UK internal market (HTML page)

Updated 9 September 2020

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

By Command of Her Majesty

July 2020

CP 278

Foreword

Alok Sharma

For centuries, the UK’s Internal Market has been the bedrock of our shared prosperity, with people, products, ideas and investment moving seamlessly between our nations. As a Union, we are greater than the sum of our parts.

Today, we face unprecedented economic challenges recovering from the impact of coronavirus (COVID-19), which has threatened our lives, livelihoods and communities. As we move through the pandemic and into the recovery phase, we must ensure that our Internal Market, which supports countless jobs and livelihoods across our country thrives.

In addition to the enormous task of recovery, from 1 January 2021, hundreds of powers previously exercised at EU level will flow directly to the UK government and the devolved administrations in Edinburgh, Cardiff, and Belfast. Devolved administrations will have unprecedented regulatory freedom within new UK frameworks, allowing them to benefit from opportunities to innovate. To allow each home nation to take full advantage of these new opportunities, and ensure businesses can continue to trade freely across the UK as they do now, we are consulting on legislating for a UK Internal Market.

Northern Ireland sells more to the rest of the UK than to all EU member states combined. Scotland sells more to the rest of the UK than to the rest of the world put together. And in some parts of Wales, a quarter of workers commute in from England on a daily basis.

Under the plans in this white paper, the UK will continue to operate as a coherent Internal Market. A Market Access Commitment will guarantee UK companies can trade unhindered in every part of the United Kingdom – ensuring the continued prosperity and wellbeing of people and businesses across all 4 nations. At the same time, we will maintain our high standards for consumers and workers.

This will give business certainty. If a baker sells bread in both Glasgow and Carlisle, they will not need to create different packaging because they are selling between Scotland and England. Likewise, engineering firms in Scotland using parts made in Wales will know that the parts are compliant with regulations across other home nations.

By enshrining the principle of mutual recognition into law, our proposals will ensure regulations from one part of the UK are recognised across the country. The principle of non-discrimination will support companies trading in the UK, regardless of where in the UK they are based.

These principles will not undermine devolution, they will simply prevent any part of the UK from blocking products or services from another part while protecting devolved powers to innovate, such as introducing plastic bag minimum pricing or introducing smoking bans.

As we fire up our economic engines to recover from coronavirus, business needs stability. By protecting the integrity of the UK’s Internal Market, the proposals in this white paper will allow firms to focus on what they do best: creating jobs and opportunities for people right across our United Kingdom.

The Rt Hon Alok Sharma MP

Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

Introduction

1. The UK Internal Market has for centuries been at the heart of our economic and social prosperity as a country. It dates back to the Acts of Union of 1706 and 1707, and has been a source of unhindered and open trade across the United Kingdom – one which pulls us together as a united country and means that, as a Union, we are greater than the sum of our parts. The UK Internal Market long predates many other countries’ economic unions, and has been uniquely successful in driving forward economic prosperity across our whole country, providing businesses with the certainty that they need to grow and thrive.

2. While the Internal Market has been enshrined in British law for over 3 centuries, the UK’s accession to the then-European Economic Community in 1973 saw European law take on a more direct role in providing the legislative underpinning of our economy. European directives and regulations, along with relevant judgements from the Court of Justice, replaced British law and took on an integral role in the legislative underpinning of the Internal Market.

3. As the UK leaves the transition period, and leaves the EU’s legal order, we will need to legislate to maintain this centuries-old success story and guarantee the continued seamless functioning of the UK Internal Market. Avoiding the creation of new barriers is vital for our brilliant manufacturers, producers and service providers trading within the bounds of our nation; for our partners overseas as we seek to build ever richer trading relationships with other countries; and to secure the prosperity and the livelihoods of our people right across the United Kingdom. We will do this in a way that respects the devolution settlement, and ensures that the devolved administrations receive powers over many more policy areas than they currently hold as part of the EU, whilst ensuring that all intra-UK trade remains frictionless.

4. One of the key features of our economy is its deep integration and strong economic ties that bind the UK together. These ties constitute the UK’s Internal Market, the totality of undeniably close, and complex economic relationships between all parts of our country. Examples of such relationships are plentiful. Scotland and Northern Ireland both sell more to the rest of the UK than to all EU member states combined. Scotland itself sells more to the rest of the UK than to the rest of the world together. Maintaining this economic arrangement, and the significant benefits it brings, is even more important as we plan our joint recovery from the coronavirus global pandemic.

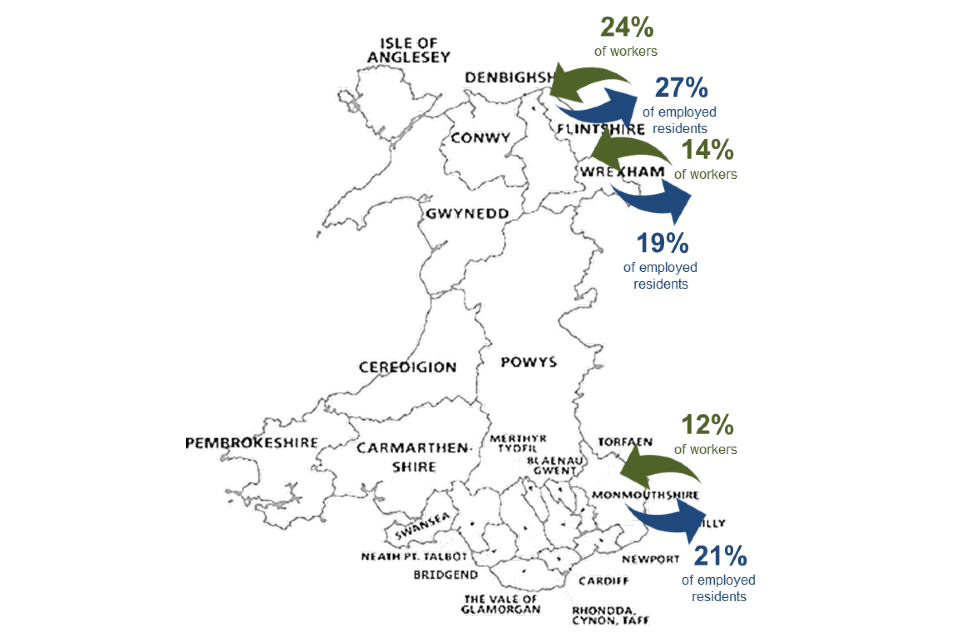

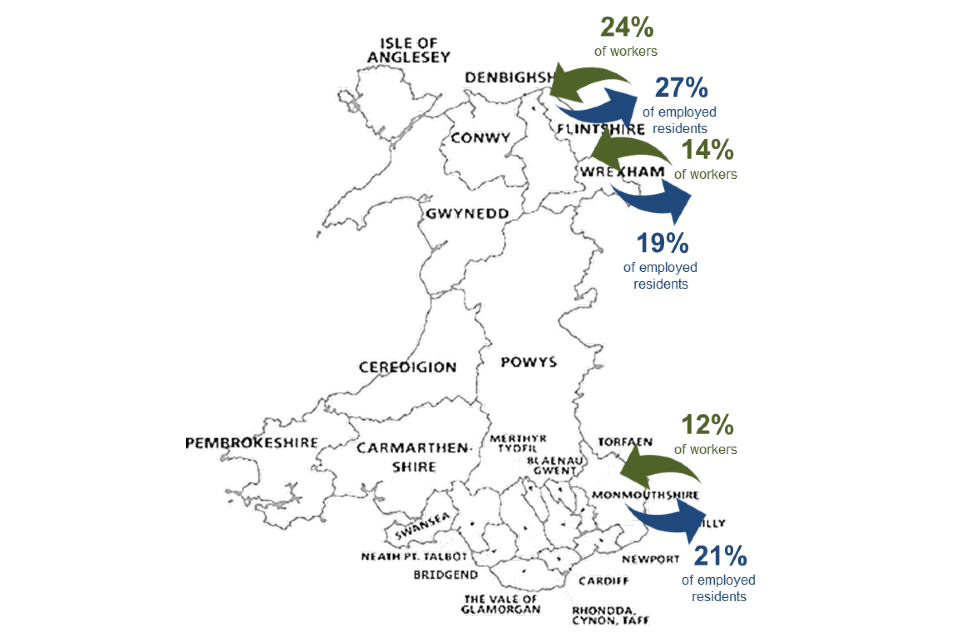

5. Analysis of census data shows that there are significant numbers of workers who commute across the UK daily – over 170,000 people commuted from one part of the UK to another in 2011. In some Welsh local authorities up to 24% of workers come from and 27% of employed residents commute to England (ONS, 2011). And finally, the UK boasts highly integrated services regulation, without instances of overt discrimination against providers from other parts of the UK. With the UK as the second largest exporter of services world-wide[footnote 1], services account for 4 out of 5 jobs nationwide through the employment of 26.7 million people[footnote 2].

6. Open markets enable frictionless trade that supports efficiency and productivity, increases business certainty and facilitates better investment decisions. They are also key in supporting our international competitiveness and maintaining our attractiveness for international investment. The UK’s integrated market allows workers to move freely across the country to work in industries and jobs most suited for their skills, boosting wages; unhindered movement across the UK is every citizen’s right. These benefits improve consumer choice and help drive reduced prices.

7. The United Kingdom has long been a trusted trading partner in the global economy. Our unyielding commitment to the rule of law and the highest standards – enshrined in law across the board, our dedication to the protection of employees and the environment, our openness to competition and the control of subsidies, or the energy and innovation of our business sector, we are a robust, open and trusted partner, right across the economy.

8. The strength of our Internal Market and our openness to trade are part of the UK’s long history as a global free trading state. With UK exports at a record high, it is important that we continue to strengthen the UK’s position as a trading nation and reassert our proud history as a beacon of enterprise and innovation. We have provided specific protection in relation to freedom of trade in our law since as far back as the Acts of Union. This economic unity, and the principle that people should have fair access and freedom within the economy wherever they are in the UK, has always been part of what makes us a strong, trusted and prosperous nation.

9. As we leave the transition period and embark on an exciting new phase as an independent trading nation, we will ensure that we continue to uphold our UK Internal Market, to protect and enhance the prosperity of our nation and livelihoods of our citizens. To secure the Internal Market for the future, the government now proposes a Market Access Commitment, which will enshrine in law 2 fundamental principles to protect the flow of goods and services in our home market: the principle of mutual recognition, and the principle of non-discrimination. This will guarantee the continued right of all UK companies to trade unhindered in every part of the UK.

10. Mutual recognition means that the rules governing the production and sale of goods and services in one part of the UK are recognised as being as good as the rules in any other part of the UK, and they should therefore present no barrier to the flow of goods and services between different regulatory systems. Non-discrimination is already relevant to our Internal Market and will in the future mean that it is not possible for one regulatory system to introduce rules specifically discriminating against goods or services from another. These principles underpin the Internal Market structures of many other countries, including Australia and Switzerland.

11. A coherent approach to market access will drive efficient supply chains and opportunities for business growth and ensure fair price distribution for consumers. This will create business certainty and the clarity needed for investment decisions, also protecting consumer prices and increased choice.

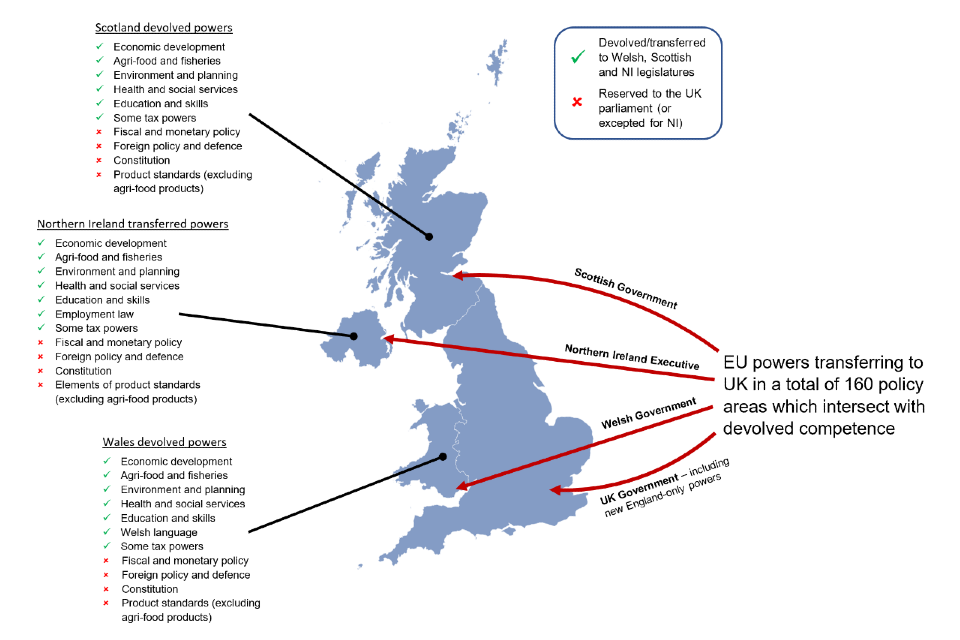

12. As well as ensuring the continued smooth functioning of our Internal Market, our approach will also give the devolved administrations unprecedented new powers to create their own laws. On January 1 2021, hundreds of powers will be transferred from Brussels to the devolved administrations. This is the single biggest transfer of powers to the devolved administrations in history, and will see new powers transferred to Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales in a total of 160 policy areas which intersect with devolved competence. Our commitment to high standards within this will be unyielding, which allows us to protect those things most important to us, like our communities and our environment, while ensuring our future prosperity. A legal commitment to reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050 is just one example of this promise.

13. The government will consider tasking an independent, advisory body to report to the UK Parliament on the functioning of the Internal Market.

14. The government continues to work with the devolved administrations on the development of Common Frameworks, which will allow a common approach to continue in many areas after the end of the transition period. There has been significant progress made on Common Frameworks, but the Scottish Government’s decision to withdraw from our Internal Market workstream in March 2019 has impeded our collective approach to ensuring the continued smooth functioning of UK trade, and without the certainty we are now giving to businesses with this approach, would risk creating disruption for citizens in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and England.

15. As part of our overall approach to the Internal Market and our future trade with partners across the globe, the government is also clear that it needs a single, fair subsidy control regime for the United Kingdom. As such, the government will seek to expressly provide that subsidy control is reserved (or excepted in Northern Ireland) and therefore a matter for the UK Parliament.

16. The UK is a unitary state with powerful devolved legislatures, as well as increasing devolution across England. The Scottish Parliament, the Senedd Cymru/Welsh Parliament, and the Northern Ireland Assembly are powerful democratic institutions acting within a broad set of competences. Each reflects the unique history of that part of the UK, and their history within the Union of the United Kingdom. This is a history to be celebrated and the government’s approach set out here will ensure that devolution continues to work well for all citizens.

General information

Why we are consulting

The consultation seeks the views of businesses, academics, consumer groups and trade unions on the policy options set out in this white paper through proposals to enshrine in law 2 principles to protect the flow of goods and services in the UK’s Internal Market: the principle of mutual recognition, and the principle of non-discrimination.

Consultation details

Issued: 16 July 2020

Respond by: 13 August 2020

Enquiries to: UKinternalmarket@beis.gov.uk

Consultation reference: UK Internal Market

Audiences: Seeks the views of UK businesses, academics, consumer groups and trade unions.

Territorial extent: The whole UK

How to respond

Respond online at: https://beisgovuk.citizenspace.com/trade/uk-internal-market

When responding, please state whether you are responding as an individual or representing the views of an organisation.

Your response will be most useful if it is framed in direct response to the questions posed, though further comments and evidence are also welcome.

Confidentiality and data protection

Information you provide in response to this consultation, including personal information, may be disclosed in accordance with UK legislation (the Freedom of Information Act 2000, the Data Protection Act 2018 and the Environmental Information Regulations 2004).

If you want the information that you provide to be treated as confidential please tell us, but be aware that we cannot guarantee confidentiality in all circumstances. An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not be regarded by us as a confidentiality request.

We will process your personal data in accordance with all applicable data protection laws. See our privacy policy.

We will summarise all responses and publish this summary on GOV.UK. The summary will include a list of names or organisations that responded, but not people’s personal names, addresses or other contact details.

Quality assurance

This consultation has been carried out in accordance with the government’s consultation principles.

If you have any complaints about the way this consultation has been conducted, please email: beis.bru@beis.gov.uk.

Executive summary

Setting the scene: The history of our Internal Market

1. The strength of the UK Internal Market is drawn from the success of our Union, our shared resources, and the ingenuity and capabilities of our people. Centuries before we joined the European Union, the UK’s Internal Market received its own articulation through the Acts of Union, guaranteeing basic economic freedoms to all British citizens. Since 1973, these age-old rules were replaced by European law. Decades later, the British people voted to leave the European Union. As EU laws cease to apply, we once again gain the opportunity to articulate our centuries-old rules of the Internal Market, drawing on the laws that constitute an integral part of our shared British history.

2. The Union was created in 1707 when Scotland and England and Wales became part of the Kingdom of Great Britain and the Union grew further when the United Kingdom was established in 1801.

3. The Union delivered new economic opportunities for people all over the new country: drovers guided their livestock from the hills of Wales to market in London. Coal and iron industries saw Wales at the heart of the industrial revolution, spawning ever-developing industries and supply chains in areas like copper-smelting and tin plate production which cemented Wales’s role as a powerhouse of industry in Victorian Britain. Wales’s strong trading instincts are still evident today. Being part of a strong and united Internal Market remains as important for Wales today as it has ever been.

4. One of the major benefits of the 1707 Union for Scotland was gaining access to England’s markets both here and overseas primarily, at the time, for Scottish cattle and linen. The Act of Union saw immediate boosts in Scottish trade, through increased links with the Baltic and elsewhere for Scottish merchants. The echoes of that growth resound through to the present day – modern Scottish towns like Crieff and Falkirk originally thrived as popular merchant markets following the increase in trade. By the 1720s, the Glasgow and Clyde ports were growing as a result of increased trade made possible by the Union. When we look from the vantage point of today – where the rest of the UK is Scotland’s biggest trading partner by far – the economic advantages of the Union have more than stood the test of time.

5. Northern Ireland, too, has benefitted from a close economic relationship with the rest of the UK. During the 19th Century, Belfast emerged as a major industrial city, famous for its linen and shipbuilding industries. As the first part of the UK to experience devolution, the economic importance of the Union to Northern Ireland was respected. While the Belfast (Good Friday) Agreement acknowledged the potential for North-South cooperation, the legislation underpinning the devolution settlement of 1998 continues to offer protection for the single market in goods and services within the United Kingdom. Great Britain remains the most valuable market for Northern Ireland goods.

Part 1: Our Internal Market after the transition period

6. In January 2020 the UK left the European Union. Following the end of the transition period this year, the way we regulate labour, capital, goods and services in the UK will no longer be decided by the EU. Instead, we in the UK will be able to regulate our trade in goods and services in a tailored manner, specifically designed to benefit our businesses, workers and consumers, while maintaining our high regulatory standards.

7. This ability to decide how best to manage our trade in goods and services in all parts of our country will be instrumental in preserving the coherence of our shared Internal Market – ie the total set of trading relationships that exist across the UK. At this historic moment, we will be able to give business certainty and best facilitate the transfer of new powers to the devolved administrations by upholding the rules that govern our internal economy.

8. At the end of this year, new powers will transfer from the EU to the UK government and devolved administrations, enhancing different levels of government’s ability to regulate in accordance with the needs of their local populations, in areas such as agriculture and food standards, amongst others. This in turn, will provide a pivotal moment for the UK as a country to evolve its own bespoke regulatory system with certainty, which is so important for the UK’s businesses, citizens and economy as we recover from the impact of coronavirus.

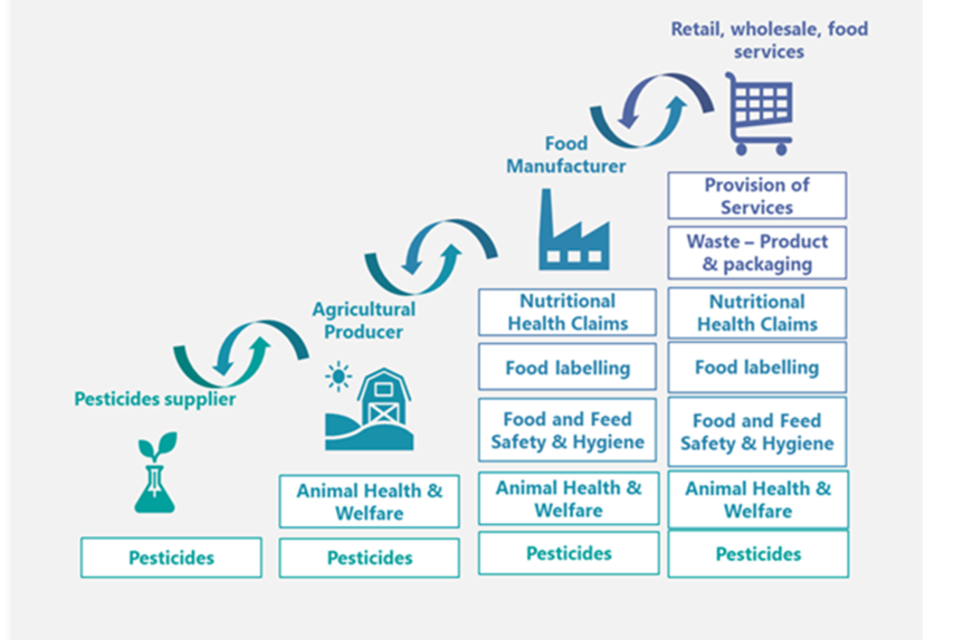

Figure 1. Example areas of devolved competence and volume of new powers transferring to the devolved administrations [footnote 3]

Figure 1

9. Maintaining frictionless trade across the UK will be essential as we look to take advantage of the opportunities presented by leaving the EU, including the ability to rapidly and flexibly develop regulation that works best for citizens in every part of the UK. The UK government is not just committed to retaining high regulatory standards (such as animal welfare) – but exceeding the various protections offered by the EU.

10. Our country has a long history of having a seamless and highly integrated Internal Market. Guaranteed access to the UK economy across all parts of the UK remains invaluable to the welfare and prosperity of its citizens, and the free flow of goods and services is one of the fundamental economic rights that should be preserved for all.

11. We will, as the influence of the EU Single Market laws fall away, need to act to enhance our existing architecture to strengthen our Internal Market, enshrining in law new mechanisms that ensure we can trade freely across all parts of the UK.

This white paper

12. In this paper, the government presents a UK-wide approach to ensure that the seamless trade across the UK’s Internal Market is maintained by providing a Market Access Commitment to all businesses and citizens across the UK. Through this consultation, we aim to ensure that the voice of the business and wider stakeholder community is represented within the detailed policy design.

13. The government aims to implement a system that works alongside new devolved powers while guaranteeing consistency and clarity for business and citizens. We want to do this through implementing new legislation to enshrine a fundamental Market Access Commitment in law, minimising domestic trade costs, business uncertainty and bureaucracy. We want to legislate for this fundamental commitment by the end of 2020, as we exit the transition period, to ensure the protection of all UK business and consumers from Day 1.

14. Responses to the white paper questions will inform the government’s approach to the legislation.

Maintaining market access with regulatory difference

15. As mentioned in the opening statement of this white paper, one of the key features of our economy is its deep integration. This is evidenced not only through Scotland’s and Northern Ireland’s overwhelming reliance on domestic UK trade, or the hundreds of thousands of commuters crossing from one UK nation to another each year. Our tourism industry provides a similarly compelling example, in 2019, Great Britain’s residents took a total of 122.8m overnight trips to destinations in England, Scotland, or Wales. This amounted to 371.8m nights and £24.7bn was spent during these trips[footnote 4].

Figure 2. Cross-region commuting between England and Welsh local authorities[footnote 5]

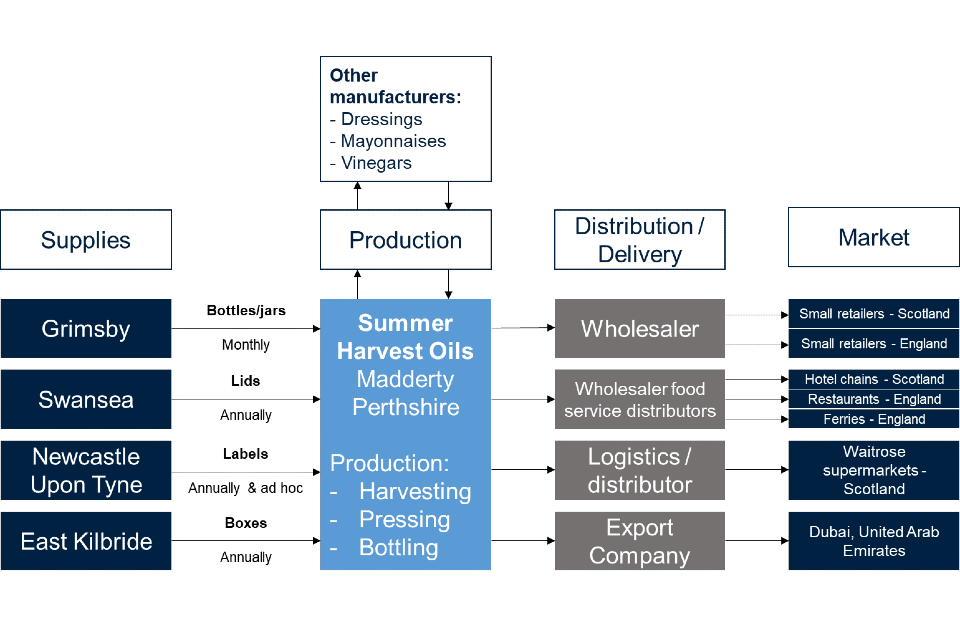

Figure 2

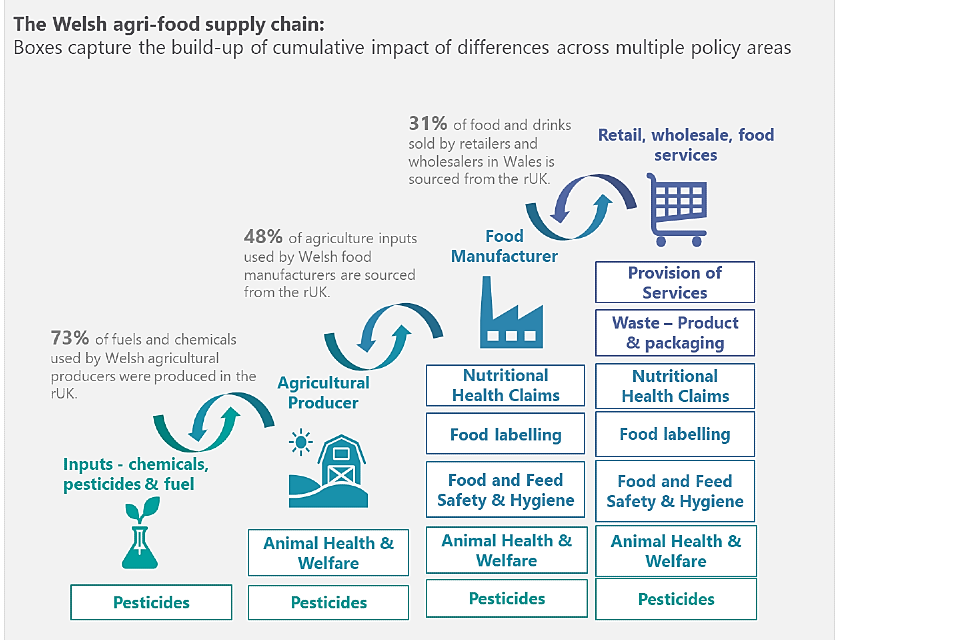

16. As the EU regulatory powers fall away, there is a danger of regulatory barriers emerging. These would bring risks not just to the wider UK economy, but also to England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland individually. Any reduction in Scottish and Welsh GDP is likely to be 4 and more than 5 times larger respectively, in comparison to the overall UK GDP loss, given their high degree of integration with the rest of the UK.

17. Without an up-to-date, coherent market structure, economic barriers could block or inhibit trade in goods across the UK, and services could be significantly and detrimentally impacted. Complexities in key sectors such as construction could arise, were differences in regulations to emerge over time. If England and Scotland diverged on their approach to building regulations or processes for obtaining construction permits, it would become significantly more difficult for construction firms to design and plan projects effectively across the UK. Moreover, different approaches to the regulation of construction professionals, such as differing qualifications for plumbers and technicians, could limit access to skilled construction workers, and make it harder for Scottish construction companies to bid for contracts in England.

18. Even in areas where specific powers are not returning, the absence of EU rules could make it easier for new barriers to arise. This could include areas of significant future economic activity, and new professions and products that play an important role in driving the UK’s scientific and technological leadership. For example, if different qualifications or other regulations on professionals working in Artificial Intelligence emerged in England and Wales, this could deter workers from qualifying for the smaller Welsh market, limiting growth and investment there. This could also increase costs for companies looking to hire such workers from across 20 the UK and reduce the UK’s global attractiveness to foreign investment in new technologies.

19. The above costs could also ultimately reach consumers, increasing prices, or decreasing choice. It is therefore clear that significant and unmanaged economic barriers across the UK could not only cause serious harm to both the interests of our business and consumers, but also threaten the prosperity of the UK economy as a whole.

Common Frameworks

20. The UK government is already engaging in a process to agree a common approach with the devolved administrations as part of its vision for the UK Internal Market. The Common Frameworks programme is the mechanism most advanced in its development to address regulatory coherence. Common Frameworks are designed to support the functioning of the Internal Market, the management of common resources and the UK’s ability to negotiate, enter into and ratify trade and other international agreements.

21. Common Frameworks aim to protect the UK Internal Market by providing high levels of regulatory coherence in specific policy areas through close collaboration with devolved administrations to manage regulation. They do this by enabling officials to work together to set and maintain high regulatory standards. However, Frameworks on their own cannot guarantee the integrity of the entire Internal Market. As they tend to be sector-specific, they do not address the totality of economic regulation or the cumulative effects of divergence, ie the consequences of regulatory difference in one sector that affects other sectors. Finally, they do not fully address the question of how best to substitute the wider EU ecosystem of institutions and treaty rights had on the UK Internal Market.

22. The UK Internal Market legislation discussed in this white paper complements Frameworks by providing a baseline level of regulatory coherence across a wider range of sectors. This means that the areas without a Common Framework will still benefit from a low-level regulatory coherence underpinning. Crucially, market coherence will be provided for issues that fall around or between individual sector-focused frameworks.

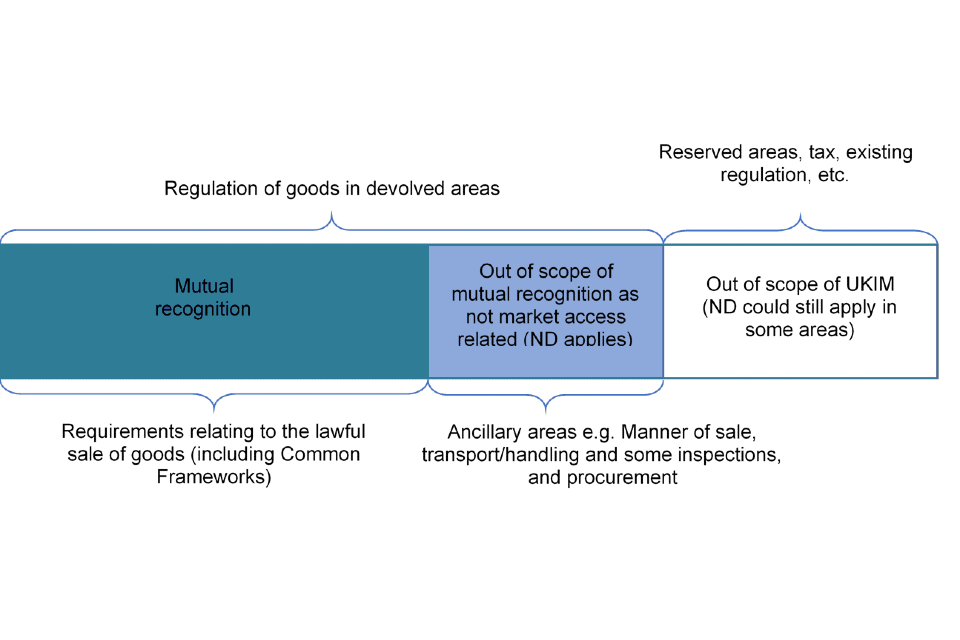

Scope

23. In order to provide UK citizens and businesses with security, the Market Access Commitment will cover the UK economy across goods and services. Reserved areas will be out of scope including, for example, fiscal and monetary policy, and intellectual property regulation. Taxation and spending, captured by the fiscal frameworks, will also not be covered. Certain social policy measures with little Internal Market impacts, and pre-existing differences and policies, will also be excluded. Ongoing monitoring will assess the impact of localised divergences, for example between Combined Authorities in England.

Key objectives

24. The government’s priority in developing these proposals is to protect opportunities for business, consumers, workers and the third sector in all parts of the UK. The government values the principle of devolution and believes that the UK’s exit from the EU offers the chance to support the devolution settlements, while maintaining the highly successful functioning of the UK Internal Market.

25. As set out above, the UK Internal Market system will therefore be driven by the following 3 overarching policy objectives:

- to continue to secure economic opportunities across the UK

- to continue competitiveness and enable citizens across the UK to be in an environment that is the best place in the world to do business

- to continue to provide for the general welfare, prosperity, and economic security of all our citizens

26. These objectives will be supplemented by the following 3 supporting aims:

- to continue frictionless trade between all parts of the UK

- to continue fair competition and prevent discrimination

- to continue to protect business, consumers and civil society by engaging them in the development of the market

27. Finally, the UK Internal Market will also follow 2 main design rules:

- foster collaboration and dialogue

- build trust with business and maintain openness

A legislative underpinning for the UK Internal Market

28. The government will seek to introduce new legislation that will commit, to all citizens and businesses, free access to the economic activity across the UK. This will ensure continued market access across the UK, delivered through the principles of mutual recognition and non-discrimination. Without such a legislative underpinning, unnecessary regulatory barriers could emerge between the different parts of the UK. Businesses need certainty and clarity to operate smoothly across the UK and encourage investment, and only this package of interventions enshrined in law can fully meet this objective. In the absence of specific Internal Market legal provision, courts faced with businesses seeking to prove their rights will lack clear guidance about governments’ intentions.

29. The government’s aim is to ensure this legislative underpinning operates on a full UK-wide basis, taking into account the obligations that apply under the Northern Ireland Protocol (our approach to which was set out in the command paper, the UK’s approach to the Northern Ireland Protocol)[footnote 6]. A central part of that approach will be legislating for full unfettered access for Northern Ireland goods to the UK market by the end of this year, reflecting Northern Ireland’s integral place in the UK’s Internal Market and customs territory.

30. These measures will preserve the integrity of the UK Internal Market on an ongoing basis. The government will look to build on precedent to ensure that we continue to have the most effective mechanisms to deliver that objective. We will also seek to ensure that there is widespread public understanding of the benefits of the UK Internal Market as an integral part of our union. In this white paper, we invite thoughts and ideas on the best way to ensure that this message is effectively communicated.

Maintaining high standards

31. The UK’s exceptionally high standards will underpin the functioning of the Internal Market, to protect consumers and workers across the economy. These high standards are neither dependent on EU membership nor on what is agreed in Free Trade Agreements we sign with other countries. They are domestic standards. In many cases, the UK either goes beyond EU standards or is the first mover to improve standards before the EU. We will maintain this world-leading position moving forward.

32. Under the government’s proposed approach, the devolved administrations would retain the right to legislate in devolved policy areas that they currently enjoy. Legislative innovation would remain a central feature – and strength – of our Union. The government is committed to ensuring that this power of innovation does not lead to any worry about a possible lowering of standards – by both working with the devolved administrations via the Common Frameworks programme and by continuing to uphold our own commitment to the highest possible standards.

33. The UK has some of the highest standards in the world on goods. The rules for non-food products, which in most cases apply across all of the UK, already mean that consumers are protected from the risks posed by dangerous or faulty goods. Examples include rules that makes sure:

- consumer electronics like mobile phones, laptops and tablets are compliant

- cosmetics do not contain dangerous ingredients

- toys do not present a choking hazard

34. The UK also has some of the most robust standards on food, with world-leading food, health and animal welfare standards. We will not lower our standards nor put the UK’s biosecurity at risk as we negotiate new trade deals. The government remains committed to promoting robust food standards nationally and internationally, to protect consumer interests, and ensure that consumers can have confidence in the food they buy. We will continue to protect human, animal and plant life and health, and the environment and continue to cooperate with stakeholders across all 4 parts of the UK via bodies such as the Trade and Agriculture Commission.

35. We remain firmly committed to upholding our standards outside the EU and the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018 will transfer existing EU food safety provisions, including existing import requirements, into the statute book. These import standards include a ban on using artificial growth hormones in domestic and imported products and set out that no products, other than potable water, are approved to decontaminate poultry carcasses. Any changes to existing food safety legislation would require new legislation to be brought before the UK Parliament and the devolved legislatures.

36. The Food Standards Agency and Food Standards Scotland will continue to ensure that all food imports comply with the UK’s high safety standards and that consumers are protected from unsafe food. Alongside this the UK will repatriate the functions of audit and inspections that are currently carried out by the European Commission to ensure that trading partners continue to meet our import conditions for food and feed safety, animal and plant health and animal welfare.

37. The UK has a proud record as a leader in health and safety in the work place, in many cases going beyond the requirements of EU law. The Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 (with parallel legislation in NI), which developed independently of the EU, introduces general duties on employers to ensure the health, safety and welfare at work of all their employees. UK businesses are more likely to have a health and safety policy, and to follow this up with formal risk assessment, compared to EU member states. We have one of the most successful health and safety records in the world, and perform consistently well compared to the EU average on key health and safety outcomes.

38. The UK has led on workers’ rights. The UK offers a year of maternity leave; the EU minimum is just 14 weeks. The UK introduced 2 weeks’ paid paternity leave in 2002; the EU has only recently legislated for this. The UK allows eligible parents to share paid leave – and so caring responsibilities – in the first year following birth or adoption; the EU does not provide for this right. The UK introduced the right to flexible working in the early 2000’s – the EU is just catching up now. This applies to all employees in the UK – the EU agreed rules last year which will offer the right to parents and carers only. The UK banned exclusivity clauses in zero hours contracts in 2015; equivalent EU rules were only agreed in 2019.

39. The UK has a world class competition regime in the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). This is independent of the EU’s standards, having adopted robust measures voluntarily in the Competition Act 1998 and the Enterprise Act 2002 – and the UK’s regime already exceeds that of the EU’s in areas. The UK is the only country in Europe whose competition authority can impose enforceable structural and behavioural remedies following a market investigation. These powers go beyond Regulation 1/2003, from which the EU derives its powers for a sectoral inquiry. The UK also has criminal sanctions for cartels and director disqualification powers which the European Commission and most member states lack.

40. The UK has a robust and progressive consumer protection regime. In recent years, the UK has been influential in resisting harmonisation of EU law that would have reduced these standards. The UK has successfully negotiated to maintain flagship protections to preserve consumer confidence in areas such as faulty goods and online ticketing platforms. Working alongside the CMA, the objectives for international policy are to build on and develop international consumer enforcement cooperation where possible. The UK was the first member state to develop a consumer protection regime for purchases of digital content, an approach that the EU has now adopted. Unlike most member states, the UK stands out in giving consumers a right to an immediate refund if a good is faulty.

41. The UK was the first major economy in the world to set a legally binding target to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions from across the economy by 2050. The UK is a global leader in the fight against climate change, and future Free Trade Agreements will not get in the way of this. Our innovative framework of carbon budgets established under the Climate Change Act 2008 ensures continued progress towards our emission reduction targets. We are seeking to increase ambition under the Paris Agreement through the process of revising Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). As incoming COP26 President in partnership with Italy, we will continue to work tirelessly with our partners to deliver the increased ambition needed to achieve the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

42. The UK has world-leading environmental standards. The Environmental Performance Index, produced jointly by Yale and Columbia Universities in collaboration with the World Economic Forum, ranked the UK in the top 10 of 180 countries in 2018. The UK has been quick to take action against single-use plastic, with a ban on the supply of plastic straws, drinks stirrers and cotton buds coming into force in October 2020, nearly a year ahead of the EU’s own timetable of July 2021. The UK’s Clean Air Strategy, published in January 2019, was praised by the World Health Organization as “an example for the rest of the world to follow”, setting out ambitious new goals to cut public exposure to particulate matter pollution based on stringent targets.

43. The UK’s environmental standards in many areas go beyond the EU’s. The UK is introducing one of the world’s strictest ivory bans to protect elephants from poaching, with our legislation adopted in December 2018 – the same year that the EU began consultations on tightening restrictions though it is yet to legislate on this issue, despite pressure from stakeholders. The UK is taking the lead in marine protection, leading the ‘30by30 initiative’ to ensure that at least 30% of the global ocean is protected by 2030 – this represents a trebling of the present target. The UK-led Global Ocean Alliance will call for this ambition to be adopted at the next Convention on Biological Diversity conference in China. The UK’s microbead ban came into effect in January 2018, a landmark step in the introduction of one of the world’s toughest bans on these harmful pieces of plastic. The EU did not move to introduce an equivalent ban until 2019.

44. In maintaining these high levels of protection, we are also building in the capability to review them so that they can keep pace with best practice and where appropriate simplify them to help businesses comply.

International trade

45. Ensuring the UK remains a coherent and integrated economy will be key to fostering all the opportunities in trade. A system that delivers across the whole of the UK will help develop and implement ambitious trade deals that can bring UK-wide benefits to businesses and citizens. It will also help make the whole UK more attractive to foreign investment and build confidence in our present and future trade partners. Helping business thrive will support UK exports, and enable companies to become more competitive, boosting the UK’s trading reputation around the world. A well-functioning Internal Market system, tailored to the interests of businesses across the UK, will therefore play a vital role in supporting our long-term global trade ambitions, ensuring the UK as a whole is capable of competing on the international stage.

Securing investment

46. The government will ensure that where towns and cities have previously been left behind, they will be able to benefit from UK-wide government initiatives such as protecting the UK Internal Market, as part of the levelling-up and coronavirus recovery agendas. This package of measures will help us deliver on our ambition to ensure our advanced economy provides benefits and access to opportunities to businesses and citizens across the UK.

47. The government will also consider which spending powers it needs to enhance the UK internal market, to help people and businesses in each nation to take advantage of it, and to further its ambition to level up every part of the UK. In exercising any such new powers, the government will provide funding fairly across the nations.

Part 2: Mutual recognition and non-discrimination

48. The proposed legislation will be based on the principles of mutual recognition and non-discrimination, and will apply across both goods and services. Alongside other elements such as Common Frameworks, these principles will ensure that the UK Internal Market works for all.

49. The fundamental aim of all mutual recognition systems is to ensure that compliance with regulation in any one territory is recognised as compliance in the other(s). For example, if a good produced in Scotland, and adhering to the Scottish labelling regulations, can be placed on the Scottish market, it can also be placed on the English and Welsh markets without the additional need to comply with English or Welsh requirements.

50. Mutual recognition will not, however, be appropriate or possible in all areas. Within a mutual recognition system there will be, ‘exclusions’. These will refer to areas outside scope when the system comes into force. This has been a feature of the UK Internal Market since 1707 (such as legal systems). Any exclusions will need to be agreed at the outset and will not generally be expected to change. If the UK government or a devolved administration introduces regulation that falls within an exclusion, then the mutual recognition system will not apply, such as in taxation and spending, existing reserved areas, or social policies with little Internal Market impact.

51. The mutual recognition system will be combined with a non-discrimination principle. This will protect businesses, workers and consumers from discrimination by ensuring that an authority must regulate in a way that avoids differential and unfavourable treatment to goods or services originating in another part of the UK to that afforded to its own goods or services. The focus of the non-discrimination principle will be on ensuring that any discriminatory barriers are addressed (eg regulating against goods from a specified nation within the UK), while mutual recognition will aim to reduce the overall regulatory burden a business might face as a result of diversity in regulation affecting goods and services. The government’s view is that direct discrimination should be prohibited; it is also seeking views on how to legislate for indirect discrimination. The 2 respective definitions of discrimination are set out in Part 2 below.

Part 3: Governance, independent advice, and monitoring

52. Intergovernmental arrangements will have to be expanded to account for Internal Market legislation and we will support these arrangements with 2 independently undertaken functions.

53. The first function will provide regular ongoing monitoring of, and reporting on, the health of the UK Internal Market as it develops. This will include monitoring the cumulative impacts across sectors or regions and horizon-scanning for emerging trends.

54. The second function will be to proactively gather business, professional, and consumer views to strengthen the evidence-base needed for independent advice and monitoring.

Part 4. Subsidy control

55. Subsidies refer to support (financial or in kind) from any level of government to selected businesses. As a result of our membership of the EU, we have been subject to EU rules on State Aid regulated by the European Commission. It is important that we continue to have a coordinated approach to the way we support businesses across the UK.

56. The UK government will work with the devolved administrations to determine how subsidies should be given in a coherent way across the UK that protects the coherence of the Internal Market, whilst ensuring the devolved administrations can continue to control their own individual spending decisions within this system. Given that the rules relating to subsidising business are an issue on which a uniform approach is key to our ability to remain a competitive economy, the government’s view is that this should be reserved (or excepted, in Northern Ireland[footnote 7]). While not covered in this paper, it is important to enable the government to legislate for a single, unified subsidy control regime, should it decide to do so.

Part 5: Conclusions

57. This will provide certainty and consistency to businesses and consumers. At a time of deep economic uncertainty due to coronavirus, providing stability will be key to encouraging investment across the Internal Market, helping to ensure the UK’s recovery is as strong and as swift as possible. This will uphold our shared prosperity as a Union and allow us to flourish as an independent nation outside of the EU.

Setting the scene: the history of our Internal Market – a story of shared prosperity

58. For centuries, the UK Internal Market has been the bedrock of our shared prosperity ever since 1707 when the Acts of Union formally united England and Wales with Scotland. The Union predates the German Zollverein, the economic unification of Italy and the economic reforms introduced after the creation of the French Republic. There can be little doubt that then – as now – the scope and scale of a wider economic base and access to a bigger Internal Market were a benefit to all parts of the United Kingdom.

59. The contemporary desire to boost and revitalise the economy post coronavirus is reflected in the original Treaties themselves. Investment in manufacturing was secured with conditions as part of the negotiation, and 15 of the 25 separate articles of the 1707 Treaty of Union dealt with economic matters. The Treaties provided for many of the essentials of the UK Internal Market, for example Articles 16 and 17 standardised how goods were to be weighed, measured and paid for. Yet at the same time, the Treaty did not fundamentally change the religious, legal or local government systems of Scotland or England and Wales.

60. The Act of Union saw immediate boosts in Scottish trade, through increased links with the Baltic and elsewhere for Scottish merchants. The echoes of that growth resound through to the present day – modern Scottish towns like Crieff and Falkirk originally thrived as popular merchant markets following the increase in trade.

61. By the 1720s, the Glasgow and Clyde ports were growing as a result of increased trade made possible by the Union. Wales also made the most of the opportunities that these expanding markets provided, both within the United Kingdom and across the globe. Drovers guided their livestock from the hills of Wales to market in London. Coal and iron industries saw Wales at the heart of the industrial revolution, spawning ever developing industries and supply chain in areas like copper-smelting and tin plate production. South Wales became synonymous with exporting coal and iron and steel. North Wales exported slate to roof buildings across the globe.

62. The Union continued to grow with the Act of Union in 1801. Northern Ireland, too, has benefitted from a close economic relationship with the rest of the UK. During the 19th Century, Belfast emerged as a major industrial city, famous for its linen and shipbuilding industries.

63. By the mid-20th century, the Internal Market connected the economies of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, with the provisions of the Acts of Union playing a key role in keeping markets open. In 1973 the United Kingdom joined the European Economic Community, and had to accept the supremacy of EC (later EU) law. Under the devolution settlements, which were introduced from 1998, it was necessary to create a system which kept the UK Internal Market open, and which was compatible with the supremacy of EU law.

64. Under the devolution settlement, the devolved legislatures and administrations cannot act incompatibly with EU law. This meant that EU laws (rather than UK law) provided the common UK-wide approaches and rules for market access. This will remain the case until the end of the transition period, which will end on 31 December 2020.

Part 1. Introduction to the Internal Market today – supporting an integrated economy

Introduction

65. The UK is a highly integrated, yet diverse economy, reflecting the historic and complex links between England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. These connections support businesses, workers and consumers, ensure the free flow of capital, labour, goods and services, and facilitate our everyday lives in a way that we take for granted.

66. Essential to the integration of the UK economy is our shared regulation, which provides economic stability and certainty to UK citizens, facilitates frictionless trade, and creates opportunities for people to shop, work and innovate across the country. This shared UK marketplace facilitates trade and investment, allows exploration of new technologies, and drives productivity and growth while benefiting consumers. It also helps professionals move across the UK with ease so that they can provide services closer to their customers and develop business in those parts of the UK that offer the best conditions.

67. Much of the recent regulation in the UK has been shaped through our membership of the EU, creating a high degree of uniformity[footnote 8]. Following the end of the transition period, powers previously exercised at EU level are flowing back to the UK government and the devolved administrations in line with the devolution settlements. Each devolved administration will therefore be gaining the ability to regulate in new areas such as agri-food, chemicals, waste and fisheries[footnote 9] (see figure 1). As a result, the UK will now have the opportunity to develop an alternative regulatory system supporting the free flow of goods and services through the whole economy.

Previous stakeholder engagement

68. The government has engaged a number of stakeholders throughout the policy development process. This engagement has included businesses and representative organisations from the many sectors and industries across the UK, as well as consumer groups and academics. The policy set out here has benefitted hugely from their insights on how the UK Internal Market contributes to the effective operation of UK businesses, and on the potential effects of the regulatory landscape on the wider economy and civil society. Input from international policy experts, from governments and academia, in other nations who have faced similar policy challenges, has also been incorporated, including from Spain, Canada, Germany and Switzerland.

69. From stakeholder engagement to date, the government is aware that businesses are anxious to avoid supply chain and logistical disruptions, which may emerge as a result of multiple parallel regulatory regimes, presenting particular challenges for SMEs. Stakeholders have consistently emphasised how the smooth operation of the UK marketplace is critical for their operations. For example, businesses in ‘just in time’ parts of UK supply chains, such as manufacturing, retail, parts, textiles, agri-food, defence and chemicals, rely on the rapid movement of goods within the UK. These businesses highlighted that delays impact the whole supply chain network through increased costs and loss of end customers. Increased costs either must be absorbed by the supply chain, challenging the operability of those businesses operating on smaller profit margins, in particular SMEs, or be passed onto consumers, with a knock-on effect on the wider economy at a time when many businesses and citizens are still struggling to recover from the impact of coronavirus. The government has drawn on this and other evidence whilst preparing its legislative proposals.

This white paper

70. The purpose of this white paper is to set out the government’s plan for the key objectives and application in UK of our Internal Market system for the whole of the UK, and to seek additional stakeholder views on some of the details of how this system should function. In the chapters that follow, we explain how the UK’s Internal Market is currently organised, including the evidence for a high level of interconnection across the UK, and the benefits this gives us all for trade. We then examine the proposed aims of the UK Internal Market system and set out its targeted scope. This includes describing the legislative underpinning for the Internal Market to provide a legal safety net to business, professionals and consumers, which cannot be provided through purely administrative channels. Finally, the white paper sets outs the government’s stance on the formal reservation of subsidy control as this power returns from the EU.

71. There are 3 annexes:

- Annex A – providing the relevant analysis and evidence on the UK Internal Market.

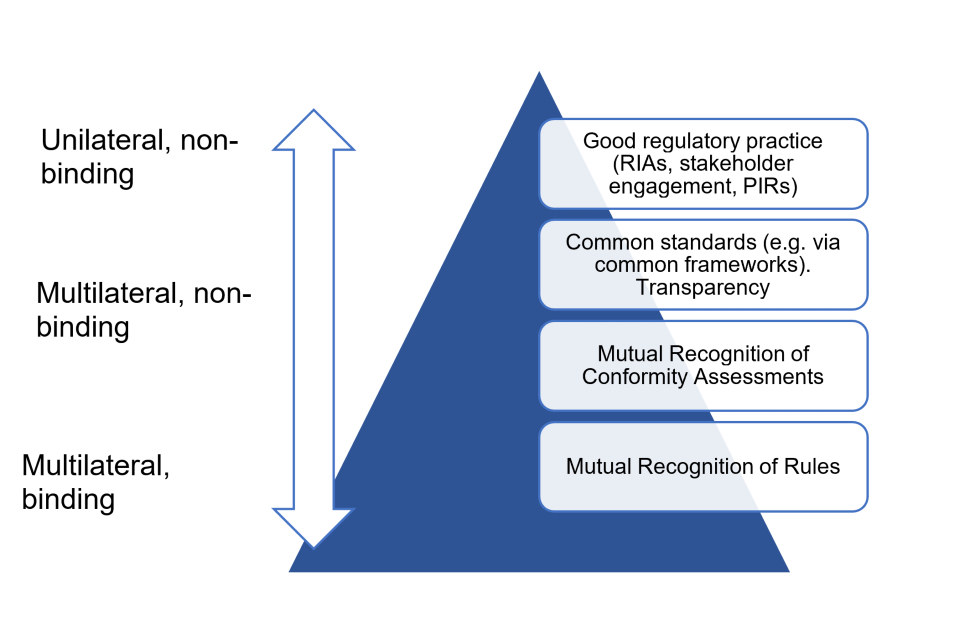

- Annex B – exploring the known international models for managing regulatory difference.

- Annex C – summarising recent and current inquiries relevant to UK Internal Market policy.

The present and the future of the UK’s Internal Market

What is the Internal Market?

72. The UK’s Internal Market is the set of rules which ensures there are no barriers to trading within the UK. Like any market, the way these relationships work is closely connected with our shared institutions and practices – including those linking up governments, business, consumers, and wider stakeholders.

How does the UK Internal Market operate currently?

73. Stakeholder engagement has been largely reflective of the data that evidences our economic integration, referred to throughout this paper. For example, a Scottish agricultural organisation stated that the UK market remains the most significant interest for Scottish agriculture and highlighted the need to ensure that the Internal Market continues to operate as an open economy. Similarly, a Welsh agricultural organisation commented that smooth cross border trade is essential for Welsh farmers.

74. Census data focused on the numbers of commuters across the UK mentioned earlier in this paper indicates a real integration rather than the presence of a dominating employer or cluster of economic activity on one side of the border. Regarding more permanent movement of people, according to the ONS, all devolved administrations are net recipients of migrants from the rest of the UK combined.

75. It is worth noting that the integration of the UK economy does not seem to be driven by geographical closeness: BEIS analysis[footnote 10] shows that even after accounting for geographic distance, whether regions have a shared border, economic size and a range of cultural factors, we see more trade within the UK compared with other regions and countries, indicating lower trade costs within the UK.

Benefits of an integrated Internal Market

76. The government’s stakeholder discussions have revealed the importance of a seamless Internal Market to allow business to develop efficient supply and distribution chains for goods. Having consistent regulation throughout the UK was seen as a way of reducing business complexity and cost and unlocking efficiencies and economies of scale, which in turn increases international competitiveness. The inverse is also true: a Scottish food manufacturer observed that, changes and additional regulatory burdens could reduce their competitiveness against businesses in the rest of the UK and potentially against EU businesses as well.

77. Recognising the greater possibilities for regulatory barriers post-transition period, stakeholders in multiple goods sectors raised concerns that regulatory barriers could increase operating costs in necessitating adaptation to multiple regulatory regimes. For example, future divergence in packaging regulation in the pursuit of differing policy ambitions was highlighted as a risk by manufacturing stakeholders, in its potential to significantly increase production and transport costs, and compromising supply chain viability. Businesses in goods supply chains across a number of sectors agreed that impacts would be felt across the business base, and particularly by SMEs. A clinical research organisation observed that changes in regulations are more burdensome for a smaller company in terms of learning, reacting and then responding. Similarly, a representative of an organisation in the construction sector raised the concern that larger businesses would be able to adapt while the SME businesses would remain unprepared.

78. The benefits for business of an integrated UK market have important implications for consumers. One consumer group highlighted that, as businesses create efficient supply chains and take advantage of greater economies of scale, consumers gain greater access to products from across the UK as well as reduced prices. A strong UK brand influences consumer confidence in product quality both domestically and abroad and can help improve the volume of UK exports. Research has shown that a ‘made in Britain’ label has a positive effect on overseas demand[footnote 11], and that customers will, in general, pay a premium for British-branded goods above English, Scottish or Welsh goods (notwithstanding the benefits of national branding)[footnote 12]. A highly integrated Internal Market plays an important role in protecting consumer interests as well as the general welfare of UK citizens and a strong UK economy that acts as an advertisement for inward investment and export opportunities.

79. In this context, unmanaged regulatory differences can impede business growth and reduce its contribution to the economy, affecting consumer prices. Indeed, consumer groups highlighted that regulatory differences could create consumer confusion and risk loss of confidence for consumers both within the UK and for those consumers overseas who buy into the UK brand. They also highlighted the potential for reduced consumer choice, if businesses were to fail or new barriers were created that prevented the marketing of a product or provision of a service in one part of the UK. This point was also made by businesses: a food sector business observed that if the cost of accommodating regulatory differences in other regions became too high, they would have to withdraw from the market in that region. Consumer groups highlighted that these issues could be compounded by the current consumer landscape where, in their opinion, there is already intensified underrepresentation of Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish consumers.

How does regulatory difference affect business?

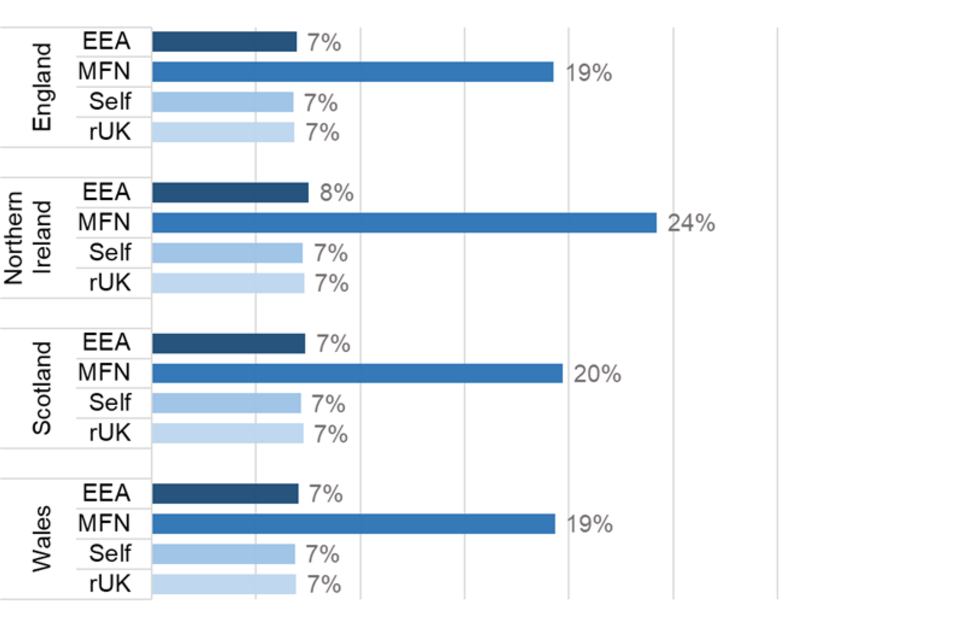

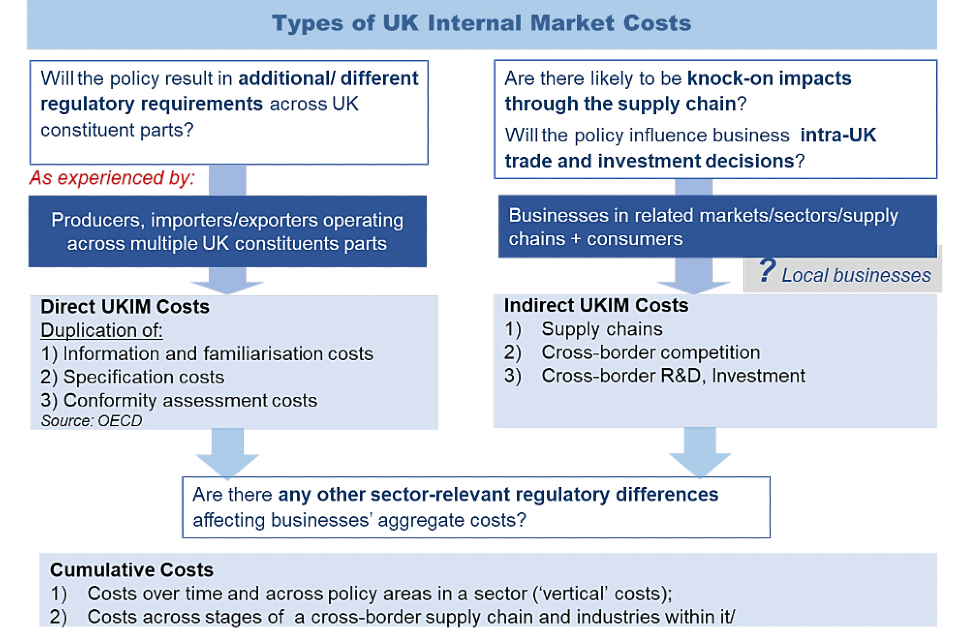

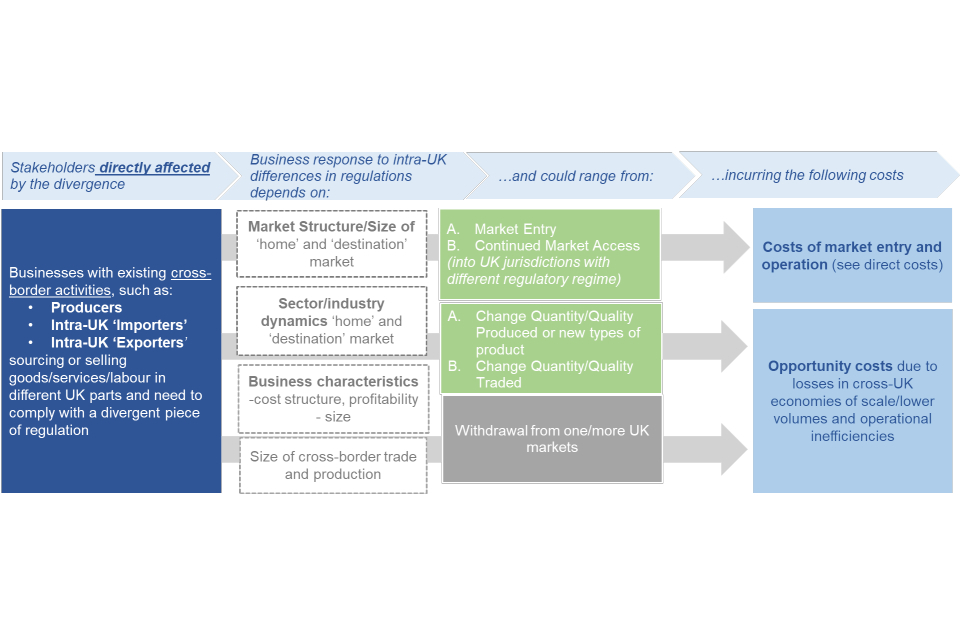

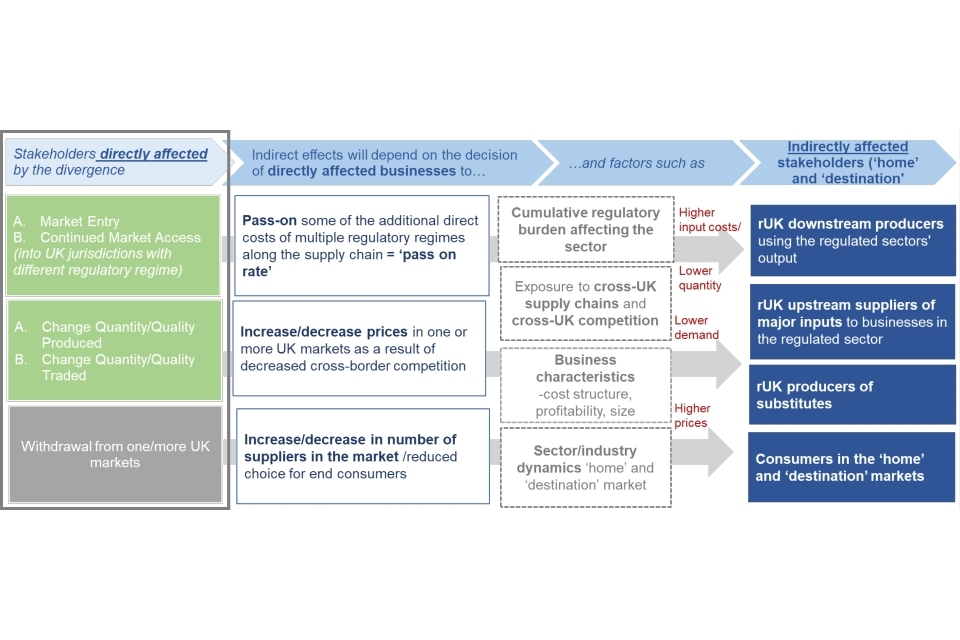

Differences in regulation can have the equivalent effect of a tax or a tariff on products or services from other jurisdictions because they introduce an additional cost for producers.

The OECD identifies 3 types of direct costs facing businesses as a result of regulatory differences: specification costs (for example, modifying products, running separate production lines, or creating different varieties to service different markets), familiarisation costs (for example, to understand the different regulatory requirements), and conformity costs (for example, to prove that a product is fit for sale in the other market).

In an international context, the World Bank Technical Barriers to Trade Survey reports that the one-time specification costs – which represent the greatest barrier to market entry – make up 4.7% of the annual value added for the firms in the survey. For example, the Society of Motor Manufacturers & Traders estimates that obtaining whole vehicle approval can take between 6 to 18 months to obtain, and can cost anything between £350,000 to £500,000, without including indirect costs. Certification fees for farming and growing to Soil Association or EU organic standards can cost between £399 to £1,060 depending on the size of the registered land.

[footnote 13], [footnote 14], [footnote 15]

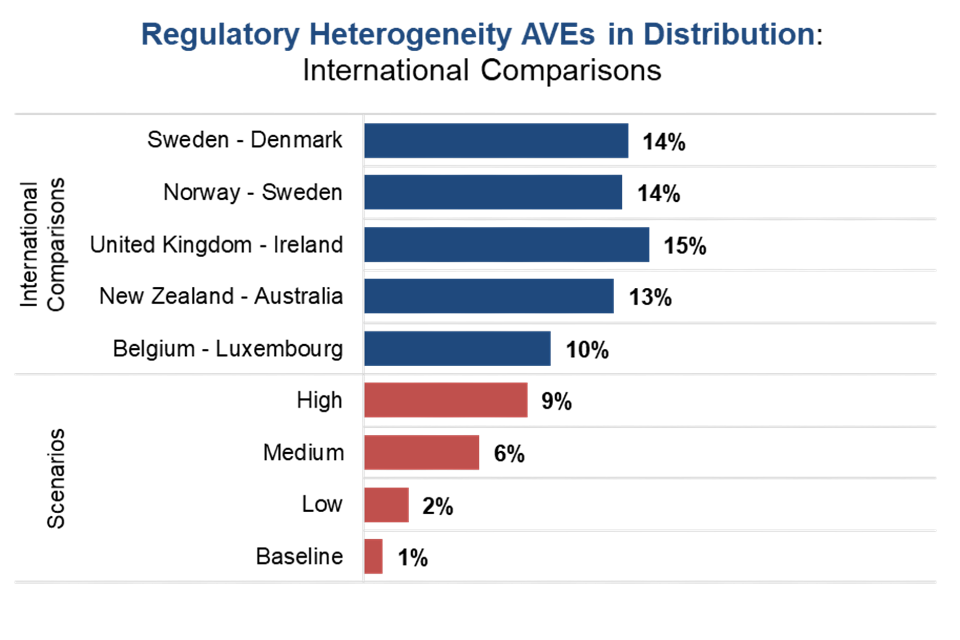

80. BEIS economic modelling of new differences in regulation in selected sectors also shows that they could drive an economically significant wedge between producer costs in the ‘home’ UK market and consumer prices in the ‘destination’ UK market.

The cost of cumulative regulatory differences, selected sector case studies

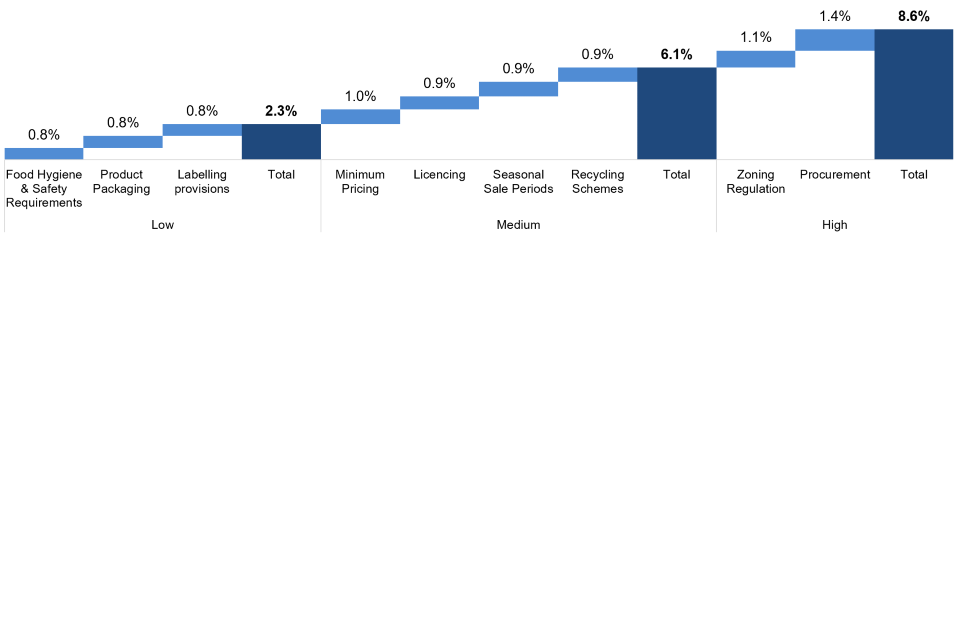

Retail & Wholesale

A realistic scenario of several small policy differences (modelled through differences in food safety, labelling and product packaging) could result in costs equivalent to a 2% tariff for retailers and wholesalers. For example, if these policy differences were to arise between Scotland and the rest of the UK, Scotland’s retail & wholesale sales to the rest of the UK could initially decrease by 7%, or by £433 million based on current annual trade volumes.

Retail transactions totalled £366 billion in 2017 and represent approximately 42% of total average household spending across the UK, which means that even small changes in prices might have a significant impact on consumers.

[footnote 16], [footnote 17], [footnote 18]

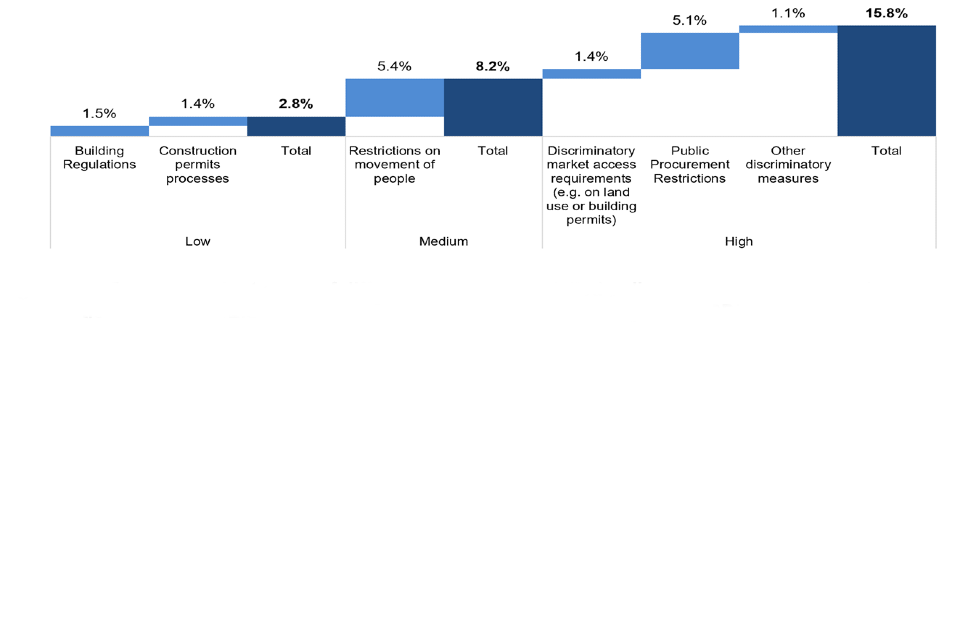

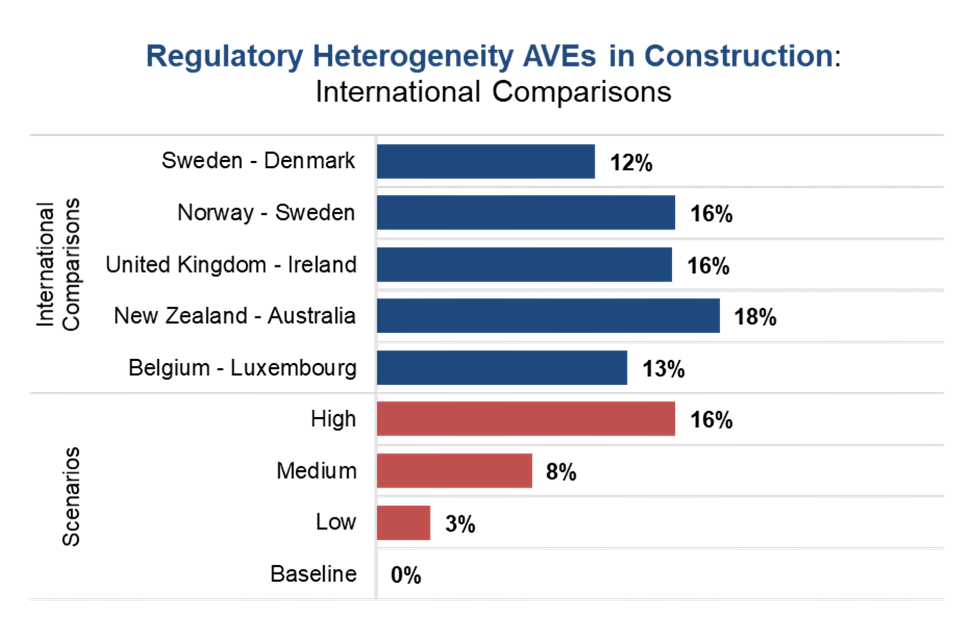

Construction

Economic modelling of divergence in regulation in the construction sector shows that while individual regulatory differences create only small increases in the costs of trading with the different parts of the UK, in a realistic scenario of several small policy differences, new barriers could create the equivalent of a tariff of 3%, while a moderately more impactful scenario of policy divergence in the construction sector could lead to a cumulative tariff equivalent of over 8%.

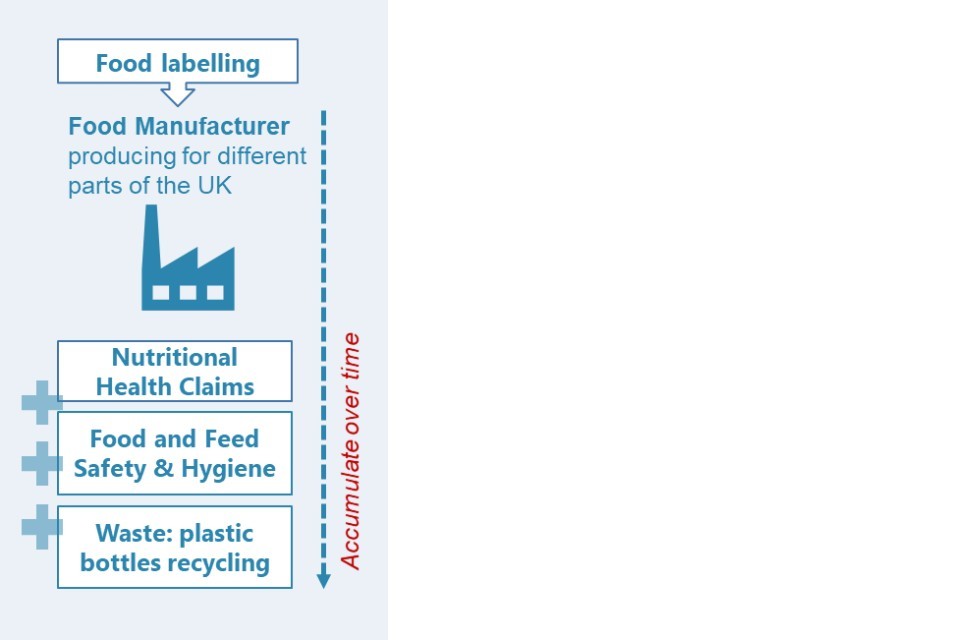

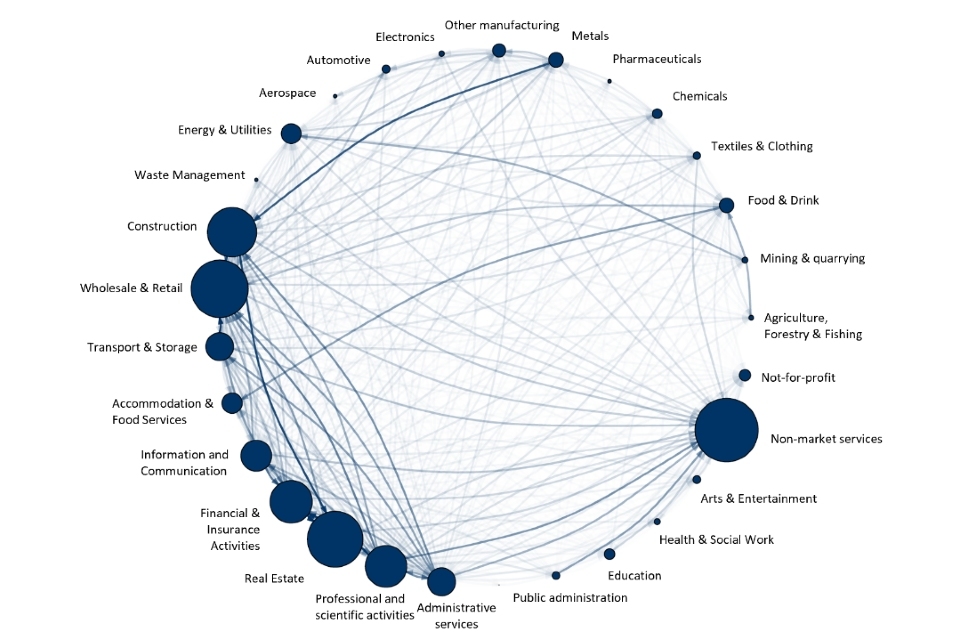

81. These costs triggered by regulatory differences can have spill-overs across the highly integrated supply chains that span the UK market, that is, impacts on others across the economic network. Businesses may be restricted in their choice of suppliers or face higher prices for inputs, which they may pass on to their buyers or consumers. Reducing the number of businesses active in a market can also have large impacts on the degree of competition, potentially increasing prices for the end-consumers or crowding out smaller businesses.

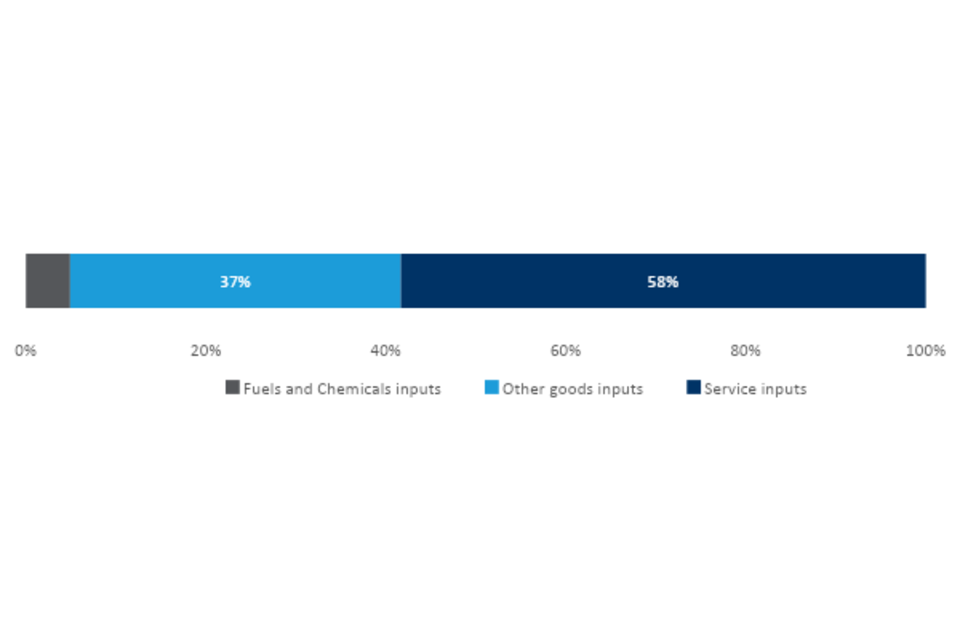

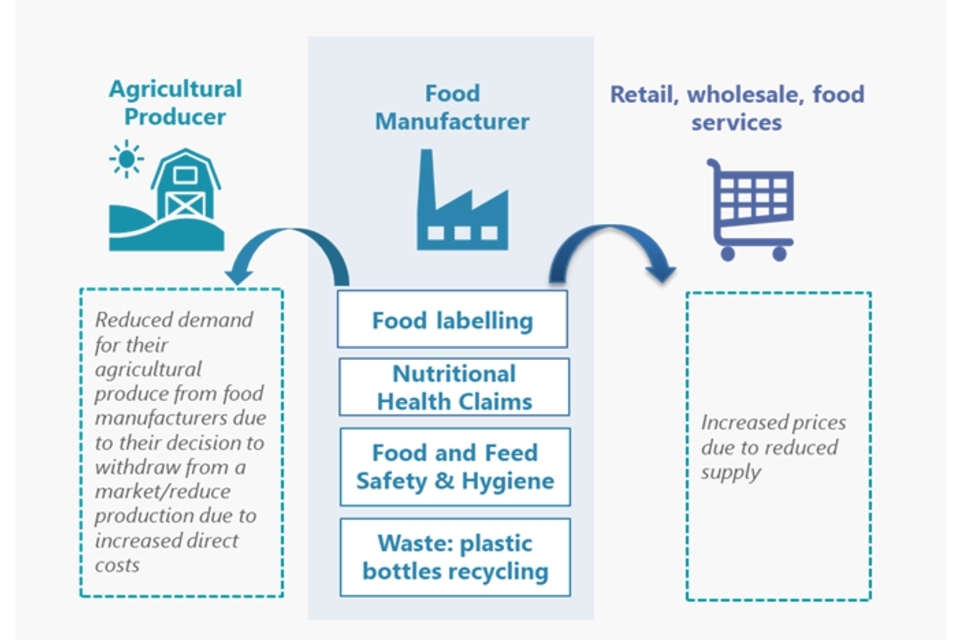

82. The below image (Figure 3) shows the levels of integration of Wales’ agri-food supply chain with the rest of the UK and the large number of regulatory interventions which could impact upon the activities that take place within it. According to the EUREGIO dataset from 2010, Welsh food and drinks manufacturers source 48% of agriculture inputs from the rest of the UK[footnote 20]. Food and drink manufacturers often sell their products through retailers in other UK markets. Approximately 31% of food and drink sold by Welsh retailers and wholesalers were produced in another part of the UK.

Figure 3. Mapping of policy areas affecting each stage of a typical agri-food supply chain, on the example of Wales

Figure 3

83. The image below (Figure 4) highlights the potential costs which could be passed along both to the businesses and customers throughout a supply chain. If uncoordinated, multiple regulatory differences at different stages of the supply chain have the potential to pass excessive and unnecessary administrative and financial burdens to both businesses and consumers.

Figure 4. Illustration of the build-up of direct and indirect costs at each stage of the food supply chain, on the example of ‘the humble sandwich’

As an example, consider the humble sandwich sold in a supermarket or a food outlet. With an average price of £2, around 8.2 billion sandwiches are purchased every year in the UK.

The final sandwich price on the shelves of a supermaket or a small sandwich shop could reflect:

- indirect costs passed on from suppliers such as food manufacturers having to comply with different food labelling and packaging requirements across the UK. The estimated (one-off) cost to relabel per unique product type is between £4,000 - £7,000*

- direct costs of having different recycling requirements for the packaging across the UK

The sandwich maker’s pricing would in turn reflect the:

- indirect costs of farmers having to comply with different animal and plant health regimes across the UK for the meat used in the sandwich, or the different pesticides residues in the tomato and lettuce

- direct costs of different food safety and labelling for this product

Using pesticides as their inputs, farmers would also need to absorb:

- indirect costs of chemical producers, losing economies of scale as a result of not being able to produce certain bulk chemicals

- direct costs of different animal and plant health or pesticides regulations

(* British Sandwich & Food to Go association, 2020. ** Campden BRI/Defra (2010). Updated to 2019 prices. ‘Developing a framework for assessing the costs of labelling changes in the UK’.

84. If left unmanaged, the cumulative burden of multiple regulatory differences could create significant costs that become a deciding factor in business decisions to produce, trade and invest UK-wide. An inquiry by the Canadian Standing Senate Committee on Banking Trade and Commerce estimated that the effect of eliminating internal trade barriers in the Canadian economy would range between 0.05% and 7.0% of gross domestic product, or between C$1 billion and C$130 billion. It should be noted though that Canada was facing a high degree of Internal Market fragmentation, with significant divergence between provinces[footnote 21].

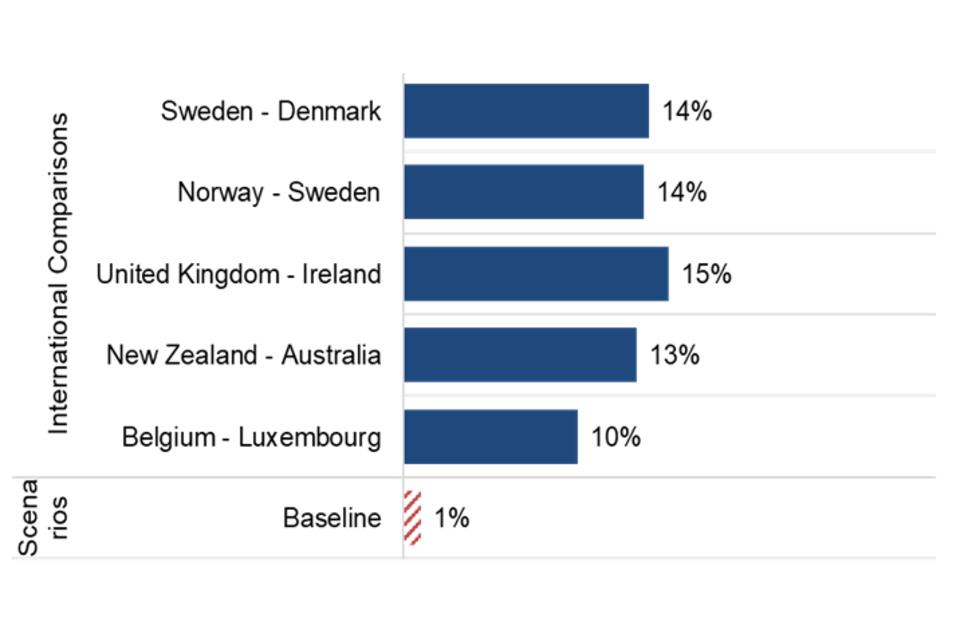

85. While currently the costs of trading between the different constituent parts of the UK are low, an increase would be likely to have a significant impact on GDP. In a modelled scenario where intra-UK trade costs increased to the level seen between German states, UK GDP would reduce by £7.3 billion. If barriers exceeding those found in Germany were introduced the UK GDP loss could be greater[footnote 22]. However, these costs would likely not be distributed evenly. Instead, economic modelling shows that, in relation to the size of their economies, the reduction in Scottish and Welsh GDP would likely be nearly 4 and more than 5 times larger, translating into absolute GDP losses of £1.9 billion and £1.2 billion for Scotland and Wales respectively. BEIS analysis of higher potential intra-UK trade costs shows that while local and international consumption would increase in response, this is insufficient to offset the negative impact on trade between the constituent parts of the UK.

86. Impacts such as these show the need to provide a single underpinning for the UK market that will prevent unnecessary barriers and new costs for businesses and consumers. Such an underpinning would provide an essential commitment to all business and consumers that their economic freedoms will be preserved, and with them, a complex web of economic interactions that impact on everyday lives.

Managing regulatory difference: the need for a UK model

87. In light of such impacts, there already exists a recognition that regulatory coherence is an important part of the UK’s overall economic prosperity. This is why the UK government, jointly with the devolved administrations, are looking to agree a UK-wide, sector-by-sector approach to certain policy areas currently governed by EU law and that intersect with areas of devolved competence.

88. The Common Frameworks programme developed jointly between the UK government and devolved administrations will create an intergovernmental policy development and decision-making process, and provide high levels of regulatory alignment in specific policy areas along with roles and responsibilities of each administration. All Frameworks will adhere to the principles agreed between the UK government and Scottish and Welsh governments at the Joint Ministerial Committee (European Negotiations) (JMC(EN)) in October 2017, and later by the Northern Ireland Executive. These include the principle that frameworks should be created where necessary to ‘enable the functioning of the UK Internal Market whilst acknowledging policy difference’.

89. Common Frameworks will support the devolution settlements and the democratic accountability of the devolved legislatures and will therefore be based on established conventions and practices. Frameworks will also maintain, as a minimum, the same degree of flexibility for tailoring policies to the specific needs of each territory as was afforded by the EU rules. In some policy areas, Common Frameworks will aim to establish and maintain common standards in order to maintain our high regulatory standards. Frameworks will be the vehicle for discussing and maintaining standards in relevant policy areas.

90. Common Frameworks will also ensure that officials work closely across participating administrations to design policy that benefits all parts of the UK and avoids disruptive divergence. This will still enable administrations to innovate but in discussion with other administrations and ensure that new regulations are interoperable. The Scottish Government officially withdrew from the UK Internal Market project in March 2019 but remains an active participant in the Common Frameworks programme. This has driven further the need to legislate to protect the areas that the Frameworks are not designed to cover.

91. Depending on the nature of the powers transferring from the EU, Frameworks may facilitate the setting up of new bodies and forums to take on functions previously captured through EU structures. There is a range of powers returning from the EU which will intersect with devolved competence[footnote 23]. This will directly impact on some Common Frameworks more than others. For example, DEFRA has placed multiple policy areas which are the subject of returning powers within the scope of the Animal Health and Welfare Frameworks. This means that these Frameworks will be the vehicle used by the UK government and devolved administrations to discuss with one another any potential introduction or changes to the regulation within scope. The Company Law Framework, however, will only allow the UK government for Great Britain, and the Northern Ireland Executive for Northern Ireland, to do this for a few regulations. The Common Frameworks therefore vary greatly in the numbers of returning powers they cover.

92. Common Frameworks constitute a valuable mechanism to ensure all parts of the UK agree common approaches where possible. The additional cross-cutting measures set out in this white paper, will be, however, necessary to complement them. This is for a number of reasons.

93. Firstly, Frameworks are not able to assess the wider economic impacts or knock-on effects of regulatory divergence, including how regulatory differences in one sector affects other sectors (the so called ‘spill-over effect’). Secondly, Common Frameworks do not address how the overall UK Internal Market will operate once the UK has left the overarching EU system at the end of the transition period. Lastly, as Frameworks are limited to a specific number of policy areas, they will not account for the full UK economy across goods and services, and therefore will not be able to provide a comprehensive safety net for businesses and consumers.

94. As a result, in order to ensure that a post-EU UK Internal Market delivers continued fair, coherent, frictionless trade across all parts of the UK, these gaps need to be addressed through a more robust legal architecture.

Trade in services: the need to understand the context of the wider ecosystem

95. Given the potential for different regulation across the UK to impact on the provision of services, it is important to also maintain coherence across services provision as the transition period concludes.

96. Intra-UK regulatory differences could create barriers to services trade. For example, construction projects across the UK are influenced by the regulation of construction professions in the ‘destination’ market. These might differ to those in the ‘home’ market of a construction firm. Economic modelling of regulatory differences in the regulation of construction professionals between the ‘home’ and ‘destination’ market suggest that these could build up to a cost equivalent of a 5% tariff if these differences were left unmanaged[footnote 24]. UK construction accounts for 6% of total UK annual GVA, or £116 billion[footnote 25] .

UK internal services trade

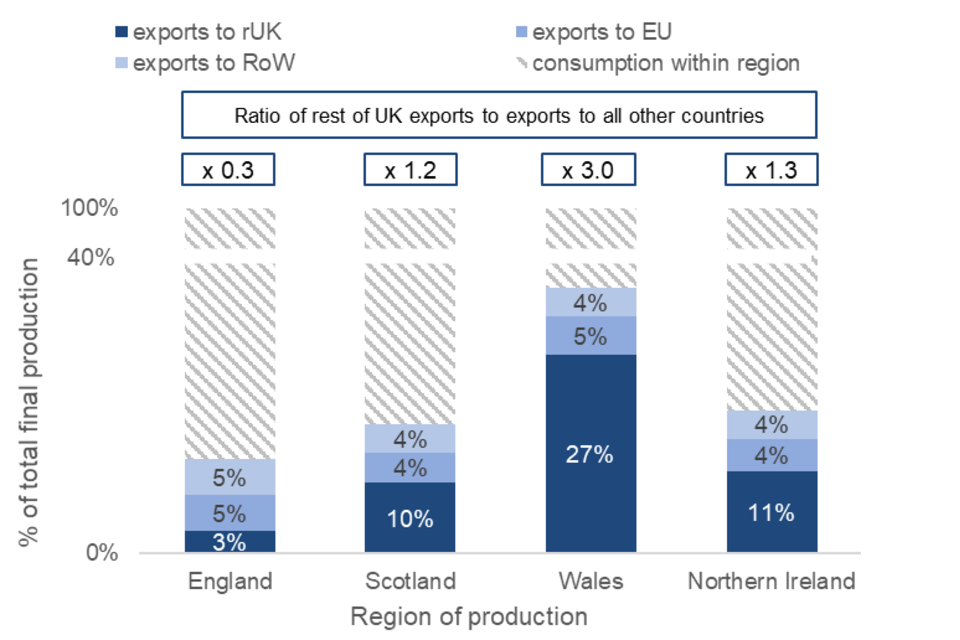

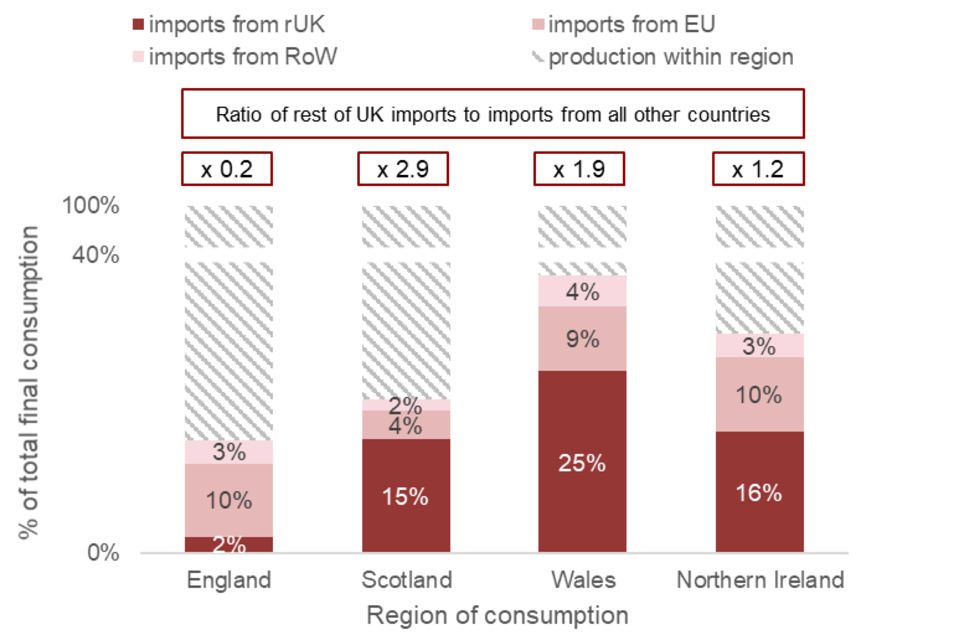

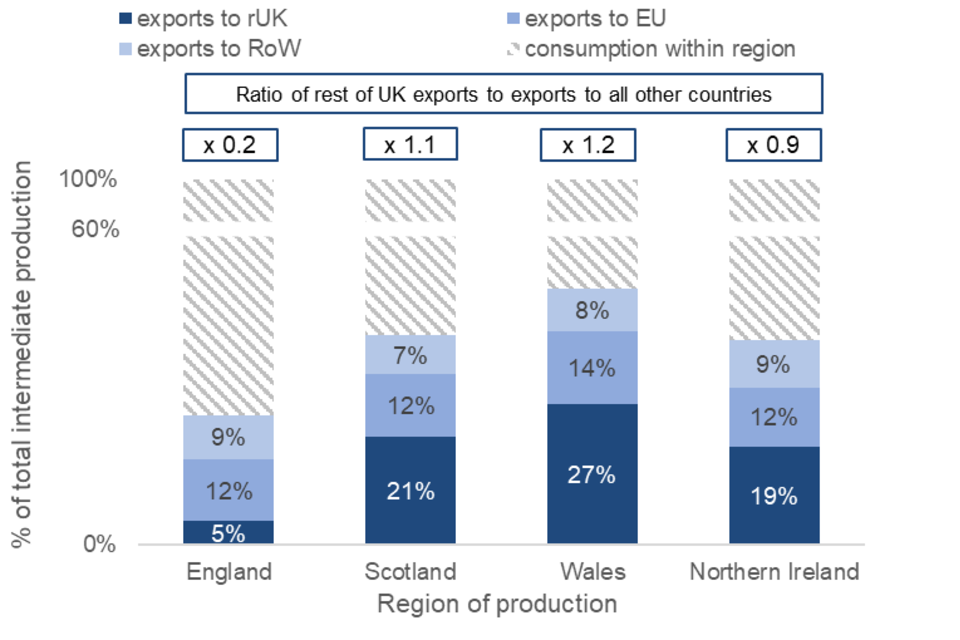

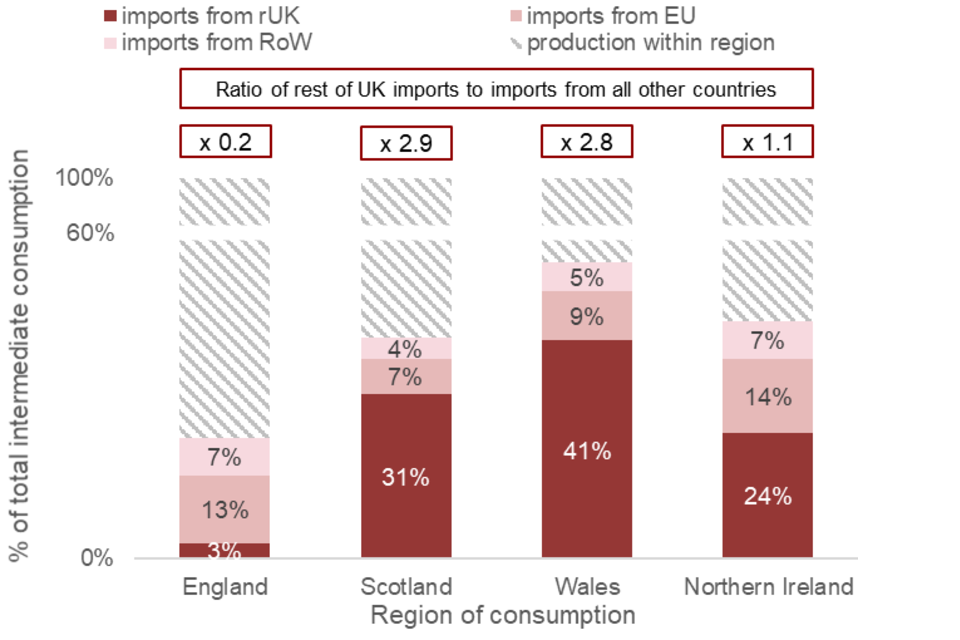

The UK Internal Market plays an equally big role for services as for goods. For each of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, a large proportion of total services production and consumption is destined for, or originates in, another part of the UK, similar to the case with intra-UK trade in goods. In contrast to goods, where a relatively greater proportion of trade occurs internationally, services are more likely to be traded within the UK Internal Market. According to Export Statistics Scotland, the value of Scotland’s services exports to the rest of the UK has consistently outpaced its international exports by around 2.4 times over the last 10 years, while in Northern Ireland, official statistics show that 3 times as many services are purchased from Great Britain compared with international imports.

97. Separately, the UK government plans to review the objectives for regulating professions and recognising international qualifications. The government wants to make sure that professional qualifications support a productive economy and help maintain workforce supply after the end of the transition period. These findings will be implemented alongside, and will work together with, the approach to professional qualifications in the UK Internal Market.

Scope of the government’s response to the evolution of the UK Internal Market

98. One of our key objectives for the UK Internal Market is to ensure the protection of intra-UK trade by avoiding the creation of unnecessary barriers caused by regulatory differences between the UK government and devolved administrations (see below for a more detailed explanation of proposed Internal Market objectives). Given that we are looking to address the impacts of regulatory difference, we will be excluding areas of regulation in which the UK government can set common rules within the UK. The scope of the UK Internal Market proposals will therefore exclude reserved/excepted areas to the extent they are reserved/excepted within each devolution settlement[footnote 26].

99. Potential regulatory differences for goods in reserved/transferred areas due to the Northern Ireland Protocol will be considered separately, as outlined in Part 2.

100. As set out in preceding sections, the UK Internal Market system should be broadly focused on regulatory requirements that impact on the provision of goods or services. Given the wider effect of returning EU law, this is the area where the potential for new divergence will be most apparent, and where the impacts of divergence will be most costly without a market access commitment. The complexity of supply chains in the UK Internal Market means that differences across a wide range of regulation can create ‘grit’ to trade flows, often where it is not immediately obvious. The legislative system set out in this paper will therefore cover a wide range of regulation, with more detail on the specific scope of the legislative model provided later in this section.

101. It is important to recognise that most potential barriers to internal trade can come from differences in regulation which do not take the form of primary legislation. To preserve the UK Internal Market as an integrated trading space, the Internal Market system will cover wider regulatory powers, such as secondary legislation and regulation made, not just by governments, but also by other regulators concerned with regulating professionals and service providers. This should be in scope where it could significantly impact the UK Internal Market as a whole.

102. In the area of services, factors that impede trade flows will affect both industry and individual lives. With the UK being a services-based economy, but with a strong interaction with goods and production, consistency and certainty are vital. It is therefore important for the UK Internal Market system to facilitate the provision of services throughout the UK, whether they are based on professional qualifications, licensing or other authorisation schemes.

The objectives for the UK Internal Market

103. The main objective of a UK Internal Market system is to guarantee the economic interests of business, consumers and workers, working with the grain of the UK’s constitution to support devolved decision making. This means ensuring a robust and prosperous Internal Market that creates opportunity, maximises choice and best value for consumers, with decisions made as close to the businesses and citizens they affect as possible.

104. The 3 overarching objectives for the UK Internal Market system are therefore:

- to secure continued economic opportunities across the UK

- to continue to increase competitiveness and enable citizens across the UK to be in an environment that is the best place in the world to do business

- to continue to support the general welfare, prosperity and economic security of all our citizens

105. In addition to these overarching objectives, there are 3 supporting aims:

Supporting aim 1: Maintain frictionless trade between all parts of the UK

106. A key objective for any model of Internal Market should be to continue to protect the interests of businesses and consumers by ensuring they can continue to do business in all parts of the UK without unnecessary barriers. Such barriers, if allowed to emerge, could increase business costs, in some cases passed onto consumers, or reduce consumer choice. In some instances, they could add up if multiple areas of regulation are affected.

Supporting aim 2: Maintain fair competition and prevent discrimination

107. Any Internal Market system should avoid economic protectionism. We should ensure that business or consumers in one part of the UK are not favoured over others, and that one part of the UK cannot create the potential to undercut businesses from a different part. Considerations of fairness are fundamental to a viable Internal Market system, not allowing for one part of the UK to discriminate against businesses from another part.

Supporting aim 3: Continue to protect business, consumers and civil society by engaging them in the development of the market