Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) annual report, 2021 (accessible version)

Published 15 December 2021

December 2021

Foreword

The Framework Document that covers our governance requires us to produce an annual report to inform Parliament and the public of the work we have done and our use of resources. It also suggests that the report contain comment on, and recommendations relating to, all aspects of the immigration system.

The new immigration system that began in 2021 coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic. This has produced operational challenges as well as making it difficult to isolate the effect of the immigration changes from the effects of the pandemic. On the operational side, we have heard from a number of stakeholders that the new Skilled Worker route has been launched smoothly and that the streamlining and digitisation of the route are working well. The Home Office are to be congratulated on this achievement. Numbers using the route have now recovered to the levels seen pre-pandemic, with the health sector remaining a key user of the route. Only a small share of visas have been issued to the occupations newly eligible (the RQF 3-5 jobs), though the care sector are actively using the route for senior care workers. We would expect the share of these new occupations to gradually rise over time as firms become more familiar with the new system.

In the last few months, the Government have agreed to some temporary visas for various occupations such as HGV drivers and poultry workers. There is a balancing act here between maintaining the general principles of the new Skilled Worker route and not being completely inflexible in the face of challenges that may have substantial consequences for the economy – some of which are the result of the pandemic. The MAC are generally supportive of the approach the Government have taken, though we have some concerns over the exact details of the routes. If the government wants to establish visa options for roles not currently eligible for the Skilled Worker route, we suggest that it may be more sensible to consider designing a formalised route that can be temporarily accessed under clear criteria, rather than announcing last-minute changes.

We have seen tragic deaths of people in the English Channel in recent weeks as they seek a better life in the UK. The asylum system faces many difficult challenges that must be addressed. The legal and operational aspects of the asylum system are outside of our remit, but the MAC are particularly focused on how good policy can ensure that asylum seekers integrate well into society. In that context, we urge the Government to review the ban on employment for asylum seekers. There is clear evidence of the harm that this causes, some of which we document in this Report, and little evidence that we are aware of that it provides significant benefits. The harm is exacerbated by the increasing numbers of asylum seekers who are having to wait over six months for an initial decision on their application.

We are currently in the middle of a commission investigating the impact of the ending of freedom of movement on the adult social care sector. We provide an update in this report on our preliminary findings and unusually are taking the opportunity to make a formal recommendation to the Government. Given the severe and increasing difficulties the sector is facing in terms of both recruitment and retention, we are recommending that care worker jobs immediately be made eligible for the Health and Care Visa and placed on the Shortage Occupation List. We will be producing the final report in April 2022.

The MAC also produced a review on the Intra-Company Transfer (ICT) route in 2021 which broadly concluded that the route was working well and served a useful purpose for international businesses. Our most substantive recommended change was that the ICT route should become a route for settlement. We also made recommendations on other aspects of global mobility. We look forward to receiving the Home Secretary’s response to this report.

We are again indebted to stakeholders who have taken the time during the year to assist us with our work, both in response to formal commissions and in on-going engagement. We have also continued our active engagement with the Devolved Administrations and have appointed new members of the MAC secretariat in each of the Devolved Nations. Finally, the Committee are grateful to the excellent work that the secretariat has done during this difficult year.

We look forward in the coming year to continue in advising the Government on the development of an immigration policy that delivers for the people of the United Kingdom.

Prof. Brian Bell (Chair)

Prof. Dina Kiwan

Prof. Sergi Pardos-Prado

Madeleine Sumption MBE

Prof. Jo Swaffield

1: The pandemic labour market and the new immigration system

Introduction

At the end of 2020, the UK immigration system saw some of the most substantial changes for a generation, as the UK came to the end of the transition period, having left the European Union. In addition, the UK has experienced significant impacts as a result of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. This chapter will provide an overview of the changes in the labour market, evidence from data on the new Skilled Worker route, and a discussion of the pressures facing sectors that do not have access to the new work route. We would emphasise that there remains a heightened level of uncertainty as to how the labour market will evolve over the next year and the effect that this will have on migration flows.

Overview of the UK labour market

After several years of falling unemployment and a strong labour market, the COVID-19 pandemic was a dramatic shock for the UK labour market. Nationwide lockdowns forced a number of sectors to effectively close down or significantly reduce their activity. This section will cover the overview of the UK labour market in light of the COVID-19 pandemic, exploring employment and vacancies, including a specific focus on sectoral and geographic differences in recovery.

Employment

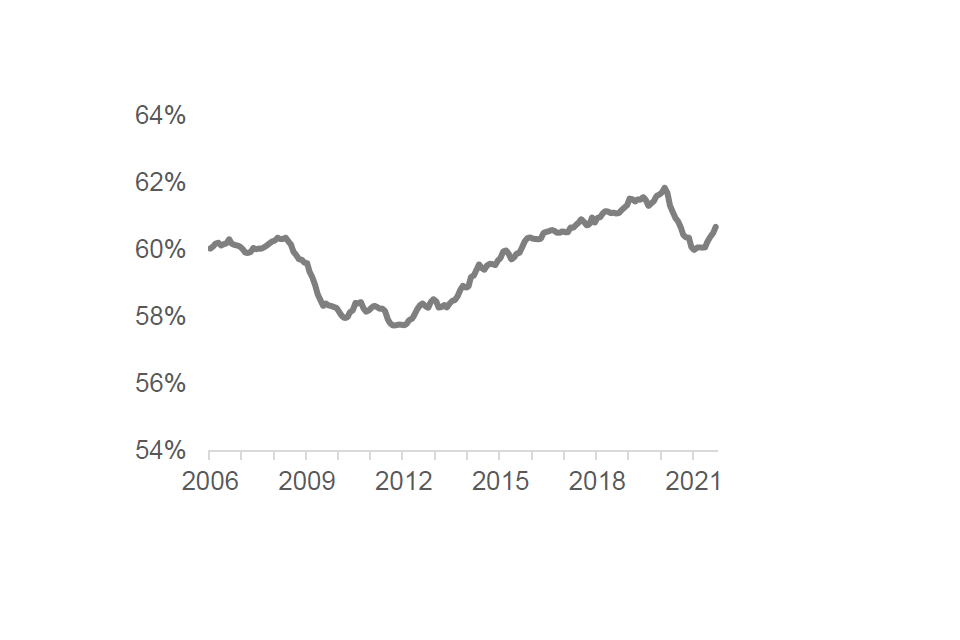

Figure 1.1: Employment rate, 2006 to 2021

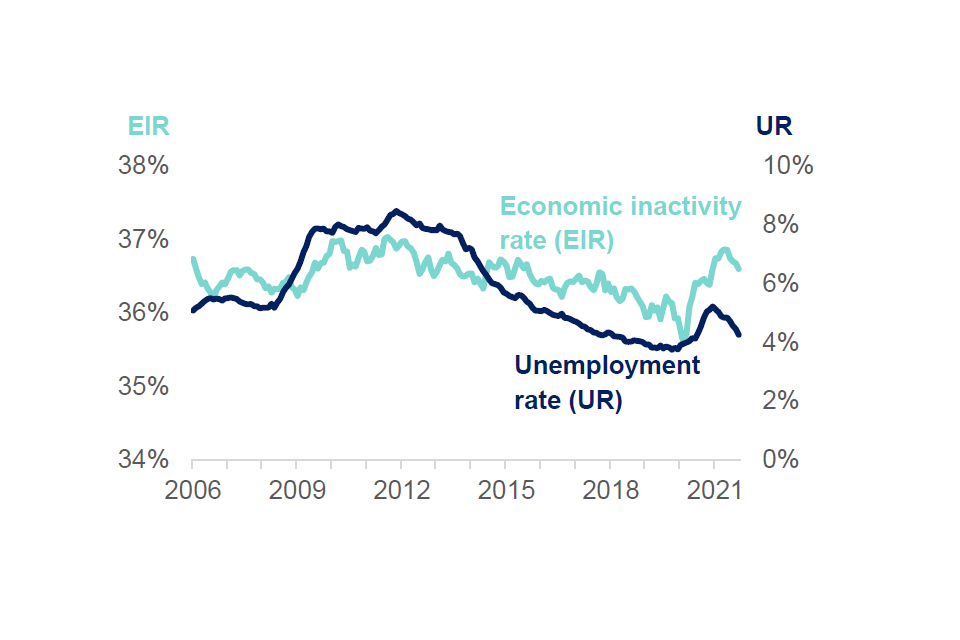

Figure 1.2: Economic inactivity and unemployment rate, 2006 to 2021

Source: ONS, Labour market statistics, November 2021.

Note: Seasonally adjusted data, includes all aged 16 and over. Each data point represents a three month period (e.g. Aug-Oct 2020). Data points have been grouped into year categories for ease of reading the chart, each year includes a data point from Nov-Jan, Dec-Feb, Jan-Mar, Feb-Apr, Mar-May, Apr-Jun, May–July, Jun–Aug, July–Sep, Aug–Oct, Sep–Nov and Oct-Dec. 2021 only includes data points up to May-July 2021.

Figure 1.1 shows the UK employment rate from 2006 to mid-2021. From 2013 until the onset of the pandemic, the employment rate was rising, as the recovery from the global financial crisis gathered pace. With the onset of COVID-19, the employment rate dropped by almost two percentage points, falling to 60% in November - January 2021. The decline in the employment rate was less severe than that witnessed during the financial crisis, despite the much more substantial decline in GDP. The furlough scheme, discussed below, was a key reason why employment held up much better.

Figure 1.2 shows the unemployment and economic inactivity rates for the same time-period. The financial crisis saw a significant and sustained rise in the unemployment rate, peaking at 8.5% in the second half of 2011. Mirroring the rise in employment, unemployment fell consistently over the following years to below 4% by early 2020. Whilst we saw rising unemployment in 2020, coinciding with the pandemic, the peak of 5.2% in Oct-Dec 2020 was significantly lower than that experienced during the 2008 financial crisis. The rise in unemployment has also been substantially lower than was forecast – at the time of our last Annual Report, the Bank of England predicted that unemployment would rise to 6.7% in the final quarter of 2021, whilst the most recent data report an unemployment rate of 4.3%, almost back to pre-pandemic levels. There has been a noticeable rise in economic inactivity rates since the start of the pandemic, with a peak of 36.9% in March – May 2021. This has since begun to decline but the rate is still around one percentage point higher than pre-pandemic levels, suggesting that some individuals have chosen to leave the labour force throughout the pandemic.

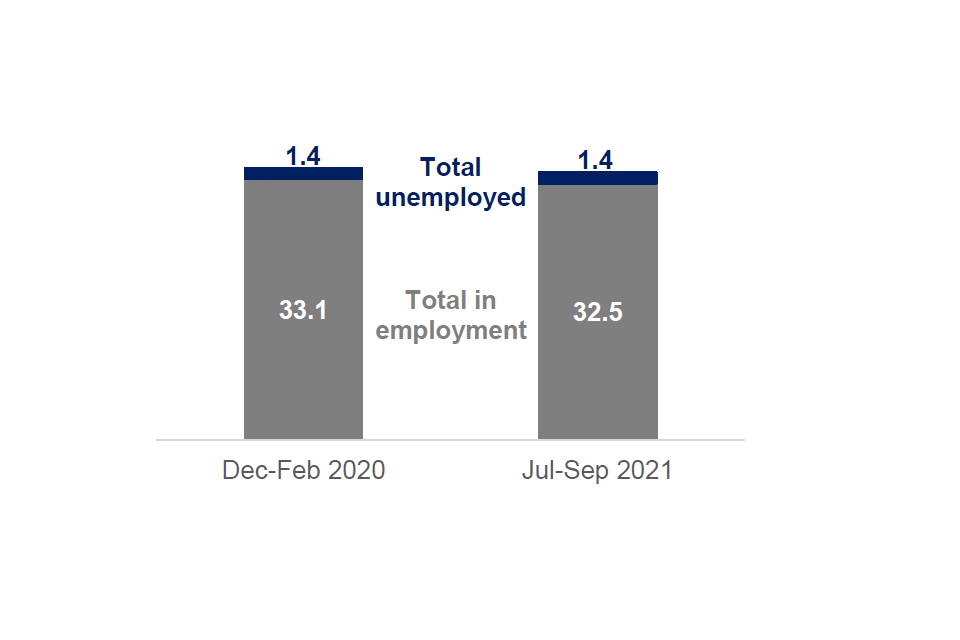

Figure 1.3: Number of individuals in employment and unemployed, millions

Source: ONS, Labour market statistics, November 2021

Note: Seasonally adjusted, for all aged over 16.

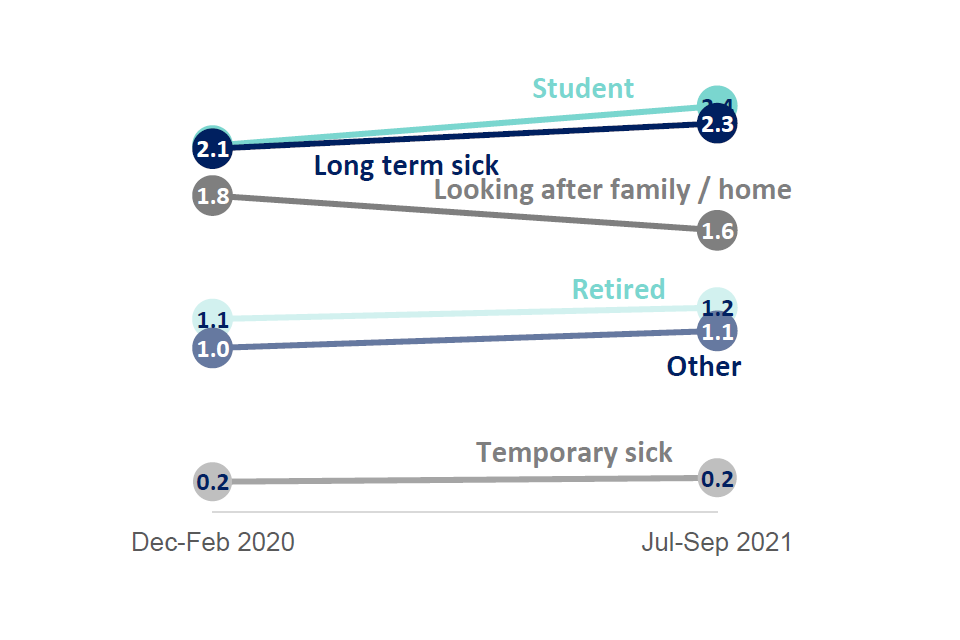

Figure 1.4: Number of individuals in economic inactivity, millions

Source: ONS, Labour market statistics, November 2021.

Note: Seasonally adjusted, for those aged 16 – 64 years.

Figures 1.3 and 1.4 show the absolute levels of employment, unemployment, and economic inactivity both pre-pandemic (Dec 2019 - Feb 2020) and in the most recent data (July - Sep 2021). The number of people in employment has declined by just over half a million between these dates, highlighting that the labour market has still not fully recovered. However, the make-up of employment has changed significantly. ONS data shows that the number of employees in employment are now 255,000 above pre-pandemic levels (Dec 2019 - Feb 2020), whilst self-employment has dropped by 751,000. The rise in the number of employees broadly matches the change in the real-time number of payroll employees using HMRC data, that show a rise of 235,000 over the same period. Interestingly, ONS data shows the rise in employees is entirely due to full-time work, as the number of part-time employees is still 388,000 below pre-pandemic levels.

Most of the decline in total employment has fed through to a rise in the number who are economically inactive rather than to unemployment. The number of unemployed is currently only 84,000 above pre-pandemic levels, whilst the number of inactive has risen by 364,000 (Figure 1.4). The number of individuals in economic inactivity due to being a student, long-term sick, retired and other has risen. It is uncertain how this rise in inactivity will play out over the coming years. Some of the rise may reflect a permanent change as workers chose to retire earlier than planned or pursue other activities as a result of the pandemic changing attitudes and behaviours. This will then reduce labour supply. It may also reflect the rise in people extending their studies, where it is reasonable to expect some will flow into the labour market when conditions are better. It is important to remember however that around one-fifth of the economically inactive (a pool of 1.7m individuals) report that they want a job. Firms with the right job offer may well be able to hire from this pool, though it may require more targeted recruitment. It is difficult to predict what the net impact on supply will be when combining early retirement and delayed access or return to the labour market for younger people.

Much of the reason for the more subdued labour market response to the large decline in GDP, compared to previous recessions, can be attributed to the policies the Government introduced in response to the crisis. The furlough scheme paid employers 80% of their employees’ wages if they could no longer work. The scheme had several changes throughout including allowing employees to be partially furloughed, as well as the amount the employer had to contribute. This is unlike any other policy implemented historically and was clearly successful in keeping individuals in employment. Figure 1.5 below shows the number of employees furloughed from March 2020 until August 2021.

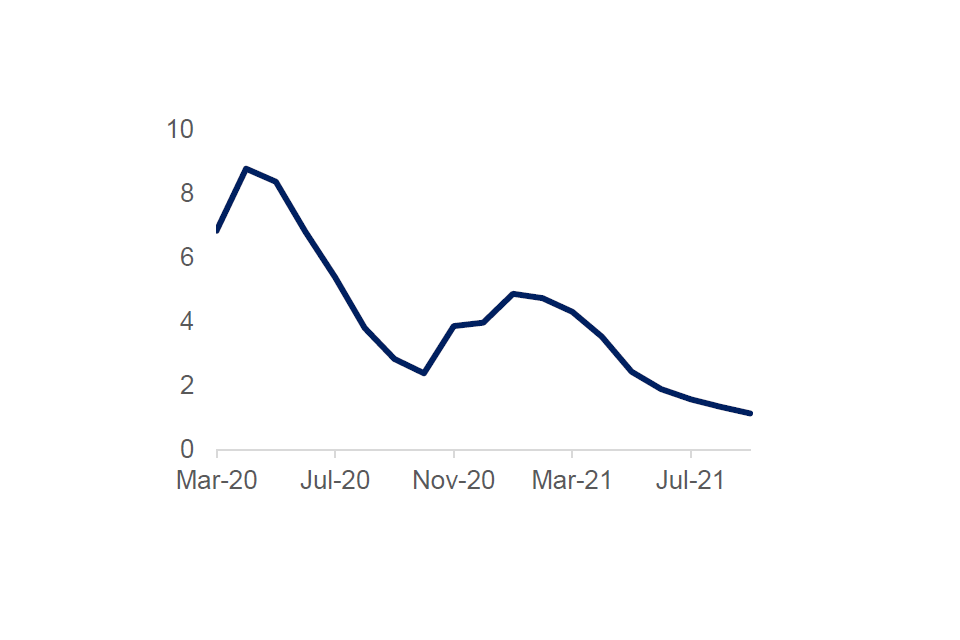

Figure 1.5: Number of employees furloughed (millions)

Source: Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme statistics, November 2021.

Note: Furlough statistics are published by the day, these represent the number of employees furloughed as at the end of every month (e.g. March 20 is 31/03/2020).

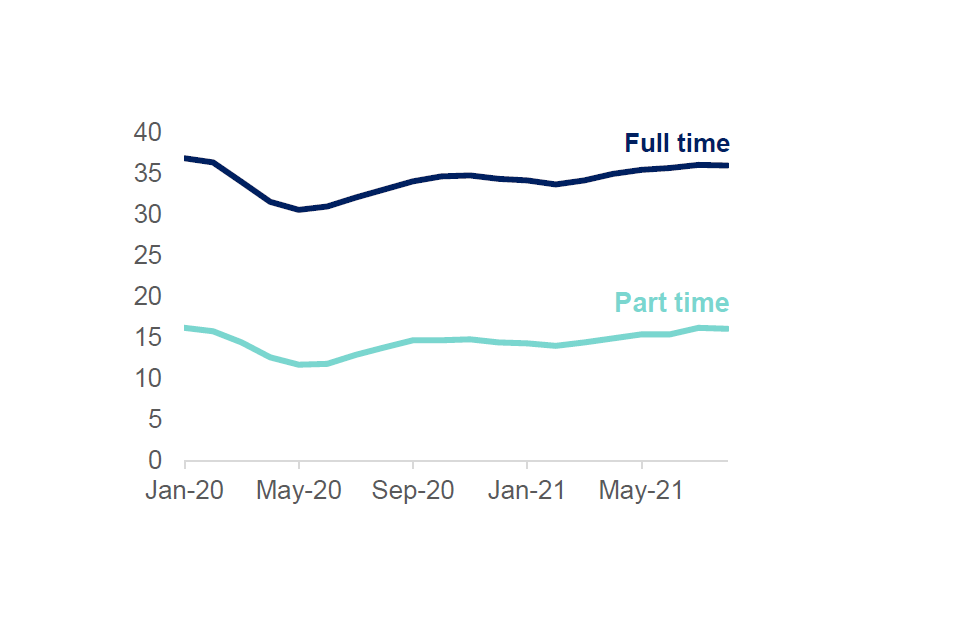

Figure 1.6: Average hours worked, January 2020 to June 2021

Source: ONS, Labour market statistics, November 2021.

As shown in figure 1.5, the furlough scheme supported many jobs, particularly during the nationwide lockdowns where many industries were forced to effectively close. The number of employees furloughed peaked at 8.9m in mid May 2020, which was over 30% of total employees. The introduction of this alongside other measures such as the Self-Employed Income Support (SEIS) scheme helped to reduce the negative impact of the pandemic on the labour market.

Whilst the impact on unemployment has been relatively muted, we can see the effect of the pandemic in the average number of hours worked in Figure 1.6. The average number of hours dipped to a low in May 2020 for both full and part time (30.6 and 11.7 hours respectively). Whilst hours have gradually risen since then, they were still slightly below pre-pandemic levels in June 2021, which is likely to be reflective of the ongoing furlough scheme which has only recently ended in September 2021.

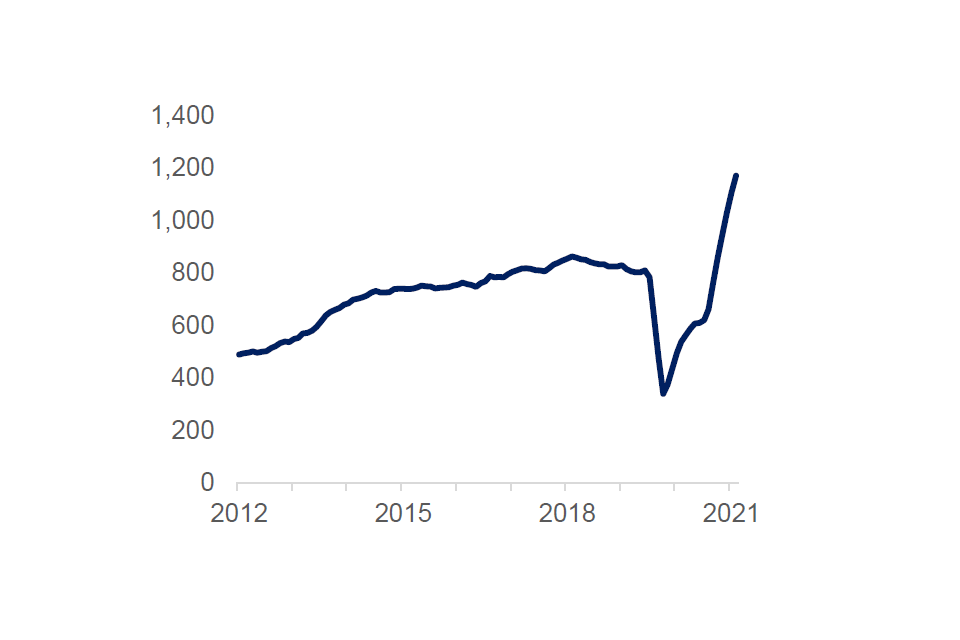

Vacancies

Figure 1.7 shows the total number of vacancies from August 2012 to October 2021. As the economy recovered from the financial crisis, vacancies rose significantly. As the pandemic hit and the first national restrictions were imposed, vacancies fell to a low of 340,000, the lowest number observed since the ONS Vacancy Survey began in 2001. As the pandemic eased and restrictions were relaxed, vacancies rapidly rebounded, and by October 2021 there were almost 1.2m vacancies, the highest on record.

Figure 1.7: Vacancies July 2012 – October 2021 (thousands)

Source: ONS Vacancy Survey, 2012 – 2021.

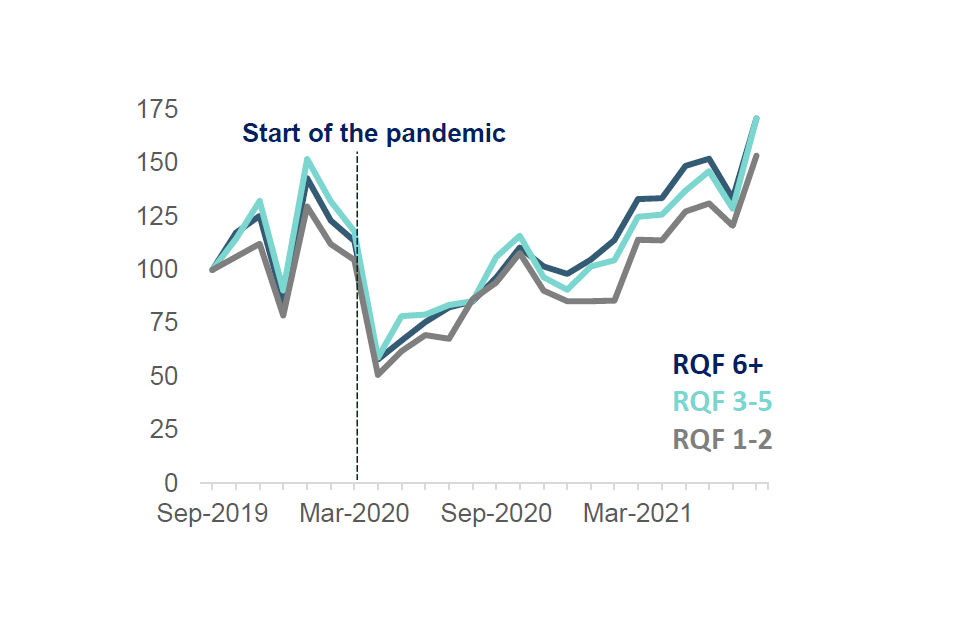

Figure 1.8: Index of job vacancies by qualification level required, monthly (Index 100 = September 2019)

Source: Labourinsight Burning Glass, 2019 – 2021.

Some occupations were impacted more than others as a result of the pandemic, with jobs requiring different skill levels affected differently. Figure 1.8 shows the change in vacancies by RQF skill level required for the job advertised.

Across all skill levels in Figure 1.8, vacancies dropped by 50% from March to April 2020, and there were no particularly noticeable differences across skill levels. Vacancies in all skill levels followed the same initial pattern of recovery but fell again when restrictions were reimposed in November 2020. Vacancy levels for RQF 1-2 jobs stagnated between December 2020 and February 2021. In the same period, vacancies in RQF 3-5 and RQF 6+ jobs increased by 15% and 16% respectively, showing that they had started to recover before RQF 1-2 job vacancies did.

Sector focus

The COVID-19 pandemic and the restrictions introduced as a result had a different impact across sectors within the economy. Sectors such as hospitality and retail faced closure or limited opening rules when restrictions were in place. This section will focus on exploring this differential impact and the recovery in these labour markets.

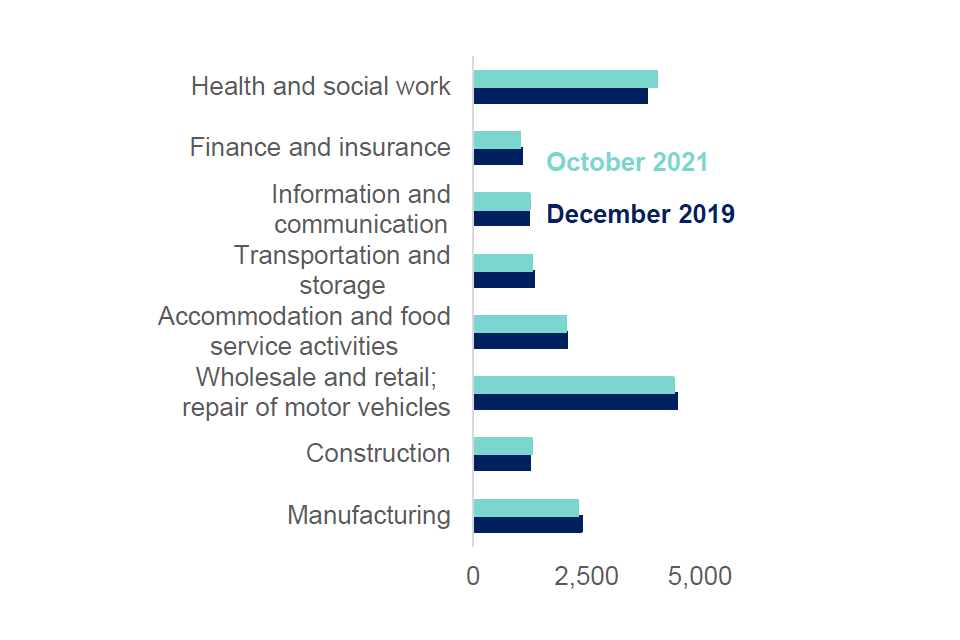

Figure 1.9 shows the levels of employment for certain industries in December 2019 and October 2021. This shows that these selected industries have broadly recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 1.9: Number of payroll employees by industry (thousands), December 2019 to October 2021

Source: Employees by industry (SIC07), Pay As You Earn Real Time Information, November 2021. Seasonally adjusted.

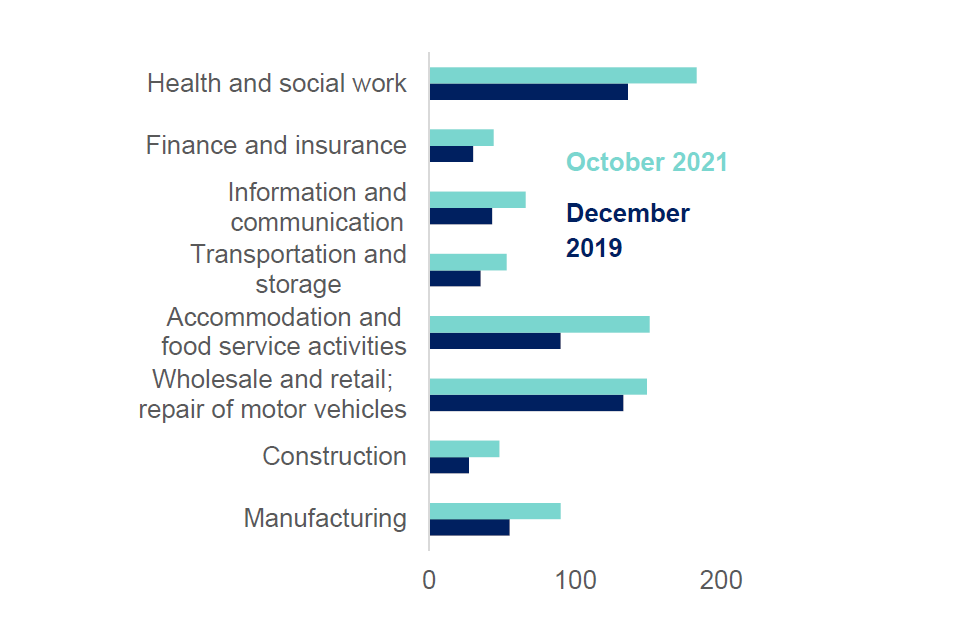

Figure 1.10: Number of job vacancies by selected industry, December-February 2020 and August-October 2021 (thousands)

Source: ONS Vacancy Survey, November 2021, table VACS02.

Figure 1.10 shows the number of vacancies in the same selection of industries. All the industries shown have a higher number of vacancies now compared to pre-restrictions. Vacancies are over 50% higher now than pre-pandemic in manufacturing, construction, information and communication, accommodation and food service activities, and transportation and storage. This aligns with the trend seen in Figure 1.7, with a sharp recovery in vacancy numbers in recent months.

Geographical impact

The COVID-19 pandemic also produced different impacts across the nations and regions of the UK. Some of this was a result of regional restrictions introduced in the latter half of 2020 which saw different regions experience different levels of closures. Regions have also experienced different levels of recovery, with cities and urban areas more heavily impacted by the shift to working from home.

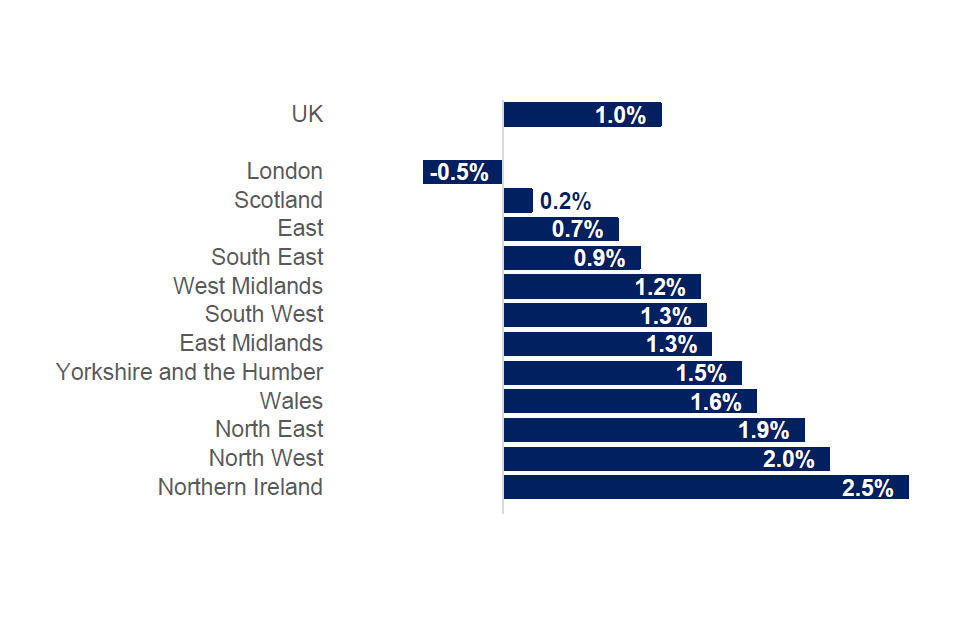

Figure 1.11: Change in levels of employment by region, December 2019 to October 2021

Source: Pay As You Earn Real Time Information, seasonally adjusted, November 2021.

Figure 1.11 focuses on the change in levels of employment from pre-pandemic to October 2021, highlighting the differential impact across regions. The UK as a whole experienced a rise in levels of employment compared to pre-pandemic level. London was the only region to see a fall compared to pre-pandemic levels potentially reflecting the impact on cities described above. Whilst the South East, East, and Scotland saw a rise in levels, this was lower than the UK.

Summary

Overall, we have seen significant impacts on the labour market as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Policies introduced such as the furlough scheme helped to protect jobs and employment fell less (and unemployment rose less) than would have been expected given the size of the economic shock. The furlough scheme has now closed, and early indications suggest that this has had no substantial impact on unemployment, though this will become clearer in the December publication of the ONS Labour Market Overview. The rise in inactivity may partly be a short-term response to the pandemic but may also reflect longer run changes in attitudes to work. Vacancies have rebounded sharply in the last few months across all skill levels and employers are reporting increasing difficulty in filling these vacancies.

The new immigration system

At the end of 2020, the UK’s immigration system saw a substantial change. The new Points Based System (PBS) was introduced in December 2020, alongside the ending of freedom of movement for EEA nationals at the start of 2021. The new Skilled Worker (SW) route replaced the Tier 2 General (T2(G)) route as the main route for skilled work into the UK. SW applicants must have a job offer with a salary of at least £25,600 or the going rate for the occupation, although there are lower salary rates for shortage occupations, people with PhDs, and new entrants to the labour market.

Under this route the range of jobs that can be filled by migrants on a skilled work visa has expanded to include those at RQF 3-5 (at or above A-level, NVQ3 or equivalent), reducing the threshold from RQF 6+ (Degree level or equivalent and above). The general salary threshold was also reduced from £30,000 to £25,600, in line with MAC recommendations (PDF, 3.5 MB), to reflect the broader group (RQF 3-5) who are now eligible occupations for this route. Lower thresholds may be in place if the occupation is listed on the Shortage Occupation List (SOL), the individual has a PhD, or if the occupation is based on national pay scales but can in no circumstance be less than £20,480.

This section of the report will focus on the use of the new system, including the use of the SW route, particularly focusing on usage by EEA nationals and uptake by those from non-EEA countries working in occupations at RQF 3-5 who were previously ineligible for the route.

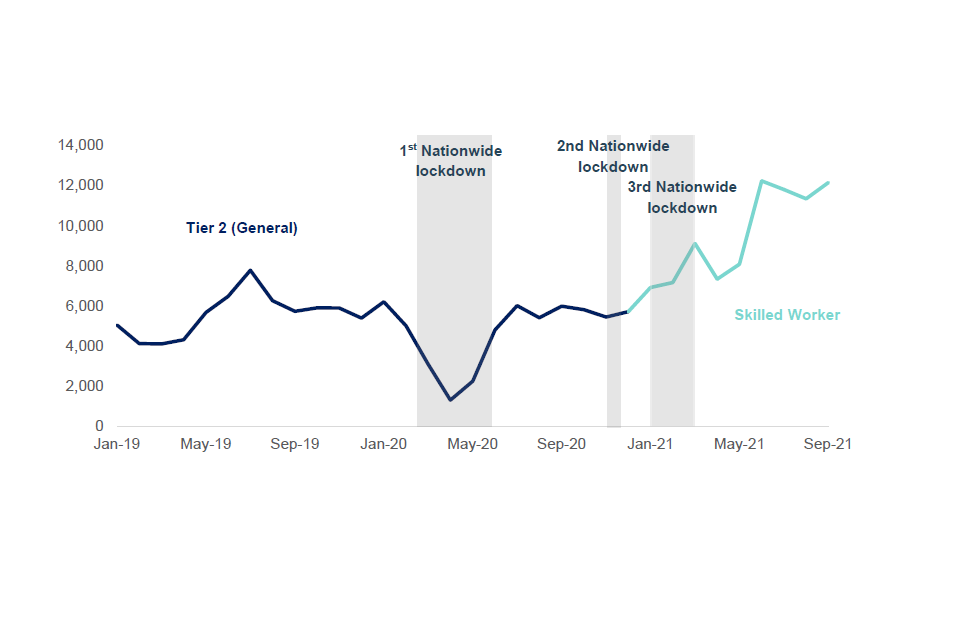

Use of the new system

Figure 1.12 shows the number of visa applications for the T2(G) and SW route from January 2019 to September 2021. Given the uncertainty around the COVID-19 pandemic we had in our Annual Report 2020 (PDF, 2MB) anticipated limited use of the new SW route in at least the first half of 2021. It is difficult to isolate the separate impact of COVID-19 and the introduction of the new immigration system in the data presented in Figure 1.12, as both occurred at a similar time.

There was a clear decline in the number of applications during the first national lockdown as a result of the pandemic making cross border movements more difficult and the temporary closure of the UK Visa Application Centres (UK VACs) making it difficult for individuals to apply for visas to enter the UK. Visa processing times were also impacted by decision makers needing to access office locations to complete processing. By contrast, subsequent lockdowns appear to have had very little effect on visa applications for the work route, and in fact in the first three months of 2021 the number of visa applications was over 70% higher than that seen in the first three months of 2019.

Figure 1.12: Total visa applications for T2(G) and SW route, January 2019 to September 2021

Source: Home Office Management information, Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2019 to 30 Sept 2021.

Note: Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application.

Figure 1.12 shows a substantial rise in applications in the months following the ending of the third national lockdown, with monthly applications rising by over 50% between May and June 2021. Part of this rise may well have been the result of pent-up demand for visas, but the number of applications continues to be higher than levels seen in 2019, consistent with the tighter labour market we have described. It will be important to monitor further usage of the route to understand long term migration trends.

During discussions with stakeholders, many have praised the operation of the new immigration system and have found it more user-friendly and efficient than the previous system. It should be noted that these stakeholders would have been familiar with the previous system, so may not be representative of the experience of SMEs and others who may not have previously had any significant interaction with the work visa system. Whilst the lower levels of applications during the pandemic may have helped to smooth out the move to the new system, it is also difficult to launch a new system during a pandemic and the Home Office deserves credit that the move to the new system appears to have been operationally successful.

Who is using it?

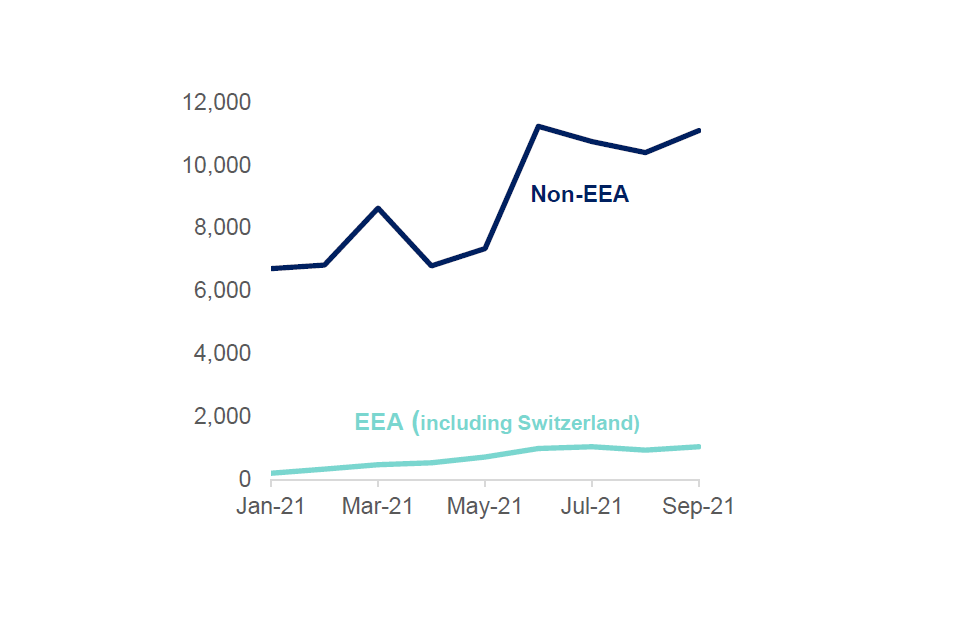

After decades of free movement, from January 2021 EEA nationals wanting to work in the UK must apply to the SW route, alongside migrants from all other nationalities. As a result, the data on the two visa routes are not directly comparable, as the SW route data includes EEA nationals whilst T2(G) did not. Figure 1.13 shows the usage of the SW route by these groups between January 2021 and September 2021.

Figure 1.13: Total SW route visa applications January 2021 to September 2021, split by EEA and Non-EEA nationality

Source: Home Office Management information, Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2021 to 30 Sept 2021.

Note: Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application.

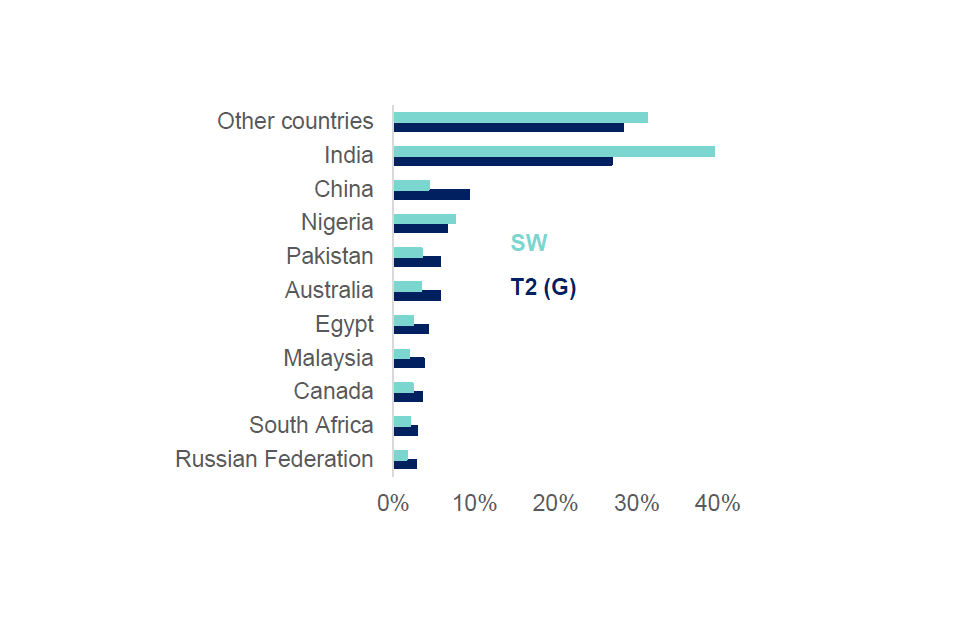

Figure 1.14: SW and T2(G) applications by migrant nationality, Non-EEA only

Source: Home Office Management information, Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2019 to 30 Sept 2021.

Note: T2(G) is for 01 January 2019 – 30 November 2020. SW is 01 December 2020 – 30 September 2021. Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application.

Figure 1.13 shows that the recovery in visa applications during 2021 was primarily driven by non-EEA nationals, as there is relatively low usage from EEA nationals compared to the rest of the world. EEA nationals made up only 8% of applications over this period. Figure 1.14 suggests that some countries have experienced a small decline in the number of applications while there has been a substantial rise in the share of work visas issued to Indian nationals.

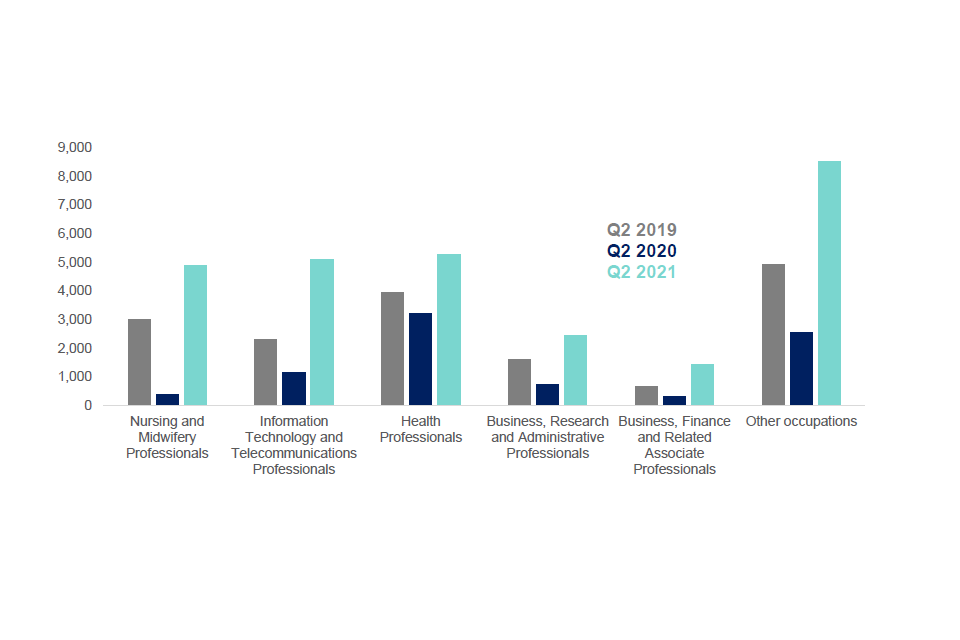

As with the previous T2(G) route, the SW route requires employers to sponsor employees ahead of them applying for their visa. Certain occupations where there is increased demand for labour may be driving changes in the number of applications. The UK saw a large increase in applications in the second quarter of 2021, with the number of visa applications 68% higher than in the same quarter in 2019. Approximately 17% of this increase was due to the rise in applications for those entering nursing and midwifery professionals’ occupations. The top five occupations in terms of absolute increases seen in the number of visa applications between 2020 and 2021 are shown in Figure 1.15 below.

Figure 1.15: Number of visa applications by occupation, for top five in terms of absolute increases between 2020 and 2021, Q2 2019, Q2 2020 and Q2 2021

Source: Home Office Management information, Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data Q2 2019, Q2 2020 and Q2 2021.

Note: Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application.

Of the total number of visa applications in the second quarter of 2021, almost 70% were for jobs in these five occupations. Figure 1.15 shows the large increases seen in the number of visa applications across these occupations. The substantial rise seen in the number of visa applications for Nursing and Midwifery professionals and health professionals may reflect some of the shortages seen in the sector throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Migration Observatory analysis shows that this is also a longer-term trend with IT and health being the two largest industry users of the skilled work visas.

Whilst there are a number of factors at play, which may have driven the rises we see in the number of visa applications in the second quarter of 2021, it is likely to be a combination of the reopening of the economy and certain occupations seeking an increased number of people to work.

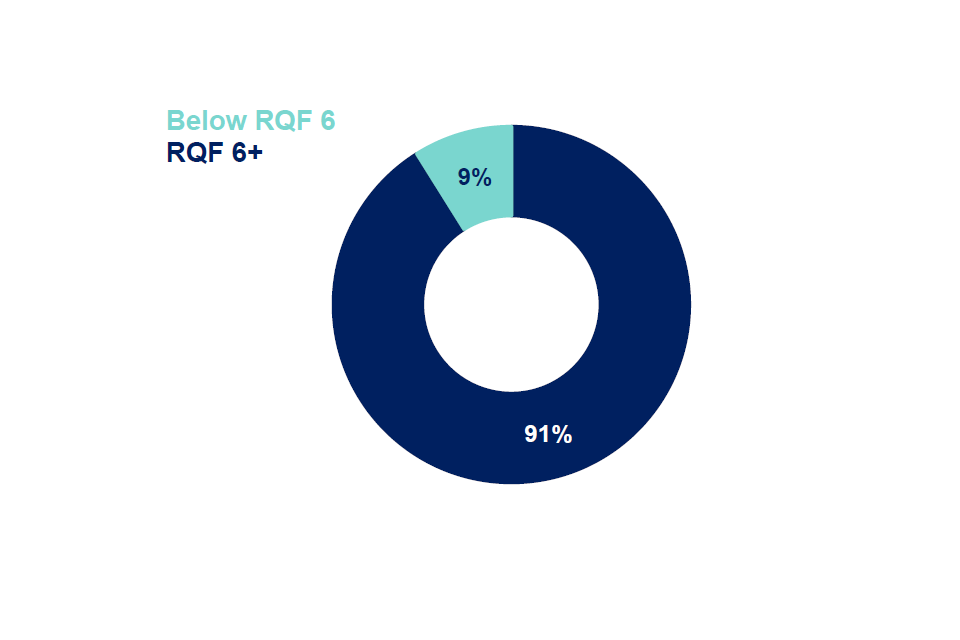

RQF 3-5 occupations

Employers can now sponsor employees for roles that are RQF 3-5 (at or above A-level, NVQ3 and equivalent) under the SW route. Figure 1.16 shows that so far in 2021 we have seen little use of the route for these expanded occupations, with over 90% of applications being for roles at RQF 6+. Breaking the data by nationality shows no significant difference, with EEA and non-EEA nationals applying for RQF 6+in 86% and 91% of applications respectively. Of the 5,200 applications for roles in RQF 3-5 occupations over a third were for senior care workers. The rate of applications for senior care workers has risen over the course of the year and is currently around 400 – 500 per month.

Figure 1.16: Proportion of visa applications by RQF level

Source: Home Office Management information, Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2021 to 30 Sept 2021.

Note: Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application.

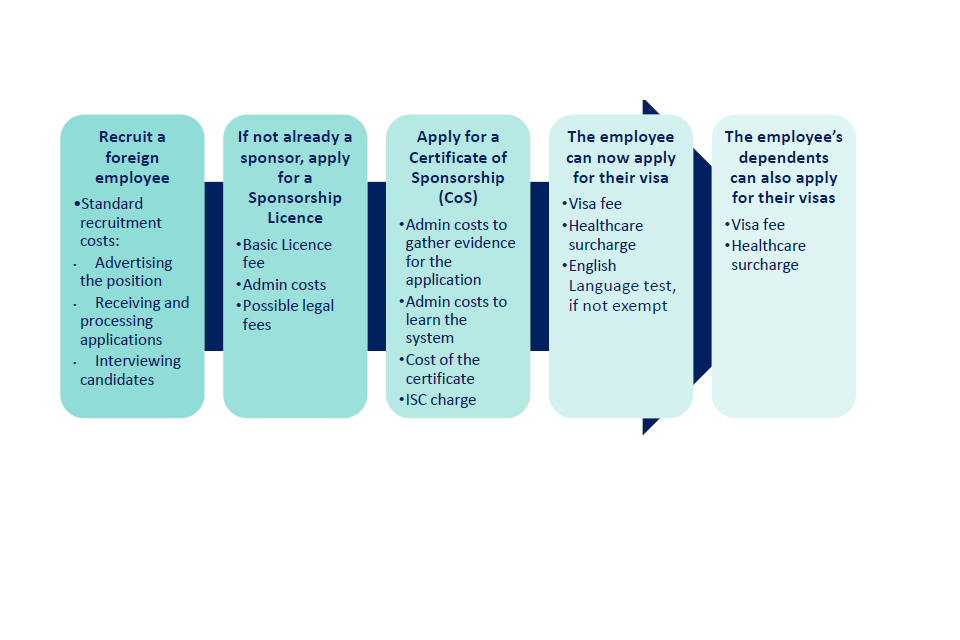

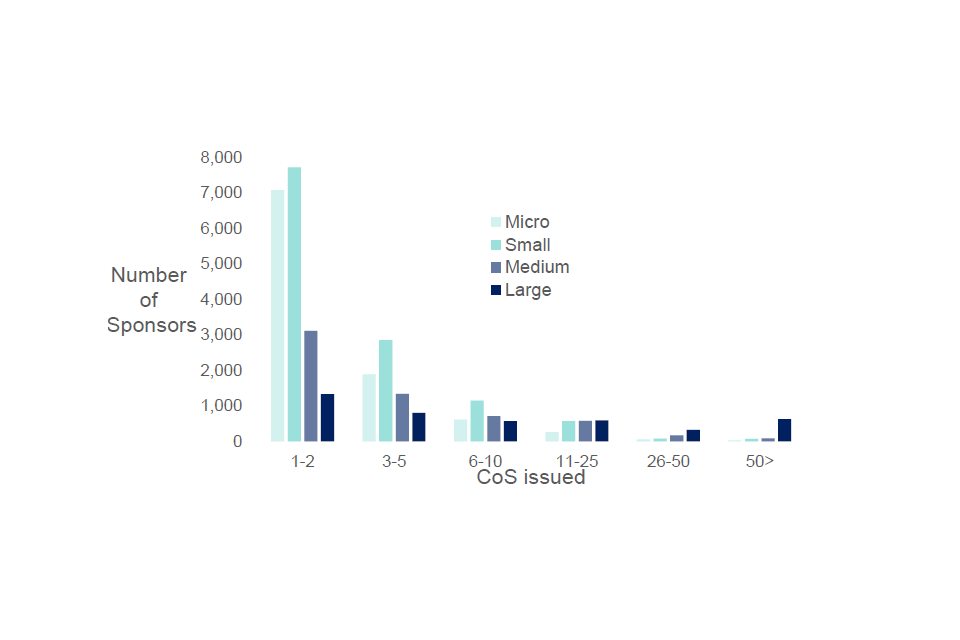

In our Annual Report 2020 (PDF, 2MB), we discussed the costs for employers in hiring a worker from abroad and anticipated that many would conclude that it is not feasible to use the new SW route for hiring RQF 3-5 workers as a result of these associated costs. The low usage of the route for occupations below RQF 6 in 2021 so far supports this hypothesis. Chapter four of this report will cover the costs of using the immigration system in more detail and shows that the costs of using the immigration system are proportionately much larger for lower paying jobs and also comparatively higher than other countries which might make the UK less competitive when attracting skilled workers.

More generally, we might expect a heavier usage of the SW route for RQF 6+ jobs compared to RQF 3-5. Such jobs tend to be filled by more internationally mobile staff and many such occupations compete globally for talent. This is less common in RQF 3-5 jobs. In addition, the training time required to become competent in an RQF 3-5 job is generally significantly lower than at RQF 6+ level, so some employers may find it easier to recruit and train UK workers for vacancies even if there is a skill shortage.

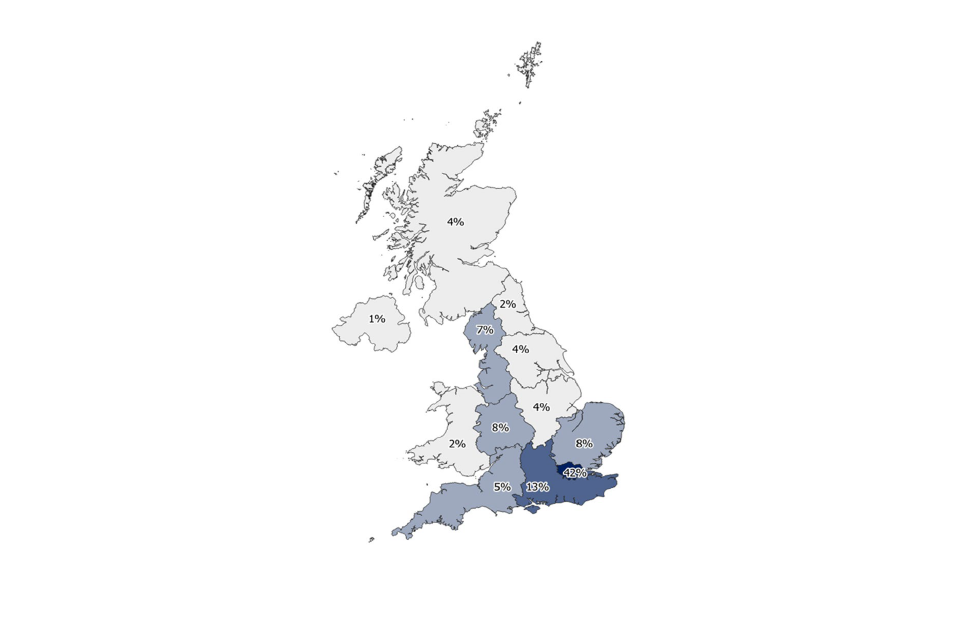

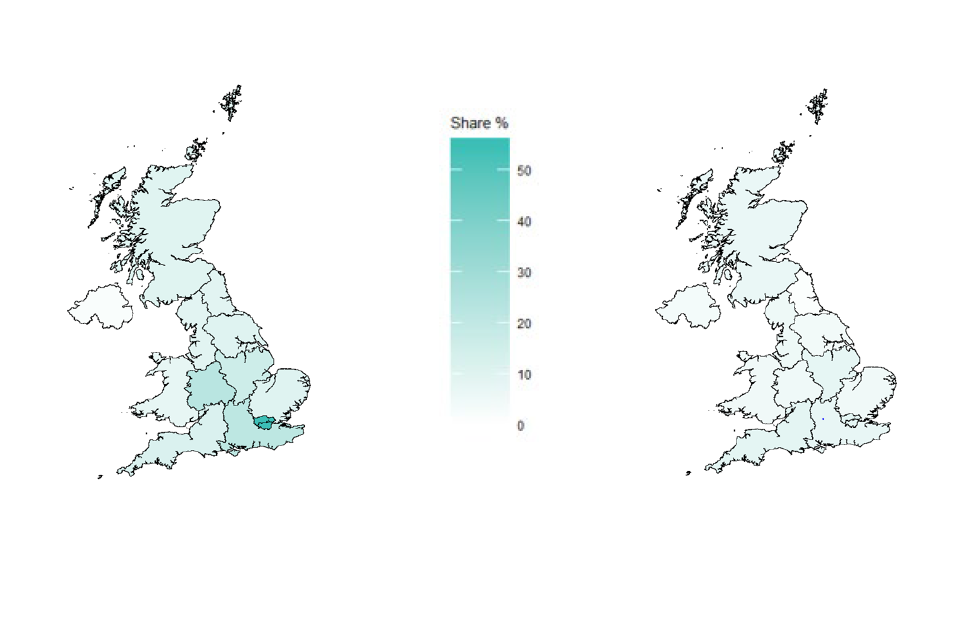

Regional Focus

Figure 1.17 shows that the highest share of SW applications in 2021 are in London, which accounts for 42% of the total visas in 2021. This may be reflective of the occupation skill mix, with London having a higher share of RQF 6+ occupations. It may also be a result of the salary threshold being relatively cheaper for London based companies, where wages tend to be higher. The MAC intend to look into the regional use of the immigration system in more detail in future.

Figure 1.17: Applications by Government office region, 2021

Source: Home Office Management information, Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2021 to 30 Sept 2021.

Note: Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application. This refers to region of workplace, this might differ to the region the migrant lives in.

Shortage Occupation List (SOL)

The SOL contains those occupations, amongst those eligible for the SW route, which are judged to be in ‘shortage’ i.e. where employers find it difficult to secure adequate numbers of workers with the required skills to fill their vacancies, and where we judge migration is a sensible response to that shortage. Decisions on which occupations to include on the SOL are made by Ministers following recommendations from the MAC. These occupations are then subject to different, more favourable, migration arrangements, enabling employers to access a wider pool of suitable workers, at a lower threshold of £20,480 or 80% of the going rate, whichever is higher. This lower threshold is the primary advantage of an occupation being listed on the SOL in the SW route.

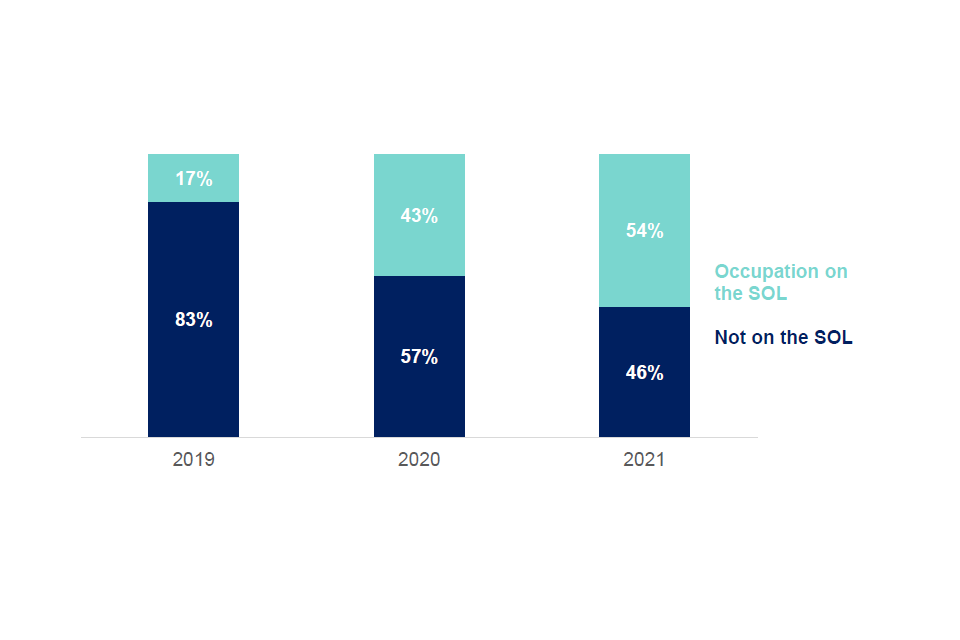

Figure 1.18 shows that 54% of visa applications in the first nine months of 2021 were for occupations that are listed on the SOL. This is an increase to that seen in 2020 (43%), and a significant rise on the 17% in 2019. This figure may suggest a significant effect of the COVID-19 pandemic, since SOL visa applications increased substantially before the new immigration system was in place. With travel restrictions in place and significant uncertainty in the economy some employers may have chosen to pause recruitment from abroad, whereas those recruiting for occupations on the SOL may have continued as they are in ‘shortage’. It might also be reflective of the larger list of occupations now listed on the SOL. It will be interesting to monitor this trend to see if it continues in future years, to determine whether this is an effect of the pandemic or not, given the rise in healthcare occupations seen.

Figure 1.18: Breakdown of Visa applications by SOL and non-SOL, 2019-2021

Source: Home Office Management information, Certificate of Sponsorship (CoS) data 01 Jan 2019 to 30 Sept 2021. 2021 is not the fully year and only includes applications up to the end of September.

Note: Used CoS. CoS is assigned to a migrant by their sponsoring employer and the migrant can then use the certificate number to make a visa application.

Table 1.19: SOL occupations that can pay below the going-rate threshold

| Occupation | 25th percentile | SOL threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Health services and public health managers and directors | £38,400 | £30,720 |

| Physical scientists | £36,500 | £29,200 |

| Civil engineers | £35,000 | £28,000 |

| Mechanical engineers | £33,400 | £26,720 |

| Electrical engineers | £37,000 | £29,600 |

| Electronics engineers | £34,700 | £27,760 |

| Design and development engineers | £34,100 | £27,280 |

| Production and process engineers | £33,100 | £26,480 |

| Engineering professionals n.e.c. | £32,700 | £26,160 |

| IT business analysts, architects and systems designers | £36,600 | £29,280 |

| Programmers and software development professionals | £33,300 | £26,640 |

| Veterinarians | £32,500 | £26,000 |

| Actuaries, economists and statisticians | £32,800 | £26,240 |

| Architects | £35,000 | £28,000 |

Source: Skilled Worker visa: shortage occupations.

Note: This excludes health and education occupations listed on the SOL on national payscales.

As mentioned previously, the primary advantage of an occupation being listed on the SOL is the lower salary threshold. Table 1.19 shows the occupations that are listed on the SOL and are able to pay below the going rate.

The MAC has never supported lowering the salary threshold below the ‘going rate’ for an occupation. If there is a shortage in the occupation, it seems perverse that paying lower wages will address the issue. Furthermore, the ‘going rate’ thresholds are in place to prevent undercutting of resident workers and being placed on the SOL should not enable employers to avoid this constraint. In practice, few employers are using this advantage, with only 15% of applications for these select SOL occupations in the first nine months of 2021 paying below the ‘going rate’. The evidence that few are taking advantage of this suggests it is not helpful for employers either, and we would therefore recommend that the Government reconsider whether SOL occupations should be allowed to pay below the ‘going rate’ for the occupation.

In contrast, the MAC are more supportive of a lower salary threshold for lower paid occupations on the SOL, which are generally RQF 3-5 jobs, where this will not lead to undercutting. For example, senior care workers would face a salary threshold of £25,600 (the general threshold) if they were not on the SOL. This is above the 75th percentile of the wage distribution for this occupation, making it an unrealistic route for most such jobs. The 20% discount on the general threshold that being on the SOL allows, reduces the threshold to £20,480. This is still comfortably above the ‘going rate’ for this occupation (£16,900), reducing any concerns over undercutting. The MAC would suggest that any salary threshold advantage to being on the SOL should be limited to those occupations where such a reduction does not go below the ‘going rate’ for that occupation.

RQF 1-2 occupations

As detailed in the new immigration section, the ending of freedom of movement for EEA migrants at the start of 2021 was a substantial change. Previously EEA migrants were not restricted in terms of which occupations they could migrate to the UK to work in. Now, new EEA migrants arriving in the UK on a work visa are no longer able to apply for RQF 1-2 (below A-level, NVQ3 or equivalent) occupations, though those arriving as dependents may work in these roles.

Prior to the ending of freedom of movement almost half of EEA nationals worked in RQF 1-2 occupations. In our Annual Report 2020 (PDF, 2MB), we discussed how this change could result in a tighter labour market for such jobs in the UK. However, this was expected to depend on the COVID-19 pandemic and unemployment levels at the time. This section will provide an update on this and cover some of the temporary visa routes the Government have implemented where there have been issues in the labour market for these occupations.

Labour market for RQF 1-2 jobs

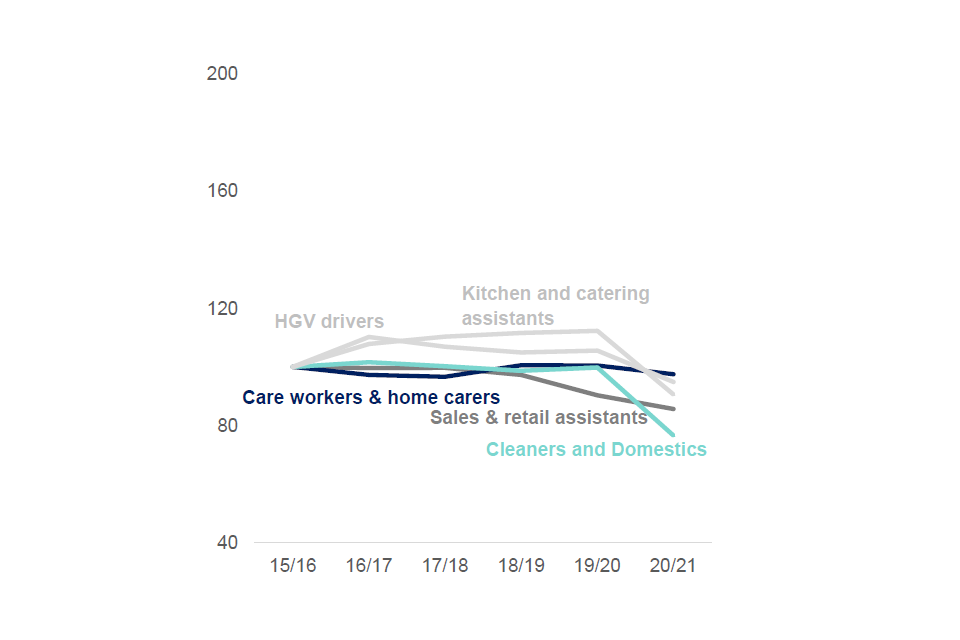

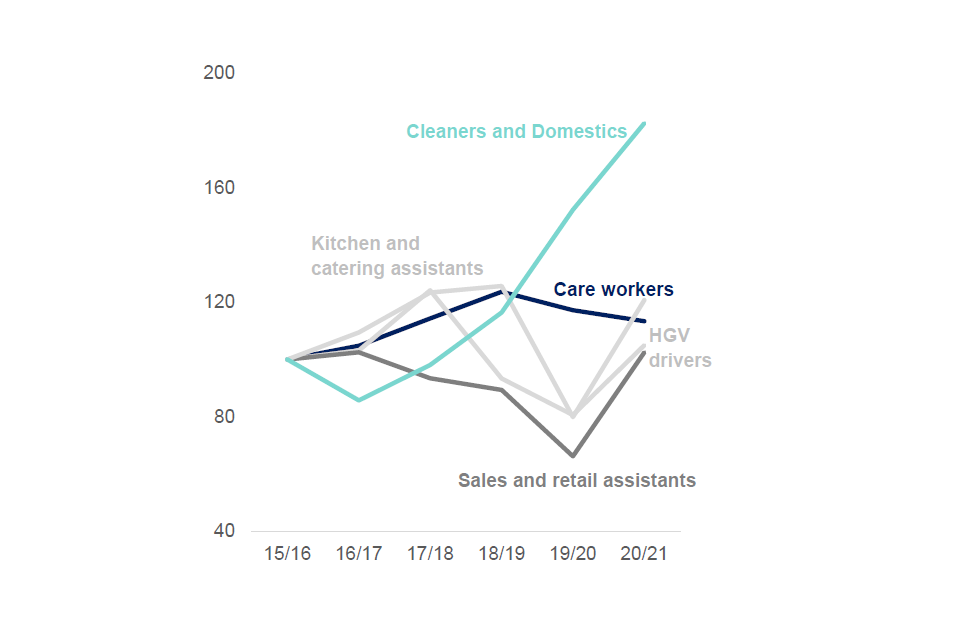

Figure 1.20: Level of employment in selected RQF 1-2 occupations (Index 100 = 2015/16)

Source: Annual population survey, April – March.

Figure 1.21: Level of vacancies in selected RQF 1-2 occupations, (Index 100 = 2015/16)

Source : Skills for Care (Care workers), LabourInsight Burning Glass (all others).

Note : For LabourInsight Burning Glass, Years are start of October to end of September, e.g. 1st October 2012 to 30 September 2013 is 2012/13. For Skills for Care data, years are from April to March.

Figure 1.20 shows the indexed level of employment in selected RQF 1-2 occupations. Since 2015/16, employment has remained relatively stable across occupations, however sales and retail assistants and Cleaners and domestics faced a fall in the levels of employment in 20/21. However, this data does not capture the rebound in employment after the ending of the third lockdown. Figure 1.21 shows the number of vacancies in the same selected RQF 1-2 occupations. Across all the selected occupations we see a rise in vacancies between 2019/20 and 2020/21, except for care workers. More recent data for care workers and latest vacancy rates is shown in the social care section; Figure 1.21 does not reflect a rise in vacancy rates in the sector that has been observed since the end of March 2021.

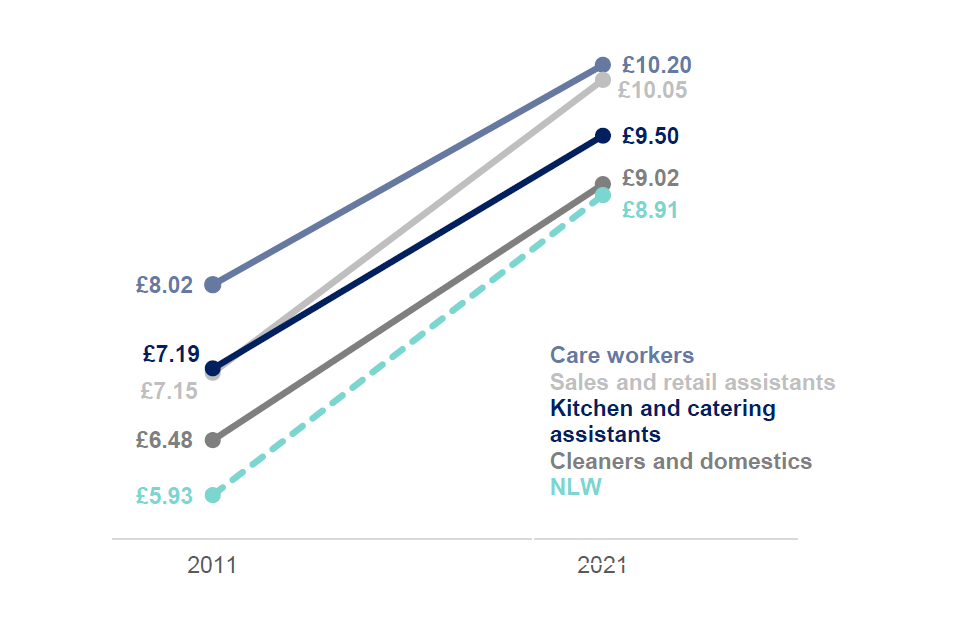

Figure 1.22: Median gross hourly pay (nominal) 2015, 2019 and 2021

Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), Table 15.5a Gross hourly pay, 2015 (r), 2019 (r) and 2021 (p). National minimum wage and living wage rates.

Figure 1.22 shows the median nominal gross hourly pay for selected RQF 1-2 occupations in 2015, 2019 and 2021. Between 2015 and 2019 the National Minimum Wage (NMW) increased by 15% for those aged over 21. Some of the selected occupations median hourly pay grew faster than this: sales and retail assistants (23%), cleaners and domestics (22%) and kitchen and catering assistants (23%). These occupations had slightly lower median hourly pay than large goods vehicle drivers (£10.69) and customer service occupations (£9.98) and were therefore likely to be more affected by changes in the minimum wage.

RQF 1-2 occupations and EU exit

Table 1.23 shows the proportion of RQF 1-2 workers by nationality. Both at the time of the Brexit referendum and at the beginning of the pandemic around 9% of RQF 1-2 workers were EEA nationals. To put this into context EEA nationals account for 7% of the UK workers across all occupations, so they are somewhat over-represented in these occupations. More substantial changes in the proportions of EEA workers may be expected going forward as we see the impact of a decreasing flow of EEA nationals into the UK.

Table 1.23: Proportion of RQF 1-2 occupations by nationality

| Nationality | 15/16 | 19/20 |

|---|---|---|

| EEA | 8% | 9% |

| Non-EEA | 4% | 4% |

| UK nationals | 88% | 86% |

Source: ONS, Annual Population Survey.

Note: 2015/16 is April 15 to March 16, 2019/20 is April 19 to March 20. Occupations are based on 4-digit SOC codes.

Table 1.24: Job skill mix by sector and the proportion filled by migrants in RQF 1-2 jobs, 2019/20

| Proportion of RQF 1-2 occupations in sector | Proportion of migrants in RQF 1-2 occupations in sector | |

|---|---|---|

| Accommodation and Hospitality | 63% | 23% |

| Agriculture | 29% | 7% |

| Manufacture of Foods and Beverages | 57% | 31% |

| Residential and Social Care | 44% | 19% |

| Transport | 73% | 21% |

| Warehousing | 64% | 30% |

| Wholesale and Retail Trade | 57% | 13% |

Source: ONS, Annual Population Survey (APS). April 19 to March 20.

Note: APS does not capture seasonal workers so will only cover permanent employees in Agriculture.

Table 1.24 shows the proportion of migrants in RQF 1-2 jobs in these sectors prior to the pandemic, and highlights some of the sectors that may be particularly affected with the new immigration system. A large share of the RQF 1-2 jobs are held by migrants in the manufacture of foods and beverages (31%) and warehousing industry (30%).

Temporary visas

The Government has recently introduced several temporary visas to provide routes for migrants to fill mainly RQF 1-2 occupations. For example, temporary visa routes were set up for 5,000 Heavy Goods Vehicle (HGV) drivers and 5,500 poultry workers to come to the UK in the period up to Christmas to avoid potential further pressure on the food industry and supply chains. These temporary visa routes for HGV drivers (see box below), butchers and poultry workers have been put in place using the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS). This is a pilot scheme which began in 2019.

Historically the MAC has cautioned against sector-specific schemes that all too often benefit sectors that shout the loudest or have the most effective lobbying strategy. At the same time, we recognise that problems in some sectors can have substantial knock-on effects to the wider economy that need to be considered. There is no perfect solution here. On the one hand, offering visas to a wider range of occupations that require shorter training may disincentivise firms’ investment in innovating production and increasing automation. Our previous report (PDF, 2.2 MB) found there is also some evidence that suggests lower-skilled workers face a negative wage impact from migration, though the magnitude of the impact is generally estimated to be small. On the other hand, a rigid rejection of all visa options in occupations that require shorter training periods risks causing permanent damage to sectors that need time to adjust following the pandemic. The MAC is broadly supportive of the approach taken by the Government to resist wide scale changes to the immigration system, though we have some concerns over the design of the temporary routes that we discuss below.

There is a distinction between SAWS and the Skilled Worker (SW) route. The former was designed explicitly for seasonal work in agriculture where the nature of the job tends to make it unattractive to domestic workers, both because it is non-permanent and often located in more remote rural areas. Many countries operate an equivalent of the SAWS scheme. The SAWS does not have an English language requirement, does not in general have minimum salary thresholds and time spent on the route does not count toward settlement. In contrast, the SW route is designed for longer-term work in the UK and is a route to settlement. The SW route imposes an English language requirement and has a set of salary thresholds to prevent undercutting of domestic workers.

The English language requirement is beneficial for society, as it enhances the ability of migrants to integrate successfully when coming to the UK. Importantly it also helps to protect migrants from exploitation as they are more able to voice their concerns and would also find it easier to move to another job if they have good fluency in English. The MAC recommended English language proficiency as an essential requirement for the SW route. This is primarily because this is a route to settlement and English language provides long-term integration benefits. For the SAWS we are more concerned about exploitation, particularly for lower paid workers who are more likely to be exploited. A 2017 report (PDF, 693 KB) from the Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority noted that a lack of language skills, amongst other circumstances such as a lack of representation, can lead to labour exploitation. Immigration must not be thought of as something that should only be focused on benefiting firms – the rights of migrants must also be considered.

Whilst these temporary routes may have value in the short-term, they come with a number of issues including uncertainty for employers and should not come to be seen as a long-term solution. We are also not convinced that the approach of using last minute, very short-term fixes should become the norm, since it reduces employers’ ability to plan and is in any case unlikely to generate the flows of migrant workers sought. If the government is willing to offer concessions to specific industries, it would likely make more sense to establish a migration route with clear conditions attached and a transparent method to decide when specific industries or occupations would be eligible to use this. This would surely be preferable to using the SAWS for purposes well outside its design. In terms of the SAWS scheme that began in 2019, the Government is yet to publish the evaluation of the scheme, despite stating in Parliament in October that this would be published shortly. Publishing an evaluation of the pilot scheme is central to completing the pilot to demonstrate its effectiveness and discuss whether changes are needed. We would welcome the findings of their evaluation to help inform our view on the SAWS scheme.

We have a heightened concern about butchers being allowed to use the SAWS route on a temporary basis. This occupation is eligible for the SW route, so migrants could enter the UK to work under this route. Employers may find the SAWS route beneficial over the SW route for a number of reasons. We know from research with employers in other occupations, and using other immigration routes, that the lack of an English language requirement is often viewed favourably, because of the saving in administrative burden and time this confers. If this is the case then as discussed, our view is that the requirement for English language proficiency is a measure to protect migrants, even if it makes some ineligible. There are concerns that migrants could be exploited via this route. It is possible that those entering on the SAWS may learn English in the UK, and then apply for the long-term route to settlement through the SW route. Furthermore, we recognised that butchers were in shortage in our last SOL review, where we recommended that the occupation was added to the SOL. However, the Government decided not to implement this recommendation at the time, and it may be that a more sensible approach to the recent difficulties would have been to implement this recommendation.

Stakeholder evidence in the 2020 SOL review highlighted issues with adverse working conditions and limited training/skills for butchery amongst the domestic workforce. These are longstanding issues which were also raised in the 2008 SOL review, and employers we spoke to in food manufacturing (particularly in shellfish and meat processing) as part of our recent qualitative research with employers (publication of which is forthcoming) again reiterated these concerns, despite efforts made to attract and retain the domestic workforce. For example, we spoke to a representative in the food processing sector who told us that the average British worker recruited stayed in post for 24 days before leaving, compared to the average Lithuanian worker staying 176 days, and the average Polish worker 288 days, before leaving.

It is possible that some employers could do more to attract and retain British workers, particularly among those who have not traditionally worked in the occupation. For example, as part of the qualitative research mentioned above, we spoke to one employer who had redesigned the nature of some of their butchery work to make it more easily done by women and was planning to offer part-time working; in contrast, another processor had recently stopped offering school hours shifts and part-time work despite difficulty recruiting. Employers who are able to offer conditions that suit the greatest number of people are likely to be those who find it easiest to recruit staff.

Box: HGV drivers

In Autumn 2021 the UK experienced a breakdown in many of its supply chains, particularly those involving the transport of food and fuel. Many in the industries affected said that a lack of HGV drivers available to transport goods had caused this and called for government intervention to prevent further damage.

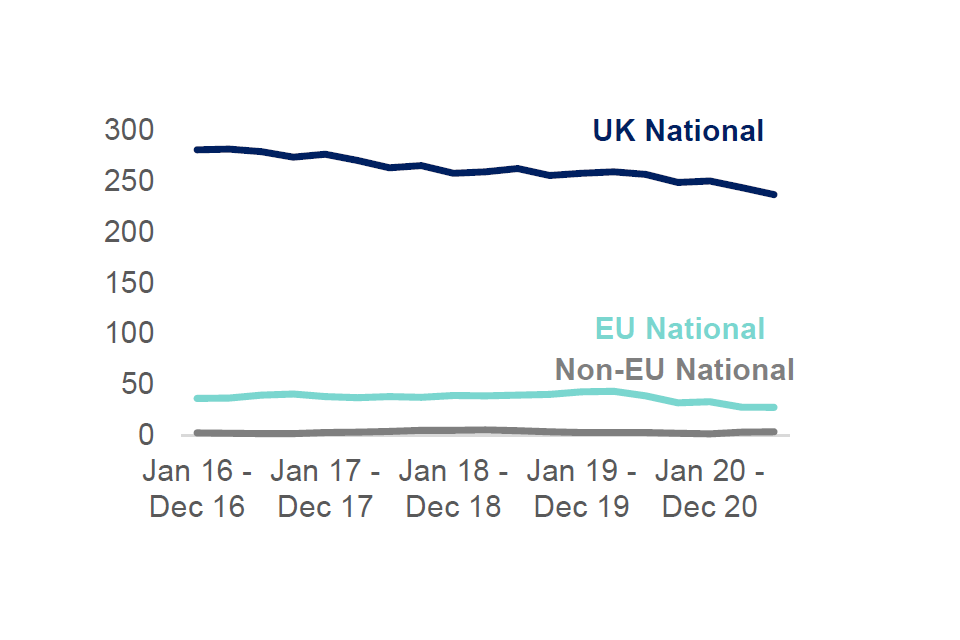

The COVID-19 pandemic led to a steep drop in the number of HGV drivers employed. The number of HGV drivers employed in other countries also decreased, with large shortages widely reported in Europe and the U.S.A. From the year ending June 2019 to the year ending June 2021, estimates suggest that the number of UK national drivers fell by almost 26,000 and the number of drivers from the EU fell by 12,000. We should however be cautious about these estimates given the difficulties in conducting the Labour Force Survey (see section below).

Figure 1.25: Number of HGV drivers employed, 2016 to 2021 (thousands)

Source: ONS, Annual Population Survey, Jan 16 - Dec 16 to Jul 20 – Jun 21.

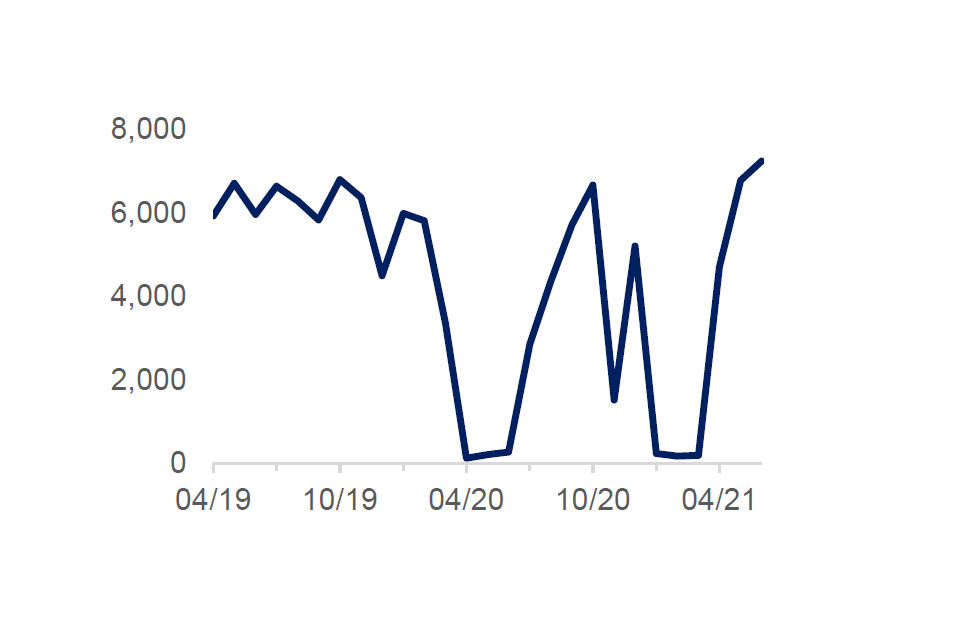

Figure 1.26: Number of LGV licence tests conducted, April 2019 – July 2021, monthly

Source: DfT/DVSA, DRT0501: Practical large goods vehicles (LGV) test pass rates by gender, monthly: Great Britain. 2019/20 to 2020/21.

The industry will need to drive up recruitment domestically in order to make a full recovery. One issue that has been raised is the number of tests that have been conducted during the pandemic. During the strictest national restrictions in April 2020 and March 2021, the number of new tests conducted fell dramatically to just 2.3% and 3.4% respectively of the number seen in February 2020. Whilst test numbers have now increased to above the pre-pandemic levels, this rise will need to be sustained to ensure that the shortage does not continue long term with UK drivers who leave the profession not being sufficiently backfilled by new starters seeking to qualify in the UK. The cost of training to become a HGV driver is high, and unless covered by an apprenticeship programme or subsidised by an employer, this cost acts as a barrier to individuals to enter the profession.

The makeup of the HGV industry may also present challenges. According to DfT, the industry is made up of 69,000 operators with an average fleet size of only 5.2 vehicles. The low average number of vehicles is due to the number of small firms greatly outweighing the number of large multinational firms. Smaller firms may struggle to attract new entrants if job security, conditions and benefits are perceived to be better in the large multinationals, and they may be less willing to train new workers given the risk of poaching by other firms.

In response to the shortage, the government introduced two schemes providing routes for HGV drivers to work in the UK. The first was a scheme allowing up to 300 EEA nationals qualified as fuel HGV drivers to be granted an emergency short term visa. The second was the provision for 4,700 emergency visas to be granted to HGV drivers for the delivery of food. Whilst full uptake figures are unavailable at the time of publication, the Minister of State for the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy said in response to a parliamentary question that nine letters of endorsement had been granted to drivers under the fuel tanker driver scheme as of 2nd November 2021.

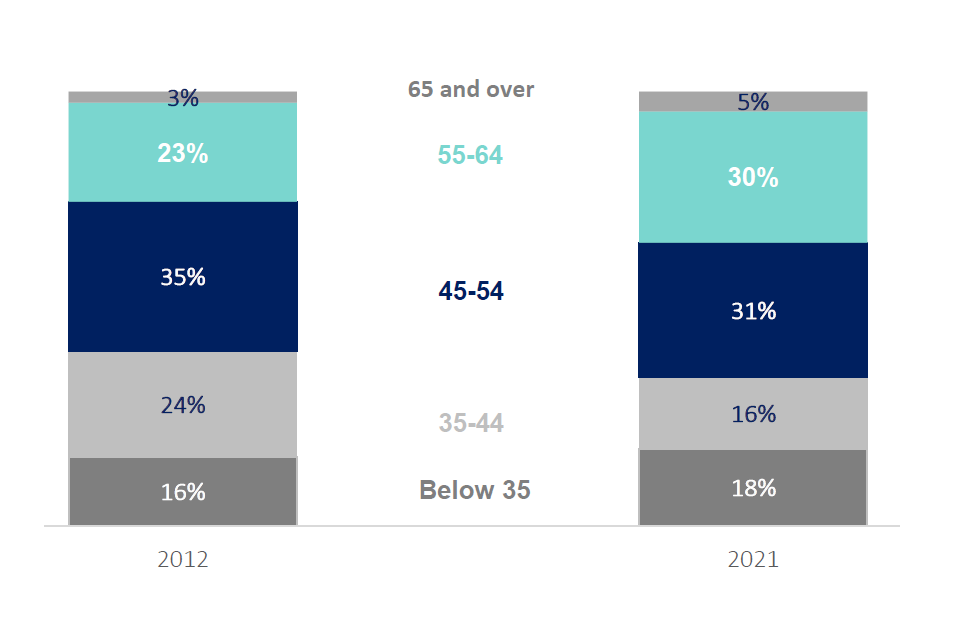

There are also long-standing demographic issues with the HGV workforce that show little sign of having been addressed in recent years. Of the current workforce, only 18% of drivers are below 35 years old, and the number of drivers aged below 45 has fallen since 2012. Meanwhile, the share of drivers aged 55 and above has increased slightly, showing that the workforce is ageing. In comparison, of all those employed in the UK, 31% are aged below 35.

Figure 1.27 – Share of the total HGV driver workforce, by age group

Source: ONS, Annual Population Survey, April 11 Mar 12 – April 20 Mar 21.

Annual Population Survey data estimates that women account for around 1% of the HGV driver workforce, with no significant change over time. The proportion of those from ethnic minority backgrounds represented in the workforce is also historically low. Only about 6% of HGV drivers are ethnically non-white, again with very little change over time. Compared to the whole UK workforce, where 48% of those employed are women and 13% are non-white, representation is very low.

The relatively low proportion of women and young people in the industry suggests that either access is difficult or that public perception of the job is negative amongst the under-represented demographics. Wages and working hours have an impact on the attractiveness of a job. The median number of hours worked in a week by HGV drivers was 48 in 2021, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) Labour Market Statistics. In comparison, the median for full time workers across the whole workforce in the UK was 36 hours . The estimated median wage for HGV drivers was £25,500 in 2012, rising to £30,600 in 2021 – an increase of 20%, according to Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) data. Over the same period, the adult National Minimum Wage (NMW) has increased by 44% from £6.19 per hour in October 2012 to the National Living Wage (NLW) of £8.91 in April 2021.

Both national and trade press have also reported that working conditions and facilities for drivers are poor, with a lack of suitable parking spaces with toilet or shower facilities being said to be a major issue. Some have said that working conditions are better abroad, which if correct, could make it difficult to recruit foreign workers to the industry. The government recently increased the number of hours that a driver can work before requiring a rest period, which may have worsened the perception of working conditions for drivers.

It therefore appears that a steep change needs to be made to increase the attractiveness of the job that would help to ensure that the industry maintains stability in the long term and attracts new types of workers. Such a change is likely to require co-ordinated action between industry, government and transport bodies.

Summary

Most HGV drivers are UK nationals who are over 45, male and white. They work much longer hours than the average worker and part-time work is almost non-existent. The shortage of HGV drivers is not a problem entirely to do with Brexit, with a large fall in the number of UK nationals employed in the industry when COVID-19 reached the UK. The failure to retain domestic workers accounts for much of the shortage seen in the post-pandemic recovery. There are wider issues in the occupation and its attractiveness, with young people not entering the profession, resulting in an ageing workforce and a poor record in attracting women to the industry. This combined with the difficulties in completing tests during the pandemic has exacerbated the issues faced by the industry.

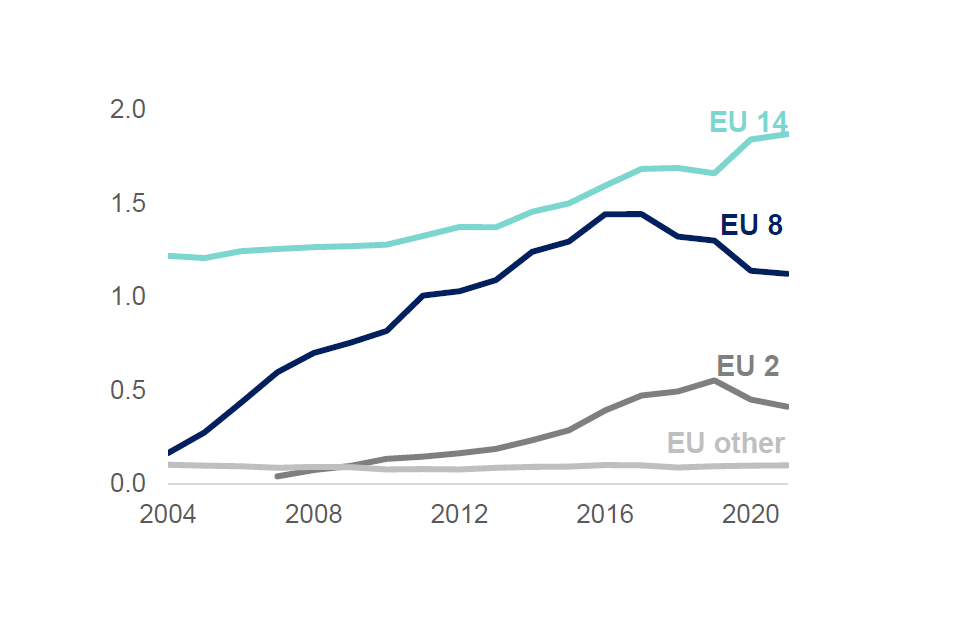

EU emigration

One of the most widely publicised questions about the impacts of the pandemic on migration was whether it led to an exodus of European Union (EU) citizens. This could be a result of job loss or wanting to be near family members during the crisis. Understanding how the EU migrant population changed during the pandemic is important for understanding their role in the post-Brexit labour market. In particular it was always assumed that the ending of freedom of movement would not cause any significant change in the stock of EEA workers in the UK but would rather change the flow as EEA workers would no longer be able to work in RQF 1-2 occupations, and would need a work visa for other jobs. If coincidentally the pandemic caused a marked reduction in the population of EEA workers already in the UK, this would cause significant problems for sectors that had a large share of EEA workers prior to the ending of freedom of movement, particularly if they were in RQF 1-2 occupations that could not be easily replaced going forward. Unfortunately, there have been several methodological issues with the main data sources because of the pandemic which have resulted in a large amount of uncertainty around such estimates. This section will discuss these issues and try to provide a sense of what the data seem to be telling us.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the International Passenger Survey (IPS) was the main source for statistics on the levels of migration into and out of the UK. This survey was not providing sufficiently accurate data to meet the demands of the policy debate and was due to be replaced with a new approach using administrative data to estimate the migrant population, inflows and outflows. Due to the pandemic, the migration component of the survey was retired earlier than originally anticipated, in March 2020. While the IPS resumed in January 2021, it no longer contains a migrant boost sample, which means that its value for measuring migration flows in future will be limited.

In the absence of the IPS or the new ONS admin-based migration estimates, the main source of data that has remained available to examine EU migration has been the Labour Force Survey (LFS). The LFS provides population estimates to measure changes in the stock of migrants in the UK. It does not measure immigration or emigration flows and provides only an indirect measure of net migration.

Initial outputs from the LFS indicated that around a million people had left the UK in 2020. However, subsequent investigation concluded that this was largely the result of measurement problems and did not reflect real changes in migration patterns. In particular, the LFS interviewers stopped visiting respondents’ addresses to make contact and conduct interviews. Instead, they contacted them by letter, following up by telephone where they were able to obtain a phone number. This new approach led to lower response rates to the survey across the board. It is now widely understood that this change in method had a disproportionate impact on the foreign born, leading to an underestimate of their numbers. This underestimate of migrants, coupled with the fact that the estimated UK population had not been adjusted, also led to an implausible increase in the estimated number of UK born people living in the UK.

In response to these problems, the ONS issued a revised and reweighted dataset in September 2021. The reweighting attempts to adjust for migrants’ increased non-response, using data from administrative sources (notably HMRC PAYE data) that are thought to be less affected by the pandemic. Administrative data suggested that the decline in the employed migrant population had been smaller than the LFS suggested. It must be recognised however there is still a lot of uncertainty about the estimates.

After the reweighting, the estimated EU migrant population is much more stable. Instead of a decline in the hundreds of thousands, the reweighted figures suggest that the EU-born population was broadly stable, declining by only 47,000 between the last quarter of 2019 and the same period in 2020. However, when the reweighted LFS figures are used to examine subgroups of the migrant population and their change over time, there are some unexpected and, in some cases, implausible increases in certain migrant groups. For example, the reweighted data show a 247,000 increase in the number of EU-14 born migrants, alongside a 133,000 decrease in the number of EU-8 migrants. The increase in EU-14 is not explained by actual immigration flows, however. It is primarily driven by a higher estimate of migrants who arrived before the pandemic. In other words, it may simply reflect continued problems with non-response in the survey. For example, it seems likely based on these figures that non-response increased more among EU-8 born than EU-14 born, resulting in an overestimate of the EU-14 born numbers when EU migrant respondents were reweighted to match totals from other datasets. ONS has recognised the uncertainty in LFS-based estimates for migrant subgroups and have recommended that data below the EU and non-EU level should not be compared with previous years. It does however make us considerably cautious in placing faith in any of the published data on levels and changes in the EU-born population.

Figure 1.28: Number of EU migrants estimated to be living in the UK by place of birth, 2004 – 2021, (millions)

Source: ONS, population by country of birth and nationality.

Note: 2021 point is for July 2020 – June 2021, all others are calendar year. These estimates are based on Annual Population Survey (APS) data.

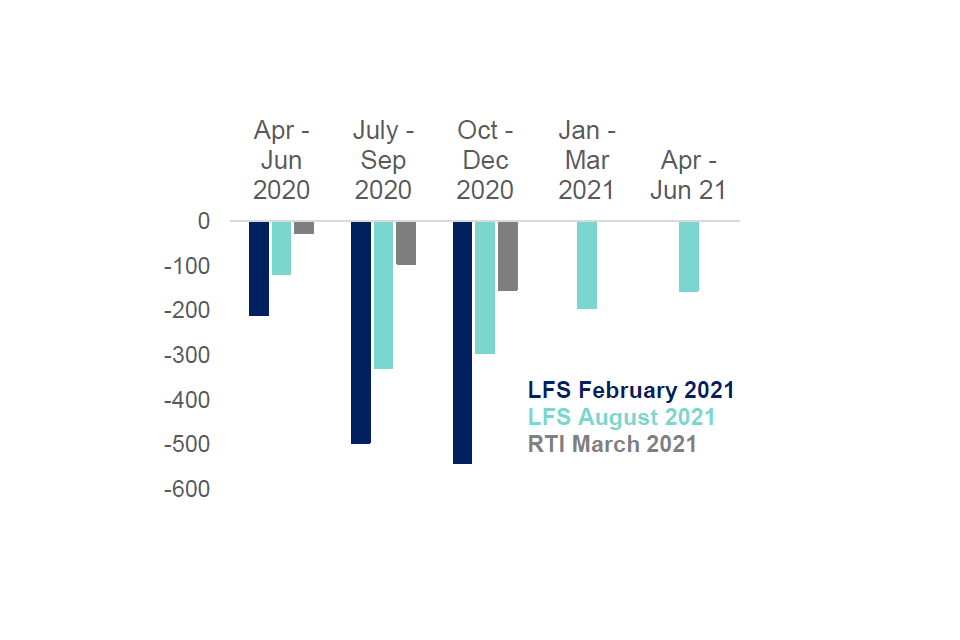

Figure 1.29: Estimated change in the level of EU employment since Jan – March 2020, by different sources (thousands)

Source: LFS February 2021, LFS August 2021 and Real Time information (RTI).

Note: LFS data is by country of birth, RTI data is by nationality.

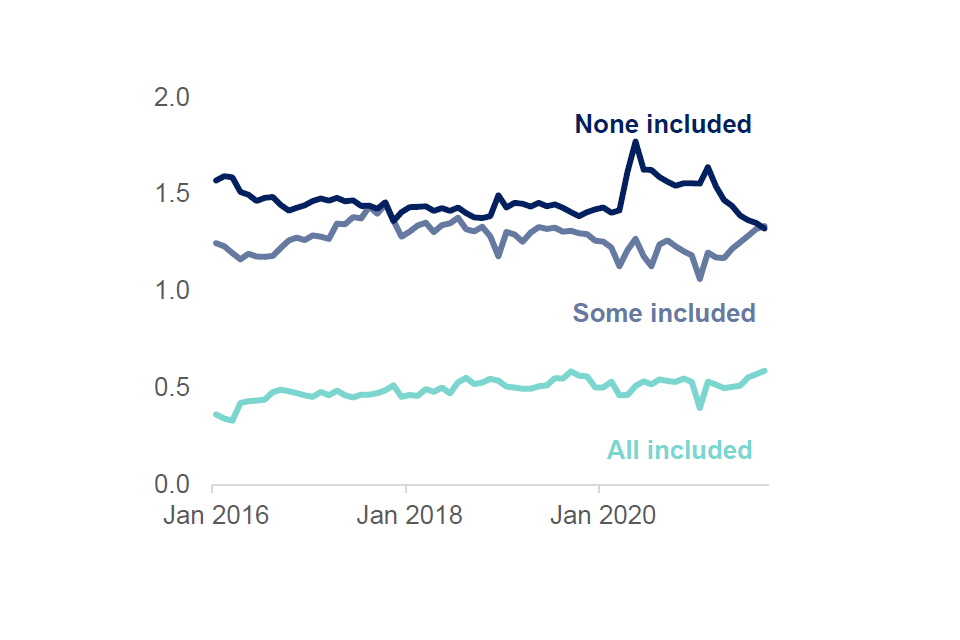

Figure 1.29 shows the disparity in estimates when looking at changes in EU employment across the different sources. Original estimates from the LFS suggested EU employment had fallen by 500,000 by the end of 2020, whereas more recent estimates suggest it was never more than 300,000 (and has already recovered to a drop of around 150,000). Data from HMRC PAYE Real Time Information (RTI) which measures the number of pay-rolled employees never estimated the drop to be more than 150,000. It should be noted that the RTI does not include the self-employed, so these data are not directly comparable. It does however strongly point to a significant over-estimate of the decline in EU workers using the survey-based measures.

The overall picture is that the number of EU migrants who left the UK during the pandemic is simply not known. While it seems very likely that the number is lower than the initial estimates that suggested net emigration of approximately 890,000 for all non-UK born, it is also quite possible that the reweighted LFS figures are not accurate. Data from HMRC RTI does suggest significantly smaller falls in the number of EU nationals in pay-rolled employment, although the latter could be affected by more people working abroad temporarily while remaining on UK payrolls during the pandemic. More insight should be possible with the recently published admin-based migration estimates for 2020. The 2021 Census data will also help to address the methodological issues as it will be possible to reweight the LFS data based on the results of the 2021 Census (with the caveat that Scotland has delayed its Census to 2022).

The uncertainty in the current LFS data will have implications for the MAC’s work in the coming year. There have always been problems with migrant non-response in the LFS data; for example, the survey fails to capture newly arrived migrants (Sumption, 2020). However, the increased uncertainty over changes during 2020 and 2021 will create additional challenges in understanding the role of migration in the post-Brexit and post-pandemic labour market.

2: Asylum and integration

The tragic losses of life in the English Channel in recent weeks and months, as people have taken enormous risks to seek a new life in the UK, have highlighted the complex issues around asylum. At the same time, the Nationality and Borders Bill proposes substantial changes to the asylum rules. In this Chapter, we give a broad overview of the asylum context in the UK and discuss policies that can help to improve the integration and long-term outcomes of asylum seekers, particularly in relation to the labour market. The MAC does not intend to comment on broader questions of asylum policy, as the legal and operational aspects of the asylum system are outside of our remit.

Asylum applications and grants in the UK

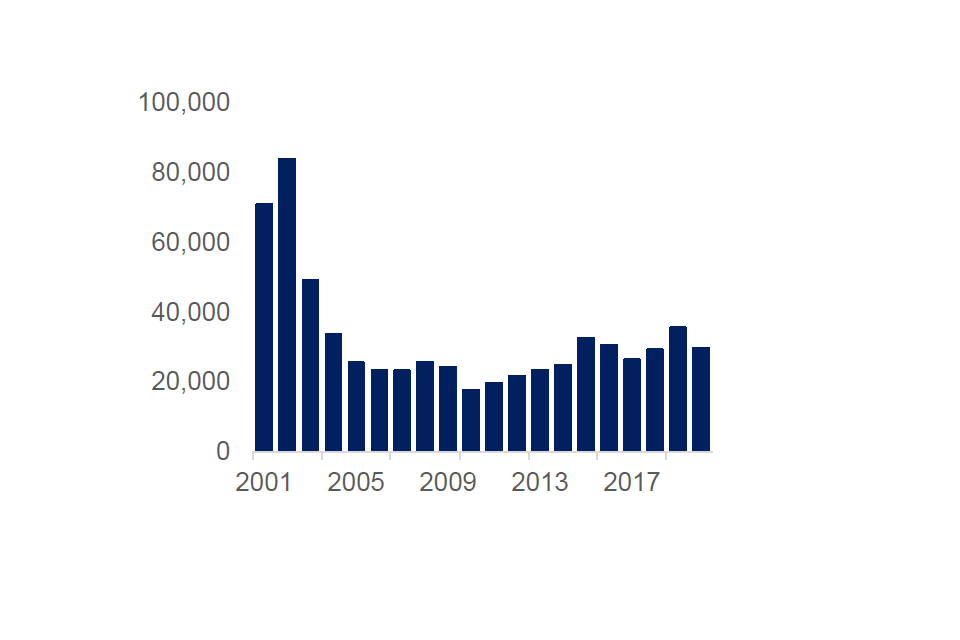

There are multiple factors contributing to asylum application levels in the UK, such as the UK’s geographical location (being an island in North-Western Europe, and hence unlikely to be the first safe country asylum seekers enter), the prevalence of civil wars and other dislocations in source countries, and more recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic where global travel plummeted, and borders closed. Figure 2.1 shows the total number of asylum applications received in the UK from 2001 to 2020. Levels in 2020 were 17% lower than 2019: some of this may be a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and travel restrictions. Current levels are broadly in line with those observed over the last decade, and notably lower than the levels at the beginning of the Millennium. Data for the whole of 2021 are not yet available although there was a significant uptick in asylum applications in the summer of 2021.

Figure 2.1: Total number of asylum applications

Source: Home Office Immigration statistics

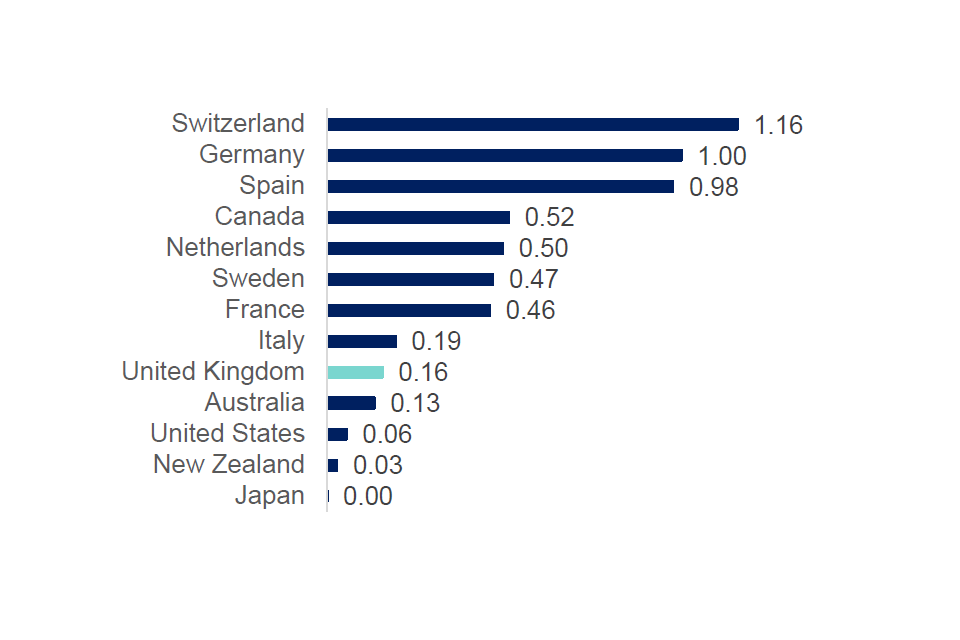

Figure 2.2: Estimated asylum grants per 1,000 population 2020

Source: UNHCR 2020 Asylum Decisions, Worldbank.

The UK is below the EU average in terms of grants per 1,000 population. This difference is largely a result of a lower number of applications in the UK, rather than a stricter grant rate compared to other countries. Figure 2.2 shows a comparison of asylum grants per 1,000 population between the UK and selected countries for 2020. The UK had a rate of 0.16 per 1,000 population, which was much lower than many other countries in Europe, such as Sweden (0.47) and Germany (1.0), but above that of the United States (0.06). It is important to remember that the countries that tend to host the largest numbers of refugees are those closest to the source countries, irrespective of their ability to manage such flows.

In common with other countries in Europe, small boat arrivals have become increasingly used to reach the UK in recent years, and since 2018 a growing number of migrants have been arriving across the English Channel by this means. There are no regular published statistics on the numbers of migrants detected to arrive in the UK by boat. However, provisional figures are released occasionally in press reports, and in 2020 an estimated 8,500 people arrived via small boats (PDF, 837 KB), and this had increased to an estimated 23,000 in 2021 by 11 November (1,185 on that day alone, with an additional 15,000 having been prevented from crossing by French authorities by the end of October). Previous evidence has indicated that the vast majority of those crossing the Channel have claimed asylum in the UK.

The UK also offers support to refugees through resettlement schemes. These are different to the asylum route (where the individual applies for asylum after arrival in the UK, and their application is then considered), as under resettlement the individual is recognised as a refugee before arrival in the UK. Previous resettlement schemes have included the Syrian Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS) and currently the UK Resettlement Scheme (UKRS) and Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP). The Government has said that the forthcoming Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) would see around 5,000 people arriving in the first year and up to 20,000 over coming years. This chapter largely focuses on asylum seekers, rather than refugees that have arrived via resettlement schemes, given that the latter are permitted to access the labour market.

The foundations of integration

The MAC is primarily interested in how well asylum seekers are integrated into the UK, both in the labour market and in terms of social integration and the policies that can help to support their integration.

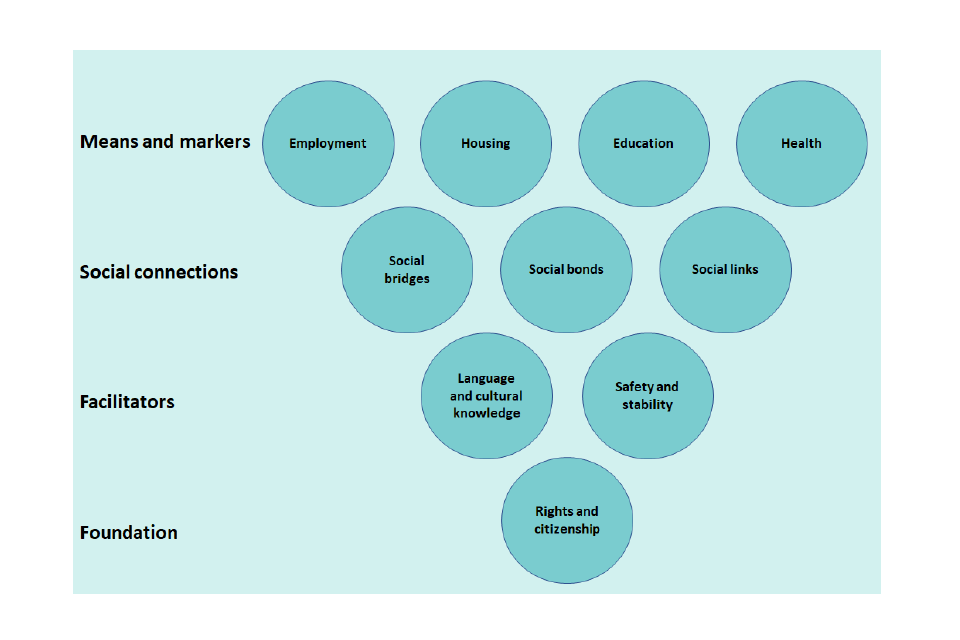

The Home Office report Indicators of Integration (Ager and Strang, 2004) (PDF, 146 KB) conceptualised the process of refugee integration as a series of “domains” including markers and means (employment, housing, education, and health) and social connections (bonds with those of the same national/cultural background, bridges with those of different backgrounds and links with civil societal institutions). Underpinning all of these was the foundation of rights and citizenship, followed by safety/stability, and language/cultural knowledge (the framework was further updated in 2019 to include digital skills and communication as additional facilitators). This conceptualisation underlines the importance of the decision on refugee status, and the acquisition of English language, in acquiring employment.

Figure 2.3: Home Office Indicators of Integration framework

Source: Indicators of Integration, Ager and Strang (2004).

Over time the source countries for asylum seekers have changed, as they are driven by the location of global crises and conflicts. Table 2.4 shows the top five source countries for granted asylum applications in the UK at five-year intervals. As the composition changes, the needs of the refugee populations also fluctuate according to the most prevalent source countries and the specific circumstances precipitating departure. For example, the estimated adult literacy rate in Afghanistan is 43% (30% for women) compared to 86% in Iran and Iraq. Family sizes, ability to speak English, psychological and physical health and trauma, age and cultural gender norms, all of which also have an impact on ability to engage with work-readiness related activities such as English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) and job search, also vary by nationality. This is similarly true for resettlement schemes, where needs may also vary according to intake. For example, intakes of Iraqi and Afghan refugees in the past have included those who have acted as interpreters for British forces overseas.

Table 2.4: Top five source countries for UK asylum grants, and levels

| 2006 | 2011 | 2016 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somalia (1,400) | Iran (1,654) | Eritrea (2,444) | Iran (1,538) |

| Eritrea (1,276) | Sri Lanka (860) | Iran (2,247) | Eritrea (862) |

| Afghanistan (972) | Eritrea (779) | Syrian Arab Rep. (1,812) | Sudan (839) |

| Zimbabwe (972) | Pakistan (656) | Sudan (1,405) | Iraq (812) |

| Iran (763) | Afghanistan (649) | Afghanistan (1,220) | Afghanistan (668) |

Source: UNHCR asylum decisions.

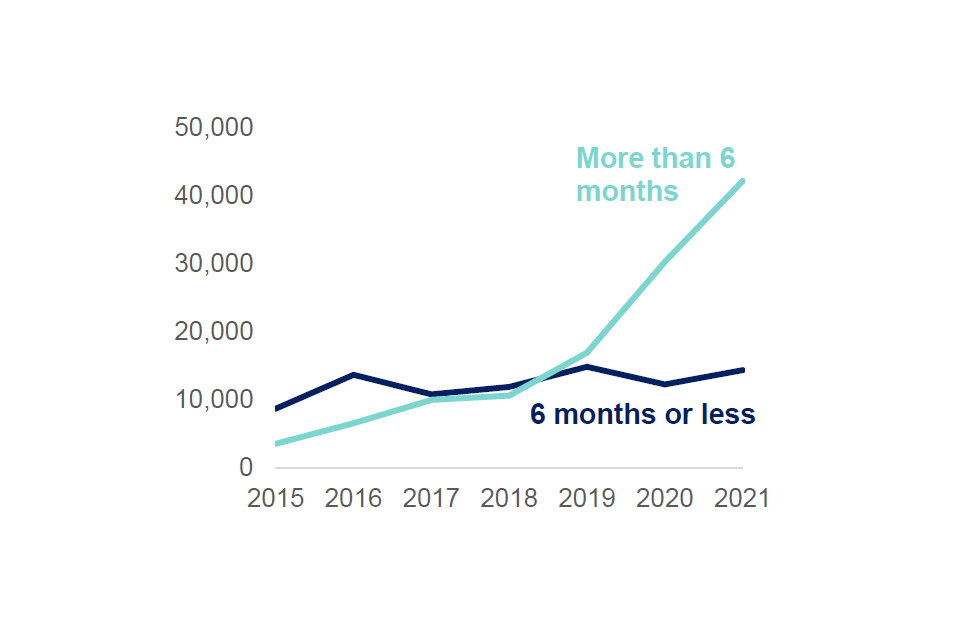

Figure 2.5: Asylum applications awaiting an initial decision by length of waiting time

Source: Home Office Immigration statistics Asylum applications awaiting a decisions (Asy_D03), all points are 30 June of the year.

Grant rate at initial decision also varies widely by nationality: published migration statistics indicate that Libyans (93%) and Eritreans (74%) typically have high grant rates at initial decision, while nationals of India (4%) and Bangladesh (17%) have low grant rates. This is relevant as people can only seek work once their claim has been granted.

Figure 2.5 shows the number of applications awaiting an initial decision by the length of waiting time. As of the end of June 2021, there were around 56,600 asylum applications pending an initial decision. Of these, 75% of applications had been waiting for their decision for longer than six months. This share is much higher now than it was five years ago, when only 33% had to wait more than six months for an initial decision. These lengthy delays directly harm the integration of asylum seekers and interact with rules that restrict access to work and English language opportunities that we highlight below.

(i) Labour Market Access

Asylum applicants in the UK are generally not permitted to work whilst their application is pending a decision. If applicants have not received a decision within 12 months, they may apply for permission to work, however if this is granted, they are only able to work in occupations listed on the SOL.

As asylum seekers cannot work whilst awaiting a decision, they may become disengaged with the labour market, therefore making it harder for them to integrate if they are ultimately granted asylum in the UK (as almost half – 48% - were at initial decision in year ending March 2021; this typically increases by 10 to 20 percentage points once appeals are taken into consideration). Ruiz and Vargas-Silva (2021) (PDF, 475KB) explore the existing literature on this and found that the evidence generally supported the idea that shorter waiting times had a large positive impact on long-term employment outcomes for asylum seekers. Similarly, a German study found that employment rates were around 20 percentage points lower for those who had had to wait an additional seven months to access the labour market and that, moreover, this employment gap persisted for around 10 years. Refugee Action (PDF, 3.3 MB) have carried out research which echoed this, describing the anxiety and stress experienced by those awaiting a decision, and commenting that both the impact on wellbeing and the periods of destitution experienced while unable to work or study would be likely to hinder long-term integration. Indeed, the study by Ruiz and Vargas-Silva cited above found that differences in health (particularly mental health) between refugees and other migrants were one of the factors that could explain lower employment outcomes for refugees compared to other groups.

The Home Office has tended to argue for an employment ban for asylum seekers due to the so-called ‘pull factor’. The argument is that asylum seekers may choose to come to the UK over other safe countries because of the attractiveness of the labour market. One review of international evidence (PDF, 791KB) around the ‘pull factor’ found no correlation between access to the labour market and choice of country for asylum. By contrast, other pull factors such as family/friends in the destination country or language spoken amongst others tended to be more important. The Home Office recently made a parliamentary statement regarding analysis of the employment ban, but this contained no evidence on the ‘pull-factor’ but rather focused on fiscal issues which are not the focus of our concern. To the extent that the Home Office has robust evidence to support a link between the employment ban and a pull factor, they should of course make this evidence publicly available for scrutiny and review. That is how good policy is made.

Currently the policy in the UK is more restrictive than in many other countries: EU law specifies that asylum seekers must be allowed access to the labour market after a maximum of nine months; many countries do so after a shorter period, such as Sweden (immediate), Portugal (one month), Germany (from three months), Belgium (four months), and the Netherlands (once residence permit is granted). In Canada and Australia asylum seekers can work immediately, and in the United States they can do so after six months (PDF, 340 KB).

As waiting times for asylum applicants have increased, the work restriction has the potential to become more detrimental to the long-run success in the UK of those ultimately granted asylum. The MAC would recommend the Government review their policy on allowing asylum seekers to work. One option might be to allow applicants to work if an initial decision has not been made within six months. We also question the value of the current restriction that allows work after 12 months only on SOL occupations – this was never the purpose of the SOL, and the original reasoning behind this restriction does not seem to be particularly coherent.

(ii) English Language Skills

As highlighted in a 2017 House of Commons research briefing (PDF, 203 KB) on ESOL provision for refugees, refugees are eligible for ESOL funding via the Adult Education Budget, which asylum seekers can also access after six months waiting for their decision. Resettled refugees (i.e. those who have been granted asylum overseas before entering the UK on a resettlement programme) are eligible for funding over and above this: an additional £850 funding per learner; with a minimum of eight hours’ tuition per week, with additional funding for childcare to enable adults to attend ESOL classes. There are no minimum tuition levels for those on the asylum route. ESOL funding is provided to ESOL Entry 3 (B1 Common European Framework of Reference – CEFR) level in England. In Scotland, refugees and asylum seekers who are waiting for a decision can also access free ESOL, without the waiting period of six months that applies in England, and those who have been granted an alternative form of status such as humanitarian protection, can access free ESOL courses. Wales also does not differentiate between learners on the basis of status and allows asylum seekers as well as refugees to access ESOL. In Northern Ireland, ESOL is also free for refugees.

However, a 2016 report by Refugee Action, Let Refugees Learn (PDF, 2.6 MB) highlighted that despite this, and their desire to learn, refugees face significant barriers in actually accessing ESOL, such as long waiting lists (leading to either not being able to access support at all or being placed in a class at the wrong level), distance to colleges and travel costs, childcare difficulties and barriers relating to gender norms. The APPG on refugees has also raised these concerns. Bloch (2007) also suggests work to overcome individual employability barriers alongside these other factors. We would recommend that the Government review both ESOL provision and accessibility including for asylum seekers, potentially alongside other provision such as digital skills, and considers making free ESOL provision accessible to asylum seekers immediately (rather than after six months) in England, as in Scotland and Wales.

3: Immigration and social care

In July 2021 the Migration Advisory Committee (MAC) was commissioned to undertake an independent review on the impact of the ending of freedom of movement on the adult social care sector. Whilst the MAC has been asked to report in April 2022, based on early analysis we have already identified several key trends and problems within the workforce that the committee think need to be addressed urgently.

Based on the evidence we have collected so far this update outlines these worsening trends and provides an interim policy recommendation for care workers to potentially alleviate some of these problems. Our extensive evidence collection process is ongoing, and this update does not pre-empt any recommendations in our final report. Instead, it seeks to address some of the immediate problems faced by the sector.

The MAC continues to engage with stakeholders and gather more evidence, including through analysis of the recently closed Call for Evidence and other sources for our full report in April. That report will be based on a full analysis of all the available evidence. It will consider in more detail the appropriate immigration routes for adult social care workers.

Key trends and problems in adult social care

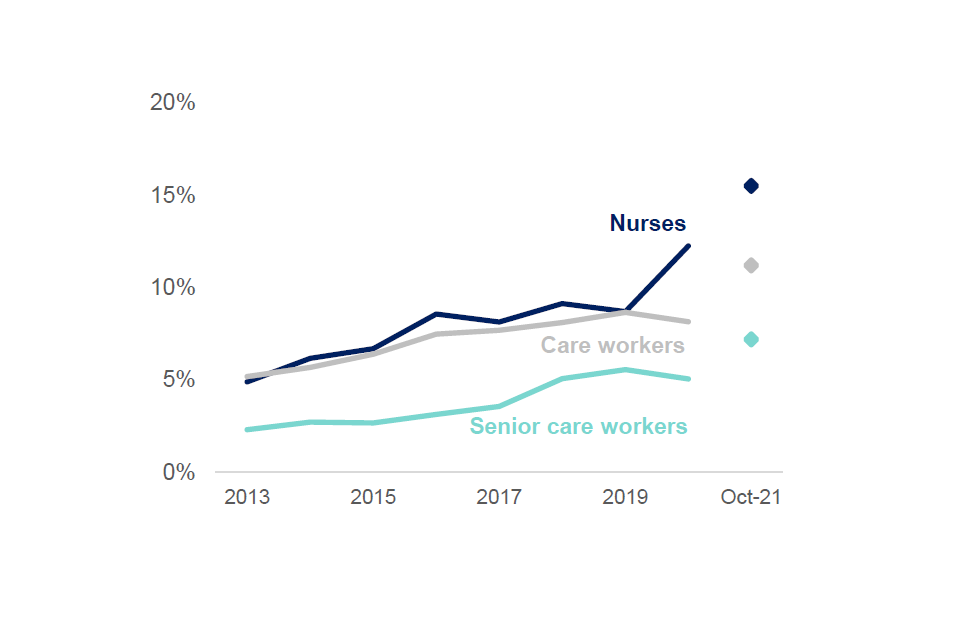

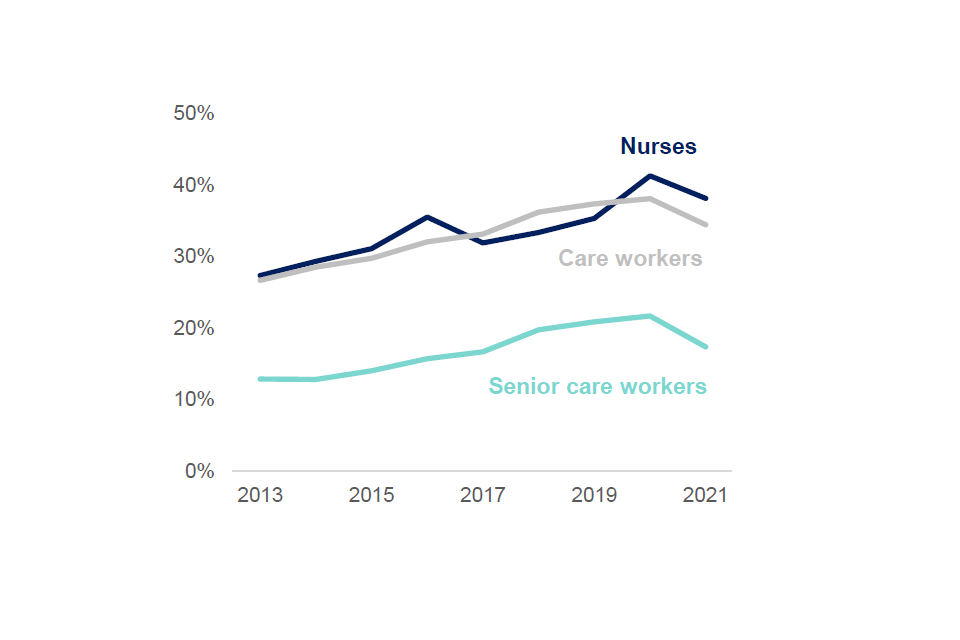

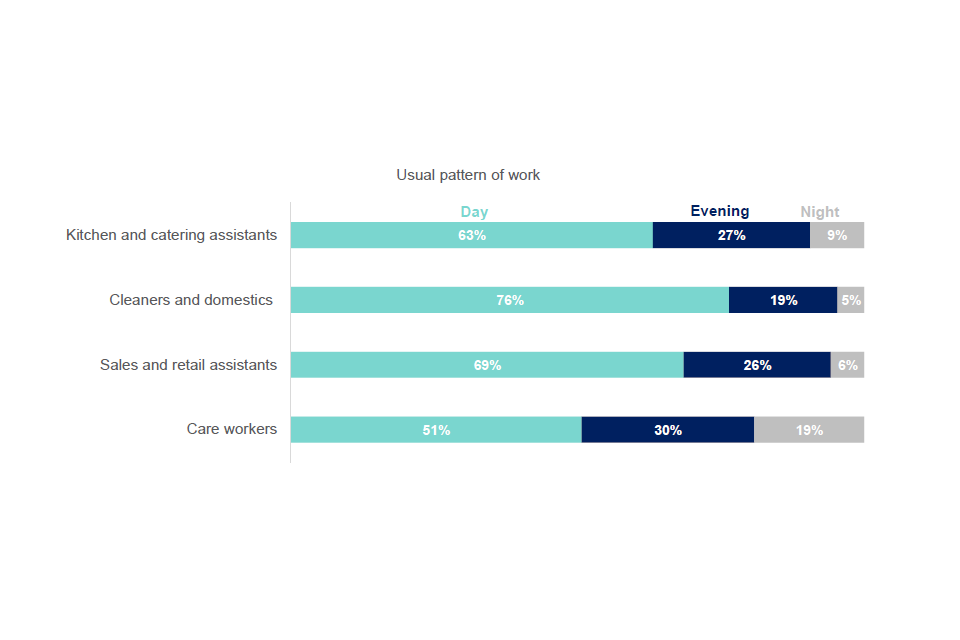

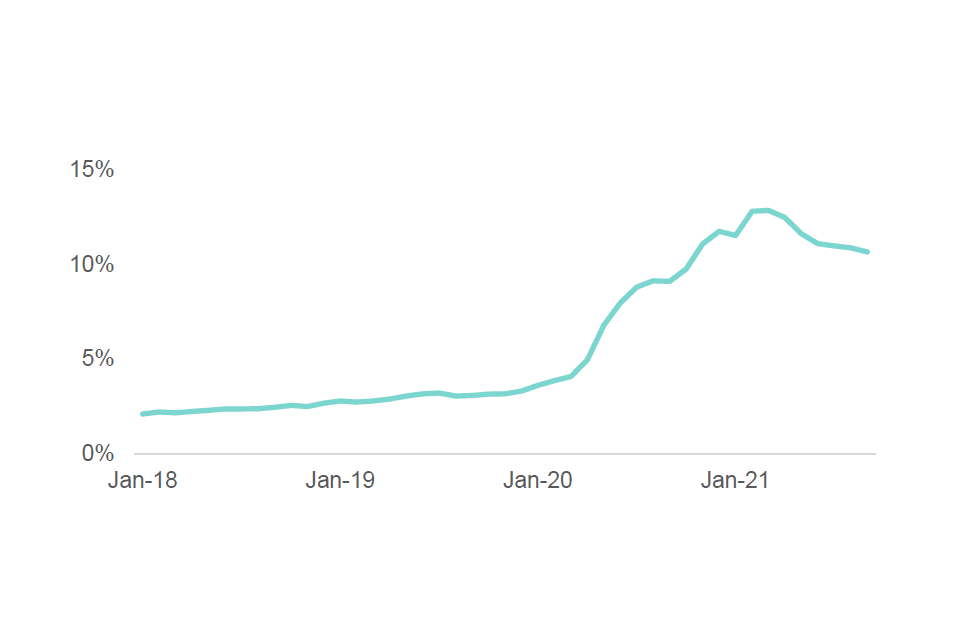

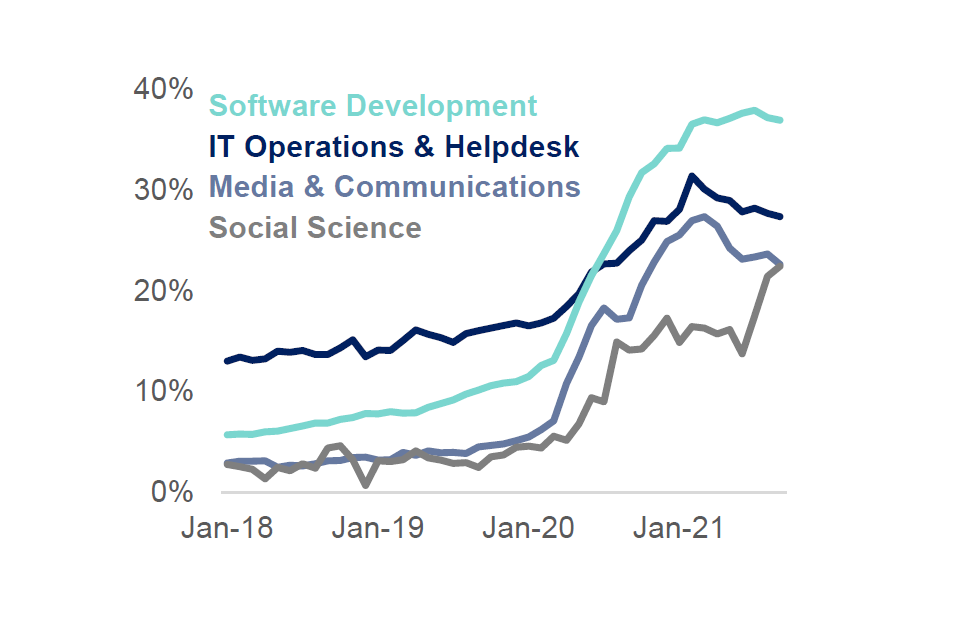

The share of non-UK born workers in the adult social care sector is greater than in the wider economy, although the share of European Economic Area (EEA) born workers is slightly lower. As the largest occupation in the sector, care workers account for over three quarters of the adult social care workforce involved in direct care provision. The share of non-UK born care workers has increased over time accounting for 19% of the occupation in the UK in 2012, and 24% in 2020. As Figure 3.1 and 3.2 indicate, non-EEA care workers account for a greater share of the occupation compared to those from the EEA. The share of non-EEA care workers in the UK has increased from 14% in 2012 to 18% in 2020. The share of EEA care workers is still important, growing from 5% of the workforce to 6% over the same period.

With over 50% of EEA care workers stating that they came to the UK for employment, the ending of free movement and the absence of a work route for care workers is likely to contribute to the recruitment problems faced by the sector. However, many of the workforce problems faced by the sector predate the end of free movement and, as highlighted, the sector is more reliant on non-EEA born workers.