Police Uplift Programme New Recruits Onboarding Survey 2021 – Report

Published 31 August 2022

Applies to England and Wales

Authors: Police and Fire Analysis Unit, Home Office Analysis & Insight (HOAI)

Press Enquiries: pressoffice@homeoffice.gov.uk

1. Background

On 5 September 2019, the Prime Minister announced the government’s commitment to recruit an additional 20,000 police officers in England and Wales by 31 March 2023. The Police Uplift Programme (PUP) launched in October 2019, with progress towards the 20,000 target tracked regularly through Home Office statistical publications.

Alongside the high levels of recruitment that are critical to delivering this programme, a key objective of PUP is to retain newly recruited police officers at high levels. In response to this objective, the Home Office launched the 2021 PUP New Recruits Onboarding Survey to improve understanding of the retention of new officers.

The primary aims of the survey were:

- to provide insight into the views and experiences of new officers, including how satisfied they felt about their police career, and whether they intended to remain in policing

- to better understand the new joiners’ onboarding process, including recruitment, training, management, support and wellbeing

- to identify how views and opinions vary across sub-groups of interest (including gender, ethnicity, age, length of service and entry route), and collect richer information on the backgrounds of new joiners

Research teams at the Home Office and College of Policing jointly designed and administered the survey, with input from the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) PUP Management Team. This joint approach enabled Home Office and College of Policing objectives to be met within a single survey, thereby minimising the burden placed upon police forces. Besides some areas of shared interest, each organisation led on analysing the survey findings specific to their objectives.

This report explores the themes analysed by the Home Office analysis team. The College of Policing will report in due course on themes not covered in this report, including police education and training, evidence-based policing and problem solving.

The survey will be repeated in 2022 to allow for year-on-year tracking of the results.

2. Methodology

The 2021 PUP New Recruits Onboarding Survey took place during March and April 2021. The survey was conducted online, with 10,206 new police officers from all 43 police forces invited to take part. A total of 3,462 responses were received, representing a 34% response rate.

2.1 Eligibility

The survey focussed on understanding the experiences of new police officers during their first year in the role. Any new officer, excluding transferees[footnote 1], that joined their force between February and November 2020 was eligible to take part in the survey. These parameters meant that at the launch of the survey in March 2021, all eligible participants were recruited during PUP and would have between 3 to 12 months’ experience in the role. A minimum tenure of at least three months ensured that all participants could draw upon some experience of operational deployment.

2.2 Sampling

Home Office statistical publications on PUP provided a guide as to the eligible sample size for this survey. Figures published on 28 January 2021 indicated that during the eligible period from February to November 2020, 11,382 new police officers had been recruited across England and Wales (see Table U4). This represented the maximum potential sample size. This figure was expected to drop slightly when samples were prepared, as not all officers recruited during this period would still be in post at the time of sampling.

Considering the size of the available sample and with a target response rate for the survey of at least 30%, all eligible participants were invited to take part. Successfully achieving this response rate would deliver an achieved sample size above 3,000, which would be sufficient for analysis across a range of sub-groups. This approach had the added benefit of ensuring that a sampling process was not required, and all eligible participants would have equal opportunity to participate in the survey.

As all eligible participants were invited to take part by email, the sampling process consisted only of collating a list of work email addresses for eligible officers in each police force. A single point of contact (SPOC) was established within each of the 43 police forces, typically a member of the Learning & Development team, who would liaise with the Home Office and College of Policing on the sampling and other aspects of delivering the survey. The research team provided SPOCs in every force with instructions on preparing a sample of email addresses. This sample always remained within the force to protect the anonymity of eligible officers. They only shared the total eligible sample size for each force with the Home Office and College of Policing. This total figure would enable response rates to be calculated during the fieldwork period.

After preparing all force samples, the total eligible sample size for the survey was 10,206 officers.

2.3 Questionnaire design and scripting

Researchers from the Home Office and College of Policing jointly designed the survey questionnaire. Stakeholders from the Home Office, College of Policing and NPCC were consulted throughout the development process. The questionnaire was designed to take no longer than 15 minutes to complete, to limit the chance of participants dropping out due to time concerns or survey fatigue. To guarantee that the completion time remained within 15 minutes for all, some questions were routed into two modules within the questionnaire, each answered by only 50% of the sample.

The questionnaire included several standard demographic questions, but it did not collect any officer names or contact details. Full anonymity was provided to participants to hopefully increase the number of responses and encourage honest feedback.

The agreed questionnaire was scripted into a short online survey hosted via the Smart Survey platform. The research team tested the script thoroughly ahead of the survey launch to ensure accuracy in the set-up.

2.4 Data collection

Soft launch pilot

Prior to the full survey launch, the research team undertook a short soft launch to ensure the survey infrastructure was working as expected. During the soft launch, survey invitations were issued to approximately 5% of the overall sample. The main aims of the soft launch were:

- to ensure that the email invitation system worked as expected and eligible participants received emails

- to confirm that participants could enter the survey and complete a response

- to confirm the survey script routing was working correctly

The research team corrected any issues identified during the soft launch before the full launch of the survey to all eligible police officers in England and Wales.

Main fieldwork period

The full survey launch took place on 23 March 2021. SPOCs from all police forces sent invitations to the eligible participants in their sample by email, including a link to follow to complete the survey. The main fieldwork period continued for four weeks after the first email invitations were sent. All eligible participants received a reminder email one week after the full launch, with a further reminder sent a week after that. The survey closing date was set for two weeks after the second reminder, on 22 April 2022, to give time for final completions. Where necessary, a third reminder was sent to increase response in a few forces.

At the close of fieldwork, a total of 3,462 responses had been received, representing an overall response rate of 34%.

2.5 Data cleaning

Following the completion of survey fieldwork, a data cleaning stage took place to ensure full confidence in the survey data before analysis got underway.

Despite efforts through the questionnaire design to minimise the survey dropout rate, there were still some incomplete responses. The research team removed all partially completed responses from the dataset before the analysis stage. A small number of fully complete responses were also removed from the data, either due to participants providing a start date which fell outside of the eligible period of February to November 2020, or indicating that they were a transferee into their force and therefore not new to policing.

The survey questionnaire included several questions which contained an ‘Other’ category, which invited participants to type in free text responses if their answer was not present on the closed response list. The research team reviewed all these responses, and created additional closed answer categories for free text answers that came up regularly to ensure the analysis captured these responses.

2.6 Survey weighting

Home Office Police Uplift statistics provide information on the profile of new police officers recruited during 2020 for two demographic variables – gender and ethnicity (see tables U7 and U8). This created the opportunity, as is standard on surveys of this nature, to complete some basic demographic survey weighting to correct for minor imbalances in the achieved sample. Although the achieved sample closely matched the known demographic profile of new police officers, the research team applied weights on both gender and ethnicity. This ensured that the achieved sample reflected the profile of the full eligible sample. The impact of these weights on the sample is outlined below.

Gender weights

| Unweighted % of sample | Weighted % of sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 58.1% | 59.6% |

| Female | 41.1% | 39.6% |

| Prefer to self-describe | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| Prefer not to say | 0.8% | 0.7% |

Ethnicity weights

| Unweighted % of sample | Weighted % of sample | |

|---|---|---|

| White | 92.0% | 88.7% |

| Black, Asian & Minority Ethnic | 7.0% | 10.2% |

| Prefer not to say | 1.0% | 1.1% |

Weighting was also applied at police force level, to account for differential response rates between them. This made sure that responses from each force were in proportion to the size of their PUP intake.

The final weighted sample had a weighting efficiency of 90.2%.

3. Headline findings

The PUP New Recruits Onboarding Survey (2021) found a positive onboarding experience overall for new police recruits across England and Wales. Most new officers indicated the role met or exceeded their expectations. Satisfaction with the job itself, and the support provided by line managers and tutor constables, was also high. There were also encouraging findings regarding new officer retention, as more than eight in ten new officers indicated they intend to stay in the service until retirement or pension age.

The findings also raise some challenges for policing. They highlight that while the experiences of new officers from ethnic minority backgrounds were positive overall, they were less positive than those of their white colleagues. There are also challenges to consider around new officer wellbeing, as one in four reported ignoring their personal life needs due to work strain, while one in three agreed that tension and stress from work adversely affect the rest of their life.

Headline survey findings at national level are outlined in the details that follow. Where differences between sub-groups were found to be statistically significant, additional information has been provided.

3.1 Job satisfaction

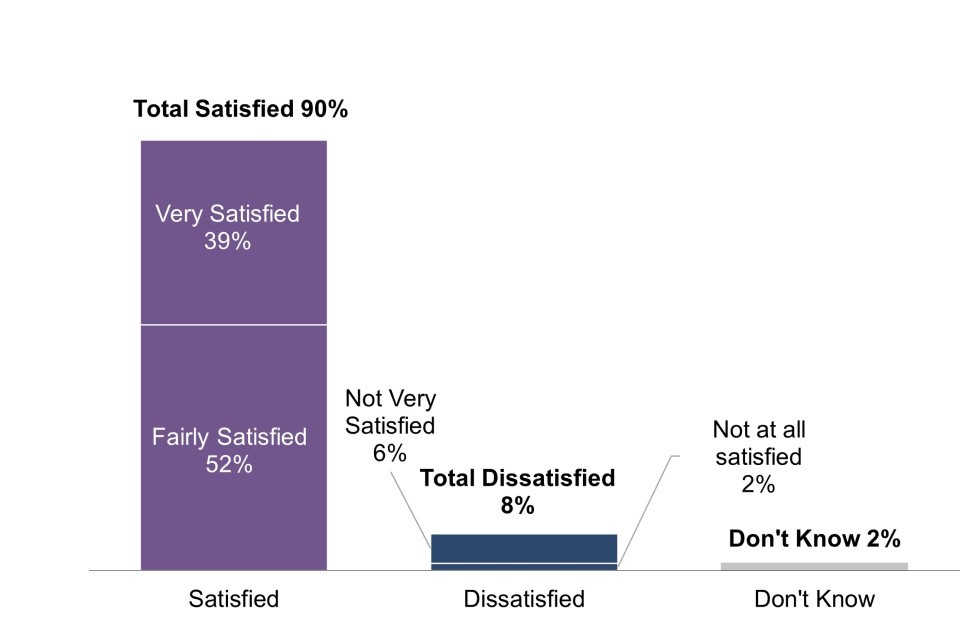

When asked how satisfied new recruits were with their job as a police officer, more than nine in ten indicated that they were satisfied; 52% selected that they were ‘Fairly Satisfied’ and 39% that they were ‘Very Satisfied’. Only 2% of recruits indicated they were ‘Not at all satisfied’ with their job.

Figure 1: Chart showing the level of satisfaction of new police recruits

Q38. Overall, how satisfied are you with your job as a police officer?

Base: Total respondents to this question: (1,842)

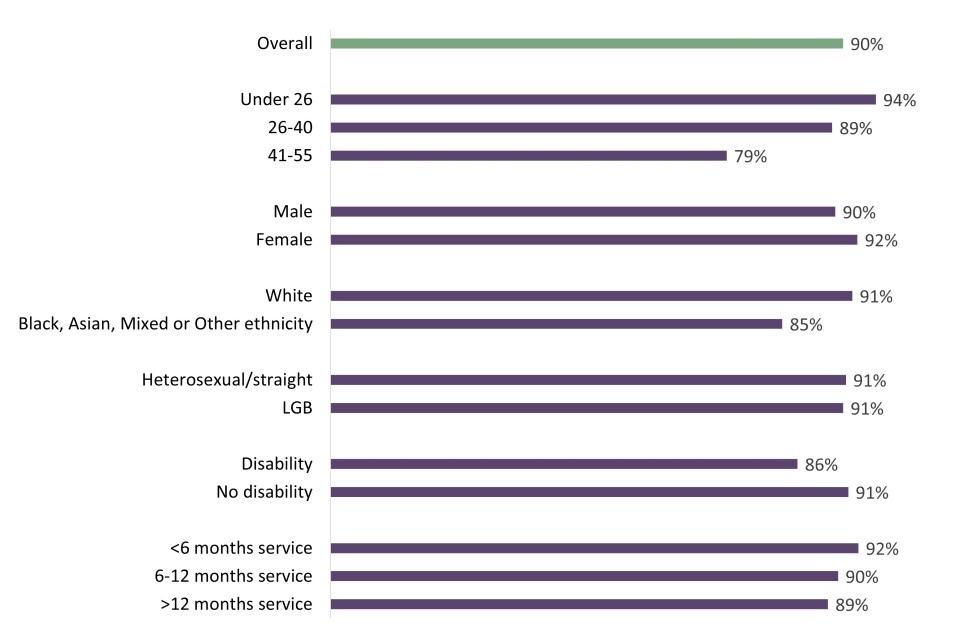

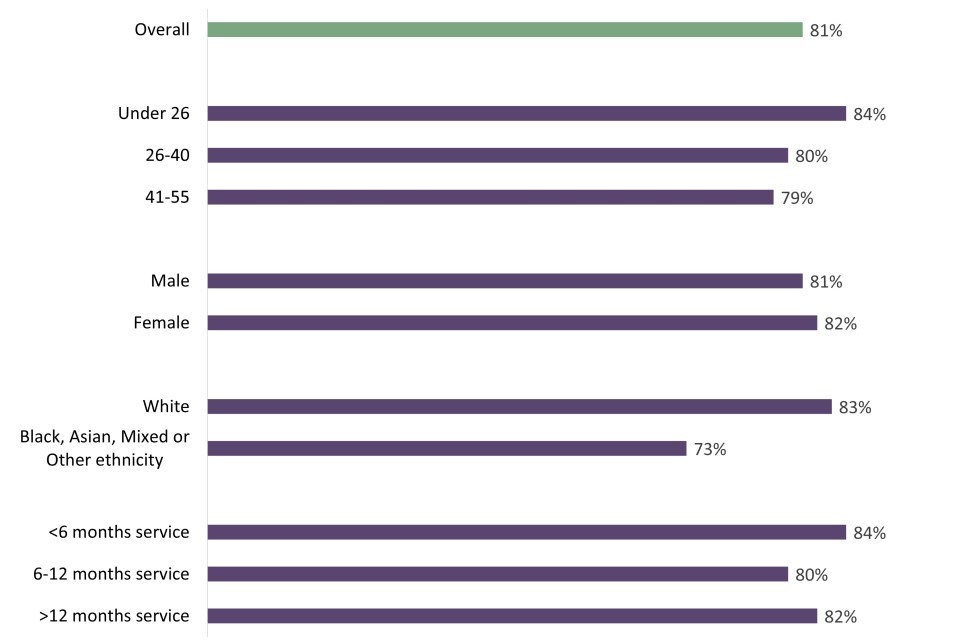

Job satisfaction was consistently high across a range of sub-groups. Satisfaction was highest amongst new officers aged under 26, and lowest for officers aged over 40 or from ethnic minority backgrounds.

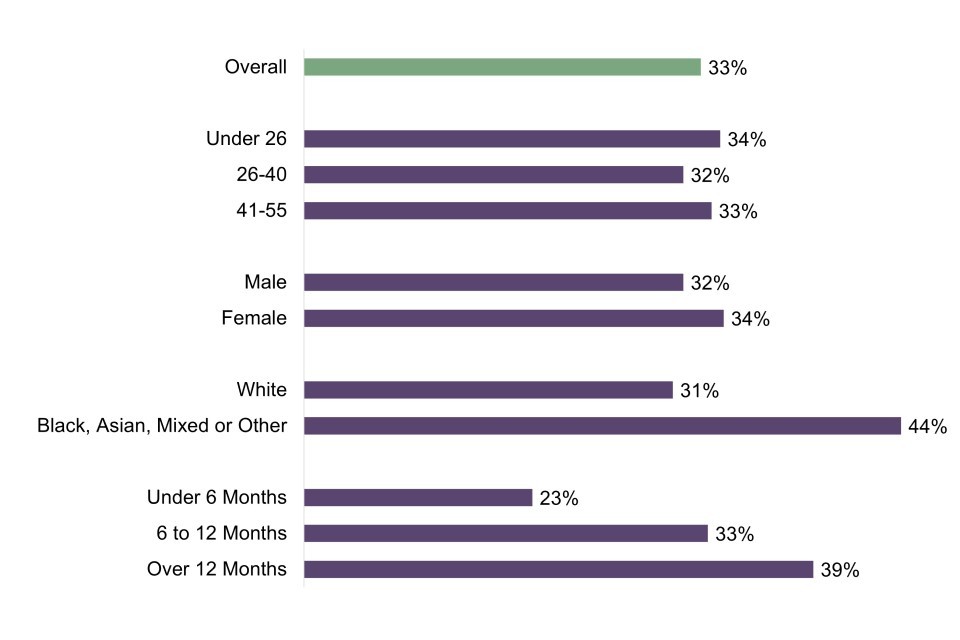

Figure 2: Chart showing the percentage of respondents who were satisfied with their role as a police officer, explored by respondent sub-groups

Q38. Overall, how satisfied are you with your job as a police officer?

Base: Overall respondents (1,842); Under 26 years (800); aged 26 to 40 (909); aged 41 to 55 (132); Male (1055); Female (769); White (1685); Black, Asian, Mixed or Other ethnicity (138); Disability (153); No disability (1659); Heterosexual or Straight (1626); LGB (165); Less than 6 months service (343); 6 to 12 months service (989); More than 12 months service (510)

The role meeting expectations

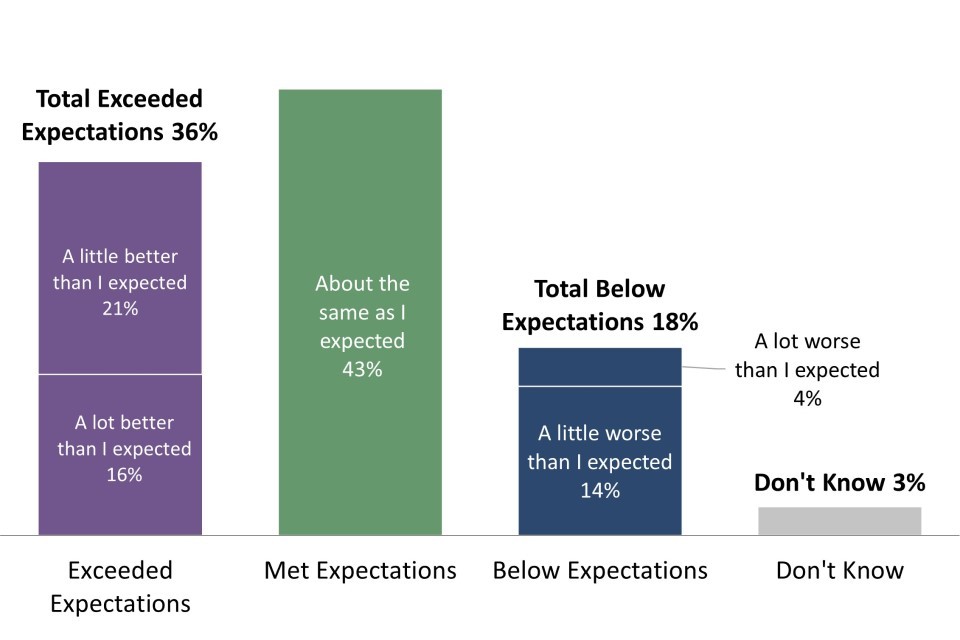

Almost eight in ten new officers indicated their job as a police officer had met or exceeded their expectations prior to joining. More than a third of new recruits suggested the role exceeded their expectations (21% a little better than they expected and 16% a lot better than they expected).

Less than one in five new recruits indicated the police officer role fell below the expectations they had before joining; 4% said the role was a lot worse than they expected.

Figure 3: Chart showing how new recruits felt their officer role met their expectations

Q39. How does your job as a police officer compare to your expectations prior to joining?

Total respondents to this question = 1,842 - unweighted base

Retention and career intentions

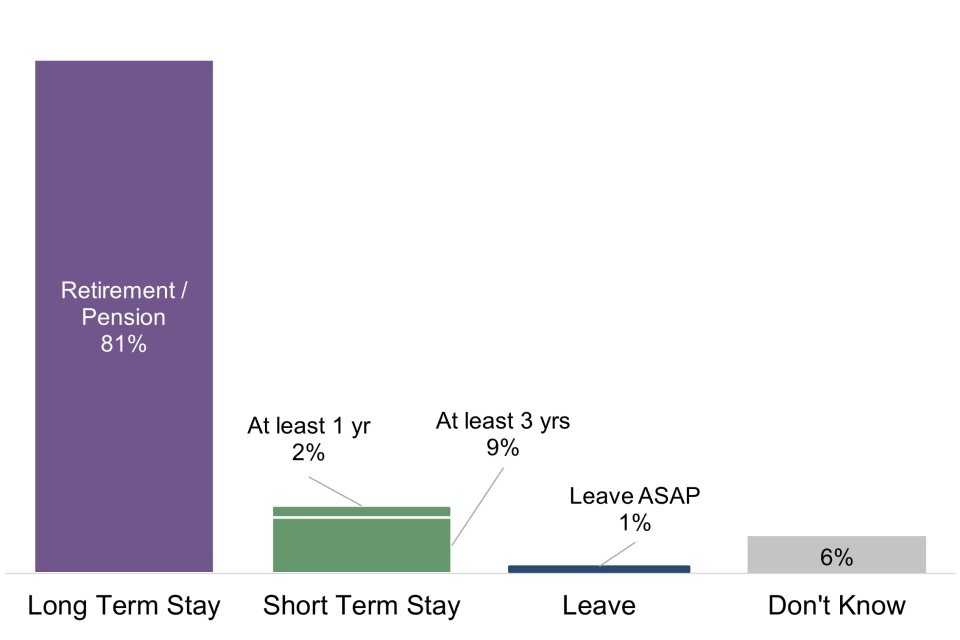

Nine in ten new officers indicated they intend to stay in their role for the next three years or more, with the vast majority intending to stay until retirement or pension age. Only 1% of new officers expressed a clear intention to leave their role in the near future.

Figure 4: Chart showing the career intentions of new police recruits

Q15. How long do you intend to stay in your role as a police officer?

Base: All respondents (3,462)

Intention to continue as a police officer until retirement or pension age was consistently high. The only slight difference within sub-groups was amongst new officers from ethnic minority backgrounds who were a little less likely to have long-term career intentions. Nonetheless, even in this group, more than 70% of new recruits held long-term career intentions.

Figure 5: Sub-group breakdown of long-term career intentions of new police recruits

*Long-Term = ‘I want to continue as a police officer until retirement or pension’

Q15. How long do you intend to stay in your role as a police officer?

Base: Overall respondents (3,462); Under 26 years (1,446); aged 26 to 40 (1,771); aged 41 to 55 (241); Male (2,013); Female (1,422); White (3,184); Black, Asian, Mixed or Other ethnicity (242); Less than 6 months service (703); 6 to 12 months service (1,798); More than 12 months service (961)

3.2 Joining the police service

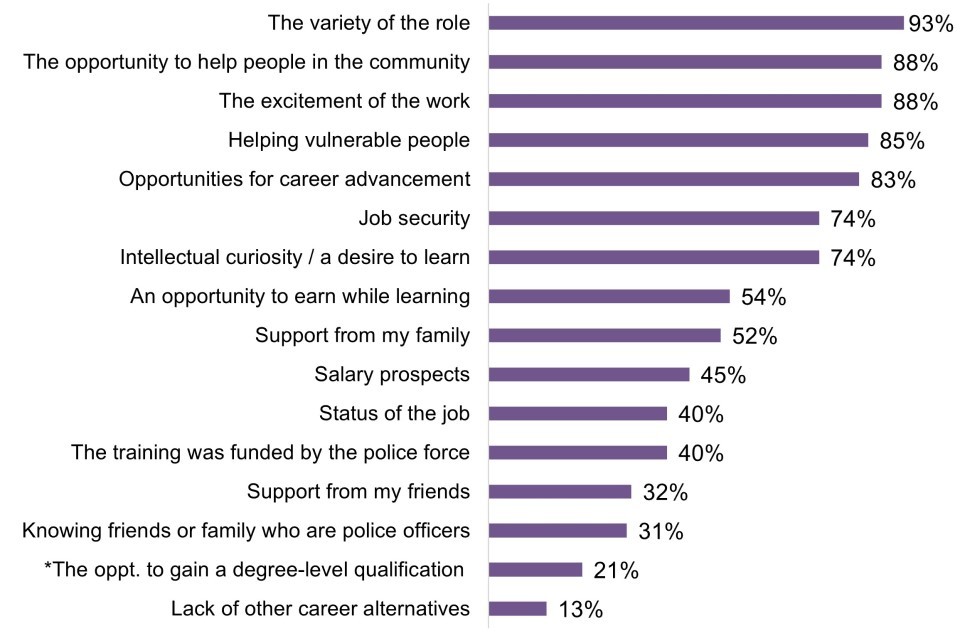

Most influential factors in decision to join

Variety, excitement, helping people in the community and career opportunities were the most influential factors for new officers when deciding to join the police service. Other factors, such as salary prospects, the status of the job, knowing existing police officers and support from family or friends, were less influential.

Figure 6: A chart showing the most influential factors for joining the police selected by new recruits

*This answer option was only made available to those on the Police Constable Degree Apprenticeship entry route, a total of 919 respondents.

Q14. How influential were each of the following factors in your decision to apply to join the police force?

Base: All respondents (3,462)

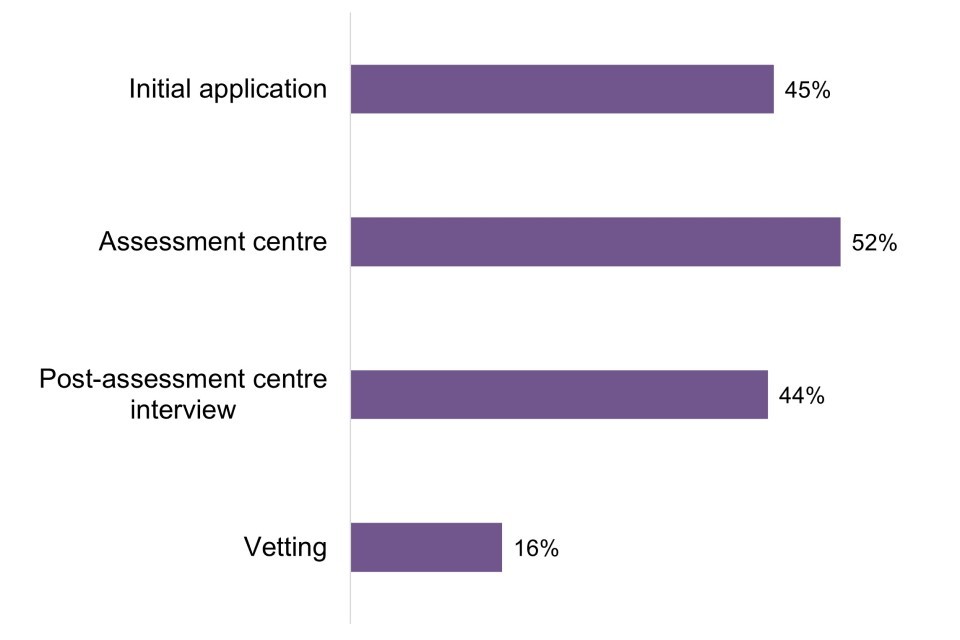

Support received during the recruitment process

More than half of new police officers received support to prepare for the assessment centre, while just under half received support at the application and post-assessment centre interview stages. A smaller proportion of around one in six received support with vetting.

Figure 7: Chart showing proportion of applicants receiving support at each stage of the recruitment process, from either the force directly, family or friends involved in policing or a commercial provider

Q29. During the initial application did you make use of support from any of these sources? Support from the police force directly; Support through a commercial provider or course that I paid for; Support from friends or family involved in policing.

Q31. When preparing for your assessment centre did you make use of support from any of these sources?

Q33. When preparing for your post-assessment centre interview did you make use of support from any of these sources?

Q35. When completing the vetting process did you make use of support from any of these sources?

Q29, Q31 & Q35. Base: Total respondents to this question: (1,842)

Q33 Base: All that attended a post-assessment centre interview from the total respondents to this question (1,511)

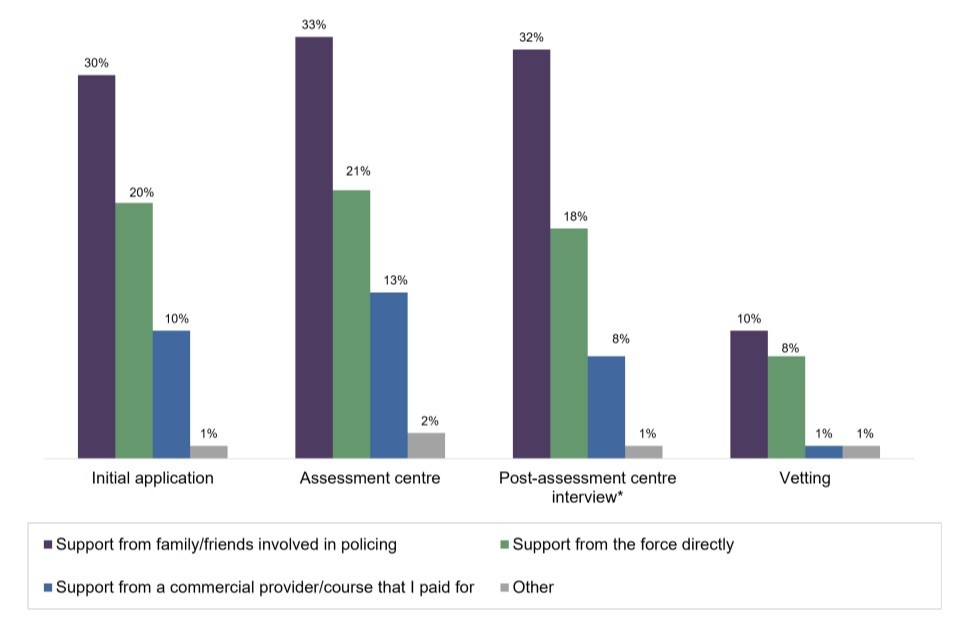

For those that received support, at each recruitment stage family and friends involved in policing were the most likely source, followed by the force itself and then commercial providers.

Figure 8: Chart showing use of support at different stages of the recruitment process

*Calculated as a proportion of those eligible for a post-assessment centre interview

Q30. During the initial application which sources of support did you use?

Q32. When preparing for your assessment centre which sources of support did you use?

Q34. When preparing for your post-assessment centre interview which sources of support did you use?

Q36. When completing the vetting process which sources of support did you use?

Q30, Q32 & Q36. Base: Total respondents to this question: (1,842)

Q34 Base: All that attended a post-assessment centre interview from the total respondents to this question (1,511)

New officers with friends or family in policing were most likely to receive support during the recruitment process and drew upon this network for support at all stages of recruitment. Support from friends or family was also much more common for white officers than those from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Recruits who received recruitment support from their force directly were significantly more likely to be from ethnic minority backgrounds, compared to their white counterparts. Likewise, receiving support from the force was more common for female officers and, as might be expected, officers that had a previous non-officer role in policing.

Paying to receive support from a commercial provider was less common than other types of support. Officers who went down this route were more likely to be male than female, white rather than from an ethnic minority background, and have had a prior policing role.

3.3 Managerial support

Satisfaction with support

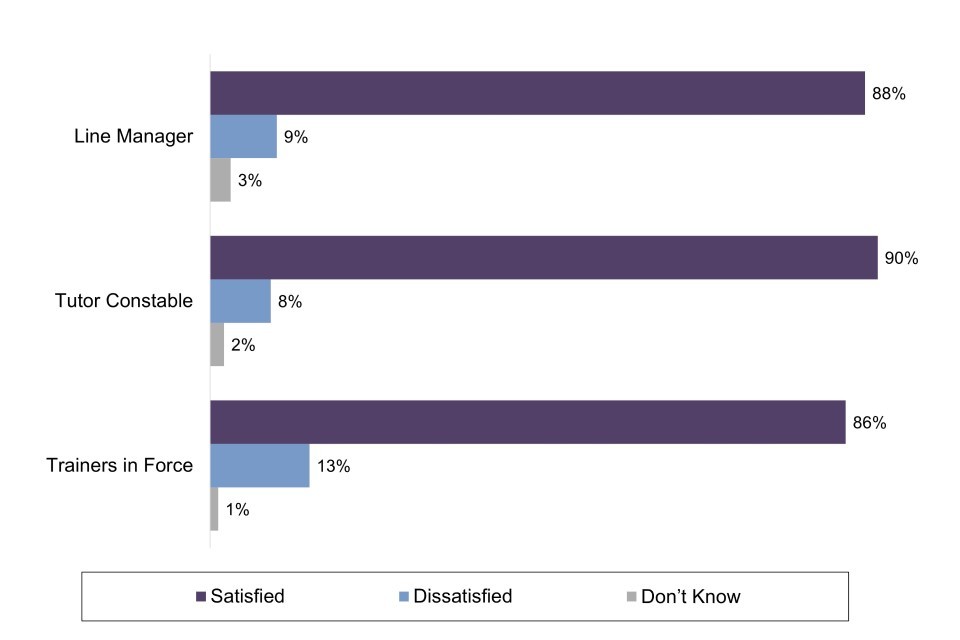

Satisfaction with the support received from superiors was consistently high. More than 85% of new recruits were satisfied with the level of support they had received from their line manager, tutor constable and trainers in their force. Tutor constables generated the highest levels of satisfaction amongst new officers.

Figure 9: Chart showing new recruit perceptions of support from their police force

Q18. Since joining the service, how satisfied would you say you are with the level of support you have received from each of the following?

Base: All respondents (3,462)

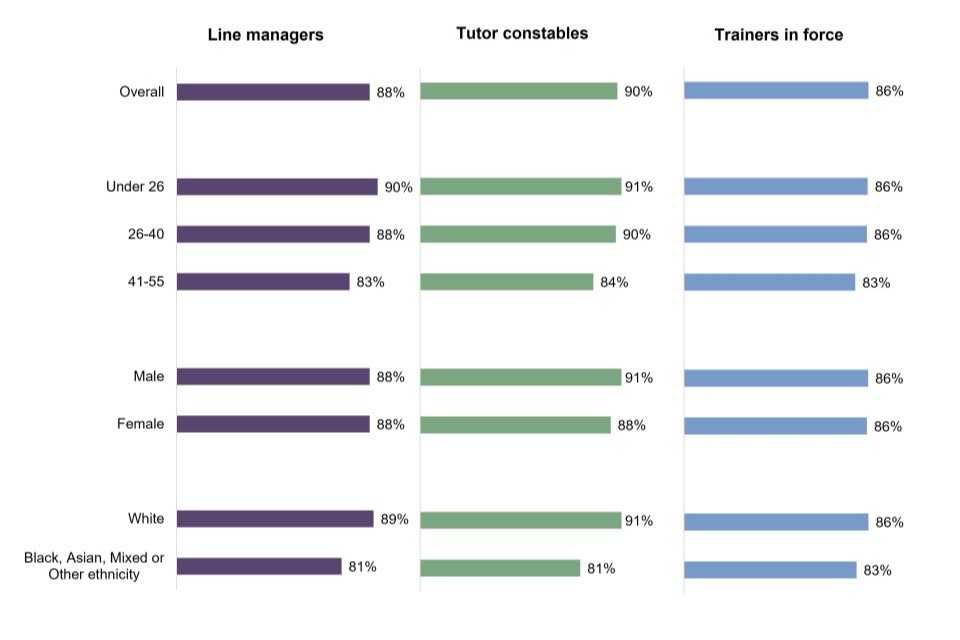

There were consistently high levels of satisfaction with line managers, tutor constables and trainers in the force across all sub-groups, dropping slightly for officers over the age of 40 and ethnic minority officers.

Figure 10: Sub-group breakdown of new recruit satisfaction with their police force’s support

Q18. Since joining the service, how satisfied would you say you are with the level of support you have received from each of the following?

Base: Overall respondents (3,462); Under 26 years (1437); aged 26 to 40 (1762); aged 41 to 55 (239); Male (2003); Female (1413); White (3165); Black, Asian, Mixed or Other ethnicity (242)

Regularity of conversations

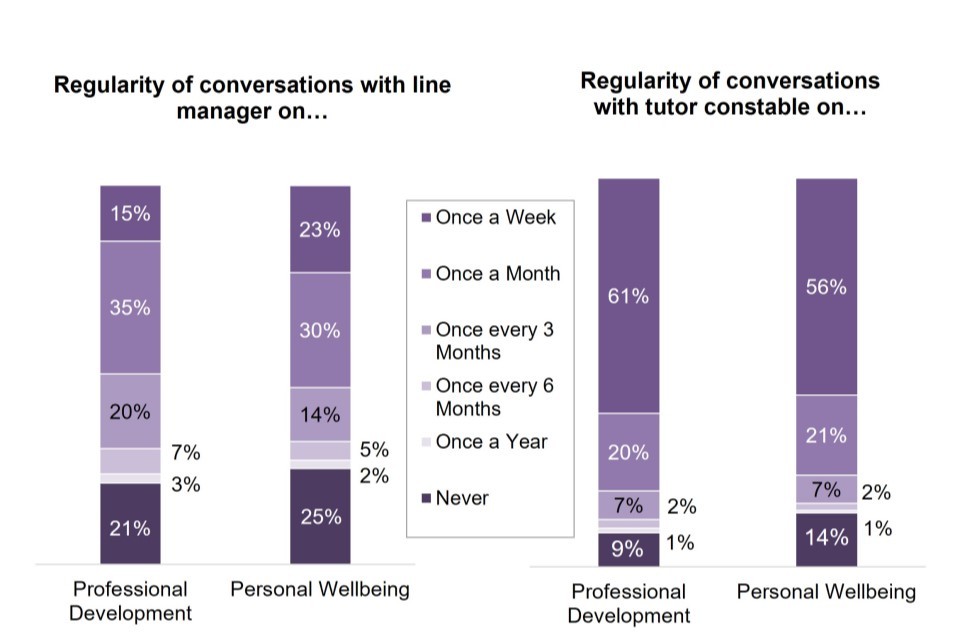

Conversations about professional development and personal wellbeing occur much more frequently with tutor constables than with line managers. Around eight in ten new officers reported having at least a monthly conversation with their tutor constable about their professional development and personal wellbeing. Around half of new officers were having these conversations at least monthly with their line manager. More than one in five new officers have never had these conversations with their line manager.

Figure 11: Charts showing the regularity of new recruit conversations with line managers and tutor constables

Q19. Roughly, how often do you have a conversation with your line manager about…

Q20. Roughly, how often do you have a conversation with your tutor constable about…

Total respondents to Q19 & Q20 = 3,462 – unweighted base

Confidence in having conversations

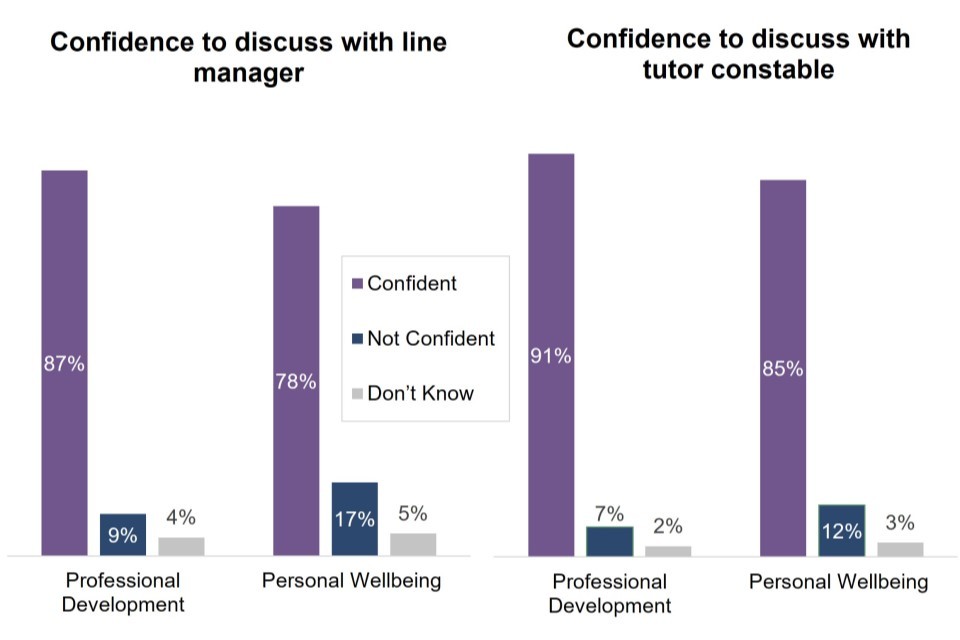

The proportion of new officers that felt confident in discussing their professional development and personal wellbeing with their superiors was generally high. When asked about professional development in particular, around nine in ten new officers felt confident discussing this with their line manager (87%) or tutor constable (91%).

New officers felt more confident discussing professional development over personal wellbeing with both their line manager and tutor constable. On personal wellbeing, the proportion of new officers lacking confidence to discuss this with their line manager (17%) or tutor constable (12%) was higher than for professional development (9% and 7% respectively).

In general, new officers felt slightly more confident having these conversations with tutor constables than line managers.

Figure 12: Charts showing the confidence of new recruits in the support they can get at work

Q.21 How confident would you be to discuss the following with your line manager?

Q.22 How confident would you be to discuss the following with your tutor constable?

Total respondents to Q21 & Q22 = 3,462 – unweighted base

Tutor supervision ratios

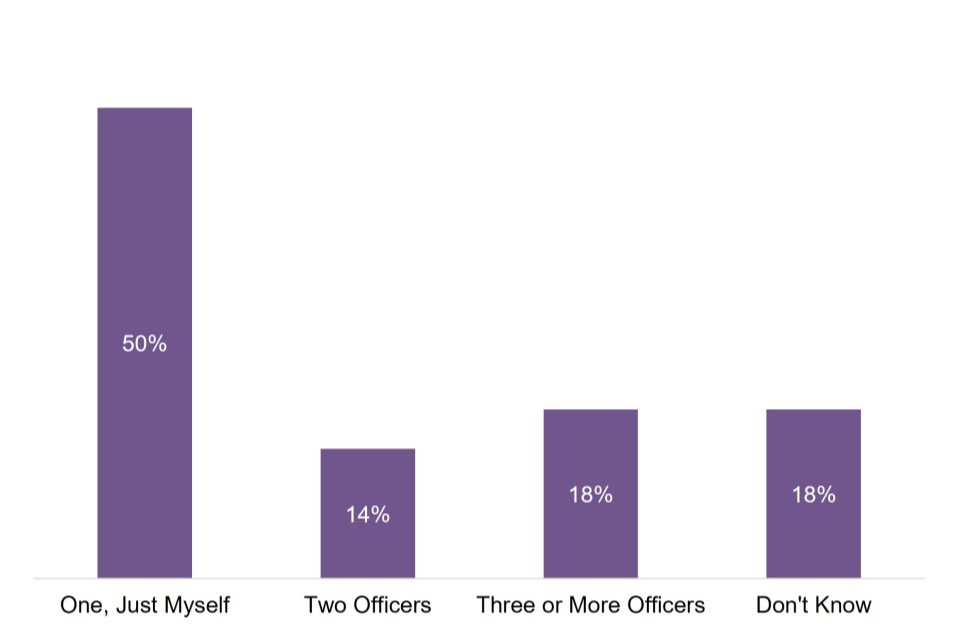

Half of new officers reported being managed by a tutor on a one-to-one basis. A third were managed by a tutor that oversees at least two officers on probation, with nearly one in five reporting that their tutor oversaw three or more new officers.

Figure 13: Chart showing tutor to recruit ratios for new recruits

Q23. Including yourself, how many officers on probation does your tutor constable oversee?

Total respondents to this question = 3,462 – unweighted base

Satisfaction levels were fairly consistent between those who were managed by a tutor that oversees one or two probation officers. Amongst new officers managed by a tutor with three or more probation officers, there was a drop in the proportion that were ‘Very Satisfied’ and an increase in the proportion that were ‘Fairly Satisfied’.

3.4 Inclusion and wellbeing

Inclusion

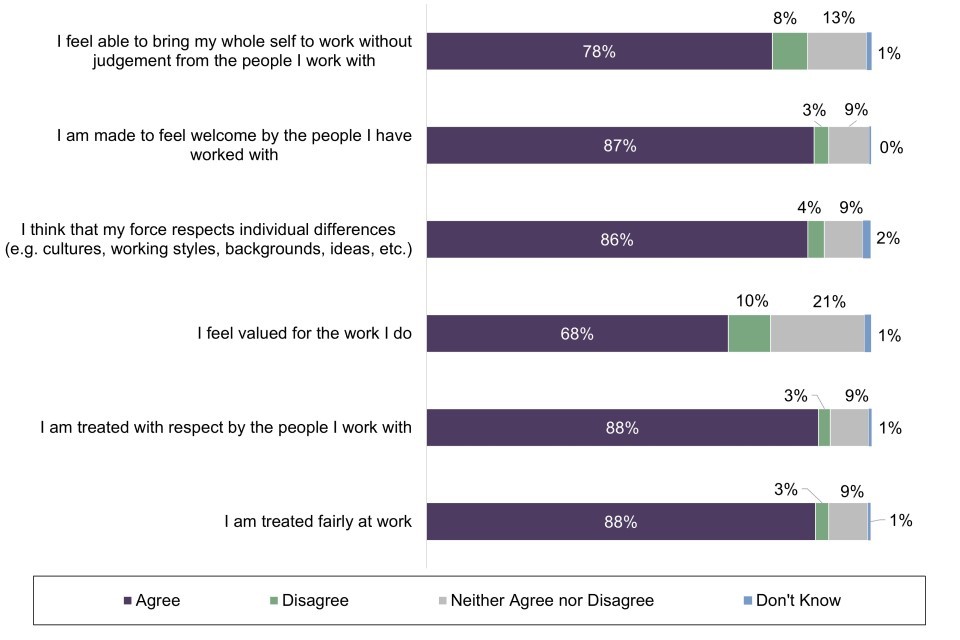

A high proportion of new officers felt respected, welcomed, treated fairly and able to bring their whole self to work. When asked if they felt valued for the work that they do, new officers were positive overall, but less so than for other inclusion statements. Over two-thirds (68%) of new officers agreed they feel valued, but a significant minority either disagreed (10%) or opted to neither agree nor disagree (21%).

Figure 14: Chart showing new recruit feelings of inclusion at work

Q24. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

Base: All respondents (3,462)

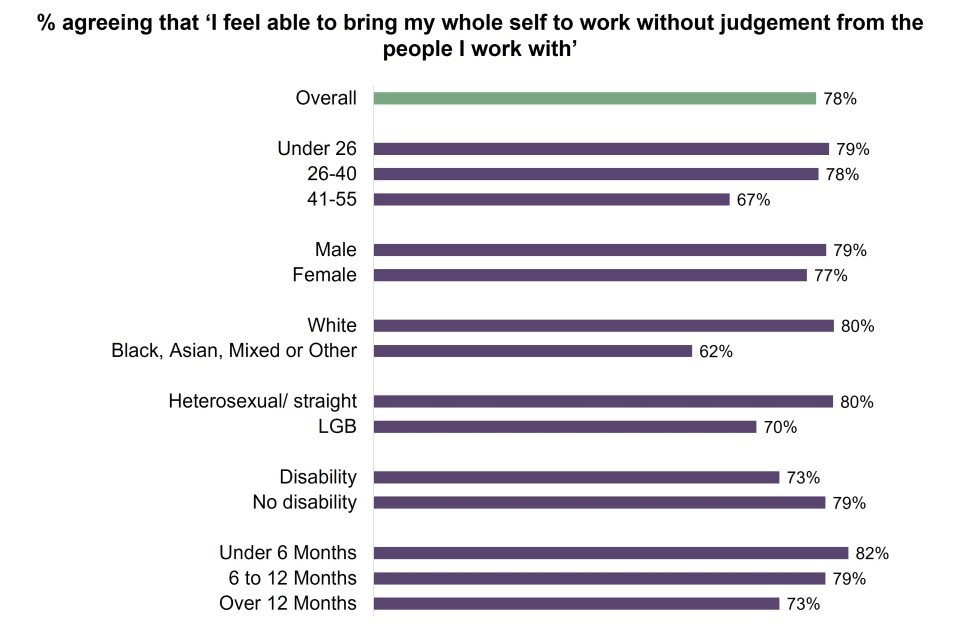

Most new officers across all sub-groups agreed they can bring their whole self to work without judgement. However, officers who identified as LGB, officers with a disability, officers over the age of 40 and officers from ethnic minority backgrounds were all less likely to agree.

Figure 15: Sub-group breakdown of new recruits’ sense of inclusion at work

Q24. To what extent do you agree or disagree with the following statements?

Base: Overall respondents (3,462); Under 26 years (1446); aged 26 to 40 (1771); aged 41 to 55 (241); Male (2013); Female (1422); White (3184); BAME (242); Less than 6 months service (703); 6 to 12 months service (1798); More than 12 months service (961); Heterosexual or Straight (3042); LGB (318); Disability (274); No disability (3128)

Wellbeing

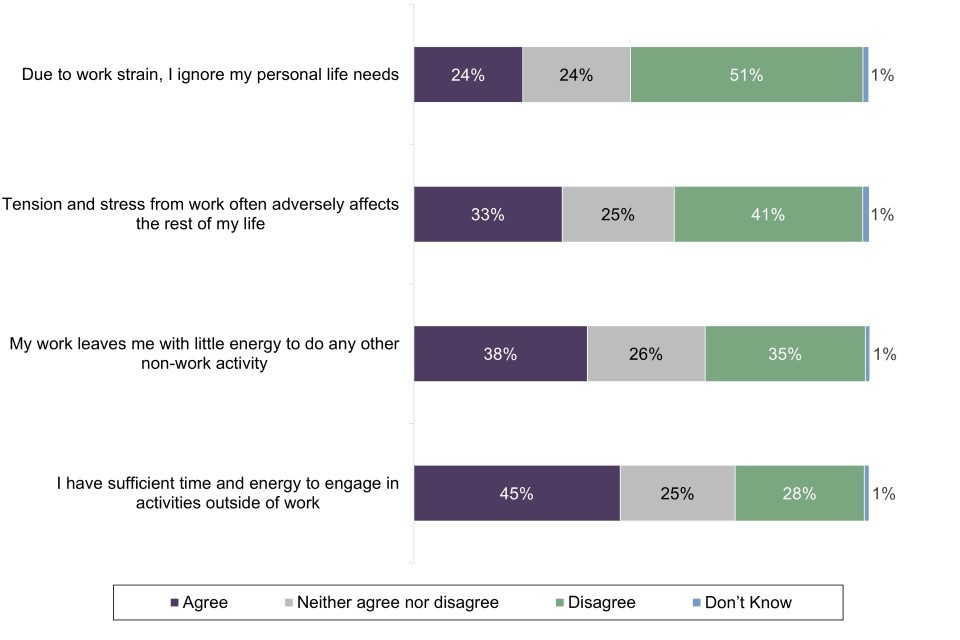

A third of new officers reported that tension and stress from work adversely affects the rest of their life. A quarter ignore needs in their personal life due to work strain, while nearly four in ten reported that work leaves them with little energy to do any other non-work activity. Just under half felt they have sufficient time and energy to engage in activities outside of work.

Figure 16: Chart showing recruit sense of wellbeing at work

Q26. To what extent do you agree with each of the following statements?

Base: All respondents (3,462)

New officers that have been in the force for over 12 months and those from ethnic minority backgrounds were most likely to feel that work stress was adversely affecting the rest of their life.

Figure 17: Sub-group breakdown of new recruits’ work impacting the rest of their lives

Q26. To what extent do you agree with each of the following statements?

Base: Overall respondents (3,462); Under 26 years (1446); aged 26 to 40 (1771); aged 41 to 55 (241); Male (2013); Female (1422); White (3184); Black, Asian, Mixed or Other (242); Less than 6 months service (703); 6 to 12 months service (1798); More than 12 months service (961)

3.5 Uplift cohort profile

The age, gender and ethnicity of new recruits are collected in detail and reported regularly in Home Office statistical publications. Beyond these categories, the New Recruits Onboarding Survey also provided insight into some other characteristics of the new cohort.

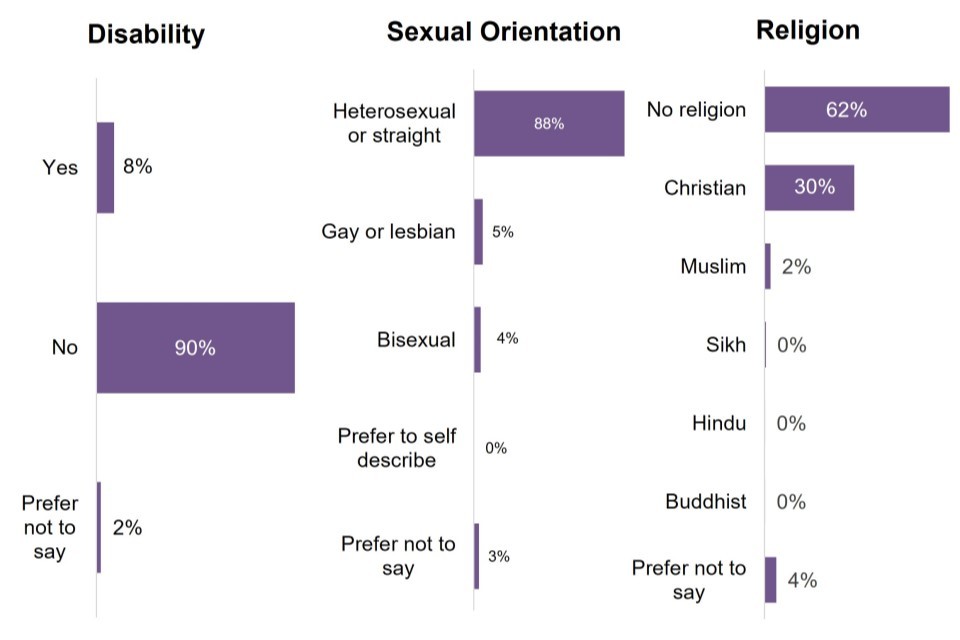

Disability, sexual orientation and religion

The survey asked new officers whether they consider themselves to have a disability. For the purpose of the survey, disability was defined as a physical or mental impairment, which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on a person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities. This includes progressive and long-term conditions from the point of diagnosis such as HIV, multiple sclerosis, cancer, mental illness or mental health problems, learning disabilities, dyslexia, diabetes and epilepsy. This also included ‘disabled’ as per the definition set out in the Equality Act 2010, as well as wider conditions, including neurodiversity. The findings show that 8% of new recruits reported having a disability by this definition.

When asked about their sexual orientation, 88% of new recruits reported identifying as ‘Heterosexual or straight’. A further 5% of recruits identified as ‘Gay or lesbian’, 4% identified as ‘Bisexual’, and fewer than 1% chose to ‘Self-describe’ their sexual orientation in another way.

Most new recruits reported having ‘No religion’ (62%). The largest religious identity reported amongst recruits was ‘Christian’ (30%), and 2% of new recruits reported being ‘Muslim’.

Figure 18: Charts showing disability, sexual orientation and religion of new recruits

Q6. Disability is a physical or mental impairment, which has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on a person’s ability to carry out normal day-to-day activities. This includes progressive and long-term conditions from the point of diagnosis, such as HIV, multiple sclerosis, cancer, mental illness or mental health problems, learning disabilities, dyslexia, diabetes, and epilepsy. This also includes ‘disabled’ as per the definition set out in the Equality Act 2010, as well as wider conditions, including neurodiversity.

Do you consider yourself to have a disability according to the definition above?

Q13.Which of the following options best describes how you think of yourself?

Q9. What is your religion even if you are not currently practising?

Total respondents to each question = 3,462 - unweighted base

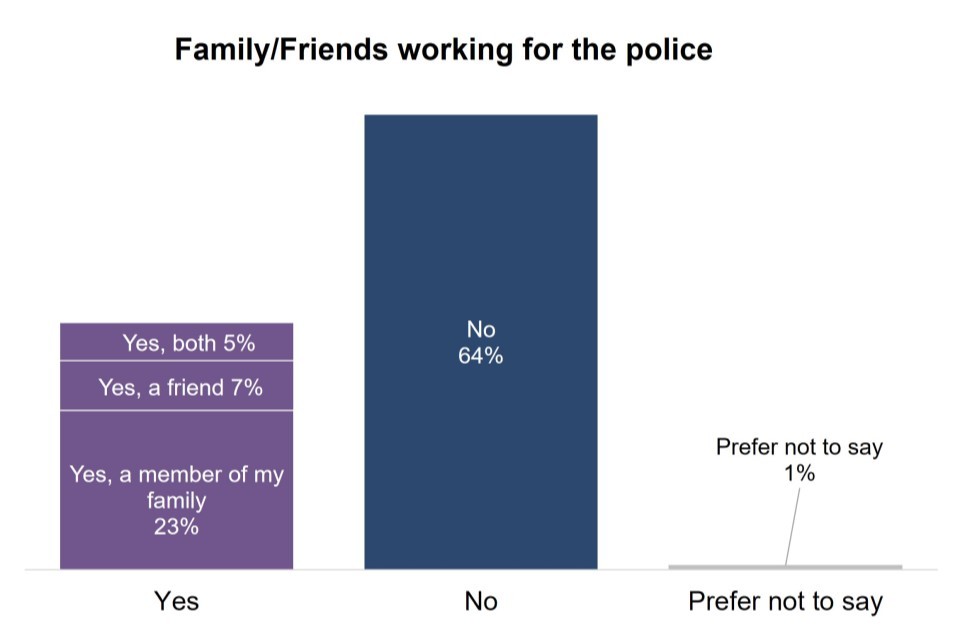

Prior links to policing

More than a third of new officers (35%) had either a family member or friend who had worked as a police officer or police staff member. Of these, the majority (28%) had a family connection into policing.

Figure 19: Chart showing new recruits links to policing via family or friends

Q45. Has a member of your family or a friend worked for the police, either as a police officer or police staff?

Base: All respondents (3,462)

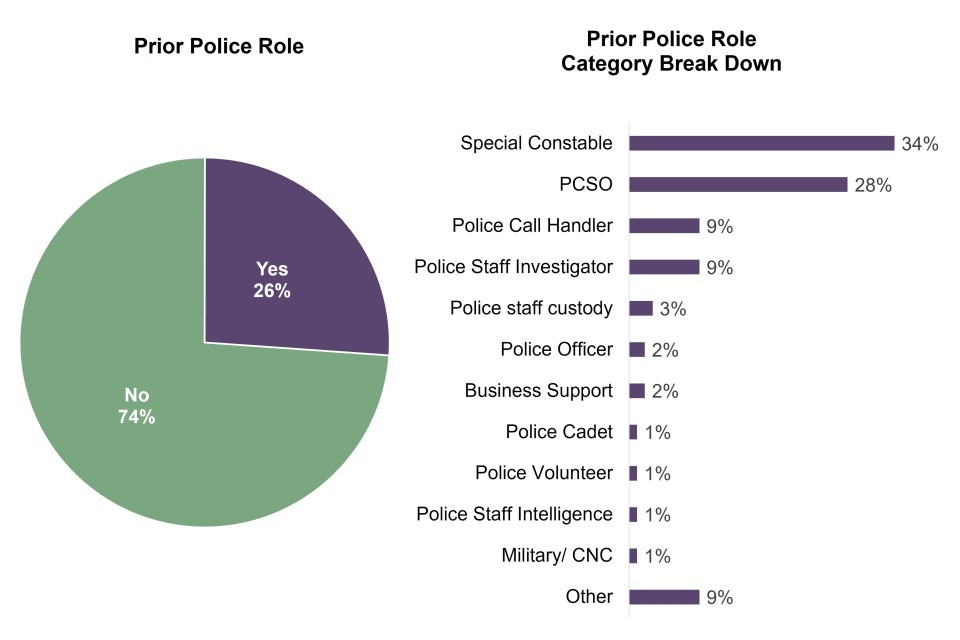

A quarter of new police officers had previously held another policing role before becoming a police officer. New officers have come from a wide range of other policing roles, but the most common route was having previously been a Special Constable or Police Community Support Officer (PCSO).

Figure 20: Charts showing new recruits with prior policing roles

Q46. Prior to becoming a police officer, did you hold any other role within policing (e.g. PCSO, Special Constable, Police staff etc.)?

Total respondents to this question = 3,462 - unweighted base

Q47. What was your previous policing role?

Total respondents to this question = 903 - unweighted base

Previous job sector

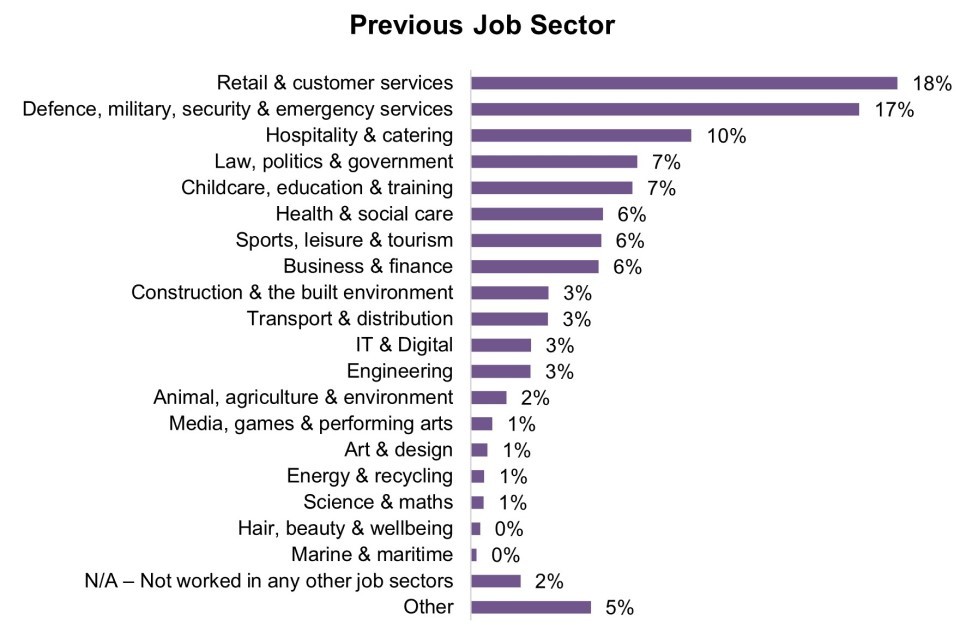

New police officers had a wide variety of job roles immediately before becoming police officers, with the most common job sectors being ‘Retail & customer services’ (18%) and ‘Defence, military, security & emergency services’ (17%).

Figure 21: Chart showing the previous job sectors of new recruits

Q49. What was the main job sector that you worked in before becoming a police officer?

Total respondents to this question = 3,462 - unweighted base

-

Transferees were excluded as they do not go through the same onboarding process as a newly recruited officer. ↩