Interim overarching evaluation on the Know Your Neighbourhood Fund

Published 28 August 2025

Applies to England

Key Lessons

The Know Your Neighbourhood (KYN) Fund is an up to £30 million package of funding designed to widen participation in volunteering and tackle loneliness in 27 disadvantaged areas across England. This includes up to £10m of funding delivered by The National Lottery Community Fund.

This interim evaluation report draws on preliminary baseline survey data collected from beneficiaries and volunteers of funded projects from September 2023 to January 2024 and interviews with projects and KYN Fund stakeholders (all collected between March 2023 and July 2024). It sets out preliminary lessons learned, that are summarised below.

-

Increasing sustained volunteering and reducing chronic loneliness complement each other as target outcome areas when designing and delivering interventions.

-

Delivery partner support during the application stage was accessible to all KYN Fund applicants, but projects found support particularly easy to access when they had a pre-existing relationship with their delivery partner.

-

Longer set up and application phases could have helped Cultural Partners and Community Foundations (CFs) to extend their reach to a wider variety of projects. This is, however, constrained by the need of Government to align with annual business planning cycles.

-

Projects and partners valued and benefited from collaboration with each other as it gave them an opportunity to share learnings about delivery and the evaluation process. Further collaboration between KYN funded projects could help promote sustainable systems and processes that encourage volunteering and tackle loneliness.

This report analysed the survey data from the first wave of (baseline) questionnaires collected up to 29 January 2024 with responses from 1,853 respondents involved in UK Community Foundations (UKCF) funded projects to provide a snapshot of who the beneficiaries and volunteers are.[footnote 1][footnote 2] As many projects are recruiting on a rolling basis, baseline survey collection will continue until the Fund ends in March 2025. This allows the evaluation to consider the extent to which the UKCF funding is reaching its intended audience. The report found that:

-

Slightly more than half of respondents (56% of n=1,853) to the baseline survey up to January 2024 were volunteers. Of the volunteer respondents, half (51% of n=1,045) were new to volunteering, in line with KYN Fund objectives.

-

Baseline responses appear to suggest that projects were reaching people who more frequently experience loneliness, compared with the general population. 15% (of n=1,835) of respondents reported feeling lonely often or always, a response usually associated with chronic loneliness. This suggests a higher prevalence than in the general population (7% of n=170,255).[footnote 3] Furthermore, 45% (of n=1,835) of respondents reported feeling lonely either some of the time, often or always (compared to 26% of adults [n=170,255] who took part in the CLS 2023/24).[footnote 4]

For the remainder of the KYN Fund, this report recommends that CFs and Cultural Partners should ensure that they have facilitated introductions between their projects. Projects operating in the same area should have introductions facilitated, regardless of funder.

1. Executive Summary

1.1 Background to the Know Your Neighbourhood Fund

The KYN Fund is investing up to £30 million to widen participation in volunteering and tackle loneliness in 27 disadvantaged areas across England. The objectives of the KYN Fund are, by March 2025:

-

To increase the proportion of people in targeted high-deprivation local authorities who volunteer at least once a month.

-

To reduce the proportion of chronically lonely people in targeted high-deprivation local authorities who lack a desired level of social connections.

-

To build the evidence to identify scalable and sustainable place-based interventions that work in increasing regular volunteering and reducing chronic loneliness.

-

To enable targeted high-deprivation local authorities, and the local voluntary and community sector in these places, to implement sustainable systems and processes that encourage volunteering and tackling loneliness.

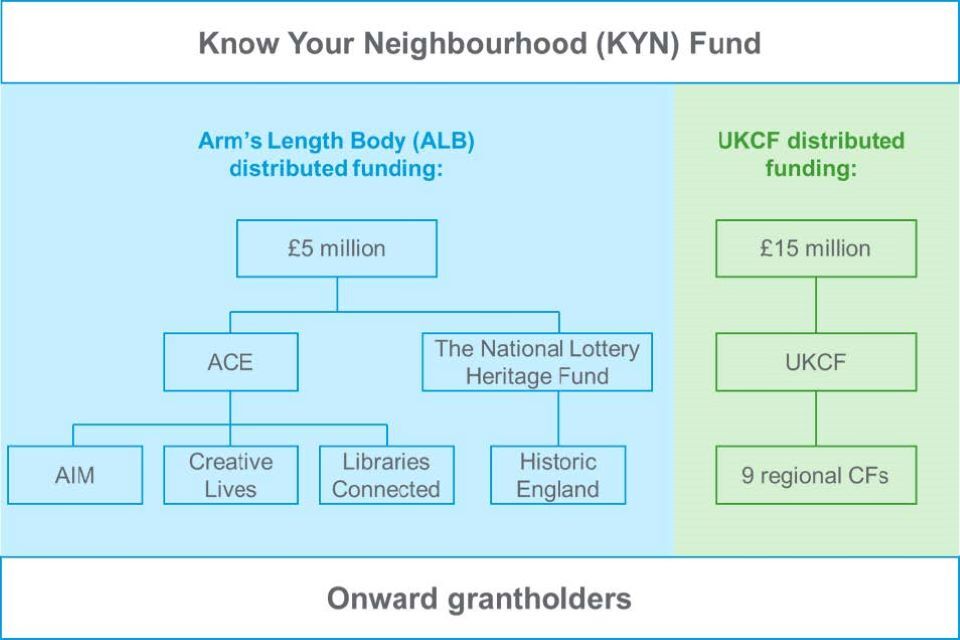

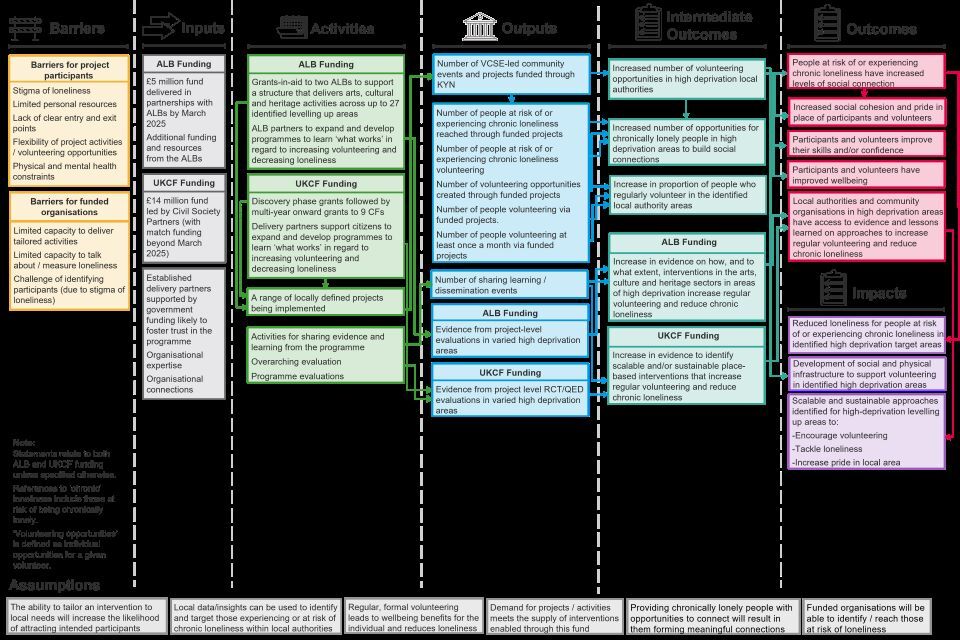

The KYN Fund is split into three funding streams. Its structure is shown in Figure 1 below:

-

£5 million of government funding is being invested in supporting people to participate in volunteering and connect with others through expanding the existing offer of arts, culture and heritage activities across the 27 KYN target areas. This funding is being delivered by Arts Council England (ACE) and The National Lottery Heritage Fund, in partnership with Historic England.

-

£15 million of the total £20 million government funding is being delivered by UKCF and a consortium of local CFs across 9 areas.

-

The National Lottery Community Fund is investing up to £10 million of their own funding to top up existing projects that support the KYN Fund objectives, working across the same 27 target areas.

Diagram showing how the KYN funding is split into three funding streams: Arm’s length body (ALB) distributed funding, UKCF distributed funding and The National Lottery Community Fund distributed funding.

1.2 Purpose of the evaluation

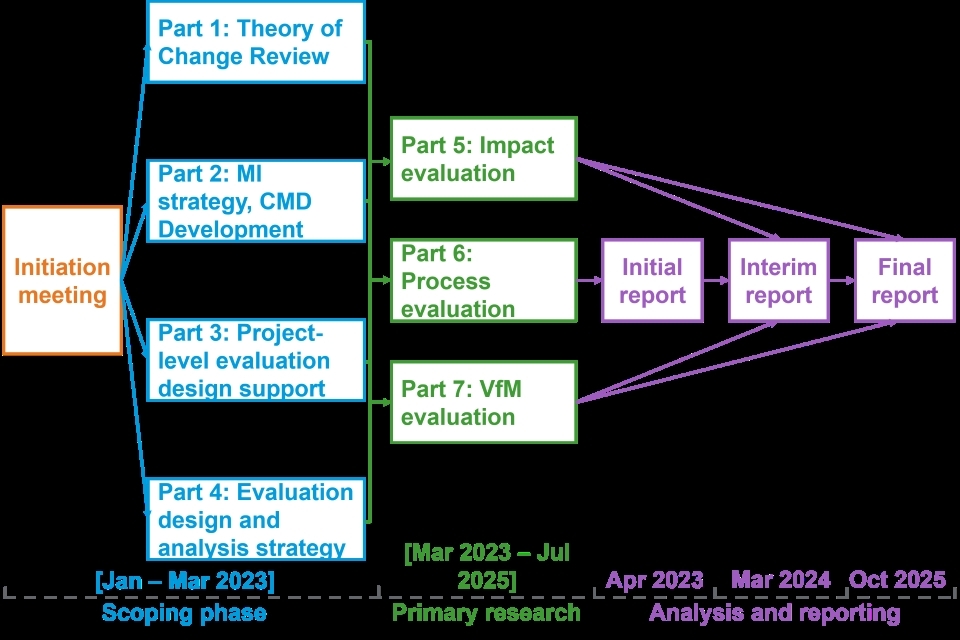

Using HM Treasury Magenta Book guidance, this evaluation will assess the effectiveness of the KYN Fund in meeting its objectives, and provide opportunities for learning and accountability for grant funding. The evaluation will also recommend improvements to support delivery of the KYN Fund and future, similar funds. This evaluation will include process, impact and value for money (VfM) evaluation.

This interim report primarily focuses on process evaluation findings gathered from interviews with the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), ACE, Historic England, UKCF, Cultural Partners, CFs and projects, as well as baseline data from participants taking part in UKCF funded projects. The final evaluation report, due 2025, will explore impact findings, using qualitative data collection and baseline, midpoint and endline survey data. The final report will also include a VfM assessment using the National Audit Office’s (NAO’s) 4Es framework.

1.3 Methodology

The findings and recommendations made in this report draw on the following sources:

-

Impact evaluation baseline survey - A survey administered by ACE and UKCF funded projects, using either an online link or a paper-based survey. The baseline survey captures key demographic data of projects’ beneficiaries and volunteers and how they felt at baseline about their wellbeing, loneliness, volunteering, skills, confidence and pride in local area. This interim report uses data from 1,853 baseline survey responses collected from September 2023 up to the end of January 2024.[footnote 5] These responses are from exclusively UKCF funded projects, as responses from ACE funded projects were not available at the interim reporting stage. Baseline survey data collection is ongoing until the Fund ends in March 2025.

-

In depth interviews – 14 interviews were held with delivery partners in March 2023. ACE, UKCF, Historic England, 3 Cultural Partners, 9 CFs and 25 projects were interviewed between November 2023 – January 2024. DCMS were also interviewed in July 2024. These interviews primarily explored process related questions, though they also had a limited exploration of impact related questions.

This evaluation will aim to gather evidence and formulate findings against 22 research questions. Research questions with low levels of evidence available at this stage will be explored more comprehensively in the final evaluation report.

1.4 Key findings

This interim report identified the following key findings, split by research question area.

Process evaluation – Set up and implementation

-

Cultural Partners, CFs and projects were strongly aligned with the objectives of the KYN Fund. Most projects interviewed were targeting both loneliness and volunteering outcomes.

-

Projects had generally positive experiences with the application process. This was largely attributed to familiar application forms and having (in many cases) pre-existing relationships with the Cultural Partners/CFs. Whilst support and guidance from Cultural Partners and CFs was offered to all applicants, those which had pre-existing relationships with the funder found it particularly easy to access support.

-

ACE had generally positive experiences with the grant distribution process, attributing this to early discussions with Cultural Partners before they accepted the grant. This allowed for immediate project delivery, without needing extra planning time.

-

CFs reported a more challenging experience with grant distribution, citing lengthy timelines for receiving funding. This meant CFs had to use their own reserves or pass on lengthy payment timelines to projects, causing gaps in projects’ delivery. This was as a consequence of the multiple layers of scrutiny required from each organisation handling money (e.g. DCMS, UKCF and CFs) to ensure the effective management of public money.

Process evaluation – Delivery

-

Projects delivered a range of activities, which were tailored to the needs of their local area. These were split between activities that were completely new and activities that built on projects’ previous activities.

-

UKCF Test and Learn Phase funding was viewed as a key facilitator to set up for projects funded in both UKCF’s Test and Learn Phase and UKCF Phase 2. The short Test and Learn Phase enabled projects to demonstrate capability, gain learning insights and be well-prepared for longer term delivery. Projects were also able to consult with local stakeholders on the needs of their communities, which allowed them to design effective targeted activities that could be mobilised at pace in UKCF Phase 2.

-

Projects found that using referral routes was effective in recruiting people who are at risk of, or experiencing chronic loneliness.

-

Projects viewed collaboration with local Voluntary, Community and Social Enterprises (VCSEs) and the expertise of their internal staff as key facilitators to delivery.

-

Cultural Partners, CFs and projects expressed mixed opinions on monitoring and evaluation requirements. Some found that both were in line with expectations, however, others found both to be excessive. Some projects encountered barriers in administering the survey, including the time required for participants to complete the survey and the projects’ burden for inputting paper-based responses on the survey link.

-

Some CFs expressed disappointment in the change from using local level evaluators.[footnote 6] This change was made to ensure that robust evaluation methods such as quasi-experimental methods could proceed and to reduce duplication between various evaluation activities.

Reach

-

Slightly more than half of respondents (56% of n=1,853) to the baseline survey up to January 2024 were volunteers. Of the volunteer respondents, half (51% of n=1,045) were new to volunteering.

-

Almost six out of ten volunteer respondents (58% of n=1,033) planned to volunteer for at least three months and two thirds (65% of n= 1,034) intended to volunteer weekly, either once or twice a week.

-

Baseline responses appear to suggest that projects were reaching people who more frequently experienced loneliness, compared with the general population. For example, 45% (of n=1,835) of respondents reported feeling lonely either some of the time, often or always (compared to 26% of adults who took part in the CLS 2023/24 [n=170,255]).[footnote 7] 15% (of n=1,835) of respondents reported feeling lonely often or always, a response usually associated with chronic loneliness, suggesting a higher prevalence than the general population (7% of n=170,255).[footnote 8]

-

DCMS identified ten groups of people that are at risk of experiencing loneliness. The baseline survey allows for a comparison of the proportion of KYN respondents who fall into three of these groups with the respective proportions in the general population. These three groups are: people who have a disability or condition lasting or expected to last more than 12 months, people who experience mental health problem, and people aged 16 to 34. Baseline responses suggest that projects were reaching people in these three groups at risk of chronic loneliness, compared with the general population:

-

Slightly more than half of respondents (51%, n=1,834) to the baseline survey reported having any kind of disability or condition lasting or expected to last more than 12 months. In the population of England, 18% reported having any kind of disability or condition lasting or expected to last more than 12 months in the Census 2021.[footnote 9]

-

The proportion of KYN baseline survey respondents reporting that they experienced mental health problems was 31% (n=1,441). This was a higher proportion compared to the general population in 2023/24, where the proportion was 23% (n=5,327, NatCen’s Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey).[footnote 10]

-

A slightly higher proportion of baseline survey respondents were aged 16 to 34 (28%, n=1,844) compared to the estimated number of adults in England in the same age bracket in 2023 (24%).[footnote 11]

-

The baseline survey suggests a higher proportion of respondents have lower life satisfaction and happiness, and higher levels of anxiety than in the general population.

-

The baseline survey suggests a higher proportion of respondents have a lower sense of belonging to their neighbourhood and satisfaction with their local area than in the general population.

-

The above points suggest UKCF funded projects may be reaching the intended audience of the KYN Fund, although this is based on partial data up to January 2024. The final evaluation report will cover baseline data, impact data and VfM findings to explore this more comprehensively.

2. Introduction and Background

2.1 Introduction

The KYN Fund is investing up to £30 million to widen participation in volunteering and tackle loneliness in 27 disadvantaged areas across England. RSM UK Consulting LLP (RSM) and the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) were commissioned by DCMS to undertake an overarching evaluation of the KYN Fund in January 2023. RSM and NatCen are responsible for delivering an impact, process and Value for Money (VfM) evaluation at a Fund level.

This interim report explores emerging findings related to Fund processes and the reach of UKCF funded projects. This interim report only explored findings from this UKCF baseline data, as responses from ACE funded projects were not available at the interim reporting stage. The findings inform lessons learned and recommendations for the Fund going forward and any future similar funds. The final evaluation report, due in Spring 2025, will build on these findings with further impact data and VfM analysis to provide an overall evaluation of the Fund. This section outlines the background to the Fund, including its structure.

2.2 Background to the KYN Fund

The objectives of the KYN Fund are, by March 2025:

-

To increase the proportion of people in targeted high-deprivation local authorities who volunteer at least once a month.

-

To reduce the proportion of chronically lonely people in targeted high-deprivation local authorities who lack desired level of social connections.

-

To build the evidence to identify scalable and sustainable place-based interventions that work in increasing regular volunteering and reducing chronic loneliness.

-

To enable targeted high-deprivation local authorities, and the local voluntary and community sector in these places, to implement sustainable systems and processes that encourage volunteering and tackling loneliness.

The KYN Fund is split into three funding streams as follows and shown in Figure 1.

-

£5 million of government funding is being invested in supporting people to participate in volunteering and connect with others through expanding the existing offer of arts, culture and heritage activities across the 27 KYN target areas. This funding is being delivered through Arm’s Length Bodies (ALBs), including, ACE and The National Lottery Heritage Fund, in partnership with Historic England.

-

£15 million of the total £20 million government funding will be delivered by UKCF and a consortium of local CFs across 9 areas.

-

The National Lottery Community Fund will invest up to £10 million of their own funding to top up existing projects that support the KYN Fund objectives, working across the same 27 target areas.

The 27 target areas in scope for this Fund were identified as high-need areas based on the English Index of Multiple Deprivation and the Community Needs Index. Eligible areas include; Barnsley, Barrow-in-Furness, Blackpool, Bolsover, Burnley, Cannock Chase, County Durham, Doncaster, Fenland, Great Yarmouth, Halton, Hartlepool, King’s Lynn and West Norfolk, Kingston upon Hull, Knowsley, Middlesbrough, Rochdale, Sandwell, South Tyneside, Stoke-on-Trent, Sunderland, Tameside, Tendring, Thanet, Torridge, Wakefield and Wolverhampton.

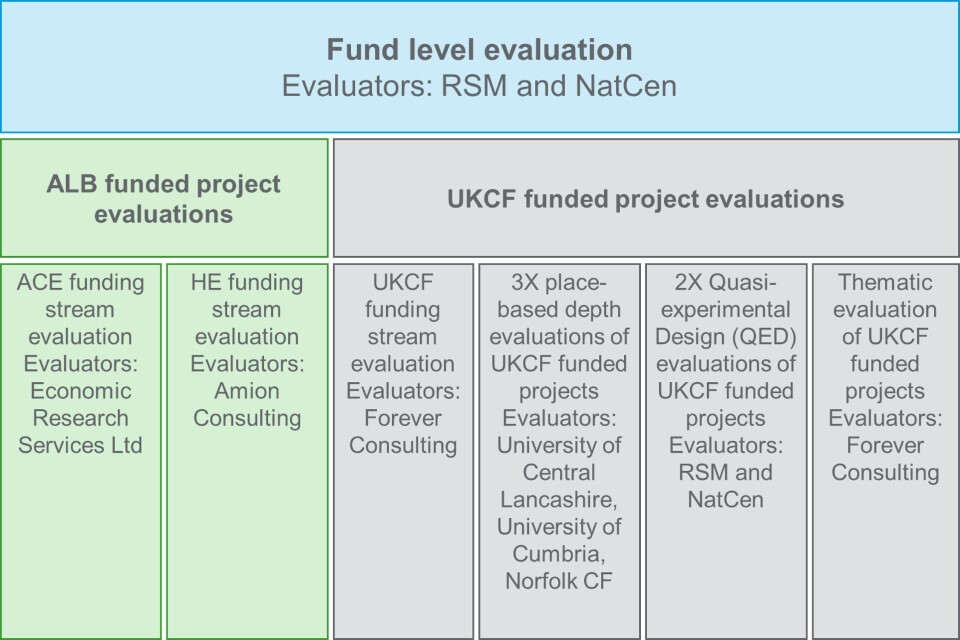

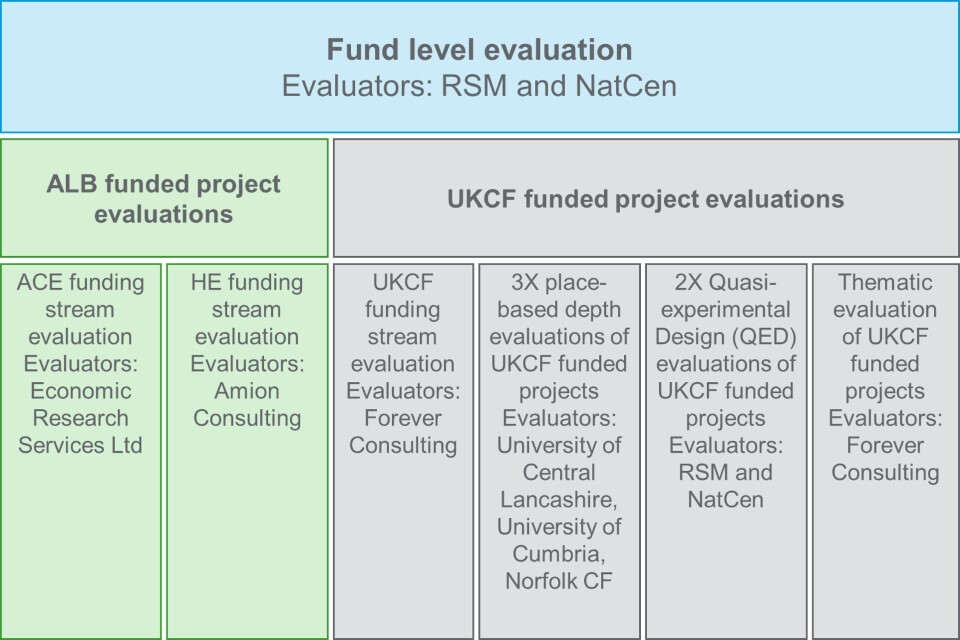

The KYN Fund has the following evaluation structure to ensure lessons learned are captured across all funding streams.

Figure 2 – KYN Fund evaluation structure

The KYN Fund evaluation structure, which shows six evaluation activities: ACE funding stream evaluation, HE funding stream evaluation, UKCF funding stream evaluation, three place-based depth evaluations of UKCF funded projects, two quasi-experimental design (QED) evaluations of UKCF funded projects and a thematic evaluation of UKCF funded projects.

2.2.1. Arm’s Length Body Projects

Through the KYN Fund, DCMS is providing £5 million in grant funding to support people to participate in volunteering and connect with others in their communities through arts, culture and heritage activities. This funding is being delivered by ACE and The National Lottery Heritage Fund, in partnership with Historic England. It will build on existing local interventions and expertise in target disadvantaged areas to boost meaningful and impactful volunteering opportunities, to bring people together, and to maximise learning about what works.

The £5 million breaks down as follows. ACE is distributing £4.3 million across three schemes, using Cultural Partners to provide onward grants, that will draw on existing community assets like libraries and museums to bring people together, including through volunteering:

-

Libraries Connected has received £2,450,000. This is being used to support libraries to engage additional volunteers and host activities such as craft groups or family sessions in the 27 target areas, through 26 library services. Libraries Connected have also contracted Economic Research Services Limited (ERS) to undertake an evaluation of all three ACE Cultural Partners.

-

Association for Independent Museums (AIM) has received £950,000. This is being used to support local museums to create new volunteering roles, help people to connect (for example through educational programmes aimed at widening participation through storytelling), and to strengthen local museums’ ability to run future programmes that tackle loneliness and support volunteering. AIM funded five projects in Round 1 and seven projects in Round 2 (see Table 2).

-

Creative Lives has received £900,000. This is being used to support voluntary arts groups to deliver arts activities that help people to connect with others. This includes funding for community choirs, music and drama clubs, and intergenerational creative activities. Creative Lives funded 10 projects in the Pilot Round and 51 projects in Round 1 (see Table 2).

In addition, The National Lottery Heritage Fund, in partnership with Historic England, has received £550,000 to support existing projects being delivered through their High Street Heritage Action Zones programme in 11 eligible high streets. These are Barnsley, Blackpool, Barrow, Burnley, Hull, Middlesbrough, Stalybridge, Wednesbury, Stoke, Great Yarmouth and Ramsgate. There is a focus on additional activities that bring people together and create volunteering opportunities connected to their local high street. The funding will also support the delivery of cultural activities that help people feel proud of and connected to where they live and their local community.

2.2.2 UKCF Projects

£15 million of KYN funding is being delivered by UKCF and a consortium of local CFs across 9 areas. The funding is supporting activities that enable volunteering and tackle loneliness in nine targeted disadvantaged areas in England. The £15m is funding projects in the following areas: Wolverhampton, South Tyneside, Kingston-Upon-Hull, Blackpool, Stoke-On-Trent, Great Yarmouth, Fenland, County Durham, and Barrow-in-Furness. UKCF are using their existing networks and expertise to ensure that funding is tailored to the specific local communities it serves.

This funding aims to support people who have not had opportunities to volunteer before, or who may be at risk of loneliness, to access enriching opportunities to connect locally. This funding aims to help these people to improve their wellbeing, skills, confidence and social connections.

The UKCF funding will run until 31st March 2025, with various projects closing at different stages. The smaller first phase of the funding up until March 2023 focused on learning (UKCF Test and Learn Phase - 95 projects funded), before opening to a larger grant-making phase in April 2023 (UKCF Phase 2 - 115 projects funded).

2.2.3 The National Lottery Community Funding

The National Lottery Community Fund is investing up to £10 million to support their existing projects working across the same target areas and working to similar objectives as the KYN Fund. This funding is out of scope of this evaluation.

2.3 Research objectives and questions

This evaluation seeks to answer a variety of process and impact related research questions (RQs) at both the Fund and individual project level. These RQs were designed to assess the extent to which the Fund has met its objectives (detailed in section 2.2) and whether it has provided VfM. Process questions relate to Fund set up and implementation and project delivery. Impact questions relate to the outcomes that projects achieve and the impacts these outcomes lead to, for both funded projects and their participants. The full list of RQs is available in Annex A 8.1.1. This report focuses primarily on process related questions, as at the time of preparing the interim report, most projects were ongoing. Therefore, it is not possible to assess the impact of the KYN Fund at this interim stage. However, this will be explored in the final evaluation report.

3. Evaluation Methodology

3.1 Overview

This report draws on findings from interviews and an initial sample of beneficiary and volunteer baseline survey data. This section briefly describes these data collection activities and details notes on interpretation of the findings. Annex A (section 8.1) provides details on the methodology , including data collection and analysis and Annex B (section 8.2) provides further detail on the theoretical basis for the evaluation.

3.1.1 Impact evaluation surveys

The evaluation team, DCMS and the evaluation partners co-developed a survey that captures key demographic data, including ethnicity, biological sex, gender identity, and age and outcome data on volunteering, wellbeing, loneliness, skills, confidence, and pride in local area.[footnote 12] For this evaluation, surveys are administered at baseline, midpoint, and endline of an individual’s participation in each project, as appropriate. The interim report analyses data from baseline survey questionnaires conducted between September 2023 and January 2024. As many projects are recruiting on a rolling basis, baseline survey collection will continue until the Fund ends in March 2025.

The survey data from the baseline collected up to 29 January 2024 included responses from n=1,853 respondents involved in UKCF funded projects. This represents a response rate of 18.5% from volunteers and beneficiaries of UKCF funded projects, up to 29 January 2024.[footnote 13]

Historic England does not use this survey because the activities delivered by their funded projects are not designed for longer term engagement by participants. At the time of this interim report, many ACE funded projects had not started delivering activities. Therefore, ACE funded project survey data is not included in this report. As the survey data has not been weighted, the analysis in the baseline survey findings section of the interim report is purely descriptive. Tests for statistical significance have not been conducted but may form part of the final evaluation report. The survey data in this report provides a snapshot of who the beneficiaries and volunteers are, up to January 2024. It allows the evaluation to consider the extent to which the Fund is reaching its intended audience based on this initial data.

3.1.2 Process evaluation interviews

The evaluation team conducted 14 interviews with UKCF, CFs, Historic England and Cultural Partners in March 2023 and 40 interviews across projects (n=25) and delivery and Cultural Partners (n=15) from November 2023 – January 2024. DCMS staff were interviewed in July 2024. The evaluation team used a purposive sampling approach to achieve a diverse sample of funded projects based on geography, the size of grant funding received and the number of targeted volunteers and beneficiaries. UKCF, ACE, Historic England, all nine involved CFs and the three Cultural Partners were interviewed.

3.2 Future evaluation synthesis

The evaluation team deemed it not necessary to conduct interviews with beneficiaries and volunteers for this evaluation. Such interviews are included within the methodologies of the two QED evaluations, placed-based evaluations, and ALB and UKCF evaluations conducted by RSM / NatCen, ERS, Forever Consulting (FC) and other evaluation partners. This means that this evaluation report does not include any qualitative insights into beneficiaries’ and volunteers’ experience of projects. This reduces burden on projects and their participants. The final evaluation report will synthesise the findings of the previously mentioned evaluations to ensure that beneficiaries’ and volunteers’ views are represented.

4. Process Evaluation Findings

4.1 Overview of data collection

This section draws on findings and insights from 14 interviews conducted in March 2023 with UKCF, CFs, Historic England and Cultural Partners, 40 interviews conducted November 2023 - January 2024, 15 of which were conducted with UKCF, ACE, the CFs, Historic England and Cultural Partners, and 25 with UKCF and ALB funded projects and one interview with DCMS staff in July 2024. These interviews focused on the process related RQs outlined in section 8.1.

4.2 Process findings

This section includes key findings and lessons learned, particularly pertaining to DCMS or future funders.

4.2.1 Set up and implementation

Selection of the Intermediary Grant Maker and Arm’s Length Bodies

Following extensive stakeholder testing, DCMS concluded the KYN Fund would be most effectively delivered through a mix of ALBs and an Intermediary Grant Maker (IGM), with the IGM focussing on place-based approaches. DCMS worked collaboratively with ALBs to identify ACE and the National Lottery Heritage Fund in partnership with Historic England as the best placed ALBs to deliver the funding stream relating to arts, culture and heritage. To select the most appropriate IGM, DCMS held an open competition. Following this competitive process, DCMS appointed UKCF as the IGM.

Selection of Cultural Partners and CFs

Key Finding: Cultural Partners were selected based on their strong alignment with the KYN Fund objectives, which worked effectively.

Following initial discussions with DCMS, ACE identified AIM, Creative Lives and Libraries Connected as suitable Cultural Partners to deliver the Fund’s objectives. ACE regularly works with the Cultural Partners and considers them to be “strategic partners” with which they have strong relationships. ACE selected the Cultural Partners based on their networks’ strong reach within target communities and their established systems to deliver similar kinds of projects. Cultural Partners said their strategic objectives strongly aligned with the objectives of the KYN Fund, in particular supporting people at risk of loneliness and building an evidence base around loneliness and social connections.

There was a really good match between KYN and one of [our organisation’s] strategic priorities which is about developing an evidence base for how our groups support social connectedness and combat feelings of loneliness. As an organisation which exists to promote and advocate for voluntary-led activity, the volunteering element was also a good match.

- Cultural Partner.

Key Finding: The selection process of CFs worked effectively and was based on strong alignment to KYN Fund objectives.

UKCF managed the process of selecting the nine CFs that would distribute funding from the KYN Fund. In their application, UKCF selected ten CFs from a pool of 12-13 eligible CFs, based on their alignment with DCMS’s Fund criteria. One of the ten proposed CFs was not included in the KYN Fund due to concerns regarding their capacity and lack of experience delivering similar programmes. Like ACE, UKCF also focused on CF’s capacity to generate lessons learned and evidence on supporting volunteering and those at risk of loneliness:

Over the next few years, we are keen to move towards more learning focused programmes… We wanted to ensure the CFs understood that a key output for the KYN Fund was learning, not just impact, so we had to assess their capacity to do that.

- UKCF.

The CFs’ interviewed said their strategic objectives were well aligned with the objectives of the KYN Fund. Some CFs said they had an existing organisational focus on addressing loneliness. Others were concentrated on increasing the availability of, and participation in, volunteering. Many CFs interviewed considered both areas to be of priority for them, showing strong strategic alignment with the KYN Fund.

Cultural Partners’ and CFs’ experience of the application and selection process of projects

Key Findings: The Cultural Partners used a variety of tailored application approaches to reach projects that support the KYN Fund’s objectives. CFs valued the opportunity to discuss applications with projects. UKCF funded projects benefited from two funding rounds which allowed them to test and improve their approaches over time to help meet KYN Fund objectives.

The Cultural Partners had predominantly positive opinions on the application and selection process. Their only major concerns were regarding the time it took to set up the fund and launch applications, which was longer than expected. This had a subsequent impact on projects’ delivery timelines.

Libraries Connected used a non-competitive grant process to ensure that all eligible library services could access the grant. They offered multi-year grants to provide certainty for library services. They also supported the library services in shaping a proposal that passed a review panel process with the twin aims of ensuring high quality projects and improving library services skills in developing and delivering successful bids.

Creative Lives used a competitive application approach with a pilot phase in five priority areas. Feedback from the pilot was used to refine the process, before opening up to all 27 priority areas. One of the key changes was to introduce an Expression of Interest (EOI) stage for larger awards.

AIM used a competitive application approach that included an EoI stage. AIM held two application rounds to allow projects to refine their applications. The EoI stages that Creative Lives and AIM used intended to narrow down applications to those most likely to achieve the Fund’s aims.

Historic England invited 13 eligible projects to apply for the funding.[footnote 14] Historic England requested proposals for new activities that built on the High Street Action Zone’s existing cultural programmes and aligned with KYN Fund objectives. Historic England believed that their decision to take a focused approach by targeting existing High Street Action Zone delivery partners contributed to the success of their application process within the shorter timeframe. Historic England provided onward grants for a shorter period of time compared with other Cultural Partners, with their grants concluding in August 2024.

Creative Lives received a roughly even split of applications between arts organisations and community organisations. They found community organisations scored better in terms of demonstrating their ability to work with people who are at risk of loneliness and social isolation and arts organisations scored better in creative ideas for delivery. AIM identified and reached out to projects in priority geographical areas that did not apply for the first round of funding. AIM said this helped to encourage applications from smaller organisations and mitigated against the concern that small organisations could struggle to successfully express how their activities tackle loneliness.[footnote 15]

During interviews, CFs noted that most of the projects they selected in the UKCF Test and Learn Phase were delivered by projects the CF had worked with in the past.[footnote 16] CFs noted that a key contributing factor to this was that these projects were better able to demonstrate capability and capacity to deliver effectively in short timeframes in their applications. For UKCF Phase 2 funding, CFs held competitive, open calls for applications. Some CFs utilised a rolling application process. Others had a short application window. CFs often engaged in initial conversations with projects that expressed interest to ensure they had a thorough understanding of the Fund’s priority themes and delivery timelines. CFs also supported projects with any issues they experienced during their applications.

Lesson learned: Short set up and application phases reduce the ability of delivery partners to provide onward grants to a diverse range of organisations. A few Cultural Partners and CFs felt that having multiple application rounds helped them reach a variety of organisations, though this may be conflated with subsequent application rounds having greater time for setup.

Some of the Cultural Partners cited delays in launching their onward application processes. They highlighted various causes of this, including organisational capacity, finalisation of the evaluation framework and ongoing discussions on how they should structure their application phases. CFs also cited delays in launching their applications, which they attributed to the timeframe to finalise the evaluation framework.

CFs found that discussing the Fund’s aims and objectives with potential funded projects was valuable in ensuring projects had a comprehensive understanding of chronic loneliness and its framing for the KYN Fund. CFs encouraged projects to collaborate to reduce the number of applications delivering the same activities in the same area. Describing the process, one CF noted:

We held a workshop in [the local area] where we spoke about what the aims of the Fund are and to clarify their [projects’] understanding of chronic loneliness, how volunteering could be improved in the area and how people can collaborate. Also, because there are only so many volunteers in the area, organisations are often fighting for them, so from the outset we wanted groups to work together.

- CF.

CFs changed their application processes and selection criteria over time. For instance, they extended the time projects had for applications and conducted more promotional activity to raise awareness of the Fund. In the UKCF Test and Learn Phase, a few CFs found that partnership proposals worked well to achieve the Fund’s objectives and therefore preferred partnership-based applications in the second funding phase. Many CFs chose to provide onward grants in UKCF Phase 2 to projects that delivered well in the UKCF Test and Learn Phase. This allowed projects to test and refine their approaches before the longer funding phase.

Some groups really valued the opportunity to pilot or research something before going into a grant application for a longer period. It worked well for some groups.

- CF.

Most of the projects who participated in the UKCF Test and Learn Phase tested delivery approaches. These projects benefited from this experience, as it allowed them to “hit the ground running” in UKCF Phase 2. Many of the projects stated that they held some form of consultation, focus group, workshop or informal survey with their prospective participants to identify the area and community needs that could be addressed by their interventions.

Lesson learned: A short testing phase before committing to longer-term funding enables projects to demonstrate capability, gain learning insights and be well-prepared, before longer term delivery.

During interviews, CFs fed back that the KYN Fund could have benefitted from more clarity on its priority outcomes and a clearer distinction between its focus on volunteering on the one hand and (chronic) loneliness on the other hand.[footnote 17] Understanding of chronic loneliness was not fully developed from the outset for projects and some Cultural Partners / CFs. DCMS recognised that the sector may benefit from discussion around the differences between loneliness, chronic loneliness and social isolation and held a ‘KYN Day’ in March 2023. This brought together all the programme, delivery, evaluation and learning partners in one place, set out the purpose of the KYN Fund and its evaluation, outlined the respective roles of RSM, NatCen and FC, and sought feedback on initial evaluation and data collection plans.

Lesson learned: Delivery partners should ensure that Fund objectives are clearly communicated to funded projects. In cases where there is one lead delivery partner who works with multiple other partners to deliver a fund, the lead delivery partner should take all steps necessary so that their partners also fully understand the objectives. Where there is a perceived lack of clarity around Fund objectives, delivery partners should seek to clarify their understanding with Funders as early as possible.

Project experience of the application and selection process

Most projects interviewed found that their CF’s application process was in line with their expectations. Projects that applied for UKCF’s Test and Learn Phase found UKCF Phase 2 application rounds easier to complete because they knew what to expect. Whilst projects said that the KYN application form was slightly different from typical CF application forms, most found that the additions made for the KYN Fund were not onerous.

Projects interviewed were positive about their interactions with CFs and Cultural Partners during the application process. Projects said that CFs and Cultural Partners made themselves available to answer questions and gave guidance on project design and application completion. Most UKCF funded projects that received support from their CF said that their pre-existing relationships helped facilitate this support. These projects had connections to access support, and the support could be more tailored as the CF staff had knowledge of the projects’ existing activities and expertise.

Lesson learned: CFs were able to utilise their local knowledge and connections to give support to prospective projects that were experiencing difficulties during their application.

Grant distribution

Key Findings: Early engagement between Cultural Partners enabled them to refine their onward grantmaking approach effectively.

ACE felt their grantmaking with the Cultural Partners worked well. They partially attributed this to their ability to have early discussions with the three Cultural Partners in advance of accepting the grant from DCMS. This meant the Cultural Partners had a few months to prepare their project plans before they were awarded the grant. Once the grant was awarded, the Cultural Partners were able to start delivering the onward grant award programme with their projects rapidly Facilitating these early discussions with Cultural Partners is an approach ACE intends to replicate for future Funds. Cultural Partners agreed that this worked well.

Many CFs expressed frustrations with payment timelines. Some CFs had to disburse grants before receiving the funding, using their own reserves, whereas others delayed sending funding to their projects. The grant disbursement process involved multiple parties, with scrutiny required by each party to ensure public money was effectively managed. Therefore, CFs and projects interviewed felt the grant disbursement timelines were lengthy.

Our finance team didn’t want us releasing funding we hadn’t received yet, so we had to go through and choose the groups we thought might need paying more upfront so they could get more funding in the first tranche. We also thought some of the larger groups might be able to bankroll themselves, so we prioritised funding smaller groups. This caused a two-month delay for four or five of our groups.

- CF.

Lesson learned: Payment processes are lengthy, with multiple layers of scrutiny required from each organisation that handles the money (DCMS, UKCF and CFs) to ensure the effective management of public money. Government and delivery partners should work together to ensure adequate timelines are set out for funding to reach grantholders.

Delays in the launch of the FY 2023/24 application process impacted CFs’ grantmaking timelines and projects said that delays in the grantmaking process caused delays to their planned delivery. These delays were as a consequence of the significant time and resourcing that was required to set up a robust and complex evaluation across multiple delivery partners. As a result of the longer timelines, projects that had to postpone operations spent the extra time on project set-up and recruitment. A small number of projects were able to continue delivery of some of their activities in the interim using their own funding.

Lesson learned: Having sufficient time for grant set up enables early discussions with delivery partners, which can streamline project preparation, enabling immediate delivery upon grant award. However, capability to do this can be constrained by the need of Government to align with annual business planning cycles.

4.2.2 Delivery

This section discusses the characteristics of the KYN funded projects, and how the projects aim to address the objectives of the Fund. It also presents the experience of project delivery from the perspective of the funded projects, the CFs and Cultural Partners.

Interventions delivered by KYN Fund projects

Key Findings: Most projects interviewed are delivering activities that aim to both reduce loneliness for people at risk of or experiencing chronic loneliness and increase regular volunteering.

Most of the projects interviewed aimed to connect people to their local community through their project work. This led to funded projects offering a range of tailored activities that reduce the need of participants to spend money on socialising, particularly in areas of high deprivation. Projects interviewed also reflected on the impact of the cost-of-living crisis, which widened the pool of people seeking support. In response, projects provided varied advice and support for expenses such as clothing, energy bills, travel costs and food to participants.

Some projects interviewed tackled wider problems faced by their local community, such as consequences of COVID-19, women’s health/safety, suicide and youth disengagement. In most cases, projects focused on issues that they identified as contributing to social, physical or financial isolation.

Interviews with projects suggested that most of the interventions delivered by ALB funded projects were based on existing projects, which they expanded using the grants they received. These projects focused on creative activities (such as gardening, cooking and textiles) and educational activities (such as workshops that help develop basic English language, IT and mathematical skills).

The UKCF funded projects interviewed delivered an even mix of new and existing interventions. Activities included hosting food banks, providing hot meals, arts and crafts, wildlife work, social work groups, homeless hostels, employment / domestic skill development, mathematics / English classes, health and wellbeing services, networking and training. Some projects also signposted participants to other services within their organisation to ensure individuals have access to appropriate support.

Interviews with CFs indicated that the local areas targeted by the KYN Fund are well suited to the KYN Fund objectives. Most CFs said that their areas have low levels of infrastructure, were typically underfunded and have a high proportion of people at risk of, or experiencing chronic loneliness. Projects interviewed also expressed that their activities had strong alignment with the KYN Fund objectives.

Projects that received multi-year funding expressed that this added security to their work. These projects said that they expect that this will help them deliver longer-term activities that are better suited to alleviating chronic loneliness and increasing sustained volunteering.

This is the first time in about ten years that I have not had a redundancy notice in December. It does not mean I’m always worried about not having a job in January. It just means that within the voluntary sector, there is not that consistency and that can be quite difficult.

- Project.

Lessons learned: Increasing sustained volunteering and reducing chronic loneliness complement each other as target outcome areas when designing and delivering interventions. The KYN Fund objectives aligned well with the needs of the areas eligible for the KYN Fund.

Who are the projects targeting and reaching?

Key Findings: Most projects interviewed targeted their activities at specific demographics of people from their local area, in particular people at risk of, or experiencing chronic loneliness. Projects interviewed said they were generally successful in reaching their intended audience.[footnote 18] Projects had a mixed understanding of social isolation, loneliness and chronic loneliness.

A few projects interviewed chose to not target their activities at specific demographics, allowing them to be accessed by all members of their community, utilising a demand led approach. However, most projects clearly defined the demographics they were targeting with their activities. Many projects interviewed defined their audience using gender, sexuality, age, ethnicity, employment status and disability. Where these projects had a clearly defined target audience, if someone who did not fall into their target audience tried to access their activities, projects would often refer those people to other local organisations for support. For example, one project said:

We only work with over 18s. One of the projects that received [KYN] funding work with young people so that’s no problem. If we get anyone under 18, we are more than happy to refer on those young people.

- Project.

Lesson learned: Focussing funding in distinct geographic areas can allow funded organisations to refer beneficiaries to each other.

Most projects interviewed targeted people at risk of, or experiencing chronic loneliness, and were able to strongly articulate what chronic loneliness means. A few projects interviewed were either unsure how to define chronic loneliness or were unclear on how it differed from social isolation. Projects highlighted in interviews that anyone could experience chronic loneliness. Illustrating the differences between social isolation, loneliness, and chronic loneliness, one project explained:

Loneliness [is] when you have that feeling, that psychological kind of feeling, of being alone. Opposed to being isolated where you are physically alone. Some people who are struggling with loneliness can be in a room full of people and still not feel that connection. You can be isolated and lonely, or lonely, or just isolated and not feel alone. Whereas that chronic loneliness usually means it has gone on for a long period of time.

- Project.

Many projects interviewed found that the people who accessed their activities and volunteering opportunities were their intended audience. Projects highlighted numerous factors that contributed to this, including:

-

Projects’ knowledge of the local area: Projects interviewed demonstrated a high level of understanding of the local area in which they are based. This local approach allowed them to target their activities at the people in the local area. For example, projects based in areas with large communities of refugees and asylum seekers would target these communities with their activities.

-

Communities’ knowledge of the projects: Projects interviewed highlighted that their organisations were often well known within their local communities. As a result, their local community was aware of what services they offered and who these services were aimed at.

A few projects interviewed found that the demographic of participants they recruited differed from the demographic they initially intended to target. In some instances, projects were willing to recruit people who did not fall into their target demographic. These projects said that this allowed them to promote positive outcomes in a wider demographic than they originally intended.

Recruitment techniques used by projects

Key Findings: Referrals from other organisations such as GPs and social prescribers was one of the more prominent recruitment techniques projects used. Projects interviewed said these referrals were effective in identifying, reaching and recruiting people at risk of, or experiencing chronic loneliness.

Projects interviewed reported using multiple techniques to ensure they reached as many people in their target audience as possible. These techniques included using launch events, advertising in newsletters / mail lists, word of mouth, social media and ‘door knocking’.

Some projects interviewed said they structured their activities so that people would join as a beneficiary, engage in activities, and then progress into a volunteering role. Others found that beneficiaries were appreciative of the services they received and wanted to ‘give back’ to people in similar situations as themselves by becoming a volunteer.

The most common recruitment technique projects interviewed reported using was referrals from other organisations. Projects used their existing networks to gain referrals from GPs, social prescribers and local VCSEs. Projects interviewed said referral routes were an important method of recruiting people at risk of, or experiencing chronic loneliness, as they are often in regular contact with GPs and social prescribers. Projects explained that people who are chronically lonely can be hard to reach using other recruitment techniques and stressed that GPs, in particular, are well placed to identify chronic loneliness.

Those people who are struggling with loneliness, they are not going to go out to seek activities. It usually has to be organisations seeing a red flag and then going to them.

- Project.

A few projects interviewed offered services such as food banks, food parcels and community dinners. They said that they were an effective way to identify and recruit people at risk of, or experiencing chronic loneliness.

The good thing about the hot meals is because there are no referrals, no questions asked, anyone can come. We sometimes find we do manage to reach those really isolated people who do not fit into the other boxes; do not qualify for a referral, do not want to socialise.

-Project.

Interventions that focused on volunteering used a range of methods to target new volunteers including outsourcing recruitment through volunteering networks. These networks brought in new volunteers and engaged with existing volunteers. A few projects interviewed reported successfully relying on word of mouth and drop-in centres as their primary recruitment approach, while others relied on their own staff, including volunteer coordinators and community engagement workers to recruit volunteers. Some projects had to first recruit a volunteer coordinator, causing delays in onboarding volunteers.

Projects interviewed acknowledged a number of barriers which affected their ability to recruit volunteers. Most barriers were specific to individual projects, such as getting Disclosure and Barring Service checks, changing IT systems and lacking reputation in the local area. Some barriers were reported by multiple projects. The aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic was one of these barriers. Projects interviewed said that the pandemic made certain demographics, in particular older people, reluctant to engage in social activities.

A few projects highlighted that the quality or availability of transport links made it difficult for some volunteers and beneficiaries to travel to activities. This barrier was compounded by factors such as the rurality of areas, and volunteers and beneficiaries’ limited understanding of public transport systems. This particularly affected groups such as refugees and asylum seekers.

Facilitators and barriers to delivery

Key Findings: The most common delivery facilitators reported in interviews were collaboration with other local organisations and internal staff expertise.

Whilst few projects interviewed were involved in formal partnership bids for the KYN Fund, most projects collaborated with other organisations within their local area. Most of this collaboration was with other VCSE organisations, though some projects collaborated with schools, colleges and local authorities. A few projects said they collaborated with organisations they had not worked with before, but most collaborated with those they had worked with before.

Projects interviewed cited many benefits of their collaboration, with the main benefit being referrals. A few projects also cited knowledge and skills sharing which allowed them to offer activities they could not offer alone. Projects were able to discuss common barriers and issues they faced, which allowed them to tailor their offering to be more reflective of the needs of their community.

Projects interviewed said that a strong volunteer coordinator was a facilitator to their delivery. This was because a qualified individual overseeing volunteer experience and wellbeing, facilitated the recruitment and retention of volunteers. The design of some projects, who approached beneficiaries to become volunteers, was a facilitator for good quality volunteers. Participation in project activities familiarised volunteers with the organisation and helped make them feel comfortable.

Projects interviewed recruited some staff that were representative of their local community in terms of their demographic and lived experience. This included members of staff that speak multiple languages, who could assist with translation and communication.

A few projects said that delivery to certain cohorts proved more difficult than others, and this required adaptation to delivery in some cases. For instance, projects reduced the length of some activities for older people to make it easier for them to participate, as some of the beneficiaries struggled to physically engage with the original activity length. Another barrier was access to good quality internet for beneficiaries which meant some projects had to redesign their delivery approach, for example:

We’ve had to revise the plan for that, it wasn’t in the application, just our plan. We’ve booked a more central location which is in the actual town centre and we’ve got a programme of events in one venue. It’s a slightly different model to what we’ve planned…to me it [internet] is like a utility now really, it didn’t even to be honest cross my mind that [beneficiaries] wouldn’t have it.

- Project.

A minority of projects interviewed noted that not having their own physical space, or not enough space, was a barrier to delivery. For one project, this caused difficulties in scheduling year-round delivery as they have to hire out-sourced spaces.

Lesson learned: Funders should actively promote or encourage partners to take actions that facilitate collaboration among funded projects. This would provide an opportunity for projects to share learnings about delivery and the evaluation process.

CFs and Cultural Partners’ experience of grant monitoring

Key Findings: Some CFs and Cultural Partners interviewed found that monitoring and reporting requirements for the KYN Fund were more substantial than they are accustomed to. This was due to both the relatively large size of the grants (compared to other grants CFs and Cultural Partners have provided) and the focus of the Fund on learning and evidence building. Nonetheless, projects reported feeling sufficiently supported by their CF or Cultural Partner.

CFs reported that the monitoring and reporting requirements led the CFs to take a more stringent approach to grant management than usual. A few CFs and Cultural Partners noted that grantmaking of this scale was larger than the grantmaking they were accustomed to, both in terms of grant size and fund length. This required more frequent check-ins with projects, but they did not view this as a challenge. To support projects, a few CFs facilitated face-to-face workshops as an opportunity to share lessons learned on delivery and the grant monitoring process. One Cultural Partner assigned each project a mentor with skills and knowledge aligned with the projects’ objectives. These mentors provide advice, serve as a sounding board and signpost to other sources of support.

Most of the Cultural Partners expressed that ACE was highly supportive with their monitoring requirements and often helped to streamline the process for them. Some Cultural Partners and CFs felt the monitoring requirements were too high. Cultural Partners and CFs felt that there was insufficient clarity about the monitoring requirements in the early stages of delivery. This resulted in their funded projects being unable to integrate monitoring approaches into their delivery from the outset. As delivery progressed, CFs and Cultural Partners found it easier to manage and navigate monitoring requirements.

It has been complex to get off the ground. Some monitoring we weren’t aware of when the process started so we have had to collect this retrospectively, which is always going to be tricky.

- Cultural Partner.

Most projects interviewed found that monitoring requirements and frequency were clear and appropriate. Whilst a few projects interviewed cited issues with frequency of monitoring and understanding requirements, these projects generally found that their experience with monitoring improved over time.

There’s the 3-monthly reporting that we do to the CF which is fairly standard… that’s absolutely fine.

- Project.

Most projects interviewed were positive about their interactions with CFs and Cultural Partners. Those that had interactions with their CF or Cultural Partner expressed that they were helpful and responsive. Most projects said that during delivery they had minimal contact with their CF or Cultural Partner as they did not need much support.

CFs and Cultural Partners’ experience of evaluation requirements

Key Findings: Cultural Partners expressed mixed experiences with the evaluation during interviews; some found evaluation clear and appropriate, whereas others felt it may confuse projects. This highlights the challenges in designing and implementing an evaluation of the complexity and scale required for the KYN Fund.

Half of the Cultural Partners found the evaluation approach clear and understood its purpose. They appreciated the regular communication from the evaluation partners. One of the Cultural Partners believed their strong buy-in for the evaluation approach from the outset resulted in their projects’ having a clear understanding of its importance and subsequent buy-in.

We are really pleased to be part of a programme which is being so extensively evaluated and that has got DCMS and ACE so involved. Everyone has worked through in detail what it will look like and there will be some valuable results.

- Cultural Partner.

However, other Cultural Partners interviewed disagreed and found the approach excessive and confusing for projects to navigate.

Numerous CFs and Cultural Partners cited confusion regarding the multiple evaluation partners involved at various levels of the Fund’s evaluation. This confusion meant they were unsure what data and information needed to be sent to whom, and how to explain this to the projects. The purpose of these different levels of evaluation was not clearly communicated, leading to a perceived “clunky” process that could have been more efficient.

It was set out in the application guidance for the IGM that the IGM should set out plans to ensure grantees are incentivised to conduct experimental or quasi-experimental evaluations. DCMS worked with UKCF to design an evaluation framework to deliver QED evaluations. Given the expense of this type of evaluation, it was not possible to fund local evaluations for all nine areas, however, through a competitive process three CFs are undertaking local research.

UKCF and some CFs highlighted in interviews that there was a missed opportunity for co-design of evaluation approaches with CFs and projects, which they perceived to be one of the benefits of a place-based approach. Co- development was implemented into some aspects of the evaluations, such as the ToC design. ToC development workshops were held in February 2023, with stakeholders from DCMS, UKCF, CFs, Historic England, ACE and Cultural Partners

During interviews, UKCF and several CFs conveyed disappointment regarding the absence of local evaluators in the final evaluation approach. CFs highlighted that a key reason for their interest in the Fund was the strong learning element. Many were particularly interested in the prospect of receiving designated funding for a local evaluator. Without the local level evaluators, UKCF and CFs said that the evaluation became increasingly centralised and expressed concern that this would lead to evidence and lessons learned being lost at a project and local level. Conversely, there were also concerns that the inclusion of local level evaluations would cause duplication of activity and potentially dilute the robustness of evaluation learnings.

Projects’ experience of evaluation

Key Findings: Projects interviewed reported mixed experiences with evaluation requirements. In particular, projects interviewed reported difficulties with administering the survey.

A few projects interviewed were appreciative that the evaluation requirements were clear from the outset as this allowed them to set aside appropriate time and budget to fully engage in the evaluation. A few projects interviewed also had positive experiences with the survey. Those who said this stressed that the online link was easy to use, and that beneficiaries and volunteers were willing to complete the survey once its purpose was explained to them.

However, the majority of projects interviewed had mixed or negative experiences with the survey. Their reasons are listed below.

Burden of using the paper-based survey: digital exclusion was acknowledged as a potential barrier to survey completion. To mitigate against this, the evaluation partners developed a paper-based version of the survey and issued guidance on its use, which projects interviewed felt was successful. Use of the paper-based survey was higher than expected. From November-December 2023, projects were asked to estimate the percentage of their surveys that were completed using the paper-based format. Of 57 projects, around half (50.9%) said over half of their respondents used the paper-based format. Whilst projects interviewed highlighted that using a paper-based version of the survey was effective in gathering responses from digitally excluded people, they also highlighted this had an administrative burden.

We have to keep putting these [surveys] in and we have no admin people. So, I’m going to have to take people off doing their work to start putting all this lot in

- Project.

DCMS has been working with partners to explore approaches to support projects to administer the survey.

Time taken to complete the survey: a few projects said that there were too many questions in the survey, which intimidated recipients and led to long completion times. Some people struggled to understand the survey, which further increased the time taken to complete it. For instance, this affected people with learning disabilities or those for whom English is a second language.[footnote 19] To aid accessibility, evaluation partners developed an Easy Read version of the survey.

Some of our people are taking an hour to go through [the survey].[footnote 20]

- Project.

Delays in providing the survey: some projects started delivery before the survey link was available. When the link was made available, projects were asked to get volunteers and beneficiaries to complete the survey as if they were answering it at the start of their activities. Projects said this was a difficult concept to explain to their volunteers and beneficiaries.

A few projects also said that they were able to pursue their own evaluation activities, such as case studies and narrative stories, which they could use for their own means, and which complement the Fund level evaluation.

4.3 Summary

The selection of Cultural Partners and CFs was effective and led to strong alignment of delivery partners and subsequent projects with KYN Fund objectives. Projects interviewed generally had positive experiences with the application process. The application process could have been more effective if the Theory of Change and priority metrics were established prior to project launch to minimise delays in grantmaking timelines. However, this is not always possible given the constraints of Government annual business planning cycles.

ACE generally had positive experiences with the grant distribution process, attributing this to early discussions with Cultural Partners before they accepted the grant. This allowed for immediate project delivery without needing extra planning time. CFs reported a more negative experience with grant distribution, citing lengthy timelines for receiving funding, which meant some CFs had to use their own reserves or pass on lengthy payment timelines to projects, causing gaps in funding and delivery. The payment processes were lengthy given that multiple layers of scrutiny from organisations handling money (DCMS, UKCF and CFs) are required to ensure the effective management of public money.

Many projects used referrals from other organisations, including GPs and social prescribers, to recruit beneficiaries and volunteers. Consequently, projects viewed collaboration and their local relationships as key facilitators to delivery.

Cultural Partners, CFs and projects had mixed and sometimes conflicting opinions on monitoring requirements. Some found that monitoring requirements were in line with expectations, but others found that they were excessive, too frequent, and were unclear at the outset. They similarly had mixed opinions on evaluation requirements. Many valued the focus on learning from the Fund, while others expressed disappointment in the lack of local evaluations. Given the expense required to implement robust evaluation methods, it was not possible to fund local evaluations for all nine areas, however, through a competitive process three CFs are undertaking local evaluations. This approach was taken to maximise the consistency and robustness of evidence needed to answer the Fund aims, whilst also reducing duplication in evaluation activity.

5. Baseline Impact Findings

5.1 Overview of data collection

This section draws on baseline survey responses from n=1,853 respondents from UKCF funded projects to provide a descriptive overview of the initial profile of beneficiaries and volunteers. In addition to survey data, this section presents emerging interview findings relating to outcomes.

DCMS set out ten groups that were viewed as most at risk of chronic loneliness (see Annex B, 8.2.3). The baseline survey only captures data on three of the groups. Therefore, this section does not assess the extent to which these ten groups were reached. Instead, this section explores reported levels of loneliness from the baseline survey.

5.2 Baseline survey findings

5.2.1 Demographic characteristics of the sample

The baseline survey was completed by a portion (18.5%, n=1,853)[footnote 21] of potential respondents up to January 2024, and it collected the basic demographic information described below. This has provided a snapshot profile of the beneficiaries and volunteers UKCF funded projects reached up to the end of January 2024. The full data tables for this initial profile of beneficiaries and volunteers are available in Annex C. A more comprehensive picture of the demographic characteristics of the sample will be available within the final evaluation report.

Age: Respondents were distributed across all age brackets. Most (90% of n=1,844) were between 16 and 74 years of age, and the two most represented age brackets were 55-64 and 35-44 (respectively 18% and 17% of respondents). Almost three respondents out of ten (28%) were between the ages of 16 and 34, a slightly higher proportion than the general population estimate for England (24%).[footnote 22]

Disability: Approximately half of the respondents (51% of n=1,834) reported having a mental or physical health condition or illness lasting or expected to last 12 months or more. This is a higher proportion than the 18% observed in the general population in England.[footnote 23] Of those who reported a mental or physical condition, more than eight out of ten (82% of n=914) described their condition as limiting their everyday life either a little (49%, or 24% of all 1,853 respondents) or a lot (34%, or 17% of all 1,853 respondents).[footnote 24] Respondents were also asked if their health conditions and illnesses affected them in a variety of areas (such as dexterity, hearing, memory, mental health, mobility, and vision). More than a quarter of respondents (26% of all 1,853 respondents) reported mental health conditions, two out of ten (20%) reported mobility issues, and 15% reported issues with learning, understanding and concentrating.

Ethnicity: Seven respondents out of ten (72% of n=1,822) described themselves as White British, and the next largest ethnic group (10%) was represented by Asian and Asian British respondents. People from other ethnic groups also took part in the survey: White Irish and other White ethnic backgrounds (5%), Black and Black British (4%), mixed ethnic backgrounds (2%), and other ethnic backgrounds (5%).

Sex at birth and gender identity[footnote 25]: Respondents were asked about the sex they were assigned at birth and then if this corresponded to their gender identity. Almost two-thirds of respondents (63% of n=1,843) reported being female against approximately a third (37%) male. Most respondents (97% of n=1,830) reported that their gender was the same as their sex assigned at birth. A small proportion of respondents preferred not to respond to the question on gender identity (2%).

5.2.2 Volunteering

The main aims of the Fund with regard to volunteering are:

-

To increase the number of volunteering opportunities in the 27 targeted disadvantaged areas in England;

-

To increase the proportion of people who regularly volunteer in the 27 targeted disadvantaged areas in England; and

-

To increase the evidence to identify scalable and/or sustainable place-based interventions that increase regular volunteering and reduce chronic loneliness (only for UKCF funded projects).

Part of the survey, therefore, focused on the experience of volunteers, who constituted more than half (56% of n=1,853) of the respondents. Half (51% of n=1,036) of the volunteers who participated in the survey were volunteering for the first time ever, and two out of ten (19%) of the volunteers were returning to volunteering after one or more years. Of those who had previous experiences with volunteering outside of the KYN Fund (n=500), almost four out of ten (37%) had already volunteered at least once in the month before the completion of the survey, two out of ten (18%) had volunteered at least once in the year before, 10% had volunteered between one and two years before completing the survey, and almost three out of ten (29%) respondents had volunteered at least once over two years before the survey (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – When was the respondents’ last experience of volunteering, before KYN.

| In the past month | 37% |

| Less than a year ago | 18% |

| 1-2 years ago | 10% |

| More than 2 years ago | 29% |

| Cannot remember or not sure | 6% |

Volunteers were also asked about their volunteering intentions regarding the duration and frequency of their volunteering experience. Given the preliminary nature of the baseline findings, it is not possible to draw any conclusion from the intentions expressed by the beneficiaries. However, at the time of the completion of the survey, more than two thirds (68% of n=1,033) of volunteers already had an idea of the desired duration of their volunteering experience (their intention ranged from more than six months [47%] to 3-6 months [11%], 1-2 months [5%], and less than a month [6%]), while nearly a third (32%) of volunteers did not know or were not sure how long they would volunteer.

Regarding the frequency, at the time of completion of the survey, almost eight out of ten (77% of n=1,034) volunteers already had an idea of how frequently they wanted to volunteer (their intention ranged from twice a week or more [30%], to once a week [35%], to once a fortnight [5%], to less than every two months or ad hoc [1%]), while 12% of volunteers said that the frequency may vary over time, and 11% reported not knowing or being unsure. Three quarters (75%) of volunteers would fall into the category of regular volunteer as defined by the ToC (i.e., volunteering at least once a month), if they volunteered as much as they intended to at the time of completing the survey.[footnote 26]

5.2.3 Loneliness

With regard to loneliness the KYN Fund intends to:

-

Increase the number of opportunities for chronically lonely people in high deprivation areas to build social connections; and

-

Increase the level of social connection for people at risk of or experiencing chronic loneliness.

The survey used the ONS Loneliness measures to assess how often the respondents experience feelings (directly and indirectly) linked to loneliness and being lonely. Further details on the ONS measures for loneliness are described in section 8.1

15% (of n=1,853) of volunteers and beneficiaries who took part in the survey reported feeling lonely often or always. This response to the question “How often do you feel lonely?” is used by government and the sector to define who is experiencing chronic loneliness (Figure 4). This finding would suggest that a larger proportion of the population involved in the funded projects experiences chronic loneliness compared to the general population, whose prevalence of chronic loneliness in 2023/24 was around 7% (of n= 170,255).[footnote 27][footnote 28] Additionally, more than three respondents out of ten (31%) described feeling lonely some of the time in comparison to less than two out of ten (19%) adults in England.

Figure 4 – How frequently participants felt lonely (compared to data from the CLS 2023/24).

| How often do you feel lonely? | KYN Fund baseline survey | CLS 2023/24 |

|---|---|---|

| Never | 13% | 20% |

| Hardly ever | 17% | 30% |

| Occasionally | 20% | 24% |

| Some of the time | 31% | 19% |

| Often/Always | 15% | 7% |

Nearly two out of ten respondents (19% of n=1,846) reported often lacking companionship. 17% (of n=1,833) of respondents reported feeling often left out and 18% (of n=1,831) reported feeling often isolated from others. The responses to these three questions on loneliness can be combined into a total score to give an overarching picture of how respondents generally scored in relation to their perception of being lonely.[footnote 29],[footnote 30] 16% (of n= 1,648)[footnote 31] of respondents reached a score of 8 or 9 (more frequent loneliness), compared to 10% (of n=159,897) of the general population who received a similar score (Figure 5).[footnote 32][footnote 33]

Figure 5 – Participants’ combined loneliness scores (compared to data from the CLS 2023/24).

| Combined loneliness scores | KYN Fund baseline survey | CLS 2023/24 |

|---|---|---|

| 3 or 4 (less frequent loneliness) | 36% | 56% |

| 5, 6 or 7 | 47% | 34% |

| 8 or 9 (more frequent loneliness) | 16% | 10% |

5.2.4 Wellbeing

Beyond the main aims to increase regular volunteering and reduce chronic loneliness, the Fund is also interested in exploring its impact on secondary outcomes such as improving people’s wellbeing. The measures used to assess respondents’ wellbeing are those recommended by the ONS to measure personal wellbeing (also known as ONS4[footnote 34]), and they have the purpose of measuring people’s wellbeing through four dimensions: life satisfaction, feeling things done in life are worthwhile, happiness the previous day, and feeling anxious the previous day.[footnote 35][footnote 36]

-