Planning and Preparing for Later Life

Updated 8 November 2022

Planning and Preparing for Later Life

Findings from the 2020/21 survey

Publication date June 2022

DWP research report no. 1008.

A report of research carried out by National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2022.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on GOV.UK

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published June 2022.

ISBN 978-1-78659-393-1

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive Summary

The question of whether and how people are planning for retirement is becoming ever more important as people live longer and have greater freedom over when and how they retire and take their pensions. Planning and Preparing for Later Life (PPLL) is a new, nationally representative survey of 2,655 40-75 year olds commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions to provide evidence on how far individuals are able to make well informed choices about retirement and whether they will be in a position to enjoy financial security when they retire.

The survey includes findings on:

- income adequacy in retirement. Whilst most people had started saving for retirement, nearly one in four (24%) of 40-75 year olds did not have a private pension and 16% had not yet started saving for retirement. Those that had started saving did not always know if what they had saved would give them the income they would need income in retirement. Only 23% of people not yet retired said they had a very good idea of the income they would need in retirement

- how people had taken advantage of Pensions Freedoms to access their Defined Contribution (DC) pensions. Over half (56%) of 60-65 year olds with a DC pension had accessed at least one pension. Nearly three in ten people (29%) who had accessed a DC pension had not received information, advice or guidance from their pension provider, Pension Wise or a financial advisor. Most people (67%) chose to take a cash lump sum with some doing so to meet short-term income needs including covering living costs or paying off debts. Many people (59%) who accessed their DC pension before State Pension age (SPa) had no other private pension provision, making their decisions about how to access their pension particularly important

- people’s knowledge of recent changes to the State Pension. Although not everyone correctly identified their SPa, only 20% of people below SPa thought they would be able to draw their State Pension earlier than is the case. People who had used the Check your State Pension website were more likely to correctly identify their SPa. However, people for whom the State Pension was their only source of income in retirement were least likely to have used the site and were among the least knowledgeable

- what would make it easier for people to continue working later in life. Most people (62%) who had not yet retired expected to continue in paid work beyond their ideal retirement age. Key factors for helping them to work longer – and fund their retirement - were the ability to work flexibly and the potential to work fewer hours as they approach retirement

- experiences of planning for retirement among the self-employed. The self-employed were less likely to have started saving for retirement, less likely to have a pension (65%), and to be more reliant on sources of non-pension income to fund retirement. They expected to retire later than employees for financial reasons but also because they wanted to retire later, enjoying the flexibility their self-employment afforded and with a preference for remaining self-employed

Acknowledgements

This research was commissioned by Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) and was carried out by the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) in collaboration with the Institute for Employment Studies and Pensions Policy Institute. The authors would like to thank Hannah McLennan, Sarah Kate O’Grady and Rhian Eveleigh at DWP for their suggestions and encouragement throughout the project.

The successful delivery of the project at NatCen relied on input from a wide range of people, in particular project manager Emma Fenn, survey programmer Nafiis Boodhumeah, data managers Migle Aleksejunaite and Jessica Messling, statisticians James Yarde and Rebecca Steinbach, Telephone Unit manager Sonia Shirvington and all the interviewers working on the project. Researchers Alun Humphrey and Shane Howe also worked on the project and Emma Berteen, Jo D’ardenne, Natasha Phillips and Ruxandra Comanaru contributed to questionnaire development and cognitive testing.

Rosie Gloster from the Institute for Employment Studies and Daniela Silcock and Lauren Wilkinson from the Pensions Policy Institute provide invaluable advice at various stages of the project, especially around questionnaire design and reporting. Elizabeth Clery worked closely with NatCen on the design of the questionnaire.

Last but not least, we want to thank our respondents who gave up their time to take part in the survey.

Author details

Sarah Butt is a Research Director at NatCen and was the lead researcher on this study.

Victoria Ratti is a Senior Researcher at NatCen and contributed to analysis and reporting.

Benjamin Swannell is a Senior Researcher at NatCen and was involved in both the design of the survey and analysis and reporting.

Eleanor Woolfe is a Research Assistant at NatCen and contributed to analysis and reporting.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| 50 Plus | Choices This strategy builds on work done as part of the Fuller Working Lives initiative. It was developed in partnership with employers and provides recommendations around the retention and recruitment of older workers aged 50 and over. The strategy includes recommendations around encouraging flexible working and ensuring that older workers are given access to training, as well as encouraging active knowledge transfer between generations. Employers are also encouraged to provide retirement transition preparation for employees. |

| Accumulation | The phase during which a consumer saves into a pension pot during their working career to build up funds for retirement. |

| Annuity | A form of insurance policy that consumers can buy with their pension pot. This will typically provide the consumer with a guaranteed income for life, or for a fixed number of years. |

| Automatic enrolment | A legal requirement that every employer must automatically enrol its workers into a quantifying pension scheme subject to certain criteria. Employers have gradually enrolled all eligible workers into qualifying pension schemes between 2012 and 2018. |

| Decumulation | Commonly understood, decumulation means the process of converting pension savings into a retirement income. This refers to the process of using savings to provide income in a specific form (for example, converting pension savings into an annuity) or where the individual has reached a specific milestone e.g. a set retirement age for drawing down their pension. However, since the introduction of Pension Freedoms in 2015, decumulation can be defined more broadly as the process of converting or using pension savings to fund choice in later life. |

| Defined Benefit (DB) | A scheme in which the benefits are defined in the scheme rules and build up regardless of the contributions paid and investment returns. The benefits are most commonly related to members’ earnings at the point they leave the scheme or retire, and the length of their pensionable service. These are also known as ‘final salary’ or ‘salary-related’ schemes. DB benefits are guaranteed or underwritten by the sponsoring employer. |

| Defined Contribution (DC) | A scheme in which a member’s benefits are determined by the value of the pension fund. The value of the fund at any time depends on contributions and performance of investments. |

| Income Drawdown | Flexi-access income drawdown products involve investing a pension pot into a fund or funds which allow the consumer flexible access. The consumer can withdraw funds when they want and use this as an income. Income drawdown providers offer a range of different funds, with different investment objectives, risks, and levels of charges. |

| Pension Freedoms | In April 2015, the tax rules were changed to give people with DC pensions greater flexibility to access their pension savings. Individuals aged 55 and over were able to choose how and when they accessed their pension savings. These withdrawals count as income being taxed at marginal income tax rates rather than the previous rate of 55% (though tax-free lump sum continues to be available). To support their decisions, individuals have access to free and impartial guidance via the phone or face-to-face, through Pension Wise, to help them make the choices that reflect their needs in retirement. These include six options - leaving the pension pot untouched, purchasing an annuity, getting an adjustable income (Flexi Access Drawdown), taking cash in chunks (Uncrystallised Funds Pension Lump Sum), cashing in the whole pot in one go and mixing any of the above options. |

| Pension wake-up packs | This is a term used within the pensions industry to refer to the retirement options packs pension providers are required to send to people 4-6 months before their agreed pension age. Packs are aimed at ensuring people receive timely, relevant and adequate information about their retirement options to enable them to make an informed decision about accessing their pension savings. They have been in place since 1987. The Financial Conduct Authority introduced new one-page summary wake-up packs in November 2019. However, these only apply to contract-based i.e. personal pension schemes. |

| Pension Wise | A free and impartial service set up by the Government in 2015 offering guidance for people regarding Pension Freedoms introduced in the 2014 UK budget. Pension Wise guidance is now run by the Money and Pension Service. The service is available to people aged 50 years and over with a DC pension to help them understand what they can do with their pension pot(s). Guidance is delivered via telephone, face to face appointments or online. |

| State Pension Age (SPa) | The age at which an individual can claim their State Pension. |

| State Pension Amount | The amount received from the State Pension. The new State Pension (nSP) replaces the basic State Pension (bSP) and additional State Pension for men born after 6 April 1951 and women born after 6 April 1953. The full rate of the new State Pension was £175.20 per week in 2020/21. However, the amount an individual receives is based on their own National Insurance record. Transitional rules are in place for those who reach their State Pension age in the early years of the new State Pension. This means that they may receive an amount that is more than, less than or equal to the full rate of the new State Pension based on their National Insurance record. |

| The midlife MOT | A free online support tool to encourage more active planning by people in their 40s, 50s and 60s in the key areas of work and skills, health and wellbeing and finances. Employers are encouraged to promote the midlife MOT tool to their employees and to have follow-up conversations. |

Summary

The question of whether and how people are planning for retirement is one which is becoming ever more important. Increasing numbers of people are both reaching and living longer beyond State Pension age. Policy changes around retirement and pensions such as the abolition of the statutory retirement age in 2011 and the introduction of Pension Freedoms in 2015 give people greater freedom over when and how they retire and take their pension. This in turn puts more onus on individuals to take decisions about their retirement.

The Department for Work and Pensions commissioned Planning and Preparing for Later Life (PPLL) to provide evidence on how far individuals are able to make well informed choices about how and when to retire and whether they will be in a position to enjoy financial security when they do. PPLL is a new, nationally representative survey of 40-75 year olds in Great Britain. The survey had four main objectives:

- to provide evidence to support policy development around income adequacy in retirement

- to gather evidence to inform the 50 Plus: Choices strategy (previously Fuller Working Lives) specifically its focus on measures that allow and encourage people to stay in work for longer

- to understand the impact of the new pensions’ flexibilities on attitudes and behaviours around pension saving and planning for later life

- to develop the evidence base around the self-employed and planning for later life.

Data was collected from 2,655 individuals aged 40-75 interviewed via telephone between November 2020 and February 2021.

Fieldwork took place against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic. The survey was not designed to explore whether and how COVID-19 may have affected people’s plans for retirement. However, it is possible that the pandemic may have had an impact on people’s current circumstances and expectations for the future and that some findings may have been different had the survey been conducted 12 months earlier.

People’s financial preparedness for retirement

Most people had made at least some provision for ensuring they have an income in retirement. Sixty-three percent had started saving for retirement by their 30s whilst 55% of those not yet retired were currently saving into a pension. Around three in four (76%) of 40-75 year olds had a private pension.

Those currently on low incomes and/or not in employment are likely to be particularly financially vulnerable in retirement and may require further support. Only 48% of those not yet retired and on incomes less than £10,500 (many of whom would not meet the threshold for automatic enrolment) and 51% of those not in paid work had a private pension. Not being able to afford to make contributions was the most common reason given for not having a pension (cited by 53% of people without a pension). Those without a private pension were also less likely to have access to other sources of income to fund their retirement, such as savings or property and were particularly likely to be dependent on the State Pension.

People who had started saving for retirement had not necessarily thought in detail about how much income they will need in retirement or whether their current level of saving is sufficient to achieve that. Only 23% of people who had not yet retired said they had a very good idea of the income they would need in retirement whilst 16% could not say how much income they expected to receive in retirement. One in four people saving into a workplace pension did not know the rate of their contributions whilst one in five people with a Defined Contribution (DC) pension in accumulation did not know the size of any of their pension pots.

Nearly half (45%) of all private pension holders expected less than half of their income in retirement to come from their private pension(s), also relying on the State Pension and other sources of non-pension income such as savings or property. However, non-retirees may be placing too much expectation on sources of non-pension income. As many as 64% of non-retirees expected to use savings and investment in retirement compared with 53% of people who had fully retired who had used these sources. Similarly, 26% of non-retirees expected to use equity release and 22% expected to have income from an inheritance. The corresponding figures among fully retired respondents who had used these sources were 6% and 15%.

People’s response to Pension Freedoms

Following the introduction of Pensions Freedom legislation in 2015, people can now access their DC pensions at the age of 55 and have a range of options available to them regarding how to access their pension.

The majority of pension holders will be affected by Pension Freedoms in the future. Seventy-two percent of pension holders had a DC pension and 54% had only DC pensions with no Defined Benefit provision. These DC pension holders will include people auto-enrolled in workplace pensions who may not have previous experience of saving or investment and so who may particularly benefit from support in navigating the choices available to them.

Many people had taken advantage of Pension Freedoms to access their pension before they reach State Pension age (SPa). Fifty-seven percent of 60-65 year olds with a DC pension had accessed at least one pension. The median age at which DC pension pots were accessed was 60. Twenty-three percent of those 55+ who had accessed a DC pension were still doing some paid work.

Many people (59%) who chose to access their DC pension before their SPa did not have other private pension provision available. Most of these people (71%) were no longer in employment and so no longer had access to income from earnings. Depending on the choices these people make regarding their DC pension this potentially puts these people at risk of depleting their pension pot before the end of their retirement.

Most people who accessed a DC pension received information, advice or guidance from a financial advisor, their pension provider or Pension Wise before doing so (71%). Around one in eight (13%) had received no information, advice or guidance at all. A further one in six (16%) had received it but not from their pension provider or Pension Wise or a financial advisor. Where people had used these sources, they were generally positive about them; 76% of Pension Wise users said they were very or quite satisfied with the service.

When accessing their DC pension many people (67%) chose to take a cash lump sum. For some, this money was used to cover living costs (38% of pensions) or pay off debt (31%). People on low incomes, who were also less likely to have access to other sources of non-pension wealth in retirement, were particularly likely to have accessed their DC pension. However, using private pensions to meet short-term income needs may mean that people have reduced income later in life and are dependent on income from other sources, particularly the State Pension.

Nearly everyone (92%) who had taken a lump sum since 2015 said they were happy with this decision, including 66% who were very satisfied. However, whether this will change over time, as people experience the consequences of having cashed in some or all of their pension, will need to be reviewed.

The importance of the State Pension

Most people who have not yet retired (89%) expected to make use of the State Pension as a source of income in retirement. Only six percent of all 40-75 year olds expected the State Pension to be their only source of income in retirement. However, this figure rises to 24% of those without a private pension.

Two in five of those who had not yet retired (40%) expected to retire by the age of 65, which is below the current SPa. Expectations of “early” retirement were more common among higher earners who in turn are less likely to be depending on the State Pension to fund their retirement. However, 36% of people earning less than £10,500 expected to retire by the age of 65, potentially leaving this group – who were among the least likely to have a pension or other sources of income in retirement- without valuable income upon retirement.

Although not everyone was aware of recent changes in the SPa and how this might affect them, a majority (56%) correctly identified their SPa. Only 20% of people below SPa thought they would be able to draw their State Pension earlier than they will. Those who did underestimate their SPa did so by an average of 3 years.

People who had used the Check Your State Pension website to check their SPa or State Pension amount were more likely to give a correct answer. However, only around half of those below SPa (51%) reported that they had checked their retirement age whilst two in five (40%) had checked the amount of State Pension they would receive. People for whom the State Pension was the only source of income in retirement, and therefore for whom an awareness of what they would receive and when could be considered most important, were least likely to have checked details of their state pension and were among the least knowledgeable.

Supporting paid work in later life

Most people (62%) who had not yet retired expected to continue in paid work beyond their ideal retirement age with only one in four (26%) saying they expected to retire at their ideal age. More positively, only four percent of those not yet retired expected to retire before their ideal age. This compares with 31% of those already retired who had stopped work before their ideal age.

When asked what would help them keep working longer, key factors were the ability to work flexibly (mentioned by 44%) and the potential to work fewer hours as they approach retirement (52%). However, delivering on flexible working and reduced hours presents challenges for employers and policy makers. The evidence showed that access to flexible working hours varied significantly by income and occupation. Whilst many people wanted to reduce their hours as they approached retirement (54%), people who had already fully retired were less likely to say they had actually done this (34%).

Certain groups, including those with caring responsibilities or health concerns, may require additional support to continue working longer. These two groups were among the most likely to have requested a change in their working arrangements from their employer in the past five years (with 26% of carers and 35% of those rating their health less than good having done so). “Workplace adjustments for a health condition or disability”, rather than flexible working or reduced hours, was the most commonly cited factor among people in bad health when asked what would help them keep working longer.

Ensuring that workers continue to have access to training as they get older is also important. Although less likely to want training than their younger counterparts, there is still an active demand for workplace training among older workers; 36% of 55-59 year olds and 26% of 60-65 year olds in paid work would like more training.

There is still more work to do to ensure that older workers feel treated equally; although only three percent said they had actively experienced discrimination at work as a result of their age, 22% of those not yet retired mentioned a change in workplace attitudes towards older workers as something which would help them to keep working longer.

There is scope to improve the guidance offered to people planning their transition from work to retirement, including through further promotion of the midlife MOT to all eligible groups. The Midlife MOT is a free online support tool to encourage more active planning by people in their 40s, 50s and 60s in the key areas of work and skills, health and wellbeing and finances. Only six percent of people who had not yet retired had heard of the midlife MOT (which came into being in February 2019) but, once the tool was explained to them, 47% of those who had not previously heard of it said they would make use of the tool.

Planning for later life among the self-employed

Increasing numbers of people are becoming self-employed with many opting to move into self-employment later in life. Around one in ten (11%) of 40-75 year olds were currently self-employed in some capacity and as many as 29% had experienced a period of self-employment at some point in their career. The proportion of workers currently in self-employment increased with age, with 23% of those 60-65 in paid work and 34% of those 66 and over in self-employment.

Working conditions and job flexibility were important considerations in being self-employed. The main reasons given for being in self-employment were because it was the nature of the job (45%) or as a way of earning more income (42%). However, 39% mentioned better working conditions or job satisfaction and 23% mentioned being able to fit work round caring responsibilities. Most self-employed (85%) said they would prefer to remain in self-employment rather than becoming an employee.

The self-employed were more likely than employees to expect to keep working longer with 72% of those not yet retired expecting to work after the age of 65 (compared with 57% of employees). This is likely to be driven at least in part by the need to fund retirement in the absence of pension provision. However, it is also likely to reflect greater enjoyment of/commitment to work among the self-employed. The self-employed also had a higher ideal retirement age than employees.

Saving for retirement presents a challenge for self-employed people who have access to fewer options for retirement saving and, because of greater potential fluctuations in income, are less likely to save regularly. A higher proportion of self-employed said they had not yet started saving for retirement compared with employees (22% vs 7%). Those that had started saving tended to have done so later. The self-employed were less likely than employees to have a private pension (65% vs 89%). Self-employed pension holders were most likely to hold a personal pension (61%) though 58% had a workplace pension, presumably from previous employment.

The most common reason self-employed people gave for not having a pension (mentioned by 44%) was that they would fund their retirement from other sources. The self-employed were more likely than other groups to say that they would fund their retirement from non-pension wealth, including 80% who mentioned savings or investments and 51% who mentioned support from family or friends. Only three percent of the self-employed expected to be reliant solely on the State Pension.

1. Introduction

This report presents new evidence on whether and how people aged 40 to 75 are planning and preparing for retirement. The findings are based on analysis of a representative survey of 2,655 40 to 75 year olds in Great Britain conducted between November 2020 and February 2021.

1.1. Aims of the research

The Planning and Preparing for Later Life Survey (PPLL) was commissioned by DWP to provide information on people’s attitudes and behaviours around planning for retirement. It shares some content with the previous Attitudes to Pensions series (Clery et al., 2010; McLeod et al, 2012) but is more wide ranging. It covers behaviour as well as attitudes and, crucially, looks at the experience of work in later life and the transition into retirement as well as financial planning and pensions. Saving for retirement and employment decisions are inextricably linked and it is important to be able to consider the two together.

The survey had the following objectives:

- to provide evidence to support policy development around income adequacy in retirement

- to gather evidence to inform the 50 Plus: Choices agenda (previously Fuller Working Lives), specifically its focus on measures that allow and encourage people to stay in work for longer

- to understand the impact of pension flexibilities on attitudes and behaviours around pension saving and planning for later life

- to develop the evidence base around the self-employed and planning for later life.

1.2. Policy context

The question of whether and how people are planning for retirement is one which is becoming increasingly important. First, increasing numbers of people are reaching and living beyond State Pension age (SPa). The population is ageing; the proportion of people estimated to be 65 and over is forecasted to rise from 18% in 2018 to 24% by 2037 (ONS, 2018). Average life expectancy beyond the age of 65 is expected to reach 23 years for women and 21 years for men by 2030 (ONS, 2019a). Second, policy changes around retirement and pensions such as the abolition of the statutory retirement age in 2011 and the introduction of Pension Freedoms in 2015 give people greater freedom over when and how they take their pension. This in turn puts more onus on individuals to take decisions about their retirement. The findings presented in this report contribute to the evidence base around how far individuals are able to make well informed choices about how and when to retire and will be in a position to enjoy financial security when they do.

1.2.1. The changing nature of work

People’s planning for and experiences of retirement will be closely tied up with their experience of employment and the opportunities afforded them to either continue in or transition out of paid work. Paid work represents the main way in which most people will accrue resources for retirement and helps to ensure financial security for pensioners. Increasingly, the intrinsic benefits of paid work and the health and wellbeing advantages associated with remaining in fulfilling paid work in older age, both for individuals and their employers, are also recognised (OECD, 2020).

The number of employees aged 65 and over in the UK has been increasing. There were 1.26 million people aged 65 and over in work in the period April-June 2020 (DWP, 2020a). However, labour market participation drops off sharply after the age of 50: the employment rate falls from 83% for 50-54 year olds to 56% for 60-64 year olds and just nine percent for 70-74 year olds.

The nature of work is also changing. Over the last 20 years, increasing numbers of people have become self-employed, reaching a high of 5,025 million self-employed in the last quarter of 2019 (ONS, 2021a). The COVID-19 pandemic, which began in 2020, has led to a drop in the number of self-employed, with 4.36 million self-employed in the period Jan-March 2021 compared with 4.97 million in the same period in 2020. However, the growth in self-employment in the past ten years or so has been greatest amongst older workers, such that in 2020 10% of the self-employed were over 65 (DWP, 2020a). The experience of the self-employed with regard to work and, in the absence of workplace pensions, saving for retirement is likely to be very different from that of employees.

Labour market transitions are also becoming more complex, especially following the end of the statutory retirement age in 2011. People may transition into or out of retirement or have a period of semi-retirement prior to fully retiring from work (Platts et al, 2019). Increased flexibility can bring significant benefits to both individuals and the businesses that employ them by enabling people to continue working for longer. However, flexibility also represents a risk if it leads people to cut back on work too early without considering the financial implications for their retirement. It is important that both policymakers and employers understand the needs and preferences of older workers so that they can ensure they are supported in making a successful transition from work to retirement. This is likely to be especially true in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Older workers have found their employment situation affected by COVID-19 with 17% percent of eligible workers aged 65 and over furloughed on 31 March 2021 (HMRC, 2021). Only employees under 25 had a higher take-up rate for the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme. Older workers, especially those with health concerns may find it particularly difficult to re-enter the labour market and may find themselves retiring earlier than they would have liked. Other people may find themselves having to postpone retirement in order to make up for lost income as a result of the pandemic (Crawford, R, and Harjalainen, H., 2020).

A number of policy initiatives have been introduced to encourage employers to better support workers as they transition to retirement. The government’s 50 Plus: Choices scheme builds on work done as part of the Fuller Working Lives initiative which was developed in partnership with employers and provided recommendations around the retention and recruitment of older workers aged 50 and over (DWP, 2017). These included recommendations around encouraging flexible working and ensuring that older workers were given access to training, as well as encouraging active knowledge transfer between generations. Employers were also encouraged to provide retirement transition preparation for employees.

Launched in February 2019, the midlife MOT is a free online support tool to encourage more active planning by people in their 40s, 50s and 60s in the key areas of work and skills, health and wellbeing and finances. Employers are encouraged to promote the midlife MOT tool to their employees and to have follow-up conversations. This study (hereafter referred to as PPLL) will contribute to the evidence on how best to support workers in the run up to retirement. It will explore experiences of work among 40-75 year olds and how these vary by age, what it is people want out of work as they approach retirement and what, if anything, may encourage or enable people to keep working for longer or return to the workforce later in life. It will also pay particular attention to the experiences of the self-employed and how they may best be supported to plan for retirement.

1.2.2. Pension reform

Both the State Pension and the private pension sector have undergone significant reform in recent years. There has been an incremental increase in the SPa, with the retirement age for women in line with that of men from 2018, and the SPa for both men and women set to increase to 67 by 2028. In 2016 the new State Pension was launched. This pension is flat rate and single tier, based on an individual’s National Insurance record. The two tier system comprising a basic State Pension and then a second State Pension related to earnings has been phased out. PPLL will help to provide evidence on the extent to which people are aware of these changes in the State Pension and how they will affect them in retirement.

Employers are now required to automatically enrol eligible employees in a suitable workplace pension and make a minimum level of contributions. The introduction of automatic enrolment has increased the proportion of people saving into a workplace pension; since 2012, over 10 million people have been enrolled into pension saving (DWP, 2020b). However, despite an increase in minimum contribution levels introduced in 2019, there remain concerns over whether this level of contributions (8%) will be sufficient to enable people to maintain their standard of living in retirement (PPI, 2020). Younger cohorts are likely to be especially reliant on their Defined Contribution (DC) pension contributions to fund retirement as they are less likely to have accumulated other sources of wealth, for example through housing, than older cohorts. Research by IFS (IFS, 2016) found that individuals who were born in the early 1980s had accumulated approximately only half of the average wealth holdings of the 1970s cohort at the same age. PPLL examines people’s expectations around the level and sources of income they will have available in retirement.

Perhaps the biggest change to the private pensions market is the introduction of Pension Freedoms in 2015. These give people with DC pensions the freedom to make withdrawals from their DC pensions from age 55 without the need to take out an annuity or incur a heavy tax penalty. Automatic enrolment has led to increased numbers of people being newly enrolled in DC pensions. More generally the private pensions market has shifted in favour of DC over Defined Benefit (DB) pensions, the latter now considered unaffordable and less suited to labour market conditions which make it less likely that individuals will remain in the same job throughout their career. In 2020 there were around 14.6 million active members in DC schemes compared to around 6.7 million active members in DB schemes across the private and public sectors (PPI, 2020). In 2020 active members of private sector DB schemes had declined to 1.0 million (Pension Protection Fund, 2020). This shift towards DC pensions means that many more people, including people auto-enrolled in pensions who may not have previous experience of saving or investment, are faced with decisions on how to optimise their pension choices under the new freedoms.

There are concerns that the new freedoms may have led people to view their pension in terms of short term consumption opportunities rather than a source of long term income in retirement (The People’s Pension, 2021). Large numbers of people are choosing to take either partial or full cash lump sums from their pensions; in 2019/20 56% of DC pensions accessed for the first time involved full cash withdrawal (FCA, 2020). Depending on how those lump sums are used, and how people choose to utilise the remainder of their pension pot, there is a risk that they will leave themselves unprovided for later in their retirement. PPLL provides an opportunity to explore who is accessing their DC pension, and how and when they do this, alongside what other provision for retirement, if any, they may have in place.

Alongside the introduction of Pension Freedoms, the government launched several new sources of information, advice and guidance to help people navigate these freedoms including Pension Wise. However, evidence from the Financial Conduct Authority’s Financial Lives 2020 survey casts doubt on the extent to which people are seeking out information to inform their choices or actively engaging with their DC pension. The survey found that 58% of those aged 45+ who were yet to retire have put little or no thought into how they will manage financially in retirement whilst 37% of those aged 45+ with a DC pension in accumulation did not understand the different options they can choose from when taking money from their pension. Over half (55%) of people with an active DC pension had low or very low levels of engagement with their pension whilst many were taking the decision to access their pension without advice (FCA, 2021). PPLL will look at the take-up and response to different information resources aimed at DC pension holders as well as potential barriers to pensions engagement, such as people finding it difficult to keep track of pensions or lack of trust in pensions.

1.2.3. The impact of COVID-19

PPLL was commissioned before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. The survey was not designed to explore whether and how COVID-19 may have affected people’s plans for retirement. However, fieldwork took place between November 2020 and February 2021 against the backdrop of the pandemic. Respondents were asked two very general questions about whether COVID-19 had impacted on their employment situation and their plans for retirement. Only a small proportion of people replied that this had been the case (See Chapter 2 for more details). However, it is possible that the pandemic may have had other unreported impacts on people’s current circumstances and expectations for the future and that some findings may have been different had the survey been conducted outside of the pandemic.

1.3. Methodology

More details of the survey methodology are given in Appendix 2 of this report and the separate technical report (REF). The main features of the survey are summarised here.

PPLL was originally commissioned and designed as a face to face survey. However, limitations on fieldwork as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that fieldwork had to be conducted by telephone.

1.3.1. Sample

The sample for PPLL was drawn from respondents to the Family Resources Survey (FRS) 2017/18 who had agreed to be re-contacted for further research. The sample of named respondents, one per household, was designed to be representative of the population of 40 to 75 year olds in Great Britain. In households where there were multiple eligible individuals, a respondent was selected at random. As the self-employed were identified as being of particular analytic interest, those who identified as self-employed at FRS 2017/18 were assigned a boosted probability of selection to help ensure that there were sufficient numbers interviewed for the analysis.

A starting sample of 4,744 individuals was drawn, 159 of which were allocated to the pilot stage of the project. Once it became necessary to switch fieldwork to telephone mode, a top up sample comprising an additional 4,568 individuals was drawn to compensate for the lower expected response rate from telephone compared with face to face interviewing. This effectively meant that one individual from all FRS 2017/18 responding households in Great Britain with a 40-75 year old happy to be re-contacted was selected for PPLL. The only exception was a small sub-set of households that had already been invited to participate in a different research project. The final sample issued for the main survey was 9,153 individuals.

1.3.2. Questionnaire development

The questionnaire was developed in close collaboration with DWP to ensure that it met their requirements. Questions underwent both cognitive testing and piloting to ensure that they were fit for purpose. Two rounds of cognitive testing took place in early 2020; interviews were conducted with a small number of respondents to gain feedback on whether the key concepts and terminology used in the survey were being understood as intended. The full questionnaire was then piloted in September 2020 to test the survey procedures, routing and timings and check how the survey would work when carried out over the telephone. Invitations to take part in a telephone interview were sent to 159 sample members and productive interviews were achieved with 20 people. Following the pilot, which had an average interview length of nearly 1.5 hours and struggled to recruit respondents, the content of the questionnaire was reduced in consultation with DWP.

1.3.3. Fieldwork

All sample members were sent an advance letter ahead of fieldwork inviting them to take part in the survey and advising that an interviewer would call them in the next few weeks. Sample members for whom a telephone number was not available (11% of the total sample) were invited to contact a Freephone number and provide a number on which an interviewer could call them.

Interviews were conducted using Computer Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI) between 14th November 2020 and 7th February 2021. The average interview length was 48 minutes. A £5 Love2Shop voucher was sent to the respondent on completion of the interview as a thank you.

2,655 responses were achieved, a response rate of 29%.

1.3.4. Weighting

The survey has been weighted to ensure that findings can be generalised to the population of 40-75 year olds in Great Britain. The weights take account of differences in the probability of being selected to take part in the original survey, FRS 2017/18, as well as the probability of subsequently being selected to take part in PPLL. The sample of individuals invited to take part in PPLL was calibrated to be representative of the target population in terms of sex and age using ONS mid-year population estimates. A further stage of weighting then corrected for the fact that certain groups within the PPLL sample were more likely to respond to the survey request than others. The non-response weights accounted for differences in a range of characteristics including age, sex, region, employment status, ethnicity, housing tenure, household composition, highest educational qualification, council tax band, the National Statistics Socio-Economic Classification (NS-SEC) and population density quintile (see REF TO TECH REPORT for more details). The final weighted data were then checked against ONS mid-year population estimates and Labour Force Survey estimates to ensure that they closely resembled the target population in terms of sex and age and, for under 65s, employment and education. It is not possible to calibrate the PPLL final sample of respondents to the underlying population on all characteristics; there may be some groups, for example recent immigrants to the country or people less likely to engage with surveys, who are underrepresented. Nevertheless, the weighting strategy employed allows findings to be generalised to the population with reasonable confidence.

1.3.5. Sub-groups used in analysis

Throughout the report, findings are broken down by certain characteristics including age, gender and employment status. More details on how some of these sub-groups are defined are given below. Table A1.1 in Appendix 1 of this report shows the composition of the final weighted sample in terms of key demographics including age, gender, employment status, retirement status, income and financial literacy.

Retirement status

Findings are broken down by whether the respondent is fully retired, semi-retired or not yet retired. People under 50 were assumed to not yet be retired unless they reported their only activity in the last month as “retired”. People aged 50 and over were given the option to self-classify as either not yet retired, semi-retired or fully retired. Full retirement was defined as “not intending to do any further paid work”. Semi-retirement could involve currently doing some paid work or “not currently working but may do some paid work in the future”.

Financial literacy

Financial Literacy was measured using a shortened version of the financial literacy index originally employed in the Healthy Ageing in Scotland (HAGIS) study. The original 13-item scale was reduced to six items which have been used to measure financial literacy on other surveys including the British Election Study.

Each respondent was given a score from 0-6 depending on how many items they answered correctly. Depending on their score they were then categorised into three roughly equal-sized groups defined as high (score 5-6), medium (3-4) or low (0-2) financial literacy.

Household composition

Household composition was determined on the basis of partnership status ( that is whether the respondent was currently living with anyone as a couple) and the presence of financial dependents. Finacial dependents were any family members (not just children) who were either fully or partially financially dependent on them. The following four groups have been compared:

- single – no dependents

- single – dependents

- couple – no dependents

- couple – dependents

Occupation

Comparisons on the basis of occupation have been made using the Standard Occupational Classification 2010 (SOC 2010). Respondents have been classified according to which one of nine major groups their occupation falls into.

Semi-retired respondents in paid work were asked both about their current job and, if different, the job they were doing immediately prior to becoming semi-retired. For the purposes of analysing people’s expected retirement age (Chapter 3) or satisfaction with work and the transition to retirement (Chapter 4) occupation based on their current job is used. For the purposes of analysing people’s pension provision (Chapter 5) occupation based on job pre-retirement is used on the basis that this is likely to be the bigger influence on pension provision.

Income

The survey collected information on both the respondent’s personal income and the total income of their household. In both cases, gross income from any sources (not just earnings from employment) was measured. Both personal and household income may be important determinants of individual’s retirement planning with, for example someone who has a low personal income but shares a household with a higher earner (something which has traditionally applied to many women) potentially being in a different financial position to someone on a low income who is the sole earner in a household. Given that the survey focuses on individual decision making, the analysis is conducted using the measure of respondent’s personal income unless otherwise stated. Wider household wealth is taken into account in some analyses which explore the association with savings and tenure.

Employment status

There are two aspects to the employment status variable used for analysis; whether the respondent is in paid work and – if so – whether this is as an employee or self-employed. Anyone who reported having done any paid work in the past month was counted as being in paid work. Anyone not in paid work and under 50 was automatically considered to be not working whilst those 50+ were given the opportunity to report if they considered themselves fully retired or not. The respondent’s status as an employee or self-employed was determined by their status in what they consider to be their main job. A small number of employees may be employees in their main job whilst doing some other work as self-employed (or vice versa).

1.4. This report

1.4.1. Report outline

The report is divided into four chapters covering four aspects of retirement planning:

- knowledge and engagement around retirement planning: What sources of information do people use to help them plan for retirement? How well-informed are people about state pension arrangements? How engaged are people with their private pension arrangements?

- people’s expectations for retirement: When do they expect/want to retire? How much income do they want/expect to have? How do they expect to fund their retirement?

- transitioning from work to retirement: How satisfied are older workers with their employment circumstances? Would people like to change their working arrangements as they approach retirement? What would encourage people to keep working longer?

- pension provision: Who has a private pension? What type of pension arrangements do people have in place? How do people 55 and over make decisions around accessing their pensions?

1.4.2. Caveats to the analysis

This report is intended to document some key findings from the PPLL survey; it is not an exhaustive sourcebook of all of the survey’s findings. It covers most findings from the survey at a descriptive level, highlighting differences between key sub-groups where appropriate. In particular, the report considers how people’s experiences of and requirements around preparing for retirement may vary by characteristics including age, gender, retirement status, employment status and household composition. The role played by resources – both financial and information/ knowledge – is also considered. Many of these factors will of course be interrelated. The analysis presented in this report is cross-sectional and bivariate only, that is it looks at the relationship between two variables, for example financial literacy and whether someone has a pension, without being able to determine whether one variable necessarily causes another (rather than, for example, both variables being the result of a third variable such as income). Tables A1.2 – A1.6 in Appendix 1 demonstrate how closely age, retirement status, employment status, income and financial literacy are related. For example, the proportion of people currently on low incomes (<£10,500 per year) is higher among those not in paid work, that is either not working or fully retired. This relationship between employment and income helps to explain the higher concentration of people on high incomes among those under 55. Financial literacy is higher among people with higher incomes as well as among men compared with women.

Where questions were routed based on responses to previous questions, and so were asked of only a relatively small number of respondents, even bivariate sub-group analysis may not always have been possible.

Retirement planning is closely related to age. PPLL findings, which apply only to those aged 40-75, may therefore look somewhat different to those from other sources which cover the whole adult population.

The information on pensions reported in this survey is based on individuals’ self-reports of the pensions they hold. It should be borne in mind that people may not know or recall every detail of their pensions and PPLL is not intended to provide complete or precise estimates of people’s pension holdings. Figures presented here, for example regarding the number of pensions people hold or their pension pot size, may differ from data available from other sources such as pension providers. Nevertheless, despite some possible inaccuracies in recall, the PPLL pensions data provide a valuable opportunity to evaluate how much people know/can report regarding their pensions and to explore how people’s pension saving may be related to a wide range of other factors including their personal, family and employment situation.

1.4.3. Reporting conventions

Where the report discusses differences between groups defined by a particular characteristic (such as age or sex) on a particular measure, the differences can be assumed to be statistically significant at the 5% level unless otherwise stated. Some findings which are significant only at the 10% level due to small base sizes, have been reported. Where this is the case, it has been noted in a footnote.

The statistical tests used only allow us to identify whether the relationship between two variables is significant overall. Multiple tests of significance between different categories of a variable were not performed. For example, a passage which reports that saving increased with age may illustrate this by saying x% of 40-49 year olds had savings compared with y% of those 65+. The overall relationship between age and savings will have been tested for statistical significance but the specific difference between x% and y% will not have been tested separately.

Numbers quoted in the text or displayed in figures which combine two or more answer categories are calculated based on unrounded numbers and so may differ slightly from the rounded numbers shown in the accompanying tables. Don’t know and refusal responses are excluded from table bases unless otherwise stated. This may mean that the bases shown in tables for sub-groups will not always sum to the base shown in the total column. For the same reason, tables with the same base description, for example “All respondents” may include different numbers of respondents.

Percentages less than 0.5% are shown in tables with a *. ‘0‘ indicates that no one selected that response option. Numbers shown in [ ] were calculated on a base size of less than 50.

2. Planning for retirement

2.1. Introduction

This chapter looks at the extent to which people actively engage in planning and preparing for their retirement. It explores the sources of information, advice or guidance, if any, they have used to plan for their retirement, the age at which people start planning for their retirement and the factors they consider when doing so.

Recognising the importance of retirement planning, the government has introduced a number of initiatives to help people become better informed. This chapter explores the take up and response to several of these including Pension Wise and midlife MOTs. It also considers possible barriers to engagement where further action may be needed. These barriers include a lack of knowledge and awareness of recent changes in the State Pension, lack of trust in pensions and pension providers and people finding it difficult to keep track of their private pensions.

Finally, this chapter looks briefly at what impact the COVID-19 pandemic which began in 2020 has had on people’s retirement planning and which groups have been most affected by the pandemic.

2.2. Information sources used for retirement planning

All respondents, regardless of whether they had already retired or not, were asked which, if any, sources of information, advice or guidance they had ever used to plan for retirement. This might have been sources that a respondent actively sought out or information that was provided to them, for example by a pension provider.

However, the fact that the question was framed in terms of “use” implies some degree of active engagement with, rather than just receipt of, these information sources. “Planning for retirement” is likely to cover, but may not necessarily be limited to, financial considerations (see also Section 2.5). Some tools such as the midlife MOT (see Section 2.2.2) or employer-provided information (see Section 2.2.3) explicitly aim to take a holistic approach to retirement planning and look beyond just the financial aspects of retirement.

Just under three-quarters of all respondents (74%) had used at least one of the sources listed (see Table A2.1 in the appendix). However, this means around a quarter (26%) had never consulted any of these sources. People who had retired were more likely than those who had not yet retired to have used at least one source of information, advice or guidance to plan for retirement. The self-employed and those not in work were less likely to report having used any sources compared with employees. This may reflect differences in income, and therefore preparedness to start planning for retirement, among the self-employed (see Table A1.5) as well as the fact that employers were a commonly used source (see Figure 2.1). Consistent with the fact that pension providers were another common source of information, people without a private pension (which includes a higher proportion of the self-employed and those not in work) were also less likely than those with a private pension to report having used any sources of information, advice or guidance. Among those without a pension, those that had made use of a source were most likely to have used a government website (24%) or friends/relatives (16%).

People with low financial literacy, who may be less engaged with the financial aspects of planning for retirement, were also less likely to have used any of the sources listed compared with people with high financial literacy; 57% compared with 83% (See Section 1.3.5 for details of how financial literacy was measured).

Figure 2.1 shows that the most common source of information, advice or guidance used was Government websites such the DWP website, Check Your State Pension or another Gov.UK website (38%). The proportion of people using government websites for information on retirement may be even higher than this; 51% of all people below State Pension age (SPa) reported using a government website to check their SPa when asked directly about this for example (see Section 2.6.1). Over a third of people (37%) had used their pension provider as a source of information, including 45% of people with a private pension. There was no difference in the proportion of Defined Contribution (DC) versus Defined Benefit (DB) pension holders using information from their pension provider (Chapter 5 looks in more detail in the sources of information,advice or guidance people used prior to accessing their DC pension). Around a third of people had used their employer as a source of information, including 44% of current employees.

Nearly a quarter of people (24%) had received information from family and friends. However, it was rare for this to be the only source of information people used, with only three percent of people receiving information from family and friends but not using any other information source. People generally used multiple sources of information, advice or guidance, with 27% of those who had made use of any information source using two sources and 44% using at least three sources. People who used only one source were most likely to have used a government website (24%) or their employer (22%).

Around three-quarters of 40-75 year olds had used at least one source of information, advice or guidance to plan for retirement. The most common source used when planning for retirement was Government websites such the DWP website, Check Your State Pension or another Gov.UK website.

Figure 2.1 Proportion of people using different sources of information, advice or guidance when planning for retirement

| Government website | Pension provider | Employer | Professional financial advisor | Friends and family | Pensions Wise or the Pensions Advisory Service | Other source | None |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38% | 37% | 34% | 29% | 24% | 10% | 7% | 26% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life 2020/21

Base: All respondents (n=2,655)

Notes: Respondents could select more than one answer so percentages may sum to more than 100%

As seen in Figure 2.2, people on low incomes were less likely to report having used any sources of information, advice or guidance to plan for retirement (40% of those with a personal income below £10,500 had not used any source). Those on low incomes were less likely to be in employment, less likely to have a pension and less likely to be in a position to start actively planning for retirement. This is reflected in the fact that they were less likely than those on higher incomes to have used information from a pension provider or employer or to have actively sought information from a financial advisor.

Use of information sources varied by income. Those with the lowest incomes were more likely not to have used any source, including financial advisors.

Figure 2.2 Proportion of people using different sources of information, advice or guidance when planning for retirement, split by income groups

| Income groups | Government website | Pension provider | Employer | Professional financial advisor | Friends and family | Pensions Wise or the Pensions Advisory Service | Other source | None |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under £10,000 | 31% | 20% | 19% | 19% | 18% | 9% | 5% | 40% |

| £10,500 to under £27,000 | 42% | 37% | 32% | 27% | 23% | 11% | 5% | 25% |

| £27,000 to under £44,000 | 43% | 45% | 43% | 36% | 26% | 11% | 8% | 18% |

| £44,000+ | 42% | 57% | 56% | 46% | 35% | 8% | 12% | 5% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life 2020/21

Base: All respondents (n=2,655)

Notes: Respondents could select more than one answer so percentages may sum to more than 100%

Whilst many of the sources available to people are only able to provide information and guidance to help people reach their own decisions about pensions and/or financial planning, financial advisors are able to offer specific advice and recommendations. However, there is usually a cost associated with obtaining such professional advice which may limit take up. Twenty-nine percent of PPLL respondents reported using a financial advisor. Older people, men and those on higher incomes were more likely to have used a financial advisor. Self-employed people were more likely to have used a financial advisor than employees (36% vs 28%), perhaps reflecting the fact that – in the absence of an employer/workplace pension – the self-employed have more need to seek independent advice on planning for retirement. Thirty-six percent of people with a private pension, including 40% of people with a DC pension, had consulted a financial advisor. People who had consulted a financial advisor were mostly satisfied with the advice they received (86%), with around half (51%) saying they were very satisfied (see Table A2.2 in Appendix 1).

One alternative to paid financial advice is Pension Wise, a free and impartial service, operated by the Money and Pensions Service (MaPS) and set up by government in 2015, which offers guidance for people aged 50+ regarding Pension Freedoms. MaPS directly promotes Pension Wise for people who have a DC pension and want to decide how to take their money. Use of Pension Wise among DC pension holders aged 50+ is still relatively low with only one in seven DC pension holders (17%) having used Pension Wise. However, the service will not necessarily be relevant to everyone, including those who took their pension before 2015 or those who are still a long way from retirement. Chapter 5 looks in more detail at the use of sources of information, advice or guidance among DC pension holders 55 to 65; 29% of people in this age group who had accessed their DC pension had used Pension Wise. Satisfaction with Pension Wise was more mixed than satisfaction with professional financial advisors. People 50+ who had used Pension Wise were mostly satisfied with the guidance received (76% very or quite satisfied), although only 34% said they were very satisfied (see Table A2.2 in the annex).

The findings on financial advisors and Pension Wise are positive in that they show that, when people do engage with and consult these sources, they are generally happy with the guidance they receive. However, given the relatively low use of Pension Wise and the differences in take up of financial advisors by income, there is potentially some work to do in terms of making financial advisors more accessible to different groups and in promoting Pension Wise as a source of information.

2.2.1. Future use of information sources

People who had not yet retired were asked not only about sources of information, advice or guidance they had already used, but also about whether they might consult any of these sources in the future if they wanted more information on planning for retirement (regardless of whether they had already used them). Figure 2.3 shows the combined figures for people who have either already used a source or said they would do so in the future. Government websites, perhaps the easiest source of information to access, remain the most likely source to be used. Nearly one in five (18%) people had not done this at the time of being asked but said they would use a financial advisor in the future. Nine percent had already used Pension Wise and a further nine percent said they would use the service in the future. A small minority, seven percent, of people not yet retired had not previously used any sources or information, advice or guidance and said they did not plan to use any of the listed sources in the future. Finding a way to engage this group in planning for retirement will be important.

Nearly half of people not yet retired had either used or intended to use a financial advisor to help them plan for retirement.

Figure 2.3 Proportion of people who had used or would use different sources of information, advice or guidance in the future when planning for retirement

| Used or use different sources | Government website | Pension provider | Employer | Professional financial advisor | Friends and family | Other | Pensions Wise |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Used | 37% | 36% | 35% | 28% | 26% | 10% | 9% |

| May use in future | 27% | 8% | 7% | 18% | 6% | 12% | 9% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life 2020/21

Base: All respondents not yet retired (n=1,591)

Notes: Respondents could select more than one answer so percentages may sum to more than 100%

2.2.2. Midlife MOT

People who had not yet fully retired were asked separately about whether or not they had heard of the midlife MOT and, if so, whether they had received help or support through one. The midlife MOT is a free online support tool to encourage more active planning by people in their 40s, 50s and 60s in the key areas of work and skills, health and wellbeing and finances. Only six percent of people who had not yet retired had heard of the midlife MOT and only 13% of that group (or one percent of all respondents who had not yet retired) had made use of the service. This low take-up is perhaps not that surprising given that the scheme was only put in place in February 2019. People who had not previously had a midlife MOT received a brief explanation of the scheme and were then asked if this is something they would consider taking up in the future. Nearly half of this group (47%) said they probably or definitely would. There may be further work to be done in promoting the scheme and encouraging take-up across eligible groups.

2.2.3. Employer-provided guidance

Current or previous (now retired) employees aged 50 and over were asked for more details about any guidance on retirement planning received from their employer. This could cover, but was not limited to, financial considerations. The majority (60%) had received none of the forms of guidance listed in Figure 2.4 from their employer. It is not possible, however, to determine whether this is because the employer did not offer this form of guidance or whether it was offered but not taken up or recalled. Information was most commonly received in a passive way, through written material or posters. However, nearly one in five (18%) had received workshops or courses organised at their workplace. Consistent with the findings presented on the midlife MOT in section 2.2.2 above, only a small proportion (3%) had received a midlife MOT through their employer. However, given that the scheme only came into place in February 2019, it would not have been available to all respondents, many of whom will have retired prior to 2019.

The majority of employees 50+ had not received guidance from their employer.

Figure 2.4 Proportion of employees 50+ who had taken up different sources of employer-provided guidance on retirement

| Written material such as posters/leaflets | Links to online resources | Courses or workshops organised at workplace | Recommendations or referrals to external organisations | Mid-life MOT or mid-life career review | Other source | None |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 22% | 19% | 18% | 12% | 3% | 4% | 60% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life 2020/21

Base: All past/current employees 50+ (n=1,629)

Notes: Respondents could select more than one answer so percentages may sum to more than 100%

Interestingly, around a third of people who had received information from their employer (35%) said they had not received information on any of the specific topics shown in Figure 2.5. This might suggest that some of the guidance employees received was either very general (for example with links to other information sources) or informal support on retirement planning not related to a specific topic.

The most common topic on which employer-guidance was received was financial planning, followed by how to maintain an active lifestyle in retirement.

Figure 2.5 Proportion of employees 50+ who had received employer-provided guidance on different topics

| Financial planning | Maintaining an active or busy lifestyle | Managing health | Working flexible or reduced hours in the run-up to retirement | Future opportunities for paid work | Future opportunities for unpaid work | Other answer | None |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 38% | 32% | 29% | 21% | 13% | 13% | 3% | 35% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life 2020/21

Base: All past/current employees 50+ who made use of employer-provided support (n=691)

Notes: Respondents could select more than one answer so percentages may sum to more than 100%

Employees who had received some guidance from their employer (in any form) were fairly neutral in their response to this guidance (Table A2.3 in the annex). Fifty-seven percent said they were very or quite satisfied with the information received, with only 19% saying they were very satisfied. Over a third (37%) said they were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied. This, together with the relatively high proportion of people who could not specify which topics the guidance covered, may suggest that, whilst commonly used, there may be scope to improve the quality of employer-provided guidance.

2.3. Engagement with information about private pensions

Around three-quarters (76%) of people reported having a private pension. Chapter 5 provides more information on who has a private pension and the types of pension people hold. This section of the report looks at the extent to which people are actively engaging with their private pension, keeping track of their pension holdings and making use of information provided by their pension provider. It also looks at the extent to which people trust their pension provider.

Previous research has found generally quite low levels of engagement among private pension holders. The 2020 Financial Lives survey (FCA, 2021) found that many people with a private pension are not well prepared for retirement: the study showed that 58% of those aged 45+ who are not retired have put little or no thought into how they will manage financially in retirement whilst 37% of those aged 45+ with a DC pension in accumulation do not understand the different options they can choose from to take money from their pension.

Most PPLL respondents with a private pension (77%) said they found it very or fairly easy to keep track of their pension savings, with 35% saying they found it very easy. However, one in five (20%) said they found it very or fairly difficult to keep track of their pension savings. Younger age groups were more likely to say that they found it difficult to keep track of their pension savings, with 29% of those aged 40-49 saying they found it very or fairly difficult to keep track. It may be that people find it easier to keep track of their pensions once they have retired and have accessed or started receiving their pension, that is when decisions about their pension have been made and are less likely to be subject to change. It may also reflect the fact that DC pensions, which are subject to more uncertainty, were more common among younger cohorts (see Chapter 5, Section 5.3). There is no evidence that people who had multiple pensions found it harder to keep track than people with just one pension.

When asked why they found it difficult to keep track of their pension, a majority of those who found it difficult to keep track said that they found information about pensions confusing (58%). This was true even of people with high financial literacy who found it difficult to keep track, 63% of whom said they found information about pensions confusing. Many also said that it takes a lot of time to keep track of pension savings (45%) and that the information is kept in different places (43%) (Figure 2.6).

When asked why they found it difficult to keep track of their pension, a majority said that they found information about pensions confusing.

Figure 2.6 Proportion of pension holders providing these reasons why they found it difficult to keep track of pension savings

| Pension information confusing | Lot of time keeping track of pension | Information kept in different places | Information in different formats | Other answer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 58% | 45% | 43% | 37% | 20% |

Source: Planning and Preparing for Later Life 2020/21

Base: All respondents who find it difficult to keep track of pension savings (n=336)

Notes: Respondents could select more than one answer so percentages may sum to more than 100%

As people approach 55, the age at which it is possible for them to access their DC pension pot, being aware of the options and engaging with the decisions to be made becomes increasingly important. Different sources of information, advice or guidance aimed specifically at DC pension holders facing a decision on how to access their pension are available. Pension providers are required to provide pension holders with information about their options. Retirement options packs (known as pension wake-up packs informally) are provided by pension providers 4-6 months before their agreed pension age. They are aimed at ensuring people receive timely, relevant and adequate information about their retirement options to enable them to make an informed decision about accessing their pension savings.

DC[footnote 1] pension holders aged 50 and over were asked if they had receive a pension wake-up pack and, separately, whether they had received information on the choices available to them from their pension provider. Because of concerns that respondents may not have been aware of the term ‘pension wake-up pack’, responses on the two questions have been combined in analysis to give an overall figure for the proportion of people who recalled receiving information on pension choices from their pension provider. Two-thirds (67%) of people 50 and over could recall receiving this information. It is of course likely that this information was not relevant to everyone in this age group if they are not yet ready to retire. Chapter 5 looks in more detail at use of provider information among people who have already accessed their pension.

Nearly everyone (91%) who could recall receiving information from their pension provider said they found the information at least fairly clear, with 44% saying they found it very clear. The answers on perceived clarity are encouraging. They suggest that those who recall receiving information from their pension provider found it helpful. However, there may still be further work needed to increase engagement with this information among some pension holders.

2.4. Age at which people start planning for retirement

Most 40-75 year olds (84%) had already started saving for their retirement, either through a pension scheme or through other means. When asked to select which decade of their lives they started saving for retirement, 43% said their 20s and a further 20% said they started saving in their 30s (Figure 2.7). However, 16% of people said they had not yet started saving for retirement. There is some evidence to suggest that people in younger age groups were more likely to start saving from an earlier age. For example, 69% of 40-49 year olds reported starting to save for their retirement in their 20s and 30s compared with 55% of 66-70 year olds. This may reflect success of automatic enrolment into workplace pensions. However, without data at multiple time points, enabling us to isolate the effects of individual age vs. time period, it is not possible to be sure what lies behind this finding.

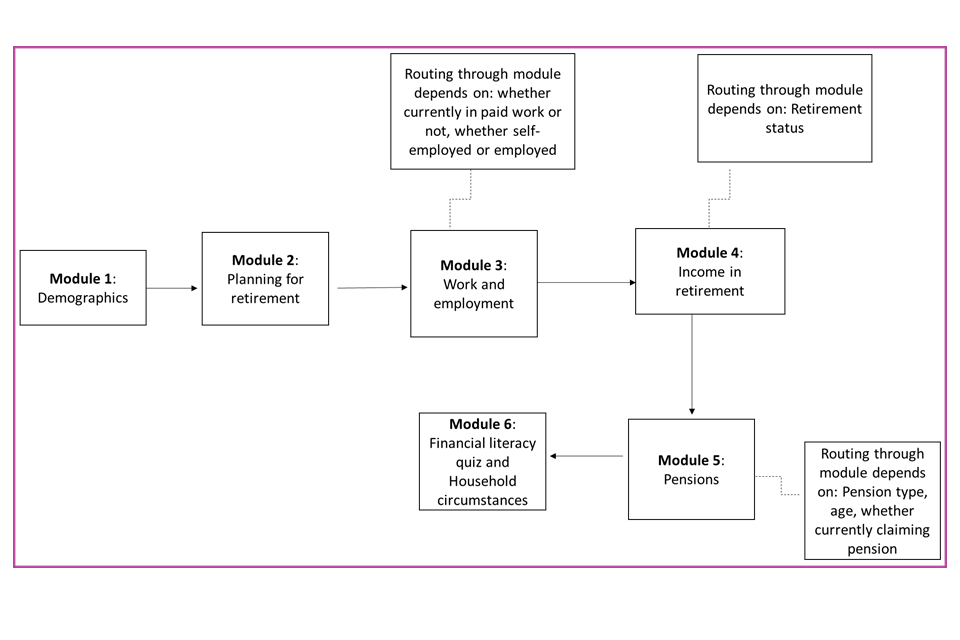

People were less likely to have started planning for when they would stop paid work and move into retirement, with 38% of 40-75 having not yet done so. The most common decade for people to start planning for the transition from work was in their 50s (21%) although a sizeable group (16%) reported planning for this in their 40s.