International development in a contested world: ending extreme poverty and tackling climate change. A white paper on international development

Updated 22 January 2024

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Affairs by Command of His Majesty

November 2023

CP 975

© Crown copyright 2023

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at:

Communications Team

OSHR Directorate

Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office

King Charles Street

SW1A 2AH

ISBN 978-1-5286-4460-0

E02987341 11/23

Foreword by the Prime Minister

The impact of COVID-19, climate change, conflict, and migration show how events that begin overseas affect our people at home. These issues have significant global human and economic consequences. The United Kingdom is uniquely placed to help address these challenges at source, using our science and technology expertise, our position as a global financial centre and our extensive diplomatic network.

The Rt Hon Rishi Sunak MP, Prime Minister

Testimonials

Dr Akinwumi A Adesina, President of the African Development Bank:

In response to calls for the Multilateral Development Banks to reform, the African Development Bank is innovating to respond to the polycrisis affecting Africa. I value the partnership with the UK government, which has supported us to stretch our balance sheet and mobilize private investment to meet these challenges, and look forward to consolidating this partnership for the implementation of the white paper.

His Excellency Nana Akufo-Addo, President of the Republic of Ghana:

Building beyond aid is crucial for equal partnerships, where voices of developing countries are heard and respected. I welcome the UK’s recognition of a new, more equal partnership with Ghana and Africa, and the need for African voices to be heard.

Ajay Banga, President of the World Bank:

The scale and complexity of the challenges we face requires turning big ideas into action and partnerships into progress. It will require all shoulders to the wheel because no one has a monopoly on good ideas. We should steal shamelessly and share seamlessly. And we must do it with - and among - think tanks, the private sector, civil society, and anyone who is working to move the needle. The ideas the UK is putting forward in this white paper are part of that communal mission.

Professor Malcolm Chalmers, Deputy Director-General, Royal United Services Institute:

Most of the world’s poorest people are concentrated in countries afflicted by conflict. Conflict reduction therefore needs to be at the heart of tackling extreme poverty. As the white paper recognises, diplomacy can be just as important as financial assistance in tackling the obstacles to development in such contexts.

Jan Egeland, Secretary-General, Norwegian Refugee Council:

I welcome the UK’s commitment to partnerships with us in local and international NGOs based on mutual respect. We cannot achieve the progress needed unless we can make partnerships more equal.

Bill Gates, Co-Chair, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation:

The UK’s commitment to addressing global inequities, and this ambitious agenda for positive change, are much needed as the world faces unprecedented challenges. Our foundation will continue to join with the UK in the development and delivery of innovative tools and effective responses to the health and development issues that affect the world’s poorest people.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General, World Health Organization:

A comprehensive approach to strengthening health systems is vital. I commend the UK for the spirit of equal partnerships and learning set out in the International Development white paper.

Her Excellency Samia Suluhu Hassan, President of the United Republic of Tanzania:

Tanzania reaffirms its drive for actions that provide global solutions to climate change and reform of the international financial system. I welcome the UK’s commitment to long-term partnerships, built on mutual respect, that put equal emphasis on women and girls and finding a fair path to stronger trade, investment and sustainable economic growth.

Sir Mo Ibrahim, Founder and Chair of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation:

Improving governance of public finances is critical for accelerating the SDGs. As vital are the actions needed to increase the amount of resources available for low and middle income countries to finance their own development. I welcome the white paper’s focus on reform of the multilateral banks and the broader international financial system.

Amina Mohammed, UN Deputy Secretary-General:

We have only 7 years to deliver on the promise of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. The time for bold and audacious action has arrived…. cooperation can bring us closer to a more sustainable, equitable, and prosperous world, as envisioned by the SDGs. Let us work together to get there and to leave no one behind!

Honourable Mia Amor Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados:

I welcome the deep commitment to multilateralism. There is no other way to beat global challenges. It is good to see global public goods like climate, health and bio-diversity alongside ending poverty as critical objectives. And I value the call to reshape the international financial system to serve everyone.

Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Director-General, World Trade Organization:

The WTO’s purpose of ensuring a free and fair multilateral trading system that supports developing countries to create jobs, enhance living standards and deliver on sustainable development is crucial for delivering on the SDGs. We therefore welcome the UK International Development’s goal of achieving the SDGs through ending extreme poverty, tackling climate change and biodiversity loss, because, like the WTO’s purpose of enhancing living standards, creating jobs, and supporting sustainable development, it puts people squarely at the centre of development! Together we can deliver for developing countries.

Samantha Power, Administrator of the United States Agency for International Development:

The United Kingdom and the United States have a critical and longstanding partnership in international development. Together, our countries are tackling some of our greatest global challenges: preventing famine, bolstering health systems decimated by the pandemic, combating the climate crisis, and rebuilding trust in democratic institutions. As this white paper highlights, the UK is moving toward a locally-led development approach to help take on these challenges – a critical shift for driving sustainable and enduring change.

Lord Ricketts, former Permanent Under-Secretary, Foreign & Commonwealth Office:

With the world more divided and unstable than at any time since the end of the Cold War, a leading British role in international development is crucial. I welcome the white paper’s clarity of purpose in tackling the SDGs, climate change and biodiversity loss.

His Excellency Dr William Ruto, President of the Republic of Kenya:

The UK-Kenya strategic partnership exemplifies high level political commitment to shared prosperity. I welcome this white paper and its vision for international cooperation to reverse deepening poverty and inequality, tackle climate change and accelerate the realisation of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Ahmed Shide, Minister of Finance, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia:

The ‘UK’s and Ethiopia’s development cooperation in recent years has put partnership at its core: building resilient government institutions, leveraging new investment from the private sector and adapting to new challenges. I welcome the focus in this white paper on long-term, patient development, done in partnership.

Professor Jim Skea, Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change:

The science and the evidence is clear, unless ambitious action is taken to combat climate change, we will not be able to secure development goals. We need a step change. Now is the time for action.

Lord Stern of Brentford, Chair of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics:

Climate Change and biodiversity loss are existential challenges. Failure to act with urgency and on scale will have devastating effects on prospects for development, undermine poverty reduction, exacerbate conflict, and push the world further off track on the SDGs. The future progress for all SDG’s rests on the actions we take on energy, climate, and nature, both now and in the future.

Dr Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury:

Partnership lies at the heart of this white paper on international development. Working together, across faiths and nations is essential so that we can deliver change that benefits our future generations.

Dr Chrysoula Zacharopoulou, Minister of State for Development, Francophonie and International Partnerships, France:

France, which recently adopted a new policy paradigm shifting away from aid towards a solidarity and sustainable investment strategy, welcomes the bold vision set out in this white paper.

UK and France are close partners on global development and the protection of global public goods. We look forward to strengthening our shared efforts to build a fairer and liveable world for everyone. This is the spirit of the Paris Pact for the People and Planet already endorsed by more than 40 countries.

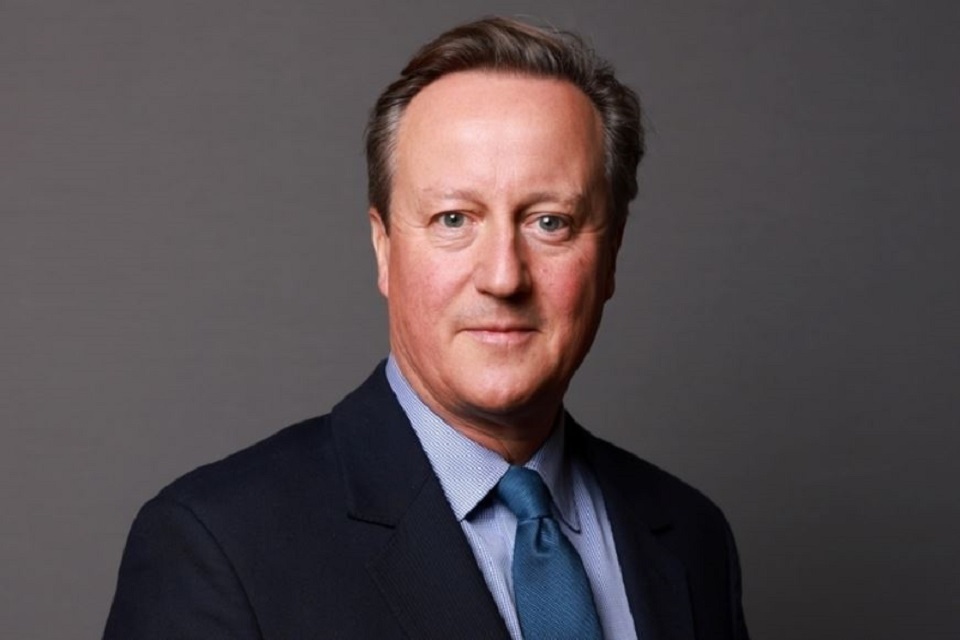

Foreword by the Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs

Ten years ago, I co-chaired a panel for the United Nations on the future of development. Our report paved the way to the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals.

Since then, international development has become both more vital and more difficult.

More vital as the scale of the challenge has grown. We are off track on the 2015 Goals. 701 million people remain in extreme poverty. Climate change’s impact on lives and livelihoods is accelerating, affecting developing countries the most.

More difficult because the world of development has changed. The traditional donor-recipient model of the past is not working as it was. Additionally, fragile and conflict-affected states are a much bigger part of the problem.

The 2015 Goals were a remarkable achievement. For the first time, the world recognised that sustainable development requires action on climate change and achieving gender equality. That it depends on peace, justice and strong institutions. That we wanted to end poverty in all its forms everywhere. Crucially, we made these promises to every country and person on the planet – nobody would be left behind.

This destination remains unchanged. But our approach needs to adapt to new realities. The white paper captures how we are doing that.

We have to understand the importance of fragility and conflict in shaping development outcomes. Conflict has stalled or even reversed progress in too many places, with humanitarian needs at their highest since 1945. Soon half the world’s poorest will live in fragile or conflict-affected states, with a lack of state capacity and respect for the rule of law, high levels of corruption and enduring ethnic or political divisions.

Today’s answer cannot be about rich countries ‘doing development’ to others. We need to work together as partners, shaping narratives which developing countries own and deliver. Development cannot be a closed shop, where we try to help other countries and communities without heeding their vision for the future.

Equally important is development finance’s catalytic role. For 75 years, the UK has been a reliable lender for projects able to transform lives. As the first donor to mobilise pension fund assets to fund development, British International Investment continues to lead the way. We also see a major opportunity to scale up finance from multilateral development banks – greater support from shareholders coupled with reforms could unlock hundreds of billions of dollars over the next decade.

Our approach is grounded in partnerships. Britain has real development expertise, within government and beyond. But we do not have all the answers. We must work with others, especially those whose lives are blighted by poverty and injustice.

Development has the capacity to save and improve lives. It is part of a moral mission. And in a world of illegal migration, climate change, instability and conflict, it is essential for our own security and prosperity as well.

We are global. We are interconnected. We need to do development smartly, for the benefit of the British people and the world.

The Rt Hon David Cameron, Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs

Preface

Minister Mitchell at the new container port at Ndayane, Senegal. The UK has a $1.7 billion partnership between British Investment International (BII) and DP World for developing ports in Africa.

Back in 2005, when I was first asked to take on the international development brief, I accepted with a mixture of relish and scepticism. A banker by background, I was fluent in the language of global finance, but knew little of the humanitarian world. Even as an MP with ties to local NGOs, international development was not an issue I actively engaged in. I was curious, yet unconvinced this world was the right place for me – or for that matter, that I was the right person for it.

It did not take long for any trepidation to melt away. Conscious that I had a lot to learn, I was under no illusion about the gargantuan task ahead, and the role swiftly became a labour of love. I quickly understood the power of results, seeing how our support was having life transforming impacts. I was also impressed by the ingenuity and creativity of what the UK was doing – government and NGOs – and by how much our partners valued our efforts and approach. To this day, I believe that to be an international development minister is more than a privilege; it is the best job in the world.

The role today is vastly different from when I was first in government. The world has changed. The needs of countries, societies and people have evolved. Old problems have not gone away, but new challenges are rapidly surfacing. We know that poverty, conflict, and climate change often go hand in hand. Climate change does not respect national boundaries, and neither do pandemics. There is growing interest in job security, investment in growth and digitalisation. All of which necessitate a radical rethink of the way the UK responds to challenges and opportunities, based on an honest acceptance that what may have worked well in the past may not be right for the future.

This white paper is a roadmap to 2030. It represents the UK’s answer to a world that is under huge stress: a world which until recently, made great strides in reducing poverty, but is presiding over a dramatic fall back into poverty; where faith in multilateral institutions is fading, at a time when cooperation is needed more than ever; where the climate is heating up, conflict is spreading and the prospect of pandemics is looming.

It is a world which exceeded many of the ambitious expectations of the Millennium Development Goals, but is falling woefully behind our targets to meet the Sustainable Development Goals.

The SDGs give us the possibility of great global progress. But the scale of the challenges means we have to go beyond traditional ideas of aid. We need an ambitious yet achievable development offer fit for our time, workable within financial constraints and which delivers the best of Britain’s financial, scientific and diplomatic capabilities and assets.

Crucially, we need an offer based on partnership and mutual respect, giving leaders, communities and individuals a voice in shaping the solutions they want to see, rather than accepting the ones we think they need.

This white paper has drawn on the sharpest and most expert minds in the business: NGOs, academia, the private and financial sector, youth activists, our partners abroad, and all political parties in the UK. The quality of creativity and intellectual agility is as illuminating as it is instructive.

It is clear to me that how we mobilise finance, spend effectively and deliver results is central to success. At a time of domestically straitened budgets, the paper makes the case that the traditional model of doing international development needs to change, and go far beyond the parameters of UK Official Development Assistance.

A whole chapter is dedicated to this quest literally to ‘mobilise the money’. It charts the UK’s plans to deliver a quantum leap in the volume of finance that our partners need to reinvigorate the SDGs and help face down the threats of climate change. The UK is pioneering new approaches to debt so repayments are immediately paused when vulnerable countries are hit by extreme weather events or health emergencies. I will be pressing our partners to follow our example with this simple innovation that will make such a huge difference.

We will also champion a scale up of the financing capacity of international financial institutions by stretching their balance sheets, while working with institutional investors, including pension funds and the wider private sector, to boost their investment in low- and middle-income countries. Harnessing our capabilities and expertise will help ensure that each penny embedded in the Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) goes as far as possible.

The UK’s work on women and girls is paramount. I have always said that we cannot understand development unless we see it through the eyes of girls and women. Increasing access to education, supporting family planning and combating sexual violence is central to creating conditions for economic opportunity and growth. These rights are universal and should be non-negotiable.

We will use research and diplomacy to deliver on our campaign to End the Preventable Deaths of mothers, babies and children. We will deploy policy and investment to defend strongly and to advance sexual and reproductive health and rights, including safe abortion.

We will do this through a reinvigorated approach to partnerships with women’s rights and other local organisations. We will partner with national leaders, women’s groups and other experts, to test and scale-up creative ways to drive forward change.

The private sector perhaps best illustrates how the UK makes a difference, while delivering back for the taxpayer many times over. The private sector is the engine of development, providing the building blocks for economic independence. Its activity not only generates jobs and drives growth, it provides the tax receipts for governments to fund public services and develops the technologies that help end extreme poverty and critically, engender self-sufficiency.

BII, the UK’s investment arm of development, is engaged across many projects to bring this aspiration to life. Building on its impressive record of success, BII will go further and faster to invest in the hardest places, aiming to make over half of its investments in the poorest and most fragile countries by 2030. BII will also become one of the most transparent development financial institutions, cementing its place as a world leader in this field.

Finally, science and technology will drive all of these agendas forward. Science is not only the future, it may be the answer to our survival. But it goes beyond the tangible difference it makes, or the hope it offers. Science is partnership in action: Partnerships between scientists here and abroad, with academic institutions, between businesses and government. Partnerships which bring together intelligence and creativity to address problems money alone will never solve.

The world has never been so intimately connected, nor our fates so closely entwined. Our participation in delivering the SDGs is needed more than ever. But only cooperation and partnership will help us forge ahead. If we are serious about building a safer and more prosperous world for future generations, then it falls upon all of us to try to model in our actions, the kind of world they deserve to inherit.

Rt Hon Andrew Mitchell MP, Minister for Development and Africa

Minister Mitchell meeting representatives of the Africa Youth Climate Assembly in Nairobi, Kenya. They discussed the Nairobi Youth Climate Declaration and the content of this international development white paper.

Introduction

Why this white paper?

In 2015, the world gathered at the United Nations to agree the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a development framework for people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership for development, to be achieved by 2030. This universal framework linked the aims of investing in people’s health and education, tackling poverty, building the prosperity and jobs that economies need, supporting peace and security, and protecting our fragile planet.

At half-way point, the SDGs are off-track and impacts of climate change and nature loss are accelerating. Only 15% of the SDG indicators are due to be met. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly set back development progress. Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine increased energy and food insecurity around the world. An increasing number of countries are in severe debt and unable to access affordable finance to grow their economies. Conflict is increasing in many parts of the world. In a contested and volatile world, global development co-operation is more difficult, but more important, than ever.

A prosperous and secure world, where the SDGs are back on track, and where developing countries achieve their development aims, is in the world’s interests. Global development co-operation is essential to tackle challenges that do not respect borders. It is necessary to build the open and stable international order in which all countries, including the United Kingdom (UK), can secure their interests, and in which we and others can prosper. Migration, where properly managed, can be a win-win. Co-operation is the foundation for tackling climate change and biodiversity loss, for growing trade and commercial opportunity, for improving security and reducing conflict – which we in the UK also stand to benefit from.

The global context for development has changed. The UK approach to development needs to change with it. Developing countries want and need a different development offer, based on mutual respect, powered by development finance at scale, and a more responsive multilateral and international system. The development progress required to meet the SDGs in 2030 needs much more than aid; it needs global policy change, a greater role for the private sector, for science and technology, and a whole-of-UK effort for international development.

What is the strategy?

The goal of UK international development is to end extreme poverty and tackle climate change and biodiversity loss. Achieving this goal and meeting the SDGs is only possible if all countries achieve sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

This white paper sets out a re-energised international development agenda, for the UK, working with our partners, based on the following priorities:

-

going further, faster to mobilise international finance to end extreme poverty, tackle climate change and biodiversity loss, power sustainable growth and increase private sector investment in development

-

strengthening and reforming the international system to improve action on trade, tax, debt, tackling dirty money and corruption, and delivering on global challenges like health, climate, nature and energy transition

-

harnessing innovation and new technologies, science and research for the greatest and most cost-effective development impact

-

ensuring opportunities for all, putting women and girls centre stage and investing in education and health systems that societies want

-

championing action to address state fragility, and anticipate and prevent conflict, humanitarian crises, climate disasters and threats to global health

-

building resilience and enabling adaptation for those affected by conflict, disasters and climate change, strengthening food security, social protection, disaster risk financing and building state capability

-

standing up for our values, for open inclusive societies, for women and girls, and preventing roll-back of rights

How will we deliver?

Patient and mutually respectful relationships will be central. The UK will listen to and champion the asks of developing countries in the international system. Our country partnerships will focus on supporting countries’ own plans, prioritising their capability and building their resilience. We will model transparency in how we shape and deliver our development offer.

We will work closely with partners to promote global action. We will strengthen alignment between the UK’s development and diplomatic capabilities – including civil society, research and science, and the private sector.

We will ensure our development offer responds to locally owned priorities and contexts. We will ensure grant aid is focused on the lowest income countries and delivered as far as possible through local institutions and organisations. In middle-income countries, we will build development finance that leverages the private sector, and harnesses UK expertise.

We will bolster multilateralism with stronger voice and representation from the lowest income countries. We will work with our partners to shape the global development agenda, building international ambition and collective resolve to deliver the SDGs. Our development offer will support stronger co-operation across multilateral and international organisations, and greater co-ordination and effectiveness in delivery.

Chapter 1: The challenge we face

1.1. In 2015 the world gathered to agree Agenda 2030 and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Agreed by all 193 UN member states as a framework of 17 goals and 169 targets, these are a universal commitment for people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership. The UK is proud of its role working with other countries to create the SDGs, which represent truly collective ambition and a shared vision for a better world by 2030.

1.2. Sustainable development is fundamental to an open and stable international order. As set out in the Integrated Review Refresh 2023, development makes the world safer, freer, more prosperous and greener. It supports our own security and prosperity. Ensuring that everyone has the opportunity of a good life, tackling climate change and nature loss, enabling inclusive growth, building peace and preventing conflict, is in the UK’s interests in a more contested and volatile world.

Decades of progress under threat

1.3. The development gains of recent decades are now under threat of reversal. Hard-won progress has stalled since 2015. Latest figures show that 701 million people remain in extreme poverty, predominantly in Sub-Saharan African countries.[footnote 1] Much of this slowdown has been caused by weak economic growth. But the growth challenge has been exacerbated by conflict, energy insecurity, loss of nature and environmental degradation.[footnote 2] The long-term impacts from the COVID-19 pandemic have reversed progress, including in education, health and gender equality. Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine has added to pressure on energy and food prices, and reduced supply into international markets, creating a risk of further deterioration in global food security.

1.4. The impacts of climate change and nature loss are being felt by everyone, everywhere. Extreme weather, sea level rise and ecosystem collapse are accelerating, with the impacts felt most acutely in developing countries. It is estimated that climate change and biodiversity loss will increase food prices by 20% for billions of low-income people.[footnote 3] Climate change and biodiversity loss are enablers of other global threats,[footnote 4] they further compound risks of insecurity and instability, and drive migration.

1.5. Conflict state fragility and instability are on the rise and holding back development, with the impacts spreading in affected regions, as seen in the growing challenges faced in the Sahel and the Middle East. In 2022, there were 55 violent conflicts and a 97% increase in deaths on the previous year. The human costs of conflict are high and rising, with women and children particularly affected. In 2022, conflict and insecurity were the most significant causes of high levels of acute food insecurity for around 117 million people in 19 countries and territories.[footnote 5] Up to two-thirds of the world’s extreme poor will live in fragile and conflict-affected contexts by 2030.[footnote 6]

1.6. Humanitarian needs are at their highest since 1945. Approximately 360 million people need humanitarian assistance in 2023, twice as many as 5 years ago. It is estimated that 80% of humanitarian need is driven by conflict. In 2022, humanitarian appeals to respond to all crises were only 58% funded, leaving significant unmet needs.[footnote 7]

Figure 1: Stalling progress

Following stalled progress since 2015, the COVID-19 pandemic dealt the largest setback to global poverty reduction efforts in decades.

Progress in poverty reduction has stalled

Source: World Bank estimates based on Mahler, Yonzan, and Lakner, forthcoming; World Bank, Poverty and Inequality Platform, https://worldbank.org; World Bank, Global Economic Prospects database.

Figure 1 description

- 1990 to 2013 are described as historic data

- 2013 to 2020 are described as slowing poverty reduction

- 2020 to 2030 is a current projection

| Year | Millions of people living in extreme poverty |

|---|---|

| 1990 | 1996 |

| 1991 | 2005 |

| 1992 | 1990 |

| 1993 | 1973 |

| 1994 | 1927 |

| 1995 | 1871 |

| 1996 | 1810 |

| 1997 | 1824 |

| 1998 | 1861 |

| 1999 | 1829 |

| 2000 | 1781 |

| 2001 | 1750 |

| 2002 | 1684 |

| 2003 | 1622 |

| 2004 | 1521 |

| 2005 | 1412 |

| 2006 | 1377 |

| 2007 | 1311 |

| 2008 | 1269 |

| 2009 | 1224 |

| 2010 | 1127 |

| 2011 | 995 |

| 2012 | 940 |

| 2013 | 842 |

| 2014 | 812 |

| 2015 | 793 |

| 2016 | 778 |

| 2017 | 723 |

| 2018 | 674 |

| 2019 | 648 |

| 2020 | 719 |

| 2021 | 690 |

| 2022 | 667 |

| 2023 | 647 |

| 2024 | 626 |

| 2025 | 606 |

| 2026 | 597 |

| 2027 | 589 |

| 2028 | 585 |

| 2029 | 578 |

| 2030 | 574 |

1.7. In an increasingly contested world, the stability and international collective effort that is needed for progress and prosperity is harder to achieve.[footnote 8] Geopolitical contestation is at its most intense since the end of the Cold War.[footnote 9] New geopolitical fault lines in the Indo-Pacific threaten to impact the region’s potential as the world’s growing economic centre of gravity. Nearly three-quarters (72%) of the world’s population now live in countries with an autocratic regime, with the average level of democracy down to 1986 levels.[footnote 10] The rise of autocratic governments threatens values of open and inclusive societies world-wide. Greater convergence and co-operation between powerful authoritarian states is fundamentally challenging the current international order.

Figure 2: Share of world population living in autocratising countries

Source: Papada, E., et al., University of Gothenburg Varieties of Democracy Institute. ‘Defiance in the Face of Autocratization’, Democracy Report 2023.

Figure 2 description

- 2012: 5%

- 2022: 43%

1.8. Transnational threats have expanded significantly, taking advantage of geopolitical, economic and technological shifts. They radically impact the challenges we face, acting as barriers to success. These overlapping threats include terrorism, violent extremism, cyber-crime, serious and organised crime, illicit finance, kleptocracy and state threats.

1.9. High and rising debt vulnerability poses a significant development challenge. This is the case for many low- and middle-income countries, including those that are affected by conflict and fragility. Contributing factors include slow gross domestic product (GDP) growth increasing the pressure on fiscal deficits, low revenue collection, public investments that do not generate sufficient return, and insufficient foreign exchange to repay loans in foreign currency due to lack of export earnings. Nearly sixty per cent of low-income countries are already in, or at high risk of, debt distress.[footnote 11] Restructuring debt has become more difficult as the range of creditors, institutions and instruments involved in sovereign finance has expanded.

1.10. Demographic trends will add to the pressure on many developing countries. Most of the world’s population growth will come from Sub-Saharan Africa and some countries of Western Asia.[footnote 12] In many of these countries, women are still not free to decide whether to have children, and if so, when. The population of sub-Saharan Africa could more than double to 2.8 billion between 2000 and 2060.[footnote 13] Rapid population growth increases the challenges of providing sufficient services, jobs and opportunity, tackling and adapting to climate change, and maintaining stable and open societies. By 2030, universal education across sub-Saharan Africa will require an estimated 4.3 million additional primary teachers and 10.8 million additional secondary teachers.[footnote 14]

Figure 3: Extreme poverty by region

Source: World Bank PIP data, forecast from FCDO poverty model.

Figure 3 description

| Region | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 379.24 | 382.48 | 387.11 | 388.10 | 377.75 | 375.05 | 373.56 | 372.61 | 371.36 | 376.59 | 370.39 | 370.76 | 369.87 | 369.62 | 369.05 | 380.28 | 386.49 | 389.38 | 391.08 | 397.03 | 390 | 393 | 394 | 395 | 396 | 396 | 397 | 397 | 396 | 395 | 394 |

| Europe and Central Asia | 76.79 | 70.84 | 63.18 | 62.47 | 54.83 | 54.12 | 48.16 | 43.06 | 38.82 | 37.21 | 36.46 | 33.87 | 32.21 | 29.67 | 30.72 | 28.15 | 24.63 | 24.73 | 21.13 | 20.27 | 31 | 27 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 25 |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 70.37 | 69.79 | 66.46 | 65.70 | 60.49 | 57.90 | 47.89 | 46.17 | 43.23 | 41.37 | 37.69 | 35.73 | 30.71 | 27.39 | 26.45 | 26.10 | 27.62 | 27.89 | 27.50 | 27.75 | 26 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 9 |

| Middle East and North Africa | 11.24 | 11.47 | 11.18 | 10.89 | 10.06 | 9.57 | 9.43 | 9.28 | 9.13 | 8.95 | 7.16 | 8.53 | 8.70 | 10.15 | 11.65 | 23.79 | 26.94 | 36.55 | 44.65 | 22.74 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 15 |

| South Asia | 571.69 | 577.55 | 581.90 | 574.89 | 557.78 | 537.90 | 524.57 | 503.86 | 488.65 | 477.83 | 431.74 | 360.57 | 334.91 | 327.29 | 313.97 | 294.74 | 283.94 | 232.82 | 191.42 | 195.47 | 193 | 162 | 141 | 120 | 99 | 77 | 55 | 35 | 16 | 2 | 2 |

| East Asia and Pacific | 809.02 | 768.75 | 691.88 | 628.08 | 554.56 | 460.62 | 451.17 | 406.86 | 383.66 | 342.45 | 293.96 | 231.50 | 197.45 | 101.76 | 82.02 | 61.95 | 53.15 | 44.22 | 37.46 | 28.25 | 25 | 22 | 16 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| World | 1800.29 | 1762.06 | 1696.89 | 1635.70 | 1533.61 | 1421.94 | 1386.74 | 1316.70 | 1278.72 | 1232.57 | 1136.12 | 1001.67 | 942.68 | 845.88 | 819.61 | 799.77 | 786.68 | 742.67 | 697.22 | 696.84 | 687 | 637 | 609 | 581 | 557 | 534 | 511 | 489 | 469 | 454 | 452 |

| World population | 6,062 | 6,144 | 6,226 | 6,308 | 6,389 | 6,471 | 6,553 | 6,635 | 6,718 | 6,802 | 6,886 | 6,970 | 7,054 | 7,141 | 7,230 | 7,318 | 7,405 | 7,492 | 7,578 | 7,662 | 7,743 | 7874.966 | 7953.953 | 8031.8 | 8108.605 | 8184.437 | 8259.277 | 8333.078 | 8405.863 | 8477.661 | 8548.487 |

1.11. The negative impacts of climate change will intensify as temperatures rise. Between 2000 and 2020, almost 7,500 extreme weather events were recorded, claiming 1.23 million lives, affecting 4.2 billion people and causing $2.97 trillion in economic losses.[footnote 15] Storms, drought, floods, heat stress, wildfires, glacial melt and rising sea levels will increase, with the impacts felt in all aspects of our lives, from health, to conflicts or migration. Small Island Developing States (SIDS), Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Fragile and Conflict Affected States (FCAS), especially in East Africa and across the Sahel, are disproportionately impacted.

Figure 4: The effects of climate change

Source: UK MET Office.

Figure 4 description

Figure 4 is an infographic setting out the drivers and effects of climate change. It has 3 circles:

The middle circle illustrates the drivers of climate change. We know that greenhouse gases, aerosol emissions and land use affect our climate. Overall, human activity is warming our planet.

The next circle includes how climate change affects the climate system. It includes 9 changes. These are:

- changes in the hydrological cycle

- warmer land and air

- warming oceans

- melting sea ice and glaciers

- rising sea levels

- ocean acidification

- global greening

- changes in ocean currents

- more extreme weather

The outer circle describes the impacts of climate change. It includes 13 impacts:

- risk to water supplies

- conflict and climate migrants

- localised flooding

- flooding of coastal regions

- damage to marine ecosystems

- fisheries failing

- loss of biodiversity

- change in seasonality

- heat stress

- habitable region of pests expands

- forest mortality and increased risk of fires

- damage to infrastructure

- food insecurity

1.12. Degradation of nature and biodiversity is taking place on a vast scale and at rapid pace. Pollution, damage to ecosystems and nature loss reduce the resilience of people and economies, as well as our ability to tackle and adapt to climate change. Three-quarters of the world’s land surface and 66% of the ocean have been significantly altered and degraded by human activity.[footnote 16] An estimated one million species are threatened with extinction. These changes have particularly severe consequences for people dependent on forests, fishing or farming for their livelihoods. Six of the 9 planetary boundaries, critical for maintaining the stability and resilience of the world’s climate and nature systems, are being crossed.[footnote 17]

1.13. Increasingly severe and frequent weather extremes will add to humanitarian need. Food insecurity linked to extreme heatwaves affected 98 million more people in 2020 than it did annually between 1981 and 2010.[footnote 18] Temperature increases from climate change will cause significantly higher GDP losses in developing countries.[footnote 19] Without action, an extra 100 million people will be at risk of being pushed into extreme poverty by 2030, and 720 million by 2050.

1.14. Forced displacement and migration are growing. By the end of 2022 there were almost 110 million forcibly displaced people (refugees and internally displaced and stateless people). Conflict, climate change and lack of economic opportunities are causing rising migration. In 2022 alone, 23.7 million new displacements occurred. Slow-onset climate change impacts could force as many as 216 million people to move within their own countries by 2050.[footnote 20] Illegal migration puts a strain on communities and increases the fiscal burden on transit and destination states. If they undertake illegal migration, migrants risk falling prey to unscrupulous criminals who lure them into undertaking perilous journeys, including to the UK.

Figure 5: Numbers of people in need of humanitarian assistance

Source: 1. Global Humanitarian Outlook, OCHA. Methodological changes to PiN production in 2020, 2021 and 2022 means care should be taken when comparing year on year change. 2. Global Humanitarian Assistance report 2023, Development Initiatives.

Figure 5 description

Graphic covers humanitarian need summary statistics:

- 363 million are estimated to need humanitarian assistance in 2023

- humanitarian needs are increasing year-on-year, ‘people in need’ (PiN) estimates have more than doubled over the last 5 years

- 4 in 5 people in need live in a country experiencing a protracted crisis in 2022

| Year | People in need (million) |

|---|---|

| 2018 | 156 |

| 2019 | 167 |

| 2020 | 249 |

| 2021 | 250 |

| 2022 | 326 |

| 2023 | 363 |

There is a chart that presents ‘people in need of humanitarian assistance’ figures from 2018 to 2023 which shows the growth year-on-year. The data source is given as OCHA year-end estimates (2018 to 2022) and as of 31 August 2023. There is a footnote to the chart stating that COVID-specific appeals in 2020 are not included.

1.15. Challenges to international norms and values are increasing. The UN charter has as its core the importance of sovereignty, territorial integrity, political independence for nations, and universal human rights for all individuals. Challenges include lack of accountability for violations of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) and International Human Rights Law. Parties to conflict are increasingly disregarding norms and rules designed to protect civilians in conflict and prevent mass atrocities, constraining populations’ access to humanitarian aid and increasing the severity of need. Formal mechanisms to promote compliance with IHL are showing their limitations.

1.16. Progress on human rights is at risk. International norms on rights are being eroded. This is particularly pronounced for women and girls, on their sexual and reproductive health and rights, for LGBT communities, and religious or belief minorities.

1.17. New technologies present both opportunities and challenges. Emerging technologies have the potential to unlock progress against all SDGs. Breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI) and advances in engineering biology, batteries and renewables are likely to support greener growth paths.[footnote 21] However, there is a widening digital divide between the richest and poorest countries and communities within them. New technology and cyber‑attacks are playing an increasing role in modern warfare and insecurity. The spread of false narratives and mis- and dis-information have contributed to the erosion of trust in institutions, including the media. There are trade-offs between innovation and security. There are also challenges with supply chains for renewable technologies. The technological nationalism is intensifying.

Transformational progress that can be built upon

1.18. Current challenges follow decades of tremendous progress. Hundreds of millions of people have been lifted out of extreme poverty since the middle of the 20th century.[footnote 22] Countries have grown their economies and resilience. There have been huge gains in health and access to education, though progress is now stalling. While some regions of the world are stagnating or falling behind, most are richer than ever before.

1.19. The UN Millennium Development Goals, agreed in 2000 to be achieved by 2015, brought rapid change. The goal to halve the number of people in extreme poverty was met ahead of schedule. Life expectancy improved from 50 to 65 in low-income countries. Health outcomes and education access improved worldwide. New human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections declined rapidly. Child mortality, malnutrition and stunting dropped. In LDCs, one-in-5 children were dying before their fifth birthday in 1990, and this reduced to almost one-in-twenty-six.[footnote 23]

Figure 6: Global change in development indicators: the world as 100 people

Source: FCDO, based on 'The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it – Our World in Data' (Creative Commons by licence).

Figure 6 description

| Year | % in poverty: extreme poverty | % in poverty: not in extreme poverty | % living in democracies: autocracy | % living in democracies: democracy | % that are literate: illiterate | % that are literate: literate | % that are vaccinated: vaccinated | % that are vaccinated: not vaccinated | Child mortality rates: survive to 5 | Child mortality rates: doesn’t survive to 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 48 | 52 | 65 | 35 | 58 | 42 | no data | no data | 80 | 20 |

| 1961 | 47 | 53 | 65 | 35 | 57 | 43 | no data | no data | 81 | 19 |

| 1962 | 46 | 54 | 65 | 35 | 56 | 44 | no data | no data | 83 | 17 |

| 1963 | 45 | 55 | 65 | 35 | 54 | 46 | no data | no data | 84 | 16 |

| 1964 | 46 | 54 | 65 | 35 | 53 | 47 | no data | no data | 84 | 16 |

| 1965 | 47 | 53 | 65 | 35 | 51 | 49 | no data | no data | 85 | 15 |

| 1966 | 46 | 54 | 65 | 35 | 50 | 50 | no data | no data | 85 | 15 |

| 1967 | 45 | 55 | 65 | 35 | 49 | 51 | no data | no data | 85 | 15 |

| 1968 | 46 | 54 | 65 | 35 | 47 | 53 | no data | no data | 85 | 15 |

| 1969 | 45 | 55 | 65 | 35 | 46 | 54 | no data | no data | 85 | 15 |

| 1970 | 45 | 55 | 65 | 35 | 44 | 56 | no data | no data | 86 | 14 |

| 1971 | 44 | 56 | 66 | 34 | 44 | 56 | no data | no data | 86 | 14 |

| 1972 | 44 | 56 | 65 | 35 | 44 | 56 | no data | no data | 86 | 14 |

| 1973 | 43 | 57 | 66 | 34 | 44 | 56 | no data | no data | 87 | 14 |

| 1974 | 42 | 58 | 65 | 35 | 44 | 56 | no data | no data | 87 | 13 |

| 1975 | 42 | 58 | 81 | 19 | 44 | 56 | no data | no data | 87 | 13 |

| 1976 | 40 | 60 | 81 | 19 | 44 | 56 | no data | no data | 87 | 13 |

| 1977 | 39 | 61 | 66 | 34 | 44 | 56 | no data0 | no data | 87 | 13 |

| 1978 | 38 | 62 | 65 | 35 | 44 | 56 | no data | no data | 88 | 12 |

| 1979 | 36 | 64 | 65 | 35 | 44 | 56 | no data | no data | 88 | 12 |

| 1980 | 34 | 66 | 66 | 34 | 44 | 56 | 20 | 80 | 88 | 12 |

| 1981 | 35 | 65 | 66 | 34 | 43 | 57 | 23 | 77 | 89 | 11 |

| 1982 | 36 | 64 | 66 | 34 | 42 | 58 | 25 | 75 | 89 | 11 |

| 1983 | 36 | 64 | 66 | 34 | 40 | 60 | 37 | 63 | 89 | 11 |

| 1984 | 34 | 66 | 66 | 34 | 39 | 61 | 44 | 56 | 90 | 11 |

| 1985 | 33 | 67 | 66 | 34 | 38 | 62 | 48 | 52 | 90 | 10 |

| 1986 | 33 | 67 | 66 | 34 | 37 | 63 | 51 | 49 | 90 | 10 |

| 1987 | 34 | 66 | 63 | 37 | 35 | 65 | 55 | 45 | 90 | 10 |

| 1988 | 35 | 65 | 61 | 39 | 34 | 66 | 63 | 37 | 90 | 10 |

| 1989 | 34 | 66 | 61 | 39 | 33 | 67 | 68 | 32 | 91 | 10 |

| 1990 | 31 | 69 | 58 | 42 | 32 | 68 | 76 | 24 | 91 | 9 |

| 1991 | 33 | 67 | 57 | 43 | 30 | 70 | 71 | 29 | 91 | 9 |

| 1992 | 34 | 66 | 52 | 48 | 29 | 71 | 69 | 31 | 91 | 9 |

| 1993 | 35 | 65 | 54 | 46 | 28 | 72 | 70 | 30 | 91 | 9 |

| 1994 | 36 | 64 | 54 | 46 | 27 | 73 | 72 | 28 | 91 | 9 |

| 1995 | 36 | 64 | 52 | 48 | 25 | 75 | 73 | 27 | 91 | 9 |

| 1996 | 32 | 68 | 50 | 50 | 24 | 76 | 72 | 28 | 91 | 9 |

| 1997 | 29 | 71 | 50 | 50 | 23 | 77 | 71 | 29 | 92 | 8 |

| 1998 | 32 | 68 | 50 | 50 | 22 | 78 | 71 | 29 | 92 | 8 |

| 1999 | 28 | 72 | 46 | 54 | 20 | 80 | 71 | 29 | 92 | 8 |

| 2000 | 25 | 75 | 47 | 53 | 19 | 81 | 72 | 28 | 92 | 8 |

| 2001 | 23 | 77 | 46 | 54 | 19 | 81 | 73 | 27 | 93 | 7 |

| 2002 | 22 | 78 | 48 | 52 | 19 | 81 | 72 | 28 | 93 | 7 |

| 2003 | 22 | 78 | 48 | 52 | 19 | 81 | 74 | 26 | 93 | 7 |

| 2004 | 22 | 78 | 49 | 51 | 18 | 82 | 76 | 24 | 93 | 7 |

| 2005 | 20 | 80 | 50 | 50 | 18 | 82 | 77 | 23 | 94 | 6 |

| 2006 | 19 | 81 | 50 | 50 | 18 | 82 | 78 | 22 | 94 | 6 |

| 2007 | 18 | 82 | 50 | 50 | 18 | 82 | 78 | 22 | 94 | 6 |

| 2008 | 18 | 82 | 50 | 50 | 18 | 82 | 81 | 19 | 94 | 6 |

| 2009 | 17 | 83 | 51 | 49 | 18 | 82 | 83 | 17 | 95 | 5 |

| 2010 | 17 | 83 | 50 | 50 | 17 | 83 | 83 | 17 | 95 | 5 |

| 2011 | 16 | 84 | 50 | 50 | 17 | 83 | 84 | 16 | 95 | 5 |

| 2012 | 16 | 84 | 47 | 53 | 17 | 83 | 84 | 16 | 95 | 5 |

| 2013 | 14 | 86 | 49 | 51 | 16 | 84 | 84 | 16 | 95 | 5 |

| 2014 | 12 | 88 | 47 | 53 | 16 | 84 | 85 | 15 | 96 | 4 |

| 2015 | 12 | 88 | 48 | 52 | 15 | 85 | 85 | 15 | 96 | 4 |

| 2016 | 11 | 89 | 47 | 53 | 15 | 85 | 86 | 14 | 96 | 4 |

| 2017 | 11 | 89 | 66 | 34 | 14 | 86 | 86 | 14 | 96 | 4 |

| 2018 | 10 | 90 | 68 | 32 | 14 | 86 | 86 | 14 | 96 | 4 |

| 2019 | 10 | 90 | 68 | 32 | 14 | 86 | 86 | 14 | 96 | 4 |

| 2020 | 10 | 90 | 68 | 32 | 13 | 87 | 83 | 17 | 96 | 4 |

1.20. SDGs will remain out of reach by 2030, or even 2050, if there is no improvement in current trends. Poverty rates globally have returned to pre-pandemic levels, but progress is uneven, with extreme poverty concentrated in low-income countries and countries impacted by conflict.[footnote 24] Climate change could push another 130 million into poverty, unless climate action is accelerated.[footnote 25]

Figure 7: The Sustainable Development Goals

Figure 7 description

| Number | Goal |

|---|---|

| SDG 1 | No poverty |

| SDG 2 | Zero hunger |

| SDG 3 | Good health and wellbeing |

| SDG 4 | Quality education |

| SDG 5 | Gender equality |

| SDG 6 | Clean water and sanitation |

| SDG 7 | Affordable clean energy |

| SDG 8 | Decent work and economic growth |

| SDG 9 | Industry, innovation and infrastructure |

| SDG 10 | Reduced inequalities |

| SDG 11 | Sustainable cities and communities |

| SDG 12 | Responsible consumption and production |

| SDG 13 | Climate action |

| SDG 14 | Life below water |

| SDG 15 | Life on land |

| SDG 16 | Peace, justice and strong institutions |

| SDG 17 | Partnerships for the goals |

Figure 8: The proportion of Sustainable Development Goals which are off-track

Source: UN Sustainable Development Goals Report 2023.

Figure 8 description

SDG progress by percentage of indicators:

| Progress | Percentage of SDGs |

|---|---|

| On track | 15% |

| Moderately or severely off track | 48% |

| Stagnation or regression | 37% |

A vision and invitation to action to achieve the Agenda 2030 and the SDGs

1.21. The scale and breadth of these challenges require a comprehensive and ambitious global invitation to action to deliver the SDGs by 2030. Every country has its part to play.

1.22. The UK will partner with others to accelerate progress across the broad SDGs agenda: going further, faster in mobilising finance; international system reform; championing prevention and anticipatory action; building resilience and enabling adaptation; standing for our values; and harnessing innovation. Success will help countries to achieve self-reliance and will lead to a safer, more prosperous and more secure world for everyone.

1.23. Our future approach must be different from the past, reflecting the global challenges and opportunities ahead. The global transition to net zero will result in the largest flow of capital ever seen into clean technologies and green industries, and provide opportunities to revitalise economies, improve health outcomes and catalyse sustainable development. It is in everyone’s interests to ensure low- and middle-income countries secure their share of the benefits.

1.24. The financing gap to meet the SDGs, end poverty and chart a sustainable growth pathway is enormous. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) estimates that $3.9 trillion more annually is needed to achieve the SDGs by 2030.[footnote 26] An analysis by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states that trillions of US dollars per year of climate finance will be needed by 2030 to meet the mitigation and adaptation needs of low- and middle-income countries.[footnote 27] This requires rethinking and rewiring how governments, multilaterals and the private sector support global development.

1.25. Shifting power and alliances are a feature of the geopolitical context in which countries are choosing how they will achieve their development goals. International and multilateral settings are changing and membership of groups such as BRICS and Shanghai Co-operation Organisation[footnote 28] are evolving. The UK will use its role in the G7 and the G20 to demonstrate we are responding to our partners’ concerns. Greater co-operation can help the benefits of global development to be more widely felt, through increased global action and resources focused on the development, climate and nature objectives most important to our partners.

1.26. Low- and middle-income countries rightly demand that we respect and respond to their priorities for development. This means forming relationships fit for the 21st century that are not defined by aid, and working with countries on systemic global and regional solutions that meet their domestic development priorities. It means global development that is led by the countries, societies, and communities that are most affected. The UK recognises it has much to learn, as well as much to offer. The UK commits to listening to those closest to the challenges faced by communities and harnessing our economic and political capability to drive positive change together.

1.27. A bigger, better and fairer international system is needed, serving all those that need it. The countries and people that have historically been excluded from power must have a central voice in how the international order changes. The UK’s historic role in the international system means we have a responsibility to help ensure it is more representative, and that we make space for the people and countries who are closest to the development and climate challenges we share. This also means working with others to strengthen the effectiveness of multilateral institutions where low- and middle-income countries have greater voice. Ambitious agendas for reform of the international financial system are emerging from countries historically less well represented, but who most need it to change.

1.28. A clear strategic goal will sit at the centre of UK action. UK international development will work to end extreme poverty and tackle climate change and biodiversity loss. Meeting this goal will help countries to achieve the sustainable economic growth they need for self-reliance and will support progress across all the SDGs. This will protect our interest in an open and stable international order, and the UK’s core national interests, the sovereignty, security and prosperity of the British people.

1.29. Delivering this mission requires action across 6 core areas to end extreme poverty and tackle climate change and biodiversity loss:

-

mobilising the money to finance development (Chapter 3)

-

international system reform to unlock progress (Chapter 4)

-

tackling climate change and biodiversity loss and enabling economic transformation (Chapter 5)

-

ensuring opportunities for all, including through equality and rights, education health, water and social protection (Chapter 6)

-

tackling conflict and state fragility, disasters and food insecurity, including anticipatory action and building resilience (Chapter 7)

-

harnessing innovation to overcome barriers to development (Chapter 8)

1.30. The UK’s full capability for development will be involved (Chapter 9). We will take a whole-of-government approach. We will also work with UK businesses, civil society, the private sector and the City of London, universities and research centres.

1.31. Our generation can still be the first to end extreme poverty. Our generation is the last who can tackle the worst effects of climate change and nature loss. Collectively, we have the resources, the technology and the knowhow to ensure planetary limits are not breached, and to meet people’s economic, social, and development needs. This requires working together on a development agenda fit for the challenges we now face.

Chapter 2: UK international development and our approach

The role of the UK

2.1. The British people can be proud of their part in achieving development progress. The UK has been at the centre of an international effort to champion poverty reduction, increase trade, respond to humanitarian crises and conflict, build global health and education systems, support multilateralism, and sustain peace and security in some of the world’s most challenging environments. This is the right thing to do, and the smart thing to do to advance UK interests.

2.2. Results demonstrate the UK’s track record. Since 2015, the UK has supported nearly 20 million children, including 10 million girls, to gain a decent education.[footnote 29] Since 2011, the UK has supported more than 101 million people with managing the effects of climate change, improved the climate resilience of more than 32 million people, and reduced or avoided more than 86 million tonnes of greenhouse gases.[footnote 30]

2.3. The UK is proud to have played a strong role with others to shape the SDGs. We remain committed to leaving no-one behind, a core principle of Agenda 2030, and to accelerating progress on the SDGs in the UK and internationally.

2.4. The UK has convened partners to secure many global development commitments, working in partnership for the SDGs (SDG 17). These include the Global Education Summit (2021), the Global Vaccine Summit (2011 and 2021), launching the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) during our G7 Presidency (2021). For COP26 (2021), the UK led on the Glasgow Climate Pact, which agreed the importance of limiting global average temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. We also played a leading role in the historic Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (COP 15, 2022) being agreed, to halt and reverse the destruction of nature.

2.5. The generosity of the British people is demonstrated worldwide. When crises hit, the UK public and government respond together. The UK government has provided match funding for approximately £200 million of public donations for life-changing development projects and in response to humanitarian crises since 2016.[footnote 31] Our civil society is one of the most experienced and active globally, connecting with partners and communities to improve development outcomes.

2.6. The UK government will take a whole-of-government approach to deliver our strategic vision for international development to 2030 to end extreme poverty, tackle climate change and biodiversity loss, and accelerate sustainable economic growth to enable countries to achieve self-reliance. The creation of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) joins together the UK’s development expertise and its global diplomatic network, increasing our scope for development impact. The UK will bring a broad spectrum of capabilities and policy levers to our partnerships, including mobilising investment, fostering trade, technical expertise, technology, science and diplomacy, and working in partnership with host governments and citizens in order to achieve long-term reform and change.

2.7. UK International Development (or UKDev) was launched as the new brand for UK development in 2023 to signal the UK’s commitment to progress and represent the totality of UK development effort. UKDev will deliver the commitments outlined in this white paper, always emphasising results and transparency. FCDO will bring together all of government, ensuring coherence, working to support other departments where they lead on policy, and making full use of the UK’s global diplomatic network.

2.8. The areas of focus in this white paper were developed based on an open dialogue. We consulted partners in the UK and around the world in 70 countries, primarily low- and middle-income countries, in multilateral and bilateral organisations, with the private sector and civil society, development practitioners and researchers. We received 464 responses from 46 countries to our public call for evidence.

2.9. We listened to what everyone involved in the consultation process told us. This is what we heard:

-

the UK has the most positive impact when it is focused on transformative, long-term, systemic change. We should return to a long-term, predictable focus for policy and funding, built on locally-led development

-

the UK’s aid generosity and focus on need is valued and seen to support strong development partnerships

-

the UK is recognised for its expertise and technical assistance, and for its enduring role in the multilateral system

-

the UK’s convening power is valued and could be used more for today’s development challenges, from food security to AI in development

-

the UK can do more to create genuine, equitable, strategic and long-term partnerships, working on shared priorities and based on a strong understanding of the context

-

the UK has both a responsibility to acknowledge its role in the international system, and an opportunity to make the system fairer and more equal

2.10. We will build on UK strengths and shift our approach to partnerships, prioritising mutual respect.We will take a long-term approach. We will be more locally-led. We will bring the best of what the UK has to offer, including the breadth and depth of our global network, and support partners where they can lead. We will champion more open and inclusive approaches to international development.

Case study 1: The strategic partnership with Indonesia

The UK-Indonesia Roadmap enshrined our strategic partnership, based on mutual respect and focused on supporting Indonesia’s green growth and human development. Our long‑term engagement with Indonesia puts patient diplomacy and development in action. Our partnership bring together all our capabilities, including our diplomacy, research, trade, and investment.

Indonesia’s development and actions matter globally. Its size and influence mean it is an important enabler for progress made against Sustainable Development Goals, both in its region and globally, and especially for supporting co-operation between low- and middle-income countries. Indonesia has seen significant progress on poverty reduction, human development and the environment over the last 2 decades. Indonesia’s economic pathway from here on will have significance to achieve a global warming cap of 1.5 degrees Celsius and for global biodiversity.

Indonesia is grappling with the sometimes conflicting goals of supporting economic growth and reducing emissions. Home to the largest reserves of nickel in the world, Indonesia has difficult political choices to be made about powering the electric vehicle industry, given the abundance of cheap coal. The UK offers innovative financing instruments, expertise, and convening power to work alongside Indonesia on its development journey, while tackling a shared global crisis. Through our flagship Mentari programme on energy transition, the UK has deployed expertise, diplomatic influence, and an innovative $1 billion guarantee to help create the conditions for a Just Energy Transition Partnership agreement that will mobilise $20 billion of public and private finance for an accelerated green transition.

Jolinda, a young woman from Sumba in Indonesia, has helped to install and operate a new solar plant as part of the UK’s Mentari programme, which has worked with the Indonesian government to provide electricity to rural and previously unconnected parts of the country. Photo credit: FCDO.

Principles for partnerships

Mutual respect

2.11. UK development partnerships will be guided by the principle of mutual respect. A focus on mutual respect will put patient diplomacy and development into practice. It will build long-term reliable and equitable partnerships that work towards common development objectives. It will move us beyond an outdated ‘donor-recipient’ model. We will engage with humility and acknowledge our past.

2.12. Mutual respect encompasses:

-

ownership: our partners, whether countries, organisations, or people, own and lead their development

-

mutuality: we are mutually accountable for delivering on our respective roles. We learn together and improve how we deliver together

-

transparency: transparency on all sides is critical to development progress. We will provide the transparency our partners need, including by publishing Country Development Partnership Summaries[footnote 32]

-

values: we are open about UK values and will stand up for them. While we respect that not all our partners will share these values, we will seek and focus on common ground

Values we will champion

2.13. The UK defends and promotes human rights, the rule of law and accountable institutions. We will work with our partners to ensure that a reinvigorated multilateral system will effectively uphold global human rights norms. More than 90% of SDG goals[footnote 33] and targets correspond to human rights: rights are essential to achieving sustainable development. We will set out the benefits of open societies with confidence, while accepting that our values, national interests and paths to change may differ from other countries.

2.14. Leaving no-one behind remains a guiding value of UK international development.[footnote 34] This principle also underpins delivery of the SDGs. The UK will prioritise the most vulnerable communities, and those at the frontline of the worst effects of climate change and biodiversity loss when providing grant financing, working in partnership with these communities as agents for change.

2.15. Unlocking the full potential and power of women and girls accelerates progress on all global development priorities. The UK has been a long-term champion of the rights of women and girls around the world, through our development, diplomatic and legislative efforts, including the International Development (Gender Equality) Act 2014.

2.16. The UK is committed to concerted action to tackle sexual exploitation and abuse and harassment (SEAH). Hundreds of cases are reported every year. Many more go unreported. The UK supports the development of a new global ‘Common Approach to Protection against SEAH’,[footnote 35] to accelerate progress, improve coherence and momentum, and protect the most vulnerable.[footnote 36]

Case study 2: Safeguarding

Sexual exploitation and abuse and sexual harassment (SEAH) causes physical, emotional and economic harm. It also undermines delivery of, and trust in, humanitarian, development and peacekeeping work. Without co-ordinated action, perpetrators can move undetected between organisations and countries, and it is much harder to support survivors and victims. In 2018, the UK government hosted a global summit to amplify the voices of survivors, victims and whistle-blowers and seek a more co-ordinated approach: development partners, multilateral organisations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), contractors and others made commitments.[footnote 37] The UK has reported annually on progress[footnote 38] and funded work to identify perpetrators, support survivors and victims, and build the confidence and capability of individuals and organisations involved in or impacted by development work to protect against SEAH. As a result, tens of thousands of staff and volunteers have received safeguarding training and undergone more stringent background checks, and more survivors and victims of SEAH have been assisted. Hundreds of cases are still reported every year, and many go unreported. That is why, since 2022, we have been supporting the development of a new global ‘Common Approach to Protection against SEAH’ which should be agreed in 2024 and includes an even wider group of stakeholders.

The UK is funding work in Malawi through Social Development Direct to help women’s rights organisations and local authorities to improve the support provided to survivors and victims of sexual exploitation and abuse and sexual harassment. Photo credit: Social Development Direct.

Localisation and locally-led development

2.17. We will work towards a more inclusive and more locally-led approach. Where countries have their own clear vision, approach and narrative, about their development and progress, this increases the likelihood of development success. It is right for development to be increasingly designed and delivered by local people and organisations, especially typically marginalised groups, including women and girls, indigenous people and local communities. UK policy advice, technical knowledge, and funding will be more sustainable, when we partner with those who best understand local needs and realities, and when they determine their own development.

2.18. We will publish a strategy setting out how the UK will support local leadership on development, climate, nature and humanitarian action. The strategy will explore how our engagement, terminology, delivery, and approach to risk can change to support local partnerships. We will learn from current evidence on how best to engage local leaders and social groups in decision-making. We will invest in research to better understand and support local leadership.

Case study 3: Locally-led development in Myanmar

In Myanmar, the UK works with inspirational local organisations that find ways to support the emergency needs of families forced to flee their homes due to conflict. Two and a half years after the 2021 military coup, Myanmar is riven by violence. More than 2 million people have fled their homes, and the number in desperate need of aid has skyrocketed from 1 million before the coup to 18 million today. UK support, mostly provided through local partners, helps to meet the emergency needs of around 600,000 people affected by the conflict, despite the military blocking formal access by the United Nations and International non-governmental organisations (INGOs).

This work is built on the relationships we have developed with networks of local civil society partners. Partners do not just want funding; they want a stronger voice and empowered agency reflecting their unique understanding. We invest in strengthening the capacity of local organisations and networks; developing funding instruments designed for them; and building platforms to help local and international partners talk meaningfully. We make sure our financing is flexible enough to allow partners to respond adaptively. Through engagement with community networks, we constantly update our understanding of the shifting context, our partners, and risks.

Targeting development assistance

2.19. The UK government is committed to the International Development (Official Development Assistance Target) Act 2015 and to spending 0.7% of gross national income (GNI) on Official Development Assistance (ODA) once the fiscal situation allows. ODA is one of the largest sources of development finance to low-income countries and provides essential resources for activities that would otherwise have limited available funding, ranging from humanitarian support to tax reform.

2.20. Poverty reduction is the primary purpose of ODA programmes. This is required by existing domestic legislation and necessary to achieve our strategic development goal. The focus on poverty reduction is central to all parts of our development partnerships and activity and wholly in UK national interests.

2.21. We will prioritise ODA where it is most needed and most effective. That is why the UK will prioritise its grant resources to the lowest income countries and communities, which are often also vulnerable to the effects of conflict and climate change. We expect to spend less ODA in contexts where other sources of finance are available or other levers are more effective.

2.22. The UK will aim to spend at least 50% of all bilateral ODA in the LDCs. This focus on LDCs will inform all our ODA spending. In addition, the UK will support the global goal of providing at least 0.2% of our GNI to LDCs. The UN classification of LDCs includes income and human development measures as well as economic and environmental vulnerability. LDCs are the least able to finance their development through taxes, borrowing or investment. There is a strong overlap between LDCs, FCAS and countries vulnerable to climate change. The majority of the world’s poorest people live in LDCs that are either fragile, affected by conflict, or vulnerable to climate change.

2.23. We will deliver on our commitment to provide £11.6 billion in international climate finance between 2021 to 2022 and 2025 to 2026, ensuring a balance between adaptation and mitigation and including at least £3 billion to protect and restore nature. We will spend at least £1.5 billion of International Climate Finance on adaptation in 2025. We will prioritise support for countries tackling the impacts and causes of climate change and biodiversity loss, and ensure that all new bilateral ODA is aligned to the Paris Agreement and Global Biodiversity Framework, building on previous commitments.

2.24. We will ensure that the reasonable needs of ODA-eligible UK Overseas Territories (OTs) are met. The UK and Territory governments will work in partnership, especially where we can help to build local capacity to deliver devolved responsibilities. The UK will fulfil its moral and constitutional responsibilities for the OTs and be as ambitious for our OTs as we are for the UK.

2.25. Strategic coherence and prioritisation of the UK’s ODA is overseen by the UK government ODA board. The board provides strategic oversight of ODA spend, scrutinises the value of spending, and anticipates and manages new risks. The board is chaired by the Minister for Development and Africa and the Chief Secretary to the Treasury.

Deepening our development partnerships

2.26. We want to expand the reach and depth of our partnerships. This includes countries, regional groups, organisations and people active in global development co-operation. The UK and our partners both bring ideas, networks, knowledge, expertise in specific areas, and resources that can be combined for greater development impact.

2.27. Our partnerships will be adapted to the specific goals and needs of our partners. Partnerships will be informed by a shared understanding of the context, objectives, and evidence of what works. We will use different approaches and instruments to suit the context. This will include supporting the capabilities, institutions, policies and narratives needed for lasting progress. This will ensure the right resources are allocated where they are needed most.

2.28. As countries’ development trajectories evolve, whether they are experiencing progress or setbacks, so will our partnership offer. Climate vulnerability and biodiversity loss, fragility and conflict, will all cause setbacks and reversals and may require us to adapt our approach. In fragile and conflict affected states, we will work to reduce conflict and violence, and address the drivers and causes of crises.

2.29. We will draw on ODA only as necessary in our partnerships with middle-income countries (MICs). We recognise middle-income countries are a broad and variable group. MIC status masks pockets of extreme poverty and inequality, as well as acute humanitarian needs. ODA can be used in a targeted way to support their objectives and our shared priorities, so they can drive their own long-term development, and contribute to achieving global commitments, including supporting climate mitigation in MICs with the highest emissions growth.

2.30. To complement ODA spending we will work with our partners to bring together investment, trade, expertise, technology, science and diplomatic capability. This includes complementing conventional ODA programmes with commercial solutions, technical expertise and competitive export finance. Linking the UK’s growth agenda with positive outcomes for low- and middle-income countries can raise living standards, lock partners into positive growth trajectories and support economic security at home and abroad. In the long-term, this will help low- and middle-income countries become increasingly significant trade and investment partners of the future, mutually benefitting businesses and consumers, both in our partner countries and the UK.

2.31. Where country priorities run counter to our principles, values and commitment to the SDGs, we will follow humanitarian principles, and we will support those trying to bring about positive change. Wherever possible we will remain engaged even in the most challenging countries, to ensure that life-saving support reaches those paying the price for conflict and bad governance, and to stand up for human rights and the rule of law.

Working with global development partners

2.32. The UK is stepping up collaboration with a range of emerging development partners. The UK will work with these partners to identify opportunities to collaborate further and to share our respective learning and expertise. This includes consolidating and promoting partnerships with, for example, Turkey, Brazil, South Korea and India. This reflects our wider foreign policy commitment to invest in new relationships based on respect, solidarity, and a willingness to listen.

2.33. The UK will further deepen and expand our existing partnerships. This includes growing relationships with development partners in the Gulf; Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar and Kuwait. We share interests in supporting vulnerable regions affected by deep development challenges, instability and humanitarian crises across Africa, South Asia and the Middle East. Collaborative working across humanitarian and development objectives provides an opportunity to share our knowledge, scale our funding and co-financing, and strengthen cultural connections as well as global and local networks.