Home Office Review: The process of police officer dismissals (accessible)

Updated 26 October 2023

September 2023

Ministerial foreword

Sir Robert Peel famously said, “the police are the public, and the public are the police”. But this does not mean the police should be held to the same standards as the general public. The Government, the public and the policing sector should rightly expect more.

Serving in the police is a privilege. The Office of Constable brings with it substantial powers, which is why it is so important that officers attest to serve with fairness, integrity, diligence and impartiality. These powers are also a key reason why we expect such high standards from our officers and why it is crucial that the systems in place are effective at holding officers to account.

This Government is committed to providing the police with the powers they need to protect the public, and no less committed to ensuring that when officers fall seriously short of the high standards expected of them, they are swiftly identified and robustly dealt with. Police dismissals form part of a wider disciplinary system which has been the subject of significant reform in recent years. Despite that, we have seen a number of high-profile cases which have given rise to serious concerns about the standards and culture within policing.

This has led to broader questions, such as those arising from Baroness Casey’s Review into the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS), on whether the system is appropriately balanced to ensure a fair but robust disciplinary process which takes appropriate account of public confidence It is imperative that there are effective methods in place to remove those officers from policing who undermine the hard work of the vast majority of their colleagues, who serve with bravery and integrity, and seriously let down the communities they serve.

I am incredibly grateful to all those who provided evidence to this review. We have listened to your views, we have considered the evidence and we are now taking action. This report sets out the findings of the review and the Government’s proposals to reform the system. This action will improve, clarify and strengthen the disciplinary system, addressing concerns around policing standards and helping to re-build public confidence. Rt Hon Suella Braverman KC MP Home Secretary

Executive summary

This review was designed to assess whether the current system is both fair and effective at removing those officers[footnote 1] who have no place in policing. Having considered the findings of this review, the Government is now announcing a package of substantial reforms to deliver improvements to misconduct proceedings, vetting and performance. This will ensure that those not fit to serve can be swiftly exited from policing, for the benefit of both the public and the wider workforce.

In conducting this review, we have examined evidence from policing stakeholders themselves, existing research and a significant quantity of data. But it has also been important to consider why previous changes to the system were made and whether the rationale for doing so remains valid. The review, ultimately, has sought to ensure that the system is appropriately balanced. In his 2014 review of the police disciplinary system, Major-General Chip Chapman weighed up this very point[footnote 2]:

I have been mindful of this distinction and the need to allow police forces ‘to manage their business’ as one would expect of a CEO. It is right that authority and responsibility should predominantly lie with the police leadership: what is then done with those two features is even more important. Where there are recommendations that counter this, it is because of the need for transparency, removal of opaqueness or the requirement for increased trust by the public in the internal mechanisms of the police disciplinary system. That is, helping the police to help themselves.

In light of the criticism aimed at policing in recent years, it has never been more important that there is independence, openness and transparency – core reasons for the Government first introducing public misconduct hearings in 2015 and then independent Legally Qualified Chairs (LQCs) the following year.

Our conclusion is that whilst these principles remain valid, it is important that we redress the balance in the system. It simply cannot be right that Chief Constables[footnote 3] are forced into retaining officers who commit serious acts of misconduct, or whose circumstances are such that they cannot maintain vetting, and so we are recommending improvements to support them in upholding the very highest standards in their forces.

The review makes a number of key findings which are set out below. Its recommendations, as a package of reforms, are expected to preserve crucial independence in the system, while giving Chief Constables greater responsibility over their workforce – through the chairing of misconduct panels, the widening of cases heard at accelerated hearings, improved vetting processes and a streamlined performance system. As a package, this is intended to deliver improvements across all three key areas: misconduct, vetting and performance, to help deliver those crucial improvements to public trust and confidence. A list of all recommendations can also be found at Annex A.

Independent lawyers and Chief Constables both have a role to play in the system

Whilst this review recommends retaining legally-qualified panel members, we consider that the current system is unhelpfully imbalanced, leaving Chief Constables with insufficient responsibility over proceedings relating to their own workforce. That is why we are recommending that Chief Constables (or other senior officers[footnote 4]) should now chair misconduct hearings, but that they continue to be supported on that panel by a legally-qualified panel member and independent panel member.

Chief Constables will also have an increased role in the system, including hearing a wider set of cases under accelerated hearings, with a new power to delegate relevant functions to other senior officers, in order to speed up processes.

Gross misconduct should in most cases mean dismissal

Gross misconduct is, by its very definition[footnote 5], behaviour which is so serious that it would justify dismissal. Cases of proven gross misconduct can, and often do, have a substantial impact on public confidence in policing. Yet, as set out in chapter 3 of this report, there have been a number of cases where officers found to have committed gross misconduct have received lesser sanctions and were not dismissed, with those chairing misconduct proceedings required to consider the least severe sanction first. Whilst there will be exceptional circumstances where it will be appropriate to issue a sanction other than dismissal for gross misconduct, this should indeed be the exception, rather than a frequent or regular occurrence. That is why we are recommending a presumption for dismissal, for any officer found to have committed gross misconduct.

This will be supported by a list of criminal offences, conviction of which will automatically amount to gross misconduct, removing the risk of officers convicted of serious criminal offences remaining in policing.

Officers must maintain vetting – or risk removal from policing

Chief Constables should not be required to retain officers whose circumstances are such that they are unable to maintain a basic level of vetting. Doing so represents an unacceptable risk to policing and can significantly impact public confidence. The holding of vetting should be made a statutory or regulatory requirement for constables, meaning that failure to maintain basic vetting renders an officer liable to removal from the force. Further consultation with the sector will be required to develop consensus on the most appropriate mechanisms.

The system for dealing with performance is underused and in need of reform

The current performance system is unwieldy and complex. The process will be streamlined to ensure that under-performing officers can be efficiently dismissed from the service, removing unnecessary bureaucracy and speeding up these decisions. Alongside this, the guidance underpinning the process for discharging officers who are on probation will be improved so that Chief Constables, at their discretion, are confident under the existing system to swiftly remove probationers who should not go on to continued service with the police.

The disciplinary system should be fair, transparent and effective for all officers and staff, regardless of their background

Trust and confidence in policing require a transparent and effective disciplinary system. It must reassure the public and those within policing that that those officers who fall seriously short of the required standards are dealt with robustly. It must also treat all officers and staff equally and fairly, regardless of their background.

Though the data was limited beyond race, age and sex, the review found evidence of disparities in the dismissals system. It is therefore right that the policing sector seeks to explain why such disparities exist and considers what measures need to be taken to tackle them. To do this effectively, policing must take an evidenced-based approach and that is why this report makes recommendations to work together in gathering better and more transparent data.

One force told us that “dismissing those who should not be in policing at all is at the heart of this crisis of confidence”. Whilst we agree it is vital those officers who fall seriously short of the expected standards are dismissed, the focus on dismissals and the misconduct system should not be at the expense of further action required by forces to improve public confidence in policing. Recent high-profile cases have not only damaged public confidence in policing, but have also exposed failures to treat allegations against officers seriously and take robust action which could have prevented further misconduct or criminality. We expect this review’s recommendations to help to strengthen public confidence, but action by the policing sector to address these challenges must go much wider. Forces must continue to focus on improving police culture, preventing misconduct in the first place, supporting those challenging or reporting wrongdoing and ultimately thoroughly investigating those allegations swiftly and to a high standard.

Introduction

Legislative background

In December 2014, Major-General Chip Chapman published his review[footnote 6] into the police disciplinary system, having been tasked by the then Home Secretary, Rt Hon Theresa May MP, to identify proposals for a reformed disciplinary system which was “clear, public-focussed, transparent and more independent”.

What ultimately followed was several years of legislative reform to strengthen the complaints and discipline systems, which included public misconduct hearings in 2015 and the introduction of LQCs in 2016, replacing senior officers as the chair of misconduct hearings. Both of these changes were made under the Police (Conduct) (Amendment) Regulations 2015[footnote 7].

Then, on receiving Royal Assent on 31 January 2017, the Policing and Crime Act 2017 brought further substantial changes to the system, including reform of the then Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) to what is now the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC), the introduction of the police Barred and Advisory Lists to prevent those dismissed from re-joining policing and provisions to allow former officers to face misconduct proceedings, despite their retirement or resignation from their force.

More recently, the Government introduced a series of secondary legislation in February 2020. These measures, broadly welcomed by the sector, gave additional powers to the IOPC, provided LQCs with a greater role to case manage hearings, implemented measures to improve timeliness, redefined the threshold for misconduct and brought into effect the Reflective Practice Review Process (RPRP) – a process to move away from a blanket approach for all breaches of the Standards of Professional Behaviour[footnote 8], no matter how low-level they are, to one which focusses on a culture of learning and reflection for minor breaches and disciplinary action for serious breaches.

There are 2 forms of behaviour which can currently result in an officer being dismissed from the police – gross misconduct[footnote 9], which is handled under the Police (Conduct) Regulations 2020, or gross incompetence (or unsatisfactory performance / attendance)[footnote 10], which is handled under the Police (Performance) Regulations 2020.

Officers with a case to answer for gross misconduct can be referred either to a misconduct hearing or accelerated hearing (previously known as a special case hearing). In January 2016, LQCs were introduced to chair misconduct hearings, supported by an officer of at least Superintendent rank and an independent panel member (IPM)[footnote 11]. However, where there is sufficient evidence (on the balance of probabilities) of gross misconduct and it is in the public interest for the individual to cease to be an officer without delay, officers are instead referred to an accelerated hearing. This is a fast-track process chaired by a Chief Constable[footnote 12] (or by a panel composed in accordance with regulation 55 of the Police (Conduct) Regulations 2020 where the subject of the disciplinary proceedings is a senior officer).

Officers whose performance is considered unsatisfactory can be referred into the three-stage performance procedures. If improvements are not made, officers can ultimately move to a third stage meeting, at which they could be dismissed. They can also be referred in directly to this stage for instances of gross incompetence. These meetings are chaired by a senior officer or a senior Human Resources (HR) professional.

Fuller information on all of the processes and procedures on police performance can be found in the Home Office’s Statutory Guidance on Professional Standards, Performance and Integrity in Policing[footnote 13].

The below chart sets out the processes involved in those cases and the available outcomes. There is a separate internal process available to Chief Constables, enabling them to discharge probationary officers under certain circumstances – this is covered within chapter 5 of this report.

Gross Misconduct

(or misconduct where a final written warning was in place at the time of the initial severity assessment, or the officer had been reduced in rank within 2 years of that assessment)

Misconduct hearing

LQC-chaired

- Written warning (misconduct only)

- Final written warning

- Reduction in rank

- Dismissal

or

Accelerated Hearing

Chief Constable- chaired

- Final written warning

- Reduction in rank

- Dismissal

Gross Incompetence

Unsatisfactory Performance / Attendance

Performance Meeting (third stage)

Senior officer or HR- chaired

- Redeployment

- Final written improvement notice (or extension)

- Reduction in rank

- Dismissal

Initiation of a review

In October 2022, the then Minister of State for Crime, Policing and Fire, Rt Hon Jeremy Quin MP, announced a review into the process of police officer dismissals, as part of a Written Ministerial Statement and following publication of Baroness Casey’s interim findings on misconduct in the MPS[footnote 14]. This Ministerial Statement identified that there had been several high-profile failings by the police in recent years, which had “substantially diminished public trust” in the MPS.

On 17 January 2023, the Home Secretary, Rt Hon Suella Braverman KC MP, launched this review as part of a statement to the House of Commons, following the conviction of former MPS officer, David Carrick, for a number of rapes and serious sexual offences[footnote 15]. In announcing this review, the Home Secretary stated that the misconduct and dismissals process “takes too long, it does not command the confidence of police officers and it is procedurally burdened”.

The Home Secretary closed her statement by saying that the Government will not shy away from challenging the police to meet the expected standards, stating that “change must happen and, as Home Secretary, I will do everything in my power to ensure that it does”.

Importance of dismissal

Though the majority of the public has confidence in the police, it has been impacted by recent events. The Crime Survey for England & Wales (CSEW)[footnote 16] found respondents reported their ‘overall confidence in the local police’ as 63% in the year ending 31 March 2006 rising to 72% in the year ending 31 March 2011. In the year ending 31 March 2012 the figure was 75% rising to 78% in the year ending 31 March 2016, before falling to 68% in the year ending 31 March 2023.

Several surveys have explored the potential reasons for declining public perceptions of the police. The IOPC conducted a survey in 2022[footnote 17], finding that of those who reported feeling negative towards the police, a quarter stated that the reason they felt negatively was due to racism, sexism and homophobia. While 13% reported that they felt negatively due to police misconduct, 9% due to corruption within the police and 8% due to the police abusing their position of power.

A survey was also conducted as part of Baroness Casey’s review in 2023[footnote 18], asking Londoners why they think that the reputation of the MPS has worsened. Respondents were most likely to cite poor behaviours and actions of individual officers in the MPS (77%) and high-profile incidents and scandals (68%).

Research has also found perceptions of corruption[footnote 19] and misconduct[footnote 20] have the potential to profoundly damage public perceptions of police legitimacy and fairness. Public confidence and trust in the police and criminal justice system more generally is impacted by the ability for guilty officers to be punished for their actions[footnote 21]. Systems that enable the poor behaviour of officers to be challenged can help maintain the public’s trust and confidence in the police[footnote 22], highlighting the importance for forces to have the ability to dismiss officers who engage in misconduct.

In addition, research has highlighted the importance of dismissal to avoid further misconduct. Several studies have demonstrated that those who engage in misconduct and unethical behaviour increase the risk of spreading this behaviour to other officers[footnote 23]. A study of MPS data (35,924 officers and staff from 2011 to 2014) used line management history to infer officer peer groups and found that an increase of 10% in prior peer misconduct increased an officer’s later misconduct by 8%[footnote 24]. These results were found to be consistent when an officer relocated to a new group.

This is particularly concerning considering the findings from the interim report by Baroness Casey in 2022[footnote 25] which found those who engage in misconduct are more likely to have been involved in multiple incidents. This analysis showed that, within the MPS between April 2013 and March 2022, 20% (1,809) of the 8,917 individuals in the misconduct system had been involved in more than one case of misconduct. 1,263 were involved in 2 separate misconduct cases and over 500 were involved in 3 to 5 cases of misconduct. Only 13 of the 1,809 officers and staff with more than one misconduct case against them had been dismissed.

It is evident that high-profile cases of serious police misconduct can impact public trust and confidence. This risks being exacerbated where those found guilty of gross misconduct are not subsequently dismissed from policing. It has never been more crucial for Chief Constables to drive improvements in standards, but some Chief Constables have questioned how they can be held to account on their performance without having full control over who should or shouldn’t be dismissed in their force. This impacts on Chief Constables’ confidence in their ability to protect the public from some officers who haven’t been dismissed, yet the circumstances require them to remain on certain restrictions. This was demonstrated in the recent successful challenge of a misconduct panel decision by the Chief Constable of the British Transport Police[footnote 26].

The ability for forces to dismiss officers is also important in terms of sending a message of the expected standards required to other officers[footnote 27] and can help deter other officers from committing offences[footnote 28]. However, it is crucial to highlight that an effective dismissals process is only one part of the solution in dealing with misconduct and setting standards in policing. Broader cultural change within forces is imperative to ensure that adverse attitudes and behaviours are not left unidentified or unchecked, and subsequently permitted to develop into serious cases of misconduct. It is for Chief Constables to drive a decisive shift within their forces against toxic cultures. Part 2 of the Angiolini Inquiry - for which Government published terms of reference in May 2023[footnote 29] - will examine culture among other national policing issues and where relevant will make further recommendations for improvement.

Terms of Reference

The following Terms of Reference were published on 17 January 2023[footnote 30], following the Home Secretary’s statement to the House of Commons:

-

Understand the consistency of decision-making at both hearings and accelerated hearings – particularly in cases of discrimination, sexual misconduct and violence against women and girls (VAWG).

-

Assess whether there is disproportionality in dismissals and, if so, examine the potential causes.

-

Establish any trends in the use of sanctions at both hearings and accelerated hearings – in particular, the levels of dismissals.

-

To review the existing model and composition of misconduct panels, including assessing the impact of the role of legally qualified chairs (LQCs), review whether chiefs should have more authority in the process (including whether the chief should take the decision with protection for the officer provided by way of a right of appeal to the Police Appeals Tribunal and consideration of when barring occurs) and review the legal/financial protections in place for panel members.

-

Ensure that forces are able to effectively use Regulation 13 of the Police Regulations 2003 to dispense with the services of probationary officers who will not become well-conducted police officers.

-

Review the available appeal mechanisms for both officers and Chief Constables, where they wish to challenge disciplinary outcomes or sanctions, ensuring that options are timely, fair and represent value for public money.

-

Consider the merits of a presumption for disciplinary action against officers found to have committed a criminal offence whilst serving in the police.

-

Review whether the current three-stage performance system is effective at being able to reasonably dismiss officers who demonstrate a serious inability or failure to perform the duties or their rank or role, including where they have failed to maintain their vetting status.

Methodology

In conducting this review, it has been crucial to consider a range of evidence to inform recommendations. It has been conducted utilising 3 methods of collecting evidence.

Stakeholder evidence

The review has engaged across the policing sector and considered individual evidence carefully. On launching the review, the Home Office wrote to a number of stakeholders, asking for written submissions of evidence on the specific Terms of Reference.

Aside from national policing stakeholders, the Home Office provided a number of other bodies with the opportunity to contribute evidence to this review, including:

-

Police staff networks

-

Legally Qualified Chairs and Police Appeals Tribunal Chairs

-

Non-territorial law enforcement bodies

-

Academics

-

Barristers and solicitors

The comments received have been catalogued and carefully considered by the review and a number have been specifically referenced throughout this report.

Research and literature

A review of relevant literature and research evidence was also conducted to support this review. While this was not a systematic review, the search for evidence was conducted using a rigid set of criteria.

Articles from academic journals, as well as reports and publications from relevant organisations were reviewed. The geographical focus of the literature was England and Wales due to the specific nature of the subject-matter, although some international comparison studies were also considered. The search was restricted to evidence published between 2013 and 2023 to ensure that anything published in the lead up to changes in policy and legislation that took place since 2015 was not excluded.

The search for literature identified 76 papers that were relevant to the topic and fit the defined criteria. Each was then reviewed in terms of their methodological robustness and relevance. The findings of these robust and relevant pieces of evidence have been included under the relevant themes throughout this report.

Data

As well as considering existing published evidence, the Home Office has collected a number of data sets from the 43 territorial police forces in England and Wales, allowing for new national-level analysis. These police data include:

-

Information on formal misconduct proceedings under the Police (Conduct) Regulations, and appeals, recorded on Centurion – the complaints and conduct case management system used by Professional Standards Departments within all 43 police forces;

-

Information on officers dismissed through the use of Regulation 13 of the Police Regulations 2003 as recorded by force HR departments; and

-

Information on officers dismissed through the Police (Performance) Regulations as recorded by force HR departments.

Further information on the collection, analysis and limitations of this data can be found in Annex B to this report. Supplementary data tables summarising the analysis have also been published alongside this report.

Term 1: Consistency of decision-making

Understand the consistency of decision-making at both hearings and accelerated hearings – particularly in cases of discrimination, sexual misconduct and violence against women and girls (VAWG).

1.1 Introduction

Cases of discrimination and VAWG-related (including sexual) misconduct have gained greater public attention over recent years due in part to high- profile cases, such as former MPS officer and serial sex offender David Carrick[footnote 31], and instances of racist, misogynistic and homophobic behaviours brought to light in the IOPC’s investigation of behaviour at Charing Cross police station[footnote 32].

In August 2022, the College of Policing published its updated Guidance on Outcomes in Police Misconduct Proceedings[footnote 33]. The guidance notes that “a factor of the greatest importance is the impact of misconduct on the standing and reputation of the [policing] profession as a whole”, specifying that “violence against women and girls perpetrated by a police officer, whether on- duty or off-duty, will always harm public confidence in policing” and will “have a high degree of culpability, with the likely outcome being severe”. On cases of discrimination, the guidance outlines that “discrimination towards persons on the basis of any protected characteristic is never acceptable and always serious.”

The review heard from several respondents who suggested that the College’s guidance is not always consistently applied, with one suggesting that, following some judicial review proceedings, courts have found failures by misconduct panels “to adopt the structured approach required by the College’s guidance in relation to assessing seriousness and to consider the most appropriate sanction for the officer concerned”.

One organisation also observed that, at times, there seems to be “inconsistency in outcomes for officers and for police staff for the same or similar types of misconduct […] and in terms of how seriously those conducting proceedings treat some types of misconduct compared with others (for example, discriminatory behaviour that is misogynistic in nature appearing to have been treated less seriously than racial discrimination)”.

However, it was also noted that some elements of the College’s guidance, particularly in relation to VAWG, were updated relatively recently and therefore its impact on the system may not yet be fully seen.

Research also found that, with consideration to sexual misconduct, similar behaviours and types of incidents may be dealt with inconsistently. Sweeting, Arabaci-Hills and Cole (2020) conducted a study using 155 cases of sexual misconduct within 30 police forces[footnote 34]. Inconsistencies were found in the outcome decisions made at hearings held in response to officers who engaged in sexual misconduct. Dismissal rates were found to vary across England for the same type of sexual misconduct. For example, considering officers involved in sexual relationships with vulnerable victims, 94.4% of cases (18 cases) resulted in dismissal in the south, but only 66.7% (21 cases) in the north. In cases of attempting to establish relationships with members of the public, 70% of officers (10 cases) were dismissed in the south compared with only 40% (10 cases) in the north. There were also inconsistencies in the level of sanction for sexual misconduct, with the lowest recorded being a written warning.

A study conducted by Brown et al. (2019) also found that both formal and informal methods of handling concerns may be applied inconsistently. In a survey of 169 senior women in policing, respondents reported that unwanted comments and jokes made, where they were the target, bystander or had been told about by others, were dealt with informally for 21% of respondents and formally for 17% of respondents[footnote 35]. Unwanted physical contact was reported as being dealt with informally for 11% of respondents and formally for 15% of respondents, and unwanted sexual propositioning was dealt with informally for 8% of respondents and formally for 11% of respondents. These findings highlight that rather than one approach being applied consistently in response to the same types of behaviour, both formal and informal handling are used with similar frequency. This suggests that similar incidents are often dealt with in different ways when concerns are raised. Another study, conducted by Sweeting and Cole (2022), involved focus groups of 25 police trainers. It was found that incidents of sexual misconduct that took place during training were generally dealt with informally, while serious incidents, involving assault, were generally dealt with outside of the training unit[footnote 36].

HMICFRS’ 2022 inspection on vetting, misconduct and misogyny[footnote 37] identified ‘forces’ understanding of the scale of misogynistic and improper behaviour towards female officers and staff’ as an area for improvement. The report suggested many interviewees for the inspection felt that informal challenge of prejudicial and improper behaviour (rather than reporting to a supervisor) was an appropriate way of dealing with it. However, the report also noted that some officers and staff who had experienced such behaviour reported that it was often witnessed by colleagues who rarely challenged the people responsible.

Inconsistencies in decision-making around disciplinary action may result from different perspectives of what constitutes ‘misconduct’ and where the threshold for this is. A study conducted by the College of Policing (Hales et al, 2015) involved interviews with stakeholders and experienced investigators. It was found that interviewees believed there was little clarity about what constituted meeting the misconduct threshold, which was seen to be a very subjective decision[footnote 38]. In contrast, the threshold between ‘misconduct’ and ‘gross misconduct’ was generally thought to be clear.

1.2 Data

NPCC VAWG performance and insights report

In March 2023, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) published data on police-perpetrated VAWG complaints and conduct cases recorded between October 2021 to March 2022[footnote 39]. At the time of data collection, 167 conduct cases (related to 195 allegations) had been finalised. Of these allegations, 21 were referred to proceedings, of which 13 resulted in dismissal of the complaint subject (or they would have been dismissed if they were still in the force), 4 resulted in a final written warning, 1 resulted in a written warning, 1 was not proven and 1 resulted in no further action[footnote 40].

Police perpetrated domestic abuse: report on the Centre for Women’s Justice super-complaint

In their joint report on a police-perpetrated domestic abuse (PPDA) super- complaint[footnote 41], the College of Policing, HMICFRS and the IOPC found that forces often failed to accurately treat PPDA allegations as police complaints and conduct matters, which has led to inconsistent data. The report used a dataset of 122 cases from 2018. In total, 13 of these resulted in a case to answer for misconduct or gross misconduct - 7 of which led to the individual being referred to some form of disciplinary proceeding, 6 led to dismissal (or would have done if the individual had not already left the force) and 1 led to a final written warning.

Barred List data

Data from the Barred List[footnote 42] statistics, published by the College of Policing, shows that between April 2021 to March 2022, categories associated with sexual misconduct were collectively the highest for police officer dismissals. Of the 397 reasons recorded for police officer dismissal, there were 31 instances recorded of abuse of position for sexual purpose, 33 instances recorded of sexual offences or misconduct, and 1 instance recorded of rape.

Home Office analysis of police misconduct data

Data collected by the Home Office as a part of this review includes information on the volume and outcome of misconduct hearings (including accelerated hearings) heard under the Police (Conduct) Regulations 2020[footnote 43], by IOPC allegation type. When a complaint, conduct matter or recordable conduct matter occurs, IOPC allegation categories are used to capture the nature of the conduct which occurred. Appendix A of the IOPC’s guidance on capturing data about police complaints contains a full description of the categories and sub-categories that make up the framework.

An officer may face a case to answer for multiple allegations, across multiple allegation categories at a single misconduct proceeding. Analysis of this data shows that between 1 February 2020 and 31 January 2023, 79 officers were referred to a misconduct hearing as a result of at least one allegation of ‘sexual misconduct’. Of these officers, 92% received an overall finding of gross misconduct, amongst the highest rates when looking at the 11 IOPC allegation types and above the rate seen amongst all officers (89%).

Of those officers facing hearings involving at least one allegation of ‘sexual misconduct’, where gross misconduct has been found, 89% were dismissed, compared with 87% seen across all hearings and accelerated hearings during this period. Figure 1 shows the proportion of officers found to have committed gross misconduct who were subsequently dismissed, by IOPC allegation type.

Hearings involving at least one allegation of ‘abuse of position or corruption’ saw the highest rate of dismissal - 93% of officers found to have committed gross misconduct were dismissed. ‘Abuse of position or corruption’ primarily includes cases of abuse of position for sexual purpose and for the purpose of pursuing an inappropriate emotional relationship.

Figure 1: Proportion of officers found to have committed gross misconduct who were subsequently dismissed, by IOPC allegation category

| Category | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Abuse of position or corruption (72) | 93 |

| Sexual conduct (73) | 89 |

| Discreditable conduct (383) | 88 |

| Access and or disclosure of information (82) | 88 |

| Other (52) | 86 |

| Police powers, policies and procedures (40) | 83 |

| Discriminatory behaviour (37) | 81 |

| Delivery of duties and service (37) | 78 |

| Individual behaviours (64) | 77 |

| All officers | 87 |

Notes:

-

Includes cases handled under the Police (Conduct) regulations 2020 only.

-

Includes cases finalised between 1 February 2020 and 31 January 2023.

-

The number in brackets represent the number of officers found to have committed gross misconduct.

-

Excludes cases with an allegation of ‘handling of, or damage to, property or premise’ and ‘use of police vehicles’ due to low numbers.

A lower proportion of officers (when compared with cases involving ‘abuse of position’ or ‘sexual conduct’) facing at least one allegation of ‘discriminatory behaviour’ were found to have committed gross misconduct (84%) when compared with all officers referred to hearings (89%), though the overall number facing hearings for ‘discriminatory behaviour’ was relatively low (44). Of the 37 officers who attended a hearing for at least one allegation of ‘discriminatory behaviour’ and were found to have committed gross misconduct, 81% were subsequently dismissed (compared with 87% across all officers). 28 out of the 37 officers saw at least one allegation of racial discrimination, with the remaining cases including allegations of discrimination based on sex or sexual orientation.

Officers attending a hearing for at least one allegation of ‘individual behaviours’, which includes language, actions and behaviour that are not discriminatory saw the lowest dismissal rate when gross misconduct had been found (77%).

1.3 Limitations

Where an officer has been referred to a hearing as a result of multiple allegations, spanning multiple allegation types, it is not possible to determine from the data which allegations individually constituted gross misconduct or resulted in the dismissal of the officer. For the purpose of this analysis, where a hearing covers multiple allegations, the most severe misconduct finding and outcome are used.

Some allegation types have a small number of cases recorded that were referred to hearings. Differences between groups therefore may be exaggerated by small numbers. For further information see Annex B of this report.

The category ‘discreditable conduct’, which is the largest category by some margin, is a fairly broad category including behaviours that occur while not in the execution of a police officer’s duty and may therefore cover a variety of behaviours. The NPCC’s VAWG performance and insights report observes that it “is highly likely that the use of discreditable conduct as a category to capture inappropriate sexual behaviour or domestic abuse means that the proportion of allegations relating to these threats are higher than identified.”[footnote 44]

A “national factors” framework has been introduced to capture the situational context of an allegation to provide further information about the nature of complaints, including domestic or gender abuse and VAWG. These factors have been used in the NPCC VAWG analysis, however as new fields in the data, are currently not complete for all allegations. Research on the outcome of cases by national factor are therefore based on relatively small samples. We anticipate that reporting and data quality will improve over time, and understand that there is ongoing work by the NPCC to review and improve data being collected.

HMICFRS’ November 2022 inspection report on vetting, misconduct and misogyny[footnote 45] recommended that the NPCC and IOPC should agree a definition of ‘prejudicial and improper behaviour’ and devise a means of flagging it on databases used to record complaints and misconduct. For its inspection, HMICFRS defined ‘prejudicial and improper behaviour’ as ‘any attitude and/or behaviour demonstrated by a police officer or police staff that could be reasonably considered to reveal misogyny, sexism, antipathy towards women or be an indication of, or precursor to, abuse of position for a sexual purpose’. We understand this work is progressing and recognise that it should further improve the depth of data available.

1.4 Recommendations

It is clear that, in more recent years, there has been greater recognition in policing that misconduct cases involving sexual misconduct, VAWG and discrimination should be taken extremely seriously, and indeed, data analysed for our review shows that dismissal rates for sexual misconduct are high.

There have been concerted efforts to reinforce this message to forces, including through the College of Policing’s aforementioned Guidance on Outcomes in Police Misconduct Proceedings, as well as the NPCC’s work to respond to police-perpetrated abuse under its VAWG national framework for delivery[footnote 46]. We expect that given the relative recency of some of this work, case handling and outcomes will further improve as approaches are embedded.

The data considered for our review does suggest some differences between outcomes for different types of misconduct. Lower proportions of officers facing allegations of discriminatory behaviour (compared to those facing sexual misconduct, for example) were found to have committed gross misconduct and dismissed. Whilst such outcomes might be explained by the relative severity of offences, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the consistency of decision-making (both for finding gross misconduct and for sanctioning dismissal) based on the research and data we have considered overall in our review. Again, the use of the College’s guidance is important for ensuring greater consistency. We also note the work of the Mayor’s Office for Crime and Policing (MOPAC) and other PCC offices, who are providing holistic training for those who sit on panels. It is crucial that all panel members are provided thorough training, including on issues which significantly impact on public confidence in the police, such as discrimination and VAWG. This will remain important for the reformed panels proposed in chapter 4.

Where there is clearer evidence is around concerns with regards to the standards and consistency of case-handling. Baroness Casey’s interim report on misconduct in the MPS, published in October 2022[footnote 47], highlighted a broad range of issues with the MPS’ Directorate of Professional Standards and Professional Standards Units. Similarly, in its November 2022 inspection report[footnote 48], HMICFRS said that in the past decade:

a series of reports should have alerted forces that some of them were not properly equipped to prevent and investigate misogynistic and predatory behaviour. We could draw similar conclusions about racism, dishonesty, and other forms of corruption.

The report also raised concerns about the standards and consistency of decision-making, commenting that “initial assessments by some appropriate authorities reveal leniency, apathy and too much tolerance of prejudicial and improper behaviour”. The report noted several cases which were assessed by the Appropriate Authority (AA)[footnote 49] at the outset as not being misconduct, or as lower-level misconduct, which HMICFRS considered to be gross misconduct. None of the forces included in the inspection used any kind of quality assurance process for AA decisions.

For those officers who work in other specialist or high-harm areas of policing, there are rightly accreditation schemes in place, including the Specialist Child Abuse Investigators Development Programme (SCAIDP), Specialist Sexual Assault Investigators Development Programme (SSAIDP) and the National Police Firearms Training Curriculum (NPFTC). These schemes not only provide officers with the specialist knowledge they need to perform their roles, but they professionalise those areas of policing and provide a level of national consistency in decision-making.

The College of Policing has developed, and delivered, a high-quality training course for both professional standards investigators and AAs, but it is not a requirement of the role and there is no in-force assessment to ensure that officers have developed the appropriate knowledge, skills and experience required. It is important for the confidence of the public and the workforce, that investment is made in PSD investigators and decision-makers and we consider accreditation for those working in professional standards to be an important step towards improving standards and consistency in the police discipline system.

Recommendation 1

The College of Policing should consider developing an accreditation programme for professional standards investigators.

Term 2: Disproportionality in dismissals

Assess whether there is disproportionality in dismissals and, if so, examine the potential causes.

2.1 Introduction

Trust and confidence in policing requires a transparent and effective disciplinary system. The system must ensure that those officers who fall seriously below the standards and professional behaviour expected of them are dealt with robustly. The police misconduct system must also reassure the public, police officers and members of police staff that the process is functioning fairly and in accordance with the rules set out.

Where disproportionality in the system exists, the policing sector must seek to understand why, and consider what measures need to be taken to cement fairness and professionalism, so everyone can trust the system’s outcomes, regardless of their background.

Though research into disproportionality in the dismissals system across all protected groups is limited, there have been a number of reports in recent years completed by the policing sector, including the NPCC, which have been considered by this review[footnote 50]. The Government also welcomes the data and feedback provided by forces and stakeholders on this important issue.

Previous reports on disproportionality primarily focused on ethnic groups where historically such disproportionality exists. However, one study conducted by the London Policing Ethics Panel in 2021[footnote 51] studied MPS data, finding that men are over-represented in both special case hearings (since the introduction of the 2020 regulations known as accelerated hearings) and misconduct hearings. The same study found that female officers in these hearings had a higher number of prior disciplinaries than male counterparts.

Those in special case hearings were also found to be younger, and have fewer years of service, than the MPS average. This reflects the importance of considering other demographic trends and, as part of this review, we tried to consider, where possible, other protected characteristics such as gender and sexuality. However, it is clear that data remains limited, and this is discussed in the ‘limitations’ section of this chapter. Indeed, the review received reflections from a number of forces about this issue, with one force Professional Standards Department (PSD) noting that “it must be recognised that not all protected characteristics are recorded within our systems, such as sexual orientation and disability (in some cases)”.

2.2 Findings from previous reports

The NPCC carried out research in 2019 to understand disproportionality in police complaint and misconduct cases for black, Asian and ethnic minority police officers and staff, which was overseen by, now retired, Deputy Chief Constable Phil Cain[footnote 52] (Cain Report). The report provides a substantive evidence base, findings and a series of recommendations to tackle disparities faced by police officers and staff from ethnic minority backgrounds, including on potentially why instances of disproportionality occur.

The Cain Report found that, despite limitations due to data quality issues and small sample sizes, there was evidence of race disproportionality in the earlier stages of police complaints and conduct processes. However, it recognised that the absence of any evidence at the time for ethnic disparities at the later stages of complaint and conduct processes did not necessarily mean that disproportionality did not exist at these stages. The report made a number of key findings, including:

-

A failure of supervisors to deal with low level matters at the earliest opportunity, leading to a disproportionate amount of internal conduct allegations against black, Asian and ethnic minority officers being assessed by PSDs;

-

For black, Asian and ethnic minority officers subject to a misconduct investigation, the final outcome is significantly more likely to result in low-level or no sanction outcomes when compared with their white colleagues; and

-

A significantly higher proportion of conduct allegations for white officers were assessed as management action, misconduct or gross misconduct compared to those for officers from a black, Asian and ethnic minority background.

Further research commissioned by the NPCC[footnote 53] found that at a national level between October 2019 and September 2020, when compared to a white officer, black, Asian and ethnic minority officers were:

-

1.39 times more likely to be subject of a conduct related investigation;

-

1.26 times more likely to be subject of a case to answer determination;

-

1.6 times more likely to be dismissed; and

-

1.3 times more likely to receive either a written warning or final written warning.

Officers from a black, Asian and ethnic minority background were significantly more likely than a white officer to receive one of the lesser, advice-based sanctions, and were 1.6 times more likely to have their case not proven at hearing.

The Cain Report suggested that some black, Asian and ethnic minority officers have been disproportionately subjected to an unnecessary misconduct investigation and this experience is likely to have an impact on the health, reputation, career progression and even community of ethnic minority officers. The NPCC[footnote 54] has suggested that more focus should be put on the ‘probity and proportionality of a case journey rather than the outcome’. It is important to note that the NPCC research only considered 12 months of data, which can fluctuate across years, and resulted in very small sample sizes in some cases.

It is also important to highlight that research considering data on disproportionality within the misconduct system and proceedings tends to be approached in slightly different ways, adopt different methodologies and may not always be comparable.

Other research has also considered the reasons for disproportionality. As mentioned earlier in this section, it has been found that there has been a reluctance of supervisors to address low-level incidents[footnote 55]. Research conducted by MOPAC identified potential causes via academic theories including a fear of being labelled racist. [footnote 56]. This fear from supervisors may result in low-level incidents, which could be resolved through informal conversations, going uncorrected and reaching the stage where formal action is required.

Smith, Johnson and Roberts (2014) suggested that supervisors may escalate low-level incidents, as they are concerned that their line managers may take a greater interest in cases involving ethnic minority officers and their decisions were more likely to be scrutinised[footnote 57]. This study also found ethnic minority officers who had experienced misconduct investigations and admitted to wrongdoing felt that white officers were more likely to be dealt with informally for similar behaviour. The Cain Report suggested that these issues and perceived differences in how cases are handled have led ethnic minority officers to feel that white officers are treated more favourably[footnote 58]. It has also contributed to a perception that the threshold for breaches of professional standards appear lower for officers from ethnic minority backgrounds.

Major-General Chapman highlighted that police appear to have problems managing difference in their workforce, and what could be dealt with informally ends up as disciplinary proceedings against officers from black and minority ethnic backgrounds[footnote 59]. The Cain Report found that ethnic minority officers have reported a lack of cultural competence during PSD investigations, where they experienced inconsistencies and a failure of PSDs to consider culture when conducting investigations[footnote 60]. Within this report, a survey of PSDs also found inconsistencies in their approach on use of guidance and working practices to understand cultural difference for allegations[footnote 61].

Research conducted by MOPAC highlighted that implicit bias, both conscious and unconscious, may be a factor contributing to disproportionality[footnote 62]. Smith, Johnson and Roberts (2014) conducted interviews with officers and identified cases of misconduct proceedings being used to disrupt the career development of black, Asian, and ethnic minority officers, and to deter them from making allegations against other officers[footnote 63]. With consideration to the MPS specifically, the Casey Review in 2023 found black and Asian officers and staff were far more likely than their white colleagues to raise a grievance[footnote 64]. In particular, black officers and staff were found to be twice as likely as their white colleagues to raise a grievance.

Positive action has been identified in response to the Cain Report, including from PSDs who have introduced processes to better understand the reasons for any black, Asian and ethnic minority officer disproportionality. For example, focused PSD training and development, use of critical friends in assessments and case to answer decisions, effective force level scrutiny boards and enhanced PSD analysis of disproportionality.

The NPCC National Complaints and Misconduct Working Group (NCMWG) has provided support for decision-makers regarding culture awareness and training which is reported to reduce the number of cases going through to disciplinary proceedings.

The Government welcomes the work undertaken by the NPCC and wider policing sector to tackle the issues identified above, including on better policing training, guidance published and improved data.

Further work is taking place today. For example, the Police Race Action Plan[footnote 65], as of August 2023, seeks to take action to reduce racial disparities in misconduct and complaints processes and improve support to black officers and staff. This includes developing a fair and equitable misconduct and complaints process from initial assessment through to investigation and outcome. However, instances of disparities continue to persist in aspects of the discipline system. As identified in the Casey review’s interim report on misconduct[footnote 66], there is both racial disproportionality and disparity throughout the system in the MPS. The review identified that in the year ending 31 March 2022, black officers and staff were 81% more likely than their white counterparts to have misconduct allegations brought against them and more likely to have allegations against them substantiated (meaning there was a case to answer). Though it is important to recognise that the Casey Review was focused specifically on the MPS, and so it would not necessarily be appropriate to directly compare to other reports, such as the Cain report, which utilises differing data sources.

Research conducted by MOPAC has also analysed misconduct allegations made against MPS officers, considering cases between 2010 and 2015[footnote 67]. As with the Casey Review, it was found that black, Asian and ethnic minority officers were more likely subject to a misconduct allegation and that these allegations were more likely to be substantiated (meaning there was a case to answer). The higher rate of misconduct allegations was not associated with length of service, age of officer, type of allegation or whether the officer was on or off duty. Despite black, Asian, and ethnic minority officers being disproportionately represented in misconduct allegations, there was no disproportionality in the number of public complaints made against officers from ethnic minority groups compared to white officers. This highlights that disparity seems to come from internal misconduct cases raised by officers.

The Casey Review also touched on the use of Regulation 13, in terms of the disproportionality in its use. The review analysed a dataset of the 619 uses of Regulation 13 in the MPS between April 2018 to March 2022. It was found that disproportionate numbers of female, black and ethnic minority officers in their probationary period resigned in this period. Ethnic disproportionality in the use of Regulation 13 was also found to be much more pronounced than in the misconduct system. Black and Asian probationers were twice as likely to have a Regulation 13 case raised against them than their white colleagues.

Within the 2018-2022 cohort of police constables and detective constables with 2 or less years of service, black officers were 126% more likely to be subject to a Regulation 13 case than white officers. Asian officers were 123% more likely and officers from mixed ethnicity groups were 50% more likely.

Research conducted by Sherman et al. in 2023[footnote 68] sought to compare the probability of police officer dismissals in London between misconduct hearings chaired by senior officers and LQCs. It concluded that, in the 22 months prior to hearings being chaired by LQCs, and the first 22 months after LQCs were introduced, the probability of dismissal for officers in LQC-chaired hearings was substantially lower than in senior officer-chaired hearings. A larger difference in the proportion of black, Asian and minority ethnic and white officers dismissed was seen for cases heard at LQC-chaired hearings compared with senior officer-chaired hearings. The research shows that black, Asian and minority ethnic officers were 115% more likely than white officers to be dismissed at LQC-chaired hearings (58% of black, Asian and minority ethnic officers were dismissed compared with 27% of white officers). By comparison, at senior officer-chaired hearings, black, Asian and minority ethnic officers were 13% more likely to be dismissed than white officers (52% of black, Asian and minority ethnic officers were dismissed compared with 46% of white officers). We note that this was a descriptive analysis of the differences in dismissal rates over a specific sample size (19 LQC-chaired hearings involving black, Asian and minority ethnic officers took place over this period), and the analysis is unable to fully differentiate cases proven to amount to gross misconduct with those not.

2.3 Data

A number of stakeholders who provided evidence to our review reflected the findings made in the Cain Report and other research, particularly stressing the importance of early intervention and appropriate management of low-level conduct allegations by supervisors.

Others highlighted steps that have been taken to address disproportionality, with one force noting that its PSD “works closely with our Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) teams throughout [its] investigations, seeking advice and guidance as well as offering advice to the panel should they need it where there is a diversity or inclusion matter. Data on all aspects of PSD matters is regularly examined by our Strategic EDI Board, which is chaired by the Chief Constable”.

One IPM noted a concern that “not all officers receive the occupational health support and psychiatric assessment that should take place way before the cases come to the hearing panel”. Each force, as part of ensuring the wellbeing of their staff, should continue to ensure each officer has access to adequate support.

Home Office analysis of police misconduct data

Data collected by the Home Office as a part of this review includes information on the protected characteristics of officers referred to proceedings where the case was finalised between 1 April 2015 and 31 March 2022. The data includes officers referred to both hearings and accelerated hearings (or special case hearings under the previous regulations). A series of accompanying data tables have been published alongside this report providing breakdown of trends by ethnicity, sex and age.

The available data means it has not been possible to determine from the data which hearings were chaired by LQCs and which by senior officers (see the limitations section of Annex B for further information).

Ethnicity

Over this period, 325 ethnic minority officers (excluding white minorities) were referred to a hearing or accelerated hearing, representing 12.1% of all officers (where ethnicity is known). This compares with 2,355 white officers referred to a hearing or accelerated hearing.

As a proportion of all officers in post, between 0.4% and 0.6% of the overall ethnic minority workforce (equivalent to 4 to 6 in every 1,000 ethnic minority officers) are referred to a hearing or accelerated hearing each year. This is consistently higher than amongst white officers, where between 0.2% and 0.3% of all officers (2 to 3 in every 1,000 white officers) are referred to hearings.

For example, in the latest year (ending 31 March 2022), 15.0% of all officers attending a hearing or accelerated hearing where ethnicity was identified were ethnic minorities (excluding white minorities). By comparison, in the total workforce ethnic minority officers (excluding white minorities) make up 8.3% of officers (including special constables) as at 31 March 2022. This is equivalent to 63 officers in every 10,000 attending a hearing compared with 30 in every 10,000 for white officers.

Figure 2: Proportion of officers in post referred to a hearing or accelerated hearing, by ethnicity

| Financial year ending 1 March | White | Ethnic Minority |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 0.23% | 0.39% |

| 2017 | 0.3% | 0.42% |

| 2018 | 0.25% | 0.6% |

| 2019 | 0.29% | 0.51% |

| 2020 | 0.29% | 0.57% |

| 2021 | 0.28% | 0.44% |

| 2022 | 0.3% | 0.63% |

When considering officers dismissed, since the year ending 31 March 2016, 64% of white officers attending a hearing or accelerated hearing were dismissed, compared with 72% of ethnic minority officers. When looking at each year individually ethnic minority officers have seen a higher dismissal rate consistently. However, due to the relatively small number of ethnic minority officers dismissed each year (generally between 25 and 50), comparisons should be made with caution.

Since 2019, the data allows us to consider cases by misconduct finding level. Between 1 April 2019 and 31 January 2023, where a misconduct finding level has been recorded, 87% of officers referred to misconduct hearings were found to have committed gross misconduct. Similar levels are seen between the white and ethnic minority groups (86.4% and 87.2% respectively).

Looking at the outcome of officers who received a finding of gross misconduct, 85% of ethnic minorities were dismissed, compared with 81% of white officers.

In summary, since April 2019, ethnic minority (excluding white minorities) officers were on average 1.87 times more likely to face a hearing than white officers. Among these who faced a hearing, a similar proportion were found to have committed gross misconduct, though ethnic minority officers were slightly (1.04 times) more likely to be subsequently dismissed.

As a proportion of the workforce 49 in every 10,000 ethnic minority officers were dismissed in the year ending 31 March 2022, compared with 22 in every 10,000 white officers. This difference is largely as a result of higher proportions of ethnic minority officers referred to hearings, though as described previously, a small difference in dismissal rate upon the finding of gross misconduct was also seen.

Sex

Data has also been collected on the sex of officers referred to misconduct hearings. As a proportion of the overall workforce, between 0.13% and 0.19% of all female officers were referred to a hearing each year, consistently lower than the 0.32% to 0.42% seen amongst male officers. In the year ending 31 March 2022, 15.6% of the officers who attended a hearing or accelerated hearing were female, lower than the proportion of all officers and specials who were female (33.1% at the end of the previous financial year).

When considering officers dismissed, since the year ending 31 March 2016, 65% of female officers attending a hearing or accelerated hearing were dismissed, the same as the dismissals rate seen amongst male officers. In each individual year there are some differences between the male and female groups, however due to the relatively small number of female officers referred to misconduct hearings, the dismissal rate can fluctuate.

Between 1 April 2019 and 31 January 2023, where a misconduct finding level has been recorded, 87.2% of female officers referred to misconduct hearings were found to have committed gross misconduct. A similar proportion was seen amongst male officers (86.5%).

Looking at the outcome of officers who received a finding of gross misconduct, 79% of females were dismissed, compared with 83% of male officers.

Age

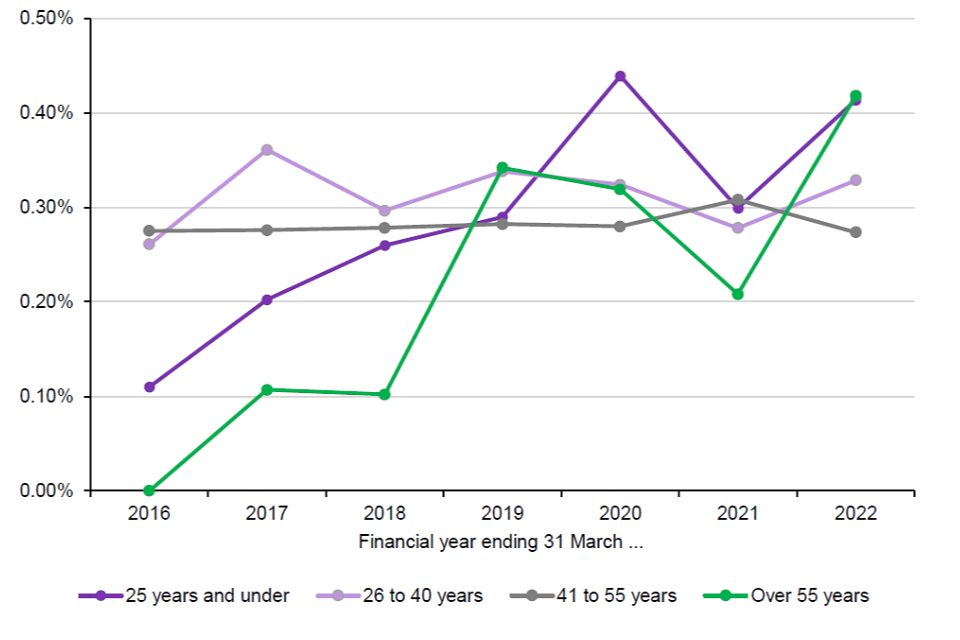

In the year ending March 2022, 0.41% of all officers aged 25 or under faced a misconduct hearing or accelerated hearing (equivalent to 41 in every 10,000 officers aged 25 or under). This compares with 33 in every 10,000 officers aged 26 to 40 and 27 in every 10,000 officers aged 41 to 55.

A rate similar to that of officers aged 25 or under was seen for officers aged over 55 (42 in 10,000), however this is based on a very small number of proceedings as this group only represent 2% of the workforce.

The proportion of officers aged 25 or under, or aged over 55, who have faced misconduct hearings has increased in recent years, whilst proportions of officers aged between 26 and 55 have remained more constant.

Figure 3: Proportion of officers in post referred to a hearing or accelerated hearing

The graph shows the proportion of officers in post referred to a hearing or accelerated hearing for the financial years, ending 1 March, 2016 to 2022,

25 years and under: rise from just over 0.1% to over 04.%.

26 to 40 years: fluctuates between 0.25% and 0.35%.

41 to 55 years: fairly stable at around 0.28%.

Over 55 years: rises from 0 in 2016 to 0.34 in 2019, falling in 2021 and rising to over 0.4% in 2022.

When considering dismissals, between 1 April 2015 and 31 March 2022, there is some difference between the proportion of officers facing a hearing who received an outcome of dismissal by age group. Of officers aged 25 years and under, 73% were dismissed, compared with 64% for officers aged 26 to 40 and 41 to 55, and 69% for officers aged over 55.

Since 2019, the data allows us to consider cases by misconduct finding level. Between 31 April 2019 and 31 January 2023, where a misconduct finding level has been recorded, 87% of officers referred to misconduct hearings were found to have committed gross misconduct.

A higher proportion of officers 25 years and under received a gross misconduct finding level (91%) when compared with other age groups (85% for officers aged 26 to 40, 87% for officers aged 41 to 55, and 85% for officers aged over 55).

Where gross misconduct has been found, a greater proportion of officers aged 25 and under and over 55 were dismissed (both 88% and 89% respectively) when compared with officers aged 26 to 40 and 41 to 55 years (83% and 79% respectively).

In September 2019, the Government made a manifesto commitment to recruit an additional 20,000 police officers[footnote 69] in England and Wales by 31 March 2023. This “uplift programme”, saw over 46,000 new police officer recruits between November 2019 and 31 March 2023.

As such there has been an increase in the volume and proportion of officers who are both younger and have fewer years in service, when compared to before the uplift programme. Data published as a part of the Police Officer Uplift statistics[footnote 70] show that around 13% of officers were aged 25 or under as at 31 March 2023, an increase on 7% as at 31 March 2019, before the programme began.

It is therefore difficult to separate any effect of length of service and of age on recent trends of decisions made at a misconduct hearing. Similarly, consideration should be given to the increase in proportions of less experienced ethnic minority officers and female officers in recent years.

Analysis of data collected by the Home Office as a part of this review shows that the number of cases referred to hearings involving officers (excluding specials) with less than 5 years’ service has been steadily growing since 2016, becoming the largest group since the year ending 31 March 2019.

This year-on-year increase has been broadly in-line with increases in the volume of officers in post with less than 5 years’ service. This can be seen by considering the proportion of all officers with less than 5 years’ service that were referred to a hearing or accelerated, which remained relatively stable (between 37 in 10,000 and 41 in 10,000) between the years ending March 2016 and March 2021.

An increase was however seen in the year ending 31 March 2022 when 47 in every 10,000 officers with less than 5 years’ service were referred to a hearing. This was higher compared with other length of service groups:

-

31 in every 10,000 with between 5 and less than 10 years’ service

-

35 in every 10,000 with between 10 and less than 15 years’ service

-

29 in every 10,000 with between 15 and less than 20 years’ service

-

18 in every 10,000 with more than 20 years’ service

Officers with less than 5 years’ service, also saw the highest rate of dismissal where gross misconduct was found (86%). By comparison, when found to have committed gross misconduct:

-

78% of officers with between 5 and less than 10 years’ service were dismissed

-

85% of officers with between 10 and less than 15 years’ service were dismissed

-

77% of officers with between 15 and less than 20 years’ service were dismissed

-

77% of officers with more than 20 years’ service were dismissed

2.4 Limitations

As mentioned above, there are limitations in the data collected and provided by forces which means we only have sufficient enough data to comment on the protected characteristics of ethnicity, sex and age.

The white male group makes up around 60% of all officers in England and Wales as at 31 March 2022. As such, the volume of officers from minority groups referred to hearings is comparatively low each year. Caution should therefore be taken when comparing groups across a single year as differences in percentage rates between groups may equate to a small number of cases. Due to the low number of cases referred to hearings involving officers from minority groups, our analysis has not considered outcomes of hearings and accelerated (previously special case) hearings separately.

Prior to 2019, data on misconduct finding level is largely incomplete. Comparisons of dismissal rates between groups should therefore be made with caution as the severity of cases may not be comparable. From 2019 onwards we are able to compare dismissal rates where gross misconduct has been proven, which presents a truer comparison of outcome where a consistent threshold of severity has been met.

A full list of limitations can be found in Annex B of this report.

2.5 Recommendations

As highlighted in the ‘limitations’ section above, our analysis was unable to make substantive conclusions about disproportionality pertaining to protected characteristics other than ethnicity, age, and sex.

It is recognised from the data we have available that there are disparities in some aspects of the dismissals process in relation to race. Though caution should be given due to the smaller survey size, when considering officers dismissed, since the year ending 31 March 2016, 64% of white officers attending a hearing or accelerated hearing were dismissed, compared with 72% of ethnic minority officers. Previous reports, including the Cain Report, also identified signs of disparity in relation to race and a number of key findings, including a failure of supervisors to deal with low level matters at the earliest opportunity. We welcome the work being taken by the policing sector to understand why these disparities may exist and putting in measures to improve policing culture.

In terms of age, data suggests that officers aged 25 years and under are more likely to face disparities in aspects of the dismissal system. For example, since April 2019, 88% of officers aged 25 years and under found to have committed gross misconduct were dismissed this is above levels seen amongst the 26 to 40 years and 41 to 55 years age groups (83% and 79% respectively). However, we recognise that the data available includes small sample sizes and so comparison to other age ranges must be seen with some caution.

For factors such as sex, there are indications of disproportionality at certain points in the process. For example, data suggests that men are more likely to be referred to misconduct hearings, but that in terms of outcomes, there is little difference between the proportion of men and women found to have committed gross misconduct.

However, we recognise that data in all factors is limited, and indeed, a number of stakeholders who provided evidence to our review commented that the lack of consistent data available on disproportionality throughout the dismissals system resulted in an inability to engage meaningfully on the question of disproportionality.

The Government remains committed to eliminating instances of discrimination and promoting equality of opportunity and fairness for all police officers and staff. To ensure meaningful, targeted action, there must be a rigorous and well evidenced dataset. Therefore, this report’s conclusions and recommendations will seek to improve the data available, and to bring together action being taken across the policing sector to tackle these disparities and ensure the misconduct system is fair, transparent and effective.

Since 2022, the Home Office has published an annual statistical publication covering police misconduct. These statistics currently include high-level information on the overall number of complaints and internal conduct matter allegations by the ethnicity and sex of the officer or member of police staff involved. As experimental statistics, these remain under development and present an opportunity to provide increased transparency on other protected characteristics as well as exploring disproportionality at different stages of the misconduct process.

As discussed, we welcome the work the policing sector is already undertaking to explain why such disparities exist and to put in place measures to tackle disproportionality. The action below will therefore also seek to ensure meaningful data can help explain disparities, consider what more can be done to support forces in data collection and where needed, support forces to tackle disparities.

Recommendation 2

To give greater clarity and context to misconduct and dismissals data, and reassure the public about its use, the Government, with the policing sector, will consider the way data is reported, where there are possible gaps, and how to improve collection to enable more meaningful data across England and Wales.

Whilst we have been able to comment on the existence of disproportionality with regards mainly to ethnicity, and have also considered sex and age, there is limited evidence on a person’s experiences from the perspective of intersectionality. Factors in different combinations (such as ethnicity, sex, age, sexuality and disability) may also impact on an individual’s experience of the disciplinary system.

Recommendation 3

The Home Office, with policing partners, should carry out multi-variate analysis to identify any disproportionality related to intersectional characteristics.

With the delivery of a multi-variate analysis, and measures put in place to provide greater clarity and context to misconduct and dismissals data, the Government will use the results to work with the policing sector, staff associations and other key stakeholders to outline why such disparity exists across protected characteristics and consider a range of measures to mitigate them within policing.

Term 3: Trends in the use of sanctions

Establish any trends in the use of sanctions at both hearings and accelerated hearings – in particular the levels of dismissals.

3.1 Introduction

This review was established, in part, due to concerns around possible lenient sanctions being applied at misconduct proceedings – where officers found to have committed gross misconduct by independent misconduct panels, or by Chief Constables at accelerated hearings, have been issued with alternative sanctions and not dismissed.

Some have linked a potential increase in this perceived leniency, with the introduction of LQCs in 2016. Baroness Casey’s interim findings of her review into the MPS, references a fall in dismissals which “coincides with the 2016 introduction of Legally Qualified Chairs” but urges caution, stating there could be other causes of such a decline.

In fact, as part of her evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee on 22 March 2023[footnote 71], Baroness Casey also highlighted that outcomes such as these can also occur when the police make the decision themselves.

For example, when a police sergeant has been convicted of a criminal offence of indecent exposure for doing a rather graphic version of that on a public train, they can keep him in the force as opposed to making the decision to sack him. On so many levels they close in on themselves, and they think they are untouchable.