The section 60 stop and search pilot: interviews with police officers and community scrutiny leads

Published 19 June 2023

Authors: Victoria Smith, Laura Dewar, Daniel Farrugia, Michelle Diver and Andy Feist

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to a number of colleagues for their support in interviewing, reviewing, quality assuring, and drafting this report. Particular thanks go to Victoria Richardson, Abigail Cameron, Pamela Hanway, Scarlett Furlong, Ruby Forshaw and Katerina Stathoulopoulou. We would like to thank our participants for giving up their valuable time to be interviewed. We would like to thank Professor Karen O’Reilly and Professor Stuart Lister who independently peer reviewed the report, and members of the Steering Group for their help and advice during the course of the work.

Executive summary

Background

Section 60 (s60) stop and search powers give the police the power to stop and search persons and/or vehicles without reasonable suspicion when violence is anticipated. To enable the police to respond more effectively to serious violence, in March 2019 it was announced that 2 amendments to the Best Use of Stop and Search Scheme (BUSSS) would be piloted in 7 forces in England and Wales.[footnote 1] These forces are referred to as the ‘original’ forces. The amendments reduced:

-

the level of authorisation needed to impose a s60 stop and search, from chief officer to inspector level or above

-

the degree of certainty needed for an authorising officer to impose a s60, from believing an incident involving serious violence ‘will’ occur, to ‘may occur

In August 2019 this pilot was extended to all 43 police forces and the British Transport Police. The remaining forces that joined in August 2019 are referred to as the ‘later’ forces. All conditions placed by BUSSS on stop and search powers were relaxed, meaning that, in addition to the 2 existing amendments:

-

inspector authorisations could now last a full 24 hours (as opposed to 15 hours)

-

superintendents could now extend an authorisation beyond 24 hours to 48 hours (BUSSS required this to be done at chief officer level, and limited extensions to a total of 39 hours)

-

s60s do not need to be communicated publicly in advance

For all of these amendments it remained an operational decision for each police force as to how they were implemented.

Aims

The aims of this qualitative research study were:

-

to gather views from a range of police officers about their perceptions of the operational consequences of the April and August relaxations

-

identify perceived good practice in terms of the implementation of the relaxations

-

identify any unintended consequences for the police or the public due to relaxing the conditions

Views were also sought from those involved in the scrutiny of stop and search on the relaxations, s60s more generally and the community’s view of stop and search.

Undertaking a qualitative study has allowed the collection of insights from participants about their perceptions of the pilot, gathering detailed views from a range of officers involved at different stages of the s60 stop and search process. Those involved in the scrutiny of stop and search were also interviewed and 4 of their scrutiny meetings were observed. A total of 62 interviews were undertaken as part of the study. The study complements a sister report which includes quantitative analysis of the s60 pilot (Diver et al., 2023).

Key findings

Under the umbrella of s60 authorisations, the main distinction identified was between those s60s that were planned around major public events, and those that were reactive, either on the back of intelligence about local tensions, or in response to individual or multiple serious crimes. Planned s60s could be further split between those that were for regular, often annual, events – such as the Notting Hill Carnival – and those that were for occasional events (for example, a charity football match). Reactive s60s were the most common.

Decision making around s60 can arguably be divided into 2 elements:

-

an initial decision on the case for using a s60

-

whether it is considered the most appropriate approach to an issue, taking into account alternatives

Once this decision is made, a set of secondary decisions around its operational parameters on timing, geography, focus and access to resources follow. Making effective decisions around an authorisation also require assessing, and sometimes consulting on, the potential impact of using the power on the local community in the area covered.

Resource availability – the number of police officers available to run a s60 – was also identified as a key factor when deciding whether to authorise a s60. Some officers argued that securing additional ‘visible police’ resources was pivotal to deliver an effective s60 authorisation. Others took a more flexible and pragmatic view and felt that success was not necessarily dependent on securing additional officers.

There was no consensus on the mechanism by which the use of s60 might impact on serious crime. A minority of interviewees were doubtful around the evidence of any link. Interviewee views on the likely relationship between s60 authorisations and crime can be broadly grouped under 4 headings:

- by detecting individuals carrying weapons through the process of executing stops and searches

- by the s60 authorisation leading to increased police visibility and therefore increasing the perceived risk that would-be offenders have of being searched

- by using proactive public communication of the s60 to increase the perceived risk that would-be offenders have of being searched

- by reducing a specific threat of violence that the s60 was put in place to respond to

Most interviewees believed that any impact of a s60 on crime would be short term.

April relaxations

Awareness of the initial relaxations made to s60 in April 2019 was high amongst officers who took part in the research.

Reducing the level of initial authorisation needed to impose a s60 stop and search power from chief officer level down to inspector level or above.

Most police forces opted to move to inspector-level authorisations. In only one force was it mandated as policy to maintain the ‘chief officer’ requirement for authorisations. Two forces lowered the authorisation level to superintendent and one of these lowered it to inspector level following the August relaxations. The relaxation in rank of authorising officer was widely felt to have been beneficial to the speed of decision making, and improving the use of, and access to, the local area knowledge held by inspectors. Although some interviewees viewed this to be a positive change, as it promoted speed and flexibility, others raised concerns around this relaxation, notably the community scrutiny leads.

Several concerns were expressed about relaxing the authorisation rank. Increasing the pool of decision makers could mean that the use of s60 was less consistent within forces. It was felt that this could weaken perceptions of police legitimacy as a larger pool of decision makers might increase the risk of applying standards and thresholds inconsistently. It was also acknowledged that there was a more diverse range of professional knowledge and experience at inspector level, compared with more senior ranks, which could also lead to inconsistencies. A final potential concern was that the more intimate knowledge of their local areas that inspectors brought might limit their objectivity when considering an authorisation request. Although these potential concerns were raised by interviewees – and indeed one force decided not to adopt this relaxation for these reasons – little evidence was offered by interviewees about these concerns manifesting themselves in practice.

Interviewees in most forces noted that processes had been introduced to mitigate risks around the lowering of the authorising rank. Most forces covered in the study had introduced systems by which more senior or specifically trained officers had routine oversight of s60 decisions prior to the authorisation being agreed, and/or were involved in evaluating authorisations after the event.

Reducing the degree of certainty needed for an authorising officer to impose a s60 from believing an incident involving serious violence ‘will’ occur, to ‘may’ occur.

This relaxation was also widely viewed by officers to be a positive change. Officers felt that achieving the high degree of predictive certainty that violence ‘will’ occur was impractical and invariably difficult to evidence. ‘May’ was felt to better reflect the realities and uncertainties around predicting future serious violence. This change was felt to allow forces to be more reactive and speed up the authorisation process for dealing with spontaneous incidents, and generally raised little concern. Community scrutiny leads were also generally less concerned about this relaxation, although a minority raised issues about the potential ‘lowering of the bar’. But most scrutiny leads felt unable to comment on how the distinction might play out in operational terms.

August relaxations

Amongst the ‘original’ 7 pilot forces, officers were found to be generally unaware of the relaxations on communicating s60s with the public, initial durations and extensions. Awareness of these relaxations was higher amongst the ‘later’ forces where authorising officers (AOs) and stop and search leads (SSLs) in particular were well informed. However, several ‘later’ forces explicitly opted not to adopt the communications relaxation.

S60s do not need to be communicated publicly in advance.

Interviews with SSLs and AOs suggest that most police forces have continued to publicise s60s during the pilot despite the removal of the requirement to publicly communicate them in advance. Communicating with the public about s60s – especially in advance – was widely felt to bring a range of benefits in terms of legitimacy and public transparency. Also, for some officers, public communication of the authorisation was a key operational goal of how a s60 worked to prevent crime, by elevating the perceived risk of apprehending would-be offenders.

Although there were perceived benefits to communicating authorisations to the public in advance – usually via social media – there were certain situations, and some operational objectives, where it was argued that not communicating in advance was desirable. For instance, if the main operational goal was to detect and apprehend potential weapon carriers. Other circumstances that might lead to a s60 not being publicised in advance included very urgent responses to live incidents.

Inspector authorisations could now last a full 24 hours (as opposed to 15 hours).

This relaxation was predominantly viewed positively, and the additional flexibility that this gave to police officers was broadly welcomed. However, it was not deemed a substantial operational enhancement and many interviewees from the ‘original’ forces were not aware that these relaxations had been introduced. Some viewed the previous 15-hour duration to be adequate and shorter s60s would be put in place if appropriate.

Superintendents could now extend an authorisation beyond 24 hours to 48 hours (BUSSS required this to be done at chief officer level, and limited extensions to a total of 39 hours).

Extensions to s60s were felt to be used infrequently and the relaxation was not generally felt to have had a marked impact on the desire or need for them. So this relaxation was not believed to have had any major operational impact. However, a minority of interviewees felt that the change to superintendent had made the process quicker and easier, should it be required.

Introducing a new authorisation was sometimes preferred over the use of extensions, given the likely change in the intelligence picture.

Scrutiny arrangements and community relations

The research considered how external scrutiny functions operated across the different police force areas, and particularly how well community scrutiny leads felt that they were able to scrutinise s60s in the context of the pilot. Community scrutiny leads’ views were mixed. Some felt that there had been greater scrutiny and transparency since the pilot, but others felt that there had been no change or even a reduction. There were examples of positive working relationships between the police and scrutiny leads and a sense that they felt able to effectively share their views about police performance. However, there were more mixed views on the impact that they had on force policy and practice, and some felt that there was scope for increasing scrutiny lead involvement here.

S60s was only one area of many that the scrutiny groups covered. Coverage of s60 issues could be quite minimal, especially in forces that used s60s less frequently. But there were some frustrations over aspects of engagement with police forces, and there was a strong appetite for scrutiny groups to be more involved across the s60 process.

Some leads felt that they did not have sufficiently comprehensive or up-to-date data to scrutinise stop and search adequately, or that data were not of sufficient quality. A minority felt they had access to a wide range of information.

Community scrutiny leads also felt that there was further scope for scrutiny groups to influence and contribute to policy development in forces around stop and search. They felt they could, when time and access to intelligence allowed, contribute to informing decisions around individual authorisations. Finally, community scrutiny leads felt that there was value in retrospectively reviewing authorisation decisions.

There was widespread acknowledgement – across all interviewees – of the importance of community relations in informing the decision making, planning and execution of s60 authorisations. The extent to which individual AOs were able to articulate the issues from a community perspective, and responded accordingly, varied from officer to officer. A commonly held view was that, while desirable, seeking out community opinion could not always be undertaken as part of the s60 decision-making process, due to the speed needed to address issues in the wake of an incident.

Perceptions of s60 and how use has changed over time

Police officers’ views on s60 as a police power were broadly positive. Some felt that, overall, the relaxations had made use of the power less bureaucratic and more responsive to events.

Views from community scrutiny leads were more mixed. Whilst there was some consensus about the need for using s60 in specific circumstances, scrutiny leads were more uneasy about how a power to search without grounds was applied.

Some longer serving police interviewees described how wider messaging around the use of stop and search had influenced the use of s60 over time, leading to a steady fall in the years up the year ending March 2018. The reductions in use, allied to changes in public perceptions, were felt to have affected officer confidence in the use of stop and search. Conversely, greater use of s60 in recent years alongside the relaxations had, for some, brought with it a growth in confidence about the use of the power.

There was little agreement over the cocktail of factors that have driven recent increases in s60 authorisations and searches. Some officers pointed to the fact that the increase in s60s stemmed from recent increases in levels of serious violence and weapon carrying, and the emphasis – and additional resources – now given to tackling these offences. And while the relaxations themselves were infrequently cited as a factor increasing usage, the additional confidence that came with the change in messaging was given substantially more weight.

Concluding remarks

This study has sought to capture the views of police officers and community scrutiny leads (CSLs) on the section 60 (s60) relaxations and to some extent the wider use of s60 stop and search. It complements a more quantitative analysis of the s60 relaxations undertaken in parallel to this study (Diver et al., 2023).

Overall, this research shows that the way police officers viewed the use of s60 was diverse and more complex than was previously understood. It has shed a stronger light on the way that the police service is currently using s60 authorisations. This is important, not just in the context of understanding the police service’s view of the relaxations, but it also increases the understanding of the potential ‘theory of change’ around s60 authorisations and their possible impact on crime and disorder. Far from being a police tactic that was deployed uniformly, s60 authorisations were used in a variety of different ways, and with different operational goals in mind.

1. Introduction

On 31 March 2019 the Home Secretary announced that 2 relaxations to the Best Use of Stop and Search Scheme (BUSSS) would be piloted in 7 force areas: Greater Manchester Police (GMP), Merseyside, Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), South Wales, South Yorkshire, West Midlands, and West Yorkshire (Home Office, 2019a). The relaxations were announced to enable the police to respond more effectively to anticipated incidents of serious violence using section 60 (s60) stop and search and involved:

-

reducing the level of initial authorisation needed to impose a s60 stop and search power in a defined area from chief officer level down to an officer of or above the rank of an inspector (Table 1.1)

-

reducing the degree of certainty needed for an authorising officer to impose a s60 from believing an incident involving serious violence ‘will’ occur, to ‘may’ occur

Table 1.1: Officer rank structure

| UK forces | Metropolitan Police Service | City of London Police |

|---|---|---|

| Chief Constable | Commissioner | Commissioner |

| Chief Constable | Deputy Commissioner | Commissioner |

| Deputy Chief Constable | Assistant Commissioner | Assistant Commissioner |

| Deputy Chief Constable | Deputy Assistant Commissioner | Assistant Commissioner |

| Assistant Chief Constable | Commander | Commander |

| Chief Superintendent | Chief Superintendent | Chief Superintendent |

| Superintendent | Superintendent | Superintendent |

| Chief Inspector | Chief Inspector | Chief Inspector |

| Inspector | Inspector | Inspector |

| Sergeant | Sergeant | Sergeant |

| Constable | Constable | Constable |

Note: This rank table is only indicative of the hierarchy within each police force.

All other conditions remained as outlined in BUSSS. In this report these changes are referred to as the ‘April’ (2019) relaxations. Following this, in August 2019 the Home Secretary extended the pilot to all 43 police forces and the British Transport Police (Home Office, 2019b). The extended pilot relaxed all conditions placed by BUSSS on s60 stop and search powers. This meant that in addition to the 2 conditions relaxed above:

-

inspector authorisations could now last a full 24 hours (as opposed to 15 hours)

-

superintendents could now extend an authorisation beyond 24 hours to 48 hours (BUSSS required this to be done at chief officer level, and limited extensions to a total of 39 hours)

-

s60s do not need to be communicated publicly in advance

For the relaxations that came into force in April and August, it remained an operational decision for each police force as to how they were implemented, and which policies were put in place. Therefore, at police force level they could adapt any of the relaxations or continue with the conditions outlined in BUSSS. This report looks at how these changes to s60 were perceived by the police and the community within the 7 ‘original’ pilot forces and 3 of the ‘later’ forces. At the time of writing the pilot conditions are still active. Figure 1.1 sets out a timeline for the introduction of BUSSS and the relaxations.

Figure 1.1: Timeline of BUSSS, relaxations for s60, and surge funding

A timeline showing the changes made to section 60 guidance between April 2014 and August 2019. In April 2014, the Best Use of Stop and Search scheme (BUSSS) was introduced. In March 2019, 2 relaxations of the BUSSS conditions were piloted in 7 forces. In April 2019, the serious violence fund was introduced which allocated 65 million pounds to the 18 forces in the UK with the highest share of knife related injuries. The increase in spending helped drive more stop and search. In August 2019, the BUSSS was relaxed further, returning most conditions to the pre-2014 arrangements and extended to all forces.

1.1 Background

‘Stop and search’ typically refers to the statutory police powers to stop and physically search an individual. Most types of stop and search need to be justified by ‘reasonable suspicion’. This is usually based on intelligence or the belief that the search will uncover a specific illegal activity, or the possession of a prohibited or an illegal item. However, some legislation allows stop and searches without reasonable suspicion when terrorism, football-related disorder or other forms of violence is anticipated (McCandless et al., 2016). This report focuses on s60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994, which allows a stop and search within an authorised locality without reasonable suspicion when violence is anticipated.

Following a period of relatively high use of stop and search, a series of reports and reviews into stop and search were published. These raised questions about its effectiveness and use, such as the Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) (2013) report Stop and Search Powers. This contributed to a 99% drop in s60 use from around 150,000 in the year ending March 2009 to 1,061 in the year ending March 2015. In 2014 the Government committed to do more to improve stop and search and introduced new reforms to make stop and search fairer and more effective, including the introduction of BUSSS. BUSSS was introduced in 2014 to increase transparency, foster community involvement, improve outcomes and to capture the outcomes of searches in greater detail. The main changes to help to achieve these aims were as follows.

-

Increased data recording: recording a broader range of stop and search outcomes and the link between the object of the search and its outcome

-

Policies allowing lay observation of stop and search and a community complaints trigger – a local complaint policy requiring the police to ensure that the individuals who are stopped and searched are aware of where to complain. A threshold was also introduced, above which the police are compelled to explain their use of stop and search and that explanation will be given to local community scrutiny groups

-

Measures aimed at reducing s60 searches:

- raising the level of authorisation to chief officer[footnote 2]

- the authorising officer must reasonably believe that serious violence will take place rather than may take place

- limiting the duration of initial authorisations to no more than 15 hours (down from 24)

- ensuring that s60 stop and search is only used where it is deemed necessary

- communicating to local communities when a s60 authorisation is in place

Force participation was voluntary but BUSSS compliance was considered in a HMIC inspection in 2015 (HMIC, 2015). This inspection led to 13 forces that were deemed to be the least compliant being suspended from the BUSSS scheme and a further 19 being put on notice. By November 2016 the forces suspended were readmitted after further inspection, and most of the forces put on notice were found to be compliant.

Following the introduction of the BUSSS scheme, s60 stops fell further to only 617 in the year ending March 2017 (Home Office, 2017). At this time there were growing concerns around increases in serious violence, and with it, expectations that the police would take stronger action to tackle it, including the more widespread use of stop and search powers as a tool. S60 use increased in the year ending March 2018 to 2,501, but this was still at historic lows (Home Office, 2018). The police argued that the conditions as set out in BUSSS were too bureaucratic and needed to be relaxed for them to better tackle serious violence. The Government announced the initial pilot relaxations in March 2019, but further extended both coverage and the breadth of the relaxations in August 2019.

In the year ending March 2020, police in England and Wales carried out 18,081 stops and searches under s60 authorisations, an increase of 35% (4,666 searches) on the previous year. This is the third consecutive annual increase and follows a substantial increase between the years ending March 2018 and March 2019, when the use of s60 searches increased more than fivefold, from 2,502 to 13,415 searches. The increase in the latest year was driven by a handful of forces, notably, the MPS, which accounted for 39% of the increase, followed by Essex (which accounted for 18% of the increase), Merseyside Police (17%), and Thames Valley Police (16%). As in previous years, most s60 stops took place in London, with the MPS accounting for around two-third (63%) of all s60 stop and searches in England and Wales, followed by Merseyside (7%), and British Transport Police and Essex (both accounting for 5% of s60 searches) (Home Office, 2020). In spite of the most recent increases, s60 still only accounts for 3% all stop and searches. Stops under section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (s1) – which require reasonable grounds for suspicion – are far more common (558,973 in the year ending March 2020).

1.2 Aims

The aims of the research were as follows.

-

to establish how police officers perceived the operational consequences of relaxing each of the April s60 conditions

-

to identify perceived good practice examples of how to implement the s60 relaxations

-

to find out whether the pilot relaxations had any impact on the scrutiny of stop and search, or on community views of the police or stop and search

-

to identify any unintended consequences for the police or the public of relaxing the conditions

-

to identify how the relaxations made in August around extending authorisation periods and removing the need to communicate s60s publicly in advance were perceived

2. Methodology

The aim of this research was to gather insights from participants about their perceptions of the pilot. To do this, the research team developed a qualitative research methodology which sought to gather detailed views from a range of police officers involved at different stages of the section 60 (s60) stop and search process. This focused on their perceptions of the pilot and how individual forces responded to the changes. Those involved in the scrutiny of stop and search were also interviewed and the research team observed 4 of their scrutiny meetings. The team examined whether there were any changes in force practices in response to the pilot, how relaxing the conditions changed police operations, and community scrutiny leads’ perceptions of the power and the relaxations. A more detailed set of research questions can be found at Appendix A.

2.1 Fieldwork composition and coverage

Home Office researchers carried out 62 interviews with the following participant groups in 10 force areas as part of this study.

Community scrutiny leads (CSLs):

- 11 CSLs who were involved in the process of scrutinising stop and search

Police officers:

-

10 stop and search leads (SSLs) who had an overview of stop and search policy and practice within each force, including training and dissemination of guidance

-

20 authorising officers (AOs) who were generally most affected by the changes brought about by the pilot

-

16 searching officers (SOs) who had carried out s60 stop and searches on the ground

-

5 assistant chief constables (ACCs) who were authorising officers prior to the pilot

The research did not include the perspectives of those stopped and searched. This was due to the relaxations being largely focused on police processes, which would not be apparent to those being searched nor change the way in which s60 searches are carried out.

Fieldwork with those in the 7 ‘original’ pilot forces[footnote 3] took place from 11 October 2019 to 5 May 2020. From 11 May 2020 to 4 July 2020 fieldwork was also carried out with 3 forces that joined the pilot in August to explore whether those forces joining later had different views and experiences compared with the ‘original’ 7 forces. These were the British Transport Police, Cheshire, and Kent.

In the MPS, interviews were undertaken in Brent, Croydon, Haringey, Merton, Newham, and Westminster boroughs. These were selected using the MPS online data dashboard to identify some of the highest s60 using boroughs during the first 3 months of the pilot. The selection was structured to provide a good geographical spread across London. Although Kensington and Chelsea is the borough with the highest number s60 searches, it was not selected as most s60 searches can be attributed to authorisations put in place for the Notting Hill Carnival. Notting Hill could be viewed as atypical since it is planned far in advance and only reflects a very specific type of s60 authorisation. A more detailed breakdown of the numbers of participants interviewed in each pilot location can be found in Table 2.1 below.

Table 2.1: Breakdown of the number of interviewees, by participant group and police force area

| Police force | Community scrutiny lead | Stop & search lead | Authorising officer | Searching officer | Follow-up interviews with assistant chief constables | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘Original’ 7 police forces in the pilot | ‘Original’ 7 police forces in the pilot | ‘Original’ 7 police forces in the pilot | ‘Original’ 7 police forces in the pilot | ‘Original’ 7 police forces in the pilot | ‘Original’ 7 police forces in the pilot | ‘Original’ 7 police forces in the pilot | ‘Original’ 7 police forces in the pilot | |||||||

| Metropolitan Police Service | 2 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 16 | ||||||||

| West Midlands | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 | ||||||||

| Merseyside | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||

| Greater Manchester | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||

| West Yorkshire | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | ||||||||

| South Wales | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||||||||

| South Yorkshire | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||||||||

| Totals for ‘original’ 7 pilots | 9 | 7 | 14 | 13 | 5 | 48 | ||||||||

| 3 ‘later’ police forces that joined the pilot in August | 3 ‘later’ police forces that joined the pilot in August | 3 ‘later’ police forces that joined the pilot in August | 3 ‘later’ police forces that joined the pilot in August | 3 ‘later’ police forces that joined the pilot in August | 3 ‘later’ police forces that joined the pilot in August | 3 ‘later’ police forces that joined the pilot in August | 3 ‘later’ police forces that joined the pilot in August | |||||||

| Cheshire | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | ||||||||

| Kent | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 6 | ||||||||

| British Transport Police | 01 | 12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | ||||||||

| Totals for ‘later’ 3 forces | 2 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 14 | ||||||||

| Grand total of interviews in all 10 forces | Grand total of interviews in all 10 forces | Grand total of interviews in all 10 forces | Grand total of interviews in all 10 forces | Grand total of interviews in all 10 forces | Grand total of interviews in all 10 forces | Grand total of interviews in all 10 forces | Grand total of interviews in all 10 forces | |||||||

| Grand totals | 11 | 10 | 20 | 16 | 5 | 62 |

Notes:

- This individual was interviewed as a scrutiny lead for the MPS and is therefore included in the MPS count above to avoid double counting.

- Was a tactical advisor.

Participating interviewees were identified by SSLs who provided the contact details of individuals who were involved in authorising s60s or searching. Although the approach varied slightly by force, generally a list of police officers who had been involved in s60s was provided to the research team. From the list, the officers with the most s60 experience were selected for interview, although not all would necessarily have had experience of s60s before the pilot. The West Midlands chose not to reduce the authorisation level for a s60 to inspector. This meant that AOs interviewed in this force tended to be of a higher rank than in other pilot areas. Contact details for the scrutiny groups were also provided by forces although the approach in selecting participants varied slightly. Some forces had multiple scrutiny groups across different locations, so the focus was on those locations with higher use of s60 and/or groups with a stronger remit around reviewing s60s.

Four scrutiny meetings were observed in the MPS and West Midlands (2 in each location). These 2 forces were selected as they had the highest use of s60 in the year ending March 2019 and the groups had a clearer remit around reviewing s60s. At each of these scrutiny meetings there were 2 observers. An observation schedule was completed when attending the scrutiny meetings to ensure that consistent features, such as the structure, remit and content of the session were recorded. The observation schedule can be found at Appendix B.

Interviews with those in the original 7 pilot forces typically lasted between 45 minutes and an hour and all were conducted face-to-face except for 2, which were conducted by telephone. At each interview there was one interviewer and one note-taker. All were audio-recorded and transcribed. Due to coronavirus (COVID-19) restrictions, the interviews with the 3 forces that joined the pilot in August were all carried out over the telephone with 1 interviewer and lasted around 55 minutes. Topic guides were developed for each participant group, covering the areas explored to address the research objectives and questions. An example can be found at Appendix C.

An additional 5 short telephone interviews, lasting around 30 minutes, were carried out with ACCs in August and September 2020 from forces where the relaxations had led to the authorisation being lowered from ‘chief officer’. This was to explore in more detail some of the areas that emerged from the original fieldwork. For police officers, rank and force type (‘Original’ or ‘Later’) are listed with each quote, along with the number assigned by the research team to that participant. For CSLs, force type and the participant number are provided.

The interview team felt that they were able to establish a good rapport with participants in both the face-to-face and telephone interviews. The flexibility of the semi-structured topic guides allowed the team to be responsive to participant’s views and meant they could tailor a line of questioning as their understanding of the participant’s perspective increased. This approach helped the team to establish trust with the participants and allowed them to be open and honest.

Data protection regulations were followed for data collection, management and storage of information.

2.2 Quality assurance and research governance

A thematic analysis of the notes and transcripts was undertaken to identify the main themes emerging from the interviews. To identify these, the research team individually reviewed the interview transcripts and met to discuss and agree the key themes emerging from each participant group. These themes were quality assured by 2 additional reviewers outside of the core research team to check for consistency in the areas highlighted and identify any gaps. To ensure all areas of concern and perceived good practice in response to the relaxations were identified, an additional reviewer analysed the detailed interview notes to confirm that these had all been highlighted.

To provide governance to the research, a Steering Group consisting of representatives from the College of Policing, Cabinet Office Race Disparity Unit and HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services was established. The group was asked to give views on the direction of the project, the research tools and methodology, and met at key stages during the research.

2.3 Research focus and limitations

This qualitative research looks at the perceived changes made as part of the pilot, which are relatively modest in their nature. It was agreed from the outset that it was not feasible to establish whether the pilot changes would, of themselves, have a causative impact on crime levels. The relatively modest nature of the relaxations, the scope for police forces to adopt or reject them, the way the pilot was rolled out and the relatively small number of s60s expected to be undertaken during the pilot, meant it was impractical to run an outcome-focused study. Previous UK-based research has not found evidence of a direct crime reduction effect from stop and search (McCandless et al., 2016; Tiratelli et al., 2018).[footnote 4] These studies have looked at relatively large geographies (borough level), and it is acknowledged that more local crime reduction effects may exist. One USA study (New York) has found small positive effects for ‘stop, question, frisk’ at very local levels – so-called ‘street corner’ segments – although there are marked differences in how those arrested through stop/searches are dealt with in the USA compared to the UK (Weisburd et al., 2016). Although this research does not, therefore, address crime reduction impacts, it does shed some light on how police officers perceive s60 works to tackle crime. These insights may help to guide the framing of future research around s60 effectiveness.

This research draws together the perceptions of police officers and CSLs. Given the nature of all qualitative research, the findings of this report outline in broad terms the views and perceptions of those selected for interview. The precise balance of views may not therefore be repeated if the exercise was repeated with a different group of individuals. The qualitative work has, however, been complemented by a parallel quantitative data collection exercise, outlined below.

This study captures a broad reflection of police officers’ views. Although the sampling of interviewees was focused on those with longer experience in the use of s60s, some interviewees still had no experience of s60 prior to the pilot so could not provide any comparative views around perceived changes in practice. Additionally, some police interviewees often could only offer a more localised assessment of force practice – not all could offer a force-wide picture of how the relaxations were being implemented and working in practice.

2.4 Quantitative data

The Home Office already collects annual data from all police forces on the use of s60. These include data on the number of searches, number of arrests, where the arrest is for weapons, and the ethnicity of the person searched.

A bespoke section 60 (s60) statistical data collection exercise was carried out with all 43 territorial police forces in England and Wales, and the British Transport Police (BTP). The period covered by these data was 1 April 2019 to 31 March 2020 for the ‘original’ 7 forces that joined the pilot on 1 April 2019. For the remaining ‘later’ forces that joined on 12 August the pilot period covers 12 August 2019 to 31 March 2020. For every s60 authorisation, forces were asked to submit data on:

-

the rank of the authorising officer

-

free text to explain the rationale and location of the authorisation

-

start date and length of the authorisation

-

the number of individual searches resulting from the authorisation

The free text for the rationale for the authorisation was then read and coded by analysts into one of 4 categories: ‘following an incident’, ‘event’, ‘intelligence’, ‘other/unknown’[footnote 5].

Forces were also asked to complete information on: the self-defined ethnicity of any person searched, the outcome of each search; and whether a knife or sharp instrument was found in the search.

Additional descriptive statistics on authorisations in the year ending March 2020 are included in the sister report on the pilot: ‘ The section 60 stop and search pilot: Statistical analysis and review of authorisations’ (Diver et al. 2023). This report also includes more detailed quantitative evidence from 6 forces: MPS, West Midlands, Merseyside, British Transport Police, Kent and Cheshire. Collection of these detailed data allowed the research team to look in more detail at the various components of authorisations in the years ending March 2019 and March 2020. These data also include details on the size of the geographical area covered by the authorisation and whether the authorisation was communicated on Twitter. Finally, information was retrieved and coded from a selection of 143 s60 authorisation forms from 5 of the forces across the 2 years.

2.5 Report structure

Chapter 3 and chapter 4 of this report look at the nature of the decision-making process and perceptions on s60 and the impact on crime. Chapter 5 and chapter 6 focus in detail on perceptions of the relaxations. Chapter 7 examines scrutiny processes and community relations while Chapter 8 looks broadly at interviewee perceptions of s60 stop and search as a whole and how these have changed over time. Finally, Chapter 9 covers awareness of the relaxations and the training and guidance provided and Chapter 10 provides concluding remarks.

3. Perceptions on the decision-making process behind s60 authorisations

To appreciate how participants perceived the relaxations and their operational impact, it is helpful to describe how they viewed different types of section 60 (s60) authorisations, and the decision making around the authorising process. This chapter looks at how police officers perceived the different applications of s60s and explores what participants felt were the critical decision points around sanctioning authorisations, and how decisions were made.

3.1 Classifying s60s

Interviews with authorising officers (AOs) highlighted the existence of a simple overarching framework for defining different types of s60. The main distinction identified was between those s60s that were planned around major public events, and those that were reactive, either on the back of intelligence about local tensions, or in response to individual or multiple serious crimes. However, planned s60s further split between those that were for regular, often annual, events – such as the Notting Hill Carnival and those that were for occasional events (for example, a charity football match).

Examples of ‘reactive’ s60s were most frequently described by interviewees. Although planned s60s were mentioned rarely, some do involve large numbers of searches (for example, authorisations put in place around the Notting Hill Carnival).

While planned and ‘reactive’ s60s were said to have the same rationale and decision-making process, planned s60s invariably allowed more time for preparation and obtaining additional resources. One view was that planned s60s needed more evidence to justify the reasons why serious violence is expected to occur. By contrast, ‘reactive’ s60s were felt to “sort of write your rationale for you” (AO10 – ‘original’ force).

3.2 The s60 decision-making process and consideration of alternatives

Interviewees were asked to describe the main elements around a decision to authorise a s60. These commonly focused on a number of key areas:

- the underpinning rationale for the s60

- the choice of the power over alternatives

-

the geographical area to be covered

- the length of time in place

- resource

- any issues around community focus

- communication with the local community

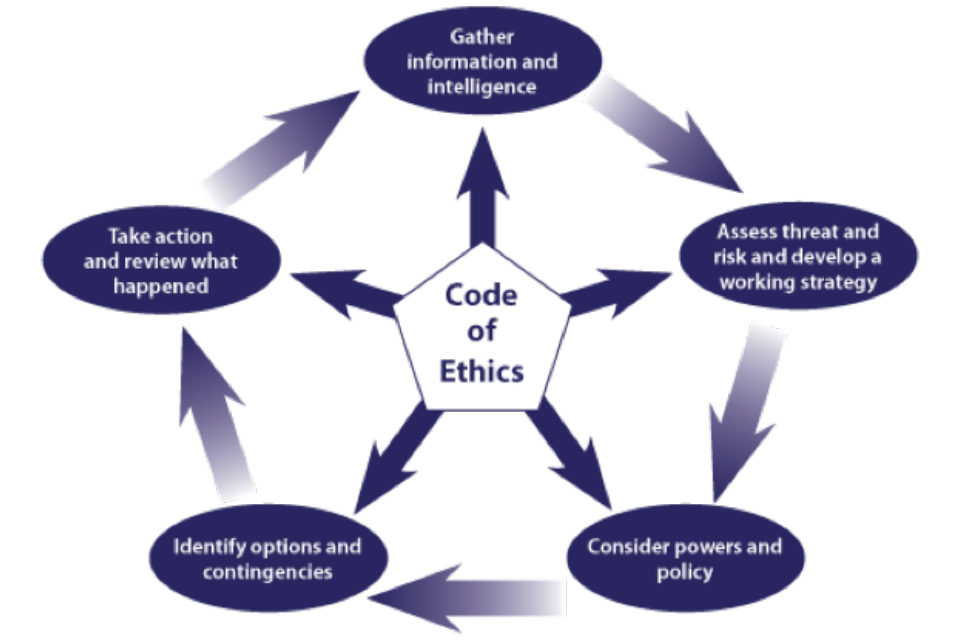

Details around the underpinning rationale will be covered in Chapter 5 and findings on s60 ‘triggers’ are detailed in the quantitative report (Diver et al., 2023). Several police interviewees specifically referenced their use of the National Decision Model (NDM) to guide the decision making around s60s. This generic model is recommended by the College of Policing as being suitable for use in all decision-making processes within policing. There are 6 key elements outlined in Figure 3.1 which are: the Code of Ethics, Information, Assessment, Powers and Policy, Options, and Action and Review (College of Policing, 2014).

Figure 3.1 The National Decision Model

National Decision Model, with the Code of Ethics at the centre. The other principles are arranged around the outside.

Source: College of Policing

“So we’ve got quite good public order and football planning and processes, so a lot of our cops are into the [NDM] style of decision making, and the inspectors and branch commanders , so they go through the process of assessing why we’d want a section 60, rather than just, like I said, just put a section 60 on because they can.” (Stop and Search Lead 7 – ‘original’ force)

Several officers gave full and thoughtful accounts of how they went through the decision-making process for authorising s60s, drawing on the framework provided by the NDM. The AO quoted below is one example.

“So with any sort of authority I like to know that I’ve utilised the power correctly and that if I’m putting my name to something that then it’s correct in my honest and best opinion, so I’ll use the [NDM], I’ll look at previous instances, I’ll look at the demographic of the ages or people involved and then the area as well, I’ll consider whether there is any other parts of legislation we can use as opposed to using a section 60. Is it a named offender and victim where we can then use other powers to go and arrest that person to reduce that threat of risk as opposed to doing a blanket power? And if those things aren’t suitable and I do think there’s that element in the community that are at risk, then I’ll consider how far and wide that power needs to be used. So by using the map system and making sure that the power is used in a controlled area around the correct demographic of age, description, ethnicity, anything else appropriate and how long that should be on as well, so the timeframe as well. Once I’ve come to that decision I’ll then decide to authorise it and then communicate that.” (Authorising Officer 9 – ‘original’ force)

The core decision to use s60, and consideration of alternatives

Generally, a review of a selection of authorisation forms indicated that the forms were completed by the AOs themselves, sometimes with support in terms of gathering intelligence and incident details from more junior officers. There was some evidence that before the pilot s60 applications were made by lower ranks where evidence was provided to AOs for them to consider. The way the NDM sets out the decision-making process did align with how some officers explicitly considered whether s60 was the most appropriate response to address a problem. So prior to getting into the detail around the precise operational parameters of an authorisation, the critical question was framed in terms of the case for using the power, as opposed to alternative powers or tactical approaches. Some AOs described going through a series of rhetorical questions about the appropriateness of s60. As one AO articulated: “Would putting uniform presence on the street be sufficient? Would an investigation enable people to be brought to justice, which would reduce that? Would […] putting warning notices out, would that make a difference? You know there are other tactics that you need to be looking at, and saying right, is this the least intrusive way of dealing with this?” (AO2 – ‘original’ force).

Where this process was most fully described it meant setting out the nature of the problem, the nature of the alternative approaches to deal with the problem, and the potential risks around considering a s60, if that was the preferred option. Several AOs provided examples where authorisation requests were rejected, for instance where the area could not be sufficiently well defined or where the circumstances related to only one individual, and where a section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (s1) search would be preferred.

“It’s fair to say that the PCs on the street, particularly for like the gang’s unit, have got a better knowledge of the suspects and the gang rivalries that go on. But as I say you could have one incident that’s in their view, it’s definitely gang-related, but for me just one single incident does not always warrant let’s create a section 60 because I think we’ll find ourselves back where we were way back then.” (Authorising Officer 14 – ‘original’ force)

One AO was also concerned that with the increased ‘normalisation’ of s60, some officers in the force expected s60s to be put in place and “used as a way of placating partners, concerned communities and partners quite quickly” (AO4 – ‘original’ force) when something happened.

“Section 60 is a good tool but it has an effect. Obviously it gets reported on local media, it puts potentially concerns out in the community and if it’s a more targeted approach where, as I mentioned earlier, it could be a suspect named that we think has got a weapon, etcetera. there are ways that we can deal with that and be more targeted as oppose to authorising the 60 for the searches. So it would have been that I didn’t think it met the criteria but if I have had to come to that decision I’ve always been supported in it, so it’s good to know. And from my understanding the inspector would ask for the rationale [for the] decision making and if it isn’t deemed appropriate use, then they would receive the feedback and guidance afterwards.” (Authorising Officer 9 – ‘original’ force)

Considering community impact in authorising s60s

Officers of all ranks acknowledged the sensitivities around the use of s60 and the impact it had on communities. These sensitivities placed an onus on making correct decisions over the use of s60. However, the extent to which individual AOs were able to articulate the issues from a community perspective, and responded accordingly, varied from officer to officer.

A commonly held view was that, while desirable, seeking out community opinion could not always be undertaken as part of the decision-making process, due to the speed needed to address issues in the wake of an incident. Other AOs stated that sometimes they didn’t always know who the relevant community contacts are in a particular area.

“I’m sort of shielded because we sort of work in silo so that feedback would come up through the sort of partnership neighbourhood side of policing and I’m on the operational frontline […] I should be hooked in with that feedback quite quickly but it wouldn’t come to me. I suppose if I proactively and specifically went out there and asked, I don’t necessarily know who the board councils are, who the stop and search leads are, and what they’re saying.” (Authorising Officer 4 – ‘original’ force)

However, AOs often sought to consider the potential impact that a s60 will have on the community and viewed this as a fundamental part of their decision-making process when considering authorisation. Overall, there was a delicate balance to be struck, between tackling crime, providing reassurance to residents that local problems were being dealt with, and minimising the risk of alienating members of the community.

“It’s effective and that’s the point. It is the most effective way of stopping people using weapons against each other that we can readily deploy. It’s also the most dangerous way of alienating particular groups of the community.” (Authorising Officer 1 – ‘original’ force)

“The community impact was something we needed to monitor, manage and deal with, but also dealing with the suspects so that the 2 in combination, were important to me.” (Authorising Officer 6 – ‘later’ force)

Examples were given where AOs had reached out to community leaders prior to an authorisation being agreed, to glean how a proposed s60 would be perceived within a local area. Several AOs stated that if, on balance, a s60 was viewed as counter-productive by the community, then the risk that this might damage local confidence in the police in the short term had to be reflected in the decision-making process. One AO went further and highlighted the potential longer term impact of alienating the next generation, or damaging long term preventative work.

“The communities feel very strongly about section 60 and so you’ve got to be very mindful about a short-term impact versus long-term impact. So short-term impact actually there’s suppression but the long-term damage of that relationship with the young people or the long-term damage of being able to do other work to prevent violence and other work.” (Authorising Officer 2 – ‘original’ force)

Amongst community scrutiny leads (CSLs), the importance of including community views in the authorisation decision-making process was deemed critical. As one CSL put it, this was about bringing “the community along the way and ‘involv[ing] them as part of the process” (CSL9 – ‘original’ force). That same CSL also reflected that the high watermark of consultation had passed and felt it had peaked just prior to the introduction of the Best Use of Stop and Search Scheme (BUSSS).

“There’s not the lead-in like when they did … going back 4 to 6 years ago, when they had to do that community engagement. They don’t necessarily have to do that now. So, that’s something they could just put in place.” (Community Scrutiny Lead 9 – ‘original’ force)

3.3 Parameter setting around s60 authorisations

Since all s60s are set by time and place parameters, decision making on the geography and duration are critical elements of authorisations. Information on geography, duration and the reason for the s60 are routinely recorded in forces’ standard authorisation forms (and were separately subject to more detailed analysis for a sample of pilot forces, see Diver et al. (2023)). The use of intelligence to inform how the authorisation is operationalised was also mentioned by a small number of interviewees.

Setting geographical parameters for authorisations

Interviewees were asked to reflect on whether the same locations are being subject to s60s following the pilot and whether there has been a change to the size of the area authorised. Most interviewees – understandably given the change in authorising rank – found it difficult to give a fully rounded answer to this question, and those who did offer a view gave rather mixed responses.

In relation to the areas being authorised, a frequently mentioned view was that the geography of a s60 is mostly dependent upon and tailored to the related circumstances and intelligence. Interviewees who commented on whether there has been a change to the locations where authorisations were happening generally felt that they have remained the same, as they are closely linked to where serious violence has occurred and where gangs are based and operate.

CSLs offered little in the way of specific views on area targeting. This was partly due to the lack of provision of specific details on where s60s have taken place, itself due to the relative infrequency of s60s and lack of specific s60 scrutiny. A common CSL observation was that s60s are an acceptable power for dealing with specific circumstances, but s60 authorisations should not become a routine way for dealing with a particular area. The critical point here was for the police not to see s60s as an alternative to longer term problem-solving, thinking and initiatives. One example was given by a CSL where a s60 prior to the pilot was understood to be city-wide and in place for an extended period, although in practice certain areas of the city were targeted at particular times. This city-wide approach to a s60 was not viewed in positive terms.

Over half of interviewees who had a view on whether area size has changed, felt that there had been no change to the size of the area since the pilot. One stop and search lead (SSL) felt that inspectors may have authorised slightly larger areas than chief officers. Several interviewees did feel that smaller, more specific, authorisations were being given now than they were in the past. Where previously authorisations were given for ‘whole’ areas, such as entire cities, before the relaxations, these interviewees felt that intelligence was increasingly being used to define smaller, more targeted s60 areas. While another AO agreed that the tendency to target smaller geographical areas had increased, he felt that this shift actually started before the pilot. One of the SOs also commented that they thought areas are smaller now because violence is occurring in smaller pockets, suggesting that the change in area may be related to the changing nature of serious violence. Some interviewees hinted that authorisations covering larger areas might simply represent less thoughtful targeting of a s60. The argument was that better local knowledge of tensions and territories meant that inspectors were better aware of where problems might arise (spillover areas).

Operationalising intelligence

A minority of interviewees stated that in some situations the intelligence case informing an authorisation might identify the demographic profile of those who have been assessed as being involved in, or likely to be involved in, past or future incidents linked to an authorisation. For example, known members of gangs, those falling within a specific age range or from a particular ethnic background could be part of the demographic parameters of an authorisation. One searching officer (SO) explained that frontline officers have to take into account any parameters set for the authorisation and apply a common-sense approach in how this was applied in practice. However, there was some recognition that s60s can be implemented subjectively by SOs.

“Officers go out there to do their job and section 60 is, you know, any person, male, female, age is irrelevant. Clearly if, we’ve got an incident say that’s say teenage gang-related then someone of another age is not going to get stopped generally […] because they don’t fit the demographic of the crime that’s happened. But I don’t think any cultures are necessarily targeted and it is an unfortunate part, you know, [X] got many different races, cultures and if you go to an area, you are going to find more [of] one than […] another.” (Searching Officer 5 – ‘original’ force)

“… or whoever it might be, whatever ethnic background. So those people committing those offences, if we’re, for example, targeting that area for violent crime using a section 60 or whatever it might be, those are the people that are going to be in the parameters for being stop searched … So I think, again, that’s so hard to get across to the public, that actually the reason why you were being stopped is because you’re in the suspect parameters, in obviously the crime that’s being committed.” (Searching Officer 10 – ‘original’ force)

There was near consensus across the scrutiny leads that people searched in a s60 area should not be picked indiscriminately. However, a counterview was presented that isolating those to be searched purely to a specific set of demographic characteristics could lead to stopping the same people repeatedly, while others slip through the net. It could also lead to a perception in the community that those from a particular demographic group in the local area are more frequently targeted for searching than others.

“My personal view is that this is a useful tool [in the context of serious violence] but that should be very much a targeted approach. That should not be anyone.” (Community Scrutiny Lead 9 – ‘original’ force)

“We have confidence that if they are doing section 60s or stop and search, it’s intelligence based, whether the outcomes happen or not is, is not what we, what we’re looking at.” (Community Scrutiny Lead 2 – ‘original’ force)

“As I’ve said many times, that girl or that older woman walking past with a gun in their bag, you’ve just missed because you’ve got these kids up against the wall.” (Community Scrutiny Lead 9 – ‘original’ force)

The Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS, 2021) spotlight report on stop and search and the use of force highlights the potential insight from considering ‘fair application’ – that is, whether people searched under each authorisation match the information on which that authorisation is based when looking at the disproportionality rate in section 60 searches. HMICFRS have plans to develop this as a measure for s60s in the future.

Setting durations for authorisations

The maximum allowed duration of a s60 authorisation was extended in the pilot, along with changes to the rank needed to extend an authorisation and the duration for extensions. These relaxations will be specifically discussed in Chapter 6.

Regardless of the duration of initial authorisations or extensions, several interviewees highlighted that s60s need to be ‘proportionate’ to the circumstances. Temporal data, intelligence, resources and the likelihood of an incident occurring were all reported by interviewees as factors that influence the setting of time parameters.

The use of extensions was infrequently reported by interviewees from both the ‘original’ forces and the ‘later’ forces, although it was remarked that the potential use of extensions was often considered when setting the time parameters for the initial authorisation.

3.4 The relationship between resources and s60 authorisations

The link between s60s and resources was a common theme in the interviews. Resource availability – the number of police officers available to run a s60 – was specifically mentioned by some AOs as a critical factor to consider when deciding whether to authorise a s60. For them, the need for ‘sufficient’ police resource was believed to be essential in delivering an effective s60. One AO from a ‘later’ force also noted that resource constraints militated against extended authorisations, for example, around 48 hours long. Indeed, in some forces, the process of authorising s60s, could in itself be a trigger to bring extra resources into an area from elsewhere in the force. In this sense, s60s became, in part, a mechanism by which force-wide resources were allocated. In other words, they functioned as part of the internal resource deployment mechanisms.

“One of the issues you have with this tactic is it depends on how many resources you have for it to be effective, and so clearly it, it works better if you’ve got more resources.” (Authorising Officer 6 – ‘original’ force)

“… there’s so much thrown at them on the frontline, there’s so much demand placed on them and then we throw in something else, and it’s quite resource intensive to do a section 60. So we’ve got to get our resources together to do a proper section 60, we can’t use 2 officers. You know if we have a large group of people you need to have it controlled don’t you? So that’s the biggest sort of issue for us is perhaps the resources that are available to us, you know at our disposal, taken together with all the other demands that we’re having to face in the police force.” (Stop and Search Lead 4 – ‘original’ force)

While the importance of resources to support delivering s60s was acknowledged, there were more mixed views as to whether an absence of, or very limited, resources made s60s unworkable. Some officers argued that additional, visible resources was the active ingredient that enabled s60s to ‘work’. S60s were thought to suppress crime if they were undertaken in parallel with extra resources ‘flooding’ an area, whereas running s60s without resources simply had no impact.

“Section 60 is effectively doing that very simple thing of stopping people carrying weapons, if you tell them about it and warn them that you’re gonna do it. Now the problem is you can’t, you have to put the resource into an area to achieve that outcome, so we saw that demonstrated in areas where we put most resource in because they were using the powers, there were some areas where we didn’t have enough resource to kind of really flood an area. So you’d have the power and a small number of officers but you didn’t have the same suppression within that same reduction in knife crime because actually the resource wasn’t there to deal with that. So the kind of nuanced answer is if you have the kind of the ability to use the power and people to do so, you get a reduction in crime. Which is why when people say ‘Oh well we’ve actioned section 60, it won’t have done anything to crime rates’, that’s a slightly simplistic analysis of whether it’s had a direct result or not. You have to kind of have the sense of what has it enabled your resource to do in a particular area.” (Authorising Officer 1 – ‘original’ force)

“I think it can be effective if we have the resources to support it. So I’m quite conscious that when I’ve authorised under section 60, even though that might be a great power to use, we have very limited resources to back it up. I will usually request extra resources, and there are some extra resources that are potentially available, so that we could actually then put in place the stop/searches that are required. So actually I do think it is an effective tool, I’ve seen that we’ve come away with weapons from doing section 60s, stop searches, so if it’s taking a knife or any other potentially fatal object off the street then I think it’s a good thing.” (Authorising Officer 5 – ‘original’ force)

Pressures and issues around resourcing were remarked upon by several of the police interviewees but opinions differed on whether a s60 should be authorised if there is not sufficient resource available. Some expressed the view that they should not be authorised if they cannot be resourced, but one AO was of the view that low resource should not be the reason for not trying it. A situation was described by one AO where the justification for a s60 had to be weighed up against the practicality of implementing it. Although content with the justification to authorise, they recognised that resourcing issues would have impacted on effectiveness.

“I think there’s no doubt about it, certainly section 60s shouldn’t be authorised if you can’t resource it. So there’s no point in my authorising a power for an area when I haven’t got any police officers to go and search in that power. But undoubtedly if you’ve authorised a section 60 and there are officers in that area it will deter crime because those officers will know there’s a power on and they’ll be there to try and deter crime so it’s going to deter crime because there’s a police presence in that area who are stopping and searching people, so whether they find things on those people or criminals don’t go to that area because they know the power’s on and they’re more likely to stop.” (Authorising Officer 9 – ‘original’ force)

3.5 Summary

This chapter has shed some light on the decision-making process around the use of s60s. Decision making around s60 can arguably be divided into 2 elements: an initial decision on the case for using a s60, and whether it is the most appropriate approach to a problem, taking into account alternatives, and balancing against the impact on the community. And once this decision is made, a set of secondary decisions around its operational parameters on timing, geography, focus and access to resources follow.

Some officers gave thoughtful and well-articulated accounts of their decision-making process, structuring their thinking around the College of Policing’s NDM. At its best, this process extended to fully considering the wider community impacts of a s60 and fully assessing the scope for alternatives. A minority of officers took a narrower view of their responsibilities for dealing with the wider community impacts of s60.

Some officers expressed concerns around the use of s60 over alternatives. Examples were given where s60s had been authorised when a s1 would have been more appropriate given that this issue was a named individual. Others were more concerned about the risks of moving towards s60s as a routine, short-term – almost knee-jerk – response to violent incidents, rather than one of a range of tools, to be carefully selected from an arsenal of problem-solving approaches, including more long-term solutions.

4. Perceptions on s60 and the impact on crime

Although understanding interviewee perceptions on section 60 (s60) and the link with crime was not a primary research question, nor the aim of the pilot, it is closely enmeshed with how officers viewed the relaxations. Before covering perceptions of the relaxations, it is therefore helpful to set out how the interviewees saw the relationship between the authorisation of s60s and crime levels. The main focus here was on s60 authorisations, rather than the more general relationship between stop and search and crime.

There was a broad consensus that the question of the relationship between s60s and crime was complex. Few interviewees were willing to offer a view on the relationship between the relaxations themselves and crime, given the wider complexities and the modest change to the conditions. The minority who did suggested that there were only very marginal impacts.

Interviewees tended to have more clarity in their views about how s60s might more generally impact on crime, but there was no consensus. It is helpful to try to group these views by theme. Officers at all levels, and community scrutiny leads (CSLs), offered thoughtful observations on how they perceived the way that s60s might impact on crime at the local level, although others were unclear. A minority of officers, and a higher proportion of CSLs, were doubtful that there was any discernible impact on crime.

Four main types of ‘s60 – crime relationships’ were offered by interviewees. In short, these were views about how authorising s60s might ‘work’ in reducing crime. The first focused primarily around the detection of weapon carriers by carrying out searches under a s60. The remaining 3 all suggested that a s60 acted primarily through deterrence rather than detection, through the imposition of the s60 authorisations. However, there were variations in the precise mechanism at work, through:

-

an increase in police visibility

-

communication with would-be offenders

-

a narrow form of reducing the threat of serious violence

4.1 Detection and apprehension of weapon carriers

The potential value of stop and search as a mechanism to investigate and detect serious crimes has been suggested in the wider literature (see for instance, Bradford and Titarelli, 2019). Several interviewees emphasised the importance of s60s simply as a mechanism to detect weapon carriers, which both removed weapons from the street, and would lead to offenders being apprehended. However, a number of CSLs noted that ‘hit rates’ within s60 searches were typically low, noting that if s60s do ‘work’ via this mechanism, they may not be particularly efficient. Other interviewees, including some officers, were simply sceptical that this was the primary benefit of authorising s60s.

“I think the whole issue with detections with section 60 is that I imagine the section 60s are fairly low, compared to other search powers, but I just don’t think that’s where the main value of it lies. Really, I think it’s, well, just extremely valuable as like a deterrent for all violence, if you see what I mean.” (Searching Officer 6 – ‘original’ force)

4.2 S60 authorisations, police visibility and increased offender risk

Other interviewees suggested that, if there was a ‘core’ crime suppression ingredient from s60 authorisations, the key agent for change was not through the process of stopping and searching individuals. Rather they suggested it was driven by greater police visibility – the consequence of a s60 authorisation – and perceived increases in the risk of apprehending would-be offenders. This is in line with the proposition that if there is a s60 stop and search effect on crime, it may more accurately be a response to the impact of focusing additional, highly visible resources, in crime ‘hotspots’. The actual activity of undertaking stop and searches was, for some interviewees, at best marginal to the process – visibility in hotspots was what mattered.[footnote 6] However, concerns were raised about the possibility of displacement of crime to adjacent areas.

“I think there’s a degree to which because there were more officers on the street, some people made their own personal decisions that they weren’t going to go out and carry knives. Then I think there was a degree to which people that were going to go there anyway and might have had a chance dispute, the kind of increased visible presence made that less likely. But what it didn’t do, ‘cos we saw evidence of where there were sort of, for example, drug groups or gangs that had a specific desire to fight each other, they found a way to do it anyway. because where, we had instances where people were seen in the hotspot area, left the hotspot area and then there was disorder round the corner, which goes back to the displacement effect.” (Stop and Search Lead 3 – ‘original’ force)

“One of the questions that our panel actually raised was, is it about the actual physical presence of officers on the street that can cause a reduction in criminality or negative things happening, or is it actually the stopping and searching? And that’s the thing that we’re kind of like,… well is it just more about more physical presence and rather than doing section 60, should they just, rather than doing section 60 and stopping and searching a load of people, should they just be a more visible presence?…” (Community Scrutiny Lead 1 – ‘original’ force)

4.3 S60 authorisations, proactive public communication and increased perceived offender risk

Some police officers acknowledged that increasing perceptions of offender risk was the active ingredient to deterring offenders, but did not believe that increasing visible presence in an area was critical to achieving this. For these officers, the emphasis was on using communications around an intended s60 as the one of the main mechanisms to deter would-be offenders, rather than undertaking large volumes of stops or increasing the actual presence of officers in an area. The importance of public communication has been identified in other studies (for instance Crawford and Lister’s assessment of dispersal orders, [2007]; Kennedy, 2009). Public communication of authorisations will be discussed further in Chapter 6.

“I think it’s amazing. I think it’s one of the things that is clearly open to abuse because the freedom it gives police officers to search people is quite vast; as long as that’s not misused it’s a great tool. My perception of it though is that it is a great tool first and foremost and secondly you don’t need to get positive results out of it, such as arrests for knives, for it to work. I’ve searched a lot of people in my time in the police and from just speaking to them they know what a 60 is. I’m talking about the targeted demographics who I know and have arrested many times for drugs, weapons, knives, gangs, they know what a section 60 is and within sometimes 10, 20 minutes of a section 60 being authorised they will not be on the street […] or if they are on the street they won’t be carrying anything.” (Searching Officer 3 – ‘original’ force)

“If there was a section 60 in place and they became aware of that, then it would [have an impact on crime], because they [the potential offenders] know that when we’re around in that area, that there’s an increased chance of being stopped and searched. We know from information we’ve had from the community that the drug dealers and other people that are out doing things, won’t come out. They’ll stay indoors, they’ll keep off the streets and out of the way, so it does [have an impact on crime]. Once that information’s common knowledge, which needn’t take long – once you’ve stopped one person, if you’ve stopped the right person, that information is quickly spread via their network of phones – so then it does have an impact.” (Searching Officer 12 – ‘original’ force)

4.4 Targeted reduction in the threat of serious violence

A final variant on s60 as a tool to increase offender perceptions of risk was that s60s should be viewed as a distinct threat reduction tactic, rather than a mechanism to reduce crime. The argument was articulated as follows. S60s are fundamentally put in place to prevent a specific threat of serious violence. Their effectiveness has, therefore, to be viewed in terms of whether they succeed in stopping that specific, intelligence-driven, threat. Any potential collateral benefit from s60s on suppressing ‘background crime’ was far less relevant to the core s60 objective than the result of the specific threat of violence set out in the authorisation. This view carried with it consequences for any measurement of effectiveness, as the ‘outcome’ was reducing the threat of a small number of very serious offences linked to the original authorisation, not a more general reduction in crime.

“I think on a positive, when it’s in response to some intelligence or a set of circumstances, we’ve used it in response to sort of intelligence about gang fights or following a sort of stabbing in an area, we’ve put it in place as effectively reassurance and deterrent as well, and that’s worked overwhelmingly effectively, both in terms of some good results we’ve had from it and the feedback from the public, on social media in the main, has been resoundingly positive.” (Stop and Search Lead 1 – ‘later’ force)