Mapping the Species Data Pathway: Connecting species data flows in England - Executive Summary and Technical Summary and Recommendations

Published 25 May 2021

Applies to England

Executive Summary

The UK Geospatial Strategy sets out a commitment for the Geospatial Commission to identify how improved access to better location data can support environmental outcomes. This is part of Mission 2 in the strategy, to improve access to better location data. To support this mission, the Geospatial Commission’s Data Improvement Programme has sponsored this study to look at the costs, benefits, and management of species data in England. It presents options to make species data more consistent, joined up and accessible for end-users by encouraging FAIR data principles.

High quality, current and accessible species data are essential to underpin environmental policy and land use planning. Implementing and evaluating outcomes from the Environment Bill, Biodiversity Net Gain and the new Environmental Land Management Scheme (ELMS) will depend on access to high quality species baseline and monitoring data. Species data tells us about the diversity of natural assets, which is associated with greater resilience (Dasgupta Review, 2021).

The current species data pathway in England enables a large amount of data to be recorded and shared. The current system utilises extensive volunteer input and is reliant upon continued good will and interest. The system has evolved ad-hoc over time, leading to complex species data flows and data inconsistencies. There are a confusing number of data flow-routes, incomplete species group and spatial coverage and a lack of clarity regarding roles, data quality, access, responsibilities, and processes (e.g., for verification).

Economic analysis was conducted of the costs and benefits of the role of the species data pathway in enhancing stewardship of and access to species data, and the decisions that use such data. A baseline (current operation) was compared to a ‘no species data pathway’ scenario in which data stewardship and use is severely impaired due to the absence of the data pathway. The cost-benefit analysis (CBA) found that the benefit of the current species data pathway strongly outweighs its cost. The benefit-cost ratio ranges between 14:1 and 28:1. The availability of resources is a risk to maintaining the current species data pathway and a funding gap of £6 million has been identified through this study.

This study outlines 14 recommendations that are grouped into four themes:

- Defining biodiversity data framework (BDF)

- Investment

- Principles and standards

- Data use and re-use

This study also reviewed the 2018 Scottish Biological Information Forum’s recommendations on biological recording infrastructure - not all are relevant to England, but there are similarities in the priorities both this study and SBIF identify. These include needing to support the financial viability of, and benefits from the pathway, improving current practices (e.g.,on data verification), and using FAIR data principles.

Technical Summary and Recommendations

This study is made up of three main parts:

1.An Investigation of the species data ‘landscape’ in England. 2.An economic analysis of the costs and benefits of the current species data pathway to society. 3.Recommendations

The species data landscape in England

High quality, current and accessible species data are essential to underpin policy and land use planning towards sustainable outcomes for the environment and biodiversity. The species data landscape in England covers all types of marine, freshwater and terrestrial species. The National Biodiversity Network Data Flow Pathway (Figure S1) summarises the operations generally involved in creating, checking and sharing species data so that they can be put to use. Species data provided via this pathway are collected by numerous volunteers and professionals and then processed and stored across a wide range of organisations. Species data can be used for a wide range of purposes including developing and evaluating biodiversity and environmental policies, and decision making within local and national planning systems.

National Biodiversity Network (NBN) data flow pathway

Figure S1: National Biodiversity Network (NBN) data flow pathway

Looking forward, implementing and evaluating outcomes from the Environment Bill, Biodiversity Net Gain and the new Environmental Land Management (ELM) scheme will depend on access to high quality species baseline and monitoring data. Species diversity and abundance in the UK continue to decline and the UK failed to meet most of the CBD’s 2020 Aichi targets for biodiversity. Monitoring of impacts on biodiversity has also not been systematic, but the State of Nature 2019 (Hayhow et al., 2019) concluded that more species have shown strong or moderate decreases in abundance, and/or have decreased in distribution than have increased since 1970. Reliable data on species’ distribution and abundance, shared through a robust and efficient biodiversity data framework, will be essential to plan actions towards nature recovery and, importantly, to evaluate their effectiveness.

There are currently a number of limiting factors and risks associated with the maintenance of the biodiversity data framework that supports the species data pathway. These are:

- Availability of resources - Resources come from funding of organisation’s core functions, cross-subsidising some core functions from the various revenue-generating services that utilise the data, and the large amounts of volunteer time.

- Poor data access - Approximately 50% of potentially useful data were identified as “currently inaccessible” Hassall et al. (2020).

- Variable data quality - not all records marked as ‘verified’ are correct.

- Incomplete spatial and species group coverage.

- A confusing number of data flow-routes - due to the organic nature in which the species data system has evolved since the Victorian era.

Economic analysis of the species data pathway

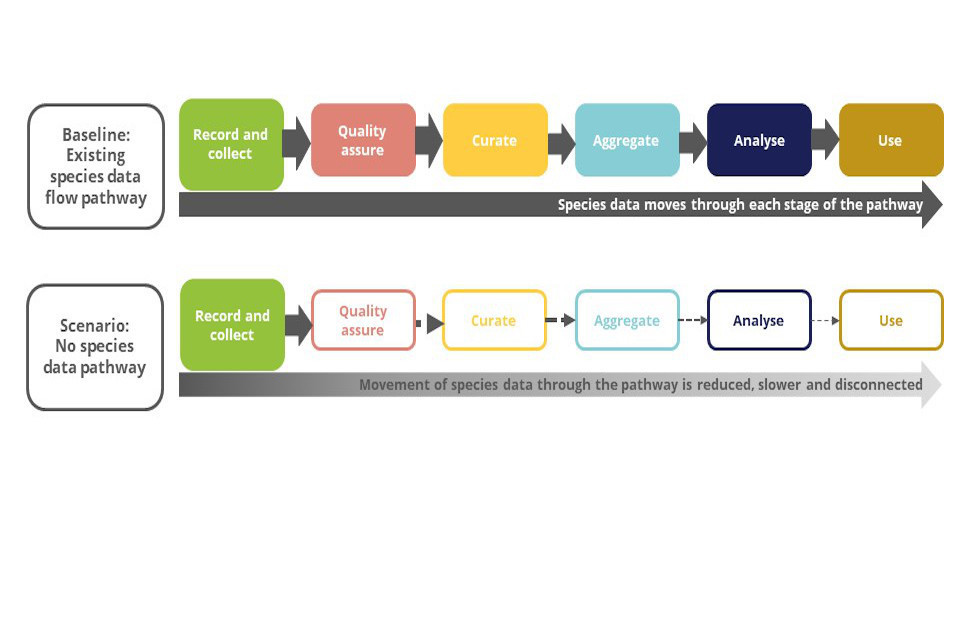

The economic analysis focused on the costs and benefits of the species data pathway, and its role in enhancing access to species data for decision making. The baseline is defined as the current operation of the pathway in England, through which species data is verified, put into a consistent context and shared. This is compared to a scenario in which the species data pathway does not exist, so while the same data is collected, its stewardship and use is severely impaired, as illustrated in Figure S2.

Baseline and scenario of the species data flow pathway compared in economic analysis

Figure S2: Baseline and scenario of the species data flow pathway compared in economic analysis

The economic analysis compares this baseline and scenario in a cost benefit analysis (CBA) framework. The CBA focuses on the data provisioning service of the existing species data pathway. This service is critical, as for users, it is not just about having access to data, but also knowing that they have access to all relevant data.

In the ‘no data pathway’ scenario, data does not flow effectively along the pathway (i.e., from record and collect to end use in Figure S1.). As a result, while the processes that use species data are the same, they operate with no or unstructured species data.

Results of the cost benefit analysis

Table S1 presents the results of the CBA. The ‘minimum’ results represent costs and benefits that have been estimated with the highest confidence indicators, whilst the ‘best’ result reflects a mixture of high and moderate confidence in the methods used. The ‘maximum’ reflects the maximum possible costs and benefits of the system including measures with ‘poor’ confidence. Upper and lower bound indicators of costs and benefits were tested in sensitivity analysis.

Table S1: Cost-benefit analysis outline results: no species data pathway compared to the baseline of current pathway

| Description | Minimum | Best | Maximum |

| Total present value costs (PVC) PV60 £m | 331 | 829 | 2,483 |

| Total present value of benefits (PVB) PV60 £m | 5,643 | 22,939 | 34,003 |

| Net present value (PVB-PVC) PV60 £m | 5,311 | 22,110 | 31,520 |

| Benefit-cost ratio (PVB/PVC) PV60 £m) | 17.0 | 27.7 | 13.7 |

Table notes: The baseline year is 2020. As recommended by the Green Book (HM Treasury, 2020), present values (PV) have been estimated using the standard discount rate (3.5% and declining) over a 60-year appraisal period.

While the monetised estimates account for a number of significant economic costs and benefits, it was not possible to quantify all potential impacts. Nevertheless, the conclusion is that the benefits of the species data pathway to a variety of private and public sector decision-making processes strongly outweigh the costs. Key benefits include achieving water industry and agri-environment objectives and avoiding delays in the land use planning system.

While there may be some omitted costs, the main costs of the pathway are believed to be captured and have been adjusted for optimism bias. The costs for the baseline include a small sum – approx. £100,000 per year – that is not currently funded. This is needed to shore up the system (e.g., to maintain IT hardware and software), and retain the existing large benefits outlined.

There may be significant omitted benefits, such as the role of species data in:

- Organising and motivating wildlife tourism activity and spending.

- Motivating volunteers to be physically active in a way that benefits their health; and

- Understanding several of the ecosystem services identified in the UK national ecosystem assessment (e.g., as an indicator of the quality of vegetation and soil’s capacity to store and sequester Greenhouse Gases).

Conclusions

The species data pathway is of great value to the UK, both to private sector activities and public policy, providing services that are essential to a wide range of decision makers. It is fundamental to activities that interact, evaluate and change the environment. Moreover, it is key to informing strategy on how the environment is managed to benefit people and meet future challenges.

There are strengths of the current species data pathway: it is good at getting a large amount of data recorded and shared, and there is extensive volunteer input in terms of volume of records and expertise. However, biological recorders, many of whom are volunteers, will typically choose a data flow route that reflects their personal experience and the legacy experience of their peer networks. This often leads to errors, omissions and inefficiencies within the biodiversity data system, as well as resistance to new technology or methods of working. However, it has been historically underfunded, and increased funding could enable significant improvements in practices and the application of technology. Novel data capture methods, together with rapid developments in technology, are creating opportunities to accelerate rates of recording and data sharing. The biodiversity data system will need to develop new ways to realise this potential. Economic analysis has identified significant benefits, but the scale of the investment required now, and in the future has not been evaluated.

Recommendations

This study’s recommendations are based on the review of the existing species data landscape, the economic analysis reported above, the results of interviews and workshops held as part of the study, and on the expert opinions of the consortium members who carried out the study. The study also reviewed the applicability of the SBIF recommendations for Scotland to England. It then developed further recommendations for the future management of the species data pathway in England.

While this study looks at the current species data pathway in England, the SBIF review undertook an investment analysis of enhancing the pathway in Scotland. The SBIF review was based on an assumption of open data, which means free data in the sense that the costs to those recording and managing it cannot be recovered. This led to SBIF’s approach to seek 100% government funding for species data pathway and infrastructure enhancements. The SBIF review suggested options for service provision and governance relevant to such a public funding model. This funding model is considered unlikely in England. Therefore, some of the SBIF recommendations do not apply to England. However, both reviews identify similar issues and priorities, and conclude that there are many uses of species data, the benefits of which significantly outweigh the costs of the pathway.

This study makes 14 recommendations in 4 areas, summarised below (further detail can be found in Section 8.3 of the main report).

Biodiversity data framework

The National Biodiversity Network (NBN) includes all the varied organisations and individuals involved in collecting and managing species data in the UK. The key organisations are the NBN Atlas, Local Environmental Record Centre (LERC) databases, National Recording Scheme (NSS) databases (including those hosted by Biological Records Centre). While marine data infrastructure is likely to remain substantially separate from terrestrial/freshwater systems, a level of interoperability around the coastal zone and species that use both environments is desirable. There is a diverse array of actors with an interest in species data. Many of them are supportive of existing system to an extent, but also recommend changes and improvements to deliver better quality, more joined up approaches, better data accessibility or faster response times. Clearer definition of organisations’ roles would assist in improving data flows.

The general consensus between participants in this study and expert opinion is that local and taxon-specific databases are required to enable local and taxon-specific knowledge to be embedded into the data entry, data management and quality assurance processes. It is acknowledged that, in order to improve this system, there needs to be greater transparency of data flows and an adoption of the FAIR Data Principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016, for data to be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable), which could be facilitated via a certification system (see recommendation 6). While there was some support for one centralised database for all species records, there are inherent risks in having a single system, such as over-reliance on a single IT framework and its managers and a loss of engagement from voluntary recorders.

Biodiversity Data Framework Recommendations

1. Recognise the key components of the Biodiversity Data Framework as local data centres, National

Schemes & Societies, UK-wide and marine data portals. Each should have a clearly defined role,

enabling them to work together as a collaborative, connected community.

2. Promote to key sectors the public good, efficiency and conservation benefits of collecting, sharing

and using data through a clearly defined and recognised BDF.

3. Maintain the local and taxon-specific biodiversity databases, with a greater emphasis on

transparent data flows and data sharing via a UK data portal.

Principles and standards

Although the BDF comprises separate organisations, they should operate to shared principles and standards. The FAIR principles are relevant as they aim to ensure that maximum value can be gained from existing data products. They have attracted wider attention and support and received almost unanimous support during the stakeholder consultation for this study. They recognise the rapid acceleration of online data access and the need to support machine discovery and use of data as well as human operation.

Consultation for this study has identified that while the current system enables access to a significant amount of high-quality species data, there are weaknesses. The system has bottlenecks and constraints around data quality and accessibility. Wider adoption of standards, data-sharing protocols and consistent use of clear data flow pathways, which are currently limited due to funding shortages, would be one way to improve this. The need to communicate standards is most acute before the data collection stage, in both professional and volunteer recording. Additionally, training and agreed processes would give assurance to recorders, data contributors, funders and users that improvements were being made. Certification of processes, with a focus on advancement and improvement, is preferred to accreditation of organisations.

Data Principles and Standards Recommendations

4. Base the generation, management, collation and sharing of species data on FAIR Data Principles – to

make species data in England Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable throughout the

species data network. These principles should be adopted in the BDF and should underpin all parts

of the system.

5. Develop and promote data standards throughout the BDF and the wider network of species data

collectors and contributors. Particular emphasis should be on the data collection stage to ensure

data meets its potential for use.

6. Develop a system of certification of BDF processes to drive high common standards across the

network and the adoption of the FAIR principles. This will aid clear data flow pathways and

efficient interoperability between BDF nodes.

Investment

Across almost all stakeholder groups there was support for a mixed-funding model, as it offers an diverse, sustainable framework that promotes innovation opportunities inside and outside of government. The commercial users of species data consulted in this study recognised the fairness of contributing to the costs of data stewardship at the point of use. For the private sector it is often preferable to pay for data that is immediately accessible, known to be comprehensive and high quality, than to receive data of unknown quality and coverage for free. The public sector could fund the core of the species data pathway, in return for free access to species data. This data is needed for delivery of policies in the government’s 25-Year Environment Plan and to support planning, agricultural and environmental legislation. This approach recognises that Open Data is not synonymous with free data (but is more concerned with data accessibility) and aligns to the UK Geospatial Strategy approach to Open Data. The strategy aims to maximise economic, social and environmental value, and for the efficient and fair use of public money.

The SBIF review found that verification systems were under considerable strain and may be unsustainable in the face of rapidly rising demand (i.e., numbers of records requiring verification). This finding is confirmed for England by consultation in this study: data needs to become accessible more rapidly. Technology is both a source of the problem (a conduit of increased records) and may offer part of the solution, through machine learning.

Verification suffers from inconsistencies and unclear processes, which can be addressed by development and use of a protocol. It could cover criteria by which to assign the status of a record, and roles of human and machine verification.

Consultation in this study also revealed that high volumes of species data collected for specialised purposes are not reaching the species data pathway and do not become available for subsequent re-use. These data could contribute to knowledge and decision-making. In future this issue may be partially addressed through implementation of other recommendations in this report. A targeted programme of capture and mobilisation of such datasets would improve access to high-quality species data.

Investment Recommendations

7. Adopt a Data Sharing approach across the pathway, in which many end-users contribute to

reasonable costs of data stewardship within the BDF and, where practicable, species data is

accessible online.

8. Invest in the BDF, from central government budgets, as part of a mixed public/ private sector

funding model, recognising the essential role of accessibility to high quality species data as a

public good to deliver environmental legislation and policy.

9. Develop a verification protocol with key stakeholders in the verification process, which aligns to

current and future verification requirements and technologies. The resources required to support

implementation of the protocol should also be identified.

10. Invest in building capacity for verification, through expert training and the use of new approaches

such as automated assessment to support verification decisions.

11. Invest in processes to capture and mobilise species data generated by research and high volume,

novel recording methods that can be used to supply the BDF.

Improving data use and re-use

In the land use planning process improvements can be made to the sharing of primary data and the re-use of existing data. Many stakeholders expressed concern that, in a high proportion of planning applications affecting biodiversity, existing species data is not being accessed and that omission adversely affects the quality of decision making.

Species data collected by consultants to support assessments of projects that require regulatory approval do not normally reach the species data pathway and therefore are unavailable for re-use. This represents a wasted resource. In the marine environment the Marine Data Exchange provides an example of how this can work successfully for all parties. Established by The Crown Estate in 2013, this resource helps to make valuable data freely accessible, promote collaboration within the sector, reduce survey costs and ultimately de-risk investment offshore (Crown Estate, 2021).

For over a decade it has been a requirement of the Chartered Institute for Ecology and Environmental Management (CIEEM) consultant members to share data. A portal has been in place (Vogel, 2016, Smith et al 2016) to facilitate data re-use, but it is regarded as ineffective. Although there is a requirement for data collected using certain public funds, such as government or National Lottery, to be shared, there is little or no follow-up to ensure data are shared. Data collection and sharing are often afterthoughts in a project and at project closure.

Data Use Recommendations

12. Mandate the re-use of species data collected by consultants in transparent processes that support

regulatory compliance, potentially through new regulation. This will reduce survey costs, improve

professional standards and support environmental outcomes.

13. Require proponents of development to certify that best available species data through the BDF

have been accessed in the preparation of applications where there is risk of impact on

biodiversity, potentially through new regulation. This will help ensure that existing and newly

collected species data is equally available to project proponents, regulators and evaluators and

will support environmental outcomes.

14. Require organisations collecting data funded by public money to provide a plan for data

collection and sharing, in accordance with FAIR data principles, before funds are received.

Systems to support these recommendations and implement FAIR data principles require further investigation.

Future development of the Species Data Pathway

The following principles are suggested as a basis from which to manage the species data pathway in future:

- Recognise the specific characteristics of the pathway, in particular the role played by volunteers. Data recording and collection (and possibly stewardship along subsequent parts of the pathway) are often not part of funded activities, meaning useful data is recorded but budgets are not allocated to stewardship of that data.

- Organise the system to support FAIR principles to maximise the value of species data to society. In the data pathway, organisational structures, relationships and governance, staff resources and skills and funding should all aim to support the FAIR principles.

- Enable those who support the species data pathway through stewardship of data (in line with FAIR principles) to cover the costs of efficiently doing so and be financially viable. This means being able to retain rights over data where needed to generate income.

- Embed the interpretation of ‘accessible’ in FAIR as ‘shared data’ (rather than ‘free data’).

The challenge for managing the species data pathway is to balance the FAIR data principles with the need for financial viability. This needs to be done in a way that supports stewardship of higher quality, shared species data in the long term. The funding of the biodiversity data system from public funds is justified based on the benefits it supports for wider society and taxpayers. Further revenue can be obtained from the sectors who need to access biodiversity data and realise value from doing so. The focus should be on sustaining revenue for data stewardship from those who get value from it.

There are a number of actions that can be implemented, and provide benefits, relatively quickly. This study has identified ‘quick wins’ in areas such as data verification, implementation of FAIR data principles, and engaging funders of the species data pathway to build awareness of good practice. The most immediate need is to shore up the system to stop collapse through investment in national IT support and additional staff to enhance resilience and capacity for development.

Investments to improve and simplify the species data pathway in England require consideration of what an enhanced biodiversity data system/pathway would look like, which is beyond the scope of this study. Mapping of the current data flows is needed to identify options for rationalisation, and whether organisations in the pathway have appropriate capabilities. Planning of investment in England, and at UK scale, would also benefit from research into the needs of biodiversity (and species) data users. In developing investment options, it is recommended that:

- Full consultation of the organisations and stakeholders involved is carried out to help design and implement changes;

- Provision is made for training to develop the skills needed to realise the benefits and minimise the risks from any changes; and

- Key objectives are coordinated across the UK.

It should be noted that changes in organisations and/or process will also require the culture and behaviour for staff and volunteers to adapt. If the benefits of any change are not communicated to and accepted by those involved through lack of transition planning and funding, this increases the risk that expertise could be lost and data sharing reduced. Funding this culture change should be seen as an investment in retaining and growing the total contribution of volunteers to data recording and the long-term function of the species data pathway.