IPO Counterfeit goods research (Wave 4)

Published 17 June 2025

ISBN

978-1-915090-61-4

Print this page

If you would like to read this report in a PDF format, please choose ‘Print this page’ and click the option to print to PDF. To include chart detail, select ‘Change to table and accessible view’

1. Executive summary

The overall levels of consumption of physical counterfeit goods remained steady with previous waves of research. Most respondents (76% in Wave 4) indicated that they had never knowingly purchased counterfeits. Despite slight fluctuations between waves, the top three reasons for not purchasing counterfeits were consistent. This includes not liking the quality of counterfeit products, concerns about supporting criminal activity, and the use of low-cost labour or poor working conditions.

Around a quarter (24%) of the sample said they had knowingly made a counterfeit purchase. This is a drop of 5 percentage points (pp) compared to the previous wave. A smaller proportion (15%) currently did so often, sometimes, or occasionally (a decrease of 4 pp compared to the previous wave).

Like previous waves, a strong correlation between age and counterfeit purchasing exists. Younger respondents are more likely to purchase counterfeits. Among those currently purchasing counterfeits, 27% were aged 25-34, 21% were aged 35-44, and 20% were aged 18-24. This contrasted with 14% of respondents aged 45–55 and only 7% of those aged 55 and above. In all age groups, 5-14% of respondents indicated that they used to buy counterfeits but no longer do.

Wave 4 of the counterfeit goods tracker showed that, in all categories, purchases stayed the same or fell. The most substantial decline compared to the previous wave was observed in “Toys” (falling by 5 pp to 9%), which returned to the level seen in Wave 2.“Clothing, footwear, and accessories” (12%) and “Sports” (12%) had the highest proportions of counterfeit purchasing.

There were some shifts in the sources of counterfeit purchases in Wave 4. Buying counterfeit goods in-person rose in several categories. These include “Sportswear from clubs/franchises” (+13 pp), “Electrical accessories” (+11 pp), and “Accessories excluding watches” (+10 pp). All other categories remained similar to Wave 3. Buying counterfeit goods online saw increases in the online purchase of “Cosmetic and toiletry products” (+6 pp) and a decrease in those purchasing “Electrical accessories” (-6 pp), “Regular sportswear” (-6 pp), and “Sportswear from clubs/franchises” (-5 pp). Whilst this wave had some fluctuations, the results remained consistent with the long-term trend observed seen the pre-COVID-19 Wave 1 and the post-COVID-19 waves afterward. This trend has seen in-person purchasing generally stay below the levels seen in Wave 1. It has also seen a sustained increase in online purchasing.

Messaging

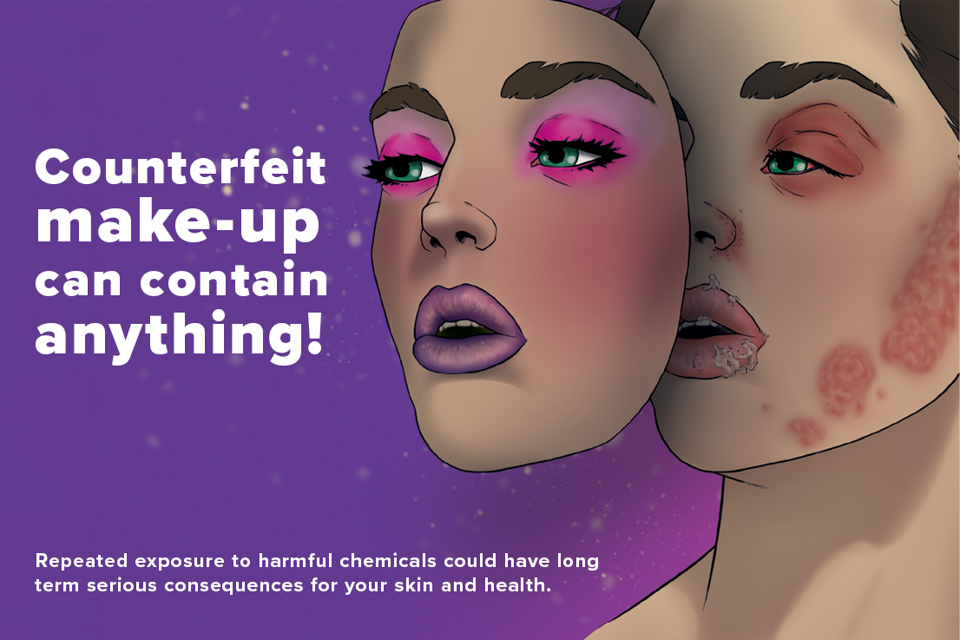

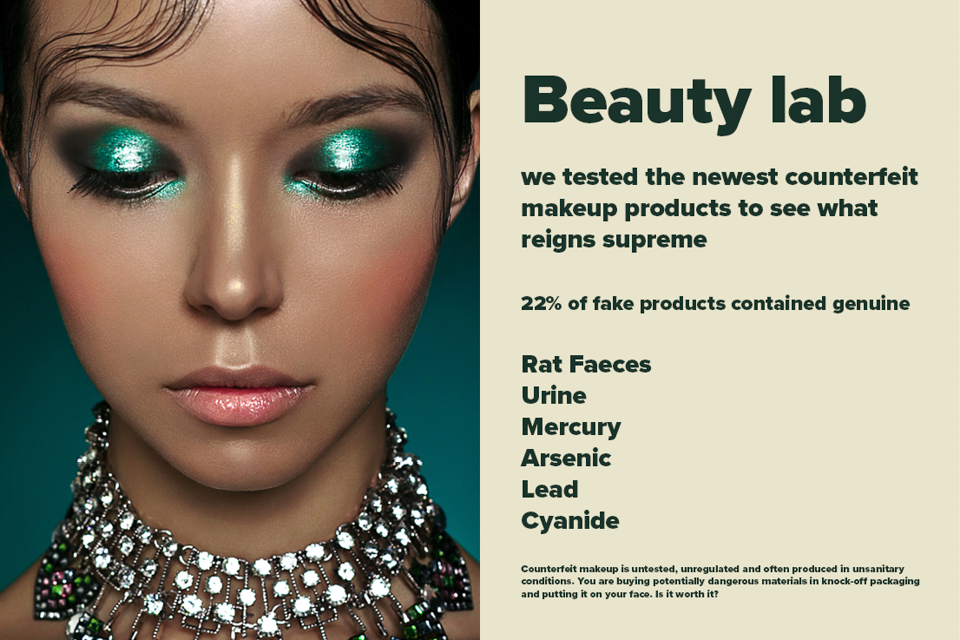

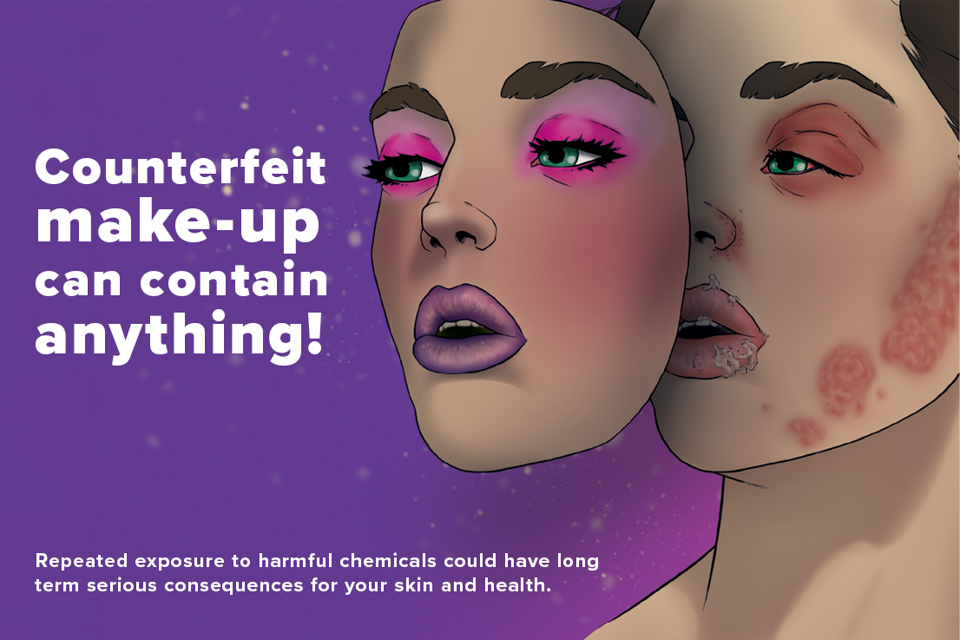

During the qualitative phase of research that followed the first survey, messaging aimed at reducing counterfeit purchasing was tested in an Online Community. The learning from this qualitative phase informed another iteration of behaviour change campaign messaging, which was subsequently tested in a second quantitative survey. In this wave, the focus was exclusively on the “Beauty and hygiene” category.

Respondents were presented with a total of nine messages and asked to assess the likelihood of each message dissuading them from purchasing various categories of counterfeit products:

- the same three messages proved most effective at both an overall level and across most subgroups, including sex, age, and whether respondents currently purchase, used to purchase, or were open to purchasing counterfeit items

- messages emphasising health and safety performed the best. They were closely followed by messages highlighting the societal impact of counterfeits, such as child labour, while messaging about the environment proved to be the least effective

- the consistent success of messages related to health and safety, in terms of addressing the dangers of purchasing counterfeits, underscores the potential effectiveness of a beauty and hygiene campaign centred around this overarching safety message

Recommendations

Younger respondents, specifically those under the age of 45, were the most active purchasers of counterfeit goods, making them the primary target audience for any behaviour change campaigns.

Consumers in certain product categories are consistently more likely to purchase counterfeits than others, though patterns of consumption in some categories are evolving. Categories like “Clothing, footwear, accessories”, and “Sports” have consistently shown high levels of counterfeit purchasing across all four waves of the study. Therefore, it may be pertinent to explore strategies for targeting these specific categories. On the other hand, “Toys”, which saw an increase in Wave 3, have returned to the levels observed in Wave 2.

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a noticeable increase in online purchasing of counterfeit goods, as evidenced in last year’s study. In this fourth wave of the tracker, it is evident that online purchasing has remained consistent, solidifying it as the dominant trend despite a resurgence of in-person purchasing in certain categories, such as “Sportswear from clubs/franchises”. This presents an opportunity to strategically consider where behaviour change interventions might be most effective in disrupting the consumer journey.

The second quantitative survey in this study, which assessed messaging efficacy, showed that several messages focusing on the impacts of counterfeit beauty and hygiene products could be impactful. While health and safety messages were generally the most effective, those related to the societal impact had a greater influence on younger respondents, specifically those aged under 35. This underscores the potential effectiveness of a behaviour change campaign that specifically targets the beauty and hygiene sector, as elaborated upon in the dedicated reporting section on communications.

Qualitative summary

Besides exploring the reasons why consumers purchase counterfeit goods and where they purchase from etc, the qualitative research also sought to understand the context for consumers at the time of the research. The Online Community this year showed that the current economic climate continues to have an impact on the lives and spending habits of participants, many of whom were having to find ways to spend less.

Participants reported trying to cut down on spending across a number of expenses and shopping in general. Therefore, some participants mentioned that they had either maintained the level of purchasing counterfeits from the previous year or increased upon their previous levels of counterfeit purchasing in order to keep costs down. There were no particular differences in regard to levels of purchasing mentioned qualitatively across categories, though interestingly a few of those who purchased fashion related counterfeits did say they would prefer to invest in better quality clothing and that they were worried about some of the practises involved in producing counterfeits. Nonetheless, they couldn’t necessarily afford to do so, but this shows that some participants are aware of and consider the negative aspects of purchasing counterfeits.

In relation to sourcing counterfeit goods, participants in our Online Community mostly went to online sources as a means of purchasing, valuing the ease and convenience as well as the opportunities to establish whether a seller seemed reliable from customer reviews. Some, though a lesser proportion (at least within our smaller qualitative sample), went to brick-and-mortar sources in person, with the benefit of being able to see, touch and evaluate a product before buying. Here markets abroad continued to play an important role, as well as some UK markets (Manchester’s markets came up a few times) and car boot sales.

Chiming with a new line of enquiry in the first quantitative survey this year, participants in the Online Community were asked about what they call counterfeit goods, and what came to mind when they heard the word ‘counterfeit’. Backing up the quantitative responses, many participants in the community mentioned using the words ‘fake’ and ‘knock off’ most commonly. Though most people understood what was meant by the term ‘counterfeit’, many saw this as a more formal way of expressing this type of product which they wouldn’t necessarily use themselves.

2. Methodology

Research aims

For many years, the IPO has sought to create a trackable and strong evidence base to inform decision making about physical counterfeits; the purchasing of counterfeit products, and attitudes towards doing so, in order to draw on this research in regard to policy and communications.

Given the continued success of the IPO’s Online Copyright Infringement (OCI) tracker, a decision was made to measure the purchasing of counterfeit products in the UK in the same way over time.

In 2019 a benchmark study was established, followed by the second wave in 2021 and a third in 2022. As with all previous waves, this wave, (the study’s fourth), continues to build on the evidence base year on year, whilst also taking into account the societal backdrop of the current year to ensure the findings are placed within context. The IPO is also keen to gather evidence that will help to facilitate behaviour change in consumers, based on their specific needs, and fostering greater respect for IP among those who are more actively seeking-out such goods.

Stage 1 (Quantitative)

As in previous years, the first stage of research comprised a large-scale, 15-minute, online survey among a representative sample of the UK adult population (aged 18+). Our sample size of N=5,000 has allowed us to conduct robust analysis at the total and sub-group level (e.g. by age, sex, SEG etc.). Importantly, it has allowed us to explore behaviours relating to a range of industries in-depth.

The survey was live between 16 June to 10 July 2023 and sample was sourced through our network of professionally managed (ESOMAR compliant) online UK consumer research panels. We have ensured that data is representative of the general population (by setting quotas and applying a weighting factor linked to population data released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS)). Respondents were asked about both their general and counterfeit purchasing history and habits across 6 broad product categories which (in total) covered 20 individual categories.

The fourth iteration of the Counterfeit Goods Tracker maintained consistency with previous waves across key metrics, allowing for wave-on-wave trend analysis. Additions were also made to expand and refine the insights gathered. The changes made included:

- routine tweaks to question wording and response options

- additional answer options to a question about factors likely to motivate people to purchase counterfeits, around family and friends or influencers recommending products

- two new sections looking into terminology around counterfeits, to try to ascertain which words the population use to refer to these products

Categories covered

Beauty and hygiene

- cosmetic and toiletry products

- hygiene products

Clothing, footwear and accessories

- clothing excluding sportswear

- footwear/shoes excluding sports footwear

- accessories excluding watches

- watches

Sports

- regular sportswear

- sportswear from clubs/franchises

- sports footwear (i.e. trainers) from sports or fashion brands

- sports equipment including for home workout

Toys

- dolls/action figure toys

- toy building sets

- merchandise from TV/Film excluding dolls/action figures

Electricals

- beauty/hygiene related electricals

- electrical accessories

- electrical devices

- DVDs and Blu Rays

Alcohol

- bottles of wine/champagne

- bottles of spirits (e.g. vodka)

- bottles/cans of beer or cider

Stage 2 (Qualitative)

The qualitative stage consisted of a week-long discussion in our Online Community platform, running from the 17 to 23 July 2023. An online community is a virtual research platform that enables the completion of a variety of tasks through either group discussions or private interactions. Its focus was to understand the reasons behind displayed attitudes and behaviours, especially given the continuing geopolitical context to 2023. The Online Community also sought to test behaviour change messaging and this year, only campaigns aimed at beauty and hygiene counterfeits were tested. This is due to having tested campaigns across all the categories for 3 years already and now seeing the opportunity to dig into individual product categories in more detail, on this occasion building on the IPO’s deep dive project into Beauty and hygiene counterfeits in 2021.

A total of 64 participants were recruited to take part in the Online Community, from a pool of respondents who had taken the survey in the previous stage of this study. Four categories were explored in depth in the qualitative research, due to high incidences of counterfeiting shown in these categories in the survey. As opposed to the survey in which categories were broken out into subcategories (e.g. Sportswear v Sports equipment), the qualitative research treated each category as a whole (e.g. sports overall), given the smaller sample size.

Within the Online Community sample, we focussed on those aged 35 and under, due to the higher incidences of counterfeit purchasing in these age groups, although some participants aged 36-54 were also included in order to understand any differences in behaviours. All participants were intentional purchasers of counterfeits and had knowingly purchased a counterfeit product in the last year.

The Online Community itself covered the following topics: the importance of each product category to participants; reasons for purchasing products in each category; methods of purchasing counterfeits; the 2023 context and its impact on rates of purchasing counterfeits; the language used to talk about counterfeits; and reactions to mocked up campaigns against the purchasing of beauty and hygiene counterfeits.

Categories covered

Beauty and hygiene

- cosmetic and toiletry products

- hygiene products

Clothing, footwear and accessories

- clothing excluding sportswear

- footwear/shoes excluding sports footwear

- accessories excluding watches

- watches

Sports

- regular sportswear

- sportswear from clubs/franchises

- sports footwear (i.e. trainers) from sports or fashion brands

- sports equipment including for home workout (e.g. rackets, bats, football, bikes, exercise machines etc.)

Electricals

- beauty/hygiene related electricals

- electrical accessories

- electrical devices

- DVDs and Blu Rays

Stage 3 (Message Testing - Quantitative)

Building on the in-depth, qualitative insight gained from the Online Community, the same beauty and hygiene-oriented campaigns were then put to respondents in a second survey to see whether robust numbers corroborated the initial qualitative findings.

These campaigns were tested in a survey with non-rejectors of counterfeits (including those who either had purchased, currently purchased or were open to purchasing counterfeit goods).

The survey explored whether each campaign would be likely to prevent respondents from purchasing beauty and hygiene counterfeits, along with some contextual questions to set the scene.

In total, n=1,500 completed the survey.

Fieldwork for this second survey took place between 28 July to 8 August 2023.

The survey included questions on the following topics:

- profiling (e.g. demographics)

- counterfeit purchasing history

- messaging evaluation (whether the information would be likely to impact their purchasing of beauty and hygiene counterfeits)

More information about the methodology can be found in the technical appendix

Interpreting the data

There are considerations to make when interpreting the data. Due to differences in the way some levels of infringement are captured, direct comparisons between infringements for certain categories should include methodology checks.

When comparing to previous waves, changes in behaviour regarding the purchasing of counterfeits precipitated due to COVID-19 should be borne in mind when making comparisons between the first and second waves.

Where questions were asked using a scale the full answer options have been included. Where (single choice) question percentages do not add up to 100%, this is due to rounding of the data.

If base sizes are below N=30, results must be interpreted with caution.

Margin of error: with any piece of research, it is almost never feasible to measure the entire population and thus achieve results that are 100% accurate. We must, therefore, take into account the potential for error. As a guide, we advise caution when interpreting results that have less than a (-/+) 3 or 4% difference.

Navigating this report

Throughout this report, there are references to waves 1-4. Research was carried out in the following years:

- Wave 1 – 2019

- Wave 2 – 2021

- Wave 3 – 2022

- Wave 4 (this report) – 2023

The report begins with an overview of counterfeit purchasing.

Each content category then has its own bespoke section. Qualitative insights are included for content categories covered within the Online Community.

Following this is a section which explores the effectiveness of messaging intended to reduce the amount of counterfeit purchasing.

The report ends with a summary of key findings relevant for future behaviour change campaigns. These results are largely based on the communications testing conducted in the qualitative research.

3. Overarching trends – Incidence, categories, motivations and barriers

This section provides an overview and comparison of key trends at an overall level of counterfeit purchases and a breakdown by category. It is based on the 2023 wave and includes yearly comparisons, where relevant, over the four years of the study. It covers the incidence rate of counterfeit purchasing, purchasing by category, reasons for purchasing / not purchasing counterfeit goods, the reporting of counterfeit purchasing, and the prices respondents are willing to pay for them.

Incidence rate of purchasing counterfeits

The proportion of people who currently, previously, or had never purchased counterfeit goods remained consistent with the first three waves of the study:

- the majority (76%) of respondents indicated that they had never purchased counterfeit goods while just under a quarter (24%) had done so

- 15% said they currently purchase counterfeit goods on an often, sometimes or occasional basis

- 9% used to buy counterfeit goods but no longer do, which is unchanged from the previous wave – of those who stopped, most (76%) did so over a year ago

Chart 1: Question. Which of the following best describes you in relation to purchasing “fake” or counterfeit items. By this we mean items that look very much like the original product but are not made by the brand itself. (By wave)

| Response | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NET Have ever made a counterfeit purchase | 28.8% | 26.7% | 29.0% | 24.0% |

| NET Have not purchased counterfeit goods | 71.2% | 73.3% | 71.0% | 76.0% |

| I often buy “fake” or counterfeit products (i.e. at least one every month) | 1.9% | 1.7% | 2.0% | 1.5% |

| I sometimes buy “fake” or counterfeit products (i.e. at least one every three months) | 5.0% | 4.2% | 5.0% | 4.0% |

| I occasionally buy “fake” or counterfeit products (i.e. less regularly than every three months) | 10.6% | 9.4% | 12.0% | 9.6% |

| I used to buy “fake” or counterfeit products but no longer do | 11.3% | 11.4% | 10.0% | 8.9% |

| I have never bought “fake” or counterfeit products but would consider doing so in future | 11.6% | 8.8% | 10.0% | 10.1% |

| I would never knowingly buy “fake” or counterfeit products | 59.6% | 64.5% | 61.0% | 65.9% |

Base: Total sample (n=5,072)

Chart 2: Question. When did you stop purchasing “fake” or counterfeit products?

Base: Those who have stopped purchasing counterfeits in the past year (n=451)

Incidence rate of purchasing counterfeits (by age and sex)

Respondents aged between 18-44 were more likely to indicate that they ‘currently’ purchase counterfeit goods, meaning they do so often, sometimes, or occasionally. This was highest among those aged 25-34, at 27%, followed by 21% for those aged 35-44 and 20% for those aged 18-24. It fell to between 7-14% for the two older age groups.

Compared to the previous wave, there were decreases in those ‘currently’ purchasing counterfeit goods in the two youngest age groups. It decreased by 11 pp to 20% in those aged 18-24 and 6 pp to 27% in those aged 25-34. There were minimal changes (i.e. +/- 3 pp) in all other age groups.

The purchase of counterfeit goods was higher among male (18%) than among female (13%) respondents. This marks a departure from last year when they were at the same level.

Chart 3: Question. Which of the following best describes you in relation to purchasing “fake” or counterfeit items. By this we mean items that look very much like the original product but are not made by the brand itself. (By age group and sex)

| Response | I often buy “fake” or counterfeit products (i.e. at least one every month) | I sometimes buy “fake” or counterfeit products (i.e. at least one every three months) | I occasionally buy “fake” or counterfeit products (i.e. less regularly than every three months) | I used to buy “fake” or counterfeit products but no longer do | I have never bought “fake” or counterfeit products but would consider doing so in future | I would never knowingly buy “fake” or counterfeit products | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-24 | 1.5% | 5.9% | 12.5% | 10.4% | 18.2% | 51.5% | 100% |

| 25-34 | 3.1% | 8.7% | 15.7% | 14.2% | 14.4% | 43.9% | 100% |

| 35-44 | 3.3% | 6.8% | 11.3% | 12.3% | 10.6% | 55.7% | 100% |

| 45-54 | 0.9% | 2.4% | 10.8% | 8.4% | 9.3% | 68.2% | 100% |

| 55+ | 0.4% | 1.0% | 5.2% | 5.1% | 6.3% | 82.0% | 100% |

| Female | 1.2% | 2.7% | 8.7% | 9.2% | 9.6% | 68.6% | 100% |

| Male | 1.9% | 5.3% | 10.6% | 8.6% | 10.6% | 63.0% | 100% |

Base: Total sample (n=5,072)

Product categories

The 24% who had knowingly purchased a counterfeit were asked which product categories they had purchased them in within the past year. They were only asked about the categories in which they had made a purchase. Chart 4 shows the proportion of consumers in each broad product category who had made a counterfeit purchase.

Respondents were most likely to have purchased counterfeit products from the “Clothing, footwear, and accessories” category (12%) and the “Sports” category (12%). Both experienced small declines of 3 pp and 2 pp, respectively; however, these changes were within the margin of error, so they should be interpreted with caution.

Among the remaining categories, “Toys” and “Electricals” both had similar levels of counterfeit purchasing (both 9%), while “Alcohol” had a rate that was 5 pp lower. “Toys” experienced the largest decline among all categories, falling by 5 pp to 9%, which is a return to the rate seen in Wave 2.

Chart 4: Question. Which, if any, of the following categories have you knowingly purchased “fake” or counterfeit products for in the past year? (By wave)

| Product categories knowingly purchased | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beauty and hygiene | 6.0% | 7.0% | 7.5% | 7.0% |

| Clothing, footwear and accessories | 12.8% | 14.2% | 14.3% | 12.4% |

| Sports | 8.6% | 11.8% | 14.7% | 12.2% |

| Toys | 5.2% | 9.0% | 13.8% | 9.0% |

| Electricals | 4.9% | 8.2% | 9.4% | 9.3% |

| Alcohol | 2.2% | 4.1% | 6.6% | 4.9% |

Base for Wave 4: Counterfeit purchasers as a percentage of consumers in each category: Beauty and hygiene (n=312), Clothing, footwear and accessories (n=568), Sports (n=344), Toys (n=166), Electricals (n=318), Alcohol (n=192)

Rationalisations for purchasing counterfeits

Anyone who had ever (i.e. currently or previously) purchased a counterfeit good or indicated that they would consider doing so in the future was presented with a list of potential motivating factors and asked how likely each would make them to purchase counterfeits. Their answers have been split out depending on whether they currently, used to, or would be open to buying counterfeit goods.

The top four factors, while stronger among current purchasers, were important for all. These four were selected by similar proportions within each segment, with factors related to money comprising the main theme - wanting to reduce spending/outgoing but also the price/cost-effectiveness of counterfeits. The desire for the product to closely match the original in terms of quality was also important.

Each of the top four factors was identified as motivations by 71-72% of current purchasers, 41-48% of former counterfeit purchasers, and 42-50% of those who would consider purchasing counterfeits in the future.

Of statements provided, respondents were least likely to mention that they purchased counterfeits due to hearing from an influencer or through social media that the products were of good quality, or because they did not want to support big brands.

Chart 5: Question. To what extent do or would the following influence/motivate you to purchase “fake” or counterfeit products? (By type of counterfeit purchaser)

5-point scale question – The NET is a combination of ‘Somewhat likely to purchase’ and ‘Very likely to purchase’ with other answer options including ‘Neither likely nor unlikely’, ‘Somewhat unlikely to purchase’ and ‘Very unlikely to purchase’)

| Purchasing influence/motivation | Currently purchases counterfeits | Used to purchase counterfeits | Would consider buying counterfeits in the future |

|---|---|---|---|

| Similar/the same quality | 72.3% | 48.5% | 50.3% |

| Wanting to reduce spending/outgoings | 72.0% | 47.9% | 47.0% |

| The ‘real’ product was out of your budget/price range | 70.9% | 47.1% | 45.4% |

| The ‘fake’ or counterfeit was cheaper | 72.0% | 41.1% | 42.5% |

| Hearing from family or friends that the ‘fake’ or counterfeit products were good | 64.8% | 41.9% | 39.4% |

| Similar/the same design | 64.6% | 37.3% | 40.5% |

| Being able to purchase ‘fake’ or counterfeit products easily | 60.5% | 29.4% | 31.3% |

| Not wanting to give money to big brand(s) | 50.2% | 26.0% | 30.9% |

| Hearing from an influencer or people on social media that the ‘fake’ or counterfeit products were good | 48.3% | 24.1% | 22.8% |

Base: Currently purchase counterfeits (n=767), Used to purchase counterfeits (n=451), Would consider buying counterfeits in the future (n=511)

Rationalisations for purchasing counterfeits (by age)

There were some key differences by age in terms of motivations for purchasing counterfeit goods:

- younger respondents were the most likely to be influenced by most of the motivations tested

- in each case, individuals aged 18-24 were the most likely to indicate that it would make them likely to purchase a counterfeit product, 25-34-year-olds ranked as the second most likely group for each category, followed by 35-44-year-olds as the third most likely, and so forth

- the two exceptions were the ability to purchase counterfeit goods easily and hearing from an influencer that the products were good – in these cases, those aged 25-34 were more likely than the 18-24 age group to express that these factors would influence their purchasing decisions

Chart 6: Question. To what extent do or would the following influence/motivate you to purchase “fake” or counterfeit products? (By age group)

5-point scale question – The NET is a combination of ‘Somewhat likely to purchase’ and ‘Very likely to purchase’ with other answer options including ‘Neither likely nor unlikely’, ‘Somewhat unlikely to purchase’ and ‘Very unlikely to purchase’)

| Purchasing influence/motivation | 18-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Similar/the same quality | 55.4% | 46.1% | 35.6% | 24.6% | 16.1% |

| Wanting to reduce spending/outgoings | 50.1% | 44.8% | 33.6% | 25.1% | 14.4% |

| The ‘real’ product was out of your budget/price range | 51.0% | 41.4% | 32.7% | 23.7% | 13.4% |

| The ‘fake’ or counterfeit was cheaper | 49.4% | 38.9% | 29.7% | 21.7% | 12.5% |

| Hearing from family or friends that the ‘fake’ or counterfeit products were good | 42.5% | 39.0% | 30.4% | 19.8% | 13.5% |

| Similar/the same design | 39.3% | 37.4% | 29.2% | 20.0% | 11.8% |

| Being able to purchase ‘fake’ or counterfeit products easily | 30.0% | 32.3% | 24.6% | 14.8% | 9.0% |

| Not wanting to give money to big brand(s) | 33.6% | 31.4% | 22.2% | 15.5% | 9.2% |

| Hearing from an influencer or people on social media that the ‘fake’ or counterfeit products were good | 26.7% | 29.5% | 19.9% | 10.9% | 5.5% |

Base: All respondents from each age group – 18-24 (n=512), 25-34 (n=833), 35-44 (n=862), 45-54 (n=912), 55+ (n=1,990)

Rationalisations against purchasing counterfeits

Those who did not ‘currently’ (i.e. often, sometimes or occasionally) purchase counterfeit goods were asked why they didn’t. They were grouped into one of the following: would never buy them; used to buy them but wouldn’t anymore; and those who would consider buying them in the future.

No single reason was dominant in any of the groups. The top three reasons across all groups related to not liking the quality of the products as well as more moral considerations (e.g. worrying about supporting criminal activities, use of low cost labour/poor working conditions).

Chart 7: Question. What are/were your main reasons for not purchasing “fake” or counterfeit products? (By counterfeit purchasing)

Multiple choice question (i.e. respondents were asked to select all options that apply)

| Reasons for not purchasing | Would never buy counterfeits | Would consider buying counterfeits in the future | Use to purchase counterfeits |

|---|---|---|---|

| I would be worried about supporting criminal activity | 53.5% | 26.5% | 36.3% |

| Use of low cost labour or poor working conditions | 42.9% | 28.3% | 44.0% |

| I do not like the quality of ‘fake’ or counterfeit products | 40.9% | 38.5% | 45.3% |

| I would be worried that the product could have harmful effects (e.g. leading to allergies etc.) | 33.8% | 21.0% | 27.0% |

| ‘Fake’ or counterfeit products harm/damage the real brands | 33.5% | 19.4% | 24.4% |

| The negative impact they have on the environment | 24.9% | 15.0% | 19.2% |

| I would be worried about getting in trouble | 18.7% | 15.3% | 14.0% |

| I do not like the design of ‘fake’ or counterfeit products | 17.8% | 14.6% | 17.9% |

| ‘Fake’ or counterfeit products can be similar in price to real ones | 9.1% | 11.8% | 16.4% |

| Fear of being judged by other people for purchasing a ‘fake’ or counterfeit | 8.6% | 12.9% | 15.4% |

| Other | 7.8% | 7.8% | 3.8% |

Base: Would never buy counterfeits (n=3,343), Used to purchase counterfeits (n=451), Would consider buying counterfeits in the future (n=511)

Rationalisations against purchasing counterfeits (by age)

There were some key differences by age in terms of the reasons given for why people don’t currently purchase counterfeits:

- there were several reasons with clear age correlations, for example, worrying about supporting criminal activity and harming/damaging the real brand had a much larger impact on older respondents – for each, 55+ year olds were the most likely to identify this as a reason for not purchasing counterfeits, with the proportions dropping with subsequent age groups

- the inverse was true for fear of being judged and not liking the quality or design; 18-24-year-olds were the most likely to be impacted, with the proportions dropping as age rose

- negative impact on the environment had a bigger impact on those aged 18-24 compared with all other age groups

- worry about getting into trouble had similar impact across different age groups

Chart 8: Question. What are/were your main reasons for not purchasing “fake” or counterfeit products? (By age group)

Multiple choice question (i.e. respondents were asked to select all options that apply)

| Reasons for not purchasing | 18-24 | 25-34 | 35-44 | 45-54 | 55+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I would be worried about supporting criminal activity | 35.3% | 34.3% | 42.0% | 50.4% | 57.6% |

| Use of low cost labour or poor working conditions | 46.6% | 34.8% | 38.8% | 37.5% | 44.7% |

| I do not like the quality of ‘fake’ or counterfeit products | 49.9% | 46.3% | 44.0% | 42.3% | 35.9% |

| I would be worried that the product could have harmful effects | 30.3% | 24.2% | 33.1% | 31.4% | 33.7% |

| ‘Fake’ or counterfeit products harm/damage the real brands | 21.2% | 25.9% | 27.8% | 31.2% | 35.6% |

| The negative impact they have on the environment | 32.5% | 19.8% | 19.5% | 21.0% | 24.3% |

| I would be worried about getting in trouble | 13.4% | 17.4% | 20.7% | 19.4% | 17.2% |

| I do not like the design of ‘fake’ or counterfeit products | 23.4% | 22.5% | 20.3% | 16.4% | 13.9% |

| ‘Fake’ or counterfeit products can be similar in price to real ones | 17.4% | 12.0% | 12.4% | 8.0% | 8.1% |

| Fear of being judged by other people for purchasing a ‘fake’ or counterfeit | 22.6% | 14.9% | 13.8% | 8.0% | 4.7% |

| Other | 8.5% | 4.7% | 6.9% | 6.6% | 8.6% |

Base: Doesn’t currently purchase counterfeit products (n=4,305)

Methods of making counterfeit purchases

For each category in which they had made a counterfeit purchase, respondents were asked where they had made that purchase. Comparison to previous waves make it possible to identify potential shifts in shopping habits. Answer options have been grouped for in-person purchases (e.g. in-store, local markets, markets abroad) and online ones (e.g. online from a global e-commerce site, online from a smaller retailer, online from a seller abroad).

Compared to Wave 3, in-person counterfeit purchasing increased in several categories, such as “Sportswear from clubs/franchises” (+13 pp), “Electrical accessories” (+11 pp), and “Accessories excluding watches” (+10 pp). “Sportswear from clubs/franchises” was the only category where in-person counterfeit purchasing levels were higher than in Wave 1. In all other categories, they were either in line with or, in most instances, lower than the levels seen in Wave 1.

Compared to Wave 3, there was an increase in the online purchase of “Cosmetic and toiletry products” (+ 6 pp) and a decrease in those purchasing “Electrical accessories” (-6 pp), “Regular sportswear” (-6 pp), and “Sportswear from clubs/franchises” (-5 pp) online. All other categories remained within +/- 4 pp of Wave 3 levels.

When looking across all four waves, the sharp decline of in-person purchasing and the increase in online counterfeit purchasing that occurred between waves one and two were likely heavily influenced by the state of the pandemic. In Wave 4, while some categories are at a similar level to Wave 1 in terms of in-person purchasing, most remain somewhat below. Online purchasing continues to remain relatively stable at levels that are those seen in the pre-pandemic Wave 1.

Chart 9: Question. And in which of the following ways do you tend to purchase ‘fake’ or counterfeit products …? (By wave)

Results show NET of in-person purchasing.

| Product category | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmetic and toiletry products | 60.0% | 43.0% | 42.6% | 45.7% |

| Hygiene products | 68.0% | 51.0% | 54.7% | 53.3% |

| Clothing excluding sportswear | 67.0% | 46.0% | 52.3% | 54.7% |

| Footwear/shoes excluding sports footwear | 63.0% | 42.0% | 49.5% | 50.5% |

| Accessories excluding watches | 65.0% | 53.0% | 51.2% | 60.9% |

| Regular sportswear | 56.0% | 54.0% | 46.7% | 52.4% |

| Sportswear from clubs/franchises | 39.0% | 41.0% | 37.7% | 50.8% |

| Sports footwear (i.e. trainers) from sports or fashion brands | 70.0% | 45.0% | 49.8% | 45.7% |

| Electrical accessories | 41.0% | 40.0% | 29.2% | 40.4% |

Results show NET of online sources of purchasing.

| Product category | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmetic and toiletry products | 54.0% | 66.0% | 62.0% | 68.0% |

| Hygiene products | 47.0% | 66.0% | 68.0% | 63.6% |

| Clothing excluding sportswear | 46.0% | 60.0% | 59.0% | 57.4% |

| Footwear/shoes excluding sports footwear | 48.0% | 63.0% | 66.0% | 61.8% |

| Accessories excluding watches | 44.0% | 55.0% | 55.0% | 51.2% |

| Regular sportswear | 50.0% | 51.0% | 64.0% | 58.3% |

| Sportswear from clubs/franchises | 66.0% | 69.0% | 71.0% | 66.0% |

| Sports footwear (i.e. trainers) from sports or fashion brands | 48.0% | 66.0% | 61.0% | 61.9% |

| Electrical accessories | 70.0% | 76.0% | 78.0% | 71.5% |

Base for Wave 4: Counterfeit purchasers of each category: Cosmetic and toiletry products (n=212), Hygiene products (n=140), Clothing excluding sportswear (n=315), Footwear/shoes excluding sports footwear (n=160), Accessories excluding watches (n=191), Regular sportswear (n=138), Sportswear from clubs/franchises (n=95), Sports footwear (i.e. trainers) from sports or fashion brands (n=133), Electrical accessories (n=165)

Future counterfeiting purchasing

New for this year, three quarters (77%) indicated that they would be (NET) unlikely to purchase counterfeit products in the next two years.

Chart 10: Question. Overall, across any category you purchase, how likely would you be to purchase “fake” or counterfeit products in the next two years? (By sex and age group)

5-point scale question – The NET is a combination of ‘Very likely and ‘Somewhat likely’ with other answer options including ‘Neither likely nor unlikely’, ‘Somewhat unlikely’ and ‘Very unlikely’)

| Response | Respondents answering “very likely”/”somewhat likely” (NET likely %) |

|---|---|

| Total | 11.1% |

| Female | 9.0% |

| Male | 13.3% |

| 18-24 | 17.0% |

| 25-34 | 20.4% |

| 35-44 | 18.1% |

| 45-54 | 7.8% |

| 55+ | 4.2% |

Base: Total sample (n=5,072)

Unintentional counterfeit purchasing

Respondents were asked whether they had ever ‘unintentionally’ purchased a counterfeit good. Overall, 17% had done so with most (55%) of this group having done so over a year ago. This is in line with the first wave of the study where 16% had made an unintentional purchase.

At 21%, male respondents were 8% more likely to have done so than female respondents. Those aged 25-44 were also more likely to be unintentional purchasers. Between 24-26% of those aged 25-44 had done so, which fell to 19% in those aged 18-24, 18% in those aged 45-54 and 9% in the 55+.

Chart 11: Question. Have you ever unintentionally purchased “fake” or counterfeit products? (By sex and age group)

| Response | Respondents answering “yes” (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 16.7% |

| Female | 13.0% |

| Male | 20.6% |

| 18-24 | 18.6% |

| 25-34 | 25.5% |

| 35-44 | 24.2% |

| 45-54 | 17.9% |

| 55+ | 8.8% |

Base: Total sample (n=5,072)

Chart 12: Question. When did you last unintentionally purchase a “fake” or counterfeit product?

Base: Unintentionally purchased a counterfeit product (n=846)

The 17% who had unknowingly purchased a counterfeit were asked which product categories they had purchased them in within the past year (respondents were only asked about the categories they had made purchases in). Chart 13 shows the proportion of consumers in each broad product category who had made a counterfeit purchase.

They were most likely to have unintentionally made purchases in “Clothing, footwear and accessories” (7%), “Sports” (7%), “Toys” (6%) and “Electricals” (6%). Respondents were less likely to have unintentionally purchased counterfeit “Beauty and hygiene” (4%) and “Alcohol” (3%) products.

Compared to the previous wave there seems to have potentially been a slight decrease in unintentional purchasing in some “Toys” (-2 pp). All other categories remained stable.

Chart 13: Question. Which, if any, of the following categories have you unintentionally purchased “fake” or counterfeit products for in the past year? (By wave)

| Product category | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beauty and hygiene | 3.5% | 4.2% | 4.0% | 3.9% |

| Clothing, footwear and accessories | 6.1% | 7.5% | 6.7% | 6.8% |

| Sports | 3.6% | 6.8% | 7.3% | 6.6% |

| Toys | 3.2% | 5.2% | 8.1% | 6.1% |

| Electricals | 3.2% | 5.9% | 6.3% | 6.1% |

| Alcohol | 0.7% | 2.3% | 3.5% | 2.6% |

Base for Wave 4: Unintentional counterfeit purchasers as a percentage of consumers in each category: Beauty and hygiene (n=186), Clothing, footwear and accessories (n=312), Sports (n=186), Toys (n=112), Electricals (n=208), Alcohol (n=101)

Alcohol purchasing

Due to the specific nature of counterfeit alcohol, in Wave 3 and 4 purchasers of legitimate alcohol products who had ever purchased counterfeits were asked a question regarding their awareness of counterfeit alcohol and purchasing habits that could mitigate the risk of unintentionally purchasing counterfeit alcohol products.

Over half of legitimate alcohol purchasers (51%) were not previously aware that there are counterfeit alcohol products. Those that expressed awareness were furthermore more likely to agree with the statement “I think I was aware” (28%) than with “I was definitely aware” (24%).

Respondents were most likely to not take any specific actions when buying alcohol. Others were cautious, checking the bottle, branding, and packaging for legitimacy. Some avoid overly cheap products, while a few consider the product’s origin.

Chart 14: Question. Do you take any of the following steps before or after purchasing alcohol products?

| Response | Overall (%) |

|---|---|

| I do not do anything specific | 38.3% |

| Not buy something if it seems too cheap | 21.0% |

| Buy alcohol products where the branding etc, is in English | 20.5% |

| Check the packaging looks legitimate | 19.1% |

| Check the branding looks legitimate | 18.2% |

| Check the bottle looks legitimate | 18.2% |

| Check where the product was made | 12.9% |

| Buy alcohol products where the branding etc. is in a language other than English | 9.2% |

Base: Alcohol consumers who have ever purchased counterfeits in any category (n=988)

Unintentional purchasing

The (n) of respondents who had made an unintentional purchase in any category were asked how they felt about it:

- the emotions felt are consistent with the previous wave - many respondents felt angry after their purchase, with this most likely to be directed at the person/company who sold them the product (38%) or themselves for not spotting it (36%)

- respondents were more likely to feel indifferent about their purchase (19%) than be angry at the authorities (14%) or the brand they had intended to purchase (14%)

- though anger was, by some way, the most common response to unintentionally purchasing a counterfeit item, a small proportion (13%) indicated that they were pleasantly surprised at the quality of the counterfeit product

Chart 15: Question. How did you feel after unintentionally purchasing “fake” or counterfeit product(s)? (By wave)

| Response | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|

| I felt angry at the person/company who sold me the ‘fake’ or counterfeit | 37.5% | 38.2% |

| I felt angry at myself for not spotting it | 36.5% | 35.9% |

| I felt indifferent about it | 18.8% | 18.8% |

| I felt angry at the brand/company whose product I thought I was buying | 10.9% | 14.2% |

| I felt angry at the authorities for allowing the sale | 15.3% | 14.2% |

| I was pleasantly surprised by how good the quality of the product was | 15.1% | 13.0% |

| Other | 3.6% | 2.4% |

Base for Wave 4: Unintentionally purchased a counterfeit product (n=846)

The base for this question is different to the previous one. It was asked to respondents who had unintentionally made a purchase across any product category in the past year and had taken action following this (e.g. had reported it to someone). They were asked about the main reason they reported the seller:

- the most common reason was to get a refund (42%), which was followed by those who weren’t happy with the quality of the product (28%) – in both instances, these percentages were 4 pp higher than in Wave 3

- less common reasons were wanting to stop the seller from operating (14%) or because of potential links to other criminal activity (14%), both of which were at a similar level to the previous wave

Chart 16: Question. After unintentionally purchasing a “fake” or counterfeit product you said you took an action. What was your main reason for reporting the seller of the fake product? (By wave)

| Response | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|

| To get a refund | 37.9% | 42.3% |

| The quality of the product | 24.2% | 28.4% |

| The seller’s potential links to other criminal activity | 12.5% | 13.8% |

| To attempt to stop the seller from operating | 16.0% | 13.9% |

| Other | 9.3% | 1.6% |

Base for Wave 4: Took an action after unintentionally purchasing a counterfeit product (n=323)

The base for this question is different to the previous one. Those who had unintentionally made a counterfeit purchase within the past year were asked specifically if they had ever used a reporting system:

- a fifth (20%) indicated that they had done so which was 5 pp lower than in Wave 3

- a further 42% expressed that they would use such a reporting system in the future

- a quarter (26%) felt that they would need to know more about the system, while just 12% said outright that they wouldn’t use one

Chart 17: Question. Most online platforms have reporting systems in relation to the sale of “fake” or counterfeit products, would you consider using these? (By wave)

| Response | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, I have used these previously | 24.7% | 20.2% |

| Yes, I would in the future | 41.4% | 42.2% |

| I would need to know more about the systems | 23.4% | 25.6% |

| No | 10.5% | 12.1% |

Base for Wave 4: Unintentionally purchased a counterfeit product (n=846)

The base for this question is different to the previous one. Those who had made an unintentional counterfeit purchase in the past year but chose not to use a reporting system were asked about the main reasons for this:

- the most common reasons were related to a lack of concern (34%); a similar proportion mentioned not knowing how to use the online reporting system (22%) or believing it would be too time-consuming (22%)

- a smaller number of respondents mentioned that they believed the platform would not take any action based on their report (11%)

- a relatively small percentage of respondents (7%) indicated that they wouldn’t use the reporting tool because they preferred to report it in a different way, such as to law enforcement

- there were some shifts compared to the previous wave, such as a 6 pp decrease in the number of respondents who believed that the platform would not take any action based on their report (it’s important to bear in mind the relatively small sample size [n=102] when making these comparisons)

Chart 18: Question. What is the main reason you would not consider using the online platform’s reporting system? (By wave)

| Response | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|

| I don’t care enough to report it | 29.5% | 33.7% |

| I don’t know how | 27.3% | 22.0% |

| Too time consuming | 17.8% | 22.0% |

| The platform won’t do anything with my report | 17.3% | 11.5% |

| I would report it using other means e.g. Law enforcement | 7.0% | 6.6% |

| Other | 1.1% | 4.3% |

Base for Wave 4: Had made an unintentional counterfeit purchase in the past year and wouldn’t consider using an online platform to report a counterfeit product (n=102)

Reporting

All 5,072 respondents were asked a series of questions regarding the reporting of counterfeit sources. These questions were first introduced in wave 3.

Respondents were asked if they had ever reported a source/site or individual for selling “fake” or counterfeit products, if they had ever considered doing so, or if they were aware that doing so was a possibility. Based on their answers, respondents were then asked a set of follow up questions regarding the outcome of any reports that had been made, which organisations were reported to, and the motivation behind taking action against counterfeits, as well as not taking action.

Types of action taken

The types of action that were taken were consistent with Wave 3:

- just over one in ten (11%) had previously reported either a source/site (7%) or an individual (6%) for selling “fake” or counterfeit products

- 9% had considered reporting a source (6%) and/or an individual (4%)

- the largest group, representing 39% of the sample, expressed that that they were unaware that “fake” or counterfeit products could be reported

Chart 19: Question. Have you ever reported/considered reporting a source/site or an individual who was selling “fake” or counterfeit products? (By wave)

| Response | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|

| I have reported a source/site before | 6.2% | 7.0% |

| I have reported an individual before | 5.4% | 5.8% |

| I have considered reporting a source/site before | 5.8% | 5.7% |

| I have considered reporting an individual before | 3.9% | 4.2% |

| No - I was aware that “fake” or counterfeit products could be reported but have not done so | 25.7% | 28.7% |

| No - I was not aware that “fake” or counterfeit products could be reported | 42.4% | 38.8% |

| Don’t know/not sure | 14.9% | 14.7% |

Base: Total sample (n=5,072)

Organisations reported to

The (n=554) respondents who had reported “fake” or counterfeit products were shown a list of organisations and asked, for each organisation: whether or not they were aware of the organisation, if they thought that infringement could be reported to them, and whether or not they had done so.

Respondents were most likely to have been aware that they could report “fake” or counterfeit items to the source of their purchase, and to have done so:

- 85% had reported (24%) or were aware they could report (60%) to the store in which they had brought the item while 82% either had reported (34%) or were aware they could report (48%) to the online platform where they had made the illegitimate purchase

- both the police (77%), a local trading standards department (77%) and the brand (72%) also had high levels of combined reporting and respondent awareness

- reporting and awareness of the ability to report was lowest for search engines (56%), Citizens Advice (61%) and Action Fraud (65%)

Chart 20: Question. Here are some bodies/organisations that you can report content infringement to. For each, tell us which option best represents your knowledge/relationship with them.

| Type | Aware and have reported to them | Aware that you can report to them | Unaware that you can report to them | Unaware of them | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A local trading standards department | 23.0% | 53.2% | 15.5% | 8.3% | 100.0% |

| Action Fraud | 20.2% | 45.2% | 16.0% | 18.7% | 100.0% |

| The police | 19.7% | 57.2% | 19.4% | 3.8% | 100.0% |

| Citizens Advice | 20.2% | 41.0% | 30.7% | 8.2% | 100.0% |

| Crime Stoppers | 17.0% | 49.8% | 23.7% | 9.6% | 100.0% |

| The online platform where you bought the item | 33.7% | 47.9% | 13.1% | 5.3% | 100.0% |

| The store where you bought the item | 24.5% | 60.2% | 10.8% | 4.5% | 100.0% |

| The brand | 21.0% | 51.1% | 21.7% | 6.2% | 100.0% |

| Search engine | 18.2% | 37.8% | 35.2% | 8.7% | 100.0% |

Base: Those who had reported a source/site or individual (n=554)

Outcome of actions

For each organisation, respondents who had reported a “fake” or counterfeit item were asked about the outcome of their action. Due to small sample sizes, these results should be interpreted with caution:

- a local trading standards department was the most likely to have taken action, having done so for 56% of respondents who had reported to them – however, fewer than one in ten (8%) had received a refund of their money

- Citizens Advice had taken action in 54% of cases, followed by the Police and Action Fraud, both at 53%

- all other organisations were known to have taken action in 47-51% of cases

- interestingly, respondents were most likely to receive a refund when reporting to the online platform where the purchase had been made or the shop where they had bought the item, even though these two options had some of the lowest levels of overall awareness

Chart 21: Question. Do you know if any action has been taken since you reported the source/site or individual?

| Type | Yes, action has been taken and I received my money back | Yes, action has been taken | No, to my knowledge action has not yet been taken | I am unaware if action has or will be taken | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A local trading standards department | 8.4% | 47.7% | 26.8% | 17.1% | 100.0% |

| Action Fraud | 9.5% | 43.7% | 25.0% | 21.9% | 100.0% |

| The police | 8.9% | 44.3% | 28.9% | 17.8% | 100.0% |

| Citizens Advice | 5.6% | 48.3% | 28.7% | 17.3% | 100.0% |

| Crime Stoppers | 3.1% | 44.1% | 32.5% | 20.3% | 100.0% |

| The online platform where you bought the item | 17.1% | 31.9% | 27.6% | 23.4% | 100.0% |

| The store where you bought the item | 13.9% | 34.5% | 28.7% | 22.9% | 100.0% |

| The brand | 4.6% | 45.1% | 25.9% | 24.5% | 100.0% |

| Search engine | 2.8% | 48.2% | 30.5% | 18.5% | 100.0% |

Base: Those who had reported to each organisation (n=74-159)

Reasons for and against taking action

Those who had taken action or have considered doing so were also asked their reasons for doing so. Results were consistent with the previous wave, with moral issues (45%) the most prominent concern, followed by being personally affected by fraud/cybersecurity (34%) or malware/viruses on their devices (26%).

Chart 22: Question. Why did you report or consider reporting a source/site or an individual who was selling “fake” or counterfeit products? (By wave)

| Response | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|

| I have moral issues with those selling “fake” or counterfeit products | 43.9% | 44.9% |

| Due to concerns about or being personally affected by malware, viruses etc. on devices | 30.1% | 26.4% |

| Due to concerns about or being personally affected by fraud or cyber security | 35.1% | 33.6% |

| To get my money back on “fake” or counterfeit products I had knowingly purchased | 11.9% | 16.0% |

| To get my money back on “fake” or counterfeit products I had unknowingly purchased | 22.3% | 20.7% |

| Other | 3.1% | 3.7% |

Base: Those who had reported or considered reporting a source/site or individual (n=902)

Those who had not taken action were also asked their reasons for doing so:

- slightly more than a third (35%) expressed that, to their knowledge, they had never come across anyone selling “fake” or counterfeit items

- other common reasons related to awareness – 20% did not know who/where to report to, while 17% did not know that reporting was an option

Chart 23: Question. Why have you never reported a source/site or individual who was selling “fake” or counterfeit products? (By wave)

| Response | Wave 3 | Wave 4 |

|---|---|---|

| To my knowledge, I have never come across anyone selling “fake” or counterfeit products | 34.8% | 35.3% |

| I do not know who/where to report to | 19.9% | 19.8% |

| I did not know reporting was an option | 16.9% | 16.8% |

| I do not think me reporting it will make a difference/impact | 13.1% | 13.1% |

| I do not have the time | 7.5% | 6.7% |

| Reporting process was unclear/too complicated | 6.1% | 6.0% |

| I am worried that it might have a negative impact on me (e.g. if the infringers find out I reported them) | 5.1% | 5.3% |

| Other | 3.1% | 3.5% |

| None of the above | 15.9% | 16.0% |

Base: Those who had not reported a source/site or individual (n=4,518)

An in-depth look at price

Respondents who were open to purchasing counterfeits (i.e. they either currently did so or were considering doing so in the future) were asked about three different pricing scenarios for counterfeit products using the Van Westendorp pricing model. This is where, for each scenario, they were asked at what point the product would be too expensive, expensive, cheap or too cheap. They were told the price of the genuine product in each of these scenarios.

Scenario 1:

Chart 24: A “fake” or counterfeit bottle of perfume of a brand which you or someone you know likes. The ‘real’ item would usually retail at £70.

For a counterfeit perfume worth £70 the optimal price point that respondents were willing to pay was £25 (36% of the value of the genuine items). The price point of marginal cheapness (i.e. when people would start to doubt the quality of the product) was £20.50 while the point of expensiveness (i.e. when the cost is becoming a major concern) was £35. The point of indifference (i.e. when they start to feel the price is starting to become expensive) was £30.

Scenario 2:

Chart 25: A “fake” or counterfeit kit for your favourite football team that you or someone you know supports. The ‘real’ item would usually retail at £100.

For a counterfeit football kit worth £100 the optimal price point that respondents were willing to pay was £32.50 (32.5% of the value of the genuine items). The price point of marginal cheapness (i.e. when people would start to doubt the quality of the product) was £29 while the point of expensiveness (i.e. when the cost is becoming a major concern) was £49. The point of indifference (i.e. when they start to feel the price is starting to become expensive) was £40.

Scenario 3:

Chart 26: A “fake” or counterfeit handbag of a brand that you or someone you know likes. The ‘real’ item would usually retail at £1,500.

For a counterfeit handbag worth £1,500 the optimal price point that respondents were willing to pay was £200 (13% of the value of the genuine items). The price point of marginal cheapness (i.e. when people would start to doubt the quality of the product) was £150 while the point of expensiveness (i.e. when the cost is becoming a major concern) was £350. The point of indifference (i.e. when they start to feel the price is starting to become expensive) was £250.

4. Category Insights

This section provides infographics that explore counterfeit purchasing, encompassing both intentional and unintentional instances, with infographics at both broad and individual category levels. It furnishes data on the incidence rate of counterfeit purchasing at an overall level and among sub-groups. Additionally, it examines where respondents are making these purchases, their reasons for doing so, the amount they spend, and the counterfeit brands corresponding to the goods they purchase.

Intentional counterfeit purchasing

Beauty and hygiene

Here are the key highlights from the beauty & hygiene infographic, which includes insights from individuals who have deliberately purchased counterfeit goods:

- 94% of the total sample had purchased a beauty and hygiene product in the last year

- 7% of those who purchased beauty and hygiene products in the last year had purchased counterfeit products in that category

- 6% of those who purchased hygiene products in the last year had purchased counterfeit products in that category

Of those who had purchased beauty and hygiene counterfeits in the last year:

Sex:

- male: 6%

- female: 7%

Age:

- 18-24: 15%

- 25-34: 13%

- 35-44: 11%

- 45-54: 4%

- 55+: 3%

Social Grade:

- ABC1: 7%

- C2DE: 6%

Passion level for category:

- high: 12%

- medium: 7%

- low: 3%

This infographic highlights key findings about cosmetics and toiletry products, based on insights from the 6% of consumers in this category who knowingly purchased counterfeit products within this category in the past year. All figures presented here pertain solely to the purchase of counterfeit goods within this category.

Purchase frequency:

- monthly (14%)

- every 3 months (20%)

- every 6 months (19%)

- once a year (19%)

- less than once a year (28%)

Recipients:

- myself (78%)

- family (29%)

Reasons for purchase:

- cheaper price (48%)

- similar quality (39%)

- save money (36%)

Average annual spend: £137

Top counterfeited brands:

- Calvin Klein (25%)

- Chanel (21%)

- Hugo Boss (20%)

Source of purchase:

- global e-commerce (31%)

- in-store retailers (28%)

- social media (27%)

If unavailable, would:

- buy similar, cheaper (24%)

- buy from brand (50%)

- go without (20%)

- unsure (7%)

This infographic highlights key findings about hygiene products, based on insights from the 3% of consumers in this category who knowingly within this category in the past year. All figures presented here pertain solely to the purchase of counterfeit goods within this category.

Frequency of purchase:

- monthly (27%)

- every 3 months (31%)

- every 6 months (19%)

- once a year (7%)

- less than once a year (16%)

Recipients:

- myself (75%)

- family (33%)

Reasons for purchase:

- cheaper price (37%)

- save money (34%)

- similar quality (31%)

Average annual spend: £190

Top counterfeited brands:

- Head & Shoulders (33%)

- Dove (32%)

- Carex (26%)

Source of purchase:

- in-store, not from brand (42%)

- global e-commerce (31%)

- social media (28%)

If counterfeits were not available, they would:

- buy similar, cheaper (49%)

- buy from brand (36%)

- go without (6%)

- unsure (9%)

Qualitative Insight – Cosmetics, toiletry and hygiene products

The importance of cosmetic, toiletry and hygiene products for consumers

For many participants, beauty and hygiene products were an important part of daily life and said to be intrinsic to their sense of wellbeing, confidence, identity and even empowerment as mentioned especially by a few female participants. These products were very much involved in a sense of self care, both from a practical side (i.e. keeping clean) but also an emotional side (i.e. helping boost confidence either through skincare, make-up or perfumes and aftershaves).

Most commonly purchased counterfeit cosmetic, toiletry and hygiene products

Though of course a small sample, by far the most purchased types of counterfeit beauty and hygiene product in our community were perfumes and aftershaves. This was because of the reportedly high price of original versions of branded perfumes and aftershaves and the huge savings which could be made by purchasing counterfeit versions which replicated the scents of luxury brands quite accurately. These types of counterfeit products were also seen as relatively risk free in comparison with other products such as skincare, make-up etc.

There were only a couple of reports of any other products in this year’s Online Community, namely a few mentions of make-up and skincare. Most of these mentions were in fact of replica own brand products bought from high street stores rather than counterfeits. These sources were still deemed reliable or at least not dangerous to people’s health, whereas purchasing counterfeit skincare or make-up products did concern many people who worried about the potential damage which could be done to their skin.

Reasons for purchasing counterfeit cosmetic, toiletry and hygiene products

As in previous years, the key reason for purchasing counterfeit cosmetic, toiletry and hygiene products is cost and looking for products which are going to save people money. Many participants were feeling a financial strain and were looking for ways to save money across all of their outgoings, meaning counterfeit beauty and hygiene products were particularly attractive, especially as they were products which participants made use of on a near daily basis.

Another factor for a minority was curiosity and simply trying things out, even without the end goal being as financially motivated. A few simply saw the possibility of trying out products in a different way and from different sources and wanted to try counterfeit products in order to see whether they could be an option.

Changes to purchases of counterfeit cosmetic, toiletry and hygiene products

The context to this particular wave was one in which many were struggling with budgets. Though no longer a year of COVID-19 related lockdowns as in previous waves but with the war in Ukraine continuing to inflate prices, many said that the previous hardship of the pandemic was now being exacerbated by a rise in prices across various products.

Therefore, some said their purchases of counterfeits had gone up because they had started shopping online more since the pandemic and came across more counterfeit items, or because they wanted to continue to enjoy little luxuries like their favourite self-care staples such as perfumes and fragrances whilst cutting down on cost.

A few said they had not bought either more nor less counterfeits, sticking to a certain regularity of purchasing over the years, with the reason as ever to save money on certain purchasers.

Others said they were overall trying to save money across all products regardless of their origin and had therefore bought less counterfeit products than previously.

Sources of counterfeit cosmetic, toiletry and hygiene products

Most bought from e-commerce sites, including online marketplaces, auction sites and mobile shopping apps. This was the most convenient place to purchase such products but also offered a level of control to consumers due to the fact that they could read reviews left by others and decide whether they felt a seller seemed reliable. Most were happy with this way of purchasing, rarely coming across any issues. Though one thing mentioned when asked about the security of payments, was that with online marketplaces such as eBay, participants felt relatively protected in regard to their payments whereas payments through Facebook marketplace involved risks.

In addition to online, some also bought counterfeit beauty and hygiene products in person; car boot sales and markets were mentioned by a few. These participants thought of these purchasing occasions as an opportunity to see and feel the products before purchasing them or sometimes even part of a day out.

The most common way participants had discovered these sources were either through googling or through word of mouth and ads online.

To save money and to get similar quality perfume but with half of the price. Before the pandemic I never tried cheaper perfumes, so quality and cheaper prices are 2 main reasons.

Male, 35, Beauty and Hygiene

The main reason is due to cost. The products are much cheaper and you can get similar quality to what you get from the actual manufacturer.

Male, 31, Beauty and Hygiene

Because they are cheaper. It means you get more for your money and can spend money on other things that you may need.

Female, 34, Beauty and Hygiene

Clothing, footwear and accessories

Here are the key highlights from the clothing, footwear and accessories infographic, which includes insights from individuals who have deliberately purchased counterfeit goods:

- 90% of the total sample had purchased a clothing, footwear and accessories product in the last year

- 12% of those who purchased clothing, footwear and accessories in the last year had purchased counterfeit products in that category

- 8% of those who purchased clothing (excluding sportswear) in the last year had purchased counterfeit products in that category

- 5% of those who purchased footwear/shoes (excluding sports footwear) in the last year had purchased counterfeit products in that category

- 10% of those who purchased accessories (excluding watches) in the last year had purchased counterfeit products in that category

- 9% of those who purchased watches in the last year had purchased counterfeit products in that category

Of those who had purchased clothing, footwear and accessories counterfeits in the last year:

Sex:

- male: 14%

- female: 11%

Age:

- 18-24: 16%

- 25-34: 25%

- 35-44: 18%

- 45-54: 10%

- 55+: 5%

Social Grade:

- ABC1: 12%

- C2DE: 13%

Passion level for category:

- high: 23%

- medium: 12%

- low: 7%

This infographic highlights key findings about clothing products, based on insights from the 8% of consumers in this category who knowingly purchased counterfeit products within this category in the past year. All figures presented here pertain solely to the purchase of counterfeit goods within this category.

Frequency of purchase:

- monthly (9%)

- every 3 months (13%)

- every 6 months (19%)

- once a year (17%)

- less than once a year (42%)

Recipients:

- myself (76%)

- family (28%)

Reasons for purchase:

- cheaper price (53%)

- similar design (41%)

- spend less (39%)

Average annual spend: £80

Top counterfeited brands:

- Gucci (28%)

- Louis Vuitton (19%)

- High street brands (19%)

Source of purchase:

- global e-commerce (30%)

- local markets on holiday (25%)

- local markets in the UK (20%)

If counterfeits were not available, they would:

- buy similar, cheaper (36%)

- go without (33%)

- buy from brand (20%)

- unsure (11%)

This infographic highlights key findings about footwear and shoe products, based on insights from the 5% of consumers in this category who knowingly purchased counterfeit products within this category in the past year. All figures presented here pertain solely to the purchase of counterfeit goods within this category.

Frequency of purchase:

- monthly (14%)

- every 3 months (14%)

- every 6 months (16%)

- once a year (14%)

- less than once a year (43%)

Recipients:

- myself (79%)

- family (22%)

Reasons for purchase:

- cheaper price (53%)

- spend less (40%)

- similar design (39%)

Average annual spend: £183

Top counterfeited brands:

- Gucci (34%)

- Ralph Lauren (17%)

- Timberland (17%)

Source of purchase:

- global e-commerce (33%)

- in-store, not from brand (20%)

- local markets in the UK (20%)

If counterfeits were not available, they would:

- buy from brand (49%)

- buy similar, cheaper (28%)

- go without (9%)

- unsure (6%)

This infographic highlights key findings about accessories products, based on insights from the 10% of consumers in this category who knowingly purchased counterfeit products within this category in the past year. All figures presented here pertain solely to the purchase of counterfeit goods within this category.

Frequency of purchase:

- monthly (10%)

- every 3 months (7%)

- every 6 months (14%)

- once a year (19%)

- less than once a year (49%)

Recipients:

- myself (77%)

- family (22%)

Reasons for purchase:

- cheaper price (51%)

- spend less (43%)

- design looks similar (42%)

Average annual spend: £83

Top counterfeited brands:

- Gucci (34%)

- Louis Vuitton (29%)

- Chanel (21%)

Source of purchase:

- local markets on holiday (29%)

- global e-commerce (24%)

- local markets in UK (22%)

If counterfeits were not available, they would:

- go without the product (36%)

- buy a similar product from a cheaper brand (34%)

- buy the product directly from the brand (20%)

- not sure/don’t know (10%)

Here are the key highlights from the watches products infographic, based on insights from the 9% of consumers in this category who knowingly purchased counterfeit products in the past year in this category. All figures in the infographic pertain to the purchase of counterfeit goods in this category.

Frequency of purchase:

- monthly (17%)

- every 3 months (15%)

- every 6 months (14%)

- once a year (13%)

- less than once a year (41%)

Recipients:

- myself (74%)

- family (26%)

Reasons for purchase:

- cheaper price (49%)

- design looks similar (41%)

- spend less (38%)

Average annual spend: £223

Top counterfeited brands:

- Apple (38%)

- Rolex (21%)

- Burberry (17%)

Source of purchase:

- global e-commerce (34%)

- social media (24%)

- online sellers abroad (23%)

If counterfeits were not available, they would:

- buy a similar product from a cheaper brand (36%)

- go without the product (29%)

- buy the product directly from the brand (26%)

- not sure/don’t know (7%)

Qualitative Insight – Clothing, shoes and accessories

The importance of clothing, shoes and accessories for consumers

This category of products was extremely important to participants, as a daily necessity but also something which expressed their personality and could make participants feel comfortable in themselves.

Most popular types of counterfeit clothing, shoes and accessories

Participants bought a wide variety of products across the overall clothing, shoe and accessories spectrum. From T-shirts and jumpers replicating well-known premium brands, to one-off leather jackets, trainers and jackets. Watches were also popular, as well as handbags and sunglasses, all imitating major brands who participants couldn’t otherwise afford.

Reasons for purchasing counterfeit clothing, shoes and accessories

For the participants in our Online Community, price was the most commonly mentioned factor motivating them to purchase counterfeits. They felt that for a much cheaper price they were able to get something which looked the same and which they believed to be of good quality.

A few said that often the counterfeit items lasted for a good time and that therefore, they didn’t see the benefit of paying for a brand when they received the same aesthetics and sometimes even the quality to last matching the real product also. A couple even mentioned enjoying going around markets on holiday and that sometimes picking up a counterfeit item was a part of the experience of being at certain locations abroad.

Despite the obvious price benefits, there were nonetheless concerns mentioned; most commonly around the quality of products, but also a few mentions of concern for how the products were made and who by, as well as a few mentions of the risk of being scammed. These show that while purchases are seen as financially necessary sometimes, people are not always comfortable with them.

Changes to purchases of counterfeit clothing, shoes and accessories

Some participants directly cited the increase in prices over the last couple of years and said that their purchasing of counterfeit goods had increased out of necessity and having to cut down on spending. For some, this overlapped with circumstantial events such as children growing and needing new clothing regularly which stretched budgets even further.

Only a couple said their purchasing had decreased, due to their salaries picking up since the pandemic but many said they were still purchasing the same amount of counterfeits as before, seeing a need to buy cheaper items or unwilling to pay the prices for original products.

Sources of counterfeit clothing, shoes and accessories

Most participants bought counterfeit clothing, shoes and accessories online but interestingly for this category, there were a few who said they exclusively bought these counterfeit products when at markets abroad on holiday, a couple even reporting going back to the same country (in this instance, Turkey) and buying there every time. Added to these physical sources were markets in the UK (a couple of participants from Manchester mentioned Cheetham Market and this having been somewhere they bought regularly before the police raids on this area) as well as car boot sales which allowed some participants who took these routes to touch the fabric and material first.

Regarding online sources, eBay, Amazon, Etsy and Alibaba were commonly mentioned as go-to sources on which participants could browse easily and read up through reviews left by others, informing a decision to purchase. These sites were often discovered through Google searches, word of mouth recommendations or social media adverts on Instagram, Facebook etc. A couple of participants mentioned seeing people review their counterfeit purchases and where they brought them from on TikTok.

I’m trying to save money across all fronts. I have purchasing counterfeits a little bit more on a few things for my kids, just a couple of pairs of trainers and bags that would have been much more expensive for the real thing.

Male, 52, Clothing, accessories and footwear