The section 60 stop and search pilot: statistical analysis and review of authorisations

Published 19 June 2023

Authors: Michelle Diver, Laura Dewar, Victoria Smith, Jodie Hargreaves, Rob Fulton, James Haslam and Andy Feist

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to a number of colleagues for their support in reviewing, quality assuring, and drafting this report. Thanks go to Oscar Hinze, Patrick Allen, Alex Hicks, Ruby Forshaw, Meghan Marshman, Steve Almond, Emily Fellingham and Megan Perry. Particular thanks go to Daniel Farrugia who was key in the organisation and delivery of our data collection programme.

We would like to thank the police forces which made this project possible by providing the data and responding to our queries.

We would also like to thank our independent academic peer reviewer and members of the Steering Group for their help and advice during the course of the work.

Executive summary

Background

Section 60 (s60) stop and search powers give the police the power to stop and search persons and/or vehicles without reasonable suspicion when violence is anticipated. To enable the police to respond more effectively to serious violence, in March 2019 it was announced that 2 amendments to the Best Use of Stop and Search Scheme (BUSSS) would be piloted in 7 forces in England and Wales.[footnote 1] These forces are referred to as the ‘original’ forces. The amendments reduced:

-

the level of authorisation needed to impose a s60 stop and search, from chief officer to inspector level or above

-

the degree of certainty needed for an authorising officer to impose a s60 from believing an incident involving serious violence ‘will’ occur, to ‘may’ occur

In August 2019 this pilot was extended to all 43 police forces and the British Transport Police. The remaining forces that joined in August are referred to as the ‘later’ forces. All conditions placed by BUSSS on stop and search powers were relaxed meaning that in addition to the 2 existing amendments:

- inspector authorisations could now last a full 24 hours (as opposed to 15 hours)

-

superintendents could now extend an authorisation beyond 24 hours to 48 hours (BUSSS required this to be done at chief officer level, and limited extensions to a total of 39 hours)

- s60s do not need to be communicated publicly in advance

For all of these amendments it remained an operational decision for each police force as to how they were implemented.

This report focuses on a range of data on the operation of s60 during the pilot period[footnote 2] when conditions around authorisations were relaxed. The analysis is designed to complement the linked qualitative study (Smith et al., 2023) based on interviews with officers and community scrutiny leads to gain their views of the relaxations introduced as part of the pilot.

Aims

The main aims of the analysis were:

-

to describe the nature and pattern of s60 authorisations undertaken during the year ending March 2020 across England and Wales, and observe any trends over recent years

-

for a subset of forces, to examine in more depth any changes in authorisations between the year ending March 2019 and the year ending March 2020, including the rank of authorising officer, length of authorisation and geographical coverage

-

to improve understanding of how s60s were communicated to the public via social media, how often this was done and, if so, whether this was before, during or after the authorisation was put in place

-

to identify and describe what types of incidents typically precede a s60 authorisation and better understand what factors are considered in s60 authorisation decisions

The analysis draws on 3 main sources of data. A bespoke data collection covering all 43 forces and the British Transport Police (BTP) during the first year of the pilot (ending March 2020). Additional data were gathered for 6 pilot forces[footnote 3] covering both the years ending March 2019 and March 2020. This included information on the areas covered by authorisations and the use of Twitter to publicise them. Finally, 143 authorisation forms from 5 forces were subject to more detailed review.

Key points/findings

Statistical overview

Although it is not a pure comparison – because of the additional forces that joined the pilot in August 2019 – comparing the pilot period with the full previous year shows a 29% increase in the number of s60 searches. There were 17,267 s60 stop and searches undertaken during the pilot period.

Looking solely at the 7 ‘original’ forces allows a true year-on-year comparison and shows a 9% increase in s60 searches across the 2 years. Most forces increased their use of s60 – with West Yorkshire and South Wales increasing from zero searches in the year ending March 2019. However, West Midlands reduced their s60 volumes during the pilot.

It is not possible to assess the extent to which the relaxations may have directly or indirectly contributed to the increase in s60s during the pilot. The pilot was rolled out in a way that made it difficult to explore any discrete pilot effect on search volumes. The pilot also overlapped with another initiative that might be expected to contribute to an increase in the use of s60s. As part of the drive to combat serious violence, the Treasury agreed to allocate £100m of additional funding in the financial year 2019 to 2020 to the 18 police forces with the highest share of knife injury admissions to hospital.

These 18 forces accounted for 86% of the total increase in s60 stop and searches between the year ending 2019 and the year ending March 2020 (4,008 of an additional 4,666 searches). Despite this, force-level changes in s60 searches in the year ending March 2020 amongst the ‘18’ are far from uniform. The combination of the pilot relaxations and funding enhancements in the year ending March 2020, on top of forces’ variable use of s60, make assessing the impact of relaxations alone on s60 volumes very challenging.

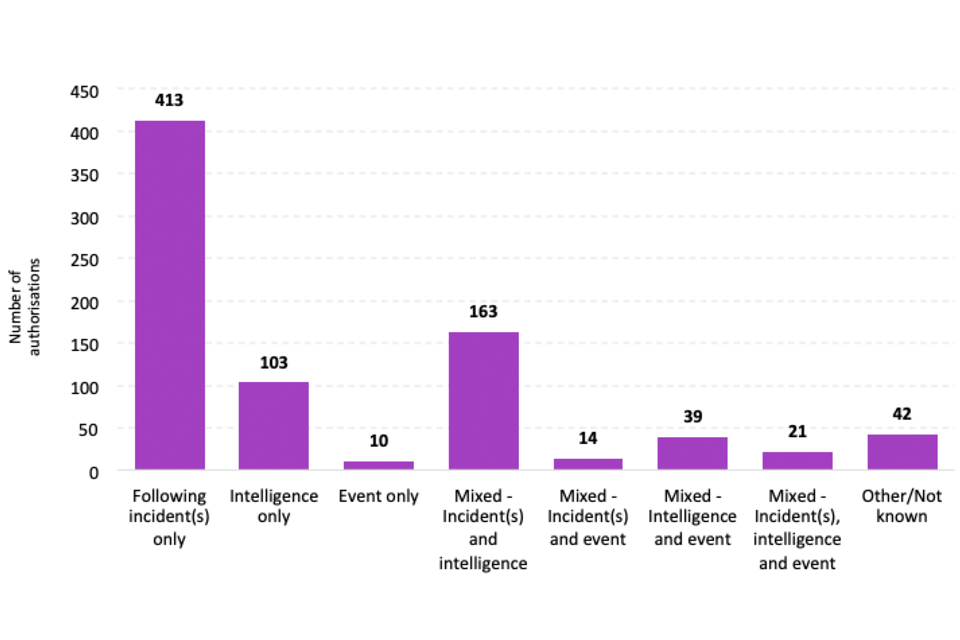

Most pilot authorisations were put in place following an incident, or a previous act of serious violence. In total, 611 of the 805 authorisations (76%) mentioned some previous incident. Of these, 413 were coded as solely following an incident or incidents, while a further 198 also mentioned intelligence or an event. Authorisations linked to events alone were rare (84 were linked in some way to an event).

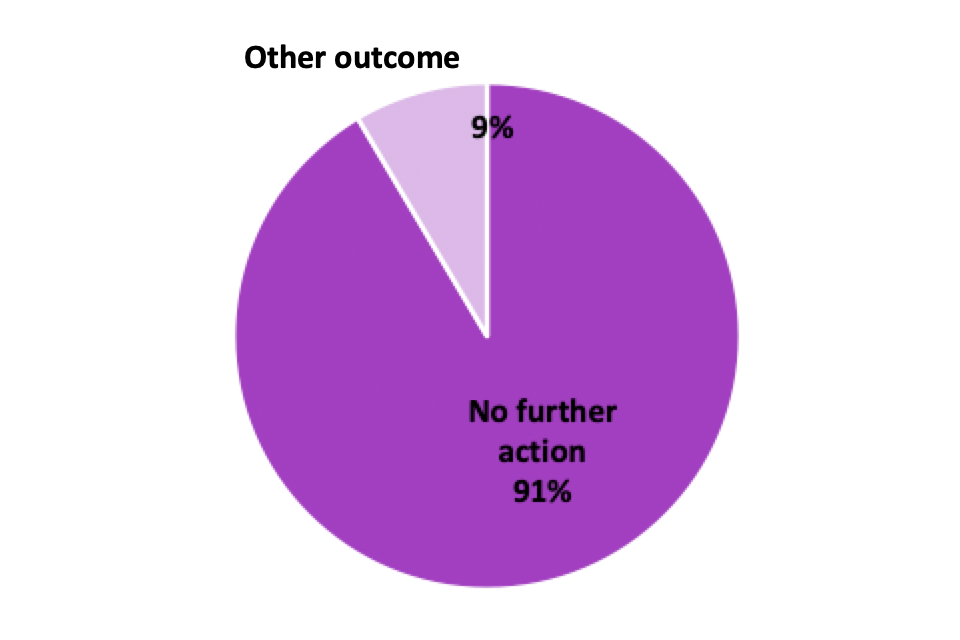

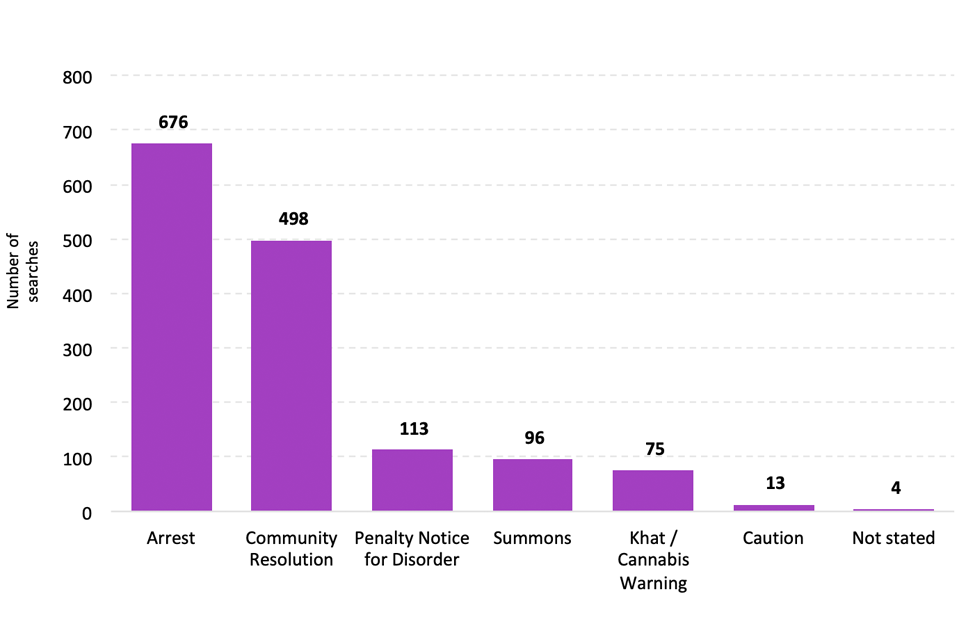

The vast majority of s60 searches conducted during the pilot period (91%) resulted in ‘no further action’. Of the 1,471 searches that resulted in an arrest or criminal justice outcome, 46% resulted in an arrest and 34% in a community resolution. The arrest rate for all s60 searches conducted in the pilot period was 3.9% (4.7% in the year ending March 2019).

In the pilot period, and excluding cases where the ethnicity was not known, 41% of searches were of people who either self-identified as White or, in the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) where self-defined ethnicity was not stated, the officer recorded the person’s ethnic appearance as White. A similar proportion (40%) of searches were conducted on those who either self-identified as Black, or the officer recorded their ethnic appearance as Black. This was followed by the Asian group (12% of searches), the Chinese and Other ethnic group (4% of searches), and the Mixed group (3% of searches).

Authorising officer rank

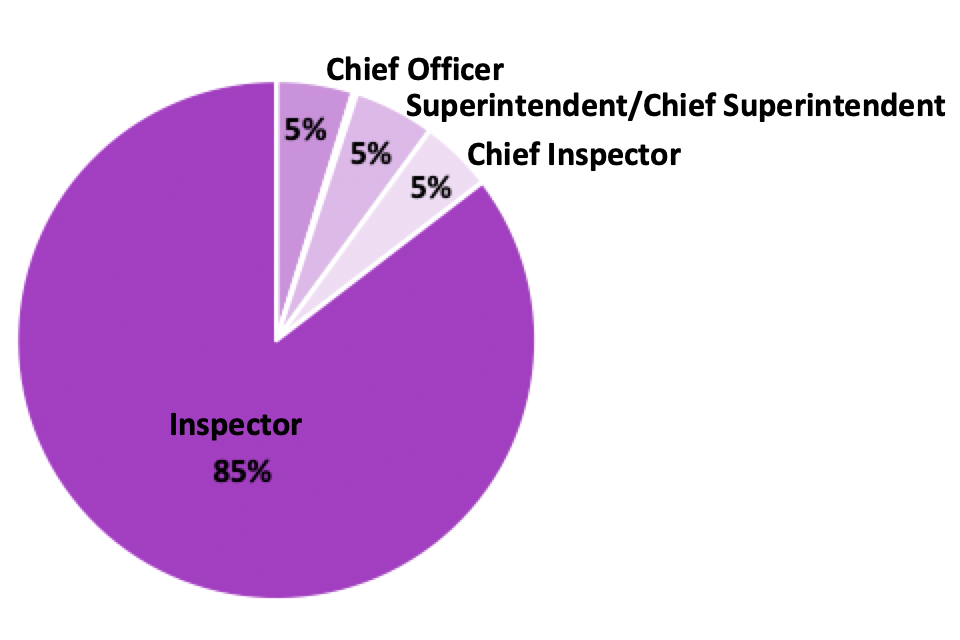

Almost all the police forces that used s60s responded to the April rank relaxation by moving to lower ranks authorising s60s in most cases. For those authorisations where the rank of the authorising officer was known, 85% were initially authorised by an inspector. Just 5% were authorised by a chief officer (assistant chief constable or above), the majority of these being in the West Midlands.[footnote 4] Eight forces continued to have one or more s60s authorised by a chief officer during the pilot period.

Duration of the initial authorisation and extensions

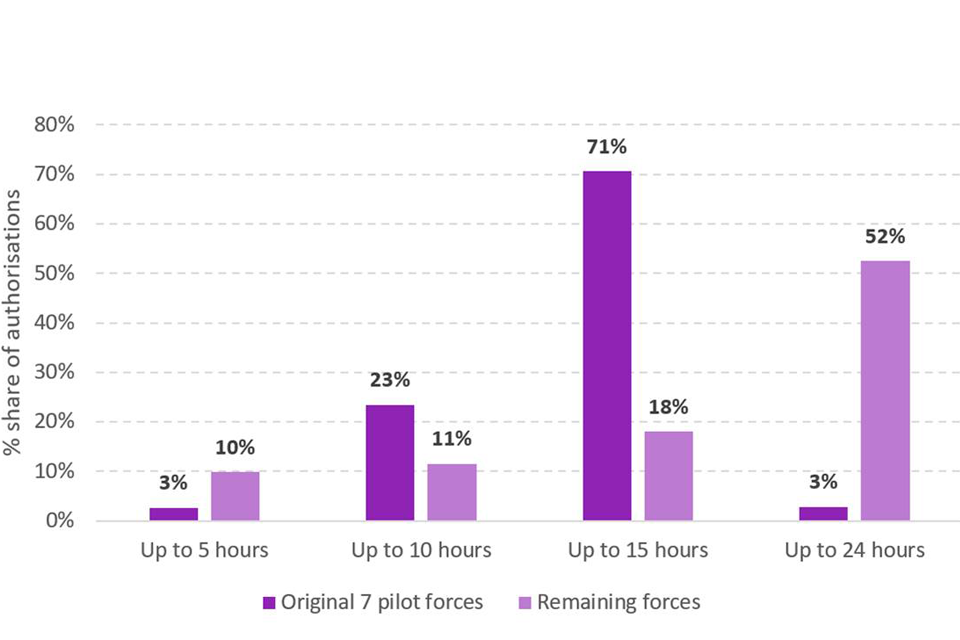

The August relaxations increased the maximum length of initial duration from 15 to 24 hours. Overall, 83% of initial authorisations were for 15 hours or less from August 2019 to March 2020.

The qualitative analysis found that officers in the 7 ‘original’ forces – the biggest users of s60s – were less aware of the ‘August’ relaxations on duration and communications, than the original ‘April’ changes. The data confirm that the ‘original’ forces rarely made use of the permitted increase in durations. Whilst only 3% of the ‘original’ forces’ authorisations were 16 to 24 hours in length, more than half (52%) of the ‘later’ forces’ authorisations were this long.

The relaxations permitted superintendents to extend an authorisation beyond 24 hours to 48 hours. However, extensions were found to be rare, both before and during the pilot. In the 8 months post-relaxation from August 2019 to March 2020, a total of 10 extensions were identified, equivalent to 2% of authorisations. The majority of these extensions were for 9 hours. In the comparison period only 3 extensions were given.

Communicating s60s using Twitter

Under the ‘August’ relaxations it was no longer required for s60 authorisations to be publicly communicated in advance. Twitter data were chosen to examine public communication; based on discussions with police forces it was felt to be one of the most commonly used forms of social media for sharing information on authorisations. However, Twitter is just one of a number of channels that forces can use to communicate with the public, therefore not all communications of s60 authorisations will have been captured.

During the August pilot period the proportion of authorisations with identified tweets ranged from 15% to 85% for the 6 forces. All but one force, and all the high-volume forces, tweeted at least half of their authorisations. For all 6 forces combined, over half (54%) of the authorisations were tweeted in the August pilot period. The corresponding figure for the August comparison period was 53%. It is not possible to infer a causal relationship between the relaxations and the proportion of authorisations tweeted.

The Twitter data include time stamps, which allow the precise timing of the tweet to be established. For those authorisations that were tweeted, the vast majority were communicated during (75%) or before (23%) the authorisation period. Very few were tweeted about after the authorisation period had concluded. Details of authorisations were most commonly tweeted within the first 2 hours of the authorisation.

Authorisations and searches

The 805 authorisations in the pilot period resulted in 17,070 searches[footnote 5] (this figure excludes Lancashire, who could not provide information on authorisations), with a mean of 21 searches per authorisation. Around 1 in 10 authorisations during the pilot period involved no stop and searches, while a further 61% involved 20 searches or less. A small number of authorisations involved in excess of 60 searches (4%).

S60s authorised by chief officers had more searches per authorisation (96 searches) than all other ranks. Those authorised by chief superintendents had the fewest searches per authorisation (8 searches) while inspectors, who were responsible for the majority of s60s, had 15 searches per authorisation on average.

When searches by authorisation were examined in relation to search outcomes, authorisations with fewer searches had a higher rate of searches resulting in an arrest or criminal justice outcome. Authorisations with between 1 and 10 searches had a success rate of 13%, compared with 7% for authorisations with between 51 and 60 searches.

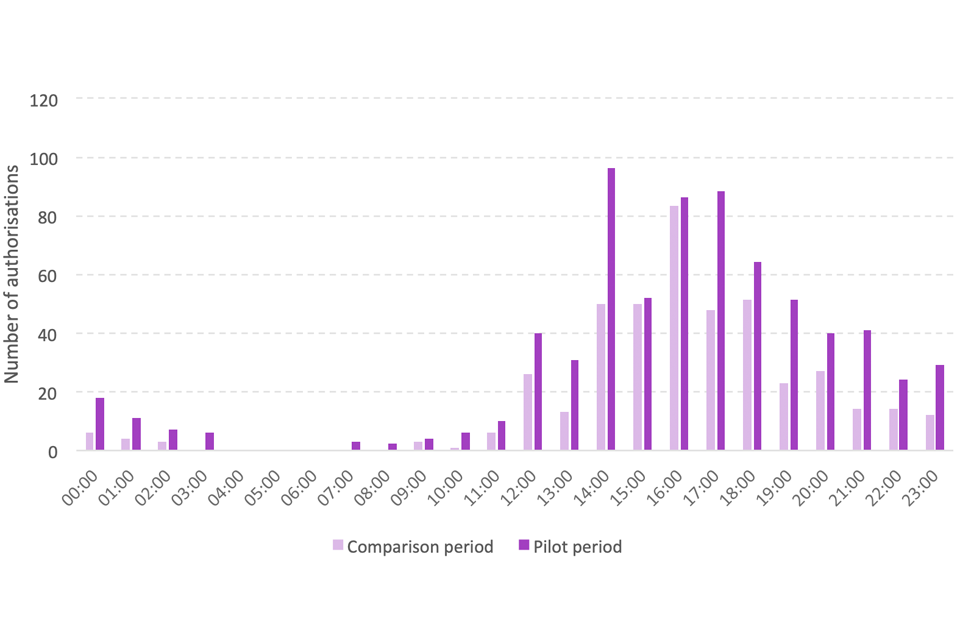

The most common time of day for authorisations to be initiated was between 2pm and 5pm. Given that most lasted for less than 15 hours this meant that authorisations were in force overnight and expired early the following morning.

The geography of authorisations

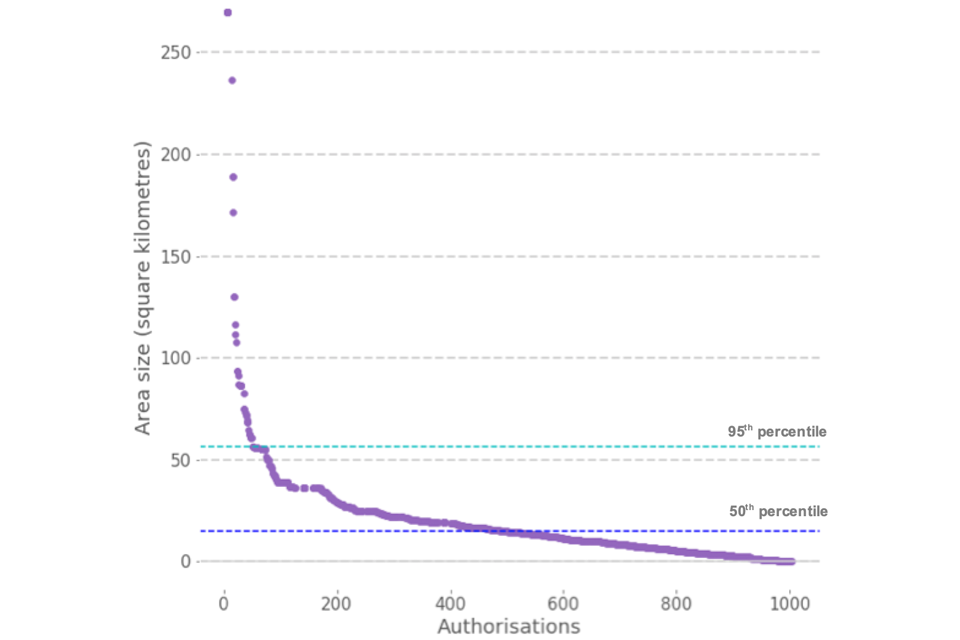

The geographical coverage of authorisations was examined for 5 police forces.[footnote 6] Of just over 1,000 authorisations analysed, the typical area covered was 15km2, slightly bigger than the area covered by Heathrow Airport. The largest authorisation covered the City of Birmingham (over 270km2); 1% of authorisations were less than 0.3km2.

The median size of the MPS authorisation areas decreased between the comparison and pilot periods, from 19.1km2 to 16.0km2. This represents a statistically significant difference in the distribution of the size of authorisation areas in the year ending March 2019 and the year ending March 2020.

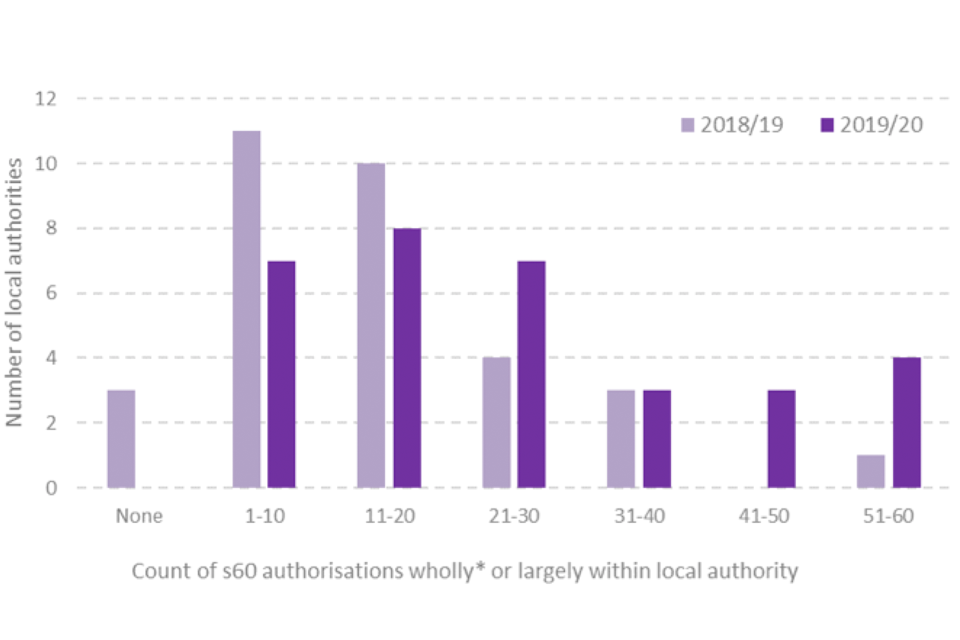

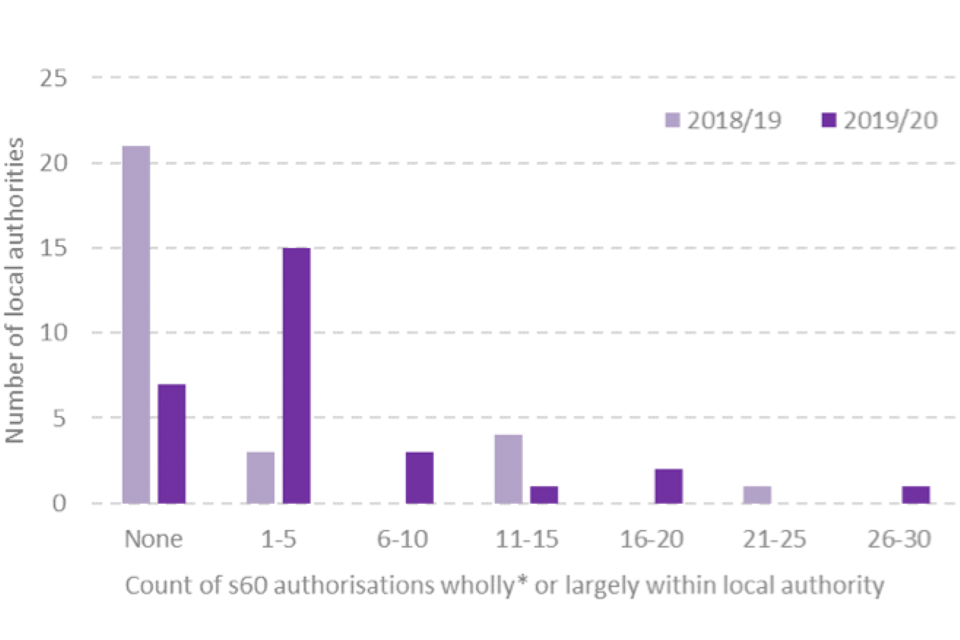

MPS analysis shows a high concentration of s60s in a small number of London boroughs. In the year ending March 2019, 1 borough had in excess of 126 authorisations using this measure. By contrast, there were 13 boroughs with fewer than 25 authorisations. In the year ending March 2020 the pattern shifted slightly and the number of high s60 authorisation boroughs increased with 4 boroughs having in excess of 126 authorisations.

Analysis on the relationship between locations of s60 authorisation boundaries and hospital admissions for ‘assault with a sharp object’ in London showed some correlation between sharp object assault admissions and s60 authorisations by local authority area. This shows that, to some degree, s60 authorisations are more common in boroughs where there are high knife crime admissions.

S60 ‘triggers’

The research team extracted detailed information from 143 authorisation forms supplied by 5 forces for the years ending March 2019 and March 2020. These data were drawn using opportunity-based sampling, which means that the findings cannot be generalised to all s60 stop and searches.

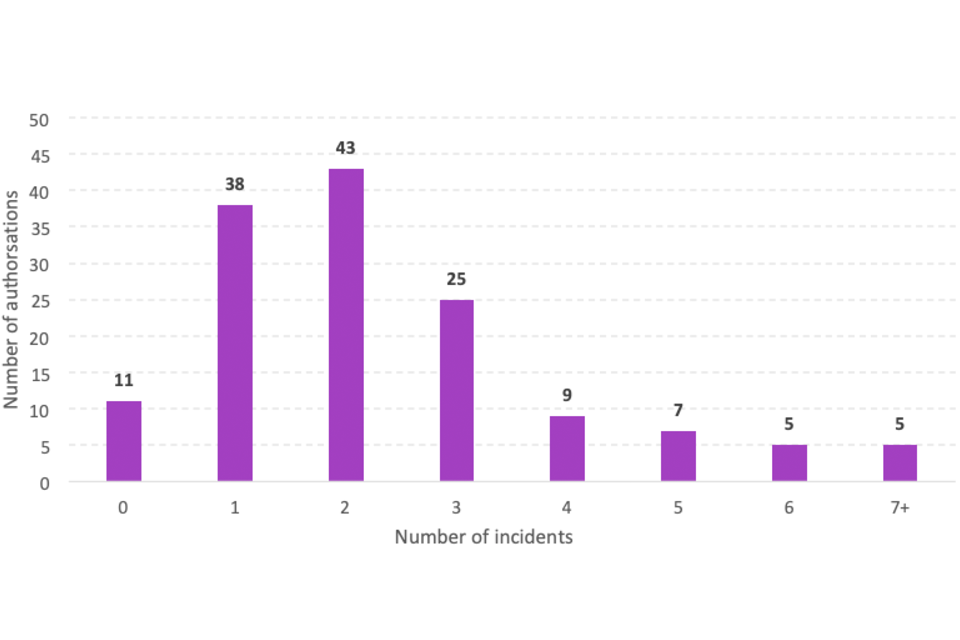

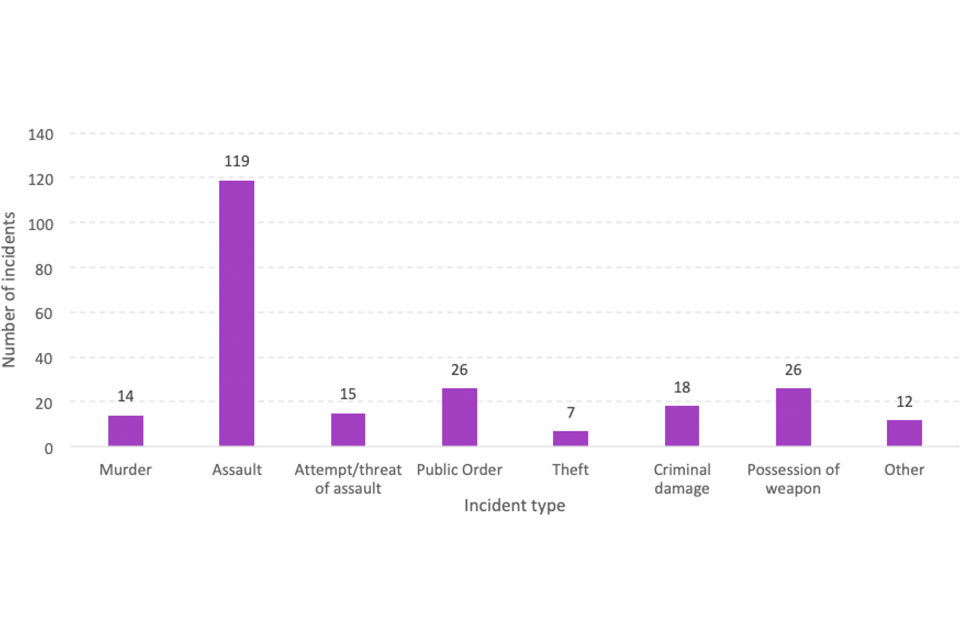

In total the authorisation forms made reference to 237 separate incidents that formed part of the decision to authorise (the term used here is ‘trigger incidents’). Typically, most forms cited 2 incidents, with at least one involving some type of assault. A minority cited a high number of incidents with 5 forms referencing 7 or more.

Almost all incidents that triggered a s60 involved some form of physical assault, and in a handful of cases, fatalities. Those authorisations that included reference to less serious offences – theft and weapons possession – were invariably included alongside more serious violence incidents or specific intelligence on potential future violence.

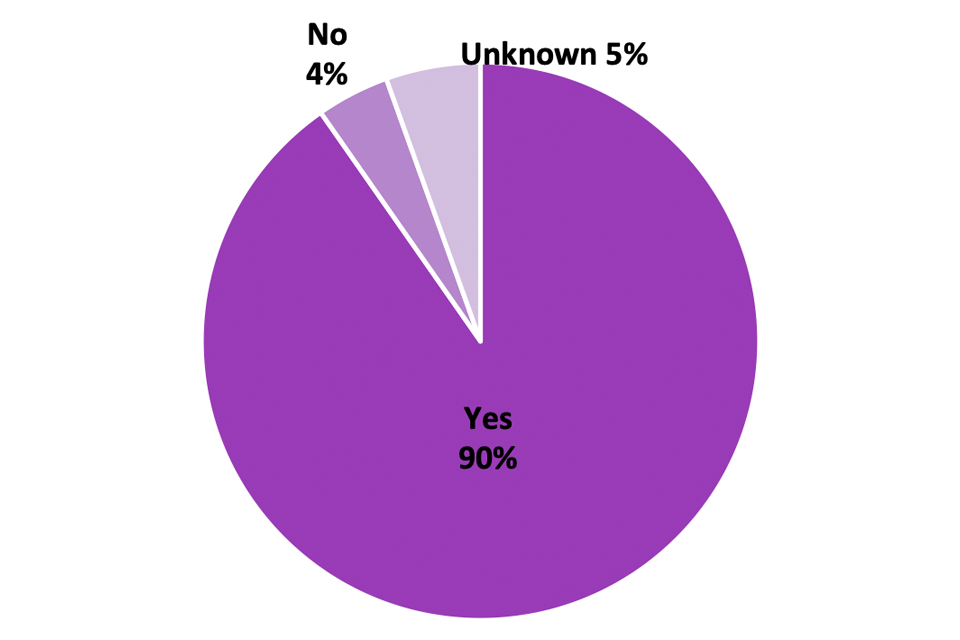

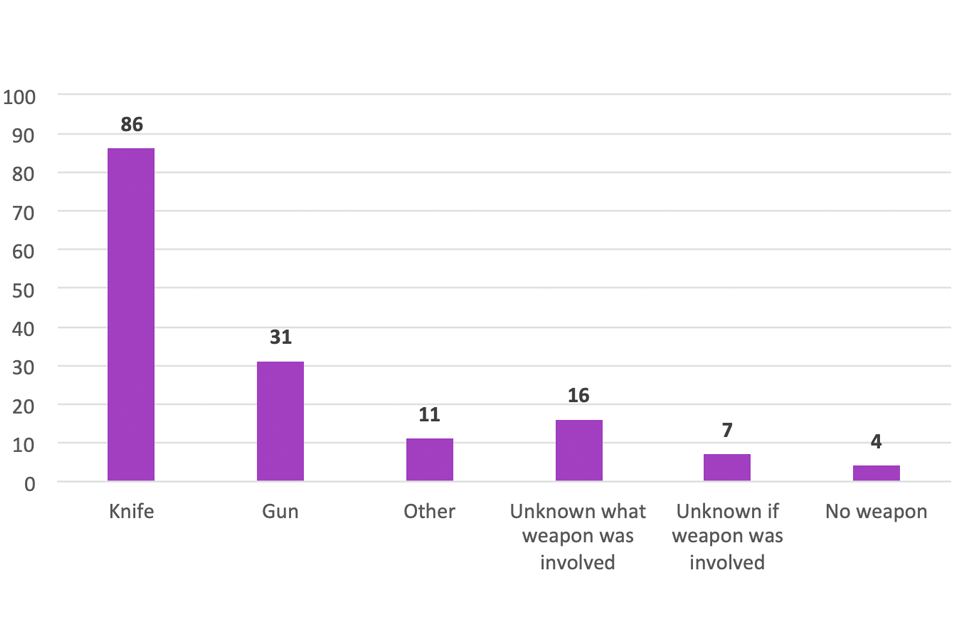

Almost 9 in 10 incidents described in the authorisation forms involved the presence or use of a weapon. Looking solely at murders, assaults and attempts or threats of assault, the most common weapon cited was a knife (59%) and over a fifth of identified weapons referred to were firearms.

This more detailed review of 143 authorisation forms suggested that, while incidents were frequently cited in the rationale for authorisations, they were often considered alongside relevant intelligence. Authorisations that relied solely on intelligence were rare within this sample – less than one in ten authorisations were intelligence-led with no specific reference to a prior incident.

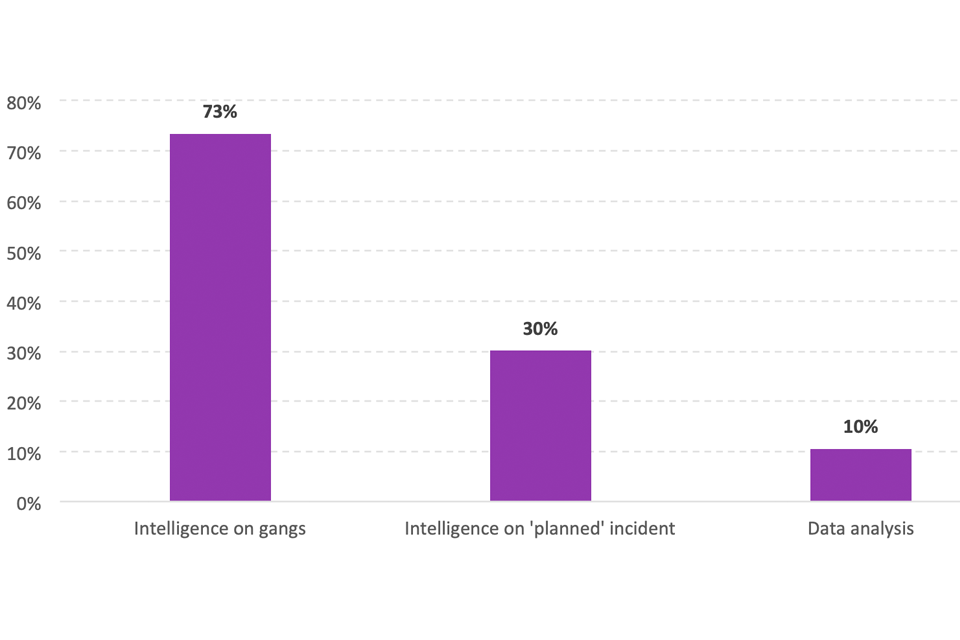

Around three-quarters of forms reviewed cited intelligence related to the nature of local gangs, and the rivalries between them. Less commonly recorded was intelligence on ‘planned’ incidents or violent encounters, such as intelligence that a group of people have arranged to fight at a specific time and location. A handful of authorisations also referenced the use of data analysis as a factor in their decision making.

S60 decision making

The 3 most commonly referenced alternative approaches to a S60 were:

-

searching under section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (s1) powers (which require specific grounds for suspicion of an individual)

-

dispersal orders

-

direct engagement with known offenders

These were considered as alternatives to s60 but sometimes were recommended as complementary measures.

Direct engagement with offenders manifested itself in a number of ways. Sometimes the approach was described in terms of simply arresting individuals where evidential thresholds could be met or making ‘home visits’ to actively dissuade them from being involved in future violence. A handful of references were made to longer term approaches to address serious violence, but the s60 was invariably considered as being necessary alongside this.

Just under half of the authorisation forms explicitly referenced community impact issues within their decision-making process, although both the specific concern, and the ‘community’, varied from form to form. Most commonly mentioned were references to the risk to the local community if the predicted serious violence took place.

Around one quarter of all forms mentioned the positive impact on public confidence that the secondary benefit of increased visible policing in the area would bring. The impact of searching individuals was mentioned less frequently in around one in ten forms.

The most commonly referenced direct community contact was with those who led on the scrutiny of stop and search, while a smaller number recorded approaching relevant MPs or local councillors. However, community contacts were generally informed about the authorisation rather than asked for their views on a s60 going ahead.

Concluding remarks

This report has drawn together data from a range of different sources to provide an insight into the s60 relaxations. The findings should be considered alongside the detailed qualitative report (Smith et al., 2023) covering police officers’ and community scrutiny leads’ views on the relaxations, and on s60 more widely.

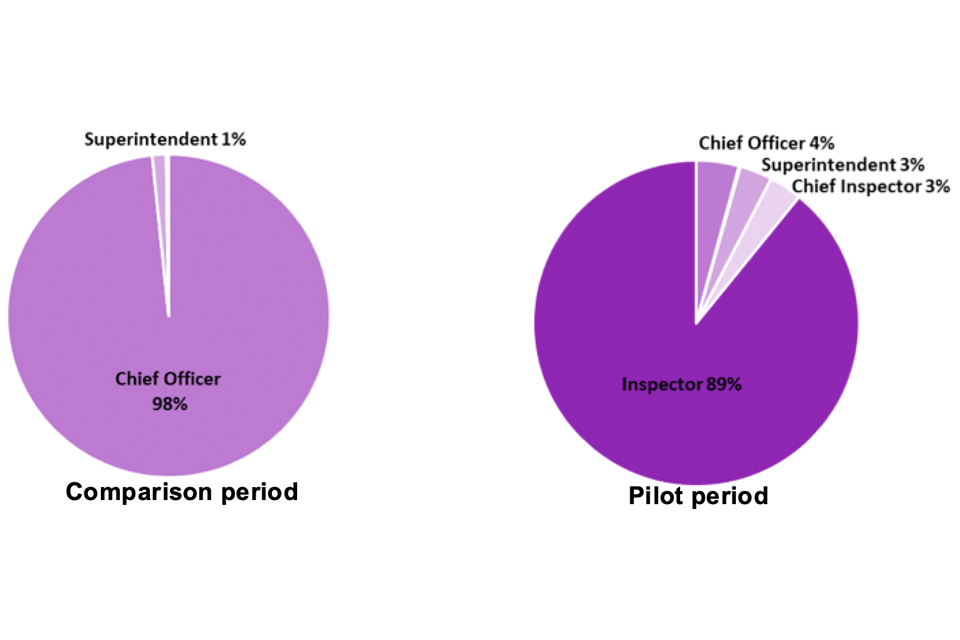

It is possible to say with confidence that the relaxations appear to have led to a marked change in the rank profile of authorising officers. There was little evidence of a marked change in the duration of authorisations or the use of extensions although ‘later’ forces appeared to adopt these more readily.

The August relaxation on communication of authorisations took away the requirement for s60s to be communicated with the public in advance. However, from the qualitative work it is clear that awareness of this relaxation was low, and most officers felt that the communication of authorisations was critical to their execution and served multiple purposes.

Across the pilot period s60 stop and search volumes went up by around a third. This was a smaller percentage increase compared to the more voluminous s1 stop and searches – up by over a half – which were unaffected by the relaxations.

Annual force-level data on s60 volumes show that use of s60 is fluid. Some forces did increase their use of s60 during the pilot period but others remained low or non-users. Implicitly, wider force-level policy over the use of s60s can change from year to year and, it is not possible to discount the impact of changes in serious violent crime volumes as a factor in driving s60 numbers. The period covered by the relaxations also sees the introduction of the Serious Violence Fund in the financial year 2019 to 2020. This combination of factors makes any assessment of the impact of the relaxations on s60 volumes challenging, particularly given the all-encompassing coverage of the pilot from August 2019.

The qualitative analysis also provides some useful insights into the way that officers reacted to changes in the conditions that permit the use of s60 over time. The individual relaxations may play some part in encouraging the more frequent use of the power, and the near universal shift to inspector-level authorisation looks by far the most influential change. However, the interviews imply that what may be more critical is the wider messaging that the relaxations convey, by instilling greater confidence in the use of the power (Smith et al., 2023).

The qualitative and quantitative research was undertaken to help to inform the decision around the pilot relaxations in the use of s60 authorisations. In addition however, it has also shown how police forces have opted to institute internal review mechanisms alongside the lowering of the authorising rank. The extent to which all forces have an accurate overall picture of their use of s60 is less apparent. To build on this, regular reporting on the distribution of s60s in both time and in individual neighbourhoods would appear to be a useful additional component of internal force-level monitoring and review.

1. Introduction

On 31 March 2019 the Home Secretary announced that 2 relaxations to the Best Use of Stop and Search Scheme (BUSSS) would be piloted in 7 police force areas: Greater Manchester Police (GMP), Merseyside, Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), South Wales, South Yorkshire, West Midlands, and West Yorkshire (Home Office 2019a). The relaxations were announced to enable the police to respond more effectively to anticipated incidents of serious violence using section 60 (s60) stop and search and involved:

-

reducing the level of initial authorisation needed to impose a s60 stop and search power in a defined area from chief officer level down to an officer of or above the rank of an inspector (Table 1.1)

-

reducing the degree of certainty needed for an authorising officer to impose a s60 from believing an incident involving serious violence ‘will’ occur, to ‘may’ occur

Table 1.1: Officer rank structure

| UK forces | Metropolitan Police Service | City of London Police |

|---|---|---|

| Chief Constable | Commissioner | Commissioner |

| Chief Constable | Deputy Commissioner | Commissioner |

| Deputy Chief Constable | Assistant Commissioner | Assistant Commissioner |

| Deputy Chief Constable | Deputy Assistant Commissioner | Assistant Commissioner |

| Assistant Chief Constable | Commander | Commander |

| Chief Superintendent | Chief Superintendent | Chief Superintendent |

| Superintendent | Superintendent | Superintendent |

| Chief Inspector | Chief Inspector | Chief Inspector |

| Inspector | Inspector | Inspector |

| Sergeant | Sergeant | Sergeant |

| Constable | Constable | Constable |

Note:

- This rank table is only indicative of the hierarchy within each police force.

All other conditions remained as outlined in BUSSS. In this report these changes are referred to as the ‘April’ (2019) relaxations. Following this, in August 2019 the current Home Secretary extended the pilot to all 43 police forces and the British Transport Police (BTP) (Home Office 2019b). The extended pilot relaxed all conditions placed by BUSSS on s60 stop and search powers. This meant that in addition to the 2 conditions relaxed above:

-

inspector authorisations could now last a full 24 hours (as opposed to 15 hours)

-

superintendents could now extend an authorisation beyond 24 hours to 48 hours (BUSSS required this to be done at chief officer level, and limited extensions to a total of 39 hours)

-

s60s do not need to be communicated to the public in advance

For the relaxations that came into force in April and August, it remained an operational decision for each police force as to how they were implemented, and which policies were put in place. Therefore, at police force level they could adapt any of the relaxations or continue with the conditions outlined in BUSSS. At the time of writing the pilot conditions remain relaxed. Figure 1.1 sets out a timeline for the introduction of BUSSS and the relaxations. It also covers the introduction of the Serious Violence Fund – the link with the s60 relaxations is covered in Chapter 3.

Figure 1.1: Timeline of BUSSS, relaxations for s60, and surge funding

A timeline showing the changes made to section 60 guidance between April 2014 and August 2019. In April 2014, the Best Use of Stop and Search scheme (BUSSS) was introduced. In March 2019, 2 relaxations to these conditions were piloted in 7 forces. In April 2019, the serious violence fund was introduced which allocated 65 million pounds to the 18 forces in the UK with the highest share of knife related injuries. The increase in spending helped drive more stop and search. In August 2019, the BUSSS was relaxed further, returning most conditions to the pre-2014 arrangements and extended to all forces.

1.1 Background

‘Stop and search’ typically refers to the statutory police powers to stop and physically search an individual. Most types of stop and search need to be justified by ‘reasonable suspicion’. This is usually based on intelligence or the belief that the search will uncover a specific illegal activity, or the possession of a prohibited or an illegal item. However, some legislation allows stop and searches without reasonable suspicion when terrorism, football-related disorder or other forms of violence is anticipated (McCandless et al., 2016). This report focuses on s60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, which allows a stop and search within an authorised locality without reasonable suspicion when violence is anticipated.

Following a period of relatively high use of stop and search, a series of reports and reviews into stop and search were published that raised questions about its effectiveness and use, such as the Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) 2013 report. This contributed to a 99% drop in s60 use from around 150,000 in the year ending March 2009 to 1,061 in the year ending March 2015. In 2014 the Government committed to do more to improve stop and search and introduced new reforms to make stop and search fairer and more effective, including the introduction of BUSSS (Home Office, 2014). BUSSS was introduced in 2014 to increase transparency, foster community involvement, improve outcomes and to capture the outcomes of searches in greater detail. The following changes to help to achieve these aims were made.

-

increased data recording: recording a broader range of stop and search outcomes and the link between the object of the search and its outcome

-

policies allowing lay observation of stop and search and a community complaints trigger – a local complaint policy requiring that the police ensure that the individuals who are stopped and searched are aware of where to complain. A threshold was also introduced above which the police are compelled to explain their use of stop and search and provide that explanation to local community scrutiny groups

-

measures aimed at reducing s60 searches were:

- raising the level of authorisation from an officer of or above the rank of inspector to chief officer[footnote 7]

- the authorising officer must reasonably believe that serious violence ‘will’ take place rather than it ‘may’ take place

- limiting the duration of initial authorisations to no more than 15 hours (down from 24 hours)

- ensuring that s60 stop and search is only used where it is deemed necessary

- communicating to local communities when a s60 authorisation is in place

Force participation was voluntary but BUSSS compliance was considered in a HMIC inspection in 2015 (HMIC, 2015). This inspection led to 13 police forces that were deemed to be the least compliant being suspended from the BUSSS scheme and a further 19 being put on notice. By November 2016 the suspended forces were readmitted after further inspection and most of the forces put on notice were found to be compliant.

Following the introduction of the BUSSS scheme, s60 stops fell further to only 631 in the year ending March 2017 (Home Office, 2020). At this time there were growing concerns around increases in serious violence, and with it, expectations that the police would take stronger action to tackle it, including the more widespread use of stop and search powers. S60 use increased in the year ending March 2018 to 2,503, but this was still at historic lows (Home Office, 2020). The police argued that the conditions as set out in BUSSS were too bureaucratic and needed to be relaxed for them to better tackle serious violence. The Government announced the initial pilot relaxations in March 2019, but further extended both coverage and the breadth of the relaxations in August 2019.

In the year ending March 2020, police in England and Wales carried out 18,081 stops and searches under s60 authorisations[footnote 8], an increase of 35% (4,666 searches) on the previous year. This is the third consecutive annual increase and follows a substantial increase between the years ending March 2018 and March 2019, when the use of s60 stop and searches increased more than fivefold, from 2,503 to 13,415 searches. The increase in the year to March 2020 was driven by a handful of police forces, notably, the MPS, which accounted for 39% of the increase, followed by Essex (which accounted for 18% of the increase) and Merseyside (17% of the increase). As in previous years, most s60 stops took place in London, with the MPS accounting for around two-thirds (63%) of all s60 searches in England and Wales, followed by Merseyside (7%), and the BTP and Essex, both accounting for 5% of s60 searches (Home Office 2020). In spite of the most recent increases, s60s still only account for 3% of all stop and searches. Stops under section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (s1) – which require reasonable grounds for suspicion – are far more common (558,973 in the year ending March 2020).

1.2 Aims of this report

This report summarises a range of quantitative data on the operation of s60 during the first year of the pilot. The analysis is designed to complement the linked qualitative study based on interviews with officers and community scrutiny leads to gain their views of the relaxations introduced as part of the pilot (Smith et al., 2023). The quantitative data summarised in this report are designed to describe in more detail the pattern of s60 authorisations and resultant searches in the year ending March 2020 and, where possible, to make comparisons with data from the previous year. For a small sample of s60s, the analysis also includes an in-depth assessment of the authorisation forms on which decisions to agree s60s were made and examines the incidents and intelligence that typically precede an authorisation. Where there are sufficient data, the analysis seeks to draw out any differences between those authorisations conducted before the pilot and those since it began.

The main aims of the analysis were:

-

to describe the nature and pattern of s60 authorisations undertaken during the year ending March 2020 across England and Wales and observe any trends over recent years

-

for a subset of police forces, to examine in more depth any changes in authorisations between the years ending March 2019 and March 2020, including the rank of authorising officer, the length of authorisation and geographical coverage

-

to improve understanding of how s60s were communicated to the public via social media, how often this was done and if so, whether this was before, during or after the authorisation was put in place

-

to identify and describe what types of incidents typically precede a s60 authorisation and better understand what factors are considered in s60 authorisation decisions

As the analysis does not describe the findings of an ‘experiment’, it is not able to assess – in almost all instances – whether any changes identified in the year ending March 2020 were directly the result of the relaxations.

1.3 Report structure

Chapter 2 summarises the main data sources and methods. Chapter 3 summarises bespoke data collected from all 43 police forces and the BTP covering the pilot period. This examines broader patterns of s60 use in the year ending March 2020, such as the number of authorisations by length and rank along with the number of searches carried out and their outcomes.

Chapter 4 focuses on the relaxations by examining the more detailed administrative dataset collected from 6 forces for both the year ending March 2019 and the year ending March 2020 and supplemented by the bespoke dataset. In addition to comparing across the 2 years, it explores in more detail the profile of authorisations (for example, the rank of officer authorising the s60, timings and extensions). Chapter 5 analyses Twitter data to examine if and how s60s are communicated to the public. Chapter 6 looks at the number of searches per authorisation and the time of day that authorisations were put in place. Chapter 7 explores the geographical coverage of s60 authorisations.

Chapter 8 looks at a subset of this 6-force dataset, based largely on an analysis of s60 authorisation forms, to consider the types of ‘trigger’ incidents that preceded a s60 and the use of intelligence. Using the same data, chapter 9 examines the factors that police officers considered when making the decision to authorise a s60. Finally, chapter 10 provides concluding remarks.

2. Methodology

2.1 S60 bespoke data collection exercise

A bespoke section 60 (s60) statistical data collection exercise was carried out with all 43 territorial police forces in England and Wales, and the British Transport Police (BTP). The period covered by these data was 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020 for the ‘original’ 7 forces that joined the pilot on 1 April 2019. For the remaining ‘later’ forces that joined on 12 August the pilot period covers 12 August 2019 to 31 March 2020. For every s60 authorisation, forces were asked to submit data on:

-

the rank of the authorising officer

-

free text to explain the rationale and location of the authorisation

-

start date and length of the authorisation

-

the number of individual searches resulting from the authorisation

The free text for the rationale for the authorisation was then reviewed and coded by analysts into one of 4 categories: ‘following an incident’, ‘event’, ‘intelligence’, ‘other/unknown’.[footnote 9]

Forces were also asked to complete information on: the self-defined ethnicity of any person searched, the outcome of each search; and whether a knife or sharp instrument was found in the search.

A data reconciliation exercise designed to flag and resolve data quality issues was carried out with all police forces prior to the publication of this report. This included summarising forces’ returns into data tables, highlighting missing values, and querying unusual data, such as large increases in the use of s60 or lengthy authorisation periods. Data collected for this work have also been cross-referenced with stop and search data collected for the National Statistics Police powers and procedures, year ending March 2020 (Home Office, 2020) publication, to ensure that, where applicable, totals were consistent across both data collections.[footnote 10]

For a range of reasons, it has not been possible to link all s60 stop and searches to a specific authorisation. In particular, the data system used by the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) does not link stop and searches to authorisations, so the 2 sets of data were provided separately. However, analysts ran an exercise to link MPS searches to an authorisation based on the date of the search and the London borough in which the stop and search and authorisation took place (resulting in 10,075 links). Where these attempts to link failed, analysts tried to link to an authorisation based on the day before and the day after the date of the search. This resulted in a further 327 stop and searches being linked, bringing the total linked stop and searches to 10,402 (91% of all MPS stop and searches analysed).

Additionally, there are further instances where s60 stop and searches have been carried out by an officer from one police force, but the authorisation has been made by another force. This is particularly the case for the BTP, which carried out 234 searches in the pilot period on behalf of a territorial police force. In these cases, the search was recorded against the searching officer’s police force and will not be linked to an authorisation.

2.2 Additional s60 authorisation data from 6 forces

In addition to the data collected for all police forces, 6 relatively high use forces were identified in the qualitative study (Smith et al., 2023) that were able to provide more granular data on authorisations in the years ending March 2019 and March 2020. These data were drawn from authorisation forms and forces’ administrative systems and are hereafter referred to as the 6-force dataset. Whilst care has been taken to ensure consistency between the national dataset and the 6-force dataset, data collection methods differed therefore some small inconsistencies may be present. Due to coronavirus (COVID-19) pressures some forces initially approached were not able to commit resources to the work. In these cases, forces with the next highest number of s60 searches were approached as alternatives. The following 6 police forces made up the final sample: Merseyside, the MPS, and West Midlands – which were part of the ‘original’ pilot from April 2019 – and the BTP, Kent and Cheshire, – which joined the pilot in August 2019. These 6 forces together account for 83% of all authorisations during the pilot period.

Scoping work identified a core dataset from the 6 forces on their authorisations for both the pilot period (year ending March 2020) and the preceding year (year ending March 2019). These data covered the rank of officer who authorised the s60, the date and start time of the s60, and the length and location of the authorisation. The geographical information was used to generate digital maps and calculate the size of the geographical area covered by the authorisation.

These authorisations were reviewed against 650 relevant police force Twitter accounts. Twitter was chosen to examine public communication following discussions with the police forces, because it was felt to be one of the most commonly used forms of social media for sharing information on authorisations. Analysing these data allowed the analysts to identify whether the s60s covered by the time period in this study had been communicated via Twitter to the public. The data collected included the Twitter account, the date and time stamp of the tweet, the text posted and any images, such as maps contained in the tweet.

However, Twitter is just one of a number of channels that police forces can use to communicate with the public, therefore all communications of s60 authorisations will not have been captured.

Finally, information was retrieved and coded from a selection of 143 s60 authorisation forms from 5 of the forces across the 2 years. The method of collection and coverage varied by police force, due to factors such as their volume of searches. The forms included:

-

information on what evidence had been considered when making the authorisation decision

-

the incidents that preceded an authorisation

-

what other tactics had been considered instead of, or in addition, to the s60

-

how intelligence or data informed their decision making

-

the possible impact on the community

These data were drawn using opportunity-based sampling, which means that the findings cannot be generalised to all s60 stop and searches (see Appendix A for further details).

The composition, coverage and analysis of these datasets are described in more detail in Appendix A.

2.3 Quality assurance and governance

The information that police forces extracted from their administrative datasets were compared with other sources (for example, authorisation forms where appropriate) and any discrepancies were resolved with the force. The qualitative coding of authorisation forms underwent a quality assurance process, with the coding and categorisation reviewed by a second researcher to ensure consistency.

To provide governance to the research, a Steering Group consisting of representatives from the College of Policing, Cabinet Office Race Disparity Unit and HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services was established. The group was asked to give views on the direction of the project, the research tools and methodology, and met at key stages during the research.

3. Statistical overview of the s60 pilot

This chapter provides a statistical overview of the use of section 60 (s60) across the 43 territorial police forces in England and Wales, and the British Transport Police (BTP). The main focus is on the pilot period but it also describes the long-term use of s60, drawing on both the bespoke data collection and the annual statistical bulletin.[footnote 11]

National Statistics on the use of s60, as well as other police powers (including searches under section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (s1)), are published annually in the Police powers and procedures’ statistical bulletin (Home Office, 2020). While every effort has been made to reconcile figures between the 2 publications, there may still be some small discrepancies due to the nature of the administrative datasets being queried, and the different times at which the data were extracted from the systems. Furthermore, data in the annual publication provides data for the full year, whereas data in this chapter relate to searches and authorisations conducted within the pilot period only.

3.1 Historic patterns of s60 use

On 27 October 2020, the Home Office published the annual Police powers and procedures (2020) statistical bulletin. This release contains information on the number of searches conducted under s60 since the year ending March 2002.

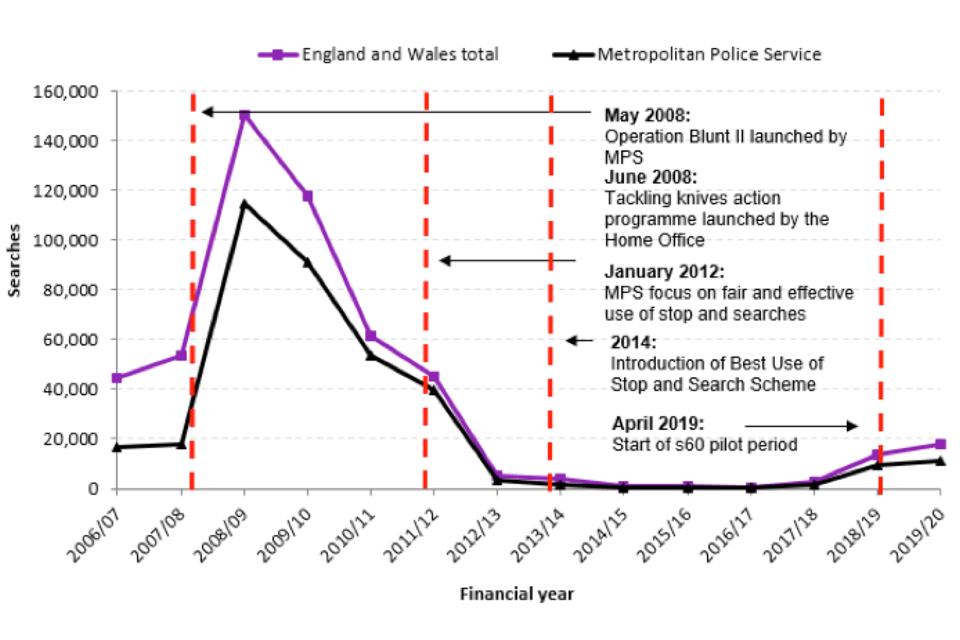

Figure 3.1 below shows that the use of s60 fell substantially between the year ending March 2009 and the year ending March 2013, from around 150,000 searches a year, to 5,000. In the years ending March 2016 and March 2017 the number of searches under this power was just 970 and 631 respectively, with the majority of these searches being conducted by the MPS. Since the year ending March 2017, the number of searches conducted under s60 has continued to rise, to 18,081 searches in the year ending March 2020. Of these, 17,267 (95%) were conducted during the pilot period.

Figure 3.1: Stop and searches under s60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, England and Wales,1 years ending March 2007 to March 2020

A graph showing the number of stop and searches from the year ending March 2007 to year ending March 2020. There is a sharp increase from the year ending March 2008 to a peak in the year ending 2009 followed by a steep decline until the year ending March 2013. Since the year ending March 2018 there has been a slight increase. S60 stop and searches by the MPS drive this trend.

Source: Police powers and procedures (2020), Home Office, 2020.

Note:

- Data from the year ending March 2010 onwards include the BTP. Prior to this, data are not directly comparable with more recent years.

While it is not a ‘pure’ comparison – due to the additional forces that joined the pilot in August 2019 – comparing the pilot period[footnote 12] with the full previous year shows a 29% increase in the number of s60 searches across England and Wales. This compares with a 52% increase in the more voluminous s1 stop and searches (not shown) in the year ending March 2020.[footnote 13]

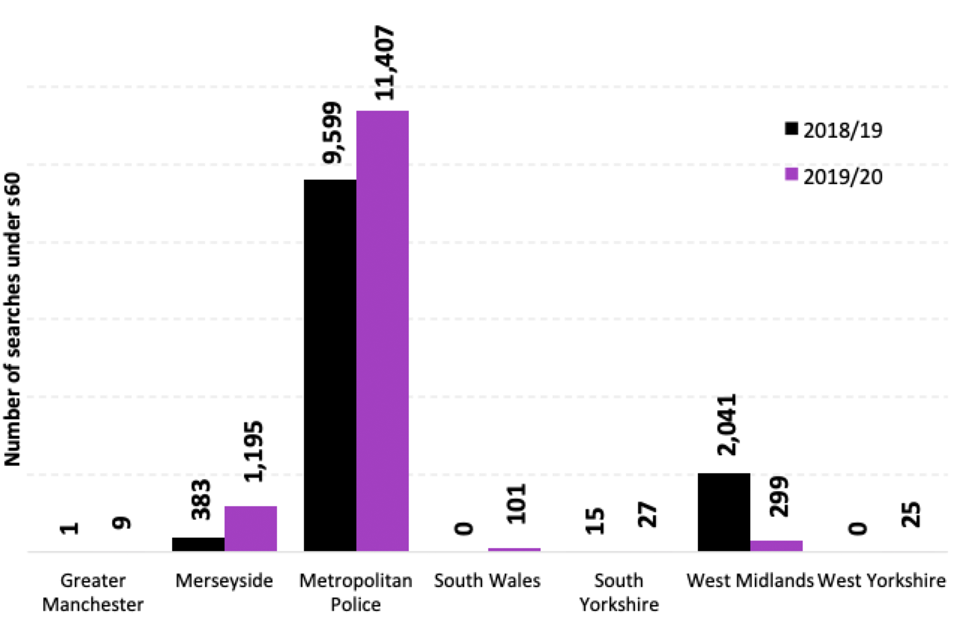

Looking solely at the 7 ‘original’ forces allows a true year-on-year comparison. In this case, there was a 9% increase across the 2 years, but the pattern varied across forces. The MPS, the largest user of s60s, recorded a 19% increase during the pilot, whereas Merseyside showed a threefold increase (383 to 1,195). Small volume increases in s60 searches were recorded for GMP, South Yorkshire, West Yorkshire and South Wales. However, West Midlands recorded an 85% fall in use over the period (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2: Changes in the use of s60, ‘original’ 7 pilot forces, years ending March 2019 and March 2020

Bar chart showing changes in section 60 use between years ending March 2019 and March 2020 for 7 forces. All forces apart from the West Midlands have increased their use. The Met police are clearly the biggest users of S60.

It is not possible to assess the extent to which the relaxations may have directly or indirectly contributed to the increase in s60s during the pilot. This is partly because the pilot was rolled out in a way that made it difficult to explore any discrete pilot effect on search volumes. The pilot also overlapped with another initiative that might be expected to contribute to an increase in the use of s60s. As part of the drive to combat serious violence, the Treasury agreed to allocate £100m of additional funding to forces for the financial year ending March 2020 to help to tackle the problem, with the majority (£63.4m) allocated to ‘surge policing’.[footnote 14] This was largely expected to increase activity using the officers already employed, rather than to significantly increase officer numbers. The fund provided additional resources for the 18 police forces in England and Wales with the highest share of knife injury admissions to hospital, with force allocations scaled to reflect admission volumes. These 18 forces accounted for 86% of the total increase in s60 stop and searches between the years ending March 2019 and March 2020 (4,008 of an additional 4,666 searches).

Despite this, force-level changes in s60 searches during the year ending March 2020 amongst the ‘18’ are far from uniform (Table 3.1). Amongst forces receiving surge funds that joined the pilot in August, one (Kent) recorded large increases in s60s heavily concentrated during the pilot period. Others recorded marked uplifts in s60 searches in both the year ending March 2020 pre-pilot period and the pilot period itself (Essex, Lancashire and to a lesser extent, Hampshire and Sussex). Other forces recorded no use of s60 at all in the year ending March 2020 regardless of relaxations and access to surge funding (Bedfordshire, Leicestershire, Northumbria and Nottinghamshire). Conversely, 8 police forces that were not part of the ‘18’, did record higher numbers of s60 searches during the later pilot compared with the year ending March 2019.[footnote 15] In short, the combination of the pilot relaxations and funding enhancements during the year ending March 2020, on top of forces’ variable use of s60, make assessing the impact of relaxations alone on s60 volumes very challenging.

Table 3.1: S60 stop and searches, 18 forces receiving serious violence funding, year ending March 2019, year ending March 2020 and pilot period

| Police force | year ending March 2019 | year ending March 2020 | year ending March 2020 – pilot period only1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avon & Somerset | - | 1 | - |

| Bedfordshire | 1 | - | - |

| Essex | 41 | 873 | 601 |

| Greater Manchester | 1 | - | 9 |

| Hampshire | - | 279 | 230 |

| Kent | - | 586 | 584 |

| Lancashire | 236 | 357 | 197 |

| Leicestershire | 11 | - | - |

| Merseyside | 383 | 1,195 | 1,195 |

| Metropolitan Police | 9,599 | 11,412 | 11,407 |

| Northumbria | 1 | - | - |

| Nottinghamshire | 21 | - | - |

| South Wales | - | 101 | 101 |

| South Yorkshire | 15 | 27 | 27 |

| Sussex | 11 | 524 | 482 |

| Thames Valley | 1 | 674 | 665 |

| West Midlands | 2,041 | 316 | 299 |

| West Yorkshire | - | 25 | 25 |

| Total | 12,362 | 16,370 | 15,822 |

Source: Table 2 and ‘Police powers and procedures (2020)’ statistical bulletin, Home Office.

Note:

- Greater Manchester Police, Merseyside, Metropolitan Police Service, South Wales, South Yorkshire, West Midlands, and West Yorkshire were placed under pilot conditions from 1 April 2019. The remaining police forces were placed under pilot conditions from 12 August 2019.

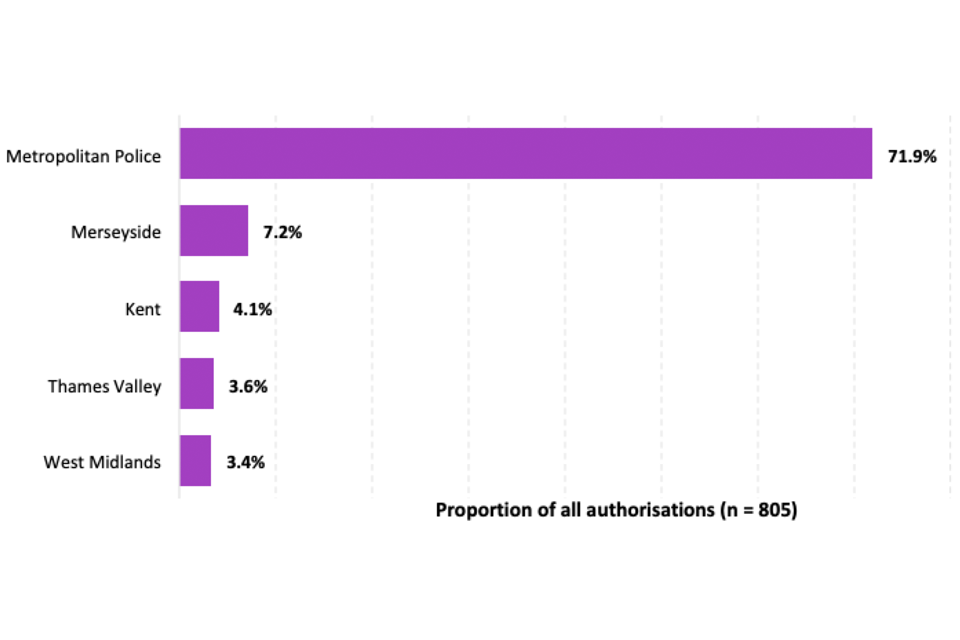

3.2 Authorisations

As part of the bespoke data collection, information on s60 authorisations was collected for the first time. The data show that during the pilot period a total of 805 authorisations were put in place (excluding Lancashire, who were unable to provide information on authorisations). The MPS accounted for almost three-quarters of these authorisations (579, 72%), followed by Merseyside (58, 7%). Just 5 forces accounted for 90% of all authorisations during the pilot period, and also accounted for 82% of the resultant searches. Of the 19 forces that did not conduct any searches under s60 in the year ending March 2019, 8 conducted at least 1 search during the pilot period.

Figure 3.3: Authorisations, by police force area, top 5 forces, pilot period

A bar chart showing the use of section 60 over the pilot period for the highest using forces. The MPS account for 72% of all authorisations.

Source: Table 3.

3.3 Grounds for authorisation

As part of the data collection, police forces provided information on the grounds for the authorisation, or the events that led to the authorisation being put in place. This information was received as free text, and then coded by analysts into one of the following categories.[footnote 16]

Following an incident or incidents: This category was used where the free text contained information on one or more specific incidents that happened prior to the authorisation being put in place. Often this included cases where serious violence had already occurred, and an authorisation was put in place to deter further acts of violence.

Intelligence: Authorisations fell into this category where the free text explanation mentioned having specific intelligence that serious acts of violence may take place. For example, where intelligence had been received that gangs were planning to meet.

Event: Where authorisations mentioned a specific event (pre-planned or otherwise), they were coded under this category. Examples included: festivals and carnivals; private parties; and funerals of gang members.

Other/not known: This category was used for all cases where there was either no explanation given, or where the explanation did not fall into any of the categories listed above.

Mixed categories: In many cases, the grounds for the authorisation fell into more than one of the above categories. These were therefore coded as mixed across 2 or more categories. For example, in cases where serious violence had already taken place (for instance, a stabbing), and the police then received intelligence of a planned retaliation attack, the authorisation would be coded as ‘Mixed – Incident/Intelligence’. Three other ‘mixed’ categories were also generated.

The data show that the majority of authorisations were put in place following an incident, or previous act of serious violence (Figure 3.4). Authorisations that followed an incident were the single biggest category (413, 51%). Authorisations that had a mixture of grounds including incidents accounted for an additional 198 authorisations so that in total, 76% of authorisations referred to some kind of previous incident. Intelligence-only authorisations were rare (13%) and event-only authorisations were the least common.

Figure 3.4: Grounds for authorisation, pilot period

A bar chart showing the number of s60 authorisations by the grounds for their authorisation. The most frequent grounds for an authorisation was following an incident (413).

Source: Table 6.

3.4 Resultant searches

As part of the bespoke data collection, police forces were requested to link searches under s60 powers to the specific authorisation put in place. However, for a range of reasons, it was not possible to link all s60 searches to a specific authorisation.

In particular, the data systems used by Lancashire and the MPS record searches and authorisations separately. Consequently, an automatic link between a particular search and authorisation was not possible. Lancashire therefore provided data for searches only, and could not provide data on authorisations. However, given the large number of s60 authorisations and searches conducted by the MPS, both datasets were provided, and analysts ran an exercise to link MPS searches to an authorisation based on the date of the search and the London borough in which the search and authorisation took place.

In total 10,075 of the 11,407 searches conducted by the MPS were linked through this process. Where these link attempts failed, analysts relaxed the need to link on time, and instead linked only on the borough and date of the search. This resulted in a further 327 searches being linked, bringing the total linked searches to 10,402 (91%). Where a search could be linked to multiple authorisations, and analysts were unable to specify which, a link was not made.

Additionally, there were further instances where s60 searches had been conducted by officers in the BTP, but the authorisation was put in place by a territorial police force. In these cases, the search had been recorded against the searching officer’s force (BTP), and will not be linked to an authorisation. Table 3.2 summarises the magnitude of the issues.

Table 3.2: Number and proportion of searches that are linked/not linked to an authorisation

| Number of searches | % | |

|---|---|---|

| All searches conducted in pilot period | 17,267 | 100% |

| Linked searches | ||

| Data provided linked | 5,429 | 31% |

| MPS searches linked using date and borough records | 10,402 | 60% |

| Total linked | 15,831 | 92% |

| Not linked searches | ||

| MPS | 1,005 | 6% |

| Lancashire | 197 | 1% |

| BTP | 234 | 1% |

| Total not linked | 1,436 | 8% |

Where data quality issues exist, these are included in the relevant Excel data tables that accompany this report.

Findings related to the number of searches are given in Chapter 6.

3.5 Outcomes following a search

These data include the initial outcome given following the search only. The data show that the vast majority of s60 searches conducted during the pilot period (91%) resulted in ‘no further action’ (using the Best Use of Stop and Search Scheme BUSSS framework. ‘No further action’ can include a wide range of scenarios. It is therefore possible, for example, that in some cases, an outcome of ‘no further action’ could be given if an officer finds something but decides not to deal with it through formal means (arrest, cannabis/khat warning, caution, community resolutions or a penalty notice for disorder). Only 9% of searches resulted in an arrest or some type of disposal (1,471). Where there was an arrest or other outcome, 46% resulted in an arrest, and a further 34% in a community resolution. The arrest rate for all s60 searches conducted in the pilot period was 3.9% (4.7% in the year ending March 2019).

Figure 3.5: Principal outcome ‘no further action’, and any other outcome, pilot period

A pie chart showing the breakdown of outcomes following a search under section 60. 91% of all section 60 searches result in no further action.

Source: Table 11.

Note:

- Excludes 4 searches where the outcome was not stated.

Figure 3.6: Principal outcome, other than no further action, following a s60 search, pilot period

A bar chart showing a breakdown of the other outcomes of a section 60 search, excluding no further action. The majority of searches that result in an action end in an arrest or a community resolution.

Source: Table 11.

For the 17,025 searches for which it was known whether or not a knife was found (99% of all searches), a knife was found in 1.0% of searches. This is similar to the annual Police powers and procedures (2020) statistical bulletin where a knife or sharp instrument was found in 1.4% of searches in the full year ending March 2020 financial year (1.6% in the year ending March 2019 ).

This statistical bulletin provides these data for previous years.

3.6 Ethnicity of those searched

Data were provided by all police forces on the self-defined ethnicity of the person being searched. However, when the data were first received, analysis indicated that almost one in four (24%) of searches were recorded with a ‘not stated’ ethnicity. This was explored further with the MPS and it was found that for 75% of the cases where the self-defined ethnicity was not recorded (30% of all searches) the reason was that the person being searched had declined to state their ethnicity (2,551 of the 3,423 cases where the self-defined ethnicity was not recorded).

Given that the MPS[footnote 17] account for a sizeable share of the data, MPS analysts ran a second exercise and, where the self-defined ethnicity of the person was not recorded (30% of cases), the ethnic appearance of the individual as recorded by the searching officer was used. Table 3.3 and table 3.4 summarise the impact of doing so on the figures.

Table 3.3: Ethnic appearance as recorded by the searching officer, where the self-defined ethnicity of the individual was not stated, MPS only, pilot period

| Number of searches | % | |

|---|---|---|

| MPS search total | 11,407 | 100% |

| Of which, number of searches where the self-defined ethnicity is ‘not stated’ | 3,423 | 30% |

| Of which, number of searches where the self-defined ethnicity is known | 7,984 | 70% |

| Where self-defined ethnicity is ‘not stated’, officer perceived ethnic appearance recorded | 3,423 | |

| White | 571 | 17% |

| Black (or Black British) | 2,012 | 59% |

| Asian (or Asian British) | 374 | 11% |

| Chinese and Other | 274 | 8% |

| Mixed | - | 0% |

| Not stated | 192 | 6% |

| Total | 3,423 | 100% |

Table 3.4: Impact of recoding MPS ethnicity data, all forces, pilot period

| Initial data received | Initial data received | Data following MPS recoding | Data following MPS recoding | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| White | 6,053 | 35% | 6,624 | 38% |

| Black (or Black British) | 4,578 | 27% | 6,590 | 38% |

| Asian (or Asian British) | 1,555 | 9% | 1,929 | 11% |

| Chinese and Other | 372 | 2% | 646 | 4% |

| Mixed | 522 | 3% | 522 | 3% |

| Not stated | 4,187 | 24% | 956 | 6% |

| Total | 17,267 | 100% | 17,267 | 100% |

This resulted in 16,311 of the 17,267 (94%) searches conducted in the pilot period having an ethnicity recorded against them. Further details on the reason for a ‘not stated’ ethnicity were not collected from other police forces, so a similar exercise could not be repeated for those forces. However, since the MPS accounts for two-thirds of searches in the pilot period it is expected that the impact of recoding ethnicity data in other forces would be minimal.

Table 3.5 shows the revised figures for the pilot period, and a comparison to the year ending March 2019.[footnote 18] In the pilot period, and excluding cases where the ethnicity was not known, 41% of searches were of people who either self-identified as White or, in the MPS where the self-defined ethnicity was not stated, the officer recorded the person’s ethnic appearance as White. A similar proportion (40%) of searches were conducted on those who either self-identified as Black, or the officer recorded their ethnic appearance as Black. This was followed by the Asian group (12% of searches), the Chinese and Other ethnic group (4% of searches), and the Mixed group (3% of searches).

Table 3.5: Ethnicity of persons searched under s60, year ending March 2019 and pilot period, all forces

| Year ending March 2019 | Year ending March 2019 | Pilot period | Pilot period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | |

| White | 2,852 | 27% | 6,624 | 41% |

| Black (or Black British) | 4,870 | 47% | 6,590 | 40% |

| Asian (or Asian British) | 1,832 | 18% | 1,926 | 12% |

| Chinese and Other | 216 | 2% | 646 | 4% |

| Mixed | 644 | 6% | 522 | 3% |

| Total (known ethnicity) | 10,414 | 100% | 16,308 | 100% |

| Not stated | 3,001 | 22% | 956 | 6% |

Source: Table 11 and Police powers and procedures (2020) statistical bulletin.

An arrest or other outcome (those listed in section 3.5) was given to 12% of those searched from a Mixed ethnic group, to 9% of those from both a Black ethnic group and those from an Asian ethnic group, to 8% of White individuals, and to 7% of individuals from a Chinese and Other ethnic group. While data on outcomes other than arrest were not collected specifically for s60 searches in previous years, Table 3.6 shows how the arrest rate for each ethnic group compares with the year ending March 2019. Across all ethnic groups, the arrest rate was lower in the pilot period than in the year ending March 2019. The arrest rate was highest amongst the ‘Mixed’ ethnic group for both years, at 7.1% in the year ending March 2019 and 5.2% in the pilot period.

Table 3.6: Arrests following a search under s60, by ethnic group, year ending March 2019 and pilot period

| Year ending March 2019 | Year ending March 2019 | Pilot period | Pilot period | Pilot period | Pilot period | Pilot period | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number resulting in arrest | Arrest rate | Number resulting in arrest | Arrest rate | Number of other CJS outcomes | Other CJS outcome rate | Combined arrest and other CJS outcome rate | ||

| White | 147 | 5.1% | 243 | 3.7% | 280 | 4.2% | 7.9% | |

| Black (or Black British) | 273 | 5.6% | 287 | 4.4% | 330 | 5.0% | 9.4% | |

| Asian (or Asian British) | 67 | 3.7% | 70 | 3.6% | 107 | 5.5% | 9.2% | |

| Chinese and Other | 14 | 6.5% | 21 | 3.3% | 22 | 3.4% | 6.7% | |

| Mixed | 46 | 7.1% | 27 | 5.2% | 34 | 6.5% | 11.7% | |

| Not stated | 89 | 3.0% | 28 | 2.9% | 22 | 2.3% | 5.2% | |

| Total | 636 | 4.7% | 676 | 3.9% | 795 | 4.6% | 8.5% |

Source: Table 11 and Police powers and procedures (2020) statistical bulletin.

Note:

- CJS = Criminal justice system.

4. Authorisations: rank, duration and extensions

This chapter covers data on 3 of the relaxations on section 60 (s60) stop and search:

-

the lowering of the level of initial s60 authorisations from chief officer down to an officer of or above the rank of an inspector

-

the maximum length of initial authorisations extending from 15 to 24 hours

-

lowering the authorisation level needed to impose an extension from chief officer to superintendent and increasing the time of an extension from 39 hours to 48 hours

It was not feasible to collect data on the change in degree of certainty from a belief that serious violence ‘will’ occur to ‘may’ occur.

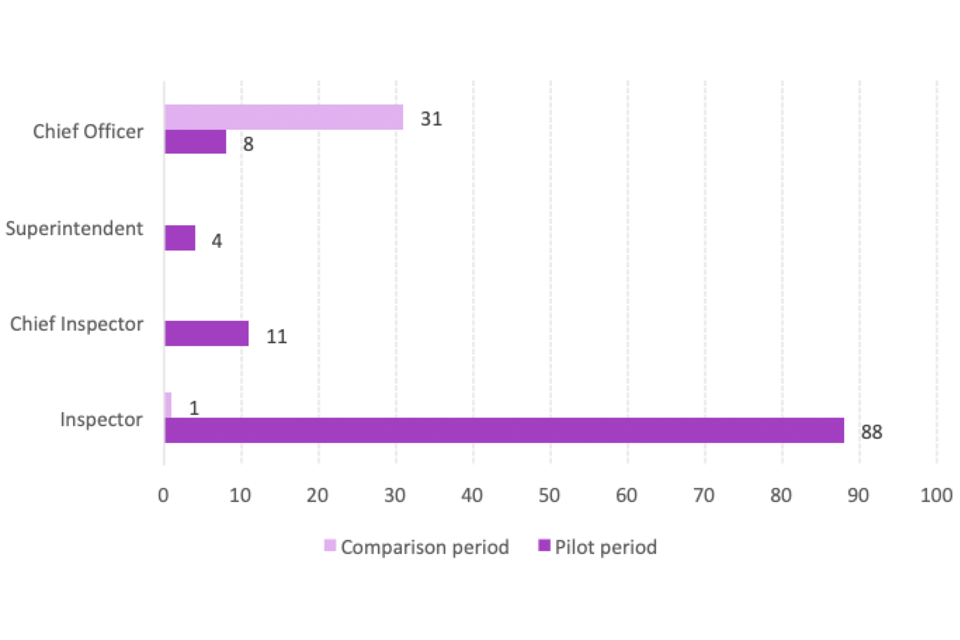

4.1 Authorising officer rank

Nationally, almost all police forces that used s60s responded to the April rank relaxation by moving to lower ranks authorising s60s in most cases (Figure 4.1). The rank of the authorising officer was known for the vast majority (99%) of the authorisations in the pilot period[footnote 19]; 85% were initially authorised by an inspector, and just 5% were authorised by a chief officer, the majority of the latter being in the West Midlands. Eight forces continued to have one or more s60 authorised by a chief officer during the pilot period. However, the overall trend was a switch away from chief officer-led authorisations in the pilot period.

Figure 4.1: Authorisations, by rank of initial authorising officer, pilot period

A pie chart showing the rank of the authorising officer. 85% of all s60s were authorised by an inspector.

Source: Table 5.

Notes:

- For the ‘original’ forces the pilot period is 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020. For the remaining ‘later’ forces the pilot period is 12 August 2019 to 31 March 2020. N = 795.

- Excludes 10 authorisations where the authorising officer was not stated.

For 6 forces[footnote 20] more data were collected to allow a comparison with the previous year. Three of these forces joined the pilot in April 2019, and so data across 2 full years are compared. For the 3 forces that joined the pilot later (August 2019), data for the equivalent 8 months[footnote 21] are compared.

Figure 4.2 confirms the general shift in these 6 forces from chief officer to inspector-led authorisations. Whilst the majority were authorised below the rank of chief officer, the forces that joined the pilot in August 2019 had a higher proportion of chief inspector to chief superintendent-led authorisations compared to the ‘original’ forces (13% compared with 6%). The West Midlands accounted for the majority of chief officer authorisations during the pilot period.

Figure 4.2: Authorisations, by rank of initial authorising officer in the 6 forces

Two pie charts comparing the authorisations by rank for the comparison period and the pilot period. In the comparison period, 98% of all authorisations were undertaken by a chief officer. In the pilot period, this fell to 4%.

Notes:

- For the ‘original’ forces (Merseyside, the MPS, West Midlands) the pilot period is 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020 and the comparison period is 1 April 2018 to 31 March 2019.

- For the ‘later’ forces (BTP, Cheshire, Kent) the pilot period is 12 August 2019 to 31 March 2020 and the comparison period is 12 August 2018 to 31 March 2019.

- Pilot period n = 709.

- Comparison period n = 431.

- Excludes 3 authorisations where the authorising officer rank was not stated.

4.2 Duration of the initial authorisation

The ‘August’ relaxations increased the maximum length of initial duration of a s60 (not including extensions) from 15 to 24 hours. Overall, 83% of initial authorisations were for 15 hours or less in duration from August 2019 to March 2020. However, the pattern varied markedly between the ‘original’ and ‘later’ forces (see Figure 4.3). Whilst only 3% of the ‘original’ forces’ authorisations were between 16 and 24 hours in length, more than half (52%) of the ‘later’ forces’ authorisations were this long. The qualitative analysis (Smith et al., 2023) found that officers in the 7 ‘original’ pilot forces – the biggest users of s60s – were less aware of the ‘August’ relaxations, on duration and communications, than the original ‘April’ changes. By contrast, the forces that joined the pilot in August 2019 received all 5 relaxations as a single package, and awareness of all the relaxations appeared to be higher amongst these interviewees.

Figure 4.3: Total length of authorisation, pilot period

A bar chart comparing the length of authorisations for the original pilot forces and other forces. Most authorisations by the pilot forces were up to 15 hours long.

Source: Table 4b.

Notes:

- 12 August 2019 to 31 March 2020 only.

- Original 7 pilot forces (n = 384) – Greater Manchester, Merseyside, the Metropolitan Police Service, South Wales, South Yorkshire, West Midlands and West Yorkshire.

- Remaining forces and BTP (n = 122).

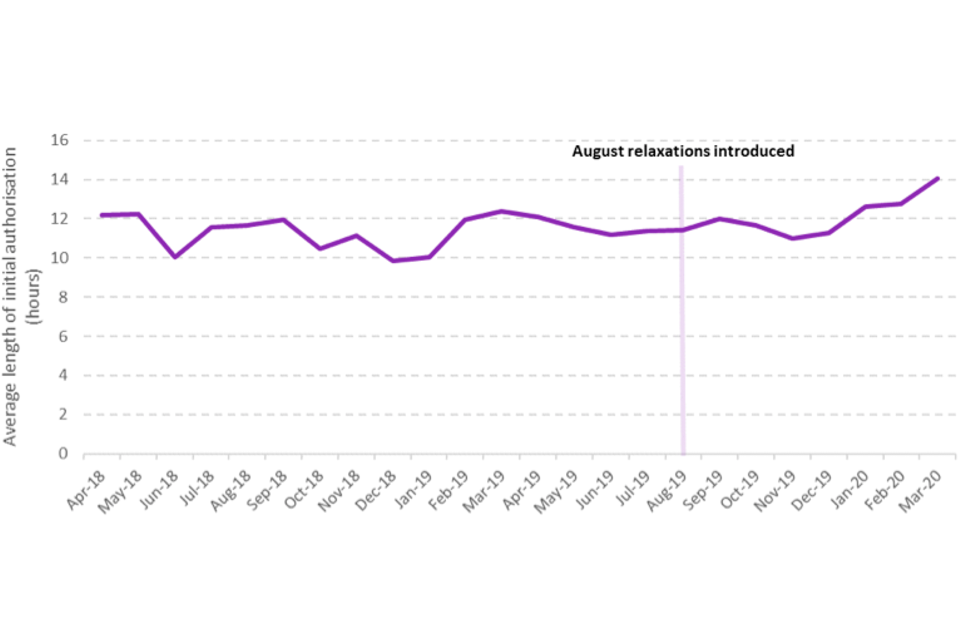

The 6-force data allow an analysis of the durations during the comparison period and the pilot period (the 43-force data only cover the pilot period).[footnote 22] Figure 4.4 shows average initial authorisation durations per month before and after the August relaxations were introduced. The average monthly duration is relatively stable between 10 and 12 hours. The impact of the longer durations for the ‘later’ forces is masked due to their lower volumes.

The mean average length of initial authorisation duration was similar regardless of rank of authorising officer (12 hours for both inspectors and chief officers in the ‘original’ forces, and 16 hours for both ranks among the ‘later’ forces).

Figure 4.4: Average length of initial duration, by month, 6 forces

A line graph showing how the average duration for a s60 has changed between April 2018 and March 2020. It has been broadly stable for most of the period, fluctuating between 10 and 12 hours, but increased slightly in the months to March 2020 (up to 14 hours).

4.3 Extensions

In the 8 months post-relaxation from August 2019 to March 2020, 10 extensions were identified across the 6 forces, equivalent to 2% of their authorisations. The majority of these extensions were for 9 hours. In the comparison period only 3 extensions were given.

Thus, the use of extensions was rare, both before and after the relaxations were introduced. Generally, police forces seemed to prefer a series of new sequential authorisations rather than using an extension (see for instance Chapter 6).

5. Communication of s60s using Twitter

As part of the Best Use of Stop and Search Scheme (BUSSS), police forces were required to communicate with the public about section 60s (s60s). In August 2019, when the pilot was extended to all forces and the relaxations expanded, s60s no longer had to be communicated publicly in advance. It was not possible to collect comprehensive data on the extent to which individual authorisations were communicated. However, some insight into the publicising of s60 authorisations can be gleaned by analysing data on forces’ use of social media. Twitter was chosen for this as based on discussions with forces it was felt to be one of the most commonly used forms of social media for sharing information on authorisations. Twitter also allows for accurate analysis of when the s60 was communicated as each tweet is time stamped.[footnote 23] This section sets out:

-

how often the 6 forces communicated s60s using Twitter

-

what was communicated

-

when this occurs in relation to the authorisation

Data were gathered from relevant Twitter accounts for the 6 forces[footnote 24] (see Table 5.1 and Appendix A for further details). A large number of accounts were searched in this process (650) using appropriate key words. The volume and diversity of police Twitter accounts is considerable and poorly mapped so some accounts might not have been identified. The majority of accounts identified as being relevant (78%) were at the neighbourhood and local level but these generated only 5% of all identified tweets. Most tweets were generated by London borough or district-level accounts (86%). It is possible that some instances of an authorisation being tweeted have not been located, principally because older tweets are at risk of being deleted.

Table 5.1: S60 tweets, by account, years ending March 2019 and March 2020

| Account type | Number of accounts | Number of tweets relating to s60s |

|---|---|---|

| Main police force accounts | 6 | 51 |

| Other central accounts1 | 22 | 4 |

| London borough and district accounts2 | 116 | 500 |

| Neighborhood and local accounts3 | 506 | 27 |

| Total | 650 | 582 |

Notes:

- Examples include the Metropolitan Police Service Taskforce and British Transport Police (BTP) Specials account.

- Includes BTP regional accounts.

- Includes local station accounts.

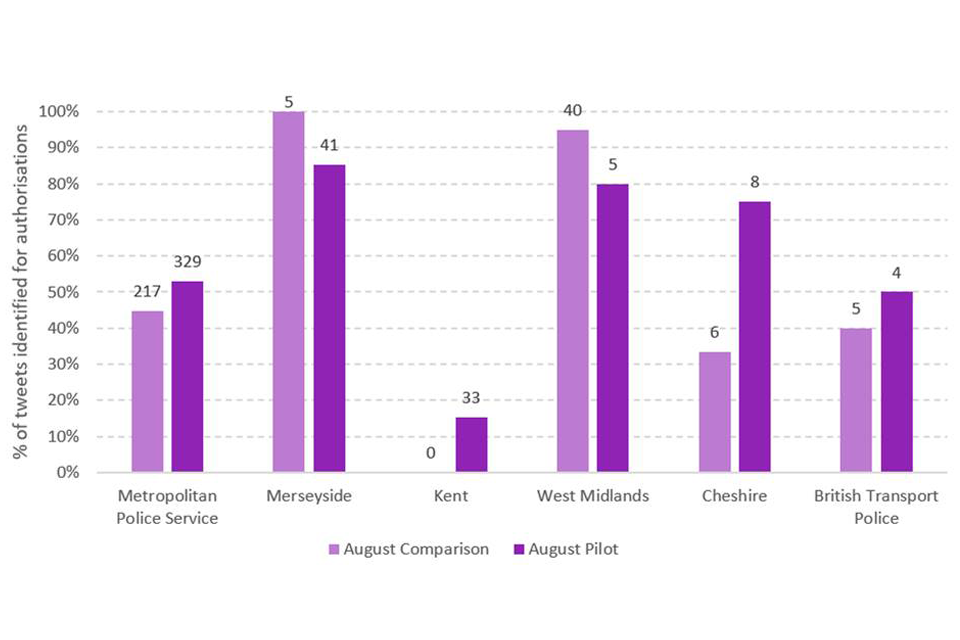

5.1 Proportion of authorisations tweeted

During the August pilot period[footnote 25], the proportion of authorisations with identified tweets ranged from 15% to 85% across the 6 police forces (see Figure 5.1). All but one force, and all the high-volume forces, tweeted details of at least half of their authorisations. The force that used Twitter the least for this purpose (Kent, 15%) indicated that they tended to use a more targeted communications strategy, for example, providing details via key community leaders. For all 6 forces combined, over half (54%) of the authorisations were tweeted in the August pilot period. The corresponding figure for the August comparison period was 53%. The pattern across individual forces varied.

It is hard to draw any clear inferences about the relationship between the relaxation on communications and the change in the proportion of authorisations tweeted. Patterns of use across forces were found to vary markedly. Moreover, the qualitative research (Smith et al., 2023) highlighted that awareness of the ‘August’ relaxations among the ‘original’ 7 police forces in the pilot, including on communication with the public, was low. This analysis also found that those forces which were aware of the change remained positive about the value of communicating authorisations. Finally, Twitter is just one of a number of channels that forces can use to communicate with the public, therefore this analysis will not have captured all communications of s60 authorisations.

Figure 5.1: Use of tweets, percentages of tweets identified for authorisations in the August pilot period, by force

A bar chart showing the use of twitter for communicating s60 authorisations in the pilot and comparison periods. Merseyside and West Midlands tweeted the highest proportion of their authorisations.

Note:

- The figures displayed above the bars represent the total number of authorisations in that police force for each period.

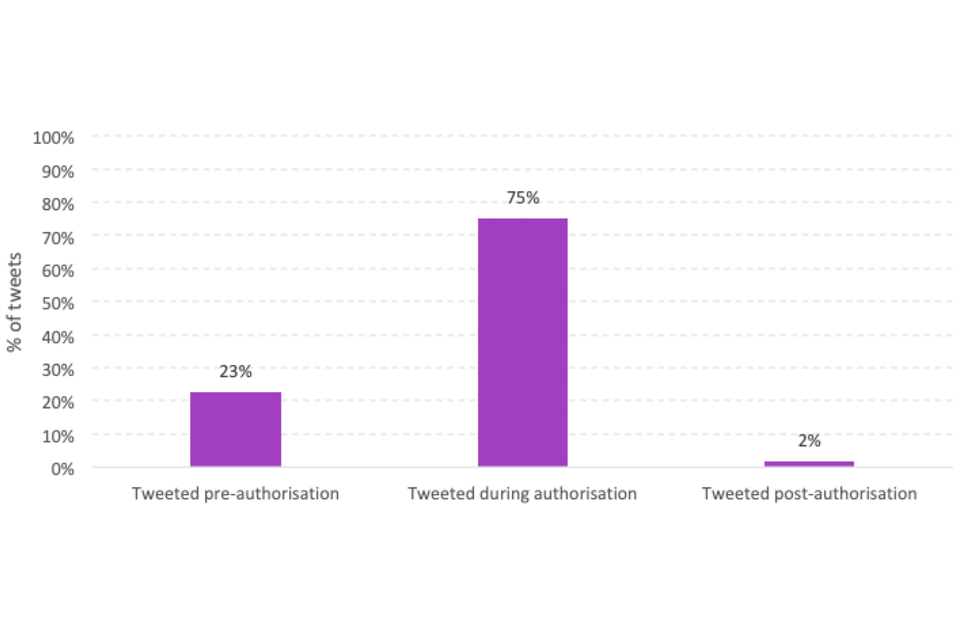

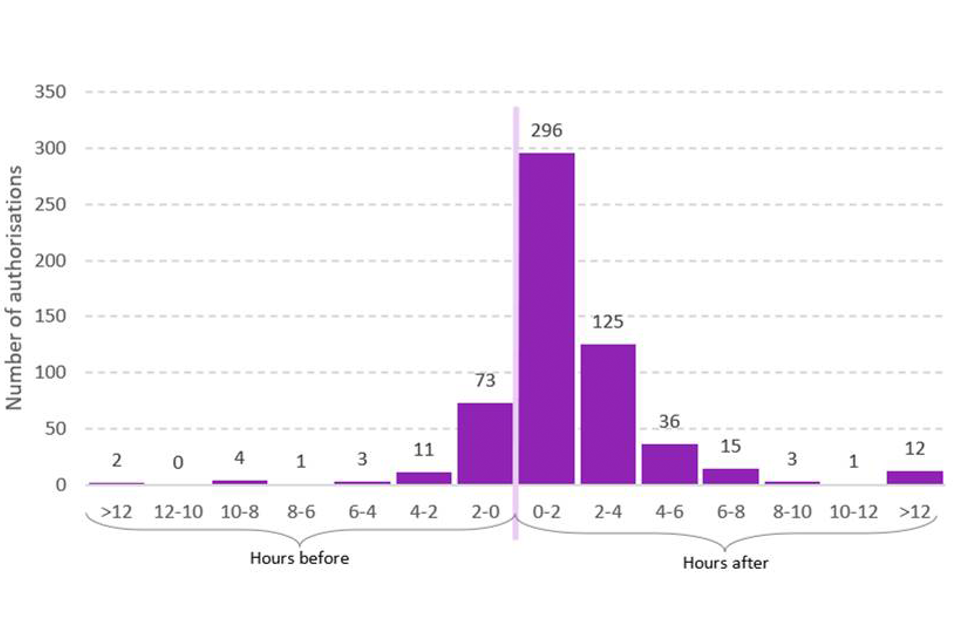

Because all tweets include a time stamp it is possible to analyse when details of authorisations were tweeted. Forces tended to tweet about the s60 during the authorisation period (just over three-quarters). Pre-authorisation tweets were less frequent (almost one in four) while post-authorisation tweets were rare (see Figure 5.2). Where there were tweets after the authorisation period had ended, these sometimes included information on the outcome of searches.

Figure 5.2: Time profile of tweets, years ending March 2019 and March 2020 combined, 6 forces

A bar chart comparing the time an authorisation is tweeted in relation to when it is authorised. Three-quarters of tweets are shared during the period covered by the authorisation, while just less than a quarter are shared before the authorisation.

Figure 5.3 gives a more detailed picture of the timing of the tweets and shows that, within the authorisation period, they were most commonly tweeted within the first 2 hours.

Figure 5.3: Distribution of tweet timings years ending March 2019 and March 2020 combined, 6 forces

A bar chart showing a detailed breakdown of the distribution of tweet timings. Most of the tweets are concentrated in the 2 hours after an authorisation begins.

Note:

- ‘After’ may include some tweets that took place after the authorisation had concluded.

Limited analysis was undertaken on the content of the tweets. Other research in the policing field (Nikolovska et al., 2020) has shown that tweeting images was positively associated with whether a tweet was retweeted and the number of times it was retweeted, which provides an indication of the extent to which people engage with messages. During the pilot period, across the 6 police forces the proportion of tweeted authorisations that included maps ranged from 0% to 85% with Merseyside having the highest number of tweets that contained maps.

6. Authorisations and searches

This chapter considers the relationship between authorisations, section 60 (s60) stop and search volumes, and outcomes. Although this was not directly covered by the relaxations, it is nonetheless an important dimension of how s60s are undertaken. Officers interviewed in the qualitative research suggested a number of ways in which s60s might help to disrupt serious violent crime. Not all of these depended on the execution of searches – some suggested that it was the s60 authorisation itself that operated as a deterrent, sometimes in conjunction with increased police visibility.

This chapter explores in more detail the year ending March 2020 national data on authorisations and searches. It then goes on to examine the 6-force data to explore change over time and the timing of individual authorisations.

6.1 Authorisations by number of searches: national data

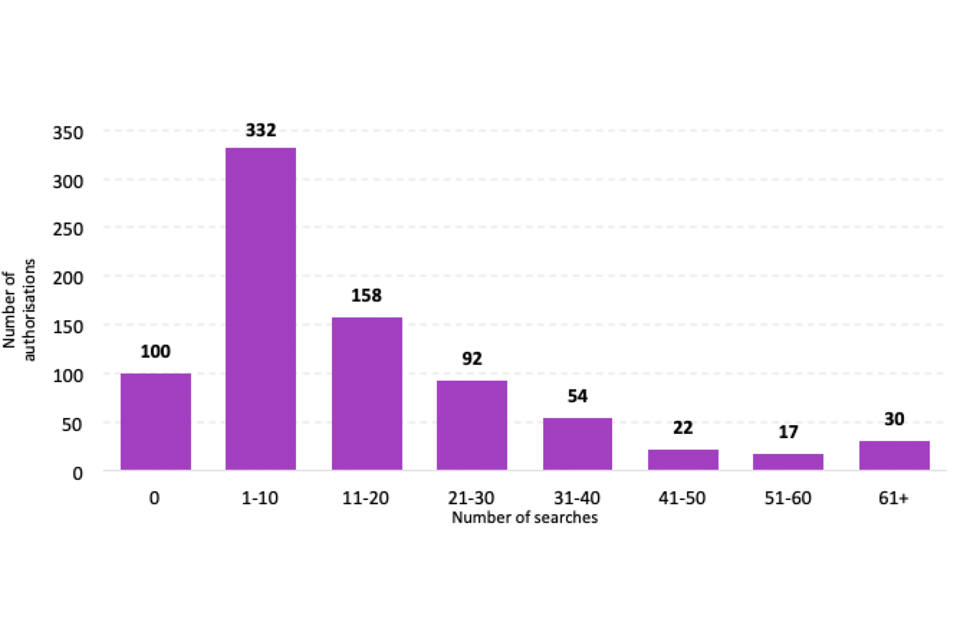

The 805 authorisations in the pilot period[footnote 26] resulted in 17,070 searches (excluding Lancashire[footnote 27]), with a mean of 21 searches per authorisation. Around one in ten authorisations during the pilot period involved no stop and searches, while a further 61% involved 20 searches or less (Figure 6.1). A small proportion of authorisations (4%) involved in excess of 60 searches.

Figure 6.1: Number of searches per authorisation, pilot period

A bar chart showing the number of searches done per authorisation. Most authorisations have 1 to 10 searches, few have more than 60.

Notes:

- Based on all forces.

- For all searches that could be linked to an authorisation.

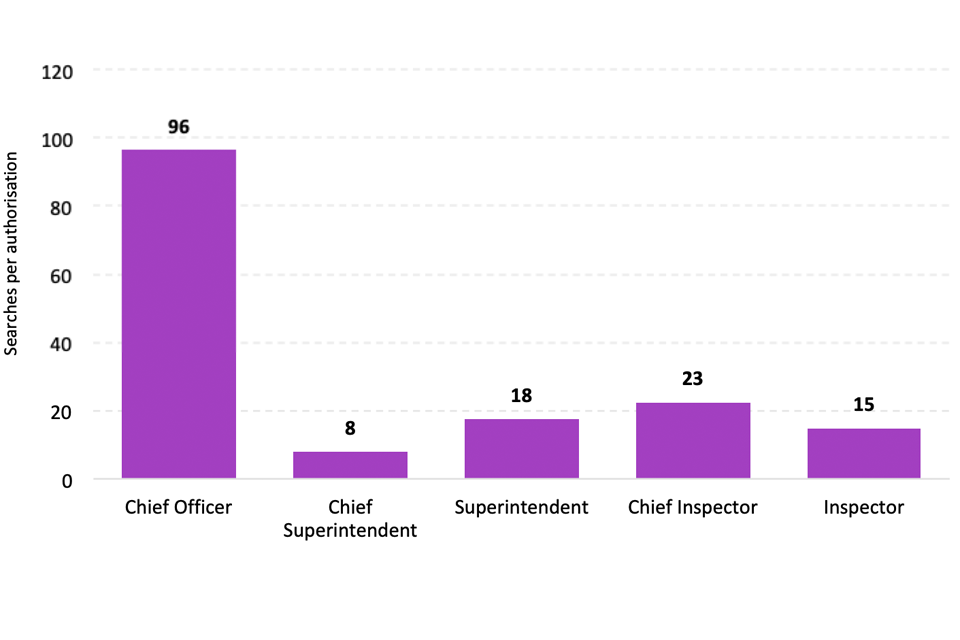

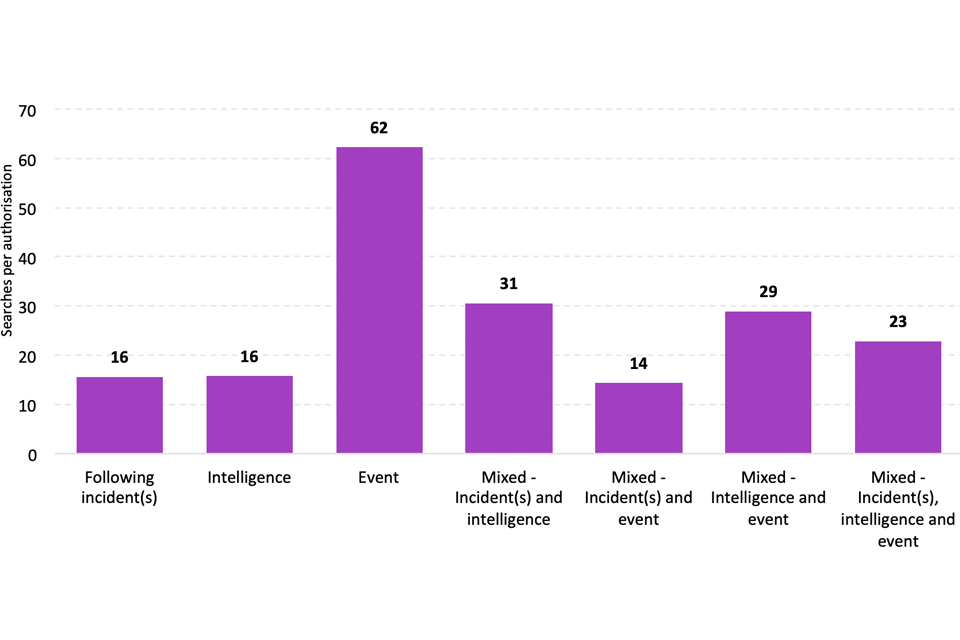

S60s authorised by chief officers had more searches per authorisation (96 searches) than those authorised by all other ranks. Chief superintendents had the fewest searches per authorisation (8 searches) while inspectors, who were responsible for the majority of s60s, had 15 searches per authorisation on average (see Figure 6.2). The high figure for chief officers partly reflects the fact that chief officers often authorise event-based s60s, which typically involved a markedly higher number of searches per authorisation, 62 searches compared with the overall mean average of 21 searches (see Figure 6.3).

Figure 6.2: Average number of searches per authorisation, by authorising officer rank, pilot period

A bar chart showing the average number of searches per authorisation by rank of authorising officer. Chief officer - authorised s60s result in the most searches (an average of 96 per authorisation). The equivalent figure for inspector authorised s60s was 15.

Note:

- Excludes 1,436 searches that were not stated/not linked.

Figure 6.3: Number of searches per authorisation, by rationale, pilot period

A bar chart showing the average number of searches per authorisation by the rationale for the authorisation. S60s authorised for an event result in the most searches (an average of 62). S60s following incidents on average generated 15 searches.

Note:

- Excludes 1,764 searches that were other/not known/not linked.

It has been well-established that the majority of s60s do not result in a criminal justice system (CJS) outcome (Home Office 2020). When searches linked to an authorisation in the pilot were examined in relation to search outcomes, authorisations with fewer searches had a higher success rate in terms of the proportion of searches resulting in an arrest or CJS outcome, see Table 6.1. Authorisations with between 1 and 10 searches have a success rate of 13%, compared with 7% for authorisations between 51 and 60 searches.

Table 6.1 Searches per authorisation, by outcome

| Number of searches within authorisation | % No further action | % Arrest | % Other CJS outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 to 10 | 87% | 7% | 6% |

| 11 to 20 | 91% | 4% | 5% |

| 21 to 30 | 92% | 4% | 4% |

| 31 to 40 | 91% | 4% | 5% |

| 41 to 50 | 94% | 2% | 4% |

| 51 to 60 | 93% | 3% | 4% |

| over 60 | 92% | 3% | 5% |

| Total | 91% | 4% | 5% |

Notes:

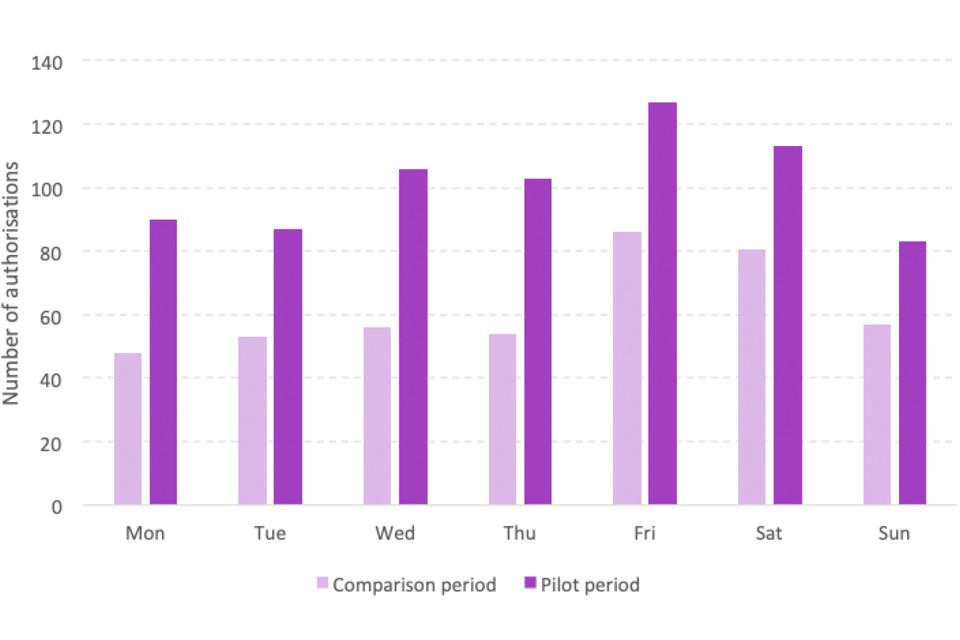

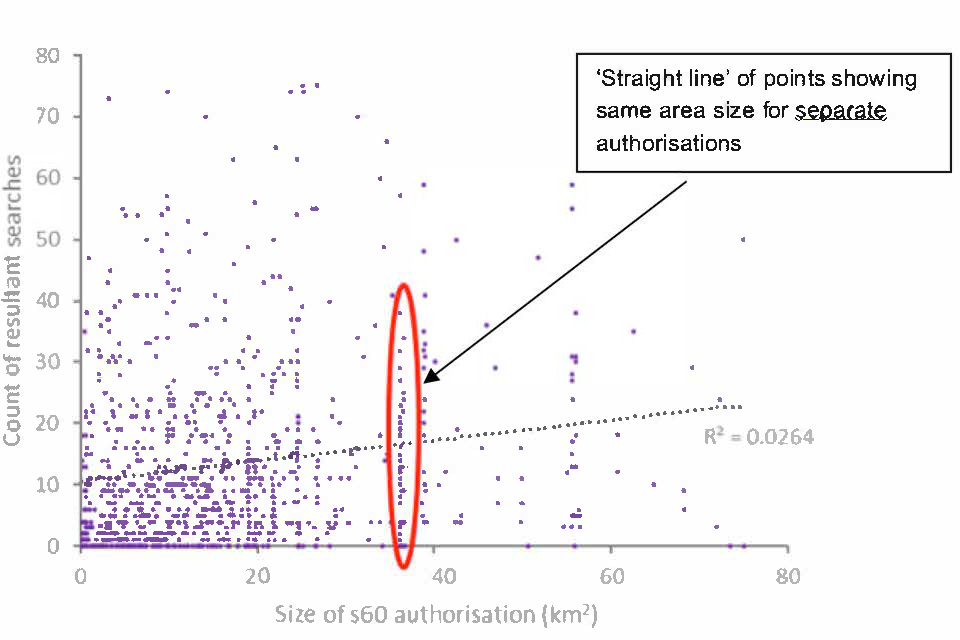

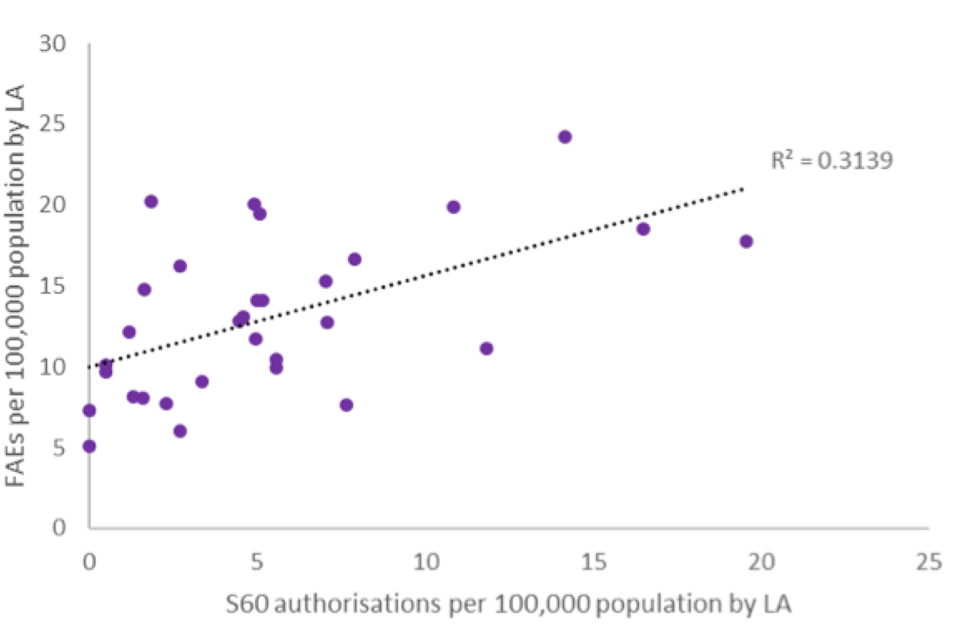

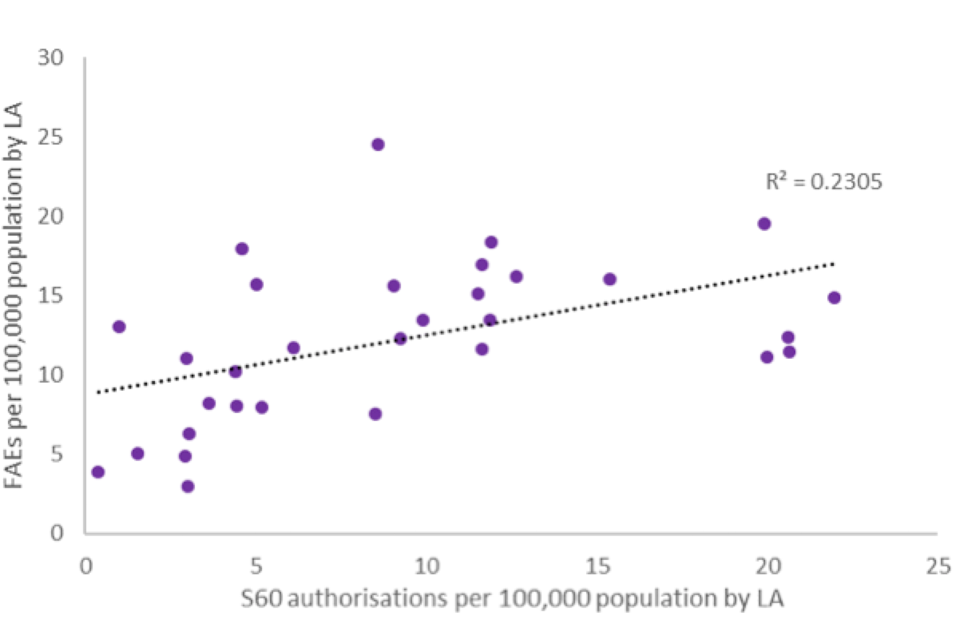

- Based on all pilot forces.