Evaluation of the Safer Streets Fund Round 1, year ending March 2021

Published 11 January 2023

Applies to England and Wales

Executive summary

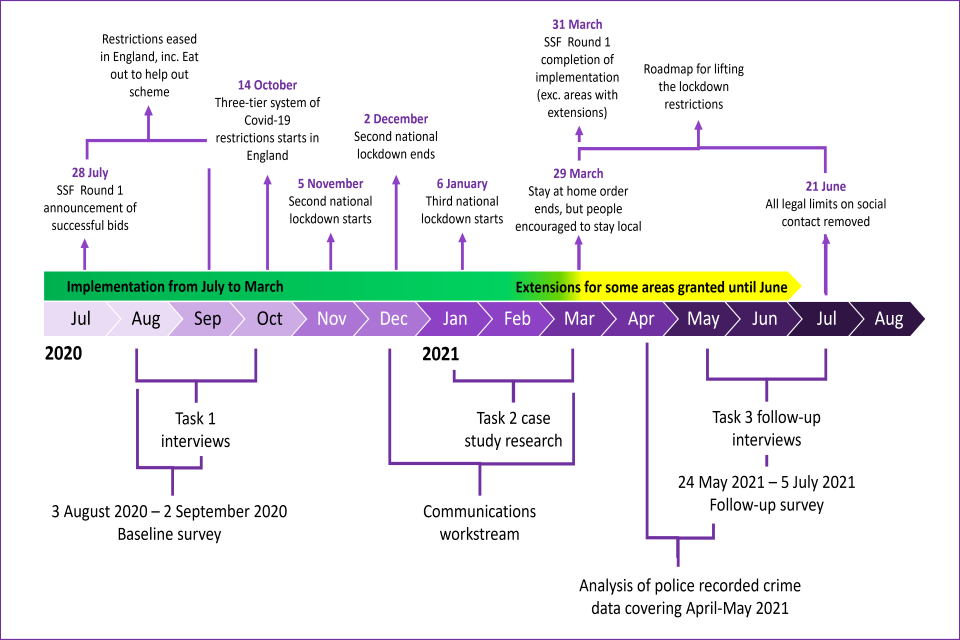

This report presents the findings from an independent evaluation of the Safer Streets Fund Round 1 (SSF1). In October 2019, the Home Office announced a £25 million Safer Streets Fund (SSF) to tackle acquisitive crime in persistently and disproportionately affected residential areas. Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) across England and Wales could bid for funding up to £550,000 for situational interventions aimed at preventing acquisitive crime, using a problem-solving approach. There were 52 successful bid areas across 35 police forces, who implemented their interventions between July 2020 and June 2021, after the Home Office granted an extension to some areas due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic disruptions.

Kantar Public carried the evaluation out between May 2020 and November 2021. It comprised several strands, including a detailed process evaluation that explored how local projects implemented and delivered their SSF1 interventions. The impact evaluation aimed to measure the differences made by the SSF1 programme by analysing police recorded crime data and primary survey data on public perceptions of crime and safety. The report presents the preliminary impact findings below.

Process evaluation findings

The process evaluation strand applied a variety of qualitative research methods and considered a wide range of data sources, including bid reviews, in-depth interviews with members of the bid teams, holistic case study research and analysis of local management information data.

Overall, local PCC teams viewed the SSF1 programme very positively. They understood that its core purpose was to reduce acquisitive crime, but they also saw it as an opportunity to drive wider social change in their communities.

That said, the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic posed a series of major challenges to local areas in implementing their interventions. The lockdown restrictions meant there were unexpected procurement delays, staffing shortages and challenges with resident engagement – all of which contributed to the derailment of their original delivery plans and a degree of financial underspend in some areas.

The local SSF1 teams’ experience of implementation was mixed, and certain critical factors emerged as the key enablers of success. Where these elements were absent, they were found to be barriers to smooth implementation. These included:

- timing was key in shaping the bids; areas typically felt they could have done more to engage local partners and the community if they had more time to develop their grant applications

- strong partnerships between local delivery partners were critical to successful programme delivery; it was important that partnership working was supported by senior leads who could help drive the collaboration at the senior levels

- external input from academics/specialists and a dedicated project manager were important factors for effective delivery of projects

- community engagement was a core part of most programmes and drove wider benefits such as sustainability of the interventions, bringing about a sense of community pride and ownership which further enhanced the impact of the interventions

- there were implementation learnings specific to each intervention; these tended to revolve around the need to improve knowledge of governance processes, generating insight into the community and the target area, and enhancing collaboration with local police teams, local authorities, and delivery partners

Preliminary impact findings

Kantar Public measured possible programme impact on acquisitive crime by analysing survey data and the number of police recorded crime incidents, including both general acquisitive crimes and burglaries. By contrast, the team only measured the impact of the programme on anti-social behaviour by analysing survey data.

The impact findings presented here are preliminary at this stage. This is because of several factors, including delays to implementation that meant baseline and follow-up surveys were started while some projects were ongoing. Further impact analysis is planned with a longer follow-up period, together with an economic evaluation of the costs and benefits associated with the SSF1 programme.

Experiences of key offences

There was minimal evidence of any immediate impact on acquisitive crime from the SSF1 programme. The analysis found no statistically significant impact on estimates using the survey data, and the preliminary analysis of reported acquisitive crimes or burglaries suggested no significant effects during the first quarter of the follow-up period (April to June 2021).

Similar levels of change were seen when exploring anti-social behaviour. While there was a reduction in the likelihood of residents experiencing some types of anti-social behaviour which were not strongly linked to the SSF1 programme, most measures had no significant impact.

Resident perceptions of crime and policing

SSF1 had a statistically significant impact of +7 percentage points (pp) on residents’ likelihood to think that the local police were doing a good or excellent job.

The programme had a statistically significant impact of -9pp on residents’ likelihood to be fairly or very worried about being mugged or robbed, meaning the programme helped reduce residents’ concerns.

Awareness of SSF1 interventions

There was a statistically significant impact (+5pp) on residents’ awareness of the Safer Streets programme, reflecting the efforts many bid areas made in local communications and engagement with residents during implementation, especially around environmental improvement and target hardening.

Resident recollection of information and local communications

One-third of residents in the SSF1 treatment group (32%) had seen or heard information about police and local council activity to tackle crime and anti-social behaviour. Three-quarters (74%) could identify what this was about, most commonly concerning protective measures in the local area (41%), home security measures (35%) or community engagement (23%).

The most popular method to engage residents was through newsletters (29%), followed by Facebook (25%) and in-person visits (18%). Local areas could focus on these means of communication in future projects, as it seems these have worked best for recall by residents in the SSF1.

Conclusions and recommendations

The SSF1 programme has brought several substantial benefits to local police forces and communities by putting interventions in place to reduce acquisitive crime and achieve wider social benefits. While most of the quantitative evaluation impact estimates are not conclusive at this stage, there is evidence to support the conclusion that the programme achieved some of its original aims.

That said, there are clearly lessons to be learnt from the experience of implementing SSF1 and from conducting its evaluation.

For the Home Office and future commissioning practice, the team noted several key learnings to be applied to the next rounds of SSF funding. These include:

- the need to consider the timing of the bid launch and how much resource is available within PCCs to respond, together with allowing sufficient lead-in and preparation time for local areas to develop their bids

- it is vital that PCC areas have access to reliable guidance and best practice information on the sustainability of interventions, community engagement and calculating programme costs; this should include additional guidance for complex interventions

- consideration of a more structured approach to collating practical implementation learnings, building knowledge banks and sharing best practice with PCC areas

For SSF bid teams, the report outlines a series of practical lessons learnt and best practice insights into bid development, programme development and implementation as below:

- early engagement with delivery partners helps develop the bid and secures their commitment later on during the project implementation phase

- community engagement should also happen early in the bid development process, to strengthen residents’ support for the planned interventions

- evidence and specialist expertise are clearly vital elements in developing effective bids and programmes, which can be accessed through expert or academic partners where relevant

- undertake accurate cost projections at the bid development stage, as well as detailed procurement plans and identification of potential suppliers (ideally those with prior experience of delivering similar solutions), to avoid unanticipated costs and delays

- a dedicated bid lead with knowledge of the local area and ownership of all the key relationships with partners is required for effective bid and programme development, progress tracking and impact monitoring

And finally, looking ahead to future evaluation practice, the report recommends several measures that will increase the likelihood of detecting statistically significant impacts, including better timing of the baseline and follow-up periods to avoid overlaps with implementation periods; increased survey sample sizes; and longer police recorded data analysis reference periods to measure long-term impact.

Acknowledgements

Kantar Public relied on the contributions from several parties to evaluate the Safer Streets Fund and report on our findings. First, our thanks go to Professors Nick Tilley and Shane Johnson of UCL for their invaluable advice on methodology, fieldwork, analysis and reporting. We are also grateful to Home Office analysts and policy colleagues for their regular guidance and feedback throughout the evaluation. Our thanks also go to the anonymous peer reviewers who provided us with comments during the reporting stage and finally, to the evaluated project staff and their local residents who gave their time generously to the evaluation process.

1. Introduction

The Home Office commissioned Kantar Public to independently evaluate the Safer Streets Fund (Round 1). This report presents the findings of the process and preliminary impact evaluation carried out between May 2020 and November 2021. Further impact analysis is planned with a longer follow-up period.

1.1 Policy context and background of the Safer Streets Fund

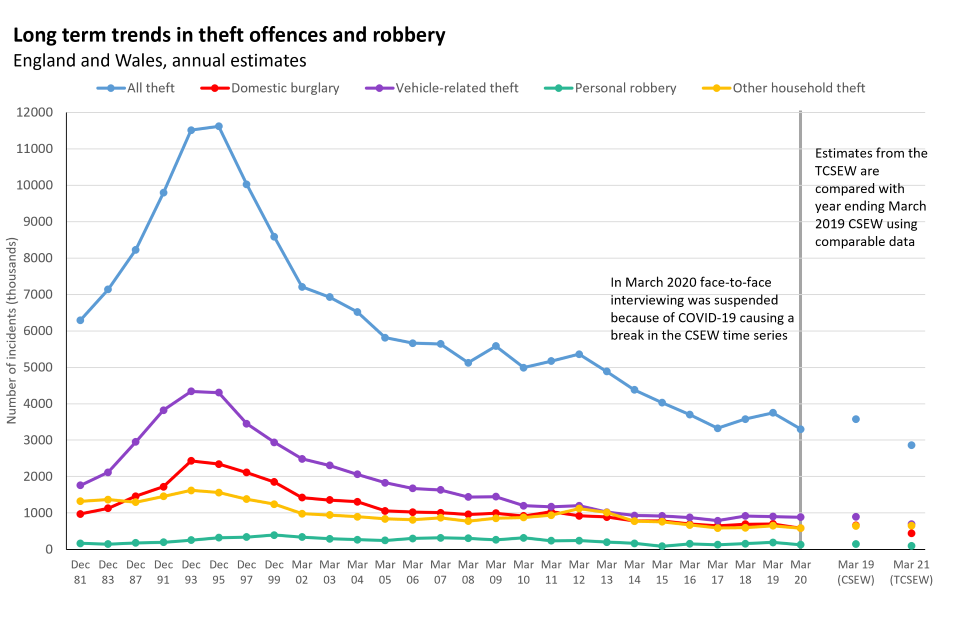

Acquisitive crimes, such as theft, burglary or robbery, constitute over half of crime (excluding fraud and computer misuse) reported to the Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) (ONS, 2020)[footnote 1]. While there has been a sustained decline in acquisitive offences since their peak in 1995, the evidence suggests this trend changed between 2017 and 2019, with the volume of acquisitive offences decreasing again in March 2020 as shown in Figure 1. The Home Office previously estimated the economic and social costs of theft and robbery offences against individuals at around £8bn (Home Office, 2018).

An important contextual element to view the findings of this report against is the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting lockdowns and restrictions in mobility and the impact this had on crime. There have been significant decreases in acquisitive crime during this period due to the reduced opportunities for theft (Kirchmaier & Villa-Llera, 2020). Adjusted crime survey estimates indicate that acquisitive crime has decreased by 31% in the year ending March 2021 compared to the year ending March 2019.

Figure 1: CSEW/TCSEW long-term trends in theft and robbery

Source: ONS (2020, 2022a)

There is ample evidence that relatively simple interventions such as alleygating, street lighting and home security can prevent acquisitive crimes (College of Policing, 2021a). This body of evidence has been built through academic scholarship (see for example, Laycock & Tilley, 2018) and through practical learning experiences of recent government programmes, such as the Reducing Burglary Initiative (RBI)[footnote 2] which was a key element of the overarching Crime Reduction Programme. The Home Office launched the RBI in 1999, which has funded over 200 projects to reduce burglary in local communities.

In this context, the Home Office announced a £25million Safer Streets Fund (SSF) in October 2019, to tackle acquisitive crime in persistently and disproportionately affected areas (Home Office, 2021). Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs) across England and Wales could bid for funding (up to £550,000 per bid) for situational interventions aimed at preventing acquisitive crime and burglary in residential areas using a problem-solving approach (ibid)[footnote 3]. To help PCCs identify suitable interventions, the Home Office commissioned the College of Policing to develop an evidence-based situational crime prevention toolkit (College of Policing, 2021a). The key outcome measures of the Fund were defined as:

-

Impact on acquisitive crime

PCCs could set out plans to target specific acquisitive crime types through their crime prevention plans. These primary crime types and interventions needed to focus on residential areas and cover crimes against individuals and households. -

Impact on other types of crime and disorder

PCCs could also identify secondary types of crime and disorder that are of significance to the local community and can also be targeted through situational interventions (supported by a small amount of the allocated funding). These could include anti-social behaviour, and violence and sexual offences (although the evaluation did not measure impacts on the latter 2). -

Effect on public perceptions of safety, relating to crime and policing

The fund also supports PCCs with improving public perceptions of safety and policing through implementing situational crime prevention interventions in high-crime areas.

In summary, SSF1 attracted 63 bid applications by the end of March 2020, of which 52 successful bids were announced in May 2020.

Most bids (31) focused on various forms of acquisitive crime as their primary target, while some focused on burglary specifically (21). Other secondary crimes included anti-social behaviour, drug-related activity, environmental crimes, criminal damage and violent crime[footnote 4].

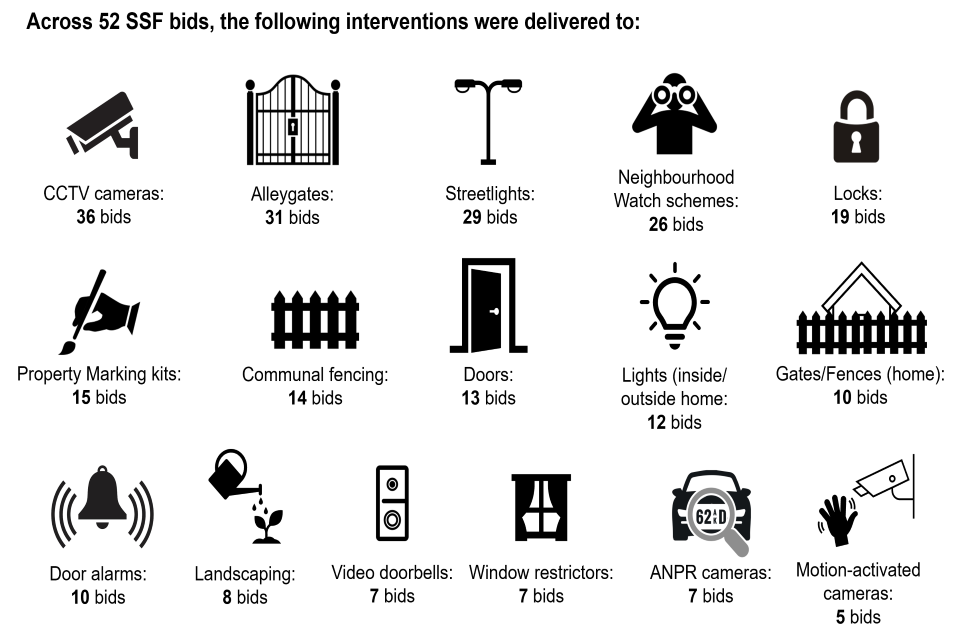

The most frequent intervention types included target hardening of homes (for example, providing locks, doorbells) and communal areas (for example, CCTV, street lighting), as well as measures to help identify stolen property (for example, property marking, Automatic Number Plate Recognition or ANPR), as shown in Figure 2 below. Most areas also engaged with the local community (for example, via Neighbourhood Watch).

The original implementation schedule – planned for June 2020 to March 2021 – had to be extended due to the COVID-19 pandemic. After the Home Office granted an extension, the last local projects finished their implementation in June 2021.

The Home Office awarded bid areas with initial funding of up to £550,000 to support their situational interventions. However, due partly to COVID-19 restrictions, there was some underspend and not all activities could go ahead as planned; many projects changed plans to interventions they were more able to deliver under the circumstances. Additionally, 11 projects were allocated additional funding in the year through a mini competition after the original allocations whilst 32 were granted an extension to allow more time for implementation[footnote 5].

Of all bid areas, 22 did not report any underspend and 8 bid areas reported an underspend of over 10%. Of these 8 areas, the underspend percentage ranged from 11% to 51%. The total underspend across all bid areas was 4.91%[footnote 6] – a fairly typical outcome for a fund of this size.

Figure 2: Overview of SSF1 interventions (from bid analysis, completed as of September 2020)

As an indication, projects were funded to deliver the following interventions. However, some changes were made given difficulties delivering certain interventions during COVID-19.

1.2 Evaluation objectives

The evaluation of the SSF1 programme aimed to provide both an impact assessment and process learning through a combination of local project level evaluations and programme level evidence synthesis. The core objectives of this evaluation were to:

- Explore whether, and how, funded projects help to reduce acquisitive crimes and have other benefits (Sections 2.3, 2.4, 2.5, 2.6 and 3).

- Produce evidence that can be useful to practitioners and policymakers interested in reducing acquisitive (and other) crimes (Sections 2.3.1, 2.5 and 3.1).

- Support each area with their local evaluation activities and establishing tools and guidance that ensure consistency and commonality across projects, besides Kantar Public’s own evaluation activities (Sections 2.2, 2.7, 2.7.2, 3 and 4).

- Bring together findings across areas through a common outcomes framework and project clustering by intended effects, intervention approach and local contexts.

This report addresses these objectives throughout the process evaluation (Section 2) and the impact evaluation (Section 3).

1.3 Evaluation approach and methods

The evaluation of the SSF used multiple evidence streams to provide an account of the process and impact of local interventions. This section outlines a summary of the evaluation approach and specific research methods; Appendix D provides a more detailed methodology. A key part of the initial scoping phase was a thorough review of all 52 successful SSF bids, which were analysed to gain a deeper understanding of local interventions, and to inform the subsequent design of quantitative and qualitative research materials.

1.3.1 Process evaluation approach

The process evaluation aimed to explore in detail the experiences of local SSF teams and their journeys from bid development to planning and implementation of their interventions. This element drew largely on qualitative primary research data gathered from local SSF delivery teams, combined with additional data sources such as original bid documentation. The insights shed light on several factors that facilitated a successful implementation of situational crime prevention interventions and problem-oriented policing approaches. They also helped to understand some of the key barriers and lessons learnt from the implementation experience.

The process evaluation had an iterative approach and fed emerging evidence into the impact evaluation strand to complement the quantitative data analysis. In summary, there were 3 main tasks:

Task 1: Initial bid area engagement and data collection (August to October 2020)

Telephone interviews with the PCC or delivery leads in 35 successful bid areas and in 6 unsuccessful bid areas.

Task 2: Holistic case study research (January to March 2021)

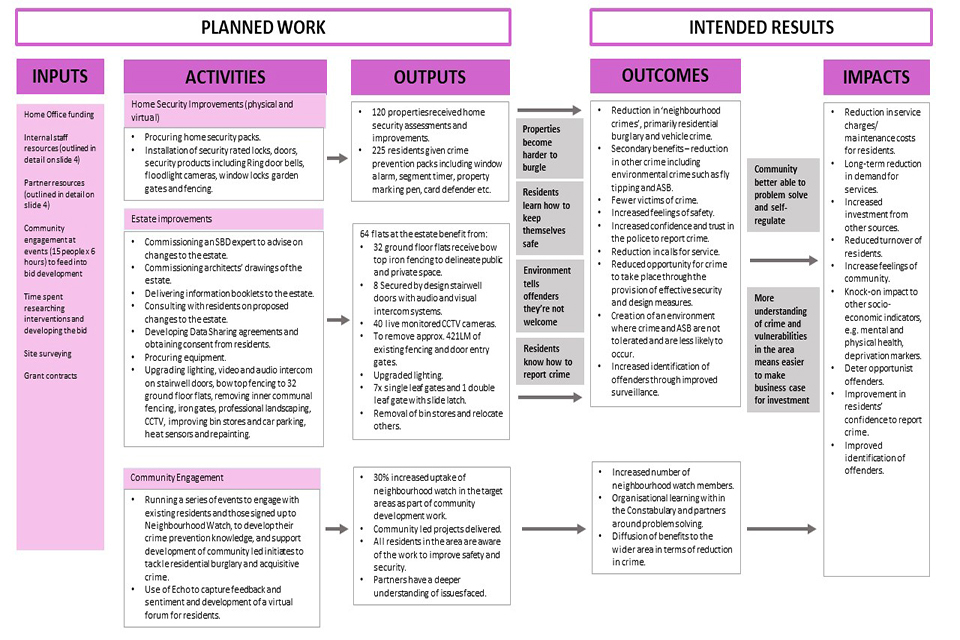

The evaluation team selected case studies reflective of the overall make-up of SSF areas covering all the key area characteristics, types of interventions, and target crimes of interest. The team explored the local implementation experience through in-depth interviews with bid team members leading the key interventions, and included an interactive exercise to draw up local level Theory of Change (ToC) models to help the evaluation team understand how the planned activities would result in a set of measurable outcomes[footnote 7]. The development of a ToC in collaboration with local delivery teams was a valuable exercise as it helped clarify how interventions were expected to work on the ground in the selected case study areas.

Task 3: Follow-up in-depth telephone interviews (May to July 2021)

A final round of in-depth telephone interviews with 35 local delivery leads when most areas had finished or were close to finishing their implementation of planned interventions.

Communications workstream (December 2020 to March 2021)

In response to a need from local PCC areas for more support around how best to communicate with their local communities, Kantar Public also conducted 10 one-hour interviews with communication leads of 6 SSF and 4 non-SSF police forces and then produced a separate guidance document as outlined in Section 3.1.

The process evaluation findings (Section 2) provide detailed analysis, learnings and implications for practitioners implementing crime prevention measures. The section has learnings drawn from the experiences of all bid areas which participated in this evaluation. Specific learnings and implications are provided on all stages of the project process, from bid development through to project delivery and intervention-specific learnings.

Figure 3 shows the timeline of key dates for the impact and process evaluation, alongside the implementation period related to SSF Round 1, and the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns that coincided with this activity.

Figure 3: Timeline of SSF implementation, evaluation activities, and COVID-19 pandemic restrictions

1.3.2 Impact evaluation approach

The impact evaluation used 2 approaches:

- Using the synthetic control methodology to analyse police recorded crime data, comparing the outcomes in treatment areas to those in synthetic control areas.

- Applying a difference-in-difference (DiD) analysis to metrics measured in repeated cross-sectional surveys of local residents in treatment and control areas. This is referred to as ‘survey-based impact analysis’ in the discussion of the impact results.

Analysis of police recorded crime data

To assess the impact of SSF interventions on reported crime (including acquisitive crime and burglary, relating to outcome i), the analysis of police recorded crime data drew on official data sources including the Home Office’s Data Hub and police.co.uk data.

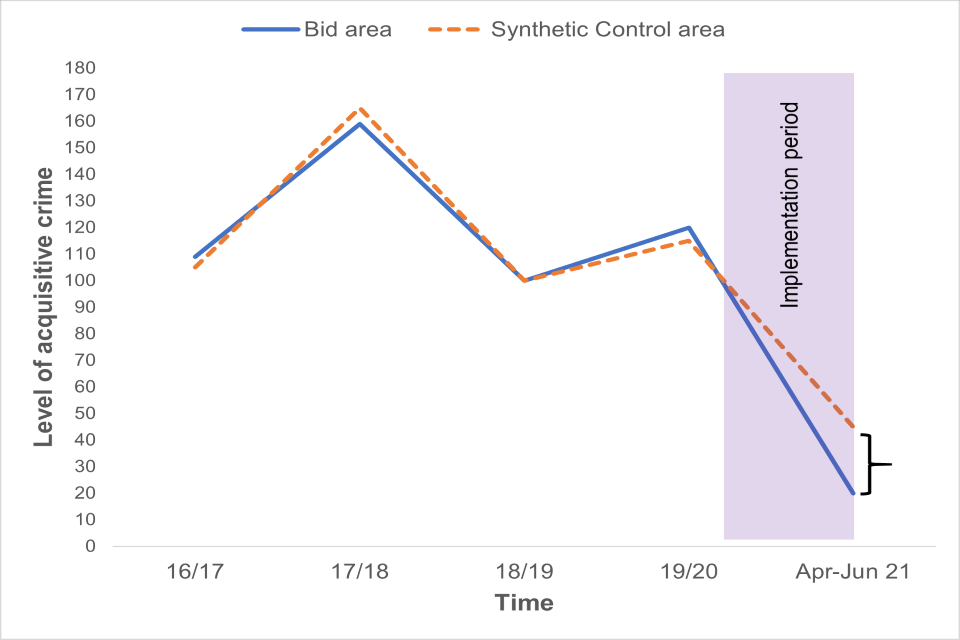

Kantar Public used a time series of police recorded acquisitive crime data to analyse the preliminary impact of the fund. The admin data period for this preliminary analysis was based on April to June 2021. Further impact analysis is planned with a longer follow-up period based on a year of data (1 April 2021 to 31 March 2022). The team used the synthetic controls method (Abadie, 2010)[footnote 8] to generate a control group for each of the successful SSF bid areas, considering crime rates and a variety of population statistics in the matching criteria using historic DataHub data (covering years ending 31 March 2017 to 2020). This method uses a weighted average of multiple control areas (census Lower Layer Super Output Areas or LSOAs[footnote 9]) to create an artificial control group, whose trend (in police recorded crime) before introducing the fund is closely matched to the trend in the SSF bid area.

The measurement of the impact of the fund comes from comparing the level of crime in the synthetic control areas to those in the SSF treatment areas, after administering the interventions (see Appendix D), Figure 7).

For this analysis, the team measured the level of crime as the number of reported crimes recorded in either DataHub or police.co.uk data[footnote 10]. When impact estimates are reported throughout this report, they represent the difference between the number of acquisitive crimes/burglaries (as applicable) reported in a bid area and the synthetic control estimate for that bid area.

Survey-based impact analysis

To assess the impact of the SSF interventions on public perceptions of crime and policing (outcome measure 3) as well as selected other crimes such as anti-social behaviour (ASB) (outcome 2), the team designed repeat cross-sectional surveys at pre- and post-implementation intervals[footnote 11].

In reality, the team had to conduct the follow-up survey while some of the local areas were still implementing their SSF interventions due to the COVID-19 related implementation difficulties and delays.

The team conducted the resident surveys in each successful bid area, and in 104 control areas (2 control LSOAs were selected for each successful bid area), which were matched using Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM) techniques (Iacus et al., 2009) to constitute a robust counterfactual.

The survey data was collected using an Address-Based Online Surveying (ABOS) methodology (Williams, 2016) with local addresses being randomly sampled from Royal Mail’s database of delivery points (PAF).

In summary, the baseline and follow-up survey achieved the following:

- baseline survey (3 August to 2 September 2020) – 4,318 achieved completed surveys comprising 1,834 paper completes and 2,484 online completes (20.6% response rate); 3,212 completes were in SSF areas[footnote 12] (treatment areas: 20.4% response rate, control areas: 21.1% response rate)

- follow-up survey (24 May to 5 July 2021) – 3,630 achieved completed surveys comprising 1,572 paper completes and 2,058 online completes (17.3% response rate); 2,720 completes were in SSF areas (treatment areas: 17.3% response rate, control areas: 17.4% response rate)

After collecting, processing and weighting all the survey data (more detail about this is available in the Appendix D, the team conducted DiD analysis to assess the impact that SSF interventions had on a range of observed outcomes (HM Treasury, 2020). This analysis measured the change in outcomes for treatment areas (SSF area residents) at 2 points in time (pre- and post-programme) and compared this change with the trend in outcomes experienced by non-SSF residents in the control group areas over the same time period. The difference between these 2 levels of change is the impact attributed to the SSF interventions, as illustrated in Figure 4. As a note, the DiD analysis also controlled for the differential impact of the prevalent COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in each area[footnote 13].

Figure 4: Difference-in-difference analysis

All survey data was subject to sampling error, which may have caused changes in the same measures between collection points. Statistical significance testing helped to determine which changes could be attributed to the programme, rather than any random error. The DiD analysis focused on impact findings that were statistically significant at the 5% level. This means that if the survey were to be conducted 100 times, there would be a finding of the same nature on at least 95 occasions. These statistically significant findings in the discussion of results are referred to as significant impacts.

This report provides impact estimates as percentage points (pp). For example, the SSF1 programme had a significant impact of +5pp on residents’ awareness of the Safer Streets programme.

Economic evaluation

If the longer-term impact analysis (based on 12 months of recorded crime data) indicates that SSF1 has led to a reduction in crime, a full economic evaluation will then be conducted. This would likely use the Home Office economic and social costs of crime framework (Home Office, 2018), in conjunction with the Manning cost-benefit tool (College of Policing, 2021b). Such an evaluation would monetise the overall benefits associated with SSF1.

2. Process evaluation findings

This section details the findings from the process evaluation of the SSF implementation experience. The aim here was to establish to what extent the programme has been delivered according to plan, to reflect on the implementation experience, identify any early impacts perceived by implementation teams and highlight lessons learnt.

As outlined in Section 1, this strand drew on a variety of data sources, including primary qualitative research data collected via in-depth telephone interviews with all the local project leads as part of Task 1 and 3. To explore the implementation journey from a holistic viewpoint, the Task 2 case study element comprised a range of data collection and analysis techniques – such as initial reviews of the SSF bid documentation, in-depth interviews with project leads and/or intervention delivery leads for the key interventions (covering CCTV, alleygating, home security improvements, community engagement, communication), local ToC workshops and analysis of local level project data.

The ToC models helped to identify factors that were not initially acknowledged as having a major bearing on programme performance, such as unforeseen procurement delays or the importance of strong partnerships. The latter point – having a set of effective partnerships across delivery organisations – came out particularly strongly as one of the key change mechanisms in that it helped enable positive outcomes. Other such contextual factors included the ability of local teams to adapt in response to challenges such as COVID-19 and Brexit, and their approaches to community engagement in helping to support sustainable outcomes.

2.1 Bid development and programme set-up experience

There was a strong positive response among bid areas to the announcement of the SSF and the opportunity to bring about change in communities. While the core funding objective was to reduce acquisitive crime, many teams also saw SSF as an opportunity to drive broader change in their local areas. The funding provided an opportunity to improve negative attitudes towards the police and other public services. Bid teams also felt that the funding could have a positive impact on public safety and therefore improve community cohesion, engagement, and pride in the area.

Overall, bid teams felt designing the SSF bids was highly collaborative with a strong partnership approach. In most cases, the key partners – the PCC, the police and the local authority – pooled resources to pull together the bid. Typically, the PCC played a pivotal role in bringing together the partners and coordinating the information and insights required for the bid.

In the process of bid development, several fundamental steps were common across all bid areas, though some teams undertook additional steps. Figure 5 summarises these steps. Note that while the figure illustrates the steps in a linear way, they often occurred simultaneously. The boxes with dotted lines represent additional steps taken by some teams.

Figure 5: Typical SSF bid development process

2.1.1 Target area identification

The first step in bid development was usually analysts on the policing team within the respective bid areas identifying LSOAs (unit of geography as defined by the Home Office in the SSF1 programme) and analysing crime data to identify LSOAs which fit the bid criteria. Where there were multiple LSOAs that fit the criteria and met the acquisitive crime benchmarks, teams usually selected the areas with the highest scores to include in the bid. While crime data was a central data source used by all teams, other sources of information included borough data, MOSAIC data (consumer classification data), and data from the fire and rescue services.

2.1.2 Stakeholder engagement

In most cases, the PCC co-ordinated between partners during bid development. The local authority and the police were key stakeholders and partners across all bid areas. Depending on the area, other partners included the fire and rescue services, local community organisations, housing associations and housing departments from the local authority.

At this stage, several teams formed Project Overview and Project Delivery boards that would have oversight of the programme, should funding be secured.

2.1.3 Area analysis

Teams usually conducted analysis of the target LSOA areas to establish the type of housing in the area and crime hotspots, through a combination of data analysis and day and night walkabouts by the policing team.

At this stage, the Designing Out Crime Officers tended to conduct Environment Visual Audits (EVAs). This was a critical step in the process as it was a key input into the choice of interventions and the target primary and secondary crimes.

2.1.4 Resident engagement

Only a small proportion of bid areas engaged with residents to develop their bid. Teams expressed that they would have liked to engage residents but could not do so because of the limited time available, as they saw it.

However, a few teams (approximately 10% of all the bid areas) mentioned that they carried out ‘light touch’ engagement initiatives. The method of engagement tended to be focus group discussions, either face-to-face or online, or through existing online engagement platforms.

Some example initiatives included:

- activities organised next to schools/nurseries around the time of drop-off so that teams could speak to parents returning from school

- engagement with a university within the LSOA to discuss the impact of crime

- discussions with retailers in the area

- a 3-day door knock initiative

- a community clean-up to help the team meet and conduct conversations with residents

Teams felt these community engagement initiatives were a critical supplement to the information from the EVA. However, there were some concerns that engaging with residents could lead to expectations that would not be fulfilled if funding bids were unsuccessful.

2.1.5 Asset and partner identification

There were bid areas which identified ‘assets’ (included existing networks, local organisations, volunteers and existing programmes that could be leveraged to help develop and implement the SSF1 programme) and partners as part of the bid development process. These teams collaborated to identity potential community assets and networks (for example, community organisations, residents’ groups, community representatives and key influencers).

2.1.6 Bid writing

Usually the PCC lead wrote the bid. Most teams said they were familiar with the SARA decision-making model (Scanning, Analysis, Response and Assessment) and had either applied it to their analysis or that the layout of the bid aligned with the SARA model requirements, which enabled them to comply with it[footnote 14]. Only a small minority of bid development teams were unaware of the model.

2.1.7 Feedback on the bid process

Most teams felt the bid guidance document was well-structured and they appreciated the directive instructions. Supporting resources such as the toolkits and seminars were felt to be highly valuable resources. The menu of interventions (as outlined in the SSF Toolkit) and supporting impact evidence (for example, in the Crime Reduction Toolkit from the College of Policing) were central to the choice of interventions and design of the respective bids. The bid submission platform and process were also reported to be straightforward and practical to use.

“We drew heavily on the College of Policing’s toolkit and the academic research to think about the vulnerability of the properties.”

There was consistent positive feedback on the Home Office’s support throughout the process. Bid teams regarded the Home Office as responsive and helpful to queries. The extension to the submission deadline was also highly appreciated and enabled some bid areas to assess the feasibility of the bid and, to an extent, engage relevant stakeholders.

However, most areas felt that the timings and the application requirements were key challenges that negatively impacted their bids. The timing of the bid launch was challenging for bid areas. As the fund was launched during the summer, staff being on leave during school holidays reduced resource, and teams were less able to coordinate efforts and engage partners. This resulted in inadequate community and partner engagement, and less research conducted about the area.

The uncertainty of the COVID-19 pandemic also presented a challenge. Resources diverted to COVID-19 pandemic responses reduced staffing and capacity. Areas also had to adapt to the uncertainty of potentially navigating national and local lockdown restrictions in the future.

“The biggest challenge was in the time scales. There was a lot of data to work through and engaging with local communities was not easy to do quickly.”

Despite the extension for submission, many teams felt that the time allocated for bid development was inadequate. The lack of bid development time was also cited as a key reason that some areas did not submit multiple bids (to cover more than one crime area, as outlined in the bid guidance).

Bid teams also reported issues with the application requirements. One challenge related to the requirement to use LSOAs, as some teams record their crime data via ‘beat areas’, which are different to LSOAs. To see LSOA data, an extensive re-mapping exercise was required, adding more time to an already tightly timed process.

“Police don’t have information via LSOAs, they have it via their ‘beat’. We had to get special permission from the council’s data team.”

“Felt like the HO [Home Office] was naïve in expecting bid areas to do a full-on academic exercise when there are better ways of providing evidence – was just a bureaucratic exercise that could be slimmed down; the volume of paperwork was overwhelming and didn’t marry up with the timescales.’’

A further challenge was that some teams felt that to fulfil the bid criteria, they had to select areas that would not otherwise have been their first priority. For example, there were areas which were a priority for the police but had a mix of domestic and commercial properties and so had to be excluded due to the bid criteria (which for SSF1 focused on residential areas, and crimes against individuals and households).

Bid teams in more rural areas raised a final issue. They felt the criteria and LSOA requirement was an urban bias, despite acquisitive crime also affecting rural areas. This feedback informed the next round of SSF investment as the Home Office adapted the eligibility of the fund to ensure non-conterminous rural areas were in scope along with commercial areas.

“Criteria from HO [Home Office] was very strict – wanted to do a rural bid but couldn’t make the criteria fit, would have been better if it wasn’t so restrictive.’’

2.2 Overall programme implementation experience

The Home Office announced the successful areas in May 2020 with the funding scheduled to end by 31 March 2021. Due to the delivery challenges, 32 bid areas applied for and were granted an extension to the funding until the end of June 2021.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the implications of Brexit strongly affected the implementation of local SSF interventions. COVID-19 impacted on resource as staff were diverted to work on local COVID-related activities such as test and trace. National and local lockdowns and social distancing requirements also made it challenging for areas to implement interventions as planned, thereby curtailing the ability to conduct in-person events and encourage resident take-up. Brexit primarily caused shipping delays, although there were also references to certain products being limited. However, the extension to the programme timeline (from March to June 2021) for some of the SSF project areas enabled bid areas to progress on delivery and adapt their programme plans and schedules.

“We were impacted by Brexit – the CCTV equipment we’d ordered was held up at the docks for over 3 months.”

Some common factors emerged across bid areas in their approach to implementation:

Central resources and evidence were used for programme design.

Bid areas reported using evidence primarily for intervention selection at bid development. Key sources included the What Works toolkit, College of Policing website and Police Crime Prevention Initiatives blogs. [footnote 15]

Across bid areas, the core partners for implementation and delivery consisted of the PCC, constabulary and local authority.

Other partners included within various bids included housing associations, Neighbourhood Watch teams, Community Safety Partnerships and other local community organisations.

Bid areas demonstrated flexibility and resilience in their implementation approach. Despite challenges posed by Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic, most bid areas adapted their programme plans and how they approached intervention delivery to successfully complete intervention. Examples of adaptations included engaging with communities virtually, different communication approaches and extending target areas.

Proactive measures were taken to ensure the sustainability of interventions.

Bid areas reported taking specific measures during the implementation phase to ensure sustainability of the interventions. Examples included CCTV contracts that extended beyond the programme period, having a choice of home security products accredited by Secured by Design and offering ongoing advice to residents.

Some areas interviewed also reported a ‘behaviour change approach’ to bring about positive changes in the community, to ensure sustainability of some interventions. This referred to initiatives aimed at positive changes in behaviour amongst residents that may help to ensure continued effectiveness of the interventions. For example, communication campaigns targeted at students to drive the practise of locking doors and windows in their home, as a support to interventions focused on target hardening of homes.

2.2.1 Key enablers of a successful implementation

Interviews with the project and intervention leads revealed key factors that they believed contributed to the overall success of programme delivery.

a) Partnership working

Having strong relationships between implementing partners was seen as core to a successful project. Areas that had established and strong relationships with their partners felt they were key to helping them overcome process delays, reach hard-to-engage groups and collect additional information about the community. Good partner relationships also helped with the need to work flexibly and to tight timescales. This was particularly critical given the unprecedented nature of working through the COVID-19 pandemic, where there was a constant need to adapt and respond to new challenges. Successful collaborative working was facilitated by open communication and by all partners feeling as if they were working towards the same goal.

Case study 1 – Partnership working

To deliver target hardening, a PCC partnered with an arms-length management organisation (ALMO) who manages the council’s housing stock of properties. There was already a strong partnership between these 2 organisations, which proved critical as the PCC navigated the unprecedented challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic. This enabled them to work together flexibly throughout lockdowns.

This relationship meant that the partner only claimed for completed work. An acknowledged risk of working with an unknown partner was that it might have been much more challenging in terms of stop-starting throughout that period.

“The lesson we’ve learnt is when you’re trying to deliver projects of this nature – quite a lot of money spent within a very short amount of time – having those really good strong partnerships already established are really critical to guarantee you’re going to achieve those deliverables by the deadline.”

(East Midlands, Urban)

By contrast, in areas where partner relationships had not existed prior to SSF, it took more time to forge them at the start of the programme. This, bid areas felt, could create a barrier to success given the tight timescales and need to act quickly to get the project underway. This highlights the importance of early partner engagement prior to implementation.

Having senior management buy-in and collaboration across partner organisations supported and enabled partnership working. Stakeholders consistently fed back that collaboration between senior leads across organisations helped remove implementation barriers and meant that staff on the ground prioritised the programme. Communication from the top also drove responsibility for the programme within each partner organisation. For these reasons, securing senior management buy-in as early as possible in the programme process is important as it shapes ways of working.

A further benefit of partnership working was that it helped extend the project to include more hard-to-reach groups. Links and relationships within communities could take many years to build. Having partners with existing relationships extended the reach and impact of the project significantly. As an example of this engagement, some local authorities engaged residents and landlords and could thereby identify higher-priority residents.

Case study 2 – Inclusion of hard-to-reach groups

One team worked closely with the housing department of the local authority. This enabled them to link in with them in terms of housing information in the targeted areas.

Because of this, they had access to statistics on repeat victims who became a priority for target hardening. Within the targeted areas, they could therefore analyse the statistics to see who had been a victim of burglary before, and who was older or vulnerable. This allowed them to prioritise and tailor their offer to these residents initially.

“We were able to narrow the scope down to ensure those who were most vulnerable had first priority.”

[Wales, Urban]

Strengthening working relationships with partners could positively impact future programmes beyond just SSF1. As a result, areas felt they could engage partners in future work, which would be valuable in the future.

b) Interventions led by the appropriate teams/individuals

Selecting the right intervention lead was a further enabler of success. Identifying teams and leads that had experience in the intervention being implemented was valuable. This experience was especially critical for interventions such as CCTV and alleygates that had complex administrative requirements. In some cases where a team oversaw multiple bids, they reported different implementation experiences on specific interventions driven by the experience of the lead and partners.

For example, where the local authority was the lead partner for CCTV, areas reported a fairly smooth experience compared to those areas led by the police or the PCC (with limited experience on CCTV installation). Local authorities tended to be responsible for CCTV management and installation so were therefore familiar with both the requirements and processes, and had established suppliers and installation contractors.

c) Dedicated project manager (and effective project management)

An important insight identified by areas with a project manager was the value in having dedicated staff for specific roles – enabling delivery of interventions according to plan. These dedicated staff were better positioned to respond to challenges that arose and established stronger relationships with the different partner organisations.

Case study 3 – Effective project management

Ensuring that SSF was a priority, and that momentum was maintained, was a challenge in one area with a very small community safety team within the local authority. They decided to recruit a dedicated project manager to oversee the delivery and implementation of the project. The team felt that without this dedicated resource, they would not have successfully implemented the programme.

“We went for an ambitious SSF project, with a number of plates spinning. Add in the complexities of COVID-19 to that and we really needed a dedicated person. Having a SSF Project Manager was invaluable.”

(North West England, Urban)

d) Mobilising academic expertise

Some bid areas worked with academics and experts as part of their delivery. The academics were felt to have brought in fresh thinking and approaches that positively influenced delivery. For example, academics encouraged teams to use evidence to help identify what about the interventions had worked and what had not.

Academics, which included professors from nearby universities, also supported bid areas to have measurable objectives and specific initiatives, setting them up to draw learnings for future programmes.

Case study 4 – Mobilising academic expertise

One bid team consulted with 2 professors who guided them throughout the SSF project. They discussed matters such as whether there were elements of their target hardening approach that could be more effective and easier to achieve, given the challenges around timing and other external factors.

This team struggled initially to meet their target hardening implementation targets due to low take-up from the community. They consulted with their academics throughout for advice on which elements they could substitute if required.

“Throughout SSF we were able to ask the academics what elements could be substituted or changed if needed, and what effect that would have. We found it invaluable to have them as a resource.”

(North East England, Urban)

2.2.2 Implications for future programmes for bid areas

SSF areas reflected on the lessons they had learnt as part of the bid development and implementation process.

Area teams identified the following key learnings and implications relating to the bid development stage:

- engaging with delivery partners early in the bid development phase would help to ensure all partners are working to the same expectations and deadlines; as timings are tight and there is a need to be flexible, giving key partners as much warning of this as possible would be beneficial; early engagement could also help to improve the delivery of interventions later, should the bid be successful.

- engaging and consulting with residents during the bid development phase could help with resident support for the interventions and future sustainability

- focusing on accurate cost projections at bid development and investing time up front to identify suppliers could save time and help mitigate against unexpected budget changes

- having a dedicated lead who knows the area and has contacts could help when developing the bid, to ensure inclusion of the relevant people and information

Area teams identified the following key learnings relating to implementation:

- as with at the bid development stage, ensuring that partners are engaged early on and committed to the joint planning of delivery can help to ensure adherence to initial plans

- select experienced intervention partners with prior experience of delivering the intervention and/or partners who understand and know how best to engage with the local community

- allocate a dedicated programme manager or delivery staff where possible, which can help to mitigate against ‘drift and delay’ when coordinating with multiple partners

- leverage academic or external expertise, where relevant, to support evidence gathering and inject fresh thinking

- establishing a clear plan for tracking and measurement to track programme delivery and gather learnings on impact, possibly done in conjunction and with support from an academic partner

- establish a line of direct communication with the community to help gather feedback and, if required, adapt the approach or delivery

2.2.3 Implications for future programmes for the Home Office

SSF areas identified the following learnings and implications for the Home Office to consider at the bid development and implementation phases of future programmes:

Consider the timing of the bid launch

The timing of the launch can have a big impact on the resource available for teams to develop quality bids. Where possible, avoid holiday periods and other major funding applications and deadlines.

Offer longer lead time for bid development

Ensuring there is adequate time for teams to conduct local research and engagement is key to ensuring bid plans are well researched and set up for delivery.

Provide guidance and best practice information on the sustainability of interventions, community engagement and calculating programme costs

Central resources and toolkits, such as best practice examples for different interventions and practical examples, could help to support intervention sustainability and community engagement. Also include additional guidance in the suite of central resources on considerations and approaches to costing.

Provide additional guidance

On implementation processes (especially for those interventions with complex governance requirements).

A structured approach to collating these learnings

This would deliver a valuable resource for future programmes. Areas have built strong banks of knowledge on interventions (such as CCTV), community engagement and target hardening in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions.

There is also an opportunity to share best practice where specific target groups have been engaged successfully

Groups such as students or landlords require a customised approach and sharing information across areas implementing programmes for these audiences will help in implementation. Like the communications workstream, there is an opportunity to use learnings from non-SSF areas as well (where this has been addressed successfully).

2.3 Selected SSF intervention-specific learnings

To support future policy development, and also help local areas with implementing future interventions, the process evaluation also distilled several key learnings from implementing specific interventions. This section presents a selection of intervention implementation experiences – including CCTV, target hardening of homes and of public spaces, community engagement, and communications – together with key implications for future commissioning and practical recommendations.

2.3.1 CCTV

Seven out of 11 case study areas included CCTV as an intervention in their programme (overall 36 out of the total 52 areas implemented CCTV). Areas felt this deterred acquisitive crime and helped to bring down fly-tipping and ASB. CCTV was popular among residents, though implementation could produce some political challenges among delivery partners. Successful implementation often depended on the delivery team’s prior experience with CCTV.

2.3.2 Key enablers of a successful implementation

Implemented by an experienced team: teams that were new to CCTV installation often found it difficult to navigate the complex requirements; however, experienced teams found it simple to implement, having good awareness of the time and information required. Overall, local authority-led implementation teams had more experience of CCTV than police/PCC teams and these teams felt that implementation had progressed smoothly.

Holistic approach to CCTV placement: many teams used police and crime data as well as insight from other organisations (such as Safer Neighbourhoods teams within the council, or police teams targeting car crime) to identify the crime hotspots where CCTV would be most effectively placed.

“We could coordinate it in with crime data, and organised crime groups. Council also advised on locations and data protection issues. Took bit of time as it’s beyond the scope of PCC experience but had good partnership working with the council.”

Enabled responsiveness to community: in some areas, particular groups (such as residents and landlords of social housing) were supportive of CCTV and had specific requests for installation locations. SSF1 teams could meet these requests and install CCTV where the community wanted them.

“Land owned by registered social landlords, who were keen to have CCTV, so good partnership working. There were some estates with high deprivation levels where residents were quite keen, too.”

High visibility and proactive communication: CCTV was regarded as particularly effective when accompanied by highly visible communications about its presence. Stakeholders interviewed fed back that communication not only helped deter potential offenders, but it also helped to mitigate concerns about privacy among residents and the wider community. Study areas felt that proactive communication through media activity and community engagement helped to reassure residents about privacy issues while acting as a deterrent to potential offenders.

“We heard in a seminar and also from Keep Britain Tidy that the main deterrent of CCTV is the perpetrator thinking that they’ll get caught, so we promoted the message of CCTV presence via luminous signs on lamp posts saying everything is being filmed. Put flyers through doors. Anybody who lives in that street or visits that street will know that the surveillance is good.”

“I think residents are so frustrated with crime in the area, that every person who we spoke to was over the moon with the cameras.”

2.3.3 Key barriers to successful implementation

Complex governance requirements: in some areas, where police and PCC delivery teams had limited experience of CCTV, a lack of understanding of the complex processes involved resulted in delays. Commonly unanticipated issues included the need to secure planning permission, data protection requirements, the need to coordinate with existing CCTV systems, and plans for ongoing maintenance. Some stakeholders interviewed felt that non-police-led teams sometimes had not considered the quality or positioning required by the justice system (for example, for license plates to be visible for ANPR).

“Would have been easier if CCTV had been implemented by local authority rather than by the police … therefore we had to learn on the hoof, and then discover who we had to speak to, and then try and get them on board, and bringing them across considering they were miffed that they weren’t included.”

Areas felt implementation was particularly complex when multiple authorities were involved (such as, county authority, city authority), where the delivery team did not own the CCTV system or when the buildings where CCTV was to be installed were not owned by the implementing organisation.

Processes were further slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic as members of staff were on sick leave and resource was diverted to respond to the pandemic. A lack of clear communication between partners about expectations could lead to a reduction in effectiveness of CCTV; for example, if live monitoring of CCTV feeds is not included in provision.

“We underestimated the kind of CCTV and the cost required to get quality footage which is viable in a criminal case. Cameras need to be of a public commercial system and planning required is also significant … governance and policies around why it is being done, planning from a coverage point of view, total coverage of hotspots, ongoing maintenance, etc.”

Conflicting priorities: a few areas reported political differences or a lack of alignment between partners, resulting in delays or non-implementation. For example, in one area, funding for monitoring for CCTV had been recently removed, meaning that there was some sensitivity involved in reintroducing it. In other areas, the CCTV project overlapped with existing CCTV programmes, or fell under multiple jurisdictions, potentially leading to tension.

“Some of the cameras are on bordering LSOAs where there are different community councillors; this has ruffled the feathers of some other councillors and is a lesson for us in the future that we make sure all stakeholders from neighbouring LSOAs are engaged.”

Response from crime groups: in a few areas, newly installed CCTV was vandalised by organised crime groups. Bid areas felt that a plan should be in place to protect from vandalism when implementing CCTV in the future.

“We have got a bit of footage and some stills of this guy in military fatigues and a balaclava chopping this down within 24 hours or attacking it to the point where it had to be removed because it was unsafe.”

2.4 Target hardening of public spaces

Target hardening was anything that deterred, distracted or delayed, and included street lighting, fencing, alleygating, installation of communal doors, and working with the community to transform public spaces into allotments and playgrounds. Often, environmental improvements increased the community’s use of the area, making illegal activity more difficult.

2.4.1 Key enablers of a successful implementation

Straightforward to implement: many bid areas reported that the delivery of certain interventions such as street lighting and fencing was straightforward because of the simple processes involved. This contrasts with other interventions, such as CCTV, that had greater administrative or technological complexities or could be opposed by some residents.

Positive impact on perceptions of the area and SSF: there were reports of a very positive community response to certain initiatives that improved the local environment (for example, removing graffiti, creating community gardens) and those which had helped to eliminate long-standing ‘problem areas’ raised by the community (for example, demolishing disused garages). Bid areas reported that such measures had improved how people felt about the area and, by extension, about the SSF programme.

“People have been thrilled to see them; it’s made a huge difference. In consultation, people feel unsafe when they’re walking through an area covered in litter and graffiti, and what this has done has helped actually lift the area.”

“Demolishing of 15 garages behind a fencing area helped improve the area from drug activity, and residents gave positive feedback – not part of original bid’’

“It was adjacent to a hotspot of theft and robbery, into a place that is now much more open and accessible for all to use.”

Drove community engagement and ownership: as environmental improvements often created opportunities for residents to have a say in decision-making, bid areas believe there will be greater ongoing ownership of the projects, potentially improving the sustainability of the interventions.

“Residents are watering the plants daily and eating the veg! But also ensuring the plants are maintained and taking ownership of it.”

“Thinks it’s gone better than had done previously, because now [we] have a local voluntary group – they managed contracts for SS and picked litter up and got rid of weeds – really helped.”

“It really created a buzz for the community, not only in terms of there was an opportunity for funding but also for them to be a part of it, and for them to be linking into their community as well.”

2.4.2 Key barriers to successful implementation

Complex process of implementing alleygates: the primary implementation challenges for this set of interventions related to alleygates (implemented by 31 of the 52 bid areas). The overall feedback was that they were complex and time consuming to implement.

For private alleygates (that is, bordering property not owned by the council), there were challenges identifying property owners, especially in areas with a high proportion of private landlords where some do not live in the area. Obtaining consent from landlords was a further difficulty, as all landlords must consent to the alleygate being installed.

“Alleygating is a very well proven technique to prevent crime, but it’s very hard – it’s very labour intensive, and it’s very expensive.”

Difficulties in partnership working: Although in many cases the PCC led most of the implementation, the local authority tended to conduct consultations. In some cases, PCCs found that the local authority prioritised other activities over the consultation work.

“The council had to do the consultations. We had to remind [the] council of their responsibilities. It was trying at times because we had to get our partners to really step up.”

Also, as different local authorities had different processes and requirements, areas that were implementing alleygates in multiple areas encountered different challenges in each area and could not adopt a uniform approach.

“If an alleygate and anti-climb device is over certain height, some local authorities need planning permission to put the device on, others don’t. So, we could not get planning permission across the board as planned.”

Resistance from community: some residents, particularly those with restricted mobility, had concerns about access to certain areas. Further consultation during implementation addressed these requests but resulted in delays.

“We spent an awful lot of time talking to people, reassuring them, offering them advice without committing ourselves unnecessarily. That’s both draining on the team that are doing it, but also very time consuming.”

Vandalism and damage to gates: as with CCTV, some areas experienced a backlash from crime groups and gates were damaged as a result.

“I think we’re going through a period of high anti-social behaviour and crime at the moment, and I think that’s what’s making it a target again. It’s a very easy target for people because it’s; so visual.”

2.5 Target hardening of homes

Target hardening interventions included security assessments for residential properties, primarily for social housing though also for private properties. Following assessment, security measures were installed such as locks, security lighting, alarms and video doorbells.

One of the more popular interventions amongst residents, implementation of home security measures gained momentum once the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions were lifted. Word of mouth played a key role in driving the success of the intervention, with people requesting interventions after their neighbours had received them.

The positive response from residents towards video doorbells also created opportunities for bid areas to engage residents with SSF1 and crime prevention more widely. Bid areas felt that target hardening initiatives increased security of the properties and reduced acquisitive crimes when residents were out of their homes.

“It aided both the security of the property in terms of the security lighting and reduced acquisitive crime for when people were out and about, in terms of bikes being locked up in a less secure area.”

“It helps reduce the fear of crime, improves safety a bit, and it just encouraged people to put their hand up and say I’ll have the security survey for free please.”

2.5.1 Key enablers of successful implementation

Positive response from residents and community: local implementation teams perceived that target hardening interventions proved to be very popular with residents, driving awareness of and positivity about the programme. Local authorities or housing providers that owned buildings were also pleased that their properties were being improved for free, which drove a high response rate for these measures. There was particularly strong interest in video doorbells, leading to residents reporting an increased feeling of home security.

“I think that’s [target hardening] probably what’s won over our community the most. They really couldn’t believe what we were giving to them.”

“We’ve had requests for interventions from the community far in excess of what we’d have been able to provide.”

“The video door promotion – bringing those in means that people are registering … We’re putting a £50 doorbell in and it’s enticing people to get that – ‘I’d like that’, ‘why not’, ‘it’s too good to be true’.”

Successfully prioritised vulnerable groups: teams reported making a concerted effort to prioritise their vulnerable residents first. They obtained lists from Victim Support, PCSOs and Housing Officers of vulnerable people to ensure they were included and prioritised. They felt that home security assessments, conducted as part of the delivery process, had also helped them to identify groups of vulnerable residents or those with specific needs who otherwise may have gone undetected. The process of door knocking, and home visits provided a way in to identify social care referrals and other issues.

“The knocking on doors enabled police/wardens to have a look in people’s houses, discuss issues, residents were pointing out other houses where there were issues with neighbours.”

“We said to the Home Office we would target harden. So, we could just go, and target harden, or we could go, and target harden and actually look at other things at the same time. It was an engagement tool for us as well.”

Case study 5 – Prioritising vulnerable groups

In one area, door knocking, and the Neighbourhood Watch scheme identified vulnerable participants who were struggling or lonely. As a result, the Neighbourhood Watch began building a loneliness campaign around these residents.

Because of SSF and working so closely with the Neighbourhood Watch, they have been able to develop greater insight into the housing stock and communities.

“You know the community, you know the population, you know the housing stock and who owns it – yeah we had a good overview of that.”

(North West England, Rural)

Innovative approaches in response to the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions (that could also shape future programmes): when faced with the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, some areas adopted different approaches to implement target hardening that worked particularly well. For example, one bid area resorted to remote home security assessments when they could not enter people’s homes. The remote assessments were so successful that the team is considering changing their ways of working in future.

“COVID presented us with an interesting challenge that then actually showed the worth of doing them [assessments] remotely, and actually how cautious I would have been around that at the start of the project, but actually we started to see quite significant efficiencies from it, and it got the homeowners quite involved and invested in the home security assessments.”

Partnership working to deliver added value: there were examples of positive partnership working where bid areas worked with other organisations, such as the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) or the fire services, to deliver target hardening interventions besides other services (outside the SSF1 programme’s scope) that were needed by residents. For example, home visits for target hardening in one area also included the offer of fire service safety checks, council advice on recycling, and (DWP) contact about benefits and employment opportunities. Another area reported working with third-sector partners, enabling the team to identify and refer vulnerable individuals who would not have been otherwise identified, such as, victims of domestic abuse.

2.5.2 Key barriers to successful implementation

Difficulty engaging specific groups: bid teams reported finding certain groups more difficult to engage with and these groups were also less likely to volunteer for their properties to be covered. These included:

- vulnerable groups (especially in more deprived areas) who had low levels of trust in authority figures or were wary of the legitimacy of the offer

- landlords who were less invested in securing the property

- residents who were concerned about the potential costs of video doorbells

- students, who were generally more difficult to engage

“To start with, people were slightly suspicious around why people were knocking on their door, offering them free things – that doesn’t happen in life does it?”

“When first sent out to landlords, only got very small response which was concerning – did better with engagement of housing team.”

Bid areas attempted to overcome residents’ suspicions by communicating through partners that had existing relationships with residents, for example, through a local synagogue. Other bid areas set up dedicated areas on websites and communicated about the project through social media.

Limited insight into housing stock: limited knowledge of the properties involved sometimes hindered implementing target hardening. Examples included not being aware that some buildings were listed, which added time and complexity into the process; or inadequate understanding of the quality of the housing stock, which resulted in additional work being required (such as, fitting new doors or windows) before implementing the interventions.

Lengthy and complex procurement processes: without pre-existing suppliers in place, some areas had to go through formal procurement processes, adding time and complexity to the process. Conversely, areas with pre-existing suppliers often felt restricted and unable to select an alternative supplier as the best fit for the programme. In some cases, management of multiple contractors also added to the administrative burden.

“Procurement was an absolute nightmare. It’s very difficult when trying to do things quickly.”

“All the security stuff needed to be fitted by somebody and we found ourselves in knots of [sic] the procurement rules … we didn’t have time to go out for quotes, so we were hunting around for framework elsewhere in the country to piggyback on.”

Need for education and behaviour change to support home security: some bid areas felt that without adequate initiatives to change behaviour, encouraging residents to always lock doors and windows, some interventions may have limited impact.

“Students take care of their room … but the front door not being secure doesn’t bother them. Most burglaries could be prevented by locking doors.”

Delivery staff not fully briefed: a few issues emerged that related to key information not being aligned across the teams involved in implementation. For example, in one area, staff going door-to-door mistakenly offered residents interventions that were not included in the programme, which later had to be withdrawn. In another area, different teams conducting assessments and installations disagreed about what home security works needed to be done, resulting in inconsistencies and difficulties in budgeting.

Understanding the requirements underpinning video doorbells: areas implementing video doorbells often discovered a lack of Wi-Fi in the targeted properties, meaning residents had to return the device. In these instances, devices were replaced with more basic house alarms; it highlighted the digital exclusion of some residents and the importance of understanding the minimum requirements that they could communicated more clearly up front.

Case study 6 – Understanding barriers to take-up

One area reported that SSF had given them greater insight into the challenges the local community was facing. Because of this, they had a greater understanding of why the offer of free target hardening may not be taken up. This insight had helped them to understand some of the barriers that they might face with implementing future programs.

“That’s what we’ve got to start understanding, is how other people live, what their challenges are, and that it might seem like here’s a great freebie, it will protect you, but those people are wary of those things for a lot of reasons.”

“I always think of the scenario, single mum, she’s at home with 3 kids, she’s really struggling to make ends meet, and she will be worried about the fact that she hasn’t got a carpet in that room because she can’t afford a carpet and she can’t afford to put the heating on … then somebody knocks on the door and says oh I want to offer you a light and all the rest of it, other than the fact she probably thinks I can’t afford that, do you really think she wants to let that person in to see the state of her house? Because she believes that person will tell Social Services.”

(North East England, Urban)

2.6 Community engagement

Most areas carried out some form of community engagement to consult on their priorities, particularly in relation to target hardening of homes and implementation of alleygates, but also for the wider SSF1 programme. Initiatives included home visits, door knocking, street surgeries, online meetings and pop-up awareness-building activities. Engagement took place largely with the help of partners, though in some cases, areas recruited specifically for this purpose.

Stakeholders felt that community engagement was critical to the success and sustainability of their programmes, and there were multiple success stories across bid areas. Positive feedback from the community informed bid areas that engagement had been successful, though areas felt that the COVID-19 pandemic limited their activities.

Case study 7 – Sustainable community engagement

One success story from a bid team related to a landscaping project. As a result of developing a shared garden, they have also created community cohesion. Now, the residents are watering the plants daily, ensuring the plants are maintained and taking ownership of it.

“They’ve started to take some ownership, and for me that’s about the sustainability of the project – whilst you can say what’s lettuce planting got to do with designing out burglary, it’s about the eyes and ears of the community, in the same way as Neighbourhood Watch, so it’s making that visible guardianship much more ever present across the estate.”

(South England, Urban)

Hopefully, encouraging neighbours out of their flats and talking to other neighbours will also enable them to report any criminal activity.

2.6.1 Key enablers of a successful implementation

Partnership working: bid areas leveraged a range of partners with existing links to the community who had in-depth local knowledge, credibility with residents and understanding of local crimes, including:

- local PCSOs, ASB teams, Community Safety Partnerships, Neighbourhood Watch

- parish councils

- food banks

- places of worship, such as churches/mosques/synagogues

- local student representatives (in areas with a high student population)

- National Farmers Union

- other groups or individuals already working on local community activities

“The impact [of parish council members] is positive in some villages because they’ve just done our job for us. They’ve put leaflets up everywhere, they’ve gotten [sic] the message out, they’ve held meetings in community halls, they’ve got WhatsApp messaging groups.”

Working through partners, areas felt, helped to include harder-to-reach residents who would be unlikely to engage directly with the police or local authority. One area used ‘community champions’, individuals who spread information via word of mouth. The ‘champions’ trained through Victim Support to ensure they were equipped with skills to engage with vulnerable residents. The team felt the champions were integral to the success of their programme and are keen to strengthen their role in future.