SPI-B: Areas of intervention (‘local lockdown’) measures to control outbreaks of COVID-19 during the national release phase, 30 July 2020

Updated 13 May 2022

SAGE commission to SPI-B: Areas of intervention (‘local lockdown’) measures to control outbreaks of COVID-19 during the national release phase.

Current experience in Leicester shows that during the coming phase of release from lockdown there may be a need to maintain or reintroduce stricter lockdown measures in specific geographic areas to contain and control local outbreaks, while allowing the economy to restart in the rest of the country where it is safe to do so. This threatens the ‘we are all in it together’ spirit that has characterised public compliance to date and raises a prospect of perceived inequity between different communities.

- What are the adherence barriers to effective local lockdown measures?

- What can be learned from other countries that have adopted local area-based lockdown measures? To include examples where local lockdowns have been managed across regional or national borders.

- What are possible wider effects and unintended consequences of a local lockdown on the affected population, including trust in government, social stigmatisation, public disorder, and decreased travel and visits to area post-lockdown? In areas with clusters of vulnerable or marginalised social groups, what steps are required to ensure that measures are equitable and not discriminatory?

- What specific measures might be taken to achieve public buy-in and compliance with such measures in the UK? To include form and timing of effective announcements and messaging.

Introduction

‘Local lockdowns’ are an important means of preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The British public were first exposed to the idea in the government’s recovery plan [footnote 1] published on 11 May 2020. A priority was to manage new outbreaks by detecting infection ‘hotspots’ at a more localised level and tackling these with targeted measures. A ‘local lockdown’ was presented as a mitigation measure integral to the release of the ‘national lockdown’ – the aim being to ‘control the spread of the coronavirus pandemic by containing it within a particular area and so avoid re-imposing social distancing restrictions across the whole of the country’. [footnote 1]

The term ‘local lockdown’ is problematic. A recent interview study undertaken by Professor Laura Bear and colleagues at LSE found that residents in Leicester reported feeling ashamed or punished as a result of the localised measures that were introduced. The terminology of ‘local lockdown,’ with its implications of punishment and separation from the rest of the country, was cited as contributing to this.

In practice, ‘lockdowns’ are implemented to channel significant support towards an affected community. The COVID-19 contain framework [footnote 2] does not use the phrase ‘local lockdown’ but instead refers to ‘areas of concern,’ ‘areas of enhanced support’ and ‘areas of intervention’. We use ‘local intervention’ in the rest of this paper and strongly recommend national government, PHE, the media and others cease using the term ‘local lockdown’.

Leicester was the first city to become an area of ‘national intervention’ on 29 June, 2020. Restrictions were re-introduced in the protected areas including school re-closures; closure of premises and businesses; and restrictions on movements, gatherings, and interactions between households. Various exceptions were made, such as for funerals, provision of voluntary or charitable services, and caring for vulnerable persons. The city was unable to return to normal trading along with the rest of the country as planned on 4 July. New powers for councils to decide upon the type of closures required for future interventions were announced on 17 July. It is likely that council leaders will consider similar options and combinations of options when increases in local transmission of COVID-19 need to be addressed in the future.

In this paper we address four questions set to us by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). We are unaware of an existing academic literature on situations directly analogous to a local intervention for COVID-19. Our report is therefore based on relevant theory, preliminary findings from research conducted in Leicester by a recent study conducted by LSE Anthropology study (see Annex A) and a review of existing reports provided by the International Comparisons Joint Unit (ICJU) based in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

Our recommendations draw on SPI-B guidance for co-production. [footnote 3] Underpinning our approach is an understanding that decisions and messaging around local interventions will be nationally led, but locally relevant.

Question 1: What are the adherence barriers to effective local ‘lockdown’ measures?

The imposition of local restrictions may result in communities being asked to adhere to a raft of measures. These include enhanced communication about social distancing and hand hygiene and additional targeted testing (which apply when an ‘area of concern’ status is reached), and widespread testing, local restrictions and engagement with high-risk groups and sectors (‘area of enhanced support’ status). Communities living in designated areas of intervention may also experience enhanced inspection of businesses, closure of certain businesses, schools, venues and outdoor events, increased levels of working from home, movement restrictions and enhanced measures for people who are shielding. [footnote 4]

SPI-B and others have previously discussed factors associated with adherence to such measures and ways to improve adherence. [footnote 5] [^6] [footnote 7] In brief, behaviour change is more likely if people have the capability, opportunity and motivation to engage in the recommended behaviours and where measures are seen as legitimate [footnote 8]. An area subject to intervention may find that measures are sub-optimally adhered to. This is not a given, but the following factors increase the risk of lower adherence.

Capability

Knowledge and understanding of what behaviours are required may be impeded if mixed messaging exists between national messages relating to easing and local messages relating to new restrictions.

Opportunity

During the initial stages of the pandemic, a raft of support measures was provided in the UK that enabled people to adhere to ‘stay at home’ guidance. This included, among other things, the furlough scheme, grants to the self-employed, support from the NHS volunteer service, and dedicated hours in supermarkets for NHS workers or those aged over 70. Grassroots support networks also appeared in many local areas to provide support. Access to support was essential for many people and reduced the everyday challenges caused by the pandemic. [footnote 9] Reintroducing strict public health measures in the absence of a wide-ranging package of support measures may exacerbate pre-existing racial and other inequalities, making it impossible for some people to adhere to them.

Motivation

Motivation to adhere to new measures may be increased if a local resurgence of the disease increases fear or worry. [footnote 21] This may be particularly true in those sections of the population that feel most at risk (for example older adults, BAME groups or those who are clinically vulnerable). However, the relationship between perceived risk and vulnerable group status can be complex. Communication with these groups requires careful consideration. [footnote 12]

Residents may question why, if measures apparently did not work the first time, they are being imposed again. It is important for communicators to acknowledge the change in advice, identify the evidence and rationale for implementing these changes, identify the potential impact of the new advice on daily life, and provide regular updates. Provision of information with clear instructions about what to do, what not to do, and what to expect will reduce uncertainty and increase the likelihood of compliance. [footnote 13]

A sense of fatalism or low self-efficacy may also take hold if expected progress is halted or reversed, particularly if other areas of the country continue to enjoy the freedoms associated with low incidence.

Finally, there is a risk that it may be harder to evoke a sense of collective identity when local, rather than national, restrictions are imposed.

Legitimacy

If restrictions arising from a local intervention are viewed as illegitimate, this is likely to reduce adherence to public health measures and increase tension. Legitimacy is likely to be impacted if the intervention is viewed as:

- arbitrary, with no valid justification being apparent for the nature or scale of the intervention, or the population affected

- incompetent, reflecting an inability of national or local government to deal with the public health threat in a more timely manner

- inequitable, adversely affecting specific groups of people in an unjust manner or without mitigation being in place

- ineffective, and perceived by the community as having a limited likelihood of success

A particular issue for any area of intervention is likely to be the sudden change in restrictions at the boundary. Particularly for those who live either side of a boundary line, or who work or shop on different sides of it, the apparent arbitrariness of which rules apply where is likely to undermine the importance of the rules.

Question 2: What can be learned from other countries that have adopted local area-based lockdown measures? To include examples where local lockdowns have been managed across regional or national borders.

The imposition of interventions in specific areas are frequently used as part of a ‘cluster-detection’ approach to infection control. A transmission cluster (‘super-spreading event’) can be defined as 5 or more secondary infections from a single index case. In Japan, although a cluster is defined as 5 linked cases, an investigation is triggered when 2 or more cases are found to have been in close contact in the last 14 days in a setting known to be associated with clusters (for example, bars, music events, gyms).

Most comparators have incorporated some form of cluster-suppression into their responses to COVID-19. Some have done so since the outset and prevented widespread community transmission (such as Japan, South Korea). Others have adopted or readopted a cluster-based approach where community transmission is still present (such as Germany, Spain, Italy).

Comparator countries use testing in a variety of ways to detect ‘incident clusters’ early and enable faster responses. Early identification is assumed to be critical to effective suppression of clusters. If a possible cluster is detected, responses are rapid, making use of location-based testing and backward tracing as well as targeted interventions to prevent onward transmission.

Examples of localised interventions in response to a cluster detection include:

Australia: a large (over 100) outbreak at a hospital in Tasmania led to the closure of 2 sites, the quarantining of 1,300 staff and their families (3,000 to 4,000), and local restrictions placed on the town, with police deployed to ensure compliance. [footnote 14]

Singapore: identified a cluster linked to roaming McDonald’s staff who worked at several branches across the city, led to the closure of the company in Singapore for several weeks. [footnote 15]

South Korea: A church was asked to provide authorities with the congregation registration to track all members across the country, who were required to quarantine themselves for a 14-day period. A localised intervention was implemented which reduced movement by 80% [footnote 16].

Italy: In the municipality of Vo’ when the first COVID-19 linked death occurred on 21 February, national and regional authorities enforced the closure of all public services and commercial activities. A ban on population movement was imposed until 8 March 2020, following a second round of testing. [footnote 17]

It is important that measures are implemented at the appropriate level to avoid accusations of disproportionality. In July, a German court ended a localised intervention imposed to tackle an outbreak at a meat packing facility saying that the measures were disproportionate and the authorities should have replaced it with more focused measures. In Australia private citizens have launched legal actions against the state restrictions of Queensland and Western Australia, on the grounds that they are economically damaging and disproportionate to the threat. Any broad-brush COVID-19 suppression action could invite similar challenges which will promulgate the need for adopting more such interventions.

Suppression measures are typically implemented at a local level. National resources are used in the case of large outbreaks, such as the current outbreak in the Australian state of Victoria where borders have been closed and the military have been brought in (see Annex C for details).

The context of a specific country, and particularly the relative levels of trust in national and regional authorities, may impact the effectiveness of the response and whether it should be driven at the national or regional level. (see Annexes B and D). Whilst many Asian countries which are considered to have been effective at having controlled initial infections through national agencies - such as South Korea and Japan - others have effectively responded primarily at a regional or state level (such as Germany and Australia).

Some limited evidence suggests that the effectiveness of local restriction measures is related to how familiar a country is at implementing different regional measures and crisis response. For example, there are high levels of regional autonomy across many policy issues in both Australia and Germany. Anecdotal evidence suggests that recent examples of crises (Australian wildfires in January 2020, German refugee crisis in 2015) helped both to learn lessons that would prove useful for the management of the pandemic, such as coordination across regions.

Question 3: What are possible wider effects and unintended consequences of a national intervention on the affected population, including trust in government, social stigmatisation, public disorder, and decreased travel and visits to area post-lockdown? In areas with clusters of vulnerable or marginalised social groups, what steps are required to ensure that measures are equitable and not discriminatory?

The effect of re-introduced restrictions is likely to be different according to area, group and the specific individual. An intervention might enhance local community relations as those affected may have a more intense feeling of ‘being in it together,’ particularly if this sense of solidarity is actively promoted. It is also possible that background levels of social capital may buffer communities against negative impacts of the reimposition of local restrictions. [footnote 18]

However, it is more likely that the wider effects of interventions at the local level will be experienced negatively and be differentially experienced across the local demographic groups. There could be a number of unintended social, economic and financial consequences. These may be exacerbated if spikes are most likely to occur in deprived areas.

A divided nation: One potential consequence is the creation of a sense of separation and isolation from the rest of the nation so that instead of feeling cared for, those living in the protected area feel targeted, stigmatised and shamed. Such feelings can damage trust in central and local government and undermine adherence to wider measures introduced to tackle COVID-19. This lack of adherence may be underpinned by feelings of fear, unfairness, frustration or anger. Fear can also lead to poor decision-making, inappropriate behaviours, stigmatisation of certain populations and undermining the social cohesion [footnote 19]. Lack of trust can also result in an ‘infodemic’, [footnote 20] increased anxiety, spontaneous precautionary behaviours, and refusal to adopt recommended protective health behaviours.

Long term social stigmatisation and racial tensions: There is the danger of a cycle of local interventions in certain parts of the country as individuals in BAME and socio-economically disadvantaged groups susceptible to coronavirus find themselves under re-introduced local restrictions. These communities may lack the resources to have restrictions lifted due to structural discrimination which keeps them locked into economic sectors from which there is no potential for furlough and in crowded accommodation in which social distancing is impossible. Social stigmatisation will trigger discrimination, and long-term stigmatisation is likely to increase racial discrimination to the detriment of society as a whole. This situation may also be exploited by the extreme right wing.

Social unrest: A lack of clarity as to why restrictions were introduced has the potential to result in perceptions of inconsistency in the application of national interventions: trust in government is undermined when 2 areas present the same epidemiological evidence yet only one is subjected to the re-introduction of restrictions. Should the re-introduction of restrictions be perceived as always mapping onto BAME communities, this will result in destabilisation of social cohesion across the country. Inconsistency of implementation could then trigger social unrest and public disorder resulting in confrontations with local enforcement agencies. [footnote 21]

A further key issue for policing and disorder will be regulating the boundaries of the locality. Some within will want to travel outside for work, family, friends, school, leisure and so on. Some ‘outside’ may need to travel ‘in’ for similar reasons.

Long-term economic decline: There will inevitably be financial consequences. In Leicester, schools and businesses will have invested time and money to prepare to re-open on 4 July. This expenditure without income will impact local business and also local government finances, with reduced takings from use of services and facilities, taxes and local rates meaning less money to spend on services. An area identified as a COVID-19 ‘hotspot’ may become known as a place to avoid for fear of contracting COVID-19, reduction in travel to and through that area will further depress local finances, through reduced business takings and local taxation, resulting in higher reliance on funds from central government. Intention to avoid travelling through or returning to a previously contaminated area has been noted in prior studies. [footnote 22] If economic decline ensues, people will be less likely to visit the area; an area that people do not want to visit will become an area in which people do not want to live. If families no longer move there or current residents move away, the area will suffer long term economic damage.

Unless mitigation measures are put in place, there is therefore a risk of unintended, long-term consequences for community relations and social cohesion, levels of trust in government, compliance with measures as well as social stability and general public order.

Question 4: What specific measures might be taken to achieve public buy-in and compliance with such measures in the UK? To include form and timing of effective announcements and messaging.

In many ways, a local intervention is more complex – in practical and emotional terms - than the imposition of nationwide restrictions. While appreciating that it is an emergency measure, both entry into and exit from a localised intervention should be carefully managed, with particular attention paid to planning, subsequent action and communication.

To ensure as much consistency as possible, and that measures are equitable and not discriminatory, a national plan setting out comprehensive guidance should be developed which can be adapted by local leaders to meet local needs.

Measures to encourage public buy-in and adherence can be considered in 5 phases: National planning; Local planning; Preparation; During the local intervention; and After the local intervention. [footnote 23]

National planning

Communications

At a national level, communications should balance a focus on reducing transmission with the fact that local reimpositions are both likely and important. Messaging should contain a single narrative so that local and national messages are consistent.

Communications should be evidence-based, co-designed, and tested prior to release. It is important to carry out checks to see if they are understood, addressing key concerns, clarifying confusion, and more. Communication should not be released without follow-up assessment built into the process. This will help inform the development and delivery of communication needed in different areas for future (re)imposition of local restrictions.

Given growing evidence about the high rates of transmission in some BAME communities, it is particularly important that national communications start to take account of the principles of communicating to different socio-cultural groups and subgroups of gender and age within them as set out in a previous SPI-B report. [footnote 24]

The data used to determine the necessity of a local intervention should start to be presented regularly to the public in a clear and user-friendly way. A crucial part of transparency is explaining how the data analysed will translate into specific recommendations. We (and the public) appreciate that there will be nuances. However, the broad principles can and should be set out clearly and in advance. This will add legitimacy to any recommendations that need to be made and reduce any perceptions of unequal treatment.

The public should understand when, why and how measures will be reintroduced. The corrosive impact on a community of ‘infodemics,’ including ‘viral spread’ of misleading or inaccurate information and rumours, should not be underestimated. Rumours can instil fear, make people confused about what actions they should be taking, and erode trust in official messages. Already, lists have circulated in the media about the next towns that should ‘expect’ to be ‘locked down’. These are notable in that they list different towns. Going forward, it is essential that a single, authoritative source of data is given that people can turn to for transparent, easy to digest facts about the situation in their local area.

Legal clarity in decision-making is important. Regulations to enforce national intervention at the local level should now be published and clearly presented to the public before restrictions are re-imposed locally. Prior to the ‘lockdown’ in Leicester, the government had suggested that local restrictions would be handled by local leaders. However, the decision to impose a ‘lockdown’ in Leicester was taken by central government.

Re-framing ‘lockdown’ to focus on care and concern

Reframing should begin from a perspective of support, including additional resourcing necessary to support adherence to restrictions, for those communities experiencing increased incidence and outbreaks. Support for affected communities is also important because, infection is more likely in deprived communities who are more in need of support both to get tested and to self-isolate. This support can take a variety of forms beyond providing information: for example, making it easy to get tested, providing resources and other practical measures (such as accommodation) to make it possible for people to stay in and for local enterprises to stay closed.

The language of a ‘lockdown’ is inherently punitive. It is critical to start to reframe the issue by moving away from this punitive language as well as from an overall punitive approach. Areas experiencing the reintroduction of restrictions should not be subject to ‘blame’.

Reframing should emphasise care and concern and be set within the context of wider policies, covering Test, Trace, Isolate (TTI), health care, social support, schooling, defining boundaries, policing etc. These should be developed in advance to prevent stigmatization of already marginalized communities, which is important for motivation to adhere to local restrictions. In line with consistent evidence from procedural justice and community development, it is important that local emergency measures are not done to people, but with and for them.

Consideration of context is now also required where trust and moral authority are undermined to the extent that people no longer engage, for example with TTI: if release from local restrictions is only determined by TTI evidence, but this evidence cannot be collected due to lack of trust, this may result in a prolonged reintroduction of local restrictions.

Reframing to emphasise care and concern may strengthen the willingness of people to accept certain restrictions. In the absence of reframing, the danger is that a sense of local grievance maps onto to other dimensions of grievance (class, race, ethnicity and so forth) and provokes resentment.

Proportionality

To ensure that measures are equitable and not discriminatory in areas with clusters of marginalised social groups, action should start to be underpinned by the idea of proportionality. Proportionality emphasises the need that measures implemented are commensurate to meet the targeted end. It encourages interventions that are risk-based and balanced and is important for the continued legitimacy of local intervention measures. Proportionate interventions will make it easier to rebuild local confidence after the removal of restrictions. For example, it may be disproportionate for a national intervention at the local level to involve closure of schools given the increasing evidence that schools play a minor role in transmission.

In order to balance risk it might be asked: given the greater impact of closure of schools on the long-term education of children from low income homes, is the greater risk closure of schools or contracting COVID-19? Proportionality thus encourages the use of contextual local evidence - such as local data on multiple deprivation – as early as possible.

Proportionality suggests that the re-introduction of restrictions at the local level should not be envisioned in a broad brush, blanket way but start to be seen as a series of measures that are scale-able up and down, according to risk and available resource.

A useful example is provided by a study exploring radiation contamination: respondents requested maps containing zones of contamination linked to specific advice and behavioural recommendations for individuals living in each zone. A similar approach linking level of infection and protective behaviours could be adopted in areas of increasing infection rates [footnote 25]. This will require careful framing to avoid stigmatisation. For example, using number or colour ratings overlaid on a map rather than focusing on local or neighbourhood names. Research, co-production, co-design and careful stakeholder testing at the local level is needed to avoid the unintended consequences mentioned above in Question 3.

Envisioning this as a staircase – similar to the JBC approach - may be useful, with clear indicators and thresholds being identified to signal the need for specific protective health behaviours or restrictions to occur as the risk of infection increases. A similar approach can begin to be applied to the exit strategy with clear indicators and thresholds being identified to signal the ability to decrease restrictions and the freedom to engage in a different set of behaviours. Members of communities facing the possibility of national interventions at the local level should be able to engage with the staircase into and out of restrictions with ease.

Local planning for a local intervention

To ensure consistency, the national plan setting out comprehensive basic guidance should be the basis of local plans devised to meet local needs.

There is an obvious role in this for local councils and Directors of Public Health to develop local action plans that will sit alongside and complement JBC guidance. The Joint Biosecurity Centre (JBC), Public Health England (PHE), NHS bodies and directors of public health should work with councillors, MPs, administrators, healthcare, social care and mental health professionals, and police officers well in advance of potential spikes.

Going forward, development of a local plan must involve co-production with local communities or it will be at best inefficient, without due regard to the information that is locally relevant and necessary to reintroduce restrictions, and at worst unworkable and divisive. Consultation with community leaders and key stakeholders will be essential to develop a shared understanding and knowledge of the goals of any national interventions and why measures may be deemed necessary. This is essential preparatory work that should be undertaken early.

Co-production of plans may be a useful public health exercise in its own right, highlighting unexpected areas of risk that can then be tackled pre-emptively with appropriate resourcing. At the same time, co-production in planning for national intervention at the local level may lead to unintended consequences, such as increased fear. Focusing on preparation and planning rather than reactivity in co-production, and on generating buy-in and developing a clearer understanding of local community needs, may help to counteract these risks.

Planning needs to cover general issues including communications; TTI; NHS and social care capacity; support for business, schools and other organisations; and policing. Planning should also start to include the following considerations.

-

Social cohesion: thought should be given to the impact and perception of locally re-introduced restrictions on the BAME population. In line with the public sector equality duty (PSED) in the Equality Act 2010, work would need to be done to prevent the stigmatisation of people from BAME communities and other protected groups. Bearing in mind local trends in right-wing radicalism, this may require engagement in particular with white populations, counter-acting adverse media reporting.

-

Generational differences: the impact of re-introduced restrictions on younger and older people needs to be carefully considered.

-

Individual needs: In addition, disabilities that might impede mobility and access, sensory disabilities such as autism that might heighten a distress reaction and or impede response to instruction, and cognitive impairments that might impede understanding a situation or instructions should be considered. Additionally, second language considerations for students and families must also be addressed.

Preparation for a local intervention

Ongoing public buy-in and compliance is best secured by the institution of a predictable procedure of what to expect and by perceptions that the measures implemented are in their best interests. Preparation is therefore critical.

Simply alerting communities to changes in their incidence rate is not enough. There is little point highlighting levels of risk to people, unless they are accompanied by advice on what people should do with this information [footnote 26]. As perceptions of risk increase, people will be motivated to take protective actions and should be guided as to what actions are the most appropriate. As risks decrease, people will need reminding about what actions (such as hand washing, mask wearing) must be maintained and advised on what activities are safe to resume. JBC and other agencies that communicate changing risk levels should ensure that these communications are accompanied by specific suggestions of what actions should be taken at what level.

Again, co-production of guidance and communication strategies can help to generate an effective collective response to the imposition of local restrictions. Co-producing communication strategies can generate locally salient messages explaining the rationale for measures; what community members should expect; and how community members can support each other.

During a local intervention

During a reimposition of measures, communication and secure access to key social services are crucial.

Communication should include key stakeholders, including public opinion leaders, as part of messaging. Key considerations include:

-

language and vocabulary: The vocabulary used should be appropriate for the target audiences. Authorities must provide as much clear and direct information as possible. Information should emphasize the importance of following official direction.

-

clarity of messaging is important to set out: a) what people had been previously told or asked to do (for example, when restrictions had been imposed earlier); b) what they are being asked to do now (and why); and c) provide explanations of clear indicators for moving to the next phase, and a reflection of what it means for daily life. Information about expected timings should be provided, including clearly defined review and feedback points. This will prevent the situation from feeling endless and more punitive. There should be a standardised timing or quantitative threshold for lifting potential restrictions.

-

social cohesion: A key aspect of successful messaging thus far has been drawing on themes of collective protection; community cohesion; mutual trust and support. These messages are likely to be effective in a national intervention at the local level.

-

designated communication channels: Communication should be timely, factual and convey clearly the level of danger using pre-established channels and social media as appropriate. Conveying factual information as quickly as possible will enhance trust and minimise ‘infodemics’, anxiety and fear.

-

designated communicators: ‘Infodemics’ should also be prevented by allocating designated persons to monitor social media to correct misinformation and provide updates as appropriate.

Clear, consistent explanations from national and local public health authorities about the restrictions should be continued and reinforced. Communications should consider translating abstract restrictions into everyday situations and their meanings for negotiating work and community life.

Consideration should be given to interactive tools or methods that enable local citizens to engage with the infection rate, to understand behaviours that they can engage in to help bring this down, and to enable them to see and celebrate changes in that rate with clear signals about what these changes mean for their safety and behaviours.

Residents cannot adhere to public health measures without appropriate support. The provision of local health, social and mental health services should be highlighted to support the local population as they deal with short, medium and long term challenges. Authorities will need to consider the needs of the general population adhering to restrictions and the significant number of people who will have been contacted by NHS Test and Trace and asked to isolate.

To ensure all residents have the opportunity to adhere to local restrictions, it may be that a defined and explicit package of care for businesses, schools and families will remove resource-related barriers. The details of this package of care should be explicitly communicated at the start of escalated restrictions at the community level.

An important part of motivation is knowing how and when collective adherence will lead to a change in circumstances. As localised restrictions are introduced there should be a clear pathway laid out towards their easing again. An exit strategy with clear criteria must be clearly communicated - lack of guidance on when restrictions would be removed creates a sense of disempowerment and is disruptive.

Trust can be built by the provision of factually correct, consistent, regularly updated information. [footnote 27] Communicators must acknowledge what the previous advice was, identify the new advice and the reasons for the changes, and acknowledge the impacts that the advice will have on daily life when guidance changes. This process must be engaged in repeatedly as locales move into and out of lockdown.

After the local intervention eases

The period after a local intervention eases is as important as the period before. It should not be followed by silence but by an opportunity for a collective processing of the experience. These are important for motivation and legitimacy, especially if future reintroduction of restrictions is a possibility.

Collective processing can engender a sense of procedural justice (for example I (we) accept that the intervention was a reasonable measure even if I (we) experienced inconvenience), but only when measures have been implemented in a community-facing and community-engaged way. This is another reason why co-production in planning and preparation of local restrictions is essential early on. Local authorities should ensure that an evaluation of the restriction is conducted and service providers should review and assess their performance.

Local authorities should work with public health officers to communicate quickly with families, schools, businesses and the media with as much factual detail as possible and appropriate, using pre-established trusted channels on social media. Local authorities should ensure that support workers and primary caregivers have guidance on how to talk with individuals about their concerns or fears related to the re-introduction of restrictions on a local level.

Particular attention should now be paid to the secondary stressors that might occur. These are stressors that continue after the initial impact of an extreme event. Secondary stressors include a variety of issues including economic (such as loss or continuing loss of income), difficulties with compensation (such as the challenge of submitting insurance claims), health impacts (such continuing or new concerns, lack of access), problems with recovery processes, education and schooling (such lack of access to facilities, lack of socialisation), exposure to negative media reports, and familial challenges. Secondary stressors can become evident shortly after an extreme event and persist for extended periods of time. Some will be unique stressors in their own right, while others will become stressors as result of unresolved primary stressors, including policies and plans made prior to events that limit people’s recovery or adaptation. [footnote 28]

Annex A - The example of Leicester

The investigation by the LSE Anthropology team (Dr Nick Long, Professor Laura Bear, Nikita Simpson) of the local intervention applied in Leicester provides several examples of these issues.

Reported compliance with the restrictions was relatively high, (48% extremely closely, 20% very closely, 13% closely and 7% where possible, 12% not closely). Google mobility data for Leicester as of 14 July also suggests reasonable adherence, with retail visits down by 57% (compared to 36% for the UK as a whole) and public transport use down 64% (compared to 43%).

Government communications related to the intervention were reported to be problematic for a number of reasons.

People were sceptical about why the intervention was needed. They felt numbers were only rising because people were being tested more in the city.

There was overall low confidence in the government measures with over two-thirds of respondents agreeing that the government was handling the crisis badly, that the measures would not bring the rates of infection down and that they were not confident the government would end the intervention at the right time.

It was unclear why people were able to travel to work but could not visit friends on the outskirts of town, especially if they met friends outdoors.

The rationale for the physical boundaries of the area of intervention was unclear. People could not understand why certain neighbourhoods were excluded and included. Respondents were especially frustrated by the use of boundaries to restrict access to open green spaces which were seen as essential to well-being.

Other respondents reported that permitted activities seemed to change from day to day.

There was also a perceived mismatch between local and national government communication. The lack of national briefings about the intervention at the local level intensified feelings of exclusion. Respondents reported that previous feelings of being part of a national effort had dissipated.

Overall, Government decision-making that led to the intervention divided opinion on perceived legitimacy. The intervention was highly divisive: people felt that they had been “forgotten” but also had become the ‘Lepers of Leicester’ or the ‘Pariahs of Leicester.’ They felt ‘ashamed’ and like a ‘laughing stock’ because they were still ‘in lockdown’ after the national day of lessening of restrictions on 4 July. National media coverage about this made them feel ashamed and stigmatised, as well as left out from a national story. The ‘lockdown,’ because of its name and its targeting on Leicester was understood as a ‘punishment’.

All groups said they were experiencing despair at the fact that they had to continue with restrictions beyond the 4 July and they were losing hope, as there was no goal (the previous lockdown hadn’t worked) or clear end-point.

The disruption meant people lost a sense of control as they had to cancel plans overnight causing financial expense (cancelled holidays, dental, medical appointments, statutory leave that could not be regained) and potential ill-health as these could not be easily rebooked.

When asked about why the intervention had been necessary in Leicester people responded with racialised explanations (Muslims in secret worship, Indians playing cricket, vulnerable ethnic workers in sweatshops, people who could not read English). These racialised explanations were evident across communities (Hindus about Muslims, white people about other groups, and so on) and also involved self-stigmatisation (it’s our fault because…).

Government and media communications were reported as exacerbating these divisions because these emphasised multigenerational households and or sweatshops.

Respondents said they feared for the future of their multi-ethnic city with the continuing of the intervention and its aftermath.

Annex B - Regional versus national monitoring and responses to clusters among comparator

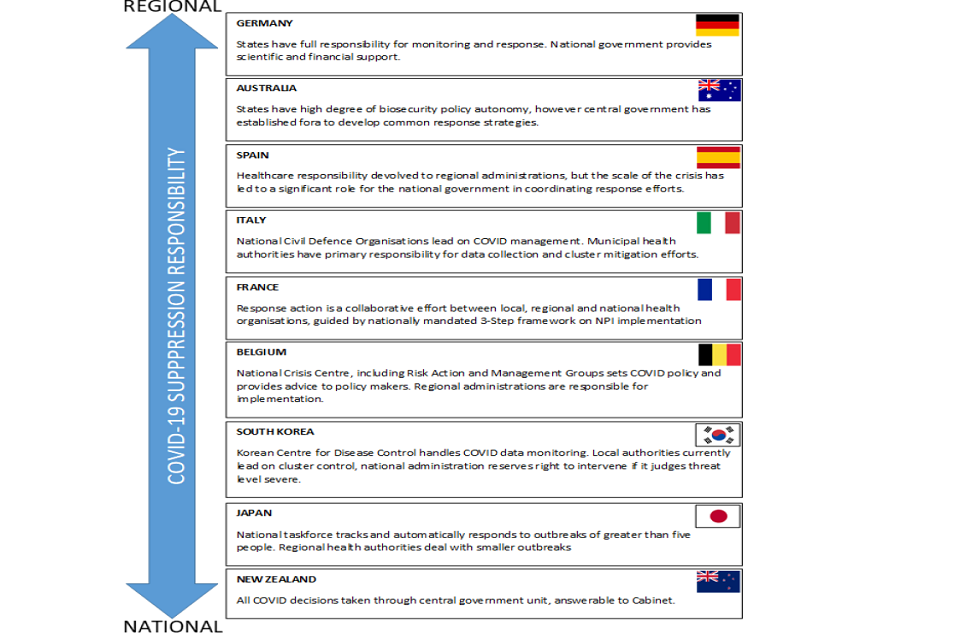

Infographic on how governing COVID-19 suppression varies between countries as lying with national or regional authorities. Listed increasingly national governance focused: Germany, Australia, Spain, Italy, France, Belgium, South Korea, Japan, New Zealand.

COVID-19 suppression responsibility from regional to national

Germany

States have full responsibility for monitoring and response. National government provides scientific and financial support.

Australia

States have high degree of biosecurity policy autonomy, however central government has established fora to develop common response strategies.

Spain

Healthcare responsibility devolved to regional administrations, but the scale of the crisis has led to a significant role for the national government in coordinating response efforts.

Italy

National Civil Defence Organisations lead on COVID management. Municipal health authorities have primary responsibility for data collection and cluster mitigation efforts.

France

Response action is a collaborative effort between local, regional and national health organisations, guided by nationally mandated 3-Step framework on NPI implementation.

Belgium

National Crisis Centre, including Risk Action and Management Groups sets COVID policy and provides advice to policy makers. Regional administrations are responsible for implementation.

South Korea

Korean Centre for Disease Control handles COVID data monitoring. Local authorities currently lead on cluster control, national administration reserves right to intervene if it judges threat level severe.

Japan

National taskforce tracks and automatically responds to outbreaks of greater than 5 people. Regional health authorities deal with smaller outbreaks.

New Zealand

All COVID decisions taken through central government unit, answerable to Cabinet.

Annex C - Victoria Outbreak, Australia

After a long period of few infections, COVID-19 cases are rising again in Australia due to an outbreak in Melbourne, Victoria.

The July 2020 outbreak in the state of Victoria comprises 30 clusters – either based around a social unit (family) or premises (such as hotel, store or school) - ranging in size from 2 to 111. 3 are considered to have been traced and suppressed. A range of suppressive measures have been enacted by the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services in collaboration with other relevant departments (for example Police), including:

- a ‘suburban testing blitz’ of all high-risk areas, with pop-up drive-through testing facilities across the city and door-to-door testing teams. These initiatives seek to test residents in the at-risk areas, regardless of known contact or symptoms – approximately 310,000 people over the coming days.

- level 3 ‘Stay at home’ restrictions placed on those living in 10 postcodes (36 suburbs) across metropolitan Melbourne, enforced by police roadblocks and significant fines.

- closure of dine-in cafes, clubs and restaurants, sporting facilities, beauty parlours and gyms in affected suburbs.

- the Defence Force has been brought in to help guard and transfer travellers from the airport to quarantine, support mass testing sites, and provide logistical support.

- several states have closed their borders to Victoria or implemented quarantines for travellers arriving from Victoria.

- contact tracing from all detected cases by trained health officials bolstered by newly recruited staff, taking it up to 13,000- strong.

- saliva testing, previously discounted by Australia as a reliable testing method due to the absence in country of medical devices certified for saliva analysis, has been introduced to complement other forms of testing.

- the introduction of a COVIDSafe app (launched on 26 April and fully operational on 12 May) aims to supplement and speed up tracing. While the app has had 6.4 million downloads, it has not apparently yet detected a case unknown to contact tracers.

- ongoing educational campaigns and resources on the importance of social-distancing, personal hygiene practices, PPE and cleaning and disinfecting.

- distancing restrictions and registration requirements in public venues – bars, gyms and so on.

- temporary closure and deep cleaning of any premises with a detected case.

- supporting epidemiological data with genomic data (for example, testing mutations within the virus to determine vectors of infection) to better understand virus transmission.

- sewage testing is being undertaken to spot hidden clusters. This early warning surveillance system can track COVID-19 prevalence in the community by tracing gene presence in raw sewage and was developed by Australia’s National Science Agency and the University of Queensland.

The spike in community infections in Victoria is ongoing and it is too early to know whether the measures will be successful.

Annex D – International comparison of decision making around reintroduction of measures

Measures and decision-making ‘triggers’

In France, exceeding 3,000 new daily cases will reintroduce restriction measures.

If 40% of ICU capacity is reached in Italy, the affected region will have restrictions reintroduced.

Germany uses a federal threshold of 50 new cases per 100,000 residents over a 7-day period.

Denmark will reintroduce restrictive measures if R rises above 1.23.

Decision level and escalation

In Japan, all clusters of 5 or more people are escalated to the National Taskforce for review and the regional authorities can consult the national taskforce for advice on prevention and containment.

In South Korea, there is no specific trigger for escalating to national level, but it is apparent that problems will be dealt with locally unless there is suspicion of wider spread.

In Germany, the decision to re-impose measures after the 50 new cases per 100,000 residents (in a 7-day period) is reached is taken by the government of the respective state in consultation with local authorities.

In France, once potential clusters or ‘complex cases’ are identified by the health social assurance authorities (Assurance Maladie), they must notify the Regional Health Agencies (ARS) who will then take responsibility. The ARS must then urgently notify the relevant Prefecture as well as the Health Ministry in order to ensure information is shared quickly and that measures to manage the situation are decided and implemented quickly.

References

-

Institute of Government. ‘Coronavirus: local lockdowns,’ 2020. ↩ ↩2

-

Department of Health and Social Care. COVID-19 contain framework: a guide for local decision-makers, 2020. ↩

-

SPI-B guidance on co-production is available from the GO-Science secretariat. ↩

-

West R, Michie S, Rubin GJ, et al. Applying principles of behaviour change to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Nature Humun Behaviour 2020;4(5):451-59. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0887-9 [published Online First: 8 May 2020]. ↩

-

Bonell C, Michie S, Reicher S, et al. Harnessing behavioural science in public health campaigns to maintain ‘social distancing’ in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: key principles. ‘Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health’ 2020; Doi: 10.1136/jech-2020-214290. ↩

-

Reicher S, Stott C, Drury J, et al. Facilitating Adherence to Social Distancing Measures during the COVID-19 Pandemic. ‘Report to the Scottish Government’, 2020. ↩

-

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. ‘Implementation Science’ 2011;6(42). ↩

-

Wright L, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Are we all in this together? Longitudinal assessment of cumulative adversities by socioeconomic position in the first 3 weeks of lockdown in the UK. ‘Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health’ 2020; doi:10.1136/jech-2020-214475. ↩

-

Commission for Countering Extremism. ‘COVID-19: How hateful extremists are exploiting the pandemic’, 2020. ↩ ↩2

-

McClelland E, Amlot R, Rogers MB, et al. Psychological and Physical Impacts of Extreme Events on Older Adults: Implications for Communications. ‘Disaster Med Public Health Prep’ 2017;11(1):127-34. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2016.118 [published Online First: 21 September 2016]. ↩

-

Rogers MB, Krieger K, Jones E, et al. Responding to emergencies involving chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) hazards: Information for emergency responders, 2014. ↩

-

Tasmania closes two hospitals to ‘stamp out’ coronavirus outbreak in the north-west ↩

-

McDonald’s Singapore suspends all restaurant operations until May 4 ↩

-

Identifying clusters central to South Korea’s COVID-19 response ↩

-

In one Italian town, we showed mass testing could eradicate the coronavirus. ↩

-

Engbers TA, Thompson MF, Slaper TF. Theory and Measurement in Social Capital Research. Social Indicators Research 2016;132:537-58. ↩

-

WHO. Managing epidemics: Key facts about major deadline diseases, 2018. ↩

-

Rogers MB, Pearce JM. Risk communication, risk perception and behaviour as foundations of effective national security practices. In: Akhgar B, Yates S, eds. Strategic Intelligence Management. Oxford: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann 2013. ↩

-

Rogers MB, Amlot R, Rubin GJ. Investigating the impact of communication materials on public responses to a radiological dispersal device (RDD) attack. Biosecurity and Bioterrorism 2013;11(1):49-58. ↩

-

National Association of School Psychologists. ‘School Safety and Crisis’ Mitigating Negative Psychological Effects of School Lockdowns: Brief Guidance for Schools (A resource from the National Association of School Psychologists). ↩

-

SPI-B. Public Health Messaging for Communities from Different Cultural Backgrounds, presented to SAGE on 23 July 2020. ↩

-

Pearce JM, Rubin GJ, Amlot R, et al. Communicating public health advice after a chemical spill: results from national surveys in the United Kingdom and Poland. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2013;7(1):65-74. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2012.56 [published Online First: 2012/12/12]. ↩

-

Pearce JM, Lindekilde L, Parker D, et al. Communicating with the Public About Marauding Terrorist Firearms Attacks: Results from a Survey Experiment on Factors Influencing Intention to ‘Run, Hide, Tell’ in the United Kingdom and Denmark. Risk Anal 2019;39(8):1675-94. doi: 10.1111/risa.13301 [published Online First: 2019/03/21]. ↩

-

Rogers MB, Amlot R, Rubin GJ, et al. Mediating the social and psychological impacts of terrorist attacks: the role of risk perception and risk communication. Int Rev Psychiatry 2007;19(3):279-88. doi: 10.1080/09540260701349373 [published Online First: 2007/06/15] ↩

-

Lock S, Rubin GJ, Murray V, et al. Secondary stressors and extreme events and disasters: a systematic review of primary research from 2010-2011. PLoS Curr 2012;4 doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.a9b76fed1b2dd5c5bfcfc13c87a2f24f [published Online First: 2012/11/13] ↩