Group-based child sexual exploitation characteristics of offending (accessible version)

Updated 23 December 2021

Home Secretary’s Foreword

This Government has made it our mission to protect the most vulnerable in our society, prevent child sexual abuse, and support victims and survivors to rebuild their lives.

I believe that in order to truly deliver justice for the victims of these horrendous crimes, we need to better understand offending, so that we can take steps to deter, disrupt, and prevent perpetrators.

In my role as Home Secretary, I am dedicated to giving victims a voice and securing justice for them from these abhorrent crimes.

That is why I am publishing this paper on the characteristics of group-based child sexual exploitation, which was prompted by high profile cases of sexual grooming in towns including Rochdale and Rotherham.

An External Reference Group, consisting of independent experts on child sexual exploitation, reviewed and informed this work. While this is a Home Office paper, it owes a great deal to the experts who provided honest, robust and constructive challenge. I am grateful to them for their time and their valuable insight.

The paper sets out the limited available evidence on the characteristics of offenders including how they operate, ethnicity, age, offender networks, as well as the context in which these crimes are often committed, along with implications for frontline responses and for policy development.

Some studies have indicated an over-representation of Asian and Black offenders. However, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the ethnicity of offenders as existing research is limited and data collection is poor.

This is disappointing because community and cultural factors are clearly relevant to understanding and tackling offending. Therefore, a commitment to improve the collection and analysis of data on group-based child sexual exploitation, including in relation to characteristics of offenders such as ethnicity and other factors, will be included in the forthcoming Tackling Child Sexual Abuse Strategy.

Victims and survivors of these abhorrent crimes have told me how they were let down by the state in the name of political correctness. What happened to these children remains one of the biggest stains on our country’s conscience. I am determined to ensure the government, law enforcement and other partners better understand any community and cultural factors relevant to tackling offending – helping us to safeguard children from abuse, deliver justice for victims and survivors, and restore the public’s confidence in the criminal justice system’s ability to confront these repulsive crimes.

Rt Hon. Priti Patel MP

Home Secretary

A note on the role of our External Reference Group

1. Child sexual exploitation (CSE) is a complex and sensitive issue, and the Home Office wanted to ensure this paper was informed by experts with a variety of perspectives and experience. To this end, the Home Office has consulted with an External Reference Group (ERG) while developing the paper. The aim of the ERG was to provide expert advice, scrutiny, and constructive challenge on this paper to ensure that it reflects as accurate a picture as possible of what is known about group-based child sexual exploitation offending,

2. The Home Office sought to develop this paper with due sensitivity and consideration to the experiences of victims and survivors, and a further aim of consultation with the ERG was to ensure that this was reflected in the paper. We are also committed to reflecting the voices of victims and survivors in broader policy development around child sexual abuse (CSA). As such, we have engaged children and young people, adult survivors, and specialist victim organisations in the development of the Tackling Child Sexual Abuse Strategy, which will include a series of specific commitments in relation to victim support.

3. The ERG was made up of experts on child sexual exploitation and abuse across a range of sectors, including representatives of victims and survivors, law enforcement, academia, the third sector, and parliamentarians. Decisions on who should be invited to participate in the ERG were taken by the Home Office. The full list of ERG members can be found at Annex A. Scrutiny by the ERG took place in parallel to the literature review that underpins this paper being peer-reviewed by two independent academics.

4. During the development of this paper, members of the ERG have generously provided ongoing written and verbal guidance to the Home Office on its content and findings. The group met (online) three times to discuss iterations of the paper. The ERG’s comments have proved invaluable in shaping it into a document that sets out the full extent of our current, collective knowledge on this topic, as well as setting direction for areas of future work. The ERG had an advisory role in the development of this paper, and as such all comments from the ERG were considered carefully, but not all were taken onboard. The final paper is ultimately a Home Office product and does not reflect the position of all ERG members.

5. Throughout their discussions, ERG members were clear that group-based CSE is an important issue that warrants significant government attention. However, they recognised that this is a complex and nuanced area. The group recognised the difficulties in defining group-based CSE, particularly as a form of abuse that is distinct from other types of CSE and child sexual abuse more generally. The group agreed that these definitional challenges contribute to a lack of robust research and data in the public domain on group-based CSE. It was also highlighted that much of the evidence available is now quite old and therefore is unlikely to represent current thinking and understanding of group-based CSE. The ERG was broadly supportive of the aims of this paper in trying to achieve a rounded picture of the nature of offending with a mix of data, research and more illustrative detail from case studies and local reviews.

6. ERG members felt that more work would be needed to develop the insights in this paper, which is focused on the available evidence, into a more tangible and practical product for practitioners to use on a day-to-day basis. The group stressed the importance of prevention of this type of offending in addition to investigation and disruption. Members felt that prevention activities need to be tailored to local and community contexts, and that central government needed to work with and support local partners to develop both prevention and disruption strategies that are place- based. In light of the paper’s findings, the Home Office has committed to updating and expanding its Child Exploitation Disruption Toolkit.

7. The intention of the work that informed this paper was to improve understanding of the characteristics of offending, including ethnicity, but placing this understanding in the context of the experiences of victims and survivors has been a central consideration throughout. Members of the ERG suggested that the best way to reflect this emphasis in the paper would be to describe who is affected by child sexual exploitation, and their experiences, including direct quotes. This can be found at paragraphs 50-57.

8. The group expressed differing views in relation to the scope of the paper, including how tightly drawn the definition of group-based CSE should be for the purposes of this paper. Some members felt that the paper needed to position group-based CSE more clearly in the context of wider CSA, and highlighted the risk that a narrow focus on CSE by groups could contribute to failures to recognise and tackle other forms of CSA and CSE that have received less attention.

9. The ERG also did not reach consensus around how the evidence should be presented, particularly with regard to cultural and community contexts. While this has been a central consideration both in the development of the paper and the research that informed it, the available evidence is weak and robust data is scarce. Some, but not all, members of the group wanted to see more explicit detail on manifestations of group-based CSE when perpetrated by offenders from certain communities, particularly Pakistani communities, given the involvement of Pakistani-ethnic offenders in a number of high-profile cases and the recognised need for specific responses to specific threats. In finalising the paper, we have sought to be as specific as we can be, despite the lack of available evidence on cultural drivers in particular.

10. We are profoundly grateful to the members of the ERG for the time and thought that they have contributed to the development of this paper.

Executive summary

11. This paper considers child sexual exploitation (CSE) perpetrated by groups, a form of child sexual abuse characterised by multiple interconnected offenders grooming and sexually exploiting children. This includes forms of offending commonly referred to as ‘street grooming’ or ‘grooming gangs’. Group-based CSE has been the subject of major investigations, attracting significant public concern and highlighting shocking state failures that have caused untold hurt to victims, their families and communities.

12. Before 2010, the evidence on the nature of group-based child sexual exploitation came from a small number of significant cases. Over the last decade there has been a shift in public understanding and recognition of child sexual abuse, coupled with a surge in law enforcement activity. Investigations into group-based child sexual exploitation in Telford, Rochdale, Rotherham, Oxford, Bristol, Newcastle, North Wales and other parts of the country have attracted considerable media and public interest. These high-profile cases have brought the issue of sexual exploitation of children by groups out of the shadows, although there is still much more work to do to fully understand this form of offending, given significant under- reporting.

13. To inform the national policy response the Home Office has assimilated, and continues to gather learning from, these cases to consolidate its understanding of CSE offending by groups as part of routine policy development. Officials have completed a review of published evidence, conducted interviews with police officers across England and Wales, and have undertaken desk-based research to assess the quality of data and evidence in relation to group-based CSE. This paper sets out the key findings from these strands of work, which were not initially intended for publication, but which we felt would be helpful in tackling this form of offending on the ground. The paper also includes additional insights from independent reports and investigations in places like Rotherham, Rochdale and Northumbria, as well as illustrative case studies at page 40.

14. The primary aim of this paper is to present the best available evidence on the characteristics of this form of offending at an aggregated national level. The way in which group-based child sexual exploitation manifests within different local areas varies significantly, and it is therefore important for partners to have a robust, shared profile of the local threat. In order to help with this, we have also included some of the implications of our work for local agencies.

Key findings

15. All forms of child sexual abuse are under-reported and the evidence on which we base these findings is limited to the cases we know about. Given that the majority of people who are sexually abused do not tell anyone at the time (see paragraph 58), and that some disclosures are not recorded, we are aware that there are aspects and dimensions to this kind of offending that are not covered in the literature or in any of the case studies we have considered.

16. Based on what we do know, the characteristics of offenders in group-based CSE include that they are predominantly but not exclusively male[footnote 1] and are often older than sexual offenders in street gangs, but younger than lone child sexual offenders. In many cases, offenders are under the age of thirty, but in some cases they are much older.[footnote 2]

17. A number of high-profile cases - including the offending in Rotherham investigated by Professor Alexis Jay,[footnote 3] the Rochdale group convicted as a result of Operation Span, and convictions in Telford – have mainly involved men of Pakistani ethnicity. Beyond specific high-profile cases, the academic literature highlights significant limitations to what can be said about links between ethnicity and this form of offending. Research has found that group-based CSE offenders are most commonly White.[footnote 4] Some studies suggest an over-representation of Black and Asian offenders relative to the demographics of national populations.[footnote 5] However, it is not possible to conclude that this is representative of all group-based CSE offending. This is due to issues such as data quality problems, the way the samples were selected in studies, and the potential for bias and inaccuracies in the way that ethnicity data is collected.[footnote 6] During our conversations with police forces, we have found that in the operations reflected, offender groups come from diverse backgrounds, with each group being broadly ethnically homogenous. However, there are cases where offenders within groups come from different backgrounds.[footnote 7]

18. Motivations differ between offenders, but a sexual interest in children is not always the predominant motive. Financial gain and a desire for sexual gratification are common motives and misogyny and disregard for women and girls may further enable the abuse.[footnote 8] The group dynamic can have a role in creating an environment in which offenders believe they can act with impunity, in exacerbating disregard for victims, and in drawing others into offending behaviour.[footnote 9] Investigators told us that they believe offenders may seek to distance themselves from their victims to reduce their inhibition to offending. This could include ‘othering’ people, either in relation to the fact that they are from a different community or in relation to their gender, where misogynistic attitudes are at play.

19. Offender networks tend to be loosely interconnected, with some members more central to the group and others more peripheral. Some groups are more tightly connected.[footnote 10] Networks tend to be based on pre-existing social connections, including work and family.[footnote 11]

20. There is no common structure to offender networks and modus operandi vary. Some frequent elements of offending include: initiating contact with victims in the shared local area; grooming the victims and significant adults (such as parents) into believing the victim is in a legitimate relationship with the offender (the so-called ‘boyfriend’ model); and the use of parties, drugs and alcohol to reduce victims’ resistance and willingness to report.[footnote 12] Abuse often takes place in private or commercial locations, but it has also been seen to take place in public spaces.[footnote 13]

21. This kind of abuse can and will happen when groups of (largely) men have access to potential victims in circumstances where they feel able to act with impunity, and where the group dynamic means perpetrators both give each other ‘permission’ and spur one another on to greater depravity and harm. This can happen anywhere. The precise nature of the abuse will vary from one instance to the next, shaped by the specific context and by the attitudes of the perpetrators.

Implications for policy

22. Key insights about the nature of group-based CSE that could inform a local response include: the localised nature of offending, whereby contact with potential victims tends to take place in locations frequented by offenders (in the course of their employment and/or social activity) and where safeguards around victims are lower; the proliferation of offending behaviour through social networks and the potential role of offenders within the group in persuading or coercing others to participate; the need for appropriate multi-agency safeguarding and support for victims; and the need for consistent recording practices and information-sharing between agencies to inform local threat profiles.

23. Local agencies should fully understand the local context and facilitate strategic engagement between communities, agencies, businesses and charities to both understand the profile of offending and identify opportunities to disrupt it. Group offending is particularly complex and requires relentless disruption and well- resourced, victim-centred investigations. Safeguarding should also take into account the local context, identifying and building safeguards around vulnerable children, and intervening in the situations or environments in which they are likely to be targeted. Local multi-agency safeguarding partnerships are well-placed to do this in a strategic way. Victims and survivors should have access to the right support whenever and however they seek it out, and whether or not they choose to engage with the criminal justice process.

24. The Government’s Tackling Child Sexual Abuse Strategy will set out what we are doing at a national level to tackle group-based child sexual exploitation, as well as all other forms of child sexual abuse, by preventing and tackling offending, protecting children and young people and supporting victims and survivors to rebuild their lives.

Scope and Purpose

25. This paper considers the evidence base for characteristics of group-based CSE offending in the community. This is a form of child sexual abuse characterised by multiple offenders with connections to one another grooming and sexually exploiting children. Although aspects of the grooming and abuse can take place online, this report focuses on offline offending and excludes groups of child sex offenders that operate exclusively online. The paper also excludes groups of offenders who operate predominantly in private spaces such as schools and care homes, focusing instead on models of offending taking place within the community, sometimes called ‘street grooming’, ‘gang grooming’ or ‘localised grooming’. We have focused primarily on offending by adults against children, although some of the cases we examined involved offenders who were under the age of eighteen.

26. To inform the national policy response the Home Office has assimilated, and continues to gather learning from, these cases to consolidate our understanding of CSE offending by groups. As part of this work, Home Office officials have:

- completed a review of published evidence, looking specifically and exclusively at group-based CSE (published alongside this paper);

- spoken to a number of officers across England and Wales who were dealing with police operations investigating child sexual exploitation perpetrated by groups of offenders to draw out commonalities and variations between different manifestations of group-based CSE. These cases included some high-profile cases that had been profiled in the media, and others that had not been widely covered; and

- undertaken desk-based research and assessed the quality of data and evidence in relation to group-based CSE.

27. In the course of this work, it became clear that some of the insight gathered could be valuable to agencies striving to detect, prevent, and disrupt group-based CSE, and to improving the public’s understanding of this type of exploitation. This paper therefore sets out the key findings from the Home Office’s three strands of work. The paper also includes additional insights from independent reports and investigations in places like Rotherham, Rochdale and Northumbria, as well as illustrative case studies.

28. The primary aim of this paper is therefore to present as comprehensive an assessment as possible of this form of abuse, using the best available evidence. We intend for this paper to be useful to leaders and practitioners wishing to better understand the characteristics of group-based offending in order to develop targeted responses. The paper outlines the main challenges local and national agencies face in responding to group-based CSE, sets out implications for national and local responses, and highlights necessary future work in this area, including new research.

The Tackling Child Sexual Abuse Strategy

29. Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse. The government’s response to all forms of child sexual abuse, including the offending described in this paper, will be set out in a new national strategy, soon to be published. This paper does not therefore attempt to describe the national policy response to this form of offending in full, but some relevant initiatives in this area are described from paragraph 131.

30. These include:

- Building on the Government’s Child Exploitation Disruption Toolkit, drawing on insight from successful investigations and from this paper, and providing strategic guidance to local areas on profiling, preventing, and disrupting this form of offending.

- Continuing to support local interventions to combat exploitation through the Prevention Programme delivered by The Children’s Society, and working with other sectors, particularly businesses, to create safer local spaces.

- Encouraging focused engagement with communities to deter potential offenders and support bystanders in spotting the signs of exploitation and reporting their concerns.

- Supporting work within policing to improve the analysis of intelligence around organised exploitation and using it to inform law enforcement operations.

Definitions

Child sexual abuse and exploitation

31. The definition of child sexual abuse (CSA) is set out in the Department for Education’s statutory guidance ‘Working Together to Safeguard Children 2018’:

[Child sexual abuse] involves forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, not necessarily involving a high level of violence, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. The activities may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (for example, rape or oral sex) or non- penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching outside of clothing. They may also include non-contact activities, such as involving children in looking at, or in the production of, sexual images, watching sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming a child in preparation for abuse. Sexual abuse can take place online, and technology can be used to facilitate offline abuse. Sexual abuse is not solely perpetrated by adult males. Women can also commit acts of sexual abuse, as can other children.

32. For the purposes of this paper, the definition of child sexual exploitation (CSE) as a subset of child sexual abuse (CSA) is adopted. This definition – copied below – was set out by the Department for Education in 2017, and is included in ‘Working Together 2018’. In the course of discussing this paper, members of the External Reference Group expressed differing views on the utility of the concept of ‘exchange’ as expressed in this definition and the possibility that ‘exchange’ suggests complicity on the part of the victim.

Child sexual exploitation is a form of child sexual abuse. It occurs where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and/or (b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the offender or facilitator. The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology.

Grooming, groups and gangs

33. As well as the need to define ‘CSE’, the terms ‘group’ and ‘gang’ can also cause inconsistency. While the term ‘grooming gang’ is widely used in the media, as well as in some literature, it is an ambiguous term that has no official definition. It is important to understand what is meant by grooming, and to distinguish between groups and gangs.

34. Grooming is ‘a process by which a person prepares a child, significant adults and the environment for the abuse of the child’.[footnote 14] Grooming is a feature of many different forms of exploitation and abuse, including criminal exploitation, by which children are manipulated and coerced into committing crimes, whether online, in the family environment, or by persons in positions of trust, as well as being a common feature of group-based exploitation.

35. The Office of the Children’s Commissioner has distinguished groups and gangs as follows:

Gangs are relatively durable, predominantly street-based social groups of children, young people and, not infrequently, young adults who see themselves, and are seen by others, as affiliates of a discrete, named group who (1) engage in a range of criminal activity and violence; (2) identify or lay claim to territory (3) have some form of identifying structural feature; and (4) are in conflict with similar groups. Groups are two or more people of any age, connected through formal or informal associations or networks, including, but not exclusive to, friendship groups.[footnote 15]

36. Many groups described in the media as ‘grooming gangs’ do not fit the above definition of a gang. Their members do not see themselves as affiliates of a discrete, named group, they are not in conflict with similar groups of people (i.e. other gangs), and the group of associates does not have a clear structure (such as hierarchies or individuals who play central coordinating roles). Instead (as described in paragraphs 101-108) so called ‘grooming gangs’ tend to be groups of men who are loosely connected, or who only have strong connections with a small number of other members of the group. They do not necessarily enter into the conflict that is often seen between ‘street’ gangs, nor do they always have associations with other, similar groups of people.

37. For the avoidance of doubt, our work has focused on child sexual exploitation perpetrated by groups, as per the above definition, which therefore includes what commentators sometimes describe as ‘grooming gangs’. We have not focused on offender groups operating in institutions or online, but as definitions vary and forms of offending often overlap, some of the sources used may include those and other multiple-offender cases of child sexual abuse. We have focused primarily on offending by adults against children, although some of the cases we examined involved offenders who were under the age of eighteen.

38. Where we have used the term ‘network’, this is to describe a group in terms of its size, structure and connectivity, and the relationships between its members, rather than to denote a specific type of group, or something distinct from a group.

39. The Home Office-funded Centre of expertise on child sexual abuse (CSA Centre) published a typology of child sexual offending in March of this year.[footnote 16] This empirical study, based on analysis of case files, identifies child sexual abuse through groups as one of nine offending types. The typology report explains that each type reflects a distinct combination of characteristics, though it recognises that there are overlaps between the types. The typology also notes that sexual abuse through groups may include contact abuse and/or the creation/sharing of images and recognises the inherent overlap between ‘online’ and ‘offline’. This resonates with some of the insight gained through our conversations with police and highlights the overlap that exists between contact and online offences in group-based CSE offending.

Offenders, victims, modus operandi

40. The term ‘offender’ is used in this paper to describe individuals who perpetrate child sexual exploitation and abuse. In the course of our work, we have considered ongoing police operations that may not have reached trial, in which individuals suspected of abuse have been described as ‘suspects’ or ‘nominals’. For simplicity we use the term ‘offender’ throughout, even in reference to those cases.

41. We use the term ‘victim’ to describe a person who has been sexually exploited. Some people who have experienced sexual exploitation prefer the term ‘survivor,’ and the term ‘complainant’ is used in the criminal justice system when accusations have not been proven. For simplicity, we use the term ‘victim’ throughout.

42. ‘Modus operandi’ or ‘mode of operating’ refers to the broad ways in which offenders carry out their activities. In the context of this paper it refers to the ways in which offenders approach, abuse and exploit, and retain control over their victims.

Approach

43. In recent years, the Home Office has been exploring the characteristics of group- based CSE through a number of discrete projects carried out in the context of routine policy development.

44. We reviewed published literature, including academic and grey literature, on group- based CSE, conducting an evidence assessment to identify key texts on this topic (published alongside this paper). This was used to understand what is known about the prevalence of group-based CSE, the offending behaviours and strategies seen in group-based CSE, the characteristics and make up of offender networks, and characteristics of victims and offenders. However, we recognise that some of this evidence was published some time ago and may not reflect current circumstances.

45. We have also interviewed police officers and safeguarding professionals across the country who have worked on a range of group-based CSE operations to understand more about their perceptions of the offenders and victims involved, their understanding of modus operandi, and the practicalities of investigating such cases. We looked at ten operations dating from 2013 to 2018, covering six of the ten police regions in England and Wales, and interviewed 26 professionals. Further detail of our approach to this project is at Annex B.

46. We have explored existing administrative data collections, including police data, to see what could be learned from those. As will be discussed throughout this paper, available data on group-based CSE is limited (as with all types of CSA), making it difficult to make confident, quantifiable judgements about this type of offending. We are working with the police to improve the data in this area.

47. It is important to note that the above projects were commissioned to inform policy decisions, not as part of a public-facing inquiry or review. These activities would have been designed differently if they had been initiated with the express intention of publication. For example, interviews were carried out under confidentiality agreements, yielding valuable but often operationally and personally sensitive insight. While we have developed this paper as a means of bringing together the key insights gathered in the course of the above activity, and with the kind agreement of the participants, it has been necessary to remove some details to avoid jeopardising live operations and to protect the identity of victims.

48. This paper also reflects insights from serious case reviews, independent reports and investigations into specific cases, such as the Jay Report on Rotherham. Towards the end of this paper we have also set out four case studies to help illustrate some of the wider findings raised in the paper around offender and victims’ characteristics and how group-based child sexual exploitation manifests.

49. We have also considered the work of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA), established by the Government in 2015. The Inquiry investigates the extent to which institutions in England and Wales have failed in their duty to protect children from sexual abuse and exploitation. As part of its work programme, the Inquiry set up an investigation into institutional responses to child sexual exploitation by organised networks. To support its investigation, the Inquiry also commissioned specialist research agency TONIC to undertake research into the motivations and behaviours of perpetrators who operate as part of organised groups.[footnote 17] As the Inquiry’s research was carried out concurrently with the Home Office’s work in this area, it would have been inappropriate for the Government to duplicate this effort while it was ongoing. We have given careful consideration to TONIC’s research findings and will consider the Inquiry’s recommendations in due course.

Who is affected by child sexual exploitation?

I do not think the public understand, and I do not think I would if I had not gone through it myself. I think it is very hard to understand fully.

A Young Person – Real Voices [footnote 18]

50. The work that has informed this paper was aimed at better understanding the characteristics of group-based child sexual exploitation offenders and offending, and this paper reflects that emphasis. Our ultimate aim is to prevent sexual exploitation, and to ensure better safeguarding and support for victims and survivors. We consider it important therefore to present these findings in the context of a broader understanding of who experiences child sexual exploitation and how it affects them.

51. It is important to be clear that vulnerability is not the reason that abuse occurs, and victims of sexual abuse and exploitation are not responsible for the harm they experience. Moreover, while research identifies some characteristics that are common to victims of CSE, we recognise that abuse and exploitation are not uniquely experienced by people who share those characteristics. As with offenders, data on the characteristics of victims of CSE is limited by the fact that there are many cases that do not come to the attention of the authorities, and data is only collected on those who have been identified.[footnote 19] Our understanding of victims’ experiences is therefore likely to be incomplete, and more reflective of those who do report than those who do not. We know, for instance, that boys, children with disabilities and children of minority ethnic backgrounds all face specific barriers to disclosure.[footnote 20]

52. Noting these important qualifications, research shows that the victims of child sexual exploitation who are identified are most commonly female[footnote 21] (although males may be less likely to be identified as victims[footnote 22]) and aged 14-17 years old, with a peak at around 14-15 years old.[footnote 23] This is a slightly older and narrower age profile than is seen across child sexual abuse more widely. The factors which have the clearest documented association with the risk of child sexual exploitation, indicating vulnerabilities that abusers might seek to exploit, include: being in care; experiencing episodes of going missing; and having a learning disability.[footnote 24] Other documented factors which may be exploited by abusers include drug/alcohol dependency, mental health issues, and experience of previous abuse. [footnote 25] These factors also appear consistently across high-profile cases, and in varying degrees in the cases we explored with investigators. Some of these risk factors also act as barriers to disclosure, meaning much abuse is never identified.

53. While it is clear that there are things that make some children more vulnerable than others, there is no factor which makes any group of children uniquely vulnerable. Although awareness of vulnerability can be helpful, it can also contribute to stereotypes about what a victim of child sexual exploitation looks like, with the consequence that victims who differ from that picture are overlooked or unwilling to come forward in the belief that they will not be believed. Throughout the cases we have examined, through published reports and serious case reviews, and in our interviews with investigators, we have seen many examples of children who do not have any of the above characteristics but have experienced exploitation and abuse. In our interviews, some officers told us they have seen victims from a seemingly ‘stable’ home, who are doing well at school, and who have simply been in the ‘wrong place at the wrong time’.

54. People who have experienced exploitation and abuse are clear that they want and need services to support them. Young people have reported feeling judged and not believed when they approached services, and have expressed clearly how important it was to them to be treated with sensitivity and respect.[footnote 26] People who experience child sexual exploitation need to access a combination of different statutory and non-statutory services at different stages of their recovery, but it is important that they receive a coherent and consistent service.

All young people can be worked with. It’s about finding the right worker… [and the professional] staying strong, staying tough and going along the roller-coaster ride with the young person… The worker needs to always be there to support you whenever you need it… It doesn’t go away overnight. It takes time.

Quote from a youth consultation event on CSE Practice Guidance[footnote 27]

55. Discussions with professionals have flagged the importance and challenges of good engagement with victims. Police report how difficult it can be to encourage disclosures from victims and the amount of work and specialist skill needed to gain victims’ trust to secure them. In some cases, there are so many potential victims that police do not have the capacity to follow up all leads. Professionals should understand that the need to provide consistent support exists irrespective of whether victims ultimately choose to disclose.

The more you push, the more young people close up. When you push people, they don’t want to speak to you. So don’t push, but equally help people to tell – and help children to help others.

Quote from a youth consultation event on CSE Practice Guidance[footnote 28]

56. Officers reported their sensitivity to the need to avoid retraumatising the victim, and its being particularly important when approaching victims of non-recent offending. Even in these cases, victims may fear repercussions from offenders, may have moved away from the area and so be difficult to locate, or may be reluctant to revisit an extremely difficult aspect of their past. All CSE, but complex group-based CSE cases in particular, can result in a long period of waiting for the victim, with some reporting that the court process can be more traumatic than the exploitation itself. [footnote 29]

57. These and other considerations relating to the appropriate provision of support services for children and young people are explored more fully in the Government’s Tackling Child Sexual Abuse Strategy.

Prevalence

58. It is difficult to determine the scale and prevalence of CSA due to under-reporting and under-recording. The Crime Survey for England and Wales estimates that 76% of adults who experienced rape or assault by penetration as children did not tell anyone about their experience at the time.[footnote 30] Looking at police-recorded crime, non- recent cases (i.e. those where the offence was a year or more before it was reported to the police) accounted for 34% of all sexual offences against children recorded by the police in the year to March 2019.[footnote 31] [footnote 32] A recent Joint Targeted Area Inspection (JTAI) report has demonstrated the difficulties professionals face in identifying CSA.[footnote 33] This means that the majority of abuse remains hidden. Through gathering data from a number of surveys asking children and adults about their experiences of child sexual abuse, the CSA Centre estimated that, at a minimum, 15% of girls and 5% of boys experience some form of child sexual abuse.[footnote 34]

59. Over recent years, we have seen steep increases in the reporting of child sexual abuse offences to the police. In the year to March 2020, over 83,300 child sexual abuse offences[footnote 35] were recorded by police, an increase of nearly 270% since 2013.[footnote 36] In the same period there were approximately 8,200 charges for CSA offences.[footnote 37]

60. But it remains difficult to identify (group-based) CSE offences within these data sources, in part due to the categorisation and classification of offences. Those perpetrating group-based CSE are charged and convicted with a whole range of offences, from rape and other sexual assault, to indecent imagery offences, through to trafficking offences.[footnote 38]

61. It is therefore hard to get a sense of the scale of CSE. To improve this, a ‘CSE flag’ was introduced to police recorded crime. This shows that in the year to March 2020 around 10,500 crimes were flagged as being CSE-related. However, this is still likely to be an underestimate, as we know the flag is not consistently used across forces.[footnote 39] It should also be noted that the CSE flag is applicable to all types of CSE, and so still does not enable identification of group-based offending specifically.

62. In July, the National Police Chiefs Council (NPCC) lead for group-based CSE (Chief Constable Mark Collins) commissioned a return from forces on their live group-based CSE investigations (including those progressing through the criminal justice system). This exercise provides a snapshot for June 2020 of CSE[footnote 40] investigations involving two or more offenders. It should be noted that, given the tight turn-around on the commission, returns were only received from 32 forces across England, Wales and Scotland. Due to the way data is stored in police systems it was also not possible to exclude forms of group-based CSE that are outside of the scope of this paper, such as those in institutions, or that took place predominantly online.

63. Where forces were able to provide data, many of the returns did not have complete data for all categories, and the way in which data was abstracted from free text cells may have impacted on the data quality. Extracting this data typically involves resource-intensive manual searching of police systems to identify cases. As can be seen from the examples included in this paper, the true picture of offending can emerge gradually as the investigation continues, meaning that cases may not initially be identified as group-based CSE.

64. That said, the returns from forces provide some useful high-level insights about activity at the national level, in that:

a. Most forces that submitted returns reported having at least one live group- based CSE investigation; and

b. There are over 70 live investigations that involve group-based CSE across England, Wales and Scotland, although this number very likely would have been higher if returns had been received from all forces.

Challenges around data

65. Throughout our work on group-based CSE, and in common with other forms of CSA, a consistent challenge has been the paucity of data. This lack of good quality data limits what can be known about the characteristics of offenders, victims and offending behaviour, as data is only available on the small proportion of known cases. It is therefore important that the data that is available is of high quality and shared effectively between different agencies. Several factors contribute to this.

66. Under-reporting - CSE, like CSA more generally, remains a hidden crime. CSA as a whole is under-reported and under-recorded, and therefore it is likely that group- based CSE, as a subset of CSA, is also under-reported. Many victims cannot or do not disclose their abuse to the authorities, and nor is it identified by safeguarding professionals, so the abuse remains uncovered. A number of these findings were reflected in our conversations with law enforcement. They identified challenges to victims reporting, including victims not realising that they are in abusive relationships, victims themselves being involved in criminal activities and therefore being afraid to come forward, and victims fearing repercussions, for themselves or their families and friends, if they report.

67. Definitional issues - In our work to improve the recording and collation of data on group-based child sexual exploitation, we have found that a lack of clarity around definitions of groups, gangs, and sexual exploitation contribute to inconsistencies in recording. There remains confusion amongst practitioners around what constitutes group-based CSE.

68. Inconsistent practice - Even where CSE is identified, the data relating to CSE is still often inconsistently recorded. For example, research has found that information is often recorded inconsistently about victims and offenders, with different agencies focusing on different aspects when recording information. Police data in particular suffers from a lack of consistency in recording.

Implications for local partners

69. Evidential challenges and a lack of good-quality data limits what can be known about this form of offending. Whilst many local areas are already producing local threat profiles, regular and consistent data collection and sharing between local, regional and national agencies could help address some of the intelligence gaps and improve our knowledge and understanding of the scale and nature of this offending at all levels.

70. More consistent data collection and recording processes, as well as the sharing of these between agencies, could lead to improved responses and awareness. Studies have found that police forces are more able to tackle abuse when they have the data to allow them to build a good understanding of the local threat and a proactive multi-agency process in place to tackle it. Data recording problems can have a negative effect on a force’s response to CSE and make it difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of different strategies and responses.

Characteristics of Offenders

Age, gender, social status

Key findings:

- People who perpetrate group-based CSE:

- are predominantly, but not exclusively, male; and

- are often under the age of 30, and tend to be older than child sexual offenders who operate in gangs, but younger than those operating alone.

- People from a range of different social backgrounds perpetrate group-based CSE. Some have stable lives, others are more chaotic.

- In many cases offenders within a group share occupations and lifestyles, which provides the opportunity to target, groom, and abuse their victims.

71. All forms of child sexual abuse are under-reported[footnote 41] and it is reasonable to assume that there are many incidents of group-based CSE that have not been identified. This limits how certain we can be about common characteristics of offenders. What we do know is based on those offenders who have been identified and apprehended. In our discussions with investigating officers we encountered several cases that came to the attention of authorities because bystanders saw signs that recalled other cases in the media (“like a scene from Three Girls”). While this provides some reassurance that forms of CSE that were once overlooked are now being recognised, it also suggests a possibility that similarities between the cases we know about might reflect a reporting bias, and cases that present differently could be going unrecognised and unreported.

72. Based on our work so far, including a review of the published literature and work with police, we have identified some predominant characteristics among offenders, although these are not universally shared. Beyond these basic characteristics, there is considerable variation. Individuals committing group-based CSE have appeared to be:

a. predominantly, but not exclusively, male;[footnote 42]

b. generally older than those operating in gangs, but younger than those operating alone;[footnote 43] and

c. often under the age of 30, although some groups do involve much older offenders.[footnote 44]

73. Among the police operations we looked at, we saw offenders from a range of backgrounds - some stable middle-class professionals, some of whom are married, whilst others have more chaotic lifestyles. Some were known to the police for minor offences, but officers told us it was extremely rare for them to have a record of sexual offending.

74. Numerous high-profile cases have featured offenders employed in the night-time economy: The Jay Report on Rotherham highlighted the role of taxis in offending[footnote 45]; the Operation Span case in Rochdale focused on takeaways. As described in paragraphs 112-113, initial contact between victims and offenders in this form of offending is often situational, taking place in locations frequented by offenders, with low levels of safeguarding. The representation of offenders employed in the night- time economy is in keeping with this.

Ethnicity

Key findings:

- Research on offender ethnicity is limited, and tends to rely on poor quality data. It is therefore difficult to draw conclusions about differences in ethnicity of offenders, but it is likely that no one community or culture is uniquely predisposed to offending.

- A number of studies have indicated an over-representation of Asian and Black offenders in group-based CSE. Most of the same studies show that the majority of offenders are White.

- Community and cultural factors are, however, relevant to understanding and tackling offending. An approach to deterring, disrupting, and preventing offending that is sensitive to the communities in which offending occurs is needed.

75. There is a limited amount of research looking at the ethnicity of perpetrators of group-based CSE, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions about whether or not certain ethnicities are over-represented in this type of offending. What research there is tends to rely on poor-quality data, with issues in a number of areas:

- Data in this space is reliant on ‘known’ or identified offending behaviour, therefore limiting our understanding of group-based CSE in its entirety.

- Law enforcement data can be particularly vulnerable to bias, in terms of those cases that come to the attention of the authorities, and this can impact on the generalisability of such data.[footnote 46] This can also lead to greater attention being paid to certain types of offenders, making that data more readily identified and recorded.[footnote 47]

- Police-collected data on ethnicity uses broad categories and requires the police to assign an ethnicity rather than it being self-reported by offenders. Data is therefore not always accurate; Berelowitz et al. (2012) observed cases of offenders being initially classed as ‘Asian’ but actually coming from other backgrounds, such as White British or Afghan.

- Data on ethnicity are not routinely or consistently collected by police forces and other agencies. As set out below, many research and evidence collections have a lot of missing or incomplete data.

76. A number of papers have reported on offender ethnicity in group-based CSE, typically as part of wider research in this space. Findings from these are summarised below:

a. CEOP (2011) undertook a data collection with police forces, children’s services and specialist providers from the voluntary sector, looking at those allegedly involved in ‘street grooming’ and CSE. Data was returned on approximately 2,300 possible offenders, but approximately 1,100 were excluded from analysis due to a lack of basic information. In the remaining 1,200 cases, ethnicity data was unknown for 38% of them. Where data was available 30% of offenders were White, while 28% were Asian. Due to the amount of missing data, both basic offender information and ethnicity specifically, these figures should be treated with caution.

b. Berelowitz et al. (2012) collected data from a range of agencies including local authorities, police forces and voluntary sector organisations on individuals known to be exploiting children. Around 1,500 individuals were identified, but there was no data on ethnicity for 21% of them. Where data was available, ‘White’ was the largest category. However, it should be noted that this data relates to a time period at least ten years ago when many agencies were less familiar with CSE. This work also did not distinguish between groups and gangs.

c. In 2013 CEOP undertook a second piece of work in this space. Data was requested from all police forces in England and Wales on contact CSA, and responses were received from 31. Of the 52 groups where data provided was useable, half of the groups consisted of all Asian offenders, 11 were all White offenders, 4 were all Black, and 2 were exclusively Arab. There were nine groups where offenders came from a mix of ethnic backgrounds. Looking at the offenders across all groups, of the 306 offenders 75% were Asian. However, as with CEOP (2011) these figures should be treated with caution due to the amount of missing data.

d. The Children’s Commissioner for England carried out work in 2014 looking at police data on CSE offenders (Berelowitz et al., 2015). Data was provided by 19 out of 43 police forces, showing nearly 4,000 offenders, 1,200 of whom were involved in group-based CSE. This study found that 42% were White or White British, 17% were Black or Black British, 14% were Asian or Asian British, and 4% had another ethnicity. No data on ethnicity was recorded in 22% of cases. As above (Berelowitz et al., 2012), it should be noted that when this work was carried out when many agencies were less familiar with CSE, and very little was recognised or recorded about this kind of offence or offender by police at the time.

e. Lastly, the Police Foundation (Skidmore, 2016) looked at group-based CSE in Bristol, and found that those from ethnic minority backgrounds were over- represented compared to the local area. However, they note that this is likely magnified by skewed and incomplete data.

77. In addition, returns from police forces in July 2020 (see paragraph 62) suggested that the nationalities and ethnicities of offenders and suspects in group-based CSE investigations varied considerably, including American, Angolan, Bangladeshi, Bengali, British, Bulgarian, Congolese, Dutch, Eritrean, Indian, Iranian, Jamaican, Lithuanian, Pakistani, Portuguese, Somali, Syrian, and Zimbabwean. Unfortunately, the data was not sufficiently robust to allow for comparisons to be made in terms of proportions across these groups.

78. It is common for offender groups to be largely ethnically homogenous, although there are cases where offenders within groups come from different backgrounds.[footnote 48] This was reflected in the police operations we examined, as well as many high- profile cases, and is likely a consequence of the way offending behaviour proliferates through pre-existing social connections. We also spoke to investigators in one area who were pursuing a number of different groups, each mainly based within a different community in the local area.

79. In light of the lack of reliable evidence from published data, Home Office Analysis and Insight undertook exploratory analysis of unpublished data from the Police National Computer (PNC) to determine whether a relationship between child sexual exploitation and ethnicity could be determined.

80. This analysis demonstrated that the existing data would not answer the question of the relationship between ethnicity and child sexual exploitation. First, it was not possible to use ethnicity data because of the amount of cases in which it is missing. Second, CSE offences can be recorded under a number of different offence codes (including more general offence codes, such as sexual assault) and so it was not possible to isolate these offences in the data. Third, the co-offending flag is only applied in a minority of cases, so when combined with ethnicity data, numbers were too small for meaningful analysis. While exploration of the nationality data was interesting, it did not address the relationship between group-based CSE offending and ethnicity and therefore adds little to our understanding. These shortcomings were in line with published data on ethnicity, as described above.

81. While some of the research set out above suggests that there are high numbers of offenders of Asian or Black ethnicities committing group-based CSE offences, it is not possible to say whether these groups are over-represented in this type of offending. As set out in paragraph 75, research to date has relied on poor-quality data with a number of weaknesses. It remains difficult to compare the make-up of the offender population with the local demography of certain areas, in order to make fully informed assessments of whether some groups are over-represented. Based on the existing evidence, and our understanding of the flaws in the existing data, it seems most likely that the ethnicity of group-based CSE offenders is in line with CSA more generally and with the general population, with the majority of offenders being White.

82. While there is therefore no evidence to suggest that efforts to identify and prevent group-based CSE offending should be limited to focusing on one particular community or culture, this does not mean that cultural characteristics of offender groups are irrelevant or should be ignored by local agencies. The significance of social networks to offending and the prevalence of ethnically and demographically homogenous groups suggests that an approach to deterring, disrupting, and preventing offending that is highly sensitive to the communities in which offending occurs is needed. This has been highlighted in numerous reports, notably the Overview Report of the serious case review of the Rochdale case[footnote 49], which notes:

What is absent is any evidence that practitioners attempted to understand why the fact that the men were ‘Asian’ might in fact have been relevant and legitimate for consideration… The degree to which workers understood the communities they worked in may also have contributed to the failure to recognise the unusual patterns of interaction between these two groups.

83. In her report on Rotherham, Professor Jay stresses the need for engagement with communities to be meaningful, and to reach into every part of the community, stating that there was ‘too much reliance by agencies on traditional community leaders as being the primary conduit of communication with the Pakistani-heritage community,’ with several women from that community feeling ‘disenfranchised by this and thought it was a barrier to people coming forward to talk about CSE’.[footnote 50]

Motivations and enablers

Key findings

- People who perpetrate group-based CSE are likely to be motivated by a complex combination of personal, cultural, societal, and opportunistic factors.

- There is an important distinction to be made between factors that drive the desire to offend and factors that disinhibit individuals from offending.

- The role of the group is significant in enabling and driving individuals to offend.

84. What motivates offenders to commit CSE is likely to differ between groups and even between members of the same group. A specific sexual interest in children is not always the predominant motive.

85. Some studies have found that offenders are more commonly unemployed or in lower-paying jobs than the general population, suggesting that offenders may be motivated by a desire to profit from the exploitation.[footnote 51] Research commissioned by IICSA found that some perpetrators were aware of abuse being coordinated for money.[footnote 52] The CSA Centre’s typology also includes CSA that is arranged and perpetrated for payment, highlighting that as well as sellers profiting from the abuse, there are buyers whose motives will be different.[footnote 53] However, research about financial gain is limited – some victims may not even be aware of any financial transactions taking place[footnote 54] and arrested offenders are unlikely to reveal to law enforcement that there was a financial aspect to their offending.[footnote 55] Some research suggests that some financially-motivated groups are involved in drug dealing and organised crime, with CSE being seen an extra way to profit.[footnote 56]

86. Additionally, offenders sometimes have previous general criminal convictions, suggesting a readiness to engage in criminal activity.[footnote 57] Individual offenders have reported being involved in other violent crimes and drug dealing offences.[footnote 58] Other studies suggest that many offenders derive satisfaction from coercive and manipulative behaviour.[footnote 59]

87. A recent report commissioned by IICSA[footnote 60] considers the self-expressed motivations of a number of convicted child sexual exploitation offenders who offended with others, gathered through interviews in custody. There are some similarities to the perceptions of investigators; some offenders discussed their offending as being part of a wider chaotic and hedonistic lifestyle. The self-expressed motivations of offenders also highlight the significance of the group in driving offending, and that peer pressure can reinforce negative messages within groups, leading to more widespread abuse. Offenders discussed seeking approval or validation from their peers, and the notion of ‘kudos’ has been highlighted in other studies.[footnote 61]

88. Some offenders reported being groomed or emotionally coerced by other offenders to commit child sexual exploitation and other crimes.[footnote 62] Other research has found evidence of young people who commit CSE offences having histories of abuse themselves, emotional deficits or existing vulnerabilities which draw them towards offending behaviour.[footnote 63] Some offenders themselves stated that their offending behaviour is the result of a ‘culmination of dysfunctions,’ including emotional and mental health issues, as well as situational factors.[footnote 64]

89. Studies have indicated that societal and cultural issues around misogyny may also be an enabling factor. Objectification of women in society has been suggested as a reason why violence against girls may be normalised and accepted. One study, which mostly involved offenders from ethnic minorities, suggested several potential factors driving CSE offenders in the cases they examined. These included societal influence as part of a culture of misogyny and objectification, cultural patriarchal issues, lack of challenge in the community and a lack of sex education.[footnote 65] The perceived drivers of offending tended to vary across the cases we examined, but some common themes highlighted by investigators included: opportunism, misogyny and disregard for women, and a desire for sexual gratification. The suggestion that patriarchal structures had a role in creating attitudes that enabled offending also emerged.

90. In several of the cases we examined, offenders and victims appeared largely to come from different local communities, and officers suggested that disregard for victims from outside their own community may be an enabling factor for offenders. Empathy with victims is a likely barrier to offending behaviour, and disregard for victims - whether through misogyny or so-called ‘othering’ - enables offenders to overcome this barrier. There are notable parallels with sexual offending in other contexts, including some online sexual offending and child sexual offenders who travel to offend overseas. We have also seen cases of group-based CSE involving offending against members of one’s own community.

91. A number of reports have also noted that offenders appeared to operate with a sense of impunity. In her report of CSE following her inspection of Rotherham, Louise Casey attributed this to a ‘credulity gap’, where failure by agencies to grasp the scale, nature, and severity of offending enabled offenders to think they could not be touched.[footnote 66] The Serious Case Review of offending in Northumbria, investigated in Operation Sanctuary, referred to the ‘arrogance and persistence’ of perpetrators.[footnote 67] Offenders have been shown to try to justify their behaviours, and often believe that they will not get caught.[footnote 68] Investigators we interviewed in another area noted that offenders would tell young teenagers what they were doing. It was not clear whether this was in order for the offenders to get ‘kudos’ or whether the offenders felt untouchable because they had been offending for such a long period of time. Investigators also noticed that because the abuse had gone unaddressed for many years, this had created a sense of resignation in local communities, which further contributed to the feeling of impunity among offenders.

92. Group dynamics may also have a role in creating this sense of impunity and enabling the criminal behaviour of individual offenders. There is some evidence to suggest that the better connected within a group an offender is, the more likely they are to offend. This could be due to the normalisation of abuse to the individual, as well as increased opportunities to offend.[footnote 69] Offenders within a group are often seen to provide each other with things that enable the offending behaviour, such as alcohol, transport for victims, or a location for abuse to occur.[footnote 70] Beyond these tangible benefits of group involvement, there may be types of sociocultural or situational factors, such as cultural norms and lack of challenge to their offending behaviour, that serve to perpetuate and exacerbate abusive behaviour.[footnote 71] Group dynamics can exacerbate attitudes of hypermasculinity and belief in male dominance, which are also thought to play a significant role in sexual offending.[footnote 72] These factors have also been linked to sexual violence by multiple perpetrators in other situations, such as US fraternities or street gangs.[footnote 73]

93. There may be a distinction to be made between factors that drive the desire to offend and factors that disinhibit individuals from offending. Wanting sexual gratification, money, and status could drive the desire to offend, while misogyny and disregard for the victim, or the use of alcohol and drugs, may play a part in reducing the perpetrator’s inhibitions. A possible further distinction is between attitudes that are genuinely held by offenders and those that are adopted as a means of justifying their behaviour to themselves. This is an important distinction if enabling attitudes are to be tackled in work to prevent and deter offending, but the distinction is often not clear, even to offenders themselves.

94. In summary, it is likely that a combination of factors come together to create the conditions in which an individual is motivated and able to offend. Some of these will be cultural, some situational, and the involvement of group dynamics adds a further layer of complexity. A range of factors are almost certainly involved. This was highlighted in the serious case review in the Rochdale case:

A simplistic view that the mere fact of being ‘Asian’ is in itself explanatory of their behaviour, is dangerous not only because it is unjust and offensive to the wider community who share a South East Asian heritage. It is also dangerous because such simplistic presumptions represent a meaningless over-generalisation, that is positively unhelpful if we wish to understand why these men behaved in the way they did and therefore help to protect other potential victims. Such an approach fails to consider the combination of personal, cultural and opportunistic factors that are understood to create the conditions for sexual offending.[footnote 74]

Implications for local partners

95. Third-sector organisations are already working in partnership with local and national agencies to deter people from committing these horrific crimes. We have seen a number of forces across the country embarking on partnership with prevention campaigns, like Stop It Now!, to stop people from committing child sex offences and encourage them to seek support if they have concerns about their own behaviour or that of others known to them.

96. Prevention campaigns - coupled with education about consent and healthy relationships - are at the heart of early intervention efforts. For example, partners may draw on or design public campaigns such as the Disrespect NoBody campaign, first launched in 2017. The campaign aims to help young people aged 12 -18 to understand what a healthy relationship is and what consent means in their relationship, to prevent them from becoming either perpetrators or victims of abusive relationships. Building an awareness of the law about consent and what constitutes consent could raise internal inhibitions to offending.

97. Prevention and disruption efforts will require different approaches that recognise the distinction between factors that drive the desire to offend and factors that disinhibit individuals from offending. It is also important to recognise the evidence that those who commit sexual exploitation as part of a group may not be motivated by a sexual interest in children, and interventions should reflect other factors such as possible financial motivations, attitudes towards women and girls, and the influence of the group. Given the tendency for offending to proliferate through social connections within communities, agencies should consider whether these interventions could be undertaken in partnership with community-based professionals and organisations.

98. Additionally, relentless disruption is a key pillar of the 2018 Serious and Organised Crime Strategy[footnote 75] and should be at the centre of local responses to group-based child sexual exploitation. The evidence tells us that a common characteristic of offenders is a sense of entitlement or impunity, and an indiscriminate readiness to engage in criminal activity when opportunity presents itself. We know that offending behaviour can proliferate through social networks and that offenders can draw others into offending. We also know that investigations can be lengthy and that offenders may pose a risk while investigations are underway. For all of these reasons, local agencies should use every available tool to disrupt and interrupt the proliferation of offending alongside efforts to safeguard victims and prosecute offenders.

99. Disruption sends a clear message to perpetrators about the consequences of their actions and deters others from committing offences. During our conversations with forces, we have heard how multi-agency approaches led to imaginative disruption techniques. This included, for example: acting swiftly on intelligence linked to other forms of criminal activity, such as drug dealing or fraud; working with Local Authorities to visit or close licensed premises used for CSE; issuing civil orders; pursuing driving offences and revoking driving licences; and ensuring public spaces where offending could happen are patrolled or monitored. Sharing best practice and information between agencies of what works to prevent offending at regional and national levels is a helpful way to assist other areas in their response.

100. Published toolkits, such as the Home Office’s ‘Child Exploitation Disruption Toolkit’ and NWG’s ‘Criminal, Civil and Partnership Disruption Options for Perpetrators of Child and Adult Victims of Exploitation’ set out a range of options that safeguarding professionals may access to pursue offenders and safeguard victims through a multi-agency approach.

Characteristics of Offender Networks

Key findings:

- Offender networks are often loosely interconnected and based around existing social connections (which means they are often broadly homogenous in age, ethnic background and socioeconomic status).

- Networks of offenders vary considerably in size, from two to tens of offenders.

- These sprawling networks - often not highly-organised – can pose significant investigative challenges for the police.

101. There is no universal structure of organisation among networks involved in child sexual exploitation. It is frequently the case that networks are not well organised at all, with no clear hierarchy or demarcation of roles within the group. Some of the more organised networks we have seen in the cases we have examined have been within groups involved in wider criminal activities, such as drug supply.

102. Offender networks are often based on pre-existing social connections.[footnote 76] Given that they reflect these social networks, groups of offenders are often broadly uniform in age, ethnic background and socioeconomic status.[footnote 77] Similarly, reflective of the social networks on which they are often based, it is common for offender networks to appear fairly loose, although there are instances of closer networks.

103. The experiences of the police investigators we have spoken to echo these findings. Investigators in some cases explained that offenders knew one another from work. In some, they were friends or lived in shared accommodation. In others, connections were familial. Finally, some links between offenders were simply based on the fact that they belonged to a relatively small ethnic community.

104. Studies indicate that networks of offenders vary considerably in size, from two to tens of offenders.[footnote 78] However, the boundaries of a network may not always be clear; while some individuals might be well-connected within a network, there may be peripheral members who are less connected to the rest of the group.[footnote 79] The tenuous connections between individuals, coupled with under-reporting and the challenges of identifying offenders, mean that the extent of an offender network can be challenging for authorities to trace.

105. There is no evidence to suggest that there exists a highly organised national network, acting in a coordinated way and connecting different groups of offenders in different areas, either from the literature or from our work with the police.

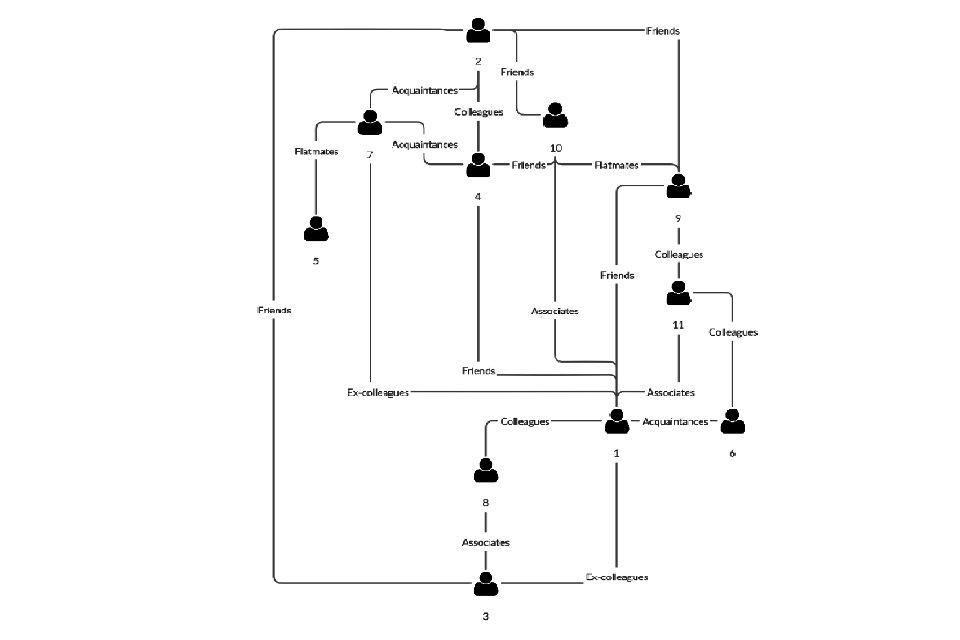

Figure 1 - Representation of offender network from Operation Span (Cockbain, 2018)

106. Figure 1, which represents an offender network in Rochdale, investigated in Operation Span, shows the extent to which offenders can be connected through existing social bonds and demonstrates that networks may not be tightly interconnected, with some individuals in the network (e.g. #1) more central and others (e.g. #5) on the periphery.[footnote 80]

107. The variation in the interconnectedness and organisation of networks, and particularly the fact that it is common for networks to be loosely connected and not organised, has implications for the identification of complex group-based offending. People looking within a local area for evidence of a highly-organised “grooming gang”, such as exists in the public consciousness, and not finding it, might conclude - incorrectly - that group-based CSE is not taking place. It is important that the different ways CSE can manifest itself are understood, to enable identification and reporting by both professionals and members of the public.

108. These often large, sprawling, loose networks pose significant challenges for investigating and prosecuting group-based CSE. Investigating officers may be confronted with a situation where offending behaviour has proliferated through social networks over many years. New victim disclosures lead to the identification of new offenders, which leads to the identification of new victims. These victims in turn identify new offenders who may have no connection to the others.

Implications for local partners

109. Investigators tell us that dealing with these sometimes sprawling networks with loose connections can often result in extremely complex investigations and trials that are resource-intensive and take a long time to complete. As well as the implications for police and wider criminal justice system resources, the complexity and the duration of the investigation can be painful for victims (see paragraph 56).

110. There already exists guidance for large-scale and complex investigations to be managed on the major enquiry system, HOLMES. Ensuring that a complex CSE investigation is supported by effective case management software like HOLMES assists in managing intelligence, identifying offender networks, and carrying out de- confliction checks.

111. We also know from HMICFRS inspection reports that those cases allocated to specialist investigation teams with training and understanding of CSE have a higher proportion of positive outcomes. And we have heard from law enforcement partners that early engagement with CPS prosecutors, who have specialist knowledge of CSE cases and an understanding of the impact of trauma on victims and survivors, supports a successful

Characteristics of Offending

Key findings:

- Despite significant variance, there are some similarities in the way groups operate:

- Initial contact with victims sometimes happens in public spaces, including those that offenders have access to because of their line of work;

- Victims are then groomed in multiple ways, including via the exchange of commodities such as alcohol, drugs and other gifts;

- An offender often grooms the victim into believing they are in a legitimate relationship before coercing them to have sex with the offender and others in the group. A victim may then be taken to a party or gathering and expected to have sex with other offenders.

- Abuse often takes place in private residences, including ‘party houses’;

- Victims can be coerced into introducing peers to the offender network.

112. We have seen some variety between offender groups in terms of operating models, but we have also seen similarities. Whilst there is evidence that some victims are deliberately targeted, the initial contact between offenders and victims has been seen too often to be opportunistic and occur in their shared local area, and the abuse also most often goes on to take place in this shared locality.[footnote 81]