Mental health and loneliness: the relationship across life stages

Published 12 June 2022

Executive summary

This report presents the findings from a qualitative study exploring the experiences of loneliness among those who had experienced a mental health condition. Previous research has shown there is a link between experiences of loneliness and poor mental health. The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) commissioned this study to explore this issue across four key life stages as part of developing the evidence base for work on tackling loneliness.

The study aimed to explore:

- how those with diagnosed mental health problems experience loneliness

- the extent to which social stigma associated with mental health conditions plays a role in experience of loneliness

- how experiences of loneliness among those who have experienced mental health conditions vary by life stage.

The report draws on findings from:

- six interviews with professional expert stakeholders

- 37 in-depth interviews and 14 diaries from those experiencing loneliness who also had a history of mental ill-health

Participants were recruited from one of the following four life stages:

- young adulthood (18 – 30 years old)

- parents of young children (with children aged 5 or under)

- middle aged (40 – 60 years old)

- retired[footnote 1]

Across the sample there were a range of mental health conditions experienced including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder and borderline personality disorder, among others.

The relationship between loneliness and mental health

Participants did not always describe themselves as feeling ‘lonely’. Instead they talked about feeling isolated, alone, or being a loner. Other ways in which participants talked about the lack of connection they felt in their lives was to describe not having anyone they could turn to for emotional support, or feeling like a burden on those they had existing connections with.

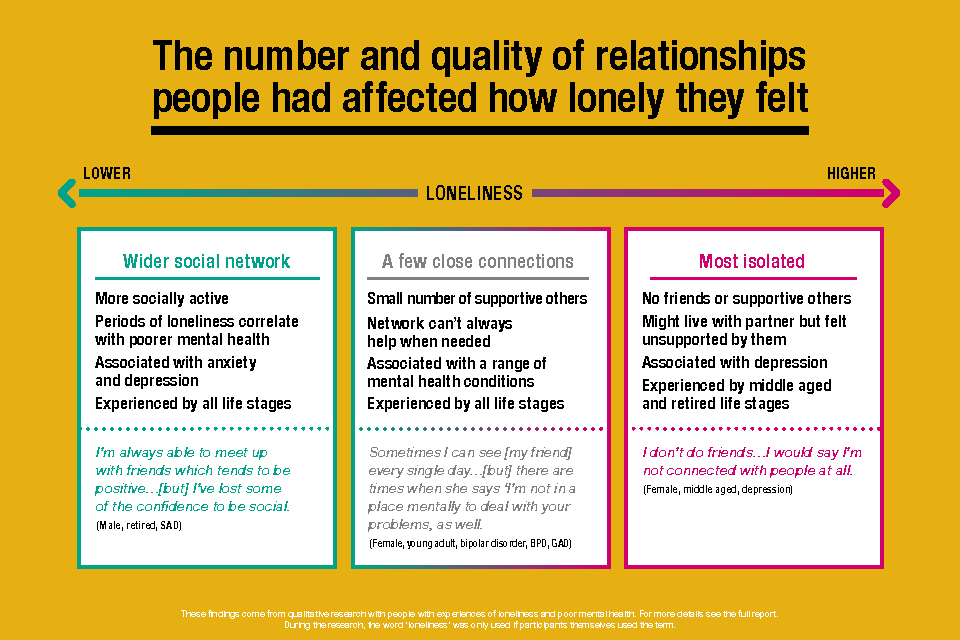

Across the sample there was a spectrum of experiences of loneliness. Those who were most lonely described feeling isolated, with no close friends or supportive others. Participants in this group tended to have depression and be in the middle-aged or retired life stages. At the other end of the spectrum, the least lonely people were those with a wider social network, including close connections who provided emotional support. Participants in this group tended to have experienced anxiety and depression and were found across all life stages. For this group, periods of loneliness correlated with poor mental health. In between these groups were people with a few close connections, and a small number of supportive others. However, these social connections were not always able to provide the level of support participants needed.

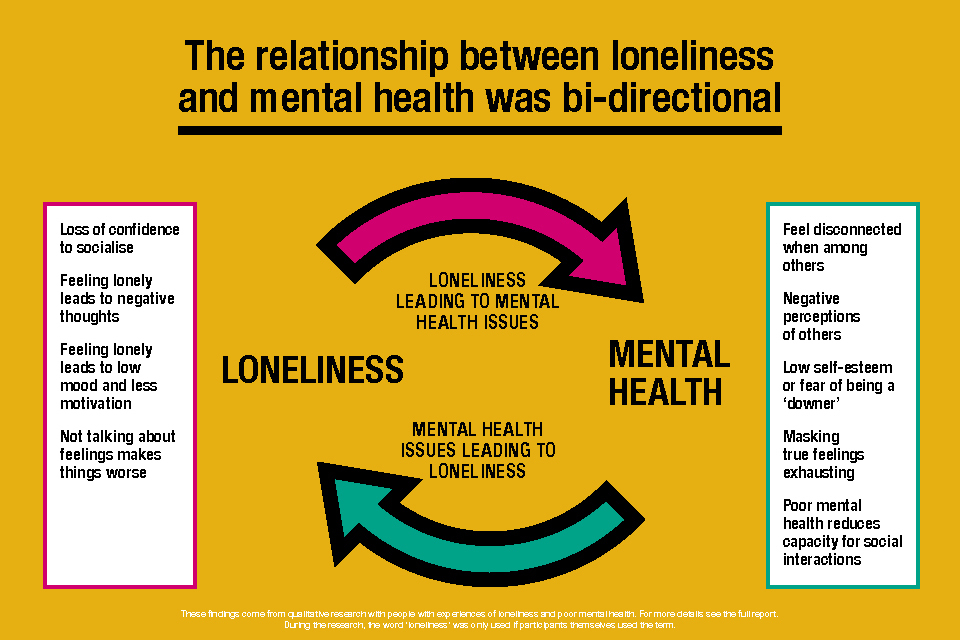

The relationship between loneliness and mental health was bidirectional and cyclical. Participants described the following ways in which mental health issues could lead to greater feelings of loneliness:

Mental health conditions reduced capacity for social interaction. Low mood could lead to social withdrawal or feeling disconnected from others. Mental health conditions could lead to people simply feeling too exhausted to engage with others. Public spaces for socialising could also feel overwhelming. Participants felt their mental health thwarted their capacity to be supportive to others.

Negative perceptions about themselves or others could lead to withdrawal. Mental health conditions were associated with feelings of low self-esteem and participants worried about the stigma they might experience if they revealed their mental health issues. Certain conditions could also lead to negative perceptions of social relationships, leading to brooding, anger or intolerance of others.

Not being able to share that they were struggling with others, and feeling the need to hide mental health symptoms for fear of being seen as a ‘downer’ could also lead to feelings of loneliness. Maintaining a pretence of being fine when around others was exhausting and unsustainable for participants, leading to them withdrawing from social contact instead.

On the other side, loneliness could also lead to a decline in mental health. This happened where participants had more time alone to ruminate on negative thoughts; where they lost confidence in their ability to socialise, leading to low self-esteem; and where not talking about their feelings led to them feeling even more overwhelmed. This deterioration in mental health could then precipitate further withdrawal and isolation.

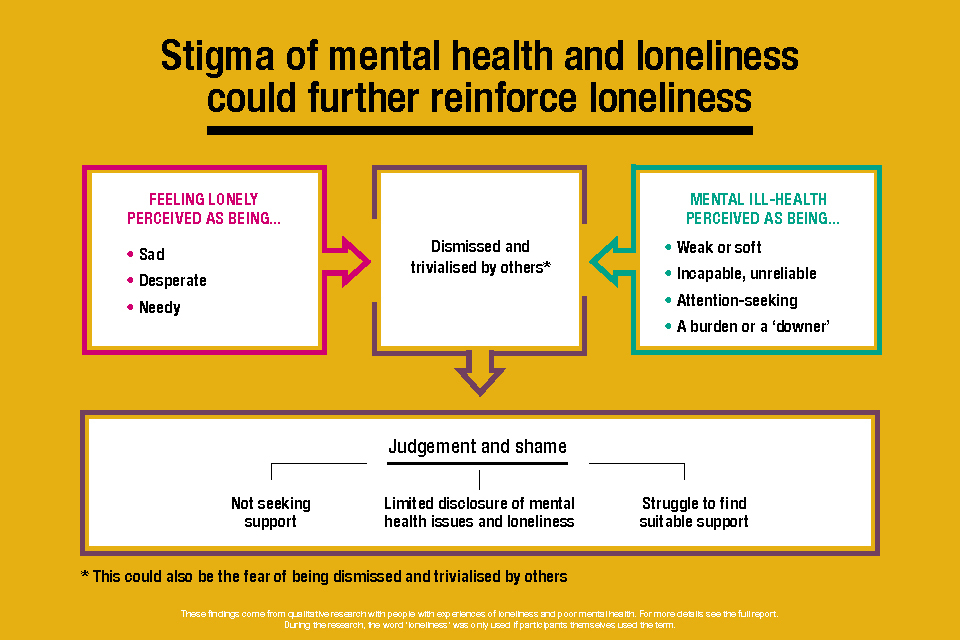

Stigma associated with mental ill-health and loneliness clearly affected participants’ ability to be open about their feelings, leading them to also feel less connected to others. Participants experienced stigma associated with both mental ill-health and loneliness, with some elements of both overlapping. Although participants felt that mental ill-health is much more widely talked about than in the past, it was still largely felt to be misunderstood in society. The stigma associated with mental health conditions led to participants internalising negative views that they would be seen as ‘weak’, ‘unreliable’, ‘attention-seeking’, ‘a downer’ or ‘a burden’. On the other hand, the stigma linked to loneliness meant people avoided using the term, feeling that admitting they are lonely meant others would see them as ‘sad’, ‘needy’ or ‘desperate’. Reactions of dismissal or trivialisation when people admitted they were struggling left participants feeling judged or shameful, reinforcing stigma, and sometimes preventing them from seeking help.

Key events across life stages

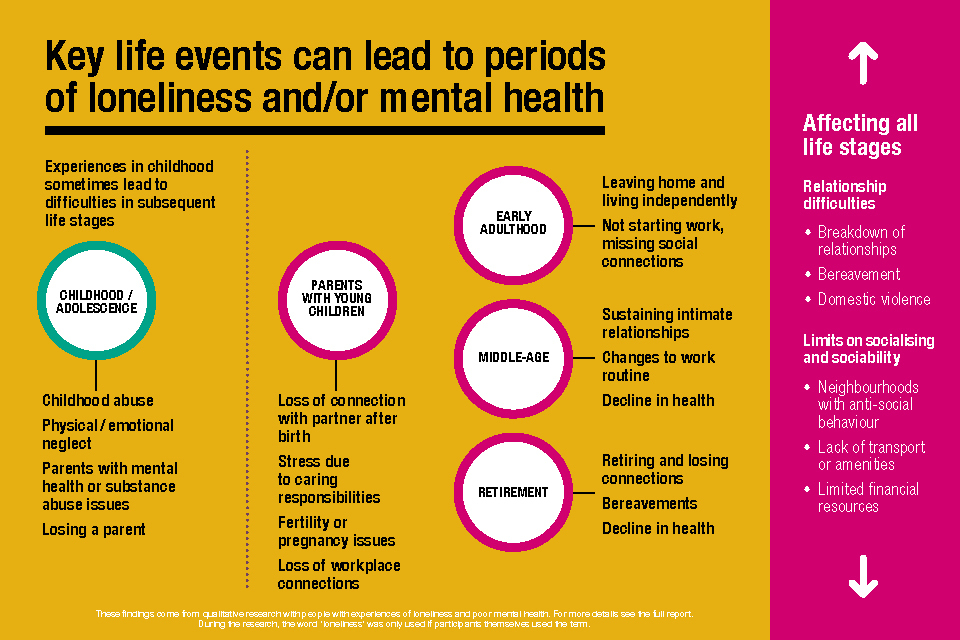

There were a number of key events across the different life stages that were associated with periods of loneliness or a decline in mental health. Adverse events in childhood or adolescence such as experiences of abuse, neglect, losing a parent or having parents with mental health or substance abuse issues were linked by participants to effects on their mental health in later life. Stakeholders felt that these events could set up patterns of psychological difficulties in later life.

In early adulthood, leaving the family home and the transition to living independently was associated with a risk of loneliness or poor mental health. For participants whose mental health prevented them from working, not having a new social circle through the workplace could lead to feelings of loneliness.

For parents of young children, the increased stress associated with new caring responsibilities sometimes led to poor mental health or increased isolation. The weight of social expectations (for women that they should be able to manage, for men that they should take responsibility for their family) made it difficult to admit they were struggling and to ask for help.[footnote 2] This then fed into feelings of loneliness. Increased loneliness was felt by female participants who experienced fertility issues or pregnancy loss but who felt unable to share with others due to embarrassment.

For those in the middle-age and retirement life stages there were a number of overlaps in the types of experiences or events that led to loneliness. A decline in physical health was associated with increased feelings of loneliness and a deterioration in mental health. People experiencing chronic pain or mobility issues were sometimes no longer able to participate in social activities. For those in middle-age, managing difficult family situations could result in stress, anxiety and feeling overwhelmed. Examples included single parents of children with special educational needs or disabilities, or where fathers were estranged from children. For some single participants, difficulties finding and sustaining intimate relationships took on a greater significance later in life, with some saying they had lost hope of meeting a partner. Changes to work routines – whether redundancy, increased home working, or retirement - could also trigger feelings of loneliness where regular social contact with work colleagues was lost. Finally, experiences of bereavement became more frequent as people aged, and this triggered feelings of loneliness, particularly after the loss of a partner or close family member.

Recommendations for improving support

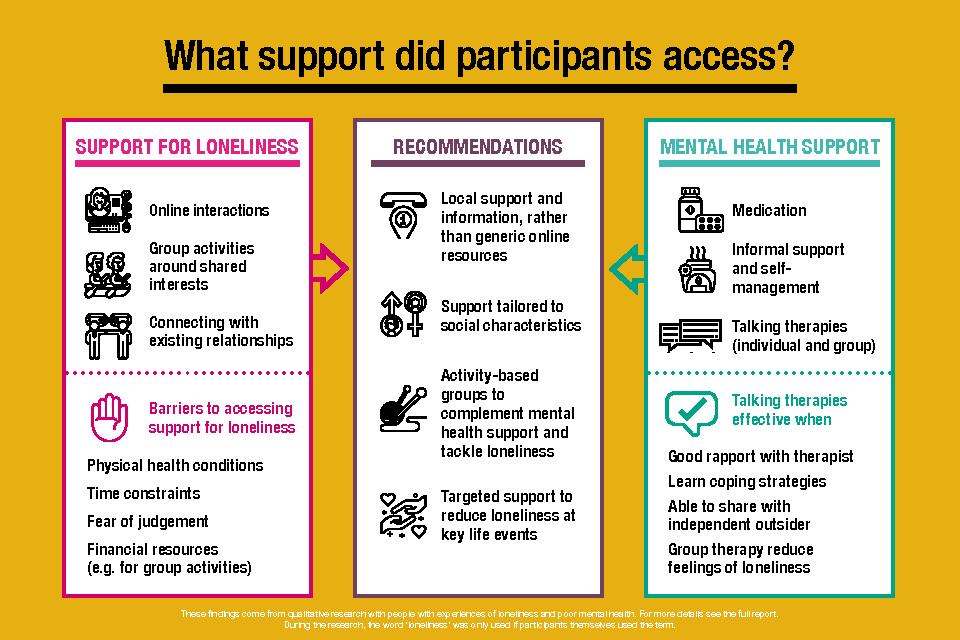

Participants had accessed a range of support for their mental health through formal health services. These services tended to concentrate on the treatment of mental health symptoms or conditions. There were few examples where services suggested specific support to tackle the loneliness that contributed to poor mental health, with mixed results in this respect. Instead, participants proactively sought out social support to tackle feelings of isolation themselves, through group activities or online interaction.

Participants made a number of recommendations about the way in which support could be improved. These were to:

- provide more local and tailored mental health support services in place of more generic online resources that participants found hard to navigate

- support group activities in communities around shared interests, including those tailored to personal characteristics e.g. faith, disability, gender, or sexual orientation

- provide mental health support that reduces feelings of loneliness and isolation organised around shared interests in activities (e.g. football, crafts, gardening), especially for people diagnosed with specific mental health conditions. These could be made available to people while on waiting lists for treatments

- establish community-based caseworkers who can help people navigate complex mental health services, signpost local support and group activities, and support participants’ families to understand mental health conditions, and how to respond to them.

These recommendations indicate that there could be an important role for the community and voluntary sector to play in supporting people experiencing loneliness and mental health issues. The wider findings of the study suggest that more initiatives to tackle loneliness could help to alleviate some mental health difficulties. These initiatives could be aimed at certain key moments in people’s lives (such as miscarriage, redundancy or retirement) which were associated with an increase in loneliness or deterioration in mental health, but were not associated with existing specialist support services.

Glossary

| ADHD | Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder |

|---|---|

| ASD | Autistic spectrum disorder |

| BAD | Bipolar affective disorder |

| BPD | Borderline personality disorder |

| CBT | Cognitive behavioural therapy |

| DCMS | Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport |

| GAD | Generalised anxiety disorder |

| Isolation | Social isolation describes an absence of social contact. This is an objective measure of the number of social contacts a person has |

| Loneliness | A subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship |

| NatCen | National Centre for Social Research |

| OCD | Obsessive compulsive disorder |

| Participant (research participant) | A person who reported currently being lonely who took part in the research |

| PIP | Personal independence payments |

| PTSD | Post-traumatic stress disorder |

| Purposive sampling | Purposive sampling is an approach to selecting research participants based on characteristics that researchers expect to affect views or experiences on the topic of the study |

| Professional stakeholder | Professionals with expertise in loneliness or mental health who were interviewed as part of the study |

| SAD | Seasonal affective disorder |

1. Introduction

This report presents the findings of a qualitative study commissioned by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) that aims to understand the relationship between mental health and loneliness across four key life stages: early adulthood (18 – 30 years old); parents with young children (with children aged 5 or under); middle-age (40 – 60 years old) and retirement.[footnote 3] The study forms part of a developing evidence base which will feed into the government’s work on tackling loneliness. This research consisted of two phases: interviews with professional stakeholders who were experts in the field of mental health and/or loneliness, and interviews with people who had past experience of mental health conditions and were experiencing loneliness.

1.1 Background to the research

The issue of loneliness and the need for effective policies to tackle it have been increasingly recognised in recent years. Building on the Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness[pdf], in 2018 the government launched a strategy for tackling loneliness[pdf]. One of the aims of this strategy is to expand the evidence base on loneliness, making a compelling case for action, and ensuring everyone has the information they need to make informed decisions through challenging times. Loneliness is associated with negative physical health outcomes, including earlier deaths, an increased risk of dementia, Alzheimer’s, heart disease and stroke.[footnote 4] Loneliness is also known to have an association with mental health conditions. For example, people reporting loneliness are more at risk of becoming depressed, and depressed people are more at risk of becoming lonely.[footnote 5] The government now recognises loneliness as one of the country’s most pressing public health issues.[footnote 6]

In 2021 DCMS commissioned an evidence review to identify remaining gaps in the existing evidence base. One of the areas noted in the report was a lack of research on the link between mental health and loneliness, as well as gaps in relation to how the stigma associated with mental health affects loneliness. It also recommended that future research explore loneliness across the life course, as well as how experiences of loneliness among key population groups results in poorer mental health.

Although the evidence review has shown that there is an important link between the experience of loneliness and mental health conditions, the nature of the relationship between the two is less well understood, particularly among groups at greater risk of loneliness. The evidence review found a bidirectional link between depression and anxiety and loneliness, and that loneliness is a predictor of worse outcomes in those with depression.[footnote 7]

A 2022 qualitative study found that participants reported a close connection between feelings of loneliness and their mental health difficulties, with poor mental health leading to feeling lonely and loneliness leading to a decline in mental health. Notably, for some participants this was a one-way relationship whilst others found it to be cyclical. The paper emphasised that strategies to reduce loneliness are more likely to be successful if rooted in an understanding of what people with mental health problems mean when they say they are lonely, and how this relates to feelings of mental distress. For instance, they found loneliness was associated with not feeling connected, lacking choice over being alone, not feeling loved, or not feeling understood. They also observed the role that stigma associated with mental health played in not seeking help, and others not providing it.

Certain life stages have also been identified for their heightened risk of loneliness and mental health issues. Much attention has been paid to loneliness in later life[pdf], with older people found to be at greater risk of loneliness, in part due to a perception that it is a part of getting older and not something that can be changed. Adolescence and young adulthood has also been identified as a key life stage at which people may be more likely to experience loneliness. The 2020/2021 Community Life Survey found that 11% of young people report chronic loneliness, compared to 6% of the general population.[footnote 8] This issue has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic[pdf]. Research has also found that middle age is a time associated with poor mental health, as suicide and attempted suicide are particularly evident among men in the 45-64 age group.

This research thus sought to respond to the evidence gap around experiences of loneliness among groups of concern who had pre-existing mental health conditions. For this research, the groups of concern were young adults, parents with young children, middle-aged people, and retired people.

1.2 Research aims

The overarching aim of the research was to investigate the links between loneliness and mental health, with an interest in different life stages (young adult, parents of young children, middle age, retirement). With this in mind, the research questions we aimed to address were:

- How do those with diagnosed mental health problems experience loneliness?

- To what extent does the social stigma associated with mental health conditions play a role in the experience of loneliness among this group?

- How do experiences of loneliness among those who have experienced mental health conditions vary by life stage?

1.3 Methods

This research consisted of two phases: interviews with professional expert stakeholders and in- depth interviews and diaries with people who were experiencing loneliness and had pre-existing mental health conditions.

1.3.1 Professional stakeholder interviews

In the first stage of the research, six 45-minute interviews were carried out with professional stakeholders. These included experts from mental health charities; organisations that support people at key life stages; and those working specifically on loneliness, including academics. Insights gathered at this stage were used to inform the design of the next phase of research as well as providing expert insights reported throughout this report. Detailed notes from each interview were captured using NatCen’s Framework approach.[footnote 9]

1.3.2 In-depth interviews and diaries

In-depth interviews were conducted with participants who had current or past experience of mental health conditions and currently reported being lonely.[footnote 10] Participants were sampled based on their mental health condition (depression; anxiety; other mental health conditions) and their life stage (young adults; parents of young children; middle-aged; retired). For more details of the sample, methodological approach and ethical considerations, please see Appendix A.

The interviews were conducted over the phone or via video call (depending on participant preference) and were 90 minutes long to allow time to build trust with the participant and fully explore their experiences. 37 interviews were conducted in total. These were then transcribed and analysed using the Framework approach.

14 of the participants who were interviewed also agreed to complete an online diary before their interview. They completed five diary entries documenting their experiences with mental health and loneliness over the course of two weeks. The insights were then used in the interviews to facilitate the discussion and generate richer insights into the fluctuations of feelings from day-to-day. Diary entries proved a helpful way of surfacing more mundane, daily occurrences that could affect mood, stress and feelings of loneliness.

1.3.3 Defining loneliness

DCMS follow the Campaign to End Loneliness and the Jo Cox Commission in defining loneliness as “a subjective, unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship. It happens when we have a mismatch between the quantity and quality of social relationships that we have, and those that we want”.[footnote 11] Loneliness is not the same as social isolation as you can feel lonely while surrounded by people. However, the two concepts are linked and can overlap.

In introducing the research and approaching the topic with participants, interviewers did not use the word ‘loneliness’ unless it was used by a participant first. This is because people have different understandings of loneliness and some people may be reluctant to use the word.[footnote 12] Instead, participants were asked about their feelings of connection to people in their social network. This allowed the discussion to be participant-led and to avoid any potential stigma attached to the concept of loneliness.

1.3.4 Limitations

The research adopted a purposive sampling approach in order to achieve range and diversity across the sample. The sampling approach included a focus on a number of primary criteria (mental health condition, gender, life stage) and also monitored secondary criteria (see Appendix A for full details). It was not possible within the sample to monitor and achieve diversity across all demographic criteria. As a result, the sample did not include any participants who identified as non-binary or trans. The research did not explicitly monitor sexual orientation or ethnicity, although this was reported by participants where relevant to the experiences under discussion. These limitations should be considered when reading the findings. Future research could explore in greater detail the specific experiences of loneliness and mental health among the LGBTQ+ community as well as among ethnic minority communities.

1.4 Report structure

The report is divided into the following sections.

- Chapter 2 describes the participants across the four key life stages including their experiences with mental health and how it affected their lives.

- Chapter 3 presents the main findings on how participants felt that loneliness and mental health interact.

- Chapter 4 presents findings related to how participants felt that the social stigma associated with mental health and loneliness impacts on their experiences of loneliness and affects their ability to get support.

- Chapter 5 explores how key life events affect experiences of loneliness and mental health across life stages.

- Chapter 6 explores the support and interventions participants accessed and provides recommendations on how these could be improved.

The report does not provide numerical findings, since qualitative research cannot support numerical analysis. This is because purposive sampling seeks to achieve range and diversity among research participants rather than to build a statistically representative sample. Instead the qualitative findings provide in-depth insights into the range of views and experiences of the participants in the study and verbatim quotes are used where relevant to illustrate these.

2. About the participants

This section provides a brief overview of the participants in the research. It starts by describing the mental health conditions experienced before exploring each of the four life stage groups in more detail (for more details on the sample please see Appendix A.

2.1 Mental health conditions

There were a range of mental health conditions represented across the sample. These included: depression, anxiety (taking different forms[footnote 13]), schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder (BPD), bi-polar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), seasonal affective disorder (SAD), and specific phobias. Participants reported both single and multiple conditions, and a number of more complex conditions (such as schizophrenia or borderline personality disorder) manifested through symptoms consistent with depression or anxiety. There was a range of experiences of diagnosis and treatment, from more formalised diagnosis with participants receiving talking therapies and/or medication, to self-diagnosis with no formal treatment in place. Experiences of mental health conditions tended to fluctuate with participants describing this as a ‘rollercoaster’. The sample included both those who reported currently experiencing a mental health condition as well as those who reported this as being in the past only.

Mental health conditions affected participants’ lives in a range of ways. Most obviously they manifested in symptoms affecting mood and emotions, including low mood, anger or irritability, crying, loss of joy, feelings of being overwhelmed or stressed, low self-esteem and negative self-talk. This could also lead to self-harm, suicidal thoughts or attempts. Experiences of hypervigilance, hallucinations, flashbacks, paranoia, mania, psychosis and dissociation were also reported, particularly among those with more complex or severe mental health conditions. Mental health conditions could also have physical effects, for example leading to chronic fatigue, insomnia, panic attacks or impact on diet. These symptoms could leave people unable to conduct daily activities such as being unable to work or study or unable to leave the house or travel. The severity of these impacts varied across the sample.

2.2 Life stage groups

Participants were from White British, White European, Black Caribbean, or South Asian backgrounds and fell into four life stage groups as set out in the sampling approach. This section provides a brief description of each of the four life stage groups.

2.2.1 Young adults

The young adult group included participants aged between 18 and 30. Participants were working or studying full- or part-time, or were not currently working or studying due to their mental health conditions. Participants also engaged with hobbies or other activities such as: going to the gym or playing football; online gaming; walking; taking care of pets; and playing musical instruments. This group tended to discuss greater use of online forms of socialising e.g. chatting online or making friends through gaming than other life stage groups. In terms of living arrangements, there were a range of situations, with people living alone, with a partner, with their parents, or in a shared house or student accommodation.

Among this group, mental health conditions were as varied as in the overall sample and included depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, BPD, PTSD, bipolar disorder. Participants also experienced some physical or neurological conditions such as migraines or ADHD.

2.2.2 Parents of young children

Participants in this group all had a child under the age of five in their household which was the defining criterion for this group. As a result, this included the greatest variety of ages from those in their twenties to those in their forties. Among this group, there were a range of different family situations, including: single parents living with their children; parents who were separated from their biological children and living with a partner and stepchildren; and those bringing up their children with their partners. Among this group, participants were either working full- or part-time, staying at home to take care of their family, or not currently working due to their mental health condition.

Once again there were a range of mental health conditions including depression, anxiety, PTSD with paranoia and specific phobias. Physical health conditions in this group included hypothyroidism, fibromyalgia and an arthritic condition.

2.2.3 Middle aged

This group of participants were aged between 40 and 60. Among this group there were a range of family situations including: single parents; those with partners and children; those with partners only; those who were single and did not have children. Relationships with children could also be complicated where children had disabilities, mental health issues or neurological conditions such as Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), or where participants were estranged from their children. Among this group, participants were working full- or part-time, or not working due to their physical health conditions. The latter group tended to be on disability benefits.

There were a range of mental health conditions experienced across this group including depression, anxiety, BPD and panic attacks. Participants in this group also experienced physical health conditions, some of which had started relatively recently and had a big impact on quality of life. These included colitis, neurological problems leading to chronic pain, past accidents at work, or illnesses/infections that had led to reduced mobility.

2.2.4 Retired

This group of participants included retired people of any age (all were over 50). Participants lived with long-term partners and/or grown up children or alone. Daily activities among this group included volunteering (for example in a local church or in an animal charity), caring for others, participating in arts and crafts activities (either alone or in a group), activities through the University of the Third Age and hobbies such as reading and walking.

Again, participants experienced a range of mental health conditions including depression, anxiety, SAD, and OCD. These had been experienced on and off over the course of people’s lives. Participants in this group were sometimes more reticent about talking about their mental health directly; instead using euphemisms such as being ‘low’ or being ‘blue’. Physical health conditions were common across this group and included: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disorder (COPD), high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, osteoarthritis and mobility issues, ulcerative colitis and heart disease.

3. Loneliness and mental health

This chapter presents the main findings on the relationship between loneliness and mental health. It begins by exploring how loneliness was experienced and described by participants. It then examines participant and stakeholder views on the relationship between mental health and loneliness, and the type and quality of social relationships that participants had. Finally, it looks at differences by demographic group in terms of how loneliness and mental health were perceived and experienced.

3.1 Experiences of loneliness

3.1.1 How loneliness was described

Participants across all groups and life stages were more likely to talk about not feeling close to and supported by others, rather than describing themselves as ‘lonely’. The words ‘lonely’, ‘isolated’ and ‘alone’ were more commonly used by participants in their written diary entries rather than during interviews. As noted in the introduction, interviewers only used the word lonely if participants themselves first used that word. Instead, participants were asked about their feelings of connection to people in their social network. When describing such connections, participants listed the people who they had contact with, the frequency of contact, and quality of the connection. As a result of this approach, it was not always possible within the study to differentiate between experiences of isolation and feelings of loneliness.

When describing a lack of connection to others, participants spoke of: not feeling close to or supported by family or friends; not having close friends or people they could talk to; not going to social events or enjoying mixing in groups of people; and spending a lot of time alone. Participants also described themselves as ‘a bit of a loner’ or ‘shy’, in some cases, despite having wide social networks such as a large extended family.

Loneliness, or a lack of connection to others, was generally described not as about the number of connections an individual had, but about the quality of connection. Participants spoke of feelings of distance, rejection or not being understood by those who they wanted and perhaps expected to feel closer to, such as close family members or a partner. A lack of connection with and emotional support from such individuals prompted feelings of loneliness.

I tried to see my great granddaughter who is 1 year old and my granddaughter always has an excuse to put me off (…) I love them both but find it difficult to have a closeness with them (…) My partner wasn’t in the best of moods and seemed rather distant. He apologised but I don’t feel very close to him at present (…) [I] feel a bit lonely.

– Female, retired, depression - diary entry

Conversely, a good connection with others was described not as having lots of social connections but as having someone who they could ‘talk to about anything’ or rely on when they needed emotional support.

3.1.2 How loneliness was experienced

There was a spectrum of experiences of loneliness, from those who were more isolated to those who were more socially connected. At one end of the spectrum were those with no social network, who felt that they had no friends at all, no social life, and no one they could depend on for support. Their social interaction was very limited, for example, only with colleagues at work, or an adult child who they did not see often. This group’s sense of loneliness was typically long-term, and something they had come to accept as their way of life. Depression was the most common mental health condition experienced by participants in this group, who also tended to be in the middle aged and retired life stages. As discussed further in section 3.2, depression and other mental health issues were explicitly linked by participants to long-term loneliness.

Further along the spectrum were those with a low level of social connection. They had a select few people who they trusted and could confide in, often a friend or partner. Their support network had some understanding of their mental health issues and how it affected them. This allowed the participant to feel connected to and supported by them. This group was likely to ‘often’ feel lonely, but also experienced moments of connection with and support from others which alleviated their loneliness to some extent. This group included participants across all life stages and with a range of mental health conditions.

At the other end of the spectrum were those who had wider social networks and were more socially active. Their social network could include friends, a partner or spouse, adult children, siblings and parents. This group was more likely to seek out social contact. This could include seeking support with their mental health issues, and involving themselves in social events. However, periods of loneliness experienced by this group correlated with periods of poorer mental health.

Sometimes I feel absolutely fine…you’ve got your family, you’ve got people you see on the beach…a WhatsApp group of old friends…but other times I feel quite isolated really.

– Male, retired, OCD and depression

Participants with anxiety and depression were more prominent in this group than participants with other mental health conditions, and it included people in all life stages.

Stakeholders suggested that experiences of loneliness varied by the type and severity of mental health conditions. Moreover, they suggested that someone with severe mental illness would be less likely to be able to transition out of loneliness than someone with a less severe mental health condition. Although this trend was not evident in our sample, the severity of participants’ mental health condition was defined subjectively by participants themselves, rather than based on clinical definitions that stakeholders would use.

An image illustrating the spectrum of loneliness that participants in the research experienced, with the number of quality of relationships affecting how lonely people felt.

3.2 Views on the relationship between loneliness and mental health

There was a strongly-held view among participants and stakeholders that mental health issues and loneliness are closely intertwined. Although it was considered possible to feel loneliness without experiencing poor mental health, loneliness was considered to increase the risk of mental health issues and, conversely, mental health issues were considered to have a significant impact on feelings of social isolation and loneliness. Stakeholders were of the view that loneliness and depression or anxiety increase in tandem and that loneliness can be experienced as part of a mental health condition, with sufferers often unable to differentiate one from the other. Further, the relationship was perceived by both participants and stakeholders to be multidirectional; that is, poor mental health could lead to loneliness, and vice versa.

3.2.1 Views on how loneliness and mental health are linked

As discussed, the relationship between mental health and loneliness was considered to be bidirectional.

Mental health issues leading to loneliness

Participants and stakeholders identified various patterns of thought and physical symptoms of mental health issues that linked to loneliness. Some of these were related to the way in which participants considered themselves to be perceived negatively by others, such as:

- Low self-regard. Participants with mental health issues tended to have low self-regard and expected others to perceive them in the same negative light.[footnote 14] For example, they perceived their mental health issues to mean that they were a failure, weak, miserable, boring, or not fun to be around, so they opted to isolate themselves instead. One participant described in her diary how she was ‘dreading’ a weekend away with friends due to fears that others would perceive her negatively.

Not looking forward to packing for the weekend, to be honest I’m not looking forward to going at all. Everyone else (…) they’re going to think I’m boring (…) Absolutely dreading tomorrow.

– Female, middle aged, depression - diary entry

There were participants for whom the onset of their mental health issues had been sudden, and they felt that their personality had changed significantly at the same time. They grieved for the person that they used to be, who they felt was a more desirable person for others to spend time with. Participants who experienced paranoia also found that this aspect of their mental health acted as a barrier to social connection, because of their negative expectations and perceptions of how they were perceived by others.

- Fear of stigma leading to social withdrawal. The fear of being judged by people who do not understand their mental health condition acted as a barrier to participants talking to others about and asking for help with their mental health (discussed further in Chapter 4). Participants expected that others would not believe or understand how their mental health issues affected them, and so avoided social contact to protect themselves from critical judgement. Stakeholders echoed this view by describing people with mental health conditions who ‘get stuck not trusting anybody’.

Other thought patterns were underpinned by concerns around negative consequences of revealing their true feelings to others, including:

- Not wanting to be a burden on others. Participants felt that if they told someone how they were feeling, that person would feel worried, sad, or stressed, and they did not want to make those they cared about feel that way. Additionally, there was a perception that other people did not want to know about their mental health issues, either because it upset them too much, they did not know how to help, or they just did not want to know. This prevented participants from making contact with others or telling them how they were really feeling. Furthermore, participants perceived others to have ‘more serious’ problems to deal with than their own mental health struggles. So instead of sharing, participants kept their difficulties to themselves, which enhanced their feelings of loneliness.

- Needing to mask true feelings. The sense of pressure to not talk about their struggles for fear of being a burden or being judged, could also make participants feel that if they did interact with others, they had to mask their true feelings and pretend to be ok. However, this pretence was exhausting and unsustainable, and led to participants opting out of social interaction.[footnote 15]

I’m conscious that I haven’t given my mum a ring this week and I feel guilty about this…I just haven’t been able to put on the usual act from my end- I’m ok act. (…) Trying to hide how miserable I’ve felt has been too hard.

– Female, middle aged, anxiety and depression - diary entry

Alternatively, if participants did interact with others while pretending to be ok, this compounded both mental health issues and feelings of loneliness as, not being their true selves, they could not feel genuinely connected to others.

Mental health issues could also limit individuals’ capacity for social interaction in the following ways:

- Mental health conditions limiting ability to support others. Participants felt that mental health thwarted their capacity to be a ‘good friend’. For example, not being able to predict when their mental health would vary meant that they sometimes had to cancel social arrangements at short notice. Participants felt this made them unreliable, which precipitated feelings of shame and guilt. This in turn worsened their mental health. Poor mental health could also make it difficult for people to be supportive of others, as their mental health struggles could be all-consuming. For example, those with anxiety explained that their thoughts and worries would take up all of their mental energy. Furthermore, physical symptoms of mental health issues, such as headaches, nausea and fatigue, could be distracting, so that they were unable to be fully present for another person. The overall effect was that people withdrew from social contact, thus increasing their sense of loneliness.

Today I was glad I was alone, I felt distant and conflicted… even when my girlfriend phoned me I wasn’t really there, I wasn’t listening. To be honest I wanted the phone call to end as soon as possible, it’s not that I don’t care what she had to say but I couldn’t even if I tried. I had no motivation or energy to do so.

–Male, parent of young child, depression - diary entry

- Feeling overwhelmed in spaces for socialising. Participants with BPD and schizophrenia described feeling ‘overwhelmed’ in crowds or busy public places. This meant they were unable to engage in social activities in public places such as meeting friends in a shopping centre. Feelings of being overwhelmed caused participants to ‘shut down’ so that they felt unable to interact with others.

Furthermore, mental health issues could inhibit an individual’s desire for social connection with others by giving them a distorted, overly negative view of other people:

- Mental health issues could induce negative perceptions of others. There were participants whose depression gave them a distorted view of others, so that they viewed others more negatively, or became less tolerant of or angry towards others when depressed. One participant with depression explained how he was unable to identify the influence of depression on his thoughts and feelings during a depressive episode. Instead, he would believe that his negative thoughts towards others were rational. This led him to shun contact with those who he felt negative towards, thus increasing his isolation.

The mind never accepts that it’s ill…it will put anything as a reason for you feeling bad in place of it. You are feeling that way because your family are not nice to you…you sort it out by cutting yourself off from what you imagine could be the problem…the person that you’ve been friends with all your life.

– Male, retired, depression and anxiety

There was a view among stakeholders, supported by findings from participants, that there were similarities in the way that people with loneliness and people with depression behaved, such as social withdrawal and brooding. Stakeholders explained that loneliness, like depression, affects how individuals feel about their social relationships. This means that they are more likely to think negatively about social interactions, take slights more seriously, or brood on things that have gone wrong during an interaction.[footnote 16]

One stakeholder illustrated how the way in which someone with a mental health condition perceives situations could prevent them from transitioning out of loneliness. They explained that, if an individual experienced an event that brought about loneliness, such as bereavement, moving to a new area, or retirement, there were two potential ways in which that person could respond. The more helpful response would be seeing the cause of feelings of loneliness as an external event and trusting that things would improve over time. A less helpful response would be seeing the experience as part of your identity, and therefore how your life would continue to be long-term, which would increase the likelihood of experiencing chronic loneliness. This idea, referred to as the locus of control, has been explored extensively in psychological academic literature in relation both to loneliness and mental health more generally.[footnote 17]

Loneliness leading to mental health issues

Conversely, participants had experiences of loneliness leading to poor mental health. Relationship breakdowns, poor physical health, lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, and retirement, had brought about periods of loneliness which triggered mental health issues. For example, a young man who developed a disabling and painful physical condition in his early twenties was suddenly unable to go out to socialise with friends, who gradually stopped visiting. This period of sudden isolation triggered his first episode of depression. During such periods of isolation, participants described having ‘fallen out of practice’ in social skills and, consequently, had lost their social confidence.

Furthermore, participants described how negative emotions and thoughts became more intense as they endured prolonged periods of loneliness, which precipitated poor mental health.

[Isolation during the pandemic meant my feelings were] building up and got to the stage where you start dwelling on negative thinking…and it’s got to a stage where it’s exploding.

– Male, middle aged, anxiety and depression

Without the distraction of company, participants explained they were more likely to ruminate on their worries or think about traumatic events in their past, which worsened their mental health.

Not connecting with others…allows all sorts of imaginings and irrational thoughts…being really introspective, but at least if you’re mixing with people you’re not constantly thinking about your worries and ailments and your fears.

–Female, middle aged, depression

In addition to being a helpful distraction from distressing thoughts, socialising with others gave people a sense of purpose and motivation. In the absence of company, participants were more likely to feel despondent.

I am always able to meet up with friends which tends to be positive. It’s when I’m home alone where I note I lack drive (…) I find myself moping around, feeling tired and napping in the afternoon.

– Male, retired, SAD - diary entry

The link between loneliness and mental health was considered to be cyclical, and it was therefore difficult for participants to identify which factor they had experienced first. For example, mental health issues could make relationships more difficult to sustain, which prompted relationship breakdown, causing feelings of loneliness, which triggered a worsening of mental health, which led to further loss of social skills and capacity to interact with others.

A visual showing that the relationship between loneliness and mental health was bi-directional, with loneliness leading to poor mental health and mental health issues leading to loneliness.

3.3 Type and quality of social relationships

It was emotional support rather than any other type of support that constituted a high-quality social relationship in the views of participants. The people who participants felt connected to were typically those who they felt understood, at least to some extent, their mental health issues. While participants did have others who provided them with practical support, such as help with childcare or accommodation, this did not make them feel ‘close’ or connected to that person unless they also provided emotional support.

As discussed earlier, there were three groups of participants on a spectrum of loneliness. Those who were most lonely (who tended to be in middle aged or retired life stages) described themselves as having no friends or people they could connect with.

I don’t do friends…I would say I’m not connected with people at all. It is because I don’t have the willpower to connect with people. I don’t trust people. The other issue is that I just don’t have time for other people

– Female, middle aged, depression

While participants in this group might have people they associated with, such as work colleagues, they did not have a close connection they could rely on for emotional support. There were participants in this group who felt close to an adult child, but these relationships were described as more supportive of the adult child than of the parent. That is, while the parent felt their child would talk to them about anything, they did not necessarily confide to the same extent, due to a reluctance to burden or worry them. This group included individuals who lived with a spouse or partner, but whose partner did not support them with their mental health. This furthered a sense of disconnection and isolation, as participants felt particularly alone when those who they were supposed to be closest to were unsupportive. This group lacked a connection with someone who they could confide in, who would show some understanding of their mental health, and provide emotional support.

The second group (which included participants across all life stages) had a small number of social connections who they felt close to. This could include a partner, a close friend and, among young adults more commonly, a sibling or a parent. Participants had made close friends in the workplace, online, or had close friends from childhood who they had known for many years. A sense that the other person knew and accepted their true selves, including their mental health issue, was a key constituent of a good quality relationship. This allowed participants to feel they could be ‘themselves’ when with that other person, confide in them, and not have to excuse or explain their behaviour. Talking to and spending time with these close others was a key protective factor for those with mental health issues. The social connection had a positive impact on their mental health, and talking to others about their mental health issues had, in some cases, encouraged participants to seek help from professionals.

However, support from such a small number of contacts had its limitations. Participants might not have contact with their trusted others often or at times when they really needed their support. Or, when they did have contact, they might not disclose the full extent of their mental health struggles for the reasons described in section 3.2.1, such as a fear of burdening them. Despite having close connections with others, their mental health issues could act as a barrier to reaching out to ask for support when they needed it.

The third group (which included participants across all life stages) had a wider social network which might include a partner, friends, colleagues, and family members. This group was more comfortable with group social situations and enjoyed social contact more unreservedly than the other two groups. However, during episodes of poor mental health (most commonly depression or anxiety), they lacked the quality of connection and support that they needed. For example, one participant experienced loneliness after her marriage broke down. Even though she described herself as ‘very, very social’, she felt isolated and alone with overwhelming responsibilities as a single parent.

As a single parent with teenage children with additional needs I worry about everything (…) It would be good if I had someone other than my oldest son to talk to about my worries. There’s no-one really.

–Female, middle aged, anxiety and depression – diary entry

A young adult in this group also described herself as a sociable person with a strong support network of family and friends, but experienced loneliness sometimes due to not having a partner.

Moreover, there were participants in this group who, despite having a wide range of social connections, found it difficult to trust people, so they struggled to make deeper connections with others. Instead, they had a number of more ‘surface level’ friendships, to whom they did not disclose the full extent of their mental health struggles.

Other factors that influenced participants’ social relationships included:

- An aversion to social interaction in groups and with strangers. It was common for participants in the more isolated groups (those with no or low-level social connection) to have an aversion to groups of people and social interaction with people they did not already know. Group situations could make participants feel stressed, anxious, threatened or overwhelmed, so there was a preference for social interaction on a one-to-one basis. Going on a group outing with people they did not already know was particularly daunting. One participant who had been offered a lift from a befriender to take them to a group event had not accepted the lift because she had never met the befriender before.

- A preference for online rather than face-to-face social interaction. There were participants who explained that they found it easier to interact with others online than face-to-face, particularly when experiencing periods of poor mental health. They felt that by not seeing the other person when talking online, they were less likely to be judged or critically appraised by the other person. In some instances, participants had formed close relationships with friends online over many years, and they considered the relationships to be of high quality.

- Friends had ‘fallen away’ with the onset of participants’ mental health condition. In some instances, this was interpreted by participants as their friends not being able to cope with their mental health issues, and the overall effect was increased isolation. Discord or relationship breakdown with family members was also a prominent feature of participants’ lives, with adult siblings or one parent who participants rarely, if ever, had contact with. It was also rare for older, retired participants to have sustained once-valued friendships from their youth. For example, retired army personnel spoke of having lost contact with close friends who they had been in the army with.

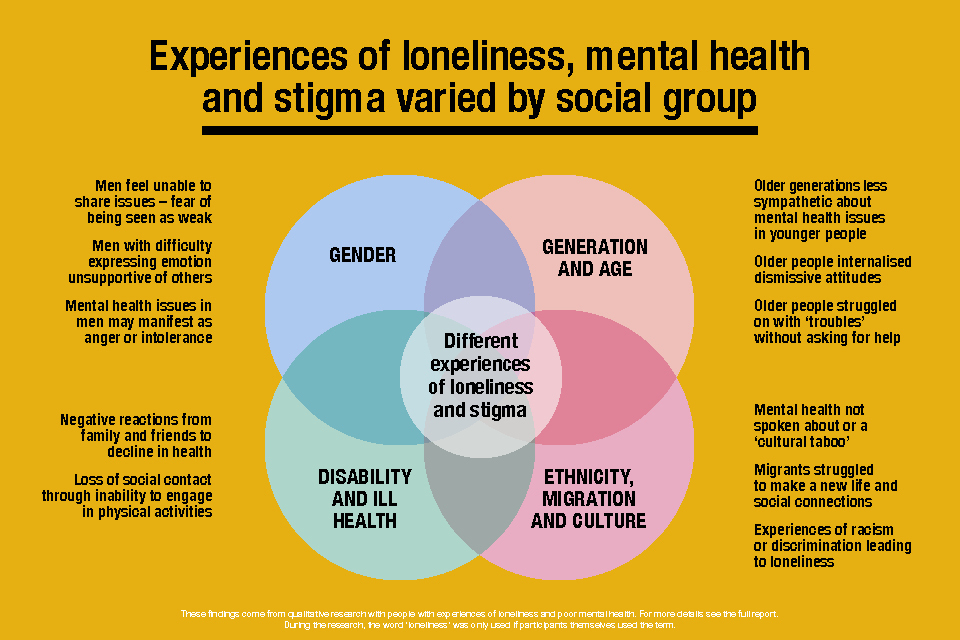

3.4 How experiences of loneliness varied across demographic groups

A number of demographic factors appeared to influence perceptions and experiences of loneliness and mental health, including ethnicity, sex, age, sexual orientation and physical ill health or disability. Some of this was linked to different experiences of stigma which is discussed further in Chapter 4.

3.4.1 Ethnicity, migration, culture and religion

Ethnicity was highlighted by both participants and stakeholders as a key factor influencing experiences of mental health and loneliness. Participants from ethnic minority groups highlighted their cultural backgrounds and upbringing, in which mental health issues were either not recognised, not spoken about, or minimised. Some saw this as wanting to play down traditional links, and shame, associated with the idea of ‘craziness’ or ‘madness’ in the family. Others, however, emphasised the struggle of first-generation migrants trying to make a new life for their family, to make friends and to fit in. One participant felt that in her South Asian community, women were expected to be fully competent in carrying out their responsibilities and were not allowed to say they were feeling unwell or were anything less than capable.

[In the Asian community] you cannot be mentally ill…There’s nothing called mentally ill

– Female, parent of young child, depression

In addition, participants from ethnic minority groups recalled experiences of racism, which had led to feelings of separation and isolation from others and low self-esteem. Echoing this, stakeholders noted that black men are disproportionately likely to be diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia than white men, and considered there to be a link between experiences of racism and paranoia.

There were participants who had immigrated to the UK as adults and had found it difficult to make social connections since arriving in this country. They had found the cultural and language barriers particularly difficult to overcome while also experiencing poor mental health. Similarly, stakeholders identified international students as a high-risk group for experiencing loneliness.

While not necessarily linked to ethnicity, religion could also play a role in delaying seeking spiritual or professional help, as participants saw their mental ill-health as a test from God that they needed to overcome themselves.

3.4.2 Sex

There were apparent differences by sex in how mental health and loneliness were experienced by participants. Male participants were more likely than female participants to think that society perceived mental health issues as a sign of ‘weakness’. This prevented them from disclosing their mental health struggles to other men, for fear they would be judged as less strong than men without mental health issues who were seemingly coping better than they were. Middle-aged and older men with a variety of mental health conditions were told to ‘man up’, and embarrassment about showing feelings to others, particularly to other men, set in from an early age. They were more likely to disclose and discuss their mental health issues with women rather than men. Two younger male participants had received help for emotional or psychological difficulties at school, but said they felt embarrassed to let their ‘mates’ know because of how they might view them. Some male participants said they would only talk about their feelings to a partner or dispassionate professional such as a GP or therapist.

Further, depression in male participants was more likely than depression in female participants to manifest as anger, irritation and intolerance towards others. The way in which expectations about being a ‘man’ affected the ability of men to express emotion, or to empathise with others experiencing psychological difficulties, also affected the women with whom they interacted. Female participants told us that their husbands or male relatives (e.g. father, husband) had been unsupportive, mocked them, or dismissed their feelings out of hand. In some cases, this had left female participants struggling with post-natal depression or suicidal thoughts by themselves.

Male participants were as likely as female participants to want a close emotional connection with others, someone who they could talk to and disclose their mental health struggles to and feel understood by. However, when describing their social connections, men were more likely to describe social activities they engaged with, such as going to the pub, cycling or playing golf with friends. In contrast, female participants were more likely to describe the relationship they had with close others, rather than describe activities that they did together.

Female participants were more likely than male participants to feel socially isolated and suffer poor mental health due to a lack of support with raising their children. However, male participants were more likely than female participants to have children from a past relationship who they no longer lived with. Not being able to spend enough time with their children was a key source of emotional pain for these fathers.

Missing my son has been the hardest experience of my life, I miss him every moment of every day. I have him every other weekend but it’s hard to connect with him, I don’t want to get used to him being there just for him to go again…it hurts so much to see him go. On Sundays before he goes home I almost completely shut down in preparation for him to not be there again.

– Male, parent of young child, depression and anxiety - diary entry

Other differences by sex included that there were female participants who had experienced violence from a male perpetrator who were now afraid of male strangers, particularly men showing aggression in public. This made them more reluctant to go out in public. This had been particularly acute for one participant who experienced what she referred to as a mental breakdown and was diagnosed with BPD after she experienced a sexual assault in her early twenties. After this point, she had not returned to work and her loneliness had increased.

3.4.3 Age

Younger participants said that they had parents, grandparents, or had encountered other older people who were less sympathetic in their views about mental and emotional struggles than they or their peers. These older people told participants who sought help from them to “get over it”, “go for a walk” or to find something to ‘distract’ them from their worries. Participants of all ages who encountered these views among older people tended to avoid further disclosure to them. Some older participants also appeared to have internalised the idea that they should get over their problems themselves. They tended to play down the symptoms of their mental health conditions as just ‘troubles’, ‘grumbles’, or unexplained feelings of anger, irritability or loss of joy.

3.4.4 Sexual orientation

Stakeholders reported that LGBTQ+ groups were more likely to experience loneliness as a result of social discrimination, whereby micro-aggressions would act as a reminder that they were not accepted in society. Echoing this view, a homosexual participant recalled a long history of poor mental health and loneliness due to experiencing discrimination for being ‘different’. He had struggled to come to terms with his sexual orientation during adolescence and had continued to struggle to find a partner since, which he felt was a key contributor to his loneliness. As the sample did not include participants from other LGBTQ+ groups, it was not possible to explore their specific experiences in this study.

3.4.5 Physical disability and ill-health

Mental ill-health was often associated with physical ill-health, especially where participants were in pain due to debilitating conditions (e.g. migraines, neurological conditions, ulcerative colitis) and/or had limited mobility. Difficulties arose where these problems were not treated together in a holistic way. Physical ill-health affected participants’ ability to engage in social activities organised around sports or socialising in public. This resulted in participants feeling more isolated. Disabled participants also said they felt that other people were shocked at their physical decline or weight change. They described feeling left at home by themselves, while partners, family or friends went out without them. However, they also felt guilty about asking partners or friends to change their plans to involve them. They felt that they could not share how the physical changes also affected their mental health leading to them feeling more lonely.

A diagram illustrating how experiences of loneliness, mental health and stigma varied by social group including based on gender; generation or age; disability or ill health; and ethnicity.

4. Stigma, mental health and loneliness

This chapter explores participants’ views on the stigma associated with mental ill-health and loneliness; how experiences of stigma produced or reinforced feelings of isolation and loneliness; and the effects this had on participants’ ability to seek help and support.

As highlighted in Chapter 3, mental health issues could lead to loneliness where people felt that they could not reveal their true feelings or struggles to others and so were unable to get emotional support from their social connections. Part of what prevented people being able to share their experiences was fear of the stigma associated with mental health conditions. This could relate to fear of the reactions that participants expected to receive from others or their own internalised stigma that their mental health issues were not worth sharing. This lack of feelings of closeness with those they expected or hoped to be understood by increased their feelings of loneliness.

Feelings of loneliness were also associated with stigma. This shared common features of shame, judgement and fear of negative consequences with the stigma associated with mental ill-health. The stigma attached to loneliness was often intertwined in participant accounts with the stigma associated with mental ill-health and was difficult to separate analytically.

4.1 Participants views on stigma

Participants identified stigma associated both with mental health conditions and symptoms, but also with loneliness. The form of expression this stigma took varied slightly between mental health and loneliness, although both were experienced in the common context of shame, embarrassment, and the fear of negative judgements by others.

4.1.1 The stigma associated with mental ill-health

Participants thought there was increased discussion of mental health in society, but that stigma associated with mental health conditions remained. Stigma associated with mental health was experienced as the dismissal of mental ill-health as ‘not real’, the trivialisation of the struggles people faced, and themisunderstanding of mental health conditions, their symptoms and effects.

Depression and anxiety were regarded as being more widely discussed in public than other conditions and this was believed to be because of the millions of people suffering from them. The COVID-19 pandemic, and the effects of lockdown restrictions, were considered to have put mental health and well-being, and the need for social connections, higher up the public policy agenda. However, participants felt that increased discussion of mental health did not automatically lead to greater understanding or acceptance of mental health conditions. Participants across all life stage groups thought that it is difficult for people who had not experienced mental ill-health to understand its debilitating or challenging effects, in part because the concept of illness was still framed in physical terms.

Participants identified different facets of the stigma associated with mental health conditions, all of which could lead in different ways to increased feelings of loneliness or people withdrawing from social contact.

- Weak or soft. As noted above, participants talked about how mental ill-health is viewed differently from physical ill-health. While there was acceptance that physical ill-health may affect one’s ability to do day-to-day activities, some participants said that others perceived mental ill-health as making them ‘weak’ or ‘inadequate’ overall, or that it made them unable to deal with everyday life at all. Participants across the different life stages regarded these views as being particularly present among older generations. Younger participants thought older people saw them as ‘soft’.

- Incapable or unreliable. Participants who were working said they felt that some employers viewed people experiencing mental ill-health as incapable or less reliable than other workers who did not experience poor mental health, sometimes based on personal experiences of these attitudes. Some participants said people had questioned whether they were making a real effort to do things or whether they were ‘just lazy’.

- Attention-seeking. Accusations of this kind were particularly levelled at participants who had told others that they had suicidal thoughts. They were told that, if they were ‘really’ suicidal, they would have just killed themselves. Where participants had attempted suicide, they were criticised for not having revealed how they were feeling sooner. This was sometimes despite their previous experiences of being told they were over-playing the problems they were facing.

- A burden or worry. This especially related to the worry of ‘being a burden’ to parents, children, or friends with whom the participant socialised or relied on otherwise for social connection. Participants with conditions ranging through anxiety, depression, BAD, PTSD, and psychosis, sometimes played down their illness, saying symptoms were a ‘blip’. They also withdrew from social contact so that people would not ‘fuss over’ them.

- A ‘downer’. Participants said that they thought other people did not want to be around them or spend time with them because they would be a ‘downer’. This word was especially linked to people with depression or other conditions with depressive elements, suggesting they lowered the mood of other people around them due to their own low mood. Some people with longer-term clinical depression would withdraw socially when they recognised symptoms coming on so as not to bring their family or friends down.

Today I feel down. I want to shut myself off from people. I can’t see the point in telling others how I’m feeling because it just brings them down with me.

– Female, retired, depression – diary entry

In another example, a participant described the way in which people ‘peeled away’ from him when he was depressed.

Although participants noted an increase in the discussion of mental health in wider society, some felt that the societal discussion was ill-informed. Participants pointed to the role of ‘influencers’ in promoting discussion about mental health, particularly, celebrities or sports people who are widely admired. They felt that some celebrities had jumped on the ‘bandwagon’ of mental ill-health, thereby diminishing the experiences of people who really suffered. In particular, some people had begun to mistake everyday changes in mood or anxieties as symptoms of mental health conditions. Participants emphasised the distinction between everyday anxiety or feeling a bit sad, and anxiety that prevents people being able to carry out everyday tasks, or depression that can lead to total isolation from others and suicide.

4.1.2 The stigma associated with loneliness

The stigma attached to loneliness was evident in the way that some participants wanted to avoid the term all together. Instead, they preferred to talk about feeling ‘isolated’ or ‘alone’, or not having the social or emotional connections as described in Chapter 3.

Admitting the need for social connection was considered intimate and potentially embarrassing to the person making the disclosure and to the person hearing it. There was a concern about appearing sad, needy or desperate. Participants who felt this way feared that, by revealing that they were lonely, friends, work colleagues, family or neighbours would see them as inadequate, socially or emotionally, and might avoid or reject them. A participant who had retired early expressed this through his disappointment that work colleagues who he thought of as friends did not keep in touch.

I lost contact with all these clients that I used to see on a regular basis, all the work people I used to see on a regular basis… You can’t be the sort of person that’s always going back into the office… You can’t do that sort of thing, so I guess I just thought better just to break away… not really have any contact.

– Male, retired, OCD

In another example, a retired female participant described feeling that it could be better to have a mental health condition than to be single or widowed in social situations, as you received less support for being alone. This was in part due to the fact that much socialising was done in couples, and so single people were less likely to be included.

Another notable theme across participants was that their mental health conditions made establishing and keeping relationships and friendships more difficult. Where anxiety prevented participants from socialising, or low self-esteem made them feel they were ‘not good enough’ to be around other people, the perception that other people viewed them as ‘sad’ or ‘needy’ was perpetuated.

A recurring theme was that participants often held back from saying how they really felt when others asked them for fear of embarrassing others and themselves. It was notable that some participants went further in describing the depths of their loneliness in their diary entries prior to being interviewed, than they did in their interviews. Discussion of feeling lonely was also often the part of the interview during which participants became most upset. Where participants were prepared to say they felt lonely, there was still a sense of embarrassment to saying it. It is likely that this impacted on participants’ ability to reflect on and explicitly talk about the stigma associated with loneliness. It is also notable that there is much less societal discussion about the stigma associated with loneliness.

4.2 Consequences of stigma

Stigma associated with mental health conditions manifested in other people’s reactions of dismissal and trivialisation to participants. This also applied to signs of mental ill-health arising from feelings of loneliness, or the consequences of mental ill-health that were made worse through depression, anxiety and tendency to isolate from others. The stigma associated with mental ill-health and loneliness could also be internalised as feelings of shame or embarrassment, making participants hesitant to ask for help and support.

4.2.1 Stigma resulting in dismissal and trivialisation

Stigma linked to mental ill-health and symptoms was experienced through the way that participants felt that their feelings and struggles were dismissed or trivialised by others. Trivialisation of participants’ feelings and struggles was reported in the way that others dismissed their symptoms, condition or circumstances as:

- not having real effects on their lives

- being something they could control if they wanted to, and/or

- being just expressions of feelings or circumstances that everyone had to deal with

There were instances reported in which family members, friends, work colleagues, managers and employers had openly stated that they did “not believe in mental illness”. Alternatively, their experience of how badly others with mental health conditions or symptoms were treated, meant that participants felt they had to hide significant difficulties they were experiencing, or what they considered substantial parts of themselves.

Another guy I worked with very closely… had a complete nervous breakdown in the middle of the office. We never saw him again… Seeing how people deal with it, if you’re suffering it for yourself, the last thing you’re going to do is let any of them buggers know!

– Female, retired, depression and anxiety

Participants discussed only revealing how they were feeling for the first time when they were at their most desperate. But even in these instances, they received mixed, ill-informed or patronising responses. Common responses were: “everyone feels down or anxious sometimes”, or that they “just needed to get on with life like everyone else”.

As a result, participants could be left feeling frustrated that people were not trying to understand them, which made telling people in future even harder. A middle-aged participant working full-time, who had lived with depression since his teenage years likened trying to get people to understand how he was feeling to “screaming in a room full of people” where “everybody’s got ear defenders on”:

You want help so badly, but no one can hear the message that you’re trying to get across. (…) Then you find it so hard to do it the second time or the third time

– Male, middle aged, depression

Repeated experiences of dismissal, trivialisation and misunderstanding meant participants felt shamed or embarrassed about revealing their feelings leading to greater feelings of loneliness.

4.2.2 Internalisation of stigma

Echoing the discussion above, stakeholders also discussed the role of stigma in affecting peoples’ experiences of mental health and loneliness. This was particularly through the way that social stigma can be internalised psychologically. This could be through:

- shame or embarrassment

- the fear of rejection or negative consequences

- the burden or worry that revealing that they are struggling, or lonely, may bring to others

This internalisation was reflected in interviews where participants avoided talking about their feelings of loneliness. Among retired participants, internalised attitudes about mental health issues not being ‘real’ were also evident in euphemisms they used to describe and downplay how they were feeling. Even where participants knew they needed help, they would often not ask for it or take up offers of help. This was because they worried about rejection later, or that they would be a burden to others.

4.3 Effects of stigma on ability or willingness to seek help

Experiences of stigma or internalised stigma associated both with mental health and loneliness could impact participants’ ability or willingness to seek help or affect who they sought support from.

4.3.1 Delaying seeking help

The powerful effects of stigma, and its internalisation through shame, meant some people did not reach out to friends or family, or seek formal help at all, or delayed doing so until their condition or circumstances significantly worsened (e.g. leading to a serious mental breakdown or suicide attempt). The effect of stigma was particularly marked among some groups or circumstances. For example, middle-aged and retired men talked about “getting on with it” or struggling on with problems until they got worse. The shame or embarrassment of feeling lonely or isolated as a young mother, or a disabled person with mobility issues, also made it difficult to reach out for help.

Participants were put off seeking help where their initial, tentative requests were dismissed or trivialised, which meant they remained undiagnosed and/or struggling with feelings and symptoms they did not understand. This was particularly true for young adult participants, who did not understand what they were going through until a crisis brought them in touch with mental health services.

4.3.2 Selective disclosure and signposted support