Review of Part R (physical infrastructure for electronic communications) and Part 9A of the Building Regulations

Published 7 May 2021

Applies to England

Current position of the Part 9A and Part R Regulation

Introduction

This document provides a high level overview of implementation of Part 9A and Part R of the Building Regulations in England in response to the EU Broadband Cost Reduction Directive issued in 2014. According to the amendment to the Building Regulations that introduced Part, it was stated that:

(1) Before the end of each review period the Secretary of State must—

(a) carry out a review of Part 9A and Part R of Schedule 1; and

(b) publish a report setting out the conclusions of the review.

(2) In carrying out the review the Secretary of State must have regard to how Article 8 (in-building physical infrastructure) of Directive 2014/61/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on measures to reduce the cost of deploying high-speed electronic communications networks(6) is implemented in other Member States of the European Union.

(3) The report must in particular—

(a) set out the objectives intended to be achieved by the regulatory provision in Part 9A and Part R of Schedule 1;

(b) assess the extent to which those objectives have been achieved;

(c) assess whether those objectives remain appropriate; and

(d) if those objectives remain appropriate, assess the extent to which they could be achieved in another way that imposes less onerous regulatory provision.

(4) In this regulation, “review period” means—

(a) the period of five years beginning on the 9th May 2016; and

(b) subject to paragraph (5), each successive period of five years.

(5) If a report under this regulation is published before the last day of the review period to which it relates, the next review period will begin with the day on which that report is published.”

This review examines the impact that the regulations have had, if they have met their initial objectives and whether the regulations are still required. The review also considers if the objectives can be achieved in a manner which imposes less onerous burdens on those that install the physical infrastructure needed for Superfast[footnote 1] broadband connectivity.

It is noted that this review does not intend to propose any changes to legislation or to propose any policy changes. Instead, it lays out the policy position of England towards the regulation of high-speed electronic communications, particularly for commercial and existing buildings. Changes to Part R will be subject to future consultation processes.

Context

Since the introduction of Part R in 2016, England has made significant progress in both mobile and fixed connectivity. Department for Digital, Culture Media & Sport’s (DCMS) Digital Strategy (March 2017) set out strategic proposals to improve broadband connectivity, and in December of that year the Government met the pre-existing Superfast Broadband Programme target to extend superfast coverage to 95% of English premises. The latest Ofcom Connected Nations report states that Superfast connectivity in England stands at 95% across all premises.[footnote 2] The independent broadband information site Think Broadband states that Superfast connectivity in England is now 97% as of April 2021.

Significant progress in realising government connectivity ambitions was made in 2019, with that year’s manifesto including a commitment to deliver nationwide coverage of gigabit-capable broadband as soon as possible. Therefore, the Government’s ambitions are now to rollout faster broadband connections than the superfast speeds set out in 2016’s Regulation.[footnote 3]

To accelerate this rollout, the Government has set a clear strategy to promote competition and commercial investment wherever possible, and to reduce barriers to rollout. There are now over 80 providers building gigabit-capable networks in the UK, with 39% of UK premises able to access gigabit broadband according to Think Broadband. The Government expects to hit 60% coverage by the end of this year.

To support gigabit rollout, the Government launched Project Gigabit on 19 March 2021, a £5 billion investment in gigabit-capable broadband towards hard to reach places that would otherwise miss out of this national upgrade.

DCMS also announced more money to connect schools, GP surgeries, libraries in hard to reach places - up to £110 million over the next three years - and up to £210 million for a new voucher from the Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme for hard to reach communities, that launched in April 2020.

Furthermore, the Government is continuing to remove barriers in order to make it easier for operators. As well as the £5 billion we are investing in hard to reach areas - so all parts of the UK will benefit from improved digital connectivity - we have recently introduced legislation that will make it easier for the firms to connect blocks of flats.

In addition, we are reforming the Streetworks regime to make broadband deployment easier, and, in order to update the requirements set out in Part R so that they match current Government ambitions, we will legislate to facilitate gigabit-capable connectivity in new build homes up to a cost cap.

Part R of the Building Regulations in England

The building regulations are a devolved matter, and the Secretary of State is obliged to review how Part R as it pertains to buildings in England every five years.

Requirement R(1) of the Building Regulations is accompanied by statutory guidance in Approved Document R (see the extract below, which sets out the requirement in question).

Part R Physical infrastructure for high-speed electronic communications networks

In-building physical infrastructure

R1

1. Building work must be carried out so as to ensure that the building is equipped with a high- speed-ready in-building physical infrastructure, up to a network termination point for high-speed electronic communications networks.

2. Where the work concerns a building containing more than one dwelling, the work must be carried out so as to ensure that the building is equipped in addition with a common access point for high-speed electronic communications networks.

Limits on application

1. Requirement R1 applies to building work that consists of– (a) the erection of a building; or (b) major renovation works to a building

Part 9A of the Building Regulations concerns Part R’s application, exemptions and definitions. For example, Part R applies to crown buildings, schools, and building work carried out by crown authorities, but does not apply to buildings occupied by the Ministry of Defence or armed forces, buildings that are too remote to justify equipping them with Superfast Broadband, or to certain buildings where complying with Part R would unacceptably alter their character or appearance.

Objectives of Part R and Part 9A

The objective of Part R of the Building Regulation was to transpose the Directive’s provisions into Building Regulations.

Part R applies to all new buildings and existing buildings that are subject to major renovation[footnote 4] works, in England, unless exempted. The list of exempted builds and works is found in section 44B of Part R.

Whilst the Secretary of State is obliged to review Part 9A and Part R of Schedule 1 every five years, as the UK’s relationship with the European Union currently stands, there is no obligation to transpose revisions to the 2014 Directive should they be made by the European Parliament in the future under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement 2020 (TCA).

How have EU member states and devolved nations implemented the requirement for in-building infrastructure

The requirements have been implemented in a variety of ways across member states.

- Portugal and Italy have introduced broadband-ready labels and Spain and Germany are considering following suit. In France there is a standard to indicate fibred zones (Article 8(3)).

- A report from the European Commission suggested that effective implementation of the provisions on in-building infrastructure appears to be linked to the definition of standards. This relates to setting out what is meant by high-speed-ready in-building infrastructure, and the associated access point, and mechanisms to monitor and enforce adherence to these standards.[footnote 5]

- For instance, in France, Portugal and Spain mandatory standards set out how the infrastructure must be installed and where the access point must be located.[footnote 6] Broadband-ready infrastructure has been relatively widely deployed in these countries, with the standards mentioned above contributing to high rates of Fibre To The Premises/Cabinet (FTTP/C) deployment in Portugal and Spain.

- A majority of stakeholders who responded to a European Commission consultation on the effectiveness of the directive considered broadband-ready labels a good way of supporting the deployment and take-up of high-speed networks. Such labels have been introduced in only a few EU countries so far.

- A Body for European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) noted in their opinion regarding a revision to the BRCD that EU nations like Poland and Austria were more likely to fall foul of Articles regarding access and availability of in-house physical infrastructure. This is because they did not change building regulations but rather passed Telecommunication Acts. This led many builders to miss these regulations and not install suitable in-house physical infrastructure.[footnote 7]

- A 2017 BEREC Report analysing the BCRD after 12 months found that Poland had 90 disputes regarding access to in-house physical infrastructure. Spain, Portugal, France and UK all recorded zero disputes in the 12-month period.[footnote 8]

In terms of the devolved administrations, Scotland, Wales and NI have also implemented the requirements of Article 8 via their Building Regulations. No devolved administration has to follow any outcome of the review of Part R of the Building Regulations in England.

The objectives of Article 8 of Directive 2014/61/EU (measures to reduce the cost of deploying high-speed electronic communications networks)

As noted above, the original objectives of Article 8 of Directive 2014/61/EU were essentially to:

Objective 1: Connect more premises to Superfast Broadband

Objective 2: Reduce the overall cost of installing Superfast Broadband[footnote 9]

The original impact assessment that accompanied the implementation of Part R of the Buildings Regulations in 2016 estimated that the requirement to provide in-building physical infrastructure (by 2016) in England could be achieved without imposing additional costs on the market in most cases. However, it was suggested that that homes in the very small self-build homes market would be most affected because these homeowners may be more likely to not choose to install the physical infrastructure needed for Superfast broadband.

Have these objectives been achieved?

Objective 1: Connecting more premises to Superfast (30Mbps+) Broadband

In terms of this objective, England had already made significant strides towards extending superfast broadband connectivity, so it is difficult to separate from these existing ambitions the effect of the 2014 Directive and its transposition.

Since 2012, the government has spent £2.6bn in public funding to subsidise the roll-out of Superfast broadband infrastructure in hard-to-reach areas. The Superfast Broadband programme was announced in 2010/11 in response to concerns that the commercial deployment of superfast broadband[footnote 10] would fail to reach many parts of the UK.

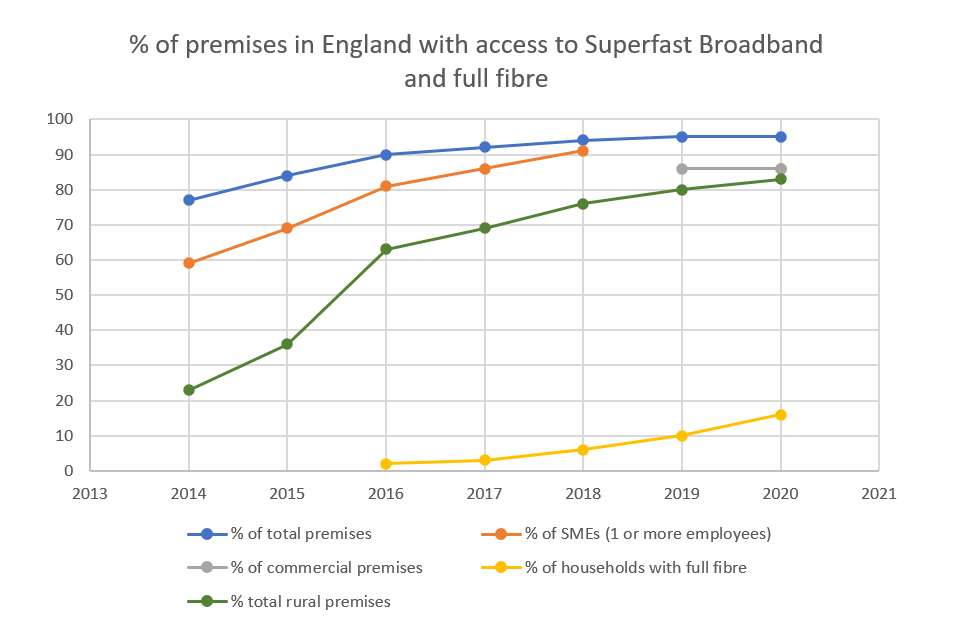

Source: Ofcom. Connected Nations Reports, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020.[footnote 11]

2019 and 2020 connectivity of small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) figures are for full commercial premises.

On the expectation that extension of superfast broadband coverage to these areas would produce economic, social and environmental benefits, the Government established the programme to fund further deployment. The scheme was initially backed by £530m of public funding, with the aim of extending superfast coverage to 90 percent of UK premises by early 2016. The programme was expanded in 2015, with a further £250m made available to extend coverage to 95 percent of premises by the end of 2017, a target that was met.

The latest data from Ofcom suggests that 95% of English premises have access to superfast broadband, with 5.3 million additional homes and businesses having access to superfast broadband directly attributable to the government’s investment in the Superfast Broadband Programme.

The majority of the early superfast programme rollout was Fibre to the Cabinet (FTTC) and then copper from the cabinet to the premises thereafter, in which case there was no requirement to enter buildings. However, since 2018, superfast contracts have switched (mainly) to fibre all the way to the premises (FTTP), so there is now a requirement to build to the premise, which may have an impact on the costs involved in comparison to FTTC.

In 2019 the Government outlined its ambition to roll out gigabit-capable broadband infrastructure (direct to premises) to the whole of the UK as quickly as possible. Whilst it may not always be FTTP - gigabit-capable technology is now the requirement, with the specific method not prescribed - this ambition will require the final connection to be made at the building itself.

Therefore, the rise in proportion of total premises that are connected to Superfast Broadband cannot solely be attributed to the Directive’s requirement for in-building physical infrastructure in premises. While it will have contributed to connectivity, this has been greatly increased by DCMS’ Superfast Broadband Programme and, when FTTP/gigabit-capable solutions were introduced more widely after 2017, through the Local Full Fibre Networks and Rural Gigabit Connectivity programmes. These programmes helped stimulate commercial network build where full fibre in England was less than 3% coverage. FTTP coverage is now more than 21%, with gigabit-capable coverage (whether through FTTP or other means) at 39.4% (April 2021) according to Think Broadband.

There was a significant rise in the proportion of SMEs with access to Superfast Broadband from 2015 / 2016, which suggests a possible impact of the introduction of Part R of the Building Regulations.

This is further highlighted by distinct increases in the Superfast connectivity of rural areas and the rollout of FTTP across England which has been increasing exponentially since 2016. This suggests that Part R, which was published in 2016 and came into force in January 2017 has had a role in these significant uplifts. Network Operators have highlighted that the job of installing 30Mbps broadband has been made much easier with the in-house physical infrastructure built in as part of the build plan. This is highlighted in the sharp uptake in full fibre and rural Superfast broadband that might have been slower to roll-out post-2016 without the Part R requirement.

Engagement with builders has shown that the regulation has not had a significant impact on developer costs with rebates being paid by fibre network operators being cited. They do, however, mention that there could be more of an impact on small developers with fewer buildings per site who may have to pay more money for installing the necessary physical infrastructure. This may have more of an impact on rural builds, so it is important to maintain a minimum standard in the Building Regulations. Furthermore, whilst building groups maintain that they will endeavour to provide FTTP for new homes, that guarantee is not in place for major renovations and commercial buildings and it will be important to maintain high standards by keeping this regulation in place to ensure existing buildings are connected to Superfast or better broadband as soon as possible.

Network Operators have indicated that developers do not always supply adequate access to infrastructure in multi-dwelling buildings and this is sometimes not fully enforced by building control bodies. They have also highlighted that access to existing cables can be difficult when the regulations are not fully implemented and enforced. This is only the view of some network operators and most responses noted no issues with adherence to the regulations. Nonetheless, it highlights the importance of accessible broadband infrastructure and the need for regulations to ensure as many buildings as possible have adequate connectivity.

It is difficult to assess any single factor when reviewing the significant uplift in England’s Superfast broadband coverage due to the different programmes implemented by the UK Government. However, feedback from industry has highlighted that access to in-house physical infrastructure put in place due to the requirements in Part R has made the process of increasing Superfast connectivity in England easier. Therefore, it is unquestionably the case that superfast and faster connectivity in England has improved since the implementation of the Directive in 2016.

Objective 2: Reducing the cost of installing Superfast Broadband

The Superfast Broadband Programme targeted areas of the UK where investments in superfast broadband infrastructure would not generate a rate of return that exceeds the cost of capital for private companies, leaving those areas at risk of being excluded from superfast broadband coverage (producing a ‘digital divide’).

The programme provided a significant incentive effect to network providers to build in these areas by providing the minimum subsidy that would be required to make these investments commercially viable for the private sector (i.e. the subsidy that would make their rate of return equal the cost of building the network). The programme also utilised a clawback mechanism which recouped public funds when commercial returns of areas were higher than anticipated.

Network Operators have indicated that the process of providing the in-house physical infrastructure in the initial build has reduced costs as fewer properties need to have a costly fitting of access and termination points after the fact.

Network Operators have also provided a mechanism to reduce the contributions to laying Superfast infrastructures for sites with multiple buildings which has helped reduced costs being passed on to developers and then to home buyers. These lower rates don’t apply to smaller sites so costs to connect rural builds to Superfast broadband might be higher. This means that regulations should stay in place to ensure areas are connected to high-speed connectivity regardless of location.

Are these objectives still appropriate?

In terms of connectivity, the pace of technological change and rollout has been high. As noted, the UK Government’s ambition has expanded to plan for faster broadband speeds and greater levels of digital inclusion, with the ambition now to provide nationwide coverage of gigabit-capable infrastructure by 2025.

In terms of reducing the cost of installing broadband, this continues to be a long-term objective. By investing now in future-proofed infrastructure to enable gigabit-capable connectivity, this will reduce costs in the long-term, as less retrofitting and street works will be required to put in place upgraded infrastructure. Developers are not having difficulties in meeting the requirement to install in-building physical infrastructure for Superfast Broadband, and we expect that this will continue to be the case with infrastructure for gigabit-capable broadband. Information from the Local Authority Building Control (LABC) has stated that they have not encountered any compliance issues for flats and homes to comply with this regulation. A minority of network operators have stated issues with accessing some of the infrastructure, particularly in high-rise buildings but overall, also have not noted many cases of non-compliance with the policy.

As part of its ambitions for gigabit-capable rollout, the Government has carried out a public consultation in 2018 and announced in 2020 that it will:

- Amend the Building Regulations 2010 to require all new build domestic developments to have the physical infrastructure to support gigabit-capable connections.

- Amend the Building Regulations 2010 to create a requirement on housing developers to work with network operators so that gigabit broadband is installed in new build domestic developments, up to a cost cap.

- Publish supporting statutory guidance (Approved Documents) as soon as possible.

- Continue to work with network operators to ensure they are connecting as many new build domestic developments as possible and at the lowest possible price.

- Work with housing developers and their representative bodies to raise awareness of these new requirements.

The update will differ from the existing Part R requirement in that for new-build domestic dwellings there will be a requirement to draw up a connectivity plan for in the dwelling as well as the physical infrastructure that goes with it. For major renovations and non-domestic buildings, Part R will be retained in its current form.

In conclusion, while there have been changes in technology and government ambitions, the principles behind the objectives in question still stand: the Government still aims to maximise the rollout of fit-for-purpose broadband, and in the long term, to reduce the costs involved in doing so.

How far could these objectives be achieved in a manner that imposes less onerous regulatory provisions?

Option 1: Retain requirements for non-domestic buildings and for major renovations

As noted, requirements for new residential properties are being updated to gigabit requirements following public consultation and calls for evidence. Retaining the remaining Part R requirements would continue to ensure that non-residential buildings and renovations would as a minimum have the internal infrastructure to support Superfast requirements.

Option 2: Remove requirement from Part R of the Building Regulations for new commercial buildings and major renovation works (including for multi-dwelling buildings)

In the absence of an evidence base demonstrating the need to remove requirements, this would run counter to the Government’s intentions to improve connectivity. The market would likely continue to provide in-building physical infrastructure for non-domestic buildings and major renovations. There would, however, be familiarisation costs in removing the regulatory provision and a very small number of buildings may be affected, particularly in rural/isolated areas.

Option 3: Introduce non-regulatory policy to improve provision of in-building physical infrastructure for broadband from the Building Regulations

The original 2015 consultation on Part R contained suggestions from a minority of stakeholders that the objectives could be achieved through planning conditions and/or mirroring the processes in place from network operators for installing broadband services. There has also been suggestion of introducing “broadband-ready” labels to incentivise builders to install the appropriate infrastructure. This, however, does not harmonise with existing DCMS policy and could also leave a potential gap where existing domestic buildings and new non-domestic buildings may not have the infrastructure to connect to Superfast or faster broadband.

Preferred option:

Option 1:

Part R retained in its current form (save for new residential buildings). Government will consider how future work should be taken forward in relation to the remaining building types within the scope of Part R. Until an evidence base is available as to whether to remove or update the residual requirements, the familiarisation cost of removing the regulatory provision would likely outweigh the deregulation benefits of removing it and potentially lead to some buildings being built without Superfast connectivity. Evidence from the Ofcom Connected Nations report has shown a notable increase in the uptake of Superfast connectivity since Part R was introduced, especially in rural residences. Anecdotal evidence from EU member states has highlighted that not using building regulations led to a lower rate of in-house physical infrastructure being built.

-

Defined as equal to or greater than 30mbps ↩

-

2020 Connected Nations Report, Ofcom ↩

-

The UK considers Superfast Broadband to be speeds of 30 mbps; Gigabit-capable broadband is defined as ‘an optical fibre and other cabling or wiring that is capable of bursts of 1000mpbs, capable of reaching sustained periods of gigabit speeds if such a service is provided by an Internet Service Provider’. ↩

-

Major renovation works defined in the Merged Approved Documents as: “Works at the end-user’s location encompassing structural modifications of the entire in-building physical infrastructure, or of a significant part of it.” ↩

-

Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the implementation of Directive 2014/61/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on measures to reduce the cost of deploying high-speed electronic communications networks. ↩

-

Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on the implementation of Directive 2014/61/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 15 May 2014 on measures to reduce the cost of deploying high-speed electronic communications networks. ↩

-

BEREC Opinion on the Revision of the Broadband Cost Reduction Directive: 11 March 2021 ↩

-

Implementation of the Broadband Cost Reduction Directive: 7 December 2017 ↩

-

Commission uses terminology ‘high-speed broadband’ to describe speeds of over 30 Mbps. The UK Government terms this Superfast Broadband. ↩

-

Then defined as download speeds of at least 24 megabits per second. ↩

-

Ofcom Connected Nations Reports: Ofcom changed their metrics, and the data available is for all commercial properties and not just SMEs. ↩