‘Ready or not’: care leavers’ views of preparing to leave care

Published 19 January 2022

Applies to England

Executive summary

For many children in care, approaching adulthood and leaving the care system is a time of extra challenges, anxiety and fear. This research looks at the planning and preparation that happens before leaving care.

We did an online survey of children in care (aged 16 to 17) and care leavers (no age limit) to explore whether the help they got when getting ready to leave care was what they needed, and how involved they were in the decisions made about their future. We also held interviews with a small number of people who left care a longer time ago, to get a view of what the impact of preparation (or lack of) has been on their lives after leaving care.

Our findings reflect what care leavers told us about their experiences through the survey and interviews. As people do not always recognise or accurately remember the help they get, our research can only report on care leavers’ perceptions of the preparation they received. Findings are not necessarily representative of all care leavers’ experiences. We have summarised some of the main findings in the section below, and expanded on them in the report.

Key findings

More than a third of care leavers felt that they left care too early. This was often because the move out of care happened abruptly and they were not ready for all the sudden changes. Of those who did feel that they left care at the right time, not all felt they had the required skills to live more independently. Many care leavers told us that they were not taught essential skills, such as how to shop, cook or manage money.

Many care leavers felt ‘alone’ or ‘isolated’ when they left care and did not know where to get help with their mental health or emotional well-being. Many care leavers had no one they could talk to about how they were feeling or who would look out for them. A third of care leavers told us they did not know where to get help and support. For many, no plans had been made to support their mental health or emotional well-being when they left care.

Although statutory guidance requires that young people should be introduced to their personal adviser (PA) from age 16, over a quarter of care leavers did not meet their PA until they were 18 or older. Care leavers saw PAs as helpful in preparing to leave care, but a fifth felt they met them too late. Two fifths of the children still in care told us that they did not yet have a PA, meaning that some about to leave care still did not know who would be helping them.

Some care leavers could not trust or rely on the professionals helping them to prepare for leaving care. Care leavers needed someone they could rely on for help when they felt scared or worried, but sometimes they felt that professionals were ‘rude’ or ‘uninterested’, or showed a lack of respect, for example by cancelling meetings, turning up late or ignoring their feelings.

Care leavers were not involved enough in plans about their future. Around a quarter of care leavers reported they were not at all involved in developing these plans. Some felt that, even when they expressed their wishes, they were not listened to, or that they did not fully understand the options. Some felt that plans did not match their aspirations. For many, this had a long-term impact on their education or career path, as well as their emotional well-being.

Many care leavers had no control over where they lived when they left care, and many felt unsafe. Only around a third of care leavers had a say in the location they’d like to live in and even fewer (a fifth) in the type of accommodation. One in 10 care leavers never felt safe when they first left care. Many care leavers were worried about the area or people where they lived. Sometimes the area was completely unfamiliar to them or was seen as a crime and exploitation hot spot. Many care leavers also felt unsafe living on their own.

Many care leavers felt unprepared to manage money. Some were not aware of what bills they needed to pay, or how to budget. In some cases, this led to them getting into debt, losing tenancies, or not being able to afford food or travel. Some care leavers were still in debt years later. When they were asked what made them feel unsafe when they first left care, being worried about money was the most common reason reported. A few care leavers reported getting into crime when they left care in order to get money, or because they were not able to manage their finances.

Some care leavers said they did not find out about their rights until they were already in serious difficulties. In some cases, care leavers were already in debt or homeless before they were told about the help they could access. Only around half remembered being told about the support and services available in the local care leaver offer. A similar proportion reported being told how to complain and even fewer were told how to get advocacy support. Care leavers (or their carers) who had engaged advocacy services had found this help to be vital.

Over the years, there has been more recognition of the importance of preparing care leavers to leave care. For example, the Children (Leaving Care) Act 2000 introduced further duties and additional functions for local authorities on top of the Children Act 1989.[footnote 1]

Despite this, some fairly simple things that could make a huge difference to care leavers’ experiences are still not always put in place. These include:

- telling care leavers about the available support

- helping them to stay in touch with important people

- working with them to ensure that they have the skills they need before moving on

This report brings out the voices of the care leavers who took part in our research and what they told us was particularly important to their experience of leaving care.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the care leavers who helped co-design our survey, and everyone who completed the survey, who spoke to us or who provided their details. We would also like to thank the professionals from Catch-22, and other care-experienced colleagues and organisations that advised us, helped facilitate contacts with care leavers and helped to pilot the survey.

Introduction

This report is part of a wider project looking at local authority decision-making for children in care, children on the edge of care and care leavers in England. We have previously reported on decisions involved when matching in foster care.[footnote 2] Our next report will look at sufficiency of accommodation for children in care and care leavers.

In England and Wales, the leaving care age is 18. At that age, children legally become an adult and any care order ends (although some children leave care at 16 or 17). Many young people who have spent time in care do not have the same opportunities as their peers, or the same level of ongoing support when they reach the age of 18 and beyond. Most young people who do not grow up in care are able to remain at home until they are ready for the next step (such as college, employment or moving in with friends or partners), but many care leavers have to move on before they would like and before they are ready.[footnote 3] Care leavers are legally entitled to ongoing support after they leave care, up to the age of 25.

Previous research has generally focused on outcomes for care leavers, such as educational attainment and where they live after care (including being homeless and spending time in custody).[footnote 4]There is less research with a specific focus on the preparation and planning for leaving care, how ready care leavers felt for independence and what involvement they had in developing plans for their life after care.

As an inspectorate of local authority children’s services, including services for care leavers, we wanted to hear directly from care leavers and children currently preparing to leave care. In particular, we were keen to hear how the professionals around care leavers (for example, carers, social workers, PAs and others) helped them plan and prepare for the transition to adulthood. We also wanted to find out how involved care leavers were in their plans for life after care – for example, did they have a choice in where they would live and did they have the opportunity to discuss any additional help they needed?

We wanted to find out whether this support was what those leaving care needed, so that our inspectors could use this information to focus on the things that are important to children when we inspect local authority services, children’s homes and others involved in preparing them for leaving care.

Finally, we wanted to find out what impact planning (or lack of planning) has on care leavers’ lives after they leave care and approach adulthood. For that reason, we included people who left care longer ago in our survey and interviews. This highlighted the importance of getting it right at an early stage, and ensuring that the correct planning and preparation are available, including when and how these are needed.

The research project

We wanted to answer the following research questions:

- What help do children get to prepare them for leaving care?

- How are children involved in decision-making and planning in preparation for leaving care?

- Does the help care leavers receive prepare them for leaving care?

- What are care leavers’ experiences of receiving and accessing the planned support since leaving care?

- How does care leavers’ identity affect their transition into adulthood?

We did this by running an online survey for children in care (aged 16 and over) and care leavers. The survey was run online because of the ongoing pandemic, but also so that we could reach more care leavers. Because completion of the survey was optional, findings may not be representative of all care leavers’ experiences.

We had 255 responses to our survey and most (89%) were from those aged 25 and under, so were either still in care or had left care fairly recently. Of the respondents:

- 57 (22%) were from children in care aged 16 or 17[footnote 5]

- 181 (71%) were from care leavers aged 16 to 34 (3 who left care aged 16 or 17, and 178 care leavers aged 18 to 34)

- 17 (7%) were from care leavers aged 35 and over

We also held in-depth follow-up interviews with 6 care-experienced people aged 26 and over.

Co-designing the research

To get the best possible perspective on care leavers’ experiences, we involved children in care (aged 16 and over) and care leavers in the design of the survey and other parts of the research. Working so closely with people who have first-hand experience of preparing to leave care is a key strength of this study and enhanced our own understanding.

We engaged small groups of care leavers through Catch-22 (a charity working with care leavers) and ran a number of virtual workshops. For further information on our approach to co-design, details about terminology used and strengths and limitations of the survey, see the methodology appendix.

The findings below relate to what care leavers told us through the survey questionnaire and interviews. We have not sought a professional view in this research as we wanted to explore care leavers’ experiences of the preparation they received and whether they felt it was what they needed. This is valuable in identifying how things can be improved for care leavers today.

What care leavers told us was important about preparing to leave care

Feeling ready

We asked care leavers whether they felt they left care at the right time. More than a third of care leavers felt they left too early.

Local authorities have a duty to support and prepare children in care for independence before they leave.[footnote 6] This includes allocating children to a PA, who will continue to work with them when they leave care. They also have to provide a range of financial and practical help (such as grants for setting up a new home, exemption from paying council tax, support with getting a driving licence, and help with job applications). This does vary by local area and, even with support, care leavers can feel like they are expected to become an adult overnight. As one respondent to our survey said, ‘You are treated like a child until you are 18 and suddenly you have a whole lot of responsibilities, yet your support is gone’.

Some young people told us about the lack of choice involved in the decision to leave care, for example saying they had to leave ‘whether we are ready or not’. This echoes previous research.[footnote 7] In some cases, options were limited by some practical considerations. As one care leaver told us: ‘For me, it was too early, but I had no other choice. It was either stay with my carers up [name of city] but was way too far from my college that was in [name of another city] so I ended up moving into a supported accommodation when I was 18.’

As well as a lack of choice, care leavers often felt that they were rushed into leaving care. For some, this made them feel that the local authority was ‘trying to get rid of’ them quickly. We heard some accounts from care leavers who, in the past, had to move with very little warning: ‘It was right up to me being 18 before I knew what was happening and I was really scared that I might lose my home’. This still seems to be the case for some children preparing to leave care now. As one child (aged 16 to 17) told us, ‘The local authority want to leave everything to the last 3 weeks and do it then, which surely will cause huge delays, especially when looking for housing’.

Research has highlighted that leaving care later and extending placements are protective factors for care leavers.[footnote 8] Although this is not always desirable or possible, both children in care and care leavers thought that more time was needed to help young people get used to leaving the care system.

For some people, leaving care was an exciting time. In these cases, it was usually their own choice to leave care, or they felt ready for the next stage, for example they were starting university. However, for some who chose to leave care, it was because they thought that leaving would be better than their current situation. One care leaver told us that ‘[…A] foster home would have been preferable, but trying to create a new family at that age did not really work. I was happy to be independent and away from that home.’

Some care leavers felt well supported in their decision to leave and were able to talk it through with the professionals helping them.

Learning essential skills

Even when care leavers felt they left care at the right time, not all of them felt that they had the skills they needed. This could be because the transition had been rushed, or because the focus was on some skills and not others, for example they had been taught how to cook and clean, but not how to manage money: ‘We do not have a choice whether we are ready or not… all I knew how to do was cook and clean did not know how to pay a single bill or the simplest of things.’

Financial preparation

Money was mentioned time and time again by the survey respondents, in relation to all aspects of leaving care (such as how ready they felt, where they lived and their safety). Although care leavers were often helped to access benefits or get money to set up their new homes, only two fifths of care leavers reported getting help to work out what bills and payments they needed to pay and when.

One care leaver told us they found themselves in financial difficulties a few months after leaving care and had to go and ask a nearby shopkeeper for help: ‘… I showed her this letter I got and it was a water bill, because I did not know what it was. She said “That’s a bill” and I said “What do I do with it?” and she said ”Well, you have to pay them”. And then it dawned on me: what other things have I not paid?’

Several people attributed money-related problems in later life to this lack of financial preparation: ‘I had little help in learning the financial side of things; I am in years of debt with council tax and water rates due to this’. Another told us, ‘I was taught to survive not thrive and I did not always survive; I lived on benefits for a long time and sometimes I had to steal or do illegal things to eat or put electricity on my meter’. Almost half of care leavers (47%) did not know how the money they received would change as they got older.

The picture was slightly more positive for 16- and 17-year-olds. The majority of those still in care mentioned that they were getting help with money skills. Although this included ‘talking about finances’, ‘being helped to understand the value of money’ and ‘budgeting’, not all care leavers felt confident that they knew how to manage money themselves. As one care leaver said, ‘I know about my care leaver benefits but not about how to spend it and I’m not very good with money so I would like more support in how to budget and things like that, so I don’t just waste it all’. However, we did hear several examples of the support care leavers were receiving to help with this.

The 2019 report by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on financial education for children in care highlighted the need to ensure that children in care are prepared to leave the care system confident about personal finance matters.[footnote 9] Recommendations included improving financial education in schools, providing more support for foster carers and improving local authority provision and government support (for example, by reducing PAs’ caseloads). Previous research has also indicated that care leavers want this support.[footnote 10]

Cooking, shopping and managing a household

As well as managing money, many care leavers told us they did not know how to cook, how to shop on a budget or how to access foodbanks when they needed it. One care experienced adult told us: ‘We did some basic bits and pieces in the kitchen at the home – fry an egg, make a cup of tea, you know. When I think about it, would I know how to put a meal together? No. It just was not taught.’

This was not the case for all care leavers though. Some told us about how they learned from their carers or other people where they lived. For one, the most useful preparation they had for leaving care was ‘… to watch others in my previous household do things that may become useful to me when I leave care and move to my own place’. For another, it was ‘practising essential independent living skills while living with foster carers – such as budgeting, making our own meals, tasks to complete around the house’.

Some of the care leavers we spoke to told us how living in care left them unprepared for the task of shopping, and even the shops themselves. A few care leavers told us that they had not been to a supermarket before. One care leaver said: ‘When I lived in the kids’ home, I never went to the supermarket… you just opened the fridge, and it was there’. Another care leaver told us the experience was overwhelming: ‘When I first left care, I could not do it. I was stunned at the size and the amount of people and just ran out.’

These are experiences that could be easily incorporated in children’s daily lives while in care, and especially when preparing to leave care. Children still in care gave us examples of how they had been prepared. One told us that the support they were getting included ‘independent living skills, shopping, cooking, cleaning, learning to use the washing machine’, and another said: ‘I have been cooking/shopping for nearly two years at the home’.

Providing the right kind of preparation could have a huge impact on young people as they left care and beyond: ‘My final residential home had a life skills booklet that made learning fun with photographic evidence that I still look back on today’.

Meeting a personal adviser

The Children (Leaving Care) Act 2000 states that children in care should be introduced to their PA from the age of 16, and the PA will then work alongside the social worker while they are in care, and take over as the child reaches 18.[footnote 11] However, only 30% of care leavers met their PAs at age 16 (or earlier), and another 30% met them aged 17. Around a quarter were aged 18 to 21. As a fifth of care leavers told us, this was too late.

We heard from several people who had already experienced debt or homelessness or been evicted from their homes before they were allocated to someone to help them understand how to manage bills, or tell them what help they were entitled to. One respondent told us that they did not have a PA ‘… until I was 20 and homeless. I had financial support from this service that helped me. However, I needed more emotional support. I had no support before this from social services.’

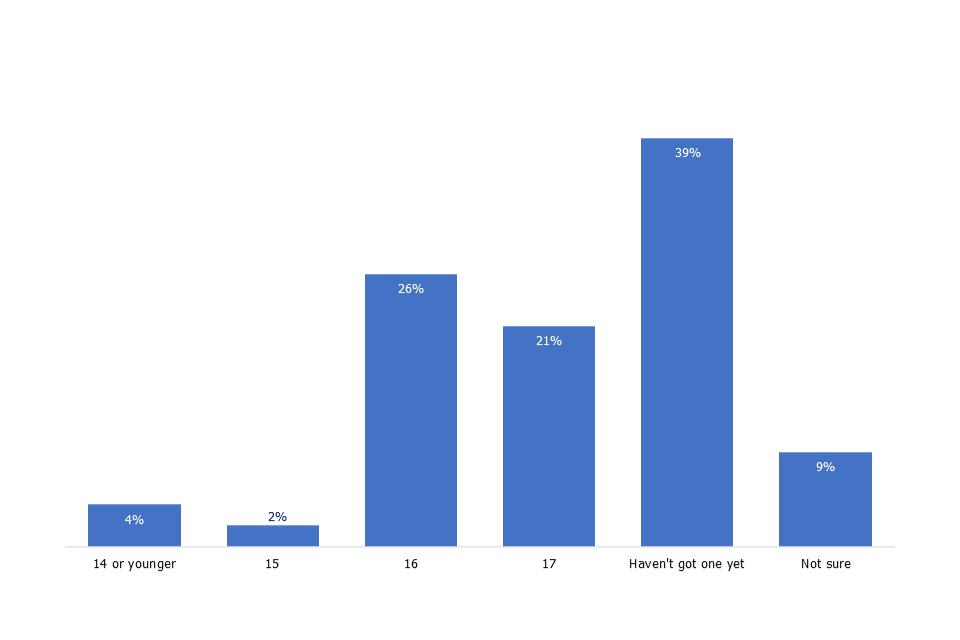

When asked whether various professionals were helpful in preparing them for leaving care, the majority of care leavers aged 16 to 34 (62%) felt that their PAs were helpful. Of those 16- and 17-year-olds still in care, 39% still did not have a PA and 21% only got one when they were 17.

Figure 1: How old were children currently in care when they first met their PA

Based on responses from 57 children in care (aged 16 to 17).

View data in an accessible table format.

Being involved in decisions and plans about their future

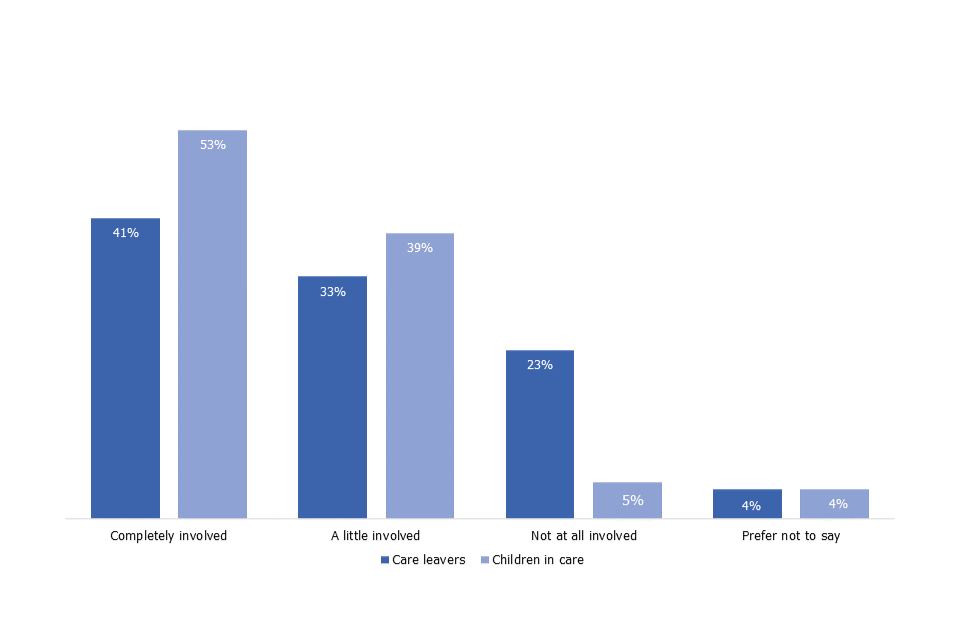

Almost a quarter (23%) of the care leavers responding to the survey told us that they did not feel at all involved in the plans and decisions that were made when they left care, and a third felt only ‘a little involved’. This echoes previous research findings.[footnote 12]

For children who were living in children’s homes immediately before leaving care, this was even higher. Almost half (47%) felt they were not at all involved in decisions about them. While this is based on a small number of respondents from children’s homes, there is indicative evidence of a relationship between living in a children’s home at the time of leaving care and not feeling involved in decision-making. Care leavers’ comments about this lack of involvement included not being able to have trusted adults or family members with them in meetings and reviews, and not having a say about where they wanted to live.

Figure 2: How involved children in care and care leavers felt in decisions and plans

Based on responses from 181 care leavers (aged 16 to 34) and 57 children in care (aged 16 to 17).

View data in an accessible table format.

Local authorities have a duty to ensure that all care leavers have a ‘pathway plan’. Wherever possible, this should be jointly prepared and agreed by the child and the authority. It should ‘set out a career path with milestones such as education, training, career plans, a planned date for leaving care and where and how [they] will live thereafter. It will set out the support which the local authority will provide at all stages of the plan, while [they are] being looked after and when [they] leave care and set up home independently’.[footnote 13] Research highlights that being involved in decisions about their future has positive impacts across all areas of young people’s lives.[footnote 14]

Many respondents told us that they did not have a pathway plan until they turned 18, and sometimes even older. For children still in care, there was a slightly more positive picture. Around half (53%) of the 16- and 17-year-olds still in care felt completely involved in the plans about their future, and only 5% felt not at all involved.[footnote 15]

Some of the children still in care mentioned the importance of having up-to-date plans, but said that these were not always prioritised. Several respondents told us they were uncertain about what was going to happen to them in the very short-term future, for example: ‘I only have 4 weeks left and I still do not know where I am going’. This had knock on effects for some in other areas of their life: ‘I would like to know where I will be living. This will help me look for a job in that area.’

We heard several examples of young people being housed a long distance from work or training. This poor planning meant that one had to get 3 buses to get to work each day, and another could not afford the train fare to get to college so was asked to leave because of poor attendance.

In some cases, care leavers believed the reason they were not involved in decisions and plans was because they were not trusted to know about their own lives. For one respondent, one of the worst things about the professionals helping them to prepare to leave care was social workers ‘… assuming I would not be able to handle situations’. Sometimes, the reverse was true: professionals believed that care leavers could cope by themselves, and so they were left to get on with things and were not offered the help that they needed. As one young person said, ‘[I] feel that because I have been doing this [handling things], professionals, especially during pathway plans, have just left me to it. Meanwhile my own well-being/mental health is in tatters and I have never felt so alone in decisions that other young people wouldn’t be alone in facing.’

Many care leavers talked about how professionals making decisions about their lives did not know them, or did not listen to their views. One care leaver summed it up: ‘… my views are never listened to and I feel I have to fight to be heard. And the people making decisions make it very clear, time and time again, that they do not even know me: they forget my name, my age, what my history is and my perspective, and they speak for me in front of me even though I disagree with them. So I just stopped bothering.’

This resonates with previous research that identified that children leaving care are more likely to participate and feel engaged in the planning process when they feel that their after-care worker knows and understands their personal needs. This is also more likely to result in greater levels of satisfaction with the planning and decision-making processes.[footnote 16] Professionals taking the time to build a trusting relationship with a child from the moment that they enter care subsequently helps support care leavers’ transition.[footnote 17]

We also heard a lot of examples of when PAs had really made a positive difference for care leavers. One told us: ‘Words cannot express how much support my PA has given me throughout the care-leaving process’. Many others said that they really valued their PA being there ‘without fail’, although one acknowledged that ‘…on the whole, my PA is great. Dead supportive. But she does not have a magic wand…’.

As well as involvement in plans, we also asked care leavers whether they were able to have who they wanted along to meetings and reviews to discuss their future. Two fifths (43%) of respondents reported that they did have a say in who was involved in discussions and meetings about their future. For 16- to 17-year-olds still in care, around two thirds (63%) told us that they always have a say in who attends meetings about them, but a third said this was only sometimes or not at all. One respondent told us: ‘Social workers tend to decide and don’t let me choose or have a voice on this matter’.

Where care leavers will live

Many care leavers who responded to our survey had no choice in where they would live. Fewer than half (46%) felt they had a choice in the type of accommodation and only around a third (35%) felt they had been given different options to choose from. Half said that they were not able to visit different places to help them decide where they wanted to live. Some had never seen their new accommodation until they moved in.

Many care leavers were not prepared for the accommodation or location they ended up living in. Some were living alone for the first time, or living with strangers, or living in an area they did not know or did not feel safe in.

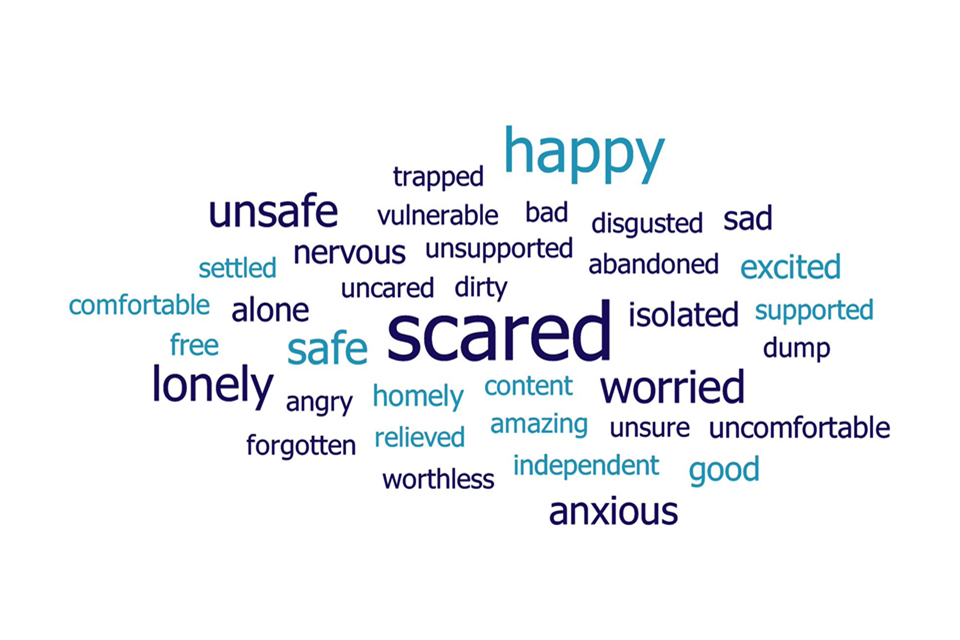

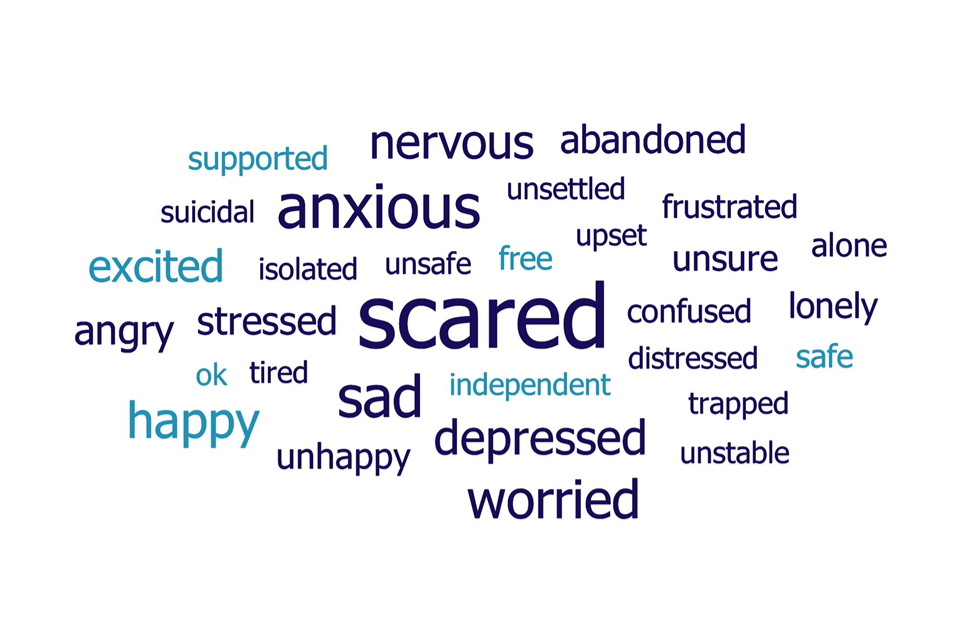

Care leavers’ views of how they felt about where they lived when they first left care were more negative than positive. The most common word used was ‘scared’, with ‘worried’, ‘unsafe’ and ‘lonely’ also appearing often. However, ‘happy’ was the second most used word, which illustrates the different feelings of some of the young people moving on from care.

Figure 3: Care leavers’ feelings about where they lived when they first left care

Based on responses from 75 care leavers (aged 16 to 34). Words only appear if used more than once.

View data in an accessible table format.

Of the children still in care who responded, around two thirds told us they were asked what kind of accommodation they would like (63%) and in what area they’d like to live (69%). However, only around half (48%) were asked what facilities or support they would need. This echoed real life experiences for care leavers (aged 18 to 34), a fifth of whom reported living in a home that did not have the accessibility adaptations or facilities that they needed, such as cooking or washing facilities.

Three of the 6 care leavers we interviewed mentioned being given black bin bags to pack their clothes in. Although this occurred less frequently in the younger age group, there were a few who had experienced it. One care leaver told us: ‘I wasn’t given support at all. I was given two bin bags, told to put my clothes in by the staff at the kids’ home, and then they took me to a youth hostel. Left me at 17. The social worker put me on benefits, then never saw me again.’

Many care leavers appreciated the support of professionals helping them to physically move their belongings into their new home. However, for some there was no further support or communication after this basic support. They reported feeling on their own and isolated.

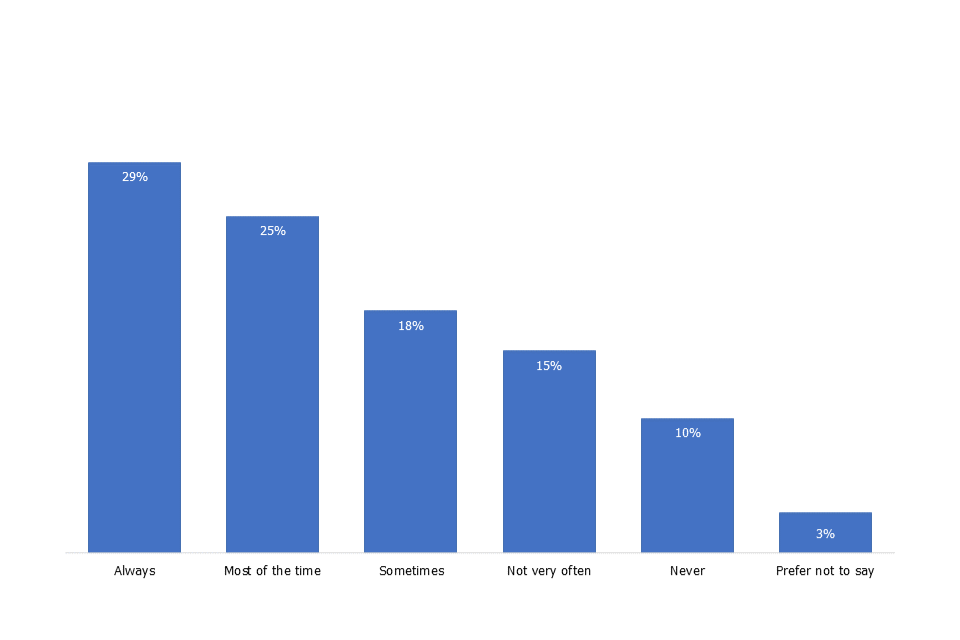

Feeling safe

We asked survey respondents whether they felt safe when they first left care. Only around half said they felt safe always or most of the time. Around a quarter rarely or never felt safe.

Figure 4: How often care leavers felt safe when they first left care

Based on responses from 146 care leavers (aged 16 to 34).

View data in an accessible table format.

The 3 most common reasons for not feeling safe were:

- issues relating to money (49%)

- the area where they lived (43%)

- living on their own (35%)

One of the care leavers we interviewed talked about their experience of leaving a children’s home and moving into a flat, alone, at age 16: ‘Walking home at night, you might have someone talk to you. You don’t know what they are trying to do. Going down a dark street to a flat made me nervous. I wasn’t part of the community; I didn’t know anyone, and I hadn’t been there before.’

Sometimes, fears about living alone or in unfamiliar or unsafe areas led to young people feeling pressured to make decisions that they did not want to make. This included reconnecting with family members who may have been a risk to them, moving in with abusive partners or engaging in criminal activity to gain money.

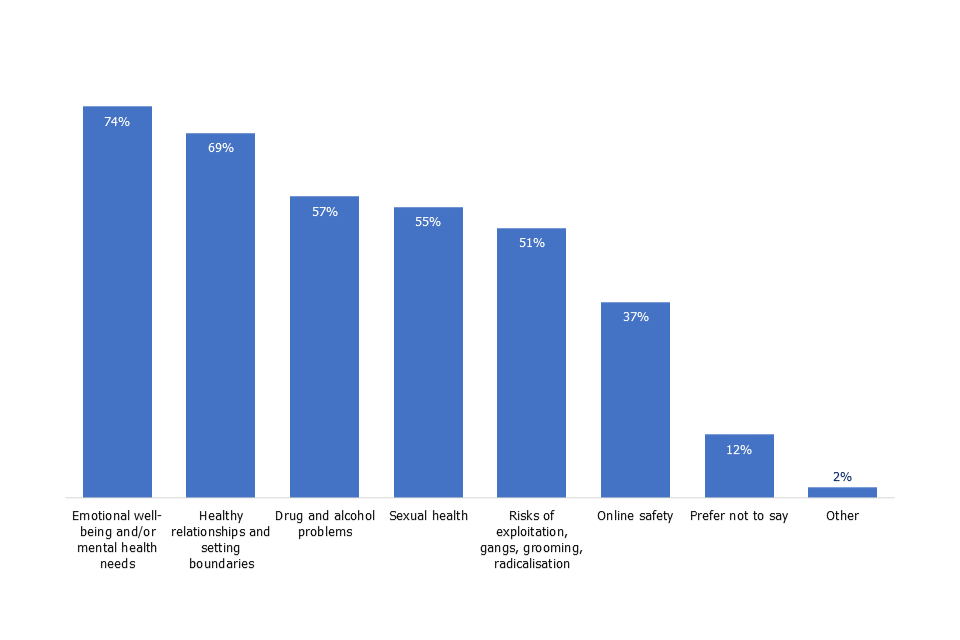

Fewer than half (45%) of care leavers said that someone had talked to them about their safety before leaving care. For those who did have discussions about safety, the most common topics were emotional well-being and mental health, and healthy relationships.

Figure 5: Topics of conversations about safety during care leavers’ preparation to leave care

Based on responses from 65 care leavers (aged 16 to 34). Respondents were able to tick one or more options from a list.

View data in an accessible table format.

Developing the local care leaver offer

Under the Children and Social Work Act (2017), local authorities have a duty to provide and publish a clear offer of support and financial assistance for care leavers once they leave the care of the local authority. This is known as the ‘Local offer for care leavers’ (or ‘care leaver offer’).[footnote 18] The Act specifies that the offer should be developed in consultation with relevant people (that is, care leavers and organisations that represent care leavers). Guidance states that local authorities are expected to co-produce ‘a local offer that is meaningful and reflects the needs, views and wishes of the care leavers they are responsible for’.

We asked children in care and care leavers what involvement they had in developing their local care leaver offer. Some respondents left care before the support was formalised through the Children (Leaving Care) Act 2000, which placed a duty on local authorities to provide support to care leavers until age 25. Despite this, only a quarter of both care leavers and children still in care reported being involved in developing plans in their local area.

Of the care leavers who felt they were not involved, two thirds reported that they were never offered the option to get involved. Some care leavers had been involved through their children in care council, care leavers forum and other groups (such as the National Leaving Care Benchmarking Forum). However, others had not heard about this being possible. One respondent told us: ‘I would love an opportunity to help shape the support care leavers receive in my area for the better. Social services have never made it known this is possible and again [this] shows how let down care leavers are by their local area as well as the government.’ One young person still in care said ‘I have asked to be involved and join my children in care council, but no one knows who runs it and this has caused huge delays’.

When young people had a chance to be involved in care leaver groups, they largely – though not consistently – found this helpful. We heard about some positive outcomes of involvement in these groups, including ‘… lots of opportunities to get involved in skill-building’ and the ability to ‘… get other people’s opinions, see what their point of view is, how they had gone through it’. Some specifically appreciated having a chance to help shape the care leaver offer. Care leaver involvement in developing the offer benefits the services in the area, as well as the care leavers themselves.

Care leavers had some good ideas about how more young people could be more involved in helping to develop plans for those leaving care. Often this was as simple as letting children in care and care leavers know that there was an opportunity there to be involved in such things: ‘Notify them of opportunities and benefits of attending, cover all expenses, send out regular opportunities to them to reiterate the service is there’. They also suggested highlighting the benefits of taking part to care leavers, such as meeting others, discussing their experiences, using their voice to shape the plans and being empowered.

Crucially, care leavers told us that it is important that professionals genuinely listen to them when they seek out feedback or when care leavers share ideas based on their experiences, ‘not just asking and not doing anything with it’.

Consideration of individuals’ identity in decision-making

We asked all respondents whether they felt that their identity had been considered in their plans for leaving care, for example their gender identity, sexual orientation, religion or ethnic group. This is important because it could affect whether the young person feels that they ‘fit in’ in their community or that it has the services they need, such as a place of worship. Only a third (33%) of respondents said that their identity had been considered.

While some care leavers gave us examples of how they felt that their identity and related needs had been considered and ‘… completely respected and taken into account by all parties’, others identified areas in which they would have liked this to be included in plans. For example, one care leaver said that they would have liked ‘support with cultural/ethnic needs that were too expensive or [I] couldn’t access for some time’.

Not all survey respondents felt that their sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, ethnicity or disability or any needs related to their identity had been relevant to their leaving care experience. One said: ‘What I was most concerned about was safe secure housing, not the above’. Others, on the contrary, felt that these parts of who they are were relevant to their leaving care experience, but some of them had not been asked. A respondent told us ‘this seemed to be a conversation they never wanted to have with me or didn’t know how [to]’.

Being supported through the process

Perhaps unsurprisingly, children in care and care leavers told us that the professionals themselves can make a real difference to their experience. Half of care leavers felt that social workers, PAs, foster carers or support workers were helpful.

We asked respondents to tell us what the best things were about the people helping them prepare to leave care. Young people frequently mentioned professionals being there when they needed them, and being able to rely on them. One respondent said: ‘I’ve always contacted my PA in times of great struggle and desperation, and she was there for me every single time without fail’. Care leavers also spoke about the impact that sensitive support can have on their emotional well-being: ‘Sometimes I feel stupid asking for help all the time, but she makes me feel comfortable and I can talk to her about anything’.

Care leavers also valued being listened to, people explaining things clearly to them and helping them to ‘… understand the steps that [were] going to be taken’. They also spoke about simply having ‘someone to talk to’ and being given advice that ‘helped [them] get prepared for the future’. For one respondent, one of the best things was that their ‘… foster carer sat me down and helped me to plan things out and showed me how to prepare myself for different situations’.

People also mentioned professionals’ personal attributes that made a difference to them. These included being ‘kind’, ‘patient’, ‘encouraging’, ‘non-judgemental’, ‘understanding’, ‘open’ and ‘funny’. Professionals being ‘relatable’ was an important aspect for some young people. A few young people mentioned professionals ‘loving’ them. As discussed above, it was also important to young people that they felt ‘involved’ in decisions, with one positive attribute mentioned being that the professional ‘let me take the lead’. Alongside this, young people mentioned ‘trust’ and the importance of professionals being ‘honest’. One said that ‘knowing people were reliable and that they would follow through with their word’ was one of the best things about the people supporting them in their leaving care experience.

Some of the ‘best’ things that children in care and care leavers highlighted were basic things that anyone should be able to expect from professionals, such as being ‘polite’, ‘on time’, ‘answering the phone’ and talking to them ‘with respect’. It is therefore interesting that when we asked respondents what was less helpful about the professionals who helped them prepare for leaving care, or what they would change, they said ‘being late’ and ‘cancelling meetings’ and that professionals were ‘unreliable’ or ‘unresponsive’. This highlights that care leavers just want professionals to treat them with respect.

Sadly, some young people experienced professionals who they felt were ‘rude’, ‘patronising’, ‘disinterested’, or had ‘no empathy’. One commented that ‘they often tell you how busy they are [and] what they cannot do’. These attitudes sometimes left young people feeling like they were ‘a burden’ to professionals who do not know them, who ‘made [them] feel insignificant’ and who they did not trust.

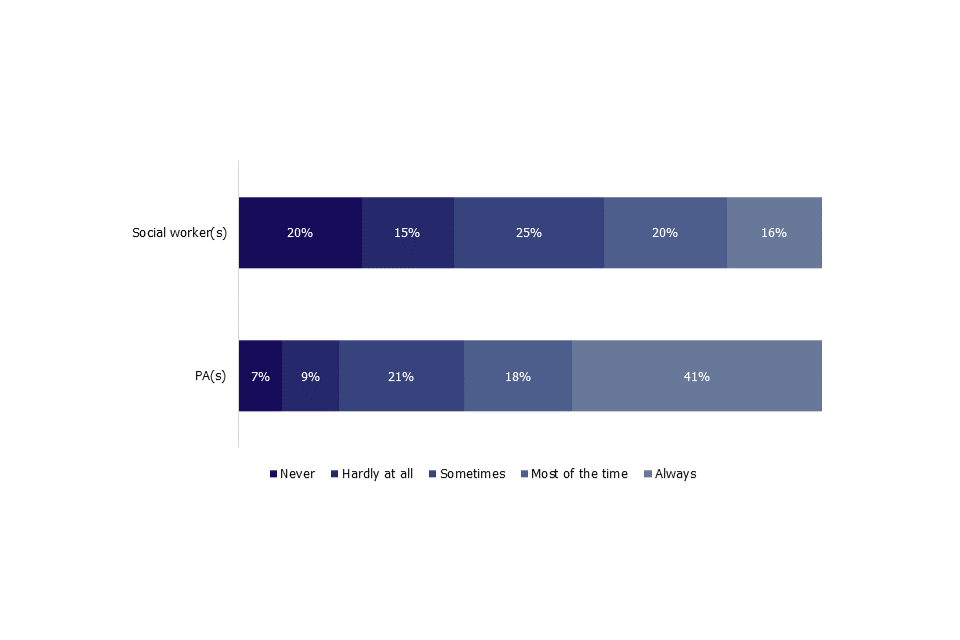

When we asked care leavers (aged 16 to 34) whether they felt cared for by their PAs and social workers, there was a clear difference in the responses:

- two fifths of care leavers (43%) felt that they were always cared for by their PA and less than a tenth (7%) said that they never felt cared for

- in contrast, less than a fifth (16%) reported that they always felt cared for by social workers, and a fifth (21%) never felt cared for

This may reflect that a PA is the person that young people are most commonly in touch with after they leave care. But it is striking that care leavers felt this lack of care from social workers, who have a responsibility to help coordinate plans for their future.

Children still in care were more likely to feel cared for by their social worker. Almost two thirds (37%) said they always felt cared for and 7% never felt cared for.

Figure 6: How often care leavers felt cared for by PAs and social workers

Based on responses from 179 care leavers (aged 16 to 34). ‘Prefer not to say’ responses are not displayed in this chart.

View data in an accessible table format.

Relationships with a key person they can trust are important for care leavers, especially when they need help.[footnote 19] However, some care leavers described how they felt that professionals involved in their lives were part of a bureaucratic system, referring to them as ‘politicians’, ‘only interested in money’, ‘ticking boxes’ and reducing them to ‘just a number’.

Relationships with those important to young people

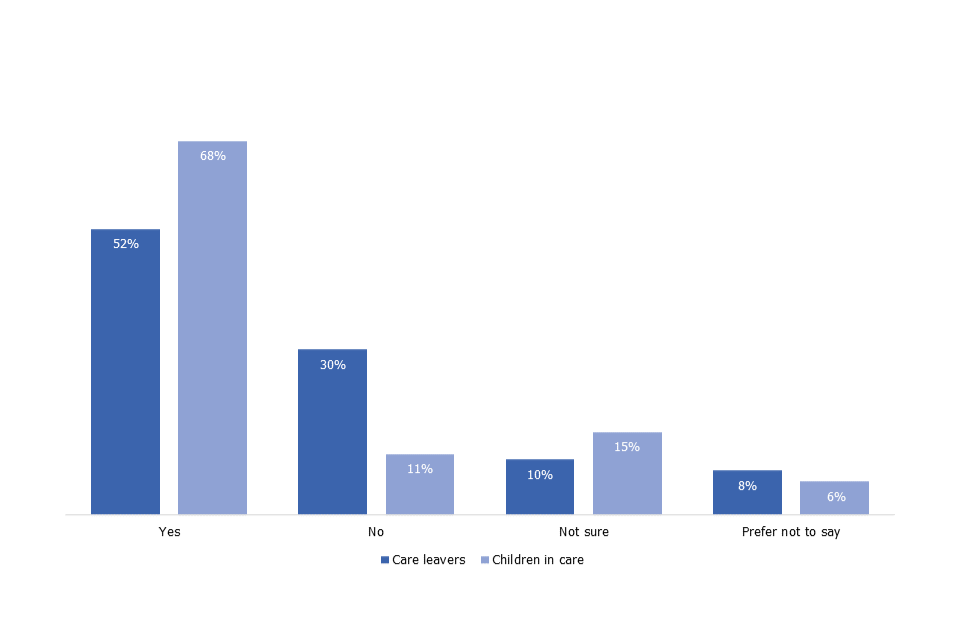

We asked all survey respondents whether they are, or were, helped to stay in touch with people important to them. These might be family members, friends, foster carers and so on. For children currently in care, two thirds (68%) said that their plans include staying in touch with people important to them and over half (52%) of care leavers aged 16 to 34 said that they were helped. The majority of care leavers aged 35 or over felt they were not helped to stay in touch with people important to them.

Figure 7: Whether young people felt they were supported to stay in touch with people important to them

Based on responses from 165 care leavers (aged 16 to 34) and 53 children in care (aged 16 to 17).

View data in an accessible table format.

Data for the different age groups suggests that there might have been progress in this area in recent years. More 16- to 17-year-olds still in care reported that they have been helped to stay in touch compared with those who had left care. However, this could also suggest that plans when children are still in care do not materialise once they have left care.

A few care leavers commented positively, for example: ‘My carer helped a lot and was supportive, along with my PA’ and ‘[My] social worker was brilliant with this’. However, a number of respondents detailed how they received no support to stay in touch with people. Many care leavers also felt that this was left up to them, for example commenting that ‘I did this myself’ or ‘not [a] single thing was done to help with this’. One care leaver told us about the consequences of not being helped to see important people: ‘I was often moved far away from family and friends and ended up feeling secluded. This resulted in me running away a lot from school, just to see those important to me.’

An older care leaver we interviewed told us that they reconnected with their brothers a little when leaving care, but this did not last:

I was the younger of three brothers… All three were fostered in separate foster placements and towns. We never grew up together. The only thing about care that affects me now in adult life is in relationships… Being torn apart from brothers was not a good start… I’ve not really had any contact ever. I saw them a bit when I was leaving care, but they had their own upbringing and problems… I would hope today that would be handled differently.

By contrast, there were situations when care leavers felt forced by circumstances or encouraged by professionals to look to their family for support, even though they had previously been seen as a risk to them or were a source of past trauma. These care leavers were understandably wary of reconnecting with their families: ‘… they just expect you to have a go on your own and go back to these family relationships. It’s like, you either have no one or you go back to those family relationships and I reckon it could be even more damaging.’ Another care-experienced adult had a similar experience: ‘… they just said “why don’t you visit your dad?” Well no; I was in care for a reason’.

Some care leavers, however, did have support from their family after leaving care. Many moved in with parents or brothers or sisters, or knew that they would be there if they needed help: ‘My family were around even if slightly emotionally distant; I knew I had them to fall back on if I needed them’. For other care leavers, the support came from their friends, including their friends’ families: ‘My best friend’s parents let me stay at their house when I felt unsafe in the semi-independent [accommodation]’.

Lasting relationships with professionals

Carers remained an important source of support for many care leavers. Some were able to continue to live with them in a ‘staying put’ arrangement, which gave them much welcomed security: ‘I felt safe enough to stay here as we have such a good bond and a good family relationship’. Although for many care leavers this is not a possibility, carers were an important source of support even for young people that had moved on.[footnote 20]

Care leavers also valued being able to stay in touch with social workers, children’s home staff and other professionals after they left care. For example, they told us that ‘… I absolutely adored [my social worker] and I am still in contact with [them] now’ and ‘My children’s home helped me the most; they still stay very close’.

To some care leavers, ongoing relationships indicated genuine care and that the worker or carer was going beyond just doing their job. Knowing that they had a place to go to, where they would be welcomed, was highlighted as being particularly important on significant occasions like birthdays, Christmas or even for Sunday dinner, when respondents felt that having people around them was particularly important. Some care leavers told us of being invited back for Christmas dinner, with professionals telling them: ‘You can come back [to the children’s home] and tell us how wonderful the world is… or tell us [if you] need some help’.

Having this ‘security’ of being able to go back to the home to visit friends and carers, and knowing they can talk to them, is important to care leavers and helps to ensure a smooth transition. However, we heard some examples of when promises that had been made to keep in contact did not materialise. For one care leaver, the home’s response when they made contact made them feel unwelcome, which was distressing and they did not try again: ‘They said if you need anything, give me a call. But it was non-existent. I went back a couple of times… I ended up within a hundred yards of the building and got a call saying “something has happened, you can’t come”. The next week: again. You could just feel the vibe…’

For some care leavers, relationships with social workers and children home’s staff ended with no notice, abruptly or without even saying goodbye. One care leaver told us that ‘there were so many social workers I lost track. They left without saying goodbye. I never saw the residential staff again after my last day at the children’s home.’

Not honouring assurances to keep in contact or provide ongoing support could sometimes have been beyond the control of the staff. However, the care leavers experienced rejection and felt that staff were not sensitive to how they felt, which could have a long-term impact on their emotional well-being.

Knowing how to get help

Support in an emergency

We asked care leavers aged 16 to 34 whether they were aware of how to get support in an emergency if they needed it. Almost half of respondents (44%) said that they did ‘in most situations’ or ‘always’, but a third (32%) of respondents said that they did not, or did not usually. A quarter (24%) of respondents said they had to find out on their own.

It is crucial for people to be able to get support in an emergency, including when this happens out of hours. Some people were unable to contact professionals when needed. One told us that ‘PAs work office hours, not around evenings, nights and weekends when you most want them’. As one young person commented, ‘Crisis is when professionals don’t work Friday evenings to Sunday’. Many care leavers felt that they had no support at all, let alone in an emergency. They had to rely on themselves and often felt isolated.

We also asked care leavers whether they knew where to go for help if they were short of money or getting into debt. Most (43%) did not. Only about a third (32%) said that they did, with another 17% saying that they sometimes did. Some people who had been in foster care said that they had access to financial support from their previous foster carers: ‘My ex foster carer supported me voluntarily’. Another care leaver who ‘stayed put’ said: ‘[I] was living with foster carers, so if I had money issues it wasn’t difficult to have help’.

Rights and advice

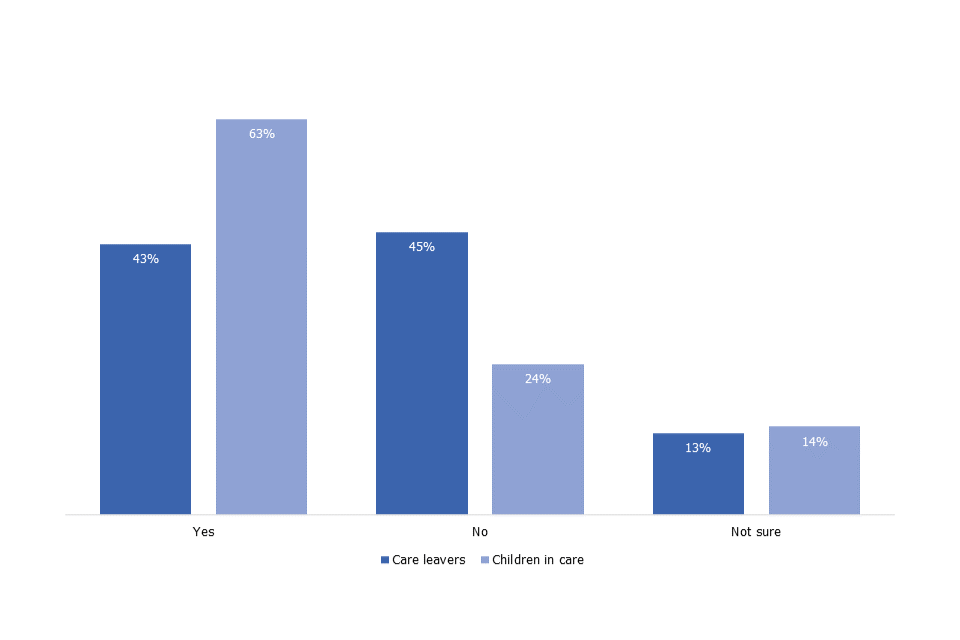

We asked children in care and care leavers aged 16 to 34 whether they knew about support that we would expect professionals to have made them aware of before leaving care, such as how to complain and access advocacy services.

Young people who were involved less in decisions about their future were also less likely to have been made aware of their rights and how to get help. Almost two thirds of children in care (63%) had been made aware of how to get advocacy support, but a quarter (24%) had not. Strikingly, almost half of care leavers (45%) were not made aware of how to get advocacy support. This raises concerns, especially because we heard from care leavers how helpful both formal and informal advocacy had been to them and their carers.

Figure 8: Proportion of children in care and care leavers who had been told how to access advocacy services

Based on responses from 144 care leavers (aged 16 to 34) and 51 children in care (aged 16 to 17).

View data in an accessible table format.

A number of care leavers told us that their foster carers advocated for them, or had organised for them to have a formal advocate. Others had received advocacy support from their independent visitor, or through charity organisations that support care leavers. Some received informal advocacy from people outside of the care system, in one example from a CEO from the company they worked for:

She was incredible and I couldn’t have got where I am now without her. I found myself homeless after joining university and she was the only person who […] gave me support, helped with university applications, even appealed/got her legal team involved when I didn’t receive a place.

Several care leavers spoke of the positive difference that advocacy had made, but some reported that they had had no access to an advocate and would have benefited from one: ‘Would have loved an advocate to help keep people accountable and to ensure that continual review actions actually got actioned’.

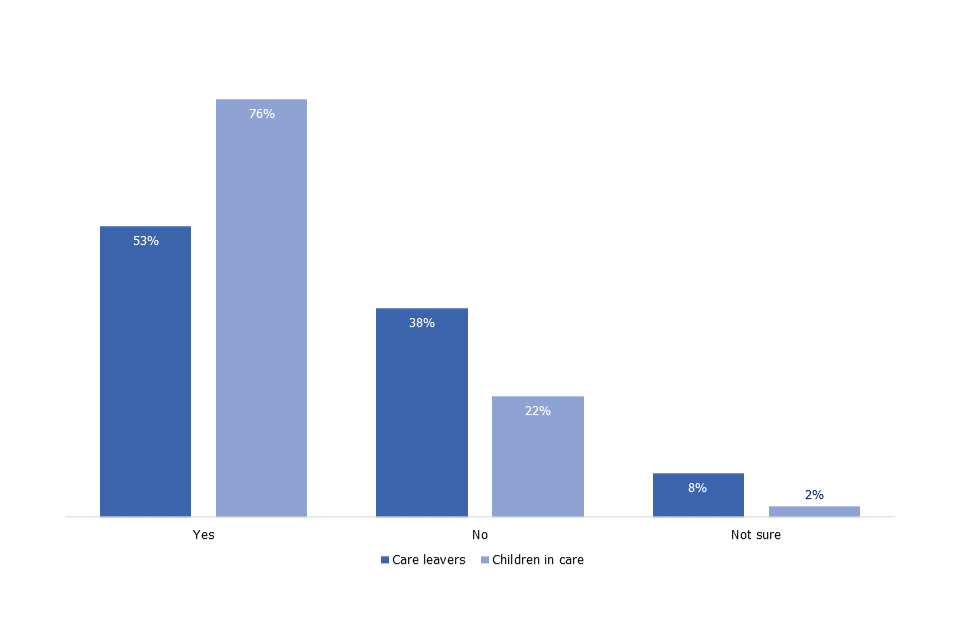

Over three quarters of children in care (76%) had been told how to complain. Over half of care leavers (53%) knew how to complain, but well over a third (38%) did not – despite many survey respondents discussing experiences that they were not happy about.

Figure 9: Proportion of respondents who were told how to complain

Based on responses from 144 care leavers (aged 16 to 34) and 51 children in care (aged 16 to 17).

View data in an accessible table format.

Only slightly more care leavers had been told how to access their records than had not (47% compared with 44%). Access to records has been highlighted as being vital to help care leavers ‘make sense of their past’ and answer questions about the reasons why they were in care.[footnote 21] However, even when care leavers were given access, not all were properly supported in the process. For example, one person we interviewed was left to go through their file alone as there was not a social worker available to support them, despite this being pre-arranged. Almost half of children in care (49%) had not been told how they could access their records when they turn 18 or in the future; only two fifths (41%) knew about this.

Only just over half (51%) of care leavers had been made aware of the support available for them in their local area (the care leaver offer). Almost two fifths (39%) had not, and another 10% were unsure. One care leaver told us: ‘I was not made aware of any council tax exemptions or support with education costs’. Another said that ‘there was no support. No numbers to contact. I was told I should have got a booklet and pack.’

Only a third (35%) of children in care had been made aware of the support available to them in their local area. Most children (43%) had not, and another quarter (22%) were unsure. A child who did not yet have a PA told us: ‘I would like more help and support from more people; I rely on my foster carers and would like more help from either a PA or someone else who knows more about what I can get’.

Being aware of available support is one thing, but young people should be helped to access the support and this should be aligned with receiving practical preparation, as discussed above.

Care leavers’ physical and emotional health

Corporate parents have a clear responsibility to provide support to help care leavers to have their health needs met. We asked care leavers whether they were told how to get help with their physical health, like registering with a GP and a dentist: 69% of care leavers (aged 16 to 34) said that they were, and 26% said they were not.

However, the responses also show that over a quarter of care leavers were not given help in this area. When care leavers talked about a lack of support, in many cases this was related to registering for and accessing healthcare. A young person told us they ‘still have no clue how to get into a dentist or opticians and have been out of care 10 months’. An older care leaver told us: ‘They had not even told me that I needed to change doctors. I was registered with a GP that was on the same road as the children’s home, but they moved me 10 miles out. So, when I rang the GP, they said “we can’t see you because you don’t live in our area. You need to re-register”’.

Some respondents noted that their options to remain healthy, for example by eating a balanced diet, were limited by not being taught the necessary skills or not having enough money: ‘On £44.50, it’s hard to eat. No one told me how to cook meals. It wasn’t important in the children’s home, so the habits weren’t instilled in me.’ An older care leaver said: ‘The children’s home aren’t worried about if you eat your carrots and peas. It’s just: don’t smash the plates over your heads.’

As well as skills and resources for healthy eating, care leavers highlighted the free access to gyms as part of care leaver offers as important in maintaining their health.

Care leavers’ mental health and emotional well-being

A third of care leavers were not told how to get help with their mental health or emotional well-being. One care leaver said, ‘Many of us know we need help. Many of us get told to ask for help, yet every time we ask for help, we get ignored.’

Others also highlighted the challenges in accessing support and having the information they needed without the perceived embarrassment of asking. One care leaver noted: ‘To get the right support is difficult. I have experienced trauma and need someone to help me to recognise when I need help because I don’t know.’

Even when care leavers knew where to turn for help, many were not provided with specialist support that was tailored to their traumatic experiences or in a timeframe that met their needs:

[Mental health service] said “have a bath”. I don’t think that really helps the crippling depression when I want to drown myself.

A further challenge for care leavers was transferring from children’s services to adult services, particularly the different support this means or the limited timescales available. A young adult told us:

I was referred to counselling after some months in crisis but this was not really suitable for young people who have experienced trauma… I needed time to build a relationship… I remember her once saying we have 7 weeks left. I’m not sure how a childhood of abuse could be solved within 9 weeks… It made me feel even worse.

An older care leaver told us:

I think lots of therapy helped, I realised at the age of 27 that I could either live the life that I’ve got, or I need to go and see someone. So, I went to see a therapist, and I think I was with her for about 10 years.

Current emotional well-being

We asked questions about respondents’ current levels of well-being in the survey using standardised questions on personal well-being developed by the Office for National Statistics.[footnote 22] While the sample was not representative of the care leaver population, respondents’ well-being scores were lower than the general population with more displaying low well-being. This is in line with what has been seen in previous research and suggests a long-term impact on well-being beyond leaving care.[footnote 23]

Some care leavers told of support they got from their PA when they experienced problems with their mental health or emotional well-being, while others told of the important role played by social workers, residential staff and those outside of the care sector, such as schools or places of work:

I had been moved right across to the other side of the city, so I wasn’t near anyone I knew. I was miles away from work, which was crazy. Work were good in that they then moved me to an office that was nearer to where I lived. And then I was really lucky – I had a really good manager, who came to me one day and said “I’m a bit concerned about you, you don’t look happy”. So, there were people but it was people outside of the system that were more readily noticing things.

There is indicative evidence of a link between care leavers being involved in decision-making and their current personal well-being. Those not at all involved have lower current well-being than those who were completely involved.[footnote 24] One care leaver said: ‘I had so many questions about what would happen… and yet nobody could answer. I felt fobbed off a lot of the time… I have never felt so alone in decisions that other young people wouldn’t be alone in facing.’ Eighty-five per cent of care leavers who felt completely involved in decision-making were told how to get help with their mental health or emotional well-being. They were also more likely to feel they left care at a time that felt right for them. Both of these factors may have impacted on their current well-being.

In our survey, more care leavers reported low well-being than children in care. A transition is a period of uncertainty and can lead to increased anxiety, especially for care leavers adjusting to new circumstances. We asked care leavers (aged 16 to 34) to describe in up to 3 words how they felt before they left care. The results show that a lot of care leavers felt scared, anxious, sad or worried. Others highlighted being isolated and alone, though several also felt happy or excited.

Figure 10: Care leavers’ feelings before they left care

Based on responses from 74 care leavers (aged 16 to 34). Words only appear if used more than once.

View data in an accessible table format.

For care leavers, the reported feelings were often made worse by a lack of supportive relationships and poor planning: ‘I felt so overwhelmed with the process of leaving care that it had a negative impact on my already poor mental health. I was poorly prepared for the transition…’

Care leavers also reported over-optimism from professionals when they appeared to be very independent. One told us: ‘I only… [saw my leaving care worker] once a year as he kept telling me how amazing I was doing. So [I] didn’t feel I could say how much I was struggling.’

Oversights in practical plans or a lack of resources had the potential to exacerbate pre-existing conditions for care leavers. Someone who had previously suffered from an eating disorder found themselves in financial difficulty soon after leaving care, which aggravated the disorder:

I’d been diagnosed… as being… anorexic, as a young teenager. So, it was vital that when I left care that there was enough resource for me to feed myself, because what happened was, I quickly went back into that not eating.

Another care leaver told us how they received some support from professionals when they first moved out but this stopped before they felt ready: ‘I remember them sleeping over a couple of times, because I was so scared to be alone at night. But I think that stopped when I still wasn’t ready to be alone at night, I was still scared…’

A third (32%) of care leavers told us that they did not have enough money for hobbies and leisure activities. Research shows that taking part in enjoyable activities can improve well-being.[footnote 25]

Identity as a ‘care leaver’

Many care leavers said that they were not comfortable telling people they had spent time in care. Some felt being labelled ‘a care leaver’ led to them being looked down on and treated differently: ‘There is a stigma attached to it…’. This could have a large impact on their emotional well-being.[footnote 26] One care leaver explained: ‘… I am ashamed of it. I want to be like everyone else.’

Some felt unable to answer questions about their past in personal relationships and so had to lie or leave out information. This affected their well-being as they felt they were ‘constantly lying’. One care experienced adult told us: ‘It has an impact as an adult as you have to put on a face and not be your authentic self’. One care leaver regretted not being more open about their situation: ‘I lost friendships over not telling people the truth… I wish I had told [them] from the beginning, as I lost a good friendship there’.

Care leavers’ expectations of how they are perceived sometimes prevented them asking for the help that they needed, or feeling that they were not listened to: ‘[A PA] basically discouraged me from going to university… I felt like if I said I’m struggling, they were going to be like “well maybe it’s not for you”, rather than “we’ll help you”.’ Others described how the fact that they spent time in care still cropped up into their 30s and 40s, such as being noted on medical records. They felt that the label ‘follows you around’.

Leaving care during the pandemic

Our fieldwork for this survey took place during the COVID-19 pandemic (July to September 2021), a time when services caring for children and helping prepare them for leaving care faced additional pressures due to staff absences, social isolation and restrictions. We therefore included a question in our survey to ask respondents whether they believe their experience of leaving (or preparing to leave) care had been affected by the pandemic.

Of the children in care who answered this question, responses were split between those who felt that COVID-19 did have an impact on their experience and those who felt it did not. Of the 16- to 34-year-olds who answered, about twice as many people said it did have an impact as those who said it did not.

When respondents mentioned an impact, this tended to be around not being able to see professionals, friends or family due to restrictions. Many mentioned their mental health or emotional well-being, especially in terms of feeling isolated. For example, one respondent said that they were ‘unable to see my PA as often as I would like and did not get to say goodbye to my previous social worker’. Others said it made them feel ‘the most alone ever’.

For both groups, another impact had been delay to their services or care: ‘It has slowed things down and made people a lot busier and therefore harder to help and inform’. One young person told us: ‘I haven’t got a PA yet. I don’t know if that is because of COVID though.’

Some felt that the situation left them with no help or support. However, although some reported a complete lack of available services, others appreciated workarounds put in place by professionals: ‘… [I] would like to see them more but due to current circumstances I understand this is not possible and enjoy having video calls with them’. One care leaver who said that COVID-19 did not have an impact on their experience felt that they ‘… could still ring [their] leaving care worker if I need help’, perhaps demonstrating the importance of having someone they could rely on to help them in difficult times.

For both recent care leavers and children currently preparing to leave care, COVID-19 was rarely mentioned outside of our direct question. In both age groups, we received responses that indicated a degree of frustration with the pandemic having been used as an excuse. One felt that ‘everything is blamed on COVID!’ while another said: ‘I feel professionals have used it as an excuse for sure, but I don’t think it’s a valid excuse’.

Conclusion

Whether leaving care is a time of optimism or a time of significant worry, it is often a stark contrast to the time children have spent in care. Children in care are usually surrounded by adults and other children. Although there may be difficulties within these relationships, there are often people around them, whether it is the foster carer having a chat before dinner, other children to hang out with or a member of residential staff logging children in and out of the children’s home. On leaving care, this social interaction is usually significantly reduced, and young people have to adapt to a new routine.

Our research has shown that, for many, leaving care is a frightening time. This is true for care leavers who have an ongoing relationship with, and access to support from, a foster carer or children’s home, but even more so for the many who do not. The title of this report, ‘Ready or not’, sums up care leavers’ experiences and the lack of choice that is a reality for many.

The transition to adult life

Leaving home and becoming an adult is daunting for anyone, but for many care leavers this means moving to a completely unfamiliar place or to live alone, and managing cooking, cleaning and budgeting for the first time, often with little support. Care leavers need a gradual transition and to be taught the skills they need to live independently. They need to be kept informed about the next steps, for example knowing the plan early enough to get used to it before they leave care.

Many young people reported feeling alone or isolated after they left care, but professionals did not always consider emotional well-being as part of leaving care plans. Professionals should recognise that not all children will need the same level of assistance, and some will need ongoing support after leaving care.

The role of the PA and other professionals

Although statutory guidance requires that children meet their PA from age 16, our research suggests that many care leavers do not meet them until they are 18 or older. This is too late and means they may miss out on support, for example with managing money.

Even when care leavers did have an allocated PA, or someone else helping them get ready to leave care, not all of them felt they could trust or rely on the professionals helping them. Sometimes this is because they felt that attitudes towards them were unprofessional.

Care leavers need PAs and social workers who know them well so that the type and amount of support they receive matches their needs. This can lead to care leavers receiving the help that they need and to them feeling better prepared and more involved in decisions about their future.

Planning for education and employment

Care leavers were not always involved enough in plans for their lives after care, and some said that they were not involved at all. Professionals need to start planning early with the young person for their life after care. Plans should incorporate housing, work, education, relationships and social life (including sports, leisure activities, volunteering and so on) and these should be considered together to ensure that they are sustainable.

It might not be possible to meet all of a young person’s wishes, but involving them in developing their plan can increase their understanding of the decision-making process and allow them to make their priorities known. When care leavers are not involved in decisions about their futures, it can have a negative impact on their emotional well-being and/or financial situation, sometimes long-term.

In order to make the biggest difference to people leaving care now, one care leaver told us: ‘I do think, it’s as simple as actually listening to the young person sometimes!’

Accommodation and safety

Many care leavers felt they had no control over where they lived when they leave care. They are often worried about the area where they lived, which could be completely new to them, or familiar but unsafe, for example because of drug and alcohol issues. They sometimes felt particularly vulnerable because they are not near any of their support network or because they are living alone.

Professionals should involve care leavers in developing their plans for where they will live after care, including by understanding their concerns about safety and identifying any possible consequences. Care leavers should have a say in the area and type of accommodation they move to and should be able to visit before they move there.

Having conversations about safety with young people when they leave care will increase their confidence and knowledge of how to get help if needed, and reduce the risk of them feeling scared.

Money and budgeting

Worries about money could be a major concern for young people when they first leave care. Some care leavers were unprepared to manage money and did not have even a basic understanding of what bills they had to pay or how to budget. A lack of money or lack of awareness of how to manage money can lead to anxiety as they try to deal with this for the first time. It can also lead to young people getting into debt, losing tenancies or not having enough money for food or travel. Some experience long-lasting debt problems.

Care leavers need financial support in terms of handling their finances and accessing more funding. Children in care need to be helped to understand their finances as they start preparing to leave care, so that they are confident in managing money themselves. They also need to be helped to understand what financial support is available, what they are entitled to and where to go for help when they need it. Lack of financial knowledge has a negative impact on care leavers’ mental health or emotional well-being.

Rights and entitlements

Too many care leavers were not told about the support and financial entitlements available to them through the care leaver offer. Some said they were already in debt or homeless before they found out.

Other information about care leavers’ rights and entitlements is also not always shared as part of standard practice, leaving many in the dark. Knowing how to complain, how to get advocacy support and how to access their records is important. This should form a key part of conversations with young people as they approach the end of their time in care and beyond. In many cases, knowing about their rights to financial help and advocacy and other support earlier could have made a huge difference to their situations.

Recommendations

The sections below show what care leavers told us they think Ofsted should be doing, as well as next steps for Ofsted and our recommendations to corporate parents.

Messages for Ofsted

We asked care leavers what they would like Ofsted to understand about their experience of leaving care as part of our work and inspections. They suggested the following:

- Make enough time to talk to care leavers on inspection by ensuring that dedicated time is built into the inspection timetable.

- Speak to enough care leavers directly at random during inspection to ensure that you can capture a true, unbiased view of their experiences.

- Take enough account of care leavers’ views and improve communication with young people about actions taken after inspections.

- Ensure that Ofsted looks at the complaints that are made by care leavers about their service.

- Have enough of a focus on access to records on inspection, including finding out whether children in care and care leavers are told they can access them at age 18, and how well they are supported to do so.

Next steps for Ofsted

The messages for Ofsted and the overall survey findings reinforce how important it is that our inspections consistently focus on the things that matter most to children in care and care leavers. We have highlighted how professionals do not always communicate and involve children in decision-making well enough. At Ofsted, we want to continue communicating with care leavers to ensure that our inspections capture what it is really like for care leavers in a particular area.

This research has already influenced training we held for inspectors in 2021.

We will work closely in the coming months with stakeholders (and, in particular, care leavers) to look at:

- how effectively our inspections of local authority children’s services (ILACS)[footnote 27] capture and report on the experiences and progress of care leavers

- what improvements can be made to our inspections

We will also continue to carry out our focused visits that look at the experiences of children in care and care leavers during 2022.[footnote 28] The messages from this research will help to plan these visits and we will publish a summary report afterwards.

Our findings from this research have been shared with the team leading the Care Review.[footnote 29]

Recommendations for corporate parents

Many of the findings highlighted in this research are not new and are related to existing statutory guidance. However, the fact that many children in care and care leavers, including those who left many years ago, continue to share similar experiences and feelings about the preparation they got for leaving care shows that there is more that corporate parents could do to satisfy themselves that they are meeting their duties under the Children (Leaving Care) Act 2000.

We have the following recommendations for corporate parents:

- Allocate children in care to a PA as close to age 16 as possible, in line with statutory guidance.

- Involve children in care and care leavers in developing their plans for after care. Plans should take account of young people’s wishes and concerns, when possible, including those related to feeling safe, where young people want to live, and what they want to do with their future.

- Plans should pay sufficient attention to social, emotional and mental health needs. They should be developed early but at the young person’s pace and in an incremental way.

- Young people should be prepared for:

- managing finances and budgeting, including understanding what bills they have to pay, what benefits they are entitled to, how to budget, and how the money they get will change at different ages

- handling safety and risk, including about the area and accommodation they live in, what risks they may face, ensuring they know who they can call for help, and what they can do in an emergency

- accessing health services, including helping them to register with GPs, dentists and opticians, and ensuring that they know what services are available if they move area

- supporting mental health and emotional well-being, including knowing who they can call if they need help or someone to talk to (any known mental health problems should be incorporated into the plan so that these are considered across all aspects of planning). If care leavers have long-term physical or mental health conditions, corporate parents should help them to navigate the transition to adults’ services.

- Publish and publicise the local authority’s care leaver offer in accessible ways, in line with statutory guidance. Ensure that care leavers know what they are legally entitled to and are helped to access support after they leave care. Review the care leaver offer in partnership with care leavers.

- Ensure that all children in care and care leavers know how to make a complaint and have access to advocacy services.

Methodology appendix

This research project comprised of:

- an online survey for children in care (aged 16 and over) and care leavers

- in-depth interviews with 6 care-experienced adults aged 26 and over

Co-designing the research

We chose to co-design the research with care leavers. We wanted to make sure our survey asked care leavers about the things that really mattered to them, and that the questions and research tools were as accessible and engaging as possible.

To do this, we engaged small groups of care leavers through Catch-22 (a charity working with care leavers) and ran some virtual workshops. The first workshop helped us understand the issues that children in care and care leavers considered the most important when leaving care and what we should focus our survey on. Importantly, we were also able to discuss with them how best to refer to the process of leaving care (‘leaving care’ or ‘moving on’) and whether in our survey we should use the term care leaver, care experienced person, or another term. Although there were lots of different views on this, care leaver was the term that most of the people we spoke to identified with.

Further workshops allowed us to run draft questions by them and get feedback on whether we asked the right things, whether the format of the questions worked and whether we used the right language. The care leavers gave us valuable input about what to ask and how questions should be worded, or made to look more interesting, for example by using pictures and emojis. They also gave us ideas on how to improve the response rate.

Engaging with young people ensured that the research project reflected their insights, which in turn enabled the research tools to be more accessible to other children in care and care leavers.

Online survey

Data collection took place between July and September 2021. The survey was primarily cascaded through stakeholder organisations and using social media. We also encouraged local authorities to share the survey with relevant teams.