Survey of Child Support Agency Case Closure Outcomes

Published 14 July 2022

DWP research report no. 1016.

A report of research carried out by IFF Research on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2022.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our GOV.UK website

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published July 2022.

ISBN 978-1-78659-400-6

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Summary

This is a report of findings from a study about the child maintenance outcomes of separated parents who previously had cases with the Child Support Agency. The research was among ‘compliant (system)’ cases and ‘enforcement’ cases. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) commissioned IFF Research to carry out the research between June 2017 and April 2019.

The research complements previous research carried out in 2014-2016 using a similar methodology among ‘nil assessed’, ‘non-compliant’ and ‘compliant (admin)’ cases.

Executive summary

In 2012, the Government set out its vision for a new child maintenance system, where collaborative family-based arrangements (FBAs) between separated parents would be encouraged wherever possible.[footnote 1]

As part of these reforms, all Child Support Agency (CSA) cases with on-going maintenance liabilities have been closed (commencing in 2014 and completing in 2018) and the CSA has been replaced with a new statutory Child Maintenance Service (CMS).[footnote 2]

The aim of this research was to measure the child maintenance outcomes for parents whose CSA cases were closed. This programme of research built on an earlier programme of research among parents whose cases were in the first three segments to be closed. This research specifically covers outcomes for those in the final two segments to be closed i.e. the Segment 4 ‘compliant (system)’ and Segment 5 ‘enforcement’ cases. Segment 4 consists of cases that were handled by the CSA’s IT systems. All cases in this segment were compliant and did not have any ‘enforcement’ action in place. Segment 5 cases are ‘enforcement’ cases where the method of payment was by Deduction from Earnings Order or where other ‘enforcement’ action was in progress.

Main Findings:

- By a point three months after their case was closed with the Child Support Agency, most families had some form of alternative agreement in place.

- Whereas previously all of these cases would have involved administration by the CSA, three months after their case was closed, under half were reliant on the new CMS to administer their arrangement.

- The change in systems has encouraged families to set up Family-Based Arrangements. Two fifths of ‘compliant (system)’ cases (40%) and a quarter (26%) of ‘enforcement’ cases had an FBA in place 12 months after case closure.

- By 12 months after their case was closed, Receiving Parents with Family-Based Arrangements and Direct Pay arrangements generally found these arrangements to be working well.

- The likelihood of payments being made on time and in full, and the Receiving Parent perceiving the arrangement to be working well, were considerably lower for arrangements set up through Collect and Pay, compared to those set up through Direct Pay, or FBAs with a financial element.

- 14% of families with ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 29% of those with ‘enforcement’ cases did not have any form of arrangement in place at three months after the closure of their case (and a similar proportion did not have an arrangement in place at 12 months). A small proportion of these were either in the process of setting up, or had tried unsuccessfully to set up, an arrangement with the CMS. The main reason given for not having an arrangement was a belief that the paying parent would not pay.

- Often, where a Collect and Pay arrangement was set up, this was underpinned by the Receiving Parent’s belief that the Paying Parent would not willingly or reliably pay the requisite maintenance.

- There is some evidence to suggest that the charges that apply to Collect and Pay arrangements are encouraging some Receiving parents to try Direct Pay arrangements, when they might have otherwise had a preference for Collect and Pay.

- However, the application fees or service charges associated with the CMS arrangements do not seem to be the main reason for not setting up any arrangement.

New Child Maintenance Arrangements

Approximately three months after case closure, the majority of Receiving Parents had a new maintenance arrangement in place. The proportion of parents with new arrangements was higher among those in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment (86%) compared with those in the ‘enforcement’ segment (71%).

Family Based Arrangements (FBAs) were the most common type of arrangement in place after three months for families with a ‘compliant (system)’ case. These cases were significantly more likely than ‘enforcement’ cases to have an FBA (45% compared to 27%) or a Direct Pay (29% compared to 19%) arrangement in place after three months. Conversely, ‘enforcement’ cases were more likely to have a Collect and Pay arrangement (22% compared to 9%) after three months.

In nearly all cases (93% in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment and 90% in the ‘enforcement’ segment), the FBAs that families had put in place involved providing a regular set amount of money and hence could be considered a financial FBA (as opposed to an arrangement based purely on other forms of shared responsibility such as sharing childcare or ad-hoc financial payments).

Overall, the type of arrangements in place remained broadly stable at both the 3 month and 12 month points.

The proportion with no arrangement in place 12 months after their case was closed stood at 16% for the ‘compliant (system)’ segment and 24% for the ‘enforcement’ segment. The main reason that receiving parents gave for not having an arrangement in place was that they did not believe that the paying parent would pay.

Deciding on new arrangements

Around half of Receiving Parents (45% in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment and 58% in the ‘enforcement’ segment) mainly made the decision on the new arrangement themselves, while the decision was made jointly between the Paying and Receiving Parents in 33% of ‘compliant (system)’ and 22% of ‘enforcement’ cases. Only a minority of arrangements were decided by the Paying Parent predominantly, and even fewer by the CMS (5%).

Wherever possible, the government would like parents to make arrangements for child maintenance themselves without involving the CMS. Hence Receiving Parents who had a CMS arrangement were asked to give the main reason why they had chosen to have a CMS arrangement instead of an FBA. The two most common main reasons given were because:

- They felt the Paying Parent would not pay otherwise, and;

- They thought the Paying Parent was more likely to pay if the CMS was involved.

These cases had been paying at least some of their liability under their CSA arrangement but for some Receiving Parents there was a lack of confidence that the Paying Parent would continue to pay.

Conversely, those who had an FBA in place were asked the main reason for having an FBA instead of a Direct Pay arrangement. Reasons given were generally positive:

- Most commonly, Receiving Parents chose to have an FBA because they thought it was easier to make than a Direct Pay arrangement.

- Other factors given as the ‘main reason’ included that Paying Parents were able to communicate in such a way that meant the CMS was not necessary: that Paying Parents had a ‘good relationship’ or that they were able to talk about money.

In qualitative interviews, Paying Parents with FBAs also mentioned that they felt that there was less stigma attached to having an FBA than an arrangement through the CMS and that it felt like a more grown-up arrangement.

Where parents are using the CMS, wherever possible it is preferable for them to use the light touch Direct Pay service rather than a Collect and Pay arrangement. Hence, Receiving Parents who had a Collect and Pay arrangement were all asked what the main reason was for selecting Collect and Pay instead of a Direct Pay arrangement. By far the most common reason was that the Paying Parent had a history of not paying maintenance (mentioned by around three-fifths as the main reason) indicating that Receiving Parents chose Collect and Pay in order to guarantee they would receive maintenance payments. The fact that Collect and Pay cases were less likely than Direct Pay cases to receive maintenance payments in full and on time indicates that Paying Parents’ record of not paying maintenance often persist with the CMS.

There are fees associated with using the new CMS service. A £20 application fee applies to both Direct Pay and Collect and Pay services, although it is waived for victims of domestic abuse. In addition, for the Collect and Pay service, an ongoing charge of 20% on top of the maintenance liability and 4% from the maintenance received applies. Generally, the payment of the £20 application fee fell to the Receiving Parent, but most found it relatively easy to afford. The Receiving Parent paid in around six in ten (56% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 63% of ‘enforcement’ cases) instances, while the Paying Parent paid in only a small minority. In around one quarter of cases, neither parent paid the fee.

A minority of Receiving Parents who were using the Direct Pay service rather than Collect and Pay stated that they had made this decision mainly to avoid the fees associated with Collect and Pay (22% of ‘compliant (system)’ and 17% of ‘enforcement’ cases using Direct Pay).

Effectiveness of arrangements

In order to determine how effective new child maintenance arrangements were perceived to be, the survey asked Receiving Parents about: the frequency of receiving all of the maintenance that was due, the frequency that payments were made on time and how well they felt that the new arrangement was working.

Receiving Parents spoke positively about FBA and Direct Pay arrangements, but less so about Collect and Pay arrangements. Improvements were apparent between the three and 12 month points.

12 months after case closure the majority of Receiving Parents with a new arrangement in place reported that they usually received all of the maintenance that was due. This varied by type of arrangement:

- Of Receiving Parents with a financial FBA, 89% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 80% of ‘enforcement’ cases usually received all of the money due;

- Of Receiving Parents with a Direct Pay arrangement, 84% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 70% of ‘enforcement’ cases usually received all of the money due; and

- Of Receiving Parents with a Collect and Pay arrangement, 43% of those in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment and 34% in the ‘enforcement’ segment usually received all of the money due. At the 12 month point, 64% of Receiving Parents in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment with a new arrangement in place and 47% of those in the ‘enforcement’ segment reported that payments were always made on time. At 12 months, 77% of Receiving Parents in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment with an arrangement in place and 57% of those in the ‘enforcement’ segment reported that it was working either ‘very’ or ‘fairly’ well. This also varied by type of arrangement:

- Receiving Parents with an FBA were most likely to report it to be working well (84% of those in the ‘compliant (system)’ and 83% in the ‘enforcement’ segment);

- Receiving Parents with a Direct Pay arrangement were less likely to report it to be working well (79% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 60% of ‘enforcement’ cases); and

- The proportion of Receiving Parents with a Collect and Pay arrangement who reported it to be working well was lower still (36% of the ‘compliant (system)’ and 29% of the ‘enforcement’ segment).

In terms of the frequency of receiving all the money owed and in terms of Receiving Parents ratings of how well the arrangement was working, findings were considerably more positive after 12 months than after three months. There was little change in terms of the timeliness of payments.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Child maintenance | Financial or other support that the Paying Parent gives to the person with care generally, but not always the other parent, for the care of the children. |

| Child maintenance arrangement | The agreed amount and way in which a Paying Parent pays the Receiving Parent child maintenance money. |

| Child Maintenance Options[footnote 3] (‘CM Options’) | A free service that provides impartial information and support to help separated parents make decisions about their child maintenance arrangements. All parents who want to use the Child Maintenance Service to make maintenance arrangements must first talk with CM Options on the phone before accessing the Child Maintenance Service. |

| Child Maintenance Service (CMS) | Government agency Set up in 2012 to administer the statutory child maintenance scheme. The Service replaced the Child Support Agency. |

| Child Maintenance Service application fee | A £20 application fee payable by parents using the Child Maintenance Service. Parents who are under 18 or who report domestic abuse are exempt from this fee. |

| Child Support Agency (CSA) | Government agency that administered the former statutory child maintenance schemes. Applications closed in 2013 following the introduction of the CMS. The closure of the CSA commenced in December 2014, and the last cases with ongoing liabilities closed in December 2018. The CSA are now dealing with the remaining cases with historic debt. |

| Collect and Pay | A legally binding child maintenance arrangement set up by the CMS. The CMS calculates the amount of maintenance, then collects the payment from the Paying Parent and pays it to the Receiving Parent. There are ongoing collection charges for use of the Collect and Pay service, payable by both the Paying Parent (20 per cent on top of the maintenance amount), and the Receiving Parent (4 per cent taken out of the amount of maintenance). Collect and Pay is generally used in circumstances such as: (i) where the Paying Parent has failed to pay maintenance or failed to stick to a Direct Pay arrangement; or (ii) where one parent does not want the other to know their personal details. |

| Compliant (admin) cases | For the purposes of case closure, Child Support Agency cases have been categorised into five segments. Compliant (admin) are cases which are handled manually, rather than on the CSA’s IT systems. This could be for a number of reasons including the complexity of the case or technical IT issues. All cases in this segment are compliant (i.e. making some payment) and do not have any ‘enforcement’ action in place. |

| Compliant (system) cases | For the purposes of case closure, Child Support Agency cases have been categorised into five segments. ‘Compliant (system)’ cases are one of these segments and are handled by the CSA’s IT systems, where some payment is being made and where no ‘enforcement’ action is in place. |

| Court Order | Where the Receiving Parent privately takes a case against the Paying Parent to a family court to set and enforce the payment of child maintenance. |

| Direct Pay | A legally binding child maintenance arrangement set up by the Child Maintenance Service, where the Child Maintenance Service calculates the amount of maintenance that should be paid, and parents make their own arrangements for payments. The CMS simply provides the calculation and no further use of the service is required. Direct Pay can be chosen by either parent with the other’s agreement. A £20 application fee is charged for this service, although this may be waived for victims of domestic abuse. Neither parent pays collection fees under Direct Pay. The CMS is legally required to place parents on Direct Pay in the event that one of them prefers this and the other disagrees, unless there is clear current evidence the Paying Parent is unlikely to pay. |

| Enforcement cases | For the purposes of case closure, Child Support Agency cases have been categorised into five segments. ‘Enforcement’ cases are one of these segments and are cases where the method of payment is by Deduction for Earnings Order/Deduction from Earnings Request/ Regular Deduction Order; and where an ‘enforcement’ action is currently in progress including liability orders (and all subsequent action that flows from such orders), lump sum deduction orders, freezing orders, setting aside of disposition orders and their Scottish equivalents. |

| Family-based arrangement (FBA) | A child maintenance arrangement which is made between the two parents without any involvement of the Child Support Agency or the Child Maintenance Service. FBAs may sometimes be known as private or voluntary arrangements. An FBA could involve regular financial payments, or could be other support for the child such as buying clothes, paying school fees etc. An FBA could be completely informal or could be a written agreement. No fees or charges apply to an FBA. |

| Nil-assessed cases | For the purposes of case closure, Child Support Agency cases have been categorised into five segments. Nil-assessed cases are one of these segments and are cases where the Paying Parent has a liability for maintenance, but the amount of liability was £0. This could be because the Paying Parent was a student, in prison or in a care home or shares the care of a qualifying child for at least 52 nights a year and they are in receipt of a specified benefit or pension at the time of the assessment. |

| Non-compliant cases | For the purposes of case closure, Child Support Agency cases have been categorised into five segments. Non-compliant cases are one of these segments and are cases where the Paying Parent has a liability for maintenance and the amount payable is greater than £0, but where no payments have been made in the last three months. This segment excludes cases where payment is enforced by the CSA. |

| Paying Parent | A separated parent who is not the primary caregiver for his/her children, and therefore has a responsibility to pay child maintenance (regardless of whether they are actually making payments). Sometimes these parents are known as non-resident parent or supporting parent. Under the old system, these parents were called ‘non-resident parents’. |

| Receiving Parent | A separated parent who provides main day-to-day care for his/her children and therefore has a right to receive payments from the Paying Parent (regardless of whether they are actually receiving payments). Sometimes these parents are known as parent with care or resident parent. Under the old CSA system these parents were called ‘Parents with Care’. |

1.Introduction

This report presents findings from a study measuring the child maintenance outcomes of separated parents whose cases with the Child Support Agency (CSA) were closed in the transition to the new Child Maintenance Service (CMS).

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) commissioned IFF Research to carry out the research with the aim of assessing the child maintenance outcomes for parents approximately three and 12 months after the liability end date for their CSA child maintenance case. It sought to understand if new maintenance arrangements have been established, the types of arrangements set up and parents’ decision-making processes.

The study included two telephone surveys of Receiving Parents who previously had child maintenance cases with the CSA and were eligible for child maintenance going forward. The surveys were conducted between June 2017 and April 2019. The first telephone survey took place approximately three months after parents received a final letter from the CSA informing them that their CSA arrangement was due to end. The second survey took place nine months later, at around 12 months after the final letter was sent to parents. The research also included in-depth qualitative interviews with Paying Parents to capture their experiences of CSA case closure.

The research complements previous research carried out in 2014-2016 using a similar methodology with cases that were closed earlier in the CSA closure programme.

Background to the child maintenance reforms

In 2012, the Government set out its vision for a new child maintenance landscape, where collaborative family-based arrangements (FBAs) between separated parents would be encouraged wherever possible.[footnote 4]

As part of these reforms, all CSA cases with ongoing liabilities have been closed (commencing in 2014 and completed in 2018). The CSA has been replaced by a new statutory Child Maintenance Service (CMS) for all new applications.

The reforms aim to encourage parents to consider an FBA before making an application to the CMS. There are various support tools available to encourage more collaborative arrangements. Together with Child Maintenance Options – the ‘gateway’ to the CMS – the aim is to support parents to set up FBAs wherever possible. Where FBAs are not possible, parents can apply to the new statutory CMS service. Key features of the CMS include:

- A £20 application fee payable by the parent who applies to the CMS (except in extenuating circumstances).

- Two types of maintenance arrangement are available via the CMS:

- Direct Pay – the CMS calculates the amount payable and parents make the payments directly between themselves.

- Collect and Pay – where the CMS calculates the amount payable, collects payments from the Paying Parent and pays them to the Receiving Parent. To incentivise parents to use Direct Pay or make their own private arrangements, an additional ongoing charge of 20% to the Paying Parent and 4% to the Receiving Parent applies for Collect and Pay.

Previous CSA cases were divided into five segments for the case closure process:

1. Nil-assessed: These are cases where the Paying Parent had a liability for maintenance, but the amount of liability was £0.

2. Non-compliant: The Paying Parent was liable for child maintenance, but no payments had been made in the last three months.

3. Compliant (admin): These are cases which were handled manually, rather than on the CSA’s IT systems. This could be because of the complexity of the case or technical IT issues. All cases in this segment were compliant and did not have any ‘enforcement’ action in place.

4. Compliant (system): These are cases that were handled by the CSA’s IT systems. All cases in this segment were compliant and did not have any ‘enforcement’ action in place.

5. Enforcement: These are cases where the method of payment was by Deduction from Earnings Order / Deduction from Earnings Request / Regular Deduction Order; and where an ‘enforcement’ action is currently in progress including liability orders (and all subsequent action that flows from such orders), lump sum deduction orders, freezing orders, setting aside of disposition orders and their Scottish equivalents. All of these cases were categorised as ‘paying’ cases by the CSA, although they may not have been paying as much or as frequently as stipulated in their CSA arrangement.

This research covered Segments 4 and 5 (Segments 1 to 3 and part of Segment 4 were covered by the previous research).

Research aims

The aim of the research was to measure the child maintenance outcomes for parents whose CSA case had been closed. Specifically, this involved parents whose CSA case were in the ‘compliant (system)’ and ‘enforcement’ segments. Separated parents received three letters from the CSA informing them that the liability for their CSA arrangement would be ending. The first letter was sent six months in advance of the liability end date, the second letter a month in advance and the final letter one week before the liability end date. The research assessed outcomes for parents at approximately three and 12 months after the final notification letters were sent. Specifically, it measured:

- The proportion of parents with no new arrangement in place and those with a new arrangement in place (either an FBA, Direct Pay, Collect and Pay or a court arrangement); and

- The proportion of new arrangements that were paid on time, in full and whether the Receiving Parent perceived the arrangement to be working well.

To help understand the extent to which the CSA case closure process has encouraged parents to make FBAs, the research also assessed the decision-making processes behind deciding upon maintenance arrangements (including no arrangement).

Research methodology

This section outlines the design of the surveys of Receiving Parents and the qualitative research with Paying Parents.

Overall design of the surveys

A telephone survey of Receiving Parents was conducted approximately three months after the liability end date for their CSA arrangement. The survey took place between June 2017 and July 2018 and comprised interviews with 3,325 Receiving Parents.

A second telephone survey was conducted with Receiving Parents nine months later, approximately 12 months after the liability end date for the case. The 12 month survey took place between April 2018 and April 2019 and comprised interviews with 1,214 Receiving Parents. This 12 month survey included parents who had taken part in the previous three month survey and who had agreed to be re-contacted.

For the purposes of this report, the liability end date for the case is used as a proxy for closure of the CSA case, although technically the case remains open until all arrears are settled. Receiving Parents were sampled for the three month survey purely on the basis of their liability end date.

Sampling

Three month survey

For the three month survey a random sample of Receiving Parents was drawn from DWP Management Information data. For ‘compliant (system)’ cases, a random sample of Receiving Parents was drawn in six monthly tranches by DWP from its client records between June and November 2017. Each tranche included Receiving Parents whose CSA case had been closed approximately three months earlier – i.e. between March and August 2017. For ‘enforcement’ cases, a random sample of Receiving Parents was drawn in 13 monthly tranches between July 2017 and July 2018. Each tranche included Receiving Parents whose CSA case had been closed approximately three months earlier – i.e. between April 2017 and April 2018. Table 1.1 shows the numbers and proportion of each segment in the population compared with the issued sample.

Table 1.1 Overview of issued sample

| Segment | Population n | Population % | Issued sample n | Issued sample % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4. ‘compliant (system)’ | 316,308 | 78 | 7,691 | 48 |

| 5. ‘enforcement’ | 88,236 | 22 | 8,368 | 52 |

| Total | 404,544 | 100 | 16,059 | 100 |

12 month survey

Sample for the 12 month survey comprised Receiving Parents who had taken part in the three month survey and agreed to be re-contacted.[footnote 5] The 12 month survey covered ‘compliant (admin)’ cases closed between March and August 2017, and ‘enforcement’ cases closed between April 2017 and April 2018.

The issued sample consisted of 1,633 Receiving Parents with a ‘compliant (admin)’ case and 1,453 Receiving Parents with an ‘enforcement’ case.

Conducting the survey

All Receiving Parents sampled for the three month survey were sent an advance letter explaining the survey before being contacted. This gave them an opportunity to opt-out of the survey before telephone contact was made.

The questionnaire for the three month survey covered a number of topics related to Receiving Parents’ experiences of child maintenance since their CSA case closed. It was divided in to eight main sections as outlined below.

1. Household information, including: number of children in the household; eligibility for child maintenance from Paying Parent; age and current partner status of respondent.

2. Status of child maintenance arrangement, including: whether the respondent has an arrangement now and if so what type of arrangement is in place; when the arrangement started (i.e. before or after case closure); whether they are in the process of trying to make an arrangement; whether they have tried to make an arrangement which has since broken down and reasons for this.

3. How the current arrangement came about, including: who decided to have this type of arrangement, reasons for choosing particular types of arrangement over other types, and views on the affordability of the CMS application fee and Collect and Pay charges.

4. How the current arrangement works, including: amount of maintenance received, if it was paid on time and in full, and perceptions of how well the arrangement is working.

5. How well the previous CSA arrangement worked.

6. Relationship between Paying Parent and child/children.

7. Past and present relationship between the Receiving Parent and Paying Parent.

8. Socio demographic information, including: age of the Receiving Parent, ethnicity, household income and whether or not the Receiving Parent, Paying Parent and new partner (if applicable) are in employment.

The questionnaire for the 12 month survey asked a similar set of questions. All respondents were asked again the questions on household information, relationship between the Paying Parent and child/children, household income and work status. In addition, data was collected from all 12 month respondents about their current maintenance status. If a maintenance arrangement was in place, the survey ascertained the type of arrangement, when it had been established, the extent to which the new CMS application fee and Collect and Pay charges had influenced their decision to have a certain type of arrangement and other reasons for their decision to have a particular arrangement. If no arrangement existed, data was collected on reasons for this and whether an arrangement had been put in place since case closure but had since broken down. Data was also collected on how well the current arrangement was perceived to be working.

Interviews for the three month survey lasted an average of 20 minutes and interviews for the 12 month survey lasted around 11 minutes.

For the three month survey, the questionnaire was piloted prior to the mainstage survey. The pilot took place in July 2017 and involved 40 interviews with Receiving Parents whose case was closed in March 2017.

Response rates

A total of 3,325 Receiving Parents took part in the three month survey, comprising:

- 1,784 interviews with ‘compliant (system)’ cases; and

- 1,541 interviews with ‘enforcement’ cases. A total of 1,214 Receiving Parents took part in the 12 month survey, comprising:

- 625 interviews with ‘compliant (system)’ cases; and

- 589 interviews with ‘enforcement’ cases.

Table 1.2 and Table 1.3 detail the response rates for each of the surveys.

Table 1.2 Response rate for the three month survey

| Segment | ‘compliant (system)’ cases | ‘enforcement’ (cases) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample selected | 7,691 | 8,368 | 16,059 |

| Opted out | 201 | 217 | 418 |

| Issued to telephone unit | 7,490 | 8,151 | 15,641 |

| Unusable sample | 1,391 | 1,854 | 3,245 |

| Total with valid telephone number | 6,099 | 6,297 | 12,396 |

| Refusal | 799 | 1,183 | 1,982 |

| Fully productive interviews | 1,784 | 1,541 | 3,325 |

| Response rate (% of usable cases) | 29% | 24% | 27% |

Table 1.3 Response rate for the 12 month survey

| Segment | ‘compliant (system)’ cases | ‘enforcement’ (cases) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample selected | 1,633 | 1,453 | 3,086 |

| Unusable sample | 54 | 75 | 129 |

| Total with valid telephone number | 1579 | 1378 | 2,957 |

| Refusal | 72 | 46 | 118 |

| Fully productive interviews | 625 | 589 | 1,214 |

| Response rate (% of usable cases) | 40% | 43% | 41% |

Overall design of the qualitative stage

Thirty qualitative telephone interviews were carried out with Paying Parents whose CSA case had closed in September 2017 and were contacted for the research between January and March 2018 (i.e. between three and six months after case closure). The Paying Parents interviewed were those whose CSA case was in the ‘compliant (system)’ and ‘enforcement’ segments.

The aim of the qualitative interviews was to explore experiences of CSA case closure from the perspective of Paying Parents, namely:

- their experiences of the CSA case closure process;

- their understanding of the maintenance options available after case closure;

- the nature of the arrangements put in place after case closure; and

- their views on facilitators and barriers to sustaining maintenance arrangements.

Methodology of the qualitative study

Interviews were carried out by telephone. The interviews were guided by a topic guide and were designed to last around 30-45 minutes. To encourage participation, respondents received a £20 gift voucher as a thank you for their participation.

Paying Parents were purposively recruited to achieve diversity on a range of sampling criteria, particularly:

- CSA case history – whether parents were in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment or ‘enforcement’ segment.

- Current maintenance arrangement – whether parents had any arrangement in place and, if so, whether this was one made through the CMS (either Direct Pay or Collect and Pay), or an FBA.

A roughly even split was achieved in terms of case history and a reasonable level of diversity achieved in the types of new maintenance arrangements (if any) that were in place[footnote 6], and demographics (see Table 1.4 overleaf).

Table 1.4 Overview of achieved sample for the 30 qualitative interviews

| Sampling criteria | Achieved sample |

|---|---|

| CSA case history | |

| ‘compliant (system)’ | 16 |

| ‘enforcement’ | 14 |

| Maintenance arrangement | |

| No arrangement | 5 |

| Direct Pay | 9 |

| Collect and Pay | 5 |

| Family based | 11 |

| Income | |

| Under £16,000 | 5 |

| £16,000 - £23,999 | 6 |

| £24,000 - £29,999 | 8 |

| £30,000 - £39,999 | 3 |

| £40,000 - £49,999 | 5 |

| £50,000+ | 2 |

| Unknown | 1 |

| Age | |

| 18-29 | 0 |

| 30-39 | 10 |

| 40-49 | 13 |

| 50+ | 7 |

Weighting and interpreting results in this report

Data from the quantitative survey have been weighted to be representative of the overall population of ‘compliant (system)’ and ‘enforcement’ cases, based on characteristics such as gender, geography, number of eligible children and age. Weighting of the 12 month survey also takes into account technical issues such as non-response.

Due to rounding, percentage figures in tables and figures may not add up to exactly 100%. Unweighted base sizes are provided on tables and figures. Some base sizes in this report are relatively small, so it is particularly important to note the unweighted base size when drawing comparisons.

Sub-group analysis has been carried out for most variables to compare responses for parents in the different CSA case closure segments. Any findings reported in the text about differences between sub-groups have been tested for statistical significance and are significant at the 5% level, unless otherwise stated.

The symbols below have been used in tables and denote the following:

- [ ] to indicate a percentage based on fewer than 50 respondents;

-

- to indicate a percentage of less than 0.5%; and

- 0 to indicate a percentage value of zero.

Overview of the report

Following this introduction, the report comprises five substantive chapters, and a conclusions chapter.

- Chapter 2 reports on the new child maintenance arrangements of parents at three months and 12 months after their CSA case has closed. It also looks at the reasons why arrangements were sustained or not.

- Chapter 3 focuses on the decision-making processes of parents, including the reasons given for choosing different types of arrangement; the influence of the CMS application fee and Collect and Pay charges on decision making and the reasons why some parents did not have a maintenance arrangement in place.

- Chapter 4 looks at the nature of child maintenance arrangements at three months and 12 months. It reports on the proportion of maintenance paid, the timeliness of payments and the Receiving Parents’ overall perception of how well the arrangement is working.

- Chapter 5 details some conclusions that can be drawn from this research.

- Annex A examines the demographic profile of parents and their relationship with their ex-partner.

Findings from qualitative interviews with paying parents are included in relevant sections throughout.

2. New child maintenance arrangements

Chapter overview

This chapter looks at new child maintenance arrangements following the closure of the Child Support Agency (CSA). The types of arrangements in place were explored at both three months after case closure and at 12 months after case closure. The final section looks at the factors that Receiving Parents associated with arrangements being sustained.

Key Findings:

- The majority of receiving parents had a new maintenance agreement in place three months after case closure. Those in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment were more likely to have an agreement in place than those in the ‘enforcement’ segment.

- Parents in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment had more FBAs and Direct Pay arrangements in place than those in the ‘enforcement’ segment, who were more likely to have a CMS Collect and Pay agreement.

- There was only a small amount of movement in the proportion of parents who had an arrangement in place between the three and 12 month points. The proportion of parents in the ‘enforcement’ segment with an agreement in place rose slightly while for parents in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment, the proportion dropped slightly.

- The type of arrangements that parents had in place at twelve months was largely the same as it was at three months. Most parents had the same arrangement and while some moved from having an FBA or CMS arrangement to having no arrangement, a similar number did the reverse leading to little change to the overall picture.

- When asked why they had been able to maintain a successful arrangement, the most common main reason was the effectiveness of CMS ‘enforcement’ for CMS cases and reasons related to the attitude of the paying parent and then their ability to afford the payments for FBAs.

Child maintenance arrangements at three months and twelve months

The proportion of parents with arrangements

Approximately three months after case closure the majority of Receiving Parents had a new maintenance arrangement in place. The proportion of parents with new arrangements was higher among those in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment (86%) compared with those in the ‘enforcement’ segment (71%).

Of those without a new arrangement in place at the time of the 3 month survey, a minority (13% among ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 14% among ‘enforcement’ cases) stated that they were in the process of setting up an arrangement (equating to 2% of all Receiving Parents in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment and 4% of Receiving Parents in the ‘enforcement’ segment).

There was not much change in the overall proportion of Receiving Parents with a new arrangement in place between the points three and 12 months after case closure. At the 12 month point, the proportion of parents in the ‘enforcement’ segment with a maintenance arrangement in place had increased slightly (to 76%), whereas the proportion of parents in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment with an arrangement had decreased slightly (to 84%).

Among Receiving Parents without a new maintenance arrangement in place at 12 months, a small proportion stated that they were in the process of trying to set one up. This was higher among parents in the ‘enforcement’ segment (13%) compared with the ‘compliant (system)’ segment (7%).

The proportion of Receiving Parents with new arrangements in place was higher among those with higher annual household incomes for those in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment. This pattern was evident at both the three and 12 month points. As Table 2.1 shows for the 12 month situation, this variation by income was less apparent for those in the ‘enforcement’ segment.

Table 2.1 Maintenance arrangement by household income and segment after 12 months

Compliant (system)

| Arrangement | Very low income (less than £15,600) | Low income (£15,600 -£26,000) | High income (Above £26,000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arrangement in place at 12 months | 76% | 85% | 86% |

| No arrangement in place at 12 months | 24% | 15% | 14% |

| Unweighted base | 130 | 177 | 191 |

Enforcement

| Income | Very low income (less than £15,600) | Low income (£15,600 - £26,000) | High income (Above £26,000) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arrangement in place at 12 months | 73% | 75% | 70% |

| No arrangement in place at 12 months | 27% | 25% | 30% |

| Unweighted base | 109 | 176 | 168 |

Those who did not have a new arrangement in place after 12 months were also significantly more likely:

- To have at least three children: 25% of Receiving Parents in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment with at least three children had no arrangement as did 32% in the ‘enforcement’ segment.

- To be cases where the Paying Parent never had any contact with the child / children: 30% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 40% of ‘enforcement’ cases where this was the situation had no arrangement.

The types of child maintenance arrangements at three and twelve months

The different types of child maintenance arrangements that parents could make were:

- Direct Pay and Collect and Pay arrangements made through the CMS;

- Arrangements made through the courts; and

- Family-based arrangements (FBA).

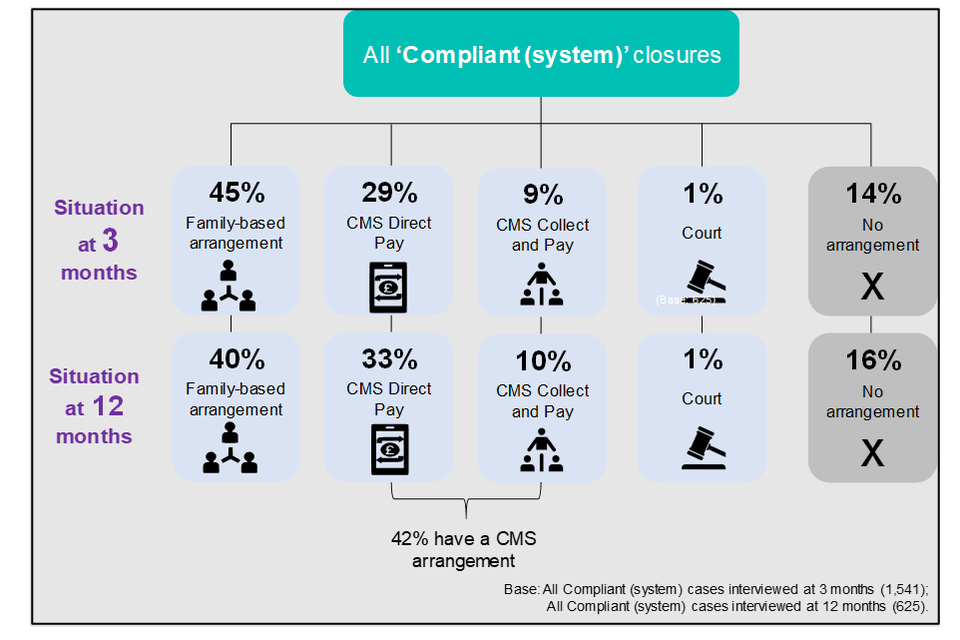

Figure 2.1 shows the types of arrangement that Receiving Parents in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment had in place at the 3 and 12 month points.

Figure 2.1 Type of child maintenance arrangement in place 3 and 12 months after case closure for ‘compliant (system)’ cases

FBAs were the most common type of new arrangement to be in place for Receiving Parents in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment at both points although the proportion with an FBA decreased between the three and 12 month points. When Direct Pay and Collect and Pay users are taken together, the proportion using a CMS service was similar to the proportion using an FBA (42% using a CMS service at the 12 month point compared with 40% using an FBA), 16% had no arrangement at the 12 month point. Figure 2.2 shows the same information for the ‘enforcement’ segment

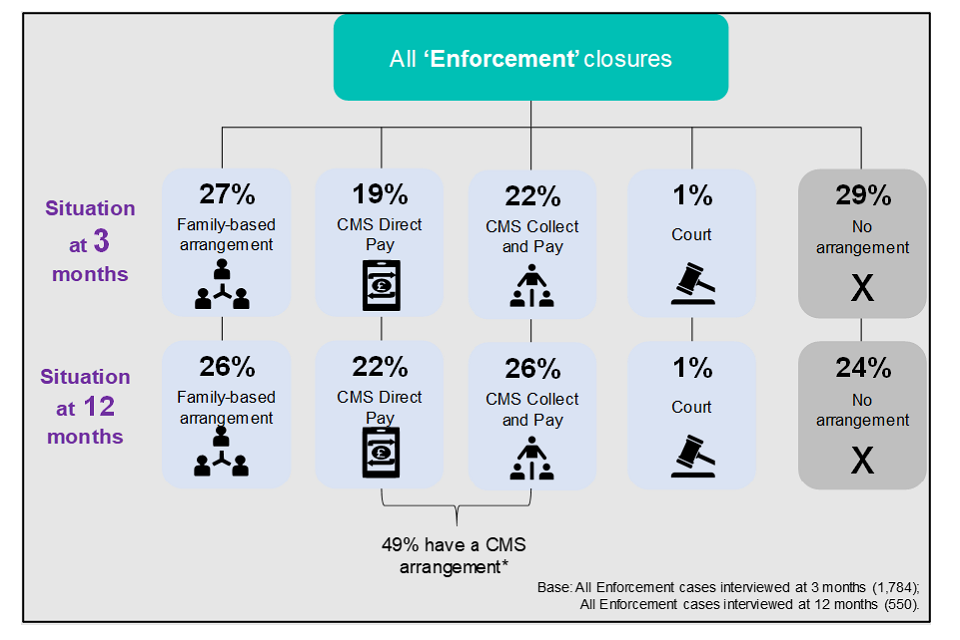

Figure 2.2 Type of child maintenance arrangement in place 3 and 12 months after case closure for ‘enforcement’ cases

Receiving Parents in the ‘enforcement’ segment were notably less likely to have an FBA in place, than those in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment’ at both the three and 12 month points (26% compared with 40% at the 12 month point). They were also less likely to have a Direct Pay arrangement (22% compared with 33% at the 12 month point). Receiving parents in the ‘enforcement’ segment were more likely to have a CMS Collect and Pay in place (26% compared with 10% at the 12 month point).

The reasons for a higher proportion of cases with CMS arrangements in this segment may be related to the ‘compliance opportunity’ offered to those in the ‘enforcement’ segment. The DWP legislated to ensure that where a case came into CMS that had previously been paid by an enforced method a 50/50 enforced/voluntary payment regime was used for a short period to enable Paying Parents to demonstrate that they could be compliant and entitled to use Direct Pay.

The movement between different arrangements at 3 and 12 months

As Tables 2.2 and 2.3 show, most families had the same type of arrangement in place at 12 months as at three months. Notably, almost nine in ten (88% of ‘enforcement’ and 87% of ‘compliant (segment)’ cases had a CMS arrangement in place at both and three months. Similarly, 78% of those in both segments who had an FBA in place at three months still had an FBA in place at 12 months.

However, there was some movement between types of arrangements. Of those who had an FBA in place at three months, 14% of those in each segment had moved to a CMS arrangement by the 12 month point. Similarly, of those who had a CMS arrangement set up at three months, 9% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 5% of ‘enforcement’ cases had moved to an FBA by 12 months. 15% of ‘compliant (system)’ and 25% of ‘enforcement’ cases who had no arrangement at three months had a CMS arrangement by the 12 month point.

A small proportion of those who had an FBA set up at three months had no arrangement at all by 12 months (7% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 6% of ‘enforcement’) and a similarly small proportion of those who had a CMS arrangement in place at three months had no arrangement by 12 months (3% for ‘compliant (system)’ and 7% for ‘enforcement’ cases). The overall picture remains relatively static however because similar numbers of those who had no arrangements in place at three months had set up an FBA or a CMS arrangement by 12 months.

Table 2.2 Type of arrangement at 12 months by type of arrangement at three months – compliant (system) cases

Type of arrangement in place at three months (compliant (system) cases)

| Type of arrangement in place at 12 months | A family-based arrangement % | A CMS arrangement % | No arrangement % |

|---|---|---|---|

| A family-based arrangement | 78% | 9% | 11% |

| A CMS arrangement | 14% | 87% | 15% |

| A court-based arrangement | 1% | 1% | 3% |

| No arrangement | 7% | 3% | 72% |

| Unweighted base | 260 | 267 | 93 |

Table 2.3 Type of arrangement at 12 months by type of arrangement at three months – enforcement cases

Type of arrangement in place at three months (enforcement cases)

| Type of arrangement in place at 12 months | A family-based arrangement % | A CMS arrangement % | No arrangement % |

|---|---|---|---|

| A family-based arrangement | 78% | 5% | 5% |

| A CMS arrangement | 14% | 88% | 25% |

| A court-based arrangement | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| No arrangement | 6% | 7% | 70% |

| Unweighted base | 157 | 277 | 151 |

The types of Family Based Arrangements in place

Receiving Parents with an FBA in place at three months were asked about the nature of their arrangement. They were prompted with the options shown in Figure 2.3 to help deduce:

- Whether the arrangements were financial in nature (i.e. the Paying Parent gave regular payments at a set level, potentially coupled with other types of financial and non-financial support), or

- Whether the support provided through the FBA was not predominantly financial in nature (i.e. the arrangement was more ad hoc and could include financial elements – such as providing food and clothes – but regular payments at a set level were not made).

As shown in Figure 2.3, the vast majority of Receiving Parents with an FBA in place at the 3 month point had a financial arrangement: 90% of those in the ‘enforcement’ segment and 93% in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment.

Financial FBAs were slightly less common among Receiving Parents with a household income of less than £15,600 (89% of those in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment and 82% of those in the ‘enforcement’ system) compared with those with a household income over £15,600 (94% in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment and 92% in the ‘enforcement’ segment).

Figure 2.3 Characteristics of family-based arrangements in place three months after case closure

| Family-based arrangement | Compliant (system) % | Enforcement % |

|---|---|---|

| Provide regular set amount of money | 93% | 90% |

| Share looking after child | 50% | 40% |

| Pay for agreed things (after school clubs, holidays, pocket money etc) | 20% | 17% |

| Non-financial contributions (food, clothes, help with childcare) | 20% | 16% |

| Other non-financial support | 5% | 4% |

| Other financial support | 1% | 1% |

Base: Those with a family-based arrangement: compliant (system) segment (808); enforcement segment (406)

Note that parents could give multiple responses at this question.

Similarly, the vast majority of the FBAs that were in place 12 months following case closure were financial in nature. This was the case for both segments (92% for ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 93% for ‘enforcement’ cases).

The main reasons for sustained arrangements

When interviewed at the 12 month point, all those who had had an arrangement in place for at least 6 months were asked about the reasons why they felt they had been able to sustain the arrangement.

As shown in Tables 2.4 and 2.5, among those with CMS arrangements in both segments, the effectiveness of the CMS enforcing payment was by far the most common main reason cited by Receiving Parents for their arrangement being sustained. A range of key reasons were given for FBAs being sustained with the most commonly mentioned in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment being that the Paying Parent was happy with the amount they paid and the most common in the ‘enforcement’ segment being that the Paying Parent could afford to pay.

Table 2.4 Main reason arrangement has sustained by agreement type: Compliant (system) segment

Type of arrangement in place at 12 months

| Compliant (system) | Family Based Arrangement | CMS Arrangement (Direct Pay or Collect and Pay)* |

|---|---|---|

| CMS forces PP to pay | 0% | 61% |

| PP can afford to pay | 12% | 13% |

| Putting time in to make it work | 13% | 7% |

| PP happy with amount they pay | 18% | 6% |

| PP and children have regular contact | 14% | 7% |

| PP does not want to use Collect and Pay | 11% | 5% |

| RP and PP have good relationship | 11% | 3% |

| RP and PP can talk about money | 7% | 3% |

| RP and PP have regular contact | 4% | 1% |

| Ordered by Court/CMS | 1% | 4% |

| Unweighted base | 89 | 166 |

*Responses for Direct Pay and Collect and Pay cases have been combined because of a low base size for Collect and Pay cases.

Table 2.5 Main reason arrangement has sustained by agreement type: Enforcement segment

Type of arrangement in place at 12 months

| Enforcement | Family Based Arrangement | CMS Direct Pay | CMS Collect and Pay |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMS forces PP to pay | 2% | 53% | 63% |

| PP can afford to pay | 29% | 9% | 13% |

| Putting time in to make it work | 8% | 11% | 14% |

| PP happy with amount they pay | 23% | 7% | 2% |

| PP and children have regular contact | 11% | 4% | 1% |

| PP does not want to use Collect and Pay | 13% | 8% | 0% |

| RP and PP have good relationship | 10% | 1% | 0% |

| RP and PP can talk about money | 8% | 4% | 0% |

| RP and PP have regular contact | 9% | 1% | 1% |

| Ordered by Court/CMS | 3% | 2% | 1% |

| Unweighted base | 62 | 68 | 79 |

3. Deciding new child maintenance arrangements

Chapter overview

This chapter explores how decisions about what type of arrangement to set up were made between the Receiving Parent and Paying Parent, and what influenced these decisions, as well as exploring views on the process of CSA case closure. The chapter explores:

- Who made the decision and satisfaction with the decision;

- Paying Parents’ experiences of the CSA case closure;

- Decisions to have a CMS arrangement;

- Decisions to have an FBA;

- Reasons for not attempting, or attempting and failing, to set up an arrangement.

Key findings:

- Receiving Parents typically had a more active role in deciding on the type of arrangement to be set up, especially if it was a CMS arrangement.

- The most common reasons to have a CMS arrangement over an FBA was because that was considered the best way to ensure that maintenance was getting paid. Paying Parents said they had Direct Pay arrangements instead of FBAs due to lack of contact or a difficult relationship with the Receiving Parent.

- Direct Pay arrangements were chosen over Collect and Pay to avoid paying charges, because Receiving Parents thought it was best for their situation or because they believed that CMS had said that they must use Direct Pay (this was more common in ‘enforcement’ cases)’.

- The most common reason for using Collect and Pay rather than Direct Pay was, because the Paying Parent had a record of not paying. Paying Parents typically had little involvement with the setting up of a Collect and Pay arrangement.

- Receiving Parents most commonly opted for FBAs over Direct Pay because they felt they were easier to set up and administer or because they had a good relationship with the Paying Parent. Paying parents valued being able to bypass the CMS, keeping control of their affairs to some degree, to avoid the stigma of having to use the CMS and to avoid fees.

- In cases where no arrangement had been set up, this was primarily due to problems with the Paying Parent paying; this was the main reason given by Receiving Parents for not attempting to set up a new arrangement and also the main reason why arrangements had failed.

Who decided on new arrangements

The decision-maker for the type of arrangement

Receiving Parents typically had a more active role in deciding on the new type of maintenance arrangement than Paying Parents. Among ‘compliant (system)’ cases, 45% of Receiving Parents made the decision on the type of new arrangement themselves, 16% said it was made mainly by the Paying Parent and 33% stated that they made the decision together. Among ‘enforcement’ cases it was more common for the Receiving Parent to make the decision mainly themselves (58%) and less common for the decision to be made together (22%).

The Receiving Parent was more likely to have led the decision to have a CMS arrangement compared to other types of arrangement (77% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases with a CMS arrangement and 81% of ‘enforcement’ cases). Further, the Receiving Parent was more likely to have led the decision in cases where a Collect and Pay arrangement had been set up than a Direct Pay arrangement (‘compliant (system)’ cases: 74% for Direct Pay and 89% for Collect and Pay; ‘enforcement’ cases: 72% for Direct Pay and 89% for Collect and Pay).

FBAs were more likely to have involvement from the Paying Parent; they led the decision in 23% of FBAs in the ‘compliant (system)’ segment and 22% in the ‘enforcement’ segment, and the decision was made by both parents together in 55% of FBAs among ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 52% of FBAs in ‘enforcement’ cases.

The satisfaction levels of Receiving Parents with decisions made (in part) by Paying Parents

In arrangements where the decision was predominantly made by the Paying Parent, jointly by both parents, or was made by the CMS, Receiving Parents’ satisfaction with the arrangements was mixed: overall half (51% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 50% of ‘enforcement’ cases) reported they were happy with the decision, and four in ten (40% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 41% of ‘enforcement’ cases) that they were unhappy.

In cases where the Receiving Parent did not solely make the decision on the type of arrangement to put in place, they were most likely to report that they were happy when FBAs had been set up (54% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 58% of ‘enforcement’ cases) and least likely to be happy with CMS arrangements (46% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 44% of ‘enforcement’ cases) and with Direct Pay arrangements in particular (45% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 41% of ‘enforcement’ cases).

Paying Parents’ experiences of CSA case closure

Levels of communication of case closure and awareness of next steps

Paying Parents typically came to learn that their CSA arrangement was being closed via a postal letter from the CSA. Of those who did not learn through a letter, most became aware through a telephone call with the CSA, often when contacting the CSA for other reasons. Paying Parents’ perceptions of the communication they received about the closure of their CSA case, and the next steps to take, were mixed.

Those who reported that the communication from the CMS was good tended to report that the letter they received clearly explained that their CSA case was closing, their options going forward and the associated charges.

‘It was easy to follow. It said ‘as of this date you have no account and you’ll need to set up another one’. It was all just self-explanatory and easy to read.’ (Paying Parent, aged 40-49, FBA)

‘The process was really simple. I got the letter through and it explained most of the things; what choices I had, whether I paid through the CMS and be charged, or go through them to get my ex’s account details and if she was happy then set up a standing order, and you have to pay a £20 fee. That’s what we did; it was really compact.’ (Paying Parent, aged 30-39, Direct Pay)

Others who were positive about the communication from the CSA mentioned that, after initially receiving a letter, they were able to follow this up with a phone call with an advisor, who clearly explained the situation and helped the Paying Parent understand what they would have to do next.

‘I got a really good contact at the CMS who explained everything to me, what was going to happen and how it was all going to change.’ (Paying Parent, aged 40-49, Collect and Pay)

While many were positive about the letter they received from the CSA, others felt that it did not clearly set out the situation, particularly how they should go about setting up a new arrangement. A few were unsure whether to wait for further instruction or to be proactive in setting up a new arrangement. Some felt that they would have liked to have been provided with a bit more background information about the CMS (since they had not seen any media coverage of the new agency).

‘Maybe some information regarding the CMS for a start, they could have maybe explained that this is our new service, this is the calculation, we’re working out the child maintenance you might be expected to pay, just a wee bit more advice on how to go about things. Instead it was just ‘this is closing – you must now make an arrangement with the CMS’ full stop.’ (Paying Parent, aged 30-39, Direct Pay)

Some would have preferred to have received a phone call from the CSA which explained their situation, feeling that receiving the information verbally would have been more helpful.

‘It might have been nice to have a phone call; contact over the phone to go into a bit more depth about what was happening’. (Paying Parent, aged 40-49, Direct Pay)

Experiences of the administration of case closure

Paying Parents’ views on the administration of their case closure were also mixed. The majority were positive about it, typically having had a straightforward experience setting up a new arrangement, while the minority who were critical raised the following issues:

Issues with final CSA payment

A couple of Paying Parents drew attention to issues they had with their final payment to the CSA and therefore felt that clearer instructions around this would have been helpful. One parent reported having to pay twice in the final month of their CSA case; first to the CSA in arrears and second to the CMS in advance, which left them in a difficult financial situation. Another, who telephoned the CSA after receiving the letter to clarify the terms of the final payment, was told that they would not need to do anything and that the case would be passed over to the CMS and they would receive a phone call. They reported that they did not receive this call, and this led to them getting into arrears.

‘I had the letter and that kind of explained that CSA was closing down and CMS was starting up and I had to make arrangements with them, but I still had to pay what I owed up to the point of closure so I had to pay twice in the final month – first to the CSA in arrears and second to the CMS in advance, which left me in a difficult situation.’ (Paying Parent, aged 40-49, Direct Pay)

Complicated process

A minority of Paying Parents felt the process was somewhat complicated, for different reasons. A few queried why they could not simply set up the same arrangement they had previously with one phone call. One was frustrated that the Receiving Parent had to confirm the type of arrangement, which led to the process being protracted.

There was also some frustration amongst Paying Parents over the time gap between the notification of the closure of their CSA arrangement and their ability to set up a CMS arrangement. One parent contacted the CMS using details on the letter they received about their CSA case closing but was informed that they could not yet set up a new arrangement.

‘I had to have the ex call them, but even after that they still needed confirmation…They didn’t believe me.’

(Paying Parent, aged 30-39, FBA)

Contacting the CSA or CMS

A few who contacted the CSA or CMS by telephone for clarification about their situation and what needed to be done next found the process frustrating, for various reasons. One found the process to follow before being able to talk to an advisor long-winded (e.g. answering security questions) while others were frustrated once they were through to an advisor, either because of a CSA advisor’s perceived lack of knowledge, or because they were unable to talk to the same advisor on each contact.

Deciding to have a family-based arrangement

The main reasons for choosing FBA over Direct Pay

Those who had an FBA in place were all asked the main reason for having this arrangement instead of a Direct Pay arrangement. As shown in Figure 3.1, most commonly Receiving Parents chose to have an FBA because they thought it was easier to make than a Direct Pay arrangement (23% of ‘enforcement’ cases and 25% of ‘compliant (system)’). Another sizeable group chose to make an FBA because of the nature of their relationship with the paying parent (‘Good relationship with the paying parent’ or ‘Can talk about money with the paying parent’). One of these 2 reasons were cited by 17% of ‘enforcement’ cases and 20% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases.

Figure 3.1 Main reasons why Receiving Parents had an FBA instead of a Direct Pay arrangement

| Reasons | Compliant (system) % | Enforcement % |

|---|---|---|

| Easier to make a FBA | 25% | 23% |

| Good relationship with the paying parent | 13% | 10% |

| Can talk about money with the paying parent | 7% | 7% |

| Poor previous experience with the CSA | 6% | 9% |

| Didn’t know about the CMS Direct Pay option | 6% | 7% |

| Didn’t want to pay the CMS charges | 4% | 7% |

| It is more flexible than using the CMS | 5% | 5% |

| The paying parent would not agree to using the CMS | 5% | 2% |

| You thought the paying parent would be more likely to pay if no one else was involved | 4% | 3% |

| Don’t know | 30% | 29% |

Base: Those with a FBA: compliant (system) segment (808); enforcement segment (396). Other reasons mentioned by <5% not shown.

Note: Receiving parents were first asked for all the reasons (prompted), then asked to select the single main reason. Responses shown here sum >100% due to some parents being unable to select a single main reason.

Other factors that were a main reason for a few families were:

- Poor previous experience with the CSA: ‘enforcement’ cases were more likely than ‘compliant (system)’ cases to cite this as the main reason (9% compared to 6%).

- The Receiving Parent did not know about the CMS Direct Pay option (7% for ‘enforcement’ cases and 6% for ‘compliant (system)’ cases).

- The Receiving Parent thought it was more flexible than the CMS (5% for both segments).

- Neither parent wanted to pay the CMS charges (4% for the ‘compliant [system]’ cases, 7% for the ‘enforcement’ cases).

When Receiving Parents who had an FBA instead of a Direct Pay arrangement after three months were asked to cite all reasons for having this arrangement, almost one quarter (23%) reported that not wanting to pay the charges for using the CMS was a factor. However, when asked for the main reason behind their decision to choose an FBA rather than Direct Pay, only a small minority (4%) for the ‘compliant [system]’ cases, 7% for the ‘enforcement’ cases) said it was because of the CMS charges.

In the qualitative interviews, the charges levied by the CMS were cited as a contributing factor in setting up an FBA by a couple of Paying Parents. These respondents mentioned that this was so that they would not have to pay any money to the CMS.

‘If I don’t have to pay something, I don’t pay for it.’ (Paying Parent, aged 40-49, FBA)

Three in ten Receiving Parents (30% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 29% of ‘enforcement’ cases) did not know the most important reason, primarily because the decision was made by the Paying Parent.

Interviews with Paying Parents indicated that they were typically more in favour of having an FBA than a CMS arrangement. This supports the quantitative findings which showed that Paying Parents were more likely to have played a lead or joint role in the decision-making process in cases where an FBA had been set up, compared to when a CMS or a Court-Based arrangement had been set up.

Paying Parents often wanted to avoid involving the CMS in their arrangement, for a variety of reasons:

1. To avoid the bureaucracy or hassle of setting up an arrangement through the CMS when they could do so themselves, for example, through setting up a direct debit with their bank. Some reported that their FBA was quick and easy to set up.

‘Because we came to an amicable decision that’s what we both wanted for our daughter it was a lot more straightforward because there weren’t the letters, the agreements, the set fees and the dates.’ (Paying Parent, aged 40-49, FBA)

2. To avoid a perceived loss of control of their monetary affairs, with the CMS determining when and how much money was taken from them. A few were uncomfortable with the fact that their payments would change depending on monthly earnings or overtime. Additionally, they felt that an FBA meant they did not have to worry about delays with payments being processed (which some had previously experienced with their CSA arrangement).

‘It’s a lot better; at least I know on a day-to-day basis that this much is going to go out without any errors or delays. It was an absolute nightmare and things are a lot easier now.’ (Paying Parent, aged 40-49, FBA)

3. A few felt that there was a stigma attached to paying child maintenance through the CSA or CMS, perceiving that others thought it implied guilt or an unwillingness to pay maintenance, and therefore did not want their employers to be aware of this.

4. To avoid paying an application fee or having the CMS take a percentage of the maintenance. This was in reference to the £20 application fee for using the CMS, the 20% additional fee-paying parents pay and the 4% fee deducted from the receiving parents’ payment for the use of the Collect and Pay service; this charge does not exist for Direct Pay.

‘I was happy enough paying maintenance, but I don’t want to pay any extra unless I don’t have to, nobody does.’ (Paying Parent, aged 30-39, FBA)

More generally, those with an FBA often felt it was a suitable option for both parties and that it felt like a more ‘grown up’ option than being ordered to pay by the CMS; in some cases, having an FBA was a sign of an amicable relationship between the paying and Receiving Parent.

Deciding to have a CMS arrangement

The payer of the £20 application fee and its perceived affordability

When an arrangement is set up through the CMS a £20 application fee is payable by the parent who applies to the CMS (except in extenuating circumstances).

The Receiving Parent was far more likely than the Paying Parent to have paid the £20 application fee in cases where a CMS arrangement had been set up; the Receiving Parent paid in around six in ten instances (56% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 63% of ‘enforcement’ cases), while the Paying Parent paid in only a small minority (5% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 3% of ‘enforcement’ cases). In around one quarter of cases (27% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 26% of ‘enforcement’ cases), neither parent paid the fee, while around one in ten (12% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 8% of ‘enforcement’ cases) did not know who had paid.

In cases where the Receiving Parent paid the application fee, around two thirds (70% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 63% of ‘enforcement’ cases) found it easy to afford, while the remaining third (30% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 36% of ‘enforcement’ cases) found it difficult.

Receiving Parents with a lower household income were more likely to have found the £20 application fee difficult to afford than parents with a higher household income: Of those with an annual household income of less than £15,600, 46% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 46% of ‘enforcement’ cases found the fee difficult to afford, compared to only 16% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 12% of ‘enforcement’ cases with an income of £32,000 or more.

The main reasons why parents decided to use the CMS over making an FBA

Receiving Parents who had a CMS arrangement in place at the 3 month point were asked to give the single main reason why they had chosen to have a CMS arrangement instead of an FBA. They chose contributing factors initially from a list of coded options (including the option to specify a reason not on the list) and were then asked which of those factors was the main reason.

The most common reason behind deciding to have a CMS arrangement over an FBA was that the Receiving Parent felt that this was the best way to ensure they received maintenance from the Paying Parent. As Figure 3.2 shows, just over a third of Receiving Parents in both segments said that the main reason they chose a CMS arrangement was because the Paying Parent would not pay otherwise; and around a quarter because they thought the Paying Parent was more likely to pay if the CMS was involved.

Those with ‘compliant (system)’ cases were significantly more likely to say that the primary reason that they chose to have a CMS arrangement over an FBA was because they were not sure how much maintenance should be paid (9% compared to 4% of ‘enforcement’ cases), while ‘enforcement’ cases were significantly more likely to say the main reason was because they wanted an arrangement where the CMS collected the money from the Paying Parent and paid them directly (6% compared to 3%).

The 16% included in ‘Don’t know’ at this question include those who did not make the decision to use the CMS themselves i.e. the CMS or the Paying Parent made the decision.

Figure 3.2 Main reasons why Receiving Parents decided to have a CMS arrangement over an FBA

| Reasons | Compliant (system) % | Enforcement % |

|---|---|---|

| The paying parent won’t pay | 35% | 37% |

| The paying parent would be more likely to pay if the CMS were involved | 25% | 26% |

| Don’t want any contact with the paying parent | 13% | 13% |

| There was a domestic abuse issue | 9% | 9% |

| Don’t know how to contact the payiong parent | 4% | 6% |

| Have tried to make an FBA in the past and it hasn’t worked | 7% | 8% |

| It’s difficult to talk about money with the paying parent | 8% | 8% |

| Wasn’t sure how much maintenance should be paid | 9% | 4% |

| Don’t know | 17% | 15% |

Base: Those with a CMS arrangement: compliant (system) (700); enforcement segment (648).

Note: Receiving parents were first asked for all the reasons (prompted), then asked to select the single main reason. Responses shown here sum to >100% due to some parents being unable to select a single main reason.

Believing that the Paying Parent would not pay maintenance otherwise was more likely to be given as the main reason by parents who had a Collect and Pay arrangement than a Direct Pay arrangement (‘compliant (system)’ cases: 39% compared to 33%; ‘enforcement’ cases: 43% compared to 30%). Giving the main reason that they thought the Paying Parent would be more likely to pay if the CMS were involved was more common among those with a Direct Pay arrangement (‘compliant (system)’ cases: 27% compared to 20%; ‘enforcement’ cases: 30% compared to 21%).

Interviews with Paying Parents explored the reasons why they had a Direct Pay arrangement in place rather than an FBA. In keeping with the views of Receiving Parents outlined above, reasons cited by Paying Parents tended to indicate a difficult relationship or non-existent relationship between the paying and Receiving Parent and/or a desire on the part of the Receiving Parent to keep the CMS involved.

A few Paying Parents mentioned that the Receiving Parent wanted a Direct Pay arrangement so that they knew they would receive child maintenance payments on time and that they would get the correct amount due. In one case, the Receiving Parent wanted the CMS involved so that if the Paying Parent’s financial situation improved, this would be reflected in increased maintenance payments.

‘She just wants the comfort knowing that she always going to get that payment and if I was to get a new job with a higher salary then she would get a cut of that as well.’ (Paying Parent, aged 30-39, Direct Pay)

Often, Paying Parents stated that they would have preferred to have an FBA but the Receiving Parent, who had more influence on the decision, wanted to set up an arrangement with the CMS.

Generally qualitative findings indicated that communication and a level of trust between both parents were often needed in order for an FBA to be a viable maintenance option.

‘Lack of contact. If there wasn’t such a breakdown in communication, then yes but I think it’s worked out best for both parties in this instance’ (Paying Parent, aged 30-39, Direct Pay)

Another Paying Parent who cited lack of contact as a reason for having a Direct Pay arrangement reported that it was easier for both the Receiving and Paying Parent (than an FBA) as they were not on talking terms.

For a few, despite having some contact, the difficult relationship between the Paying and Receiving Parent precluded an FBA being set up because they felt it would not have been possible to agree on the way the FBA worked. For one of these parents, having a fee and expectations of the arrangement agreed by the CMS was easier than agreeing them themselves.

‘I think it’s having that agreed fee and having those expectations about what is and isn’t acceptable in terms of… what I can afford and what I can’t afford and allowing me to maintain that contact [with his child].’ (Paying Parent, aged 40-49, Direct Pay)

In qualitative interviews, Paying Parents with a Collect and Pay arrangement were asked why they had chosen that arrangement instead of an FBA. Generally they felt they had very little influence on the decision to set up a Collect and Pay arrangement, which was made by the Receiving Parent:

- For a few, the Paying Parent did not have any contact with the Receiving Parent, who made the decision on their own. One reported that they refused to have contact with the Receiving Parent, while for another a breakdown in communication after an initial agreement on an FBA led to a Collect and Pay arrangement being set up.

- A few, who had little or no contact with the Receiving Parent, were confident that the Receiving Parent would not have agreed to an arrangement that did not involve the CMS, despite not actually having had a conversation about it.

- One mentioned that the Collect and Pay arrangement, initiated by the Receiving Parent, had been set up because it mirrored the arrangement they had with the CSA.

Case example of a Collect and Pay arrangement being set up against the wishes of the Paying Parent.

The Paying and Receiving Parent had been separated for 12-13 years and the Paying Parent had little contact with either his ex-partner or his son.

The Paying and Receiving Parent do not have an amicable relationship, with the Receiving Parent considering him responsible for delayed payments from the CSA.

The Paying Parent wanted to agree a family-based arrangement as soon as he heard about the CSA being closed down so they could have a smooth arrangement – the Receiving Parent initially agreed. However, the Receiving Parent was subsequently uncommunicative, refusing to talk to the Paying Parent or send their bank details and the next communication the Paying Parent had from the CMS was that the arrangement would be Collect and Pay.

The Paying Parent is dissatisfied with the fees associated with Collect and Pay and frustrated that the decision to have this arrangement was out of his hands.

The main reasons for choosing Direct Pay instead of Collect and Pay

Receiving Parents with a Direct Pay arrangement were asked why they had this type of arrangement instead of a Collect and Pay arrangement. As shown by Figure 3.3 the most common factors given as the ‘main reason’ were:

- To avoid the Collect and Pay charges (22% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 17% of ‘enforcement’ cases).

- The parents thought a Direct Pay arrangement would work for them (22% of ‘compliant (system)’ cases and 17% of ‘enforcement’ cases).