CyberFirst Evaluation

Published 13 August 2021

Executive summary

Progress towards overall aims

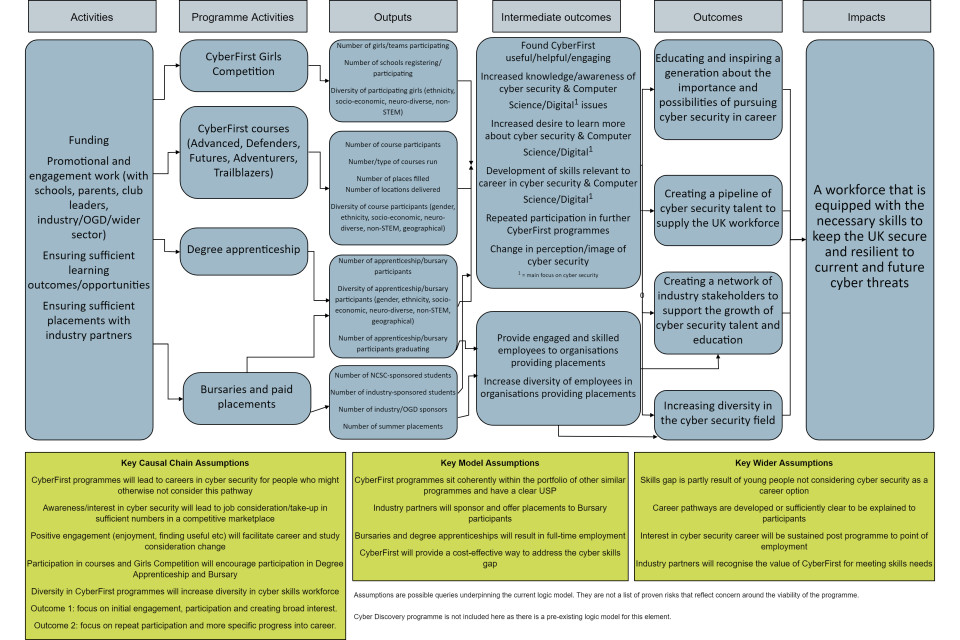

The overall aims of the CyberFirst programme are to create a pipeline of cyber security talent to supply the UK workforce, create a network of industry stakeholders to support the growth of cyber security, and to increase diversity in the cyber security field

-

Management Information (MI) data showed that 70% of Development Days participants had previously taken part in the Girls Competition, and that around a third of bursary students (who receive financial assistance and paid cyber security training to help kick start their career in cyber security) had previously attended a Summer Course. This provides initial evidence of a pipeline within the programme. Qualitative feedback from students suggests that CyberFirst is viewed as complementary to other initiatives and has the potential to reinforce career consideration for students who have taken part in other programmes

-

CyberFirst continues to engage industry supporters. MI data shows that in 2019/20 there were 83 industry members and interviews suggest that supporters value the opportunity to talk to students about recruitment opportunities and give back to the cyber security sector

-

CyberFirst participants tended to have a positive perception of cyber security as a career that was open to different types of people, regardless of ethnicity, gender or background. Interviews with students and club leaders highlighted the perception that initiatives such as the Girls Competition had challenged stereotypes and attracted more female students

Participation

-

Most (76%) of those taking part in the Summer Courses and Development Days had already taken part in cyber courses or events, particularly Cyber Discovery

-

These high levels of previous engagement, together with the high pre-existing levels of interest in cyber security for future study or a potential career, suggest the programme largely functioned as an existing part of a pipeline for the already engaged

-

The Summer Courses engaged an equal spread of male (52%) and female (47%) students according to Management Information. This equal gender split was planned via specific targeting to female participants and admissions quotas

-

Data suggested that both the Summer Courses and Development Days engaged those in less deprived areas considerably more than the more deprived

-

Summer Course participants tended to take part as they hoped to improve their cyber knowledge and skills, and as they thought it would be enjoyable and useful

-

Smaller proportions of Summer Course participants took part for specifically job-related reasons, although levels of interest in cyber security careers was relatively high before participating

CyberFirst perception

-

Those taking part in both Summer Courses and Development Days had very positive perceptions of these activities, being likely to recommend them and wanting to take part in other CyberFirst activities as a result

-

Qualitative feedback suggests a key mechanism was the link between the technical content and the delivery skills of instructors

-

While participants missed the opportunity to engage face-to-face, particularly with peers, there were no suggestions that the move to digital delivery required by COVID-19 had a notable effect on participant experiences

-

Summer Course participants from the oldest Advanced group were more likely to be very interested in a future career involving cyber security than younger groups. Older participants were not any more or less interested than younger participants in careers involving other subjects

CyberFirst outcomes

-

While there was no increased interest in cyber security after taking part in the Summer Courses, this may be because interest was already high before the courses began

-

Following the Summer Courses, students reported an increase in their level of knowledge as well as technical and soft skills. This helped contribute to a significant increase in the proportion stating they were very likely to consider a career in cyber security, compared to before they took part

-

At the post survey, Summer Course participants were more likely to consider applying for a cyber security degree, bursary, or apprenticeship compared to at the pre survey

-

These factors helped contribute to a significant increase between pre and post survey in the proportion of Summer Course participants stating they were very likely to consider a career in cyber security. Participants were also more likely to consider applying for a cyber security degree, bursary, or apprenticeship compared to at the pre survey

-

Students reported that participating in Development Days contributed to high levels of interest in a career in cyber security and an increased desire to learn more, although without additional evidence this perception cannot be substantiated.

Recommendations

-

Recognise that many participants are keeping their options open in terms of future study and career paths, particularly those that are younger and not narrowing down curricular choices. Future initiatives should aim to provide information which participants can use to narrow down their preferred career paths.

-

Continue to grow the CyberFirst community by providing opportunities for industry collaboration and for CyberFirst alumni to remain engaged in the programme.

-

Build on the success of initiatives such as the Girls Competition in order to continue challenging stereotypes and attracting more female students to participate.

-

Consider targeted approaches for wider aspects of diversity, such as neurodiversity and socio-economic diversity. Interviews with students and industry experts identified issues including financial and technological barriers to participation and the relevance of marketing materials

-

Consider the overall scope of CyberFirst and how this fits with other programmes aimed at encouraging young people to consider a career in cyber security

Introduction

In January 2018, Ecorys and the University of Kent were commissioned by SANS Institute (the Cyber Discovery delivery partner) to evaluate the Cyber Discovery programme that was launched in November 2017. Cyber Discovery is part of the wider youth cyber skills government programme, CyberFirst, which consists of the following activities:

-

CyberFirst Courses: short courses to introduce students to the world of cyber security (Trailblazers, Adventurers, Defenders, Futures and Advanced)

-

CyberFirst Girls Competition: supporting girls interested in a career in cyber security through a team event, with each team consisting of 4 female students from Year 8 in England and Wales, Year 9 in Northern Ireland, or S2 in Scotland.

-

CyberFirst Development Days: one day events primarily designed as a follow-on activity for girls who had previously competed in the Girls Competition, but also open to all girls in Years 8 or 9 in England and Wales, Years 9 or 10 in Northern Ireland, or S2 or S3 in Scotland.

-

Cyber Discovery: an online extracurricular programme for those aged 13 to 18. This involves various online stages: Assess, Game and Essentials, that are completed by individuals either in their own time or as part of a club. The highest achievers are then invited to an Elite Camp with the potential to take Global Information Assurance Certification exams

-

Bursary and Degree Apprenticeship: The CyberFirst bursary offers undergraduates £4,000 per year financial assistance and paid cyber security training each summer to help start their career in cyber. A CyberFirst Degree Apprenticeship is a three-year apprenticeship designed for Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), providing university-delivered classroom and lab experience and work-based placements and projects

These activities are supported by an alumni network which was developed in 2020 and aims to continue to grow the CyberFirst community beyond graduation. The goal is to cultivate lifelong relationships with current and future alumni enabling the community to support, grow and give back to both the alumni network and the wider community.

Following initial discussions with NCSC and DCMS, Ecorys were commissioned in 2019 to evaluate the CyberFirst programme during the academic year of 2019-2020. This was to be a light touch evaluation focusing on certain programme activities where this would provide value in assessing the overall programme against the Theory of Change, namely CyberFirst courses and Development Days.

Policy context

The government’s National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review 2015 set aside £1.9 billion to drive forward the UK cyber security agenda. Shortly afterwards, the government published the National Cyber Security Strategy, stating that the UK required a “self-standing skills strategy that builds on existing work to integrate cyber security into the education system”. Among other initiatives, this outlined the need for a schools programme to create specialist cyber security education/training for talented 14-18 year olds, support the accreditation of teachers’ professional development in cyber security, and embed cyber security as an integral part of relevant courses throughout education by 2021.

In July 2018, the Joint Committee on the National Security Strategy (JCNSS) published a report following its inquiry into Cyber Security Skills and the UK’s Critical National Infrastructure. This was critical of progress against the 2016 Strategy document and, while it welcomed efforts to improve cyber security education, expressed concern “that the scale of the government’s efforts on education so far simply does not match the scale of demand”. This was subsequently followed by a call for views on the Initial National Cyber Security Strategy, which included in its mission the aim to “ensure the UK has education and training systems that provide the right building blocks to help identify, train and place new and untapped cyber security talent”.

2021 analysis of the UK skills gap shows that half of businesses (50%) in the UK have a basic technical cyber security skills gap and a third (33%) have a more advanced technical skills gap. The size and nature of any future skills gap in the UK may well be impacted not only by the growing importance of digital literacy and the understanding of cyber security for the workforce, but also by the increasing legal obligations on operators in some sectors to improve cyber security standards and by the potential impact of the EU Exit on the ability to access specialist skills from the EU and beyond.

CyberFirst set-up and development

CyberFirst was launched as a National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) pilot in 2015, forming part of a wider DCMS strategy to increase cyber security awareness and create a pipeline of talent to the UK workforce. It has been scaled up year on year, with increasing industry support. The CyberFirst programme (excluding Cyber Discovery) has been designed, developed and delivered in partnership with the NCSC’s leading tech learning provider QA.

The main objectives of the programme are to educate and inspire a generation about the importance and possibilities of pursuing a cyber security career, create a pipeline of cyber security talent to supply the UK workforce, create a network of industry stakeholders to support the growth of cyber security, and to increase diversity in the cyber security field.

Evaluation

Ecorys were commissioned in 2019 to deliver the evaluation in partnership with University of Kent. The aims of the evaluation are to:

-

Understand the effectiveness of the CyberFirst programme (the “programme”, not including the specific Cyber Discovery programme)

-

Assess the results for participating students, and whether it has been successful in raising awareness, interest and engagement in cyber security careers

-

Identify what has worked well and less well with the programme and if it is on track to achieve its aims and objectives

-

Understand and identify success factors in achieving the outcomes

-

Assess the results on the cyber security industry

-

Develop and conduct an economic analysis to demonstrate value for money

Data collection was based upon the Theory of Change developed in the initial stage of the evaluation (see Appendix One).

Methodology

A mixed methods approach was adopted, incorporating quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis, and a final synthesis of the evidence. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, face-to-face case study visits were replaced with telephone interviews. Details of the exact methodology is contained in the results section for each delivery element.

Report

This report focuses on feedback from key stakeholders to understand the extent that the programme meets the main evaluation objectives at this stage, primarily the claimed effect on participants and industry; what has worked well or less well; and the key factors contributing towards any success. This is largely based around examining the primary outcomes identified in the Theory of Change (see Annex 1). Where the report refers to the ‘programme’ this relates to the wider CyberFirst element rather than the specific Cyber Discovery programme.

The remainder of the report includes separate sections covering Summer Courses; Development Days; industry stakeholders; and conclusions and recommendations

Data limitations

The following data limitations have been identified:

-

Participant survey results may be affected by selection bias due, in part, to the parental consent process required for those aged under 16. This may have resulted in those who were most positive or negative about CyberFirst taking part in the survey

-

The absence of a counterfactual strand to the evaluation (providing comparative data for similar individuals who did not take part in activities) means that results, primarily from the student surveys, should not be taken as proving that positive or negative changes identified in the research were necessarily caused by the programme as opposed to potentially happening anyway

Summer Courses

Summary

Participation

-

Most participants had previously taken part in cyber courses or events (76%), with 42% taking part in Cyber Discovery, suggesting the programme largely functioned as an existing part of a pipeline for the already engaged

-

Management Information data on key diversity measures showed an even split between male (52%) and female (47%) students in line with recruitment strategies and admissions quotas designed to ensure an equal split of male and female participants.

-

Survey data showed students were less likely to live in deprived areas, with only a quarter (26%) living in the five least deprived deciles

-

Those taking part tended to do so as they hoped to improve their cyber knowledge and skills, and as they thought it would be enjoyable and useful

-

Smaller proportions took part for specifically job-related reasons, although levels of interest in cyber security careers was relatively high before participating Programme perception and outcomes

-

Those taking part had very positive perceptions of the programme, being likely to recommend it and wanting to take part in other CyberFirst events

-

Overall levels of interest in cyber security were unchanged between pre and post survey, but there was a significant increase in the proportion stating they were very likely to consider a career in cyber security

-

Students reported increases in knowledge, skills, and the image of cyber security, including knowledge around cyber careers

-

At the post survey participants were more likely to consider applying for a cyber security degree, bursary, or apprenticeship compared to at the pre survey

-

Qualitative feedback suggests a key mechanism was the link between the technical content and the delivery skills of instructors

Approach

This section covers outcomes relating to the Summer Courses, drawing on data from the pre and post surveys and interviews with students.

Evaluation

Summer Course student pre and post survey

A 15-minute online pre and post -survey was developed for Summer Course participants. Although this was potentially open to all, consent from parents or carers was required before participants under the age of 16 could be sent a link to the survey, with this not required of older potential participants. As parental e-mail addresses were not available, the delivery partner e-mailed students asking them to forward a link to an online consent form to their parents, with details being checked by Ecorys. A link to the online survey was sent to all under 16s where parents consented and to those aged 16 or over.

The pre survey was open for completion from 3rd July to 23rd August 2020, with all those who took part and agreed to be recontacted asked to complete the post survey which was open from 23rd July to 7th September 2020. Out of the 1,627 participants, 549 completed the pre survey (a response rate of 34%) and 255 of these pre survey respondents also completed the post survey (a response rate of 23%), providing a good basis for analysis.[footnote 1] Summer Course pre and post survey responses were linked with data weighted to match the gender and course type of participants identified in CyberFirst management data.

While this data provides a valuable insight into changes in time over this period, the absence of longer-term data means there is no evidence as to whether any positive or negative changes are sustained over time.

Interviews

Six telephone interviews were conducted with students who had taken part in a CyberFirst Summer Course in 2020. These were conducted online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The sample was drawn from the 39 students who took part in the pre and post survey and agreed to be contacted by Ecorys for future research. Students were sampled based on their gender, age, participation in other programmes, and any reported change in their level of interest in cyber security as a result of CyberFirst.

Activities and delivery

Summer Courses were planned to be delivered face-to-face as week-long residential courses, but due to COVID-19 they were delivered online in 10-day blocks, consisting of either a morning or an afternoon of learning. There were 54 cohorts, each consisting of 30 students. There were 18 Defenders cohorts (14 to 15 year olds), 16 Futures cohorts (15 to 16 year olds), and 20 Advanced cohorts (16 to 17 year olds). Out of the 1,627 participants, 52% were male, 47% female, and 1% non-binary.

Participant profile

Demographic information was reported in CyberFirst MI data, and shows:

-

White participants accounted for 65% of all participants (compared to 76% of those taking Computer Science GCSE and 78% of those at A Level being white in 2017).

-

A quarter (27%) of participants identified as Black, Asian, or Mixed, and 8% did not provide their ethnic identity.

The Summer Courses pre survey also collected additional demographic information, showing:

-

Most respondents lived in England (83%), with smaller proportions from Scotland (7%), Northern Ireland (4%), and Wales (4%)

-

There was a fairly even split of male (50%) and female (47%) respondents, with 3% not disclosing their gender. This broadly matched the gender balance reported in the Management Information

-

Two-thirds of respondents (32%) were in Year 11 or the devolved equivalent, while roughly a quarter of participants were in each of Year 10 (25%) and Year 13 (27%). There were very small proportions of respondents from Year 9 (1%) and first year of college (2%), and none from Year 12. A further 12% of respondents did not answer the question on school year

-

Three-quarters of respondents attended state schools (75%) and just under a quarter attended private/independent schools (22%)

Management Information is not collected on student postcodes meaning this cannot be used to show deprivation levels among participants. Instead, home postcode information from pre survey respondents is linked to the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI).[footnote 2][footnote 3] Out of 457 students in England taking part in the pre survey, home postcode information was provided and matched for 440 records (96%). This matches postcodes to deciles, meaning that if Summer Course participants are equally spread across deprivation levels there would be 10% of participants in each decile. For these matched postcodes, results showed respondents were less likely to live in the more deprived deciles and more likely to live in the least deprived ones. A fifth of respondents (20%) lived in the least deprived decile, and over a half (54%) in the three least deprived deciles. A quarter of respondents (26%) lived in the five least deprived deciles.

Most of those taking part had, as would be expected, studied science (97% ever, 86% at GCSE level) and maths (97%, 82%), with high proportions also having studied computer science (80%, 69%). Around a third had studied each at AS or A Level, with this suggesting a high level of conversion from studying computer science at GCSE to A Level compared to science or maths. Half of respondents (50%) had studied Design Technology at least at GCSE level and a quarter (25%) had studied ICT.

Involvement in other programmes

When asked to state which courses or activities they had taken part in, three-quarters (76%) stated that they had previously taken part in a cyber or computing science course or event, while for the remaining quarter this was their first cyber course or event. In total, around a half (46%) had taken part in CyberFirst excluding Cyber Discovery, with this increasing to two-thirds (65%) when Cyber Discovery was included.

Within the CyberFirst portfolio, Cyber Discovery was the most popular course (42%), followed by Defenders (21%) and Futures (14%). Only small proportions of respondents had taken part in the Girls’ Competition (6%), Adventurers (4%), or Trailblazers (3%).

Reasons for participation

Respondents were asked at the pre survey why they decided to take part in the Summer Courses from a list of options. Results are split into three separate groups: image (enjoyment and usefulness); perceived obligations; and skills, knowledge, and careers. As outlined below, respondents largely took part as they felt it would be enjoyable or interesting, or to improve their cyber skills, and less due to certain obligations or for directly job-related reasons.

Most respondents took part as they agreed strongly (55%) or agreed (41%) that it would be useful. Enjoyment was also important, with 39% agreeing strongly and 50% agreeing that they took part because they thought it would be enjoyable.

Obligations played a relatively small role in motivating respondents to take part in Summer Courses. Around a quarter either strongly agreed (7%) or agreed (17%) that they took part because their parent, guardian, or carer wanted them to. Just under one in ten participants either strongly agreed (1%) or agreed (8%) that they had taken part because their friends were also participating, while few similarly agreed that they took part for educational obligations, either as teachers wanted it (2% agree strongly, 4% agree) or it was a requirement to do extra-curricular activities (2%, 2%).

The final statements regarding potential motivation for taking part related to skills, knowledge, and career insights, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Reasons for participation (skills, knowledge, career)

| Reason | Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improve cyber security skills | 62% | 35% | 3% | 0% | 0% |

| Knowledge of cyber security issues | 51% | 41% | 7% | 1% | 1% |

| Improve computer science skills | 50% | 42% | 6% | 0% | 1% |

| Increase cyber security careers knowledge | 37% | 46% | 12% | 4% | 0% |

| Help get a job | 18% | 37% | 30% | 10% | 5% |

Improving cyber skills was the most important reason for taking part: 62% strongly agreed and 35% agreed that they had taken part to improve their cyber skills, with 51% strongly agreeing and 41% agreeing that they took part to improve their knowledge of cyber security issues. The desire to improve computer science skills more generally had similar proportions of respondents strongly agreeing (50%) and agreeing (42%).

A lower proportion of respondents took part to increase their knowledge of cyber security careers (37% strongly agreeing, 46% agreeing). Finally, 18% strongly agreed and 37% agreed that they had taken part to help them get a job. Older respondents (those taking part in Futures or Adventurers) were more likely to agree that they had taken part to increase their knowledge of cyber security careers, compared to the younger Defenders group. There was no difference across the three courses in the percentages of respondents taking part to help them get a job. Feedback from interviews suggested that some did specifically value the careers opportunity, reflecting on the value of achieving recognised qualifications, and the value for their career of having advice, input and guidance from instructors.

Future careers interest

At the pre survey stage, respondents were shown a list of subjects and asked to rate their interest in a future career involving each. Around nine out of ten respondents were either very (43%) or fairly interested (48%) in a career in cyber security, illustrating high levels of interest prior to starting the Summer Courses. As noted previously, most participants had taken part in similar programmes, including CyberFirst, with interest in cyber security careers already high by the time they started the Courses.

Computer science had the highest proportion of respondents who were very interested in a related future career (59%), with a further third (33%) fairly interested. Around a third of participants (31%) were very interested in a career involving maths, and a quarter (26%) were very interested in careers involving science. These figures were 18% for ICT and 8% for Design and Technology.

Additional analysis examined whether there were differences in future career interest levels for different subgroups prior to taking part in the Summer Courses. Results showed that males (49%) were significantly more likely than females (37%) to state they were very interested in a future career involving cyber security. This was part of a wider pattern where males were also more likely than females to be very interested in a future career involving computer science (65% compared to 51%) and ICT (21% compared to 14%). By contrast, females (30%) were more likely to be very interested in a future career involving science than males (22%), with no gender difference for maths.

At the pre survey stage, the percentage of participants very interested in a future cyber career was significantly higher in the Advanced group (53%) compared to Futures (41%) and Defenders (36%). Across all other subjects, there were no significant differences across cohorts in the percentage who were very interested. The strengthening of interest in cyber careers with age may be due to older participants having a greater understanding of what cyber careers entail (whereas participants of all ages have a good understanding of what a career in science, ICT, or maths would involve).

Further analysis showed that Advanced participants had previously taken part in more cyber-related programmes than those taking part in Defenders or Futures, which may have explained why they were more interested in cyber careers. However, even when we controlled for the number of courses respondents had previously participated in, Advanced respondents were still more likely to be very interested in a cyber security career than the other two groups. This suggests that overall age by itself is still linked to increased interest in a cyber career regardless of prior programme experience.

Intermediate outcomes

This section covers the intermediate outcomes directly relating to CyberFirst, namely the perception of the programme and the extent that participants wanted to take part in further CyberFirst courses.

Perception of CyberFirst

Around two-thirds of respondents (70%) strongly agreed that they would recommend CyberFirst to friends, with 29% agreeing and 1% neither agreed nor disagreed. There was no significant difference between Defenders, Futures, and Advanced, with each having similarly high levels of recommendation. Most respondents also strongly agreed (58%) or agreed (27%) that they would like to take part in future CyberFirst activities.

Interviews suggested that in general, students enjoyed the Summer Courses and found the content useful and engaging. Students highlighted a range of positive aspects, often reflecting their prior interest and level of engagement in the subject:

- The depth and breadth of content, which was seen as going beyond the curriculum and nurturing an interest in the subject

Extremely intriguing…opens up a realm of possibilities, had to do more research, learnt new things, found it incredibly interesting.

Summer Course student

-

The opportunity to get hands on, practical experience of cyber security skills, such as securing networks, using relevant software, working on virtual machines and setting up servers. Some students felt that they would not be able to gain this experience at school or college

-

The social element, which enabled students to develop teamwork skills and form friendships with like-minded peers. Some students who had taken part in previous years noted that they preferred meeting others face-to-face at residential courses, but online delivery also facilitated relationship building and teamworking

-

The quality of teaching from the qualified instructors:

I would compare them to the best school teachers I’ve ever had but all in a room…they had this way of talking to you, almost hinting that there’s a lot of potential here, interesting things you can be doing and really caught this intrigue in me to find out more and investigate further.

Summer Course student

Various possible changes were suggested, including providing optional modules or sub-categories to allow students to focus on particular topics (e.g., forensics or defence), more creative teamwork activities (e.g., research tasks or presentations) and providing additional information at sign-up stage on content and the required ability level.

Change in knowledge and skills

Respondents were asked at the pre and post survey stages to rate aspects of their knowledge and skills using a scale from zero (very poor) to ten (very good). Mean scores are shown in the following table for those taking part in both surveys.

Table 1: Knowledge and skills rating

| Pre | Post | Change | |

| Knowledge of cyber security issues, for example cracking codes, fixing security flaws etc | 5.7 | 7.4 | 1.7* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Skills in cyber security | 5.4 | 6.9 | 1.5* |

| Skills in computer science in general | 7.0 | 7.5 | 0.5* |

| Base: Total sample | (254) | (254) | (254) |

Significant changes from pre to post stages were seen across the range of knowledge and skills, including knowledge of cyber security (from 5.7 to 7.4), skills in cyber security (5.4 to 6.9), and skills in computer science (7.0 to 7.5).

A strong theme from interviews was that students had gained a broad overview of the sector and developed technical skills which they would not have had the opportunity to learn elsewhere. Specific areas of knowledge included digital certificates, laws relating to cyber security, classifications of hackers, specialist software, encryption and vulnerabilities and how to mitigate them. Some students said they may have eventually developed those skills elsewhere but CyberFirst accelerated the process, which put them in a stronger position when applying for courses or entry level roles.

In addition to practical skills, students also perceived that their soft skills had developed through participation in Summer Courses. This again was connected not just to the content provided but the approach to dissemination. One student highlighted the fact that they felt treated “as adults” and were trusted to learn about these subjects.

They teach us about mature subjects and the need for self-control with what you’re learning, how to be responsible. Trusting us quite a lot, making us feel special. Knowledge that not many people have, something very precious. It was brilliant.

Summer Course student

Interviews suggested that students who enjoyed the course were likely to pursue further learning, either through formal qualifications or research in their own time. Some noted that the instructors encouraged them to experiment further at home, again linking to the perception that students were trusted to understand ethical boundaries.

Absolutely brilliant, the way it provokes a proper intrigue in the subject, specifically the tutors. Whenever they teach something, they’re always subtly hinting at more you can discover…they don’t need to set out a big list of rules, you understand what is and isn’t allowed.

Summer Course student

Increased interest in cyber security and computer science

Respondents were asked at the pre and post survey stages to rate their interest in cyber security and computer science in general, using a scale from zero (very poor) to ten (very good). Results showed that there was no statistically significant increase in interest in either cyber security (8.1 and 8.3) or computer science (8.6 at both stages), albeit that high levels of interest in both were maintained.

At the post survey, respondents were shown a list of factors which may affect interest in cyber security. They were asked to rate how much each factor had affected their interest in cyber security using a scale from 0-10, where 0 was large negative ‘impact’,[footnote 4] 5 was no ‘impact’, and 10 was large positive ‘impact’. The following figure shows results grouped into three different categories, those giving a score of nine or ten, six to eight, and five or below.

Figure 2: Factors affecting interest in cyber security

| Factor | 9-10 | 6-8 | 0-5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CyberFirst | 64% | 32% | 4% |

| Other similar courses/progs | 25% | 44% | 31% |

| Online resources | 22% | 44% | 31% |

| Academic/teachers | 16% | 57% | 27% |

| Parents | 16% | 52% | 32% |

| Open days/careers fairs | 9% | 42% | 49% |

| Social media | 7% | 46% | 46% |

| Friends | 7% | 42% | 52% |

| Regular media/news | 6% | 46% | 48% |

| Careers advice | 6% | 43% | 51% |

CyberFirst was reported as being the most important factor affecting interest in cyber security compared to other options provided, with nearly two-thirds (64%) rating it as nine or ten, and a third (32%) as six to eight. Given there was not a statistically significant pre to post change in interest in cyber security, this suggests either that this reflects a generally positive disposition towards the programme (a “halo” effect when answering this question) and/or that CyberFirst as a whole is felt to have positively affected their interest.

Other courses or programmes (25% as nine or ten, 44% as six to eight) and online resources (22%, 58%) were also seen to be key factors, followed by personal influence from teachers (16%, 57%) or parents (16%, 52%). Perceived positive ‘impact’ was lower for open days or careers fairs, social media, friends, regular media or news, and careers advice. For each of these factors, around half of respondents said they had a net positive ‘impact’, with most of the remainder saying they had less ‘impact’.

Consideration of future education

At the pre- and post survey, respondents were shown a list of cyber security education and training opportunities and asked to indicate which they had heard of, and to what extent they were considering applying for them or had already applied. Figure 3 shows the percentage of respondents at each survey who were slightly or strongly considering applying for each option.

Figure 3: Consideration of education options (summer courses)

| Education option | Pre | Post |

|---|---|---|

| Cyber security degree | 53% | 65% |

| Cyber security bursary | 27% | 61% |

| Cyber security apprenticeship | 38% | 58% |

| A recognised cyber security certificate | 34% | 51% |

| EPQ in Cyber Security | 19% | 20% |

| BTEC in Cyber Security | 11% | 13% |

| NPA in Cyber Security | 4% | 9% |

Overall results showed significant increases in consideration for most options. At the pre survey, half of respondents (53%) were strongly or slightly considering applying for a cyber security degree, with a significant increase to two-thirds (65%) at the post survey. The percentage of respondents strongly or slightly considering a cyber security bursary also changed significantly, more than doubling between the pre (27%) and post survey (61%). There were also significant increases in the percentage considering applying for cyber security apprenticeships (38% to 58%) and recognised certificates (34% to 51%). Significant change was also seen for the proportion considering a NPA in Cyber Security (4% to 9%) but not for the EPQ (19% to 20%) or BTEC (11% to 13%).

Longer-term outcomes

Improved image of careers in cyber security

At the pre and post survey, respondents were asked to rate to what extent they agreed or disagreed with a range of statements around cyber security careers, on a five-point scale where 1 was strongly disagree and 5 was strongly agree.

Table 2: Change in image of cyber security careers – general statements

| Pre | Post | Change | |

| Positive statements: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pay particularly good salaries | 3.7 | 3.9 | 0.2* |

| Make a useful contribution to society | 4.6 | 4.7 | 0.1 |

| Negative statements: | |||

| Require high grades | 3.6 | 3.2 | -0.4* |

| Are difficult to get into | 3.3 | 2.9 | -0.4* |

| Are boring | 1.8 | 1.7 | -0.1* |

| Base: Total sample | (254) | (254) | (254) |

Results showed significant changes between pre and post surveys in most perceptions around cyber security, albeit with changes being small in actual mean score, suggesting that while results are significant, they may not be particularly meaningful. This was seen in the change in those feeling they paid particularly good salaries (3.7 to 3.9), require high grades (3.6 to 3.2), are difficult to get into (3.3 to 2.9) and boring (1.8 to 1.7). No change was seen in the proportion stating they made a useful contribution to society (4.6 to 4.7).

Respondents were also shown questions regarding different aspects of diversity in relation to cyber security careers, at both pre and post surveys.

Table 3: Change in image of cyber security careers – diversity statements

| Positive statements: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Are open to anyone regardless of background | 4.1 | 4.2 | 0.1 |

| Are suitable for someone like me | 4.0 | 4.1 | 0.1 |

| Negative statements: | |||

| Are only for people who are good at technical things | 3.0 | 2.8 | -0.2* |

| Are more suited to men than women | 1.6 | 1.6 | 0.0 |

| Base: Total sample | (254) | (254) | (254) |

At the pre survey, there was already a high level of agreement with the view that cyber security is open to different people regardless of background, with little change at the post survey (4.1 to 4.2). Respondents were less likely to feel that a cyber security career was only for people who were good at technical things (3.0 to 2.8) with no change in perception regarding whether they were suitable for someone like them (4.0 to 4.1) or more suited to men than women (1.6 at both stages).

Qualitative research suggested that while there was no change in the proportion feeling cyber security careers were more suited to men than women, there was a perception that the programme was doing a good job of addressing the gender gap through the Girls Competition and including females in marketing materials. One female student described how she felt the programme had successfully challenged stereotypes.

I always felt the unconscious bias, “you’re going to struggle if you’re female”…I’m so much more interested and confident. I’ve met women in cyber, I’m inspired by them. I wouldn’t have if it wasn’t for CyberFirst. I feel more included.

Summer Course student

She added that in her view, it would be beneficial for CyberFirst students to be encouraged to discuss stereotypes, perhaps through resources for PSHE or pastoral lessons. This was felt to potentially help embed ideas about equality from when students first start learning about cyber security.

Other students talked about diversity in terms of skill level and prior experience of cyber security. It was suggested that information about recommended prior knowledge could manage expectations and allow students to read up in advance:

You wouldn’t want someone on the course without the prior knowledge and feeling nervous. It might turn them off cyber security if they’re intimidated by others on the course who can answer questions. It’s not that that person is bad, it’s just simply they haven’t been taught or practiced as much as the others.

Summer Course student

Another student described how initiatives such as CyberFirst provide a safe, controlled environment for students with “active minds” to try new things and learn to apply their knowledge and skills. By channelling their interest into something productive, the programme has the potential to redirect students into industry. CyberFirst was felt to be effective at doing this, as students have input from instructors who provided clear guidelines and acted as role models.

Another theme was that it was important to consider neurodiversity. Cyber Discovery was felt to be well suited to these learning style as tasks can be completed in their own time in an individual setting. It was felt that other CyberFirst activities could look into the potential of more open-ended participation or other approaches to engaging neurodiverse participants.

Others expressed concerns that too much emphasis on specific backgrounds could inadvertently exclude others. In their view, campaigns should be as open as possible, although this was expressed as a general consideration rather than specific feedback on CyberFirst marketing campaigns.

Change in interest in future careers

At the pre and post survey, respondents were asked how interested they were in a career involving different subjects. For each subject, they could select one of four levels from not at all interested, not very interested, fairly interested, or very interested.

Figure 4: Interest in careers involving each subject

| Subject | Fairly interested | Very interested |

|---|---|---|

| Computer science (pre-CyberFirst Programme) | 32% | 61% |

| Computer science (post-CyberFirst Programme | 27% | 67% |

| Cyber security (pre-CyberFirst Programme) | 49% | 43% |

| Cyber security (post-CyberFirst Programme) | 38% | 54% |

| Maths (pre-CyberFirst Programme) | 43% | 33% |

| Maths (post-CyberFirst Programme) | 40% | 35% |

| ICT (pre-CyberFirst Programme) | 42% | 16% |

| ICT (post-CyberFirst Programme) | 46% | 23%* |

| Science (pre-CyberFirst Programme) | 40% | 27% |

| Science (post-CyberFirst Programme) | 38% | 29% |

Significant increases were seen in the proportion who were very interested in cyber security as a career, from 43% to 54%, with a similarly significant increase in those very interested in a career involving ICT (16% to 23%) but not computer science (61% and 67%). The general level of interest across subjects suggests that most respondents were still interested in careers involving a broad range of subjects. Interviews showed that for some students, it was too early for them to say exactly what job role they would pursue, and others noted that they had preferences but wished to keep their options open.

Evidence shows that a male computing graduate is expected to earn £10,995 more than the average male graduate over a ten-year period, while a female will earn £3,774 more. This shows the possible monetary result of CyberFirst students taking up a career in cyber security but should not be linked to the earlier data on career consideration (namely assuming an increase in career consideration suggests a positive financial result). This is not least due to the length of time until survey respondents actually move into careers, the changing nature of the cyber job market, and the lack of counterfactual information to assess what may have happened had respondents not taken part in the programme.

In addition, change in career consideration is one element of the Theory of Change, with potential other financial benefits through broader upskilling leading to increased safety from cyber threats in general and/or skills gained leading to improved financial benefits in other, non-cyber careers.

Knowledge and understanding of cyber security career

At pre and post surveys, respondents were asked to rate their knowledge about careers in cyber security on a ten-point scale, where 0 was very poor, 5 was average, and 10 was excellent. Results showed a significant increase (from 5.8 at the pre survey to 7.4 at the post) suggesting that underlying knowledge around cyber careers was felt to have improved.

Responses to a separate question showed respondents generally felt they had enough knowledge about cyber security to know if it was a career option for them. When asked if they didn’t have enough information, most strongly disagreed (14%) or disagreed (51%). In total, 4% strongly agreed and 12% agreed that they did not have enough knowledge, suggesting that increased information provision may be beneficial for a small minority of participants, albeit that those with less knowledge at this stage may be those who are less interested in cyber security as a real career option.

Knowledge of cyber career requirements

Respondents were shown a further set of statements at the post survey which related to their knowledge of the different requirements for achieving a career in cyber security, with these generally showing that most respondents were confident about cyber career requirements. They generally knew what they should study to pursue a career in cyber security (28% strongly agreed, 57% agreed) and where to go to get information (26% strongly agreed, 59% agreed). A majority also said they knew what skills (23% strongly agreed, 64% agreed) and steps (19% strongly agreed, 63% agreed) were required to pursue a cyber security career.

Respondents linked these changes to CyberFirst. Nearly all respondents strongly agreed (41%) or agreed (54%) that CyberFirst had helped them to develop skills they needed to pursue a cyber security career. A third of respondents (35%) strongly agreed and a further 54% agreed that CyberFirst had helped them know what steps they needed to take in order to pursue a cyber career. This was backed up by almost all participants (95%) stating that CyberFirst had provided them with information about cyber security as a career.

The other potential sources of information on cyber careers were online resources, which more than two-thirds (69%) had used to find information. Over half of respondents had received information from schools/teachers (59%), and slightly under half from parents or family (45%). Other similar courses or programmes were also a source of information on cyber careers for 41% of respondents. Over a quarter (28%) had received information from friends.

Traditional sources of careers information were a source for a smaller proportion, with 36% having received information from careers advice services and 36% from open days or careers fairs. Social media (45%) was twice as popular as regular media/news (22%) as a source.

The role of CyberFirst in career consideration

A main theme was that students felt they would probably have pursued computer science if they hadn’t taken part in the programme, but CyberFirst nurtured a specific interest in cyber security which they were unlikely to develop elsewhere, particularly given the fact some felt school careers staff struggled to provide detailed information about cyber security careers and deal with misconceptions about roles in the sector. Others suggested that they may have still had a general interest in cyber security but would not necessarily have viewed it as a career option.

When I started it [the Summer Course], I thought it was a very interesting thing to do on the side that I’m not quite sure about. By the second day I am seriously considering this as a career now.

Summer Course student

Another theme was the value of meeting course instructors who had extensive industry experience and were able to enthuse students about roles in the sector.

The thing that clinched it for me was the tutors. If there’s a whole company made up of people like that, that’s something I’d love to work with or for… they are themselves the advert as to how fun and interesting the career could be.

Summer Course student

Some students had taken part in other related initiatives and found it difficult to attribute their increase in interest to a specific programme. For these students, participation in Cyber Discovery had raised awareness of cyber security and subsequent participation in CyberFirst helped them to gain further skills and knowledge and reinforced its viability as a career option.

Cyber Discovery is definitely the number one thing to thank, then CyberFirst for really concreting that interest and the desire to do it as a career.

Summer Course student

Some students gave suggestions on additional support that would be helpful in pursuing a role in cyber security, particularly once they have left school or college. For example, a webpage containing relevant information for those who have completed a CyberFirst course, or information on apprenticeships and the variety of available roles.

Girls Development Days

Summary

-

Most students took part in a Development Day because they thought it would be enjoyable, useful and an opportunity to develop computer science or cyber security skills

-

A large proportion of those taking part did not identify as white (54%) compared to 24% taking Computer Science GCSE

-

Most students had previously taken part in a cyber security course or event, most commonly a CyberFirst course (more so than for Summer Course participants)

-

Students had a positive perception of the Days, with most (96%) rating their experience as excellent or good, two-thirds (65%) strongly agreeing that they would recommend it, and 71% strongly agreeing they would like to take part in future CyberFirst courses

-

As with the Summer Courses, those who took part generally had high levels of interest in a career in cyber security and felt that the Days had contributed towards this and an increased desire to learn more about cyber security

-

However, the high levels of interest in other STEM subjects and related careers and the absence of additional evidence means that the perception that Development Days led to increased interest cannot currently be substantiated

Approach

This section covers outcomes relating to the Girls Development Days, drawing on data from the online survey. Subsections present information on the reasons for participation, involvement in other programmes, knowledge and skills, interest in further study and longer-term outcomes relating to perceptions of cyber security careers.

Evaluation

Girls Development Days student post survey

A 10-minute online survey was developed for those who took part in the Girls Development Day sessions. Since all participants were under 16, consent from parents or carers was required before any participants could be sent a link to the survey. As parental e-mail addresses were not available, this required the delivery partner e-mailing students and asking them to forward a link to an online consent form to their parents, with details being checked by Ecorys. A link to the online survey was sent to all under 16s where parental consent was provided, after they had completed the Development Day.

The survey was open for completion from 15th October to 12th November 2020. All parents were asked to provide consent for their child to take part in the survey, and 72% agreed. Overall, 83 participants completed the Development Days survey out of a total of 506 participants, a positive response rate of 16%.[footnote 5]

Activities and delivery

Development Days were initially planned as face-to-face events but were delivered online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Originally participation was only for girls who had previously completed in the Girls’ Competition, but registration was opened more widely so that any girl in Year 9 or 10 (or devolved equivalents) could attend. Five Development Days were delivered across two half-days in October.

Participant profile

Demographic information was collected on all those who completed the Development Day survey. This showed:

-

Almost half (46%) identified as white (compared to 76% of those taking Computer Science GCSE and 78% of those at A Level being white in 2017)

-

Around a third stating they were Asian or British Asian (31%). A further 7% identified as from mixed or multiple ethnic groups, and 5% as Black / African / Caribbean / Black British

-

Almost all those taking part lived in England (90%), with small minorities from Wales (4%), Northern Ireland (4%) and Scotland (2%)

-

Nearly two-thirds (64%) were in Year 9 or the equivalent, with 12% in in Year 8 or equivalent and 18% in Year 10 or equivalent (21%). The remaining 6% of respondents did not report their school year.

-

Respondents were equally likely to be from a state school (39%) as from a private or independent school (36%). Just over a tenth said they were from an “other” type of school (12%) or did not answer the question (13%)

Management Information is not collected on student postcodes meaning this cannot be used to show deprivation levels among participants. As a result, home postcode information from pre survey respondents is linked to the Income Deprivation Affecting Children Index (IDACI).[footnote 2][footnote 3] Out of 75 students in England taking part in the pre survey, home postcode information was provided and matched for 73 records (97%). Results showed respondents were less likely to live in the more deprived deciles and more likely to live in the least deprived ones, with 28% living in the least deprived decile, and over half (57%) in the three least deprived deciles. These were similar to the proportions seen in the Summer Courses sample.

Reasons for participation

According to MI data, over half of attendees (52%) had heard about the Development Day through school or teachers. A further 14% had heard about it through family or parents, and 14% through the Girls Competition.

Survey respondents were asked why they decided to take part in the Development Days, with results shown below in terms of image (enjoyment and usefulness); perceived obligations; and skills, knowledge and careers.

Most respondents took part because they either strongly agreed or agreed that they felt the Development Day would be enjoyable (55% and 39% respectively) and as it would be useful (46%, 48%). These were relatively highly endorsed compared to most other statements, suggesting these were particularly motivating factors. As would be expected, additional analysis suggested that there was a relationship between enjoyment and usefulness, with those who agreed strongly that they took part as they thought it would be enjoyable being more likely to agree strongly it would be useful than those who did not (71% compared to 42%).

Parents or carers did have an effect for some, with around a quarter either strongly agreeing (10%) or agreeing (16%) that they participated as their parents wanted them to. Smaller proportions said likewise in relation to their friends taking part (13%, 4%), as teachers wanted them to (4%, 5%) or as a required extra-curricular activity (1%, 2%). While relatively small proportions felt they were taking part due to any individual of these sources of influence, although 40% agreed strongly or agreed with at least one (29% for parents, friends and teachers only) suggesting that there is a cumulative effect from these sources.

The final set of statements related to participants taking part with the aim of increasing skills and knowledge of cyber security and computer science, or to help them get a job. These showed that developing specific skills was a particularly important reason for taking part:

-

Most respondents agreeing strongly that they were taking part to improve cyber security skills (58%, with 36% agreeing)

-

Similarly high proportions (52%, 39%) were taking part to improve computer science skills (52%, 39%), improving knowledge of cyber security issues (46%, 42%) or careers (43%, 40%)

-

A smaller proportion agreed strongly (14%) or agreed (36%) that they were taking part specifically to help them get a job

The higher endorsement for skills and knowledge as opposed to careers is largely expected. Firstly, regardless of the subject or programme, people are more likely to be interested in developing skills generally than for more specific career reasons. Secondly, as participants are aged 14 or 15 there are likely to be many that have not made clear decisions yet about career options.

Involvement in other programmes

All respondents were shown a list of different courses and activities and asked to state which ones they had previously taken part in. Respondents were allowed to select multiple options, including those relating to broad computer science as well as cyber security. Most of those taking part in the Development Days survey had taken part in a listed course or event previously (92%), with the proportion having taken CyberFirst courses (80) being higher than those who took part in other courses (48%). These were higher proportions than for the Summer Courses seen previously.

The most common individual courses were Cyber Discovery (40%) or the CyberFirst Girls competition (54%). There was a broad range of non-CyberFirst courses that participants had taken part in, with the Matrix Challenge being the only one endorsed by more than a tenth of participants (11%). While this suggests that both Cyber Discovery and the Girls Competition have resulted in equal numbers progressing to the Development Days, the considerably larger scale of Cyber Discovery means that a smaller proportion of those taking part will go on to take part in the Girls’ Development Days. MI data found that over a third of participants (39%) had taken part in the Girls Competition 2020, and just under a third (31%) in the Girls Competition 2019. Since girls are only able to take part in a Girls Competition once (in Year 8), this means that 70% of Development Days participants have previously taken part in the Girls Competition.

Intermediate outcomes

This section covers the intermediate outcomes directly relating to CyberFirst, namely the perception of the programme and the extent that participants wanted to take part in further CyberFirst courses.

Perception of Development Days

Respondents generally had a positive perception of the Development Days, as shown by:

-

Around two-thirds (65%) strongly agreeing that they would recommend the Development Days to friends who were interested in cyber security, and most agreeing strongly (71%) or agreeing (20%) that they would like to take part in future CyberFirst activities. Comparative figures for the Summer Courses were 70% and 58% respectively, indicating similar positive perceptions

-

Two-thirds (66%) of those taking part said the Days had made them much more likely to take part in further CyberFirst activities with a further 20% saying it made them more likely

-

Responses from a short survey conducted by CyberFirst at the end of the Development Day showed 69% rated the Day as excellent and 27% as good

Increased interest in subjects

Those taking part in the Development Day survey generally had high levels of interest in both computer science (75% rating between 8 and 10) and cyber security (70%), with further analysis showing that, as would be expected, the vast majority (82%) of those who were very interested in cyber security were also very interested in computer science.

As would be expected, the majority (82%) of those who were very interested in cyber security were also very interested in computer science (compared to 26% of those who were not interested in cyber security being very interested in computer science).

Respondents were also shown a list of factors that may affect interest in cyber security and asked to state the extent that each affected their interest in cyber security on a scale from 0 to 10. For reporting purposes, a score of 9-10 is defined as high positive ‘impact’, 6-8 as medium positive ‘impact’, and 0-5 as no impact to negative ‘impact’.

Figure 5: Factors affecting interest in cyber security

| Factor | 9-10 | 6-8 | 0-5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development day | 57% | 34% | 10% |

| Other similar courses/progs | 41% | 34% | 25% |

| Parents | 27% | 41% | 33% |

| Academic/teachers | 25% | 53% | 22% |

| Online resources | 18% | 57% | 25% |

| Open days/careers fairs | 18% | 39% | 43% |

| Careers advice | 17% | 39% | 44% |

| Friends | 17% | 28% | 55% |

| Social media | 10% | 30% | 60% |

| Regular media/news | 5% | 46% | 49% |

Results showed that respondents felt the Development Days were a key factor affecting their interest in cyber security, albeit not significantly more so than other similar programmes. Over half (57%) of all respondents felt that the Development Days had a high positive influence on their interest in cyber security, with most of the remainder (33%) rating is as a medium positive ‘impact’. Other similar programmes were endorsed at similar levels (42%, 33% respectively).

Around a fifth to a quarter gave a high positive ‘impact’ for each of the other options, albeit that the proportion reporting less of an influence was higher for friends (55%) than other contacts such as teachers (21%) and parents (33%). The media, whether social (10%) or regular (5%), was not reported to have been a considerable factor by many respondents.

Image of careers

A range of different statements about cyber security careers were included in the survey, with respondents asked to state the extent that they agreed or disagreed with each. These statements are shown in two separate groups, firstly those relating to the extent that cyber security careers were suitable or open to different types of individual.

Table 4: Perceptions on careers on cyber security

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

| Are open to everyone regardless of their ethnicity | 54% | 27% | 16% | 2% | 1% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Are open to anyone regardless of background | 42% | 37% | 14% | 5% | 1% |

| Are suitable for someone like me | 36% | 41% | 19% | 2% | 1% |

| Are more suited to men than women | 1% | 2% | 14% | 12% | 70% |

| Are only for people who are good at technical things | 0% | 14% | 34% | 39% | 13% |

Those taking part tended to have a generally positive perception of cyber security as a career that was open to different types of people, regardless of ethnicity (81% agreeing at all) or background (79%).

Most strongly disagreed (70%) that cyber security careers were more suited to men than women, although almost a fifth (17%) agreed or neither agreed nor disagreed. While small proportions agreed that they were not only for people who were good at technical things (0% strongly agreed, 14%) agreed, about a third (34%) neither agreed nor disagreed, with most of the remainder disagreeing (39%) rather than agreeing strongly (13%).

Table 5: Perceptions on cyber security career suitability

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

| Make a useful contribution to society | 63% | 34% | 4% | 0% | 0% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pay particularly good salaries | 19% | 43% | 33% | 4% | 1% |

| Require high grades | 11% | 41% | 42% | 5% | 1% |

| Are not well promoted | 6% | 37% | 40% | 16% | 1% |

| Are difficult to get into | 1% | 29% | 45% | 23% | 2% |

| Are boring | 0% | 1% | 13% | 37% | 48% |

Respondents had a generally positive view of cyber security as a career, with almost all either agreeing strongly (63%) or agreeing (34%) that it made a useful contribution to society. More than half agreed at all that it paid particularly good salaries (19% strongly, 43% agreeing) and very small proportions felt it was boring (0%, 1%).

Views were split as to whether cyber security careers were well promoted, with just under half thinking they were not well promoted (6% strongly agreeing and 37% agreeing they were not well promoted) and around a fifth thinking they were well promoted (1% strongly disagreeing, 16% disagreeing). Almost a third felt that cyber security careers were difficult to get into (1% strongly agreeing, 29% agreeing), with similar proportions disagreeing (2% strongly, 23% disagreeing).

Increased desire to learn more about subjects

Respondents were asked how much they were interested in studying certain subjects.

Figure 6: Interest in studying in the future

| Subject | Very interested | Fairly interested | Not very interested | Not at all interested |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyber security | 61% | 31% | 6% | 1% |

| Computer science | 59% | 35% | 4% | 2% |

| Science | 54% | 29% | 14% | 2% |

| Maths | 54% | 29% | 13% | 4% |

| ICT | 47% | 41% | 11% | 1% |

Results showed over half (61%) of those taking part were very interested in studying cyber security, with most of the remainder (31%) being fairly interested. Similar levels were seen for other STEM subjects, with those who were very interested ranging from 47% for ICT to 59% for Computer Science. Over a quarter (28%) were very interested in Design and Technology. This suggests a high level of interest in cyber security although as one of several possible subjects to study in the future.

The evidence that participants are generally interested in careers involving many subjects links to the previous data showing they are generally interested in studying many subjects. These findings show that CyberFirst participants want to keep future options open and that high interest in future cyber study or careers is important but does not guarantee that participants will actually go on to pursue cyber given their similarly high interest in other options.

Participants reported that the Development Day had made them more likely to study cyber security, with around half (53%) saying it made them much more likely, and a further 31% it made them more likely. This may largely reflect the overall positive engagement with the Day as opposed to notable change in subject consideration. As noted in Figure 6, levels of interest in cyber security are similar to those for other subjects. As a result, if CyberFirst involvement has increased consideration of cyber security as a subject to the extent reported, this would suggest either that it has increased consideration for other STEM subjects and/or that consideration for cyber security was originally lower than for these other subjects.

Development of relevant skills

Survey respondents were asked to state their skills, knowledge and interest in cyber security and computer science, as outlined in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Skills and knowledge

| Skills and knowledge | 9-10 | 6-8 | 0-5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge about cyber security careers | 54% | 37% | 8% |

| Skills in computer science | 14% | 70% | 16% |

| Skills in cyber security | 13% | 63% | 24% |

| Knowledge of cyber security issues | 13% | 59% | 28% |

Results suggested that respondents were generally relatively positive about their level of skills and knowledge in computer science and cyber security following the Development Days. There were no notable differences across statements, with just over a tenth giving a score of nine or ten for each and between a half and three-quarters a score of between six and eight.

Longer-term outcomes

While measuring longer-term outcomes was not within the remit of this evaluation, a set of questions was included to assess the initial perceptions of cyber security as a future career or education option. As part of this, an initial question asked respondents their level of interest in future careers in certain subjects, which showed:

-

Nearly half (46%) of respondents stated they were very interested in a future career in cyber security, compared to 55% for computer science and 46% for science .

-

Over a third were very interested in Maths (35%) and ICT (37%) with a fifth (20%) interested in Design and Technology.

-

The mean average number of subjects that respondents were very interested in was 2.4, showing that being very interested in a future career in one subject does not preclude a similar level of interest in a different career.

Survey participants were asked the extent that they felt they were more or less likely to take up further learning or a career in cyber security as a result of the Development Day. This showed that respondents felt the Days had a positive effect on their likelihood to take part in other cyber security training (60% much more likely, 25% more likely) and a future career (46%, 34%). As with interest in studying subjects, this may largely reflect overall satisfaction with the Development Days.

Industry stakeholders

Summary

-

Most industry experts said they supported CyberFirst because it was an effective recruitment channel

-

A common theme was the high calibre of CyberFirst students compared to candidates from traditional recruitment channels. Industry experts highlighted students’ passion for cyber security as well as technical expertise

-

Industry experts were generally positive about CyberFirst in relation to other programmes, although concerns were expressed about the cost of involvement and perceived emphasis on government roles

-

CyberFirst is seen to be making good progress in terms of increasing diversity in the sector, notably in encouraging female students to consider a career in cyber and potentially less so in socio-economic diversity

-

Suggested future developments included networks of industry stakeholders and alumni

Approach

This section provides an overview of the outcomes for industry experts, including reasons for participation, involvement in other programmes and perceptions of the programme’s contribution to addressing the skills gap. This data is used to illustrate the range of views held by industry experts and should not be interpreted as implying the extent that any views are held among the group.

Evaluation

Industry stakeholder interviews

A sample of industry stakeholders was provided by NCSC. There was an initial target of 10 industry interviews, and 11 were completed in total (one paired interview). Interviews were conducted throughout June 2020, via telephone or video call. According to the CyberFirst 2019-20 Annual Report, there are over 130 industry, government and academic members of the CyberFirst community.

Types of involvement

Interviews revealed that industry experts had participated in a range of activities including developing a certification programme for CyberFirst Schools in Wales; sitting on advisory boards and certification panels; providing content for courses; running workshops; and challenge design for the Girls Competition. Others had more direct involvement with students, for example hosting and attending events, such as the Girls Competition and CyberFirst courses; running summer placements and hosting bursary students; and mentoring activities for schools involved in the Girls Competition.

Reasons for participation

Industry experts had a range of reasons for supporting CyberFirst, predominantly focused on recruitment opportunities. Some noted that it was easier to get ‘buy in’ from senior management for support relating to older students, such as the bursary scheme and summer placements, as this was seen to have a more immediate return on investment. Involvement was often seen as a corporate social responsibility opportunity and “doing the right thing” by giving back to the sector, but also as highly rewarding and motivated them as individuals to continue their involvement in the programme.

It’s great. You do an activity, you can see how excited they get at solving puzzles, thinking about roles in industry. That sells itself. I definitely recommend it.

Industry expert

Others were involved to raise awareness of the company, as it was in the company’s strategic interest as a security service seller to have high performing individuals in the sector know their products and services. Another was that colleagues had seen the benefits for the organisation and there was therefore wider interest in supporting it. They commented that mentoring and teaching opportunities were beneficial for staff upskilling as they offered employees the chance to try something new.

Involvement in other programmes

Some industry experts had also supported Cyber Security Challenge UK (CSC) and were able to reflect on how the programmes compared. They tended to be positive about CyberFirst in relation to other programmes, identifying four key perceived strengths:

-

CyberFirst is seen to be focused on the pipeline and therefore more effective in terms of recruitment. One industry expert reported that they had been involved with CSC for three years but had struggled to convert interest into recruitment. In two years of supporting CyberFirst, they had made job offers to 27 out of 28 placement students. Another noted that CSC attracted many people who were already in the industry

-

The strong, recognised brand is easy to ‘sell’ to students and parents. In addition, as it is a government backed initiative, rather than industry funded, industry stakeholders have trust in the programme

-

The range of CyberFirst community members offers students the opportunity to find roles in government, academia or industry. One industry expert felt that CyberFirst could do more to raise awareness of opportunities outside of government, feeling that students had a “tunnel view” as a result, but that they were able to “open their eyes a bit” through being involved

-

The breadth of the programme, encompassing summer placements and bursaries as well as skills development opportunities. One industry expert noted that placement students are offered a valuable opportunity to see the reality of cyber security, motivating students and resulting in better quality candidates

Where engagement worked, businesses felt they were able to access better candidates who didn’t need to be put through assessment days, thereby being cost-effective.

Although feedback was generally positive, the main query was around the costs of supporting CyberFirst compared to CSC. One industry expert remarked on the minimal costs for hosting a CSC event in comparison to the original costs quoted for a CyberFirst event. Similar concerns were expressed over the cost of bursaries as they were seen to be a considerable investment, with a risk the students may drop out or get a different job. For some, CSC was also considered to be a bigger, better publicised event which attracted more media coverage than CyberFirst. Others noted that CSC brought together large audiences from across Europe, not just students.

Intermediate outcomes

The following subsections relate to the relevant intermediate outcomes outlined in the Theory of Change: to provide engaged and skills employees to organisations providing placements. This is followed by a brief subsection outlining additional outcomes which were identified in interview feedback from industry experts.

Engaged and skilled employees

Industry experts who had hosted placement students highlighted the high calibre of the students. They noted high levels of technical competence and passion about cyber security compared to candidates who had come through traditional recruitment channels.

One industry expert felt that this was because CyberFirst successfully identified talented students with existing skills and further gave them the additional skills and knowledge to pursue a relevant career. They noted that graduates who have taken part in CyberFirst were particularly strong candidates because they had a greater understanding of the sector and had been able to develop specialisms.

They find these amazing students; they train them up to an absolutely amazing level. It makes it easier for industry to be able to access these students and hopefully recruit them into our organisations.

Industry expert

A common theme was that CyberFirst streamlined recruitment processes by identifying the best candidates and ensuring they were trained to a high standard, reducing required work from their Human Resource departments. A particular benefit for those delivering public sector contracts was that all candidates had security clearance.