Supplementary Guide: Realist evaluation (HTML)

Updated 9 July 2025

1. Realist Evaluation: What it is and when to use it

Realist Evaluation[footnote 1] (RE) seeks to understand how a policy or programme causes the desired outcomes. The purpose of a realist evaluation is as much to test and refine the theory behind the policy intervention as it is to determine the policy’s outcomes in a particular set of circumstances. A realist evaluation asks not ‘what works?’ or ‘by how much does it work’ but ‘what works, for whom, in what respects, to what extent, in what contexts, and how?’

RE is a member of a family of theory-based evaluation methods. It is particularly appropriate[footnote 2]:

- for evaluating new initiatives, pilot programmes and trials, or programmes that seem to work but ‘who for and how’ is not yet understood;

- for evaluating programmes that will be rolled out, to understand how to adapt the intervention to new contexts;

- for evaluating programmes that have previously demonstrated mixed patterns of outcomes, to understand how and why the differences occur.

The principles of RE can also be used in conducting systematic reviews of the evidence base; this is ‘realist synthesis’[footnote 3].

RE may not be appropriate when[footnote 4]:

- how, why and where programmes work is already well understood;

- understanding how a programme works is not relevant to its function (for example, for many psychiatric drugs the causal pathway is little understood but what matters is the correlation between dose and outcome);

- the only answer required from the evaluation is about the average net effect of the intervention;

- programmes are genuinely simple and where one size really does fit all;

- there is no outcome data available;

- the human and financial resources required to undertake a realist evaluation are not available.

2. Introducing Realist Evaluation

Social systems are complex and the social programmes that successfully influence them generally need to take account of such factors as the reasoning, preferences and norms of the target group. RE emphasises the importance of understanding how an intervention works and in what context. RE aims to open up the ‘black box’ of the policy intervention to understand why the observed outcomes occurred and to explore the interplay of stakeholders, resources, beliefs, outcomes and circumstances. This can help to develop the evidence base around a policy area and pave the way for the generalisation of the programme.

A common problem in evaluation is that the precise mechanisms of the programme are unobservable. For example, in a school where a new teaching method is used we do not ‘see’ the content of the lessons being stored in the children’s memories nor is it easy to ‘see’ the new connections being made in their brains. The effect of the programme (i.e. the new teaching method) is inferred from statistical tests. Typically, two more-or-less similar groups of subjects of which one is given a ‘treatment’ (the programme) and one is not (the ‘counterfactual’). The statistical tests are designed to see if there has been a significant change in the treated group; if there is, then this is attributed to the effect of the programme.

However, when the causal mechanisms of programme are not understood, this can lead to situations where the programme is ‘rolled out’ to other areas or other groups of people, but the beneficial effects of the programme are not realised. Without an understanding of the causal mechanisms, the reasons for the failure are often not immediately apparent. RE aims to address this shortcoming. A realist evaluation does not rely solely on inferred causation from statistical tests; instead, specific, hypothesised, causal mechanisms are articulated and evidence gathered for each.

3. Developing realist theory: Context, mechanism and outcome

In RE, policy interventions are seen as creating opportunities upon which people may choose to act if they are so minded and able. A fundamental concept in realist evaluation is that it is not the intervention itself that causes the outcome but, instead, it is an individual’s response to the resources and opportunities provided by the intervention that causes the outcome[footnote 5].

The combination of a programme’s resources and an individual’s response to them is termed in realist evaluation ‘the mechanism’. It is this mechanism that determines the outcome. A realist evaluation holds that an individual will likely respond to an intervention differently in different circumstances. It is the combination of an individual subject’s inner potential with a particular set of circumstances – a context that determines the outcome. Thus, the key formula in RE is:

context + mechanism = outcome. (CMO)

A central feature of realist evaluation is that the initial programme theory is developed in this CMO format.

Figure 1: The operation of social programmes[footnote 6]

4. A theoretical example

Imagine a spark applied to some gunpowder. If the gunpowder is dry and in a confined space, then a spark will cause the gunpowder to explode. In this example, the inner potential is the chemical composition of the gunpowder giving it the capacity to explode, the confined space and dryness are the context, the spark is the mechanism and the explosion is the outcome. In summary:

context + mechanism = outcome

or

dry, confined space + spark (applied to gunpowder) = explosion

We can apply this thinking to policy interventions. They create opportunities upon which people may choose to act. The success of a programme for an individual rests on their reasoning and how their reasoning changes depending on their circumstances and external factors. RE examines this.

5. Applying the realist frame to evaluation

The task of the realist evaluator is to find ways of identifying, articulating, testing and refining hypotheses regarding particular combinations of: context, mechanism and outcome (CMO). This is the heart of the method. Outcomes are not inspected simply to see if programmes worked but are analysed to discover if the hypothesised CMO theories are confirmed.

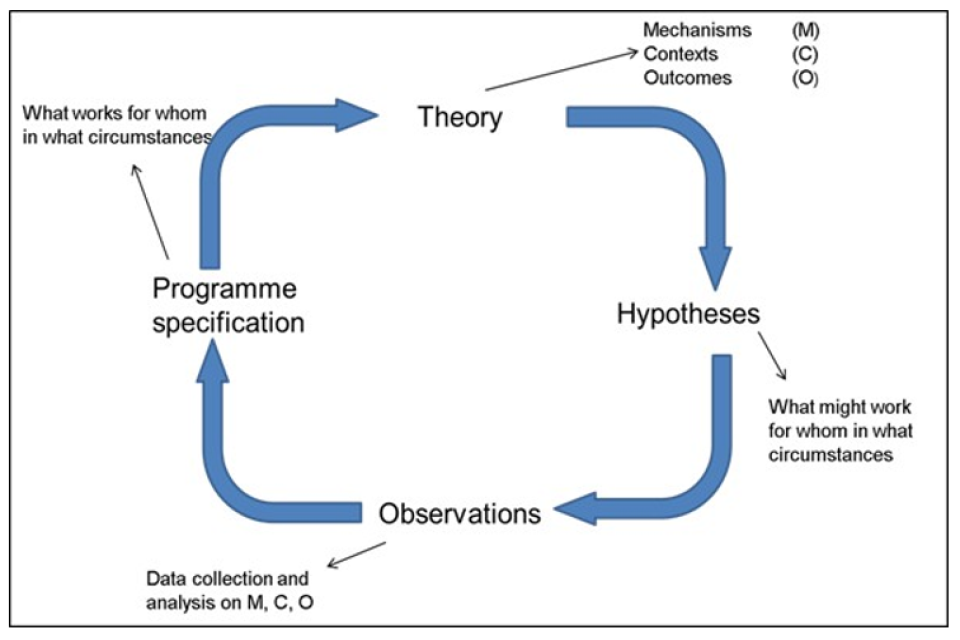

Realist evaluation follows a cycle as shown in figure 2:

Figure 2: the Realist evaluation cycle[footnote 7]

In this cycle, the first step is to understand the formal theory upon which the programme is based. The theory is then translated into CMO terminology.

The second step is to develop CMO hypotheses that the evaluator thinks should be tested. The most important hypotheses to be tested are likely to be those that relate to key causal chains in the theory behind the programme. They may also relate to particular gaps in the evidence base underpinning the policy. Hypotheses link together the context, mechanism and outcome in a sentence (e.g. in this context, these mechanisms lead to x outcomes’. Each of these hypotheses are called a CMO configuration (CMOC) and hold a different combination to be tested.

Aside: Practitioner’s tips

Realist practitioners have identified two tactics that helped in the creation of CMOs[footnote 8]. The first tactic is to draft a single sentence that explains the whole CMO without using realist terminology. The second is to label each CMO with its own shortened name or metaphor. In the example below (figure 3) from the Department for International Development’s ‘Building Capacity to Use Research Evidence’ (BCURE) programme, the evaluation team named the CMO the ‘eye opener’ and drafted a (rather long) sentence to describe it[footnote 9].

Figure 3: A BCURE CMO configuration, labelled the ‘eye opener’

| Detail | Intervention | Context | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICMO 2: the ‘eye opener’ | Where training interventions are practical, interactive, needs-focused, offer practical skills, and target people who can directly apply learning… | …and where there are external pressures or motivations to apply training…and participant’s already have internal motivation for evidence use… | …this sparks an eye-opener, in which participants see that training is immediately applicable to their own work, and put into practice… | … leading to immediate behaviour change in witch individuals apply evidence-informed policy making principles in their own work. |

The third step is data collection and analysis (‘observations’ in figure 2). This includes collecting information on how the programme has worked differently for different groups and in what context. The design of this step is driven by the agreed evaluation questions and the identified hypotheses. RE is not prescriptive regarding the method used to make causal inferences; in fact, it is method-neutral both in terms of data collection and analysis.

In the fourth step, findings from the analysis are used to refine the theory of the programme, identifying how context affects the outcomes of the programme and what the mechanisms may be. This produces observations with clear implications for policy decisions.

We will now conclude our introduction to realist evaluation with three examples of RE in policy making.

6. Further examples of Realist Evaluation

Example 1

The marking of property to show ownership has long been used as a way of reducing vulnerability to theft. If we understood better how property marking contributed to the reduction of theft, then it may be possible to develop schemes to apply it more effectively and widely.

In an evaluation of a burglary and theft prevention programme, four possible mechanisms whereby property marking might have an effect on domestic burglary were identified (see table 1 below). This was used as the starting point for a subsequent study and evaluation of property marking where the intention was to find evidence for and against each of the mechanisms listed in the table.

Table 1: Mechanisms for reducing theft by property marking

- Property marking might increase the difficulty of disposing of stolen goods (outcome), since it would be more obvious to purchasers that the items had been stolen (mechanism). 2.Property marking might increase the detection of offences and conviction of offenders (outcomes), since their possession of stolen property would more easily be established (mechanism).

- Property marking might lead to increases in the rate at which stolen property is returned to its rightful owners (outcome), since on recovery of stolen goods the address of the owner would be known to the police (mechanism).

- Property marking might deter burglars (outcome) because of anticipated difficulty in disposing of the goods and/or greater risks of prosecution (mechanisms).

The context in which the new trial was conducted was carefully chosen by the researcher such that:

- There was very extensive local publicity for the scheme.

- There was high-density property marking – every house was visited by a police officer and invited to take part.

- The trial area was three relatively isolated villages. This limited the scope for crime to be displaced (i.e. moved) to other areas.

This method ensured that the trial was implemented in a context where the impact of property marking could be most clearly seen.

The researcher found that there was a statistically significant fall in the number of burglaries and that the evidence tended to support the fourth hypothesised mechanism i.e. deterrence. She used her findings as the basis for further conjectures concerning mechanisms triggered by property marking in the context of the programme. For example, she suggested that deterrence might arise from the use of window stickers to indicate that the household was participating in the programme rather than property marking itself.

This research contributed to the evidence base of what reduces property theft, how and in what context. Areas for further research were also identified.

Example 2

The Department for International Development (DFID) commissioned a realist review[footnote 10] of the state of knowledge in the area of community accountability initiatives in education. Community accountability is concerned with the ability of local communities to hold governments and service providers accountable to them for the provision of services. Key elements of accountability include transparency of decision‐ making, answerability, enforceability and the ability to sanction.

Community accountability initiatives have been advocated as a way of improving educational outcomes, but several reviewers noted they had mixed results. DFID wanted to find out the circumstances where enhancing community accountability improved education, particularly for the poor.

The realist review identified where these initiatives were most likely to succeed by:

- identifying the categories of intervention within which community accountability and empowerment interventions fit;

- proposing examples of 11 mechanisms[footnote 11] through which community accountability and empowerment interventions may work;

- identifying 11 categories of contextual features that affect whether and where community accountability and empowerment interventions work;

- proposing relationships between mechanisms and the elements of context most likely to affect them.

Example 3

The Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy used a realist evaluation to evaluate the Transitional Arrangements (TA) for Demand-Side Response (DSR) in the electricity Capacity Market[footnote 12].

TAs were put in place to help ensure the security of electricity supply and to improve the competitiveness of the DSR industry as it becomes a more prominent part of the main Capacity Market.

The evaluation’s aims were to assess the extent to which the TAs were contributing to their objectives (i.e. the TAs’ additionality) and to identify why industry players participating in the TAs did or did not progress in their involvement.

- For example, one CMOC concerning the TAs’ objective of encouraging new entrants to the market was: ‘organisations that were new to the energy market with an interest in the main Capacity Market (context) acknowledge that the TAs provide a low-risk environment (mechanism: intervention resources) in which they could participate and build their customer base (mechanism: participant response), resulting in more capacity in future for the main Capacity Market (outcome)’.

Applying realist evaluation allowed the policy team to ‘get under the skin’ of organisational decision-making in response to the policy’s design. This enabled them to better understand how decision-making differed between various types of organisation.

RE was found to be an effective evaluation method in an environment characterised by complex interactions, low sample sizes and the inability to control access to the market. These characteristics meant that other methods, such as RCTs and an experimental approach in general, would not have been suitable.

References

Pawson, R. and Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic Evaluation. The Social Science Journal 41(1): pp 153-154 ·

Pawson, R. (2006). Evidence-based policy: A realist perspective. 1st Ed. SAGE Publications

Betterevaluation.org. (2019) Better Evaluation official Website. Available at: www.betterevaluation.org. [Accessed 5th November 2019]

Westhorp, G. (2014). Realist Impact Evaluation: an introduction (PDF, 1MB) . Overseas Development Institute. [Accessed 5th November 2019]

Westhorp, G., Walker B., Rogers P., Overbeeke, N., Ball, D. and Brice, G. (2014)(PDF, 2.1MB). Enhancing community accountability, empowerment and education outcomes in low and middle-income countries: a realist review. EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London. [Accessed 5th November 2019]

Pawson, R., Greenhalgh, T., Harvey, G. and Walshe, K. (2004). Realist Synthesis: An Introduction. ESRC Research Methods Programme Methods Paper 2/2004. University of Manchester. [Accessed 5th November 2019]

Further Resources

Other useful resources that provide background in this field include:

1. ramesesproject.org. (2018). RAMESES Project Official Website. [online]. [Accessed 5th November 2019]

The UK’s National Institute of Health Research funded two separate projects whose goals are to produce quality and publication standards and training materials for realist research approaches.

2. Cartwright, N. and Hardie, J. (2012). Evidence-Based Policy: A Practical Guide to Doing it Better. Oxford University Press.

The authors argue that evaluation methods that imitate standard practices in medicine, such as randomised controlled trials, do not enhance our ability to predict if policies will be effective. Their book focuses on showing policy makers how to effectively use evidence, explaining what types of information are most necessary for making reliable policy, and offers lessons on how to organise that information.

3. Stern E., Stame, N., Mayne, J., Forss, K., Davies, R. and Befani, B. (2012). Broadening the range of designs and methods for impact evaluations. Department for International Development. [Accessed 5th November 2019]

This is a study report dealing with the methodological and theoretical challenges faced by those who wish to evaluate the impacts of international development policies. The report discusses existing impact evaluation practice, reviews the methodological literatures and assesses how state-of-the art evaluation designs and methods might be applied to contemporary development programmes.

-

See Pawson R and Tilley N, ‘Realistic Evaluation’, 1997 and Pawson R, ‘Evidence-based policy: A realist perspective’, 2006. ↩

-

Taken and adapted from Westhorp G, ‘Realist Impact Evaluation: An Introduction’, Overseas Development Institute, 2014. ↩

-

See Pawson R et al, ‘Realist synthesis: an introduction’, 2004. ↩

-

Westhorp G, ‘Realist Impact Evaluation: An Introduction’, Overseas Development Institute, 2014. ↩

-

This is a type of ‘generative causation’. Generative causation is where something internal to the system is necessary for the observed changes to take place. ↩

-

Adapted from Wong G et al, ‘Realist Synthesis RAMESES training materials’, 2012. ↩

-

Adapted from Pawson R, ‘Evidence-based policy: A realist perspective’, Sage, 2006. ↩

-

Punton M et al, ‘Reflections from a realist evaluation in progress: scaling ladders and stitching theory’, Centre for Development Impact, Practise paper: vol. 18, 2016. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Westhorp G, et al, 2014, ‘Enhancing community accountability, empowerment and education outcomes in low and middle-income countries: a realist review’. EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London ↩

-

For example, one of the 11 mechanisms was called ‘eyes and ears’. Here, local community members act as local-data collectors for monitoring purposes, which results in a comprehensive and verifiable basis of information. ↩

-

Evaluation of the transitional arrangements for demand-side response – phase 1 ↩