Plan for Jobs Cross-cutting Evaluation Wave 1 and 2 synthesis report

Updated 23 May 2025

DWP research report no. 1055.

A report of research carried out by Ipsos and the Institute for Employment Studies (IES) on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence.

To view this licence, visit the National Archives website.

Or write to:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our website at: Research at DWP

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email: socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published May 2024.

ISBN 978-1-78659-677-2

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

Introduction

Between March and April 2020, claimant unemployment increased by 69 per cent to 2.1 million as a result of restrictions on business operation and social mixing passed into law in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Scenarios developed by the Bank of England and Office for Budget Responsibility at this time suggested that the unemployment rate could rapidly increase to 10%[footnote 1]. The Government’s Plan for Jobs (PfJ), announced on 8 July 2020 was designed to respond to this increase in unemployment. More than £7 billion was allocated for measures designed to support the UK labour market. The PfJ also included measures overseen by the Department for Education (DfE) that provided routes into work, apprenticeships, and traineeships. Aspects overseen by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) aimed to help maintain job search intensity for the unemployed, improve job matching and brokerage for employers and jobseekers, and to develop the skills needed to fill vacancies.

This report provides findings from the Plan for Jobs Cross-cutting Evaluation. It considers five strands of DWP provision under the Plan for Jobs (PfJ): Kickstart scheme, Job Finding Support (JFS), the Youth Employment programme, Job Entry Targeted Support (JETS) and increased capacity on the Sector-based Work Academy programmes (SWAPs). Each of these programmes targeted claimants in the Intensive Work Search (IWS) regime.

Restart is the subject of a focused evaluation, so Restart Participants were not intentionally sampled for the survey strand of this study. Five of the ten case studies included Restart Participants. Some respondents to the survey had started Restart since being included in other sample groups (e.g. as non-Participants in Plan for Jobs). They were excluded from analysis as they were not representative of Restart Participants generally.

This multi-strand evaluation aimed to assess how well DWP’s parts of PfJ were able to respond to the economic shocks caused by the restrictions on social distancing and business operations put in place in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The evaluation also aimed to explore how well employment services were joined up and how decisions on referral and targeting were made. The research presents a snapshot of PfJ Participants, looking across the whole support package rather than an in-depth exploration of each strand.

Methodology

A mixed methodology approach was taken for the evaluation, comprising:

- Ten Local Authority case-studies completed between October 2021 and August 2022

- a wave 1 survey of 8,325 respondents who had taken part in one of the strand provisions between December 2020 and November 2021 (‘Participants’) and those who had not (‘non-Participants’). Wave 1 fieldwork was conducted between 17th February and 10th April 2022. The differing target audiences for, and design of each of the PfJ strands, meant that the length of time people had been in IWS or on their strand provision differed. More information on start dates or length of time on IWS can be found in Appendix 2. Overall, 4,042 Participants took part, comprising the following numbers from each strand:

- Kickstart: 874

- SWAPs: 790

- JFS: 848

- JETS: 817

- Youth Offer: 526

- Restart: 273[footnote 2]

- Non-Participants: 3,462

- Early leavers who started a PfJ strand but left before completing it: 735

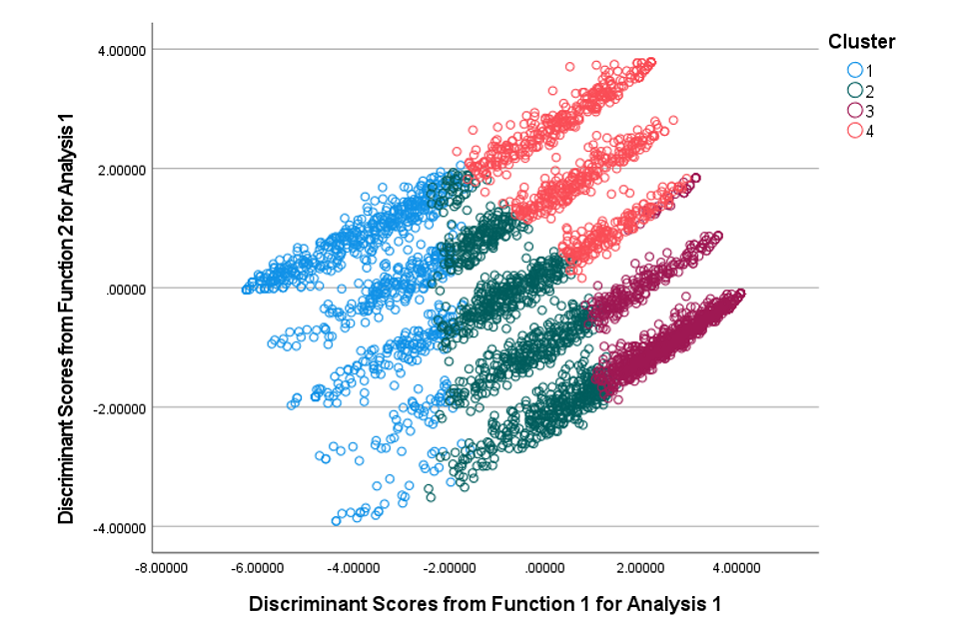

- cluster analysis of wave 1 survey data from Participants and non-Participants who were unemployed at the time of the survey to better understand the barriers to employment.

- sixty follow-up qualitative interviews with both Participants and non-Participants drawn from the wave 1 survey sample. This focused on customer experiences since the end of Plan for Jobs strands and future support needs.

- a wave 2 survey of 6,950 respondents of those who had taken part in one of the strand provisions (‘Participants’) and those who had not (‘non-Participants’). Wave 2 fieldwork was conducted between 1st November and 21st December 2022. As at wave 1, the length of time in IWS or on / since strand provision varied due to the design of the strands and their target audiences. The sample tables in Appendix 2 also detail start dates or length of time on IWS for wave 2 respondents. The following number of respondents took part, including 2,991 Participants:

- Kickstart: 526

- SWAPs: 519

- JFS: 394

- JETS: 799

- Youth Offer: 498

- Restart: 255

- Non-Participants: 3,568

- Early leavers: 391

- the wave 2 survey comprised 1,338 longitudinal interviews with people who had completed the wave 1 survey and 5,612 from a boost sample of people who had either joined a PfJ strand during a similar time period but had not completed the wave 1 survey (Participants) or had not taken part in a PfJ strand (non-Participants).

- sixty follow-up qualitative interviews with both Participants and non-Participants drawn from the wave 2 survey sample. This focused on customer experiences since the end of their time on Plan for Jobs strands as well as future support needs amongst customers who had a change of employment status between wave 1 and wave 2.

Findings

Implementation challenges

Roll-out of the PfJ strands took place during a dramatic increase in the number of Jobcentre sites and staff to meet the growing pressures of a dramatically rising claimant count which was projected to rise further. The simultaneous introduction of several new employment programmes required staff (old and new) to learn a substantial amount of new information at once. This led to challenges in Jobcentre staff accurately referring claimants to appropriate provision or being able to address some common misconceptions amongst staff around the suitability of the different programmes for different claimant types.

There was evidence of Jobcentre managers responding to these delivery challenges by providing staff training aimed at improving the referral processes where managers saw evidence of these being incorrectly implemented. In addition, when social distancing requirements allowed, contracted providers found it helpful to work from Jobcentre offices to facilitate communication with Work Coaches and improve the quality of referrals.

Other challenges encountered in the early phases of delivery centred on the perceived quality of PfJ provision during its initial rollout. In some locations, where customer feedback was initially poor, this affected staff’s inclination to make referrals and their likelihood to recommend the provision to other customers. However, staff also acknowledged that customer feedback about provision could change over time and improve once the provision became more established.

The extent to which Jobcentre staff viewed PfJ strands as giving additional options to customers also affected referrals. In some areas, staff stated that customers were already well served by existing provision and so were reluctant to refer customers to new programmes offering a similar service. The case studies found that geographical areas with existing strong partnership working practices were best able to embed the new provision with existing provision, helping to maximise the benefits for customers where PfJ provision offered additional support or services that were not available locally (e.g. the Kickstart scheme).

Feedback from Jobcentre staff indicated that on balance, referrals to employment support were primarily based on customer need, including work readiness and desired work outcomes. However, staff spoke about perceived pressures to meet referral profiles for the newly introduced PfJ strands. Jobcentre staff stated that this affected their ability to consistently make customer-led referrals. In addition, the unemployment rate did not increase as much during the COVID-19 pandemic as indicated by some of the early projections and began to drop significantly from March 2021 onwards. This meant that the claimants joining the PfJ strands were further from the labour market than had been anticipated. Among Jobcentre and provider staff, employment outcomes were therefore felt to be slower to achieve than had been expected.

Customer health profile

Across all PfJ strands, physical and mental health conditions, which can act as a barrier to work, were prevalent. Around half of Participants on any provision had a health condition or disability. This was lowest for JETS (48%) and highest for Youth Offer (63%). Non-Participants were most likely to have a health condition or disability (66%). Over half (55%) of those who left the provision early had a health condition. In the case study research, Jobcentre staff reported a higher than expected number of claimants with a health condition, particularly mental health conditions. Staff felt that the PfJ strands were not always sufficiently supportive for these customers.

Experiences of Plan for Jobs strands

At wave 1, two thirds or more of Participants on each strand knew what to expect and found the provision useful. Understanding of what support to expect from the strand was highest for Kickstart Participants (75%) and lowest amongst JFS Participants (65%). The perceived level of usefulness of the support followed a similar pattern. Nearly eight in ten Kickstart Participants (79%) and around two thirds of JFS Participants (65%) agreed that they found the programme useful in helping them to find employment or progress in their career.

Nearly seven in ten Participants reported being satisfied with the support received through each strand. Youth Offer and JETS Participants were most satisfied, whilst JFS Participants were least satisfied. Participants with a long-term health condition or disability were more likely to say that the programmes were not tailored to their needs, a consistent theme across all strands.

Approximately half of Participants experienced at least one barrier to participating in their strand, most commonly health-related barriers, either physical and/or mental health, or childcare responsibilities.

Outcomes

At wave 1 around 80% of Participants across each strand achieved an employment-related outcome[footnote 3] as a result of taking part in their strand. Kickstart and SWAPs Participants were most likely to have improved or gained new skills or to have gained relevant work experience. This may be a reflection of the design of these strands. Increased confidence in their ability to look for work was broadly consistent across Kickstart, SWAPs, JFS and JETS. Youth Offer Participants were least likely to agree with this statement (20%). The case study research found that this may be a reflection of the low self-esteem and intersecting barriers which Youth Offer customers started with, as opposed to the quality of the provision.

At wave two of the quantitative survey, more than four in ten (41%) of those who had participated in a PfJ strand stated that they were currently employed compared to around three in ten (31%) of non-Participants[footnote 4]. Those who took part in a SWAP (53%), Kickstart (48%) or JFS (48%) were significantly more likely to be employed than respondents to the survey overall[footnote 5].

Considering the sustainability of employment outcomes, employed Participants were most often on permanent or open-ended job contracts (45%). Smaller proportions were on zero-hours contracts (15%), casual / flexible contracts (11%) or temporary / seasonal contracts (8%).

Three quarters of employed Participants (75%) were satisfied with their job, compared to 72% of employed non-Participants.

Two thirds (66%) of employed Participants agreed that progressing in their current job in the next 12 months was important. Those who found their provision useful were more likely to say they wanted to progress in their current jobs, suggesting that PfJ provision may have enabled them to aspire towards furthering their careers.

Overall, two thirds of unemployed Participants had not had a job in the time between the two survey waves (or the last 12 months for the boost sample)[footnote 6]. More than half of all unemployed strand Participants (except Youth Offer) had applied for a job in the past three months. This was highest amongst Kickstart (71%) and SWAPs Participants (71%).

At wave 2, the main barrier to working identified by unemployed Participants was their physical or mental health condition (47%), regardless of the strand they participated in. Related to this, unemployed Participants were most likely to identify support to manage their physical or mental health condition (29%) as helpful to moving in to work.

Both waves of the qualitative follow-up interviews identified the importance of a strong relationship with their Work Coach or provider staff. This was instrumental in helping Participants improve their confidence and move into, or closer, to employment. Having had tailored support from a consistent Work Coach was likely to have longer lasting effects on Participant confidence and motivation to find work or progress in work.

Recommendations

At a systems level, DWP provision is part of complex and varied local employment support landscapes. In commissioning new provisions, there is therefore a need to ensure that new programmes add value to this existing support offer, and do not undermine or duplicate existing successful programmes through the introduction of competing targets, for example.

To mitigate against the potential of undermining existing programmes and services, (new) Work Coaches should be regularly briefed on changes to the provision landscape and provided with support to help identify which provision would best meet customer needs.

The case study research highlighted that where there was a high degree of join-up and coordination between local employment services, the efficacy of the system in matching customers to appropriate provision (and therefore supporting their entry into employment) was seen to be enhanced. DWP should consider whether, in commissioning services, it is also possible to invest in ways to strengthen these local partnerships and ways of working (e.g. through co-location and/or data sharing arrangements).

DWP should work in partnership with policy owners (such as the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities) to consider how the transition from the European Social Fund to the Shared Prosperity Fund will affect these local partnership structures (and particularly whether it poses any risks to their sustainment), and the potential implications this has for the delivery of future employment support services.

Although the work of Partnership Managers was often praised by DWP staff and wider partners, DWP should continue to consider what long-term role Jobcentre staff can play in these partnership structures and how this fits with the Department’s aims and objectives. In some areas, non-DWP partners felt that their focus on inclusion and finding sustainable employment outcomes for the local population (both the inactive as well as the unemployed) was at odds with the Department’s perceived focus of moving customers into any employment as quickly as possible.

Where possible, customers should be signposted to support available to help with particular work barriers such as a lack of skills or financial difficulties. Similarly, support needs to be tailored to those with physical and mental health conditions as well as those with caring responsibilities to cater for their needs and flexibility requirements.

As most customers report continuous barriers to sustained employment or progression after completing the programme, these include high travel costs or lack of relevant skills to progress. options for ongoing support should be considered where appropriate to ensure any employment outcomes can be sustained long term.

In delivering future services, DWP should look at how existing contracts with providers can be used to respond quickly to changing labour market dynamics. By the time it became operational, some PfJ strands were not seen to respond effectively to the needs of DWP’s customer base. DWP should consider whether services can be adapted to best respond to the changing needs of the local population and address local labour market needs.

Across the case study research, common barriers to work entry that were not easily resolved included language barriers and health (particularly mental health conditions). Further training and guidance may be required to ensure that Work Coaches feel equipped to support customers with these needs. In terms of employer engagement, consideration should be given to how Jobcentre districts can best capitalise on the new employer relationships that were developed over the course of the pandemic.

Acknowledgements

This research was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). We were very grateful to the guidance and support offered throughout by the Research Team at DWP, in particular to Janet allaker, Iman Ezidy and Matthew Collins. We would like to acknowledge and thank former colleagues at Ipsos who contributed to this evaluation and report, including Patricia Pinakova, Morwenna Byford and Olha Homonchuk. We would also like to thank all the research Participants for giving up their time to participate in interviews and providing valuable information on their experiences and views.

Authors credits

Joanna Crossfield, Director, headed up the Ipsos team responsible for the research. Jack Watson, Research Manager, was responsible for the day-to-day management of the study. Grace Atkins, Senior Research Executive, worked on the fieldwork, delivery, and analysis for this project.

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| programme | The six in-scope DWP Plan for Jobs (PfJ) strands aiming to help Intensive Work Search customers get (back into) work |

| Strand | One of the six Plan for Jobs support strands aimed at different groups of Intensive Work Search customers |

| Customers | all customers receiving benefits from the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) |

| Participants | all DWP customers taking part in one of the Plan for Jobs strands |

| Non-Participants | all DWP customers eligible for but not engaged in any of the Plan for Jobs strands |

| Early Leavers | all customers who started a Plan for Jobs strand but did not complete it |

| Job Finding Support (JFS) | A minimum of 4 hours of support for those recently unemployed and claiming benefits for less than 13 weeks; (contracted strand) |

| Job Entry Targeted Support (JETS) | Up to 6 months of support delivered by Work and Health programme (WHP) providers aimed at those unemployed between 13 weeks to a year; (contracted strands) |

| Sector-based Work Academy programmes (SWAPs) | Short training and work placement linked to a current job vacancy in a specific sector or area of work |

| Kickstart | 6 months paid job placement aimed at 16- to 24-year-olds unemployed for 6 or more months |

| Youth Offer | Support for 16- to 24-year-olds provided through the Youth Employment programme (YEP), Youth Hubs (YH) and Youth Employability Coaches (YEC) |

| Restart | Up to 12 month contracted employment support, originally aimed at those unemployed for 12-18 months and now for those unemployed for longer than 9 months |

| ESOL | English for Speakers of Other Languages |

| Employer Advisor | DWP staff, based in Jobcentres, who work directly with employers to help them fill vacancies, advising on recruitment strategies and methods |

List of tables and figures

| Reference | Title | Chapter |

|---|---|---|

| Table 3.1 | Proportion of Participants and non-Participants within each [cluster] group | 3 |

| Figure 1 | Thinking about the programme, how much do you agree or disagree with the following? | 3 |

| Figure 2 | Why did you decide to take part in this programme? | 3 |

| Figure 3 | What, if any, barriers or challenges have you faced when taking part in the programme? | 3 |

| Figure 4 | How satisfied are you with the support you received/are receiving from the programme? | 3 |

| Figure 5 | How useful was the programme in helping you to find employment or progress in your career? | 3 |

| Figure 6 | What happened as a result of taking part in the programme? | 4 |

| Figure 7 | What happened as a result of taking part in the programme? | 4 |

| Figure 8 | What happened as a result of taking part in the programme? | 4 |

| Figure 9 | Thinking about your job, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with…? | 4 |

| Figure 10 | Overall, over the next 12 months how important is it for you to…? | 4 |

| Figure 11 | How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements? | 5 |

| Figure 12 | How long have you been doing this job? | 7 |

| Figure 13 | Thinking about your job, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with | 7 |

| Figure 14 | Overall, over the next 12 months how important is it for you to: | 7 |

| Figure 15 | Is there anything that makes it difficult to progress in your current job | 7 |

| Figure 16 | How useful was [strand] in helping you to find employment or progress in your career? | 7 |

| Figure 17 | How long have you been unemployed? | 7 |

| Figure 18 | Which, if any, of the following actions have you taken in the last 3 months? | 7 |

| Figure 19 | How much do you agree with the following statements? | 7 |

| Figure 20 | What would help to make it easier for you to find employment? | 7 |

| Figure 21 | Which, if any, of the following actions have you taken in the last 3 months? | 7 |

| Figure 22 | Categorisation of experiences of Participants and non-Participants in the wave 2 qualitative research | 8 |

| Table 10.1 | Overview of case study areas and rationale for selection | 10 |

| Table 10.2 | Case study sample profile | 10 |

| Table 10.3 | Start dates of strand Participants | 10 |

| Table 10.4 | Statements used in segmentation model | 10 |

| Table 10.5 | Profile of Participant segment groups | 10 |

| Table 10.6 | Profile of non-Participant segment groups | 10 |

| Table 10.7 | Sample breakdown of the wave 1 depth interviews | 10 |

| Table 10.8 | Sample breakdown of the wave 2 depth interviews | 10 |

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic and first national lockdown in March 2020, which placed restrictions on business activity and social movement, led to a significant economic shock. Claimant unemployment (the measure of people claiming benefits and required to be available and seeking work) increased by 69 per cent between March and April 2020 to 2.1 million (IES, 2020), driving a sharp increase in the number of people starting new claims for Universal Credit. Scenarios developed at this time by the Bank of England and the Office for Budget Responsibility suggested that the unemployment rate could rise to 10% and decline more slowly than GDP recovered[footnote 7].

The Government’s Plan for Jobs (PfJ), announced on 8 July 2020, set out a response to this crisis with more than £7 billion allocated for measures designed to support the UK labour market. The PfJ also included measures overseen by the Department for Education (DfE) that provided routes into work, apprenticeships, and traineeships. Aspects overseen by DWP aimed to help maintain job search intensity for the unemployed, improve job matching and brokerage for employers and jobseekers, and to develop the skills needed to fill vacancies. These were:

- rollout of a new Job Finding Support (JFS) service. A national offer for claimants who had been unemployed for 13 weeks or less, delivered online through private sector providers. The service intended to help claimants become familiar with current recruitment practices, utilise their transferable skills and develop a personalised job finding action plan. The service launched in January 2021 and the final referrals were made in January 2022.

- Kickstart, a programme providing six-month jobs, funded by the Government, for 16–24-year-olds receiving Universal Credit and unemployed for six months or more. The programme aimed to create up to 250,000 jobs for young people eliminating hiring costs while also improving workplace skills and providing employability support. It was open to referrals until the end of March 2022.

- commissioning of Job Entry Targeted Support (JETS) for claimants who had been out of work for between 13 weeks and one year. The provision gave claimants up to six months of support, including skills analysis and a job search action plan. JETS was launched in England and Wales in October 2021, commissioned through the Work and Health programme. In Scotland, the service began in January 2021. JETS was open to referrals until September 2022.

- the Restart programme, launched in June 2021, initially offered a 12-month personalised programme of support for claimants out of work for 12 to 18 months. The referral point was reduced to nine months of unemployment from January 2022. Restart does not operate in Scotland as support for long-term unemployed claimants is devolved.

- a more than doubling of places on Sector-based Work Academy programmes (SWAPs) and other measures (e.g. the Lifetime Skills Guarantee), to help jobseekers get the right skills for work. SWAPs are not available in Wales due to devolved responsibilities. Similar employment support was available funded through the Welsh Government, though it is not evaluated in this report.

- the Youth Offer was launched in September 2020 and replaced the Youth Obligation Support programme. The Youth Offer was initially available to 18-24 year olds and was later extended to 16-17 year olds in December 2021. The Youth Offer brings together three strands of support for young people; The Youth Employment programme[footnote 8] (YEP); Youth Employability Coaches[footnote 9] (YECs); and Youth Hubs which offer co-located and co-delivered services with a range of partners located in non-Jobcentre community space. The Youth Offer is intended to continue until April 2028.

These measures were supported by the recruitment of an additional 13,500 Work Coaches and an expansion of Jobcentre offices, through the rapid creation of new temporary sites.

Following a three-month suspension of any conditionality attached to benefit claims for customers actively seeking work during the early months of the pandemic, conditionality was reintroduced in July 2020.

There followed a period of changing national guidance with regards to social distancing, business closures and requirements for working from home for those who could. In England, all social distancing regulations were lifted in summer 2021. In Wales and Scotland, social distancing measures remained in place until early 2022.

The longer-term labour market crisis that was predicted by the Office for Budget Responsibility and The Bank of England as a result of the pandemic did not emerge. Other influences, such as an increase in economic inactivity, and the labour market effects of leaving the European Union, meant that for much of 2021 and 2022, the level of unemployment fell. By July 2022, the unemployment rate was 3.8 per cent and there were around 1.3 million job vacancies, about 50 per cent higher than before the pandemic. At this point, there were more job vacancies than people unemployed for the first time in 50 years (IES, 2022).

1.2. Research objectives

The multi-strand evaluation aimed to assess how well DWP’s parts of PfJ were able to respond to the sharp increase in unemployment in 2020 and meet the needs of unemployed claimants. The evaluation also aimed to explore how well employment services were joined up and how decisions on referral and targeting were made.

The research objectives for the case study strand were to understand how the PfJ provision supported claimants to find work and to explore the interactions of PfJ with local contexts. The case study research used a systems approach by focusing on interactions within and between PfJ provision, as well as interactions between PfJ provision and the wider offer beyond PfJ. The case study research aimed to highlight key interactions and interdependencies, identify any gaps in implementation, and surface reasons for varying engagement in PfJ strands between areas. The case study strand also offers a deep dive into how PfJ affected, and was affected by, structural changes in sectors and sub-regions, as well as how provision was delivered differently to reflect different local operating contexts and needs.

The research objectives for the survey and follow up qualitative strands were to explore the barriers, enablers and motivators to participating in the PfJ strands and to gaining employment. The survey also gathered customer feedback on PfJ and aimed to identify the differences between Participants and non-Participants and understand experiences and outcomes for Participants without a sustained work outcome. This research does not include any impact or cost-benefit analysis of Plan for Jobs provision, and therefore cannot definitively ascribe employment-related outcomes to participation in strands.

1.3. Methodology

A mixed methodology approach was taken to the evaluation, comprising:

- ten Local Authority case studies completed between October 2021 and August 2022

- two wave longitudinal survey of respondents who had taken part in one of the strand provisions (‘Participants’) and those who had not (‘non-Participants), achieving 8,325 interviews at wave 1 and 6,950 interviews at wave two, including 1,338 longitudinal interviews. Wave 1 fieldwork was conducted between 17 March and 10 April 2022 and wave 2 fieldwork between 1 November and 21 December 2022

- cluster survey analysis from unemployed subsample of Participants and non-Participants to better understand the different types of barriers to employment

- sixty follow-up qualitative interviews with both Participants and non-Participants drawn from the wave 1 survey sample conducted between September and October 2022

- sixty follow-up qualitative interviews with both Participants and non-Participants drawn from the wave 2 survey sample conducted in March and April 2023

More information on the Local Authority case studies, case study data analysis, the Participant and non-Participant survey including the sampling and weighting approach, cluster analysis and follow-up qualitative interviews can be found in the appendix.

1.4. Interpreting the findings in this report

This research presents a snapshot of Plan for Jobs Participants. The sample for the survey and follow-up qualitative interviews was drawn from customers who had started their provision between December 2020 and November 2021. Restart was not included in the survey samples for this research (to enable its main evaluation to take place) and is therefore covered in less detail in this report. Intensive Work Search Participants include those who are waiting for a Work Capability Assessment (WCA), or for the outcome of a WCA. The outcome of this may change their work search requirements.

The survey data for each strand (excluding Youth Offer) were weighted to their respective Participant profile. The survey data for non-Participants were weighted to the profile of all eligible customers not engaging with Plan for Jobs. In addition, all survey data were weighted by gender, length of claim, and region. Early leavers data is unweighted.

Only findings from the survey which are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level have been reported as different in the commentary (although charts and tables may include non-statistically significant differences). all tables and charts report weighted data and include the unweighted base for reference.

The survey results are subject to margins of error, which vary depending on the number of respondents answering each question and pattern of responses. Where figures do not add to 100 per cent, this is due to rounding or because the question allows for more than one response.

Qualitative research is detailed and exploratory. It offers insights into people’s opinions, feelings and behaviours. all Participant data presented should be treated as the opinions and views of the individuals interviewed. Quotations and case studies from the qualitative research have been included to provide rich, detailed accounts, as given by Participants.

Qualitative research is not intended to provide quantifiable conclusions from a statistically representative sample. Furthermore, owing to the sample size and the purposive nature with which it was drawn, qualitative findings cannot be considered representative of the views of this PfJ cohort as a whole. Instead, this element of the research was designed to explore the breadth of views and experiences, in order to develop a deeper understanding of attitudes towards progression and support preferences.

2. Plan for Jobs in the Context of Pre-existing Employment Support

This chapter outlines the varying local contexts into which the PfJ strands were introduced across the 10 case study areas included in this research. It provides an insight into the pre-existing employment support landscape in these areas and the organisational and partnership structures that supported this provision. Drawing on Jobcentre staff, partner and customer interviews, it presents findings on how the introduction of the PfJ strands affected and interacted with this system. The case study research was completed between October 2021 and August 2022.

The chapter is split into two sections. Section 2.1 outlines the nature of the local employment support system that was present across case study areas when PfJ was introduced. Section 2.2 provides an overview of the how the introduction of PfJ interacted with local Jobcentre staffing structures and ways of working, as well as local partnership structures (including work with employers) across case study areas.

The findings in this section draw on the 10 case studies from Local Authority areas across the three nations of Great Britain. They covered a range of different socio-economic contexts from metropolitan cities (Manchester, Glasgow, Cardiff); to ex-industrial urban (Blackburn, Middlesborough, Peterborough, Waltham Forest); and ex-industrial rural areas (Cornwall, Rhondda Cynon Taff, North Lanarkshire).

2.1. Employment Support Landscape

2.1.1. Local labour market context

At the time of the research, vacancy rates were viewed by DWP staff and partners to be high across all areas, with the most opportunities in urban city locations. The range of vacancies available to customers during this period were similar across areas and included: factory and warehouse roles, logistics (with HGV drivers in particularly high demand), construction hospitality and retail, health and social care, administration, and security.

2.1.2. Local employment support – devolved powers and funding

Across the areas included in the case study research, additional provision was available to customers beyond PfJ provision. The extent of this varied between areas. The most commonly mentioned funding source for additional provision at the time of the research came from the European Social Fund (ESF). This was widespread in the Scottish and Welsh case study areas, as well as areas of England with high levels of deprivation (Middlesborough, Cornwall).

Areas with significant devolved powers, particularly for skills funding (Wales, Scotland, Manchester and London) or spending powers related to their Adult Education Budget (combined authority areas – Manchester and London) could contribute additional spending to employment support programmes. In some cases, this included coordinating their spending with ESF funding to enhance the scope of their offer. Where they were in place, these additional powers and funds were used to deliver localised employment provision aimed at providing tailored and flexible one-to-one employment support to groups who faced the most significant barriers to labour market participation. These were 16- to 24-year-olds, the long-term unemployed, and/or individuals who faced complex barriers to employment (e.g. health, childcare responsibilities). Where this support was present, Jobcentre staff generally said that they had made good use of it prior to the introduction of the PfJ measures.

At a strategic level, where additional, local, employment support provision was most prevalent, this supported the development of strong models of partnership working between Local Authorities (whom this funding was primarily channelled through) and DWP district-level staff. In many cases, these partnerships worked collaboratively to share local vacancy information and identify training needs in the area. The Manchester combined authority area was also able to share data internally (though not with DWP) on locally administered and devolved programmes using a centralised system. This enabled them to look at referral trends and levels of demand for services, to inform the future planning of support.

In some cases, devolved funding and powers were used to address perceived gaps in PfJ provision. For example, in Glasgow, the Local Authority used funding from the Scottish Young Person’s Guarantee[footnote 10] to create a scheme that replicated and ran in parallel with Kickstart, but with broader eligibility criteria to make the scheme accessible for school leavers (16-17 year olds) and young people who were unemployed but not in receipt of UC.

2.2. Overview of Plan for Jobs Support System

This section provides an overview of the interdependencies between the DWP-funded elements of PfJ, Jobcentre staffing structures and ways of working, as well as local partnership structures across case study areas.

The Jobcentre staffing structures used to implement and refer to PfJ are first described, including the new roles created. The training and awareness raising undertaken to assist staff to understand and make referrals to PfJ strands are then discussed, before detailing what affected customer referrals to PfJ strands, and customer starts.

2.2.1. Staffing structures

The number of Jobcentre offices in the Local Authority areas covered by the case study research varied considerably (from 1 to 9 sites). Jobcentre offices also varied substantially in size, accommodating anywhere between 20 and 150 members of staff.

Following the onset of the pandemic, new roles in Jobcentre offices were created and new staff recruited to support the large influx of new customers and delivery of the new employment support programmes. This included the recruitment of additional Work Coaches, as well as the creation of new job roles such as Kickstart District Account Manager, Youth Hub Work Coaches and Youth Employability Coaches.

While Employer Advisors (EAs) were typically based in Jobcentre offices and worked with local employers to address their recruitment needs, the other roles worked at district or cluster level, with responsibility for more than one office. The nature of developments to staffing structures depended on the size of the population covered by the Local Authority area, with areas with larger volumes of customers seeing more widespread changes and the creation of more new roles.

The number of new staff recruited at once presented challenges in training and seemed to have influenced the continuity and quality of customer experience. It was common for customers to say they had seen several Work Coaches during their claim, and that this sometimes presented a challenge in establishing trust.

The location in which services were provided also changed following the onset of the pandemic. Providers communicated with Jobcentre staff and customers remotely during periods where COVID-19 social distancing restrictions were tighter. As restrictions eased, some external providers of PfJ provision returned to Jobcentre sites on a regular basis. This was seen to be positive for customers as it supported a better quality referral and handover process and allowed provider staff to build a better relationship with customers.

After January 2021, Jobcentre districts experienced further staffing and resourcing changes. In several of the areas, new Jobcentre sites opened following expansion (e.g. North Lanarkshire, Middlesbrough, Waltham Forest). Some of these were Rapid Estate Extension programme (REEP) (temporary) sites. Other areas had opened specialist facilities, such as Youth Hubs, and in Motherwell a Resource Suite had opened which created a space for collaboration for partners. Site changes could increase travel times. For example, several customers in North Lanarkshire reported that the opening of a new site meant their journey to the Jobcentre office was now longer.

2.2.2. Staff awareness of PfJ

The introduction of PfJ required Jobcentre staff to quickly learn a large amount of information. Initially, staff felt the scope of knowledge and the pace of learning required was overwhelming. Gradually, and as strands developed into a definitive form, staff felt they gained a fuller understanding. However, customers and providers suggested that, throughout delivery, Jobcentre staff understanding of eligibility criteria and the specific support contained in each strand was not consistent.

When PfJ strands were introduced, training sessions were regularly delivered by provider staff. In the case of Kickstart, customer-facing staff were informed of ongoing developments during internal meetings or over email and relied on informal knowledge-sharing among colleagues to process key points from regular changes in guidance.

In several case study areas, Jobcentre managers delivered sessions on how to complete good quality referrals after having observed inappropriate referrals. Others delivered training following recruitment waves to upskill new staff. Existing Work Coaches or Team Leaders also acted as single points of contact for specific PfJ strands as they were introduced. Besides liaising with contracted providers, they were responsible for sharing information with operational staff, responding to staff questions about the strand, and monitoring referrals.

Generally, staff developed a good understanding of the support of most relevance to their customer group. However, as several PfJ strands came to an end, and Jobcentre offices were restructured as a result, it was unclear whether staff were appropriately trained on other PfJ strands as they increased in relevance to their caseload. For example, some Youth Work Coaches were not trained on JETS initially as they had focused on Kickstart. They felt that their knowledge of JETS was not comparable to that of colleagues.

To address knowledge gaps on particular provisions, areas used targeted forms of awareness-raising for Work Coaches. In one area, staff had visited a local community provider to see the delivery of their provision first-hand; in another case, providers used Jobcentre sites to carry out speed-networking sessions with Work Coaches.

Communication channels for updating staff about job vacancies and vacancies on provision were seen by staff as broadly effective. Information about Kickstart jobs and SWAPs was usually communicated to customer-facing staff by EAs. Some Jobcentre offices had created Microsoft Teams channels for this purpose, others used a digital note taking app (OneNote) and others relied on daily or weekly internal meetings.

2.2.3. Customer referrals and starts

This section outlines staff experience of making customer referrals to PfJ strands, before examining the influences on referrals and starts.

Experience of making referrals

The demographics of caseloads impacted staff experience of referral processes meaning that these varied across case studies and strands. For instance, in areas with a high proportion of customers with health conditions, staff felt they required a longer appointment time than was available to provide sufficient support during the referral process to ensure accessibility. This was mirrored in the experiences of customers. For example, mental health conditions prevented customer starts, particularly amongst younger customer groups or vulnerable people who found it difficult to meet new people or travel to new places. Some Jobcentre staff and customers did not see the referral process to PfJ strands as being sufficiently supportive to meet these needs.

The referral experience for Restart was considered time intensive during its initial rollout in late 2021 and early 2022. Work Coaches reported that after explaining the provision to the customer, they were required to liaise with a Restart Single Point of Contact (SPOC) and advisors to first establish capacity for a referral, and then arrange a warm handover. Work Coaches stated that the three-way handovers (involving Work Coach, customer and provider) were a positive influence on Restart starts, enabling customers to have a supported handover, and improving communication between Work Coaches and contracted provider staff. However, during this initial period Work Coaches reported that the appointment and administration time they had available was insufficient to complete these activities.

The timing of the introduction of Restart, when unemployment was lower than had been forecast, in combination with a drive to meet the expected number of referrals led to inappropriate referrals in some cases. In several case study locations, staff said eligible customers were hard to identify based on the initial eligibility criteria or were very distant from labour market (e.g. due to long-term health conditions).

The Youth Hub strand of the Youth Offer was described in several case studies as having an effective and smooth referral process. For example, the secondment of Youth Work Coaches to Youth Hubs facilitated a warm handover. This was seen to be an effective means of streamlining the registration process and Work Coach to start building a relationship of trust with the young person and support their continued engagement straight away.

The Youth Employability Coach and Youth Hub strands of the Youth Offer, although valued, were part of several referral options for young people in some areas resulting in uncertainty about the most appropriate referral routes. In one area, other referral options were available through the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) and ESF funding and support and were widely used by Work Coaches working with young people. In many cases, this provision was favoured due to a wider range of barriers addressed through this support and frequent and well-established positive feedback from customers. In another area, this was echoed by wider partners, who felt that the Youth Employability Coach and Youth Hub strands of the Youth Offer had complicated an extensive provision landscape for young people.

Influences on customer referrals to PfJ strands

There were several influences on Jobcentre staff referrals to PfJ strands which fluctuated over time as strands were introduced. For example, JETS providers in several areas saw their referrals decline following the introduction of Restart; and in certain areas Jobcentre staff felt obliged to meet JETS profiles and referred to this strand rather than JFS.

Changes to staffing, for example due to expansion or turnover, was identified as another factor influencing referrals. In some offices, these changes affected Work Coaches’ collective knowledge and confidence about the best referral routes for customers. Staff in offices with a lot of new starters were not as well placed to draw on colleagues for advice and support as offices where new staff worked alongside those with more experience.

The perceived quality of PfJ provision during the rollout phases impacted referrals. In some locations, quality concerns initially resulted in lower numbers of referrals. Where customer feedback was initially poor, this affected future staff referrals and their likelihood to recommend the provision to other customers on their caseload. However, staff also acknowledged that customer feedback about provision could change over time and improve once it became more established. There was also evidence that a positive reputation among customers increased the chance they would recommend support to friends and family also seeking work. There were examples of customers prompting Work Coaches to see if they could be referred to specific strands.

The perceived likelihood of the provision leading to an employment outcome for a customer could influence referrals. For example, in several areas, SWAPs were viewed as a useful provision for giving customers work experience and employment-related training in different sectors, which in some cases could lead directly to employment. In one area a SWAP tool helped staff to effectively and quickly identify provision that was best suited to a customer, and staff frequently made referrals to SWAPs in this case study. However, some staff interviewed in a few case study areas were reluctant to refer to SWAPs as they perceived the strand as having limited success in gaining employment outcomes for customers:

Jobcentre staff, said:

I think a lot of the SWAPs say that there will be interviews and jobs offered at the end and I don’t really think I’ve had any that have had a job offer on a SWAP so I think maybe people who have done them once maybe wouldn’t do a SWAP again because it hasn’t led to anything even though it might have enhanced their CV.

Jobcentre staff were sometimes unsure about customer eligibility for PfJ strands where customers had taken part in other provision recently. While staff tended to prioritise referrals to DWP-funded provision where customers were eligible, they were unclear about customer journeys across the entire scope of support. Staff felt it could be more clearly articulated and explained during the introduction of new strands how they complemented and worked within the wider employment support system. Introductions tended to focus on the mechanics of the strand being introduced rather than how it fitted into the wider system of support.

The extent to which staff viewed PfJ strands as giving additional options to customers affected referrals. In some areas, staff stated that customers were already well served by existing provision. For example, in a Welsh case study, the Communities for Work programmes[footnote 11], offered one-to-one employability support and had well-established referral routes. Consequently, staff reported referral numbers were lower than profiled for JFS and JETS during the initial stages of delivery.

Jobcentre staff felt that on balance, referrals were based on customer need, including work readiness and desired work outcomes, as part of an aim to provide personalised support. However, staff in some case studies reported feeling pressure to meet referral profiles to PfJ strands. Jobcentre staff stated that this affected their ability to consistently make customer-led referrals due to pressure to meet profiles. For example, in some case studies, expectation to refer to Restart during its initial rollout (late 2021/early 2022) was felt particularly acutely, however, this perception was not limited to Restart. Work Coaches reported that referral profiles for mandatory provision were a higher priority than voluntary programmes and reported feeling pressure to meet referral profiles over any other metric at this time. Jobcentre managers also spoke of regularly reviewing referral profiles for their office and being held accountable for meeting these by their District managers. In cases where referral profiles were not being met, they would consult with staff, seek to understand why and put improvement plans in place to gradually increase the number of referrals to a particular programme over time. Examples were given of putting improvement plans in place for referrals to JETS as well as to support the take-up of Kickstart provision. Accordingly, pressure to meet referral profiles was reported to be a significant influence on referrals, and one that was sometimes seen as being at odds with the aspiration to provide customer-focused support.

In some cases, staff felt that there was a gap between the customer demographics and the strand profile and capacity. For example, there was some difficulty reaching strand profiles in one case study because eligible customers included a high proportion of customers with health conditions and ESOL requirements which staff felt would benefit from other provision as priority:

Jobcentre manager, said:

I think [Work Coaches] find [reaching profiles] challenging because of the makeup of the caseload… A lot of [customers] were deemed not suitable straight away because they were ESOL… it’s the same with health.

The importance of Jobcentre staff and the subcontractor having a strong positive partnership had a significant role in the decision to refer eligible customers to PfJ strands. Contracted providers found it helpful to work from Jobcentre offices on a regular basis to facilitate communication with Work Coaches.

Influences on starts

Whether customers started on a particular PfJ strand was influenced by a range of factors. In the case of SWAPs, for example, customer starts were seen to be influenced by the perceived quality of opportunities available, and how well these matched customers’ desired work goals. Some customers felt they were encouraged to participate in SWAPs by their Work Coach, but the specific provision they had been referred to lacked alignment with their work goals and interests.

Alignment to customer work goals was also important to customers starting a Kickstart job. In some locations, customer-facing staff reported being given additional time to match customers with Kickstart vacancies, to make referrals, and deliver some light-touch employability support to young people, which was felt to enable good matches between customers and the available positions. The speed of the Kickstart referral process was seen to be effective in supporting customers to take up the placement by providing an efficient and positive experience for them.

Another influence on customers starting on PfJ strands was effective customer monitoring and communication. Areas that had monitoring systems in place described them as useful in tracking the take-up of customer referrals. In one area for example, Jobcentre staff would set follow-up reminders 15 days following an initial referral to check on customer progress. In the case of customer disengagement or failure to start the provision, Work Coaches would be notified by the provider and would increase the frequency of their appointments with the customer.

In several areas, staff attempted to pre-empt barriers to customers starting on PfJ strands by explaining to customers what communication they could expect from providers following a referral. For example, staff would inform customers that calls from providers may appear as an unknown number, or that providers would call customers to remind them of upcoming appointments. The timeliness of a referral was also seen to influence whether customers successfully started a PfJ strand. Jobcentre staff reported that it was helpful to make referrals a week before provision started; any further in advance would mean customers were less likely to start as their circumstances and motivation could change.

On the JETS strand, staff felt that the remote nature of this provision contributed to customer disengagement, and lower starts. To address this, in one area, staff provided supporting information about JETS to customers before their initial call with the provider. This practice was seen to work well in getting customers to consider whether the support was suitable for their needs and was felt to have a positive impact upon customer starts.

The remote delivery of JFS was also reported to affect starts across case study locations. Additionally, customers who lacked IT skills said this affected their confidence and motivation to engage with JFS given the strands use of digital platforms. Staff commented more generally that in-person support may have higher start rates than support delivered virtually. Some staff and stakeholders suggested that ignoring a phone call, email or text was easier for customers than missing an in-person appointment.

Subcontracted manager, said:

I think [remote delivery] gives people an easy excuse not to turn up. It’s easier to miss a call than miss an appointment that you have to be face-to-face for.

However, in several case study locations, some customers reported instances where they were referred to a PfJ strand but were given limited, or no information about what the provision entailed. This could contribute to customers not wanting to engage in the provision.

2.2.4. Partnerships and joint working

The interconnectedness and interdependencies between employment support services and related support is demonstrated through Jobcentre joint working with employers, careers services, training providers, and health services. Jobcentre staff worked with other public sector organisations, as well as voluntary and community sector organisations and the private sector to create a local environment and employment support system that would facilitate customers to find work.

The emphasis and scope of partnerships varied between areas, depending on customer need, and resources. As noted in section 2.1, local and national government had significant involvement in the co-ordination and development of employment support, especially where they had devolved powers and/or received substantive European monies.

The main findings from across the case studies showed that:

- the introduction of the Kickstart scheme alongside tight labour market conditions drove employer engagement across areas. This brought new employers into contact with the Jobcentre for the first time. This was further supported through the expansion of SWAPs and employer engagement work being undertaken by providers delivering PfJ strands (i.e. JETS). This engagement brought with it opportunities and challenges. Jobcentre and provider staff attempted to work with employers to remove barriers to accessing their job vacancies for customers. This could include negotiations around the entry criteria as well as travel arrangements and agreed shift times.

- the use of careers services was inconsistent across areas. Customers who were new or were returning to the labour market, or who were seeking a new occupation, stated that they would have benefitted from speaking with someone about possible job options and the pathways to achieving these goals. However, local careers services were not always used in this way, unless they had additional contracts to deliver and/or were strongly integrated into area partnership networks, which in turn gave them a greater presence and voice in the local employment support system. In several cases, Work Coaches would use their local careers service to support customers with their CV and interview skills where needed. However, with the commissioning of the JFS programme, which offered similar support, the use of careers services for this purpose was seen to decline.

- partnerships with education providers were present in all areas. This provided customers with access to short training courses to increase their work readiness and gain necessary licences in some cases (e.g. CSCS card, SIA licence). However, long-term skills development programmes such as traineeships and apprenticeships were not a consistent part of this offer.

These findings are discussed in more detail below.

Employer engagement during the delivery of PfJ

Kickstart

Across all areas, the introduction of PfJ led to an increase in engagement between Jobcentre staff and local employers. The driving force behind this was Kickstart, which was seen as a high-profile national initiative. It gave employers including Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) a reason to contact and work with Jobcentre offices, given their role in helping to advertise and promote vacancies to customers and support employers with recruitment to positions. Given the scale and profile of this strand, frequently these employer relationships with the Jobcentre were new, and encompassed a variety of sectors and positions. To support the management of employer relationships created by Kickstart, Jobcentres increased capacity at a district and office level by establishing Kickstart District Account Managers as well as EA roles.

A common challenge encountered across all case studies relating to Kickstart, was employers having unrealistically high expectations about the skills and experience of recruits. Jobcentre staff spoke of receiving vacancies for roles that required several years’ experience, or qualifications up to degree level. In these instances, staff worked with employers to explain that the purpose of Kickstart was to provide opportunities to young people at risk of long-term unemployment. In these cases, employers were encouraged to look again at their job descriptions and ensure the placement was accessible to customers. Despite this work, some Jobcentre staff still felt that Kickstart could have done more to provide opportunities to young people with multiple barriers to employment, as opposed to those who were relatively work ready. It was felt that, with more time and planning, the scheme could have had a stronger emphasis around inclusivity, particularly enabling opportunities for disabled customers. In one of the case study areas this concern was partly tackled by DEAs working with Kickstart employers to discuss feasible accommodations to support customers and promoting the Access to Work scheme, but this was not consistent between areas.

SWAPs

The number of SWAPs available was expanded as part of the PfJ. While this was not always visible to Jobcentre staff interviewed in some case study areas at the time of the research (October 2021 - August 2022), SWAPs were widely used across these locations (excluding Wales) and were viewed to be an effective recruitment tool for different employers. For EAs, SWAPs were an important part of the offer and in some areas were often the first strand mentioned when trying to secure employer engagement. In practice the SWAP model was flexible, and more flexibilities on how the model was implemented were granted during the pandemic. For example, in areas where SWAPs were delivered by smaller employers, following an initial health and safety briefing session training could take place on the job. In these cases, customers gained experience of working in the role they were trying to secure almost immediately, with opportunities provided for job shadowing. Jobcentre staff generally regarded SWAPs positively: the scheme was seen to be an effective means of quickly securing job outcomes for customers. However, some staff noted that suitable SWAPs were not always available at the times needed by customers, while others questioned the quality of the employment outcomes secured by some customers, particularly where their employers were recruitment agencies.

Employer links through other PfJ programmes

Outside of the Jobcentre, providers delivering other PfJ strands could also have employer connections that customers could capitalise on as part of their job-search. Across all areas, for example, providers delivering JETS had local employer contacts that they would use to source and advertise vacancies to customers. These links were managed by a dedicated employer account manager. According to provider staff, another advantage of this close relationship was that employer account managers could advocate on a customer’s behalf, more easily get them shortlisted for interview and could seek constructive feedback from their interview if they were unsuccessful.

Tightening labour market conditions

The tightening of the UK labour market (rising levels of job vacancies) drew new employers to engage with the Jobcentre to help address recruitment challenges. Across the case study areas, Jobcentre staff drew on their recent knowledge of collaboration with employers from Kickstart, and extended capacity for employer engagement, to support employers to fill vacancies using similar methods. For example, across all case study areas, Jobcentre staff noted an increase in the number of jobs fairs they facilitated compared to before the pandemic. To support jobs fairs, staff could make the recruitment process easier for both employers and customers by completing an initial customer screening and shortlisting. This meant that the job fairs were spaces where employers could focus on recruitment and spend time interviewing customers. In some cases, this resulted in job offers on the day, or an invitation to a second interview following a short conversation (10-15 minutes) at the job fair. In some areas, job fairs were felt to be most effective where they were sector specific as this helped ensure that attendees had a genuine interest and motivation in taking up the roles available.

Tight labour market conditions enabled Jobcentre staff to try to negotiate with employers on the accessibility of opportunities, overcoming barriers to work relating to transport and health in some instances, although these were the exception rather than the rule. In some cases, Jobcentre staff gained experience of negotiating with employers on these topics as part of Kickstart, before applying it to their practice more broadly. For example, staff spoke of seeking flexibility from employers on shift start times to make opportunities more accessible to customers who relied on public transport or had childcare responsibilities. Jobcentres and partners supporting employers to recruit customers with health conditions led to targeted employer events for those willing to make adaptations as a way of seeking to address a widening gap in outcomes. Such employer events were seen as effective opportunities to improve outcomes for customers with health conditions.

Jobcentre staff, said:

An employability event about disability for employers and it’s for all Scotland in Glasgow and we got 150 employers already signed to come along. It’s about trying to get people with health conditions an opportunity into work.

Outside these examples, Jobcentre staff reported a mixed picture of employer willingness to adjust recruitment practices or adapt roles for customers with health conditions and/or disabilities. For example, in one area, Jobcentre staff discussed that the process for moving customers with health conditions into work was lengthier, as liaising with employers on reasonable adjustments took time and some employers wanted to fill vacancies more quickly.

Integration and delivery of careers services during PfJ

Government-funded careers services are devolved, with different arrangements and branding in England (the National Careers Service), Wales (Careers Wales), and Scotland (Skills Development Scotland). In case study areas, there were also organisations across the voluntary and community sector, which provided support for customers to identify their skills, improve CVs and provide interview and application guidance.

The extent to which careers services were well-linked with the Jobcentre varied between case study areas. How Jobcentre staff used careers services to help customers also differed, reflecting the different types of intervention that careers support can provide. Referrals were made for reasons such as seeking information about courses, to tailor CVs for specific job applications and identify transferrable skills. However, Jobcentre staff were not consistently aware of the variation in types of support that careers services offer.

Customers, especially those starting work and leaving education, returning to work after time off, or seeking to move into new sectors (for example due to changes in job availability due to the pandemic), reported that more detailed and extensive careers interventions would have been helpful. For example, in one case study several customers said career support was not provided by Jobcentre staff, and they felt encouraged to apply for jobs outside of their work interests. There were examples where customers felt they would have benefitted from career counselling, including guidance on how to change sectors and plan to work towards a more sustainable and life-long career. Customers reported doing their own research but felt they did not know where to look or which guidance to follow.

Kickstart Participant, 16 to 24, England, said:

[I would like] just to get some advice to try and see what type of career path I should go down, maybe some advice if I am looking into one specific career path how I should go about it.

There were examples across the case studies where partnerships with careers services were strong. Where organisations contracted to supply careers services held contracts on other funding streams, this was seen by Jobcentre staff to be helpful to ensuring joined-up and integrated service delivery with opportunities for cross programme referrals. In one case study where careers and Jobcentre staff worked particularly closely, staff at careers services were part of several partnership boards and delivered a monthly newsletter to Jobcentre staff to keep them updated with changes to provision. Jobcentre staff in this area reported feeling confident about the purpose and role of careers services. The good integration of careers services with Jobcentres in the area was reflected in the customer interviews, several of whom had received careers support.

Introduction of JFS and its effect on the use of careers services by Jobcentres

When the Job Finding Support (JFS) strand of PfJ was introduced, Jobcentre customer-facing staff across all case studies noted that they became less likely to refer to government-funded careers services than previously. In case studies undertaken in 2022, after JFS stopped taking referrals (January 2022), Jobcentre staff reported their referrals to other government-funded careers services increased as a result.

The influence of JFS on the number of Jobcentre referrals to careers services was compounded during the early months of its operation by the national lockdown. Prior to the pandemic co-location had been commonplace, with careers staff often working from Jobcentre offices. However, during the pandemic, staff from careers services were generally unable to do so. This physical distance was an added reason cited by staff for a fall in referrals to careers services while JFS was available. The large number of newly recruited Work Coaches was also cited as a cause. Newly recruited Work Coaches did not have existing relationships with careers workers, and careers staff found it challenging to build awareness and understanding of their services during a period of high workloads and remote working.

The effect of JFS on careers services locally was tempered, again, by the strength of local working relationships and the level of integration and joint working between national careers services, DWP and Jobcentre staff in each area. In the Welsh case studies there was a history of joint-delivery of Welsh Government programmes by Careers Wales and the Jobcentre, for example[footnote 12]. Jobcentre staff felt that the closeness of these ties and day to day working relationships meant that when the JFS strand was introduced, referrals to careers support remained relatively consistent.

Education and training providers

Throughout the case study areas, education and training providers worked with Jobcentres to deliver short vocational courses, ESOL, and SWAPs to customers. The courses aimed to increase customer skills and employability and support their job entry. Generally, Jobcentre and provider staff reported being able to find opportunities for customers to increase work readiness through training and qualifications. Frequently accessed short courses included those to gain licenses, such as Construction Site Certification Scheme (CSCS) cards, HGV licenses, Security Industry Authority (SIA) licenses, first aid, and manual handling qualifications, alongside courses for building confidence, resilience, supporting mental wellbeing and developing soft skills such as communication.

Apprenticeships and traineeships as routes into work were less utilised by Jobcentre staff across all case study areas when working with customers. This was because of a reduction in the number of opportunities available during the delivery period, a result of the effect on work environments of social distancing and the uncertain economic outlook. This intersected with lack of clarity amongst Jobcentre staff about which providers might enable customers to access these options.

When Asked about partnerships with education and skills providers, Work Coaches discussed the benefits of the Youth Hub as a space for presenting the range of support to customers. Staff felt apprenticeships and traineeships had a place within this context. In one Youth Hub, two local providers provided links to apprenticeships and traineeships for interested customers. In another Youth Hub based at a college, there were regular meetings between Jobcentre and college staff to discuss recruitment onto courses.

Based on the evidence collected from Work Coaches about the nature of the skills provision they promote to customers and the disruptive impact of the pandemic on work-based learning opportunities, the consistent integration of skills-based routes to work within employment support appeared to remain a challenge.

3. Plan for Jobs Customer profiles and journeys

This chapter covers the characteristics and profiles of Participant and non-Participant customers and how these characteristics could act as a barrier to finding work. The characteristics are representative of the cohort at a particular snapshot in time, rather than across the whole PfJ period. The chapter outlines the typical customer journey through each strand and discusses how employment-seeking activities (from customers’ points of view as well as wider feedback from staff, providers and local stakeholders) interacted with support received from outside the Jobcentre. Furthermore, the chapter discusses barriers to taking part in PfJ, reasons for leaving early and satisfaction with the strands before discussing the characteristics and specific barriers of unemployed customers.

Findings in this chapter are based on descriptive and cluster analysis of the quantitative survey data from 8,325 completed survey interviews in wave 1. More detailed information and a breakdown of interview responses can be found in Appendix 2.

3.1. Plan for Jobs customer profiles

Age and length of time claiming Universal Credit were conditions of participating in some of the strands. For example, Kickstart was for 16- to 24-year-olds and JFS for those claiming less than 13 weeks. In these cases, these reflect the design of the strand, rather than providing insight into the participating population. Where this is the case, these qualities have not been reported on.

Around half of Participants had a physical or mental health condition or disability. A smaller proportion faced barriers to employment relating to their caring responsibilities, language skills or other barriers.

Out of the five provision strands studied, Youth Offer Participants had the highest proportion of physical and mental health conditions or disabilities (63%). One in ten (10%) reported having physical health conditions, 33% reported having mental health conditions and 20% had both.

Across the provision strands, SWAPs and JFS Participants had the highest number of Participants who spoke English as a second language (25% SWAPs, 26% JFS). Around a quarter (26%) of non-Participants spoke English as a second language. Amongst early leavers, this was around one in five (19%).

Over 3 in 10 of SWAPs, JFS, JETS, Youth Offer Participants and non-Participants were from an ethnic minority background.

3.1.1. Kickstart

Kickstart was a 6-month job funded by the Government. It was targeted at 16- to 24-year-olds on Universal Credit who had been unemployed for 6 months or more. On this programme, the employers were responsible for providing employability support. The Kickstart Participant profile is outlined below:

Kickstart profile

| Demographic | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Male | 52% |

| Female | 48% |

| English as a second language | 11% |

| Physical health | 10% |

| Mental health | 29% |

| Physical and mental health | 12% |

| Ethinic minority | 26% |

| Caring responsibilities | 11% |

| Based in London | 22% |

3.1.2. Sector-based Work Academy programmes (SWAPs)

Sector-based Work Academy programmes (SWAPs) are for Jobseekers claiming either Universal Credit, Jobseeker’s allowance (JSA) or Employment and Support allowance (ESA). Participants gain work experience of up to six weeks with an employer in the industry, where new skills can be learnt on the job. Placements are typically in care, construction or warehouse work, the public sector or hospitality. The programme consists of three parts: pre-employment training, work experience in the sector and a job interview or help with applications[footnote 13]. SWAPs Participants in this sample were UC claimants only. The SWAPs Participants profile is outlined below:

SWAPs profile

| Demographic | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Male | 53% |

| Female | 47% |