Great teachers

Updated 19 February 2024

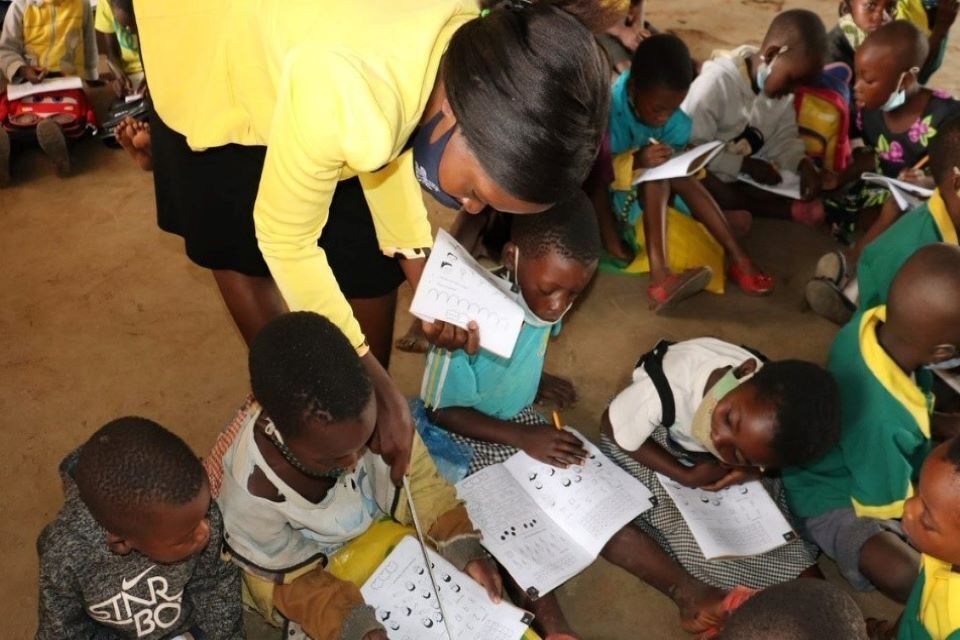

A teacher from the National Numeracy Programme teaches her students in Malawi. Credit: Ministry of Education, Malawi.

Teachers matter. Teaching quality is the most important factor affecting learning in schools. Good teachers and good teaching are key to how we improve the quality of education for all children.

The cost of the education workforce accounts for 75% or more of the national education budget in many countries. However, many teachers remain untrained – almost 40% of primary school teachers in sub-Saharan Africa.[footnote 1] Supporting the education workforce is crucial in the deepening education crisis, where most children in low- and middle-income countries are leaving primary school unable to read.

In England, there was on average one trained teacher per 21 students in primary schools and one trained teacher per 17 secondary school students in 2021 to 2022.[footnote 2] UNESCO research about sub-Saharan Africa shows averages of one trained teacher per 58 students at primary level, while in secondary school the ratio is closer to 43 pupils per trained teacher. This means less teacher-student contact, less individualised teaching, and lower quality of education.

The ratio of teachers to students in primary and secondary school in sub-Saharan Africa.

The region also has the lowest percentage of female teachers in primary education, at below 50%. In secondary education, only 30% of teachers were women in 2018. In the UK 74% of the teaching workforce were women in the year 2021 to 2022.[footnote 3] This shortage of female teachers in sub-Saharan Africa has important implications for girls’ enrolment, as female teachers have a positive impact on girls entering and remaining in school.

Programme case study: Josiane and Rwanda learning for all

When she was 6 years old, Igihozo Teta Gaella’s school in Rwanda was forced to close due to the COVID-19 pandemic. With UK support, lessons were provided by radio. The Rwanda Learning for All programme supported teachers like Josiane to prepare scripts and lesson plans to help keep children learning safely throughout the pandemic.

Find out more in the video about Igihozo and her teacher Josiane:

Rwanda learning for all (YouTube)

Programme case studies: Shule Bora, Tanzania and Leh Wi Lan, Sierra Leone

Children in Tanzania supported by the Shule Bora programme. Credit: British High Commission Dar es Salaam.

‘Shule Bora’ means best schools in Swahili. This UK programme will keep 4 million Tanzanian children in school, with special emphasis for girls, children with disabilities, and children living in deprived areas. The programme is also supporting the Government of Tanzania to invest in the training and resources that teachers need to be their best. In its first year, Shule Bora provided support to the Government to develop parent teacher partnership guidelines for pre-primary and primary schools, training over 14,000 people across 9 regions. These parent teacher partnerships are important to supporting quality, inclusive education in Tanzania.

The ‘Leh Wi Lan’ (Let Us Learn) programme in Sierra Leone supported more than 11,000 marginalised girls and children, and their teachers, across 5 districts. This includes helping 250 young women to become teachers through a distance learning programme, and providing assistive devices for over 5,000 children with disabilities.

Following the Ebola crisis, there were large learning gaps after periods of school closure. Little was known about how to improve teaching practice and quality. Leh Wi Lan focused on supporting teacher professional development to improve quality and learning outcomes. The programme introduced a lesson observation and feedback model, working closely with the Government of Sierra Leone.

-

Closing the gap – ensuring there are enough qualified and supported teachers in sub-Saharan Africa (teachertaskforce.org,). Accessed 10 July 2023 ↩

-

Education and training statistics for the UK, Reporting year 2022 – Explore education statistics – GOV.UK (explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk). Accessed 21 July 2023 ↩

-

Education and training statistics for the UK, Reporting year 2022 – Explore education statistics – GOV.UK (explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk) ↩