Independent Review of Governance and Accountability in the Civil Service: The Rt Hon Lord Maude of Horsham (HTML)

Updated 13 November 2023

Foreword and Acknowledgements

1.1 I was appointed to conduct this review, of Civil Service governance and accountability, in July 2022, pursuant to the commitment in the Declaration on Government Reform of June 2021. My broad Terms of Reference for the review are set out in Annex 1.

1.2 The initial expectation was that the review would take no more than a few months. That it has taken a full year reflects the breadth and complexity of the issues involved, and the time needed to uncover the current arrangements for governance and accountability, both in theory and in practice. Some of the findings overturn assumptions casually made by many, including myself, and so it has been necessary to check and recheck to be sure that the shape that has emerged, so far as is possible, is reasonably accurate.

1.3 The Review has been informed by numerous interviews, conversations and submissions. I have spoken with Civil Service leaders both past and present; serving and former ministers from all major UK parties, including Prime Ministers; numerous civil servants both former and current; and a multitude of students of and commentators on the Civil Service. This has created a strong factual basis, provided many insights and ideas, and enabled me to test findings and ideas extensively. I am enormously grateful to them all for speaking openly and frankly.

1.4 In particular, I would like to thank: Sapana Agrawal, Sir Michael Barber, Dame Kate Bingham, Lord Birt, Simon Case, Rt Hon Sir Tony Blair, Sir Alex Chisholm, Rt Hon Thérèse Coffey MP, Janette Durbin, Tamara Finkelstein, David Foley, Dr Laura Gilbert, Catherine Haddon, Rt Hon John Healey MP, Rt Hon the Lord Herbert of South Downs, Rt Hon Dame Margaret Hodge MP, Dame Patricia Hodgson, Michael Jary, Sir Bernard Jenkin MP, Lord Johnson of Lainston, Nick Joicey, the late Lord Kerslake, Sir John Kingman, Tony van Kralingen, Dame Emily Lawson, Megan Lee Devlin, Sir John Manzoni, Rt Hon the Lord O’Donnell, Rt Hon the Lord Pickles, Rt Hon Jeremy Quin MP, Rt Hon Angela Rayner MP, Tom Read, Gareth Rhys Williams, Sir Olly Robbins, Antonia Romeo, Fiona Ryland, Rt Hon the Lord Sainsbury of Turville, Rt Hon the Lord Sedwill, Nick Smallwood, Rt Hon the Baroness Stuart of Edgbaston, Mark Sweeney, Simon Tse, Sir Patrick Vallance, Sir Chris Wormald, and William Wragg MP.

1.5 The topic of governance has been much studied in recent years by a variety of think tanks and other bodies. I mention especially the Institute for Government, which has over the last few years published a number of penetrating and well-informed studies making recommendations that bear directly on this review. The Commission on Smart Government has also been an invaluable source of information, ideas and insights.

1.6 No one can write about the Civil Service without owing a huge debt to Lord Hennessy’s magisterial “Whitehall”. I am enormously grateful to him for this, for many conversations over the years, and for his permission to quote from the book.

1.7 Finally, my thanks to the Review Secretariat, ably led by Sharmin Joarder and supported by Anita Bhalla and David Kirkham. They have undertaken diligent research, sourced and checked numerous facts and documents, reported back from a great many seminars and other events relevant to the Review, and arranged a vast array of meetings and interviews. I could not have completed this Review without them.

Executive Summary

Findings

2.1 The arrangements for governance and accountability of the Civil Service are unclear, opaque and incomplete:

- The power to manage the Civil Service is by statute vested in the Prime Minister as Minister for the Civil Service. However there is no overall scheme of delegation for how this power is to be exercised in practice, whether by ministers and/or by civil servants.

- Other than the accountability of civil servants to ministers, there is little external scrutiny of the Civil Service as an institution. The powers of the Civil Service Commission are limited to oversight of external recruitment to the Service, and in any event the Commission operationally is heavily dependent on the Civil Service. Its independence is accordingly truncated.

- The demands placed upon the centre of government - Prime Minister’s Office, Cabinet Office and HM Treasury - have expanded massively in the last 100 years, yet its basic shape and division of functions has remained broadly unchanged. The centre is now unwieldy, with confusion about where responsibilities lie and a lack of clear lines of accountability. Other jurisdictions with similar systems provide signposts to improved arrangements.

- The nearly complete accountability that ministers have for their departments’ activities is out of alignment with their assumed authority to direct resources.

Effects

2.2 The effects of this are:

- There has been a failure over decades to implement or sustain agreed and uncontroversial reforms and improvements - the “stewardship obligation”. Failings identified by the Fulton Committee in 1968, for example the dominance of “generalists”, “churn” whereby officials move from post to post in an apparently unplanned and uncontrolled manner, and an excessively closed culture and lack of interchange with external sectors, all constantly recur in reviews of and commentaries on the Civil Service.

- The public interest in having a permanent politically impartial Civil Service, able to serve any democratically-elected government effectively and to give ministers well-informed and robust advice, is not well assured due to the absence of systematic external scrutiny.

- There is an avoidable level of tension and frustration between ministers and civil servants.

Principal recommendations

2.3 My principal recommendations therefore are:

1. There should be a comprehensive and transparent scheme of delegation of the Prime Minister’s statutory power to manage the Civil Service.

2. The role of Head of the Civil Service (HoCS) should be dedicated and full time, with a mandate from the Prime Minister to drive through an agreed programme of Civil Service reforms and improvements, supported by a single Civil Service Board with transparent membership and mandate. HoCS should be an individual with a proven capacity for system leadership and experience in driving demanding change management programmes across a large and complex organisation.

3. The role of the Civil Service Commission should be expanded to include:

a. Holding HoCS to account for the implementation of an agreed programme of Civil Service reforms and improvements; and reporting annually to Parliament on progress.

b. Overseeing internal Civil Service appointments to ensure that they are made on merit.

The First Civil Service Commissioner should be a near full-time appointment, paid at the same rate as the leaders of major regulators; the Commission should always include a former minister from each of the two major UK parties; and the Commission staff should be independent of the Civil Service and include at most a small minority of civil servants.

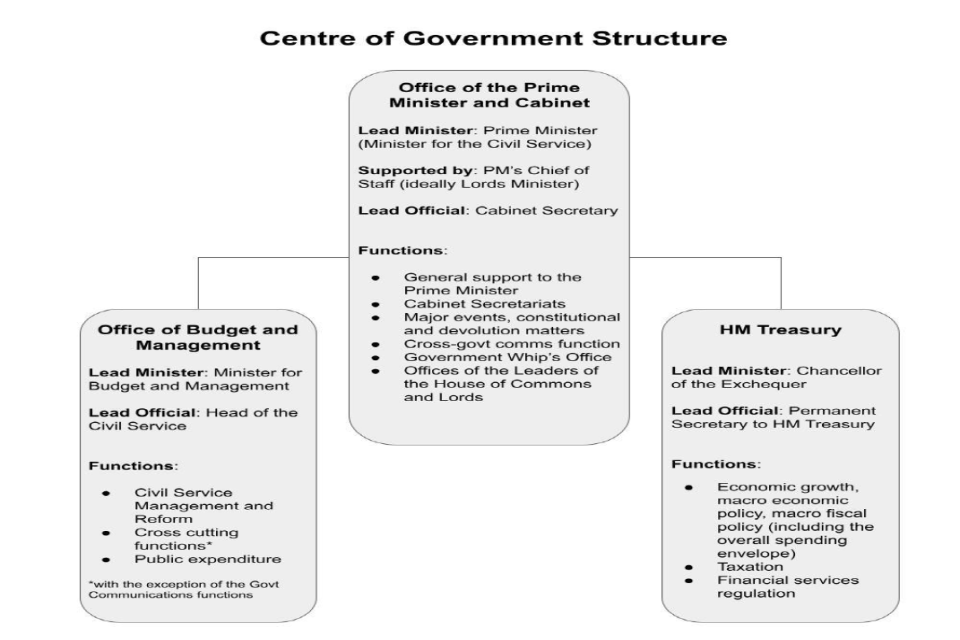

4. The centre of government should be reorganised to create: an Office of Prime Minister and Cabinet, which would be the strategic centre; an Office of Budget and Management (OBM), which by bringing together the leadership of the cross-cutting implementation functions with the management of public expenditure would create strong real time accountability for the spending of public money; and HM Treasury should retain responsibility for economic and fiscal policy, including the overall expenditure envelope, taxation and financial services regulation. This arrangement would align the UK much more closely with other governments with Westminster-style parliamentary democracies, such as Australia, Canada, Ireland and New Zealand.

5. The arrangements for the appointment of civil servants should be revisited to allow ministers a greater role in some appointments while strengthening the public interest in maintaining a permanent politically impartial service able to give robust and objective advice to ministers.

Subsidiary recommendations

2.4. Further, I additionally recommend that:

- Departmental boards should be retained and their role strengthened, especially in relation to transparency, data and management information.

- The customs surrounding collective decision-making, including Cabinet Committees and Sub-Committees, are archaic, and should be modernised to narrow the gap between “crisis mode” and business as usual.

- A specific review should be commissioned into the governance of and accountability for the implementation of cross-departmental programmes, with no restrictions on scope. In particular the review must be able to consider changes to the role of departmental accounting officers, which has been explicitly and unaccountably excluded from the remit of the current review.

- More care should be taken with the preparation, selection and appointment of ministers and Special Advisers, with a particular focus on training.

- The landscape of Arm’s Length Bodies (ALBs) is confused and confusing. Ministers often have limited information about the ALBs that they have responsibility for, and little visibility into their operation. The sponsorship arrangements in departments vary greatly, and too often suffer from a lack of senior attention. There should be a sustained programme to map the landscape of ALBs accurately and on a consistent basis; categorise them on the basis of the appropriate governance and accountability arrangements (the “length of the arm”); and introduce a consistent approach across government for reporting in to the sponsoring department and the way in which appointments to their boards are made.

Introduction

3.1 The Government made a commitment to review the Civil Service’s Governance and Accountability in the 2021 Declaration on Government Reform, and I was asked to undertake this review. The Government’s commitment is very welcome. It is in the interest of everyone in the country, not least civil servants themselves, that governance and accountability are arranged in a way that will enable the British Civil Service once again to be “the best Civil Service in the world”.

3.2 Six initial points:

- I do not attempt here to set out a plan for Civil Service Reform. That is well-trodden ground. However, in order to illustrate the need for changes in governance and accountability it has been necessary to describe some of the substantive critiques of the Service that have consistently been made over the decades by successive reviewers, commentators, governments, and former officials and ministers. Any future governance and accountability arrangements should meet the test of enabling the implementation of the agreed reforms.

- Second, I am conscious that some of what I say sounds critical of the Civil Service. During my many years in Government as a Minister and as an external adviser, I have been supported by many highly talented and capable civil servants. The Civil Service as an institution needs to be arranged and managed in such a way that great civil servants can deliver the outstanding public service that is what attracted them in the first place. My criticism is of the Civil Service as an institution, not of civil servants. Indeed, I have found that much of the strongest criticism of the institution comes from civil servants themselves.[footnote 1]

- Third, as the Declaration on Government Reform set out, how Ministers are prepared for high office, and the way in which they are appointed and operate, also needs substantial improvement. It is little use complaining about lack of authority and the difficulty of holding officials to account, if ministers do not know how to exercise the authority they have, or how to hold others accountable. I make some observations and recommendations in relation to ministers and Special Advisers.

- Fourth, I have sought to avoid recommendations that either require primary legislation or challenge established constitutional norms. My focus has been on practical changes that can be set in train quickly. Some recommendations will doubtless be contested. But all are capable of being implemented at pace within the existing legislative framework.

- Fifth, in line with my Terms of Reference, which exclude consideration of “any issues relating to…the public expenditure accountability framework or governance processes…”, my recommendations leave this framework and these processes untouched. These are stated to be “the responsibility of the Chancellor of the Exchequer and continue to be reviewed and updated as required through existing processes”. I merely comment on the oddity of an approach which ordains that for just one government institution the only body deemed fit to review its governance of and accountability for something so central as public expenditure is that institution itself.

In considering the current shape of the centre of government, I do however make a recommendation on where these “governance processes” should be located.

- Sixth, this review was commissioned by, and reports to, the current government. It is however also addressed to the wider community of those not in government at present but who may aspire to office in the future. They have an interest in governance and accountability arrangements that enable the Civil Service to operate at the highest peak of effectiveness and efficiency, and to be capable of the continuous improvement that all great organisations should pursue.

3.3 The central principle of this review is that good governance requires authority and accountability to be aligned: that those charged with responsibilities should have sufficient authority to be able to discharge those responsibilities; and have a clear line of accountability for whether and how they are discharging them. I have framed my recommendations to reflect this principle.

3.4 The review proceeds on the basis that the UK’s current system of a permanent and politically impartial Civil Service will be maintained. For around 150 years there has been a broad consensus that the UK is best served by a permanent Civil Service that is politically impartial, in the sense of being capable of serving governments of any political persuasion with the same high level of capacity and commitment.

3.5 However, some dissent from this consensus. They hanker after something closer to the US system, where the top echelons of appointments in the public service are in the gift of the incoming administration. They argue that only when the senior managers are deeply immersed in, and committed to, the government’s policy agenda will it be possible to drive through policy reform with real effectiveness. In support of this, they argue that it creates crisp accountability - for those making these appointments authority and accountability are precisely aligned.

3.6 I have concluded that these advantages are outweighed by the disadvantages of delay and discontinuity that are evident in the US system.

3.7 The question then poses itself: are the current arrangements for the scrutiny of the Civil Service fit for purpose? It is hard to escape the conclusion that - almost alone among state institutions – there is no organised scrutiny of the way the Civil Service is managed.

3.8 The Civil Service is a people organisation and the most important task of its leadership is the appointment and management of its people. The most significant of the Civil Service reforms advocated over the decades are ultimately about people and the way in which they are selected, appointed and managed. Measures to address the dominance of generalists, churn, imperviousness - all these eventually come down to the appointment and management of people. The organisational health of the Civil Service is overwhelmingly dependent on its people: who they are, and how they are appointed and managed.

3.9 The Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 (CRAG) vests the power to “manage” the Civil Service in the Minister for the Civil Service – in practice, always the Prime Minister of the day. It is obvious that no Prime Minister can expect to exercise this power personally - for nearly all purposes that power would be expected to be delegated. However, it has been exceptionally difficult to piece together how (and in many cases whether) such formal delegation has occurred, and through what instruments of delegation. No comprehensive scheme exists, and the picture can only be loosely sketched out by examining a variety of documents - in particular letters delegating powers directly to ministers (never made public or revealed to ministers themselves) and the published Civil Service Management Code (CSMC). There are inconsistencies and gaps in the picture, described in Annex 5, and it is essential that a single comprehensive scheme of delegation should emerge from the consideration of this review.

3.10 However, the power to manage the (internal) appointment, promotion and lateral moves of civil servants has been left, in ways that are mostly unseen and certainly unregulated, to civil servants themselves. There is nothing in law that requires this power to be vested only with civil servants, and there are no formal and explicit delegation instruments to allow it (the Civil Service Management Code simply assumes it).

3.11 This essential management activity is carried out behind a veil which is hard for anyone outside the Civil Service to penetrate. Yes, the Civil Service Commission (CSC) has a statutory duty to oversee appointments into the Civil Service, but no power to oversee or investigate internal moves and promotions. Furthermore, the CSC is set up in such a way that its independence from the Civil Service hierarchy is limited. It is viewed as a Cabinet Office “arm’s length body”; but its budget is set by the Cabinet Office; its chief executive is a career civil servant line managed by the head of propriety and ethics; its staff are all civil servants; and its last two First Commissioners before the current incumbent were both former Civil Service permanent secretaries. It has historically seen its role as the protector of the Civil Service, guarding its perimeter, not as its scrutineer.

3.12 It is especially hard for ministers to penetrate this veil. Of course, ministers have little bandwidth to be involved personally, but most would value more visibility into how these decisions are made. Often they do not even know that changes are being made. Ministers’ sole direct appointees – the handful of Special Advisers – are denied any direct line of sight into the appointment process, although nothing in the law prevents this. Any attempt for ministers or their direct appointees to be present – again, even as passive observers – in any structure connected at all with the leadership and management of the Civil Service have consistently failed. These structures include the Civil Service Board, the Senior Leadership Committee and “Wednesday Morning Colleagues”- the weekly meeting chaired by the Cabinet Secretary and attended by Permanent Secretaries. It is notable that the CSMC places a responsibility on ministers to ensure that the conditions set out in the Code for lateral moves and promotions are being met, although it is highly unlikely that any minister has ever been told this.

3.13 There are good arguments for limiting the involvement of ministers and their representatives in the appointment of officials. The first is the need to preserve impartiality and continuity[footnote 2]. If ministers had unfettered power to impose their own choices, there is a danger that the Civil Service could too easily become so partisan in support of the incumbent government that its ability to effectively serve an incoming government of a different complexion would be impaired. This is a genuine concern, and any changes must provide convincing safeguards against this (see the chapter on Appointment of Civil Servants).

3.14 There is a second argument, rarely advanced in public, and of which we are only occasionally vouchsafed a glimpse. This argument runs as follows:

- ministers are transitory;

- they are often appointed for reasons unrelated to their skills or abilities;

- because of their need to secure public support and votes, they will often be tempted to make rash and ill thought out decisions, which will subsequently need to be changed, and perhaps reversed, by another government.

3.15 The existence of a permanent Civil Service, it can be argued, with its composition safe from the interference of ministers, is an important element in the “checks and balances” that protect the national interest from being damaged. Allowing ministers too much ability to impose their own chosen people into Civil Service posts, it is said, would weaken these checks and balances and thereby imperil the national interest.

3.16 This argument is rarely advanced openly and publicly. It lies behind the sense that the there is a core of the Civil Service with “administrative skills”, the “profession” described elegantly by Sir Edward Bridges in his 1952 Rede Lecture, something of a closed caste with its own customs and mystique, which outsiders, whether ministers or those brought in from outside, must not be allowed to imperil. These are the “generalists”, whose dominance of the Civil Service has consistently attracted criticism going back to the Fulton Report of 1968 and indeed beyond.

3.17 The shape of this argument has sometimes fleetingly become visible through the veil. A document created by consultants in 2008 at the direction of the then leadership of the Civil Service identified among the necessary qualities of candidates to be permanent secretary “knowing when to ‘serve’ the political agenda and manage ministers’ expectations versus leading their department” and “tolerating irrational political demands”. This was an uncharacteristically explicit statement that officials have permission - and sometimes an obligation - to ignore what ministers have instructed.

3.18 There is an obvious tension between this proposition and the obligation to respect the democratic mandate that ministers carry, so it is understandable that the argument is seldom explicitly made. This is a pity, as it carries some weight, and deserves to be clearly articulated and openly debated. The danger with a proposition which exists only in the shadows is that it can too easily be perverted to improper ends. It is too easy to suggest that the unwise decision of a minister who does not command respect or who is believed to have a short tenure can be ignored because to implement it would be “against the national interest”. It is too easy for the belief that the preservation of the permanent Civil Service is essential for the national interest to slide into passive or indeed active resistance to attempts at Civil Service reform - especially to reforms that would make it more open to new blood and different experiences.

3.19 The existence of a robust permanent Civil Service, with sufficient independence from the government of the day to enable officials to give honest, questioning and challenging advice to ministers, is genuinely an important safeguard of the national interest. The ability and willingness of the senior civil servant who is the accounting officer to call out a decision that improperly or unwisely ignores that advice by requiring a written ministerial direction is the ultimate safeguard.

3.20 So who should be responsible for ensuring that the Civil Service has these qualities? By definition it cannot be ministers, and for the reasons set out above the CSC is currently neither empowered nor equipped for it. The unspoken assumption has really been that these institutional qualities of permanence and resilience in the service of the national interest are so rare and precious that their maintenance can only be safely entrusted to the institution itself. This has created a sense that the Civil Service has had some of the characteristics of a self-perpetuating oligarchy with a built-in resistance to change[footnote 3].

3.21 This is no longer sustainable in a world that expects high levels of transparency and accountability. The arrangements for the governance and accountability of the Civil Service have been shrouded in layers of obscurity, ambiguity and unwritten assumption. The recommendations contained in this report are intended to put in place arrangements that are clear and unambiguous. Some may be uncomfortable for ministers; others for civil servants. But change is long overdue, and now is the time to embrace it.

3.22 My report is divided into seven chapters:

- The Stewardship Obligation: In my reading of previous reviews and other commentary on the Civil Service, I have been struck by the number of critiques that constantly recur over the decades. These critiques are generally uncontested and uncontroversial. Yet too often the changes and reforms needed to remedy these failings are not attempted, or if attempted, are abandoned before completion, or if completed regress after those implementing them move on. Remedying these failings requires systemic change, over a timescale that transcends the timespan of any individual administration. This requires a distinction to be made between the business of the government of the day on one hand and the “stewardship obligation” on the other. It is impossible not to conclude that the current arrangements for governance and accountability are seriously inadequate, especially for the discharge of the stewardship obligation. There is no individual - or body - with the authority to drive reform through the whole Service; and even if there were, the current accountability arrangements for the implementation of reform are gravely deficient.[footnote 4] Annexes 3 and 4 illustrate the need for change.

- The Centre of Government: With the introduction of the functional model, where the cross-cutting functions - commercial procurement, digital, financial management, etc - are strongly led from the centre, the role of the Cabinet Office has burgeoned in a way never foreseen, and which has led to blurred responsibilities and extremely confused lines of accountability. Furthermore, the structure of the centre of government and the relationships between its components- PM’s Office, HM Treasury and Cabinet Office - are now way out of line with other similar governments. Bringing the UK closer into line with others will simplify and clarify governance and accountability.

- Appointment of Civil Servants: While ministers are accountable for all that occurs within their department, their authority over the disposition of human resources - civil servants - in practice is severely truncated. Such powers are vested by statute in the Minister for the Civil Service - the Prime Minister. This chapter reviews how these powers are exercised and whether changes can be made that protect and enhance the principle of a permanent impartial Civil Service, and which help to reinstate the benefits of continuity.

- Accountability in Departments: This chapter covers the role of departmental boards, transparency, data and management information.

- Collective Decisions and Cross-Departmental Programmes: This chapter examines the processes by which ministerial decisions are informed, recorded, transmitted and implemented. I examine whether there can be greater accountability for the quality and accuracy of civil servants’ advice to ministers; and whether changes can be made to the operation of cabinet and cabinet committees to provide for greater accountability for the implementation of collective decisions.

- Ministers and Special Advisers: This chapter contains some reflections on the preparation, appointment, training and accountability of ministers and Special Advisers.

- Arm’s Length Bodies (ALBs): There are hundreds of ALBs of widely differing types that can affect the life of the nation and indeed directly impact the lives of individual citizens. As this chapter shows, there is little consistency in the way government departments delegate their functions to public bodies. I offer some reflections and suggest some general principles on how accountability for the operation of ALBs might be assessed and improved.

3.23 Finally, a word on what we mean by governance and accountability. Governance is defined variously as “the exercise of authority or control”; “a method or system of government or management”; “the action, manner or power of governing”. Accountability is clearer: it is essentially how people and organisations are to be held to account for their actions and results.

3.24 These are well used and familiar words. In the government context they have tended to be used in a limiting sense. So governance tends to be spoken of in terms of setting boundaries to power, and accountability in terms of holding people and organisations to account when things go wrong. The British constitution famously depends upon “checks and balances” and I do not in any sense downplay the importance of this more negative lens on governance and accountability. It is clearly important to have governance and accountability arrangements that reduce the likelihood of “bad things” being done.

3.25 However, governance and accountability arrangements also need to enable “good things” to be done and positive decisions to be implemented effectively. My focus in this review is unapologetically less on how to prevent things getting worse than on how to enable things to get better and support the British Civil Service once again to be “the best Civil Service in the world.”

The Stewardship Obligation

“…there is no…controlling body in the Civil Service…which today secures the efficient control of the undertaking.”

A Reform for the Civil Service (1921)

We have found no instance where reform has run ahead too rapidly

The Fulton Committee (1968)

Background

4.1 As outlined above, I do not recommend moving away from the long-established system of a permanent politically impartial Civil Service. The current system can be made to work effectively with some changes in governance that will improve the accountability of the permanent Civil Service for its discharge of the business of the government of the day. In the chapters on The Centre of Government, Appointment of Civil Servants, and Accountability in Departments, I make recommendations to effect these changes.

4.2 However, “permanence” confers a responsibility on the leadership of the Service to look beyond the time horizon of the government of the day; of any single Prime Minister or government. This is the “stewardship obligation” - the obligation to see through to completion reforms to the Civil Service that are uncontroversial. These reforms are required to drive continuous improvement and to maximise organisational health and effectiveness.

4.3 In previous reviews and other commentary on the Civil Service, numerous critiques constantly recur over the decades, generally uncontested and uncontroversial. The Institute for Government has helpfully documented some of these.[footnote 5] These include:

- Imperviousness and a closed culture - the low value attached to experience from outside the Service;

- Excessive reliance on “generalists” who dominate the Whitehall cadre of policy officials;

- Churn - the frequent and unplanned movement of oicials from post to post, without regard to business need, at the expense of continuity and of developing and maintaining specialist knowledge and expertise;

- The poor quality and use of data and management information;

- The gap between policy and implementation;

- The disparity of esteem between policy generalists (white collar) on the one hand and those charged with implementation or with specialist and technical expertise (blue collar) on the other;

- Innovation aversion - a culture that discourages innovation for fear of failure; and

- Poor performance management.

4.4 Annex 3 describes these critiques more extensively and shows how they have repeatedly been advanced. No one seriously contests that these criticisms are real, nor does anyone dispute that the failings need to be remedied. Yet the necessary changes have either not been attempted, or been abandoned before completion, or not been sustained after completion. Remedying these failings requires holistic systemic change, over a timescale that runs well beyond the timespan of any single administration.

4.5 These problems have been consistently articulated in and since the Fulton Committee’s report in 1968. The reforms and changes needed to remedy these failings together add up to an incredibly demanding change management exercise: a huge transformation programme, requiring systemic and cultural change throughout a vast and complex organisation. Many of the failings are interconnected, and the remedies needed have many interdependencies. 4.6 While support from ministers will be important, the principal responsibility to remedy these longstanding deficiencies lies with the leadership of the Civil Service, as Sir John Kingman, former Second Permanent Secretary in HM Treasury, has said:

The fact is that most of the items on the reformers’ shopping-list – more expertise; less manic turnover of officials in jobs; more competence in execution and delivery; stronger commercial, IT and project capability; more interchange with the outside world; better management of underperformance – are wholly in the mandarins’ gift to make happen.”[footnote 6]

4.7 Success will require the governance and accountability arrangements to be optimised; the right highly qualified people in the right place with the right mandate; and it will take time - certainly much longer than the 4-5 years of the normal electoral cycle.

4.8 So what must change to enable it to happen?

1. Governance - put the right person in charge, with a mandate to drive change

4.9 The Head of the Civil Service (HoCS) has nearly always been a part-time role, doubling as Cabinet Secretary, head of the Treasury or a departmental Permanent Secretary. Historically, the only full time Head of the Civil Service was Sir Ian Bancroft, who served from 1978 to 1981. Even then, responsibility for the Civil Service was split between the Civil Service Department, of which he was the Permanent Secretary, and the Treasury. Responsibility for the Civil Service is still shared with the Treasury.

I had naively thought when I became Minister that the HoCS was like the CEO of a company and had the responsibility and authority for managing the Civil Service but I gradually realised that constitutionally HoCS has no authority over Permanent Secretaries. He is therefore more like the senior partner of a law firm responsible for ethics, who has which office and the Christmas party than a CEO of a company responsible for the efficient management of the organisation for which he is head. And the reason the activities of government often appear not to be joined up is that it is not the job of anyone to join it up.

Lord Sainsbury of Turville, IfG, July 2022[footnote 7]

4.10 The right person to be Cabinet Secretary will be a brilliant policy official, able to provide sophisticated policy and handling advice to the Prime Minister, and to lead the coordination of the government’s policy agenda. The right person to lead a massive change management programme will be an experienced operational system leader with a sophisticated understanding of the levers and interdependencies that can drive change of the required scale across a huge and complex organisation. It is highly unlikely that these qualities will be found in the same individual; and even if they were it is simply not possible for the leader of a transformation programme of this scale and complexity to fulfil it on a part-time basis. So, first and foremost, the Head of the Civil Service must be a separate and full-time position (Recommendation 1). They should set the annual objectives of departmental permanent secretaries, in agreement with ministers, including for the delivery of cross-cutting Civil Service changes. As now, HoCS would be the line manager of departmental permanent secretaries, but would be able to delegate some of this to the Cabinet Secretary, especially for the heads of policy departments.

4.11 Second, the HoCS’ only tools to drive change at present are cajolery and persuasion. These are necessary attributes for any transformation leader, along with inspiration and conviction, but they are not sufficient. The leader must also have a clear mandate, with clear authority, after all the consensus building and cajolery, to lay down what must happen, to support its implementation, and to call out backsliding (Recommendation 2). Their mandate should include capability, culture, recruitment, management information and performance evaluation. The mandate should be set out in a formal delegation letter from the Prime Minister. A draft is included at Annex 5A.

4.12 Third, the HoCS’ mandate must run across the whole Civil Service, including the Diplomatic Service (Recommendation 3). The debate over whether there is one Civil Service or a collection of autonomous departments has been fudged for decades. It is sometimes convenient for it to be seen as unitary and at other times departmental autonomy is preferred. This can no longer be fudged. If there is to be any chance of this long overdue modernisation actually happening, the fudge will have to end. Whether it is described as a unitary Civil Service or not, the Head of the Civil Service must have unquestioned authority, through the Prime Minister’s letter of delegation, to drive the changes right across the whole Civil Service. Some aspects of this are considered in Annex 2.

4.13 However, delivery of the reforms needed to rectify the deficiencies will be really hard and take many years. The dedicated HoCS charged with delivering it will need a different background from the conventional Whitehall leader, as Sir John Kingman suggested in that same lecture:

…the reformers are – just like the reformers of 50 years ago – asking these same individuals to upend and rethink fundamental aspects of the system in which they flourished and which got them to the top.”[footnote 8]

4.14 Whatever their background, the essential qualities for candidates to hold this new dedicated HoCS position will be capability to lead change management across complex organisations, together with readiness to challenge existing assumptions and orthodoxies. For at least the next 10 years, the HoCS should be someone most of whose previous career has been outside the Civil Service, and much has been in the private sector (Recommendation 4). This will give the best chance for the individual to be able to bring a breadth of experience of different organisational cultures to bear on this historic task.

4.15 The responsibilities of the HoCS should include:

a. Capability;

b. Culture;

c. Recruitment;

d. Incentives;

e. Management Information;

f. Performance;

g. Agreeing with ministers the annual objectives for departmental permanent secretaries, including for the delivery of cross-cutting Civil Service changes needed for the delivery of the stewardship obligation; and

h. Appraisal of permanent secretaries, alongside the First Civil Service Commissioner and the department’s lead Non-Executive Board Member.

4.16 The HoCS should also be responsible for defining and publishing a future operating model of the Civil Service, and the transition plan to get there (Recommendation 5). That should include performance targets, investment and budget. This should be agreed through the newly formed Civil Service Board, who will have shared responsibility for delivering it. The HoCS must also, in conjunction with the strengthened Civil Service Commission (CSC), seek the agreement of the main opposition party’s leadership as well as that of the Prime Minister to the proposed operating model and reform programme.

4.17 The HoCS can be given these powers by the Prime Minister as Minister for the Civil Service through a carefully drafted delegation letter (see Annex 5 for a description of the current delegation arrangements, and Annex 5A for a draft letter of delegation).

2. Streamline the current governance structures

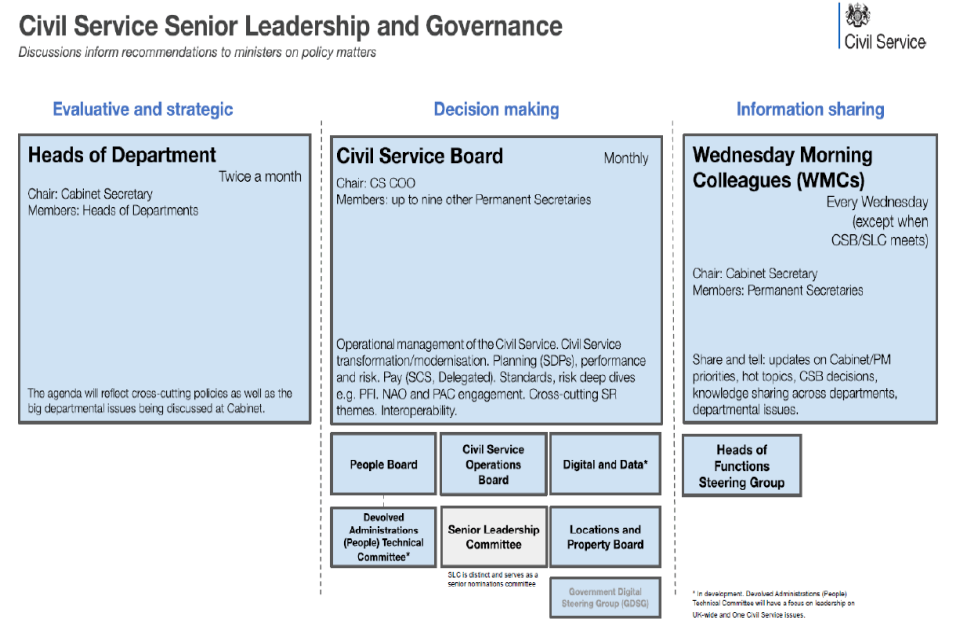

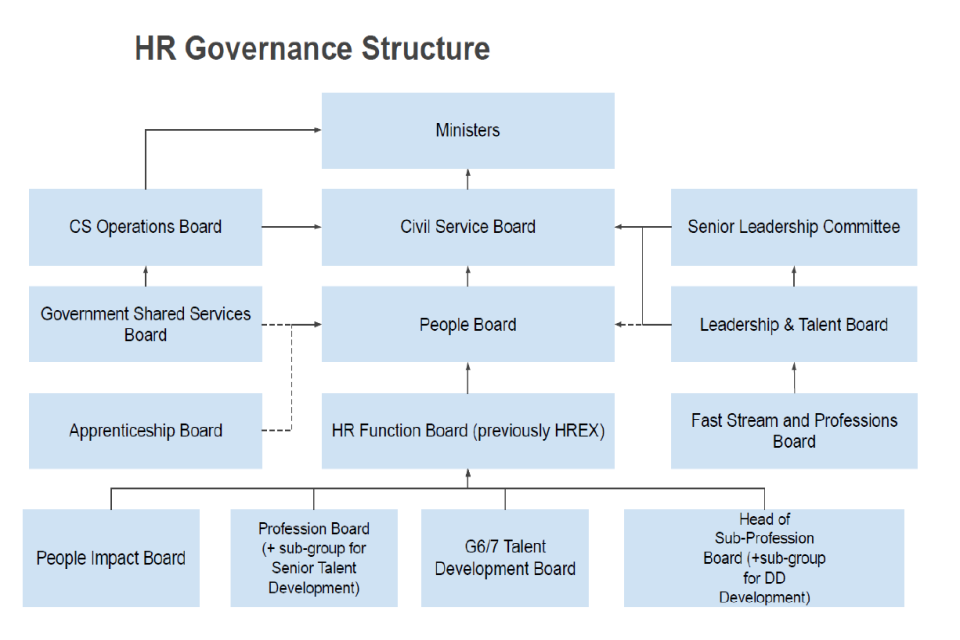

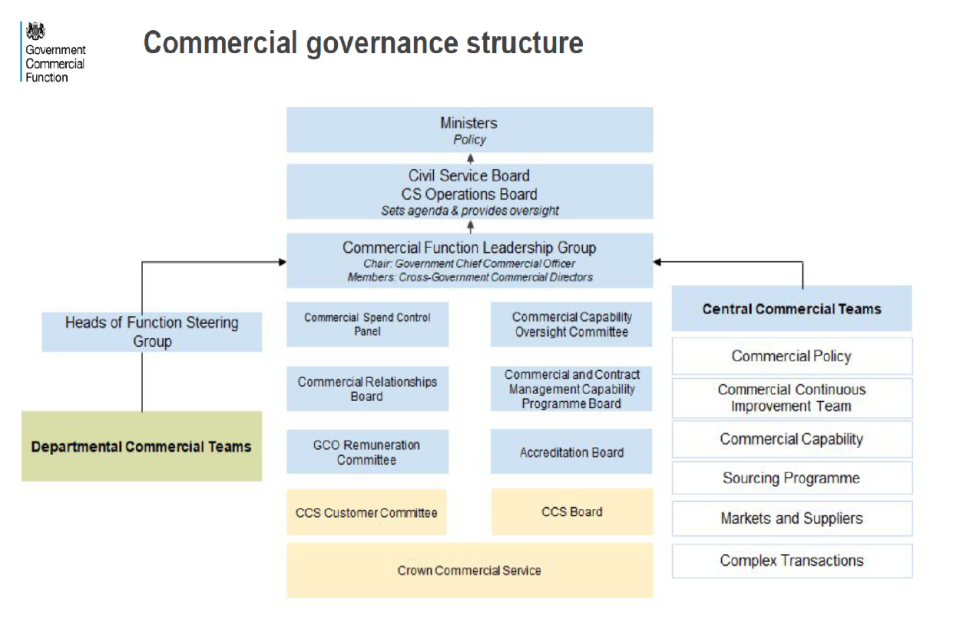

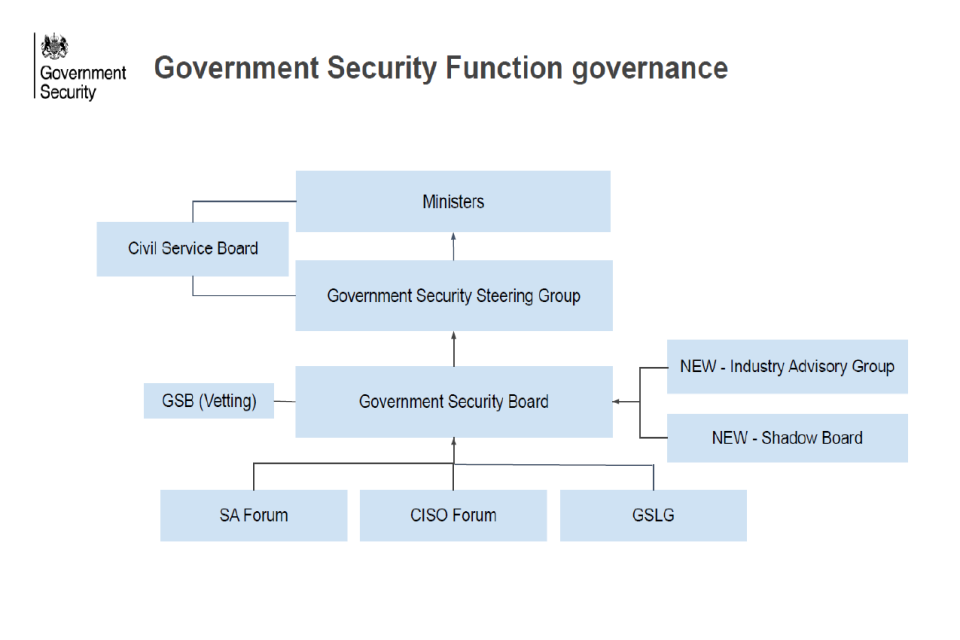

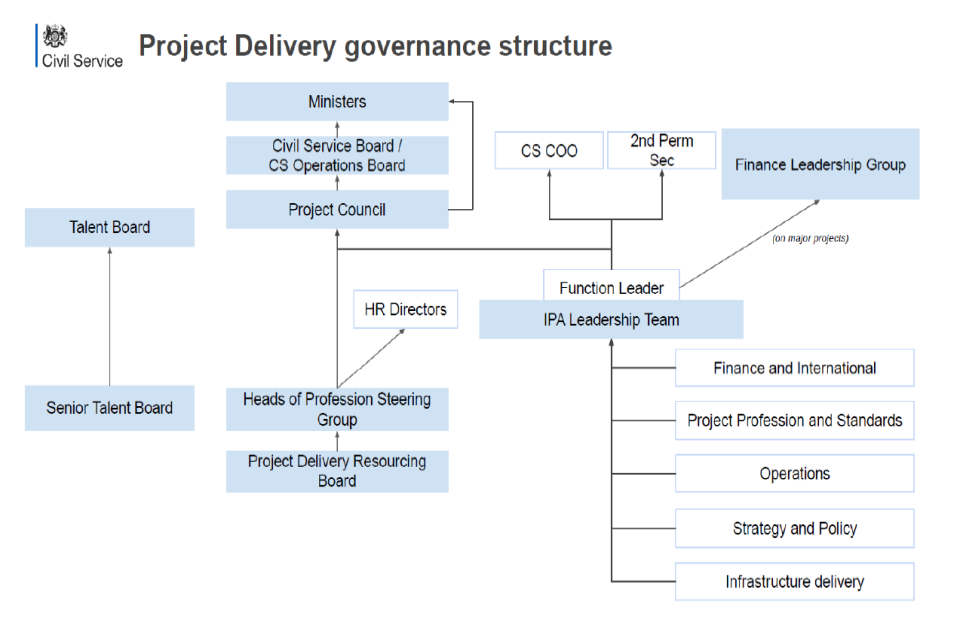

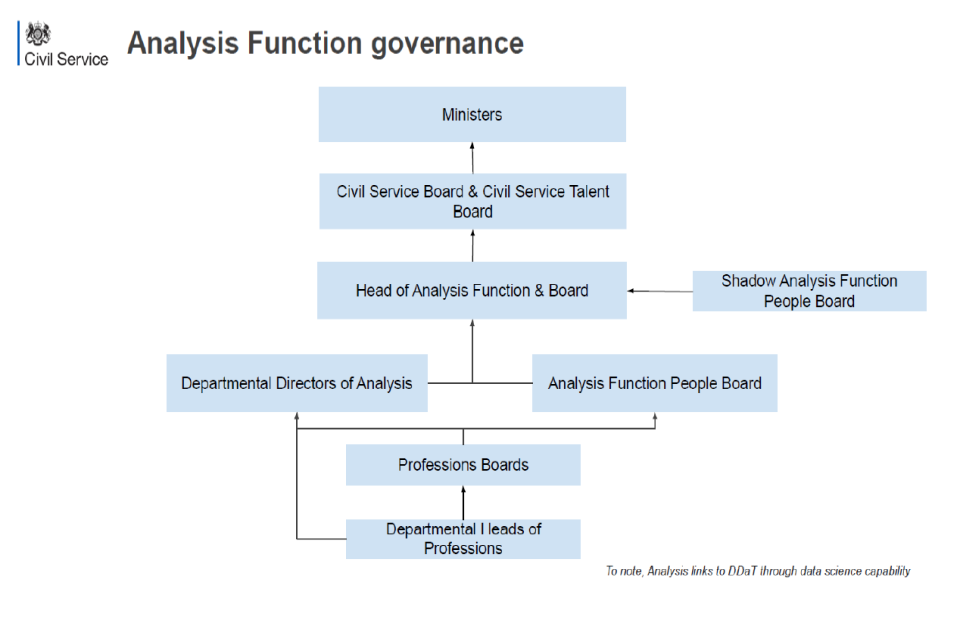

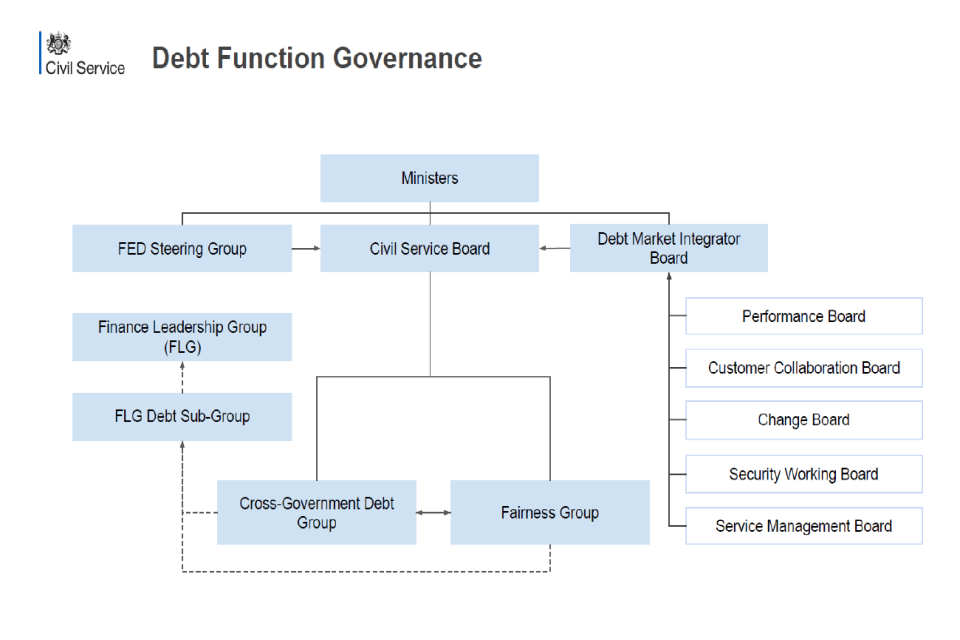

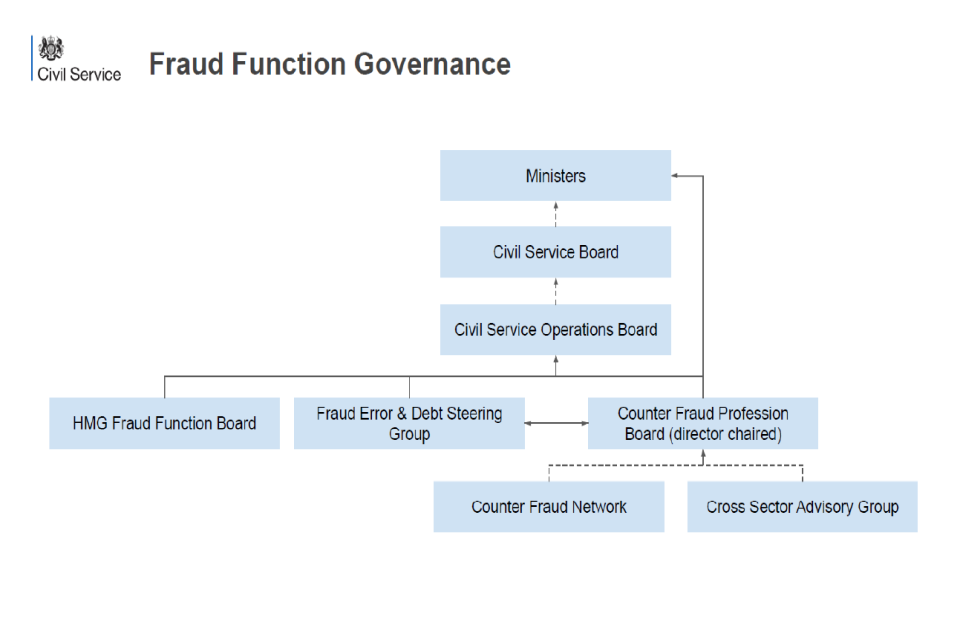

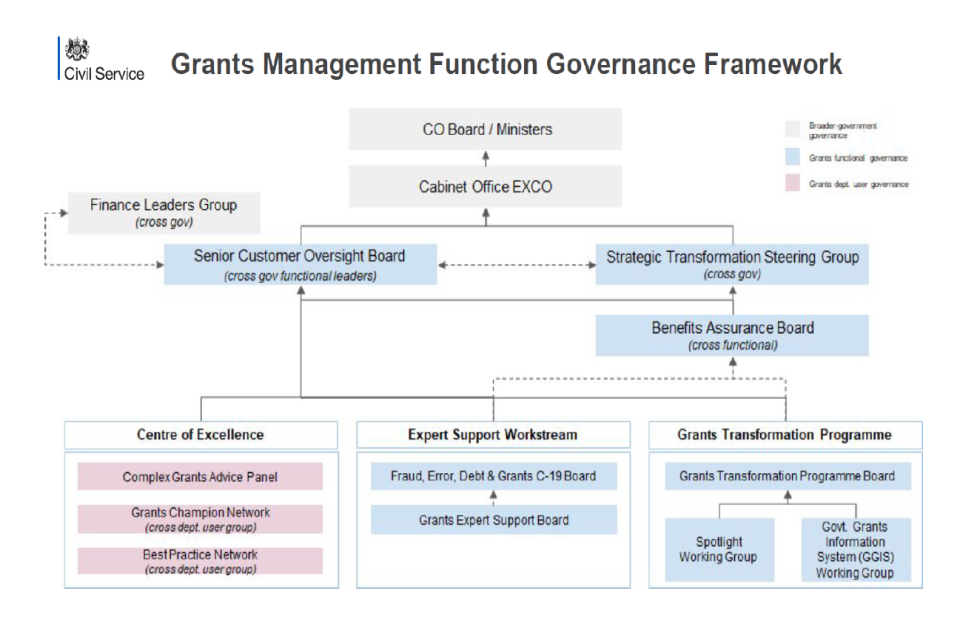

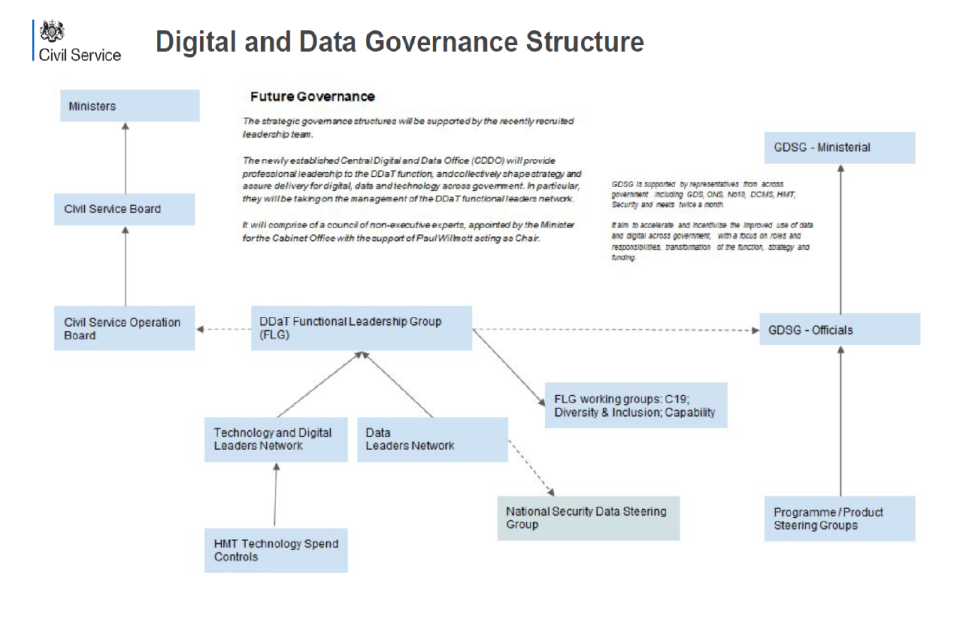

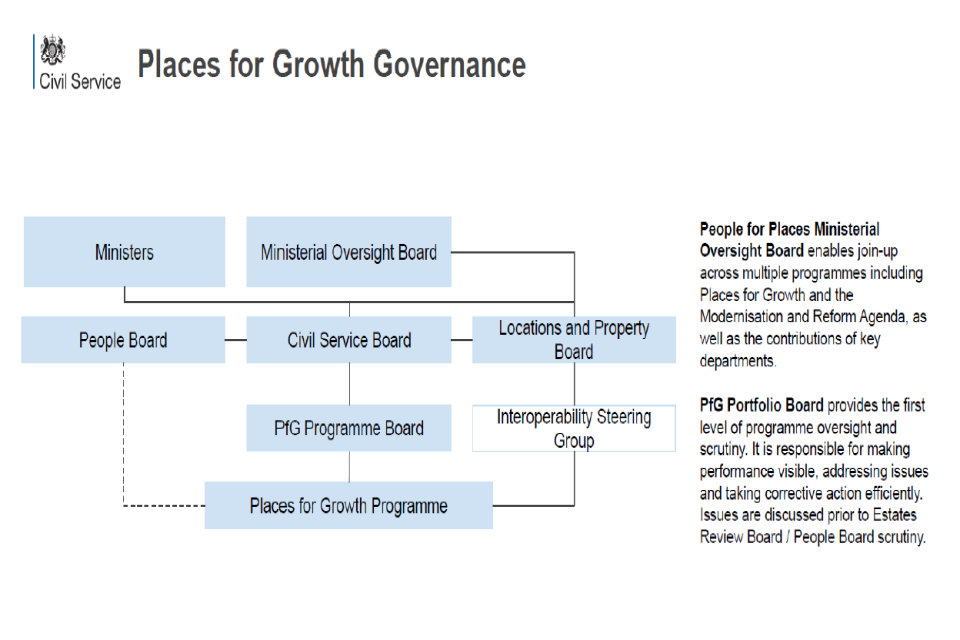

4.18 The current structures are Byzantine and opaque. The web of “governance” bodies at the centre needs to be streamlined and made totally transparent. The lines of authority need simplicity and clarity to minimise the scope for gaming and distraction. Recent organisation charts for the governance of the Civil Service and the Cabinet Office are extremely complex and confusing and demonstrate the urgent need for such reform. An example dating from early 2021 is included at Annex 7 (while this will certainly have been updated and simplified since, I include it to illustrate the tendency to create complexity and confusion, and the need for transparency and discipline).

4.19 There should be a single Civil Service Board to support the HoCS (Recommendation 6). It should be chaired by the HoCS and include:

a. First Civil Service Commissioner;

b. Government Lead Non-Executive Director;

c. Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff;

d. Cabinet Secretary;

e. Three heads of the five principal cross-cutting functions: commercial, digital, financial management, human resources, project delivery - all of whom should be appointed at Permanent Secretary level. The Chief People Officer should always be one of the three; and

f. No more than three departmental permanent secretaries, at least one of whom must have been brought into the Civil Service from outside within the last five years, and at least one from a large operational department.

4.20 The Civil Service Board should support the implementation of the government’s programme, as well as supporting the HoCS in discharging the stewardship obligation.

4.21 There are a number of separate committees that currently have a lot of influence, but do not have clear reporting lines. The Senior Leadership Committee is one such committee. Its remit is described in the Civil Service Management Code (CSMC) at 5.2.1 in this way: “The Senior Leadership Committee (SLC) advises the Head of the Home Civil Service on the senior staffing position across the service as well as on individual appointments”. The membership of the SLC has historically been composed entirely of senior officials plus the First Civil Service Commissioner (and recently expanded to include the Government Lead Non-Executive Member). Elsewhere I recommend that the remit of the CSC should be extended to include oversight of internal appointments at Grade 6 and above. If the SLC continues in this new structure, it should accordingly be chaired by the First Civil Service Commissioner.

4.22 Another meeting is “Wednesday Morning Colleagues” chaired by the Cabinet Secretary. This is a weekly informal gathering intended to be a means whereby Whitehall permanent secretaries can be briefed on collective decisions made by Cabinet and Cabinet committees as well as a forum to discuss thematic cross-cutting policy programmes and their progress. In order to ensure that this important purpose is discharged with full understanding of the nuances, the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff should attend the “Wednesday Morning Colleagues” meeting (Recommendation 7). This will also ensure that the gathering does not assume institutional significance and further complicate the governance of the Civil Service[footnote 9].

4.23 Any additional committees or groups bearing on the governance of the Civil Service must have a clear agenda and outcomes to ensure that they align with and inform meetings of the Civil Service Board (Recommendation 8). The agreement of the Minister for the Cabinet Office (or equivalent), the First Civil Service Commissioner and the Government Lead Non-Executive Director should be required before they are established, and the governance arrangements for the whole Civil Service must be transparent and published on gov.uk.

3. Create effective accountability for the stewardship agenda

4.24 If the right Civil Service leader is in place, with the right mandate and the right governance structure, who will hold them to account for delivering reform, continuous improvement, high capability and strong organisational health? The textbook answer is clear: civil servants are accountable to ministers, who are accountable to Parliament. For all purposes that are to do with the discharge of the business of the government of the day, that is correct, and in later chapters I make some recommendations for how that accountability might be sharpened.

4.25 But the task of implementing the transformation needed to address the long-identified failings is certain to transcend the life span of any government. In any event all organisations need continuous improvement and reform as technological and operational innovation opens the door to ever greater eiciency and effectiveness, and this needs to happen irrespective of the electoral cycle. The model of accountability needs to reflect that reality, and even when ministers are willing and able to exercise this accountability it cannot be assumed that this oversight will be carried over from one minister to another, let alone from one government to another.

4.26 Accordingly, it becomes essential to make a distinction between what is the business of the government of the day, and the “stewardship obligation”. The former must, of course, be the primary focus of the Civil Service leadership, and its delivery must be pursued with wholehearted dedication. Incumbent ministers will hold the Civil Service to account for that.

4.27 However, I have concluded that it is simply unrealistic to believe that ministers alone can effectively hold the leadership of the Civil Service accountable for the stewardship agenda. I was myself the minister responsible for pursuing a broadly bipartisan Civil Service reform programme and remained in post for the unusually long period of five years. I am therefore well qualified to conclude that the textbook answer will not deliver the radical and lasting transformation that is needed. Former permanent secretaries have commented that Civil Service reforms often falter through a lack of ministerial interest.

4.28 It becomes essential therefore to identify a source of accountability beyond ministers. A reformed and strengthened CSC should fulfil that role, supported by the Government Lead Non-Executive Director and network of departmental board Non-Executive Board Members , and reporting annually to Parliament (Recommendation 9).

4.29 The CSC has a statutory duty, under the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 (CRAG), to uphold the merit principle in external appointments and to investigate potential breaches of the CSMC that are brought to its attention by civil servants. The First Civil Service Commissioner is a part-time office holder, paid less (albeit pro rata) than a middle-management grade civil servant and dramatically less than other public sector regulators. The Commissioner is supported by a group of fee-paid Commissioners who can devote only limited time to their duties. The CSC has a secretariat of just 13-14 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff, all seconded from the Civil Service. Its chief executive, a civil servant, reports to and is line-managed by the head of propriety and ethics in the Cabinet Office. Its budget is set by the Cabinet Office. Paragraph 3.2 of the Memorandum of Understanding between the Cabinet Office states: “The Commission shall be reviewed on a regular basis to give the Cabinet Office confidence that the Commission is delivering high-quality services, efficiently, and effectively, in accordance with Cabinet Office’s own guidance.”[footnote 10] The Civil Service Commissioner has no power to oversee or investigate internal appointments within the Civil Service, and it has no power to annul appointments that have been improperly made.

4.30 So the current institutional arrangements of the CCS militate strongly against its ability to operate as an independent regulator of the Civil Service. Indeed, historically it has seen its role less as a regulator of the Civil Service than as its protector; and with its sole specified responsibility for overseeing external recruitment it has tended to focus on guarding the perimeter. Its role has largely been a passive one, primarily to prevent “bad things” happening - principally “politicisation” and the dilution of the merit principle. Until the appointment of Baroness Stuart, both First Civil Service Commissioners since the passage of the CRAG have been former Permanent Secretaries, and until her appointment there has never been a Commissioner with ministerial experience.

4.31 Its counterparts in, for example Australia, New Zealand and Singapore, operate with a much stronger bent towards the proactive promotion of “good things”, with a real focus on improving capability and effectiveness.

4.32 If this broader and more proactive role for the CSC is to be created, with a longer time horizon, then changes in its composition and support will be needed (the legislation permits this to be done by agreement with the Minister for the Civil Service). In this model, in addition to its statutory functions, the CSC would become the custodian of an agreed portfolio of reforms, and would be required to hold the HoCS to account for their implementation. Its role would include liaising with opposition parties as well as incumbent ministers to maximise cross-party support for change. At a change of government the First Civil Service Commissioner would seek to secure the commitment of the new Prime Minister to the agreed portfolio of reforms. This is to ensure continuity, and to minimise the chances of inconvenient reforms being quietly dropped.

4.33 To enable it to carry out this enhanced and more active role, some changes will be needed (Recommendation 10):

- The First Civil Service Commissioner should be a full or nearly full-time role, paid at a level equivalent to regulators in the utility sectors;

- No civil servants should be involved in any way with the recruitment and selection of Civil Service Commissioners. The selection panel should be appointed by the Prime Minister after taking advice from the First Civil Service Commissioner, and should generally include the Chair of the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee and the Government Lead Non-Executive Director.

- As agreed following the 2014-15 Triennial Review, its staff should not mostly be current or former civil servants. As also recommended in that Review, the CSC should exercise its statutory authority to employ its own staff;

- It should set its own budget, reflecting the need to be adequately resourced to perform this broader and more proactive role. It would recover its costs from departments and other bodies that employ civil servants on a prorata basis;

- In order to obtain maximum bipartisan support for the stewardship agenda, the CSC should include as Commissioners a former minister from each of the major UK political parties. This will have the additional benefit of ensuring that there is a ministerial perspective in the CSC’s deliberations, and provide an added safeguard against partisan “politicisation”;

- The First Civil Service Commissioner should hold a rolling checklist of agreed reforms and objectives, and support - and hold to account - the HoCS for their implementation;

- In addition to overseeing recruitment competitions, the CSC must ensure that the HoCS has a serious succession plan for the most senior civil servants and that potential leaders are properly trained and prepared;

- As part of its oversight of the organisational health of the Civil Service, alongside its oversight of external recruitment, it should have a power to oversee internal appointments within the Civil Service, and to annul appointments that have been improperly made;

- The First Civil Service Commissioner should take part in Permanent Secretary appraisals, alongside the Head of the Civil Service (or Cabinet Secretary where this is delegated by HoCS) and lead Non-Executive Board Members;

- The First Civil Service Commissioner should report annually to Parliament, alongside the Government Lead Non-Executive Director, who should have unconstrained visibility into all these streams of work.

4.34 These changes would make the CSC a genuinely independent regulator of the Civil Service, with a broad proactive role much closer to that of its equivalents in Australia, Singapore and New Zealand. The involvement of former ministers from both major UK political parties will make it possible to secure maximum cross-party consensus for reform. This will create the reasonable expectation that reforms will be retained should there be a change in Government.

Non-Executive Board Members

4.35 In the chapter on Accountability in Departments I review the role of departmental boards and the role of Non-Executive Board Members (NEBMs). This network of around 80 NEBMs should play an important but largely informal role in these enhanced accountability arrangements. They will be able to provide insights into what is actually happening in departments, and can be “eyes and ears” for the enhanced CSC in assessing progress in delivering on the stewardship obligation.

4.36 In particular, the role of the Government Lead Non-Executive Director can be pivotal. With any regulatory authority the danger of regulatory capture is ever-present, and the Government Lead Non-Executive Director, having full visibility into the CSC’s work and reporting to Parliament alongside the First Civil Service Commissioner, can provide an important safeguard against that.

4.37 Recently, the appointment of NEBMs to ministerial departmental boards has come under the purview of the Commissioner for Public Appointments. PACAC in its recent report into the role of NEBMs recommends that the appointment of the Government Lead Non-Executive Director should be subject to pre-appointment scrutiny by the select committee. There could be advantages in this if it were seen to confer greater authority on the holder of the post.

4. Who marks the homework?

4.38 The previous section describes how accountability for the overall stewardship agenda can be improved. However there is one additional change needed. When external reviewers have made recommendations for changes in the way the Civil Service operates, it is left to the Civil Service itself to assess their implementation. This is fraught with danger. As a former Permanent Secretary recently commented, referring to the implementation of reform: “permanent secretaries are probably the most non-compliant people in the country but they are very clever in the way that they are non-compliant…”[footnote 11]

4.39 It should be standard practice that reviewers should be invited back two years after their reports are delivered to assess, for publication, the state of implementation (Recommendation 11). This does not routinely happen. It would have been useful for those conducting the four equality reviews commissioned by the coalition government[footnote 12] to have returned to assess progress. Compliance in Whitehall sometimes pays lip service to implementation, where some obeisance is made to the form of the recommendations, while the substantive intention is bypassed. This is one aspect of the absence of organised scrutiny described in the Prologue to this report.

5. Other approaches

4.40 I have had numerous discussions with many current and former ministers and officials - and of course many others - about the recommendations in this chapter. I have found a surprisingly high degree of consensus. However there are two areas in particular where differences have emerged.

4.41 The first area of difference is the proposal to separate the role of the HoCS from the Cabinet Secretary. There has been pushback from some current and former Whitehall officials and their argument runs as follows: “All authority flows from the Prime Minister. The Cabinet Secretary sees the Prime Minister every day, and as HoCS their ability to drive change through the agency of fellow permanent secretaries comes from the sense that they speak with the authority of the Prime Minister. When there are bandwidth constraints the demands made of oicials by ministers will always trump the less immediate requirements of delivering on the stewardship agenda. The only person who can have any chance of success in achieving some kind of balance is the individual who sees the Prime Minister every day and speaks with his or her authority.”

4.42 Having worked in or near the centre of government at various points in the last four decades, I understand the force of this argument. However, I believe it can no longer be allowed to stand in the way of progress.

4.43 First, these are the current arrangements, and they have simply not worked. It has not been for want of capable people trying. Some previous incumbents have taken very seriously the stewardship obligation that comes with the leadership of the service, and yet, despite making some progress, it has neither been anywhere near complete, nor has it been sustained.

4.44 Second, the qualities needed for each of these jobs are radically different, and virtually impossible to find contained in one individual.

4.45 Third, it is just ludicrous to suppose that a change management programme of this complexity and magnitude can be undertaken on a part-time basis.

4.46 It has then been urged upon me, if all of the above is accepted, that my objections can be met by appointing a dedicated change manager as deputy to a combined Cabinet Secretary and HoCS. This position could be described as Civil Service CEO or COO. But this also has been tried, without success in really moving the needle in a sustained way, despite one appointee being a highly experienced and seasoned senior business leader with a successful track record as a change manager.

4.47 My conclusion is that the premise of this argument is the root of the problem. If we accept the premise that improvements will only be implemented if the Cabinet Secretary can carry the immediate authority of the incumbent Prime Minister then we are accepting that these - by common consent essential - changes will be dependent on the incumbent leader being willing to invest authority in them.

4.48 The only real chance that these changes will be executed and sustained in a reliable way is if:

- there is accountability that exists independently of the government of the day; and

- the leadership of the institution to be reformed is not someone who owes their position to a successful career in the unreformed institution.

4.49 Accordingly, I conclude that separation of the roles provides the only credible route to breaking the reform logjam.

4.50 The second area of difference comes from the opposite direction, with the proposal that the Civil Service should be placed on a fully statutory basis (CRAG creates a relatively light touch statutory framework). The stewardship obligation would be set out in statutory form and made the responsibility of the HoCS, heading a statutory Civil Service Board, with independent NEBMs from outside government.

4.51 This position has been powerfully urged by the Institute for Government (IfG) and its founder, Lord Sainsbury. They share much of the analysis in this chapter in relation to the failure to implement agreed reforms. They share the conclusion that breaking the logjam requires a different route of accountability for the stewardship obligation, which in their prescription would include preparation for emergencies and diversity and inclusion.

4.52 I have considered carefully whether this could be the solution. I have rejected it for several reasons. The first is that it would fundamentally change the relationship between ministers and the Civil Service. The definitive statement of the relationship was made by the then Head of the Civil Service, Sir Robert (later Lord) Armstrong in 1985. He said:

Civil servants are servants of the Crown. For all practical purposes. the Crown in this context means and is represented by the government of the day….. The Civil Service as such has no constitutional personality or responsibility separate from the duly constituted Government of the day.

4.53 This formulation is not substantially changed by CRAG. However, a statutory basis along the lines of the IfG’s proposal would fundamentally change it, and would represent a major constitutional reform, with all the attendant controversy and delay. It would set up significant potential conflict between the HoCS and the Prime Minister, when, for example, the HoCS felt obliged to disobey a Prime Minister’s instruction on the basis that it conflicted with the statutory obligation to pursue reform[footnote 13].

4.54 Of course that conflict can occur with the arrangements proposed in this review. I am clear that if that conflict were to arise, the will of the government of the day must prevail. The remedy lies not in statutory law, but in transparency, with the CSC being obliged to report to Parliament any failure to deliver on the stewardship obligation. In those circumstances, the Prime Minister will be answerable to Parliament to account for the failure, and the constitutional position is unchanged.

4.55 It has always been understood that there are activities associated with a permanent Civil Service which go beyond its duty to serve the government of the day. An example is the custom that the Civil Service is briefed by the opposition before an election, and during the election makes preparations for a possible change of government, including understanding in advance how best to serve a new government and implement its programme. But this is by custom, not by right, and the agreement of the incumbent Prime Minister is required on each occasion.

Key Recommendations

Governance

- Recommendation 1: The Head of the Civil Service must be a separate and full-time position. The HoCS should set the annual objectives of departmental permanent secretaries, in agreement with ministers, including for the delivery of cross-cutting Civil Service changes.

- Recommendation 2: The Head of the Civil Service must have a clear mandate, with clear authority to lay down what must happen across government for the delivery of reforms, to support its implementation, and to call out backsliding. Their mandate should include capability, culture, recruitment, management information and performance evaluation.

- Recommendation 3: The Head of the Civil Service’s mandate must run across the whole Civil Service, including the Diplomatic Service.

- Recommendation 4: For the next ten years, the Head of the Civil Service should be someone most of whose previous career has been outside the Civil Service, and much has been in the private sector.

- Recommendation 5: The Head of the Civil Service should be responsible for defining and publishing a future operating model of the Civil Service, and the transition plan to get there. That should include performance targets, investment and budget.

Streamlining the current governance structures

- Recommendation 6: There should be a single Civil Service Board to support the Head of the Civil Service. The Board should include the First Civil Service Commissioner, Government Lead Non-Executive Director, Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff, the chief people officer and two of the heads of the other principal cross-cutting functions: commercial, digital, financial management, Infrastructure and Projects Authority; all of whom should be appointed at Permanent Secretary level.

- Recommendation 7: The Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff should attend the “Wednesday Morning Colleagues” meeting of permanent secretaries.

- Recommendation 8: Any additional Civil Service governance committees or groups must firstly be agreed by ministers and secondly have a clear agenda and outcomes to ensure that they align with and inform meetings of the Civil Service Board.

Accountability

- Recommendation 9: The Civil Service Commission should be reformed to play a more proactive role, with focus on improving capability and effectiveness, in line with counterparts in Australia and New Zealand. A reformed and strengthened Civil Service Commission should fulfil that role, with a lead First Civil Service Commissioner supported by the Government Lead Non-Executive Director, network of departmental board Non-Executive Board Members and former ministers.

- Recommendation 10: The following changes to the role and composition of the Civil Service Commission should be implemented:

- The First Civil Service Commissioner should be a full-time position with pay which is commensurate with the gravity and importance of the role, and which is comparable to equivalent positions elsewhere within the UK and other jurisdictions. The leadership and staff should not be current or former civil servants;

- No civil servants should be involved in any way with the recruitment and selection of Civil Service Commissioners. The selection panel should be appointed by the Prime Minister after taking advice from the First Commissioner, and should generally include the Chair of the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee and the Government Lead Non-Executive Director;

- The Civil Service Commission should employ its own staff in line with the recommendations of the 2014 Triennial Review, rather than only civil servants as is the case at present;

- The Civil Service Commission should set its own budget, recovering its costs from departments and other bodies that employ civil servants on a prorata basis;

- The Civil Service Commission should be given the power to oversee and investigate internal appointments at Grade 6 and above and to annul internal appointments improperly made;

- The Civil Service Commission should always include a former minister from both major UK political parties. This will ensure that there is a ministerial perspective in Commission deliberations and facilitate a cross-party consensus for reforms;

- The Civil Service Commission’s responsibilities should be expanded to include exercising accountability for the stewardship agenda; capability planning and appointments; and a role in performance management of Permanent Secretary appraisals.

- Recommendation 11: Anyone invited to conduct a review into any aspect of the Civil Service should be invited back two years after submitting their recommendations to assess progress in implementation. Their follow-up assessment should be published. Ministers should have the opportunity to receive written or oral updates directly from the reviewer.

The Centre of Government

1. Reshaping the centre of government

5.1 The UK is now an outlier in terms of the shape of the centre of government, compared with similar jurisdictions. The Cabinet Office is no longer simply the home of the Cabinet and National Security Secretariats, acting as a central coordination hub across Whitehall. Over the last fifteen years the Cabinet Office has evolved to also become the natural home for most of the horizontal and cross-cutting functions across Government (procurement, IT and digital, major projects, property, human resources) making it a much larger entity, with some of the characteristics of a corporate headquarters. The Prime Minister’s Office has increasingly been seen to be underpowered, with frequent unplanned and ad hoc changes being made both to 10 Downing Street and the Cabinet Office in the quest to create more effective support structures for the Prime Minister.

5.2 The centres of the cross-cutting functions have a very different purpose from the role of the secretariats, which focuses mostly on policy coordination. In other similar jurisdictions, for example, Australia and New Zealand, the traditional secretariats are brought together with the PM’s Office to create a Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC) - in Ireland the Office of the Taoiseach. This can create an effective strategic centre, which gives overall direction to the government. The time is now right to bring the UK in line with similar jurisdictions. The centre of government should be reshaped, with the parts of the Cabinet Office that are concerned with coordination and policy advice brought together with the Prime Minister’s Office to create a new Office of Prime Minister and Cabinet (OPMC) (Recommendation 12).

5.3 In this model, in addition to the Prime Minister’s obvious role, there would be a second cabinet minister, ideally from the House of Lords to avoid the distractions of an MP’s constituency duties, who could act as the Prime Minister’s Chief of Staff. The Cabinet Secretary (relieved of the burden of being also Head of the Civil Service) would be the Permanent Secretary sitting over the new Office of Prime Minister and Cabinet, which would be the strategic centre of government. Responsibility for major events, constitutional and devolution matters would sit with the secretariats in OPMC, together with the centre of the cross-government communications function. The Cabinet Secretary would continue to exercise the quasi-constitutional functions - such as liaison with the Palace, overseeing the transfer between one Prime Minister and the next. For administrative purposes, OPMC would be the natural home department for non-departmental ministers, such as a Deputy Prime Minister, the Leaders of the Commons and the Lords, and the Whips’ Offices.

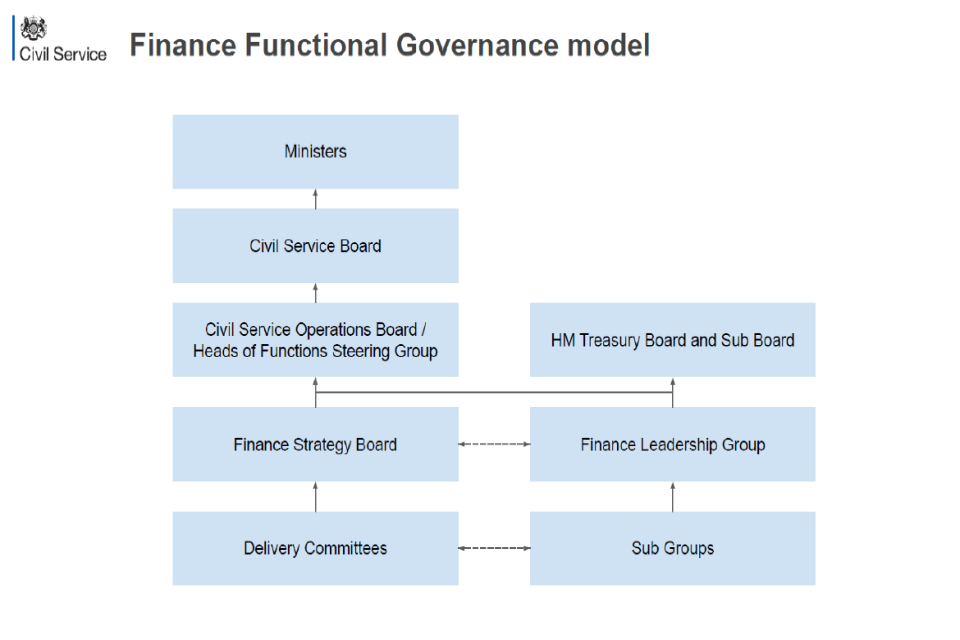

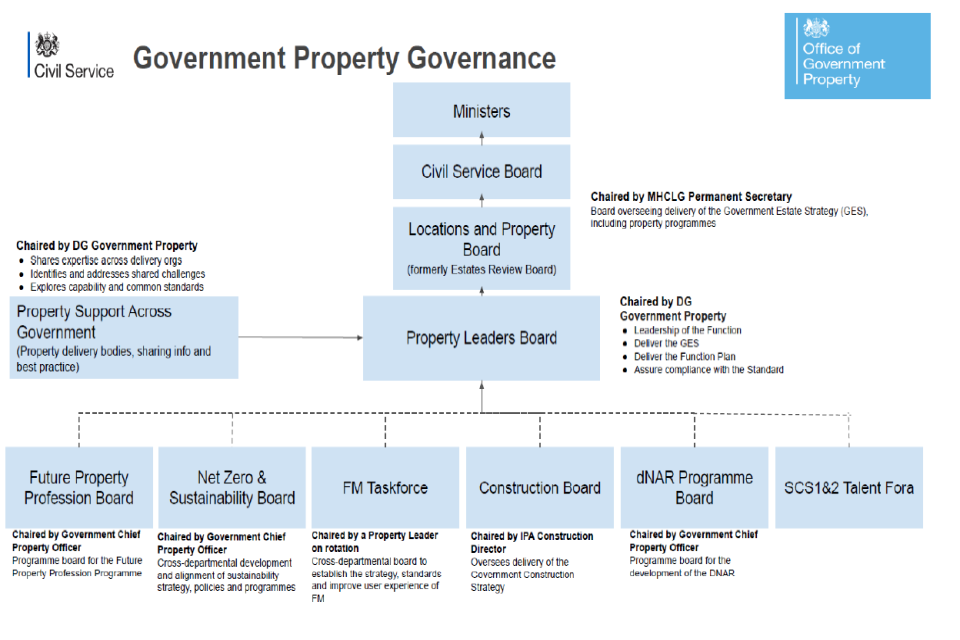

5.4 There is another respect in which the UK is an outlier. In all other governments with a similar system, allocation and oversight of public expenditure is separated from the principal financial and economic ministry. The labels of these ministries vary, but broadly this split operates in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the Republic of Ireland. If this approach were to be applied in the UK, the Treasury would remain responsible for economic growth, macro economic policy, macro fiscal policy (including the overall spending envelope), taxation and financial services regulation. All matters to do with public expenditure, including the allocation of budgets and the Treasury’s spending teams, would be brigaded together with the central functions currently housed in the Cabinet Office (except for communications) to create a new Office of Budget and Management (OBM). This would include the cross-cutting functions currently headquartered in the Treasury i.e. financial management and internal audit.

5.5 The Cabinet Minister at the head of the OBM would replace both the Minister for the Cabinet Office and the Chief Secretary to the Treasury. The Head of the Civil Service would be the official head of this new department, with a reporting line to the ministerial head of the department, and to the Prime Minister, for the implementation of the government’s policies and programmes. There would also be an additional reporting line to the Civil Service Commission (CSC) for the implementation of the stewardship obligation, as described in the chapter on The Stewardship Obligation. The role of the HoCS as the official head of the new Office would endow the holder with clear authority and gravitas.

5.6 Bringing together decisions on the allocation of public expenditure with real time oversight of how the money is spent would enable a much more sophisticated and informed approach to controlling the overall spending envelope. It would make the creation of cross-departmental budgets for the implementation of broad cross-cutting programmes such as net-zero, crime reduction and levelling-up much more straightforward. It would create much stronger governance of and real time accountability for the spending of taxpayers’ money[footnote 14]. It would bring into one place responsibility for everything to do with management of the Civil Service - HM Treasury’s responsibility for Civil Service pay makes workforce planning (which requires managing the sensitive interactions between pay and the shape and size of the workforce) infinitely more cumbersome than it need be. The time is now right to bring the UK closer in line with similar jurisdictions by creating an Office of Budget and Management (Recommendation 13).

5.7 This reconfigured centre of government would, as now, require close collaboration between its three components. Coordination between the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet and the Office of Budget and Management would ensure that the allocation of expenditure reflects agreed strategic priorities, and provide greater real time reassurance that the priority programmes and projects were being implemented in a timely and efficient way. Coordination between the Treasury and the Office of Budget and Management would be essential to ensure that the overall expenditure envelope was protected and therefore that macro-fiscal policy was supported.

2. Other approaches

5.8 That the UK’s current model is an outlier among international comparators is indisputable. However others have proposed different configurations. In his 2008 book, “Instruction to Deliver”, drawing on his experience at the centre in Tony Blair’s government, Sir Michael Barber proposed creating only two departments where there are currently three. In his model both the Cabinet Office and the public expenditure parts of the Treasury would be combined with the Prime Minister’s Office. However, his recommendations pre-date the establishment of the functional model, which necessarily involves a greater concentration of headcount at the centre of government. The Commission for Smart Government recommends a similar model, which would also include the centres of the cross-cutting functions.

5.9 These approaches include two elements in common with the recommendations in this report: combining the secretariat functions of the Cabinet Office with the Prime Minister’s Office; and hiving off the public expenditure functions of the Treasury. The difference is that they would create an exceptionally powerful Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, with the allocation and control of public expenditure coming under the direct remit of the Prime Minister.

5.10 There are several reasons for preferring the triangular configuration recommended in this report. First, bringing control of public expenditure directly under the Prime Minister would mark a substantial move towards a much more presidential style of government, and would be likely to be highly controversial. In terms of protecting the “checks and balances” that are so important in the UK’s constitutional arrangements, it is desirable to have a degree of separation between these three institutions. In particular, there is a benign tension in having the control of expenditure at one remove from the Prime Minister’s Office.

5.11 Second, the Prime Minister by definition is always the most powerful minister in the government, and will often want to make changes in the institutional arrangements closest to them to reflect their personal style and preferences. While incorporating the secretariats and other traditional Cabinet Office activities would lend greater stability, there will always be a higher degree of flux than in other parts of government, and that is unavoidable and manageable. Conversely, for the government headquarters functions – financial, commercial, human resources and so on – there is a real premium on continuity and consistency in the institutional arrangements, and it is therefore preferable to keep these headquarters functions separate from the OPMC.

5.12 Third, other comparable governments have not gone down this path and it would be strange to move in one step from the least concentration of power in the PM’s hands to the greatest.

5.13 Naturally in any of these models the traditional ex post facto Parliamentary scrutiny of public expenditure through the National Audit Office (NAO) and Public Accounts Committee (PAC) would remain unchanged, with the addition that officials from the Office of Budget and Management would be able to join their colleagues from the line entities in giving evidence to Departmental Select Committees on specific projects and programmes.

3. Strengthen and streamline the governance of the cross-cutting functions

…we have…convinced the leadership of Civil Service, I think, of the importance of functional leadership - functional leadership being the basic business idea that in multidivisional organisations it’s essential to have at the centre of the organisation technical experts in areas such as accounting, IT and human resources, who set down the technical standards that all divisions should follow and advise on overall policies for the organisation. And today in all three areas there are technical experts at the centre but fairly predictably it is not totally clear what authority they have to lay down the necessary standards or see that they are properly implemented.

Lord Sainsbury of Turville, IfG, July 2022[footnote 15]

5.15 The creation of successful cross-government functions was fundamental to the efficiency and reform agenda of the coalition government. Without clear governance and accountability, they would not have delivered more than £52 billion of savings over the course of that Parliament. They cover a wide variety of activities: financial management, commercial procurement, IT and digital, major projects, property, legal, human resources and internal audit.