Reducing Parental Conflict Programme Evaluation: second report on implementation

Updated 17 April 2023

Applies to England

DWP research report no. 1002

A report of research carried out by IFF Research on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2021.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence or write to the:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our website at Research at DWP.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk.

First published November 2021.

ISBN 978-1-78659-353-5

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

Background and methodology

The government wants every child to have the best start in life and reducing harmful levels of conflict between parents - whether they are together or separated - can contribute to this. Sometimes separation can be the best option for a couple, but even then, co-operation and good communication between parents is essential for their children. This is why the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) introduced the Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) programme. Originally backed by up to £39m until March 2021, with additional funding and an extension of the programme secured until March 2022, the programme is encouraging local authorities across England to integrate services and approaches which address parental conflict in their local provision for families. Evaluation is central to the RPC programme. Findings from this evaluation will contribute to the wider evidence base on what works for families to reduce parental conflict and will support local authorities and their partners to embed the parental conflict agenda into their services.

This is the second report from the RPC programme evaluation, providing interim findings on implementation from research conducted in 2019 up to January 2021.

The evaluation consists of 3 strands which correspond to 3 programme elements:

- intervention delivery: To assess how the provision of evidence-based interventions in 31 local authorities, clustered in 4 geographical areas, is implemented and delivered and the impact of the interventions in reducing parental conflict and improving child outcomes[footnote 1]

- training: To study whether and how the training of practitioners and relationship support professionals has influenced practice on the ground - focusing on the identification of parents in conflict, building the skills and confidence to work with, or refer, parents in conflict and the overall support available

- local integration: To examine to what extent local authorities across England have integrated elements of parental conflict support into mainstream services for families, how and with what success

Intervention delivery

Introduction

Eight interventions to address parental conflict are being tested as part of the programme. Interventions are of either a moderate or high intensity. Parents are allocated to the interventions on the basis of the level of conflict in their relationship.

Intervention delivery findings

Frontline practitioners making referrals generally felt confident identifying the signs of parental conflict in order to then make a referral. However, some reported limited understanding of the individual interventions available in their area. Both referral staff and providers felt that this could be restricting the number of eligible referrals, with assumptions in some cases that expectant parents, parents in work and cases where only one parent is interested would not be eligible when in fact they would. This was evident in interviews conducted both in autumn 2019 and winter 2020.

Providers had experienced lower than expected rates of referrals. In particular, they felt the strict eligibility criteria of 2 interventions, “4Rs 2Ss” and The Incredible Years Advanced, meant these interventions had secured very low referral volumes. The former is aimed at parents of 7 to 11 year olds with a diagnosed misconduct issue and, at the time of this research, the latter required completion of The Incredible Years Basic course, however this prerequisite was relaxed in early 2021.

Some providers indicated that referral rates had increased since March 2020. In part this was attributed to moving provision to digital delivery models as a result of the social distancing restrictions that were imposed because of the coronavirus pandemic. These providers felt that digital delivery removed some of the logistical barriers to participation.

Providers were extremely positive about the content of the interventions, stating that they were relevant to parents referred and provided effective strategies for parents to use. One of the few negative comments made was that The Incredible Years Advanced course was perhaps a bit too long for many parents.

Start rates, dropout rates and completion rates varied by intervention. Early indications show that the Mentalisation Based Therapy intervention had the widest appeal (with the most referrals and starts to the intervention). Providers suggested that this might be because it is closest to what parents might expect from an intervention about parental conflict (whereas the scope of other interventions is wider, focusing on other elements of home life, rather than solely on the inter-parental relationship).

Training

Introduction

As part of the RPC programme, the DWP appointed a training provider to develop a training package about parental conflict, primarily aimed at practitioners in frontline local authority services. It includes modules covering the theoretical context underpinning the programme, identification of, and strategies to address, parental conflict and a specific module targeted at supervisors to enable them to support their colleagues working with parents in conflict. In addition, there is a Train the Trainer workshop intended to build the capacity of those already skilled in training to deliver training about parental conflict and the impacts of it.

Training findings

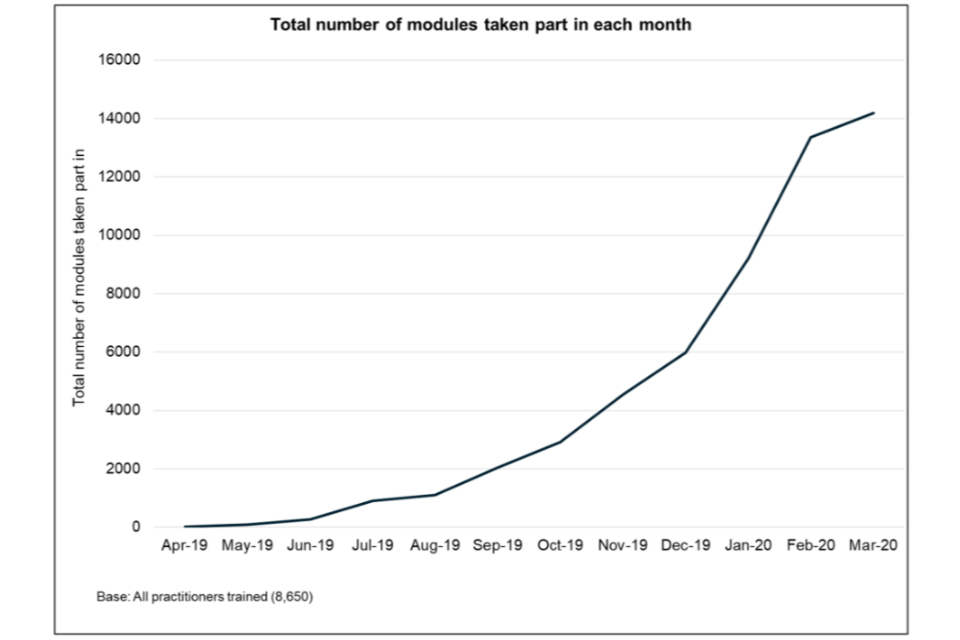

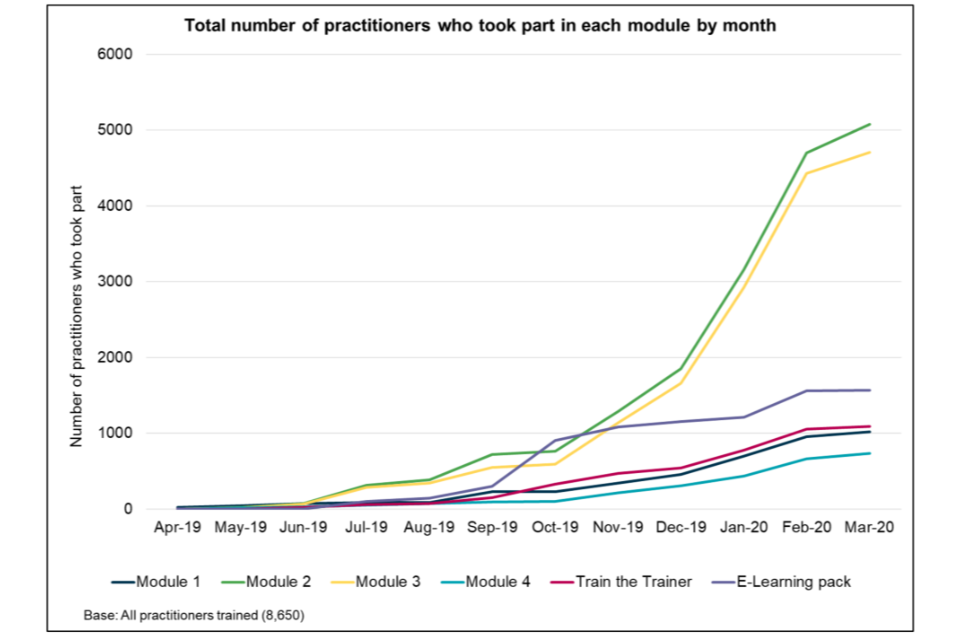

As part of the programme, local authorities could apply for a Practitioner Training (PT) grant to purchase places on this training. Nearly all local authorities confirmed they had taken up the PT grant ensuring a wide reach for the training.

Overall participants were positive about all of the training package. It was praised as being relevant to their work and providing adequate levels of detail. Participating in the training significantly improved practitioners’ ratings of their own knowledge, understanding and abilities relating to addressing parental conflict.

At a point 6 months after taking part in the training, the majority of practitioners had applied their training to their day-to-day roles, most commonly to help identify children/families who may be affected by parental conflict and to start conversations about parental conflict once a concern had been identified. A third of practitioners were applying their training at least weekly, though overall practitioners were applying their learning less frequently than they anticipated when training was initially received. This could be related to the restrictions imposed by the coronavirus pandemic.

The Train the Trainer workshop had limited impact at the point 6 months after taking part with fewer than one in 10 (9%) participants delivering any training modules on reducing parental conflict in their local area at this point (although a large proportion planned to do so).

The majority of participants reported some degree of cultural change within their organisation as a result of the training; a third reported that parental conflict was being treated as a much more important issue.

Local integration

Introduction

The local integration element of the programme aims to encourage local areas to consider the evidence base around parental conflict and integrate support for parents in conflict into existing provision. To support local areas with integration DWP:

- recruited a team of 6 Regional Integration Leads (RILs) to promote the agenda and facilitate knowledge sharing and networking[footnote 2]

- provided a Strategic Leadership Support (SLS) grant for local authorities and their partners to use in ways that best suited their aspirations in respect of reducing parental conflict

- encouraged access to information made available on the reducing parental conflict online hub hosted by the Early Intervention Foundation (EIF)[footnote 3]

Local integration findings

Frequency of contact with the RILs had decreased slightly by autumn 2020 (compared with summer 2019), which is, perhaps, in-keeping with the programme reaching a more mature state. Local authorities were still very positive about the support provided by the RILs.

Nearly all of the local authorities confirmed that they had taken up the SLS grant although not all had spent it in full by autumn 2020. The most common use or planned use was on activities that would enable knowledge sharing between local professionals, such as events, workshops and multi-agency working groups.

There were several positive indications of progress with integration between summer 2019 and autumn 2020.

In terms of development of strategies:

- more local authorities had a specific multi-agency strategy

- more local authorities reported that local commissioning decisions were aligned to reducing parental conflict strategies

- there was an increase in the proportion of local authorities that had embedded reducing parental conflict into mainstream services

In terms of recording parental conflict systematically:

- more local authorities reported that frontline practitioners were routinely asking parents about the quality of their relationship

- more local authorities had an explicit question about parental relationships in Early Help assessments

In terms of support available for parents:

- more local authorities reported providing support for parents experiencing conflict

However, the level of signposting and referrals of parents to support is not known as most local authorities were unable to report this.

Sustainability

Introduction

Ultimately, DWP hopes that the components of the RPC programme will be sustainable once central funding finishes.

Sustainability findings

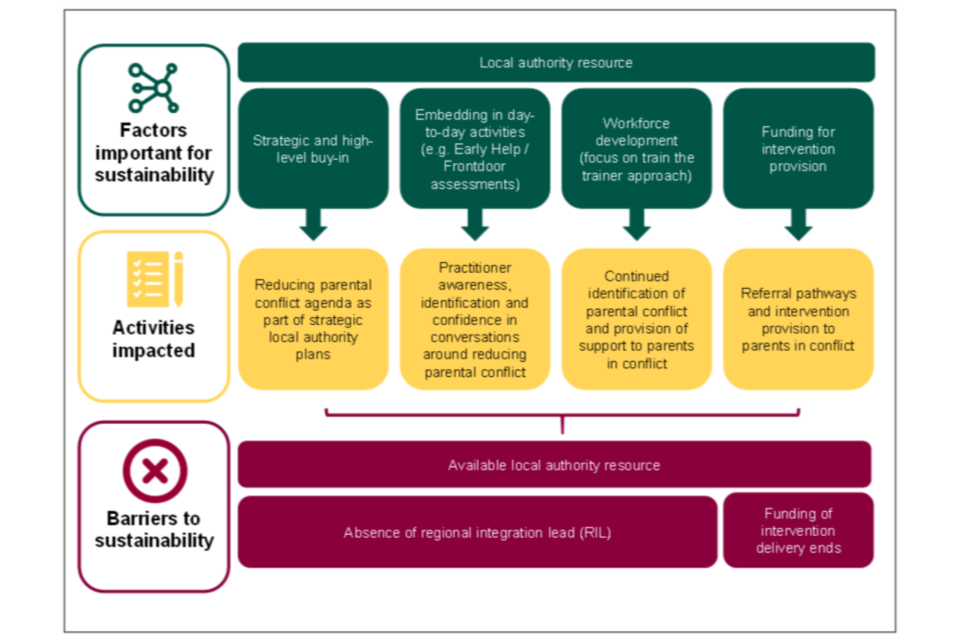

RILs and local authorities themselves felt that the sustainability of the reducing parental conflict agenda once the programme comes to an end (which, at the time of the research, was planned for March 2021) would vary by both local authority and by the different elements that make up the programme. Resourcing challenges were highlighted as a key threat to the sustainability of the programme.

Factors that were felt to help with sustainability included low/no cost changes that helped to embed consideration of parental conflict in day-to-day processes. These included changes to tools such as Early Help / Front Door assessment forms to record identification of parental conflict and processes to encourage practitioners to have conversations about parental conflict.

RILs and local authorities highlighted the importance of securing strategic buy-in to the inclusion of reducing parental conflict metrics in outcome frameworks.[footnote 4] The importance of making use of the Train the Trainer approach to workforce development was also highlighted.

The area of greatest concern with regards to sustainability surrounded the delivery of interventions. Providers and local authorities were concerned they would be unable to fund these going forward.

Evaluation

This is the second report from the RPC programme evaluation, providing findings on research conducted in 2019 up to January 2021.[footnote 5]

The following data collections were completed between the production of the first report and January 2021 when this report was compiled:

- 6 in-depth interviews with RILs on the types of activities they had undertaken and the responses of different local authorities

- an online survey of local authorities and 5 case study visits in the second half of 2020 focussed on progress made since the last research with local authorities in summer 2019. The case studies also included some interviews with providers delivering the interventions

- 2 waves of surveys of frontline practitioners who had taken part in the training conducted 1 and 6 months after taking part. The first survey attempted to baseline practitioner knowledge and confidence before and directly after training. Wave 2 explored the extent to which they had been able to apply the knowledge and skills that they had acquired through the training in their day-to-day roles. The first report on implementation covered initial findings from wave 1 and this report includes full findings from both waves

- 45 depth interviews with practitioners taking part in the training. The interviews covered expectations of the training, what they felt about the content and delivery of the training and how they expected to be able to apply their learning in their day-to-day roles

- 60 telephone depth interviews with frontline practitioners that had made at least one referral to the Gateway Team that allocate individuals to the interventions

- 2 surveys of intervention delivery providers. The initial survey looked at experiences of delivery in the period running up to the first national lockdown in March 2020 and the second looked at experiences of delivery during the pandemic

Glossary

Children of Alcohol Dependent Parents (COADeP) Innovation Fund

The government announced this fund to support children living with alcohol dependent parents in April 2018. The fund is also tackling parental conflict among alcohol dependent parents and is co-funded by the Reducing Parental Conflict programme.

Contract Package Area (CPA)

Delivery of RPC interventions is taking place across 30 local authorities, which are clustered in 4 geographic areas known as Contract Package Areas. These are Westminster, Gateshead, Hertfordshire and Dorset.

Domestic Abuse

Conflict in a relationship where there will be an imbalance of power and one parent may feel fearful of the other.

Early Intervention Foundation (EIF)

The Early Intervention Foundation is an independent charity established in 2013 to champion and support the use of effective early intervention to improve the lives of children and young people at risk of experiencing poor outcomes.

Frontline Practitioner (FLP)

Local authority colleagues and their partners working with families including those who work for services such as social work, health visiting teams and early years’ services.

Parental Conflict

Parental conflict that is damaging can be expressed in many ways such as:

- aggression

- silence

- lack of respect

- emotional control

- lack of resolution

When parents are entrenched in conflict that is frequent, intense and poorly resolved it is likely to have a negative impact on the parents and their children. The Reducing Parental Conflict programme seeks to address conflict below the level of domestic abuse, where specialist services are required.

Practitioner Training (PT) grant

The Practitioner Training grant is used to buy spaces for staff in the local authority area to attend bespoke RPCP training delivered by Knowledgepool.

Reducing Parental Conflict (RPC) programme

The Reducing Parental Conflict programme is the subject of this evaluation. It aims to help avoid the damage that parental conflict causes to children through the provision of evidence-based parental conflict support, training for practitioners working with families and enhancing local authority and partner services.

Regional Integration Lead (RIL)

There are 6 RILs in England seconded from local authorities to DWP. They are available to provide expert advice and support to local authorities and their partners and maximise the opportunities that the programme presents.

Strategic Leadership Support (SLS) grant

The SLS grant is used to help local authorities and their partners to raise the profile of parental conflict and fund activities to integrate reducing parental conflict into their provision.

Chapter 1 Introduction, background and methodology

This chapter outlines the background to the project and provides an overview of the evaluation methodology. It also provides details on the elements of the evaluation that have been conducted between November 2019 (when the first interim report was produced) and January 2021.

Context

Parents play a critical role in giving children the experiences and skills they need to succeed. However, studies have found that children who are exposed to parental conflict can be negatively affected in the short and longer terms.[footnote 6]

Disagreements in relationships are normal and not problematic when both people feel able to handle and resolve them. However, when parents are entrenched in conflict that is frequent, intense and poorly resolved it is likely to have a negative impact on the parents and their children. It can impact on children’s early emotional and social development, their educational attainment and later employability – limiting their chances to lead fulfilling, happy lives.

The government wants every child to have the best start in life and reducing harmful levels of conflict between parents – whether they are together or separated – can contribute to this. Sometimes separation can be the best option for a couple, but even then, continued co-operation and communication between parents is better for their children. This is why DWP introduced the Reducing Parental Conflict programme. Originally backed by up to £39m to March 2021 with additional funding and an extension of the programme secured until March 2022. The programme is encouraging local authorities across England to integrate services and approaches which address parental conflict into their local provision for families.

The RPC programme seeks to address conflict below the threshold of domestic abuse. Where there is domestic abuse there will be an imbalance of power and one parent may feel fearful of the other. If domestic abuse is suspected or identified more specialist support should be offered.

Evaluation is central to the Reducing Parental Conflict programme. Evidence from the evaluation of the programme will contribute to the wider evidence base on what works for families to reduce parental conflict and will support local authorities and their partners to embed the parental conflict agenda into their services.

This is the second evaluation report, providing findings on programme implementation part way through the delivery period.

Delivery of the Reducing Parental Conflict programme

The programme is designed to increase the support that is available and provided to disadvantaged parents in conflict through different elements of activity.

- intervention delivery: Providing evidence-based interventions that are designed to reduce parental conflict and improve child outcomes

- training: Provision of training for multi-agency practitioners such as Family Support workers, teaching assistants or Police officers to increase understanding of the parental conflict evidence base, enhance their confidence and ability to identify and discuss parental conflict with parents and apply the evidence-base in family support practice. Provision for supervisors and managers to support their staff in integrating reducing parental conflict is also being delivered

- local integration: Provision of funding and backing to integrate elements of parental conflict support into mainstream services for families

- a Challenge Fund to test innovative activity, including digital support (which is out of scope of this evaluation)[footnote 7]

- a package of measures, jointly funded with the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and Public Health England (PHE) to improve outcomes for children of alcohol dependent parents, some of whose parents are also in conflict

Evaluation

In January 2019 DWP commissioned a large scale, multi-method external evaluation of the programme. DWP analysts will conduct a complementary impact evaluation.

The external evaluation is largely a process evaluation through which the range of activities supported by the programme are being examined to build the evidence base about what works to reduce parental conflict. It is anticipated that this will support local authorities and their partners to embed the parental conflict agenda effectively in their services.

Mirroring the programme design, the evaluation covers the delivery of interventions, training and local integration. The main objectives for each element of the evaluation are:

- intervention delivery: To assess how the provision of evidence-based interventions in 31 local authorities, clustered in 4 geographical areas, is implemented and delivered and the impact of the interventions in reducing parental conflict and improving child outcomes[footnote 8]

- training: To study whether and how the training of practitioners and relationship support professionals has influenced practice on the ground - focusing on the identification of parents in conflict, building the skills and confidence to work with, or refer, parents in conflict and the overall support available

- local integration: To examine to what extent local authorities across England have integrated elements of parental conflict support into mainstream services for families, how and with what success

The table below shows the different evaluation components that were ongoing or completed at the time of this report. All elements included in Table 1.1 are discussed in this report.

Table 1.1 The RPC programme evaluation elements completed or ongoing at the time of this report

Covered in Report 1 (but referred back to in this report):

| Integration | Training | Delivery of interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Depth interviews with Regional Integration Leads (wave 1) | Depth interviews with local authority managers and commissioners (includes coverage of SLS) | |

| Online survey of local authorities (follow-up 1) | Online survey of practitioners trained (wave 1) | |

| Case studies of local authorities (wave 1) | Online survey of practitioners trained (wave 1) |

Covered in Interim Report 2 (this report):

| Integration | Training | Delivery of interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Depth interviews with Regional Integration Leads (wave 2) | Depth interviews with practitioners trained | Depth interviews with referral staff (referring parents to interventions) (wave 1 and 2) |

| Online survey of local authorities (follow-up 2) and full findings from follow-up 1. | Online survey of practitioners trained (wave 2) | Survey of intervention delivery providers (wave 1 and 2) |

| Case studies of local authorities (wave 2), which also includes visits with providers (first 5 case studies) |

The evaluation components in Table 1.2 had not been completed at the time of this report. These elements will be completed and reported on in the future.

Table 1.2 The RPC programme evaluation elements to be completed in the future and included in future reports[footnote 9]

| Integration | Training | Delivery of interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Depth interviews with Regional Integration Leads (wave 3) | Online survey of practitioners trained digitally | Survey of participants (6 months after taking part in the intervention) |

| Case studies of local authorities (wave 2), which also includes visits with providers (remaining 5 case studies) | Survey of non-completing participants | |

| Case studies of local authorities (wave 2), which also includes visits with providers (remaining 5 case studies) | Depth interviews with participants |

Methodology

This section provides detail on the approach taken for each of the evaluation elements covered in this report. In-depth interviews with Regional Integration Leads (wave 2)

Six RIL posts were created for the RPC programme to provide support across all 150 upper tier local authorities. RILs were seconded from local authorities to DWP to provide this support for the duration of the programme. The first RIL began in their role in April 2018. Each RIL was assigned one of the following regions to support – London, South East, Midlands, South West, North East and North West.

A 2-hour face-to-face interview was conducted with each of the RILs in February-March 2020, a year after initial interviews with them took place. The interviews with RILs explored the ongoing contact they had had with local authorities, activities that their local authorities were engaged with and their views on the sustainability of the programme. The interviews also explored their experiences of the RIL role. A semi-structured topic guide was used for the interviews.

Online survey of local authorities (follow-up 2)

The survey of local authorities was conducted between July and December 2020.

The online survey invites were sent to the Single Point of Contact (SPOC) that each local authority had nominated for communication relating to the RPC programme. Contacts from all 150 local authorities were invited to take part. Several e-mails were sent, and telephone calls were made to try to boost the response. The survey achieved a 48% response rate (72 local authorities completed the survey). The survey took an average of around 20 minutes to complete.

A breakdown of the characteristics of survey respondents is provided in Annex 1.

Case studies of local areas (wave 2)

Five case studies of local authorities and their partners took place between November 2020 and January 2021. The case studies consisted of in-depth interviews and/or mini groups with the reducing parental conflict lead and other staff that had been involved in the development of strategies to reduce parental conflict.

The local authority areas were selected to ensure a spread across regions, a mix of those located in Contract Package Areas (CPAs) trialling RPC interventions and those outside CPAs, as well as including some who participated in wave 1 to give a longitudinal picture. For local authorities in CPAs, interviews were also conducted with a provider delivering one of the interventions funded by the RPC programme.

The case studies covered what each local area had implemented to date, their key barriers and successes and how reducing parental conflict will be taken account of in the future. A semi-structured topic guide was used to aid the discussions.

A breakdown of the characteristics of the case studies is provided in Annex 2.

Frontline practitioner training survey (wave 2)

This survey was conducted with frontline practitioners 6 months after completing the initial survey. The survey explored the extent to which they had been able to put into practice the knowledge and skills that they had acquired through the training.

The survey was conducted online, and invites were issued monthly, 6 months after completion of the initial survey. All 598 practitioners who completed the initial survey and agreed to be re-contacted were invited to take part and responses were secured from 147 (a 25% response rate).

On average the survey took around 13 minutes to complete.

The profile of respondents to the survey is shown in Annex 3.

Depth interviews with practitioners post training

Forty-five depth interviews were conducted by telephone with individuals who had attended face-to-face practitioner training. Individuals were recruited through the wave 1 survey and took place between October and November 2019. The interviews were structured to ensure a mix of different roles and coverage of those attending each of the training modules.

The interviews covered expectations of the training, what participants felt about the content and delivery of the training and how they expected to be able to apply their learning in their day-to-day roles. Interviews were underpinned by a semi-structured topic guide.

A profile of the individuals interviewed is provided in Annex 4.

Depth interviews with referral staff (wave 1 and wave 2)

Sixty telephone depth interviews were conducted with frontline practitioners who had made at least one referral to the Gateway Team that allocate individuals to the interventions. Interviews took place between October and November 2019.

These interviews covered practitioner awareness and understanding of the different interventions, understanding of eligibility requirements, the process of identifying parental conflict and the referral process.

A profile of the individuals interviewed at wave 1 is provided in Annex 5.

A further 45 depth interviews were conducted between November 2020 and January 2021. These covered similar ground but at a point when the referral process was more established.

At each stage interviews lasted 45 minutes to an hour. The profile of individuals interviewed at wave 2 is also in Annex 5.

Survey of intervention delivery providers (wave 1 and wave 2)

A mixture of qualitative and quantitative information was collected through a semi-structured telephone survey of providers delivering the interventions. The initial survey took place in March and July/August 2020 (the period immediately pre and post the first coronavirus national lockdown). This first survey explored experiences of delivery prior to lockdown which was predominantly face-to-face.

The survey largely covered prime providers who were asked separate questions about each of the individual interventions that they delivered (hence each respondent was asked to provide information about up to 4 different interventions). In total, the survey collected 35 responses from 12 different providers.

A similar approach was taken for wave 2 which collected 27 responses from 10 different providers. These interviews took place in November – December 2020.

Wave 2 was designed to capture delivery adaptations made to enable remote delivery and provider reflections on the opportunities and challenges this presented.

Chapter 2 Intervention delivery

This chapter explores the experiences of frontline practitioners in identifying parental conflict and referring parents onto interventions being provided as part of the RPC programme. It also covers the experiences of providers delivering these interventions, both before and after the first national coronavirus lockdown period.

Introduction to intervention delivery

The testing of interventions through the RPC programme aims to deliver evidence about what works to reduce parental conflict and improve children’s outcomes.

Eight different interventions were implemented as part of the programme (further details on these is outlined in Table 2.1). These were designed to be delivered face-to-face, but were quickly adapted to be delivered virtually in response to the coronavirus pandemic. Some of these have a promising evidence base supporting their efficacy in the UK, but not necessarily for all family types, for disadvantaged families or for different delivery methods. Others have been successful in non-UK settings but have not been tested in the UK. In all cases the interventions being implemented present significant opportunities for learning.

The interventions aimed to achieve a number of short-term and longer-term outcomes for both parents and children as set out in Figure 2.1, based on a number of inputs and assumptions that stem from the provider delivery. The research covered in this report explores some of the assumptions and short-term outcomes in this model.

Figure 2.1 Logic Model for Interventions delivery

Inputs:

- research to identify promising interventions

- securing rights to deliver interventions

- development of a process to identify and refer parents to interventions

- establishing and funding provider contracts to deliver interventions

Assumptions:

- frontline practitioners are able to identify parents in conflict

- frontline practitioners are able to navigate the referral process

- providers are able to organise the logistics of course delivery (pre and during COVID)

- providers ‘believe’ in the value of the interventions to parents

- parents are motivated to attend and complete

- providers are able to access training

Short-term outcomes for parents:

- parents obtain new information through attending interventions

- parents feel better equipped to address conflict

Longer-term outcomes for parents:

- improvement in parental relationships

Longer-term outcomes for children:

- avoidance/reduction of negative impacts for children

Interventions are of either a moderate or high intensity. Parents are allocated to the interventions on the basis of the level of conflict in the relationship. This is identified via an assessment tool developed for the programme by subject matter experts and known as the Referral Stage Questionnaire (RSQ). This is administered to parents by a frontline practitioner working with the family. It consists of a range of established assessment scales to identify the types and levels of conflict parents are experiencing. It examines the mechanisms through which child outcomes are affected, and the features of an inter-parental relationship that have been shown to impact on children’s outcomes. If either parent scores high for conflict, both parents are offered a high intensity intervention. Flexibility was granted with regards to the intensity of intervention in early 2020, enabling providers to offer parents either high or moderate interventions in certain circumstances, regardless of RSQ outcome. Some interventions are delivered in a group setting, some as couple sessions and some on an individual basis. Couples who remain in a relationship as well as those who have separated are eligible. Existing and expectant parents are eligible.

The full list of interventions is shown below. Delivery of these interventions continued throughout the coronavirus pandemic and lockdown with the majority switching to digital delivery over Teams or Zoom; this will be covered in more detail later in the chapter.

Table 2.1 Interventions being delivered

| Intervention Name | Brief Description | Method of delivery | Target group | Length of delivery | CPA | Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4Rs 2Ss Family Strengthening Programme | Curriculum-based practice designed to strengthen families, decrease child behavioural problems, and increase engagement in care. It focuses on evidence-informed parts of family life that have been empirically linked to youth conduct difficulties. | Groups of 12-20 parents | Both intact and separated couples with children aged 7-11 | 16 weeks | Hertfordshire | High |

| Family Check Up | This involves 3 stages; an initial interview, family and child assessment, and feedback. The second stage involves the delivery of Everyday Parenting (EDP), which is a behavioural parenting intervention tailored to meet specific needs. | Delivered to individual parents (either one or both parents) | Both intact and separated couples | 9 sessions of 50-60 minutes | Dorset Westminster Gateshead Hertfordshire |

Moderate |

| Enhanced Triple P | This is a targeted selective intervention, which aims to address family factors that may impact upon and complicate the task of parenting, such as parental mood and partner conflict, and problem child behaviours. | Delivered to individual parents (either one or both parents) | For both intact and separated couples | 4 modules delivered to families in 3 to 8 individualised consultations (8-12 hours) | Westminster | High |

| Family Transitions Triple P | Designed as an intensive intervention for parents experiencing difficulties as a consequence of separation or divorce, it focuses on developing skills to resolve conflicts with former partners and how to cope positively with stress. | Groups of approximately 8 parents (separated parents are encouraged to attend different sessions) | Separated couples only | 5 sessions lasting 2 hours each | Dorset Westminster |

High |

| Mentalisation Based Therapy – Parenting under pressure | Aims to help couples experiencing high levels of inter-parental conflict gain more ‘perspective’ in order that they can start to put the needs of their children first. It is based on a model which comprises an initial phase of preparation and assessment, meeting with each parent separately. | One practitioner delivers sessions to intact couples. With separated couples each parent completes sessions with a separate practitioner. In rare cases the parents can complete the final session together with both practitioners. | For both intact and separated couples | 10 sessions of therapeutic work | Gateshead Hertfordshire |

High |

| The Incredible Years, including Advanced Programme | The focus is on parents’ and children’s communication and problem solving skills, knowing how and when to get and give support to family members and recognising feelings and emotions. It’s a group programme, basic is approximately 16 weeks with an additional 8 for advanced. | Group sessions of 12-20 parents | Couples and separated co- parents with children aged 4-12 years | 12-20 sessions as part of the ‘Basic’ course, with an additional 9-11 session for ‘Advanced’ (average of up to 20 weeks) | Dorset Gateshead |

High |

| Parenting when Separated | Drawing on international long-term evidence, it highlights practical steps parents can take to help their children cope and thrive as well as coping successfully themselves, where the parents are preparing for, going through or have gone through separation or divorce. | Group intervention delivered by 2 practitioners to groups of 12 participants | Separated couples only | 6 week course of 2.5 hour sessions | Gateshead Hertfordshire |

Moderate |

| Within My Reach | This is a targeted selective intervention, for low-income single parents, who may or may not be in a relationship. The intervention therefore targets relationship outcomes in general, rather than focusing on parenting or parental conflict. It covers 3 key themes; Building Relationships, Maintaining Relationships and Making Relationship Decisions | Delivered in a group to individuals (not couples) | Separated couples only | 15 sessions, each lasting 1 hour | Dorset Westminster |

Moderate |

Emerging findings

- practitioners usually felt confident identifying the signs of parental conflict in order to make a referral, although the lockdown restrictions, curtailing face-to-face interaction with families, made identification more challenging after March 2020

- there was evidence of some confusion among referral staff about the eligibility of families experiencing domestic abuse, working families, those expecting a child and couples where only one of the parents wanted to take part

- overall, practitioners felt the referral process was straightforward, quick and generally worked well

- providers had experienced lower than expected rates of referral. For some interventions, providers partly felt this was due to a lack of frontline practitioner awareness or understanding of the intervention for them to adequately explain the intervention to parents or be confident a referral was appropriate

- providers felt the strict eligibility criteria for some interventions prevented referrals being secured in sufficient volumes. This was particularly the case for “4Rs 2Ss” and The Incredible Years Advanced

- delivery of the majority of interventions was underway before the coronavirus national lockdown began in March 2020, though most providers started delivery later than planned. This was primarily due to low levels of referrals, with access to intervention training for delivery staff and paperwork also contributing to delays

- almost all interventions moved to digital delivery through video-conferencing platforms such as Zoom or Teams at the start of the coronavirus pandemic. This transition was generally considered to have worked well for all interventions and was seen to bring some benefits including more flexibility with timings and increased parent participation

- providers praised the content of interventions and the positive impact they can have on parents who take part

- provider staff were comfortable delivering the interventions, particularly commending the resources and materials. The move to digital delivery required initial support for practitioners but once they adjusted, they felt it worked as well, if not better, than before

- Parents Plus; Parenting When Separated appeared to have higher drop-out rates, with the group nature of delivery seen as one reason for this

- providers felt the Incredible Years Advanced intervention was particularly long, due to the necessity to complete the basic course ahead of this, and did not explicitly address relationships early on, both factors which they felt had led to high drop out and low completion rates

Findings explained

Identification of parents in conflict

For parents to be referred to the interventions, frontline practitioners who are providing local services to families, such as social workers or Early Help workers, identify the parents as being in conflict. They then use a Referral Stage Questionnaire (RSQ) to determine the level of relationship distress and make a referral to an intervention if appropriate.

When interviewed in both autumn 2019 and winter 2020, practitioners usually felt confident identifying the signs of parental conflict in order to make a referral. However, in winter 2020 some practitioners commented on the challenge of identifying conflict remotely, following the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic.

Initial identification of parental conflict

Before referring parents to the interventions, many practitioners did not use a screening tool to initially identify parental conflict but instead relied on the knowledge they had about the families based on their relationship with them. In both autumn 2019 and winter 2020, the information they used to judge the need for a referral to the interventions came from observations of the family dynamic and behaviours and conversations with parents and children. (Although, this was more difficult to conduct face-to-face following the coronavirus pandemic).

When we’re doing our home visits, we’re making observations all the time, how maybe the children are, how Mum and Dad are, how they’re interacting if they happen to be at home together.

Sometimes on the referral you can see that there are issues between mum and dad, or the young person will say they can’t take the arguing.

If parents are open and honest, it’s pretty easy to discover whether there is conflict in the relationship.

Frontline practitioners

Whilst many practitioners relied on their professional opinion of the family, others used assessment tools to help them diagnose issues impacting on the family. Across both time points a variety of tools for assessing families were used, rather than parental conflict specific tools. For example, practitioners used Early Help assessments, Recover STAR, Family STAR, Safer Lives, mood assessments and, for identifying domestic abuse, the DASH assessment. Sometimes the RSQ, the questionnaire used to make the referral to the interventions, was also used as a tool to initially identify parents in conflict.

There can be that element of coercive control or that kind of thing that can be harder to unpick so sometimes it could be worth exploring it still with the family or even suggest would they be interested in completing the form. At that stage, it might help them understand if there are any issues… it can be used in more families than we think.

Frontline practitioner

Practitioners used the DASH assessment form and support from their team to help when the distinction between domestic abuse and parental conflict was unclear. Some practitioners referred to domestic abuse specialists within their team for support which was found to be helpful. However, some practitioners wanted additional support or training, including a potential tool, to help them distinguish between parental conflict and domestic abuse to ensure they refer parents to the right services.

Reasons for not referring parents to the interventions

In both autumn 2019 and winter 2020, there were a variety of reasons why practitioners would sometimes choose not to refer a family to the interventions, despite them showing signs of parental conflict. Sometimes this was due to eligibility criteria, for example, if the family was showing signs of domestic abuse and the practitioner was aware this made the family ineligible. In some circumstances, the practitioners felt that the conflict could be resolved in other ways, such as through their own internal services or private mediation, and therefore did not feel an intervention was needed. Another reason for not referring families in conflict was if a parent did not want to enrol onto the programme or only one parent wanted to engage.

Discussing parental conflict with families

When it came to discussing parental conflict with families, practitioners felt comfortable doing this. They felt having these difficult conversations was a key part of their role and rapport building with families was essential in being able to have open conversations. In addition, they felt their previous experience helped them to have these more difficult conversations.

Identifying parental conflict during the coronavirus pandemic

When interviewed in winter 2020, practitioners generally felt that the coronavirus pandemic had impacted their ability to identify parental conflict and refer families to the interventions. A reduction of face-to-face visits with families from March 2020 meant that many practitioners relied on their interaction with families via telephone or online to identify parental conflict and refer them to the interventions, which many practitioners found challenging. Some practitioners felt this made it harder to pick up on the family atmosphere from cues from body language. It also meant they had fewer opportunities to build trust with families or potentially have private conversations with just one parent without their partner or children around.

Parents are likely to say “everything’s fine, everything’s fine” and we’re not able to get the full picture, to delve into what’s actually happening at home.

Frontline practitioner

However, there were some practitioners who felt that the process of identifying parental conflict remotely remained the same as prior to the outbreak of coronavirus. Some practitioners continued to see some families face-to-face or had the opportunity to visit the families in person at some stage, such as between the first and second lockdown or by visiting the families at their doorstep. This allowed them to identify parental conflict more as they had done pre-March 2020 – through picking up on the atmosphere and family dynamic.

Frontline practitioner experiences of navigating the referral process

Practitioners’ views on the role of the interventions

Frontline practitioners’ reactions to the interventions both in autumn 2019 and winter 2020 were usually positive. Many commented that the interventions had been beneficial in plugging a gap in support, with there being a lot of pre-existing support for cases of domestic abuse but not parental conflict.

I remember going to that event, then immediately thinking of the family that I referred in. I had them in mind straight away after that.

I thought it sounded really good because you can get a bit lost when parents are arguing and sometimes you don’t know how to deal with it very well so it was good to have a service that we could refer [families] on to.

I thought that would be really helpful because not every parent is suffering domestic abuse but it can easily get out of hand.

Frontline practitioners

When practitioners were asked in autumn 2019, there was a small group of practitioners who were not sure that the reducing parental conflict interventions were needed as they felt that most cases they encountered met the domestic abuse threshold.

Practitioners’ views on the information received about the interventions

When practitioners were asked in autumn 2019, the reactions to the information they received about the interventions were mixed. Most felt that the information, including leaflets, newsletters, emails, and presentations about the interventions were adequate and explained the interventions well.

A small group felt they did not have enough information about what the interventions consisted of, the referral process and how to use the RSQ which made some feel unprepared for conducting a referral.

I didn’t know whether they would go to the family home or parents would have to go to them and how long would it take – whether there was a waiting list.

I didn’t fully understand that, and I had several phone calls and emails because I felt that the information provided was not self-explanatory.

I’m not sure what the interventions entail; for example, how long they are going to last and where they are going to happen.

Frontline practitioners

However, those who had specific questions, including on the length of the interventions, the eligibility criteria (such as if they were eligible if one parent was working) and the referral process, felt their questions were answered sufficiently. As some practitioners found out about the programme from a presentation by the representative of the programme (including from the local authority, DWP and providers) or at an information sharing event, they were able to ask questions straightaway. Other practitioners sent specific queries they had to the Gateway Team.

Practitioners’ understanding of the interventions

When practitioners were asked in autumn 2019 about the interventions and who they were aimed at, understanding was mixed. Despite most staff feeling happy with the amount of information they had been provided with, a large group of staff knew very little about the interventions specifically and could not name all the interventions that were available in their local area. Some, however, commented that even though they could not recall this detail they knew where to access it. Awareness was better by winter 2020.

Of those who had a greater understanding of the interventions, practitioners often knew a lot about one of the interventions and very little about the others on offer. In these cases, Enhanced Triple P or the Incredible Years Advanced were the interventions that practitioners could provide more details on. This awareness and knowledge may be, in part, due to the familiarity of the practitioner with the basic and advanced versions of both interventions.

Practitioners’ understanding of the eligibility criteria of the interventions

Generally, practitioners lacked clarity on the finer details of the eligibility criteria for the RPC programme interventions as a whole and for each of the interventions available in their local area (see Table 2.1 for a breakdown of which intervention was available in each area). This was the case both in interviews conducted in autumn 2019 and in winter 2020.

The initial focus of the programme on workless families, which was broadened to include disadvantaged families, meant that some practitioners still assumed that only non-working families would be eligible for the interventions or they were uncertain about the eligibility of working parents. Understanding around the eligibility of families currently expecting a child was mixed, as some believed that the interventions were only for parents with children that had been born. As expectant parents are eligible, this confusion could potentially be resulting in some eligible parents not being referred.

There was also confusion around what happens if only one parent is willing to be part of the intervention. Practitioners were unsure if they would be able to refer the willing parent in these instances.

There was a great deal of uncertainty around whether families experiencing domestic abuse were eligible for the interventions.

I asked about it in the training because I wasn’t sure. They were saying that if it was low level DV and parents still wanted to make that change and we felt as practitioners there was no risk there, then we could but high level domestic abuse then no it would not be appropriate … we have to make a professional judgement on it.

Frontline practitioner

When practitioners were asked about eligibility criteria in winter 2020, there was still some confusion around the same issues as in autumn 2019. However, by winter 2020 there was also a group of practitioners who were able to correctly list or recognise all of the eligibility criteria, either spontaneously or when prompted.

Generally, practitioners were very keen to be provided with more detailed information on the interventions on offer at both time points. In particular, they wanted clarity over eligibility for each intervention and what the intervention would involve for the family. They felt this information would help them to explain the interventions in detail to the families they may refer, so they had more of a sense of what the intervention would involve. Some staff mentioned they would like a parent-friendly leaflet to share with families about the intervention to encourage parents to take part.

If there was more information about what these individual interventions look like, that would be helpful.

At the moment I’m just giving them the basics but if I could just leave them something that they could read through, or something online that would be helpful, to help them think about it.

I didn’t tell them much because I didn’t know much. You want to appear confident around families to instil some confidence in them, so I said look I don’t know much but I do know that it is around that conflict within the family unit.

Frontline practitioners

Practitioners’ experience of the referral process

When interviewed in both autumn 2019 and winter 2020, frontline practitioners reported that their overall experience of the referral process was positive, straightforward, and speedy. Figure 2.2 outlines the stages of the referral process.

Figure 2.2 Outline of stages of the referral process

-

Frontline practitioner identifies parental conflict within a family and decides whether they are suitable for the programme.

-

Frontline practitioner completes the RSQ and consent form with the family on paper.

-

Frontline practitioner submits the RSQ and consent form online and receives a confirmation from the Gateway Team.

-

The Gateway team review the RSQ and allocate the family to the suitable intervention.

-

Sometimes the Gateway team re-contact the frontline practitioner if there is missing information on the form or for clarification.

-

Once the family has been allocated to an intervention, the Gateway team contact the family to let them know about the course.

A few issues were raised around the RSQ, at both time points, focusing on the accessibility of its language and answer options. However, it was also seen as a useful tool for parents to begin reflecting on their relationship. The consent form (otherwise known as the Participant Agreement form) and submission process were generally seen as straightforward although some practitioners made some suggestions for ways to streamline the processes further, for example, by attaching the consent form to the RSQ so that it would not be forgotten.

The process of referrals made after March 2020 changed as a result of the coronavirus pandemic restrictions. This reduced the number of face-to-face visits practitioners had and led to some practitioners completing the RSQ and consent form with families on video or telephone calls and others emailing or posting the forms for families to complete without their support. Practitioners who completed the RSQ online found this easier than the original process which sometimes saw them completing the questionnaire by hand then translating it into the required software to submit.

Practitioners were not involved in the allocation of families to interventions or contacting them to let them know the intervention they had been allocated to. They were disappointed about this and would have liked an opportunity to share their professional opinion on the family to help with the allocation.

Practitioners would also, ideally, have liked to receive some contact after allocation to find out how families were getting on with the interventions. Some practitioners, interviewed in winter 2020, suggested that hearing about any positive impacts of the interventions on parents may have reminded and encouraged them to keep making referrals.

In winter 2020, some practitioners emphasised the importance of awareness raising of the programme among other practitioners to keep referrals happening, including regular reminders of the programme and what interventions are available locally. One practitioner commented that the turnover rate for social workers can be high meaning that regular reminders are required to keep awareness levels up.

Practitioners’ views on the Referral Stage Questionnaire (RSQ)

Practitioners reported that parents had mixed reactions to the RSQ when they presented it (both in autumn 2019 and winter 2020). They found that, in some cases, getting it completed was straightforward, whereas some parents struggled to complete the RSQ without a lot of assistance from the frontline practitioner.

Practitioners reported that motivated families, or parents who saw this as a last chance effort to resolve their issues, were generally happy to complete the RSQ. Some practitioners felt it was a good tool to begin getting parents to critically reflect on their relationship and see things from a different perspective.

It is almost an intervention in itself … it goes through all aspects of conflict so some questions will probably stay with them and they have reflected on it.

It got them thinking that maybe sometimes I could be a bit more lenient or see things in a different way. Some of the questions were really quite good at helping them, challenging their beliefs or seeing things from a two-way relationship rather than a single sided opinion.

Sometimes we kid ourselves that everything is fine and it’s just a bad day and we never do anything about it but having it visually there on the questionnaire makes you think and the questions are really good for doing that with the sliding scale.

Frontline practitioners

The difficulties experienced with the RSQ were around the length and complexity of it. Many felt that it would have been easier to complete if it was more concise and less dense.

Across both time points, practitioners flagged that the language was sometimes difficult for parents to understand, particularly if they had low literacy skills or learning difficulties. Practitioners felt parents struggled with some of the concepts in the RSQ, for example, “What is your philosophy on life compared to your partner?”. Practitioners also pointed out that the language barrier for ESOL parents was an issue without a translation of the RSQ into different languages.

Some practitioners felt the RSQ was sometimes difficult for parents to answer either because the scales did not allow for nuance in the response or because the questions were not appropriate to their situation. For example, the reference to “the last 4 weeks” in a number of scales was a struggle because a few parents felt that things fluctuated too much for them to say and the scales did not capture the ever-changing family dynamics.

Some staff were concerned that the RSQ relies on parents to be truthful to ensure that they are allocated to an appropriate intervention and has limited scope for practitioners to add their professional observations. Some staff had concerns around parents not being completely honest in the questionnaire, especially, if they had completed the forms near their partner. They also felt families were also sometimes reluctant to answer the financial questions as they felt they were too personal.

Some people will minimize their responses, which does not necessarily reflect the need… I felt the need [for referral] was higher than the response and the biggest learning point from this programme; where is the professional’s voice heard in relation to the questionnaire?

I went through the questionnaire and I could see she wasn’t being that honest … we did go through some of the things [again] … we had to do it again and she went through it on her own [again] and I still felt she wasn’t answering as she should have … I had to keep explaining because I knew her case.

Frontline practitioners

There were also some parts of the form that were reported to be uncomfortable for parents to answer or perceived as insensitive. For example, a few parents felt that it was strange and a bit uncomfortable that they had to answer some questions about one child. A few practitioners reported that they did not feel comfortable with the labelling of the forms as being “separated” or “in-tact”. The term “in-tact” was not felt to be very sensitive or appropriate.

Practitioners’ views on the Participation Agreement

In both autumn 2019 and winter 2020, practitioners found that parents were generally happy to complete the Participation Agreement (known colloquially as the consent form) and felt this was due to parents being used to providing their permission for their information to be shared between different agencies. A few practitioners noted that they were not initially aware of the Participation Agreement form, only the RSQ, so they had to return to families to ask them to complete it. One or two suggested that the form could be combined into one document with the RSQ so it is not missed. Some practitioners felt that the form was too wordy and long and a few parents did raise questions on the list of agencies involved, but this was rare.

Practitioners’ views on the submission process

The submission process was mostly perceived to be easy. However, some practitioners who were completing the forms with parents on paper felt that having to scan them or type them into an excel after the meeting to then be able to email them to the Gateway Team was a time-consuming process. A few practitioners also noted that colleagues with more limited IT skills did struggle with the process.

Although many said they had a quick response when they submitted the referral, some practitioners were frustrated when they did not receive an acknowledgement to their submission or to a query and had to chase for a response.

A few practitioners had the RSQ returned to them because families had stated N/A at some of the questions, or they had not answered some of the questions. Practitioners felt it was unnecessary for the questionnaires to be returned and resubmitted for what they considered to be minor issues, which they stressed had occurred for good reason, such as the question not being relevant to the family.[footnote 10]

Practitioner’s involvement in intervention allocation and informing families

Generally, both in autumn 2019 and winter 2020, practitioners were not included in the Gateway Team and provider discussions around which intervention would be most appropriate for the family that had been referred. However, there were a few instances of practitioners being involved in this discussion or being contacted by the Gateway Team or the provider for more background on the family or to gather their view on the type of intervention that would be most appropriate. As mentioned above, some practitioners felt that there should be a space on the RSQ for them to provide their professional opinion on a more systematic basis.

Families were usually told which intervention they had been referred to by the providers rather than the practitioners. Furthermore, practitioners were not told which interventions families had been allocated to unless they had been told directly by those families. However, practitioners were keen to know which interventions their families had been allocated to, how useful they were finding them and whether they had completed them, especially when they no longer had ongoing contact with those families. They felt this would motivate them to make referrals and help them to make more informed referrals in the future.

Providers’ experiences of referrals

When providers were asked, in the survey, about the levels of referrals they had received and whether this had met expectations, their experience varied considerably between interventions. Overall, providers felt interventions had received lower than expected referrals pre-March 2020 (i.e. before the coronavirus national lockdown), although this improved for over half of the interventions in the period between spring and winter 2020. The 4Rs 2Ss intervention had had no referrals by winter 2020, and although the survey responses only provide a snapshot of referrals rather than a full census, analysis of management information confirms there have been no referrals to it.

For Incredible Years Advanced and 4Rs 2Ss, referral rates were consistently below providers’ expectations, both before and after lockdown, which was attributed, in part, to the strict eligibility criteria of the interventions that ruled out some families. For Incredible Years Advanced, the age criteria of the children in the family was 4-12 and for 4Rs 2Ss, the family had to have a child aged 7-11 with a diagnosed behavioural issue. As parents had to complete the basic course for Incredible Years Advanced before they could take part in the advanced course, providers felt that the length of time needed to take part in both courses was a barrier for parents (i.e. 23 weeks for both basic and advanced courses). One provider suggested they should offer the advanced course as a standalone 9 week course to encourage more parents to join, and this has since been introduced.

For Family Check Up, providers attributed lower than expected referrals pre-March 2020 to it being a moderate intensity course when they felt parents were more likely to be signposted to high intensity courses. One provider suggested this might be because high intensity conflict is more obvious and therefore easier to identify in families than lower levels of conflict. Another reason may be that practitioners worked in services for people with multiple and complex needs. It should be noted that in 2020, providers were enabled to offer parents an alternative intensity intervention on the programme to the one which the RSQ indicated they were most suited to, if there were good reasons (such as logistics preventing participation in an intervention).

Another reason the providers gave for lower than expected referrals, specifically for Enhanced Triple P and Family Check Up was insufficient awareness of the interventions amongst practitioners, corresponding to the finding from practitioner interviews that understanding of the specific interventions was limited. One provider felt that referral staff were not fully aware of the full package of support that the Family Check Up course offered and, as a result, were not explaining it adequately to families. For Enhanced Triple P, some providers mentioned that the intervention was available both within and outside the RPC programme and this might be affecting referrals to programme provision.

Providers’ experiences of intervention delivery

Launching of provision

Whether interventions launched when originally planned varied; though only a handful of providers stated that they launched on time. Those launched on time were some of the Family Check Up courses, 2 Enhanced Triple P courses and a couple of Within My Reach courses. However, other providers offering these same interventions experienced delays to the launch date. A couple of interventions had not managed to launch at all by winter 2020. These included some Family Check Up courses and some of The Incredible Years Advanced courses. In addition, the 4Rs 2Ss Strengthening Programme was only being offered by one provider who, by winter 2020, was yet to receive any referrals.

The reasons given for delays to initial launch were most often lack of referrals or time taken to get enough referrals. However, in some cases, time taken to complete paperwork with local authorities and DWP and delays in access to training on the interventions for delivery staff caused the launching to be later than planned.

In terms of the availability of that [intervention] training, that’s been a struggle and has impacted on our capacity to deliver at times.

Provider

The national lockdown to tackle the coronavirus pandemic had a minimal impact on the roll-out and continuation of provision, with a significant proportion of interventions not pausing delivery at all during this period. For those who did pause provision, this happened in March 2020, but resumed very shortly after, either that same month, or in April 2020.

Contractual logistics and costs of delivery

A handful of providers expressed early concerns regarding the amount of paperwork, including data sharing agreements with DWP, other providers and local authorities, which they felt had contributed to some of the launch date delays.

The use of the RSQ and various other forms required to gather information from potential participants was also perceived as cumbersome to some providers.

It’s a programme with a lot of requirements and a lot of expectations. We need to make sure we fill out the right forms, submit the right forms through the right channels, at the right time. The whole process is very prescribed and monitored.

Provider

One provider of Enhanced Triple P suggested that an online referral process could help streamline the process. Linked to this, one provider praised the fact that DWP had moved to accept digital signatures, thereby reducing administrative burden.

A couple of providers mentioned the high cost of training delivery staff, particularly where there was a requirement for monthly supervision. However, despite this cost, the supervision approach was generally viewed positively.

It’s quite an involved supervision model; they have weekly supervision which is quite intense, then it drops down to fortnightly. The supervision is generally of a very good quality but it’s also quite expensive once it’s added up… the training is a five-day training [course], which again is quite expensive …but it is a therapy and that is expensive.

Provider

Delivery method

Prior to lockdown, the majority of providers delivered the interventions the way they were originally set out to be delivered. Table 2.2 below summarises the design of each intervention.

Table 2.2 Overview of intervention delivery models

| Intervention Name | Target group | Method of delivery | Length of delivery | Moderate / High |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| “4Rs 2Ss” Family Strengthening Programme | Both intact and separated couples with children aged 7-11 | Groups of 12-20 parents | 16 weeks | High |

| Family Check Up | Both intact and separated couples | Delivered to individual parents (either one or both parents) | 9 sessions of 50-60 minutes | Moderate |

| Enhanced Triple P | For both intact and separated couples | Delivered to individual parents (either one or both parents) | 4 modules delivered to families in 3 to 8 individualised consultations (8-12 hours) | High |

| Family Transitions Triple P | Separated couples only | Groups of approximately 8 parents (separated parents are encouraged to attend different sessions) | 5 sessions lasting 2 hours each | High |

| Mentalisation Based Therapy – Parenting Together | For both intact and separated couples | Two therapists deliver to the couple | 6-12 sessions of therapeutic work (usually spread over average of 16 weeks) | High |

| The Incredible Years, including Advanced Programme | Couples and separated co- parents with children aged 4-12 years | Group sessions of 12-20 parents | 12-20 sessions as part of the ‘basic’ course, with an additional 9-11 sessions for ‘advanced’ (up to 20 weeks) | High |

| Parents Plus Parenting when Separated Programme | Separated couples only | Group intervention delivered by 2 practitioners to groups of 12 participants | 6 week course of 2.5 hour sessions | Moderate |

| Within My Reach | Separated couples only | Delivered in a group to individuals (not couples) | 15 sessions, each lasting 1 hour | Moderate |

Before lockdown, a few providers mentioned some minor changes that were made to initial delivery:

- some Family Transitions Triple P providers delivered more sessions individually rather than in groups

- in Mentalisation Based Therapy, some providers made minor tweaks to the specifics of each session, for example, which parents were involved in each stage

- a couple of providers of The Incredible Years Advanced made certain modifications to the exact structure of completing basic and advanced. For example, one provider offered a 13-week advanced course, with a 4 week catch up on the basic course, and 9 weeks focused on advanced material

Setting of delivery

Some interventions were designed as group sessions and others one-to-one. Providers cited the benefits and drawbacks of each of these; for one-to-one interventions such as Family Check Up, Mentalisation Based Therapy and Enhanced Triple P, providers highlighted the ease of organising logistics when it is only one couple and one practitioner involved in the sessions. Conversely, the majority of providers offering group interventions encountered issues with filling group spaces and, pre-pandemic, finding an appropriate location for all parents in the same group to attend.

At an overall level, providers delivering group sessions highlighted that the group sharing element works well for parents, and those offering individual sessions felt these had benefits in terms of allowing time for self-reflection and more in-depth sharing.

Interventions were delivered in a range of settings:

- Family Check Up and Within My Reach were primarily in the home

- Family Transitions Triple P and Enhanced Triple P were in a mix of community venues and homes

- Mentalisation Based Therapy, Parents Plus Parenting When Separated and The Incredible Years Advanced were mainly in community venues

Changes in delivery due to lockdown

Since the lockdown period, all interventions had moved online to be delivered over Zoom or Teams. In in-depth interviews with providers, they mentioned that Mentalisation Based Therapy had translated particularly well to online delivery. They indicated that going forward, they would consider a move to blended delivery, even when social distancing guidelines allow service to resume as ‘normal’.

Moving to digital, out of all the interventions, it’s the one that has been most straightforward to move to online delivery because it only involves two parents and a practitioner… overall it has been the simplest to translate and can continue to be delivered digitally. I think moving forward we’ll probably offer a blended model.

Provider

In a handful of cases, delivery remains face-to-face, where exceptions are made due to either domestic abuse concerns or history or safe-guarding issues.

The changes in delivery have caused minimal issues, with the majority of providers in fact reporting that this has helped overcome logistical issues and increased attendance of parents. They expressed that it has been easier to find times that work for parents when they do not have to travel, and it has taken away the burden of organising a community setting that is within travelling distance of all participants. This has also meant that some interventions can be completed more quickly, with sessions closer together, which can in turn reduce drop-out rates.

Pre-lockdown, the intervention had to be completed within a 6-month period but since lockdown, we have managed to complete them within 3 months because we have been able to get hold of clients at agreed dates/times and complete the programme due to them being at home.

Provider

Meeting service provision requirements

In terms of adhering to service provision requirements, where delivery was in community venues, home location of participants was considered and community venues close to them were chosen. In addition, for all interventions, free childcare was offered either via providing access to a crèche at a community venue or by covering childcare costs. Where childcare costs were covered, this was sometimes by providing paid-for childminders or having an invoice for the childcare sent straight to the provider.

Content

Across the board, providers praised the content of the interventions:

- Family Check Up was described as having a positive tone with parents and being suitably gentle and easy for parents to engage with; the length was perceived to be manageable. One exercise in Family Check Up involves videoing parents for them to watch back and reflect upon. This received mixed feedback from providers; some felt that parents found it intrusive, though more often this was seen as a really useful part of the intervention

- Enhanced Triple P providers felt the content was clear and flexible, which can ensure it is relevant to the parents on each course. The delivery model ensures parents are engaged as they can build relationships with the practitioner. It was also praised for giving parents plenty of strategies they can use following the intervention