Impact Assessment of Support for Mortgage Interest Loans

Published 6 May 2025

DWP research report no.1094

A report of research carried out by IFF Research Ltd on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2025.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit the National Archives.

or write to:

The Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

or email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

This document/publication is also available on our website at: Research at DWP

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published May 2025.

ISBN: 978-1-7865-9834-9

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Voluntary statement of compliance with the Code of Practice for Statistics

The Code of Practice for Statistics (the Code) is built around 3 main concepts, or pillars, trustworthiness, quality and value:

- trustworthiness – is about having confidence in the people and organisations that publish statistics

- quality – is about using data and methods that produce assured statistics

- value – is about publishing statistics that support society’s needs for information

The following explains how we have applied the pillars of the Code in a proportionate way.

Trustworthiness

This research was carried out by IFF Research on behalf of DWP (Department for Work and Pensions). IFF are certified to ISO/IEC 27001:2013 standards for information management and security and are registered with the Data Protection Commission. IFF also comply with industry standards; they are a member of the Market Research Society (MRS), and ESOMAR (World Association of Marketing Research Professionals).

We have worked with DWP to understand the aims of the research. The design, delivery and analysis were carried out impartially, and comply with the MRS (Market Research Society) Code of Conduct.

Full transparency regarding research methods has been provided to DWP at every stage, and all research materials were designed with input from DWP. Anonymised microdata, data tables, data file specifications and detailed methodological information are supplied alongside this report to allow DWP to replicate and test the data. All differences between sub-groups noted in the text in the report have been statistically tested. For more information, please see the Methodology Section of the Technical Annex.

Research ethics were considered at design stage and throughout the project. It was recognised that many research participants have been through difficult and traumatic experiences, since SMI is often required by people who have previously been able to afford to buy a house from their own income but have experienced a life event which makes this difficult or impossible, putting them at risk of losing their home.

For example, processes were put in place during fieldwork to support research participants and interviewers.

Quality

This evaluation has used a Theory-based Approach, compliant with the guidelines laid out in the Magenta Book[footnote 1]. DWP developed a Theory of Change, which IFF reviewed and advised on as an external consultant. IFF developed an Evaluation Framework which provided structure to the research and ensured it stayed focused on the research aims set by DWP.

The research relies in part on quantitative survey data. The survey was carried out using a design approved by DWP and using an RPS (Randomised Probability Sampling) approach. Data was gathered by our dedicated telephone interviewing team, who all receive a full training programme before they start working on projects. Telephone interviews are recorded, and a dedicated QA (Quality Assurance) team are tasked with random checking of interviews to ensure they meet quality standards.

The resulting data was generated in a replicable way through a script devised by our programming team, and QA checked by 2 researchers, and further checked by the DWP research team. It was weighted to ensure representative results, using techniques approved by 2 senior research team members. For more details, consult the Methodology Section of the Technical Annex.

Qualitative interviews were all carried out by trained recruiters and interviewers, using research materials and confidentiality protocols agreed with DWP. Data was analysed using qualitative frameworks in Microsoft Excel, designed to be linked back to the evaluation framework.

Reporting outputs were written by our research team and quality assured by senior research team members, as well as by the DWP research team.

Value

The findings of this research report have improved the housing welfare evidence base and provided further insight into homeowners that utilise the Support for Mortgage Interest loan.

The research will be used to review the aims and impacts of the SMI scheme. It will feed into wider discussions on how the Department for Work and Pensions can best deliver the policy and ensure homeowners continue to be protected from possession.

Executive Summary

This report provides insight into the impact of Support for Mortgage Interest (SMI), a policy introduced to prevent low-income homeowners from losing their homes by providing a loan to them, which makes a contribution towards their mortgage interest. It also looks at how the policy has been carried out. The report is supported by a survey and in-depth interviews with people receiving the loan (see Chapter 1), and 6 interviews with mortgage lenders (see the Lender Annex). Surveys and interviews took place between December 2023 and October 2024 and aimed to show if SMI was achieving its policy goals as well as understanding the impact on recipients’ lives.

The research found that SMI reached the intended group of people (see Chapter 2); those interviewed were in mortgage arrears and without other realistic options to make their mortgage payments. Recipients rarely said that lenders had referred them to SMI. Although without a statistical calculation of impact, it is not possible to say exactly how many SMI loans are going to households which could afford to pay their mortgage in other ways, it seems unlikely that this is a substantial problem for SMI.

The recipient survey shows that the change in eligibility rules for SMI in April 2023 did change the profile of new SMI recipients compared to those claiming under the older rules (see Chapter 2). There is no evidence that recipients claiming under new rules are less in need of help; this suggests that the changes have not diluted the focus of SMI on the group of people it is intended for.

In terms of carrying out the policy (see Chapter 3), the time it took to receive SMI from application was found to be long, due to the paper-based application process. This is likely to have blunted the impact of the otherwise well-received reduction in waiting time (from the start of a benefit claim to receiving SMI) from 9 to 3 months, since the application often takes longer than this. Recipients did not generally believe that they were protected from repossession during this time, causing stress to many. Payment processes also had some shortcomings, often requiring recipients to discuss it with their lender.

Despite these issues, the positive impact of SMI was clearly shown (see Chapter 4), with hardship reducing, and recipients reporting that withdrawal of SMI would have severe impacts on their financial situation and well-being. In surveys and interviews recipients reported reduced arrears, and a reduced likelihood of losing their home. However, the survey showed that for a minority the impact of SMI was negative, with interviews suggesting this was often where payments did not provide a route out of arrears, due to high mortgage rates. The new option to move into employment was welcomed and used by new applicants for SMI, but had limited impact on previous recipients since most were unable to work because of their age or health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following.

The DWP analytical and policy colleagues for their valuable contributions to this research, particularly the Housing Research team.

The representatives of UK Finance and the Building Societies Association for their valuable help in securing lender participation.

We would also like to acknowledge and thank all the research participants for giving up their time to participate in interviews and providing valuable information on their experiences and views.

Authors

IFF Research

Lorna Adams

Sarah Cheesbrough

Sam Morris

Dani Cervantes

Georgia Mealings

Mohsin Uppal

Emily Clark

Glossary

| Term | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Equity | The portion of the value of a property which is owned by the borrower as a result of their mortgage payments, as opposed to owned by the lender. |

| Equity Release | This is the process in which a mortgager (aged 55+) can receive some of the value of their home as cash, in exchange for the provider receiving equity in the home. |

| Interest-only mortgage | An interest-only mortgage does not reduce the capital owing; if an interest-only mortgage ends, the lender will still own part or all of the property. |

| Legal charge (on a property) | A legal charge on equity within a property indicates that a loan has been taken out against it, and entitled a lending institution to take payment should the borrower fail to make repayments on that loan. If it is a ‘first charge’ that means that if the borrower fails to pay their mortgage, it is prioritised for repayment relative to other charges that may be owing. |

| Mortgage rate | The rate at which interest is charged on a mortgage. This is set by the lender (and may be fixed or variable during the mortgage), but with regard to the general interest rate set by the Bank of England, which varies over time. |

| Mortgage repayments | Mortgage repayments usually consist of a repayment of capital, and a payment of interest. The interest payment is the charge made by the lender for the service of lending the money, while the capital repayment reduces the amount owed to the lender. SMI is designed to cover the interest payments only. |

| Possession | Possession, often referred to as repossession, is where a mortgage lender takes ownership of a property when the borrower is unable to pay the mortgage. |

| Repayment mortgage | A repayment mortgage includes payments toward the capital owed; at the end of a repayment mortgage, the borrower will typically own the property outright. |

| Universal Credit Journal | An online system through which Universal Credit recipients communicate with DWP, including potentially about their SMI claim. |

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | In Full |

|---|---|

| AIR | Actual Interest Rate |

| AME | Annual Managed Expenditure |

| CA | Carer’s Allowance |

| DHP | Discretionary Housing Payment |

| DWP | Department for Work and Pensions |

| ESA | Employment and Support Allowance |

| FoI | Freedom of Information request |

| HB | Housing Benefit |

| IS | Income Support |

| JSA | Jobseeker’s Allowance |

| PC | Pension Credit |

| PQ | Parliamentary Question |

| PIP | Personal Independence Payment |

| QA | Quality Assurance |

| RPS | Random Probability Sampling |

| RQ | Research Question |

| SIR | Standard Interest Rate |

| SMI | Support for Mortgage Interest |

| UC | Universal Credit |

| UCHE | Universal Credit Housing Element |

1. Introduction

This report provides findings from a Theory-based Evaluation of SMI (Support for Mortgage Interest), a policy introduced to protect low-income homeowners from possession by making a contribution towards outstanding mortgage interest payments. The evaluation, primarily based on fieldwork which took place between December 2023 and October 2024, seeks to provide understanding of the effectiveness of SMI in protecting recipients against possession (sometimes referred to as repossession) of their homes, and the wider impact on their financial and housing circumstances.

1.1 Support for Mortgage Interest

1.11 The policy

SMI is a long-standing policy, introduced as a benefit for homeowners with mortgages experiencing hardship. It makes a payment toward the interest due on the mortgage, but is not intended to cover full repayment of the mortgage.

SMI also has a secondary role; while for most recipients it is a support scheme to pay mortgage interest on an existing mortgage, disabled people (if receiving certain benefits) are permitted to purchase a home using the scheme, or to borrow funds to make adaptations to their home for their disability.

SMI was converted to a loan scheme in 2018, with the loan secured against the value of the property via taking a legal charge. Repayment of the SMI loan is limited to any available equity when the property is sold, transferred or when the claimant dies. This transition immediately resulted in a great reduction in the number of households receiving SMI, peaking at around 16,470 in May 2019, compared to more than 100,000 before March 2018[footnote 2].

Eligibility for SMI has, from the outset, been conditional on claiming an income-related benefit, such as Jobseeker’s Allowance (JSA), Employment and Support Allowance (ESA), Pension Credit (PC), and more recently Universal Credit (UC). Until April 2023, an individual of working age would need to have been claiming an unemployment-related benefit for more than 9 months, and UC recipients could not receive any earned income to claim SMI.

SMI payment amounts are not tied directly to the rate on the particular mortgage claimed for, but to an average ‘standard interest rate’, based on the average mortgage rate published in Bank of England statistics. Despite regular updating of this rate, it is at the time of writing (February 2025) lower than the rate payable on any new mortgage due to recent interest rate rises but generally higher than the rate on older fixed-rate mortgages.

The loan is also capped at an outstanding mortgage value of £200,000 for working age recipients and £100,000 for pension age recipients who applied post pension age[footnote 3], also referred to as the ‘capital limit’[footnote 4]. This means those claiming for an outstanding mortgage balance in excess of the applicable amount will receive payments toward mortgage interest calculated as if they owed £200,000 or £100,000.

1.12 Cohort 1 and Cohort 2

Changes were introduced in April 2023 to extend eligibility to working households on Universal Credit, and to reduce the waiting period for eligibility from 9 months to 3 and allow for SMI claims to restart without serving the qualifying period where short breaks in qualifying benefits occurs for less than a six-month period (e.g., due to a benefit sanction).

Beneficiaries of these changes are referred to in this research as ‘Cohort 2’ recipients. Those who would have been eligible previously are referred to as ‘Cohort 1’ recipients, even if they started claiming after the changes were made in April 2023.

1.2 Evaluation

1.21 Reasons for evaluation

DWP identified a need for greater understanding of the effectiveness of SMI in protecting recipients against possession of their homes, and the wider impact on their financial and housing circumstances. There was previously little evidence available to the department on the impact of SMI on recipients since the change from a benefit to a loan in 2018.

1.22 Aims and scope of evaluation

The main aim of the research is to assess the impact and effectiveness of SMI in helping recipients who own their home with a mortgage, to keep them in their homes and protect them from possession. DWP are also interested in the effectiveness of SMI in terms of meeting mortgage payments, and the wider impact on financial and housing circumstances[footnote 5].

The research was envisaged to take a theory-based approach, using a range of quantitative and qualitative techniques, united and directed by a Theory of Change and evaluation framework produced through a scoping stage. While the evaluation seeks to understand impact, the scope for the research does not include measuring impact numerically[footnote 6], nor in terms of economic impact, for example to produce a cost-benefit analysis.

1.3 Scoping and evaluation structure

1.31 Approach to scoping

Initial research questions were set by DWP in the planning stage during 2023, but were further refined in a scoping stage led by IFF Research, from December 2023 to January 2024. This included stakeholder discussions, and an initial evidence review.

The process focused on developing a full understanding of the policy, culminating in the production of a Theory of Change, a single diagram which outlines how the policy is intended to work, and provides a structure for the evaluation. It considers the inputs to the policy, activities which are involved, the immediate outcomes and long-term outputs of the policy for claimants, lenders and the government.

1.32 Theory of Change

A Theory of Change was developed and reviewed by DWP using the outcomes of sessions held with internal DWP stakeholders from the relevant policy, analysis and operations teams. This model was then reviewed by IFF Research, resulting in amendments agreed with DWP. The completed model was then reviewed in a short session with all stakeholders. This provided support to the IFF team when assessing the policy, by outlining its intended objectives.

1.33 Evaluation questions

The next stage of the scoping was to build on the Theory of Change to produce final evaluation questions, via discussion within the research team following the sessions. The evaluation questions drew on 3 sources:

- The Theory of Change

- DWP input at inception stage

- Stakeholder discussions

A total of 11 research questions were produced through this scoping process:

RQ1. What are the main reasons recipients apply for SMI in the first place?

RQ2. To what extent does SMI impact on lenders’ forbearance practices?

RQ3. Do lenders understand SMI, and what is their experience of the scheme?

RQ4. What are recipients’ experiences of navigating the SMI system?

RQ5. Are SMI loans seen as a temporary or long-term solution to financial difficulties?

RQ6. Does the current level of SMI provide sufficient support?

RQ7. To what extent does the removal of the zero earnings rule incentivise work for current recipients?

RQ8. Are the current capital limits sufficient to provide the protection needed by recipients?

RQ9. Should the criteria for eligibility be altered or extended?

RQ10. To what extent have the recent changes to SMI eligibility affected recipients’ decisions to apply?

RQ11. How, and to what extent, does the scheme prevent arrears and possessions?

Next, the research questions and Theory of Change were brought together to determine assumptions (or elements of the policy) which could be tested by the evaluation, please see the Methodology section of the Technical Annex.

For example, the SMI policy assumes, relevant to answering RQ1 (“What are the main reasons recipients apply for SMI in the first place?”), that recipients are unable to pay their mortgages without support. This is an assumption which can be tested through the evaluation, to prove the Theory of Change (and therefore the logic behind the policy) is valid.

In order to test assumptions, potential measures were then scoped out. For the example above, testing could be achieved by exploring recipients’ views of why they claimed SMI, and whether they sought first to access any alternative forms of support. Together, these measures could prove that the SMI policy is needed because recipients could not pay their mortgage and did not have other support.

Finally, each measure was assigned in a practical sense to an element of the evaluation; for example, the recipient view of whether they required SMI was measured through qualitative recipient interviews, and the extent of seeking other forms of support was measured through the quantitative recipient survey.

All this information was gathered into an evaluation framework document, containing full lists of research questions, assumptions, measures, and methods of measuring. This evaluation framework was used throughout the research to guide the process, and has been used to compile this report. Each chapter ends with a summary of the findings relevant to the research questions above.

A copy of the Evaluation Framework is included in the Methodology section of the Technical Annex.

1.4 Methodology

1.41 Research elements and timeline

The research included the following elements:

- Scoping, as outlined above (December 2023 to January 2024)

- Six qualitative interviews with mortgage lenders (February to September 2024)

- 25 qualitative interviews with Cohort 1 SMI recipients (March 2024)

- A quantitative telephone survey of 1,408 SMI recipients, including a pilot (July to October 2024)

- 20 qualitative interviews with Cohort 2 SMI recipients (September to October 2024)

Elements from all of these are included in this report, although due to the limited number of lender interviews, except where specified, insight from this group is included only in the appendices.

1.42 Methodology

Recipient survey

The recipient survey design and fieldwork periods were split over a pilot and a mainstage. Sampling frame and contact details were sourced from DWP records of SMI recipients, based on SMI claims paying to recipients across Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) in a six-month period running from July to December 2023. The survey was designed to take around 20 to 25 minutes to complete, and all fieldwork was carried out by telephone. For respondents based in Wales, all communication, including advanced letters and the administration of the survey itself was offered in Welsh as well as English.

To minimise sources of bias in the survey, this was an RPS (Random Probability Sampling) survey. This means all sample records for recipients were treated equally (contacted an equal number of times, unless a definite outcome is achieved such as a refusal or completed survey). However, not all records needed to be sampled to obtain the 1,400 survey responses sought. In order to allow analysis of key subgroups, oversampling was applied to Cohort 2 and recipients whose primary benefit was Income Support.

Sampled SMI recipients were first sent advanced letters giving notice of the survey in May 2024, allowing for an opt-out period. The pilot survey then took place in July 2024, delayed by the 2024 election. Once pilot fieldwork was completed, work began on updating the questionnaire and conducting the sample draw ahead of the mainstage survey fieldwork period, which took place from August to October 2024.

Overall, the response rate relative to the sample uploaded for telephone fieldwork was 21%, and 1,408 completed surveys were achieved. Due to oversampling and variation in response rate, the raw data produced by telephone surveys is not representative of the population as a whole. To be representative of the population, a non-response weight and a sampling weight were applied, so that survey results reflect the sampling frame supplied by DWP.

The survey remains subject to sampling error. The estimated maximum error margin (i.e., on a result of 50%) for weighted survey results is ±2.7%. So, if the weighted survey data indicated that 50% of recipients were happy with an element of SMI, we could be 95% certain that the true result if the whole population were surveyed would be between 47.3% and 52.7%. This is a maximum error margin; for results closer to 0% or 100% (e.g., if 90% of recipients were happy with an element of SMI) the error margin would be narrower.

Further details of the methodology for the survey can be found in the Technical Annex.

Qualitative recipient interviews

In-depth qualitative interviews were carried out with SMI recipients in both Cohort 1 and Cohort 2. A total of 25 interviews took place with Cohort 1, and 20 with Cohort 2.

For Cohort 1, sample was supplied by DWP, as for the quantitative recipient survey. A purposively selected sample of 149 records (to match the desired profile of interviews) was drawn. For Cohort 2 interviews, 116 records of recontact sample from the quantitative recipient survey were used.

All interviews, which were designed to last 45 to 60 minutes, took place via telephone with one of IFF’s team of trained telephone interviewers, as well as members of the research team. Precautions were taken for data security and to maintain confidentiality. All recipients were emailed a consent form to read through before their interview, detailing aspects such as how their data would be used and stored, and that the interview would be recorded with their consent. As the nature of recipients’ experience had often been of a sensitive nature, safeguarding and interviewer support processes were also put in place.

A response rate of 19% relative to contacted sample was achieved for the Cohort 1 interviews, and 23% for the Cohort 2 interviews. Analysis was carried out using a bespoke excel-based analysis framework, supported by an analysis meeting attended by the research team. The framework was structured around thematic headings relating to the research objectives. Individual interviews could then be compared to determine the commonality of experiences.

Further details of the methodology for the interviews can be found in the Technical Annex.

Qualitative lender interviews

Six lender interviews were also carried out, with sample sourced from the Building Society Association and UK Finance, covering larger and smaller banks, building societies and lenders. The interviews were designed to last 45 to 60 minutes, and were conducted via Microsoft Teams, utilising the transcript function only. While within the 6 interviews all of the groups listed above were represented, sample availability and willingness of individuals to take part did significantly delay the research. All of the Lender qualitative interviews took place via Microsoft Teams with one of IFF’s experienced research team.

Few sample records were available to researchers; a response rate of 86% was achieved. Due to the small number of interviews carried out, findings from these, which were analysed through an Excel-based analysis framework and analysis meeting, are summarised in a separate annex. Further details of the methodology for the interviews can be found in the Technical Annex.

1.43 Analysis conventions

Recipient survey

All results shown, unless otherwise stated, are weighted to be reflective of the views and experiences of recipients as a whole (see Technical Annex section 1.58), rather than purely representing the views of survey respondents. In this report, only statistically significant differences between sub-groups of SMI recipients[footnote 7] (see Technical Annex section 1.59 ) are shown in the text, in order to avoid the risk of including random variation. Significant differences are shown in charts with a star.

Survey respondents may sometimes express opinions which are incorrect, or may not accurately recall their experiences or situation. This type of error cannot be quantified.

Qualitative interviews

Qualitative interviews represent the range of views and opinions among those taking part, and are intended to give in-depth insight into the reasons for people’s views and actions. Results from interviews are not intended to provide insight into numerical prevalence of those views. For this reason, numeric estimates (i.e., percentages of interviewees making a particular statement) are not given. Individual experiences and quotes represent the views of interviewees. Where we know there to be inaccuracies in a quote, this is stated, but quotes are not routinely tested for accuracy, and represent the views of participants, not of IFF Research or DWP.

2. Decisions to use SMI

This chapter summarises SMI recipients’ awareness of SMI prior to applying, and their reasons for applying, and explores the resulting profile of recipients. It finds that applications are strongly motivated by need, with most recipients having experienced an unexpected trauma in their lives, leading to their inability to repay their mortgage. It finds that changes to eligibility for Cohort 2 have succeeded in widening the recipient base for SMI, although the research cannot prove all newly eligible borrowers are being reached.

2.1 Why apply for SMI?

2.11 Becoming aware of SMI

Among recipients, DWP dominated as a route for learning about SMI, as shown in Figure 2.1; more than half of recipients (53%) heard via this route. Qualitative interviews with recipients supported this view. Recipients interviewed in both cohorts mentioned primarily services within DWP, for example their Universal Credit journal, work coach or most often Jobcentre Plus. Not all had been successful immediately; one mentioned that they had asked in their UC journal, but had not found out about SMI until searching online themselves.

When I went on to my journal and I asked about SMI, someone said, ‘oh, you have to speak to your… case worker, and they’ll send you a form to fill out.’ But I never got hold of my caseworker… [it took] a few months to try and get this form – Cohort 2, Male, 55-64, Large claim.

Others also mentioned learning about SMI online, although they were typically unable to recall where exactly they had heard. Some had done research themselves on ways out of their situation, consulting multiple sources.

Yeah, I thought it was a good scheme, you know. I thought, oh, if I could go onto that it would really help me out – Cohort 2, Male, 45-54, Average claim.

In Cohort 1, where recipients had previously received the SMI benefit, qualitative interviews provided more detail, with recipients saying awareness of SMI frequently came via a letter about the switch from a benefit to a loan from DWP, or occasionally from a debt advice charity. Cohort 2 recipients tended to hear from DWP by phone or online, as expected since initial contact for this group is normally by telephone.

I think I was contacted by Universal Credit [on the phone]. They basically asked me if I wanted to go ahead with [SMI] – Cohort 2, Female, 55 to 64, Average claim.

The survey suggested that it was much more common to hear through support organisations such as Citizen’s Advice (12%) or Jobcentre Plus (10%) than from a mortgage lender (5%). Some instances of initial contact about SMI being made by lenders were found in interviews, where a borrower had contacted them worried about their mortgage. Another had learned about SMI through an Independent Financial Advisor (IFA), and one through their Macmillan nurse.

For longer claims, there were some instances of recall issues in interviews (in Cohort 1), where recipients could not remember how they became aware of SMI, often mentioning that they had been transferred over from the benefit to the loan but unable to give much detail.

The survey shows that many SMI claims are long-standing; 77% of recipients have owned their home longer than 15 years, so in many cases they are recalling events from many years ago. Many qualitative interviewees gave dates for starting SMI considerably before the date on DWP records, suggesting that events during the claim (e.g., switching from a benefit to a loan, changing benefit status) may reset the claim length record.

Those applying for SMI recently (since April 2023) did not give markedly different answers to other recipients, although they were slightly more likely to have learned about SMI from another online source [footnote 8].

Figure 2.1 How recipients first heard about SMI

Source: SMI Evaluation recipients survey. Base: All (1,408). Cohort 1 (1,135), Cohort 2 (273). B1. How did you first hear about SMI? Respondents could provide more than one answer.

Some other key sub-group differences emerged in the survey. Those in employment, and those on UC (overlapping groups) were more likely than others to hear about SMI through Jobcentre Plus (15%). In general, older people were more likely than others to hear about SMI through DWP, ranging from less than half among under 45s (43%) to nearly two thirds among over 75s (61%).

2.12 Deciding to claim

Findings from the recipient survey [Figure 2.2] and both Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 interviews, showed a range of reasons why respondents initially applied for SMI, however a life event affecting the recipient’s or their partner’s ability to work or cause loss of income dominated. The most common broad reason for needing an SMI loan or benefit was loss of income (71%).

The most commonly cited single response option in the recipient survey was that either the respondent or their partner had to stop working due to a disability (42%). A further 7% stated that either they or their partner had to stop working due to caring responsibilities, meaning that half of respondents initially applied for SMI due to a reason associated with disability. This was higher[footnote 9] amongst Cohort 1 recipients on legacy benefits (57%), those who first claimed prior to April 2018 (56%) and ESA recipients (60%), but lower amongst PC recipients (24%).

Other than reasons associated with disabilities, this could be due to a respondent (15%) or their partner (2%) losing their job; this was higher for respondents in receipt of UC (18%)[footnote 9]. A change in personal circumstances, such as a divorce or a bereavement (12%) was also stated as a reason to claim.

General loss of income was higher[footnote 9] amongst UC (77%), ESA (76%), and PIP (74%) recipients, but lower[footnote 9] amongst PC recipients (49%).

Very few recipients applied in order to make disability adaptations to their home (<1%, only 3 respondents), indicating that this additional stated purpose of SMI is rarely used.

Figure 2.2 Reasons why recipients first applied for SMI

A5. Why did you originally need to apply for an SMI loan? Base: All respondents (1,408). For legibility, excludes Unable to work due to other caring commitments (1%), my partner stopped working to care for me (1%), applied for SMI in order to pay for disability adaptations to home (<1%), other (1%), and prefer not to say (<1%).

Findings from the qualitative interviews also corroborated this, with a large proportion stating that they needed the extra income and needed to lower outgoing costs. Life circumstances had usually led recipients into financial hardship which meant they were struggling to keep up with mortgage payments.

This was often because their household income had decreased, due to not being able to work due to a disability or illness, or a change in their household situation causing lost income and they needed the SMI loan to replace this. Sudden illness, disability or mental health problems, and less commonly redundancy or sudden failure of businesses (perhaps particularly at Cohort 2) were a recurring theme throughout:

It’s a bit of a lifeline… I’m trying to think of ways of dodging the bullets here, you know. It’s affected my mental health. I was earning pretty good money when I was working to go from like that to nothing really is quite depressing – Cohort 2, male, 55 to 64, large claim.

In some cases, breakdown of relationships played a role, as the remaining parent in the home was suddenly a single parent and unable to work.

Many said they applied for the SMI loan as they didn’t want to lose their home, and so they would accept it being a loan if it meant it would prevent them having to move out. Some respondents mentioned spontaneously that they were determined to avoid losing their home, in some cases for long term financial reasons (not wanting to rent into retirement) but also due to the emotional and psychological impact of moving, particularly where they had already experienced other recent traumatic events. In some cases, disability played a role:

Because we wanted to stay in our home. It was all converted for my disability …and it was our home, our children grew up there… – Cohort 1, Female, 55 to 64, Large claim>

Often, recipients had been reluctant to take out anything described as a loan, but did not perceive a choice:

I wouldn’t have been able to afford my mortgage. The [SMI benefit] I used to get, once they took that away, I didn’t have that money to put towards my mortgage, so I had to take [the loan]. I was backed into a corner – Cohort 1, female, 45 to 54, Average claim.

Only rarely did interviewees mention seeking advice before making a decision, one from an IFA, and a couple from family friends with some knowledge. Some had given their options some thought, and decided SMI was the best available to them:

I still have more money than if I’d left and gone into a long-term tenancy – Cohort 2, Male, 45 to 54, Average claim.

A small number of recipients surveyed (4%) stated SMI was offered to them or they automatically received it. Some Cohort 1 interviews were carried out with this group; those recipients felt they had done as DWP told them to by transferring. They often had quite limited knowledge of how SMI worked or that it needed to be paid back; one interviewee was shocked to get a letter saying they had borrowed £13,000 in SMI.

Another was worried that the SMI loan would be inherited as a debt by her children. In one case a respondent got into unexpected difficulties as their mortgage was coming to an end, since they had not realised that they could no longer take out other loans or equity release products against the value of their home, and they were not eligible to extend the mortgage term or remortgage due to their age and/or credit rating. SMI is always secondary to primary mortgage lenders and should not prevent remortgaging, but some recipients also reported that lenders were unwilling to consider them in any case. Equity release providers will only consider cases without any charges on the property, so SMI recipients are not eligible for this.

2.13 Considering alternatives

While those interviewed rarely mentioned other options they had tried before SMI other than borrowing from family and friends, findings from the survey showed that recipients had tried a range of options before taking up an SMI claim. Three quarters (74%) of recipients mentioned that they reduced spending other than by postponing or not paying bills [Figure 2.3]. This was even higher[footnote 10] amongst Carers Allowance recipients (91%), and ESA recipients (78%), but lower[footnote 10] amongst PC recipients (63%).

Most of this group also said when asked that they had cut spending on things which could be regarded as essentials, including:

- Food (83% of those reducing spending); higher[footnote 10] amongst UC recipients in Cohort 1 (88%), and lower amongst PC recipients (71%)

- Other essentials such as clothes and shoes (75%); lower[footnote 10] amongst PC recipients (66%)

- Energy or water (65%); higher[footnote 10] amongst IS recipients (79%)

Overall, around 4 in ten stated that they had sought help from their lender (43%). This was higher[footnote 10] amongst UC recipients at Cohort 1 (53%), and Cohort 2 (54%) recipients, but lower[footnote 10] amongst PC (31%) recipients

Those seeking help from their lender most often received[footnote 11]:

- a mortgage holiday (28% of those seeking help); higher[footnote 10] amongst UC recipients (34%) and lower[footnote 10] amongst PC recipients (13%)

- a move to an interest-only mortgage (15%)

- Extending the mortgage term (12%)

Many recipients also postponed or did not pay other bills (43%). More than a third had also run down their savings (36%) or borrowed money (35%). Those seeking to borrow money were usually successful (78%), and most often borrowed informally from friends and family (86% of those successfully borrowing), although some borrowed from banks or building societies (24%), or from specialist loan companies (14%). There were also instances noted by recipients in the qualitative interviews of mortgage holidays being allowed by lenders before resorting to SMI (e.g., not having to pay for 6 months to give them a chance to get back on their feet).

Only around a fifth of recipients (19%) said they had looked for work before seeking to use SMI; this was higher10 amongst Cohort 2 recipients (32%), Carers Allowance recipients (30%), and UC recipients (25%).

Figure 2.3 Actions taken prior to first SMI payment

B2. Prior to your first SMI payment being made, did you try any of the following to try to make your mortgage payments? Base: All respondents (1,408). Answer codes under 10% not shown (Considered selling my home: 3%, Used benefits: 1%, Approached a charity: 1%, Took in a lodger: <1%, Cashed in my pension: <1%, Other: 3%, None of the above: 5%.)

2.2 Coverage of SMI

2.21 Profile of SMI recipients

Most recipients of SMI responding to the survey were not in employment (89%), and most of these were out of work due to long-term sickness or disability (55% of all recipients) or retired (18%). A smaller proportion, 16%, of recipients were unemployed, other than due to disability or retirement.

For Universal Credit claimants before April 2023, moving into employment would result in a loss of entitlement to SMI. Therefore, nearly all those employed were in Cohort 2[footnote 12]. Among Cohort 2 recipients, nearly half (46%) were employed, split between full time employment (15%), part-time employment (18%) and self-employment (10%). However, only 5% were unemployed[footnote 13]; many Cohort 2 recipients were still out of work due to long-term sickness or disability (33%), although few were retired (3%).

The survey also gathered data on the working status of the respondents’ partner[footnote 14]; across both Cohorts about two-thirds (67%) were in a working-age household[footnote 15] where no adults were employed. About one in 5 (19%) lived in a household where either the respondent or their partner was retired. Only 13% of recipients lived in a household where either the respondent or their partner was employed, although this rose to over half (54%) among Cohort 2 recipients.

By the nature of the scheme, all SMI recipients would be expected to claim some kind of benefit. Benefits claimed are shown in Table 2.1 and Table 2.2. Seven in ten recipients (70%) claimed disability related benefits, and just under half (44%) claimed out-of-work benefits.

Recipients taking part in qualitative interviews often mentioned a changing landscape of benefits over time, in particular shifting in and out of different levels and combinations of disability benefits due to successive DWP assessments. Pension Credit, however, was a relatively stable benefit once provided.

Table 2.1 Benefits claimed by SMI recipients, Cohort 1 vs Cohort 2, self-reported**

| Respondent, Cohort 1 | Respondent, Cohort 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Independence Payments (PIP) | 64%* | 44% |

| Universal Credit (UC) | 38% | 87%* |

| Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) | 45%* | 13% |

| Pension Credit (PC) | 20%* | 3% |

| Income Support (IS) | 6%* | 1% |

| Carers Allowance | 6% | 7% |

| Don’t know | 2% | 5%* |

Notes to Table 2.1

*indicates that this sub-group’s response is proven (to a 95% confidence level) to be higher than that for all other sub-groups combined.

**note some recipients may be uncertain or incorrect regarding their benefit status when asked, or it may have changed since the point of sampling.

Table 2.2 Benefits claimed by SMI recipients and their wider households, self-reported**

| Respondent | Anyone in household | |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Independence Payments (PIP) | 62% | 69% |

| Universal Credit (UC) | 44% | 47% |

| Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) | 40% | 42% |

| Pension Credit (PC) | 18% | 19% |

| Income Support (IS) | 6% | 6% |

| Carers Allowance | 6% | 11% |

| Don’t know | 1% | 4% |

Notes to Table 2.2

**note some recipients may be uncertain or incorrect regarding their benefit status when asked, or it may have changed since the point of sampling.

SMI recipients overall tend to be older, even when compared to mortgage-holders as a whole. Most (56%) recipients were over the age of 55 [Figure 2.6], compared to 19% in the Family Resources Survey[footnote 16]. The most common age band was 55 to 64 (36%). A smaller number (12%) of recipients were under the age of 45, compared to 53% of mortgage-holders nationwide.

Cohort 2 SMI recipients are markedly younger; few are over 65 (6%), and about a quarter are under 45 (29%), although few are under 35 (5%). This is much closer to the profile seen in the Family Resources Survey for mortgage-holders, where 3% are over 65, although there are differences: 22% of mortgage-holders are shown to be under 35. However, the typical factors leading to an SMI claim – disability or sickness – are more likely to occur later in life.

Figure 2.4 Respondent age, overall and by cohort

F2-Resp-Age. Respondent age. Base: All those who provided household size (1,382). 18-24 category not shown due to small size. Prefer not to say (15= 1%)

When asked about household income [Figure 2.5], around half (45%) of recipients preferred not to say. When considering those who did divulge household income, 9 in ten (91%[footnote 17] earned less than £25,000 per year, and more than half (58%) earned less than £16,000 per year.

Figure 2.5 Recipient household income, overall and by cohort

F8. How much, together, is your household’s income before tax? Base: All respondents (1,408). For legibility the chart excludes Prefer not to say (45%) and Don’t know (4%).

Just under half (47%) of recipients lived on their own; a further quarter (25%) lived with one other person. The average household size was 2 people, and was considerably larger for Cohort 2 (2.8 people) than Cohort 1 (1.9 people). Around a quarter (27%) of recipients lived in a household with children, compared to 46% of households with a mortgage in the Family Resources Survey[footnote 16].

Household types varied substantially by cohort, as shown in Table 2.3. Building on the data in the table to look at disability within household type, single households without children (90%) and couples without children (87%) each experienced higher rates of disability than couples with children (77%) and single households with children (71%).

Table 2.3 Household types in SMI recipient households, by Cohort

| Household type | % of SMI recipient households | % of Cohort 1 households | % of Cohort 2 households |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single – no children | 59% | 63%* | 32%* |

| Single – children | 17% | 14%* | 42%* |

| Couple – no children | 14% | 14% | 11% |

| Couple – children | 10% | 7% | 15%* |

DWP sample data for survey respondents. Base: All (1,408).

In terms of ethnicity, four fifths (79%) of recipients identified at White British or Irish, compared to 88% of mortgage holders in the Family Resources Survey16. No one ethnic minority dominated; in total 2% of recipients identified as White Other; one in ten (9%) as Asian/Asian British; 5% as Black/African/Caribbean/Black British; 2% as Mixed/Multiple Ethnic Groups; and 1% as Other Ethnic groups.

All in all, just under one fifth (17%) identified as ethnicities that might be classed as an ethnic minority group, rising to 19% if White Other is included.

Over four fifths (85%) of respondents stated that they had a disability [Figure 2.6], far above the 25% saying one or more adult household members had a disability or long-term illness in the Family Resources Survey[footnote 16]. Of these disabled SMI recipients;

- Four fifths (79%) said that their disabilities limit their activities all of the time

- One fifth (19%) said it limits their activities some of the time

- A very small percentage (2%) said their disability does not limit their activities

Over half (56%) of respondents who do not live alone stated that someone else in their household has a disability. In total, 23% of households using SMI contain multiple disabled people, and 89% of households overall contain someone with a disability.

For some people, disability was key reason for applying for SMI:

Because we wanted to stay in our home. It was all converted for my disability …and it was our home, our children grew up there… – Cohort 1, Female, 55 to 64, Large claim.

Figure 2.6 Disability status of respondents

F3. Do you have any physical or mental health conditions or illnesses lasting or expected to last for 12 months or more that limits your or their day-to-day activities? Normal day to day activities include everyday things like eating, washing, walking and going shopping. Base: All respondents (1,408). For legibility, excludes don’t know (1%) and prefer not to say (1%).

As can be seen in Table 2.4, there are some regional variations in the usage of SMI; relative to the number of households with a mortgage, SMI is much more likely to be used in Wales (62% higher), the North West (42% higher), and West Midlands (20% higher) and less likely in the South East (23% lower), Scotland (20% lower), the East of England (16% lower) and London (11% lower). There is no clear pattern to these discrepancies, and Cohorts 1 and 2 show broadly the same pattern.

Table 2.4 Household types in SMI recipient households, by region

| ONS Region | % of SMI recipient households | % of all GB households paying a mortgage |

|---|---|---|

| North East | 5% | 4% |

| North West | 15% | 10% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 8% | 8% |

| East Midlands | 7% | 8% |

| West Midlands | 10% | 8% |

| East of England | 8% | 10% |

| London | 11% | 13% |

| South East | 12% | 15% |

| South West | 9% | 9% |

| Wales | 7% | 4% |

| Scotland | 7% | 9% |

DWP population data for survey, January 2025. Family Resource Survey, 2022-23.

2.22 Comparing Cohort 1 and 2 recipients

From the survey, when comparing both SMI cohorts, there were a number of differences, many of which relate to the eligibility rules for Cohort 2 which are more accommodating to younger, working-age people. Cohort 1 participants were more likely to:

- be older, 12% were over the age of 75 (vs. <1% in Cohort 2). The most common age group in Cohort 1 was 55 to 64 (38%), whereas for Cohort 2 it was 45 to 54 (36%)

- have disabilities (88% vs. 62% in Cohort 2) and disabilities that limit their activity all of the time (71% vs. 43% in Cohort 2)

- be out of work due to a long-term sickness or disability (58% vs. 33% in Cohort 2)

- have owned their home for more than 15 years (80% vs. 55% in Cohort 2)

- have lower amounts remaining on their mortgage (12% less than £25,000 vs. 4% in Cohort 2; 16% between £25,000 and £49,999 vs 8% in Cohort 2; and 9% with £200,000 or more vs. 16% in Cohort 2)

- live in a household without children (82% vs. 49% in Cohort 2)

- claim disability-related benefits (73% vs. 46% in Cohort 2), such as PIP (64% vs. 44%), ESA (45% vs. 13%), IS (6% vs. 1%)

2.3 Implications for policy

RQ1. What are the main reasons recipients apply for SMI in the first place?

It was identified at the scoping stage of this research that recipients should be unable to pay their mortgage without support, and that borrowers in arrears would need to be aware of the SMI loan scheme.

Positively for the scheme, all of those interviewed for the research appeared to be in the target group; they were in mortgage arrears and usually had obvious obstacles to paying their mortgage using their own resources. Many recipients were claiming SMI due to experiencing a traumatic life event. The profile of SMI recipients is dominated by those who have disabilities, illnesses or are otherwise unable to work; even in Cohort 2 which allows working recipients, many had experienced a major career setback, redundancy or a divorce.

This research was not able to determine reasons recipients do not apply for SMI, or whether there are significant numbers of non-applicants. This was explored by research in 2020 following the conversion of the SMI benefit to a loan[footnote 18].

RQ10. To what extent have the recent changes to SMI eligibility affected recipients’ decisions to apply?

The change in rules has been accompanied by a change in the profile of SMI recipients; while Cohort 1 recipients (from before the rule change) are primarily above retirement age and a large majority are disabled, Cohort 2 recipients are somewhat closer to the average demographic profile of mortgage holders in England, and some are working or have children.

That being said, there is no evidence that Cohort 2 recipients were in substantively less need than Cohort 1; they also tend to make larger claims (in terms of pounds per month) since their mortgages are at an early stage, which may increase the headline cost of SMI for government relative to the number of recipients. On the other hand, most recipients interviewed said that if they lost their homes they would expect to rent privately. This may mean claiming housing related support, such as Housing Benefit (HB) or Universal Credit Housing Element (UCHE). Since they are benefits, rather than loans, and rents are typically higher than SMI payments, this could incur greater costs for government overall.

3. Receiving SMI

This chapter explores the practical process of applying for and receiving SMI. It finds that while the process is easy for many applicants, there are widespread issues of reliability and ease of use. Understanding is the key barrier to easy application, but length of time taken for applications had more acute effects, reducing the practical effect of the generally positively received change in eligibility period for UC claimants from 9 months to 3 months.

3.1 Applying for SMI

3.11 Design and support

Information regarding the intended design of SMI can be found in section 1.22 of the Technical Annex.

Recipient experience of initial contact and form design

Recipients broadly remembered this process taking place in qualitative interviews, although they often had difficulty following it at the time. Usually, they had little difficulty obtaining the form, with many describing this as ‘easy’.

There were some Cohort 1 recipients who described receiving a letter about their SMI benefit changing into a loan. Most recipients reported the transfer to a loan being a straightforward process, requiring them to fill in a form that facilitated this transfer, although not all understood the implications.

In a few cases, requesting the form via the UC journal was not immediately successful, or took some time. Delays at this point were not uncommon, although they seemed less likely where the forms had been obtained in-person from a Jobcentre Plus or another support organisation.

For example, multiple recipients reported that they were told on enquiring that they would receive a call within 28 days; while this did usually happen, the delay to the initial discussion (which often led to a further referral for a call from another colleague, adding another waiting period) meant that it took many months to receive SMI, despite the shorter 3 month wait intended for those qualifying under Cohort 2 characteristics.

Several interviewees reported confusion among local DWP staff when they asked about SMI and for SMI forms:

[It was] an absolute nightmare… nobody in Universal Credit really knew much about it. To tell you the truth, even on the helpline… I was typing [in my UC journal] in capital letters: ‘Could somebody who knows what they’re talking about please get back to me. This is what I’m entitled to.’ Nobody even knew what department… to direct me [to] – Female, Cohort 2, 45 to 54, Small claim.

One person interviewed at Cohort 1 mentioned that it took them months to work out how to obtain the form; another at Cohort 2 mentioned that they had asked for the form from their work coach, and they had declined on the basis that it would arrive automatically later, which it did not, and he subsequently had to chase for it:

Initially I looked online to see how you could apply… the GOV.UK website… and there was nothing there! I contacted my work coach via my [UC] journal directly, and I said to him [that] I needed information. I said, ‘can you send me the forms out’ and initially, which I wasn’t very happy about, he said ‘we’re really busy, and we will send you the forms out when the time when the time’s right – Male, Cohort 2, 45 to 54, Average claim.

Some respondents, particularly in Cohort 2, felt that the SMI loan was difficult to find information on, which meant that making decisions about it was challenging. This then caused further stress as they weren’t sure if the loan would help them or not, even after applying.

[It] seemed like it was clouded in secrecy… [it was] quite a long and anxiety producing experience. The forms were hard to read and not very easy on the eye – Female, Cohort 2, 35-44, average claim.

Recipients’ sources of advice

Around two-thirds (64%) of all survey respondents stated that they had received all the support or guidance they needed to apply for SMI, with around a quarter (28%) stating the opposite. Those who applied for SMI between April 2018 and March 2023 (34%), and those who entered Cohort 2 due to the qualifying period only (43%) were more likely to say they did not receive sufficient support[footnote 19].

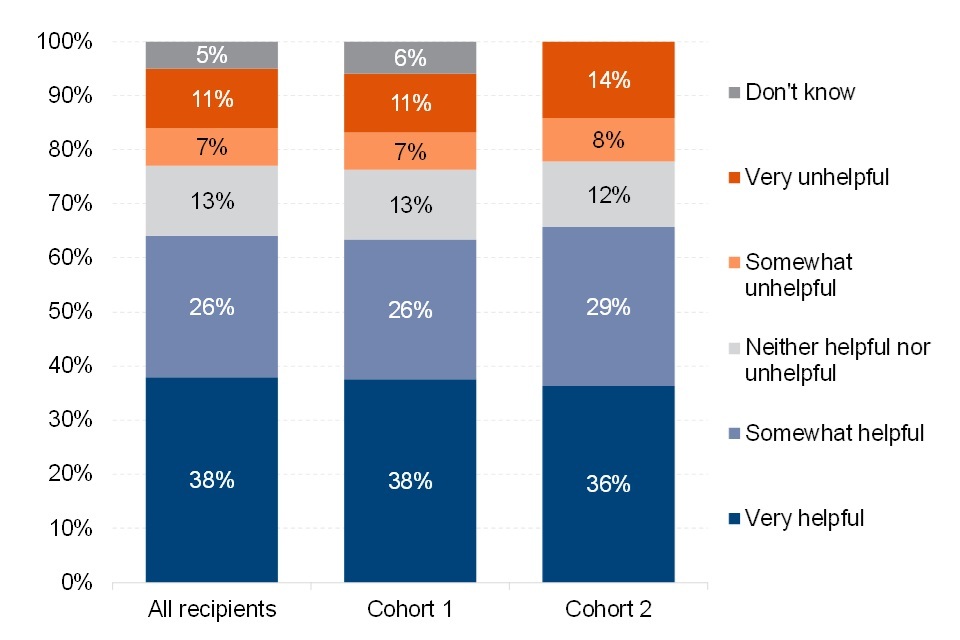

Two-thirds (64%) of respondents also stated that they found the DWP very helpful or somewhat helpful in making a claim for their SMI loan (Figure 3.1), with 18% stating that they were very unhelpful or somewhat unhelpful. UC recipients (23%), and those who made their first application between April 2018 and March 2023 (22%) were more likely than average to say DWP were unhelpful. Those aged 75 plus (73%) and in Cohort 1 in receipt of PC (70%) were more likely to say they found DWP helpful.

Figure 3.1 How helpful recipients found DWP when making SMI claim

C10. Overall, how helpful have you found DWP in making your claim for an SMI loan? Base: All respondents (1,408). ‘Don’t know’ not shown for Cohort 2 (<0.5%).

From the perspective of recipients, just over half (58%) of survey respondents found their lender helpful when making their claim for SMI, with 16% finding their lender unhelpful (Figure 3.2). 12% of respondents did not speak to their lender. Cohort 2 recipients (44%) were more likely[footnote 20] to say that their lender was very helpful.

There were also sub-group differences when broken down by Cohort 2 entry reason. Those who entered Cohort 2 due to receiving income only were more likely to say their lender was helpful (66%)[footnote 21].

SMI recipients that claimed UC were also more likely[footnote 21] to say their lender was helpful (63%). Positively, those who had first applied for SMI since April 2023 were more likely to say their lender was very helpful (44%)[footnote 21], suggesting improving performance over time.

Figure 3.2 How helpful recipients found their lender when making SMI claim

C10. Overall, how helpful have you found your lender in making your claim for an SMI loan? Base: All respondents (1,408)

3.12 Implementation

Application process

Overall, more recipients said they found the process easy than difficult; 4 in ten (43%) said they found the application process easy, with one third (33%) saying they found it difficult.

Those that found it easy often said they couldn’t remember much about the application but felt like it was straightforward enough.

It worked well for me because it was all accepted and I followed the logical steps – Cohort 1, Female, 55-64, Large claim.

They sent me a load of forms … I had to fill them out and send them back. That was it. I then had to wait to see if I was accepted or not – Cohort 1, Female, 45 to 54, Average claim

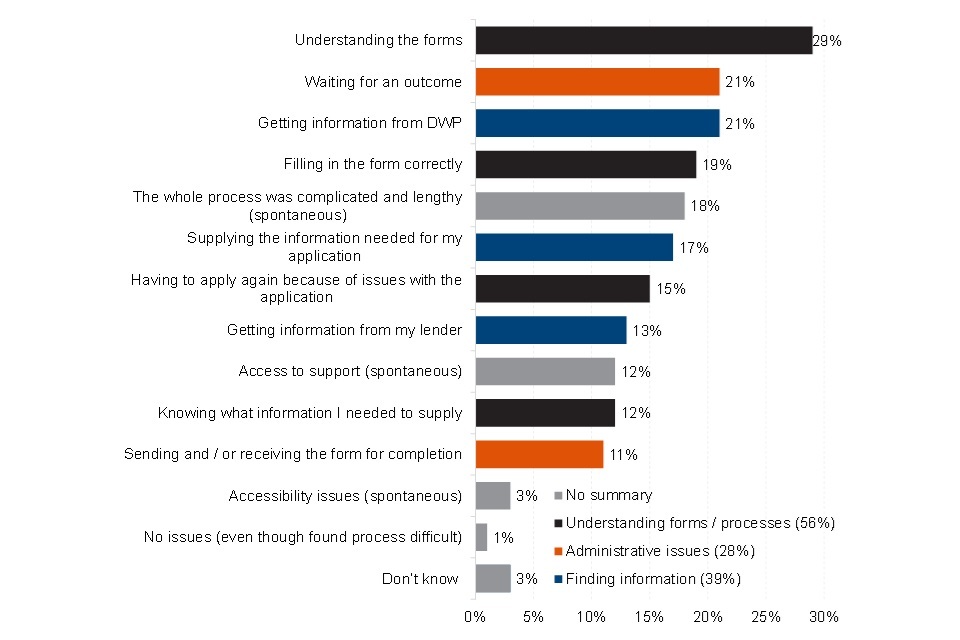

As shown in Figure 3.3, over half (56%) of those that found it difficult gave reasons that could be classed as a lack of understanding of forms or processes, such as understanding the forms (29%), filling in the form correctly (19%) or knowing what information was needed (12%).

In interviews, those that found the application process easy said it was straightforward and relatively easy to complete. However, even those who found it easy often commented that they felt they had the skills to fill it in (perhaps from past employment) but felt others might struggle due to the length and complexity of the form and nature of the process. For example, one respondent, applying early in the roll-out of Cohort 2, found the process complex although personally they did not have a problem with it:

I’m a former headteacher, I know about forms. If they were doing a good job, it should be a transparent process… it should clearly state the address to return the form to, the deadline – none of those things were available on the form. I got a loose-leaf form, not stapled – Cohort 2, Male, 55 to 64, Large claim.

Those that reported the application being difficult often said they felt it was a very complex form to complete, particularly mentioning the issue of legal jargon. They felt that the form was quite stressful to complete, and this produced feelings of anxiety because of the extent of information required. This was further compounded by the feeling that there was no service available to check that they were filling in the form correctly. Although Citizens’ Advice do offer such a service, they have limited capacity, and this is not proactively promoted by DWP.

As I said before… we are educated and able to deal with forms and information like that. But you know, we just found it quite tricky and I’m just thinking we filled out the form that we thought we had to. But there’s no one that we could check it with – Cohort 2, Female, 35 to 44, Average claim.

Reasons that could be classed as difficulties finding information were stated by 4 in ten respondents (39%). This was higher among respondents who had made their first claim since April 2023 (52%)[footnote 22]. Sometimes, interviewees felt unsure if they had filled in the form correctly, and the lack of validation (as might occur automatically with an online form, or might occur at a helpdesk with an in-person process) worried them:

You don’t have anyone holding your hand and walking you through it, it’s not like Universal Credit where the person behind the desks helps you through it – Cohort 1, Female, 55 to 64, Large claim.

Figure 3.3 Reasons why recipients found SMI application process difficult

C2. What did you find difficult about the SMI application process? Base: All those who found SMI application process difficult (458)

After completing the forms, there was a process of working out where to send them; this was usually unproblematic although it could occasionally take a while to determine the correct address or office at the lender to send the form to. Many recalled that they did not have much communication with their lender about their application or the SMI loan.

Once the forms had been sent by post to the lender, there was a period of waiting. This was often referred to as a nervous period by respondents, given that during this time they were unable to pay the mortgage and would be receiving demands for payment. Sometimes, interviewees felt they were filling in the forms and sending them off without knowing if they had included the right information, which led to an extended period of uncertainty around whether they would be accepted or not. For some, this period was not too long and ended with a successful outcome:

I thought it was quick actually; I didn’t think that it was that long [to wait] – Cohort 2, Female, 35 to 44, Average claim.

However, apart from uncertainty about the forms, there was the uncertainty whether they had arrived first with the correct person at their lender, and then at DWP. Therefore, these wait times sometimes caused anxiety. These fears were not entirely unfounded; many interviewees mentioned forms becoming lost in the post, or being refused on arrival due to errors made by themselves or in one case by the lender.

When forms were lost or refused, this meant that after a period of waiting and checking if it had been received, they then had to do the whole application again, so that they had to wait for much longer to receive their first payment. Lost forms could happen between themselves and the lender, between departments within the lender, between lender and DWP, or between DWP departments.

The forms went missing. We had to do the forms again, then they’d gone to different departments, and they had problems tracking them down….it took a while – Cohort 1, Male, 35 to 44, Average claim.

One recipient said they found the application process particularly stressful, as they said DWP lost their application several times, which resulted in a two-year delay to receiving the payment, and then a very large back-dated payment, with severe implications for their financial situation.

Very stressful… the mortgage was very high. We had to keep pushing to get answers… The forms went missing. We had to do the forms again, then they’d gone to different departments, and they had problems tracking them down….it took a while – Cohort 1, Male, 35 to 44, Average.

Recipients in Cohort 2 often commented that they felt the application only being available via post was not very practical, and believed it meant they had to wait longer to receive their first payment.

The whole process should have been easier rather than relying on the post, and [they] could have made the process a lot quicker if [it was] online – Cohort 2, Male, 45 to 54, Average claim.

One Cohort 2 recipient mentioned their application had been rejected initially, because DWP believed their mortgage number was invalid, because it looked like a bank account number. On consultation with the lender, and resubmission of an unchanged form with a post-it attached confirming the lender view that the account number was correct, it was accepted. Other recipients (as well as lenders, see the Lender Annex) mentioned having forms rejected initially, but they were often uncertain of why.

Awaiting payment

Putting this into context in terms of the overall impact of delays on receiving payment, the quantitative survey indicated that half of recipients (48%) agreed that the time it took between their SMI application and receiving first payment was acceptable, with one-quarter (25%) disagreeing.

Sub-groups of recipients that were more likely[footnote 23] to find the time taken between their SMI application and their first payment as unacceptable included:

- Those who earned less than £5,000 per year (44%)

- Cohort 2 recipients (43%)

- UC recipients (36%)

There was a mixed response from both Cohort 1 and Cohort 2 around their feelings on how long it took to get the first payment. Although many did not have any problems, a substantial number recalled that they felt the payment could have come through a lot quicker, and having to wait the length they did led to anxieties and made their financial situation worse. Along with not knowing if their application had been accepted or not, they felt there could have been better communication around when they would receive the payment, to reduce stress.

In all it took 7 months to receive payment. Had to borrow money from a friend of the family to avoid losing the house and was on anti-depressants; felt really demotivated, vulnerable, scared – Cohort 2, Male, 45 to 54, Average claim.

While waiting for the payment, those that said it took too long, said they had to rely on others for financial support such as family and friends, so that they didn’t go into arrears with their mortgage payment.

3.2 Receiving SMI

3.21 Receiving funds

SMI payments are usually sent directly to the lender, and typically issued on the same day as their primary benefit payments, which for legacy benefits is every 28 days. This caused some difficulties for some recipients interviewed, since this schedule does not match mortgage payments, which are levied every calendar month and may require payment at a specific time, requiring some recipients to periodically change their monthly payment date with their lender so that they recognise the SMI payment, rather than requesting the full amount from them. For SMI recipients on UC, payments are monthly, and so the issue of synchronising mortgage and benefit payments can occur only once, at the start of the loan.

Some felt that having money go straight to their lender was beneficial to them, as they felt the money could end up being spent on other bills if it went straight to them.

They pay it straight to the mortgage company, which is even better, because that way you know, if it was to come to me and there was a bill, it may sort of go on that – Cohort 2, male, 55 to 64, large claim.

Across Cohorts 1 and 2, there was a mix of experience about how smoothly SMI payments were made. For the most part, this happened automatically, and payments were correct. But there were instances across both cohorts where recipients described issues arising with payments that needed to be resolved. For example, changing interest rates meant that underpayments needed to be resolved, or payments needing to be manually adjusted by lenders.

That bit of it was a little bit of a nightmare – I literally had to speak to the lender several times – Cohort 1, Male, 45 to 54, Average claim.

For some, the lack of communication around the paper application process proved problematic as it meant that payments were sometimes being made by DWP, but lenders were not able to allocate them to recipients due to a lack of awareness of whose account they should be allocated to. This caused delays, sometimes resulting in lenders continuing to demand the full payment of the mortgage from the SMI recipient.

This impacted recipients’ credit scores, and resulted in administrative work to rectify. For example, one recipient had to speak to their lender after each SMI payment was made, until they were able to establish what the correct direct debit should be. This took 3 months. In one case a respondent found it easier to change the date in the month at which their mortgage was paid to suit the date DWP had chosen to make the loan payment.

Those that did have communication with their lender, typically because of complications with the SMI payment. Although few reported obstructive or hostile lenders, it was quite frequent that lenders did not know what to do with payment and were initially confused by it.

Respondents said this normally required a lot of back and forth with their lender to sort the issue. Although their experience was rare, one respondent had 2 mortgages, and at the time of interview was still unable to get the second mortgage lender to accept their SMI as payment:

[The lender] wouldn’t help me, they just refused to accept it, and I wish they had been more understanding, but unfortunately, I had a person that wasn’t very understanding – Cohort 2, Female, 35 to 44, Average claim.

3.22 Changes during the claim

Communication around ongoing claims

Many recipients interviewed said they didn’t receive any ongoing DWP contact regarding SMI. Some of these recipients felt that statements from DWP about their SMI payments would have been useful. There were many instances of recipients saying they believed that there would have been communications from DWP, but they had not received anything directly.

Some described how they would have liked to know how much their SMI payment would be prior to receiving it, especially where there were delays to their payments and they were incurring further arrears. Some mentioned how a statement would help them know where they are with SMI.

I don’t know how it’s working, because I haven’t, I’m not sure how to access any sort of statement to look at how the interest is being paid – Cohort 2, Female, 35 to 44, Average claim.

There were, however, instances of letters from DWP being sent detailing SMI payments made, and one recipient recalled a letter mentioning changes of interest rate. When received, recipients generally felt this communication had been clear.

Across both Cohorts 1 and 2, some recipients mentioned communications around payments, where mistakes had been made. This was usually from DWP to the lender, but could also be from DWP to the recipient. For example, one recipient described how there had initially been some misunderstanding about the changing interest payment (meaning it was underpaid at the start). This recipient received a letter from DWP explaining how payments would work.

Interest rate changes

There was little awareness of how the rate of SMI DWP pay is calculated and when it changes. Where interviewees were aware, they mentioned receiving a letter on an annual basis detailing changes to interest rates.

The variable nature of SMI payments relative to their mortgage could be a source of anxiety for recipients, and something they felt was out of their control.

In Cohort 2, numerous recipients talked about how the broader rise in interest rates had affected them. For most, it had had a detrimental effect as their payments increased, sometimes dramatically:

Definitely… if you go back to before 2 or 3 years ago, I was only paying £480 pounds a month…then it went up to £1,380 pounds a month… it was a steep rise – Cohort 2, Male, 55 to 64, Large claim.

However, some recipients were not immediately affected as they had previously secured longer term fixed rates of up to 7 years, insulating them from the immediate effect of interest rate rises. There was a group of Cohort 1 recipients who felt that SMI interest rates had not kept up with their mortgage interest rate as it increased:

My mortgage payments went up from about £400 to nearly £1,000 per month, but the SMI hardly changed – Cohort 1, Female, 45-54, Large claim.

3.3 Implications for policy

RQ4. What are recipients’ experiences of navigating the SMI system?

It is important not to overstate issues with the process; recipients’ experiences were often positive, and they found the help from SMI invaluable. Many found the process straightforward and, in those cases, tended not to comment much on it.

However, a substantial number experienced significant difficulties in:

- Obtaining the form in a reasonable timeframe, especially through the UC journal

- Completing the form with enough confidence to be assured of a positive outcome

- Receiving timely approval for the form, most often due to forms being lost in the post

Recipients most often suggested the process could be moved online to reduce these problems; however, issues in the existing process could also be addressed separately.

RQ11. How, and to what extent, does the scheme prevent arrears and possessions?

The only element of this research question relevant to this chapter is that payments are made directly to lenders. While this seems an effective approach, the mechanism could be improved. Recipient interviews suggested lenders often had difficulty consistently identifying the payment as for their mortgage, with many needing extended or repeated discussions with lenders about the logistics of mortgage payment with SMI. However, this was a matter of time and discussion; there were no cases found where SMI payment to lenders was unsuccessful.

4. Impact of SMI

This chapter explores the impact of SMI on recipients. Most recipients are happy with SMI and feel it has had a positive impact on their lives; many said they would lose their home without it. There are groups, however, who feel SMI is having a negative effect; they may be benefiting less from SMI, principally if they are not receiving sufficient funds (due to interest rate increases, or capital limits) to avoid either severe hardship or losing their home, as well as a smaller group who have, or have had, misunderstandings of SMI leading to either ongoing worries (some unfounded) or negative outcomes.

4.1 Understanding SMI

4.11 Recipient understanding

How SMI repayment works

Regarding how the loan is paid back, across Cohorts 1 and 2, there was awareness that the loan would have to be paid back. Not everyone understood clearly how the loan would be claimed back from their estate after their death. Some were worried that their SMI loan might exceed the remaining equity in their property, and that they would end up both homeless and in debt to DWP or their lender. Both of these situations should not in fact arise with SMI.

A handful of interviewees had other misperceptions regarding SMI, believing that their children would inherit the debt, while some seemed unaware that a debt had been secured on their property. A lack of understanding of how SMI worked was particularly pronounced among people in Cohort 1 who had been transferred directly from SMI as a benefit.

April 2023 changes

Generally, respondents were not aware of the April 2023 changes to the eligibility rules for SMI, and a small number said the changes would have an impact on their behaviour. However, a change that did seem to be appreciated by recipients was the changes in wait times.

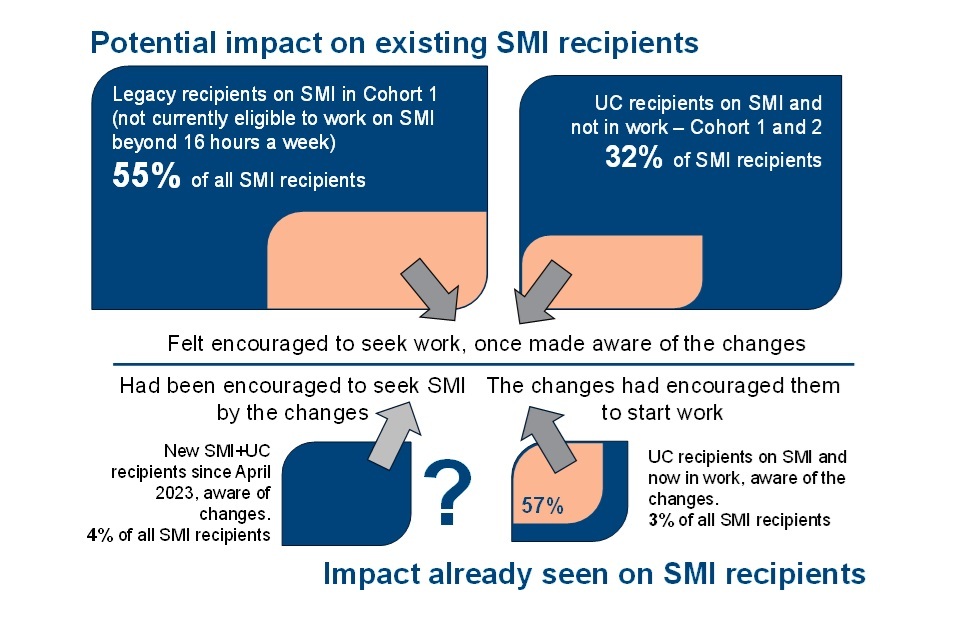

Three quarters (75%) of survey respondents were not aware that UC recipients were now allowed to work without losing their SMI eligibility, with 20% saying that they were aware. Awareness was higher[footnote 24] amongst Cohort 2 recipients (37%) and UC recipients (28%).

Four in 5 SMI recipients on UC (80%) were not aware of the rule changes regarding reducing the qualifying period length from 9 months to 3 months, with 17% being aware. The proportion of respondents aware was higher amongst Cohort 2 than Cohort 1 (24% vs. 14%).