Levelling Up Fund: monitoring and evaluation strategy

Published 31 March 2022

1. Executive summary

The Levelling Up Fund (LUF) was announced by HM Treasury (HMT), the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (DLUHC) and the Department for Transport (DfT) in March 2021, with total funding of £4.8 billion.

LUF seeks to improve everyday life by investing in capital infrastructure that will have a tangible impact on local places across all parts of the UK. Whilst it is open to all places, there is a degree of prioritisation of funding according to need (i.e. places where it can make the biggest difference to everyday life, including ex-industrial areas, deprived towns and coastal communities).

LUF focuses on three types of intervention:

- Transport investments including public transport, active travel, bridge repairs, bus priority lanes, local road improvements, and accessibility improvements.

- Regeneration and town centre investment, to upgrade eyesore buildings and dated infrastructure, acquire and regenerate brownfield sites, invest in secure community infrastructure and crime reduction, and bring public services and safe community spaces into town and city centres.

- Cultural investment maintaining, regenerating, or creatively repurposing museums, galleries, visitor attractions (and associated green spaces) and heritage assets as well as creating new community-owned spaces to support the arts and serve as cultural spaces.

The LUF Prospectus sets out what the policy wants to achieve, through investing in infrastructure to improve everyday life, focusing on improving economic growth, pride in place, and bringing communities together. This means tackling economic differences and driving prosperity as part of ‘levelling up’ left behind regions of the UK, improving lives by giving people pride in their local communities, and as the country recovers from the unprecedented economic impacts of COVID-19, investing in projects that not only bring economic benefits, but also help bind communities together.

To make the evaluation of LUF as effective as possible , we have looked to develop on these intentions and maximise learnings. Therefore, what will be monitored and evaluated will go beyond the initial impacts set out in the Prospectus, drawing on the latest evidence and the Levelling Up White Paper to identify the impacts LUF will have on society as a whole.

In addition, LUF has been designed with local discretion in mind. Local places have designed projects to meet local needs. The problems in each place will vary depending on place-based context. Local problems and solutions may differ from the national picture, as this is not a one-size-fits-all policy.

LUF aims to target the following broad problems:

Problem 1: There are spatial differences across the UK in economic outcomes including lower living standards, pay and productivity.

Problem 2: There are spatial differences in social outcomes including lower levels of social cohesion, pride in place, higher levels of crime and poor housing.

Problem 3: There are spatial differences in health outcomes including higher levels of diabetes, smoking, alcoholism, and premature mortality in areas of higher deprivation.

A review of academic literature and policy resources resulted in a Theory of Change that the evaluation will seek to test. Given the multiple intervention themes of LUF, thematic theories of change are being developed and will feed into the design of the evaluation.

The monitoring and evaluation of LUF comprises four key components:

- Monitoring will be used to track the delivery and costs of projects and to identify where additional support may be necessary throughout the programme.

- Process evaluation will aim to understand how LUF was delivered in funded areas, generating lessons into what worked well, what did not work as intended, and the role of central government in facilitating delivery.

- Value for money and impact evaluations, which are currently being scoped and developed, will aim to demonstrate whether LUF delivered value for taxpayers’ money and if it effectively delivered the desired outcomes and impacts.

2. Introduction

This document sets out the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities’ (DLUHC), and Department for Transport’s (DfT) approach to the monitoring and evaluation of the Levelling Up Fund (LUF). It has been developed collaboratively across government, including the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), HM Treasury (HMT), and the Evaluation Task Force (ETF), along with external expertise from the What Works Centre for Local Economic Growth. It intends to inform the public, and stakeholders, of the context in which the evaluation will be conducted, the rationale driving it forward and some of the eventual outputs it will produce.

The aims of the document are to provide a strategy outlining the activities that will be conducted to answer key questions on what works and why. The evidence generated will feed back into the implementation of LUF delivery and strengthen the approach used for other funds contributing to the objectives of the levelling up agenda. The strategy is designed to be flexible, to allow the approach to evolve as LUF delivery progresses.

Monitoring and evaluation are key activities at the centre of understanding what works and why. As outlined in the Magenta Book, “evaluation is the systematic assessment of the design, implementation and outcomes of an intervention”. Whilst monitoring can demonstrate progress on meeting certain goals, and can guide necessary adjustments in response, evaluation establishes whether overall objectives have been met and the extent to which change has occurred as a direct result of an intervention.

2.1 The Levelling Up Fund

The Levelling Up Fund (LUF) is delivering local priorities that have a visible impact on people and communities across all parts of the UK, including Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. LUF is investing in capital infrastructure that improves everyday life and has a tangible impact on local places. For Round 1, LUF invested in projects across three themes: regenerating town centres and high streets, upgrading local transport, and investing in cultural and heritage assets. Funding is targeted towards places with the most significant need, as measured by the index of priority places. This considers places’ need for economic recovery and growth, improved transport connectivity and regeneration, in line with LUF’s objectives. Deliverability, value for money, and strategic fit were the key criteria also considered when assessing bids. For more information on this process please see the Levelling Up Fund: explanatory note on the assessment and decision-making process.

The Levelling Up Fund is a successor fund to the Local Growth Fund (LGF) which, through a series of deals with Local Enterprise Partnerships, invested in skills capital, built new homes and supported infrastructure projects including transport improvements and superfast broadband networks. Unlike LGF which was England-only, LUF is available to local areas across England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

LUF is one element of the overall plan to level up opportunity across the UK as set out in the Levelling Up White Paper published in February 2022. Since 2019, the UK government has supported places to revitalise town centres, retain community assets and grow their economies through programmes like the £4.8 billion Levelling Up Fund (LUF), the £900 million Getting Building Fund, the £400 million Brownfield Housing Fund (BHF) in England, the £150 million UK-wide Community Ownership Fund (COF), the £3.6 billion Towns Fund, the £220 million Community Renewal Fund (CRF) and the £2.6 billion UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF).

LUF will be allocated through a competitive process with funds to be spent from 2021-2022 to 2024-2025 financial years and multiple rounds of funding expected. In October 2021, 105 successful bids were awarded a total of £1.7 billion during the first round of LUF. The second round of LUF was launched in March 2022.

As set out in the LUF prospectus, the key thematic areas for intervention for the first round of funding are:

- Transport investments including (but not limited to) public transport, active travel, bridge repairs, bus priority lanes, local road improvements and major structural maintenance, and accessibility improvements. We requested proposals for high-impact small, medium, and by exception larger local transport schemes to reduce carbon emissions, improve air quality, cut congestion, support economic growth, and improve the experience of transport users.

- Regeneration and town centre investment, building on the Towns Fund framework to upgrade eyesore buildings and dated infrastructure, acquire and regenerate brownfield sites, invest in secure community infrastructure and crime reduction, and bring public services and safe community spaces into town and city centres.

- Cultural investment maintaining, regenerating, or creatively repurposing museums, galleries, visitor attractions (and associated green spaces) and heritage assets as well as creating new community-owned spaces to support the arts and serve as cultural spaces.

Environmental sustainability is a cross-cutting theme with initiatives expected to support Net Zero objectives and issues such as flood defences.

2.2 Approach to developing the Levelling Up Fund Monitoring & Evaluation Strategy

The LUF M&E strategy is comprised of four sections. These describe the challenge places are facing, the underlying theoretical foundation of the M&E strategy, the M&E aims and objectives, and the overall M&E approach.

Problem analysis summarises the analysis conducted into the challenges places are facing. The analysis is based on evidence from available literature and stakeholder engagement.

Theory of Change (ToC) provides the theoretical foundation on which the monitoring and evaluation approach will be built. An actor-based ToC approach was used to gain a detailed understanding of how LUF intends to address the problems laid out in the problem analysis. This was then translated into an overarching ToC for LUF, describing five levels of change (Activities, Outputs, Intermediate Outcomes, Outcomes and Impacts) as well as their causal pathways. The section also describes the assumptions and hypotheses and provides references to literature where available.

Monitoring and evaluation aims and objectives, details the key aims of the M&E Strategy and what we intend to achieve.

The monitoring and evaluation approach sets out the four main activities that will be conducted to assess the delivery, value for money and impact of LUF, and some of the key questions these activities will attempt to answer.

3. Problem analysis

As the Levelling Up White Paper sets out:

The UK has larger geographical differences than many other developed countries on multiple measures, including productivity, pay, educational attainment and health. Urban areas and coastal towns suffer disproportionately from crime, while places with particularly high levels of deprivation, such as former mining communities, outlying urban estates and seaside towns have the highest levels of community need and poor opportunities for the people who grow up there. These disparities are often larger within towns, counties or regions than between them. There are hyper-local and pockets of affluence and deprivation may exist in the same district. Indeed, many of the worst areas of deprivation are found in the UK’s most successful cities. While change is possible, in some cases, these differences have persisted for much of the last century. And some of the UK’s most successful cities – such as Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds, Glasgow and Cardiff – lag behind their international comparators when it comes to productivity and incomes.

The LUF Prospectus sets out what the policy wants to achieve, through investing in infrastructure to improve everyday life, focusing on improving economic growth, pride in place, and bringing communities together. This means tackling economic differences and driving prosperity as part of ‘levelling up’ left behind regions of the UK, improving lives by giving people pride in their local communities, and as the country recovers from the unprecedented economic impacts of COVID-19, investing in projects that not only bring economic benefits, but also help bind communities together.

To make the evaluation of LUF as effective as possible, we have looked to develop on these intentions and maximise learnings. Therefore, what will be monitored and evaluated will go beyond the initial impacts set out in the Prospectus, drawing on the latest evidence and the Levelling Up White Paper to identify the impacts LUF will have on society as a whole.

In addition, LUF has been designed with local discretion in mind. Local places have designed projects to meet local needs. The problems in each place will vary depending on place-based context. Local problems and solutions may differ from the national picture, as this is not a one-size-fits-all policy.

Therefore, for the purpose of this evaluation we have identified the following broad problems faced by places that LUF will aim to target:

Problem 1:There are spatial differences across the UK in economic outcomes including lower living standards, pay and productivity.

Problem 2: There are spatial differences in social outcomes including lower levels of social cohesion, pride in place, higher levels of crime and poor housing.

Problem 3: There are spatial differences in health outcomes including higher levels of diabetes, smoking, alcoholism, and premature mortality in areas of higher deprivation.

It is important to acknowledge that although LUF is focused on capital infrastructure, lack of capital investment is only one of many factors that contributes to the problems set out above. The Levelling Up White Paper proposes that levelling up is achieved by a mutually reinforcing system of 6 capitals: physical, intangible, human, financial, social and institutional. A lack of investment in capital infrastructure will affect most, if not all, the 6 aforementioned capitals in some way.

Through a series of workshops and consultations between DLUHC and DfT and with advice from DCMS, we have produced the following, high level problem analysis summary below.

Problem summary:

Problem 1:

There are spatial differences across the UK in economic outcomes including lower living standards, pay and productivity

Several ongoing and interrelated socioeconomic factors contribute to the problem including:

- Fragmented land ownership of town centres and high streets and conflicting aspirations of land and property owners lead to challenges with coordinated planning and development strategy.

- Places have poor access to finance, resulting in a lack of funding for investment into key transport, cultural and civic infrastructure.

- Transport and digital connectivity issues make places less attractive to people and business. In some areas public transport networks may be fragmented, resulting in longer journeys which are inconvenient or impractical. For those who travel by car, congestion and longer journey times may impact on the distance that someone is prepared to travel for a job. Poor digital connectivity can make it less attractive for businesses to set up in a place or for people to work from home.

- Economic growth of the creative industries is not evenly distributed across the UK, and growth is focused on London and southeast.

- There is a market failure that results in a disparity in participation / engagement with arts / culture and consequently sub optimal outcomes.

- Buildings not suited to the demands of the current era. The spatial organisation of towns and high streets is not suited to post-industrial use.

- Persistent socioeconomic factors such as intergenerational unemployment and deprivation at a family level, poor social mobility, high geographic inequality and overall depopulation.

Problem 2:

There are spatial differences in social outcomes including lower levels of social cohesion, pride in place, higher levels of crime and poor housing. ####Several ongoing and interrelated socioeconomic factors contribute to the problem including:

- There is an uneven geographic distribution of cultural funding, reducing the opportunity for communities to interact and take part in shared experiences and activities that may be important in determining levels of local pride. Where cultural assets are available and free/affordable nearby, not all people possess the cultural capital to feel comfortable accessing them.

- Poor transport connections may contribute negatively to perception of place. This can also contribute to isolation and reduced social contact.

- The foundations of the traditional high street have been weakened resulting in poor social cohesion.

- High vacancy rates and poor-quality housing sitting alongside deprivation and economic underperformance contribute to low pride in place.

Problem 3:

Several ongoing and interrelated socioeconomic factors contribute to the problem including:

- A lack of green/blue public spaces (such as parks and lakes) can contribute to a lower sense of wellbeing and reduced opportunities for physical activities. This can lead to poor mental and physical health

- Higher levels of unemployment in towns can contribute to poor health outcomes. Having a job was the second biggest factor associated with wellbeing and several health indicators are correlated with levels of income

- Lack of investment in social infrastructure that supports aspects of culture and local community can have negative impacts for the health, wellbeing, and economic prosperity of our communities.

- Lack of safe space for young people in a local community, including a lack of things to do outside of school, can lead to increased fear within the community for young people.

Solutions

The identification of these broad problems led Round 1 of LUF to focus on three broad investment themes: upgrading local transport, regenerating town centres and high streets, and investing in cultural and heritage assets.

Local transport

Investment in local transport networks can revitalise local economies by boosting growth, improving connectivity, and creating healthier, greener, and more attractive places to live and work. Almost all journeys start and finish on local transport networks, so investment can make a real, tangible difference to residents, businesses, and communities. Local transport projects can play a pivotal role in enhancing places and bolstering efforts to level up. This could include upgrading bus and cycling infrastructure to improve access to jobs whilst supporting cleaner air and greener, healthier travel; targeting local road enhancements at congestion pinch points, and repairing bridges to ensure that communities are not isolated from key services.

Regeneration

Town centres are a crucial part of our communities and local economies, providing both a focal point for retail and hospitality trade, and a meaningful centre of gravity for local communities. The UK government recognises that in recent years, changing consumer behaviour has made things tougher for retailers in our town centres and high streets, an issue made even more apparent by the impact of COVID-19. In addition, while some local areas have benefited from programmes such as the Towns Fund, some places such as smaller towns have not yet been able to access this investment.

At the 2018 Budget, the UK government published ‘Our Plan for the High Street’, spearheading a number of initiatives including the Towns Fund, to renew and reshape town centres and high streets so they look and feel better and can thrive in the long term. The regeneration pillar of LUF seeks to build on this philosophy and on the investments made so far through the Towns Fund.

LUF will help communities transform derelict, vacant or poorly used sites into vibrant commercial and community hubs that local people can be proud of.

Cultural and heritage assets

Investment in cultural assets can rejuvenate places, leading to positive economic and social outcomes at a local level. It can help to retain and grow a highly skilled workforce, attract tourists to bolster local business, and provide opportunities to grow people and communities’ connections with places. Additionally, supporting the development of a more positive relationship between people and place can have a positive impact on both mental and physical health. In short, culture and heritage are things that bring people together across the country and strengthen communities.

Perception of place is an important ‘pull’ factor in investment and business location decisions, and can affect a place’s capacity to attract talent – especially young people – and retain workers. Many towns already have a strong heritage and sense of place, and benefit from their cultural and civic assets both directly, from tourism and visitor revenue, and indirectly, by inspiring a sense of local pride and community cohesion, making places more attractive to live and work in. Alongside towns, rural areas also often possess a rich tapestry of local culture and heritage assets.

Preserving heritage is not limited to simply attracting tourists; many town and city centres across the UK are historic and beautiful in their own right and ensuring this remains the case is crucial to securing the future of the businesses that occupy them, working in synergy with the regeneration and town centre investment theme of LUF.

Key principles

As well as aiming to tackle specific local problems as identified by local authorities, LUF also aims to uphold two key principles throughout its implementation:

- Principle 1: LUF programmes should be consistent with the government’s net zero ambitions and contribute to meeting local environmental targets.

- Principle 2: The programme should contribute to reduced silos between government departments to improve national economic management and local economic capabilities and economic management.

4. Theory of Change

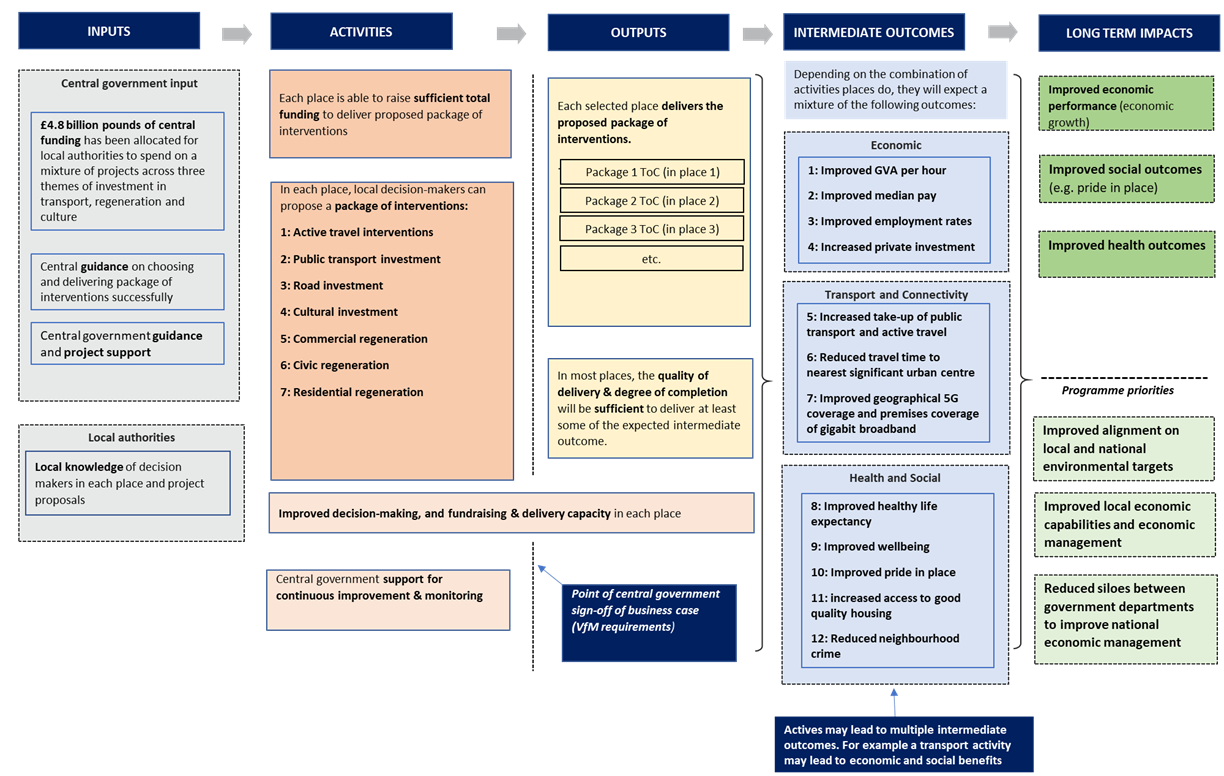

A Theory of Change (ToC) maps out how an intervention or change is expected to achieve the desired objectives. It shows the links between the inputs and activities comprising an intervention, and how this is expected to lead to outputs and outcomes that produce the expected impacts.

A review of academic literature and policy documents resulted in a TOC that the evaluation will seek to test. Given the multiple intervention themes of LUF, thematic theories of change are also being developed and will feed into the design of the evaluation.

The programme-level ToC is set out in our high-level theory of change theory of change illustrating the overall logic underpinning LUF. Local projects will be responding to place-based problems and therefore LUF programmes will range significantly in intervention themes, scale of investment and delivery. Therefore, outcomes and impacts may vary from the programme-level ToC for individual projects.

The expected timeframes for project delivery, realisation of outcomes and impacts will vary in relation to the nature and objectives of each project. For example, an active travel intervention (such as building a new cycleway) could expect to see intermediate outcomes materialise soon after the interventions are implemented (e.g. through increased take-up of cycling), whereas for a large-scale commercial regeneration project it may take several years to observe any changes in median pay and employment rates. It should also be noted that the impacts outlined in the ToC are likely to materialise over a relatively long timeframe post-project delivery e.g. it could take 5 to 10 years to be able to measure the impacts of schemes on economic performance

High level theory of change:

Inputs:

- £4.8 billion pounds of central funding has been allocated for local authorities to spend on a mixture of projects across three themes of investment in transport, regeneration and culture

- Central guidance on choosing and delivering package of interventions successfully

- Central government guidance and project support

- Local knowledge of decision makers in each place and project proposals

Activities:

- Sufficient total funding to deliver proposed package of interventions

- Central government support for continuous improvement & monitoring

In each place, local decision-makers can propose a package of interventions:

1: Active travel interventions

2: Public transport investment

3: Road investment

4: Cultural investment

5: Commercial regeneration

6: Civic regeneration

7: Residential regeneration

Outputs:

- Each selected place delivers the proposed package of interventions.

- In most places, the quality of delivery & degree of completion will be sufficient to deliver at least some of the expected intermediate outcome.

Intermediate outcomes:

Depending on the combination of activities places do, they will expect a mixture of the following outcomes:

1: Improved GVA per hour

2: Improved median pay

3: Improved employment rates

4: Increased private investment

5: Increased take-up of public transport and active travel

6: Reduced travel time to nearest significant urban centre

7: Improved geographical 5G coverage and premises coverage of gigabit broadband

8: Improved healthy life expectancy

9: Improved wellbeing

10: Improved pride in place

11: increased access to good quality housing

12: Reduced neighbourhood crime

Long term impacts:

- Improved economic performance (economic growth)

- Improved social outcomes (e.g. pride in place)

- Improved health outcomes

Programme priorities

- Improved alignment on local and national environmental targets

- Improved local economic capabilities and economic management

- Reduced siloes between government departments to improve national economic management

The links between the stages of the ToC may be influenced by a number of enablers, that facilitate programme delivery and success. Programme delivery is also open to externalities, that are potential negative spill over effects that are not desired outcomes or impacts of the programme (for example, there is a risk that policies that increase economic activity and land value in places results in displacement for lower income groups). In addition, programme delivery and impacts may be affected by risks. There are also a number of key hypotheses that underpin the links between the components of the ToC. We set out those enablers, externalities and risks, and hypotheses below.

Key enablers

-

Stable macroeconomic conditions (including inflation, shocks to global economy, shocks to the labour market).

-

A smooth recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and easing of restrictions.

-

Local authorities having the skills and/or access to skills needed to complete projects, e.g., architects, designers, city planners, construction capability.

-

Central government plays an effective supporting role for local authorities.

-

Central government works effectively across departments to deliver levelling up priorities.

Key externalities and risks

-

There is a risk that policies that increase economic activity and land value in places results in displacement for lower income groups.

-

Evaluation evidence from similar past programmes suggests there is a risk that commuters, rather than residents, will benefit from interventions.

-

Construction projects that are not aligned with Net Zero commitments risk increasing emissions in the long run.

-

Transport investment in improving road infrastructure may lead to increased private car trips, which could be at odds with the aim of boosting take-up of more sustainable forms of travel.

-

There is a risk that short term inflation[footnote 1] increases costs of delivery and impacts project value for money. Additionally, supply side constraints, may make it difficult to get hold of certain materials and products.

Key hypotheses and assumptions

-

Projects are well-aligned with the strategic goals of LUF.

-

Fund projects are delivered on time according to design.

-

If places engage with the local community throughout project design and development, then interventions are more likely to receive local support and therefore achieve higher impact.

-

Areas need to receive an optimal amount of funding, enough to have a real impact.

-

If support is provided to address capacity and capability gaps and build partnerships, then capital investments are more likely to be successful in creating sustainable growth locally.

-

If places improve the built environment, skills and business opportunities, and transport connectivity, these changes will improve the image and sense of place among residents as well as among potential visitors and investors.

-

If the image and sense of place among residents, potential visitors and investors improves, then in the longer term this should increase demand and supply, enhancing economic growth.

-

If places have good quality transport options, then connectivity and take-up of public transport/active travel will improve, which can have a positive impact on business start-ups, employment, investment, and town centre footfall.

5. Monitoring and evaluation aims and objectives

LUF represents a unique opportunity to develop better understanding of what works for levelling up in the UK. Due to the spread of project themes and geographic locations in LUF’s allocation, there is an opportunity for learning from a broad range of interventions across the UK.

The monitoring and evaluation of LUF will comprise the main components listed in below:

Monitoring

To track whether places are delivering what they said they were going to deliver, when they said they were going to deliver it, and in line with forecast costs.

Process evaluation

To explore what worked well, and what did not work as intended, in the design and delivery of the fund, and why. Impact Evaluation

To assess what changes have occurred, the scale of those changes and the extent to which they can be attributed to the intervention.

Value for money evaluation

To understand whether LUF delivered value for money. The exact approach to be taken is also dependent on the outcomes of the feasibility study outlined below (section 6.3).

6. Monitoring and evaluation approach

LUF will fund projects across the UK, taking place-based approaches across thematic areas of intervention. In Round 1 of LUF 105 places received funding, with more places to receive funding in future rounds. Therefore, there are multiple levels at which we could evaluate LUF, ranging from place-based evaluations of individual schemes (carried out by local authorities and other scheme promotors), thematic evaluations (e.g. focusing on groups of similar interventions to improve our understanding of what works), to potentially assessing the impact and the effectiveness of delivery at the programme-level. Local authorities are required to report monitoring data to central government and carry out their own place-based evaluations.

We are currently developing the plan for the overarching programme evaluation and we intend to carry out a feasibility study to fully assess the options for impact and value for money evaluations. The following section sets out the aims of the programme-level evaluation and our proposals for developing these plans further in the coming months.

6.1 Monitoring

Aim

Monitoring will be used to track the progress of projects and to identify where additional support may be necessary throughout the programme. The monitoring data collected will enable the department to check progress against project milestones, ensure funding is being spent according to agreed terms, and that the agreed outputs are being delivered. This activity will also aim to identify who is benefitting from the programme. The data collected will also feed into the programme’s process, impact, and value for money evaluations.

Key questions could include:

1. How are places performing in terms of:

a. Progress against delivery plan

b. Spend against profile

c. Delivering agreed outputs

d. Identifying and mitigating risks

e. Identifying challenges and opportunities

2. Does the place in question satisfy assurance requirements to enable next payments to be issued?

3. If not, why not? What steps are needed to get back on track?

The following questions will be partially answered through the monitoring information but will be explored further as part of the process evaluation:

1. What support do places need while in the delivery phase?

2. What is working well in delivery, and what needs improvement?

3. What lessons on delivery can be shared within the duration of the programme?

Data sources

LUF recipients will be responsible for providing monitoring data on a quarterly and six-monthly basis. The data required at each point was set out in M&E guidance that was shared with LUF Round 1 recipients in November 2021, alongside lists of “standardised” output and outcome indicators (i.e., indicators with standard definitions, units of measurement, and evidence requirements). At the same time, the department undertook an information gathering exercise, including financial profiles, delivery plans, outputs and risks, to establish “forecasts” for all projects prior to them starting. A monitoring template, along with further detailed guidance on how to complete this, will be shared with LUF Round 1 recipients in spring 2022.

The monitoring data being requested of LUF recipients aligns with the structure of the Theory of Change and, therefore, includes:

- Inputs & Activities (e.g., amount spent on project delivery)

- Outputs (e.g., amount of new industrial space created)

- Intermediate Outcomes (e.g., change in footfall)

- Outcomes (e.g., change in private investment)

LUF recipients will be required to report on inputs, activities and outputs until project completion at the earliest but, for some indicators – particularly outcomes – we may require collection and reporting of data for several years post-project completion. As each project’s circumstances are unique, we will agree the terms with each recipient once their projects have been confirmed.

It is anticipated that DLUHC and DFT will also collect and analyse data on outcomes/impacts according to longer timeframes, using data beyond that which is collected from LUF recipients. For example, this could include administrative datasets, routine statistical collections or bespoke research such as surveys. This will be explored further as part of the more detailed design work which will follow this strategy.

LUF recipients may obtain the data requested in the monitoring template from various sources. It is anticipated that most of the data will be gathered directly by recipients through primary data collection. In some instances, project partners may provide data; the recipient may choose to contract out data collection to a third-party organisation; or the recipient may procure data (e.g., for tracking certain outcomes). In all such instances, it will remain the responsibility of the recipient to report the data through the agreed monitoring processes.

The monitoring data submitted to DLUHC and DFT by LUF recipients will play a crucial role in assurance and performance management processes, but it is also expected to feed into all levels of evaluation. Learning is not expected to be confined to interim and final evaluation reports, as ongoing analysis of the data will enable lessons to be learned, and more effective decisions to be made, as the programme progresses. Wherever possible, these insights and lessons will be disseminated amongst recipients and relevant stakeholders, to address issues, improve delivery, and maximise the impact of the fund.

6.2 Process evaluation

Aim

The process evaluation aims to understand how LUF was delivered in areas which received funding. It will generate lessons on what worked well and what did not work as intended, which will feed into continuous improvement of subsequent rounds of delivery. These lessons learnt will also be used to inform policy design and delivery of other funds. Further scoping work will be carried out to specify the methodology for the process evaluation, and a broad outline of the intended approach is provided below.

Key questions could include:

Programme-level process and engagement

1. How well was the competition and fund run?

2. To what extent has the process built leadership, partnerships and/or capability in local authorities (or in Northern Ireland, institutions such as universities)?

3. To what extent has LUF enabled closer working relationships within central government in relation to addressing economic growth challenges across all parts of the United Kingdom?

4. To what extent are there reduced siloes and strengthened cooperation between DLUHC, DfT and HMT? Have economic challenges in priority places across the United Kingdom been addressed through more streamlined, tailored and coherent interventions?

Intervention-level delivery

5. When designing their projects, to what extent did grant applicants consult all relevant groups, including people from excluded and/or disadvantaged backgrounds?

6. Where an application was from a local authority, to what extent were they aware of the needs of excluded and/or disadvantaged groups, and are these addressed in full in their bid?

7. What support did places receive from central government? Did that have a material effect on the successful delivery of projects and the outcomes and outputs sought?

8. What support did other organisations in Northern Ireland require to deliver LUF? Did they differ from local authorities in implementing LUF?

9. If delivery partners were appointed, what difference did they make in implementing programmes?

10. What support do places need while in the delivery phase?

11. What is working well in delivery, and what needs improvement?

12. What lessons on delivery can be shared within the duration of the programme?

13. Did any places not achieve their aims and objectives? Did these places have any shared characteristics?

14. Were there any common enablers or facilitators that positively contributed to realising outcomes?

15. Were there any common blockers or barriers that negatively contributed to realising outcomes?

Data sources

The process evaluation will draw on regular monitoring data provided by places. This may be supplemented with administrative datasets to provide a quantitative overview of the performance of each place against their key indicators and metrics. Interviews and focus groups with place leads and project managers will provide qualitative insight to expand on quantitative data. These qualitative research activities will deliver on-the-ground, operational insight into what worked well during the delivery and implementation of LUF, and what did not work as intended.

The technical guidance accompanying LUF also requires places to develop and deliver their own local evaluations. As with the monitoring activity, it is anticipated that places will either undertake their own data collection or commission this to project partners or third-party organisations.

6.3 Impact and value for money evaluations

We are committed to undertaking high-quality, robust impact evaluations of our policies wherever possible. Given the complexity of LUF’s delivery model and the potential for successful places to be in receipt of other funds with similar aims and objectives, it will be challenging to design an impact evaluation that can clearly show causal links between interventions and impacts. As such, scoping of the impact and value for money evaluations requires further exploration to understand what methodologies are available to assess the impact of LUF.

For programme-wide impact evaluations, a feasibility study will be conducted to ascertain what is achievable given the complexity of LUF’s delivery model, and whether outcomes and impacts can be quantified and directly attributed to LUF at the programme-level. The feasibility studies will shed light on what evaluation methods are most appropriate, based on exploring which outcome or outcomes can be used to measure impact – for example, choosing between theory-based methods or quasi-experimental approaches. This will also help to establish the timings for the delivery of evaluation activities, and the data collection required. We will explore using administrative datasets, including the ONS Integrated Data Service and data from other government departments, in combination with commercial datasets, to conduct impact evaluations – although this may change and evolve following completion of the feasibility studies.

As outlined in section 6 we may also pursue the option of conducting thematic impact evaluations. These could focus on groups of similar interventions to gather more robust evidence on whether certain types of interventions are effective at achieving their objectives. This could also provide the opportunity to establish control groups in areas which have similar types of characteristics but did not receive the interventions in question. In designing thematic evaluations, we could be guided by the seven sub-themes outlined in the Theory of Change: active travel interventions, public transport investments, road investments, cultural investments, commercial regeneration, civic regeneration, and community regeneration. More granular theories of change for these themes are being developed, and through the feasibility studies we will seek to understand what methods may be most appropriate for conducting this level of evaluation. These thematic impact evaluations may also include case studies that examine both qualitative and quantitative data in particular places, to build more comprehensive understanding of the impact of interventions.

The ability to attribute causality between inputs/activities and impacts will have a direct impact on how, or if, we are able to conduct a value for money evaluation. If we are unable to link outcomes and impacts to LUF, we will not be able to assess whether it is delivering value for money. It is key, therefore, that we explore if we can assess the extent of the causal relationship between activities and impacts before we can consider the methods and data sources that will be most appropriate to show LUF’s effectiveness, economy, efficiency and equity. The resulting value for money evaluation approach will need to be complex to account for the complexity of LUF’s delivery model and the potential range of benefits that may emerge.

As with the option of conducting thematic impact evaluations, the feasibility studies may also explore the possibility of conducting value for money evaluations of individual projects, or types of projects grouped under the intervention sub-themes listed previously. If feasible, these intervention-level value for money evaluations will aim to deliver some robust evidence of ‘what works’ if we are unable to conduct value for money evaluations at a programme-level.

7. Next steps

This document presents a high-level strategy for undertaking monitoring and evaluation for the Levelling Up Fund. It will be followed by a more in-depth evaluation design stage that will consider approaches, methodologies and data availability with respect to each of the main evaluation activities (process, impact and value for money). This design stage (which will incorporate the feasibility assessments outlined above) will further consider the scale and logistics of the evaluation activities, including which activities will be conducted internally or commissioned out to external experts.

Further updates to the strategy may be published later in 2022, covering the design of the impact, process and value for money evaluation activities.

-

In February 2022, inflation is running at 30-year high of 6.2.% according to CPI annual rate, February 2022. More increases are forecasted for 2022, expected to lead to a peak in spring 2022 of over 8%. This could significantly impact the costs for delivery, because of increased costs of labour, materials, and components. ↩