Tampon Tax Fund evaluation: main report

Published 6 June 2023

Key findings and recommendations

The Tampon Tax Fund (TTF) was established to distribute the VAT on sanitary products to fund a series of projects to tackle the issues facing women and girls across the UK. Through six competitive funding rounds, between 2016 and 2022, a total of 137 grants were awarded from a Fund value of £86.25 million to 125 voluntary and community sector (VCS) organisations. These awards included at least 20 onward grant funders, who distributed over £30 million of the Fund value to an additional 1,230 organisations

Who received funding and how was it used?

Funding successfully reached a diverse range of VCS organisations; the onward grant mechanism and the inclusion of a general theme for each round of funding enabled organisations of all sizes and interests within the VCS to participate.

TTF funded a range of activities covering diverse issues, including specialist trauma-informed services and violence against women and girls (VAWG) services. Funding was commonly used in projects to address lack of access to services for women and girls. The most commonly funded activities across projects were frontline services (58%) and capacity building (38%).

What were the reported outcomes and impacts of the Fund?

Demand for the Fund was high, and it was perceived as an important funder of VCS organisations at a time of limited funding opportunities. TTF grants also represented a sizeable proportion of the income of some grantees in the year(s) they received funding.

Project data suggests a range of improved outcomes for beneficiaries such as improved access to quality support for women and girls receiving TTF funded services.

In addition to positive outcomes for women and girls, evidence also suggests that TTF provided new resources to the VCS sector, enabling new partnerships and workstreams and contributing to both organisational and sector strengthening.

What worked well and what worked less well across Fund delivery?

Enablers of successful Fund delivery included the Fund’s broad remit, allowing for a diverse portfolio. The onward grant model enabled small and medium-sized organisations to access funding, some of which lacked the capacity to apply directly.

Challenges included defining outcomes and impacts due to the Fund’s broad remit.

What worked well and what worked less well across project delivery?

Enablers to successful project delivery included effective partnership working, scoping research in early stages of delivery and consultations with beneficiaries.

Challenges included short timeframes for delivery (particularly for onward grant-makers), and the recruitment of suitable personnel to manage and deliver projects.

What are the recommendations for future funds?

For future funds, recommendations include: develop a logic model at the fund design stage to clarify and focus overarching design and core objectives; continue to engage with the onward grant approach to maximise participation in future funds; and consider how networking between projects can be facilitated to strengthen outcomes further.

For the evaluation of future funds, recommendations include: consider detailed monitoring of onward grantee organisations and their activities to enable a robust understanding of grant recipients and to support evaluation activity.

Executive summary

Introduction

The Tampon Tax Fund (TTF) was announced in 2015 to invest money from VAT on sanitary products in projects, delivered by voluntary and community sector (VCS) organisations, to tackle the issues facing disadvantaged women and girls across the UK. The Fund was managed by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) on behalf of HM Treasury. DCMS was responsible for application appraisal, grant-making and grant management.

Six rounds of applications for TTF funding took place between 2016/2017 and 2021/2022, each featuring a combination of direct grant funding and distribution via onward grant funders to enable organisations without the capacity to apply directly to be supported. Each round included a focus on violence against women and girls (VAWG), with a ‘general’ theme applying to all six rounds and additional annual themes such as mental health and wellbeing, rough sleeping and homelessness, and music. In the 2020/2021 and 2021/2022 rounds, grantees could allocate up to 10% of their funding to supporting organisational sustainability.

Between 2016 and 2021 a total of 137 grants were awarded to 125 direct grantees from a total Fund value of £86.25 million (with grants ranging between £16,500 and £3.5 million). At least 20 grantees also included an onward funding element; distributing 1,622 onward grants with a value of over £30 million to 1,230 organisations (with grants ranging between £800 and £212,000).

Evaluation approach

In 2022, DCMS commissioned Kantar Public to deliver a process and impact evaluation of TTF. The process evaluation comprised of a review of TTF applications, case study research with recent and past grantees, and in-depth interviews with TTF stakeholders and unsuccessful applicants. The impact evaluation comprised of an analysis of available grantee monitoring data and End of Grant reports, analysis of public data at a sector level, a survey of grantees and a qualitative impact assessment to identify drivers of change and the Fund’s contribution to observed impacts.

The findings of the evaluation, and its conclusions and recommendations, are summarised below.

Process evaluation key findings

The process evaluation included three research questions:

Who received TTF funding, how was it used and who did it reach?

Direct grantees varied widely in size, specialism, level of income and geographic coverage. Half of the projects funded focused solely on England, while the other half covered projects focused on Northern Ireland, Scotland, Wales and UK-wide initiatives. The income profile of the direct grantees was broad. According to the latest income reported to the Charity Commission, 29% of direct grantees had an income under £1 million and 18% had an income over £10 million.

TTF funding supported a wide range of activities, which fell into seven broad categories: onward funding, frontline services for women and girls, education, training, capacity building, resources, equipment and technology, and signposting and awareness raising. Projects delivering frontline services to women and girls were the most commonly funded, often alongside capacity building interventions. The types of frontline services supported commonly included targeted VAWG services, such as rape crisis and trauma-informed support for specific groups.

The majority of grantees and stakeholders consulted felt that TTF had successfully reached its intended broad target group of disadvantaged women and girls, a finding supported by the analysis of project monitoring data and End of Grant reports. This analysis showed that the projects also commonly targeted specific subgroups of women and girls depending on their organisational focus, areas of specialism, and existing networks.

Analysis of the 77 grantee and onward grantee survey responses suggested the most common beneficiary groups were marginalised groups (52% of grantee respondents); survivors of domestic abuse (49%); and survivors of sexual harassment or assault (38%).

How was TTF delivered and experienced by stakeholders, grantees and beneficiaries?

Applicants, both successful and unsuccessful, generally concurred that the Fund was managed effectively, and welcomed the opportunity to bid for funding which could be applied to a broad range of issues.

The number of applicants each year suggested a high level of awareness and demand for the Fund. Some of those applying to multiple rounds reported the application process had become more demanding over time, and some felt the feedback on unsuccessful bids could be improved.

Overall, what worked well and what worked less well?

Several key enablers supported the successful delivery of TTF at the Fund level, including the Fund’s broad remit, which facilitated responsive grant-making and resulted in a diverse portfolio of projects and project activities. Other perceived enablers included:

-

a bid selection process that was generally considered to be fit for purpose, where a focus on organisation size and capability ensured organisations had the capacity to deliver

-

the onward funding model, enabling a wider set of smaller organisations to be reached

-

the effective administration of the Fund by DCMS on behalf of HM Treasury, including positive working relationships between the two departments

In relation to project delivery, effective partnership working was key to success, with other enablers including scoping research in early delivery which allowed for effective project development, and consultation with beneficiaries.

Challenges included delivery timeframes for projects (particularly for onward grant-makers), and the recruitment of suitable personnel to manage and deliver projects.

Impact evaluation key findings

The impact evaluation sought to identify the impact of TTF on grantees and beneficiaries, and whether there were any unintended consequences of the Fund.

What reported/perceived impact did TTF have on grantees and beneficiaries?

Grantees reported achieving a range of short-term and long-term positive outcomes for beneficiary women and girls. The most commonly reported outcomes for beneficiaries were in relation to increased access to services during the TTF funding period; improved confidence amongst those receiving services; enabling women and girls to act as their own agents; and reduced risk of violence and harm for women and girls.

The TTF provided a significant level of funding to grantees to help address the challenges facing women and girls, at a time when available funding for VCS organisations was limited. The modelling of grantee financial accounts shows that their incomes were on average 12% higher in the year(s) they received TTF funding than would be predicted in its absence, which suggests TTF provided important additional resources for VCS organisations rather than displacing other funding.

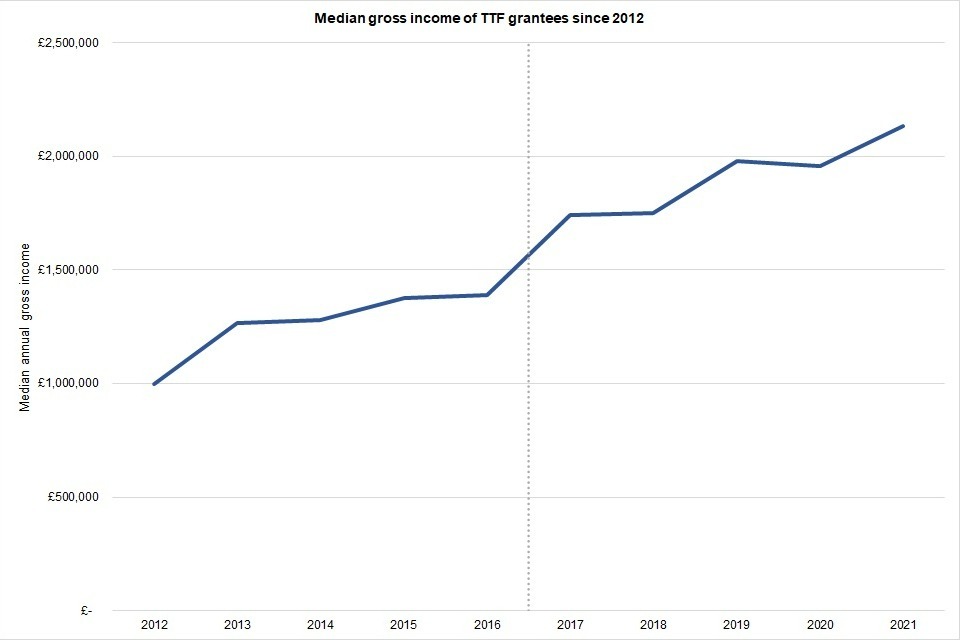

Further, the median incomes of previous grantees continued to increase after their TTF funding periods. While care must be taken attributing this increase to TTF due to the range of other factors involved, one explanation is that TTF contributed to strengthening the sector through its impacts on new partnerships, workstreams and organisational capability developed during project implementation.

TTF successfully reached a diverse portfolio of organisations. The onward grant mechanism enabled TTF to reach a wider range of organisations, including (but not exclusively) smaller organisations. TTF funding also enabled organisations to establish new areas of work and strengthen existing work – activities that were unlikely to have been possible without TTF funding. This includes developing new resources to support VCS activity and knowledge.

TTF also enabled new partnerships to be established, and in some cases – notably in relation to financial connections – these were maintained following TTF funding. The income eligibility criteria encouraged organisations to form partnerships and consortia to access the Fund, and many grantees indicated their commitment to continue their new partnerships.

No significant negative unintended consequences were identified, with positive examples cited including helping grantees adapt to COVID-19 delivery and raising the profile of organisations in the sector.

Conclusions and recommendations

TTF successfully reached a wide range of organisations supporting its intended target group of women and girls through a combination of direct and onward grant funding, distributing £86.25 million between 2016/2017 and 2022/2023. TTF supported a diverse range of projects, most frequently projects improving women and girls’ access to frontline services.

The evaluation identified factors that were key to successful Fund management, including “fit-for-purpose” bid selection criteria, effective partnership working and consultation with beneficiaries. Challenges identified included delivery times for projects as government funds are required to operate and deliver funds on an annual basis.

Evidence suggests TTF enabled positive outcomes for service users and at the organisation and sector levels, providing additional resources, supporting network building, and establishing new workstreams. While caution should be exercised when interpreting this finding, financial analysis has shown that direct grantees increased their income after the funding period, suggesting the sectoral strengthening aims of the Fund were being achieved.

Our recommendations for future fund design and project delivery include the following:

-

Develop a logic model at the fund design stage to maximise the effectiveness of the fund and enable clearer evaluation outcomes.

-

Consider utilising additional resource to build in networking opportunities for grantees, to further strengthen fund outcomes.

-

Continue including sustainability considerations as an element of fund design, such as a dedicated and ring-fenced resource to support grantees’ organisational sustainability.

-

Encourage greater collaboration with devolved administrations in overall fund delivery and to help strengthen outcomes further.

Tampon Tax Fund Evaluation Findings

1. Introduction

The Tampon Tax Fund (TTF or ‘the Fund’) was announced in 2015 to allocate funds generated from the VAT on sanitary products to projects to address the challenges facing disadvantaged women and girls across the UK. The Fund was managed by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) on behalf of HM Treasury.

TTF has provided six annual funding rounds for not-for-profit organisations in the UK between 2016/2017 and 2021/2022. Each round targeted projects focused on violence against women and girls (VAWG). Each round included a ‘general’ theme, which enabled organisations working with women and girls to apply if they were able to demonstrate need, with specific annual themes including mental health and wellbeing, young women’s mental health, rough sleeping and homelessness, and music. Through the provision of direct funding, and via onward grants, up to £86.25 million of TTF funding has been distributed through 137 TTF grants.

This report is accompanied by eight appendices providing further detail on the methodological approaches to, and findings from, the main evaluation workstreams:

-

Appendix 1: TTF Logic Model, showing the rationale and mechanisms underpinning TTF.

-

Appendix 2: Findings from the bid review evidence synthesis.

-

Appendix 3: Findings from the case study research.

-

Appendix 4: Findings from the stakeholder interviews.

-

Appendix 5: Findings from the public data analysis.

-

Appendix 6: Findings from the grantee survey.

-

Appendix 7: TTF grantee survey questionnaire.

-

Appendix 8: Findings from the Qualitative Impact Protocol (QuIP).

2. Methodology

In 2022 DCMS commissioned Kantar Public to evaluate TTF. Following a scoping exercise, Kantar Public designed a mixed-methods approach to address the following research questions proposed by DCMS:

Which organisations received TTF funding, how was it used and who did it reach? Who did it not reach, and why?

How was TTF delivered and experienced by stakeholders, grantees and beneficiaries?

Overall, what worked well and what worked less well?

What impact (reported or perceived) did TTF funding have on grantees and beneficiaries?

What, if any, were the unintended consequences of the programme?

2.1 Scoping phase methodology

A scoping phase was conducted to assess the feasibility of undertaking a process and impact evaluation of TTF and to develop an evaluation design. The scoping phase included the review of 33 grantee applications and 24 in-depth interviews with a sample of Fund stakeholders (four participants from central government, 18 from grantee organisations and two from wider voluntary and community sector (VCS) organisations). The findings informed the development of a TTF logic model and evaluation approaches. The theory-based design developed, and findings from the scoping phase, are provided in the TTF evaluation report.

2.2 Process evaluation methodology

For the process evaluation workstream, Kantar Public completed a review of the available bid documentation for direct grantees to provide an overview of activities to be delivered under the Fund. Documentation was available for all bids, with the exception of monitoring and end of grant documentation for 36 projects managed by devolved administrations or the Department for Health and Social Care (22 projects), or where projects were being delivered at the time of research (14 projects). In addition, eight case studies were conducted with five recent and three previous grantees, alongside in-depth interviews with five government stakeholders and three organisations submitting unsuccessful applications to capture their experiences of the application process, project and Fund delivery and lessons learned. The process evaluation methodology is documented in Appendix 2, Appendix 3 and Appendix 4.

2.3 Impact evaluation methodology

For the impact evaluation workstream, Kantar Public synthesised the available grantee monitoring and reporting documentation, providing an overview of grantees’ self-reported outcome and impact data where available. Publicly available Charity Commission data was analysed to explore TTF grantees and wider VCS trends in relation to organisational income, expenditure and financial networks.

A survey of grantees and organisations receiving funding via onward grants (‘onward grantees’) was also conducted, achieving 43 and 34 responses respectively, which also included questions relating to their experiences of project delivery to inform the process evaluation. The survey was sent to 62 direct funded organisations and a further 22 direct funded organisations known to have given onward grants. Those distributing onward grants were asked to forward the questionnaire to their onward grantees, although it is not known how many onward grantees received it. A Qualitative Impact Protocol (QuIP) was conducted with 13 grantees and 27 onward grantees to identify sources of impact in relation to TTF. The impact evaluation methodology is documented in Appendix 2, Appendix 5, Appendix 6 and Appendix 7.

2.4 Key considerations and limitations

The evaluation methodology was informed by the following considerations and limitations:

The evaluation was conducted retrospectively and therefore lacked baseline data and, in some cases, relied on interviewee recall. The timeframe for fieldwork was restricted to a two-month period which affected the number of grantees and stakeholders it was possible to reach across research activities. A small number of qualitative interviews were conducted, limiting generalisability of findings.

The broad remit of TTF: grantees are extremely varied in their focus, and so the potential outcomes and impacts achieved also varied.

Variation across funding rounds regarding eligibility criteria, annual themes and monitoring processes, and variable approaches to local output and outcome data collection.

The 2021/2022 grantee cohort were still delivering projects during the evaluation period, so it was too early for their outcomes to be achieved.

3. Overview of the Fund and funded projects

This section addresses the research questions: “Which organisations received TTF funding, how was it used and who did it reach? Who did it not reach, and why?”

3.1 Overview of TTF

From 2015/2016, the taxation income from sanitary products has been awarded on a competitive basis to not-for-profit organisations supporting women and girls across the UK. VCS organisations could submit bids for TTF funding individually or as consortia, with the first two rounds having no minimum criteria for funding thresholds. In 2018/2019 a minimum grant size of £1 million was introduced, with the aim of achieving a more cohesive and strategic approach to addressing the issues facing women and girls. As bid values could not exceed 50% of applicants’ or consortias’ combined annual incomes, this threshold was reduced to £350,000 in 2021/2022 to enable smaller organisations to apply.

Four delivery models were established in the TTF logic model:

Model 1: organisations/partnerships of organisations use TTF funding to provide frontline services and support directly to women and girls – 41% of awards.

Model 2: organisations use TTF funding to provide capacity building activities (e.g. training for professionals) to improve the quality of interventions for women and girls – 45%.

Model 3: organisations receive TTF funding and act as intermediary grant-makers to fund others to deliver activities to support women and girls – 9%.

Model 4: organisations receive TTF funding and act as intermediary grant-makers to fund capacity building activities to improve service quality for women and girls – 14%.

Direct TTF grants awarded ranged from £16,500 to £3.5 million in value. Between 2016 and 2021 awards were made to 125 direct grantees through 137 TTF grants, with a combined Fund value of £86.25 million. Within this, at least 20 grantee organisations used TTF funding to provide onward grants to an estimated 1,230 organisations, 29 of which also received direct funding, accounting for one-third of all TTF funding awarded (estimated to be just above £30 million). Further details of the funding awarded are shown in Table 1.

To ensure a focus on learning and sustainability, applicants were asked to include plans to evaluate and sustain their activities in their applications. In the 2020/2021 and 2021/2022 funding rounds, grantees were also given the opportunity to allocate up to 10% of their grant funding towards organisational sustainability. Applicants for projects that involved onward grant-making were also encouraged to include a sustainability element in the criteria for these onward grants. This funding could be used for a range of purposes, including upskilling existing staff, improving internal systems and processes, and building transformative digital investments. For example, a £1.2 million project to update a pre-existing app to support women through their maternity journey and improve maternity outcomes received sustainability funding of £75,088. This was used to increase the capacity to train and grow their engagement team, and to ensure that they had the capacity to train, support and embed new project staff and processes into the organisation.

Finally, in addition to a ‘general’ theme, annual themes were also established for each funding round, as shown in Table 1 below.

3.2 TTF funding awarded

A total of 137 funding awards were made for direct TTF funding, reaching 125 direct grantee organisations (and over 1,230 organisations through onward grant funding) across the duration of the Fund. Table 1 provides an overview of the number and value of grants and onward grants awarded throughout the programme, and the themes each year.

Table 1: Overview of annual TTF funding rounds

| Round | No. grants awarded | Value grants awarded | No. onward grants | Value onward grants awarded | Specific themes per round |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016/2017 | 20 | £15,047,999 | 67 | £2.63m | General, Violence against women and girls |

| 2017/2018 | 70 | £11,742,707 | 143 | £2.32m | General, Violence against women and girls |

| 2018/2019 | 11 | £15,197,675 | 595 | £9.66m | Mental health and wellbeing, Violence against women and girls, General |

| 2019/2020 | 10 | £14,853,014 | 319 | £4.90m | Homelessness/rough sleeping, Music, Violence against women and girls, General |

| 2020/2021 | 12 | £14,849,999 | 136 | £3.02m | Young women’s mental health, Violence against women and girls, General |

| 2021/2022 | 14 | £11,100,000 | 163 | £4.49m | Ending violence against women and girls, General |

| Total | 137 | £82.8m | 1,622 | £30.06m | |

| Total incl. project admin costs | 137 | £86.25m | 1,622 | £30.06m |

Across the Fund as a whole, 23% of the total funding awarded was received by five organisations providing onward grants to other organisations. According to records provided by DCMS, since 2017, at least 20 TTF direct grantees distributed 1,622 onward grants to 1,230 organisations, with a total value of just over £30 million. This is a third of the total amount awarded by TTF over the six years it was active (£86.25 million).

Grants to direct grantees were most commonly awarded at a value of £1 million to £2 million (36 bids), which accounted for over 50% of the total TTF funding allocated (approximately £43 million). Although the number of grants awarded to projects with budgets between £100,000 and £250,000 was almost the same (35), the total funding these projects received was just £5,750,025. The onward grant-making model also enabled funding to be redistributed as smaller grants to a wider set of organisations. Onward grants were typically small, with the median value being around £10,000 and around 80% of onward grants being between £5,000 and £40,000. In most years, a single organisation distributed the majority of onward grants. In fact, just under half of all grants were distributed by a single organisation.

Overall, almost 75% of TTF funding provided to direct grantees was allocated to the 31% of projects with budgets of over £1 million. The 18% of projects with budgets under £100,000 (25 bids) received around 2% of the total TTF funding (around £1.73 million).

The geographic areas covered by the bids and projects funded included all areas of the UK. Approximately 20% of projects reported covering the whole of the UK, while half focused solely on England, 6% solely on Wales, 3.5% solely on Northern Ireland and 10.5% solely on Scotland, in line with the Barnett formula.[footnote 1] Fund allocations in Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland were also part of UK-wide projects.

3.3 How TTF funding was used

TTF funding was generally used to provide activities supporting women and girls, or to support professionals within the VCS, with the aim of improving the lives of disadvantaged women and girls. Specific activities delivered fell into seven categories, as shown in the TTF logic model:

Onward grant-making: Funding received is redistributed as smaller grants to wider organisations, aligned with the themes of TTF and with a focus on reaching small and medium-sized community organisations without direct TTF access. Onward grant-making leads onto a wider set of interventions falling into one of the six other categories below.

Frontline services: Support and services are provided to women and girls. Examples of frontline services include the provision of one-to-one or group support, peer/community support, coaching/mentoring, housing and accommodation, etc.

Capacity building: Support is provided to an organisation to improve practices and support for women and girls, such as shared learning and networks, support for implementing best practice, reviewing/rolling out organisational policy and digital skills provision.

Training: This is provided to professionals and organisations, or women and girls with lived experience, to better equip them to support women and girls in need. Training for those with lived experience also includes providing frontline support and education opportunities.

Signposting and awareness raising: Signposting is provided to women and girls to raise awareness and improve access to support services. This intervention seeks to strengthen support pathways and increase access to support, as well as to enable joined-up working.

Education: Provision of education and/or training is delivered to support women and girls’ knowledge and skills development, for example language skills.

Resources, equipment and technology: The provision of physical or digital equipment, tools or resources delivered to support women and girls, such as providing bikes, sanitary products, online services, educational resources or digital content.

The most common types of activity supported were the delivery of frontline services and capacity building interventions, and the least common were signposting, awareness raising interventions and training for professionals. Frontline services included:

-

targeted VAWG support services, for example rape crisis and trauma-informed holistic support for specific groups of survivors of sexual violence

-

other support services, such as mental health or financial advice such as evidence-based guidance for carers to help them support a family member with an eating disorder

-

outreach programmes on a range of issues affecting women and girls, often targeting specific groups, including those from ethnic minority backgrounds and (ex-) offenders

The most and least common issues addressed by grantees are shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Issues addressed by TTF projects

| Most common issues | Least common issues |

|---|---|

| Lack of access to services for women and girls – providing funding for service delivery | Lack of support for women during pregnancy, miscarriage and maternity care |

| Lack of specialist trauma-informed approaches in services – TTF developed approaches such as supporting black and minority groups, women and girls with disabilities, and refugee women and girls | Low levels of help-seeking among women and girls affected by problem gambling, and a lack of research into links between problem gambling and domestic abuse |

| Lack of funding to support women and girls affected by abuse, violence and harassment | Lack of equipment/resources for audiences to address specific issue, such as free sanitary products to address period poverty |

TTF reached both well-established and more recently established organisations. A quarter of direct grantees in England and the devolved administrations were registered before the 1980s, and a quarter were registered in the 2010s. This is broadly comparable to the profile of other charities of a similar size and scope (around a third registered between the 1960s and 1980s, and a quarter in the 2010s).

As part of their Charity Commission reporting duties, charities in England and Wales selected predefined categories to describe their activities and who they supported. Although these categories were broad, they allowed organisations to be profiled by focus and target beneficiaries. Education and training was the most prevalent category for both direct grantees (72%) and other charities of similar size and scope (64%). Direct grantees were more likely to select “the advancement of health” and “general charitable purposes” than other similarly sized charities in the wider VCS, but were less focused on “arts and culture”, “environment and conservation”, “religious activities” and “recreation”.

While the Fund required bids to target women and girls overall, projects often targeted specific subgroups depending on their project activities, sector specialism or existing networks. The direct grantee survey results give an indication of the types of beneficiaries targeted. As Table 3 shows, direct and onward grantees were most likely to report delivering activities to marginalised groups (52%), survivors of domestic abuse (49%), women and girls in need (45%) and survivors of sexual harassment or assault (38%).

Table 3: Audiences delivered to using grant funding

| Audiences | All | Direct grantees | Onward grantees |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marginalised groups, e.g. minority communities, refugees | 52% | 47% | 59% |

| Survivors of domestic abuse | 49% | 51% | 47% |

| Those providing support or services to women or girls in need (frontline workers) | 45% | 51% | 38% |

| Survivors of sexual harassment or assault | 38% | 40% | 35% |

| Those without access to sanitary products | 9% | 7% | 12% |

| Other | 17% | 19% | 15% |

| Base: All respondents (n = ) | 77 | 43 | 34 |

Source survey question: Across all the activities you delivered as part of this Tampon Tax Fund project, who is/was the intended audience(s) or beneficiary group? (Base all: n = 77)

On the basis of consultations with grantees and stakeholders, it appeared that TTF had been successful in reaching its intended audience of women and girls, particularly those experiencing disadvantage. Almost all respondents to the grantee survey reported being confident that their project had reached/is reaching its intended beneficiaries (99%). However, due to variations and inconsistencies in project-level reporting, the evaluation was unable to estimate the number of women and girls reached overall.

4. Overview of process evaluation

This section addresses the research questions: how was TTF delivered and experienced (by stakeholders, grantees and beneficiaries)? Overall, what worked well and what less well?

4.1 How TTF was delivered at a Fund level

TTF was managed by a core Fund management team within DCMS, operating on behalf of HM Treasury. This team was responsible for day-to-day Fund management, including running the funding competition, assessing applications, carrying out due diligence checks, shortlisting, relationship management and monitoring and evaluation support. With each funding round, eligible organisations were invited to submit an application within a six week period.

Once submitted, DCMS took the following steps to appraise applications:

-

The selection criteria and scoring matrix were set out by DCMS.

-

Assessors from relevant government departments and the devolved administrations were selected and trained.

-

The core TTF team established which applications met the selection criteria, after which the assessors reviewed and scored all eligible applications.

-

An expert panel discussed the assessment results for eligible applications, considered the overall balance in the portfolio (with allocations across England and the devolved administrations according to the Barnett formula), and made recommendations for ministerial approval at DCMS and HMT. Ministers approved the final selection before grantees were awarded.

-

Fund staff worked to ensure all due diligence processes were conducted before awards were made.

Table 4 shows the number of applications received by DCMS each year and the number of grants awarded. Although data is not available on the number of applications received in the 2016/2017 and 2017/2018 funding rounds, the number of applications remained broadly consistent between the 2018/2019 and 2021/2022 funding rounds, suggesting consistently high levels of both awareness of, and demand for, TTF funding.

Table 4: Number of applications received and grants awarded

| Funding year | Applications received | Grants awarded |

|---|---|---|

| 2021/2022 | 186 | 14 |

| 2020/2021 | 140 | 12 |

| 2019/2020 | 143 | 10 |

| 2018/2019 | 195 | 11 |

| 2017/2018 | Information not available | 70 |

| 2016/2017 | Information not available | 20 |

4.2 What worked well and what worked less well at a Fund level

4.2.1 Learning for Fund design and set-up

The broad remit of the Fund facilitated responsive grant-making and a diverse portfolio. Guidance for the 2021/2022 funding round stated that “The purpose of the Tampon Tax Fund is to allocate the funds generated from the VAT on sanitary products to projects that improve the lives of disadvantaged women and girls”. This broad remit remained the same across all funding rounds, although annual themes (for example VAWG and mental health and wellbeing) provided further specification, along with a ‘general’ theme. This breadth of remit brought several benefits, according to interviews with stakeholders across government, including providing flexibility in terms of grantee selection which resulted in a diverse set of grantees and projects each year:

It had a lot of flexibility and positive elements that some restricted grant funds don’t have. [It] touched on a broad array of girls’ and women’s issues.

– Government stakeholder interview participant

The robust nature of the application process reassured stakeholders that applicants had the capacity to deliver their projects effectively. The approach also allowed DCMS to respond to the needs of grassroots organisations, with annual themes targeting funding towards organisations with a very specific focus, such as those working with music for female carers:

[We] could be very responsive to the problems coming through from … organisations in the know, rather than being top-down …

– Government stakeholder interview participant

There were quite niche projects that would have really struggled to find funding elsewhere.

– Government stakeholder interview participant

However, some interviewees also described drawbacks to this breadth. Some noted that it made it difficult to specify the expected outcomes of the Fund, which in turn made it harder to demonstrate impact and so make the case for continued future government funding.

Those involved in the process felt that the bid selection approach and criteria were fit for purpose and ensured that grantees with capacity to deliver were selected. TTF was successfully delivered; the process and criteria enabled those administering the Fund to select capable grantees that would be able to deliver on their plans.

DCMS created a balanced portfolio of grantees, although government stakeholder interviewees involved in Fund management found this was sometimes challenging with the limited amount of funding for grant-making (which was based on receipt of tax from period products). While the application processes enabled DCMS to establish a balanced and diverse portfolio of grantees across years, interviewees involved in Fund management noted several challenges to achieving this. First, they found it challenging to satisfy all the selection criteria. Second, adherence to the Barnett formula (6% of the Fund allocated to Wales, 3.5% of the Fund allocated to Northern Ireland, and 10.5% allocated to Scotland), combined with a high minimum grant value, often meant each devolved administration could receive only one grant each year that focused solely in the devolved administration. However, funding could still be accessed through UK-wide projects.

In addition to the direct grantee route, the inclusion of the onward grant-making mechanism enabled the Fund to reach a wider set of organisations, notably smaller, grassroots organisations that might be less likely to be able to submit applications on their own or as part of consortia. It is interesting to note that, when the minimum funding threshold was raised to £1 million in 2018/2019, this round saw the largest number of onward grants awarded (555) and the greatest value disbursed (£9.66 million). This was reflected, to a lesser extent, in the 2019/2020 round when the £1 million threshold was also in place. While not all onward grant awards necessarily reached smaller organisations, these findings suggest smaller organisations were able to benefit from onward grant awards across all TTF funding rounds.

4.2.2 Learning from Fund management experiences

Members of the TTF management team taking part in interviews felt they were able to develop and maintain good relationships with grantees. This was felt to be slightly limited by the allocated running costs, which were set at 1% of the annual Fund value in order to offer best value and to ensure the maximum amount of funding was directed towards project activities. A TTF network was set up in April 2022, consisting of quarterly meetings with grantees and DCMS staff. Some interviewees felt that additional management budget could have enabled DCMS to facilitate greater network building and share learning between grantee organisations earlier in the lifetime of the Fund, helping maximise impact.

In addition, a range of other contextual factors influenced Fund development and delivery. Funding rounds featured different themes or funding streams that organisations could apply for. These themes were informed by ministerial and government policy priorities in different years and influenced the types of organisation applying to the Fund. Consistent themes across the Fund were the general theme and VAWG.

Government stakeholder interviewees from a devolved administration found interactions with DCMS to be open and helpful, but would have welcomed increased involvement in final grantee selection. Devolved administrations were involved in assessing applications and providing recommendations to DCMS that informed funding decisions.

4.2.3 Learning from bid application experiences

Overall, the learning from applicants in previous rounds was felt to have facilitated a smoother application process in later rounds. Where projects had applied for previous TTF rounds, they felt it helped them complete subsequent applications successfully. Some case studies felt they had become more efficient at applying as they were more familiar with the process, including having more time to evidence the need for their intervention and adapt to the aims to the Fund:

We’ve flexed to support [students’] needs in the best way possible, and the funder has supported us to do that. And I think that’s the mark of a really good funder … we’re all staying on the same hymn sheet.

– Case study interview participant

We’ve got pretty good at being able to match something that we want to get funded, with what the criteria is for funding provision.

– Case study interview participant

In addition, guidance and support from DCMS was helpful in mitigating what was often described as a demanding application process (particularly where applicants were able to compare early and later rounds). The case study interviewees and unsuccessful applicants generally felt the information and guidance was clear and helpful, with some variation by year.

From 2018/2019 on, the application guidance from DCMS was generally found to be clear, and those seeking additional information from DCMS found them to be helpful (72% of respondents to the grantee survey reported having sufficient guidance to support the process). However, fewer respondents agreed that the bidding process requirements were realistic and appropriate for their organisation (58%) or that the time and resource needed for the bid were suitable (51%), as the application forms were often seen as repetitive and time-consuming.

The application process developed over time, with a more thorough approach being taken in later years. As described above, the initial TTF application rounds were experienced as ‘light of touch’, although serial applicants reported that the requirements had become more detailed (described by some as ‘more onerous’) in recent years. Requirements for the first rounds were straightforward as there was no application form or specific requirement above providing a proposal and a budget:

You didn’t have to do any kind of grant application form; all I was asked to do was to write in [with] a proposal and our financial information and budgets…

– Unsuccessful applicant interview participant, 2016

However, from the third round (2018/2019) onwards, applicants found the process increasingly complex, with a lengthy application form requiring a large volume of information and many supporting documents. Considerable time and effort was required to apply, and applying to TTF in later years was considered to be more time-consuming than for other funds:

The process that’s set up is worth it if you get the funding, but I think if you put all that work into it and weren’t successful, you might have a different opinion.

– Case study interview participant

The main thing to feed back … is the enormous amount of work that goes into these [TTF] applications … they are enormously time-consuming.

– Unsuccessful applicant interview participant, 2018

Organisations submitting unsuccessful bids felt that information on the assessment process was opaque, and that feedback on their bids was limited and prevented learning. Unsuccessful applicants also described difficulties identifying if they had been awarded funding and reported receiving scant feedback on their applications. This did not help them understand why they were unsuccessful and so learn:

… it was very limited … we got three sentences … it says this was an excellent application, it was clear and succinct, … but … it did not score as well as other applications. It would be really helpful to get [an] assessment of strengths and weaknesses.

– Unsuccessful applicant interview participant, 2018

Both grantees and unsuccessful applicants also stated that, in contrast to other funders they had engaged with previously, they did not receive a TTF scoring matrix, making it hard to know the relative weighting across the stated criteria.

4.3 TTF delivery at the project level: what worked well and what worked less well

Experiences of project delivery were captured through the grantee survey, case studies and in-depth interviews. The key learning points and insights are set out below.

4.3.1 Learning from project delivery

Overall, grantees were positive about their experience of delivering their projects and were able to achieve their goals despite some challenges. Effective partnership working, engaging in scoping activities prior to delivery, and ongoing consultations with stakeholders and beneficiaries were noted as facilitators of delivery. This confidence was reflected in the TTF grantee survey, where almost all respondents considered that their projects were reaching their intended beneficiaries (99%) and were being delivered to plan (96%).

Effective partnership working was central to, and facilitated the successful delivery of, TTF projects. Interviewees across all funding rounds described the importance of partnering with other organisations for the successful implementation of interventions. Grantees often spoke highly of their delivery partners and the positive relationships formed with them. These collaborations, along with their own expertise, were felt to be instrumental in overcoming barriers and delivering projects successfully.

Early scoping research was important for informing the development of interventions. For example, some grantees included a scoping phase to conduct research with target groups to help shape intervention development. For example, one case study held workshops with practitioners and survivors of abuse to test the usability of a new digital tool that helped identify priority areas for improving the function of the tool in mainstage delivery.

Consulting beneficiaries and advisors at various stages during delivery allowed grantees to adapt their interventions more effectively. Most of the case studies described carrying out consultations, feedback sessions and evaluations at various points to provide formative learning to improve or adapt delivery. For example, as the result of beneficiary feedback, one case study introduced an SMS option for students to provide feedback on a training programme, which led to an increase in responses. Another case study, which consulted women who were using their service on the design of their interventions (training programmes and a refuge centre) during the design phase, felt this consultation contributed to buy-in from beneficiaries at later stages of delivery.

Contextual factors played a significant role in the delivery experience. Projects highlighted how they had adapted project delivery in response to contextual factors (most notably for recent projects that delivered during the COVID-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis) that had also impacted on the funding landscape for the VCS. Many mentioned adapting activities or services during the pandemic, such as moving to online or hybrid delivery:

So, we have some online courses and that was new obviously because of COVID. … We don’t allow children [in the centre], so actually, during COVID, we could access people who didn’t have childcare, people in rural parts of the borough who don’t even have buses or can’t afford buses. So, we have a blended approach to that now, we do still deliver classes online. That was a sort of an unexpected wake-up call for us, actually.

– QuIP interview participant

Grantees also reported other challenges acted as barriers to delivery. These included:

-

Short timeframes for project delivery: For example, the case studies felt the turnaround times were tight for delivering interventions, particularly for onward funders who often needed to complete numerous administrative tasks to set up their approaches to bid selection and management.

-

Recruiting suitable individuals for project roles: Some case studies mentioned that filling specific job roles was an issue, due to the short-term nature of the roles and to contextual factors such as a skills shortage in what grantees felt is often a low-paid and stressful sector. Recruitment issues often caused timelines to slip, with a knock-on effect for the length of job posts.

-

The nature of the projects meant grantees faced challenges in measuring outcomes and impacts. While in consultations grantees were able to identify some outcomes and impacts, these were often based on anecdotal evidence.

4.3.2 Project sustainability

The evaluation explored the extent to which grantee’s TTF project activity continued following the end of the funding period, and (for ongoing projects) whether they had made progress towards sustaining their activities.

Of the grantees, 50% with ongoing projects provided details of future intentions and plans post-TTF funding in the bid review. In the majority of cases, these were positive, with intentions to continue to improve and/or expand services using experience and capacity developed during the TTF project. In most cases, this included using a continuation (or increase) in income from other sources already developed during the TTF project period, as well as increased organisational networks and/or learnings from the TTF project, to broaden services provided or areas covered. In other cases, funding was still being sought but plans were positive: for example, large funding applications had been submitted or strategic fundraising working groups established.

However, there was a mixed picture regarding the extent to which TTF funded activities had actually been sustained following the end of funding, which depended on a grantee’s ability to secure future funding. The most recent grantees of the Fund were in the process of seeking future funding in order to continue or develop interventions and reported significant uncertainty regarding the future of their projects. Some past grantees secured future funding for the continuation of elements of their project from a range of sources, including internal streams of income, or additional funding from external partners or government funds (for example, Home Office funding).

Respondents to the TTF grantee survey provided more detail on the types of intervention sustained after the end of funding. Almost all of those delivering awareness raising and campaigns (n = 19) and signposting of resources and services (n = 27) said some activity had continued or would continue, and 80% of grantees delivering frontline services (n = 49) said their work had continued/would continue, 35% at the same level and 45% at a reduced level.

Around half of those delivering action research (n = 15), training (n = 22) and onward grant-making (n = 21) also reported some activity had continued or would continue. Given the majority of survey respondents were from funding rounds prior to 2020/2021, this suggests some sustainability of projects beyond the funding period.

Those who said some activity had or would continue post-TTF funding were asked about other funding streams accessed. While the small numbers of respondents limits further analysis, three activities emerged as more likely to continue: frontline service provision (n = 39), signposting of resources and services (n = 25) and awareness raising and communications campaigns (n = 18). Table 5 shows the funding streams accessed to support continuation, with funding from private philanthropic trusts/foundations or other organisations being most commonly reported, particularly for frontline services (49% of those saying activity would continue), followed by government grants, charitable activities, and donations and legacies.

Table 5: Funding streams accessed to enable continuation of project delivery

| Streams accessed to enable continued delivery | Frontline services | Signposting of resources/services | Awareness raising/comms. Campaigns |

|---|---|---|---|

| Funds and grants from private philanthropic trusts/foundations or other organisations | 49% | 36% | 22% |

| Government grants | 33% | 24% | 22% |

| Charitable activities | 23% | 24% | 17% |

| Donations and legacies | 23% | 12% | 17% |

| Government contracts | 18% | 16% | 17% |

| Funds or grants from other sector organisations | 15% | 12% | 17% |

| Funds and grants from funding bodies | 13% | 16% | 22% |

| Other trading activities | 10% | 12% | 0% |

| Other | 10% | 12% | 11% |

| Don’t know | 5% | 8% | 6% |

| Base: Those with continuing activity (n = ) | 39 | 25 | 18 |

Source survey question: Which funding sources have you accessed to enable you to continue these activities? (Base all continuing to deliver frontline services past the end of the funding period: n = 39; Base all continuing to deliver signposting of resources and services: n = 25; Base all continuing to deliver awareness raising and communications campaigns: n = 18)

A total of 14 successful applicants in the 2020/2021 and 2021/2022 funding rounds received dedicated organisational sustainability funding from DCMS. Three of these were consulted as part of the evaluation, as described below.

A £1.2 million project to update a pre-existing app with new content (including specific content for women and girls from ethnic minority backgrounds) to support women through their maternity journey and improve maternity outcomes received sustainability funding of £75,088 to increase the capacity to train and grow their engagement team and to ensure that the business-wide operational activity had the capacity to train, support and embed new project staff and processes into the charity.

A £600,000 project to extend rape crisis trauma-informed frontline services to specific women and girls from ethnic minority backgrounds and women with disabilities received sustainability funding of £10,000 to improve their IT processes, specifically to allow each delivery partner to implement a secure multi-language web form on their websites enabling first language survivors to make referrals at a time convenient to them.

A £2.3 million project providing match funding grants to charities for women and girls received sustainability funding of £10,000 towards building digital fundraising skills, providing leadership training for women staff members and establishing a philanthropic community specifically targeting causes that help women and girls.

5. Overview of impact evaluation

The TTF evaluation was designed to understand the outcomes and reported and perceived impacts of TTF, including any unintended consequences. Based on the TTF logic model, reported and perceived outcomes and impacts were explored at project, organisation and sector levels, drawing on data from the TTF grantee survey (Appendix 6), public data from the Charity Commission (Appendix 5) and findings from the QuIP (Appendix 8). Some insight was also provided on individual level outcomes self-reported by grantees in their End of Grant reports (Appendix 2 and Appendix 3). However, End of Grant reports were highly variable in their content, coverage and detail, so were of only limited value in evidencing outcomes.

5.1 Intended outcomes and impacts

At the time of set-up and throughout delivery, the Fund did not have a clearly defined logic model with a set of specific intended project outcomes and impacts that projects funded would contribute to and achieve. Instead, funding applications aimed to address a wide variety of issues in a broad range of ways. The TTF logic model retrospectively identified a set of common short-term and long-term project outcomes and intended impacts at the sector, organisation and individual levels.

The bid review found that the most common intended short-term project-level outcomes were related to improving access to quality support (81%) and improving abilities/skills to support women in need (74%). Long-term outcomes relating to improved physical and mental health management were included in many bids (70%). Bids also sought to improve confidence (51%) and increase help-seeking (49%) in women and girls. Over half (55%) of bids sought to reduce the risk and/or experience of violence for women and girls as a long-term impact of their project. The next most common impact identified was related to women and girls being able to act as their own agents (54%).

Fund stakeholders described expecting to see a series of broad overarching impacts for individual beneficiaries and the VCS, including:

-

having a positive impact on women and girls facing disadvantage and harm

-

having a positive impact on the VCS by extending the types of initiative available to women and girls, and strengthening local services from specialist and community organisations

-

creating a lasting impact on the VCS by providing sustainable and/or ‘snowball’ interventions (new interventions emerging from/inspired by the original funded activities); increased sector resources, knowledge, capacity and capability; and improved networks

5.2 Outcomes and impacts for women and girls

The TTF logic model outlines a range of intended outcomes for individuals, including improved access to resources, guidance and shared learning; improved physical and mental health management; improved access to quality support; increased help-seeking; improved confidence; reduced risk or experience of violence and harm; and women and girls are empowered to act as their own agents.

Grantees reported a range of short-term outcomes for beneficiaries, but the evidence provided is largely anecdotal, with commonly cited outcomes including:

-

increased access to services during the TTF funding period

-

improved confidence among women and girl beneficiaries of TTF services

-

enabling women/girls to act as their own agents

-

changes in the risk/experience of violence and harm among women and girls

The most commonly reported long-term outcomes by grantees related to physical and mental health management for women and girls. The short-term outcomes most commonly reported by grantees related to improved access to quality support for women and girls. An overview of self-reported outcomes identified by grantees is outlined in Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 6: Reported short-term outcomes

| Reported short-term outcomes | Percentage of projects |

|---|---|

| Improved access to quality support for women and girls | 44% |

| Improved sector partnerships and organisational linking | 42% |

| Improved ability and skill to support women in need | 35% |

| Improved access to resources, guidance and shared learning | 34% |

| Improved access to quality support for women and girls | 44% |

| Improved sector partnerships and organisational linking | 42% |

| Improved ability and skill to support women in need | 35% |

| Improved access to resources, guidance and shared learning | 34% |

Table 7: Reported long-term outcomes

| Reported long-term outcomes | Percentage of projects |

|---|---|

| Physical and mental health management | 39% |

| Improved confidence of women and girls | 37% |

| Increased help-seeking by women and girls | 20% |

| Improved VCS knowledge and increased assets | 31% |

| Physical and mental health management | 39% |

| Improved confidence of women and girls | 37% |

| Increased help-seeking by women and girls | 20% |

| Improved VCS knowledge and increased assets | 31% |

Table 8: Reported impacts

| Reported impacts | Percentage of projects |

|---|---|

| Reduced risk and/or experience of violence and harm for women and girls | 21% |

| Women and girls being able to act as their own agents | 25% |

| VCS shift from response to prevention | 21% |

| Reduced risk and/or experience of violence and harm for women and girls | 21% |

| Women and girls being able to act as their own agents | 25% |

| VCS shift from response to prevention | 21% |

The case studies provided anecdotal examples of outcomes for women and girls and how their feedback showed how they had been supported by TTF services – for example improvements in mental health and financial resilience, or through the provision of safe accommodation and training for survivors of abuse (which some service users stated had helped save their lives). Similarly, many QuIP participants claimed TTF contributed to improved outcomes for the women and girls they supported, most commonly by increasing their confidence and self-esteem; ability to act as own agents; increased knowledge and skills; improved peer relationships; and improved service access:

The girls have felt empowered from it. They felt like they had a voice.

– QuIP participant

Figure 1 provides a visual representation (”causal map”) of the factors related to TTF leading to improved outcomes for women and girls, as identified in the QuIP. Detail on how to interpret QuIP causal maps is provided in Appendix 8, Section 8.2.4.

Figure 1: Path tracing the impacts of TTF on improved outcomes for women/girls

The case studies spoke about how TTF project activities had helped raise awareness among the general public and the wider VCS regarding the issues facing women and girls. For example, one case study identified that their outreach activities had increased awareness of the genetic risk for ovarian cancer among both government bodies and the general public. In a few cases, TTF projects were felt to have contributed to wider policy developments. For example, one project described how their research had contributed to significant policy changes, such as the recognition of economic abuse in the Domestic Abuse Act and the inclusion of economic abuse in the Financial Conduct Authority’s Code of Conduct.

5.3 TTF outcomes and impacts identified at an organisational and project level

The TTF logic model identified that the Fund aimed to achieve organisational level outcomes in relation to improved skills and abilities to respond to the needs of women and girls. The impact evaluation provides some evidence suggesting positive outcomes in this area.

5.3.1 New workstreams funded and services improved

TTF funding enabled new projects and areas of work and, in some cases, new beneficiaries and beneficiary groups to be reached. The TTF grantee survey identified that grantees and onward grantees agreed TTF funding helped organisations reach new beneficiaries (90%) and begin new activities (79%). Examples of new areas of work include:

-

establishing new, trauma-informed service provision

-

setting up a refuge for a group otherwise not provided for (women with no recourse to public funds (NRPF))

-

exploring new housing models for victims of modern-day slavery

-

piloting new research on genetic mutations causing ovarian cancer

-

a project developing a new app to support those suffering from intimate image abuse

-

a programme to enhance oracy and literacy skills for girls in alternative education settings

Some grantees reported that TTF had helped them improve the quality of their existing services, expanded their existing activities and increased their capacity, with 77% of survey respondents agreeing that TTF funding had helped them improve service quality by:

-

funding new staff positions, including in delivery, managerial and consultancy roles

-

changing ways of working to meet needs better

-

adding components/expanding the reach of activities or services to new groups or areas

-

enabling sector partnerships and increasing organisational capacity

Most QuIP participants also claimed that TTF funding had contributed to improving their activities or services, again through establishing new activities or services or developing those already in place. As Figure 2 shows, some participants directly attributed improvements in activities and services to TTF funding, further strengthening provision across the VCS. Others discussed intermediary facilitators, such as partnerships, increased capacity and improved access to learning.

Figure 2: Path tracing the impacts of TTF on improved activities/services

A few QuIP participants delivering onward grants noted how the flexibility of the TTF enabled them to be creative and provided a level of flexibility described as ‘quite unique’ and ‘rare’.

Many TTF funded projects considered it unlikely their activities would have taken place without TTF funding. Over half of all survey respondents (58%) said they would not have been able to deliver their TTF activities at all, while 36% considered they would have been able to deliver some elements but on a reduced scale. Just 3% of respondents felt they could have delivered the same activities at the same scale without TTF funding.

5.3.2 Improved capability and skills to support women

Many grantees indicated that TTF funding had both increased their staffing capabilities and enabled skills development. Positive outcomes in terms of increased staff capabilities are reflected in the analysis of project monitoring and evaluation reports. Here, 35% of organisations reported delivering outcomes in relation to improved ability and skill to support women/girls in need. This was reflected in the QuIP findings, where one participant had received training from their onward grant-maker to improve skills and confidence in delivering wellbeing sessions for young women.

Analysis of expenditure trends suggests grantee organisations spent more on governance in years they received TTF funding, compared to what would have been expected without TTF. An analysis of organisations’ expenditure used multilevel regression models to explore estimated average change in spending trends over the years in which they received TTF funding (see Appendix 5 and Section 3.11.1).

The models applied provide some evidence to suggest that direct grantees spent more on governance during the years in which they received TTF disbursements. On average, expenditure on governance was 14% higher in years when TTF funding was received than would be expected based on the charities’ previous expenditure. While it could be suggested this was due to TTF’s focus on onward grant-making and the associated governance costs, this increase was detected across the wider cohort and suggests that TTF funding contributed to strengthening organisational systems and procedures.

5.4 TTF outcomes and impacts at a sector level

In line with the outcomes in the TTF logic model, the evaluation explored financial trends within the VCS, outcomes related to partnerships and networks, and sector knowledge and assets.

5.4.1 Financial trends across the VCS through the TTF delivery period

TTF funding was available to eligible organisations during a financially challenging time for the VCS. Some grantees highlighted the challenging funding context they operated within as a contextual backdrop for the TTF funding period. Most direct and onward grantees indicated that the overall picture of VCS funding has worsened over the last decade (64% of survey respondents), while for 17% the picture was unchanged and for 13% had improved.

Similarly, the majority of grantees disagreed that there was sufficient funding available to the sector (84%, including 42% who disagreed strongly), and raised additional issues including a lack of prioritisation for particular sectors or organisations (51%) and increased competition for funding (49%). Findings from the QuIP reiterated these financial challenges, describing an overall decline in sector funding due to government funding cuts, the COVID-19 pandemic and the cost-of-living crisis. Where grants were available, they were reported to be smaller, with increasingly complex application requirements reportedly reducing access to funding opportunities. This suggests that TTF funding was welcomed by eligible applicants:

I think that it’s a real shame that there is nothing to replace the Tampon Tax Fund. It’s been incredible to see the work that we’re doing.

– QuIP participant

It would be nice to have another Tampon Tax Fund … it was good that they decided to use it for women’s services, but it needs to be replaced.

–QuIP participant

On the other hand, the financial challenges identified by participants at the time of the research could also suggest that, despite the potential financial impacts of TTF on the VCS, financial challenges have continued to be felt by grantee and onward grantee organisations.

Since 2016, TTF has provided a significant level of funding for VCS organisations focusing on the issues that face women and girls. By the end of TTF, a projected £86.25 million will have been provided to VCS organisations via the Fund. As seen in Section 3.3, TTF has been successful in reaching a diverse range of organisations working with women and girls. Compared with the wider VCS, direct grantees have been more commonly categorised on the Charity Commission database as helping “children and young people” and “other defined groups” as compared with “the general public”, which could indicate that TTF has reached its intended target organisations.

The significance of TTF funding is further emphasised by the fact that TTF represented a substantial proportion of the financial resources of some grantees in the year(s) they received grants. The median income of the direct grantees ranged from just under £1 million for the 2016/2017 cohort to £9.4 million for the 2019/2020 cohort. The TTF median income of the direct grantees in each TTF funding round is presented in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Median income of TTF grantees, by cohort

The change in financial criteria for applying to TTF (see Section 3.3.1 is reflected in the variety of direct grantees by size. Analysis of the accounts of direct grantees shows TTF represented:

-

over 10% of the organisation’s annual income for more than a third of TTF grantees

-

over 20% of the organisation’s annual income for one in five TTF recipients

Figure 4 shows the share of reported gross income accounted for by TTF across the direct grantees. The TTF grant accounted for less than 50% of gross income for nearly all grantees, reflecting the requirement since 2017/2018 that bids should not exceed 50% of income.

Figure 4: Proportion of annual gross income from TTF funding

| % of gross income from TTF funding | Less than 5% | 5-10% | 11-20% | 21-50% | More than 50% | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of TTF grantees | 44% | 19% | 16% | 18% | 3% | 100% |

Similarly, analysis of onward grantee financial data highlights that onward grants made a sizeable contribution to these organisations’ resources.

For 10% of onward grantee organisations matched to published accounts from the Charity Commission for England and Wales (CCEW), the onward grant made up a quarter or more of their reported annual income (‘90th percentile’ means that, for 90% of the organisations, the proportion of TTF grant to income falls below that value).

For the median recipient organisation, the onward grant made up 4% of their income that year (the median, or 50th percentile, means that for half of the organisations the proportion falls below that value).

Table 9: Proportion of onward grantees’ annual income accounted for by the TTF onward grant

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of onward grants matched to CCEW data | 33 | 65 | 291 | 182 | 77 | 11 | 659 |

| Median proportion of income | 21% | 15% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 10% | 4% |

| 10th percentile | 8% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | < 1% | 1% |

| 90th percentile | 58% | 63% | 18% | 17% | 18% | 14% | 25% |

| Number of onward grants matched to CCEW data | 33 | 65 | 291 | 182 | 77 | 11 | 659 |

| Median proportion of income | 21% | 15% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 10% | 4% |

| 10th percentile | 8% | 1% | 1% | 1% | 1% | < 1% | 1% |

| 90th percentile | 58% | 63% | 18% | 17% | 18% | 14% | 25% |

Analysis of grantee accounts shows their annual gross income was on average 12% higher in years where they received a TTF disbursement than would have been predicted without it. However, due to other factors, it has not been possible to confirm attribution to TTF. Overall, the median income reported by direct grantees has more than doubled since 2012. For smaller organisations (where the TTF grant represented more than 14% of their annual income), the rate of growth of income was higher in the years after receiving the grant compared with the trend receipt. However, this cannot be directly attributed to TTF, as other factors will have influenced organisations’ incomes over the same period.

Kantar Public ran a multilevel regression model (Appendix 5) to explore the estimated annual gross incomes reported by charities, considering differences between years as well as their available organisational characteristics. This showed the reported income of direct grantees was on average 12% higher in years when they received TTF funding than would be predicted without TTF. This difference still cannot be causally attributed to TTF, as there are many other differences between charities and years which the model cannot account for. However, it provides some evidence that the resources available were notably higher in years when grantees received TTF than would be otherwise expected.

Figure 5: Median income of all direct grantees: 2012 to 2021

An analysis of income trends indicates that TTF could have represented additional income rather than displacing other sources. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that other factors influenced income in the year(s) grantees received TTF funding. One assumption of the TTF logic model was that TTF funding represented additional funds for the VCS rather than displacing other funding. This assumption was explored through an analysis of grantees’ incomes and sector financial trends over the TTF delivery period. However, an assessment of funding displacement is difficult to assess from published accounts, given the variability of charity incomes between years.

5.4.2 Establishing new financial connections

The TTF onward grant model extended the reach of the Fund, enabling a wider network of financial connections between organisations. Onward grants generally successfully reached smaller organisations – an outcome identified in the TTF logic model. Through the TTF onward grant-making model, at least 20 direct grantees have distributed 1,622 onward grants to 1,230 organisations since the 2016/2017 funding period, with an estimated value of over £30 million (around one-third of all TTF funds). An analysis of financial records showed that onward grants enabled TTF funding to be further distributed to small and medium-sized organisations. Using a matching process (Appendix 8), the median income of onward grant recipients was identified as around £300,000, with around 80% of recipients reporting incomes of between £45,000 and £1.4 million. This was considerably lower than the income reported by central TTF recipients (a median of £1.5 million).

That said, onward grants were awarded to a notable number of large organisations. About 18% of the total value of the onward grants before the 2021/2022 funding period went to organisations with annual incomes above £2 million, suggesting that the intention of redistributing funding to smaller organisations was not fully met.

In some cases, grantees involved in onward grant-making provided more grants compared with years where they did not receive TTF funding, suggesting that TTF enabled additional capacity for grant-making. An analysis of the financial accounts of a subset of eight grantee organisations for which DCMS shared onward grant data shows that, in some cases, the number of grants made (whether TTF or otherwise) increased in the years these organisations accessed TTF funding. In particular, one grantee’s accounts list 128 grants in 2018 (101 associated with TTF), which is considerably more than in other years. Similarly, accounts for another grantee list 169 grants in 2019 (73 associated with TTF), again more than in other years. As 85% of the organisations involved in TTF onward grant-making were established grant-making organisations (10% with the sole purpose of providing onward grants), this suggests that TTF provided additional capacity to these organisations.