Public trust in charities 2023

Published 14 July 2023

Applies to England and Wales

Research conducted on behalf of the Charity Commission by Yonder - April 2023

Summary

With the Covid pandemic barely in the rear-view mirror, the cost of living crisis is affecting all corners of society but especially those whose lives were less secure to begin with.

Many charities have tried to help ease these burdens, and this appears to have been recognised particularly by those who have benefitted from their support. But that work, as important as it is, has not fundamentally changed people’s overall trust and confidence in charities or how relevant they believe them in general to be.

There is stability in the public perception of charities who are more trusted than they were half a decade ago and more trusted than most other institutions and sectors in public life. This is progress compared with loss of confidence in charities in the years after 2015 but there are few, if any, signs of trust returning to those pre-2015 levels.

Instead the sector seems to have settled, with most people supporting and wanting charities to succeed but the legacy of high profile cases involving the governance of large household name charities continues to act as a drag on people’s instinctive willingness to believe that charities can be fully trusted to manage funds and create genuine impact.

In the current climate, demonstrating prudent stewardship of funds is therefore more critical than ever. For the public, this means avoiding unnecessary risks but also making sure that donors’ money is actively put to work to further the charity’s purpose.

Because of the way people think about charities, some organisations have to work harder than others to demonstrate that they are doing this effectively and that they are driven by the right intentions.

The public – particularly the less secure part of the population – are much less inclined to trust larger, international, and professionalised charities than smaller, local, volunteer-run concerns. This is through no fault of the former but because the latter are often easier to identify with and can demonstrate a more straightforward link between donations and impact. A charity whose work is more readily understood and supported is also one which is more likely to be trusted.

This has always been the case but there is a risk that this divergence of opinion about different charities could grow. In a society which is polarised by so much else, charities across the board need to work hard to ensure they are not added to the list.

What is the public opinion landscape for charities amid rising living costs?

We are in an era of charity trust in which the value of charity is still recognised but where doubts persist.

There is a divide in attitudes towards charities and there is potential for that divide to widen. Trust in charities has marginally increased at a time when trust in other institutions has flatlined or fallen

Changes are minimal, but charities continue to do well relative to other social institutions

Mean trust and confidence by sector/group (/10), with change vs 2022

| Sector | Mean trust of confidence | Change since 2022 |

|---|---|---|

| Doctors | 7.1 | -0.1 |

| Charities | 6.3 | +0.1 |

| Banks | 5.6 | +/-0 |

| Police | 5.5 | -0.3 |

| The ordinary man/ woman in the street | 5.5 | +/-0 |

| Social services | 5.3 | +/-0 |

| Private companies | 5.0 | +/-0 |

| Your local council | 4.9 | +/-0 |

| Newspapers | 4.0 | +0.1 |

| MPs | 3.3 | -0.1 |

| Government ministers | 3.2 | +/-0 |

Quotes from research

“I don’t think it’s really changed over the last year. I’ve always had a great deal of respect for the ones that I used to and still do patronise.”

“Occasionally you do get quite bad headlines about things; but at the moment I couldn’t name a charity that I don’t trust, put it that way.”

“I think over the last year it’s been pretty much as it was. I’ve not read or seen anything that’s made me consider them less.”

Change over time: trust in charities vs other sectors

Trust in charities has somewhat recovered since 2018, while many comparable sectors have noticed downward trends

Mean trust, by sector

| Sector | 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doctors | 7.6 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 7.1 |

| Charities | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 6.3 |

| Police | 7.0 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 5.8 | 5.5 |

| Banks | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 5.6 |

| The ordinary man/woman in the street | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 5.9 | 5.5 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Social Services | 5.9 | 5.9 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Private companies | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Your local council | 5.0 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 4.9 |

| Newspapers | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 4.0 |

| MPs | 4.1 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Government ministers | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 |

Question not asked in 2005

Trust levels still sit lower than historical highs

Stable trust level

Following a turbulent period for public trust during the pandemic, the past year has seen very little movement for all institutions other than the police.

Public trust in charities has risen though the increase is minimal. This marks the third year in a row of steady public trust in charities, suggesting that the recovery from the 2015-2020 trust crisis may have reached a plateau that remains below historic highs.

It is clear from interviews with members of the public from across the Clockface (i.e. drawn from different parts of the population) that, as a result of high-profile scandals from as early as 2015, the sector is not automatically given the benefit of the doubt, even if the work of local charities during the cost of living crisis may have bolstered some people’s existing belief in the value and impact that charities can bring.

In short, we may be in a new era when it comes to trust in charity in both England and Wales: one in which stubborn doubts remain even though the value of charity is widely recognised.

Mean trust and confidence in charities (/10)

| Year | General public mean trust in charities | Top left mean trust in charities (high security, high diversity) | Bottom right mean trust in charities (low security, low diversity) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 6.3 | 0 | 0 |

| 2008 | 6.6 | 0 | 0 |

| 2010 | 6.6 | 0 | 0 |

| 2012 | 6.7 | 0 | 0 |

| 2014 | 6.7 | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 |

| 2018 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 |

| 2020 | 6.2 | 6.7 | 5.6 |

| 2021 | 6.4 | 7.0 | 5.9 |

| 2022 | 6.2 | 6.8 | 5.5 |

| 2023 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 5.6 |

From 2018 onwards, the survey was conducted online rather than via telephone. This question, however, was also asked on a concurrent telephone survey as a comparison in 2018, giving a mean score of 5.7/10 (a difference of +0.2)

Trust levels have marginally increased in all parts of society, though the trust gap remains prevalent

The top left are currently a charity trust stronghold. Trust in charities is strongest in high security, high diversity parts of the public. For those on the bottom right, there is an increasing vulnerability in charity trust. Trust in charities is weakest in low security parts of the public, though it has improved at a similar rate across the Clockface.

Percentage (%) who trust charities (with a score of 7-10 on a 0-10 scale)

| General public mean trust in charities | Top left mean trust in charities | Top right mean trust in charities | Bottom right mean trust in charities | Bottom left mean trust in charities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 54% (+3%) | 70% (+4%) | 57% (+3%) | 41% (+4%) | 51% (+5%) |

The trust gap applies to other sectors too

The top left is a trust stronghold. Those in the top half (more economically secure) are more likely to trust sectors in general.

For those on the bottom right, there is an increasing vulnerability in trust. Those in the bottom half are less trusting of sectors / institutions in general.

Percentage (%) who trust at least half of the sectors / institutions we tested (with a score of 7-10 on a 0-10 scale)

| General public mean trust in charities | Top left mean trust in charities | Top right mean trust in charities | Bottom right mean trust in charities | Bottom left mean trust in charities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25% (+1%) | 27% (-1%) | 37% (+3%) | 18% (+/-0%) | 12% (+2%) |

The overall perceived importance of charities is steady, but there is less consensus across the Clockface

Growing divergence of opinion

The overall perceived importance of charities is also steady, remaining at a low point. This is despite the heightened visibility of charities during the cost of living crisis. Taken together, the quantitative and qualitative data suggest something of a divide.

Those who are already inclined to trust charities (often found in the ‘top left’ part of the Clockface model) are more prone to recognise the important work that charities are doing in supporting those in need during the cost of living crisis. They refer to food banks and kitchens, often in their local areas.

Those who are less inclined to trust charities stop short of describing them as essential due to existing doubts (either consciously or subconsciously) about stewardship of funds. Though they, too, note the increased visibility of charities following the cost of living crisis, they tend to credit this to smaller-scale charity work in local communities, which they view as distinct from the work of larger, international charities. These larger charities play a large role in shaping views of the sector overall but are sometimes considered more opaque.

Percentage (%) who describe charities as ‘essential’ or ‘very important’

| Year | General public | Top left (high security, high diversity) | Bottom right (low security, low diversity) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 72% | 0 | 0 |

| 2010 | 67% | 0 | 0 |

| 2012 | 76% | 0 | 0 |

| 2014 | 75% | 0 | 0 |

| 2016 | 69% | 0 | 0 |

| 2018 | 58% | 0 | 0 |

| 2020 | 55% | 68% | 44% |

| 2021 | 60% | 74% | 50% |

| 2022 | 56% | 70% | 43% |

| 2023 | 56% | 73% | 40% |

From 2018 onwards, the survey was conducted online rather than via telephone. This question, however, was also asked on a concurrent telephone survey as a comparison in 2018, giving a percentage of 62% (a difference of 4%, and confirming the significant decrease)

Drivers of trust in the cost-of-living crisis

Demonstrating effective stewardship of funds remains critical.

The public favour caution in managing charitable funds but only if it is clear that the money is actively being put to work to deliver the charitable purpose.

For many charities, the cost of living crisis is providing an opportunity to demonstrate this.

Public expectations of charities include four key factors

| Where the money goes | Impact | The ‘how’ | Collective responsibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| That a high proportion of charities’ money is used for charitable activity | That charities are making the impact they promise to make | That the way they go about making that impact is consistent with the spirit of ‘charity’ | That all charities uphold the reputation of charity in adhering to these |

These expectations are drawn from quantitative and qualitative data from across the research programme over recent years.

How charities are perceived to perform against these expectations determines how much the public trust them.

There has been little change overall in the proportion of people who think charities are achieving impact or delivering a high proportion of money to those they are trying to help

To what extent do you think that charities you know about are… [% who say ‘very much so’ or ‘to some extent’]

| Charities are… | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Making an impact | 72% | 73% | 72% | 73% |

| Well-run | 62% | 64% | 61% | 63% |

| Operating to high ethical standards | 61% | 64% | 59% | 61% |

| Delivering a high proportion of the money they raise to those they are trying to help | 57% | 59% | 56% | 59% |

| Treating employees well | 51% | 52% | 49% | 51% |

While the public’s primary concern continues to surround donations reaching the intended beneficiaries, this concern has lessened in the least secure areas over the past year

Percentage (%) who doubt that donors’ money reaches intended beneficiaries

| All | Top left | Top right | Bottom right | Bottom left |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21% (-4%) | 13% (-3%) | 19% (-3%) | 28% (-6%) | 23% (-5%) |

Q. To what extent do you think that charities you know about are delivering a high proportion of the money they raise to those they are trying to help? [Showing percentages for ‘only a little’ + ‘not at all’]

There is greatest doubt in the less secure parts of the population.

Greater visibility of charities during the cost of living crisis may have helped to dissipate doubt

“Especially in a cost-of-living crisis, I think we can all agree [charities are] very useful, especially food banks at this point.”

“We’ve got [a food bank] locally here, and the food keeps coming in, and people are getting more hungry now because of the crisis that’s happening.”

The public think trustees should minimise risk and focus on core purpose when spending charity funds

|

Cautious spending “Trustees should be cautious with charity funds even if that may limit the help they can give to those in need” |

On the fence |

Risk taking “Trustees should take risks to increase the help available to those in need even if that puts some charitable funds at risk as a result |

| 55% (79% of trustees) | 26% | 18% (9% of trustees) |

|

Spending on core purpose only “Trustees should be careful to spend charity funds only on a charity’s core purpose” |

On the fence |

Spending based on trustees’ judgement “Trustees need to be allowed to use their judgement as to how best to spend charity funds” |

| 62% (72% of trustees) | 18% | 20% (19% of trustees) |

Participants were presented with both statements and asked to say where their view lay, where 0 would mean total agreement with statement A and 10 would mean total agreement with statement B. Here, we show the percentages who tend towards each quoted statement (scores of 0-4, or 6-10), and those ‘on the fence’ (5). Statement orders were rotated. *Minor wording difference between public and trustee surveys.

Spending should not be so cautious that the end cause is unduly limited, but risks should be minimised

There is a clear preference for trustees to be cautious when spending charity funds. This is the case in both England and Wales, and is particularly true in the current context, with interviewees noting the impact of the cost of living crisis and need for prudence to ensure financial stability.

Though help to those in need may be limited as a result, safeguarding the future of the charity to ensure long-term support is deemed most important.

However, in line with the desire for money to reach the end cause, excessive caution is equally frowned upon – the public want donations to be put to good effect and not sitting in a bank account. Charities therefore have public permission to use a sensible balance of the two approaches, where funds are used to maximise aid without taking excessive risks.

There is also an acceptance that risk-taking can be beneficial in some circumstances. While the public tend to prefer caution, many do not take issue with riskier spending as long as charities advertise transparently how and why the funds will be used.

“Just sitting on a pot of money isn’t good, […but] they need to be slightly risk adverse as opposed to high risk.”

“I think charities do need to be cautious because the longer they survive, the more good they can do. If they have a clear amount or percentage that they can donate safely, they should, so I would say my answer to that would be they should be safer than sorry.”

“It’s probably a better idea just to try and do what they can with the resource that they have, as opposed to be going a bit wild. Not wild, but taking new risks.”

The public tend to agree that charities should be able to campaign for social change, though many disagree

|

Respond to social debates “Charities should respond to social and cultural debates if they want to stay relevant and keep the support of people like me” |

On the fence |

Don’t get involved “Charities should not get involved in social and cultural debates if they want to keep the support of people like me” |

| 41% (55% of trustees) | 29% | 30% (21% of trustees) |

|

Push for change if it helps meet needs “There’s nothing wrong with charities campaigning for change in society if it helps them meet the needs of those who rely on them” |

On the fence |

Focus on needs only, not pushing for change “Charities should focus on meeting the needs of those who rely on them, rather than campaigning for change in society” |

| 50% (55% of trustees) | 19% | 31% (30% of trustees) |

Participants were presented with both statements and asked to say where their view lay, where 0 would mean total agreement with statement A and 10 would mean total agreement with statement B. Here, we show the percentages who tend towards each quoted statement (scores of 0-4, or 6-10), and those ‘on the fence’ (5). Statement orders were rotated. *Minor wording difference between public and trustee surveys.

How do charity characteristics influence trust?

Volunteer-run, smaller charities have an easier time inspiring trust than larger, professionalised, international charities. This is particularly the case in low security, low diversity zones.

Larger charities have to work harder to demonstrate authentic connection to and impact on the causes they support.

The public are more inclined to trust smaller, local charities that appear to have significant volunteer involvement

| Statement A | Mean scores | Statement B |

|---|---|---|

| A charity that serves a cause I care about | 3.83 | A charity that serves a good cause that I am not particularly interested in |

| A charity that is focused in my local area | 4.54 | A charity that does work across the country |

| A large charity | 5.58 | A small charity |

| A charity that is run by paid professionals | 6.05 | A charity that is run by volunteers |

Q. Please read the following pairs of statements. In each case, please use the sliding scale to indicate which you would be most inclined to trust, using a 0-10 scale on which 0 means you fully trust A rather B, and 10 means you fully trust B rather A.

Smaller, volunteer-run charities and the ‘closeness’ of the cause are particularly important drivers of trust

Q. Please read the following pairs of statements. In each case, please use the sliding scale to indicate which you would be most inclined to trust, using a 0-10 scale on which 0 means you fully trust A rather B, and 10 means you fully trust B rather A.

| Statement A | 0-2 | 3-4 | 5 | 6-7 | 8-10 | Statement B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A charity that serves a cause I care about | 29% | 24% | 33% | 8% | 6% | A charity that serves a good cause that I am not particularly interested in |

| A charity that is focused in my local area | 19% | 21% | 36% | 13% | 10% | A charity that does work across the country |

| A large charity | 9% | 12% | 36% | 23% | 20% | A small charity |

| A charity that is run by paid professionals | 7% | 13% | 28% | 22% | 29% | A charity that is run by volunteers |

Trust for these types of charities derives primarily from a sense that more money reaches the end cause

Visible impact and transparency

The public tend to trust small, local charities run by volunteers more than large, national charities run by paid professionals because they are more confident that money reaches the intended beneficiaries.

For the public, the ultimate proof-point of this is seeing a charity’s work and impact in their own local community, while the knowledge that money is not being spent on salaries provides peace of mind that intentions are truly altruistic.

Conversely, larger charities that operate nationally are often considered to be less transparent and individual donations are seen to have less impact.

The public do still acknowledge the benefits of national charities - including name recognition, influence and reach, among others - and often support them nonetheless, but they are inherently less prone to trust them.

“I’m not sure about how much I trust [big, national charities]. I think seeing it run and worked by local people, it’s just more touching, more hitting, more of a realisation whereas, if it’s a bigger charity, a national charity, it’s more, I don’t know, people in an office allocating money to areas or resources to areas.”

“I think one of the factors is that in the small charities, especially when they’re run by volunteers, all the money goes to the cause. There’s not money being taken for people running it. It’s a lot of voluntary stuff. So in a sense, I feel that gets directly to the beneficiary.”

“I think there needs to be a real open and honest way of looking into what a charity does because some of them are so massive. They’re dealing with such a massive amount of money when they’re that size. It’s so easy for things to disappear.”

A charity’s cause also impacts perceived trustworthiness, but trust is often conflated with likelihood to support

Personal connection is important

A charity’s cause plays a significant role in trust: just 14% of the public are inclined to trust a charity that serves a good case that they are not particularly interested in more than a charity that serves a cause they care about.

However, interviewees explained that this is usually interpreted in tandem with other factors, including size, scope and organisational setup. People impute that charities run by volunteers have a closer connection to the cause of the charity, which in turn suggests genuine interest in the charity’s objectives, which in turn inspires trust. It is easier for certain charities – like those for military veterans – to benefit from these implicit assumptions.

“Smaller charities are set up by someone who’s had an experience. I’m thinking of one that they lost their daughter, so they donate to neonatal units. They’re doing it from this good place, this thing that they’ve experienced, and they want to help other people. Whereas some of the big charities, as I said, can feel like businesses.”

“I think that connection would be there if you’ve been affected and you’re trying to help other people who are currently being affected. Then, for me, I would think that connection would be a lot more solid.”

“No, I don’t think I’ve ever considered that some charities are more trustworthy because of the cause. Maybe some of the causes I would rank higher in importance level, but not as a trust level.”

The tendency to trust volunteer-run charities over professional ones is most prevalent in low security areas

Percentage (%) who trust charities run by volunteers much more than those run by paid professionals (with a score of 7-10 on a 0-10 scale, where 0 is fully trust a charity that is run by paid professionals and 10 is fully trust a charity that is run by volunteers)

| All | Top left | Top right | Bottom right | Bottom left |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 44% | 40% | 38% | 52% | 47% |

This preference is felt across the Clockface, but to a stronger degree in low security parts of the public

Likewise, trust for smaller charities over larger charities is most pronounced in the 3-6 o’clock zone

Percentage (%) who trust smaller charities much more than larger charities (with a score of 7-10 on a 0-10 scale, where 0 is fully trust larger charities and 10 is fully trust smaller charities)

| All | Top left | Top right | Bottom right | Bottom left |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32% | 30% | 30% | 38% | 32% |

This preference is felt across the Clockface, but to a stronger degree in the 3-6 o’clock zone

The importance of local impact is more significant in the 3-6 o’clock zone

Percentage (%) who trust local charities much more than those that operate nationally (with a score of 0-3 on a 0-10 scale, where 0 is fully trust a charity focused in my local area and 10 is fully trust a charity that does work across the country)

| All | Top left | Top right | Bottom right | Bottom left |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 32% | 27% | 32% | 37% | 30% |

This preference is felt across the Clockface, but to a stronger degree in the 3-6 o’clock zone

How the regulator can help uphold public trust and help the sector thrive

The public support the idea of a regulator that balances identifying wrongdoing with providing guidance.

They think it should show tolerance when honest mistakes are made, particularly for smaller, volunteer-run charities.

Almost half of the public say that they have heard of the Charity Commission

Limited real knowledge

Our quantitative and qualitative research shows that the public continue to have little real knowledge or understanding of the Charity Commission.

In the past year, there has been small drop in both awareness of and familiarity with the Charity Commission, continuing the trend observed in 2022 of falling recognition.

Most do tend to assume that the Charity Commission is the ‘watchdog’ for charities, though that is often after having considered the matter due to their involvement in this research and there is seldom a deep understanding of the Commission’s work or role in regulating charities.

Within this context, discussions tended to focus more so on what a regulator should look like rather than how the Commission is currently viewed.

| Awareness of the Commission | % of the public who have heard of the Charity Commission | % of the public who say they know it very or fairly well |

|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 52% | 13% |

| 2020 | 53% | 19% |

| 2021 | 54% | 19% |

| 2022 | 50% | 18% |

| 2023 | 48% | 17% |

The public tend to think the Commission should focus equally on supporting charities and identifying wrongdoing

A balancing act

The public tend to think the Commission’s focus should be split between dealing with wrongdoing and supporting charities. This is consistent across both England and Wales, as well as the Clockface, although those in the bottom right (3-6 o’clock) tend to skew more towards prioritising the identifying of wrongdoing (32%).

They also hope tolerance is shown when dealing with honest mistakes, particularly with smaller, volunteer-run charities, for which education would be more beneficial than punishment. Larger, professional charities are held to higher standards in this regard, as the public believe they should be more aware of procedures.

Given the limited real knowledge of the Commission, there is less certainty as to whether this balance is currently being met.

“If they are doing wrongdoing, they need to know why and then support them to do the right thing.”

“Obviously they should be a commission to help charities do the right thing but also, they need to regulate as well.”

Q. Generally speaking, where do you think the balance of the Charity Commission’s work ought to lie? [Respondents that know the commission very/fairly well]

| Responsibility | Respondents that know the commission very/fairly well | Trustees |

|---|---|---|

| More on identifying and dealing with wrongdoing than on supporting charities to do the right thing | 20% | 6% |

| Equally on identifying and dealing with wrongdoing and on supporting charities to do the right thing | 61% | 81% |

| More on supporting charities to do the right thing than on identifying and dealing with wrongdoing | 17% | 10% |

| Don’t know | 2% | 3% |

The Commission should hear and consider external voices, but must not allow them to directly influence regulation

Independence, but not ignorance

Very few people have genuinely considered the external forces that could influence the Commission. Quantitative and qualitative data alike suggest there is some perceived outside influence, particularly from charity law and the charity sector, though even when asked to only those that say they are familiar with the Commission’s work, answers are largely the result of supposition.

Interviewees tend to suggest the Commission should acknowledge external influences, yet not let them distract from their independent regulation. For instance, if an investigative journalist were to write about an incident of charity wrongdoing, the public would want the Commission to turn its attention to the case in question but must still conduct its own processes to reach an unbiased and fair conclusion.

“In terms of how they regulate, I don’t think they should take a big stock on individuals’ opinions. But I suppose if there’s a really big scandal going on, that should be given some attention.”

“If it’s an independent body, they shouldn’t be pressured into making decisions that would go against the whole idea of the Commission.”

| External force | % who feel the work of the Commission is influenced by the following factors/groups | % of trustees |

|---|---|---|

| Charity law | 78% | 78% |

| The charity sector | 61% | 47% |

| The public | 42% | 29% |

| The media | 41% | 27% |

| Politicians | 40% | 27% |

Q. Did you feel that you knew enough about the Charity Commission and how it works to answer the previous question?

| Yes | 52% |

| Not really | 42% |

| Don’t know | 6% |

Registration continues to play a role in upholding trust & confidence

Percentage (%) of the public who have more confidence about each of the following if they know a charity is registered

| Registered charity | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| That a high proportion of the money it raises goes to those it is trying to help | 79% | 78% | 78% | 79% |

| That it’s making an impact | 77% | 78% | 76% | 77% |

| That it operates to high ethical standards | 79% | 75% | 74% | 76% |

| That it’s well run | 77% | 71% | 70% | 74% |

| That it treats its employees well | 69% | 67% | 65% | 69% |

| That it’s doing the work central and local government can’t or won’t do | 67% | 68% | 66% | 68% |

Methodology note

Quantitative data and analytics

Yonder surveyed a demographically representative sample of 4,316 members of the English and Welsh public between 24 and 31 January 2023. A boost was applied to the Welsh portion of the sample to ensure that we had over 500 responses from that nation. The survey was conducted online.

Answer options were randomised and scales rotated. All questions using opposing statements were asked using a sliding scale.

The data was analysed using Yonder’s ‘Clockface’ model to help understand the various elements of public opinion and ensure the Charity Commission’s work is rooted in an understanding of the social and economic dynamics at play across the English and Welsh public.

Qualitative data

Yonder conducted 20 in-depth interviews with members of the public from across the Clockface model’s two-dimensional map of ‘security’ and ‘diversity’ and with a geographical spread across England and Wales. Interviews were conducted between 13 and 20 March 2023.

Each interview lasted around 30 minutes.

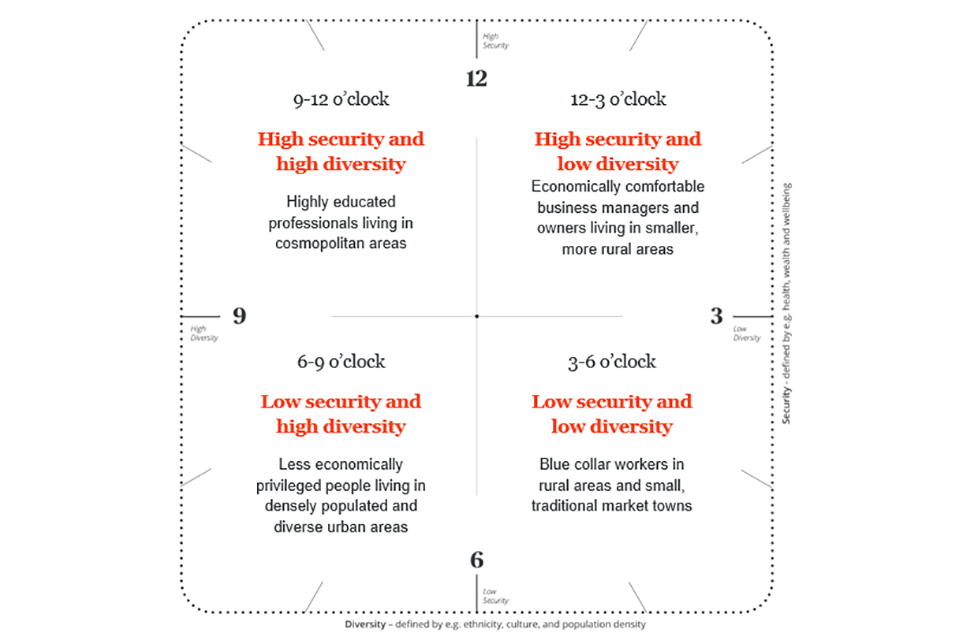

Annex 1 - Introduction to the Clockface

Introduction to the Clockface: who are ‘the public’ and what does ‘charity’ mean to them?

Public opinion isn’t monolithic

Statistics about public opinion usually hide a very important truth – that there is no single ‘public opinion’.

Instead, whether we know it or not, we all exist within bubbles that we tend to share with people who have similar demographics, backgrounds, and circumstances to ourselves.

Those demographics, backgrounds and circumstances go a long way in explaining differences of opinion and behaviour. They help to shed light on things that unite us and the things that increasingly seem to divide us.

If you associate only with people from your own social and educational background, you risk two things: overestimating the extent to which people outside your direct experience agree with you; and demonising those who don’t.

We use a model of the population – called the Clockface – to help us to avoid that by understanding and defining the differences of opinion that exist between different corners of the population.

Every person in the country occupies a position on the Clockface map that is shown on the next page.

The position that every person occupies on the Clockface is defined by two sets of characteristics:

- security, combining measures of health, wealth and wellbeing such as income, occupation and education

- diversity, a combination of factors including ethnicity, culture and population density which determine how close you are to your neighbour in distance or background

People located between 12-3 o’clock, for instance, are high in the bundle of measures we call ‘security’ but low in those we call ‘diversity’, and that will influence how they behave, think and feel.

Applying polling data to this model can show us exactly how these differences in outlook play out.

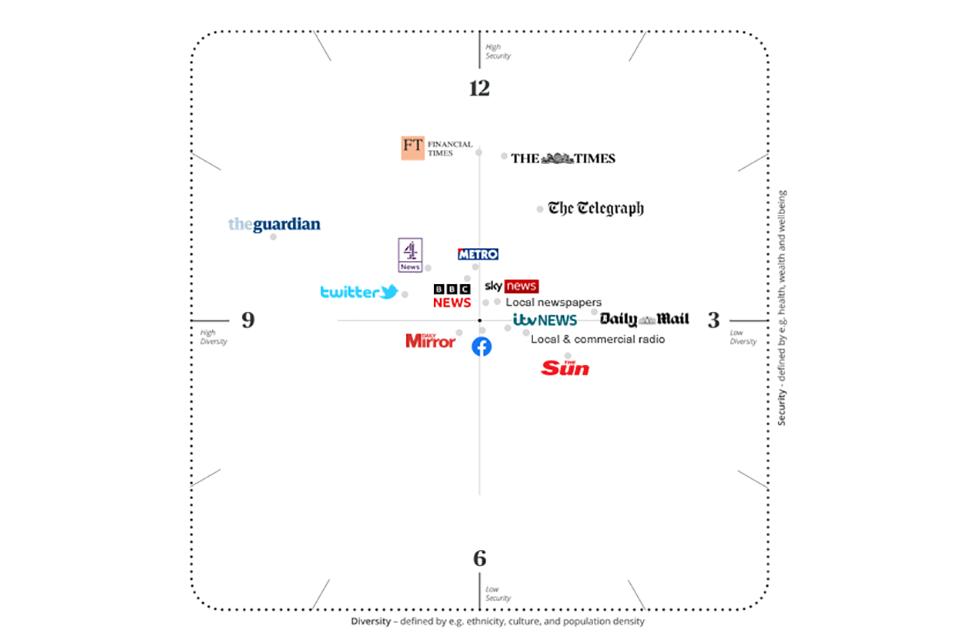

Take something like where you get your news.

Here is the average position on the Clockface of those who say they get their news at least once a week from the sources shown. The Clockface image shows, for example, that you are most likely to find a reader of the Guardian in the high diversity, high security quadrant; a Sun reader in the low security, low diversity quadrant.

You can of course find readers or viewers of any particular source anywhere on the map, but the Clockface image show where you are more likely to encounter them.

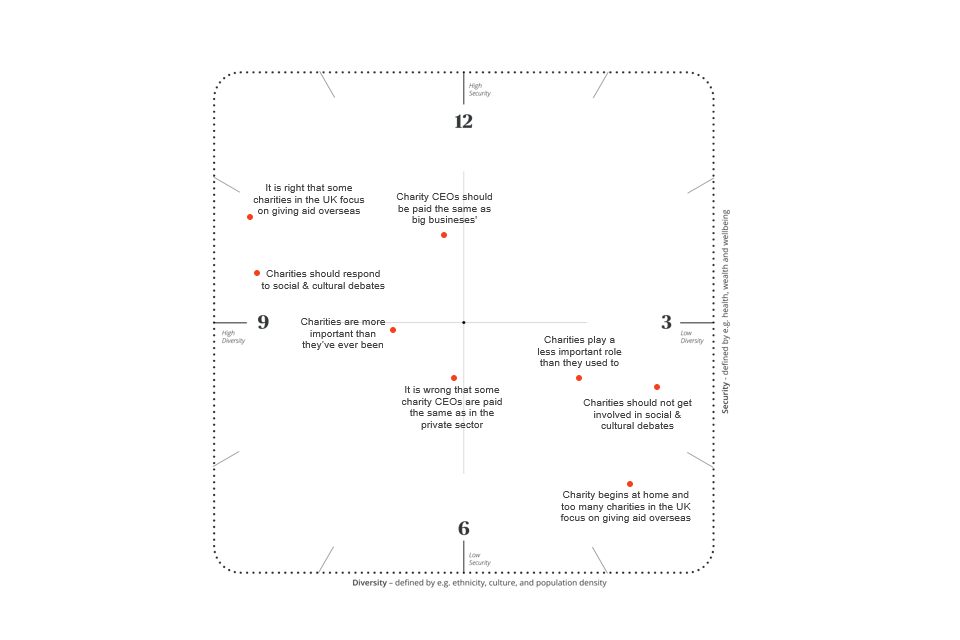

The public & charity

Views about charities can also be placed on the Clockface.

Whether people prefer charities with a local or international focus, whether it is acceptable for their work to overlap, whether they should be run by professionals or volunteers – you can encounter different points of view on issues like these anywhere in the population, but certain perspectives are more prevalent among some parts of the public than others.

Those prevalences reflect the different experiences and circumstances that shape people’s thinking and behaviour.

There are certain things that unite all parts of the public across the Clockface – like the expectation that donors’ money should reach the intended cause or that charities must provide evidence about the impact they’re having.

But there are other issues – like the role charities should play in shaping wider social and cultural debates – for which it is harder to reconcile different parts of the public and their different standpoints.

A view that might seem self-evidently correct to a person in one part of the Clockface could be strongly contested by someone else in another.

The Clockface image below shows that you are most likely to find supporters of overseas charities and those who think that charities should engage in social and cultural debates in the higher security, higher diversity part of the population. Those who think the opposite are most likely to be found in the lower security, lower diversity part of the population.

In the following pages, we outline the public opinion landscape in 2022 and try to unpick those differences, so that the charity sector can better navigate them.