Overcrowding in South Asian households: a qualitative report

Published 15 December 2022

Applies to England

Foreword

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) recently commissioned NatCen Social Research to conduct research to explore overcrowding in South Asian households. The English Housing Survey (EHS) indicates that British Bangladeshis and Pakistanis are particularly affected by overcrowding, with British Bangladeshi households 12 times more likely than those from white British households to face it (British Bangladeshi 24% vs white British 2%) (MHCLG, 2020).

However, there is a lack of research that explores issues of overcrowding from the perspective of the South Asian people affected. To address this evidence gap, this research focuses on the experiences of people from South Asian backgrounds and will be used to help shape DLUHC housing policies.

The research used a multi-stage qualitative approach to better understand why overcrowding is more prevalent among South Asian households in England. This included desk research and secondary analysis of data on overcrowding alongside interviews with key stakeholders to outline the scope of the issue. This was then followed by depth interviews with members of South Asian households aimed at capturing the experiences of those affected by the issue. Finally, focus groups were conducted, in which NatCen asked participants for their ideas and potential solutions. These findings will form a useful part of the evidence base on which future DLUHC policy development will draw.

I would like to thank the research team from NatCen, led by Rezina Chowdhury, as well as Dr Jo Britton from the University of Sheffield, Dr Asma Khan from the University of Cardiff, and Tracey Bignall from the Race Equality Foundation for advising on the research in its early stages.

I would also like to thank the participants from British Bangladeshi and Pakistani households who gave their time to take part in interviews and focus groups; Local Authority housing staff, Registered Social Landlords and representatives from homelessness/housing charities who responded to requests to be interviewed during the project; and finally, the policy and analysis teams in the department, who provided feedback and insights throughout.

The Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities is committed to research and evidence building that underpins future policy development. It will continue to build on the evidence base for overcrowding and seek to further amplify the voices of those most affected.

This project also demonstrates our commitment to fostering close links with external academics and organisations to ensure that commissioned research continues to play a prominent role in wider policy debates.

Stephen Aldridge

Chief Economist & Director for Analysis and Data

Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many people who have been involved in this project: the individuals who generously gave up their time to take part; Criteria Qualitative Fieldwork and Agroni Research for carrying out participant recruitment; and the following stakeholders for contributing to the research:

- Arawak Walton Housing Association

- BME National

- Brent Council

- Crisis

- Lambeth Council

- Manningham Housing Association

- Notting Hill Genesis Housing Association

- Poplar HARCA

- Shelter

- Tower Hamlets Borough Council

- Tower Hamlets Homes

Further queries

This report was produced by Olivia Lucas, Eleanor Woolfe, Joshua Vey, Eliska Holland, Monica Dey and Fatima Husain at NatCen Social Research in collaboration with DLUHC.

The responsible analyst for this report is Emine Yeter, Housing and Planning Analysis Division, DLUHC. Contact via ehs@levellingup.gov.uk.

1. Executive summary

1.1 This report presents the findings of a study commissioned by the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) exploring overcrowding in South Asian households. The overall objective of the research was to provide a strong evidence base to allow DLUHC to build a more nuanced picture of overcrowding among those from South Asian backgrounds.

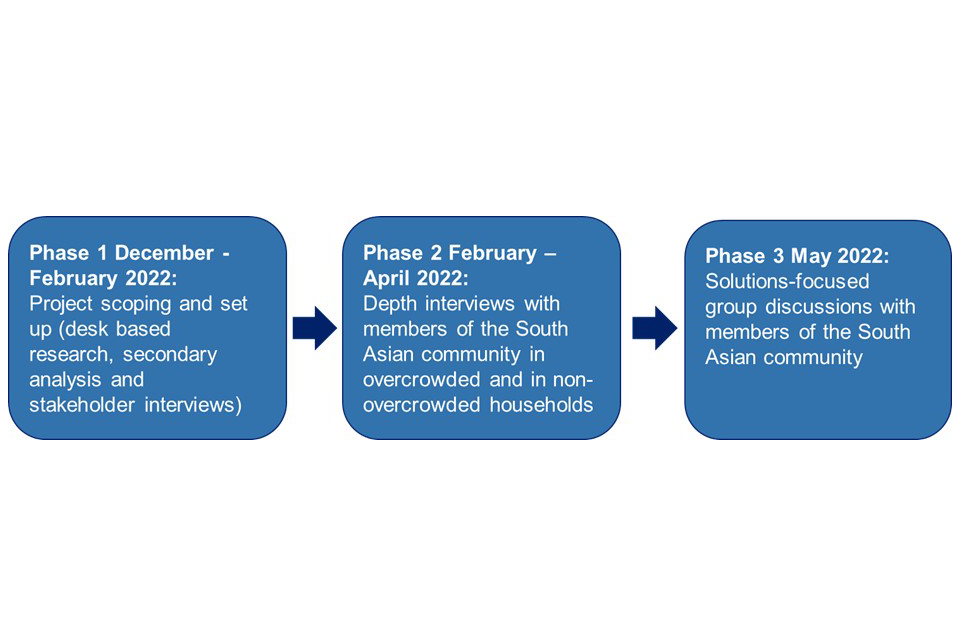

The research design involved 3 key phases:

- Phase 1: Project scoping and set-up (including 12 stakeholder interviews)

- Phase 2: 50 depth interviews with members of the South Asian community

- Phase 3: Six solutions-focused group discussions

1.2 It is important to note that suggestions included in this report are those of the stakeholders who took part in the research and do not reflect DLUHC’s views on policy or potential policy proposals. However, this research and the suggestions within are intended to inform future policy discussions.

Key findings

-

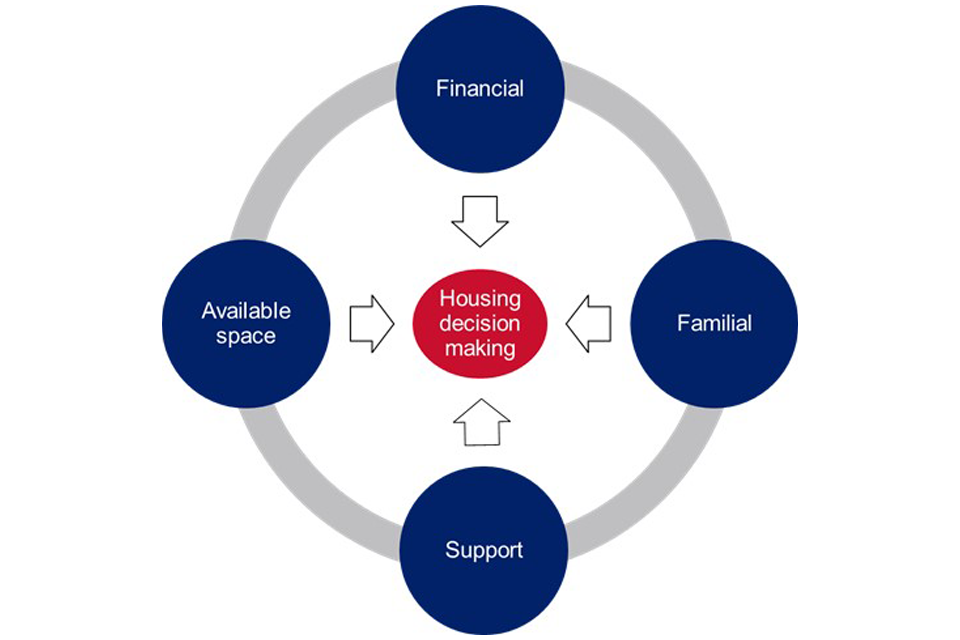

There is a complex interplay of factors that can result in overcrowding, underpinned by people’s wish to live with or close to extended family members and attachment to an area. The critical factors that pushed participants into overcrowded living conditions appear to be systemic. This pertains to the availability of sufficiently suitable and affordable housing.

-

Experiences of overcrowded housing were dynamic and transitory, that is, households could move into or out of ‘overcrowded’ status depending on life events. Participants’ cultural conceptions of family (which include the importance of familial social bonds and non-nuclear family structures) often meant that they required additional space within the home.

-

Housing choices were influenced by a strong attachment to locality. Reasons for this could be practical (access to services), psychological (sense of belonging or nostalgia) or social (proximity to support networks).

-

The Bedroom Standard criteria does not reflect participants’ understanding of ‘overcrowding’. They made comparisons with previous housing, their use of available space, and access to communal rooms to explain their overcrowded circumstances.

-

The desire to change their housing situation involved trade-offs between the space inside the home and the quality and nature of space outside, including the surrounding neighbourhood. Inside space was also balanced against other priorities, such as security of tenure.

-

The benefits of living in larger family units included additional support with childcare and finances. However, to take full advantage of these benefits more space was considered necessary.

-

There were negative consequences to overcrowded accommodation, including an inability to sleep, a lack of privacy, and more family arguments.

Stakeholder suggested interventions

Interventions suggested by stakeholders and those experiencing overcrowding broadly aligned and have been grouped together in this report by theme. Suggestions are broad and not necessarily directed at a particular group or organisation.

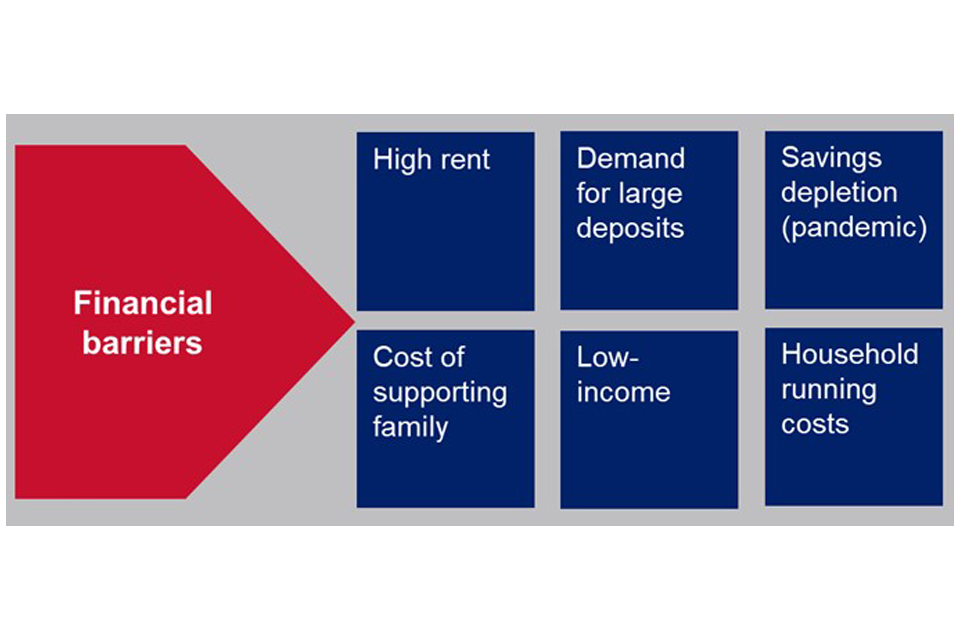

Participants’ solutions in relation to the affordability of housing focused on the following changes:

Financial assistance offered to individuals, including:

- widening the range of government backed homeownership schemes to include more than just first-time buyers

- more rigorous equality impact assessments of financial assistance schemes to address perceptions that these schemes only help those in already strong financial positions

- use of needs-based and flexible eligibility criteria to not inadvertently exclude those who most require assistance

- verification of shari’ah compliant loans to build trust in their authenticity

- further decreasing or removing interest rates on loans and mortgages

- additional support with energy bills and other aspects of the increasing cost of living.

Regulating the housing market, focused on changes to improve access to the private housing market. Specific suggestions included:

- reduce the amount of deposit required for private rentals

- consider regulating rents or capping annual rent increases

- review pricing of ‘affordable’ housing so that it is affordable for those who earn below the national minimum wage

With reference to the availability of suitable housing, suggestions covered 6 areas for investment:

- improving the condition of existing homes in the social and private rented sectors

- expanding existing living spaces through extensions or ‘knock-throughs’

- converting older buildings and disused offices to provide new and larger properties

- encouraging under-occupiers to downsize through combining incentives with ongoing engagement

- changing local planning requirements to reflect local resident demographics

- designing homes in consultation with local residents to better understand their needs.

Participants also offered short term structural actions that, through the enhancement of accessible and adequate support, could help ease the toll on overcrowded households. These included:

- use of multiple channels to communicate information about housing and financial support, including through community networks and local charities

- reestablishment of face-to-face or direct telephone support from housing services

- information on wider benefit entitlements provided at the same time as housing advice

- home visits to assess and fully understand overcrowded conditions

- on-going contact and support during housing application and bidding processes

- reducing variability in the service provided with quality standards applied consistently across local authorities.

Trust in how and by whom information and support is provided alongside the equitable provision of services emerged as key factors in reducing stigma around help-seeking which can form a significant barrier to take up.

2. Introduction

This chapter provides an introduction to the research. It outlines the policy context for commissioning this project as well as the research aims and structure of the report. It explains how overcrowding is currently measured using key definitions and also presents data used to identify groups most likely to experience overcrowding.

The context

2.1 There are 2 standards in Part X of the Housing Act 1985 which are used to assess whether a home is statutorily overcrowded. If a home is overcrowded by either standard, occupants could count as homeless by law and/or receive additional priority for social housing. Local Authorities can also take enforcement action to address overcrowding and/or prosecute those responsible. According to the statutory definition, a house is overcrowded if it contravenes either of the following:

a) The Room Standard: There are so many people in a house that any 2 or more people aged 10 or over and of opposite sexes, have to sleep in the same room, unless living together as husband and wife. For these purposes, children under 10 are disregarded and a room means any room normally used as either a bedroom or a living room. A kitchen can be treated as a living room provided it is big enough to accommodate a bed.[footnote 1]

b) The Space Standard: This standard works by calculating the permitted number of people for a property in one of two ways, with the lower calculated number being the permitted number for the property. One test is based on the number of living rooms in the property (disregarding rooms of less than 50 square feet) and the other test is based on floor areas of each room size.[footnote 2]

2.2 The statutory measurement is not generous and as such there are relatively few households that fall within the threshold. Instead, the ‘Bedroom Standard’, a more generous measurement than the statutory definition is used by government as an indicator of occupation density (EHS, 2020-21a). A standard number of bedrooms is calculated for each household in accordance with its age/sex/marital status composition and the relationship of the members to one another.

2.3 A separate bedroom is allowed for each married or cohabiting couple, any other person aged 21 or over, each pair of adolescents aged 10-20 of the same sex, and each pair of children under 10. Any unpaired person aged 10-20 is notionally paired, if possible, with a child under 10 of the same sex, or, if that is not possible, he or she is counted as requiring a separate bedroom, as is any unpaired child under 10.

2.4 This notional standard number of bedrooms is then compared with the actual number of bedrooms (including bed-sitters) available for the sole use of the household, and differences are tabulated. Bedrooms converted to other uses are not counted as available unless they have been denoted as bedrooms by the respondents; bedrooms not actually in use are counted unless uninhabitable. Households are said to be overcrowded if they have fewer bedrooms available than the notional number needed.

2.5. At the national level, the EHS provides the most recent estimates for the rates of overcrowding in England according to the Bedroom Standard. The overall rate of overcrowding in England between 2018-19 and 2020-21 was 3.1%, with approximately 738,000 households living in overcrowded conditions.[footnote 3] This is a decrease from the 2017-18 to 2019-20 estimate of 3.5% of households (around 829,000) (EHS, 2020-21). Despite this recent decrease, there has been an historic upward trend in the proportion of households in overcrowded living conditions from a low of 2.4% in the period 2001-02 to 2003-04 (around to 486,000 households) (EHS, 2020-21b).

Household tenure

2.6. The data indicates that overcrowding is more prevalent in the rented sectors than for owner occupiers, with social renters more likely to be affected than those in the private rented sector. In the period 2018-19 to 2020-21, 1% of owner occupiers (172,000 households) were overcrowded compared with 8% of social renters (316,000) and 6% of private renters (250,000) (EHS, 2020-21). Rates of overcrowding in the social and private rented sectors had risen to the highest levels seen since data collection began in 1995 (8.7% and 6.7% respectively in the period 2017-18 to 2019-20) (EHS 2020-21b). The higher prevalence of overcrowding within the rented sectors has been attributed to several factors (ONS, 2011a):

- an inability for households to afford to rent homes with more bedrooms

- some renters deciding to remain in smaller homes while they save towards a mortgage

- an unavailability of suitable rental houses especially for larger families, in certain localities.

Regional prevalence

2.7. EHS data indicates the rate of overcrowding is highest in London, where 8% of all households are overcrowded (286,000). This is more than double that of the next highest region – the West Midlands at 3.4%; followed by the South East (3.0%) and North West (2.7%) (Wilson & Barton, 2021).

2.8 Among Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups, the percentage of overcrowding in London rises to 13% with the next highest region being the North West where the proportion affected falls by only 2 percentage points to 11%. This is followed by 10% in the West Midlands (MHCLG, 2020).

2.9. Reasons given for the prevalence of overcrowding in London specifically are higher (ONS, 2014):

- house prices and rents

- proportion of rented households

- population density.

2.10 The 2011 Census is the most recent source of local-level data on overcrowding. The Census collected occupancy ratings for bedrooms using the same measurement as the EHS. ONS (2011a) data shows that 5 local authorities in greater London had the highest incidence of overcrowding:

- Newham (25.2%)

- Brent (17.7%)

- Tower Hamlets (16.4%)

- Haringey (15.9%)

- Waltham Forest (15.4%).

Groups most likely to experience overcrowding

2.11. Previous findings from the EHS, have shown that the highest rates of overcrowding in England are in the Bangladeshi (24%) and Pakistani (18%) ethnic groups, compared to 2% of white British households (period 2015/16 to 2018/19) (MHCLG, 2020). While overcrowding was higher among renters than owner occupiers for both white British and minority ethnic households, there were substantial disparities between the 2 groups. Seventeen percent of social renters from ethnic minorities were overcrowded compared to 6% of white British households of this tenure. A similar pattern was seen with the private rented sector (13% compared to 6% respectively).

2.12 Households with a bedroom deficit are overwhelmingly located in major urban conurbations, with the 2011 Census estimating almost 600,000 of 1.1 million affected homes located in these areas (ONS, 2011b). White British people are the least likely of any ethnic group to live in urban locations in England and Wales (78.2% compared to 97.4% of those of Asian ethnicity, 98.1% of Black ethnicity and 92.1% of other White ethnicity (ONS, 2018).

2.13. Among minority ethnic households, overcrowding is most prevalent in households where the chief income earner holds a routine or manual occupation (14%) or intermediate occupation (12%) (compared to 3% and 2% respectively for white British households). Incidence of overcrowding was highest for those with a weekly income of between £600 and £699 (16% for ethnic minority households compared to 3% of white British households) (MHCLG, 2020). Prevalence declined as income increased above this point. Given the correlation between income and likelihood to experience overcrowding, those from South Asian backgrounds are more vulnerable, with the British Pakistani and Bangladeshi grouping found to have the lowest median hourly pay of any ethnic group in the UK (£1.70 less per hour than the white British group) (ONS, 2021).

Overcrowding and the COVID-19 pandemic

2.14. The research is timely given the disparities highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic. A Public Health England (PHE) review of the impact of COVID-19 on ethnic minority groups identified poor housing conditions and housing composition as contributors to the disproportionate exposure to and infections of COVID-19 within these groups (PHE, 2020). Similarly, the Doreen Lawrence Review linked environmental factors such as overcrowded housing to a higher incidence of COVID-19 related deaths within minority ethnic populations in Britain (Lawrence, 2021). Overcrowding hampered an individual’s ability to self-isolate (a particular risk for multigenerational households), and such households were more exposed to poor air quality and were located in polluted areas, with limited outside space. Analysis carried out by Inside Housing in May 2020 supports this correlation by comparing COVID-19 death rates with levels of overcrowded housing across local authorities in England (Wilson & Barton, 2021). Moreover, overcrowding has previously been linked to specific physical health issues including respiratory conditions and tuberculosis (De Noronha, 2015).

Research aims

2.15. The overarching objective of the research was to provide a more nuanced picture of overcrowding among those from South Asian backgrounds. The research sought to address 4 key questions:

- How do South Asian respondents living in overcrowded accommodation perceive their housing situation?

- What factors lead to overcrowding among those from South Asian backgrounds and influence respondents’ perceptions of it?

- To what extent has the COVID-19 pandemic affected how South Asian respondents feel about living in their current housing situation?

- How might DLUHC tailor policies to address overcrowding in a culturally sensitive way?

Report structure

2.16. The rest of this report covers the following:

- Chapter 3 sets out the research methodology and analytical approach

- Chapter 4 describes the circumstances of overcrowding covering household composition and how it arises

- Chapter 5 presents participants’ perceptions of their housing situation and the strategies used to deal with the consequences of living in overcrowded accommodation.

- Chapter 6 discusses participants views on the barriers to changing their living situation and finding suitably sized accommodation.

- Chapter 7 concludes by discussing the interrelated housing issues related to overcrowding and sets out suggestions for policy makers and housing providers.

When verbatim quotes are included, these are labelled using the following codes:

Table 2.1: Verbatim quote label codes

| Sampling criteria | Code |

|---|---|

| Ethnic Group: Pakistani | P |

| Ethnic Group: Bangladeshi | B |

| Gender: Male | M |

| Gender: Female | F |

| Housing tenure: Private renter | H1 |

| Housing tenure: Social renter | H2 |

| Housing tenure: Owner occupier | H3 |

| Region: London | R1 |

| Region: West Midlands | R2 |

| Region: North West | R3 |

| Region: Yorkshire & the Humber | R4 |

3. Methodology and analytical approach

3.1 The study consisted of 3 phases as set out in Figure 3.1 and described in this section. This report captures findings from all 3 phases.

Figure 3.1: Research phases

Flowchart illustrating the three research phases of the project spanning from the scoping stage in December 2021 to the depth interviews in Spring 2022 and focus groups in May 2022.

Phase 1: Scoping

Desk based research

3.2 To contextualise the research, we conducted desk research. It involved a review of research publications and policy papers relevant to overcrowding and the impact of COVID-19 on overcrowded South Asian households. Secondary analysis examined data on overcrowding in South Asian households from the 2011 Census (ONS, 2011) and the English Housing Survey (EHS, 2020-21).

Stakeholder interviews

3.3 Depth interviews with local authority housing staff, Registered Social Landlords, and representatives from homelessness/housing charities were used to gather information on local housing issues in areas where those from South Asian backgrounds experience a high incidence of overcrowding. The interviews were conducted online and covered the following themes:

- housing supply issues that cause or contribute to overcrowding

- perceptions of overcrowding among those from South Asian backgrounds and changes observed in recent year

- suggestions for addressing overcrowding

Phase 2: Depth interviews

3.4 Depth interviews with British Bangladeshis and Pakistanis focused on selected areas (see Sampling section below). In addition to capturing the experiences of those living in overcrowded households, for comparison, a small number of interviews were also conducted with people from South Asian backgrounds who were not living in overcrowded homes. Participants were given the option to complete the interview online, by telephone or in-person.[footnote 4] The interviews with those in overcrowded accommodation covered the following themes:

- perceptions of their living situation

- how the COVID-19 pandemic affected these perceptions

- ideas about what household changes are needed

- support needs to help change their living conditions.

The thematic coverage of interviews with the non-overcrowded sample was similar but with a focus on:

- previous experiences of overcrowded accommodation

- how they came to live in non-overcrowded accommodation

- views on overcrowding as a community issue.

Phase 3: Solutions-focused group discussions

3.5 Phase 3 comprised 6 group discussions with British Bangladeshis and Pakistanis, including a number of participants reconvened from the depth interview stage alongside new participants. Five of the groups were conducted online, with one conducted face-to-face to include participants who did not have access to or feel comfortable with online participation. Five of the groups took place in English while the sixth was conducted in Sylheti. The groups were aimed at generating ideas for how DLUHC could tailor policies to address overcrowding.

3.6 Discussions were designed to first elicit spontaneous suggestions from participants in response to a vignette portraying a household living in overcrowded circumstances. Group participants were then presented with 2 potential policy responses to overcrowding (see Appendix B for details). The first considered provision of shari’ah compliant interest-free loans to help with upsizing or moving and the second proposed a dedicated information and advice service for people living in overcrowded accommodation. Participants were asked their views on various aspects of the responses including:

- perceived helpfulness

- likelihood to use

- how and by whom it should be delivered

- suggested changes or improvements to the intervention.

Recruitment and informed consent

Stakeholders

3.7 In the first instance, invitations to participate in the research were sent by DLUHC to Local Authority and Housing Associations contacts. Stakeholders then had to ‘opt in’ to be interviewed by responding either to DLUHC or directly to NatCen. Three stakeholder interviews were recruited in this way. The remaining 8 stakeholders were recruited either through LinkedIn, publicly available or existing NatCen contacts.

2.8 Invitations to participate included an explanation of the research and how stakeholder data would be used by NatCen. Permission to record was sought prior to the start of the interview.

Community members

3.9 A blended recruitment approach was undertaken using Criteria Qualitative Fieldwork, a specialist recruitment agency, and, to supplement this, via NatCen’s probability-based Panel sample. Criteria used 3 approaches: 1) recruitment from their existing database of participants, 2) through local community organisations and networks and 3) using a snowballing technique. Agroni Research, a specialist multi-disciplinary research organisation, supplemented recruitment for the Phase 3 group discussions using similar techniques.

3.10 A screening questionnaire was developed by NatCen and used during recruitment to ensure participants met the inclusion criteria. To identify people living in overcrowded housing, potential participants were screened using the Bedroom Standard definition (used in the EHS 2020-21). Consent to participation and recording of interviews was sought.

Ethics

3.11 Ethical approval was sought from NatCen’s Research Ethics Committee (REC). This ethics governance procedure is in line with the requirements of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC, 2005) and Government Social Research Unit Research Ethics Frameworks (GSRU, 2005).

Sampling

Stakeholders

3.12 Eight interviews were carried out with stakeholders as part of Phase 1. A further 3 interviews took place following the conclusion of the Phase 2 fieldwork to add additional insights to the community depth interview findings. Table 3.1 provides a breakdown of the achieved stakeholder sample:

Table 3.1: Achieved sample – stakeholders

| Organisation type | Achieved sample |

|---|---|

| Local Authority | 3 |

| Housing Association | 6 |

| Housing/ Homelessness charity | 2 |

Phase 2 depth interviews

Selecting areas

3.13 Participants were recruited across a wide geographical area but focused on local authorities with a higher incidence of overcrowding among those from South Asian backgrounds in England. The Phase 1 desk research identified that overcrowding is most prevalent among minority ethnic households in London, the West Midlands and North West. These regions were the focus of the research and quotas were set to ensure a range of circumstances and experiences were captured during fieldwork.

3.14 In the final sample a large proportion of participants resided in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, Birmingham and Oldham, which is broadly in line with the distribution of overcrowded minority ethnic households described above. Each of these areas has a large South Asian population alongside a high prevalence of overcrowding. Of the usual resident population in Tower Hamlets, 1.0% is of Pakistani and 32.0% of Bangladeshi ethnicity. The figures are 13.5% and 3.0% respectively for Birmingham and 10.1% and 7.3% for Oldham (ONS, 2011). Each of these areas ranks among the most deprived 20% of local authorities in the Multiple Deprivation Index and has lengthy Local Authority waiting lists for social housing (21,152 in Tower Hamlets, 5,931 in Oldham, 17, 307 in Birmingham) (DLUHC, 2022).

Participant sample composition

3.15 In total, 50 depth interviews were carried out. The sample included 38 people who live in overcrowded housing and 12 who do not. Two interviews were conducted in 5 of the overcrowded households in order to contrast different gender and generational perspectives of the same housing situation. To ensure that a diversity of views was captured within the sample, a screener was administered, and quotas were set against key sampling criteria and monitored throughout. (For details see Appendix A).

Phase 3 group discussions

3.16 This stage focused on those living in overcrowded accommodation with a total of 48 participants recruited. Sample design ensured a diversity of views was captured, with groups stratified by age, gender and ethnicity to ensure participants felt comfortable to speak freely. Two groups were composed of participants from London only to explore housing issues specific to the capital. (For details of the achieved sample see Appendix A).

Analytical approach

3.17 Detailed notes were written up after each stakeholder interview using a template designed around the topic guide. All Phase 2 interviews conducted in English were professionally transcribed and thematically categorised using Framework in NVivo. For a small number of interviews conducted in other languages, detailed notes were written up by the interviewer and added to Framework. For the Phase 3 group discussions, detailed notes written up by facilitators were again categorised using Framework. All Phase 3 group discussions conducted in English were also professionally transcribed.

3.18 The Framework approach, developed by NatCen, offers a systematic and robust way to organise and analyse qualitative evidence. A series of matrices were set up, with each column representing a sub-theme and each row representing an individual case. Transcribed data was thematically summarised and illustrative verbatim quotes added to the Framework matrix. Analysis was conducted using the themes covered in the interview topic guide. Emerging themes were incorporated into the matrix and linked back to the transcripts for transparency and quality assurance checks.

Limitations

3.19 The key limitations are set out below and refer to sampling and coverage:

-

Achieved sample: Due to COVID-19 health restrictions, it was not possible for face-to-face recruitment to take place and recruitment through community organisations was limited by telephone and email communication. While care was taken to ensure that a range of views were captured, these restrictions made it more difficult to ensure participation from all demographic groups. As a result, the study was unable to capture the views of those aged 70 and over in overcrowded accommodation.

-

Coverage: Phase 2 of the study only focused on 3 geographical regions in England. While these areas were selected for high incidence of overcrowding within minority ethnic households, it may be that other views and experiences exist elsewhere in the country that this study has been unable to capture.

4. Experiences of overcrowding

4.1 This chapter describes the different circumstances in which overcrowding within British Bangladeshi and Pakistani households occurs and presents perceptions of why this happens. It also incorporates the views of stakeholders around causes of overcrowding among those from South Asian backgrounds.

Circumstances leading to overcrowding

4.2 A range of circumstances were identified that led to living in overcrowded conditions. This section examines how this varies by different types of households.

Types of overcrowded households

4.3 The study found that the types of households experiencing overcrowded circumstances in this research fell into 4 main categories, which are depicted in Figure 4.1 and explained below.

Figure 4.1: Types of overcrowded households

Four types of overcrowded households are described in four different coloured boxes: Young families, Older families, Non-nuclear households and Small families.

Young families

4.4 These were households with a large number (5+) of younger children, that is, aged under 10 and/or pre/young teenagers. They tended to be in private or social rented housing and were living on a low income. Those who had recently settled in England were more likely to be in this grouping and to be experiencing the highest levels of overcrowding within the sample. This was due to unfamiliarity with the social housing system which put them at a disadvantage when seeking support from housing services. These participants had also had less time to build up personal resources to provide a buffer against difficult housing market conditions.

Older families

4.5 Across all tenure types, these households included children in their later teens and/or unmarried adult children. This household type did not necessarily have as many people living together as the previous grouping but were nevertheless overcrowded given the additional space requirements for older teenagers and young adults.

Non-nuclear households

4.6 Non-nuclear households included multigenerational and extended families as well as houses of multiple occupancy (HMOs.) The day-to-day experience of overcrowded living depended on whether those living in the household were related or unrelated. In the latter case, the negative personal and interpersonal consequences of overcrowding were felt more acutely, while in the former, practical, social and emotional benefits offset some of the stresses associated with a lack of space.

Small families

4.7 There were also families who were small in size (that is 1 or 2 children), but nevertheless overcrowded as they lived in one-bedroom properties. These households were more likely to be located in London where a lack of bedrooms was exacerbated by a general lack of space elsewhere in the property. This was both in terms of indoor communal rooms and outdoor spaces, such as patios or gardens.

Causes of overcrowding

4.8 Individuals’ experiences of overcrowded housing were dynamic and transitory, that is, households could move into or out of ‘overcrowded’ status depending on life events. However, the intersection between attachment to particular geographical areas and local housing issues was a more permanent limitation on housing choice. There were no perceived differences according to ethnicity within the sample. Instead, causes of overcrowding varied according to the life stage of household members, whether participants lived in or outside the capital, and whether a participant was a first-generation immigrant or British-born.

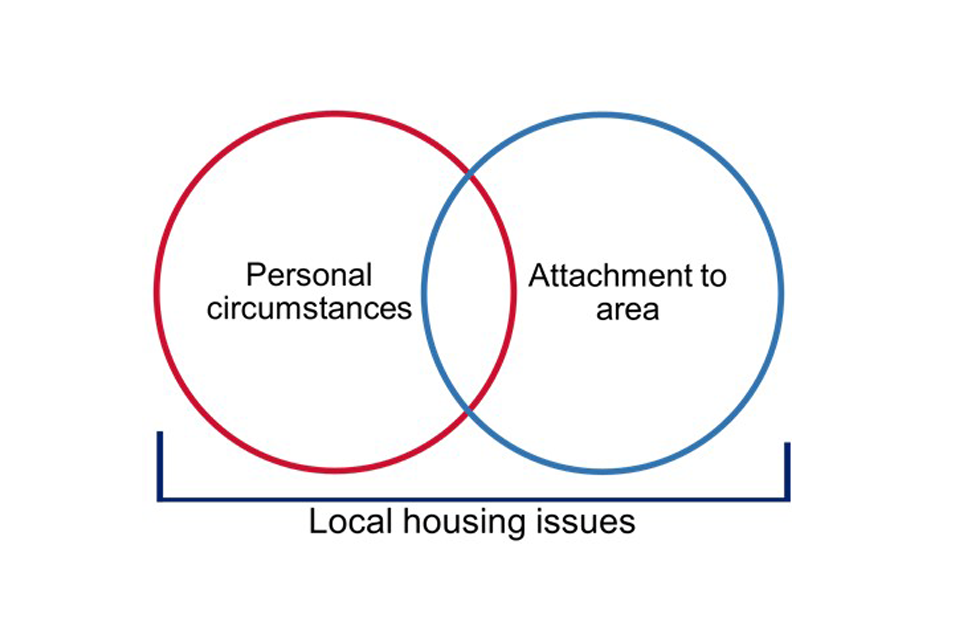

4.9 As such, the reasons why people were living in overcrowded accommodation fell into 2 broad categories as shown in Figure 4.2: personal circumstances, and attachment to area. Overcrowding arose when these factors coincided with local housing issues which were structural in nature. These included:

- an insufficient supply of suitable and affordable properties

- a lack of family-sized homes with 3 or more bedrooms

- a lack of social housing which resulted in lengthy waiting lists.

These structural barriers are discussed in detail in Chapter 6.

Figure 4.2: Causes of overcrowding

A venn diagram showing the interlinked issues of personal circumstances, attachment to area and local housing issues as key causes of overcrowding.

Personal circumstances

4.10 There was a range of ways in which personal experiences, preferences or circumstances determined whether or not a household was overcrowded.

Life transitions

4.11 Participants described life transitions, ranging from the birth of children to ageing that had resulted in their overcrowded housing situation.

4.12 Marriage: in more culturally traditional families, women upon marriage ended up in overcrowded situations when they moved into their partner’s family home. In other cases, marriage led to a reduction in overcrowding, when newlyweds moved out of a property and freed up space. However, the decision to leave could result in tension among family members.

‘I was like, ‘I’m not staying here anymore,’ …I think my in-laws, they were a bit annoyed with me, but I didn’t care because it was for my own sanity.’ R2, F, 30 - 49, P, H2

4.13 Family out growing property: Participants described how a property had been appropriately sized when they first moved in but had become too small as they had more children in subsequent years. For these participants, there was a ‘tipping point’ when the property no longer met their needs.

‘Initially we moved here, I think it’s been 15, 16 years ago, yes, when I had my elder two, and then obviously with the two, it was fine, because we’ve got the shops close by and everything suited us. Then obviously over the years I’ve had the other children.’ R2, F, 30 - 49, P, H1

4.14 Adult children: The space needs changed as children grew up and older teenagers and adult children required their own bedrooms. The reasons for this were both emotional, such as a greater need for privacy or ‘own space’, and practical, including needing a space for study or possessions. This need arose from middle teenage years onwards and participants felt that this was not adequately captured by the Bedroom Standard threshold of 21.

‘Yes, now we’re older, we’ve got more clothes, we’ve got to work. It wasn’t really an issue before, but after the age of 18, 19, you need your own room. You need your own space, stuff like that, privacy.’ R1, M, Under 30, P, H2

4.15 In instances where moving into a larger property did not seem like a viable option, participants talked about ‘waiting it out’ for children to grow up and leave home to have more space. However, this could be delayed as young adults struggled to move out of the family home due to affordability or availability of properties.

4.16 Care needs: where family obligations required it, older parents moving into the home due to ill health and increasing care needs also led to overcrowding. This could also be exacerbated by additional needs for space created by particular care requirements, such as medical or assistive equipment.

‘I don’t want to send my parents to a care home. Once they get to that age, I want to keep them with me as long as I can. I’ve always been that way; especially my family have always been that way, and in the community, I guess it’s similar.’ R1, M, 30 - 49, B, H3

Family ties

4.17 Cultural conceptions of family, including the importance placed on the role of the extended family among those from South Asian backgrounds as well as a tendency for families to have more children than the white British population were given as reasons for overcrowding. Activities connected to this, such as family gatherings or visits, also created particular space requirements.

‘South Asian communities like to build families. We like to have more siblings and have that united feeling of being connected to each other […] We don’t like to be alone.’ R1, F, 30 - 49, B, H2

4.18 Moving out was seen to risk breaking valued social ties to family members and a wider social network. Participants described wanting to contribute to or ‘give back’ to the family. In this sense, there was a strong awareness of both practical and emotional benefits of maintaining close family relationships within the same household.

4.19 However, participants also noted that cultural preferences for living in households with grandparents or extended family members were changing, with younger family members more inclined to move into their own accommodation after marriage. Remaining in the family home was becoming a more temporary arrangement to facilitate saving for a deposit or waiting on a housing allocation.

Attachment to area

4.20 There were both personal and structural reasons why participants wanted to live in a particular area, and which contributed to them entering into or remaining in overcrowded housing. It should be noted that there were also participants who did not like the area they were living in but could not move out due to financial or other reasons.

Practical reasons

4.21 It was important to participants that amenities including shops and schools were close by. This, in their view, made it safer for children to travel to these locations by themselves and alleviated their own fears. In addition, being able to walk rather than take public transport reduced travel costs.

‘Everything’s quite local and we’ve got everything around that’s not far out of place for the kids, and I don’t need to stress or worry thinking I need them to go certain places on a bus. The older ones obviously, they’re fine, they can go on a bus, but the shops, everything I need is just at hand.’ R2, F, 30 - 49, P, H1

4.22 Living in areas with a large South Asian community also ensured easy access to culturally appropriate services such as halal food shops, mosques, and faith schools. This was particularly important for those who had moved to the UK more recently.

Psychological reasons

4.23 Participants who felt a sense of belonging to the area remained there or returned to it because they felt safe and welcomed. This identification with an area meant that participants were more willing to live in overcrowded households. Returning to or remaining in an area was linked to perceptions of other areas as being unwelcoming due to socio-economic or class differences (for example, other areas were described as ‘posh’).

‘You do feel sometimes if people don’t have larger families in those kind of areas, you’re thinking would they look down on you, or you’re not going to fit in. It’s just things like that.’ R2, F, 30 - 49, P, H1

4.24 Another reason for returning to a more familiar area was experiences of implicit or explicit racism.

‘Sometimes it can be a bit scary moving to a non-Asian area. You’re scared of racism, what are people like, are they going to throw bricks at your house? At least here we know we’re safe. People here aren’t going to discriminate because you’re brown or anything.’ R3, M, under 30, B, H2

4.25 Participants linked their sense of belonging to a greater understanding or tolerance of cultural practices in areas with a large South Asian community. Examples of this included having many visitors over for holidays and celebrations.

‘So for example, I don’t know, they kind of understand, say if you’ve got a lot of visitors over, like holidays and weddings and all that kind of stuff.’ R3, M, under 30, B, H3

4.26 Nostalgia for and memories of the area that they grew up or raised a family in led to a strong attachment to the area. This extended to wanting children or grandchildren to remain in the area and to be part of their shared history. These intangible connections to place outweighed concerns around negative changes to the area, such as rising crime rates or an area becoming run down. Younger family members were more likely to show less emotional or psychological ties to the area and to aspire to move away from an area that was no longer meeting their housing needs.

‘I would have moved out a long time ago, to be honest, because our neighbourhood where we live, over the past I would say about 15 to 20 years, slowly, slowly, everyone has started moving out of the area, so it’s like it wasn’t the same no more.’ R2, M, 30 - 49, P, H1

4.27 For first generation immigrants, the area may be the first they lived in after emigrating and therefore felt attached to it. At the same time, participants who had been born in the UK may not have had experiences of living elsewhere either, and therefore had a fear of the ‘unknown’ in other areas.

‘I don’t want to leave, it is like the first love, so I don’t want to leave this area.’ R1, M, 50+, P, H1

Social reasons

4.28 For less established immigrants, it was particularly important to be in an area with an established South Asian community, including having people who spoke the same language around.

‘Like my husband, he’s from back home, and then you’ve got a lot of the Asian community around you, so if you want to go to your local shops, and if your English isn’t as good, you’ve always got people that can help you and understand you.’ R2, F, 30 - 49, P, H1

4.29 For British-born participants, there was a generational distinction between younger family members who felt less drawn to place and instead were guided by where their housing needs would be better met. This was in contrast to those who had their own young families and wished to bring them up in the area they themselves had been born. However, the former deprioritised their own housing preferences to ensure older relatives were able to stay in communities they felt comfortable in. For example, younger participants described remaining in a property where they lacked privacy because a parent or grandparent did not want to leave a desired area, despite options being available elsewhere.

4.30 For British-born participants with children, the decision to remain was tied to wanting their children to have familiarity with the community’s cultural practices as they grew up and to continue a sense of belonging and identity to the community.

‘We’re still living in the community that I grew up in, and it’s important that my identity remains. I’m Bangladeshi. I want my children to have a strong identity to the Bangladeshi community and still being part of it and visibly seeing people that are Bangladeshi is important.’ R1, F, 30 - 49, B, H2

4.31 Other participants felt attached to the area they lived in because it was diverse and multicultural. For these individuals, it was important for their children to learn about other cultures and belief systems. Other considerations related to bringing up children were also raised, such as the importance of having parks and green spaces nearby.

4.32 Participants also described wanting to be close to family so they could have help with childcare and to ensure that their children had relationships with cousins and other members of the extended family. Being close to family networks was viewed as important for preventing loneliness for adult family members and for maintaining good mental health.

Summary

4.33 There were 4 main types of households which experienced overcrowded living: families with a larger number of young children, families with late teenage or adult children, non-nuclear households including multigenerational households and HMOs, and small families who were nevertheless overcrowded due to property size.

4.34 Individuals’ experiences of overcrowded housing were dynamic and transitory, that is, households could move into or out of ‘overcrowded’ status depending on life events. The specific life stages of household members influenced whether they had already or were yet to experience a transition that would lead them into overcrowding. Cultural conceptions of family created additional space requirements within the home while strong familial ties meant that participants remained together rather than finding separate accommodation.

4.35 Participants also desired to live in specific areas. Reasons for this could be practical, psychological or social and varied depending on whether a participant was a first-generation immigrant or British-born. While reasons specific to personal circumstances and a desire to live in a particular area dictated a family’s housing needs, it is when these factors interacted with structural issues such as lack of appropriate and affordable housing supply that overcrowding arose.

5. Consequences of overcrowding

5.1 This chapter explores participants’ perceptions of their living situation and how it has affected them. It includes reflections on how views of family and the trade-offs between indoor and outdoor spaces factor into views on home and housing experience. The extent of and how the pandemic has affected views on housing will also be examined.

5.2 The chapter also describes how households deal with overcrowded living and the individual and interpersonal consequences that result from it.

Perceptions of ‘overcrowded’ living situations

5.3 Participants’ perceptions of their living situation were not straightforward. They could both recognise a need for more space / improved housing and enjoyed aspects of or had an emotional connection to their home.

5.4 At one end of the spectrum were those who spoke frankly about needing more space within the household, and the effects of overcrowding on household members. This group were actively seeking to change their housing situation. At the other end were participants who did not recognise their home as being overcrowded and did not see a need for change despite their home being considered overcrowded using the Bedroom Standard definition.

5.5 However, there was little understanding of how ‘overcrowding’ was viewed by others in the community as it was not spoken about. Participants believed that others either were content with things as they were – ‘it’s always been this way’, found a way to cope as there was no solution to the issue - ‘just got on with it’ – or did not complain due to concern around upsetting or causing offence to family members.

‘Obviously, not everybody talks about it, that they’re overcrowded in their families… I think people, just generally, have an idea that they are overcrowded, but they’re managing, aren’t they. You just have to put a smile on and carry on with life, don’t you.’ R3, M, 30 - 49, P, H1

Defining ‘overcrowded’

5.6 One perspective amongst those who wanted to change their housing situation was that ‘overcrowded’ was an accurate description of their circumstances. However, the term was felt to lack nuance in relation to the different ‘levels’ of overcrowding experienced, that is, 4 sharing a room is very different from 2 sharing a room. A different view was that the term was too ‘extreme’. These participants offered alternative language such as ‘cramped’, ‘cosy’ or ‘tight’ to describe their situation.

5.7 Those who thought the term had connotations of dire poverty and deprivation, felt that it did not accurately explain their reality in today’s housing market in which ‘it can happen to anyone.’

‘When you hear ‘overcrowded’, the connotations it has, that it’s associated with low-income families, very dire situations, very poor, disarray in a terrible housing block. It conjures those types of stereotypes and I think for me, it doesn’t, that doesn’t apply any more.’ R1, F, 30 - 49, B, H2

5.8 One view was that the term appeared to place blame on the families experiencing overcrowding ‘for having too many children’ rather than recognising conditions within the housing market which created such situations.

‘I don’t think it’s a nice term ‘overcrowded.’ Normally people talk about immigrant communities being overcrowded, “This country is overcrowded. Immigrants come in and they live in small houses and they just have loads of kids,” as if it’s their fault or something. So it has a stigma attached to it.’ R3, M, under 30, B, H2

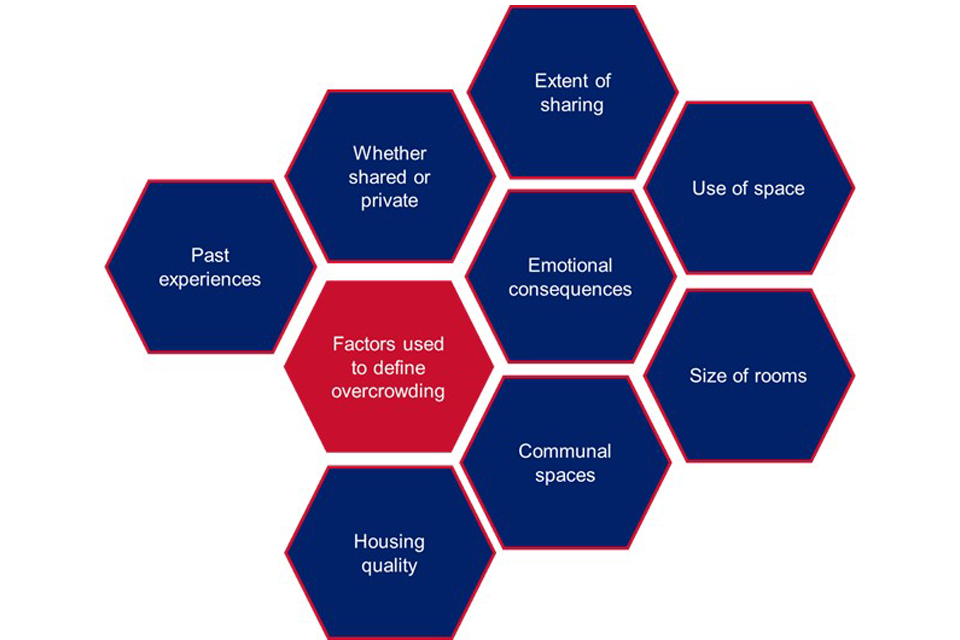

5.9 Whether or not participants related to or used the term ‘overcrowded’ to describe their living situation, as well as the extent to which they desired to change their accommodation, depended on a range of factors as depicted in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1: Factors used to define overcrowding

A honeycomb shape image of interlocking hexagons illustrating the various ways in which participants described and compared their experiences of overcrowding.

Comparison to past experience

5.10 Participants’ past experiences of housing were a frame of reference when deciding whether a housing situation is ‘overcrowded.’ They may have previously lived in a more spacious parental home with adequate bedrooms, or instead, have moved from a property where more people were sharing fewer rooms.

5.11 Differences in experience between household members also led to differences in perceptions of the same living space. For example, a female participant had grown up as an only child and always had her own room, whereas her husband was part of a large family. As a result, he had a different view on the amount of space needed in the home. In another instance, a young adult male explained that his current living situation was ‘all he had known’ and therefore felt unable to comment on whether the space available in his home was typical or not. However, his mother was adamant about the need for more space and its impact on her quality of life, having lived in less crowded conditions previously.

Extent of undesirable sharing

5.12 There was a range of ‘levels’ of undesirable sharing represented among the people who took part in the study. Particular dissatisfaction was expressed by those with a greater bedroom deficit or where the differing needs of those sharing made the situation more difficult. For example, where parents and children had opposing sleeping patterns which affected day-to-day activities. For more traditional households, there was a cultural and religious preference for males and females to have separate rooms. If this was not possible, it contributed to negative housing perceptions.

‘Very concerning, because personally, I would just love for my kids to be, the boys and the girl to be separated. That bothers me a lot. That is stressful. It’s very stressful, to be honest, my house, and being like this, in this state.’ R1, F, 30 – 49, B, H1

Use of space

5.13 Participants explained how they used their current space, and whether it adequately met their needs for dining, socialising, and working from home. The use of space for specific purposes was not static and could change as the needs of the family changed, for example, as children grew up and needed space to study or work; or as parents aged and required more care.

5.14 Where different generations had competing needs or uses for the space, this also negatively influenced perceptions.

‘Then you want to do different things. They want to, like I said, they want to have this aunt and that uncle around all the time, and I’m like, woah, yes, but I want to go out, or I want my friends to come round. It’s like chalk and cheese, that’s never going to happening. There’s grating.’ R1, F, 30 - 49, P, H2

5.15 Female participants tended to be more vocal about the need for more space in their households. There were gender differences in the use of space, with female participants spending more time within the home and having more responsibility for caring duties and household tasks.

Size of rooms

5.16 Participants referred to the size of bedrooms and not only the number. It was felt that bedrooms should be a sufficient size to allow for basic furniture and the storage of possessions and should not be physically difficult to move around in.

‘We can’t even put furniture in the bedroom just to keep your necessities in the bedroom.’ R2, F, 50+, B, H2

5.17 Individual interpretations meant that small rooms were not considered bedrooms.

‘I would say you need to check the size of the bedrooms, because like I say, my sister has her own room, but that room is not really a bedroom. I wouldn’t count it as a bedroom. It’s small.’ R2, M, under 30, P, H1

Communal spaces

5.18 In addition to the size and number of bedrooms, participants also considered access to suitable communal spaces including living rooms, kitchens, dining rooms, bathrooms and gardens, in their definition of overcrowding. Overcrowding occurred when these communal spaces were described as insufficient in size or number for the amount of people living in the household. For example, participants described having to share one bathroom between a large number of family members or not having space in the kitchen for necessary appliances such as fridges, freezers and washing machines. Female participants placed particular emphasis on a need for larger communal spaces, which could be due, in part, to gender differences in the use of space discussed earlier in this section. On the other hand, where more communal spaces were available to a household, converting extra space into a bedroom eased some of the pressures caused by limited sleeping spaces.

Housing quality

5.19 Participants noted problems with available housing, mainly in the private rental sector, such as damp, leaks, poor insulation, inefficient heating systems, pest infestations, and general disrepair. These issues of poor quality or rundown homes existed alongside a lack of space and added to negative perceptions of the housing sector, more generally. Maintenance issues had multiple consequences, including affecting sleep quality and academic performance.

Whether a space is hared or private

5.20 For those in houses of multiple occupancy, having to share spaces with others who were unrelated to them was a key aspect of their experience of living in ‘overcrowded’ accommodation.

Emotional or psychological consequences

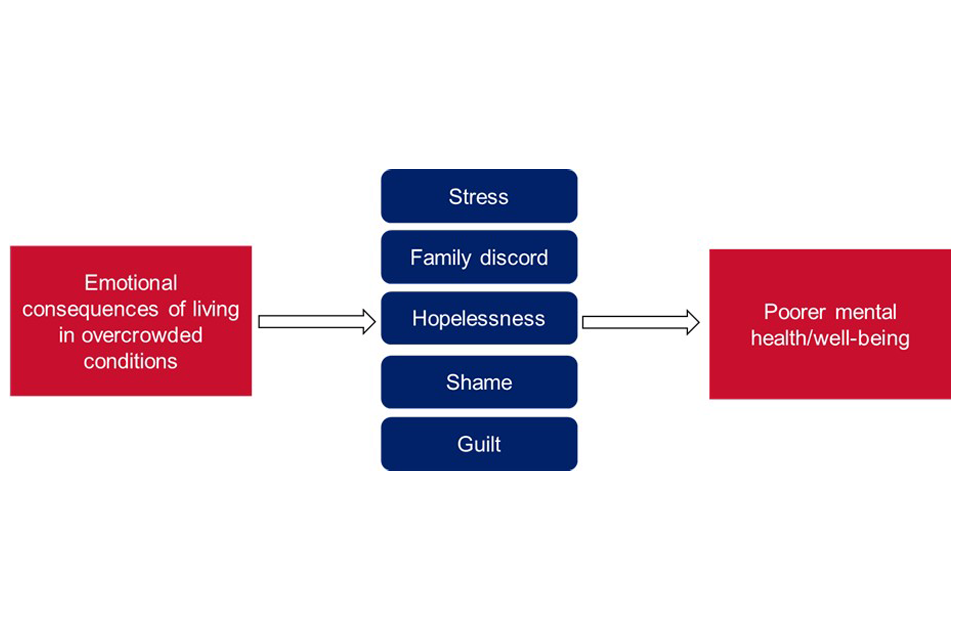

5.21 Other participants defined ‘overcrowding’ with reference to the negative feelings that household members experienced, from frustration through to more serious mental health consequences. As depicted in Figure 5.2, these negative feelings had developed due to a combination of factors, including, stress caused by the practical challenges of living in overcrowded circumstances, increased family discord as a consequence, guilt about being unable to provide children with adequate space, shame about being overcrowded and hopelessness at being unable to change their circumstances.

Figure 5.2: Negative feelings and emotional consequences

Flowchart showing how negative emotional consequences of overcrowding can lead to poorer mental health.

5.22 The cumulative and persistent nature of these factors led to reduced wellbeing for participants.

‘I feel that strain within my mental health and physical health. It’s impacted me so much. I actually cry sometimes. I do get very emotional…It affects me every single day. My enjoyment of life is severely affected because of this flat.’ R1, F, 30 – 49, B, H2

Trade-offs

5.23 Households described other priorities which competed with the need for more space and influenced the extent to which participants sought change to their circumstances. For these participants, having more space was framed as an ‘ideal’ but not a necessity.

5.24 For those in privately rented or owned homes, the ability to afford the rent or mortgage and to meet other costs involved in running a household was prioritised over space. It was acknowledged that a larger home would entail spending more, not only on rent or mortgage repayments, but other bills such as gas and Council Tax. This group also included those who chose smaller, more affordable housing in order to afford to visit family abroad or to save.

5.25 Social housing tenants prioritised the security of tenure over exploring possible private rental options. Others said feeling safe was the most important factor in their housing choice. This was relevant both in terms of feeling safe in the area but also in relation to the characteristics of the property itself.

Beyond the home

5.26 Conceptions of home also extended beyond the household itself into the wider area or neighbourhood. In this way, it may be inadequate to think about overcrowding only in reference to the individual family home. Participants had strong ties to shared community spaces such as mosques and schools as well as the households of other family members living nearby. Participants spoke about having to make trade-offs between the space inside the home and the space beyond it. It could be a fraught decision for individuals considering moving out of the area.

‘We’re battling with ourselves about what to do. If we move out of London we could probably rent something a bit less than this and we would choose where we live… But because we’ve lived in this area, this community, the children are settled and I have all my family around me. It’s such a big decision to make.’ R1, F, 30 - 49, B, H2

5.27 Regardless of definition, participants questioned the relevance / usefulness of the term ‘overcrowded’, suggesting that the government’s use of, or interest in the term did not seem to make any practical difference to their circumstances.

‘My feelings are, if the government have acknowledged that that is the situation, then why are they not doing more about making bigger houses or being able to house people who need the space? The adequate space that they talk about, why is it so difficult for them to be able to provide that?’ R3, F, 30 – 49, B, H2

How COVID-19 affected perceptions

5.28 Policies and restrictions put in place to mitigate the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic had a range of consequences for overcrowded households. Participants tended to fall into 3 main groups when describing how the pandemic had affected their views of their living situation:

-

Change became more urgent: For those who were already informed and engaged and wanted to change or improve their living situation before COVID-19, the pandemic made this feel more urgent. This group described both practical and psychological ways in which they had been affected across 3 aspects of their lives: as depicted in Figure 5.3.

-

Space became a priority for the first time: Others who had not seen the lack of space as a priority prior to the pandemic were, for the first-time, seeking to change their living conditions following the added strain that the pandemic had placed on their household.

‘It’s just made us think twice this time, if it does ever happen again, at least then you know what? We’ve got a nice garden; we’ve got a nice drive. The kids are safe, the kids are not overcrowded. We can do everything just as a family. It’ll be good for our mental health, physically and mentally.’ R2, F, 50+, P, H3

- Attachment to current home increased: In contrast, there was another group for whom the pandemic had led to a greater attachment to their current home. For this group, their home and the relationships between the various household members had been an important source of safety and support during the pandemic.

Figure 5.3: Consequences of COVID-19 policies

A circular diagram showing the cyclic nature of how participants managed pandemic related restrictions.

5.29 How participants managed pandemic related restrictions depended on their household composition. There was heightened concern because participants were aware of high rates of COVID-19 infection and illness among British Bangladeshis and Pakistanis.

‘Being fearful, isn’t it, because a lot of people passed away and there were a lot of people in the Bangladeshi community that passed away, so knowing that we’re… We were at greater risk of maybe having a higher level of infection…’ R1, F, 30 – 49, B, H2

5.30 Those living with relatives who were elderly and/or had underlying health conditions had been especially worried about the risk of infection. They described taking a stringent approach to hygiene measures to prevent COVID-19 infection. This could include taking additional precautions such as younger household members temporarily giving up employment outside the home and living off their savings. Fear of becoming ill was also particularly high for those in houses of multiple occupancy because they found it more difficult to have a coordinated approach to managing risk.

5.31 When one or more household members did contract the virus, shielding or self-isolating was difficult or impossible in large households due to the lack of space within the home. The whole household was therefore exposed to a higher risk of infection.

‘The joke was well where was he going to self-isolate? How the heck are we going to self-isolate in this place?’ R1, F, 30 – 49, B, H3

5.32 For those without access to online delivery services or support networks, a family member with a negative test result and no symptoms (even though they had been in contact with an infected person) had no choice but to leave the house to buy food and other household supplies.

5.33 A reduction in income or the loss of employment meant that financially, households were more at risk in relation to keeping up with rent payments to private landlords. Where landlords were more sympathetic, the loss of income still had implications for household budgeting. Aspirations to change their household circumstances and potentially move out of overcrowded housing seemed more distant, if not impossible, as households used up their savings and went into arrears.

5.34 Those with children felt that there was a lack of support in relation to home learning, with adults working at home while helping their children with their schooling. This placed additional pressure on families with limited space and was compounded in households with poor Wi-Fi connectivity. Increasing bandwidth and connectivity entailed an additional expense for those on limited budgets or experiencing job losses.

5.35 The shrinking of outdoor and indoor spaces had multiple practical and psychological implications for participants living in overcrowded households. Families, in particular felt there was not enough space for working, learning, and being together all the time. This feeling was exacerbated by a lack of a private garden or proximity to public green spaces. Those in more dense urban areas experienced limited benefits from the permitted time outside for exercise, as they had to walk long distances to reach public parks. They described also experiencing increased stress when encountering large numbers of other people taking their daily walks in highly populated neighbourhoods.

5.36 The psychological and emotional consequences were family discord, and strained relationships due to increased arguments and tensions. This in turn affected education, work, and sleeping patterns.

5.37 Overall, this ‘shrinking’ of already overcrowded spaces overlapped, in some instances, with additional financial pressures, resulting in a feeling of hopelessness and an inability to escape or change their living situation.

5.38 The COVID-19 pandemic, and subsequent lockdowns, had implications for the vast majority of people in terms of their day-to-day lives and experiences of home. It is important to consider these impacts when assessing how the pandemic may have changed the perceptions of those in overcrowded housing.

Implications for members of the household

5.39 This section covers approaches that households implemented to deal with the practical implications of a lack of space in the home. It then goes on to set out both the individual and interpersonal consequences of living in overcrowded circumstances.

Responding to ‘overcrowded’ circumstances

5.40 Participants described a range of mechanisms employed to cope with a lack of space within the home. The options available to a household were dependent on its composition; both in terms of the physical make-up of the property and the number and ages of household members and their relationships to each other. Approaches to lessen the impacts of overcrowding were not always used and/or possible.

Physical coping strategies

5.41 These strategies involved physical changes to the space or its expected use. For example, participants used living rooms or communal areas as sleeping spaces, either on a temporary or permanent basis. In the former case, sofas would be used to sleep on by male family members, and the room would revert to its usual purpose as a shared living space during the day. In the latter instance, communal rooms would be converted to an additional bedroom, and the household would therefore lose a room normally used for social purposes. This option therefore tended to be used only by households with more than one living space in the property.

5.42 Participants were more likely to express satisfaction with a permanent conversion than the short-term option, as it had greater benefits for sleep and for relieving the space demands of the household as a whole. This was not considered a solution in instances where families wanted to be rehoused so that their needs for communal space as well as sufficient bedrooms could be met.[footnote 5]

5.43 Another example was extra consideration and planning of the layout and use of available space. It included the creative use of storage and zoning, resulting in thoughtfully configured spaces to give household members a sense of having separate areas for different activities. This applied to both bedrooms and other rooms within the home. Participants described partitioning existing bedrooms to create additional smaller rooms and deliberately leaving doors open to create the illusion of more space. Implementing techniques to enable best use of the space often required considerable time and effort from participants as well as a high level of organisation and tidiness.

‘I’m crazy organised. I find a solution for everything and I’ll find a creative way of storing it. My kitchen, everything has crazy storage solutions.’ R1, F, 30 - 49, B, H3

Relational coping strategies

5.44 A second set of coping mechanisms can be described as ‘relational’ strategies. These refer to techniques which involved how household members interacted with each other within the household and how participants related to the home itself.

Timesharing

5.45 These strategies included the time-sharing of rooms for specific activities such as cooking, dining or recreation but this also extended to bedrooms for sleeping. Working patterns at times facilitated the sharing of spaces, for example, where one person using a bedroom worked nights and another worked during the day. Time-sharing was arranged between different family units within a household as well as within the same generation of a family, for example, if there were too many siblings to all eat in the kitchen at the same time.

‘We have different times that we all maybe watch TV, or even in terms of being in the kitchen, we’ll give each other space or give each other time.’ R4, M, 30 - 49, P, H3

Needs based allocation of space

5.46 Participants also described having to prioritise need within the household, for example, ensuring the kitchen table was available for a younger person preparing for exams.

‘My daughter sometimes uses (the kitchen table) for homework… When we know she’s in the kitchen, we tend not to go in. She’ll get on with her stuff straight after she comes in kind of thing.’ R3, F, 30 - 49, B, H3

5.47 Prioritisation entailed value-laden decisions around the importance of competing needs and could have gendered implications, for instance, in terms of which family member’s contribution to the household was most highly regarded. For example, female participants described giving up their use of a space if it was needed by a male partner for work or an activity.

Removing oneself from the home space

5.48 Another way of coping with an overcrowded situation was to spend more time outside the home in public or community spaces or in relatives’ homes. Therefore the ‘home’ extended outwards to the wider neighbourhood and increased the importance attached to the geographical location of the property and experiences of places near the household. COVID-19 pandemic measures limited this activity for those who relied on spaces outside the home to cope with overcrowding. They described feeling that their world had ‘shrunk’ which made it more difficult to handle their overcrowded situation.

Consequences of living in overcrowded conditions

5.49 Participants highlighted both positive and negative consequences of living in ‘overcrowded’ accommodation. As depicted in Figure 5.4 these related to the individual directly or to the interpersonal relationships between household members.

Figure 5.4: Consequences of living in overcrowded living

Positive and negative consequences of overcrowding listed in two columns: individual and interpersonal.

For the individual

5.50 For individuals, a lack of space had practical implications in that it restricted the types of activities that could be comfortably carried out within the home. For children and young people, this included play and study. While for older adults, difficulty with home working arrangements were discussed as well as solo recreational activities such as watching television. The practical consequences extended to the ability to store possessions and participants referred to a constant cycle of assessing and prioritising which items should be kept.

5.51 Both young people and adults struggled to get adequate sleep, either due to sharing bedrooms with multiple others or having to use sofas for sleeping on.

‘They can’t sleep on a bunk bed any more […] they keep saying that they can’t get to sleep, their legs are too long.’ R2, F, 50+, P, H3

5.52 Participants also referred to a range of emotional and psychological consequences for the individual. Parents expressed concern that a lack of space may have affected their young children’s development, connected both to having insufficient room to play and negative emotions created by living in a stressful environment. Teenagers and young adults living in the family home missed having their own private space. Female participants with experiences of living with in-laws described a loss of independence.

5.53 Overcrowding also exacerbated existing stressors, such as physical or mental health needs and made it more difficult to manage existing health conditions. Where a property did not accommodate the additional physical health needs of a household member, this amplified dissatisfaction with the overall living situation. Mental health needs made the interpersonal challenges of overcrowded living more difficult to cope with.

5.54 Participants described a sense of shame or embarrassment of their housing situation which led them to feel disconnected from friends and colleagues who did not share the same experience.

‘It’s not very nice because when you see people, when people see us coming in, they probably think, oh my God, such a small house and they’re all sleeping on top of each other.’ R2, F, under 30, B, H1

5.55 Participants speculated that many of these consequences of living in overcrowded housing may have long-term implications for their mental wellbeing in the form of lasting ill health brought about by their stressful housing situation. Similarly, they were concerned that having insufficient space to study would limit children and young people’s educational attainment and, subsequently, their employment aspirations.

For interpersonal relationships

Positive experiences

5.56 In contrast to the implications for the individual, participants described various ways in which living with others led to positive experiences. Despite the more desirable aspects of living in larger households, these participants still sought accommodation that would better meet their need for space. They felt that having more space could in fact increase the benefits of living with others if they had enough room to enjoy activities together.

‘It’s like if had a bit more space then it’d be nice. I would just get one big, massive table and the whole family can sit down and eat at the same table.’ R2, M, 30 - 49, P, H1

5.57 Participants enjoyed the close family bonds that living in larger family units created. If a family lived in an area with a weaker community support network, then close relationships between siblings were especially valued. Having a support network within the household and people to spend time and socialise with offset some of the emotional and psychological consequences for the individual.

‘It can be fun because we spend a lot of time together, we eat together, so there are obviously some benefits when you’re spending time with your loved ones.’ R2, F, under 30, B, H1

5.58 In households composed of younger children with adult siblings, extended family or grandparents, their support with childcare and other household chores relieved pressure on parents. Living in a property with others of working age also allowed for the sharing of costs between household members, and thus relieved pressure on chief income earners. In multigenerational households, parents valued grandparents passing down cultural practices to their children.

‘…because I’m working I can contribute to the bills, so there’s less pressure. It’s not only one person. If I lived on my own it’s all on me.’ R3, M, under 30, B, H2

Negative experiences

5.59 However, participants also described negative consequences for interpersonal relationships. This included arguments and discord within the household where family members felt they were competing for space and not having their needs for privacy met.

5.60 A lack of space could also have economic consequences, for example, being unable to bulk buy or batch cook and therefore having to spend more by shopping more regularly. This resulted in added financial strain which could increase tensions within the household. Where there were challenges with moving around in the same physical space, this was a constant and persistent experience.

‘You’re living on top of each other and it’s, you’re constantly frustrated with each other because you just don’t have the space to move around. It does cause conflict, and it’s not… It sounds really trivial, but it isn’t.’ R1, F, 30 - 49, B, H2

5.61 It was also difficult for couples to spend quality time together. While not mentioned explicitly by participants, it is possible that this factor could have a detrimental effect on relationships in the long term.