The lived experience of disabled people in the UK: a review of evidence

Published 17 July 2025

Dr Andrea Hollomotz, Professor Mark Priestley and Deirdre Andre

with Beth Lavery and Fazilet Hadi

(Centre for Disability Studies, University of Leeds and Disability Rights UK)

December 2021

Executive summary

This report discusses the systematic review of lived experience evidence commissioned by the Cabinet Office’s Disability Unit. The review was carried out by the Centre for Disability Studies at the University of Leeds and Disability Rights UK. Its aim was to establish evidence on the lived experience of disabled people in the UK published between 2010 and 2021. It addressed the following research question:

What evidence exists about the barriers and opportunities facing disabled people in the UK, arising specifically from their first-hand knowledge and experience (lived experience), in areas of current policy concern?

Methodology

The evidence review had 3 phases:

-

Around 15,000 potential sources were identified using systematic text searches of databases (mainly academic research) and grey literature. The searches were focused on recent user-led research.

-

Around 1,500 sources were selected based on specific criteria. They were then sorted into 13 policy-relevant themes.

-

The evidence base was mapped thematically and the outputs were created.

For each theme, we explain the context and relevance of articles in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). We then show the range of lived experience evidence, with relevant examples and as a basis for further analysis of the research findings.

Summary of findings by theme

1. Community and social participation

Disabled people often face barriers to social inclusion which affects their everyday lives. Evidence highlights the importance of community engagement and taking part in politics, economics and civil society.

2. Accessibility

There are persistent obstacles in physical and digital environments, including communication and transport. Disabled people say that many spaces are still not well designed or supported, despite some improvements.

3. Independent living and social care

Experiences of choosing and controlling personal support services are vital for independent living. Challenges include transitioning from institutional care and navigating complex social arrangements.

4. Healthcare

Some sources discuss barriers in accessing health services. These highlight systemic issues including:

- discrimination

- lack of information

- inadequate adjustments within healthcare settings

5. Justice

Evidence shows that disabled people often encounter violence, exploitation and discrimination. They also face barriers to accessing justice. These highlight the need for policy improvements to safeguard their rights.

6. Education

Challenges in mainstream education settings include inadequate support and resources for disabled students. There is a need for tailored approaches to ensure educational practices are inclusive.

7. Employment

Barriers faced by disabled people include stigma, discrimination and lack of reasonable adjustments. The findings emphasise the importance of inclusive workplace practices and support systems.

8. Income

Disabled people have a higher risk of poverty and financial instability – particularly through their interaction with the welfare system. Administrative barriers to accessing financial support also affect their economic independence.

9. Housing

Persistent barriers to accessible housing include:

- shortages of suitable properties

- a lack of support for adaptations

Experiences of homelessness among disabled people highlight critical gaps in policies and services.

10. Transport

Many disabled people report accessibility challenges with public transport. These affect their mobility and independence. Improved policies are needed to ensure equal access to transport.

11. Leisure

Physical barriers and social stigma make it harder for disabled people to take part in leisure activities. There need to be more inclusive recreational opportunities that accommodate all types of impairments.

12. Family and private sphere

Relationships and family dynamics are affected by a range of barriers. There are challenges related to parenthood, romantic relationships, and friendships. Many of these are due to societal attitudes and inadequate support.

13. Attitudes

Social attitudes towards disabled people often involve stigma and discrimination. The report highlights the need for awareness-raising initiatives to:

- encourage a more inclusive society

- oppose negative stereotypes

This evidence review illustrates the wide range of barriers faced by disabled people in the UK in different policy areas. It highlights the need for targeted interventions and policy improvements that enable inclusivity and improve their quality of life.

Introduction

This report presents initial findings from an evidence review commissioned by the Cabinet Office’s Disability Unit. The review was carried out by the Centre for Disability Studies (University of Leeds) and Disability Rights UK. Its purpose was to establish the existing evidence base on the lived experience of disabled people in the UK. It addressed the following research question:

What evidence exists about the barriers and opportunities facing disabled people in the UK, arising specifically from their first-hand knowledge and experience (lived experience), in areas of current policy concern?

This report introduces the lived experience evidence base. It provides a thematic guide to the range and detail of sources in an accompanying database, with links to available evidence sources.

The review focused on research in the UK, at national, regional, or local level. It used both:

- systematic searches of bibliographic databases

- targeted searches of the ‘grey literature’, including research led by disabled people’s organisations

The time frame for the review was from 2010 to 2021, including sources published since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

We discuss the searching, selection and review methods in the second part of this report. The review was conducted in the following 3 phases.

-

We identified around 15,000 potential sources using systematic text searches of databases (mainly academic research), and grey literature searches with a focus on recent user-led research.

-

We developed and applied criteria to select around 1,500 sources from these searches and sorted them into 13 policy-relevant themes.

-

We mapped this evidence base thematically and created the outputs.

The 13 themes are:

- community and social participation

- accessibility

- independent living and social care

- healthcare

- justice

- education

- employment

- income

- housing

- transport

- leisure

- family and private sphere

- stigma and identity

The first theme of community and social participation provides a cross-cutting introduction to disabled people’s experiences of everyday life. It looks particularly at social inclusion in the community, notably during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Accessibility is the second cross-cutting theme that covers experiences in different areas of life. It focuses particularly on the physical environment, communication, and technology. These are then applied in the themes of housing and transport.

Income is the third cross-cutting theme. This is explored through evidence of financial wellbeing and poverty, and experiences of the welfare benefits system.

The themes of leisure, education, employment, healthcare, and independent living and social care show how these concerns affect disabled people’s lives. The final 3 themes focus on stigma and identity, family and private sphere, and justice. The evidence here includes experiences of advocacy, resistance and redress, and disability discrimination, victimisation and violence.

Each theme includes examples of lived experience evidence relevant to either:

- disabled people in general

- different groups of disabled people with shared intersectional experiences, such as certain impairments, ages, or gender or ethnic identities

Many of the recent sources refer to lived experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, either as a focus or in passing.

The review was conducted to align with UNCRPD.[footnote 1] For each theme, we explain the specific context and relevance of the articles in UNCRPD. We then show the range of existing lived experience evidence, with relevant examples and as a basis for further analysis of the research findings.

Findings

Community and social participation

The UNCRPD emphasises ‘participation in the civil, political, economic, social and cultural spheres with equal opportunities’ in all areas of life. It recognises that ‘disability results from the interaction between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinders their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others’.[footnote 2] The lived experience of disabled people provides important evidence about these interactions and how they affect life choices and chances. It also reveals how the agency of disabled people, and policy measures, can make a positive difference.

Broad data on disabled people’s experiences of social participation helps to frame an understanding of their everyday lives. The kinds of evidence identified in the lived experience review, for example, complement the Life Opportunities Survey which established a baseline of understanding about barriers to participation across a range of life areas,[footnote 3] with follow up research conducted,[footnote 4] and secondary analysis carried out.[footnote 5] The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) provided evidence across the major areas of life,[footnote 6] and organisations like Scope researched disabled people’s priorities for change.[footnote 7]

There has also been research on the lived experience of people with different impairments in different parts of the UK. For example, there has been biographical research:

- involving disabled people growing up in England,[footnote 8] and Wales[footnote 9]

- with people with intellectual impairments living in rural Scotland[footnote 10]

- on the participation of disabled children in Northern Ireland[footnote 11]

Such studies have explored both impairment-specific and intersectional experiences. These include those of deafblind people,[footnote 12] children with visual impairments,[footnote 13] disabled Asian women,[footnote 14] disabled people in Gypsy, Roma and Traveller Communities,[footnote 15] or Chinese users of mental health services.[footnote 16]

More than 40 evidence sources identified in the review (3%) referred to the COVID-19 pandemic. These include:

- large scale Office for National Statistics (ONS) research on the social impacts of COVID-19 on disabled people in Great Britain[footnote 17]

- studies of the experiences of adults with learning difficulties,[footnote 18] chronic illness,[footnote 19] and autism[footnote 20]

- regional panel studies in Greater Manchester[footnote 21] and London,[footnote 22] and local or specific group studies

Accessibility

Article 9 of the UNCRPD (Accessibility) recognises that an accessible physical environment, transportation, information and communications, and associated technologies, are needed to enable all disabled people to live independent and equal lives.[footnote 23] It requires attention to ‘the identification and elimination of obstacles and barriers to accessibility’ in all these areas, both by inclusive design and with appropriate assistance and facilitation. Accessibility is an issue that has an effect on many, if not all, areas of life. The evidence of disabled people’s lived experience is therefore relevant not only as a specific focus here but also as a cross-cutting theme in each area of policy concern.

Accessibility is a cross-cutting theme in the evidence base, and relevant sources may also be found in other thematic sections (for example, where accessibility is a factor in experiences of the workplace or in educational settings or when using public transport). The sources identified here have a more specific focus on accessibility but range across different areas of life or policy relevance. These include experiences of physical and social barriers, information and communication barriers, and the accessibility of digital technologies. The latter are highlighted in Article 9 of the UNCRPD and have become more significant to everyday experience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The evidence review identified disabled people’s diverse experiences of encounters with physical and social barriers in a variety of environments. For example, this included studies of the limitations of ‘accessible’ spaces for people with restricted growth,[footnote 24] the accessibility of shops for adults with cerebral palsy,[footnote 25] or the outdoor experiences of people with dementia.[footnote 26] The UNCRPD concept of accessibility includes not only accessibility by design but access by facilitation. For example, the evidence included a report about the access barriers experienced by autistic people and their strategies.[footnote 27]

Experiences of access barriers to information and communication were evident. This included, for example, information formats accessible for people with learning difficulties,[footnote 28] meaningful conversation experiences for people with dementia,[footnote 29] or adolescents’ experiences of communication following acquired brain injury.[footnote 30] The evidence included experiences of the use, or non-use, of assistive technologies at home,[footnote 31] or in transition from institutional care.[footnote 32]

At least 10 sources revealed experiences of using the Internet or computers in general. For example, these included experiences of computer assistive access among young people using alternative communication,[footnote 33] or older people with sight impairment.[footnote 34] There were experiences of the accessibility and usability of websites[footnote 35] and of social media, for example among people with visual impairment,[footnote 36] or learning difficulties.[footnote 37]

The COVID-19 pandemic has intensified the use of remote information and communication technologies in everyday life but also affected access to assistive technologies in the UK and internationally.[footnote 38] The national evidence included studies on the role of technology in supporting people with learning disabilities to remain connected and well,[footnote 39] and experiences of using remote technologies more generally.[footnote 40]

Housing

Article 9 of the UNCRPD (Accessibility) addresses the removal of barriers to accessible housing, along with other aspects of the built environment, which suggests measures to develop and monitor accessibility standards.[footnote 41] Article 28 (Adequate standard of living and social protection) recognises a general right to housing and to improvement of living conditions, including access for disabled people to public housing programmes.[footnote 42] Lived experience evidence is useful in revealing the different kinds of barriers that disabled people encounter in finding suitable housing, including homelessness, as well as experiences of housing support and adaptation.

We identified relatively few evidence sources on these themes, including supplementary targeted searches (N= 54, 4%). The ones we found included substantial studies of high relevance to policy priorities, and a substantial minority by public bodies or relevant non-government organisations (NGOs). There was at least one book length focused study.[footnote 43]

We identified studies evidencing the barriers to housing availability, such research by EHRC,[footnote 44] and using experiential evidence to make the market case for accessibility.[footnote 45] This included user experiences of housing adaptations in Wales,[footnote 46] and letting adapted social housing in Scotland.[footnote 47] There were synergies in research concerned primarily with housing choices and that concerned with supported living arrangements. For example, such studies include the experiences of older people living in sheltered or extra care housing,[footnote 48] or young people with learning difficulties in transition to adulthood.[footnote 49]

There were only a handful of sources evidencing experiences of homelessness or its prevention among disabled people. These included small-scale studies focused on, for example, autistic adults,[footnote 50] people with cognitive impairment using homeless services in Scotland,[footnote 51] or preventing homelessness after discharge from psychiatric wards.[footnote 52] There is some overlap here with themes of justice, such as disabled women’s experiences of seeking housing refuge from gendered violence.[footnote 53]

Transport

Article 9 of the UNCRPD (Accessibility) requires measures to ensure equal access for disabled people to transportation, including the identification and removal of barriers to accessibility. These should include ‘minimum standards and guidelines for the accessibility of facilities and services’ available to the public, along with appropriate training, information, signage and assistance.[footnote 54] Article 20 (Personal mobility) also requires measures to ensure the greatest degree of independence and choice in facilitating affordable mobility (including with mobility aids, devices and assistance). This might include, for example, wheelchair or guide dog assisted mobility or the use of navigation aids.[footnote 55] In addition, Article 30 (Participation in cultural life, recreation, leisure and sport) includes rights to enjoy tourism on an equal basis with others. Lived experience is important in evidencing disabled people’s diverse experiences of travel and transport in different contexts, and the impact of barriers and enablers to accessibility or inclusion.

We found relatively few sources of lived experience evidence primarily concerned with mobility, transport and travel over the past decade (N=41, 3%), although there were examples in each area of policy relevance. Transport and travel related keywords occurred less frequently in titles or abstracts than some other categories. For example, among nearly 1,500 references there were 65 references to ‘transport’, 51 ‘mobility’, 33 ‘travel’, and 20 of wheelchair but fewer than 10 for ‘car’, ‘tourism’, ‘buses’, ‘train’ or ‘rail’. This still seems to imply a rather low representation of sources relevant to transport. This is perhaps surprising, given the well-developed policies and long-standing campaigns by disabled people for greater access to transport since the 1990s. Transport also featured as a theme in important cross-cutting reports identified in our review, such as those by EHRC[footnote 56] or ONS.[footnote 57]

At least 2 reports in the wider participation theme included transport as important themes for analysis, in London[footnote 58] and in Wales,[footnote 59] while a report by the All-Party Parliamentary Group On Loneliness highlighted some groups as facing particular disadvantages in relation to transport and mobility.[footnote 60] There were also examples of transport barriers identified in research that focused on employment but these were rare and came mostly from the grey literature.[footnote 61] None of the sources in this group focused on the COVID-19 context, although a report by Transport for All on Low Traffic Neighbourhoods mentioned it in passing.[footnote 62]

The 41 selected sources covered a wide range of mobility experiences among disabled people. Some focused on the experience of disabled people in general and some on sub-groups, including people with mobility, vision, hearing, language, learning or mental health impairments. This included the travel experiences of groups often under-represented in disability research, such as deafblind people[footnote 63] or people with dyslexia.[footnote 64] Some related to whole journey experiences, to the accessibility of mobility environments or information. Others evidenced more specific aspects, like the experiences of people with autism learning to drive[footnote 65] or disabled women’s access to private transport when escaping domestic violence.[footnote 66] Two sources considered the link between access to toilets and travel experience.[footnote 67] There were least 8 studies focusing on the specific travel experience of wheelchair or scooter users, including for children,[footnote 68] and at least 4 focused on guide dog users.[footnote 69]

Only a small number of evidence sources addressed experiences of public transport specifically. These included, for example, the journey experience of visually impaired people on public transport in London,[footnote 70] or abuse towards young people using public transport.[footnote 71] Among the most significant outputs in the grey literature was an EHRC report on accessible public transport for older and disabled people in Wales,[footnote 72] a report by the Age Action Alliance on overcoming the barriers to access for older people[footnote 73] and Scope’s Travel Fair campaign.[footnote 74]

Income

Article 28 of the UNCRPD (Adequate standard of living and social protection) recognises the right of all disabled people and their families to an adequate standard of living.[footnote 75] It underlines that disabled people have an equal right to social protection. In addition to accessing general poverty reduction programmes, and retirement pensions, this includes specific access to financial assistance from the state with disability-related living expenses (disabled people are at higher risk of poverty if their cost of living is increased by specific expenses). It also refers to aspects of social protection that are addressed elsewhere, for example in relation to housing. Evidence of disabled people’s lived experience is therefore very relevant to understanding financial wellbeing, the management of personal finances and the experience of claiming welfare benefits.

We identified more than 50 sources with a focus on income (4% of sources), most of which included experiences of the UK disability benefits system, such as the impact of benefit assessment or administration processes and welfare reforms on disabled people. Some dealt with the general association between disability and poverty and its impact on daily life,[footnote 76] or with specific aspects such as living with fuel poverty[footnote 77] (including during the COVID-19 pandemic).[footnote 78] Or with specific groups, for example the deprivation experienced by disabled asylum seekers.[footnote 79] They also included everyday experiences of managing money and household finances.[footnote 80]

There were a large number of studies evidencing the social impact of reliance on benefits for income, including mental health experiences of benefit conditionality[footnote 81] and work-related activity.[footnote 82] Several of these targeted experiences of significant changes in benefit rates or processes during the time frame of our review,[footnote 83] for example in the transition from Incapacity Benefit to Employment and Support Allowance,[footnote 84] or from Disability Living Allowance to Personal Independence Payment.[footnote 85] Some focused on benefit assessment processes, including the experiences of people with mental health conditions[footnote 86] or fluctuating health conditions.[footnote 87]

Leisure

Article 30 of the UNCRPD (Participation in cultural life, recreation, leisure and sport) recognises the right of all disabled people to ‘take part on an equal basis with others in cultural life’. This includes access to recreational, leisure and sporting activities, such as theatres, museums, cinemas, libraries or hospitality, for example.[footnote 88] It is also relevant to consider that the right to accessibility and the principle of universal design apply to all products, environments and services to the public, such as shopping and e-commerce services. Understanding disabled people’s lived experience of leisure and recreation is therefore important in revealing the impact of barriers or enablers on their inclusion and equal participation.

We identified many studies relevant to the lived experience of disabled people in these areas (N= 127) and covering a wide range of topics. Most of the evidence reported leisure experiences in mainstream environments and activities.[footnote 89] These covered a wide range of sporting, artistic and cultural pursuits. For example, there were studies of the accessibility of urban cycling,[footnote 90] rural outdoor recreation,[footnote 91] out of school activities,[footnote 92] and museum collections.[footnote 93] Other projects addressed primarily social barriers and inclusion through leisure participation. For example, there were studies of participation in football supporter clubs,[footnote 94] community choirs[footnote 95] and churches, for example.[footnote 96] There were examples of recent studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on isolation and access.[footnote 97]

There was an over-representation of research into the experience of elite disabled athletes compared to more everyday experiences of access to sports. More than 20 studies focused on the identity experiences of competitive athletes,[footnote 98] including individual Olympic athletes.[footnote 99] There were also examples of the role modelling effects of elite performance (for example, for other young disabled people)[footnote 100] and critical perspectives on this.[footnote 101]

A similar proportion of sources focused on disabled people’s participation in leisure activity, including arts and sport, as a therapeutic intervention with social benefits (we also excluded many studies that reported therapeutic benefits only in terms of impairment functioning). These ranged from experiences of trying to remain active through chronic illness[footnote 102] to keeping occupied through leisure time in segregated environments, such as care homes.[footnote 103] Some of these focused on forms of activity modified for specific groups of disabled people, such as community-based group exercise sessions for stroke survivors,[footnote 104] or walking football for people with dementia.[footnote 105] Although intervention focused, such sources reflected on experiences of leisure participation and addressed disabling social barriers as well as health benefits.

Education

Article 24 of the UNCRPD (Education) recognises the right of all disabled persons to education, at all levels, without discrimination. It requires that disabled people are ‘not excluded from the general education system on the basis of disability’ and that reasonable adjustments and support are provided to accommodate individual learning needs, including specific support for blind, deaf or deafblind learners.[footnote 106] The lived experience of disabled children and adults is an important form of evidence in identifying the barriers that exist, their educational and social consequences, and what works for disabled learners in different contexts, including schools, colleges and universities.

Educational experiences were well represented in the evidence review overall (N=126, 9%), but more experiential studies focused on further and higher education than on schooling. Most of the evidence focused on mainstream education settings, with only 7 studies focused on segregated settings. There was evidence from primary and secondary schools, including sixth form and college education, but no evidence was found about the direct experience of young disabled children in early years education or nursery education. There was more impairment specific research in the education field than in the other policy themes, notably studies focused on pupils with dyslexia, autism or visual impairment.

Primary experiences included, for example, children’s views on teaching assistant support,[footnote 107] barriers to tests and exams,[footnote 108] or transition to secondary level.[footnote 109] There were also studies targeting the everyday experiences of inclusion for certain groups of children, such as autistic[footnote 110] or deaf pupils.[footnote 111] Secondary experiences also included the views of pupils with special education needs and disabilities (SEND) on inclusion practices,[footnote 112] and for specific groups such as those with hearing impairment[footnote 113] or dyslexia.[footnote 114]

Experiences of higher education covered all stages, including application,[footnote 115] support in studying,[footnote 116] socially integrating,[footnote 117] administrative process,[footnote 118] or assessment.[footnote 119] They included attention to issues of accessibility, discrimination, inclusion, and academic performance. They also included studies focused on the specific experiences of students with dyslexia, autism, visual impairment, and deaf students, as well as more diverse student samples. A significant number of these studies (at least 16) reported the experiences of disabled university students in nursing, medicine or social care disciplines. These included, for example, the experience of nursing students using sign language,[footnote 120] with dyslexia,[footnote 121] or of blind physiotherapy students.[footnote 122] In these kinds of professional education there was often a specific focus on placement experiences or fitness to practice.[footnote 123]

Employment

Article 27 of the UNCRPD (Work and employment) recognises disabled people’s right to work on an equal basis with other people in the open labour market (rather than in segregated settings).[footnote 124] This applies in all respects of employment, from recruitment to career progression, and in self-employment. It includes equal opportunities in working conditions, remuneration, training and work experience. It requires appropriate ‘assistance in finding, obtaining, maintaining and returning to employment’, as well as ensuring that reasonable adjustments are provided in the workplace. Disabled people’s lived experiences are important sources of evidence about the barriers and enablers to work and employment, transitions into work, the challenges encountered in specific professional contexts, and what works in supporting employment.

The review of recent lived experience evidence identified 130 sources primarily relevant to employment (9%). These included diverse experiences of working, barriers and enablers to employment, transitions in and out of work, and studies of certain occupations or entrepreneurship. They included disabled people’s attitudes to employment, its meaning in their lives and the way in which it affects their identity. Some experiences of using technology related to employment may also be found under the theme of accessibility.

Around one-quarter of the sources focused on barriers to disabled people’s employment, although most paid some attention also to enablers that could help disabled people enter or remain in employment. For example, this included EHRC research on disabled people’s views on making workplaces more inclusive.[footnote 125] Some recognised wider factors affecting paid employment chances, such as educational attainment, housing tenure, or multiple impairment.

Among the social barriers there was, for example, evidence of stigma experienced at work by people with facial disfigurements,[footnote 126] with a psychiatric diagnosis,[footnote 127] sickle cell disease[footnote 128] or dyslexia.[footnote 129] Cultural barriers in the workplace, such as presenteeism,[footnote 130] featured in the experiences of people with long term and fluctuating health conditions, like back pain[footnote 131] or mental health conditions. This was relevant also to experiences of disability disclosure in the workplace.[footnote 132]

There were 15 sources examining return to work. These included both general and impairment-specific experiences, for example of people with mental health conditions,[footnote 133] or chronic pain.[footnote 134] The remaining 7 sources examined specific return to work initiatives, including Workstep and Remploy. There were 7 studies involving the transitions of young people towards employment.

Among the enablers to work, there were experiences of:

- opening up disability conversations at work[footnote 135]

- using personal assistance[footnote 136]

- software provision[footnote 137]

- the role of trade unions as facilitators for disabled employees[footnote 138]

Some studies reported user experiences of labour market support policies and schemes.[footnote 139][footnote 140] Experiences of employment support schemes focused mainly on people with learning disabilities or people with mental health conditions. There were also some experiences of marginal work outside the open labour market, such ‘job clubs’ for people with learning difficulties,[footnote 141] or experiences of volunteering as a route into work.[footnote 142]

Around 30 sources reported the experience disabled people have in specific professions. Nine of these focused on disabled professionals in the healthcare system, for example as doctors,[footnote 143] occupational therapists[footnote 144] or dentists.[footnote 145] Five papers reported experiences of disabled people employed in higher education.[footnote 146] Other papers included the experiences of disabled teachers, legal professionals and accountants. Two papers reported on an internship programme for autistic graduates in the banking sector. By contrast, there was less evidence about the specific work experiences of disabled people in non-professional, lower paid or insecure occupations.

Only one study in the employment group had an explicit focus on COVID-19. This was an academic paper reporting the National Association of Disabled Staff Networks observations about the lived experiences of disabled people during the COVID-19 pandemic.[footnote 147]

Health

According to Article 25 of the UNCRPD (Health) disabled people have the same rights as other persons to ‘the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health without discrimination based on disability’.[footnote 148] They should have access to ‘the same range, quality and standard’ of health care, as well as impairment-specific health care, and they should be able to access these services as close as possible to their own community. Treatment should be based on informed consent and there should be no discrimination or denial of provision on grounds of disability. Evidence about disabled people’s lived experience of health and care is therefore important in understanding the reality.

From a policy perspective, health and social care are increasingly considered as a combined category, as reflected in the re-branding of the Department of Health and Social Care.

A relatively large proportion of academic sources identified in the review reported experiences relevant to health or healthcare (N= 160, 12%), even after excluding exclusively medical interventions from the search. These sources ranged widely from disabled people’s health care choices and access, including communication barriers, to experiences of mental health care and hospitals, health inequalities and health promotion, and intersectional experiences. Inequalities of access are widely evidenced in self-reported data.[footnote 149]

Many of the sources related to access and barriers to accessing acute or long-term healthcare. These included disabled people’s experiences of accessing reasonable adjustments in hospital,[footnote 150] including a study by Mencap asking 500 people with learning disabilities about their experiences. There were experiences of negotiating hospital practices,[footnote 151] as well as in-patient experiences of isolation,[footnote 152] locked wards[footnote 153] or segregated seclusion.[footnote 154] Some of these experiences overlap with policy themes on justice.

There were also experiences of community-based health care.[footnote 155] Most of these studies focused on mental health services. Four studies considered experiences of dental care,[footnote 156] 3 of which focused specifically on adults with learning difficulties. At least 10 sources focused on experiences of cancer including, for example, evidence about the attitudes of women with learning difficulties to cancer screening,[footnote 157] access to treatment for people with physical impairments,[footnote 158] or experiences of palliative care.[footnote 159] Several of the sources included intersectional experiences of disability and ethnicity in relation to healthcare, again often in relation to mental health difficulties.[footnote 160]

Among the evidence on barriers there was a strong focus on communication barriers. Such studies included, for example, access to pharmaceutical care for older people with sensory impairment in Scotland,[footnote 161] providing accessible information in memory services,[footnote 162] or listening to the views of children with learning disabilities.[footnote 163] The evidence on health inequalities and health promotion focused almost exclusively on people with learning disabilities, for example in relation to healthy lifestyles, eating and weight, or tobacco and alcohol use.[footnote 164] Four studies dealt with healthcare experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. These included issues of GP access, vaccination,[footnote 165] and the role of self-advocacy groups in supporting health and wellbeing.[footnote 166]

Social care and support

Article 19 of the UNCRPD (Living independently and being included in the community) recognises the right of all disabled people ‘to live in the community, with choices equal to others’.[footnote 167] They should be able to choose ‘where and with whom they live’ and not be limited in that choice more than other people. They should have access to a range of services ‘to support living and inclusion in the community, and to prevent isolation or segregation from the community’, including access to personal assistance services. Evidence about disabled people’s lived experience of seeking access to support, using support services, and of the impact on their lives is therefore particularly relevant.

In policy terms, the broad topic of independent living is often framed in terms of ‘social care’ although its achievement in practice depends on equal access to all kinds of community services, housing, transport and so on.

A relatively large number of sources were identified in the review relevant to these themes (N= 158, 11.5%). They included experiences of choice and decision making in everyday life, as well as experiences of using long-term care and support services. There were experiences of institutional care, transitions to community-based supported living, self-direct support (including direct payments for personal assistance) and peer-to-peer advocacy for independent living.

There were around 20 sources addressing choice and control in independent living in terms of personalisation, at least 10 of which addressed personal budgets directly.[footnote 168] The evidence included experiences of managing choice,[footnote 169] transitioning from institutional care to personalised arrangements,[footnote 170] or the perceived benefits of such arrangements.[footnote 171] There were also studies focused on relationships with personal assistants,[footnote 172] for example among LGBTQI+ disabled people,[footnote 173] or people with learning difficulties.[footnote 174] It also included the experiences of disability activists[footnote 175] and disabled people’s organisations in promoting and supporting independent living solutions.

More than one-third of the evidence sources (N= 57) reported experiences of social care that was not explicitly self-directed, such as short-break services for disabled children,[footnote 176] home care visits,[footnote 177] or shared life communities.[footnote 178] Studies used disabled people’s experiences to evaluate specific services, to explore user involvement in service design, or continuity of care through ageing transitions. Several studies focused on relationships with staff,[footnote 179] whether in the context of service provision[footnote 180] or as social networks.[footnote 181]

There was also evidence about the experiences of disabled people living in residential group care settings, and about deinstitutionalisation. For example, this included the experience of older people with high support needs living in care homes,[footnote 182] in end-of-life care,[footnote 183] in group homes for people with severe intellectual impairment,[footnote 184] or with spinal injuries.[footnote 185] There was one example of experience in care homes during the COVID-19 pandemic.[footnote 186]

Family and friends

Article 23 of the UNCRPD (Respect for home and the family) recognises the equal right of all disabled people to live without discrimination ‘in all matters relating to marriage, family, parenthood and relationships’.[footnote 187] This includes the right to marry, to decide whether to have children, with access to appropriate information and education about these things. It requires appropriate assistance for disabled people in parenting roles and ensuring that families are not separated against their will on grounds of disability. Article 22 (Respect for privacy) also protects against arbitrary interference with a person’s ‘privacy, family, home or correspondence’, which is relevant to equality of rights in forming and maintaining consensual sexual relationships, as well as friendships and family relationships. Evidence of disabled people’s lived experience across this range of relationships, and the impact of interference or barriers to them, is relevant to monitoring the realisation of this right.

We selected 159 sources of evidence relevant primarily to family, friendships and personal relationships (11.5% of the total). We divided these into 4 sub-groups, reflecting experiences of couple and family relationships, friendships and loneliness, parenting roles or sexual relationships (including experiences of sexuality and gender).

Some of the research considered experiences of disruption and continuity in close personal relationships following impairment onset in later life, for example within married couples after a stroke.[footnote 188] Some evidence of this type was excluded where it adopted only an individual rehabilitation approach or considered only the experience of family carers, while studies of reciprocal family caring roles were included,[footnote 189] notably where the focus was on disabled people as carers.[footnote 190] Likewise, the selection included disabled people’s experiences of family bereavement.[footnote 191] The emphasis here was on experiences of companionship. We included more than 30 evidence sources relevant to friendships and loneliness that included the experiences of disabled people, not all of which were disability specific in focus.

Only one recent study focused on sibling relationships from the perspective of disabled people,[footnote 192] but many studies from the perspective of siblings of disabled people were excluded (as they did not report disabled people’s first-hand experience). By contrast, we included more than 50 sources of evidence about the experience of disabled people as parents. This included social experiences of pregnancy and parenting, including some relevance to access to healthcare during pregnancy. It included the experiences of disabled parents subjected to child protection proceedings and of social support for their parenting role. It included disabled people’s views on reproductive rights and genetic screening. Most studies focused on the experiences of mothers but at least 8 addressed those of fathers.[footnote 193] Most were specific to experiences of people with learning difficulties or mental health conditions.[footnote 194]

There were some experiences of romantic love and relationship forming, for example among people with learning difficulties,[footnote 195] but there was more evidence about experiences of sexual identity and sexual relationships.[footnote 196] We selected more than 40 such sources reflecting a wide range of experiences.[footnote 197] This included experiences of sex, sexuality, gender and gender identity, sex surrogacy, sexual health and sex and relationship education (the latter was included here rather than under education). Some focused on the experiences of women, either with physical impairments[footnote 198] or learning difficulties,[footnote 199] and several on the experiences of gay[footnote 200] or bisexual people,[footnote 201] including young people.[footnote 202] Included within this sub-group were experiences of barriers to sexual relationships,[footnote 203] including the regulation of sexual relationships in care settings.[footnote 204] It includes intimate aspects of sexual relationships, as well as gender and gender identity and, LGBT+.

Attitudes

Article 8 of the UNCRPD (Awareness-raising) requires action to raise awareness, to ‘combat stereotypes, prejudices and harmful practices’ and to ‘promote awareness of the capabilities and contributions’ of disabled people in society.[footnote 205] This includes the promotion of positive attitudes and respect in education and in media coverage. Social perceptions and attitudes can have an effect on disabled people’s choices and chances in life, on their everyday life experiences and on their own self-identity. Disabled people’s lived experiences provide an important insight into the attitudes they encounter in everyday life and how this affects their life choices as well as self-perceptions.

We identified evidence about disabled people’s experiences of other people’s attitudes, feelings of stigma, and about self-identity (N= 77, 6%). Some of these sources evidenced how perceived stigma may affect willingness to seek help and access support services. For example, there were several studies of mental health-related discrimination as a predictor of low engagement with mental health services,[footnote 206] including intersections with racism.[footnote 207] While mental health underpinned more studies than any other impairment group, there was also evidence about the discrimination experienced by disabled people in general,[footnote 208] and bullying experienced by adults with learning difficulties,[footnote 209] or disabled school students.[footnote 210] At least 6 studies were based on research with people with autism.[footnote 211]

Some papers included experiences of resistance to discriminatory attitudes,[footnote 212] or the construction of positive counter-narratives about disability.[footnote 213] These included studies of self-advocacy as means to positive disability identity,[footnote 214] or of anti-stigma campaigns.[footnote 215] Other sources focused on negative experiences of internalised stigma or internal struggles with self-identity based on experiences of disability. They also included experiences of negotiating disability appropriate terminology,[footnote 216] labelling[footnote 217] and language.[footnote 218]

Some of the experiences identified in this section point to behaviours, such as bullying, that are further addressed as experiences of hate crime under the theme of justice.

Justice

Article 13 of the UNCRPD (Access to justice) ensures that disabled people have equal access to justice as other persons, including appropriate adjustments to legal process and proceedings.[footnote 219] Other Articles of Convention are also very relevant to considerations of violence and abuse. Article 16 (Freedom from exploitation, violence and abuse) also requires the state to protect disabled people ‘both within and outside the home, from all forms of exploitation, violence and abuse, including their gender-based aspects’. This includes the provision and monitoring of ‘gender- and age-sensitive assistance and support’.[footnote 220] Lived experience research is an important source of evidence in understanding disabled people’s encounters with violence and crime, and in monitoring the implications of different forms of support and intervention, or the lack of them.

We identified 118 sources of evidence relevant to these themes (9%). More than half of these sources dealt in some way with experiences of violence and most of the remainder reported the experiences of disabled people as perpetrators. A few discussed access to justice in ways that could apply to either those who have been targeted or those who have offended. There were cross-cutting experiences in terms of reasonable adjustments for sign language users in Northern Ireland,[footnote 221] witnesses with learning difficulties,[footnote 222] or autistic adults in family courts.[footnote 223]

Experiences of crime and violence included child abuse,[footnote 224] domestic and intimate violence,[footnote 225] hate crime and bullying.[footnote 226] There was rather more evidence about gendered violence against disabled women (N= 25) than against disabled children (N= 5). They often included experiences of using women’s refuge and support services[footnote 227] or strategies for avoiding or dealing with such violence.[footnote 228] Many of these studies reported the experiences of women with learning difficulties or mental health service users. There was evidence of cyber-victimisation,[footnote 229] and at least one study about online safety and radicalisation.[footnote 230]

At least 10 papers reported experiences in a context of adults subject to safeguarding. For example, these included explorations of choice and risk,[footnote 231] the experience of being protected,[footnote 232] and user involvement in safeguarding.[footnote 233]

A large portion of the evidence reported the experiences of disabled people accused of offending, including experiences in the justice system and as prisoners. Some of these experiences related to ‘challenging behaviour’ and violence in care settings,[footnote 234] including secure settings. Others included experiences of adapted treatment programmes, for example among men who had sexually offended.[footnote 235] At least 25 papers referred to prison, including the experiences of both male and female prisoners, with a range of different impairments and health conditions. Several of these sources addressed broad prison populations in which disabled people were a part of (with an emphasis on mental health, for example). Others were more targeted, such as to prisoners with learning difficulties,[footnote 236] or deaf prisoners.[footnote 237]

There were no references to experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in this grouping.

The methods: searching, screening and reporting

The wide scope of the review question, and the time available to complete it, required some interpretation in design. Systematic reviews can be resource intensive and can take more than a year to complete.[footnote 238] Guidelines suggested that a rapid evidence assessment method might be more suited to the available resources.[footnote 239] This was the method used in a previous evidence review for the Office for Disability Issues in 2009. We wanted to retain important features of systematic review that might be lost in such an approach.[footnote 240] In particular, we used systematic searching and screening techniques to find potential sources in the scientific literature.

Due to the focus on lived experience, we targeted mostly qualitative evidence. Synthesis and analysis of such material needs to be approached in a manner that can accommodate its richness. We therefore conducted a review that drew on elements of 4 methodological traditions:

- systematic review

- systematic search and review

- qualitative systematic review

- systematised review[footnote 241]

This approach is summarised in Table 1 and described in more detail later.

Table 1: Interpretation of systematic review method

| Typical systematic review | Our approach |

|---|---|

| Phase 1: Search aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | Method 1: Systematic search of library databases exhaustive, comprehensive searching Method 2: Targeted call for evidence Method 3: Additional grey literature search: selective purposive sampling |

| Phase 2: Appraisal: Quality assessment may determine inclusion or exclusion | No change: Quality assessment may determine inclusion or exclusion |

| Appraisal: Quality assessment is conducted independently by 2 separate reviewers | Quality assessment conducted independently by 2 separate reviewers on a small sample of sources (2% of initial search items, n = 277). |

| Synthesis: Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | Mostly qualitative, narrative synthesis with tabular accompaniment |

| Phase 3: Analysis: What is known, recommendations for practice. What remains unknown, uncertainty around findings, recommendations for future research | Thematic, descriptive overview of the evidence and identify gaps, highlighting what is known. What remains unknown, uncertainty around findings, limitations of methodology and scope for future research. |

The research was conducted in 3 phases:

Phase 1: Identification of potential sources

To synthesise the full breadth of research in this area we had to begin by identifying potential sources. We did this using 3 methods:

- systematic search of library databases (primarily academic research)

- targeted call for evidence, inviting nominations from other researchers and stakeholder communities, gathered through an online tool

- additional grey literature search with a focus on recent user-led research

Phase 2: Developing and applying criteria for eligibility, robustness and policy relevance of the identified sources

This involved:

- refining the conceptual framework developed for searching

- rapid screening of a large dataset for eligibility

- second screening for robustness

- categorising the selected sources into relevant themes

Phase 3: Finalising the outputs

These included:

- producing a structured data library of selected sources and thematic bibliography

- archiving and writing up a comprehensive account of methods to help with future updates and development

- providing a thematic overview of the evidence and identification of evidence gaps

In our searches, we identified nearly 15,000 possible sources of evidence. These were reduced to under 1,400 items through screening and review stages. Table 2 summarises these inclusion decisions, which are explained and discussed in more detail later.

Table 2: Overview of inclusion decisions

| Included | Maybe | Excluded | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Search (Phase 1) | 14,696 | ||

| Screen (Phase 2) | 1,438 | 368 | 12,888 |

| Review (Phase 3) | 1,344 | 94 | |

| Final review and reporting | 1,380 |

Phase 1: Identification of potential sources

The aim of phase 1 was to use systematic and targeted approaches to search the full breadth of research about the lived experience of disabled people in the UK since 2010. We identified potential sources using:

- a systematic search of library databases

- a public call for evidence

- a targeted search of grey literature

Developing criteria for a literature search and selection is an integral part of the systematic review method. The PICO model (population, intervention, comparison and outcomes) is often used as a starting point. A more qualitative version of this model can be expressed as PICo (population, interest, context). Applying this typology, we defined our initial search strategy as follows:

Figure 1: PICo search strategy

Population = disabled people in the UK

and its constituent countries

including people of all ages

with different types of impairment

who may be diverse in terms of gender, ethnicity, etc

Interest = first-hand knowledge

from research that seeks out their experiences explicitly

and reports it directly

but may involve mediation by others

Context = areas of current policy concern as indicated by the research brief

and to national implementation of the UN Convention

Other models, such as SPIDER (sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, research type)[footnote 242] emphasise the relevance of the research method, which was significant due to our focus on qualitative experience. For this reason, we also defined search criteria to prioritise studies using qualitative methods (while not excluding quantitative evidence of relevant lived experiences).

A significant challenge in disability research is that systematic searching identifies many academic studies that are high in scientific quality but low in relevance to the policy problem. This is particularly the case in studies that treat disability as an individual rather than a social concern (often in medical, therapeutic, or psychological literature). Such studies may report on the ‘lived experiences’ of disabled people but often these are experiences of impairment or health (pain, discomfort, functioning, psychological adjustment) rather than experiences of inclusion or exclusion. We needed to have an open approach to searching but applied selection criteria to address this. This resulted in a high exclusion rate at the screening stage (as explained later).

An opposite problem in the grey literature is that there are many studies of high policy relevance which do not have evidence of traditional quality assurance measures (for example, academic peer review). These include local or national studies led by disabled people and their organisations, commissioned specifically to report on lived experience in areas of high interest for this review. A typical approach to quality criteria in systematic reviews would risk excluding some of the most relevant pieces of work. We sought to identify such studies beyond systematic searching in the academic literature by using targeted internet searches or expert nominations.

Searching for disability terms

The concept of disability (and disabled people) is contested, with an underlying tension between individual or medical model and social model approaches. While UK public policy now adopts broadly social model language, public data is often framed by an individual model of disability in which impairments rather than disabling barriers are analysed. Under the Equality Act 2010 or the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 Northern Ireland, a person is considered to be disabled if they have a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on their ability to do normal daily activities.[footnote 243] This means that disability may be unwittingly conflated with impairment in data definitions.

The UK census asks the question: ‘Are your day-to-day activities limited because of a health problem or disability which has lasted, or is expected to last, at least 12 months?’

For the purposes of policy evidence, the UK government seeks to harmonise data in line with the UK Census, which asks respondents: ‘Are your day-to-day activities limited because of a health problem or disability which has lasted, or is expected to last, at least 12 months?’. This is broken down into sub-categories of impairment as follows (with examples of activity limitation) as shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Harmonised categories of impairment used in UK government data

| Impairment categories |

|---|

| 1. Vision (for example blindness or partial sight) |

| 2. Hearing (for example deafness or partial hearing) |

| 3. Mobility (for example walking short distances or climbing stairs) |

| 4. Dexterity (for example lifting and carrying objects, using a keyboard) |

| 5. Learning or understanding or concentrating |

| 6. Memory |

| 7. Mental health |

| 8. Stamina or breathing or fatigue |

| 9. Socially or behaviourally (for example associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) which includes Asperger’s, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)) |

| 10. Other (please specify) |

The difficulty from a social model perspective is that an impairment-led definition implies that personal characteristics (impairments) rather than social factors (barriers) are the limiting factors in people’s lives. Acknowledging this, the UN Convention says that:

‘Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others’ (Article 1)

We resolve this by searching for evidence of the lived experience of ‘people with impairments’ in their encounters with disabling barriers. Our strategy was:

- first, to search for studies providing evidence about the lived experience of people with impairments

- second, to screen these sources for evidence about interactions with barriers, or enablers, to full participation and equality in relevant policy areas

We considered these conceptual issues and policy definitions when we developed our initial keyword terms for the disability or impairment dimension of our systematic search protocol. We also considered the terminology and typologies offered by:

- UN Washington Group on Disability Statistics (short set and long set questions)[footnote 244]

- WHO International Classification of Functioning (ICF)[footnote 245]

- WHO Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 (WHODAS 2.0)[footnote 246]

The contingencies of adapting such tools to systematic review protocols have been explored by others. These have led to the conclusion that a relatively limited range of general disability or impairment terms may be more efficient than a long list of specific impairment conditions in balancing sensitivity with specificity. For example, Walsh and others[footnote 247] tested the following keywords across databases:

- functional limitation

- activity limitation

- mobility impairment

- vision impairment

- hearing impairment

- cognitive impairment

- intellectual disability

- participation limitation

But many sources referring to specific conditions are not found in such searches.[footnote 248] The purpose of the review is relevant here, as it requires specificity to policy-relevant experiences of disability in everyday life but is not directly concerned with experiences of impairment or treatments for health conditions (other than fair access to health services).

Our primary search terms focused on the intersection of 2 concepts — disability and lived experience. We used established bibliographic subject headings, where available, and text terms for the target concepts. Scoping searches indicated that searching general terms on disability would not identify all the relevant literature, so we added more specific search terms around functional categories of impairment and medical labels associated with disability. This increased the identification of non-relevant studies but retained some important studies of interest (for example, searching for terms connected with autism or blindness identified relevant studies that were not found with generic disability terms).

As qualitative research methods are strongly associated with research into lived experiences, we also used qualitative search terms and relevant subject headings to identify relevant research. Search strategies that included filters, where available, were used to target publications associated with the UK (for example, in relation to author institutional affiliation) or by use of well-established keyword criteria. A date limit of 2010 onwards was applied to the search. No language restrictions were applied but the search terms were not translated into other languages and no relevant results in languages other than English were included.

Systematic searching of bibliographic databases

We began by searching the following 10 health and social science databases. The precise definition of terms in our search strategy for each database is itemised in Annex A.

- Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)(ProQuest) from 1987

- APA PsycInfo (Ovid) from 1806

- CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (Ebsco) from 1981

- HMIC Health Management Information Consortium (OVID) from 1983

- MEDLINE (ALL) (Ovid) from 1946

- Scopus (Elsevier B.V.) from 1823

- Social Care Online (SCIE) from 1980

- Social Work Abstracts (EBSCO) from 1965

- Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest) from 1925

- Web of Science. Social Sciences Citation Index Expanded (Clarivate) from 1900

We made 3 supplementary searches to identify additional evidence in specific policy areas where there were few results from the initial search.

These included:

- disability and homelessness or housing

- disability and transport

- disability and domestic violence

For these we searched the following databases with additional search terms (see Annex A):

- Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)(ProQuest) from 1987

- Web of Science. Social Sciences Citation Index Expanded (Clarivate) from 1900

- Web of Science, Science Citation Index Expanded (Clarivate) from 1900

- Web of Science, Emerging Sources Citation Index from 2015

- Social Care Online (SCIE) from 1980

- Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest) from 1925

- Web of Science. Conference Proceedings Citation Index- Science (SSH) (Clarivate, Web of Science) from 1900

- Web of Science Conference Proceedings Citation Index- Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH Clarivate. Web of Science) from 1900

From these searches we identified 33,735 results, of which 20,132 remained after initial deduplication. These were imported to NVivo reference management software and further deduplicated.

Targeted searches of grey literature

We targeted relevant studies in the grey literature, including a focus on studies conducted by or in partnership with disabled people. This included 33 projects commissioned as part of the DRILL UK research programme, in which Disability Rights UK was a co-ordinating partner with Disability Action Northern Ireland, Disability Wales and Inclusion Scotland.[footnote 249] We also searched the research project and publications sections of relevant organisations, such as:

- Disability Wales

- Equality and Human Rights Commission

- Equality Commission for Northern Ireland

- Inclusion Scotland

- Mencap

- MIND

- National Autistic Society

- Scope

- Scottish Learning Disabilities Observatory

- Shaping Our Lives

We launched a public call for evidence that invited nominations from other researchers and stakeholder communities. We used online surveys to create a form to collect data into a structured format that could be integrated with our sources from systematic searches.[footnote 250] We distributed this call through the networks of the Centre for Disability Studies, and Disability Rights UK. We entered results from our own targeted searches into the same dataset. We checked attributes of:

- geographical focus (jurisdiction)

- impairment focus (harmonised reporting standards)

- gender focus

- generational focus

- ethnicity or racism focus

- method of data collection

- number of respondents

- quality control

Due to commissioning and peer review processes, academic publication often takes longer than research published in the grey literature. This was a potential limitation when prioritising recent lived experiences relating to the COVID-19 pandemic. It was also evident that scientific publishing processes had been accelerated for many COVID-19 related papers. Several consultations or studies had been conducted by disabled people’s organisations and charities.

In summary, our targeted searches focused on sources of:

- user-led lived experience research since 2010 that might be missed by academic literature searches

- relevant lived experience research conducted since March 2020, and particularly in relation to COVID-19

The survey was open for 2 months and we collected 104 items for review. The data was combined in the online submission tool, screened and combined with the bibliographic library of sources generated from the systematic searches (using EndNote reference management software).

Phase 2: Development and application of screening criteria

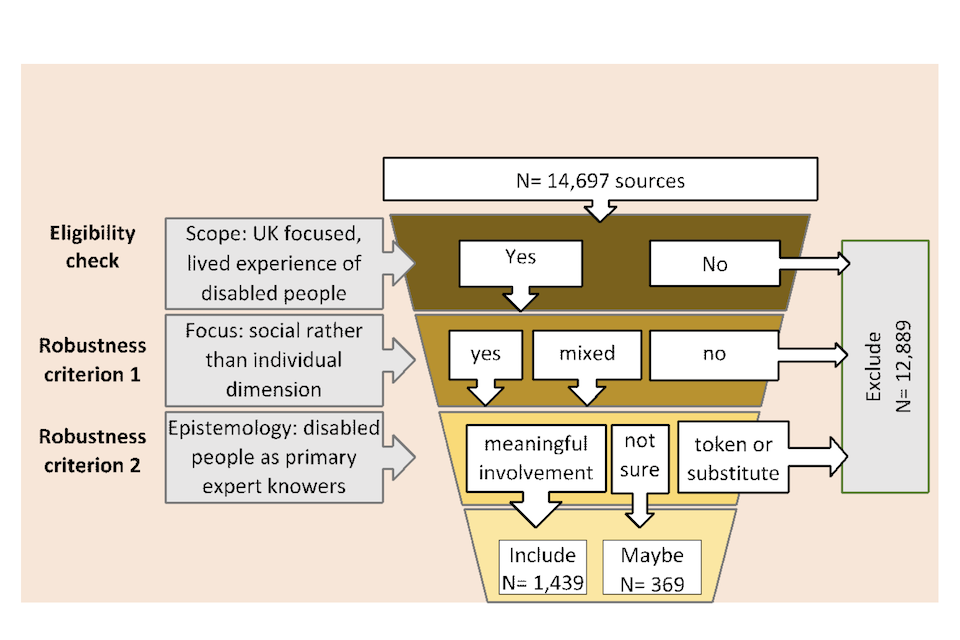

In the second phase we refined our criteria for testing the robustness of the evidence in relation to the research brief and the initial search criteria, by screening the combined library of sources (N= 14,697). Figure 2 summarises the process and outcomes of this initial screening. Further review and selection were also completed at the final stage of the research.

Figure 2: Applying criteria for inclusion

Image description: A flowchart showing the screening process for selecting sources related to the lived experience of disabled people in the UK. The process starts with 14,697 sources. There are 3 stages. The first stage is an eligibility check to make sure the sources focused on the lived experience of disabled people. The next 2 stages assess the robustness of the sources by checking whether the focus is social rather than individual, and if disabled people were treated as primary expert knowers and had meaningful involvement rather than being involved as token or substitute. Based on this, 12,899 sources were excluded. 1,439 sources were included and 369 marked as maybe.

We used Rayyan online screening software, which is designed for collaborative systematic review techniques.[footnote 251] This allows for screening decisions to be made by multiple reviewers using a traffic light system (Yes, Maybe, No). Two researchers reviewed approximately 2% of the sources independently (N= 277) and then met to compare and discuss their decisions, and to resolve conflicting decisions or uncertainties arising in the category of ‘Maybe’. The reviewers then applied these agreed decision principles to the remaining dataset, dividing rather than duplicating the work and with further discussions to moderate difficult decisions. Because of this, the process of initial screening was rapid but systematic in approach.

These initial screening decisions were made mostly in the order shown in Figure 2 – focusing on eligibility before consideration of robustness or relevance. We excluded 88% of identified sources at this stage (N= 12,889) and included 10% (N= 1,439) with 2.5% (N= 369) classed as Maybe. Those classed as Maybe were later discarded, in consultation with Disability Unit staff. There was a high degree of agreement in the initial rapid screening stage.

The large proportion of excluded items were either:

- non-UK studies

- about the experiences of non-disabled people (for example, professionals or family members)

- about individualised impairment experiences without a disability policy dimension (for example, reporting on the effectiveness of a specific pain management therapy rather than the socio-economic consequences of living with chronic pain)

Eligibility decisions

We were able to make rapid exclusion decisions when papers did not meet basic inclusion criteria. These are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4: Examples of eligibility exclusion criteria

| Exclusion criterion | Notes |

|---|---|

| Non-UK research | International studies spanning several countries were included if the UK was one of them |

| Research not concerned with disabled people explicitly | Research with relevant populations but where disability was mentioned in a population but not explicitly invoked in findings (for example, in research about young people in the care system). |

| Methodological papers | Reporting methods of research on the lived experience of disabled people but not reporting that experience as findings (for example, reviews of interview methods or research review protocols) |

| Lacking evidence of lived experience | Such as conceptual papers, or descriptions of an intervention |

| Reporting only the lived experience of others | Reporting the experience of other persons (for example, professionals, parents, siblings, carers) |

| Second-hand accounts | Testimony of other persons about the experience of disabled people was excluded, unless explicitly mediating communication by a disabled person |

| Research about general wellbeing rather than disability | Papers identified under the search term ‘mental health’ that focus on everyday wellbeing or distress but without reference to people with long-standing mental health conditions or mental health service usage (whose condition has not lasted, or is expected to last, at least 12 months). |

These preliminary exclusions were made by reading titles and abstracts alone. For example, a study was excluded if the title indicated that it took place in Ghana rather than the UK. If there was no information about the location of the research, it was retained for further review. For this reason, we retained some non-UK studies after Phase 2 that were excluded later. We conducted some author affiliation checks where the spelling or wording of the title or abstract suggested that the study might be non-UK. For example, a Swedish study ‘Mutual Care Between Older Spouses with Physical Disabilities’ was filtered after the author’s institutional affiliation was confirmed online (considering that ‘physical impairments’ or ‘disabled people’ are more commonly used in UK publications than ‘physical disabilities’). But similar wording was used by UK authors conforming to preferred language use in American journals, for example.

Excluding by non-UK authors institutional affiliation may have resulted in a small number of relevant studies being wrongly excluded (for example, where an author had moved institutions or conducted their research on a visit to the UK). But the large majority of such sources will have been retained by default for review. Around a dozen papers spot-checked in this way were confirmed to be non-UK.

Table 5 and Table 6 provide further examples of titles and abstract texts that led to rapid exclusion decisions, based on the criteria outlined earlier in Table 4.

Table 5: Examples of titles that led to rapid exclusion decisions

| Example title | Exclusion reason |

|---|---|

| ‘Activities and participation of children with cerebral palsy: parent perspectives’ | No disabled people’s perspectives |

| ‘Factors affecting staff morale on inpatient mental health wards in England: A qualitative investigation’ | No disabled people’s perspectives |

| ‘Framing the Paralympic Games: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Spanish Media Coverage of the Beijing 2008 and London 2012 Paralympic Games’ | No disabled people’s perspectives |

| ‘ADHD symptoms and pain among adults in England’ | Focus on impairment effects |

| ‘The development of a prison mental health unit in England: Understanding realist context(s)’ | Focus on an intervention |

| ‘Socialist Utopia in Practice: Everyday Life and Medical Authority in a Hungarian Polio Hospital’ | Not UK |

| ‘Socio-demographic, mental health and childhood adversity risk factors for self-harm and suicidal behaviour in College students in Northern Ireland’ | Exploring causation of potential impairment (mental health difficulties) |

| ‘Web-based physiotherapy for people affected by multiple sclerosis: a single blind, randomised controlled feasibility study’ | Focus on an intervention |

Table 6: Examples of abstract text that led to a rapid exclusion decision

| Title | Religion, spirituality and personal recovery among forensic patients |

| Abstract | […] ‘Findings: Three superordinate themes were identified: “religion and spirituality as providing a framework for recovery”, “religion and spirituality as offering key ingredients in the recovery process”, and “barriers to recovery through religion/spirituality”. The first 2 themes highlight some of the positive aspects that aid participants’ recovery. The third theme reported hindrances in participants’ religious or spiritual practices and beliefs. Each theme is discussed with reference to sub-themes and illustrative excerpts. Practical implications: Religion or spirituality might support therapeutic engagement for some service users and staff could be more active in their inquiry of the value that patients place on the personal meaning of this for their life. Originality or value: For the participants in this study, religion or spirituality supported the principles of recovery, in having an identity separate from illness or offender, promoting hope, agency and personal meaning.’ |

| Reason | Data on patient’s lived experiences of religion and spirituality appears to be discussed in the context of personal recovery only. |

| Title | An exploration of the support provided by prison staff, education, health and social care professionals, and prisoners for prisoners with dementia |

| Abstract | […] The aim of this study was to gain an understanding of the lived experience of prison staff, education, health and social care professionals and prisoners with a social care role who supported men with dementia in prison. […] |

| Reason | No lived experiences of prisoners with dementia themselves. |

We also made decisions on robustness criteria relating to the research ontology and epistemology of the studies. The next section explains these criteria and gives examples of how they were applied.

Robustness test: maintaining a social perspective on disability

The social model approach, which frames public policy in this field, distinguishes between:

- disability as a social condition

- impairment as an individual characteristic

For example:

Impairment is a characteristic of the mind, body or senses within an individual which is long term and may, or may not, be the result of disease, genetics or injury.