Open aid, open societies: a vision for a transparent world

Updated 6 March 2018

A woman from the Jogbahn community in Liberia participates in a workshop held by the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI).

February 2018

Foreword from the Secretary of State

Penny Mordaunt

In Britain we are proud of our democracy and proud of our openness. As British citizens, we can access information to make choices and have a say in decisions which affect our lives. For the same reasons, DFID helps to improve transparency in developing countries to improve the lives of the very poorest and most marginalised.

In this Transparency Agenda I am setting out how we will strengthen our ambition on this vital issue - a transparency revolution for a fairer, more equitable world. A world which it is in all our interests to achieve.

In more open societies, ideas and innovation can flourish, the most marginalised are empowered, and all voices are heard. But in many countries, basic freedoms are under threat. DFID will do more to support governments in developing countries to become more open; allowing oversight agencies, citizens, and the media to scrutinise how money is spent and enable people everywhere to hold their governments to account.

DFID works hard to promote economic growth and support countries to raise their own revenue - ensuring they can stand on their own two feet. And we know that over the long term, open and inclusive societies have stronger growth. Through this agenda DFID is increasing its support to tax raising and the management of public finances. Transparency is crucial in making sure these efforts work - building citizens’ confidence and trust in how their money is spent, and encouraging them to pay taxes.

Transparency doesn’t however stop at national borders. The fairness of international systems affects us all. We will work at home and overseas to close the international opportunities that allow unscrupulous individuals to get away with corruption. This includes building global transparency standards in government contracts, company ownership, and the oil and mining sectors to make sure that money from the very poorest countries in the world reaches the people that need it most.

How we spend our own aid is important. Both UK taxpayers and the people our aid helps want to know how we are making a difference. ‘What are you going to do with my money? How do I know you’ll spend it well’? I am proud of DFID’s leadership on aid transparency, but there is always more to do. We are holding our development partners to high standards and many more organisations are publishing aid data. We now need to make sure that we use this data to improve what we do.

DFID has been, and will continue to be a global leader, going further in our work to promote transparency across our developing country and international programmes to deliver greater accountability, drive economic growth and improve the lives of poor people.

Penny Mordaunt Secretary of State for International Development

Key messages

Transparency matters for sustainable development. When people can see how their governments spend money and what it achieves, and have a say in how their country is run, then trust can be built. With open, accountable and responsive governments, citizens are more likely to pay taxes, vote, and get involved in decision-making. Economies are more likely to grow, and aid dependency can and should end. By shining a light on financial flows and decision-making, transparency also reduces opportunities for corruption.

UK government departments are working more closely than ever before to deliver the UK Aid Strategy, demonstrating global leadership in making development assistance traceable. UK taxpayers and people in the countries our aid supports want to see where and how money is spent – and what it delivers.

Going forward…..

We will continue to lead by example, improving the quality and value of our own evidence and data, increasing transparency of our delivery chain, and demonstrating the value of aid data as we use it ourselves. We will continue to demand high standards and encourage similar leadership from our partners.

Where greater transparency is still needed, we will lead on establishing new global initiatives which will close the opportunities that allow assets and corruption to be hidden. The UK established a public database of who actually owns and therefore benefits from companies. And having adopted the open contracting standard, we will help more countries to do the same. We will start discussions on the transparency of commodity trading by national governments through brokers in London, Switzerland and Singapore. And we will explore innovative new technologies to help countries fight corruption in the public and private sectors.

We will continue to support existing global transparency initiatives to deliver value, increasing the use of the data and evidence made available. We will continue to play a leadership role to meet the urgent need for open, disaggregated data, and the International Aid Transparency Initiative. We want to see more implementation of standards like the Extractive Industries and Construction Sector Transparency Initiatives. And we will continue to support the work of the Open Government Partnership to open up governments across the globe.

And we will scale up our work on transparency and accountability in DFID’s partner countries. We will work with developing countries to open up their institutions and enable those who scrutinise the work of governments – parliaments, supreme audit institutions, civil society, and the media – to hold those in power accountable to citizens.

But we cannot do it alone. A transparency revolution on this scale requires a global effort. Governments, big business and institutions must be part of the change.

1. A vision for a transparent world

Data sources

Citizens today have access to technology and data that would have been unimaginable a decade ago; providing new tools and data sources to monitor what a government promises and delivers. Citizens are expecting and demanding more.

Through support for Sustainable Development Goal 16, political leaders across the world have committed to building effective, accountable and inclusive institutions. And they have pledged to leave no-one behind in this pursuit; ensuring that the most vulnerable are included in the development of open societies.

But there are formidable challenges. In the poorest countries of the world, governments lack the capacity to implement transparency reforms and respond to citizens’ demands. Poor public financial management increases the risk of aid diversion, meaning that in many places donors cannot support government delivery of services such as health and education. The accountability institutions through which citizens and elected representatives can scrutinise information and hold leaders to account can be weak. And around the world, civil society organisations, human rights activists, and journalists are experiencing an unprecedented level of threat, and they are being arrested or killed in shocking numbers.

This results in a lack of trust from citizens in their governments. Votes can be bought, because people don’t see the opportunity for change; people don’t pay taxes because they do not believe the money will be used properly; and services are accessed through bribes, because citizens cannot see any other way to get even basic healthcare or education. People suffer in poverty, and citizens become disengaged. In some contexts this can feed grievances, based on lack of opportunity and marginalisation, which lead to support for violence and extremist groups.

The cycle can be broken. When governments show openness and willingness to listen to citizens’ concerns, and when they respond to those concerns, trust grows. Women and men are more likely to engage in political processes. Citizens begin to pay taxes because they see that they are getting something for their money; and with more taxes collected, service delivery improves.

Box 1: Transparency can increase tax revenue

In South Kivu Province in the Democratic Republic of Congo citizens voted on budget allocations using mobile phones. When citizens saw the roads and schools being repaired that they had voted for, tax collection jumped 16-fold.

In the long run transparency helps drive growth and development. Evidence shows that more transparent countries have higher foreign direct investment inflows and lower borrowing costs[footnote 1]. The 2017 Global Anti-Corruption survey polled more than 300 senior executives at US, European, and Asian companies each with annual revenues of $150 million or higher, and found that 42% had pulled out of a deal due to corruption risks[footnote 2]. A more transparent business environment makes it easier for responsible businesses to operate. And public sector transparency can promote competition for government contracts, reduce corruption, and increase government effectiveness. Although some countries have achieved impressive growth without being open, inclusive societies have, over time, been far more successful in promoting growth and stable development[footnote 3].

But transparency on its own is not enough. To be useful, the evidence provided needs to be meaningful to ordinary people. Too often, data is not presented in an understandable way that enables citizens to find, interpret and use it. Evidence must also be accessible to parliaments, audit offices, media and civil society organisations that can monitor and champion improvements in services. The more information is put into the public domain and used in this way, the more accountable and responsive institutions become. For example, evidence shows that countries with a strong civil society tend to have less corruption, higher integrity, and more equitable allocation of funds for the public good[footnote 4]. Change is most likely to happen when diverse groups of people come together to rally around specific reform issues and make demands on their governments[footnote 5].

Image 1: Woman asking a question on BBC Media Action’s Open Jirga - a debate show broadcast in Afghanistan. Photo credit: BBC Media Action

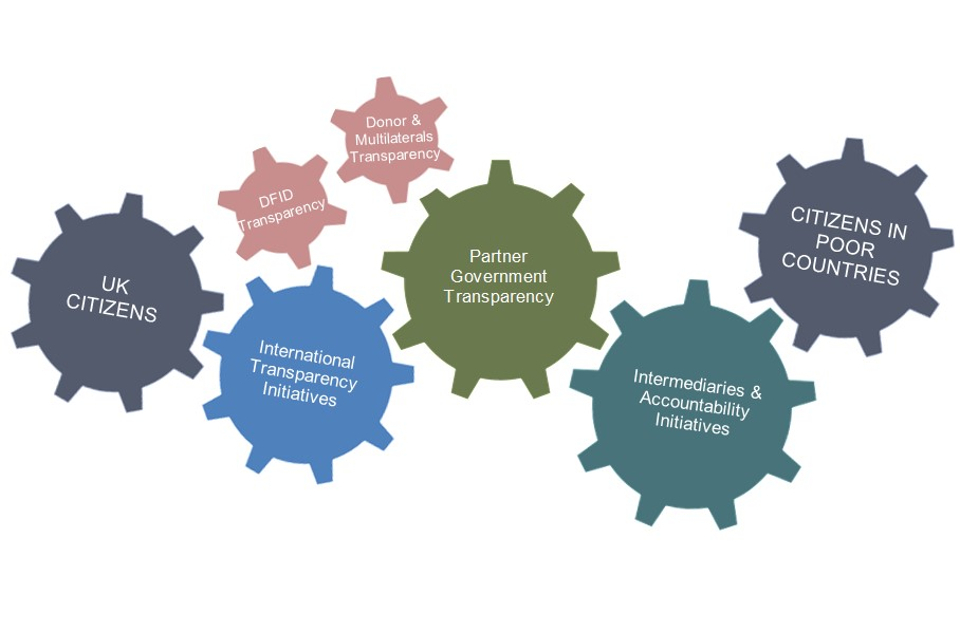

2. What we’re going to do

Reform the international aid system

UK citizens want to know who the government helps and how when using their taxes for development assistance. We intend to maintain DFID’s record as one of the world’s most transparent donors, remaining near the top of Publish What You Fund’s Aid Transparency Index. And we will work across the UK Government to ensure that all departments that provide Official Development Assistance meet the UK Aid Strategy commitment to achieve a ‘good’ or ‘very good’ Aid Transparency Index rating by 2020. We will continue to publish all independent evaluations of DFID’s work, enabling full scrutiny of the impact of our work. And we will continue to improve the trustworthiness, quality and value of our own data, consult users of our data to understand how we can improve what we publish, and find ways to make more effective use of data ourselves .

Box 2: The International Aid Transparency Initiative DFID was a founding member of the International Aid Transparency Initiative which was set up to manage an open data standard allowing the reporting of development spend and results in a single place. Nine years on, it has 568 publishers and continues to represent the foremost mechanism for sharing aid data. We will continue to collaborate with international initiatives that promote aid transparency, driving greater use of aid transparency data for greater accountability and effectiveness. We require all our implementing partners to publish to the International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) or other relevant international transparency standards, and to pass the same expectations down their delivery chains. With our private sector contractors and our civil society organisation partners we will bear down even harder on costs, fees, and overheads to stimulate reforms and efficiency. We will continue to track and report spending related to gender equality through the Organisation for Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) gender policy marker; and the Global Partnership for Effective Development.

With multilaterals such as the UN and the International Financial Institutions, we will pursue ambitious transparency and accountability objectives, encouraging them to be more open about their own spend and promoting open procurement, including open contracting and action on beneficial ownership. We will improve current processes for reporting and checking on multilateral spend and results, including hard-to-measure Global Goal targets, and support new initiatives so that citizens can understand and monitor the impact of their programmes. We will expect all our partners to pass transparency expectations down the delivery chain, to enhance the quality and promote the use of data.

We will push for the humanitarian system to become more efficient, effective, transparent and accountable including on gender and disability targets, through the UK’s active engagement in the Grand Bargain agreed at the World Humanitarian Summit in 2016. And we will regularly ask those on the ground whether we are using our money to best effect, integrating beneficiary feedback mechanisms into more of our programmes. We will ask our multilateral, private sector and civil society partners to show leadership, strengthening how they use data and listen to their beneficiaries as they implement our programmes.

Spearhead new global standards

The UK Government published its first Anti-Corruption Strategy in December 2017 and set out an ambitious framework for tackling corruption both at home and abroad.

The strategy renews the UK’s commitment to champion international action by governments, business and NGOs to fight corruption, building on the commitments made at the London Anti-Corruption Summit in 2016.

The UK already requires companies to submit details of their real beneficial owners – information which is then made public by the UK government. The UK will lead new global transparency disclosure standards, pushing for more action in three areas:

We continue to lead by example and support the development of a Register of Open Ownership, a new global database of who really owns, controls and benefits from companies in the UK and overseas. And we will support others to do the same, such as by establishing national beneficial ownership registers, adding a requirement for beneficial ownership disclosure in their public procurement or by subscribing to the Open Ownership Register (a global register which the UK has already supported) in the period up to 2020.

We will continue to work with the OECD Global Forum, and the Financial Action Task Force, on the availability of beneficial ownership information in the domestic and cross-border context. Analysis by the ONE Campaign suggests that at least $1 trillion is taken out of developing countries each year[footnote 6] through corrupt or illegal deals, many of which involve anonymous companies. Making transparent the real or beneficial owners of companies can help to reduce tax evasion, prevent illicit financial flows including terrorism financing, and enhance revenue collection and the business climate.

Box 3: Public Contracts Some 57% of foreign bribery cases prosecuted under the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention involved bribes to obtain public contracts. Given that public contracting represents about 15% of global GDP, this translates into massive costs for everyone: governments lose money and trust, businesses stop participating in the marketplace, and citizens receive sub-standard goods and services at uncompetitive prices.

The UK was the first G7 country to adopt the Open Contracting Data Standard in its central procurement authority. Building on this contracting transparency, we will support more partner countries to meet the standard in public procurement, ensuring transparency across the full procurement process. This will expose who is winning public contracts, reducing the scope for contracts to be given on the basis of corruption or collusion and making it fairer for businesses to compete. In particular, we will support 16 countries to implement more open contracting in public procurement by 2020 and encourage more countries to commit to openness across the contracting cycle, from planning to tender, award, contract and implementation.

We will lead an international dialogue on global commodities trading. In many oil-producing countries, the government receives an undisclosed share of production, usually known as ‘production entitlements’. This oil is then typically traded by traders based in the UK, Switzerland or Singapore and the money is returned to governments or institutions in the country of origin. And the numbers are substantial; between 2011 and 2013 in Sub-Saharan Africa the sale of states’ share of production was the biggest revenue generator – on average 56% of state income.

Strengthen existing global initiatives

The UK already supports a number of existing global initiatives designed to drive up transparency in specific sectors known for pervasive corruption, collusion and secrecy; and over the next five years we will push for greater openness on data and financial flows.

Box 4: Ghana in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) When Ghana joined the EITI in 2007 its early reports revealed very low levels of government revenues from the gold mining sector. Consequently, Ghanaian civil society began advocating for change. This led to revisions in Ghana’s mining tax law with revenues from mining more than doubling between 2010 and 2011, from $210 million to $500 million. And a new Act was passed which allows the government to invest between 50% and 75% of oil revenues in social and infrastructure programmes.

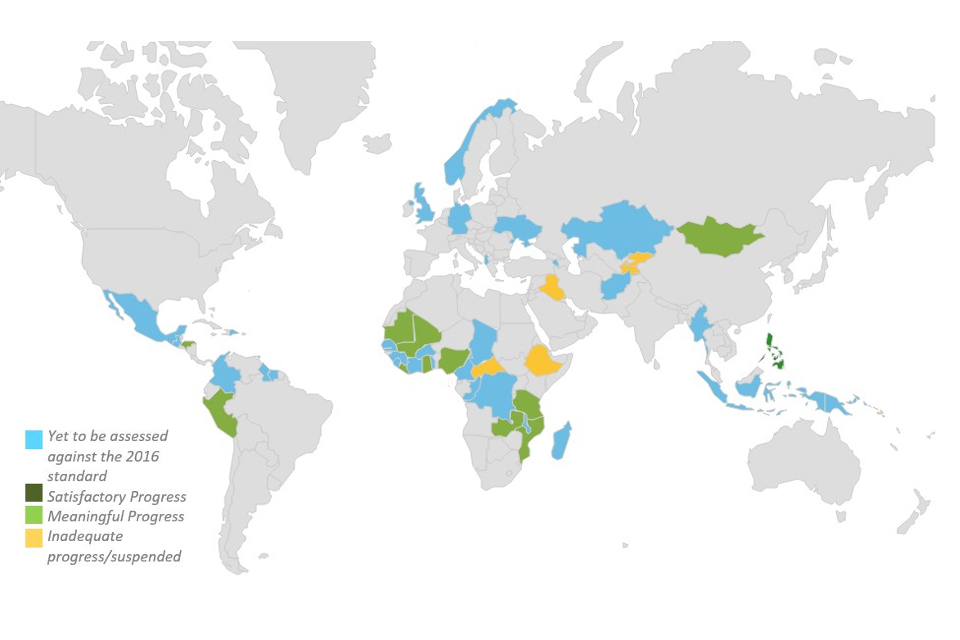

We will continue to support the Extractives Industries (EITI) and Construction Sector Transparency Initiatives – global standards to promote the open and accountable management of oil, gas and mineral resources and of the construction sector. We will also continue to champion the EITI and the UK’s extractives mandatory reporting regime, including through the UK review of implementation of mandatory reporting in 2017. We will support developing countries to comply with the EITI Standard, including disclosure of beneficial owners by 2020 and continue to learn lessons about how to strengthen the initiative and tackle the most difficult issues. Similarly, limited land documentation and weak land governance can lead to ‘land grabbing’ and drive corruption and exclusion. So we will work towards establishing a land transparency initiative that works with governments and companies to promote greater transparency and accountability on land transactions across the globe.

Map - Figure 1: EITI Implementation Status

We know that data is critical. DFID will continue to play a leadership role working through partners such as the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data to strengthen data systems in a coordinated, strategic way; and ensure that they deliver data that is disaggregated and therefore meaningful to those most often left behind or harder to reach.

We will continue to ensure all DFID-funded research evidence and evaluations are published in accessible and useable formats, and we will support partner countries to strengthen their ability to generate and use scientific research in decision-making.

We will support a roll-out of IMF fiscal transparency evaluations which help governments to obtain an accurate picture of their finances when making economic decisions. And we will continue to provide strong support as the International Aid Transparency Initiative matures, to make it more user-friendly and promote widespread use of its data.

We will drive global efforts to strengthen international transparency in tax. We will continue to support countries to meet standards on tax transparency by working with the Global Forum on Transparency and Exchange of Information for Tax Purposes. With the Global Forum and HMRC we are already supporting pilots in Ghana, Pakistan and Nigeria to introduce the Automatic Exchange of Information. We will also continue to support the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) Inclusive Framework which enables developing countries to join international discussions on international tax standards on an equal footing. The BEPS project helps tackle gaps and mismatches in tax rules which allow taxpayers to artificially shift profits to where there is little or no economic activity.

And we will support transparency reforms in specific sectors; such as in the defence sector, where we know that corruption can feed terrorism, organised crime, and instability; and reduce the effectiveness of armed forces. We will do this by financing the production of the ‘Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index’, as well as through work supporting governments and companies to improve their transparency and approach to anti-corruption in the defence sector. We also know that illegal forestry damages forest-dependent communities and prevents sustainable growth so we will work to reform both the governance of forest and trade markets, such as timber, soy and palm oil to make them more transparent and reduce the illegal exploitation of forest resources and secure benefits for poor communities.

We will continue to support the Open Government Partnership (OGP) – of which the UK was a founding member and which now has over 70 member countries – making sure that all citizens including women, people with disabilities, and those most often excluded or left behind in developing countries are closely involved in the development of ambitious National Action Plans. These plans strengthen government transparency and civic participation and include commitments across a range of sectors and transparency initiatives. For example, Liberia has made commitments to open up information on foreign aid and establish an open data portal at the Ministry of Finance, including access to raw data in machine readable formats. We would like to see much more learning across global initiatives to help realise the shift from collating and publishing data to its use and impact. The OGP plays an important role in encouraging this. We will work closely with the World Bank on its commitment to support at least a third of countries eligible for International Development Association funding to operationalise agreements made as part of their OGP plans.

Do more in the poorest countries to open up governments

We will complement these global initiatives with a focus on transparency and accountability in the countries in which DFID works. We know that influencing power structures or institutions is deeply complex. UK government departments now collaborate more closely together than ever before – to ensure that a detailed understanding of the specific political context in each partner country informs development decisions and programming work. And it is this locally-informed and politically smart approach, drawing on the latest evidence, which enables us to support transformative reforms. Where we see opportunities for change, we will scale up DFID’s work. A focus on fiscal transparency will be at the centre of our efforts. We will support national governments to open up their budgets to scrutiny. Where there is momentum for change we will support reforms which improve transparency of government expenditure, and enable citizens to track delivery of services such as health, education, water and sanitation that transform the lives of the poorest women and men, girls and boys. In ten of the very poorest countries we will work with governments to improve the way public money is managed, focusing on budget and procurement transparency, improved external oversight, and local participation. We will work with civil society organisations on their efforts to promote debate around budget data.

Image 2: Anganwadi workers presenting demands for the reversal of proposed budget cuts for the Integrated Child Development Services program in Maharashtra state on April 4, 2016. Photo Credit: Anganwadi Workers Union

We know the importance of parliaments, both for fiscal openness and as the linchpin of democratic systems. When they are effective they provide vital checks on abuse of state power and influence the delivery of sustainable development. When not effective they can block such checks. We will support parliaments to be more inclusive for all citizens, to open up national budgets, to scrutinise expenditure, and to increase engagement with every constituent, leaving no one behind.

We will explore opportunities to scale up support to the independent, intermediary institutions that oversee government delivery, like the UK National Audit Office and the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted) which scrutinises the quality of education. In many developing countries Supreme Audit Institutions lack independence from the executive government, and audit reports can be intentionally misleading, not made available to the public or published too late to have impact. DFID will support audit institutions to improve their capacity, publish accessible reports, and follow through on problems identified.

Box 5: Supreme Audit In Georgia, the country’s Supreme Audit Institution started publishing searchable political party financing data which is now being used by anti-corruption watchdogs to track whether donors and political parties are illicitly benefitting from government contracts.

We will continue to help strengthen the capacity of developing countries’ National Statistical Systems to make data available in an open and transparent way. And help countries to launch successful open data initiatives, use open data in policy design and decision-making, and publish economic data on open data platforms using the latest data-sharing technologies. We will advocate for the disaggregation of data by sex, disability status, and geography in administrative systems we support and we will use our influence to encourage partners to do the same.

In response to the worrying global trends of greater restrictions, intimidation and violence against civic actors, we will scale up support for a healthy, free media and civil society that can champion anti-corruption and transparency and promote debate and uptake of data. This will enable them to operate in a free environment without unduly restrictive legislative and regulatory burdens; and, importantly, without fear. We supported these civil society groups to link up with global transparency initiatives such as the Global Forum on Asset Recovery in December 2017.

And given growing concerns about the risks as well as opportunities in the digital world, particularly around safeguarding privacy, understanding vulnerability and ensuring access to marginalised and excluded groups, we will continue to support open and safe digital spaces. It’s important that the same rights and freedoms that exist off-line are respected in the digital space and that digital technologies have a positive impact on development.

And we will step up our work to fight corruption. In four sub-Saharan African countries we will test out innovative approaches with civil society, law enforcement, and investigative journalists to use greater transparency, to help drive forward investigations and prosecutions of incidences of corruption. Where these approaches work we’ll scale them up to more countries. And we will provide international expertise, partnerships and standards to expose and close down the international routes for grand corruption.

In DFID’s two Transparency Trailblazer countries, Sierra Leone and Ghana, we will significantly ramp up our work on transparency:

- In Sierra Leone, grand and petty corruption is a longstanding and major challenge. The brutal civil war, the Ebola epidemic, and a crash in iron ore prices set the economy back; and further damaged already weak institutions and government checks and balances. DFID has supported the establishment of an independent audit service, reforms in public financial management, and the Pay No Bribe digital platform, which maps real-time anonymous reports of bribes in health, education and the police, and publishes government responses. DFID also supports a network of civil society organisations which collect data from people on their access to basic services and feed this back to government for action. We will build on this work with a particular focus on the ways in which government systems allocate and account for public resources; as well as the collection, use and publication of data in programmes.

- In Ghana, the new government is leading transparency initiatives such as the establishment of an Office of Special Prosecutor to prosecute corruption-related offences, the passing of Beneficial Ownership Transparency legislation, and the long-outstanding Right to Information Bill. The UK will ramp up our efforts, delivering a dedicated anti-corruption programme, and building on long-standing work to increase transparency and accountability. We will support the role of Parliament and the implementation of EITI standards to drive better governance and transparency of the extractives sector in contracting and commodity pricing. We will also seek ways to support the implementation of recommendations from a recent study on open contracting in Ghana.

3. We’re going to work with others to deliver this

We are not alone in wanting to push greater transparency. So we will continue to use our influence on the global stage, such as through the 2018 UK-hosted Commonwealth Summit. We will work with other countries through the G7 and G20, and with other aid donors through groups like the Nordic+ and OECD Development Assistance Committee, to make sure our message is heard.

We will work with UK businesses, the private sector, other UK government departments, and global civil society organisations to explore the demand for services which help companies prevent bribery and share successful business practices for engaging with new markets in developing countries. We’re investing in new technologies to help businesses trace their supply chains. And we’ll make sure that transparency and anti-corruption are part of the UK bilateral and regional trade dialogues, as new trading agreements are explored.

Image 3: President of Estonia Kersti Kaljulaid discusses how open government can renew democracy and rebuild citizen trust alongside other high-level leaders during an Open Government Partnership (OGP) event at the 72nd United Nations General Assembly; Photo Credit: OGP, Kal Dolgin

4. In conclusion

We know that a more open, more accountable world must be the foundation on which democracies and global prosperity are built. This happens when we and others publish evidence and data which is meaningful and when others can translate that information so that it reaches and makes sense to ordinary women and men, including the most marginalised, empowering them to speak out and hold their leaders to account.

We will lead a transparency revolution which will help people push their own governments to do better and take responsibility for their own development – helping them to move away from aid dependency. We will reform the global system to do more and close the opportunities which allow the unscrupulous to get away with corruption. We will monitor these improvements, track the ways that transparency leads to change on the ground, be adaptable, and shift course when necessary. And above all, learn about what works and what doesn’t.

We know that this will take time, but we are joining up across government and internationally to deliver the change. This is in our national interest; and will also help build a more stable, more prosperous world for all.

Image: 4 BBC Media Action, filming of Sajha Sawal in mountains in rural Nepal. Sajha Sawal (Common Questions) is a weekly political debate programme broadcast across Nepal on radio and TV. Photo Credit, BBC Media Action

5. References

Front Page Photo: A woman from the Jogbahn community in Liberia participates in a workshop held by the Sustainable Development Institute (SDI). Using data released through an OGP commitment on commercial land use rights, Liberian civil society is working with other stakeholders to pass the Land Rights Act; Photo Credit: Morgana Wingard of Namuh Media

-

http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199917693.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199917693 ↩

-

https://emarketing.alixpartners.com/rs/emsimages/2017/pubs/FAS/AP_Global_Anticorruption_Survey_May_2017.pdf?_ga=2.41840290.1682190560.1507130755-126164169.1507130755 ↩

-

http://whynationsfail.com https://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDRS/Resources/WDR2011_Full_Text.pdf https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dfids-economic-development-strategy-2017 ↩

-

E-Pact (20016), Macro-Evaluation of DFID’s Policy Frame for Empowerment and Accountability annual technical report: what works for social accountability? ↩

-

http://itad.com/works-social-accountability-findings-dfids-macro-evaluation ↩

-

https://www.one.org/international/policy/trillion-dollar-scandal ↩