Mortality Insights from GAD - December 2020

Published 17 December 2020

COVID-19 risk factors and indirect mortality impacts

Welcome to Mortality Insights. In this edition we summarise the various risk factors associated with COVID-19 mortality and explore the indirect impacts on mortality that the pandemic might have.

The latest on COVID-19

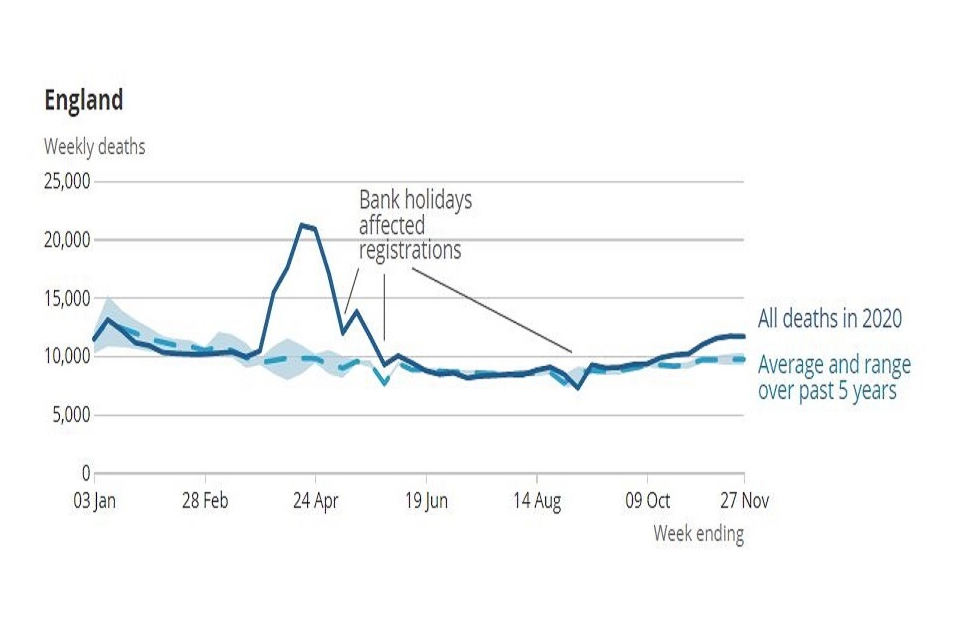

As we are all acutely aware, we are now in the midst of a ‘second-wave’ of the COVID-19 pandemic and sadly this is likely to result in an increased number of deaths over the winter. As shown in Figure 1 below, a higher number of deaths than would normally be expected has been witnessed since mid-October.

Figure 1: All-cause mortality in England, 5-year average with spike for COVID-19 deaths (source: ONS)

Thankfully, to date, the extent of these so called ‘excess deaths’ is lower compared to the ‘first-wave’ during the March to June period. This is perhaps reflective of various differences between the first and second waves, including:

-

The virus is spreading at a slower rate in the second wave compared to back in March. This is primarily due to the range of measures that remained in place after the first wave. These included restrictions on mass gatherings, social distancing, wearing masks and many people continuing to work from home.

-

Wider testing was in place leading up to the second wave, meaning ‘hotspots’ could be targeted with measures and restrictions could be applied sooner.

-

Medical treatment has improved building on the lessons learned from the first wave.

There are however causes for optimism with the first vaccinations underway and the daily number of positive cases having fallen during November, although rising again in December. However, it is likely that COVID-19 will remain prevalent in 2021 and the potential for a material impact on mortality will remain for several months yet.

There is increasing evidence that the COVID-19 mortality rates can vary significantly based on age, sex, level of deprivation, ethnicity and whether an individual has any pre-existing health conditions. In this edition of Mortality Insights, we start by examining how the likelihood of dying from COVID-19 varies with these factors. We also consider some of the indirect mortality impacts of the pandemic.

There is a substantial volume of excellent data, analysis and research published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and others in relation to COVID-19. We have included a list of some of these sources at the end of this article if you are interested in finding out more.

COVID-19 risk factors

It has been well documented that the elderly are at most risk from COVID-19, but there are many other risk factors that ONS data suggests may influence the likelihood of dying from the illness.

-

Gender – Between March and June in England and Wales, males were broadly 1.5 times more likely to have a death involving COVID-19 compared to females.

-

Level of deprivation – People in the most deprived areas in England were more than 2 times as likely to have a death involving COVID-19 compared to the least deprived areas between April and July 2020. This is likely to reflect both an increased incidence of catching the virus, perhaps due to living conditions and a reduced ability to work from home, as well as not surviving the virus having caught it. However, it is worth noting that a similar differential between the most and least deprived areas is also present in non-COVID mortality.

-

Pre-existing health conditions – 91% of deaths involving COVID-19 between March and June in England and Wales occurred in people with at least one pre-existing condition. The most common conditions were dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, reflecting how the majority of COVID-19 deaths are among the elderly. For people aged under 70 influenza /pneumonia, diabetes and hypertensive diseases were the most common pre-existing conditions.

-

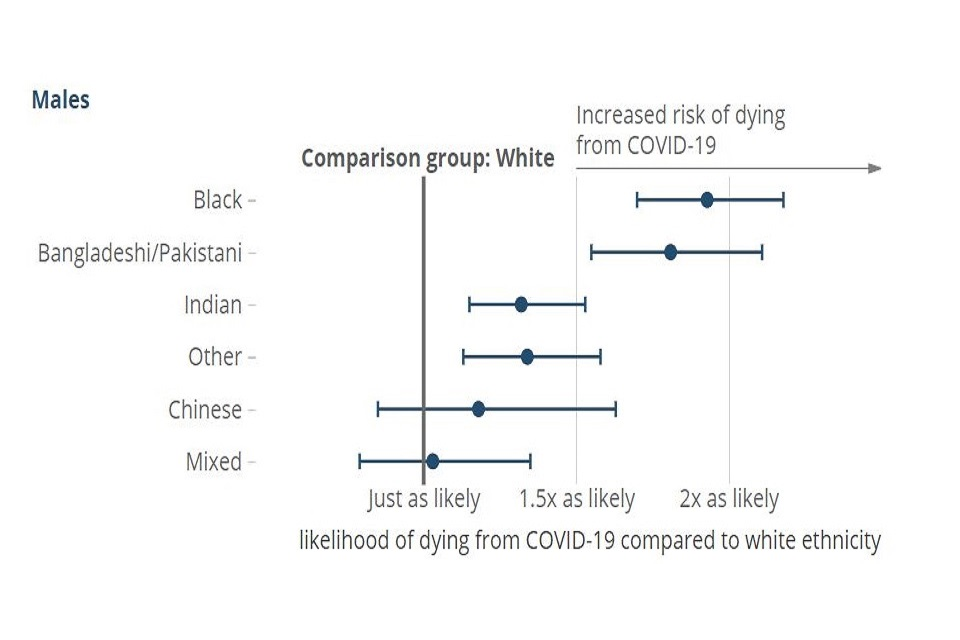

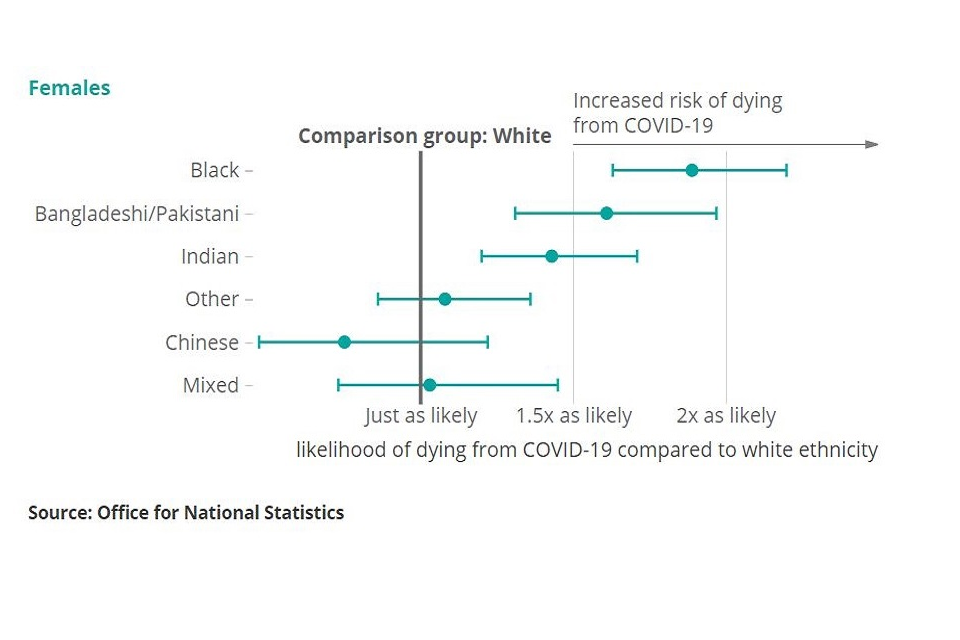

Ethnicity – People of certain ethnicities appear to have a statistically significant increased risk of death involving COVID-19. In particular, those of Black ethnicity are more than 4 times as likely to have a death involving COVID-19 compared to those of White ethnicity. Even after adjusting for socio-economic characteristics (such as levels of deprivation), those of Black ethnicity are still almost 2 times more likely to have a death involving COVID-19 compared to those of White ethnicity. Figure 2 below illustrates the impact for other ethnicities.

Figure 2: Relative risk of COVID-19 related death by ethnic group (after adjusting for age and socio-economic characteristics), England and Wales (source: ONS)

Indirect mortality impacts

Aside from those who sadly die due to COVID-19, there are various other associated factors that could have implications for UK mortality for years to come. Some of these are considered below.

Healthcare - The provision of wider healthcare appears to have decreased since the start of the pandemic. This includes emergency care where perhaps people may have been reluctant to go to A&E due to a perception that they should remain at home and non-urgent elective treatments many of which have been postponed or cancelled.

Economic consequences - The pandemic and associated restrictions have had significant impacts on the economy. As set out in the Office for Budget Responsibility November 2020 economic and fiscal outlook the economy is projected to contract by 11% in 2020, with unemployment expected to rise to 7.5% in 2021. This will inevitably lead to an increased level of deprivation which typically leads to a reduction in life expectancy as considered in our July 2019 edition of Mortality Insights. Furthermore, any long-term impact on the economy may compromise the level of available future healthcare.

Impacts on survivors - It is unclear what the wider impacts will be for those who have lived through the pandemic. Some people who had the virus are still not back to full health (commonly referred to as ‘long-COVID’). More generally, the impact on mental health and wellbeing from a prolonged period of social restrictions could impact future rates of mortality as well as the quality of life in the short term. Conversely, there could be a ‘survival of the fittest’ effect where the population that survive the pandemic actually have an increased life expectancy.

Behavioural changes - There may also be some positive impacts to come from the restrictions we have been living under. For example: social-distancing measures may reduce the incidence of seasonal flu, less traffic on the roads may result in fewer deaths from accidents as well as having a positive impact on air quality and climate change. Whilst any long-term shift to working from home may result in healthy lifestyle changes, such as increased wellbeing and more time to exercise.

Final thoughts

The actual indirect mortality impacts that arise from the pandemic are very uncertain. The above considers some general themes, however it is still too early to know the extent to which they will impact mortality. New research and analysis is being conducted all the time which hopefully will provide a clearer picture in due course, although in practice the various indirect mortality impacts may not emerge for many years.

Useful mortality sources

Please note that analysis is being updated regularly, so the sources below may not necessarily reflect the latest version.

UK Government COVID-19 data dashboard

NHS England COVID-19 hospital data

ONS registered weekly deaths in England and Wales

ONS deaths involving COVID-19 by local areas and deprivation

ONS COVID-19 related deaths by ethnic group

ONS deaths involving COVID-19 occurring in June 2020, England and Wales

ONS analysis of death registrations not involving COVID-19, England and Wales

Any material or information in this document is based on sources believed to be reliable, however we cannot warrant accuracy, completeness or otherwise, or accept responsibility for any error, omission or other inaccuracy, or for any consequences arising from any reliance upon such information. The facts and data contained are not intended to be a substitute for commercial judgement or professional or legal advice, and you should not act in reliance upon any of the facts and data contained, without first obtaining professional advice relevant to your circumstances. Expressions of opinion do not necessarily represent the views of other government departments and may be subject to change without notice.

Quality Assurance Scheme

The Government Actuary’s Department is an accredited organisation of the Institute and Faculty of Actuaries’ Quality Assurance Scheme.