Government response to the call for views on supply chain cyber security

Published 15 November 2021

1. Executive Summary

The Supply Chain Cyber Security Call for Views sought insights from industry to inform the government’s understanding of supply chain cyber security[footnote 1]. In particular, it sought feedback on how organisations currently manage supply chain cyber security risk and what additional government support would enable organisations to do this more effectively. Respondents were also invited to provide feedback on a proposed framework for managed service provider security. This document brings together the collective insights that have been gathered through this consultation.

Findings from Part 1 confirm that the key barriers to effective supply chain cyber security risk management are: low recognition of supplier cyber security risk, limited visibility into supply chains, insufficient tools to evaluate supplier cyber security risk and limitations to taking action due to structural imbalances. Supporting organisations to overcome these barriers calls for a range of interventions from the government. This includes advice and guidance, improving access to a skilled workforce and the right products and services to manage risk, and working with influential market actors to drive prioritisation of supply chain cyber security risk management across the economy.

Many of the respondents are using the National Cyber Security Centre’s (NCSC) Supply Chain Security Guidance and Supplier Assurance Questions. Respondents provided examples of good practice they currently follow, and identified new areas of risk not currently covered by existing guidance. However, it is clear that the barriers identified by respondents make implementation of the guidance challenging, and that further support is needed.

There is a growing market for technology platforms which support organisations to manage supplier risk, and respondents viewed these as the most effective commercial tool for managing supply chain cyber security risk. The government is committed to supporting this market.

The findings also indicated a need for further government support to improve supply chain cyber security risk management outcomes, both in the provision of additional advice guidance, and by adopting a more interventionist approach to improve resilience across supply chains, with regulation perceived to be ‘very effective’ by more respondents than any other suggested intervention.

Part 2 highlighted that managed service providers are vitally important net contributors and critical enablers of the modern UK economy. While the managed services industry plays a positive and critical role in building systemic cyber resilience in the UK, respondents identified systemic dependence on a group of the most critical providers which carry a level of risk that needs to be managed proactively. Response to the Call for Views also highlighted the difficulty that customers often face in accessing information about managed service provider cyber security. In identifying policy solutions, some respondents underlined the challenge associated with the scope of proposed definitions while others underscored the need to consider other digital technologies such as cloud and software.

The majority of respondents deemed the NCSC’s Cyber Assessment Framework principles to be applicable to cyber security resilience of managed service providers, indicating that these principles should be considered when establishing a future security baseline or assurance frameworks. Respondents also reacted positively to proposed policy implementation options such as education and awareness campaigns, certification or assurance marks, minimum requirements in public procurement, legislation, targeted regulatory guidance, and international engagement.

The support for all of these policy options reinforces the need for a range of interventions. Therefore, the government will, as part of the forthcoming National Cyber Strategy, continue to work with industry experts to develop a set of policy solutions aimed at increasing the cyber security resilience of digital solutions. The interventions prioritised by the government will include legislative work to ensure that managed service providers undertake reasonable and proportionate cyber security measures. In recognition of the global nature of digital supply chains, the government will prioritise engagement with international partners and organisations to foster a joined-up international approach to securing providers of digital services such as managed services, cloud and software.

2. Introduction

The Department of Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) launched a Call for Views in May 2021 to seek industry feedback and insights to help inform the government’s understanding of supply chain cyber security.

The Call for Views focused on further understanding two aspects of supply chain cyber security:

- Part 1 sought input on how organisations across the market manage supply chain cyber security risk and what additional government intervention would enable organisations to do this more effectively.

- Part 2 sought input on the suitability of a proposed framework for Managed Service Provider security and how this framework could most appropriately be implemented to ensure adequate baseline security to manage the risks associated with managed service providers.

The Call for Views was open for eight weeks, and was publicised on gov.uk as well as across a range of trade body notice boards.

2.1 Summary of responses

In total, 214 responses were received through the Call for Views between 17 May and 26 July 2021. This included 24 responses from individuals, 96 from organisations, and 94 unspecified responses.

Respondents were able to respond via an online survey, or via email. The Call for Views included a mix of open and closed questions. Respondents were not required to answer all questions. All questions and the accompanying percentages are reported based on the number of respondents that answered that individual question. This is detailed in the description of each question through each section of this government response. Where results do not sum to 100%, this may be due to computer rounding or multiple responses.

For open response questions, every response was reviewed and, while not every point that was made by each respondent can be reflected, responses were coded to identify common themes.

Alongside the Call for Views survey, DCMS undertook a number of virtual industry roundtables to allow a more in depth discussion and collect verbal feedback from a range of industry stakeholders. These events included a Ministerial roundtable and several industry led workshops, hosted by sector representative bodies. Input collected from these workshops has been analysed to help identify and reinforce key themes that arose from written responses, as well as any additional key themes.

This government response provides an overview of the findings we have collated through the analysis of the Call for Views responses and industry roundtables.

3. Call for views part one: supply chain risk management

3.1 A: Barriers to effective supplier cyber security risk management

The Call for Views set out our current understanding of the main barriers preventing organisations from more effectively managing supplier cyber security risk:

- Low recognition of supplier risk

- Limited visibility into supply chains

- Insufficient expertise to evaluate supplier cyber security risk

- Insufficient tools to evaluate supplier cyber security risk

- Limitations to taking action due to structural imbalances

Respondents were asked how much of a barrier each of these represented, and whether they faced any additional barriers to effective supplier cyber risk management..

Q1. How much of a barrier do you think each of the following are to effective supplier cyber security risk management?

Figure 1: Severity of barriers to effective supplier cyber security risk management

Almost all respondents to this question agreed that limited visibility in supply chains is somewhat of a barrier, or a severe barrier to effective supplier cyber security risk management (98%). This was the most likely of the five barriers to be seen as a severe barrier (67%). Nine in ten respondents thought that low recognition of supplier risk and inefficient expertise to evaluate supplier cyber security risk are barriers (90% and 89% respectively). Inefficient tools or assurance mechanisms to evaluate supplier cyber security risk was seen to be a barrier by 86%.

Fewer, although still a majority, saw ‘limitations to taking action due to structural imbalance’ to be a barrier (73% said this was either somewhat of a barrier or a severe barrier). The proportion of respondents who did not know whether this was a barrier was higher than for the other barriers (at 13%), suggesting uncertainty about this issue rather than respondents disagreeing that this is a barrier for organisations.

Q2 and Q3. Are there any additional barriers preventing organisations from effectively managing supplier cyber security risk that have not been captured above?

Two thirds who answered this question (65% of 171 respondents) stated that they believe there to be additional barriers preventing organisations from effectively managing supplier cyber security risk. A description of additional barriers was provided by 99 respondents.

One of the most common themes related to the barrier of ‘insufficient expertise to evaluate supplier cyber security risk’. Respondents detailed the limitation of skills and experience, with some noting that this can be a particular challenge for smaller organisations. Respondents noted the lack of skilled staff with an understanding of cyber security risk in general makes it difficult to have staff in place to advise on managing supplier cyber security risks more specifically.

Linked to the barrier ‘inefficient tools or assurance mechanisms to evaluate supplier cyber security risk’, limitations in the standards and frameworks landscape was a frequently mentioned barrier. Respondents cited a lack of a common standard for organisations to be measured against (with mentions of existing standard and frameworks such as ISO 270001, Cyber Assessment Framework, Cyber Essentials and NIST, among others) creating a lack of a cohesive accepted approach or standards for organisations to work towards. Respondents that referenced specific standards often noted that Cyber Essentials was commonly understood as a good way of demonstrating compliance with a minimum baseline. Beyond this baseline, there was confusion for organisations about which standards they should be adhering to, or expecting of suppliers.

A recurrent concern was the inadequacy of assurance questionnaires as a key tool of supply chain cyber security risk management. This was also a common theme of workshop feedback. Respondents noted that questionnaires could be subjective, could be manipulated and required expertise both to answer and interpret responses. The lack of consistency and standardisation increased burden and resulted in duplicated effort. This was often seen as arising from the barrier above around lack of a common standard. However, some respondents also warned against an over-reliance on standards and certifications, which could lead to a reductive approach to managing supply chain cyber security risk.

Resources and prioritsation were further themes mentioned by respondents to the Call for Views. Many mentioned insufficient time or staff resources to be able to review suppliers, while others cited the cost and financial resources this requires. Resource challenges were considered to be exacerbated by the lack of appropriate tools mentioned above. Linked to concerns around the costs of managing supplier risks, prioritisation of supply chain risk management was also seen to be an issue for some. One respondent commented that:

“The cost of cyber security is perceived by some as too expensive, also tight margin business working across multiple sector may consider cost of compliance as too high, i.e. other customers don’t require it and as such the flow through impact on the overall business cost is such that they believe it will make them unaffordable or less affordable in certain sectors / markets.”

A number of respondents cited lack of prioritisation of supply chain risk management among boards or senior management as a barrier, either through lack of understanding of risk, or due to prioritisation of budget and resources elsewhere in the organisation. Some respondents saw this inadequate prioritisation as arising from a lack of information about the impact or costs of cyber security incidents arising from the supply chain.

A range of issues related to the complexity of modern supply chains were also raised, including the lack of alternative suppliers for some products or services, the multiple layers of supply chains, the increasing volume of suppliers, the international nature of supply chains and lack of transparency in supplier relationships.

As a result of these barriers, some respondents argued that harder measures, such as regulation or enforcement for organisations to adhere to a defined standard, would be needed in order to ameliorate the issue of insufficient supply chain risk management.

3.2 Government response

Responses show that the barriers set out in the Call for Views are relevant, and reflect the difficulty and complexity organisations face in managing their supply chain cyber security risk. No single barrier stood out as uniquely challenging, therefore the government will continue to pursue a broad range of policy interventions to address these challenges, as part of the forthcoming National Cyber Strategy.

Prioritisation and incentives

Addressing supply chain cyber security risk requires investment from organisations, and lack of incentive to do so was identified as a significant additional barrier to cyber resilience. It is the responsibility of senior management and boards to prioritise and drive investment in this area. Some respondents suggested regulation was necessary to change behaviour, and this is a lever that is already used in sectors where more stringent controls are essential (please see Part 2 for further reference on future regulatory plans). Alongside regulation, the government will seek to harness influential market agents to drive supply chain cyber security risk management up the agenda, ensuring they have access to appropriate guidance and information about the costs and impact of cyber incidents to strengthen the internal case for investment. Future government engagement will target those professionals and functions that may influence investment decisions within organisations, such as investors, banks and insurers, so that companies throughout the supply chain feel compelled to prioritise cyber security risk management.

Standards and certification

The results highlight that the large number of competing standards and certification products, plus a lack of a commonality in approach, have contributed to the view that available tools for evaluation and assurance were inadequate. The government’s Cyber Essentials Scheme is recognised as providing an accepted baseline for organisations to gain a minimum level of confidence in their suppliers’ cyber security risk posture. The government is therefore considering ways of increasing the uptake of Cyber Essentials across the wider economy so that it becomes a more universally adopted minimum security requirement in supplier contracts. In addition, the government will consider what can be done to clarify and consolidate the standards landscape above this minimum in order to make it a more effective tool for supply chain risk management.

Supply chain oversight

More clarity around different standards and certifications, and their relative merit, could help organisations more easily understand the security controls their suppliers have in place, and begin to address the lack of visibility into supply chains that respondents reported as one of the most significant barriers to effective risk management. Evidence also shows that there are an increasing array of commercial offerings directed at addressing the problem of supply chain oversight (see section D). The government will continue to support innovation and the growth of new startups in the cyber security sector through initiatives such as NCSC for Startups which brings together innovative startups with NCSC technical expertise to solve some of the UK’s most important cyber challenges, including supply chain cyber security risk.

Cyber skills

It is clear that access to skills remains a significant barrier, particularly for smaller organisations with fewer resources. This is reflective of the wider challenge of cyber security skills gaps and shortages in the UK. The government is addressing this challenge through funding mechanisms, working in partnership with further and higher education providers, and establishing formal accreditation for cyber skills through the UK Cyber Security Council. This will give organisations greater access to professionals with the skills to evaluate their suppliers’ cyber security risk posture. The work of the UK Cyber Security Council will also define the skills required by non-cyber professionals, such as procurement teams and security teams, to assess supplier risk throughout the supply chain lifecycle.

3.3 B: Supply Chain cyber security risk Management

The Call for Views asked whether respondents have used the Centre for the Protection of National Infrastructure (CPNI) and NCSC’s Supply Chain Security Guidance, how challenging organisations find it to effectively act on these principles, and asked for examples of good practice for organisations implementing these aspects of supply chain cyber security risk management.

Q4 Have you used the CPNI-NCSC Supply Chain Security Guidance?

Of the respondents who answered the question, half stated that they had used the CPNI and NCSC’s Supply Chain Security Guidance (52% of 157 respondents).

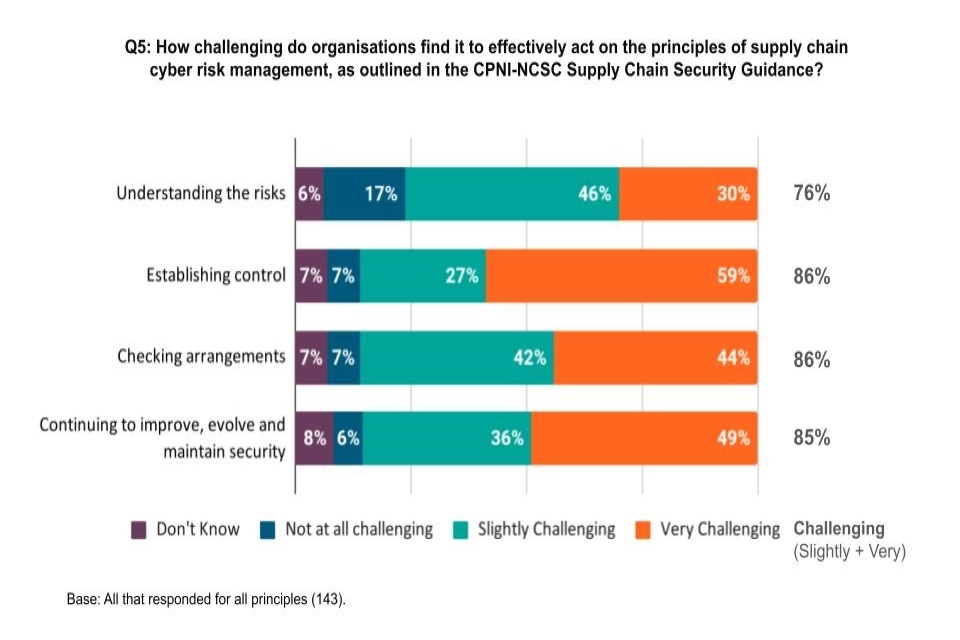

Q5: How challenging do (or would) organisations find it to effectively act on these principles of supply chain cyber security risk management, as outlined in the CPNI-NCSC Supply Chain Security Guidance?

Respondents were asked how challenging organisations find it (or would find it) to effectively act on the principles of supply chain cyber security risk management as outlined in the CPNI - NCSC’s Supply Chain Security Guidance (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Level of challenge for organisations acting on principles of supply chain cyber security risk management

The majority of respondents stated that it is challenging or would be challenging for organisations to effectively act on each of the principles of supply chain risk management.

- ‘Establishing control of supply chains’ was seen to be the most challenging principle for organisations to act on, with 86% saying this was challenging (either slightly or very). Respondents were most likely to say establishing control is very challenging (59%).

- ‘Checking arrangements’ was seen to be challenging by 86% of respondents to this question (very or slightly challenging), with 44% stating this is very challenging.

- ‘Continuing to improve, evolve and maintain security’ was seen to be challenging by 85% of respondents, with half saying that this is very challenging (49%).

- Fewer respondents thought that the principle of ‘Understanding the risks’ was challenging for organisations to effectively act on, although this was still the majority of respondents at 76%. A third (30%) of respondents said it was very challenging for organisations to do this.

Q6. What are examples of good practice for organisations implementing these aspects of supply chain cyber security risk management?

Respondents were asked to provide examples of good practice of organisations implementing each of the four aspects of supply chain cyber security risk management.

Q6(a). Understanding the risk (examples provided by 85 respondents)

The most common example of good practice around understanding risk was the creation of a risk management process or framework. Many respondents also mentioned the importance of creating a risk register as good practice for understanding risk. Some highlighted the need to maintain a register of assets, ensuring that they are aware of their critical assets and what assets suppliers have access to.

Having oversight of the supply chain was also seen to be a key element of understanding risk. Suggestions of good practice included ensuring that there is continual supplier assessment through, for example, ongoing supplier assurance questionnaires and improving supply chain transparency. For some, the use of existing standards and frameworks, such as International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards or Cyber Essentials, were seen to be good practice for organisations in understanding the risks posed by their supply chain.

Use of technology was also highlighted by some as a good practice in understanding supply chain risks. Examples included verification through technology, such as binary scans and deploying real time cyber security risk management tools. Other suggested examples of good practice mentioned by smaller proportions of respondents included analysis of threat intelligence, product risk certification, externally verified certification, prioritisation of risk management over commercial considerations and board-level awareness of cyber security risk.

Q6(b). Establishing control (examples provided by 72 respondents)

Respondents thought it was important to be able to contractually hold suppliers to account on their cyber security and to write mitigations and potential penalties for violations into tendering processes and supplier agreements.

Cooperation between suppliers and customers was seen to be an important element for establishing control for some respondents, as was having the right to audit suppliers written into contractual agreements. Small numbers mentioned the need for independent supplier assurance and verification, supply chain transparency, having oversight of critical suppliers, ongoing supplier management and carrying out annual supplier assurance.

Requiring suppliers to adhere to minimum security requirements was seen by some as good practice for establishing control over supplier risk management. In some cases, respondents thought this should require adherence to existing standards or frameworks, such as Cyber Essentials and ISO 27001.

Q6(c). Checking arrangements (examples provided by 73 respondents)

The most common examples of best practice regarding checking arrangements concerned the auditing of suppliers. Reserving the right to audit suppliers was seen to be important, particularly with on-site checks. Within this, regular auditing and independent auditors were elements recommended by respondents as good practice. Many respondents also stated that it is good practice to have assurance activities built into all contracted terms and conditions.

Supplier reporting of assurance processes, security testing and of incidents were also seen to be good practice. Some mentioned the need for penetration testing as a good practice assurance activity as well as the conducting of vulnerability scans.

Smaller numbers of respondents mentioned a number of other themes including: the importance of technical expertise, requiring adherence/ proof of certificates to standards (e.g. ISO 270001 or Cyber Essentials), use of supplier questionnaires, having a software bill of materials (SBOM)/ asset register and performance incentives for suppliers.

Q6(d). Continuing to improve, evolve and maintain security (examples provided by 70 respondents)

Comments around good practice for improvement largely centred around supplier engagement and working in close partnership with suppliers for continuous improvement.

The second most common theme was ongoing monitoring. Respondents stated that there was a need for regular reviews and meetings with suppliers and that it is important to regularly review to identify changing risks. Some respondents also mentioned the need to incorporate these strategies for continuous improvement into contractual agreements.

Some thought that improvements could be driven through governance, for example by establishing a supply chain governance board to discuss risks, challenges and action plans or regular governance meetings with critical suppliers. Some suggested that supply chain cyber security risk management should be linked to the wider business risk appetite and strategy.

Q7 What additional principles or advice should be included when considering supply chain cyber security risk management? (answered by 66 respondents)

Respondents were asked what additional principles or advice should be included when considering supply chain cyber security risk management.

A prominent theme was having full knowledge and understanding of any given supplier’s risk profile, including senior management having awareness of the risk management for their choice of supplier, categorising suppliers by risk and also engaging them to manage their risk target. On an ongoing basis, things like regular check-ups on supplier risk and advice on how to audit suppliers, or how to also conduct a simple and repeatable assurance process also all received a moderate number of responses.

There were also responses around risk management, such as clearly defining responsibilities for risk management as there can be confusion on the supplier’s exact risk management responsibilities. Additionally, taking a holistic view of risk management that could include reputational or legal issues was also suggested.

3.4 Government response

The NCSC’s Supply Chain Security Guidance is well used by organisations who are seeking to manage supply chain cyber security risk. However, there is still work to be done to ensure that all organisations across the economy are aware of, and are fully utilising, this guidance.

Whilst many of the organisations who responded to the Call for Views are confident in understanding the risks posed by suppliers they find implementing a number of the principles of the CPNI-NCSC guidance challenging. In particular as establishing control over the supply chain, checking arrangements with suppliers, and continuous improvement. It is clear that the barriers identified in Section 1 are important factors which might inhibit organisations from fully implementing CPNI-NCSC guidance. The government is working to alleviate these barriers through the approaches set out in section 1 - improving standards and certification, supply chain oversight and risk management and improved skills.

Respondents identified several areas of good practice across the various principles of supply chain cyber security risk management, such as carrying out regular audits with suppliers, and promoting a culture of sharing threat information and support with suppliers. Whilst good practice will vary by sector and organisation type this information is crucial to helping inform the development of new CPNI-NCSC guidance on managing supply chain cyber security risks. These findings will be incorporated into the development of future iterations of the CPNI-NCSC’s guidance.

3.5 C: Supplier Assurance

Building on the CPNI-NCSC Supply Chain Security Guidance, the NCSC has developed a set of Supplier Assurance Questions designed to guide organisations in their discussions with suppliers and ensure confidence in their cyber security risk management practices. The questions cover the priority areas organisations should consider when assuring their suppliers have appropriate cyber security protocols in place.

This section of the Call for Views explores whether respondents have used or plan to use NCSC’s Supplier Assurance Questions and additional areas of supplier assurance that should be outlined (Figure 3).

Q8. Have you used or do you plan to use the NCSC’s Supplier Assurance Questions?

Q9. Are there any additional areas of supplier assurance that should be outlined?

Figure 3: Whether used or plan to use the NCSC’s Supplier Assurance Questions

Just over half who responded to Question 8 (54%) stated that they either have used or plan to use the NCSC’s Supplier Assurance Questions, demonstrating a relatively high degree of awareness and usage of government guidance in this area among respondents to the Call for Views.

Around half of respondents to Question 9 (49%) believed that there are additional supplier assurance areas that need to be addressed, with only a small number (11%) stating that there are no additional areas to be outlined.

Q10. What additional areas of supplier assurance should be outlined? (answered by 50 respondents)

The most common topic addressed by respondents was Application Security, with supplementary comments around secure software development processes and even security training for software developers.

Some respondents further elaborated on how to establish quality application security. For example, that attention should be paid to implementing a strict command and control environment around application internet activity, and third party penetration testing should be mandatory for any application with inbound or outbound connectivity, where ideally this connectivity is restricted to the control centre with tight user permissions.

Many respondents wrote more broadly about cyber security risk management of suppliers and the need for further guidance for creating an assurance questionnaire, guidance for supplier contracts, or determining compliance with frameworks. Many respondents described further specific elements they would look at as part of their supplier assurance, and how they would use additional risk assessment regimes to supplement questionnaire responses as part of their assurance approach.

3.6 Government response

The NCSC’s Supplier Assurance Questions have become a recognised tool for organisations seeking to gain assurance in their suppliers’ risk posture. This is a positive result.

Respondents highlighted areas, such as application security, not currently covered by the guidance, as well as a broader request for further guidance. The NCSC’s new approach to technology assurance, set out in the recently published Future of Technology Assurance White Paper and a set of technology assurance principles due to be published in the autumn, offer a means to gain confidence in the cyber security of the services and technologies on which the UK relies. DCMS will work with the NCSC to ensure any remaining gaps highlighted by respondents inform the development of these principles, and subsequent iterations of the Supplier Assurance Questions.

3.7 D: Commercial Offerings

There are several existing commercial offerings that can be used by organisations to help with the management of supply chain cyber security risk. However, the market failures that create barriers to supply chain risk management may stifle the uptake of these products.

These products and services that can assist organisations in gaining visibility and control over their supply chain are categorised below and outlined in more detail in the Call for Views.

- Private supplier-assurance companies

- Platforms for supporting supplier risk management

- Supply chain management system providers

- Risk, supply chain and management consultancies

- Suppliers of outsourced procurement services

- Industry cyber security certification schemes.

This section of the Call for Views sought insights on how effective these commercial offerings are in supporting organisations to manage their supplier cyber security risk and sought examples of other effective commercial offerings.

Q11: How effective are the following commercial offerings for managing a supplier’s cyber security risk?

Figure 4: Effectiveness of commercial offerings for managing a supplier’s cyber security risk

Industry cyber security certification schemes were seen to be the most effective, with 87% of respondents to this question stating that these are very effective or somewhat effective. A third of respondents thought certification schemes are very effective (34%). The commercial offerings that were seen to be next most effective were platforms for supporting supplier risk (82% said these are very or slightly effective, with 27% thinking these are very effective).

Around seven in ten respondents to this question thought that each of the following are effective in helping organisations to manage a supplier’s cyber security risk: risk, supply chain and management consultancies (72%), supply chain management system providers (70%) and private supplier assurance (68%). Suppliers of outsourced procurement services were seen to be the least effective of the commercial offerings (55%), with only 9% thinking that they are very effective.

Q12 What additional commercial offerings, not listed above, are effective in supporting organisations with supplier risk management? (suggestions provided by 59 respondents)

Call for Views respondents were asked about any further commercial offerings that they believe are effective in supporting organisations with supplier risk management. Most commonly, respondents provided examples of other platforms for supporting risk management. Examples of other platforms included:

- Procurement and onboarding tools used to automate processes like vendor assessment, security questionnaires, and completing contracts

- Vulnerability rating and monitoring tools which can draw on open source intelligence data and dark web scanning to assess the risk of different suppliers

- Supply chain management platforms that help give organisations visibility over their supply chains and the associated risks (including cyber security risk)

- More general governance and risk management platforms used to manage and provide accountability for identified risks

While there is clearly a growing market of commercial products to support supply chain risk management, responses also reflected challenges posed by this diversity, by crossover between different products and the functions they fulfil, as well as concerns about the efficacy of different tools. There was a general consensus that while technology platforms and other commercial offerings could assist in the management of supply chain cyber security risk, it could not entirely replace the need for organisational understanding of, and engagement with, these risks.

“Whilst you can outsource (and automate) some of the legwork, number crunching, research, audit and review (very effectively in fact), you cannot “outsource” the need to make it all come together and work effectively - whether you do this using internal staff, or external staff who really understand your business, systems, risk and business drivers.”

Respondents often provided examples of existing certification schemes, standard institutes, accreditation bodies or private supplier assurance providers that were considered effective commercial offerings. These included Cyber Essentials, ISO standards (e.g. 270001), PCI DSS, SOC 2 compliance requirements and voluntary certification schemes approved by the ICO and delivered via United Kingdom Accreditation Service (UKAS) accredited bodies.

Many mentioned the limitations of the current commercial offerings available, some mentioned the lack of data sharing and intelligence sharing. For example, the lack of platforms for organisations to securely share lessons learned was cited by multiple respondents as a limitation of the commercial technology offerings. Lack of standardisation or centralisation was also considered a limitation of commercial offerings, and some suggested this was an area in which the government should intervene.

For some, the international nature of supply chains was seen as a barrier to mandating standards such as Cyber Essentials across the supply chain. For others commercial offerings were thought not to be sufficient, or too numerous to be beneficial. A small number of respondents mentioned cyber insurance as an additional commercial offering that had the potential to support organisations with supply chain risk management.

3.8 Government response

The growing market for technology platforms that support organisations to manage supplier risk is seen as a very effective tool. The government is committed to supporting innovation and growth in the development of new products, and is seeing the benefit of this investment. Graduates of DCMS-funded accelerators were some of the supply-chain focussed products cited by respondents as effective commercial offerings, demonstrating the value of government support for this sector. The recently launched Cyber Runway programme will build on this success, offering new cyber security firms business masterclasses, mentoring, product development support, networking events, and backing to trade internationally and secure investment.

DCMS will continue to work with the NCSC to support and nurture new and existing startups developing solutions to supply chain cyber security risk. NCSC for startups, the successor to the NCSC Cyber Accelerator, will bring together innovative startups with the NCSC’s technical expertise to solve some of the UK’s most important cyber challenges.

A proliferation of different commercial offerings, although reflective of a dynamic, growing market, appears to be overwhelming for organisations seeking to invest in their cyber security. The government will consider what role it should play in supporting organisations to navigate these choices, which may involve additional guidance to support the consistency and comparability of products and services that can support supply chain cyber security risk management.

3.9 E: Additional government support required

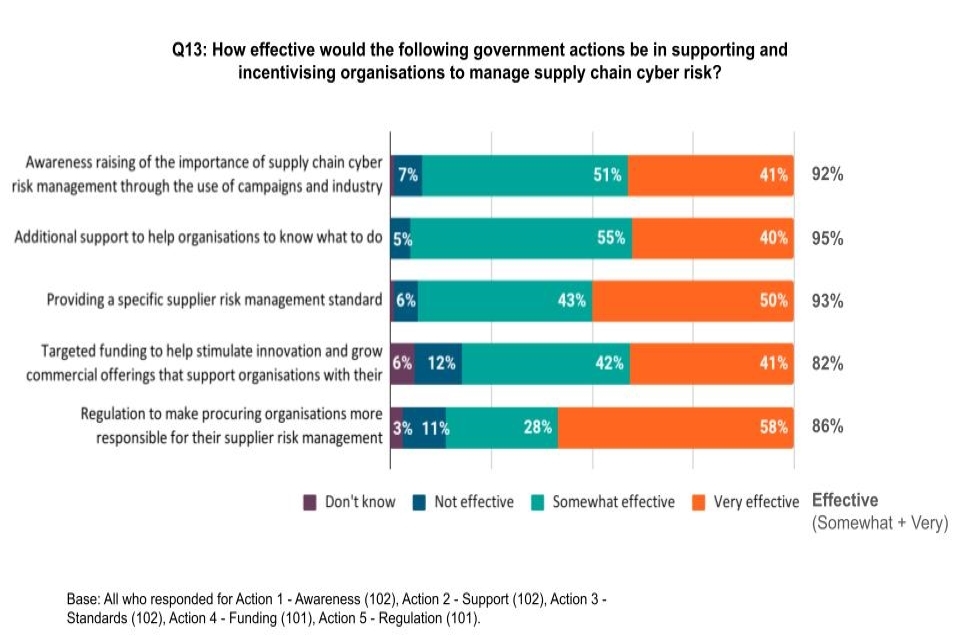

This section of the Call for Views asked respondents to consider how effective a number of government actions would be in supporting and incentivising organisations to manage supply chain risk.

Q13: How effective would the following government actions be in supporting and incentivising organisations to manage supply chain cyber security risk?

Figure 5: Effectiveness of potential government actions in supporting and incentivising organisations to manage supply chain risk

More than 80% of respondents stated that each of the five potential government actions to incentivise higher quality of supply chain risk management would be at least somewhat effective. The action that respondents thought would be most effective (95% of responses rated as somewhat or very effective) was additional government support to help organisations know how they can properly manage their cyber security risk.

The action that gained the most responses for being very effective (58%) was government regulation to make organisations more responsible for their supplier risk management, suggesting that organisations may need stronger levers to ensure they appropriately manage their supplier risk management.

3.10 Government response

Government recognises the need for additional support to help organisations understand how to manage their cyber security risk. There was strong awareness and uptake of existing NCSC guidance among respondents to the Call for Views, but there is more work to be done both in informing the development of new guidance and in awareness raising. The government will continue to invest in awareness raising and uptake of guidance through its Cyber Aware campaign, targeting small businesses in particular as the potential ‘weakest link’ in the supply chain. Government will also seek to raise awareness and uptake of guidance through its targeted engagement with influential market agents, such as investors, banks and insurers that have the potential to drive greater prioritisation of supply chain risk management.

Regulation was considered ‘very effective’ by more respondents than any other form of government intervention. The government must balance the effectiveness of more forceful interventions with the need for any intervention to be proportionate and ensure that the UK supports innovation and growth. DCMS is currently committed to supporting organisations to manage their cyber security risk through the provision of advice and guidance, promoting a common cyber security baseline through Cyber Essentials, upskilling the UK workforce in cyber skills, and working with industry to encourage organisations to better prioritise supply chain cyber security risk. It is clear however, that the barriers organisations face in managing supply chain cyber security risk may not be overcome by awareness raising and the provision of new guidance alone. Alongside addressing the structural barriers around access to skills and supporting market solutions, DCMS is also exploring more interventionist approaches, but will target these in sectors that are most critical to the resilience of the UK, or which have the potential to pose most supply chain risk across the economy.

4. Call for views part two - Managed Service Providers

The second part of the Call for Views examined the role managed service providers play in the UK’s supply chains across the economy, including government and Critical National Infrastructure. Many managed services have become essential to their customers’ operational and business continuity. As the use of managed services has increased, a growing number of cyber threat actors have targeted managed service providers in recent years as a pivot point to access their customers, including UK Critical National Infrastructure. This section sought views on the government’s preliminary proposals for managing the cyber security risks associated with managed service providers. This includes the suitability of a proposed framework for managed service provider security and its possible adoption pathways.

4.1 A: The benefits and risks of managed service providers

The Call for Views stated that the adoption of managed services, including cloud, is regarded as an efficient and cost-effective way to stay up-to-date with rapid technological change, access in-demand skills or expertise, and have flexible, scalable, and high-quality IT services. For this reason, managed service providers were argued to be essential to the functioning of the UK’s economy as they act as key enablers of the UK’s digital transformation.

Q14 What additional benefits, vulnerabilities or cyber security risks associated with managed service providers would you outline? (answered by 63 respondents)

Respondents were asked whether there are any further benefits, vulnerabilities or cyber security risks associated with managed service providers, in addition to those outlined in the Call for Views. In response, participants highlighted a number of cyber security-related benefits to working with managed service providers. Some gave detailed responses about how working with managed service providers is fundamental to running their business operations and achieving a higher level of security assurance. In particular, these responses cited access to a far higher quality of skills, expertise, technology, processes, accreditation, threat intelligence, and innovation, for instance.

Further feedback also indicated that managed service providers have much greater capacity to deploy appropriate resources and capabilities in a manner that is agile, fast and efficient. It is very clear that, for many customers, working with managed service providers is essential to running and improving their cyber security functionalities:

“For many businesses running a continuous and expert security operations function is overkill and too costly. [Working with] a managed service provider means [customer organisations] get access to expertise, technology and methodologies and structured processes that it would be impossible for them to have in-house.” [Sic]

Additionally, respondents mentioned economies of scale as another key advantage to the use of managed service providers. There are significant cost benefits for end user organisations in engaging managed service providers that operate at scale. The offer of these services is, therefore, instrumental in driving the UK’s economic growth and resilience:

“Clients use Managed Service Providers to understand the technology and threat landscape, and to keep up with the rate and pace of change in technology. Managed Service Providers reduce upfront capital costs. For example, operating a security operations center is extremely expensive and MSPs provide a means of reducing the cost of managing these types of solutions”.

Despite these benefits, respondents identified several challenges associated with digital technology providers such as managed service providers. In response to the question on risk, respondents highlighted that managed service providers, as well as cloud and software vendors, can be a key source of supply chain risk to customer organisations:

“The more third parties you allow into your systems the larger you grow your attack surface.”

A number of respondents also pointed to large cloud and managed service providers with wide consumer bases as being a particular source of potential risk because they are often perceived as attractive and high value targets by malicious actors. In terms of criticality, sizable cloud and managed service providers are often used by a larger number of critical UK organisations. This means that an attacker targeting a single, large digital provider could compromise a significant portion of the UK critical infrastructure or economy.

The input from this consultation and associated industry workshops placed a considerable emphasis on a number of difficulties arising from the relationship between cloud and managed service providers and their customers in terms of managing supply chain risk. A number of respondents, for instance, cited a lack of visibility over the wider supply chain as a particular hindrance to achieving robust cyber security maturity within their own organisations. Several responses also referred to a lack of transparency when it comes to managed service providers or other digital providers’ internal cyber security risk management processes.

This reflects a key point that was made in industry workshops regarding a notable imbalance of power between UK customers of all sizes and typically larger, often multinational, cloud and managed service providers. Many companies do not feel that they have the resources or power to request information or require, where appropriate, more stringent cyber security practices of their larger digital technology suppliers. In the context of those challenges, a number of participants in the Call for Views workshops called for a higher level of government intervention which would introduce more accountability for larger suppliers:

“We cannot manage the risk from tech multinationals - we do not have a negotiating stance. We need a mechanism for holding Managed Service Providers to account.”

The other key risk associated with managed service providers was the lack of an effective assurance standard. Currently, there are very few requirements placed on new managed service providers entering the market. This has resulted in a variable level of cyber security offered by managed service providers operating in the UK. Respondents agreed that an assurance framework providing a minimum standard of cyber security requirements would be beneficial to the cyber security of both customers and suppliers. Many respondents, for instance, pointed to the need for more consistent auditing practices of digital providers in order to standardise cyber security practices across the industry and to provide customers with appropriate levels of assurance.

This perspective was further reflected in the Call for Views workshops in which participants underlined the need for “one certification or audit system that can be applied to all”. In this vein, input from workshops suggested that existing frameworks and standards are often inconsistent across the market. This inconsistency can lead to inadequate security practices for companies engaging digital technology providers such as managed service providers.

“Government should standardise an existing industry framework. Standardised frameworks, approaches and processes are needed - the more international the better.”

Q15 Are there certain services or types of managed service providers that are more critical or present greater risks to the UK’s security and resilience? (answered by 67 respondents)

The Call for Views also asked respondents to comment on whether certain services or types of managed service providers were more critical or presented greater risks to the UK’s security and resilience. Many stated that managed service providers associated with critical national infrastructure present the greatest risk to the UK’s cyber resilience. Furthermore, some submissions suggested that the prevalence of a small number of critical cloud and managed service providers across multiple key sectors means that a more stringent approach to these digital providers’ cyber security is necessary. These respondents argued that a higher level of cyber security would ensure not only the security of individual clients, but also the resilience of the UK economy and critical national infrastructure as a whole.

In terms of situating this risk, many respondents mentioned that any managed or other digital service provider interacting with critical data or accessing business infrastructure is likely to pose a strong cyber security risk. Further insights stated that any extensive or privileged access to user systems is a possible entry point for an attacker. Providing access to third parties in a way that allows access or storing of organisational data was listed as another risk of relying on digital providers such as cloud or managed service providers. In a similar vein, some respondents noted that, simply by entering a client-supplier relationship, providers of software, cloud and core business services as well as those providers supplying services at scale are likely to expose their customers to greater cyber security risks.

4.2 Government response

The responses to the Call for Views have highlighted the complexity of the digital technology services ecosystem, both in the UK and internationally. This complexity, as a number of respondents pointed out, lends itself to the many challenges inherent to the task of defining managed service providers. Many submissions voiced concerns regarding the government’s intention to place additional requirements on an entire UK digital sector. Developing definitions and establishing clear boundaries between various providers of digital technology solutions, including cloud and managed services, remains a challenging task for this government. Furthermore, the same issue has also emerged in discussions with a number of international partners engaged for the purpose of this consultation.

The consultation purposefully used a broad definition of managed service providers to avoid placing the focus on particular types of providers, services, or business sizes. A broad definition also allowed for a wider range of government interventions to be considered within the consultation. As a result, a number of participants supported their submissions with advice outlining differences between managed services and cloud, which in their view should be defined separately. Others flagged, without being prompted, risks associated with other critical digital technology providers such as software vendors.

The government recognises that definitions change depending on the context and policy objectives pursued, and will assess what definition is most suitable carefully in any intervention. For example, a wider definition and scope may be appropriate when developing guidance for the industry. However, there may be a rationale for narrowing definitions when introducing additional requirements aimed at those engaging with government procurement.

As we seek a common understanding and appropriate language to best represent the diversity of providers of digital technology services, the government will act on consultation feedback and continue work to further refine and distinguish the definitions of cloud and managed service providers. The government will also act on the feedback from industry and international partners who highlighted the systemic importance of some cloud, software and managed service providers and, therefore, the need for further policy prioritisation.

In addition, the government recognises the close interaction and the frequent business model overlaps between digital technology providers such as managed service providers, cloud service providers and some software vendors. All of these types of suppliers are endemic third party providers of digital technology services and are an indispensable part of UK and global supply chains. The government therefore agrees that any future policy should consider this broader range of digital technology providers, moving away from an exclusive focus on managed services.

Insights from the Call for Views, associated industry workshops and engagements with international partners have strongly confirmed and further reinforced the government’s understanding that providers of digital technologies such as cloud, managed services and software bring numerous benefits to the UK economy. The input from the consultation unambiguously emphasises the positive and critical role that cloud and managed service providers play in building the UK economy and delivering public services. They also play a fundamental role in building cyber security and resilience in the UK.

The government recognises the Call for Views was too narrowly focussed on risks associated with this industry. As such, the government aims to further underline that providers of cloud and managed services are vitally important net contributors to, and critical enablers of, the modern UK economy. These digital providers deliver essential business solutions and have become a business necessity to the great majority of organisations in the UK.

While these providers of digital solutions such as cloud and managed services have an important role to play in improving security and resilience among UK organisations, the consultation feedback confirms that they present a certain level of risk. This reflects the challenges currently facing the government in the broader digital regulation landscape. As has been outlined in the government’s Plan for Digital Regulation, resilience and security are both key factors in driving prosperity and building trust in the UK’s digital economy.

Responses to the Call for Views have highlighted a systemic dependence on a group of the most critical providers which carry a level of risk that needs to be managed proactively. Other challenges referenced included risks associated with providers having privileged access to customer networks, information systems and business-critical data as well as customers having to depend on the supplied cloud and managed services for business continuity. Input to the Call for Views also accentuated the challenges of effective cyber security risk management within the digital technology services industry, as well as the difference between the customers’ and the suppliers’ perspectives.

On the one hand, customers highlighted challenges around information asymmetries and power imbalances, especially when dealing with larger cloud or managed service providers. Many respondents argued, for example, that they cannot make fully informed procurement decisions because it is increasingly difficult to obtain the necessary cyber security assurance from providers who are reluctant to provide information on their cyber security measures or standards they adhere to. This poses a number of business and operational challenges for customers who ultimately bear the risk of cyber security incidents. The allocation of responsibilities, including risk ownership, is further obfuscated by an incorrect perception among certain customers that, by purchasing cloud or managed services, they can conveniently outsource cyber security risk.

Some suppliers, on the other hand, believe that the greatest cyber security risks come from customers. One of the main risks highlighted in the consultation, for instance, pertains to customers’ inadequate configuration of services, which often results in serious vulnerabilities. Suppliers of managed and cloud services have also stated that some customers procure services incommensurate with their own security risk posture. The main causes include the financial pressures faced by customers of digital technology services operating on thin profit margins. Many of these customers seek the cheapest solutions or have an inaccurate understanding of the organisational risk picture.

The government recognises that there is a need to address certain asymmetrical power structures within the market. It is clear that some providers of digital solutions should offer greater levels of assurance, for example, by improving transparency over their cyber security practices. Furthermore, to raise cyber maturity across the market, customers with lower levels of cyber resilience will need to be equipped with the right tools and information to make business- and risk-informed decisions.

4.3 B: Securing the provision of managed services

The government is working to identify frameworks to assure that the most critical managed service providers achieve a common, baseline level of security in alignment with current standards and regulatory requirements. This is important given the diversity of the managed service provider industry and the already-complex domestic and international landscape of cyber security standards.

A future managed service provider security framework

The Call for Views asked respondents whether the NCSC’s Cyber Assessment Framework would be an appropriate framework for addressing managed service provider cyber security by providing a common set of minimum security standards. Respondents were also asked to identify any additional principles that they believe should be incorporated into a future managed service providers framework.

Q16: When considering the 14 Cyber Assessment Framework principles, how applicable is each principle to the cyber security and resilience considerations associated with managed service providers?

Figure 6: Applicability of Cyber Assessment Framework Principles to the cyber security and resilience considerations associated with managed service providers

The 14 Cyber Assessment Framework principles were all deemed to be completely or somewhat applicable to cyber security and resilience considerations associated with managed service providers by at least 96% of respondents, with all 14 principles perceived as being “Completely Applicable” by at least 70% of respondents. The categories deemed most applicable were “Data Security” and “System Security”. Overall, this indicates that the Cyber Assessment Framework, or a framework based on it, should form the future security baseline for managed service providers. The Cyber Assessment Framework would also be considered appropriate based on the feedback from participants in industry workshops. Many of these participants underlined the need for a standardised, flexible (outcomes-based) and simplified security baseline that is accessible to businesses of all sizes and reflects the criticality of managed service provider cyber resilience.

Q17 Can you identify other objectives or principles that should be incorporated into a future managed service provider security framework? (answered by 52 respondents)

Respondents were subsequently asked whether they could identify any other objectives or principles that they believe should be incorporated into a future managed service providers security framework. Many responses included suggestions that are already covered by the existing 14 principles in the Cyber Assessment Framework. Some suggested other objectives or principles that could be further considered:

- The addition of prescriptive requirements: The recommendation included stipulating more specific requirements which could be achieved by identifying particular measures, tools or processes that companies should follow. Some respondents further suggested that the framework (14 principles) should be prescriptive.

- Formal certification with auditing: Some respondents suggested adding a requirement for managed service providers to engage external auditors to assess their compliance with the framework rather than relying on self-assessment.

- An obligation to report incidents: There was a proposal to require providers to report incidents or breaches to the relevant competent authority in a timely manner.

- Improved or mandatory testing: Some recommended that there should be regular testing of incident response and recovery.

- Metrics on severity of incidents: Some proposed including metrics on the frequency and severity of incidents, which would help to guide risk decisions.

- Role of individuals: Feedback included suggestions to appoint individuals responsible for cyber security or a requirement that someone within the organisation hold a cyber security qualification.

4.4 Government response

The government recognises very strong industry support for the application of the Cyber Assessment Framework principles in the context of managed service providers’ cyber resilience. The government will act on this feedback by committing to a further consideration of the Cyber Assessment Framework principles when establishing any future security baseline or assurance frameworks for the managed services industry or, where appropriate, other providers of digital technology services.

The government further recognises alternative principles could be incorporated into, or become a supplement to, the NCSC’s Cyber Assessment Framework to help address cyber security risks associated with digital providers and their customers. Examples of these principles include formal certification with auditing, obligation to report incidents as well as customer transparency and cooperation specification (to help mitigate against the lack of transparency highlighted by respondents as a key barrier to managing suppliers).

4.5 C: Implementation options

The government has undertaken an early scoping of policy implementation options intended to incentivise an uptake of any future industry security baseline and to drive good cyber security practices more broadly. The government’s preliminary policy options are outlined below, and described in more detail in the Call for Views.

- Developing education and awareness campaigns aimed at managed service providers’ customers.

- Establishing a certification or assurance mark to guide customers in procuring Managed Services. This could be based on an existing standard, such as the Cyber Assessment Framework.

- Setting minimum requirements in public procurement.

- Developing new or updated legislation to incentivise the uptake of security standards and, where necessary, to hold managed service providers and their customers accountable for security outcomes.

- Creating a set of targeted regulatory guidance to support Critical National Infrastructure sector regulators in overseeing and managing risks associated with managed service providers.

- Developing joined-up approaches internationally to managing Managed Service Provider security issues.

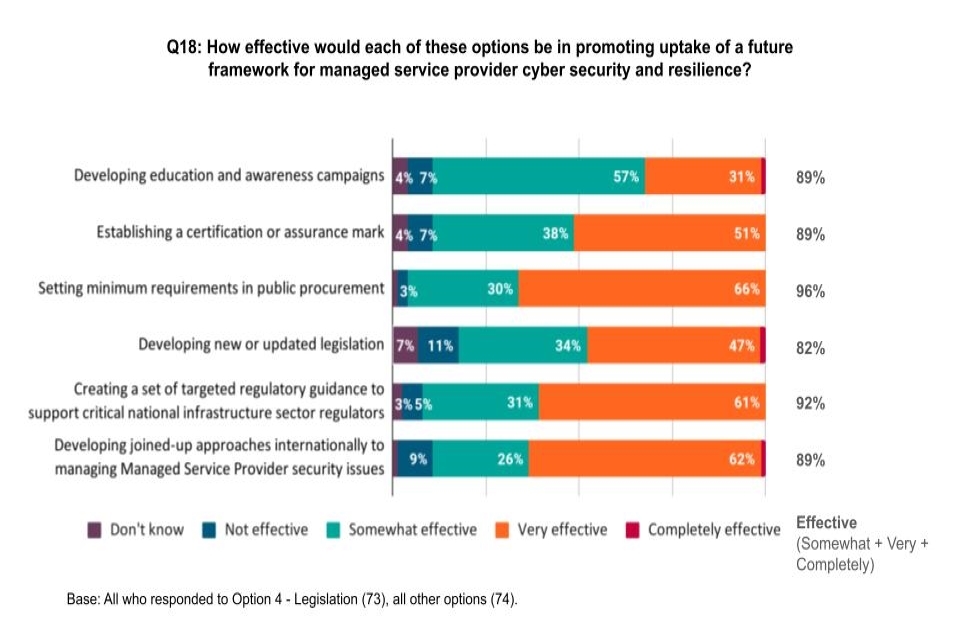

Q18: How effective would each of these options be in promoting uptake of a future framework for Managed Service Provider cyber security and resilience?

Respondents were asked how effective they thought each of these options would be in promoting the uptake of a future framework for managed service provider cyber security and resilience.

Figure 7: Perceived effectiveness of options in promoting uptake of a future framework for Managed Service Provider cyber security and resilience

All of the six options suggested for promoting a future managed service provider cyber resilience framework were considered to be at least somewhat effective by 82% of respondents or more. The options with the higher proportion (more than 60%) of “very effective” responses were: “setting minimum requirements in public procurement”, “developing joined-up approaches internationally to manage managed service provider security issues”, and “creating a set of targeted regulatory guidance to support critical national infrastructure sector regulators.”

Respondents were also invited to explain their reasoning for why these options would be effective or ineffective and to comment on alternative ways in which the government could act to drive cyber security maturity across the industry. Explanations or suggestions were provided by 62 respondents. Comments on the potential effectiveness of each option are summarised below:

Developing education and awareness campaigns

- Some respondents commented that guidance or education campaigns would be needed: “These should be continuous and have always been successful in other government campaigns. They should target businesses to ensure that the Managed Service Providers they are using are credible, have correct due diligence in place and hold formal accreditation.”

- Some commented that education and awareness should be managed by the government or appropriate industry bodies.

- However, some industry workshop participants highlighted the limitations of guidance suggesting more interventionist solutions may be more effective in driving improvements: “Guidance must be mandatory to be effective.”

Establishing a certification or assurance mark

- Some noted that certification or assurance would be an effective way to encourage a higher standard of cyber security: “Certification or assurance marks, especially when internationally aligned, make it easier for organisations to comply and also ensure that their suppliers are complying.”

- In addition, some noted that certification or assurance should be externally assessed: “Demonstrating that they can fulfil the requirements to be certified is only the start, Managed Service Providers should then be audited.”

Setting minimum requirements in public procurement

- A number of submissions asserted that minimum requirements for public procurement would be needed: “Public services, like some other sectors, are high-risk targets, and minimum requirements should be placed on Managed Service Providers [supplying to government].”

Developing new or updated legislation

- 82% of respondents thought that new or updated legislation would be an effective or a somewhat effective solution, demonstrating a generally positive response to a legislative policy solution

- Many of these respondents were of the view that guidance is less effective than legislation because it is not mandatory: “Unless the framework is mandated through contracts or legislation, it will have only a small effect. This is because Managed Service Providers that want to do the right thing and be secure already do that. The ones that do not operate in a secure way will not change their habits with guidance.”

- While many commented that new or updated legislation would be needed, a few thought this would be unnecessary: “A blanket one-size-fits-all approach to all Managed Service Providers regardless of the nature of their services will not be proportionate or effective (…). A more targeted approach (…) will be preferable in the short to mid term.”

Creating a set of targeted regulatory guidance to support Critical National Infrastructure sector regulators

- Responses relating to the creation of targeted regulatory guidance to support critical national infrastructure sector regulators most commonly highlighted that regulatory guidance already exists.

- However, several respondents advised that further work needs to be done with regards to promoting the guidance as some managed service providers may be unaware of existing guidance and, consequently, do not implement it.

Developing joined-up approaches internationally to managing Managed Service Provider security issues

- Respondents and participants in industry workshops stated that an international approach would be needed to further strengthen the efficacy of UK policy implementation options. Some suggested that existing international standards such as ISO 27001 should be utilised, or new approaches aligned with these: “International standards are key. Managed Service Providers must operate globally to provide the economies of scale that make them competitive.”

- Collaborative responses and information sharing, for example by multilateral country groups or initiatives, was also suggested: “How can you regulate these big international organisations? (…) Effective solutions are required at an international level with support of the US.”

Other suggestions for policy implementation options included encouraging joined-up working domestically through initiatives such as industry working groups; improving awareness and the structure of the NCSC’s guidance to ensure more widespread uptake; and the publication of benchmarks for organisations to refer to.

Respondents to the survey and participants in associated workshops also pointed out that companies of different sizes and criticalities have different needs and capabilities. This suggests that a universal approach to cyber security for all managed service providers - or other digital technology providers like cloud or software vendors - would reflect neither the different levels of resources that companies have available to them, nor the varied levels of cyber security risk that different types and sizes of companies pose to the UK economy.

4.6 Government response

The government recognises that a range of audience-specific interventions will be needed when addressing challenges associated with the diverse and rapidly evolving digital technologies market. This approach will ensure that different types, sizes and criticalities of digital technology suppliers and their customers will all be accounted for.

The government will take into account the positive reception to all policy options suggested in the Call for Views to help address the supply and demand side of the digital technology services market. Of the options listed in the consultation, the government is currently prioritising legislative work and international engagement to promote international cooperation, including evidence sharing at both a bilateral and multilateral level. However, the government recognises the need for a concerted effort to comprehensively address the cyber security resilience within the digital services industry and its customers.

Legislation and international coordination cannot be viewed as silver bullets to solve the manifold facets of cyber security within this diverse industry. For this reason, the government will continue to collaborate with a wide range of partners, including digital providers, procurers of digital technology services, industry experts and international stakeholders to develop a wide range of policy interventions, building on legislation and international engagement efforts.

5. Glossary

The following terms are working definitions, developed for the purposes of this publication. These terms should not be considered as final and are not reflective of government policy. If you have any questions or suggestions please contact cyber-review@dcms.gov.uk.

Critical national infrastructure (CNI) - Critical elements of infrastructure (namely assets, facilities, systems, networks or processes and the essential workers that operate and facilitate them), the loss or compromise of which could result in:

- Major detrimental impact on the availability, integrity or delivery of essential services – including those services whose integrity, if compromised, could result in significant loss of life or casualties – taking into account significant economic or social impacts; and/or

- Significant impact on national security, national defence, or the functioning of the state.

Digital connection - Refers to the use of information technology in the provision of goods and services between procurer and supplier. This may include the transfer of data between an organisation and its suppliers, granting suppliers access to organisations networks and systems, and the outsourcing of critical departments and operations to third parties.

Digital supply chains - Refers to all an organisation’s third party vendors which have a digital connection to an organisation, and that vendor’s wider supply chain.

Impact - The consequences of a cyber breach, both to the organisation, and to society. The impact of a cyber breach is often realised as a cost. See Full Cost of Cyber Breaches Study.

Managed Service Provider - A supplier that delivers a portfolio of IT services to business customers via ongoing support and active administration, all of which are typically underpinned by a Service Level Agreement. A Managed Service Provider may provide their own Managed Services, or offer their own services in conjunction with other IT providers’ services. The Managed Services might include:

- Cloud computing services (resale of cloud services, or an in-house public and private cloud services, built and provided by the managed service providers)

- Workplace services

- Managed Network

- Consulting

- Security services

- Outsourcing

- Service Integration and Management

- Software Resale

- Software Engineering

- Analytics and Artificial Intelligence (AI)

- Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery services

The Managed Services might be delivered from customer premises, from customer data centres, from an managed service providers own data centres or from 3rd party facilities (co-location facilities, public cloud data centres or network Points of Presence (PoPs)).

Supply chain assurance - The process of establishing confidence in the effective control and oversight of an organisation’s supply chain.

Supply chain - The Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply defines a supply chain as ‘the activities required by an organisation to deliver goods or services to the consumer’[footnote 2].

Supply chain risk management - All organisations will have a relationship with at least one other organisation and most organisations will be reliant on multiple relationships. Supply chain cyber security risk management is the approach an organisation uses to understand and manage security risks that arise as a result of dependencies on these external external suppliers, including ensuring that appropriate measures are employed where third party services are used.

Supplier - Any organisation that supplies goods and/ or services to an organisation that involves establishing a digital connection with the procuring organisation.

(Cyber) Threat - Malicious attempts to damage, disrupt or gain unauthorised access to computer systems, networks or devices, via cyber means.

Threat actor - A person or group involved in an action or process that is characterised by malice or hostile action (intending harm to an organisation) using computers, devices, systems, or networks. Includes cyber criminals, ‘hacktivists’, nation states and terrorist organisations.

Vulnerability - A point of weakness and/or possible threat to the supply chain network.

-

For the purposes of this Call for Views and the government’s current interest in supplier cyber risk management, the scope is limited to digital supply chains. A digital supply chain refers to the supply of digital products and services, the sharing of business critical information or where suppliers have a digital connection to an organisation and that supplier’s wider digitally connected supply chain. The physical security of non-digital assets is also critical to cyber security but not the focus of this publication. ↩

-

https://www.cips.org/knowledge/procurement-topics-and-skills/supply-chain-management/what-is-a-supply-chain/ ↩