SPI-M-O: Consensus view on the impact of mass school closures, 19 February 2020

Updated 13 May 2022

Introduction

1. At this stage the magnitude of the impact that school closures would have on a UK epidemic of COVID-19 is very uncertain. There are many uncertainties about the virus including, importantly, the role of children in transmission, and the severity of infections in children.

2. Most previous modelling of the impact of school closures has been in relation to pandemic influenza. In the 2009 influenza pandemic, the school summer holiday interrupted transmission to such an extent that the UK epidemic was split into 2 waves, with the second coming after their reopening in the Autumn.

3. For the purpose of this paper, we assumed that children have a role in transmission similar to that of influenza. The results below are very sensitive to this assumption. The smaller the role of children in transmission, the lower the impact of school closures.

4. In addition to this, the impact of school closures on COVID-19 is expected to be smaller than in 2009, because:

- the average time between symptom onset in primary and secondary cases (known as the serial interval) is longer than for influenza. As a result, schools would have to be closed for longer to have the same effect;

- the reproduction number in Wuhan in the early stage of the outbreak is higher than in 2009; and

- in 2009, some adults had pre-existing immunity, so a higher proportion of transmission took place within schools.

Modelling approaches

5. 3 new modelling works were produced to address this. Our approaches were broad: one full spatial individual-based model (IBM) exploring a range of scenarios, one individual-based model that considered also reactive closure strategies and varying infectivity profiles and one compartmental model exploring two different forms of age-structured mixing. The different modelling approaches gave results which were similar in some ways but differed in others.

6. From the different approaches taken, we know that there is sensitivity to assumptions about:

- the precise age-structure of mixing;

- the profile of individual infectiousness against time;

- compensatory mixing changes caused by school closure; and

- susceptibility and transmissibility of COVID-19 in children.

Commonalities in results

7. The effect in delaying the peak of the UK epidemic appears modest throughout a range of plausible parameters and approaches: no more than 3 weeks and possibly far less. The larger impacts are seen when closures take place early in a UK outbreak.

8. Any impact from school closures on the total number of cases is likely to be highly limited.

9. School closures may be able to extend the duration of a UK epidemic, reducing its peak incidence. Up to a certain point, longer school closures are likely to have more effective than shorter ones.

10. School closures can be used to reduce peak incidence, but the effect on total incidence (final size) is likely to be highly limited.

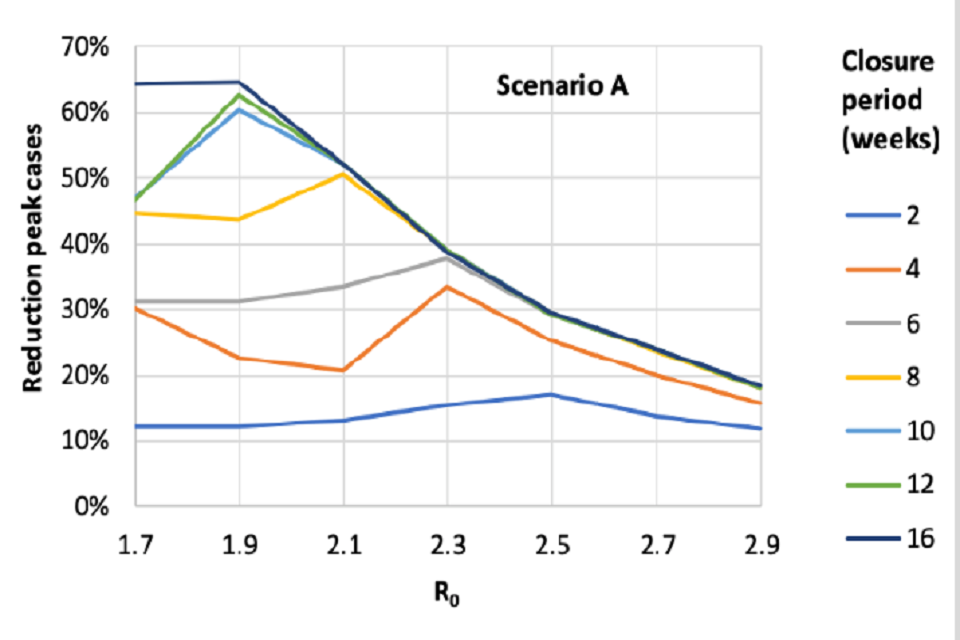

11. The effectiveness of school closures in reducing peak incidence is sensitive to the reproduction number R0 (see figure): the higher the R0, the less effective they would be.

Differences in results

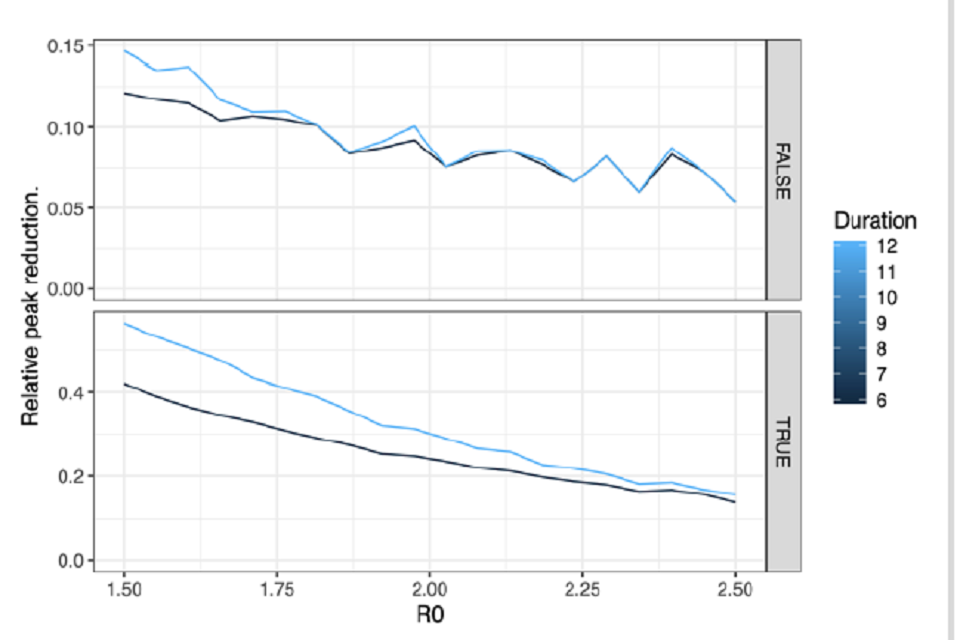

12. The key difference between our approaches so far is the predicted reduction in the peak size of the epidemic that school closures produce. The figure below shows the outputs for 2 approaches. For R0 around range 1.9 to 2.3 and school closures of 6 to 12 weeks: the IBMs suggests an effect of the order of 20% to 60% reduction, while the compartmental models suggest 7.5% to 30%.

Line chart showing the reduction in epidemic peak from one individual-based model is higher for longer school closures, and broadly for lower R0 (though not linearly). For R0 of 1.9-2.3 and 4-12 week closures, the peak reduction ranges from 30%-60%.

From an IBM under relatively optimistic assumptions.

[Children and adults equally susceptible to infection and likely to transmit. Closure of schools increases household contact rates by 25%, has no effect on other transmission.]

Line charts showing the relative reduction in epidemic peak from one compartmental model is higher for longer school closures, and for lower R0. For R0 of 1.9-2.3 and 6-12 week closures, it ranges from 7.5%-30% depending on assumptions for adult contacts.

For a compartmental under certain assumptions.

[Predicted reduction is much higher when scaling the adult contacts following Birrell et al. 2011 (bottom panel), than when using the raw polymod matrix (top panel).]

13. The reason for this difference is under continued discussion, but it may be particularly shaped by assumptions of how schools, households and the wider community are interconnected. More work is needed to understand this.

Timing of SC

14.The consensus view is that a long duration school closures (6 weeks or longer) are most effective if started as early as possible. They are less sensitive to timing that shorter school closures.

15. Shorter duration closures (say 2 to 4 weeks) may have a role to play. Their impact and optimal timing are less clear. This will depend on R0, and may lead to 2 peaks of incidence. There is some suggestion that the best time for a short closure may be just before the peak, but there is not consensus on this point. Identifying the peak during the epidemic would be very difficult.

16.Further consideration should go into using a short closure to extend an existing school holiday, but the impact of this will be highly dependent on the timing of a UK epidemic.

17. Developing the optimal triggers for school closures is intrinsically difficult, both because the impact of closures is highly dependent on its timing and because of the difficulty in predicting the timing of an epidemic peak.

Uncertainties

18. Not all parameters and assumptions have yet been cross calibrated between models.

19. Only national-scale closure policies have been compared so far.

20.The knock-on effects on how contact patterns will change with school closures of different lengths is a fundamental knowledge gap that cannot be determined by modelling.

21. The question selective school closures with specific year groups requires further consideration and discussion with the Department for Education. Any partial closure (primary compared to secondary, or everyone except GCSE cohorts and above) would be expected to have a smaller effect. Its magnitude has not this has not been explored; there would be even greater uncertainty in any such results than what is given here.

Other considerations

22. As well as the large economic and educational costs of school closures, including increased levels of workforce absence in the health and care system and elsewhere, school closures could have adverse consequences.

- As infections appear to be more severe in older people, putting children in the care of their grandparents may result in a higher number of severe cases.

- Once schools are reopened, the number of cases may increase again, with the overall attack rate not being reduced.

23. A rapid literature review has shown that whilst school closures do appear to reduce the number of contacts that children have outside the home, such contacts remain common. Were children to congregate in day-care settings during a UK COVID-19 epidemic, the impact of school closures would be lower. Past data are based on short duration closures. The impact of longer-term closures on patterns of behaviour are likely to be different and cannot be determined by modelling alone. Modelling results are very sensitive to these assumptions.

24. The Department for Education are working with SPI-M-O through DHSC to give modellers access to relevant data.

25. Detailed forecasts of the likely impact of school closures will be possible once there has been several weeks of sustained transmission of COVID-19 within the UK.