowances or to offset their carbon footprint to meet voluntary emissions reduction targets. The further growth and development of VCMs are of particular interest to Singapore. The country plans to become a major regional carbon services and trading hub and has sponsored several centres of excellence, including the Singapore Green Finance Centre.

The energy transition report connects with this green finance report through its approach to climate integration in ASEAN’s low carbon economies and sustainable energy transition plans. The green finance report provides perspective on the opportunities for an emerging VCM which will have important implications for the energy sector and has the potential to play a meaningful role in incentivising a shift in investment towards low-carbon energy technologies.

The Nature-based climate solutions (NBS) paper is directly relevant given the scale and significance of NBS in ASEAN to sequester carbon, contributing to a much-needed offsets supply for an efficient voluntary carbon market. Indeed, we dedicate a section to NBS under the title “Voluntary carbon markets: making the difference through nature-based solutions?”.

Finally, the Adaptation & Resilience paper presents the hazards, exposures and vulnerabilities that the ASEAN region is experiencing through both the physical impacts from climate change and the transition risks arising from its energy transition process. The green finance paper tackles these challenges from a carbon markets perspective and through real business case studies.

I. Contributors

Raúl C. Rosales is a Senior Executive Fellow at Imperial College Business School and serves as a Member of the Singapore Green Finance Centre Management Committee; currently Senior Advisor for Orchard Global Asset Management LLP. Former Senior Banker for Energy at EBRD, he has a background in the financial industry spanning 30 years. He holds a PhD in Civil Engineering with a specialization in sustainable infrastructure and energy investments.

Priya Bellino is a sustainable finance consultant based in Singapore, supporting the Singapore Green Finance Centre. Priya has 17 years of experience in risk management and derivatives at Goldman Sachs.

Marwa Elnahass is Associate Professor of Accounting and Finance at Newcastle University. She holds 20+ years of international and interdisciplinary research experience as well as industry engagements in accounting, banking and climate change. Marwa is as an associate editor for several accounting/finance journals and works with UK research councils like GCRF & ESRC).

Harald L. Heubaum is Associate Professor in Global Energy and Climate Policy and Deputy Director of the Centre for Sustainable Finance at SOAS University of London. He is also Director of the sustainable finance data initiative SUFINDA. His research interests include alignment between global climate, energy and financial governance, and climate and sustainable finance policies.

Paul Lemaistre leads business development and carbon services for the Arsari Group, Indonesia. Paul has worked in policy, strategy planning, business development and consulting focusing on REDD+ and carbon markets for the last 11 years.

Philip Lim serves as a Council Director at The Conference Board and is a Principal Consultant at RHT Green. He has 30+ years of international experience at Chevron and Johnson & Johnson. Philip’s current focus is on impact investing, ecosystem development and sustainability/ESG advisory.

Kelly Siman is a Research Fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Centre for Nature- based Climate Solutions where she researches governance and regulatory aspects of nature- based climate solutions, with a focus in the ASEAN region.

Sofie Sjögersten is Professor in Environmental Science at the University of Nottingham. Her research over the last 23 years focuses on the impacts of land use and climate change on ecosystems and ways in which we can mitigate climate change by protecting and managing natural ecosystems.

II. Abstract

1. As the low-carbon transition gathers pace, voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) are growing around the world alongside and, in some places, in lieu of compliance markets.

2. ASEAN member states have experimented with VCMs in the absence of more formalised government-led schemes. The paper sets out policy considerations for ASEAN and reviews the current accounting practice applied to carbon finance.

3. Together with other policies, well-designed VCMs can help reduce costs for emerging climate technologies, increasing their chances of adoption at scale and achieving more significant decarbonization and market efficiency across the region.

4. Transparency (credits linked to genuine emissions reductions), liquidity (adequate supply of high-quality, standardized credits reaching the market) and pricing (sufficiently high and transparent) are key drivers to mobilize funds through venture capital and institutional investors and secure the integrity of VCMs.

5. The absence of a harmonized financial reporting framework for emission allowances and voluntary offsets, and lack of discourse on the assessment of underlying assets are hampering the growth of VCMs in ASEAN.

III. Introduction

This impact policy paper addresses voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) as a tool in lowering net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the ASEAN region. It aims to identify opportunities and innovation gaps in the VCM to support ASEAN’s shift towards a low-carbon economy.

Southeast Asia is one of most vulnerable regions exposed to the adverse impacts of climate change[footnote 1]. To address the challenges of a rapidly warming world, ASEAN member states are actively collaborating on their commitments under the Paris Agreement, including through the development of various mechanisms, policies, strategies, and action plans for GHG emissions reductions under the Special ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on Climate Action. In addition to actions and collaboration among governments, there has been significant momentum for VCMs among private sector actors in the region. For example, while writing this paper, DBS, Singapore Exchange, Standard Chartered and Temasek— have launched the global exchange carbon trading platform Climate Impact X.

This policy paper explores whether there is a rationale for scaling up VCM platforms in ASEAN and outlines practical suggestions and strategic insights for policymakers, regulators, institutional investors, and industry platforms. Drawing on consultations with leading financial institutions and key VCM stakeholders, it presents several real-world business models of VCMs from a capital markets perspective, connecting with nature-based solutions (NBS) to mitigate GHG emissions.

First, AXA IM is pursuing a comprehensive decarbonization strategy with transition finance bonds, purchasing carbon credits and embedding the approach in its portfolio management allocation to achieve both decarbonization and improved performance.

Second, BNP Paribas has put the energy transition and the shift to a low carbon economy at the heart of its strategy. The paper presents the bank’s key international policy measures to respond to the scale of the climate crisis, including NBS in Kenya.

Third, Soil Capital’s innovative approach enables farmers to generate verified carbon certificates and sell them through voluntary trading platforms. Fourth, Sylvera provides information on nature- based offset projects, acting as an independent data verifier, and connecting the dots of NBS with cutting-edge technology, drawing on a proprietary rating methodology.

Similar voluntary carbon platforms and partnerships may develop in ASEAN, extrapolating AXA IM, BNP Paribas’ decarbonization strategy, ClimateSeed, or Soil Capital’s approach to serve the needs of asset owners, while helping to develop sustainable businesses and mitigating the effects of climate change.

The document outlines Singapore’s policy initiatives and private-public partnerships which can play a key role in the development of a regional carbon services hub and lead Asia’s energy transition with a well-functioning carbon markets ecosystem. In turn, this may pave the way for VCMs to play a more impactful role globally.

Moreover, as we embark on the journey towards a unified accounting framework across the world, many institutional and innovative hurdles still need to be addressed. Policy makers need to consider how much effort and attention are required in the coming years to improve the consistency within complex carbon accounting regimes in relation to GHG emissions. Without sufficient accuracy and transparency, accounting for voluntary credit trading markets will become vague and complex.

When situated in the right policy framework, VCMs can be a key tool for lowering GHG emissions in Southeast Asia and around the world. Although they are still relatively small by overall volume today, estimated to be over $5.5bn in value[footnote 2] compared with a global compliance market in excess of $270 billion[footnote 3], the market has grown rapidly in the past few years. Despite the economic downturn due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 ushered in record-high levels of 222 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MMtCO2e) in offset credit issuance.

IV. Policy recommendations

To scale and strengthen VCMs in ASEAN, governments, regulators, asset managers and development banks may consider the following measures.

- push for effective operationalization of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement to set clear rules governing international carbon market mechanisms. This will provide reporting and institutional arrangements, including establishing the new Article 6.4 crediting mechanism, which can support the growth of the voluntary carbon market

- obtain agreement between IFRS and international accounting institutions on carbon finance accounting and harmonized practices for financial reporting. High-quality information is critical for capital markets and carbon offsets

- incorporate transparency into the valuation and reporting of carbon offsets to encourage a level playing field for trading. There has been no specific discourse to date regarding the valuation of assets (and liabilities) capable of producing (and using) the credits that underpin a carbon trading market, nor related to revenues or expenses from carbon emission credits

- agree common standards and quality criteria for carbon credits across ASEAN to increase market liquidity, improve risk management, and finally to seek alignment on the pricing and disclosure of carbon emissions

- foster venture capital investments for agricultural regenerative businesses involving development finance institutions and governments as anchor equity investors and providing credit enhancement mechanisms to develop NBS projects

- facilitate impact investment funds and credit enhancement mechanisms in carbon farming to develop an innovative industry for agribusiness, setting up a carbon market-maker’s framework to ensure the exchange of carbon credits

V. Part one: insights into carbon markets: a policy approach

V.1. Carbon finance in ASEAN

What role can carbon markets play? The global picture

Achieving the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting the rise in global average surface temperatures to well below 2°C (and preferably 1.5°C) above pre-industrial levels depends on countries ratcheting up their nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Together with other policies, markets can play an important role in putting a meaningful price on carbon, enabling market participants to efficiently allocate capital toward low-carbon solutions and delivering the kind of emissions reductions necessary to avoid the worst impacts of a runaway climate emergency[footnote 4]. Well-designed markets can be cost-effective and can crowd in private finance, which can be especially important for countries emerging from the Covid-19 pandemic with strained public finances and increased public debt[footnote 5].

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement envisions the creation of international carbon markets in which one country pays for the emissions reduced in another and then counts these reductions towards its own NDC target[footnote 6]. Economic analysis has found that trading these so-called Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) could nearly double global emissions reductions by 2035 at no additional cost to governments[footnote 7]. Beyond its potential cost- effectiveness, international emissions trading can enhance knowledge and technology transfers as well as present an opportunity for investors to participate in a key future market, be it in the generation of ITMOs or in their trade. Key prerequisites for such private sector participation are the existence of an effective institutional framework and clear rules and standards defined by governments[footnote 8].

Around the world, 39 countries are currently covered by national or supranational compliance carbon markets. The largest and most prominent of these is the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) which launched in 2005 as the E.U.’s main joint approach to meeting its Kyoto Protocol obligations. The EU ETS has overcome a number of fundamental challenges, including, most prominently, an over-allocation of emissions allowances and subsequent collapse in prices in its early years[footnote 9]. In May this year, allowance prices rose to above €50 for the first time, with traders betting on further market tightening as a consequence of more aggressive E.U. climate targets[footnote 10]. However, while higher carbon prices are generally seen as necessary for more rapid emissions reductions in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement, lower prices have still been found to incentivize investment in climate-friendly technologies and practices and, thus, to contribute to cutting emissions[footnote 11].

The Paris Agreement has created opportunities to integrate the various carbon markets currently in existence and develop new compliance markets by drawing on the experience of the EU ETS and other trading systems, including voluntary carbon markets.

Voluntary carbon markets

Voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) refer to the trading of voluntary carbon credits, usually by private actors, which offset emissions elsewhere. They can be used, for example, to help companies meet voluntary corporate climate targets in support of the low-carbon transition. Compared to compliance markets, the value of VCMs is relatively small – the Taskforce on Voluntary Carbon Markets sees the potential for a liquid voluntary market to be between $5 and $50 billion by 2030[footnote 12]. This compares to $277 billion in total value for global carbon markets in 2020, 90 percent of which was due to the compliance-based EU ETS[footnote 13]. However, voluntary markets have grown rapidly in recent years, with buyers retiring credits for nearly 100 million tons of carbon-dioxide equivalent in 2020, more than twice the amount achieved in 2017[footnote 14].

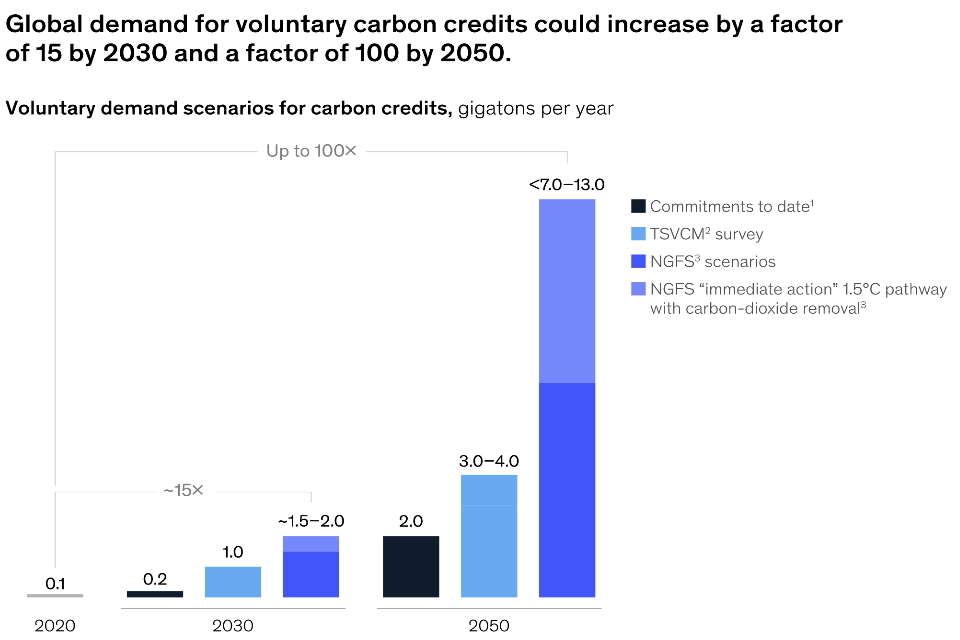

Global demand is set to increase further, with some projecting an increase by a factor of 100 by the middle of the century (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Voluntary demand scenarios for carbon credits, gigatons per year. Source: McKinsey & Company

Global demand for voluntary carbon credits could increase by a factor of 15 by 2030 and a factor of 100 by 2050.

While voluntary markets have faced some problems, including credits linked to questionable emissions reductions, limited pricing information and transparency, unclear taxonomies and guidelines, and a lack of liquidity, they can contribute to raising the profile of climate action in places where compliance markets have not yet been established[footnote 15]. But even when compliance markets are already in place, VCMs can continue to play an important complementary role.

Voluntary markets can also help support financial flows to the Global South, as abatement activities in low- and middle-income countries can provide a cost-effective source of carbon credits traded in the market. They can further help reduce costs for emerging climate technologies, increasing their chances of adoption at scale and achieving greater decarbonization[footnote 16]. The use of technology solutions such as blockchain can address information and transparency issues, for example through enabling the effective tracing of ITMOs and preventing their double-counting[footnote 17].

Carbon markets in ASEAN

Across ASEAN – a region rich in biodiversity, forests and renewable energy sources such as hydro, solar and geothermal, investments in all of which could generate a significant number of ITMOs – several member states have taken steps to implement both voluntary and compliance markets (see table 1). In March 2021, Indonesia launched a pilot voluntary ETS for the power sector and is planning to start a national compliance system by 2024. Vietnam passed a law in November 2020 to create a national compliance system by 1 January 2022. Legislation to establish a national ETS covering large emitting sectors is under consideration in the Philippines. Thailand is considering establishing a national ETS.

These developments follow the establishment of compliance carbon markets elsewhere in the Asia and Pacific, including national ETSs in South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and Kazakhstan. China launched its own national trading scheme covering more than 2200 coal and gas power plants in February 2021 following a 10-year trial period in seven local pilot carbon markets[footnote 18]. In addition, subnational systems exist in Japan (Tokyo and Saitama).

Table 1. Overview of carbon markets in ASEAN. Source: author’s own compilation

| Indonesia | voluntary pilot, compliance market by 2024; Government Regulation on Environmental Economic Instruments passed in 2017 mandates implementation of trading system within seven years; MRV guidelines have been released |

|---|---|

| Philippines | compliance market under consideration; Low Carbon Economy Act conditionally approved in 2020 contains provisions for a domestic ETS, although no timeline has been set |

| Singapore | voluntary; developing a taxonomy and guidelines for carbon credits as part of its push to secure a role as a hub for the global voluntary offset market |

| Thailand | voluntary, compliance market under consideration; Thailand Voluntary ETS launched in 2015; national Climate Change Master Plan (2015–50) refers to carbon markets as potential tool to achieve emissions reductions in line with the Paris Agreement |

| Vietnam | compliance market by 2022; Law on Environmental Protection adopted in 2020 establishes mandate to design a domestic ETS and crediting mechanism, allowing for the inclusion of international efforts |

As the most mature of the carbon markets in Asia, the Korea ETS (K-ETS) sets an example for future developments in ASEAN. Launched in 2013, K-ETS now covers 73.5% of domestic GHG emissions This system allows financial intermediaries to participate in the secondary market and trade emissions allowances and converted carbon offsets on the Korea Exchange (KRX)[footnote 19]. By switching from physical ‘over-the-counter’ markets to exchange trading, new market participants do not need to invest in establishing bilateral trading, credit and settlement relationships with incumbents but can instead trade through the exchange as a single point of entry, creating opportunities for a diverse group of market players[footnote 20].

ClimateSeed provides an example of how an integrated VCM may work. With access to proprietary data and a standardized methodology to monitor the effectiveness of nature-based projects, carbon offset ratings platform Sylvera is able to enhance and standardize the due diligence performed by players like ClimateSeed, allowing for a greater level of transparency and confidence for clients. Furthermore, by relying on its technology and efficiencies of scale, it can – reduce the cost of monitoring the projects on an ongoing basis.

BNL Paribas case study: a case study in carbon credits, a financial instrument in capital markets

BNP Paribas has put the energy transition and shift to a low carbon economy at the heart of its strategy and purpose.

The global economy can only be carbon neutral by 2050 and achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement with engagement of the financial sector. Through progressive sector policies and product innovation, BNP Paribas has been prioritising the transition to a low carbon economy for the last decade. Recently the bank has undertaken additional steps to accelerate its commitment to net zero.

BNP Paribas in coalition with other large banks developed a common methodology for measuring/aligning loan portfolios with the Paris Agreement (PACTA). PACTA covers the majority of high emitting greenhouse gas sectors including power generation, oil & gas, transportation, steel and cement. The bank has already started implementing this open-source methodology on two of these sectors: power generation where its activity is already aligned with a well-below 2° scenario and on upstream O&G by setting a 10% reduction target by 2025 of its credit exposure on this sub-sector.

To respond to the scale of the climate crisis and mobilise the banking industry towards net zero, BNP Paribas – alongside 42 banks joined the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA). By being part of the NZBA, BNP Paribas supports a commitment to transition the bank’s lending and investment portfolios to finance a net zero economy by 2050 at the latest.

In implementing and reaching targets for all scopes of emissions, offsets can play a role to supplement decarbonisation in line with climate science. The bank notes that offsets should always be additional and certified. Since 2010, BNP Paribas has therefore supported the Wildlife Works Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project.

This is a vital forest conservation project located in southwestern Kenya. Wildlife Works has shown the community a more sustainable way to produce nutritious crops without the need to clear more trees, preserving and restoring 500,000 acres of forest and funding community employment, clean water and education opportunities.

On progressing the development of climate hedging and voluntary emissions reductions, BNP Paribas closed the first Voluntary Emission Reduction (VER) transaction with a wealth fund in March 2020. Over the last 10 years, BNP Paribas has been offering its clients sustainable structured products and VERs for CO2 emission reduction purposes.

With increasing pressure on the bank’s clients to become carbon neutral by 2050, many are looking into adding an offsetting pillar to their emission reduction strategy. Clients go through BNP Paribas in order to buy VERs for a number of reasons, including access to quality projects, hedging capabilities, and minimising counterparty risk.

On the investment side, BNP Paribas Asset Management in collaboration with the bank’s Global Markets teams launched the THEAM Quant – World Climate Carbon Offset Plan Fund, which provides ESG exposure to equities with a robust energy transition strategy or lower CO2 footprints. The remaining carbon footprint of the portfolio is offset quarterly through the purchase of VERs through the Kasigau Corridor REDD+ project.

V.2. Policy considerations from Indonesia

The United Nations REDD+ program (CIFOR), running since adoption of the Bali Road Map at COP13 in 2007, today counts 47 REDD+ projects across Indonesia, varying in size, type, and developers from the private sector, government, or community-based organizations, with at least 13 validated by leading certifications Verra and Plan Vivo. However, despite TSVCM noting up to ⅔ of a potential credit offsets market between 1-5 Gigatons of CO2e reductions by 2030 sourced from NBS projects, significant challenges remain on the ground for REDD+ and NBS project developers.

Access to early-stage venture financing

Developers are conscious of the need to deliver ‘high quality’ projects that are ecologically and socially sustainable, however, REDD+ and NBS project development has stifled due to lack of early-stage funding for forestry projects. Early-stage financing will help project developers produce feasibility assessments leading to informed investment decisions to further project development and de-risk project feasibility, that is thorough assessment, measuring, monitoring, validation and verification. Variables which need early screening include assessments of carbon credit potential, legal certainty, land tenure, assessments of social impacts on local and indigenous communities. Early venture financing also allows the time needed to ensure ‘high quality’ including highly valued co-benefits of biodiversity conservation, rural livelihoods, adaptation and non-carbon-based climate stability. Access to high-risk appetite financing is particularly important when considering the price uncertainty of voluntary credits. Though recent price signals[footnote 21] suggest that demand for carbon credits will jump significantly in the coming years, up to 80% of forest carbon projects will be financially unviable at current carbon prices[footnote 22].

Alignment with government jurisdictional programs

In Indonesia there have been renewed calls to focus on jurisdictional approaches to REDD+. Government-led state-level programs effective in reducing deforestation on a large scale, rewarded with cash payments from Results Based Payments (RBP) programs, and financed by a multilateral consortium of donors and funders. The leading RBP program in Indonesia is the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF)[footnote 23] in East Kalimantan, and a BioCarbon Fund worth $60 million is planned for Jambi province. Numerous benefits of these jurisdictional programs include: government management of complex large-scale land-use change; channelling offset revenues to community-driven projects or climate change adaptation programs beyond the scope of private developers; and monitoring across jurisdictional landscapes to better address issues of non-additionality, leakage, and carbon reversals.

RBP programs do not sufficiently incentivize private REDD+ developers. For example, the FCPF program in East Kalimantan has committed to reduce up to 86.3 mtCO2e over the next five years (2020-2024), at a carbon price of $5 per ton CO2e, with a signed Emission Reductions Payment Agreement (ERPA)[footnote 24]. This price is perceived to be undervalued considering anticipated price increases in the voluntary market. Therefore, government and private sector participants could lose out in an RBP scheme. The typical REDD+ project developer may conclude, therefore, that their best course of action is to work outside of government-nested programs. For institutional investors, today’s demand for early financing demonstrates an opportunity to lock in engagement and access to NBS generating long-term exportable offsets (and other SDGs) at attractive costs relative to high capex renewables projects.

V.3. Policy considerations from Singapore

Traditionally, the reduction of GHG emissions in developing countries was implemented on a per-project basis predominantly led by governments with international support. Under VCM, the private sector will play a central role as executors of the emissions reduction activities, financing sources, and investors.

The idea of an ASEAN carbon emissions mechanism recently gained traction when the 2020 Regional Dialogue on Carbon Pricing (REdiCAP) adopted a platform to allow for regular exchange of experiences and mutual learning.

Singapore took the lead as the first country in ASEAN to introduce a carbon tax of S$5 per tonne of GHGs in 2019, as part of a multipronged strategy, which also includes an absolute emissions reduction target and promoting renewables. It committed itself to gradually raise the tax from 2023 onwards to between S$10 and S$15 per tonne by 2030. Additional voluntary carbon offset markets serve to complement this tax.

The concept of a global VCM based in Singapore took shape when the Emerging Stronger Together (EST) Task Force was set up in May 2020 to identify transformation and growth opportunities amid the challenges of COVID-19. The EST created a Sustainability Alliance for Action (AfA), an industry-led coalition aimed at establishing Singapore as a premium carbon offset trading hub. It envisioned (i) a technology-enabled verification system for high quality nature-based solutions (carbon verification), (ii) a marketplace and exchange for high quality carbon credits (carbon market), and (iii) a green standard and one-stop solution for companies to measure, mitigate, and offset their carbon footprint (carbon-conscious society).

In Singapore, Temasek, the Singapore Exchange and banks DBS and Standard Chartered announced the launch of Climate Impact X (CIX) in May 2021, a global exchange and marketplace for carbon credits traded in the voluntary offsetting market[footnote 25]. CIX will focus on credits generated through nature-based solutions (NBS) such as the protection and restoration of mangroves or wetlands. CIX could fill the gaps of fragmented carbon credit markets characterized by thin liquidity and credits which are difficult to verify. By forming a coalition of buyers and sellers committed to trading high quality credits, demand can be signalled more accurately, giving sellers the confidence to scale up supply. This will enable efficient price discovery of carbon and catalyse the development of a more robust carbon market. The deployment of cutting-edge technology such as satellite monitoring and blockchain would enhance the transparency, verifiability and scalability of the nascent VCM.

VI. Part Two: Voluntary carbon markets – A private sector response

VI.1. Carbon offsets: Why do they matter? A financial markets response

The trend line for VCMs by volume and value has been increasing globally, including in ASEAN where carbon markets exceeded $100 million in value in 2020 compared to less than $5 million in 2010[footnote 26]. This trend is expected to continue as more countries and companies in the region make carbon neutrality commitments and the workforce is increasingly equipped to measure and calculate carbon footprints. Additionally, growing global demand for offsets presents a significant economic opportunity for nature-based project developers and associated communities within ASEAN.

Carbon offsets as financial products and investable assets

The demand for voluntary carbon offsets in a restricted supply market results in economic value which can be traded and exchanged. Emissions sequestered and voluntarily offset can therefore be seen as an evolving asset class, which may be attractive for long-term investors due to its “liquidity, correlation properties, and prospective risk premium”[footnote 27].

Table (Figure 2). Growth of Carbon Market in South East Asia. Reproduced from Allied Offsets (2021), “Report on nature-based solutions South East Asia”.

| Year | Value ($M) |

|---|---|

| 2009 | 0 |

| 2010 | 1.72078 |

| 2011 | 4.227217 |

| 2012 | 6.476687 |

| 2013 | 11.62586 |

| 2014 | 23.47094 |

| 2015 | 36.33679 |

| 2016 | 44.23397 |

| 2017 | 55.84471 |

| 2018 | 65.24428 |

| 2019 | 82.03044 |

| 2020 | 107.2111 |

Constrained supply

The limited supply of NBS credits and potential concentrations has price implications in a spot or forward market. The lag time between new developments and ex-post emissions verification and certified capture in a registry is between 3-5 years. Additionally, unlike the energy or soft commodities markets, the supporting data relating to the supply, volume and quality of NBS credits is sparse. Because there are multiple platforms where offsets can be listed, arbitrage across platforms and naked short selling could also occur. To address this, VERRA and other certifiers are looking to define an ‘ex-ante’ verification process for the financing of new projects.

Price stability

In any supply-constrained market, the outlook on pricing is imbalanced. Most carbon platforms have project developer set carbon prices’ bulletin-board’ style, and the global market does not yet capture the demand for offsets like a global bid/ask market would. This can lead to outcomes where supply is bulk purchased from project developers at very low prices in the primary market and sold at significantly higher margins in the secondary market amongst large corporates or financial institutions. Nature-based project developers (predominantly in emerging markets) with limited awareness of the global market prices (due to scarce public data and transaction transparency) can lose out in the short-medium term as this market rallies. Monopolistic purchases of credits will inevitably lead to price control by a few large players, pricing out many companies (particularly in developing nations) and leading to an expensive and inefficient market over time. Platforms like ClimateSeed prohibits onward title exchange of offsets, while AirCarbon supports secondary market activity.

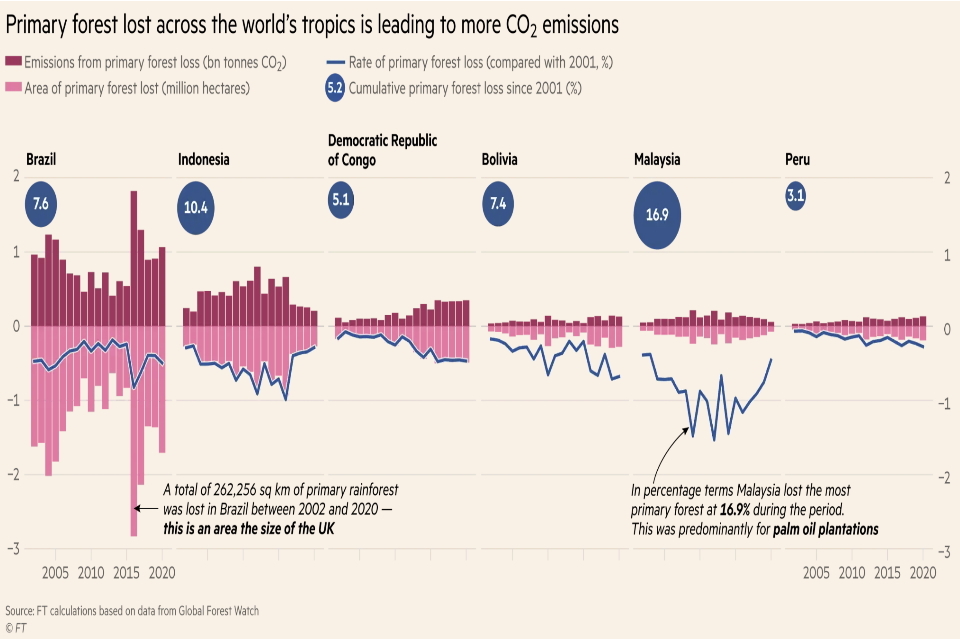

Figure 3 illustrates that primary forest lost across the world's tropics is leading to more CO2 emissions. A total of 262, 256 sq km of primary rainforest was lost in Brazil between 2002 and 2020.

Securitization and financial products

Polluting corporates can purchase forward derivative contracts from financial institutions, locking in supply of offsets for future emissions. Institutional investors and family offices[footnote 28] are investing in carbon credits to diversify investment portfolios while simultaneously offsetting financed emissions. Over time, greater offset differentiation and complexity of financial products will be able to satisfy even retail consumers, for example with Enhanced Transparency Frameworks (ETFs) linked to nature-based solutions. The challenges around transparent pricing, available data, and standards may increase as the market scales, there will also be more opportunity to understand and mitigate these challenges.

Reporting and disclosures in ASEAN

Companies across ASEAN are in their early stages of sustainability assessments and reporting and are still two to four years away from understanding their demand for offsets. In anticipation of the demands from net-zero commitments, demographic profiles, and forecasted energy demands, ASEAN players are likely to actively participate in voluntary carbon markets as an investment opportunity as well as a long-dated hedge, regardless of their current GHG emissions calculations. The emergence of transition finance products could link the financing of decarbonization strategies to the financing offset mechanisms. In the absence of an ASEAN-wide policy around disclosures and carbon accounting, the challenge of cross-border emissions and NDCs persists. There is an opportunity to develop an ASEAN climate commitment and standards to maximize cross-border knowledge, technology, and markets to scale emissions reduction initiatives.

Technology and innovation

Areas drawing venture capital include new technologies in carbon renewal, sustainable use of resources, and ecosystem restoration[footnote 29]. SoilCapital and Sylvera are useful examples of new players disrupting the market. Additionally, Temasek with Blackrock have started Decarbonization Partners to advance decarbonization solutions and DBS, Temasek and NUS are leading an accelerator for climate solutions[footnote 30]. Other ASEAN unicorns like Singapore gaming company Razer have set up a $50 million fund for green start-ups[footnote 31], and ride-hailing Indonesian company Gojek are offering a GoGreener carbon offset in the mobile app[footnote 32]. This intersection of climate innovation and e-commerce in ASEAN presents an opportunity to scale private financing.

Carbon quality and standards

Sylvera’s business model provides useful lessons on the importance of market-wide quality grading and rating of carbon offsets. A standard approach is needed for market efficiency in primary and secondary markets (ex-poste or ex-ante). Project developers need to understand the market rating expectations to assess feasibility and financial viability. Importantly, where Indonesia and Malaysia have suffered extraordinary levels of primary forest loss in the last 20 years[footnote 33], a unique regional mindset shift and business opportunity must be presented to financially incentivize companies and communities to transform interaction with local forests. Much education through government support is needed to embed sound practices of traceability, additionality and use of registry as well as knowledge around quality, vintage and related ESG outcomes driving price signals.

A helpful case study looking at market efficiency responding to why carbon offsets matter is AXA IM and assessing the impact of Sylvera’s data would allow for the selection of offsets that meet a minimum standard. The point is that clear data offers the key to ensuring the integrity of net-zero financial products.

AXA IM. A case study in decarbonization from capital markets perspective, and carbon credits

Joining the newly created Net Zero Asset Managers initiative, AXA IM has committed itself to bringing carbon emissions across all assets to a target-based net zero goal by 2050 or sooner. This initiative has been joined by 30 founding investors, representing over $9 trillion of assets under management, and working in collaboration with clients.

From a capital markets perspective, AXA IM has been a proponent of the decarbonization financing of carbon intensive industries to achieve Paris Agreement Goals. In 2019, the company published an influential paper on the need to create a new asset class called Transition Bonds. Following this, launched an industry working group assessing market guidance for such a capital market instrument.

In January 2020AXA IM began their work as co-chairs of the newly established Climate Transition Finance Working Group. This was set up under the auspices of the Green and Social Bond Principles to press forward the concept of transition financing – where companies in carbon-intensive sectors raise funds in capital markets for their decarbonization efforts. The group has attracted more than 80 institutions ranging from corporates, investors, investment banks and other stakeholders.

Through its quantitative equity investment platform, Rosenberg Equities, AXA IM have developed an equity carbon offset strategy. The strategy invests into companies that support the transition to a low carbon economy while divesting away from the worst polluters. The resulting portfolio will have a significant carbon footprint reduction and the remaining emissions can be compensated through the purchase of carbon credits.

While writing this Policy Paper, AXA IM acquired Climate Seed from BNP Paribas Securities Services. This acquisition through the firm’s investment impact strategy and is aligned with the policy recommendations we suggest.

VI.2. Voluntary carbon markets: Making the difference through nature-based solutions?

Four of the top ten countries most susceptible to climate change risks are in the ASEAN region[footnote 34]. Estimated land and property loss, biodiversity and environmental devastation, as well as loss of ecosystem services is expected in most of the predicted climate scenario models. In the three likely scenarios, ASEAN is, economically, the hardest hit region in the world, with a projected 37% GDP loss in a worst-case scenario[footnote 35]. On average this is valued between U.S. $2.8-4.7 trillion in GDP loss in Asia annually – more than two thirds of the global total[footnote 36].

Table 2. Simulated economic loss impacts from rising temperatures in % GDP, relative to a world without climate change (0°C).

Reproduced from the Swiss Re Institute (2021), “The economics of climate change: no action not an option”.

| Temperature rise scenario, by mid-century | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-below 2°C increase | 2°C increase | 2.6°C increase | 3.2°C increase | |

| Paris target | The likely range of global temperature gains | Severe cases | ||

| Simulating for economic loss impacts from rising temperatures in % GDP, relative to a world without climate change (0°C) | ||||

| World | -4.20% | -11.00% | -13.90% | -18.10% |

| OECD | -3.10% | -7.60% | -8.10% | -10.60% |

| North America | -3.10% | -6.90% | -7.40% | -9.50% |

| South America | -4.10% | -10.80% | -13.00% | -17.00% |

| Europe | -2.80% | -7.70% | -8.00% | -10.50% |

| Middle East & Africa | -4.70% | -14.00% | -21.50% | -27.60% |

| Asia | -5.50% | -14.90% | -20.40% | -26.50% |

| Advanced Asia | -3.30% | -9.50% | -11.70% | -15.40% |

| ASEAN | -4.20% | -17.00% | -29.00% | -37.40% |

| Oceania | -4.30% | -11.20% | -12.30% | -16.30% |

Nature-based climate solutions (NBS) provide co-benefits such as coastal protection to sea level rise and flooding prevention, providing critical natural infrastructure protection to climate- related events. NBS, as defined by the IUCN, are mitigation “actions to protect, sustainably manage, and restore natural or modified ecosystems that address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, simultaneously providing human well-being and biodiversity benefits”[footnote 37]. Nature already stores carbon and mitigates anthropogenic GHG emissions with about 25% of all emissions already absorbed by plants, soil, and marine ecosystems[footnote 38]. By protecting, managing, and restoring the various terrestrial habitats and peatlands in the ASEAN region would have pronounced paybacks—reducing emissions by up to 1.35 Gt CO2 yr-1 or ~20% of all tropical NBS [footnote 39], [footnote 40]. Although this opportunity is substantial, only a few carbon offsets projects (< 20) are currently operating in the region, with current investments representing only ~0.03 GtCO2 yr-1 of the potential[footnote 41].

Challenges in identifying, calculating, and capturing projects in ASEAN

Accurate datasets of peatland area and loss and data on carbon stocks, fluxes, and emission factors are essential in estimating national-scale sinks and emissions for NDCs. However, there are still significant gaps in knowledge and uncertainties regarding the impacts of different anthropogenic disturbances on peatlands, particularly regarding the effectiveness of different NBSs in mitigating the negative impacts of disruption and preserving the positive benefits that these ecosystems provide [footnote 42], [footnote 43]. Furthermore, this lack of data means that it is hard to precisely quantify the carbon credit value for a particular mitigation option for a specific location.

Key investable solutions

Protecting high-quality natural forests and mangroves is a key investable solution, saving significant carbon stocks in forests, peatlands, and coastal zones at risk of deforestation. The Southeast Asian region is estimated to generate approximately U.S. $19.6 billion per year by protecting terrestrial forests at risk from deforestation, with the largest potential within Indonesia (U.S. $10.1 billion per year) and Malaysia ($2.6 billion per year)[footnote 44]. Moreover, since the region has the highest geographic density of carbon assets globally, companies investing in NBS projects could see a return on investment of U.S. $27.5 billion per year[footnote 45].

To increase carbon uptake in forests and peatlands, restoration of degraded areas currently not under agricultural production is a key opportunity to remove large quantities of carbon from the atmosphere while not causing large conflicts with other land uses and delivering co- benefits. This is a particularly important option for the extensively degraded and fire-prone peatland areas of Indonesia and Malaysia, where solutions can be implemented at scale and with rapid positive impacts. Raised water tables and reduced nitrogen fertilizer inputs are key strategies that should be implemented for land-based solutions to reduce emissions.

For large companies, changes can be regulated via permits and their adherence to certification schemes, such as RSPO or FSC, with carbon credits used as a financial tool to encourage producers to improve their practices (e.g. financing initial costs for installing dams raise water tables; reduced impact logging in timber concessions; conservation set-asides of high conservation value forests). For smaller producers, training and support from agricultural extension services and simple direct access to financing options can accelerate change.

A key challenge in the identification of key investable solutions will be to quantify the cost effectiveness, legal feasibility, and economic viability of various NBS, and to be able to prioritize actions against one another. These processes will be critical to inform and identify priority actions to help achieve long-term climate mitigation and adaptation objectives.

Quality of carbon credits

The highest quality carbon credits protect existing carbon stocks and deliver reduced GHG emissions in the long term along with co-benefits such as reduced air pollution, improved biodiversity, improved water quality and availability, and new financial opportunities, including new markets and tourism.

Policy support and financing is needed to address several barriers to NBS implementation. Development costs, land-use constraints, and operational limitations can increase the difficulty of setting up some NBS projects. If areas identified for carbon credit projects are already used for agricultural production, implementation of NBS projects could displace livelihoods, compromise food security and lead to land rights issues with the landowners. Therefore, NBS restoration projects need to target areas not currently being used. For agricultural production areas, discussions with local communities and governments are central to identify suitable NBS projects.

The long-term nature of restoration and limited data on verification for restoration projects pose risks to financing despite their large NBS contribution. Furthermore, long-term security of carbon stocks within NBS projects requires site maintenance and protection against anthropogenic and natural treats, including illegal logging, tree diebacks and forest fires. Therefore, continuity of investment and co-production of carbon credit projects with local communities are critical factors for success.

Research needed to develop high-quality carbon credit projects

The quality and scope of projects can be strengthened by supporting research targeted toward identifying discrete features of high-quality carbon credits and novel verification techniques. At present, a carbon credit for one hectare of palm oil plantation is valued the same as one hectare of dense primary rainforest even though the rainforest credit holds far more biodiversity benefits and other co-benefits than the palm oil plantation.

Key opportunities to improve high-quality carbon credit projects include:

- improved mapping of above and below carbon storage of intact peat swamp area. Forest preservation is of particular relevance to the carbon-dense peatland

- quantification, via field-based measurement, of the impacts of specific mitigation options (e.g. restoration, fire prevention, improved nutrient management and raising of water levels) regarding emissions reduction and their scalability

- collaboration with local farming communities, focusing on alignment of the credits’ objectives and local socio-economic agendas to ensure long term protection of projects

- early-stage financing to support the identification and feasibility study of NBS projects, including financing schemes for project developers, similar to the Geothermal Resource Risk Mitigation Facility (GREM) run by the World Bank and the state-owned infra finance facility in Indonesia, and the Green Climate Fund disbursement entity

For NBS to truly be a market-based commodity, quality verification of NBS credits are critical. Currently, the process is highly specific to the types of projects[footnote 46] and labour intensive, often with resource-heavy ground-truthing. As a result, while the cost of nature-based carbon is currently three times that of renewable energies, some specific types of projects, when accurately reflected for social cost, maintenance, and labour, can cost U.S. $100-500 per hectare. However, through technologies such as remote sensing, drones, and in the near- future, hyperspectral imagery, higher quality data for carbon quantification will occur.

A working business model of NBS is Soil Capital which promotes regenerative agriculture. It would be useful to include soil-based projects into a robust rating system. It would enable the flow of funds through venture capital and its portfolio management.

Soil Capital Case Study: Providing farmers with the necessary incentives

Soil Capital enables farmers to get paid for improvements in their carbon profile, thereby helping them to adopt climate-smart farming – A model with the potential to impact millions of hectares and livelihoods on global scale

Farmers who join Soil Capital Carbon provide their operational data to the company and receive a peer-benchmarked analysis of their farm, from an economic, soil health and greenhouse-gas perspectives. This enables them to get a better understanding of their own operation, with clarity on the link between operational drivers (soil disturbance, fertiliser and agrochemical applications, crop rotations, etc.) and their impact on profitability and the environment.

This understanding is reinforced by peer benchmarking, where farmers can understand the approach of other comparable farmers, flagging opportunities for savings and improvement within their own operation.

Soil Capital Carbon then enables them to generate third-party verified ISO-compliant carbon certificates which are subsequently traded in the VCM, generating a new income stream for farmers. The programme is already active in France, Belgium, and the UK.

An average arable farmer with a farmed surface of 200ha can expect to make improvements to their carbon profile baseline of at least 1 metric tonne per hectare per year with some basic improvements (adopting cover crops, shifting to minimum till, using organic fertilisation). With a floor price of EUR 27.50 per certificate, this can generate more than EUR 5,000 in a first year. Since the baseline remains valid for five years, this income can grow substantially as a farmer continues to improve and Soil Capital continues to provide data-generated recommendations on how to improve.

By providing this incentive to farmers, Soil Capital is seeking to support the adoption of regenerative practices, which enable farmland to absorb large quantities of carbon from the atmosphere, while producing more nutritious food and increase profitability for farmers.

VI.3. Case study – Sylvera: An Integrated solution for market efficiency infrastructure

Sylvera verifies the impact of carbon offsets through advanced machine learning, satellite data and data analytics. The company’s key product is a ‘rating’ for nature-based carbon offsets (in a D-AAA structure analogous to an S&P or Moody’s credit rating[footnote 47].

There are well documented issues[footnote 48],[footnote 49] with current offset verification techniques which are undermining the market, even while demand grows significantly as businesses push towards net-zero, leaving buyers exposed to serious reputational risk, and undermining the climate impact of the market. Currently, the value of any offset is inextricably linked to the viability of the project that issued it, creating a significant dispersion of quality in the offset market. The uncertainty regarding where in this dispersion any single project sits renders offsets non- fungible, undermining the liquidity and expansion of the voluntary carbon markets.

Sylvera uses advanced machine learning (ML) techniques applied to a diverse set of Earth Observation (EO) data (e.g. multispectral, LiDAR and SAR), to offer precision, frequency, and reliability of nature-based offset monitoring. For example, it can identify negative occurrences such as fire or illegal deforestation within weeks, allowing for market correction (whereas such occurrences can currently remain undetected for 3-5 years, and are often not detected at all). The data can also be used to identify projects that have outperformed their goals and are thus more attractive to purchasers.

Table (Figure 4). The Sylvera Carbon Offset Ratings: indicative of the likelihood that the claimed carbon impact of a project is a true representation of their real impact.

Made up of Accounting (offset performance in the project area) and Impact Score (climate benefits and permanence of carbon emissions reductions). Source: Sylvera.

| Impact Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accounting | 5* | 4* | 3* | 2* | 1* | |

| >150 | AAA | AAA | AA | BB | B | |

| >125 | AAA | AA | AA | BB | B | |

| >100 | AA | AA | A | B | C | |

| >90 | AA | A | BBB | B | C | |

| >80 | A | BBB | BB | B | C | |

| >70 | BBB | BB | B | B | C | |

| >60 | BB | B | B | C | D | |

| >50 | B | B | C | D | D | |

| >40 | B | C | D | D | D | |

| >30 | C | D | D | D | D | |

| >20 | D | D | D | D | D | |

| >0 | D | D | D | D | D |

The use of geospatial data allows Sylvera to provide ‘whole of project’ data (as opposed to relying on current sampling-based monitoring)[footnote 50]. Furthermore, generalisations in the industry standard quantification of the key carbon parameter, ‘Above Ground Biomass’ (AGB), pose a further threat to offset accuracy. Sylvera has recently secured a $2 million research contract to collaborate with academics from UCLA, NASA-JPL and UCL to combat this by developing advanced, state-of-the-art AGB measurements that reduce error in machine learning (ML) AGB inference.

Using machine learning capabilities combined with data analytics, Sylvera’s data products are similar to those produced by S&P for corporate debt but applied to VCM. Sylvera ratings encompass: (i) the historical performance of the project (i.e. do the facts on the ground reflect the project’s claims), (ii) the additionality claim of the project (i.e. is the baseline scenario set out by the project realistic), (iii) the permanence risk of the project (i.e. how likely is it that carbon will be stored within a geologically significant time period), and (iv) the co-benefits contribution of the project (i.e. community and biodiversity contributions to the UN SDGs). These aspects flow up to the overall Sylvera Rating that allows projects to be tranched by overall quality, thus driving fungibility in the instruments.

Sylvera’s data has the potential to function as the ‘missing link’ between the voluntary carbon markets, voluntary exchanges, corporate purchasers, and asset managers. By providing data allowing projects to be ranked by quality, there is an opportunity to facilitate ‘quality’ definitions for this emerging market which would allow exchanges to curate liquid pools of high- quality offsets. This can in turn facilitate the emergence of a direct feedback loop between price and quality and the creation of derivative instruments (for example the forward delivery of x tonnes of AAA rated credits). It also raises the possibility of a unified ‘net zero’ accounting standard, with carbon footprints reconciled with offsets meeting a minimum quality threshold rating. This would give asset managers the ability to determine which portfolio companies have achieved carbon neutrality.

VII. Part three: Accounting – The new frontier in voluntary carbon markets

Ongoing voluntary regulatory reforms in the UK/U.S./ASEAN for corporate engagement in climate change aim to improve corporate environmental strategy and transparency. However, the lack of a harmonized financial reporting framework for emission allowances and voluntary offsets challenges the scale of financing from companies, venture capital and institutional investors.

Carbon accounting and voluntary carbon trading

From an accounting perspective, VCMs raise a plethora of valuation, measurement, and financial reporting considerations, many of which will need to be addressed by professional accountants, standard setters, regulators, and academics as carbon trading markets emerge worldwide. Whilst there is some discourse on how best to report the income statement (profit and loss) effects of carbon trading, there has been no discourse on how to value the underlying assets that produce or use carbon credits on the balance sheet. Although the reliability of the valuations of assets and liabilities has often been questioned, the relevance of developing frameworks for unified carbon accounting and disclosure have not been adequately addressed by policymakers.

The current discourse in accounting is largely focused on when revenue or expenses from carbon emission credits should be recognized. There are various accounting methods applicable to carbon offsets under the international and U.S. GAAP, the clear accounting rules. The different methods and treatments become clearer when framed in terms of a tangible (non-current) asset, in line with the IASB definition of an asset. Applying this treatment to an intangible environmental asset such as a tree (i.e., its ability to generate carbon credits in the future by sequestering carbon via growth) suggests that the asset would be a very different asset to the inventory of credits produced by already reducing emissions. It is here that a shift to a conventional accounting treatment is necessary.

Due to the wide-ranging use of financial reports by multiple stakeholders, policy makers need to consider the following aspects of carbon accounting: (1) valuation and reporting of carbon credits; (2) valuation and reporting of the intangible assets capable of creating carbon credits; and (3) reporting on organizational progress towards environmental and social responsibilities.

There has been no specific discourse to date regarding the valuation of the assets (and liabilities) capable of producing (and using) the credits that underpin a carbon trading market. However, by considering the first issue, i.e., the valuation and reporting of carbon offsets, careful considerations and wider implications need to be addressed. We highlight three main accounting implications: (1) How should the carbon credit be valued at the point of purchase, and when should they be reported in the income statement? (2) How should the liability be valued over time and when should it be reported in the income statement? and (3) How should the liability be recorded?

There has been a common consensus within the accounting profession that once carbon credit permits are issued, purchased, or created, a company should recognize them as a new asset on the balance sheet (akin to inventory) [footnote 51], [footnote 52]. When actual emissions occur, a liability should be recognized and changes in the market price of permits (i.e., gains and losses on credits) should be recognized in the income statement. Currently, a tangible asset (e.g., a power plant or forest) that generates the carbon credit is given a balance sheet value, but the related intangible asset or liability, i.e., the carbon sequestration or emissions capability of such an asset is not. Accordingly, if a company records the value of the tangible, it should record the value of the related intangible as well. For such valuations, outside consultants such as environmental scientists and biologists are needed for accounting measurements.

Carbon assets can quickly transform into carbon emitting liabilities in the event of intentional (deforestation) or unintentional (fire hazard) destruction. Therefore, scientific metrics valuing carbon sequestration capabilities must simultaneously capture their carbon emission capabilities. If an asset is only a ‘cash generating operational asset’ then it could be recorded under the current GAAP. However, the intangible asset (or liability) must be recorded as an environmental capability. In order to assess direct and indirect cash flow impacts of carbon assets, the entire supply chain and pass-through pricing to consumers requires review.

A representative carbon accounting system must be based on measurement that is materially accurate, consistent across treatment of transactions, timely, and incorporates high quality data while capturing uncertainty. However, achieving these goals is difficult because current carbon accounting efforts and regulations are spread across organizational fields- each prioritizing different goals. When quantifying and measuring “carbon” in our accounting system, we are in fact only using a proxy for actual GHG emissions. The trade in the proxy of carbon might not always match up with the tons of GHGs emitted.

Today, the global voluntary carbon market is unregulated and lacks transparency. Accountants, auditors, and users of financial statements expect a standardized system for carbon accounting measures and financial disclosure. This will lead to greater integrity of carbon markets through uniformity and quality transparency, spurring investor confidence.

Carbon financial disclosure – the UK/ U.S. and ASEAN

The Paris Agreement established the Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF) for promoting transparency and tracking progress on climate actions taken by countries (Article 13). However, this framework is very broad and does not address issues surrounding carbon accounting, financial reporting, and high-quality information.

Presenting high-quality carbon-related disclosures to stakeholders implies an integration of (a) climate change into business strategy, (b) an effective system of corporate governance that addresses climate change, and (c) external assurance and verification to enhance the credibility of firms’ disclosures[footnote 53]. If a transaction is material to the business, investors generally expect companies to consider and report its impact within financial statements, including aspects which involve future estimations[footnote 54].

In response to market calls for a financial disclosure framework, several regulatory actions have been taken worldwide. The UK has responded by conducting a series of thematic reviews through the Financial Reporting Council (FRC)55. Throughout 2020, the FRC has undertaken these thematic reviews of climate-related considerations by boards, companies, auditors, professional associations, and investors across different sectors. The reports offer recommendations and guidance that can be voluntarily adopted by companies. FRC Climate Thematic56, released November 2020, reported that an increasing number of companies are providing only narrative reporting on climate-related issues. The FRC also identified areas of potential non-compliance with the requirements of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

Although there are no standalone IFRS or U.S. GAAP which addresses climate change specifically, the requirements of IFRS standards provide a clear framework for incorporating the risks of climate change into companies’ financial reporting. These apply to measurement uncertainty associated with forward-looking assumptions and estimates, and the related disclosures. Potential financial implications arising from climate-related risks may include accounting issues related to: asset impairment, including goodwill; changes in the fair valuation of assets; effects on impairment calculations because of increased costs or reduced demand; and changes in expected credit losses for loans and other financial assets.

The UK government published voluntary guidelines for measuring and reporting of GHG emissions to encourage companies to reduce their climate change impact57. The UK Financial Stability Board (FSB) has also targeted high quality disclosure for carbon costs and emissions through creating of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) in 2015 in order to develop consistent climate-related financial disclosures for use by companies, banks, and investors. The European Commission incorporated the TCFD recommendations into its Guidelines on Reporting Climate-Related Information to support companies in disclosing climate-related information under the European Union’s reporting requirements. Within the scope of IFRS, IASB has also referred to the importance of the TCFD.

Adoption of the TCFD framework by several ASEAN countries is likely to contribute to enhancing voluntary carbon trading and promoting transparency in ASEAN for several reasons: including a harmonization of accounting treatments, unifying reporting practices under the TCFD and the globalization of carbon markets now on the horizon. Going forward, it will be important to bring more standardization to reporting requirements across different countries and jurisdictions including ASEAN, to minimize the burden for reporting companies and maximize the value of disclosure for investors.

Under the UK’s Presidency of COP26, future policy recommendations can assist in engaging global policy makers and ASEAN member states to deliver strong regulatory actions for enhancing carbon accounting and promoting harmonized practices for financial reporting. Disclosure and high-quality data for carbon emissions and credits, costs and revenues, including creating voluntary trading platforms (e.g., Carbon TradeXchange), should be part of the green recovery and transition plans by policy makers during COP26 aiming to offer nature- based solutions, adaptation and resilience in addition to accelerating the clean energy transition in the region.

Implications and recommendations

It is now time for entities in the industry to consider the cash flow and share prices impacts of reporting on emissions. Policy makers need to invest in improving the consistency within these complex carbon accounting regimes. Carbon accounting standards must provide consistent guidance for the monitoring, reporting and verification of the actual carbon sequestration or reductions in all relevant carbon pools, aiming to ensure that the effects are real, permanent, and measurable. This includes the identification of geographical project boundaries, baseline scenarios, additionality, leakage, and permanence. A robust carbon accounting system will offer ASEAN countries an opportunity to influence and scale the evolution of new and emerging carbon markets.

A way to provide the Transparency required in the VCM, Sylvera’s data supports the liquidity of carbon exchanges such as AirCarbon exchange or Carbon TradeXchange by providing the confidence and trust required for investors to transact without the need for the currently costly, slow and ineffective due diligence performed by market participants. Furthermore, by rendering assets in the same ‘quality buckets’ (i.e., AAA buckets, AA buckets etc.) effectively fungible, Sylvera facilitates the production of standard/reference contracts grouped by quality. This allows for the emergence of an explicit relationship between price and quality, and the creation of forward contracts and further price discovering - supporting the financing of future projects. Furthermore, should exchanges wish to ensure a minimum quality of offset on their platform, Sylvera’s data can be used for the curation of listed projects.

AirCarbon Exchange case study

AirCarbon Exchange commoditises verified carbon credits through securitised blockchain tokens.

AirCarbon Exchange launched in 2019, initially basing its distributed ledger technology (DLT) exchange around the aviation industry, which has clear global cross-border carbon footprint calculation and reporting (CORSIA). (ref) AirCarbon sees carbon offsets as an investible asset and is designed to resolve issues including 1) allowing fungible allowances and baskets of assets through a tokenised system, 2) ensuring minimum commissions so 98.5% of financed credits benefit project developers, 3) using DLT to minimise settlement risk and maximise price and transaction transparency. The bid/offer exchange is similar to a commodities trading exchange, creating price transparency at a global scale and allowing participants to Mark to Market the value of carbon in their portfolio.

AirCarbon has four categories of tokens targeting (i) aviation aligned CORSIA credits, (ii) NBS (iii) ESG and (iv) renewable energy. The Global Nature Token specifically covers wetlands, grasslands, forestry and agricultural projects, and is working with project developers exploring soil-based solutions. AirCarbon has seen heightened demand recently reflected through higher prices and expects this will evolve to the point where price will differentiate quality and demand for specific types of carbon.

The platform trades in US dollars, similar to many other ASEAN regional soft commodity products such as palm oil and uses a digital warehouse which enables secondary market trading and allows investors to easily manage the carbon assets within their portfolio. AirCarbon are considering building up a forward market, which largely untested but has demand from buyers looking to lock-in supply. This is expected to exponentially drive monthly trading volume into the millions.

The digital exchange is live with clients across 29 countries, with year to date nearly 3.2mm tCO2e onboarded and 2.26 million tC02e traded, with >62% of client volume coming from Singapore/SEA, and >55% of projects originating from Australia. Onboarding of project developers across regions will start to include developers from Malaysia and Singapore and buy-side entities are already purchasing credits to reach net-zero targets and ESG compliance.

Table 3. Source: Air Carbon

| Token Type | YTD Trading Volume | Average Prices 2021 | Expected Prices 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| (USD/tCO2e) | (USD/tCO2e) | ||

| CET– Corsia Eligible Aviation Token | 509,000 | 2.6 | 5.5 |

| RET – Renewable Energy Token | 40,000 | 1.25 | 2.3 |

| GNT – Global Nature Token | 32,000 | 4.3 | 6.3 |

| ESG – ESG Token | 19,000 | 5.1 | 6.2 |

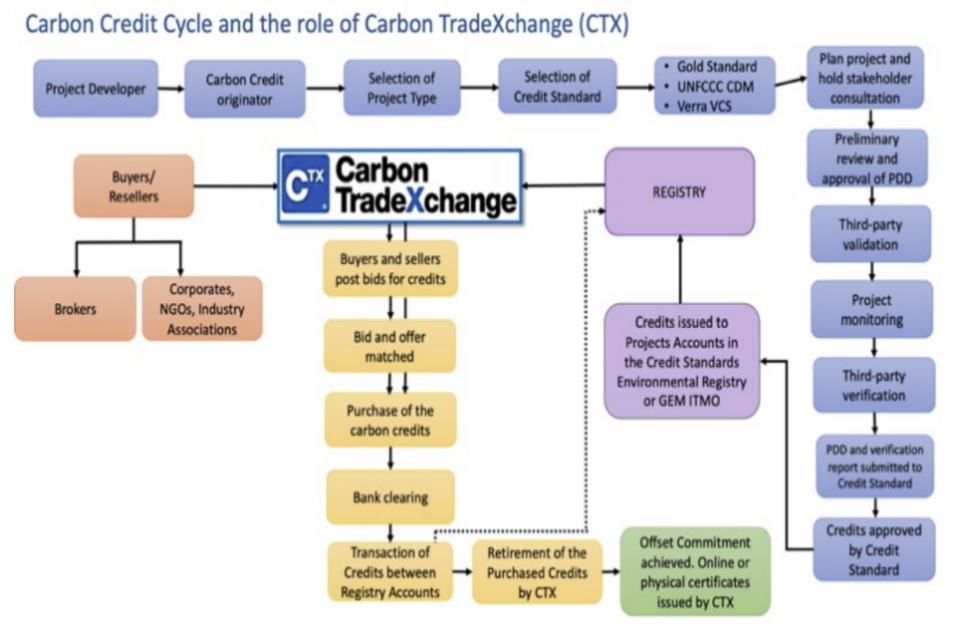

Carbon TradeXchange Case Study

Carbon Trade Exchange (CTX) is one of the earliest players in the global carbon market dating back to 2008. Today CTX offers a number of carbon services for certification, project development and footprint. CTX is a membership-based spot exchange with participants ranging from individual brokers to large co-operations. CTX credits are exchanged in four currencies (GBP, AUD, USD, EUR) at spot foreign exchange rates.

Buyers can purchase and retire credits in lots of 100 tonnes of CO2e with a 2% transaction fee and support a variety of diverse global projects including Mongolian communities who use offset proceeds to fund microfinance initiatives for energy efficient cookstoves and insulation. Sellers set the price and can access global buyers without needing direct interaction, they can also delist credits at any time but there is a 5% seller transaction fee.

To date CTX have traded over 100 million tonnes of C02e offsets, and in April alone over 61 million credits were exchanged, 85% of them being Verra VCS certified. The second largest project originating region is Asia/ Oceania. Buyers can compare projects by SDG outcomes or alignment to their businesses (aviation, chemicals, waste handling or forestry).

Figure 5. Carbon Credit Cycle and the role of Carbon TradeXchange (CTX).

Figure 5 illustrates Carbon Credit Cycle and the role of Carbon TradeXchange (CTX)

Table (Figure 6). CTX April 2021 Project Volume. Source: Carbon TradeXchange

| CTX April 2021 Project Volume | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Continent | Verra VCS | Gold Standard | UNFCCC CDM |

| Africa | 10 | 13 | 3 |

| Asia/Oceania | 27 | 36 | 27 |

| Europe | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| North America | 11 | 1 | 5 |

| South America | 40 | 8 | 14 |

VIII. Summary and conclusions

1. While only making up a comparatively small share of the total value of the global carbon market today, VCMs are growing fast, with demand for high-quality credits rapidly increasing. With its richness in biodiversity, forests, and renewable energy sources able to generate a large amount of carbon offsets and ITMOs, ASEAN has enormous potential for the establishment of both voluntary and compliance markets.

2. Accountants, auditors, and users of financial statements expect a standardized system for carbon accounting measures and financial disclosure. This will lead to greater integrity of VCMs through uniformity and transparency, spurring investor confidence.

3. Sound methodologies must be developed for selecting offsets, ensuring the integrity of net- zero financial products, and due diligence standardization to monitor the effectiveness of nature-based projects. Sylvera’s data supports the liquidity of carbon exchanges.

4. A level playing field for valuation and reporting of carbon offsets should be set up. We highlight three main accounting questions for approaching this:

(1) How should carbon credits be valued at the point of purchase, and when should they be reported in the income statement? (2) How should the liability be valued over time, and when should it be reported in the income statement? and (3) How should the liability be recorded?

5. A representative carbon accounting system must be based on measurement that is materially accurate, consistent across treatment of transactions, timely, and incorporates high quality data while capturing uncertainty. This would allow a sound risk management for de-risking facilities and investors’ assessment of risks and returns.

6. Carbon credits should be treated as financial instruments to mitigate climate finance- related risks. There is a valuation risk, and a price risk linked to macroeconomic factors and geopolitical uncertainty —secondly, quantity risks due to changes in the availability of carbon offsets and regulatory risks have arisen due to changes in public policies.

7. Carbon offsets should be tackled by looking at market efficiency and properly defining high-quality and trusted carbon credits through a shared taxonomy. A robust regulatory framework is needed for VCMs but should not be overly burdensome, while also considering the threat of oligopolies which dominate the market. Financial centres should promote transparency within this market.

8. There is an opportunity for late-stage venture capital and early growth private equity investment funds. This can enable impact investment funds for projects linked to regenerative agriculture and other NBS to foster sustainable economic growth through carbon offsets. There is an opportunity for institutional investors as anchor investors in VCM platforms.

9. Development finance institutions and agencies can provide early-stage financing and risk mitigation facilities, as well as take equity stakes as cornerstone investors in VCM platforms, implementing policy actions, and mitigating political and regulatory risks in ASEAN

IX. Glossary

| ASEAN | Association of South East Asian Nations |

| CIFOR | Centre for International Forestry Research |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide gas |

| COP, COP26 | Conference of Parties, 26th United Nations Climate Change Conference annual meeting to be held in Glasgow, November 2021 |

| CORSIA | Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation |

| DLT | Distributed Ledger Technology |

| ERPA | Emissions Reduction Purchase Agreement |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, Governance |

| EU ETS | European Union Emissions Trading Scheme |

| FCPF | Forest Carbon Partnership Facility |

| FRC | Financial Reporting Council |

| GAAP | Generally Accepted Accounting Principles |

| GHG | Greenhouse gases |

| IASB | International Accounting Standards Board |

| IFRS | International Financial Reporting Standards |

| ITMO | Internationally transferred mitigation outcomes |

| IUCN | International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| MtCO2e | Million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions |

| NBS | Nature-based solutions |