The impact of Tax-Free Childcare on the labour market participation of working parents

Published 21 September 2023

The impact of Tax-Free Childcare on the labour market participation of working parents

Qualitative Research, July 2023

Research Report 723

Authors: Ipsos UK

Jack Watson, Noah Coltman, Rosie Gloster

© King’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2023.

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

Published by HM Revenue and Customs, September 2023

1. Summary

1.1 Introduction and background

Tax-Free Childcare (TFC) is a government scheme that offers up to £2,000 a year per child towards childcare costs, or up to £4,000 a year if a child is disabled. To be eligible, parents must be in work and earn the equivalent of at least 16 hours per week at the National Minimum Wage and no more than £100,000 each per annum, although there are some exceptions to this such as being on sick or parental leave. Children must be 11 or under, or 16 and under if they have a disability, and usually live with the parent.

This research aimed to assess the extent to which TFC influences the work and childcare choices of working parents and provide an understanding of the links between TFC and labour market participation, such as whether TFC supports the labour market participation of these parents.

Sixty-one in-depth qualitative interviews were undertaken between February and April 2023 with users of TFC, eligible non-users who were aware of the scheme, and eligible non-users who were unaware of the scheme.

1.2 Work context

Participants worked a variety of roles ranging in sector, seniority, and flexibility. They reported a range of benefits from work, with some focused more upon the financial benefits whilst others viewed work as a way to progress and develop.

Work flexibility, regarding both where and when to work, positively affected working parents’ labour market participation. Where they had the opportunity to work flexibly, this was a key enabler to support their continued working, as well as a key means to reduce formal childcare costs.

Greater hybrid working in office-based roles since the COVID-19 pandemic had enabled more flexibility for working parents, minimised travel time, and reduced childcare costs. Parents working shifts, or atypical hours, discussed organising their working hours around childcare availability where possible and reported managers enabling and supporting them in this regard.

1.3 Childcare use and preferences

Dual parent households ideally aimed to share the responsibilities of childcare and organised these responsibilities around work schedules. Mothers’ working lives were more likely to have adapted and changed following childbirth. Single parents often relied on family or childminders, who could provide greater flexibility, to maintain their participation in the labour market.

A wide range of formal childcare was used. Choices were influenced by a parent’s employment type, the child’s age and whether informal support networks were available. The most important factors influencing choice of childcare provider were convenience, the perceived quality of the provision and flexibility offered by the provider. The cost of formal childcare was more important for certain families, for example those spending a large amount on childcare or those without access to informal childcare.

Outside of term-time, holiday clubs were considered and used by some to allow them to continue working. However, this provision was an irregular cost and out-of-reach for some lower income families. Working parents instead had to coordinate annual leave around holiday periods or rely on informal support to ensure their childcare needs were adequately covered.

Working parents held mixed views on the availability of local childcare but overall, after adjusting their expectations or managing to secure their child(ren) a place at a provider, felt satisfied that it met their needs.

1.4 The cost of childcare

Formal childcare costs varied for families over time and reduced significantly at points (for example, the term before a child turns 3 they become entitled to free childcare hours). Families with children aged under 3 therefore frequently had the highest childcare costs.

Formal childcare costs varied from around £80 to over £1,000 a month among the families interviewed, representing very different proportions of household income.

Working parents sought to minimise formal childcare costs. The household context, work flexibility, and use of informal childcare were effective ways to gain the maximum financial reward from working and reduce formal childcare costs.

1.5 Awareness and use of Tax-Free Childcare

Participants who were aware of, or using, TFC tended to hear about it by chance, with awareness of the scheme coming via word of mouth. Aware non-users had different levels of knowledge about the scheme, with some only knowing the name whereas others knew that it was an online account or the level of government contribution. There was a certain degree of understanding of the kinds of childcare that could be paid for using TFC, including an assumption among non-users that it was registered childcare providers, but surprise it could be used for registered holiday clubs and interest-led activities, like ballet classes or musical instrument lessons.

Non-users of TFC generally assumed they were ineligible because they were unable to claim other government support. Once told details of TFC and the eligibility criteria, all parents realised they were eligible and usually indicated an interest in researching further and potentially registering.

Users found the TFC online account and finding providers mostly uncomplicated but outlined a few things they found tedious. These included the 3-month reconfirmation period, the time delay between depositing money and it entering the account, only having one parent able to manage the account and the manual process of updating during holidays or months with 5 weeks.

1.6 Labour market participation and Tax-Free Childcare

The household context, work flexibility, and use of informal childcare were typically more thought about ways to reduce the cost of childcare, rather than contemplating use of TFC.

Household context enabled work where it created opportunities to balance work and childcare in the way preferred by parents. For example, in dual parent households, parenting responsibilities could be shared and working hours staggered. Single parents with regular shared custody arrangements were also enabled to manage work and family life by sharing childcare responsibilities with the other parent. This option was not available to single parents without shared custody arrangements.

Working parents were often supported to work by informal childcare. Parents drew on informal care to manage early starts or late finishes to working days where the available childcare could not accommodate this. If formal childcare was more affordable, there were families who would redesign their balance of informal and formal childcare, with more use of formal childcare. The current offer of TFC was not a sufficient financial contribution to childcare costs for arrangements to be redesigned.

Working parents that were eligible for TFC with young children tended to view the period of high childcare costs as temporary. They felt that childcare costs would reduce in time as children grew older and they received funded hours or started school.

Among users of TFC with older children, and those that spent less of their household incomes on formal childcare each month, TFC was often viewed as ‘nice to have’. For these users, it neither determined their work patterns, nor made a significant financial difference. Their labour market participation was more strongly influenced by factors such as a sense of career or availability of informal childcare. TFC had the most financial impact where childcare costs were a large part of the household budget, and for families with lower earnings.

Participants mentioned that their usage, or whether they would consider using TFC were affected by features of TFC’s design and implementation, such as eligibility criteria, awareness raising campaigns, and ease of use of the online account. They noted that greater awareness and understanding of eligibility for TFC might encourage more use.

Despite being applicable to a range of childcare settings, when asked what could increase their use of TFC or persuade them to start using TFC, some parents suggested extending the providers that can be paid using TFC to include sports and arts clubs and other interest-based activities that are not regulated. This change could benefit parents of school-age children, particularly to support them to work during school holidays when childcare costs are high.

Users suggested some changes to the design of TFC that would further reduce their childcare costs. For example, increasing the maximum government contribution to TFC accounts from £2,000 (suggested by high formal childcare users). Higher rate taxpayers suggested the value of the government contribution to TFC could be increased in line with the higher tax rate.

Overall, TFC helped to maintain working patterns among users and made a contribution towards the affordability of childcare. However, the labour market participation of working parents was influenced by a wide range of factors and was typically driven by things other than TFC. The relative financial importance of TFC to families was affected by the proportion of household income spent on childcare, total household earnings, the age of the youngest child, eligibility for other childcare offers and the number of children within a household.

2. Introduction

Tax-Free Childcare (TFC) is a government scheme that offers up to £2,000 a year per child towards childcare costs, or up to £4,000 a year if a child is disabled.

This research aimed to assess the extent to which TFC influences the work and childcare choices of working parents and provide an understanding of whether TFC supports the labour market participation of these parents.

Sixty-one in-depth qualitative interviews were undertaken between February and April 2023 with users of TFC, eligible non-users who were aware of the scheme, and eligible non-users who were unaware of the scheme.

2.1 Research background

Tax-Free Childcare (TFC) is administered by His Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) and is available throughout the United Kingdom (UK). The scheme offers eligible parents the opportunity to set up an online childcare account for their child. For every £8 a parent pays into this account, the government pays in £2, up to a maximum of £2,000 a year per child. One parent has the administration rights for the account, and eligibility is validated every 3 months.

Eligibility for TFC depends on the child’s age and circumstances, and the working status and income of the parent(s). To be eligible for TFC, children must be 11 years old or under and usually live with the parent. A child stops being eligible on 1 September after their 11th birthday. If a child is disabled and usually lives with the parent, they may receive contributions to childcare costs of up to £4,000 a year until 1 September after their 16th birthday.

Both parents, where applicable, must be in work or self-employed. Each parent must earn at least the equivalent of 16 hours per week at the National Minimum Wage, and each have an income of no more than £100,000 annually. In March 2023, approximately 477,000 families used TFC for 577,000 children.

TFC is used to pay regulated providers. In England, this regulator is Ofsted, although the regulator varies based on which nation the childcare provider is registered in. These settings include nurseries, playgroups or preschool, holiday clubs, out of school clubs (for example, breakfast clubs), activity clubs, childminders and nannies. Families in England can use TFC at the same time as the 30 hours free childcare offer if their children are aged between 3 and 4 years old.

The wider Department for Education (DfE) free hours offer in England includes 15 hours universal free childcare for 3 to 4 year olds and an additional 15 hours free childcare for working families with children aged 3 to 4, totalling 30 hours. Additionally in England, there is 15 hours free childcare for disadvantaged 2 year olds. Partway through fieldwork, there was a budget announcement by the government to expand the offer of 30 hours free childcare per week for eligible working parents with children aged 9 months to 3 years. Each UK nation has different government childcare offers.

Northern Ireland: All parents of children aged 3 and 4 year olds can apply for at least 12.5 hours per week of funded pre-school education (during term-time for the year immediately before starting primary school).

Scotland: All children aged 3 or 4 years old, can access up to 1140 hours of funded early learning and childcare a year (around 30 hours a week in term time). Some 2 year olds are also eligible, depending on family circumstances.

Wales: The Welsh Government offer 30 hours of early education and childcare aged 3-4 in Wales for eligible parents for 48 weeks of the year. The 30 hours is made up of a minimum of 10 hours of early education a week and a maximum of 20 hours a week of childcare. The Welsh Government also provides the Flying Start programme which includes 12.5 hours of funded childcare a week for children aged 2 to 3 years in disadvantaged areas of Wales.

2.2 Aims and objectives

The research aimed to:

-

assess the extent to which TFC influences parental work and childcare decision making

-

provide an understanding of the links between TFC and labour market participation

2.3 Overview of methodology

Qualitative interviews were chosen to provide depth of insight and to capture the nuances behind working parents’ childcare needs and their labour market participation. Sixty-one interviews with parents from all 4 UK nations, all eligible for TFC were completed. The achieved sample included 20 TFC users, 20 eligible non-users who were aware of the scheme, and 21 eligible non-users who were not aware of TFC. Given the variety of circumstances of working parents, quotas were used to structure the achieved sample and ensure representation of parents with a range of circumstances.

As secondary criteria the research aimed to recruit a diverse sample with variety based on several factors including household income and the age of the youngest child. Full details of the sampling, recruitment, fieldwork, and analysis are included in Annex 1 with an overview provided here.

Two sampling approaches were used. A sample of TFC users was provided by HMRC. Non-users of TFC were recruited via a free-find method. The number of completed interviews by participant group are shown in Table 1.1.

2.4 Table 1.1 Completed interviews by type

| Tax-Free Childcare (TFC) awareness and use | Number of interviews (61) | Sample source |

|---|---|---|

| Tax-Free Childcare (TFC) Users: parents who have a TFC account and have reconfirmed their eligibility within the last 3 months. | 20 | HMRC data |

| Aware but don’t use TFC: Parents eligible for and aware of TFC but do not have an active TFC account | 21 | Free-find |

| Unaware and don’t use TFC: Parents eligible for TFC but not aware of TFC | 20 | Free-find |

Analysis was undertaken using the framework method. This included writing detailed notes and quotations and interrogating the data to look for patterns. This was supplemented by using the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour (COM-B) model (Michie 2011) as a lens to interpret the qualitative data, and understand the varied and competing opportunities and constraints on working parents’ labour market participation, and the role of TFC.

2.5 Structure of this report

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

-

chapter 2 details the work context of the participants

-

chapter 3 details the childcare use of participants and their preferences

-

chapter 4 sets out the current awareness and use of TFC, including its interaction with other government childcare offers

-

chapter 5 presents findings on the influence of TFC on working parents’ labour market participation and the weight in relation to other influences

-

chapter 6 summarises the findings in relation to the research objectives

3. Work context

This chapter details the types of work participants undertook, their attitudes towards work, and the availability of work flexibility.

3.1 Types of work undertaken by participants

Participants worked in a range of roles that varied by sector and seniority. There was variation in the length of time participants had worked in their current role, with some having been in their roles for several years and others having started within the previous year. Users of TFC were often in professional and office-based roles, and they tended to have higher level qualifications than non-users. Users were employed in a range of sectors, including roles in the Civil Service, medical professionals, and education. These roles often allowed for flexible working.

3.2 Work flexibility

Working parents reported that their employers allowed a degree of flexibility. They were often able to work hours that best suited them. For example, one participant was able to work a 4-day contract in 3 working days, to ensure that she had an additional day to spend with her child. There was a sense of general flexibility in the times participants could start and finish their working day, and the time when they could schedule breaks for collecting children from school or childcare provision.

There were exceptions to this type of work flexibility, primarily for parents that worked atypical hours, such as in hospitals. These working parents tended to work long hours in a single shift, and hours outside the 9am to 5pm. Lacking the flexibility that other participants had in their working patterns meant accessing formal childcare could be more difficult, and working parents were reliant on informal childcare networks to provide flexibility. These participants often had lower levels of income than parents working office-based hours and expressed lower job satisfaction.

Among parents that worked part-time, the primary factors in their decision to do so were to reduce childcare costs and to increase the amount of time they spent with their children. Patterns of part-time working were diverse. There were working parents who worked compressed hours, for example fitting 5 days of work into 4, and others that reduced their total number of working hours.

Work flexibility, both in where and when to work, positively affected working parents’ labour market participation. Where participants had the opportunity to work flexibly, this was a key enabler to support their continued working, as well as a key means to reduce formal childcare costs. When determining their working patterns, working parents considered how to maximise their working hours, and minimise formal childcare costs.

There were examples of dual parent households staggering working hours, with one parent starting work earlier than the other each day, such as 7am, while the other took the child(ren) to school or nursery. This helped families to reduce formal childcare costs and be around to look after their child(ren), while maximising working hours.

Where parents had flexibility in where and when they worked, they might restart work in the evening, once children were asleep. This was particularly common for parents in senior, corporate roles.

“I have to be strict with my timings and that is down to my costings, and keep costs down to a minimum. If I need to work later, then I need to find alternatives.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, >£50,000 (ID3)

Several participants in office-based roles noted that an organisation-wide move to hybrid working following the pandemic had enabled greater flexibility in their role. The flexibility in where to work reduced travel time to and from work, and therefore childcare costs. In cases where dual parents both had roles they could work in a hybrid manner, they used this flexibility to work from home to reduce the use of formal childcare. This minimised their use of early morning drop-off settings or late finishes. However, this form of work flexibility was not available for all, such as those working in schools or health care who needed to attend a specific place of work.

Some single parents were working from home due to increased flexibility post-pandemic but were not always able to look after their children during these times and still had to use formal or informal childcare. Other single parents worked in part time roles and were still required to work in an office or a set location outside of the home.

Parents working shifts, or atypical hours, discussed organising their working hours around childcare availability where possible and reported managers enabling and supporting them with this. For instance, one participant in a dual parent family where both parents worked shifts arranged to mirror each other, so that whoever was on their 5-day break from shift work had responsibility for childcare while the other worked, and vice versa. The formal childcare cost savings that could result from work flexibility were significant. Where unplanned work required parents to unexpectedly work longer hours, this could create additional childcare costs.

“I have to run my diary around the childcare, I get charged an extra hour if I am late. If you're on call it's very hard."

Aware Non-User, Female, Single parent F/T, <£30,000

3.3 Attitudes to work

Work was important to all participants in the research. It was common for female participants to have had periods of parental leave, and those that had young children had recently returned to work. Other participants, usually males, had worked consistently throughout their lives. Participants emphasised the length of time that they had been working, with some expressing pride to have been working since the age of 16.

Working parents believed that being employed made them a role model for their children. They felt it was important to show their children that work was an aspect of life, and that as an adult they would need to work to progress and finance their lives. Having the financial stability that work could provide was also important.

"I've always worked and I was brought up to work. When we were 16 we got Saturday jobs, and to me it's important. Being a single mum I didn’t want my kids to be brought up seeing you could sit around and do nothing. I want them to know you have to work hard to get what you want".

Aware Non-User, Female, Single parent F/T, <£30,000

Financial independence was a common theme that emerged, especially amongst female participants. Having an independent source of income gave them a feeling of agency and reduced traditional stereotypes that the father should provide the main income for a family.

While work was important to all participants, they attached different meanings to it. Progressing in a career and developing in both a personal and professional manner was a way to draw meaning in their lives and have opportunity for challenge. Work had broader benefits and was not simply undertaken for financial reasons. Users of TFC were more likely to view work through this lens.

“Work means I’m able to continue to provide for my children and maintain a career at the same time. Progression is very important; my manager is retiring so I want to progress into his role and feel able to take the opportunities when they arise”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent F/T, £30,000 to 50,000

Other participants primarily valued work for the financial benefits it provided. Work was undertaken to pay bills and finance family life. Opportunities to progress at work existed for these working parents but their preferred work and home life balance were more important. Some participants who worked part-time highlighted that working allowed them to afford treats, such as additional holidays. Work was something they had to do to enjoy other areas of their lives.

“Work is important because I have children that I need to feed and provide for. I’m planning to get married and with [the] cost of living, working is essential. It’s a way to keep everything around me happy and functioning.”

Unaware Non-User, Male, Dual parent F/T, >£50,000

Over the pandemic, some participants felt their attitudes towards work changed. They became more focused upon having a good work-life balance and found space to ‘step back’ and reconsider their priorities in life. This meant they wanted to focus less upon work and more on their family. These feelings were especially pronounced amongst working fathers, who had re-evaluated the amount of time they spent at work in comparison to at home with their families.

“So as much as I love my job, and I'm really committed to my job, I also want the balance of family life, to want to spend time together and enjoy it.”

Aware Non-User, Female, Dual parent F/T, >£50,000

While the meaning attached to work could differ, parents recognised there were other benefits to working. For example, the value gained from feeling purposeful and maintaining a sense of self, and the personal benefit of being away from the home to engage with other adults.

“When we got married and I had my first child, I stopped working and I found it very difficult no longer to have that financial independence. I fell into the role that I am someone's mum, and I felt I lost my identify a little bit. I like to work. It is a little bit of me time."

Aware Non-User, Female, Dual parent F/T, £50,271 to £99,000

There were also parents for whom work had provided health benefits. This is exemplified in the case of a TFC User from Northern Ireland. They worked as a Civil Servant. Work had always been an important part of her life, and she derived meaning from making a difference to others in her community. After giving birth to her second child, she experienced post-natal depression. She reflected that returning to work supported her recovery. The benefits that she found from work reflect on the wider experiences many had, such as allowing her to have a separate identity and progress in different areas, giving a sense of achievement.

"In terms of my recovery, work has played a big part in that. I need to have that sense of achievement and getting out there and doing things. I struggled with my identity being at home all the time, you also need to have those outside interests and opportunities. If I had not been able to go back to work, I don't think my recovery would have been so good".

TFC User, Female, Dual parent F/T, £30,000 to 50,000

4. Childcare use and preferences

This chapter details the childcare used by working parents. It covers how childcare responsibilities were shared between dual parents and what influenced their choice of childcare. It discusses differences in childcare use between term-time and school holiday periods and the extent to which available childcare met the requirements of working parents.

4.1 How childcare responsibilities are shared between parents

In household situations where there were 2 working parents, couples ideally aimed to share the responsibilities of childcare. These parents organised childcare responsibilities around their working schedules and when they were available to look after the child(ren) themselves.

For example, if both parents had regular working hours during the week, they typically had committed and consistent childcare responsibilities that fitted around their working patterns and time spent outside of the home. In practice, this meant sharing responsibilities like dropping a child off at school, picking them up from a childcare provider or regularly helping with specific activities like bath times, reading a story or putting a child to bed.

Dual parent households organised these responsibilities based on which of them was not working at a certain time, with some parents slightly adjusting their working hours to be able to fulfil these specific roles. When both parents were free, for example at weekends, families looked to spend dedicated time together and share childcare fully and not use formal childcare providers.

“In some ways it’s traditional: I run the house and he runs the business. But in terms of childcare, he definitely pulls his weight and does a lot during certain parts of the year or when I’m busy.”

TFC User, Female, Dual Parent one F/T one P/T, <£30,000

There were some examples of traditional gender roles being reinforced, with fathers continuing to work whilst mothers had more responsibilities in the home. In dual parent households, it was the mothers’ working lives that tended to adapt to new responsibilities following childbirth. This often meant the mother changed their working hours from full-time to part-time, had more caring responsibilities for their child and was responsible for finding and organising formal childcare.

“I probably do the lion's share of the organising and sorting it all out. My husband's a very hands-on dad, but his job has a bit more responsibility than mine so I generally pick up the slack in terms of coordinating.”

TFC User, Female, Dual Parent F/T, £30,000 to 50,000

Single parents who were working could not always rely on a second parent to fulfil childcare responsibilities. This required them to rely on family or childminders in some instances if they were to maintain their participation in the labour market. In cases where single parents did not have access to a family network or could not afford to pay for childminders or nannies to take on responsibilities like drop-offs and pick-ups, childcare dictated the extent to which they could work. If single parents were required to personally drop-off or collect children from formal childcare like breakfast or after school clubs, this would dictate their working hours as the times for these provisions are inflexible.

4.2 Types of childcare used

A wide range of formal childcare was used by working parents. These included nurseries, pre-schools and playgroups, breakfast and after-school clubs, childminders, and activity clubs like ballet classes or football practice. Some parents also used holiday clubs. The types of childcare used were influenced by a parent’s employment type, the child’s age and whether or not informal support networks were available.

4.3 Employment type

In household situations where both parents worked full-time, their children were normally in regular care at a fixed location multiple days a week. A fixed location was chosen both for the benefit of the child, to provide a sense of continuity and routine, and for the parents, so they could organise and create a schedule to abide by.

If one parent in a dual parent household worked part-time, usually the mother, then parents devised routines to place their child in formal childcare around the working pattern of the part-time worker. During the times where the part-time worker was not working, this parent looked after the child at home or attended activities like playgroups with their child. These parents used less formal childcare than dual full-time workers but still made use of formal childcare several days a week.

When both parents worked part-time, parents tended to use less formal childcare overall as they would try to arrange their shifts and working patterns to be out of work at different times so that one parent could look after the child while the other parent worked.

Participants who were single parents usually worked part-time so that they were able to look after their child for a sizeable portion of the week. They tended to use a similar amount of formal childcare to dual parent households where one parent worked full-time and the other part-time. If working full-time, single parents often relied on the help of family members to fill the gaps in formal childcare availability.

4.4 Child’s age

For working parents with a child too young for school, the use of nurseries and pre-schools was more common than the use of childminders and nannies. Council-run nurseries did not always offer parents the flexibility or times that they required for their child to be cared for whilst they were in work, so there was widespread use of private nurseries and day-care. Using private, formal providers gave parents the opportunity to consider re-entering the labour market after having a child as these settings were open longer, so parents could work more hours.

If a child attended school, working parents often made use of wraparound care, such as breakfast and after school clubs, and activity clubs on or next to school premises. These parents reported that once a child was in school and care was secured for a set amount of time each weekday, it was easier to consider working more hours or working for more days in total than when their child was under school age.

4.5 Informal support networks

If grandparents or other family lived nearby, then working parents made use of them to provide informal and, usually, unpaid childcare when they were available. Where informal support networks were available, for example when parents still lived in their hometown or had additional children who were also adults, parents felt more able to consider re-entering the labour market and returning to work more quickly following childbirth.

However, there were some feelings of guilt and not wanting to over-rely on grandparents or adult children. This was especially the case if families had multiple children or had siblings who also had children, as the burden placed on these informal networks could be considered too great. Some working parents also felt guilty for asking grandparents to look after their children on weekends or on evenings, as they felt they were ultimately responsible for caring for their child(ren) outside of working hours.

4.6 Factors influencing the choice of childcare

The most important factors influencing choice of childcare provider were convenience, the perceived quality of the childcare provision and the flexibility offered by the provider. Working parents valued convenience highly because it allowed them to organise the rest of their lives, including their working patterns and labour market participation, around the simplest drop-off and pick-ups possible.

In some instances, parents were willing to pay slightly more for childcare options that were most convenient to them and helped to make their lives simpler. For this reason, care provided on or next to school grounds or at the most local nursery or pre-school to their house or working location was typically preferred.

“The location and convenience of the provider is most important; it’s easy to access for me and my parents. I also liked the sessions and the activities they offer.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent F/T, >£50,000

The enjoyment of the child whilst at the provider was also viewed as relatively important. Some working parents valued regulators’ ratings, only trusting providers with outstanding ratings and researching individual providers beforehand to understand the level of care provided. Others judged the quality of care based on a child’s feedback, how well the child established themselves during open days or how well time spent at the provider socialised them with others and helped to prepare them for school.

Working parents highly valued providers who were open to last-minute changes, flexible with their offer and able to respond positively when unexpected childcare needs appeared. This was especially true for shift workers or those who worked in a different location to the provider and could not always guarantee being able to collect their child at a specific time.

In several cases, working parents identified challenges with strict opening hours of formal childcare providers which created barriers to their labour market participation and required them to rely on others, either family or childminders, to collect their child if they were unable to leave work promptly.

“Convenience is the most important. It’s at school, it’s at the same place, it’s familiar and he gets to be with friends. They’re also really flexible and there’s a website that shows if there are spaces available if you’re not already booked to attend.”

Aware Non-User, Male, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, >£50,000

Although not always the most important factor for choosing a childcare setting, the cost of formal childcare became more important for families in certain circumstances. For example, if they spent a large amount on formal childcare or did not have access to support from informal networks.

For families spending a lot on formal childcare, more than £1,000 per month in some cases for dual-parent households where both parents worked full-time, they were forced to consider the overall impact on their income of sending their child to full-time formal care. Cost also became a more prominent consideration for working parents with multiple children under school age as costs for securing childcare could easily multiply if the parents aimed to maintain or increase their working hours.

Part-time workers typically spent less overall on formal childcare but, in some cases, were still spending a significant proportion of their salary on childcare. Although a lower cost overall, to them, it was still a significant amount and made cost a more important consideration. In this way, part-time workers, usually women, constantly re-evaluated the cost of working and how financially worthwhile it was to work.

Where formal childcare costs were a larger proportion of take-home pay, like during out of school hours for children of school age, parents sought to minimise formal childcare costs by flexing their work hours or making greater use of informal childcare. However, working from home had allowed for greater flexibility in managing work and reducing formal childcare costs. Some parents, however, were reluctant to work from home whilst also having responsibility for a child at the same time, as this could lead to additional stress or not being able to effectively perform both roles.

If parents had relocated and moved away from their families, then they were less able to rely on informal childcare during times of need. If this was the case, then costs of formal childcare were brought more to the forefront as parents were required to pay for childcare whenever they wanted to or were required to work without the unpaid option being available.

4.7 Differences in childcare use between term and holiday time

Outside of term-time holidays clubs were used where working parents felt they were affordable. This form of childcare was required all-day, and therefore represented a significant irregular cost. It was therefore not considered to be an available option by all parents and reported as out-of-reach by some families on lower incomes (individual parents earning less than £30,000 per annum). These parents instead coordinated their annual leave periods around school holidays or relied more heavily on informal childcare during these times to ensure their child was cared for and they could continue to work.

“School holidays are a challenge. I try not to send them to a kids club because it’s so expensive so I try to manage by taking leave, relying on grandparents, but other than that, the kids are at home while I’m trying to work.”

Aware Non-User, Female, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, >£50,000

Where lower income users of TFC did use holiday clubs, they sought low-cost options and used family networks to reduce the overall cost of this formal care. When choosing to use a holiday club, the cost needed to be considered affordable and, as the child would be there for an extended period, it was viewed as essential that the child would enjoy spending time there.

“During holidays, I have to find an all-day provision so I’d say I use formal childcare more out of school time. I’m prepared to travel further but my son has to enjoy it and it be relatively affordable.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, <£30,000

Lower income non-users of TFC also found holiday periods to be challenging. Some working parents struggled to find alternative arrangements for formal childcare as usual providers closed and providers who were open were required for more hours, making costs increase. In these cases, parents took time off work to cover childcare, sometimes unpaid, negatively impacting their finances.

4.8 Views on the availability of childcare locally and extent to which it meets needs

Working parents held mixed views on the availability of childcare in their local area. Overall, participants seemed satisfied that local childcare met their needs, but at times this had required an adjustment of their expectations. For example, they sometimes had to increase their use of informal childcare or alter their working patterns around what was available. Others felt happy with the childcare that they had managed to secure and felt it meet their needs as they were no longer looking to secure additional hours or places.

“A lot of nurseries close to us have very long waiting lists. In Scotland, when they introduced standard nursery hours, a lot of childminders decided they couldn’t compete and went to work in the nurseries so there’s not always that choice.”

Unaware Non-User, Female, Urban Scotland, >£50,000

Those living rurally usually had fewer options to choose from unless they travelled into a local town to work and could choose from a wider range of providers in a different but similarly convenient location. Overall, views of working parents in rural areas were more mixed than parents living in urban locations, with rural childcare meeting basic needs but parents largely being left to choose from a limited number of providers.

For high quality childcare and the best rated providers, whether this be decided through regulator ratings, local reputation, or a child’s enjoyment, it was common for working parents to refer to a highly competitive environment and difficulty in securing a place. There were mentions of long waiting lists for some providers and parents being required to apply early to secure a place, in a few cases as soon as a child was born.

Overall, however, after configuring what hours could be secured at individual providers and how they could balance formal and informal childcare, working parents suggested that local childcare met their needs.

“Overall, I’ve adjusted to what is available, so my needs are just about met. If I wanted more though, it would be difficult, so I don’t want to give it a high score.”

TFC User, Female, Rural England, <£30,000

5. Awareness and Use of Tax-Free Childcare

This chapter details how users and aware non-users heard about TFC and non-users’ perceptions of their eligibility. It then covers users’ experiences of TFC and describes how TFC interacts with other government childcare offers.

5.1 Awareness and perceptions of Tax-Free Childcare

Working parents typically heard about TFC by chance, with awareness of the scheme coming through word of mouth. For example, from friends, colleagues, other parents waiting outside childcare providers, and online parent groups or occasionally health services, such as a GP, or their employer. Examples of employers that had informed their employees about TFC included a pharmaceutical company and a school. One aware non-user had heard TFC being discussed on the radio during a news segment. After hearing it in passing, TFC users had then usually researched further online and, upon finding out they were eligible, decided to apply.

“It was mentioned by friends in a passing comment and when we started paying [for childcare], I was paying full price then I remembered the comment, went online, realised we were eligible and thought it was stupid not to apply.”

TFC User, Male, Dual parent F/T, >£50,000

“Another parent told us. We looked into it but not very much because it seemed a lot of hassle and we were thinking, what’s the catch?”

Aware Non-User, Female, Dual parent P/T, <£30,000

There were different levels of awareness of the precise details of the scheme amongst aware non-users. Some knew very little, having heard it mentioned briefly but not gone on to do further research. Others knew more specific details, like the fact that it was an online account, that the government contributed 20% towards the costs of childcare and that there was a cap on how much money would be contributed. Some confused the TFC offer with other government childcare offers, like the 30 free hours offer available in England.

However, even amongst non-users, there was a degree of understanding of the kinds of childcare that could be paid for using TFC, including unaware non-users assuming that it would be for registered childcare providers. It was not always expected that TFC could pay for holiday clubs, and working parents were generally pleasantly surprised to discover this. Users, because of their closer connection to TFC and paying for different provision with it, had more awareness of the providers that could be paid for using TFC. However, there were cases where users were also unaware TFC could be used to pay for holiday clubs.

Working parents not using TFC generally assumed they were ineligible because they could not claim other government support, for example receiving Child Benefit payments. Parents not using TFC thought they earned too much, or, for some part-time workers, that they did not work enough. For one parent who had previously been a user of TFC, they believed it was only for specific settings and for children under school age, so had stopped using TFC once their child started school.

“I have heard about other government schemes and then you phone them up and don’t meet the criteria, so I assume Tax-Free Childcare is along the same lines.”

Aware Non-User, Male, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, £30,000 to 50,000

As part of the interviews, working parents were told details of TFC and the eligibility criteria. They always realised that they were eligible for TFC and usually indicated a willingness to research further and potentially register. This was the case for both aware and unaware non-users of TFC. They were paying for formal childcare that, in theory, could be paid for using TFC and were open to the potential financial savings TFC presented. Unaware non-users were especially open to the concept as they tended to be unaware they were eligible for any financial help from the government whatsoever.

“If it gives us an opportunity to save money, then I’m interested. 20% is quite a good saving, especially given how much we’re paying per month at the moment. Even to save a bit would be useful.”

Unaware Non-User, Male, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, £30,000 to 50,000

Aware non-users who questioned their eligibility originally were also pleasantly surprised to discover that they met the criteria and to hear about the range of childcare that could be paid for using TFC. In some cases, this led them to argue that they might be able to increase their hours at work as childcare overall would become more affordable. This is linked back to the constant re-evaluation of how worthwhile it is to work discussed in section 3.3, which was common especially for part-time workers. Saving money spent on childcare was the primary reason for working parents thinking about using TFC in future, especially due to the rising cost of living.

“I think I would [use TFC]. I’m going to look into it more and see how it works for us as it might be a better way of paying for childcare.”

Aware Non-User, Female, Dual parent F/T, <£30,000

5.2 Experience of using Tax-Free Childcare

Users, once registered and set up to pay for childcare using TFC, found the online account mostly straightforward and easy to use, although some found registering a long-winded process. Finding providers that could be paid for through TFC was viewed as largely uncomplicated. Parents outlined a small number of things that they found challenging or tedious when dealing with their TFC accounts:

-

the reconfirmation period being every 3 months – some parents forgot and missed out by not reconfirming their eligibility

-

the time taken between depositing money and it appearing in the TFC account – it was felt this should be more instantaneous

-

only having one person able to manage the account – this could lead to unbalanced responsibilities between parents, with this often falling into traditional gender binaries

-

the manual process of updating – this was felt to be tedious during months with an extra week or having to enter the account to pause during holiday periods

-

irritations with the double authentication process – some parents were annoyed with the process

“It’s easy to use, in terms of paying money into it and then paying your provider... If you’re computer literate enough, there’s no issue with it. I’ve had no issues with that system at all.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent F/T, >£50,000

“The online aspect is alright, but I don’t love it. The double authentication is a bit tedious and it can be a little clunky – with half terms you have to stop, go back in and restart.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, <£30,000

5.3 Interaction of Tax-Free Childcare with other government offers

TFC users supplemented their use of the scheme alongside other government offers where they were eligible, for example the 30 free hours scheme in England.

Employers tended to no longer offer childcare vouchers, even in cases where employees had been working there prior to 2018, when that scheme ended.

If working parents in England could make use of the 30 free hours scheme, it lowered the total spent on childcare and enabled parents to amend their working patterns because they had more money to spend on childcare that exceeded the 30 hours total. Overall, 30 hours made a substantial difference to eligible parents in England and was viewed as simple to use.

There were some regional differences between working parents’ experiences due to devolved nations providing different levels of free support. For example, in Northern Ireland, parents received 12.5 hours per week over 38 weeks of government funded care that parents were keen to use as it prepared toddlers for school but were still required to pay for all day care at private nurseries as their children would be picked up by these private providers in the mornings.

Case-study 1: Example illustrating how TFC use can change over time as children get older and parents use other childcare offers

One aware non-user was in a dual parent household, with 2 children aged 6 and 4. She worked part-time and her partner full-time. They previously used TFC for nursery but had stopped when they were unaware it could be used for wraparound care. They were now spending less on childcare, using 30 free hours, but still paid for after school clubs.

“I didn’t feel that I would benefit enough from continuing to use it.”

When the 30 free hours offer became available, TFC became less attractive because they were no longer required to carefully plan money spent on childcare and they lacked understanding of what childcare provision could be paid for using TFC. Reducing their childcare costs over time is a key interest, and by resuming their use of TFC, she could increase her working hours from 3 to 4 days a week because wraparound care would be cheaper. With a greater understanding of what TFC could be used for, her working pattern and overall participation in the labour market could increase.

“I am comfortable with my current work/life balance, but my pocket isn’t.”

6. Labour market participation and Tax-Free Childcare

This chapter explores the relative weight and interaction of the factors that affected working parents’ labour market participation and the influence of TFC. Work flexibility, and use of informal childcare, and other government childcare offers, helped to support the labour market participation of working parents to a greater extent than TFC. However, TFC was valued by users, interacted with these other factors, and enabled them to maintain their preferred working patterns.

6.1 The labour market participation of working parents

The labour market participation of working parents was affected by several factors, some of which supported parents to work while others made labour market participation more challenging. The weight and emphasis placed on each factor and the interplay between personal, work, and childcare factors meant labour market participation varied between families.

The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation, Behaviour (COM-B) model (Michie 2011) was used as a lens to interpret the qualitative data to understand the varied and competing opportunities and constraints on parents’ labour market participation and the role of TFC. The application of this model is appropriate because data showed that parents do not act in an economically rational manner when determining their labour market participation. The decision to work, and how much, is in part financial, but also shaped by personal, workplace, and labour market factors (BITC, 2022).

In the COM-B model:

Capability is defined as an individual’s psychological and physical capacity to engage in the activity concerned, which includes having the necessary knowledge and skills. In relation to TFC this includes awareness and understanding of TFC and the eligibility criteria, and skills and confidence in making an online application.

Opportunity is defined as the factors that lie outside the individual that make the behaviour possible or prompt it. These are both social and physical. Relevant factors here include the affordability of formal childcare and the ability to pay for the type of preferred childcare using TFC. Labour market factors, such as the characteristics of parents’ employment, and the location and hours of work, are also elements of opportunity.

Motivation is defined as the brain processes that energise and direct behaviour and includes automatic as well as reflective and reasoned responses. For working parents, this includes their own sense of self as a care giver, the emphasis and importance they place on career goals and work identity. Factors such as earnings and lifestyle aspirations also motivate labour market participation. In relation to TFC, the experience and ease of use of the scheme are relevant.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the factors that influenced working parents’ labour market participation using the COM-B model. It shows the interconnectedness of the various factors, and complexity and degree of personalisation of parental labour market participation.

Factors that affect parental labour market participation

| Factors increasing participation | Factors decreasing participation | |

|---|---|---|

| Capability |

Aware of available support with childcare costs High level of digital skill and confident to find and apply for support online |

Not aware of available support with childcare costs Poor digital skills and not confident to apply online |

| Opportunity |

Cost of childcare low proportion of household income Good availability of suitable childcare Childcare used can be paid for with TFC Flexibility of working hours or location |

Cost of childcare high proportion of household income Limited childcare availability Childcare used cannot be paid for using TFC Lack of flexibility in working hours or location |

| Motivation |

Strong work/career identity Preference for formal childcare |

Sense of self as primary caregiver Preference for parental childcare |

| Preferred work-life balance | ||

| Household context |

Dual parent Informal childcare available |

Single parent Lack of informal childcare available |

| Age of children; number of children |

6.2 Household characteristics

Household context and characteristics affected parents’ labour market participation. These factors enabled work where they created opportunities to balance work and childcare in the way preferred by working parents.

The age of children in the household and number of children affected the household’s childcare costs and influenced the type and number of childcare settings working parents used. Families with younger children frequently had the highest childcare costs, and depending on the age of their children, families with more than one child had children in different childcare settings.

6.3 Access to informal childcare and support networks

Working parents were commonly supported to work by informal childcare. Living close to family who were willing and able to provide regular informal childcare supported parents to work. Where families were able to draw on informal childcare, this helped them to reduce childcare costs, maintain family presence with children through wider family connections, and enabled parents’ labour market participation.

Relying on informal childcare regularly left working parents with a sense of indebtedness and guilt, particularly in instances where grandparents had health issues. There were cases where grandparents travelled to stay overnight with families on a weekly basis, and working parents worried that they were asking too much.

If formal childcare was more affordable, there were instances where working parents felt they would redesign the balance between their use of informal and formal childcare, with more use of formal childcare. The current design of TFC was not a sufficient financial contribution to childcare costs for arrangements to be redesigned. Where informal childcare use could be decreased, working parents said it would serve to reduce the guilt of relying on family members regularly for childcare. In some cases, parents expressed that a reduction in regular informal childcare would make them feel better able to ask ad-hoc for support with childcare.

"There are opportunities for progression within my role, but at the moment I had said I'm not going to go for it. The reason being that it is very busy, and we are using the grandparents. If there was more money and I could put the kids in childcare, then I could ask the grandparents for extra support and that might give the breathing space to go for a higher-level job.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, <£30,000

6.4 The cost of formal childcare and influence of TFC

The reported hourly costs between childcare settings tended to be similar. The total formal childcare cost faced by working parents therefore depended largely on their child’s age, and whether they were eligible for other government childcare offers or could attend school, rather than differing hourly charges between settings. Cost was therefore not the main factor in the choice of formal childcare setting (see section 3.3) but had a role in parental decisions about how much and when to work.

The cost of formal childcare each month differed significantly between participants. Formal childcare costs varied from around £80 each month to over £1,000 a month among the families interviewed, representing very different proportions of household income. Therefore, the financial value of TFC to eligible families varied from around £16 to around £200 per month for one family with 2 young children.

All eligible working parents can set-up and pay for childcare costs using a TFC account, irrespective of the age of their youngest child. Parents of school age children had varying childcare costs month to month, with school holidays presenting additional costs, and the summer holidays mentioned as particularly challenging.

TFC had the most financial impact where childcare costs were a large part of the household budget, and for families with lower earnings. Families with young children who had returned to work after parental leave, but who did not yet qualify for the early years’ entitlement, had the highest childcare costs and gained significant financial value from TFC. Families with several children could also have high childcare costs, depending on their working hours.

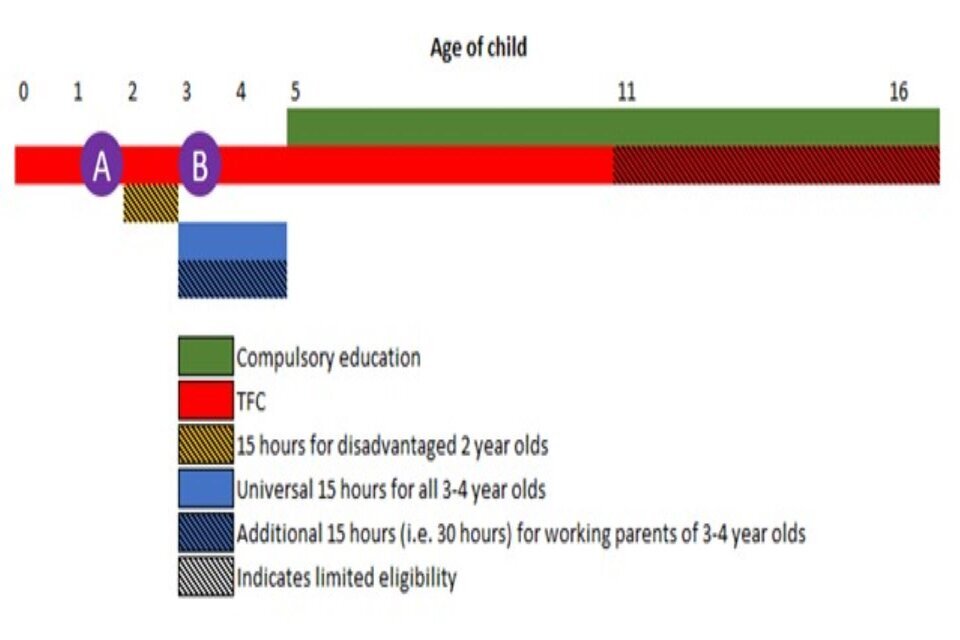

Figure 1.2 illustrates the gap between the end of eligibility for parental leave after having a child (point A), and the introduction of free childcare hours for moderate to high income families in the next school term after their child turns 3 (point B). It was during this period that users felt TFC made a substantive difference to their ability to work, as childcare costs were especially high.

Other government childcare offers, like 30 free hours in England, were deemed to be more influential than TFC as children grew older because they made a larger financial contribution to childcare costs. Once of school-age, children attending formal education are looked after for a minimum of 32.5 hours a week during school term time.

Figure 1.2 Age of child and eligibility for financial childcare support

Figure 1.2 shows how childcare eligibility changes with the age of a child, highlighting the interaction of TFC, 15 hours free childcare and 30 hours free childcare. At the time of the research the only support available to children aged 0 to 2 was TFC, with children from a disadvantaged background becoming eligible for 15 hours free childcare at 2 years old. At 3 years old 15 hours free childcare becomes universally available for all 3 to 4 year olds, with an additional 15 hours (making the offer 30 hours free childcare) available for working parents. At age 5 most children enter full-time education. TFC is available to working parents alongside all of these offers from 0 to 11, or up to age 16 for disabled children.

Age of child and eligibility for financial childcare support

There were examples where TFC reduced the overall household spend on childcare to such an extent that it made it financially worthwhile for both parents to work 5 days a week. Parents spending a lot of money on childcare were grateful for the financial help TFC provided, as illustrated in the examples below, and case-study 2.

In one family, both parents worked full-time and were higher rate taxpayers. They used a nursery and wraparound care for their children aged 3 and 7 years. The family spent around £500 a month on childcare.

“Without the tax-free account, I really don't know how we would manage. With the amount of money [we spend on childcare], having that 20% is really great.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent F/T, >£50,000

In another case, in a family that used TFC, both parents worked full-time, one as a solicitor and the other as a journalist. They had a 3-year-old and a child about to turn one. They spent around a third of their monthly household income on childcare:

“It makes a massive difference. Without it, we’d be stranded and unable to work. Money’s tight anyway but it’s essential for us to be able to afford childcare.”

TFC User, Male, Dual parent F/T, >£50,000

Another family using TFC had 3 children. Both parents worked full-time. The youngest child was less than 3 years old and therefore not eligible for any other government childcare offers. The family spent around a quarter of their monthly income on childcare and were supported by 2 sets of grandparents living locally. They were enabled to balance work and family through hybrid working, and the participant reflected on the role that TFC had played in enabling her to maintain her career:

“TFC enables me to work. I know some people who go to work and end up with £50 at the end of the month, but I don't want to come out of employment and break the career cycle… we are both in careers where if we had to take time out due to childcare, then we wouldn't be able to get back into work at the levels we are. TFC really benefits us, and is helping us to maintain that.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent F/T, £30,000 to 50,000

Case-study 2: Example where TFC in combination with work flexibility enables labour market participation

One TFC user was in a dual parent household, with one child aged 18 months. They earned between £50,271 and £99,000 per year. They found out about TFC through their childminder who was registered for payment through it. TFC made a difference to the family budget, and they saved around £150 per month on childcare costs.

“It does make a difference every month. It's like £100 to £150 difference for us. That's nearly 3 weeks’ food shopping for instance."

If childcare was unaffordable, one of the parents would be required to change their working hours and patterns to manage. Without TFC, they felt that childcare would be less affordable, and the costs of childcare would have a negative impact on their participation in the labour market. Their working hours provided significant flexibility to enable them to balance working with family life, and their preferred balance of time spent with their children.

“I have always worked atypical hours (7am to 3pm) as I want to be present at home, but childcare impacts the hours my partner works as he does shifts to fit around childcare arrangements."

Working parents that were eligible for TFC and had children too young to be entitled to free hours, tended to view the period of high childcare costs as temporary. TFC played a role for users in reducing overall costs during this time when children were not yet eligible for free hours. They felt that childcare costs would reduce in time as children grew older and they received funded hours or their child started school.

“Half of my take home salary pays for our childcare at the same time we are looking at it as a short-term thing. Once they are both in school the costs will go down.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent F/T, £30,000 to 50,000

Among users of TFC with older children, and those that spent less of their household incomes on formal childcare each month, TFC was often viewed as “nice to have”. For these users, it neither determined their work patterns, nor made a significant financial difference. Their labour market participation was more strongly influenced by other factors, such as a sense of career, the value placed on working outside the household, and the availability of informal childcare to the family. Families that did not spend much on formal childcare viewed TFC as a useful financial contribution, but not essential to their childcare affordability.

“The financial side isn’t the hook of it really.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, <£30,000

“The saving isn’t much, but the costs are low anyway. It’s still nice to have that contribution.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent F/T, >£50,000

Nevertheless, TFC helped to reduce formal childcare costs and all users were grateful for the financial contribution it made. Regardless of their financial circumstances, TFC signalled to working parents that there was some support from government to help them to work.

“We're just lucky they offer it. They don't have to offer it. It's an incentive for people to work.”

TFC User, Male, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, >£50,000

6.5 Suggestions to increase the influence of TFC

While TFC users were generally positive about the scheme because it reduced the costs of working, TFC in and of itself was not sufficient to drive their labour market participation. Participants were asked what might increase the influence of TFC to their family and labour market participation.

6.6 Increase or means-test the value of the government contribution

Several participants discussed that a higher value of the government offer would encourage greater use of TFC, increasing it above the current rate of 20%, and lifting the £2,000 per annum cap. Increasing the value of the government contribution in line with the higher rate of tax was noted as a way to increase the influence of TFC by high income users, as was raising the current eligibility cap on parents earning above £100,000 to reflect recent increases in the cost of childcare.

Participants wondered whether the value of TFC was equal in regions with higher childcare costs, such as London. They generally felt that the relief would cover less of the childcare costs for families in such areas. TFC users felt that the level of government contribution could be differentiated, or means tested, to reflect differences in the proportion of income spent on childcare between families, in recognition of the fact that the financial incentives to work differ depending on a parents’ job role and salary. They suggested that the government contribution could be increased, for example where childcare costs were a larger proportion of household income.

“More means tested to make it in everybody's best interest for you to go back to work... I do think that there is a lot of women who are within those brackets where you're like, well, by the time I pay for childcare, I'm losing money, or I'm not making anything at all.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent one F/T one P/T, <£30,000

6.7 Using TFC for interest-led settings

Parents with school age children needed to arrange and finance childcare arrangements for school holidays. As children got older, parents also reflected the increased importance that the child’s preferences and interests were accommodated in childcare settings. Working parents with school aged children were keen to use interest-based settings, such as sports, arts, and drama clubs, and to be able to pay for a greater variety of these using TFC. More generic settings (for example, after school clubs) could lack interest for children, meaning they were reluctant to attend. Parents felt interest-led activities increased their child’s motivation to attend, especially in school holidays. During holiday times, the child’s preference, availability, and affordability were important.

Awareness that TFC could be used for settings registered with a regulator, such as Ofsted in England, delivering such interest-led activities was quite low. Additionally, parents noted that many organisations delivering these activities, especially in the school holidays, were not registered. Enabling working parents to use TFC to pay for a wider range of childcare settings would give them more choice to determine how they balance work and family life during school holidays. Some participants currently managed by taking unpaid time off work. TFC was seen as helping parents that wanted to maintain their working hours during school holidays.

“It would be nice if you could use it towards sporting activities and things like that because they are all really important for a child's development. They might not be accessible to everyone because of the cost, so TFC against those would be a good thing.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent F/T, >£50,000

“That [being able to use TFC for sports and arts clubs] would make a difference as I would know he was somewhere doing something he likes. Keeping him engaged and motivated is all we want to do.”

Aware Non-User, Female, Single parent F/T, <£30,000

“Financial impact [of childcare costs] is off-putting. You're struggling to pay your childcare bills, and then in turn you need to work more, but then the more you work the more you have to pay out in childcare costs.”

Unaware Non-User, Female, Single parent P/T, <£30,000

6.8 Increase awareness of TFC

Participants suggested that increasing the awareness and understanding among eligible parents of TFC could increase take up of the scheme. Families frequently reconfigured their work and childcare arrangements at transition points. These represented times when parents were receptive to hearing about TFC, and when it would inform their decisions.

The first time that parents felt working hours and childcare had a focus was when they returned to work after having a child. The interactions with government services for new parents through maternity and health services, birth registration, and applying for Child Benefit already feature TFC, they suggested this was the point at which information had the maximum opportunity to reach this audience group.

The addition of more children and associated periods of parental leave were also times of transition when work and childcare arrangements were in flux.

The age of children and their eligibility for the government childcare offer and entry to formal education also represented times of transition. The early years entitlement and the start of school were times when family finances and daily lives were in focus. A change in setting provides the opportunity to inform working parents about TFC. When children started school, parents frequently started to use different settings, such as wraparound care in the form of breakfast and after school clubs, or childminders.

Other times families reconfigured work and childcare arrangements, included changes due to relationship breakdowns, with parents deciding custody arrangements.

6.9 Constraints to labour market participation

In cases where the demands of a parent’s work could not be accommodated by a combination of their personal and family circumstances, the availability of the childcare offer, or affordability of childcare, working parents changed their job role or reduced their working hours. For instance, one parent had stopped work as an actor which had involved contract work and irregular hours, to work in a school. This role provided more predictability in working hours but had a lower salary. Another parent had changed from working as a vet to teaching veterinary science. Again, the new role had more predictable hours, and did not require them to be ‘on call’.

Several parents had reduced their working hours since having children. Reasons included preferences about how much time to spend working and with family, and the costs and affordability of childcare. This was especially when children were young, and in cases where families did not have regular informal childcare provided by friends and family nearby. In one family a parent had recently changed job roles to reduce their working hours, as well as move away from shift work. They made this change so they could spend more time with their daughter, and more regular working hours better fitted with childcare availability. While the parent had reduced earnings, they reflected:

“It’s what’s best for my family at the moment.”

TFC User, Female, Dual parent F/T, £30,000 to 50,000

Working parents also prioritised time as a family. For instance, one dual parent family had managed childcare and work by staggering working hours. While this had minimised childcare costs, one parent in this family had recently reduced their working hours. Staggering work and childcare had meant they did not have much family time, or time as a couple, which they reflected had started to strain their relationship.

“I just didn't want my children to have an experience where they were feeling passed from pillar to post, and mum and dad are always exhausted, and not able to give them time to do things like homework and sit together and do things together. I wanted them to have mum about, but also I want them also to see that mums work. Yeah, it's good to work. It's good to have career aspirations and want to do something different than be at home all the time.”

Unaware Non-User, Male, Dual parent F/T, £30,000 to 50,000

Once finding a work and childcare arrangement that worked for the family, working parents tended to focus on creating stability as far as possible. Changes in working patterns discussed by participants were likely to be to help them manage work and family life. Changes in working hours or job could also be instigated by changes in childcare arrangements, for example due to the age of children. Parents wanting to increase their working hours or to progress in their careers sometimes discussed waiting until their family life would better accommodate extra responsibility.

7. Conclusions

Parents sought to minimise formal childcare costs. The household context, work flexibility, and informal childcare were effective ways to gain the maximum financial reward from working and reduce formal childcare costs. These factors were typically considered before considering use of TFC because they could reduce the use of formal childcare and associated costs to a greater extent.

Among users, TFC reduced formal childcare costs. TFC users found it helped them maintain their preferred working hours, and decreased formal childcare costs, especially where they were not eligible for other government offers.

The relative financial influence of TFC on users’ labour market participation depended on the proportion of household income spent on childcare, the total household earnings, the age of the youngest child and eligibility for other childcare offers, and the number of children in the household.

TFC continues to financially support working parents with childcare costs and financially support them to work their preferred hours.

This research aimed to assess the extent to which TFC influences the work and childcare choices of working parents, to provide an understanding of the links between TFC and labour market participation, and to assess TFC’s impact in supporting parents to continue working or work more hours.

The factors affecting parents’ labour market participation were complex, and dynamic. Some factors increased, and others decreased participation in work. Parents sought to minimise formal childcare costs. The household context, work flexibility, and informal childcare were effective ways to gain the maximum financial reward from working and reduce formal childcare costs. These factors were typically considered before contemplating use of TFC because they could reduce the use of formal childcare and associated costs to a greater extent.