Global Talent visa evaluation: exploring experiences of the Global Talent visa process - wave 1 report

Published 30 May 2022

Ipsos UK

Authors: Rachel Worsley, Mark Matthews, Charlotte Peel, Alice Sarkany, Kirsty MacLeod

Home Office Analysis and Insight

Executive summary

Background and methods

The Global Talent visa forms a key part of the UK’s offer for talented and promising individuals in the fields of science and research, digital technology and the arts. It was introduced in February 2020 to replace the Tier 1 (Exceptional Talent) visa and make the process smoother, faster and more attractive for exceptionally talented people to live and work in the UK.

In order to understand how the visa is working, the Home Office commissioned Ipsos to conduct mixed-methods research with successful Global Talent visa holders. This research forms part of a wider evaluation work by the Home Office on the visa. The research included a telephone and online survey completed by 307 successful visa holders, and 20 in-depth telephone interviews. [footnote 1] The Home Office also conducted six interviews with UK Visas and Immigration staff, which are referenced in this report.

Deciding to apply for a Global Talent visa

The most common way those surveyed first heard about the Global Talent visa was through their university or institution (23%), followed by through a friend or family member (22%).

Overall, 94% of visa holders surveyed selected one or more ‘careers or jobs’ factors as most important in deciding to move to or remain in the UK. This was followed by factors related to their professional environment (such as opportunities to make a success of their career and the international standing and prestige of institutions related to their work).

The majority of visa holders surveyed (80%) said the Global Talent visa had in part influenced their decision to apply to live and work in the UK. ‘Pull factors’ to the UK meant that, had the Global Talent visa been unavailable, 66% surveyed would have applied for a different visa.

Among those surveyed who said the visa had influenced their decision, key features that attracted them were potential eligibility for settlement and being endorsed by a recognised body in their field (selected by 78% and 77% respectively). In-depth interview participants valued not being tied to a specific employer, affording them freedom to make career choices, such as looking for roles with higher pay and being able to take risks or be more creative in career choices.

Experiences of the application process

Satisfaction with the visa application process was high among those surveyed: 93% were satisfied with the overall process, 92% with the endorsement process and 86% with the main visa application process.

Visa holders surveyed were satisfied with the quality of the written guidance for endorsement (79%) and the visa application (85%). Participants also suggested that additional guidance would be helpful, including on what the endorsement and visa application processes involve (for example timings), and guidance on the information they needed to provide which they wanted to be tailored to their specific fields of expertise.

Most visa holders surveyed received endorsement and visa application decisions within expected timescales (80% and 74% respectively). There were suggestions that the process could be quicker with clearer information on how long the endorsement and visa application processes would take.

Overall, 90% surveyed said the visa application form was easy to complete. In-depth interview participants who had applied for other UK visas in recent years (for example, those who had switched from a student or Tier 2 visa) noted that applying for a Global Talent visa was less burdensome.

Three in five survey participants (63%) thought the total application fee was fair, while 33% felt it was unfair. In contrast, a greater proportion said the Immigration Health Surcharge was unfair than fair (59% and 34%).

Half (52%) of visa holders surveyed who applied with dependant relatives thought fees for dependants were unfair; 46% thought that they were fair. In-depth interview participants also generally viewed fees for dependants as expensive.

Professional contributions and future intentions

Most visa holders surveyed were employed (95%) and agreed that their current job suited their skills and experience (99%). The most common salary band was between £31,200 and £51,999 (49%).

Participants were positive about their diverse professional contributions, which reflected the varied fields of expertise. The most common type of professional contribution cited by visa holders surveyed was conducting academic research (30%) into an array of topics from climate change to COVID-19. Smaller numbers (7%) had published or presented their research, although in-depth interview revealed that this was the ultimate intention for many researchers.

The flexibility of not being tied to one employer, and having access to UK job markets and experts, created professional opportunities for participants, facilitating their contribution to the UK. However, the COVID-19 pandemic limited professional opportunities in some sectors, such as the arts.

While in-depth interview participants identified some potential barriers to settlement, most spoke about their plans to remain in the UK long-term. Participants were motivated by the opportunity to build on the contributions they had already made and access to professional networks in the UK. Other facilitators that people cited as motivating them to apply for settlement in the UK included having established personal networks, being made to feel welcome in their job and local community, and access to government-funded health and education services. Settlement intentions were not covered in the survey.

Lessons learned

A number of lessons learned about the process and considerations for improvement were highlighted through the research.

-

Adaptions and improvements to the process, including how to further publicise the Global Talent visa route; suggested improvements to guidance; adjustments to fees, so that applicants perceive them as fair; and ways to capitalise further on the pride and value participants took from being a Global Talent visa holder.

-

Analytical recommendations, including further research to better understand visa holders’ experiences of applying for settlement; how the Global Talent visa route compares to other UK visa routes; and the experiences of unsuccessful applicants.

Chapter 1: Introduction

This chapter outlines the background and policy context to the Global Talent visa and this research.

1.1 Overview of the policy context and background

The UK government introduced the Global Talent visa in February 2020. The Global Talent visa forms a key part of the UK’s offer for talented and promising individuals in the fields of science and research, digital technology and the arts, who wish to live and work in the UK.

A number of countries offer visas aiming to attract highly skilled and renowned professionals, artists and researchers, including the Global Talent visa programme in Australia, [footnote 2] the O-1 visa in the USA, [footnote 3] the Global Talent stream in Canada, [footnote 4] and Talent R visa in China. [footnote 5]

In the UK, the Global Talent visa replaced the Tier 1 (Exceptional Talent) visa. The main changes included:

- lifting the cap on the number of eligible visas

- the addition of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) as an endorsing body

- including a fast-track endorsement pathway for some applicants

- widening the number of eligible fellowships and fields of endorsement (explored further below)

The aim of the changes was to make the application process smoother, faster and more attractive to exceptionally talented individuals.

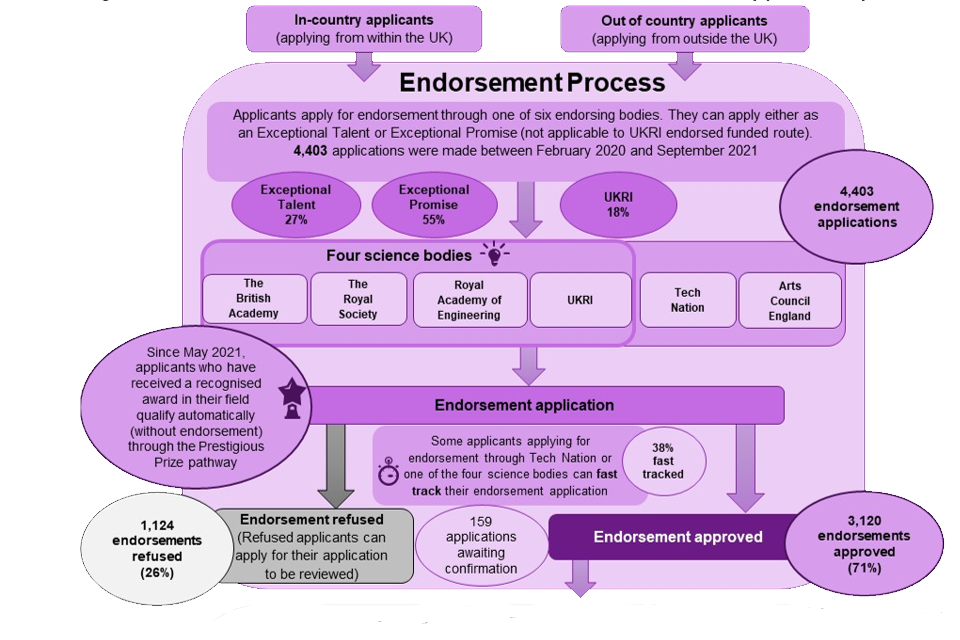

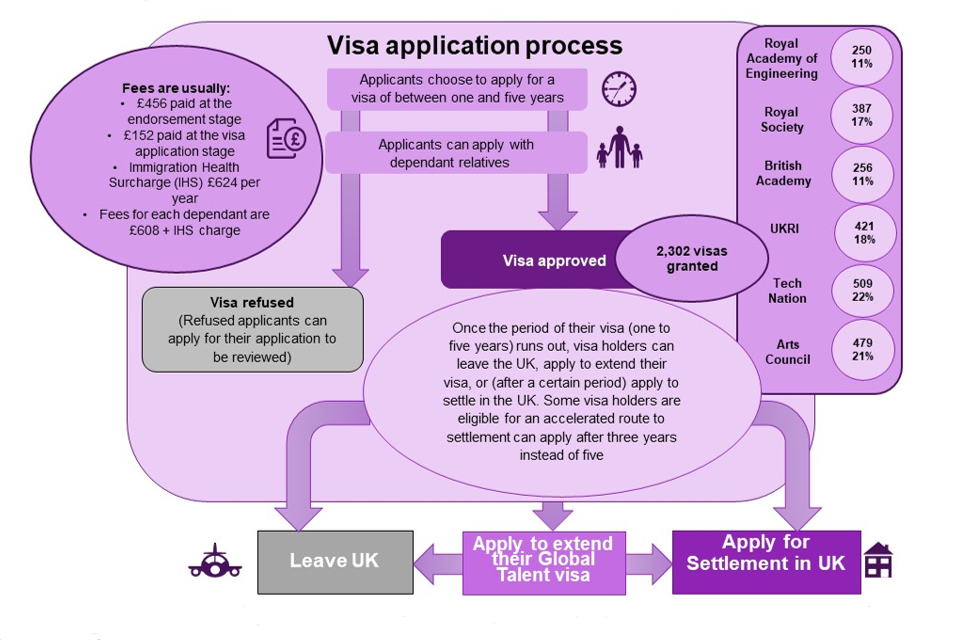

For most applicants, the Global Talent application process involves two stages: endorsement and visa application. Most applicants apply for endorsement either as an Exceptional Talent or someone showing Exceptional Promise in their field. [footnote 6] Figure 1.1 below outlines the application process and includes a breakdown of volumes between 1 January 2020 and 5 August 2021.

Figure 1.1 Flowchart of the Global Talent endorsement and visa application process

Figure 1.1 Flowchart of the Global Talent endorsement and visa application process

Figure 1.1 Flowchart of the Global Talent endorsement and visa application process

In order to understand more about how the Global Talent visa is working, the Home Office commissioned Ipsos to conduct mixed methods research. Specifically, the research aimed to understand:

- whether the Global Talent visa scheme is working as intended

- how the Global Talent visa has influenced the attractiveness of the UK for successful applicants

- what lessons can be learned about scheme implementation and lessons for improvement

Detailed research questions for each stage of the visa process were provided by the Home Office and are contained in Appendix A.

1.2 The approach

This report forms one part of wider evaluation work by the Home Office. [footnote 7]

A two-wave mixed methods approach has been taken to this work, with wave two planned for 2023. This initial wave focused on the Global Talent visa process, through the lens of successful applicants’ perceptions and experiences of the application process and experiences as Global Talent visa holders. Early insight into participants’ perceived contribution to the UK was also gathered, as were views on what those who took part would have done in the absence of the Global Talent visa.

Methods included a quantitative survey among successful Global Talent visa holders and in-depth qualitative interviews. Qualitative interview participants were invited to take part in the survey once their interview was complete (although one participant had already completed the survey).

Alongside this work, the Home Office conducted six interviews with caseworkers from UK Visas and Immigration (UKVI) which are referenced in this report.

Monitoring information, such as the number of successful applicants, was also provided for context.

Quantitative data collection

A mixed-mode online and telephone survey was carried out among successful Global Talent visa holders. All individuals granted a visa between February 2020 and March 2021 were eligible to take part. [footnote 8]

The questionnaire was designed collaboratively with the Home Office and explored visa holders’:

- backgrounds and demographic data

- motivations to apply for a Global Talent visa

- satisfaction with and experience of the endorsement and visa application process

- employment status and salary

- perceived contribution to the UK and / or to their field of work

Fieldwork took place between 21 June and 9 August 2021. Fieldwork was staggered by mode, with the telephone survey running from 21 June to 2 August, and the online option running from 30 June to 9 August 2021.

An initial invitation email was sent to successful visa holders by the Home Office Analysis and Insight (HOAI) team. A reminder email was sent from Ipsos to visa holders who applied out of country, following completion of the in-country quota. This was followed by a second reminder email.

Quotas were set to ensure sufficient samples of both people who applied for the visa from within the UK (in-country applicants) and people who applied for the visa from outside the UK (out of country applicants).

A total of 307 participants chose to take part. The final achieved sample profile was broadly reflective of the sample frame of successful applicants provided by the Home Office on key visa characteristics including visa type (Exceptional Promise or Exceptional Talent), application type (in-country or out of country) whether the application was fast-tracked, and the endorsing body. Data was not weighted.

Table 1.1: Profile of participants in the quantitative survey

Participant characteristics

| Visa type | Percentage of participants |

|---|---|

| Exceptional Talent | 24% |

| Exceptional Promise | 58% |

| Neither – UKRI Endorsed Funder pathway | 18% |

| Application type | Percentage of participants |

|---|---|

| In-country | 54% |

| Out of country | 46% |

| Track | Percentage of participants |

|---|---|

| Fast-track | 37% |

| Not fast-tracked | 63% |

| Endorsing body | Percentage of participants |

|---|---|

| UK Research and Innovation | 18% |

| Royal Society | 17% |

| Tech Nation | 23% |

| Royal Academy for Engineering | 16% |

| British Academy | 8% |

| Arts Council England | 18% |

Qualitative data collection

A total of 20 in-depth qualitative interviews were carried out to generate a richer data set of the nuanced and diverse views and experiences of visa holders. These took place by phone and Microsoft Teams.

Ipsos developed a topic guide, with input from the HOAI team. The questions followed the visa journey from initially finding out about the visa, through the application process, to visa holders’ professional experiences in the UK and future settlement intentions in the UK. An initial pilot was conducted, whereby the questions were reviewed following the first interviews and amended as required. This involved adding a small number of additional questions to allow for a longer discussion.

Fieldwork took place between 3 June and 2 August 2021. Quotas were set to ensure a range of experiences were captured across areas pertinent to experiences of the visa process, with the total number of interviews for each quota outlined in table 1.2 below.

Table 1.2 Quotas for the in-depth interviews

Quotas

| Visa type | Completes |

|---|---|

| Exceptional Talent | 9 |

| Exceptional Promise | 11 |

| Application type | Completes |

|---|---|

| In-country | 8 |

| Out of country | 12 |

| Nationality | Completes |

|---|---|

| EU | 3 |

| Non-EU | 17 |

| Track | Completes |

|---|---|

| Fast-track (all) | 7 |

| Endorsed funders fast track (science bodies only) | 4 |

| Not fast-tracked (all) | 13 |

| Endorsing body | Completes |

|---|---|

| UK Research and Innovation | 4 |

| Royal Society | 4 |

| Tech Nation | 4 |

| Royal Academy for Engineering | 2 |

| British Academy | 2 |

| Arts Council England | 4 |

| Dependants | Completes |

|---|---|

| No dependants | 13 |

| dependants | 7 |

UKVI staff interviews

Between August and September 2021, Home Office analysts conducted interviews with six UKVI staff members to explore their views on how the application process is working. The interviews took place over Microsoft Teams. The Home Office analysed these interviews and provided a summary to Ipsos. Findings from this summary are referenced throughout this report.

Quality assurance and ethics

Quality assurance was built into all stages of the project, with review and sign off based on clear roles and responsibilities. All research instruments and reports were signed off by the Project Director. The project approach was reviewed by an in-house Ethics Group, to ensure adherence to all five government social research principles. [footnote 9]

All participants took part based on informed consent, making it clear participation was voluntary. Participants were provided with written information and privacy notice ahead of the interview or survey, outlining the aims and objectives of the research, how any data would be used and stored. This included assurances that responses were confidential and that participants would not be identified through the research. This information was also covered at the start of interviews and verbal consent was captured prior to the interview.

Interpretation of the data

Quantitative data

- Where the base size fluctuates between questions with the same base definition, this is due to the exclusion of ‘not stated’ answers.

- Where percentages in this report do not sum 100, this may be due to computer rounding or the exclusion of ‘don’t know’ answers.

- An asterisk (*) indicates a percentage of less than 0.5% but greater than zero.

- It should be noted that the survey was conducted among a sample of successful visa holders who chose to take part, rather than a representative sample or the entire population.

- The achieved profile of survey participants was found to be broadly reflective of the key characteristics of successful visa holders in the sample frame provided by the Home Office (such as visa type).

- Statistical tests were applied to identify differences between sub-groups among those who chose to take part in the survey. Only differences identified in this way are referenced throughout this report. Strictly speaking differences apply only to random samples with an equivalent design effect. This has been taken into account in looking at differences, and these should be treated as indicative overall.

Qualitative interviews

- It is important to note that qualitative research is not designed to cover breadth of opinion, but instead focus on depth; it is not therefore intended to be statistically representative of the wider population. Instead, purposeful sampling is used to explore nuances in people’s experiences and motivations. As such, they complement the survey findings, providing in-depth insight into the perceptions of visa holders.

- Verbatim comments from the interviews have been included within this report. These should not be interpreted as covering the views of all participants but have been selected to provide insight into a particular issue or topic.

- Similarly, perceptions expressed through the qualitative interviews and in verbatim comments represent the ‘truth’ to those who relay them.

1.3 Structure of the report

The rest of this report is broadly structured to reflect the journey of successful applicants, from the initial decision to apply for a Global Talent visa, through to their professional experiences once the visa was granted and intentions towards settlement.

- Chapter 2 outlines findings on how visa holders heard about the Global Talent visa and the factors that were important in their decision to apply to move to or remain in the UK, including the role played by the Global Talent visa.

- Chapter 3 explores experiences and views of the application process including – among other areas – overall levels of satisfaction, the time taken and views of the fees.

- Chapter 4 outlines findings on visa holders’ professional experiences and perceived contribution to the UK, as well as their views on the future and potential settlement in the UK.

- Chapter 5 covers lessons learned from the research.

Chapter 2: Deciding to apply for a Global Talent visa

This chapter outlines key findings on how participants first heard about the Global Talent visa and the factors that were important in their decision to apply to move to or remain in the UK, including the role played by the Global Talent visa.

Key findings

The most common way visa holders surveyed first heard about the Global Talent visa was through their university or institution (23%), [footnote 10] followed by first hearing through a friend of family member (22%).

In the survey, factors related to ‘careers or jobs’ were most important to participants in deciding to move to or remain in the UK: 94% selected one or more factors related to this.

Participants in the in-depth interviews were also motivated to live and work in the UK because of the expertise and prestige in their field of work, with personal connections and the diversity of the UK population also being important.

Overall, 66% of visa holders surveyed said they would have applied for a different visa had the Global Talent visa not been available. This likely reflects the ‘pull factors’ to the UK more generally, and the majority of visa holders surveyed (80%) said the Global Talent visa had an influence in their decision to apply to live and work in the UK.

Among those surveyed who said the visa had influenced their decision, key features that attracted them were the opportunity to settle in the UK and the opportunity to be endorsed by a recognised body in their field (78% and 77% respectively).

In-depth interview participants valued the absence of any requirement to work for a specific employer, affording them freedom to make career choices and take professional risks, such as starting a new business.

2.1 Hearing about the Global Talent visa

The most common way survey participants first heard about the Global Talent visa was through their university or institution (23%). This could have been as an employee or student (this was not specified in the question, so it is not clear which participants meant). A similar proportion (22%) first found out through a friend or family member.

Around one in seven (14%) said they heard through their professional network. In the in-depth interviews, recommendations from successful visa holders working in similar fields were a key source of information about the visa.

Figure 2.1 How visa holders surveyed first heard about the Global Talent visa

How did you first hear about the Global Talent visa?

| How | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Your university / institution | 23% |

| Friend or family member | 22% |

| Colleague or peer within your professional network | 14% |

| On the UK government website | 12% |

| Your employer | 11% |

| News source (eg newspaper, online article | 4% |

| Social Media (eg Facebook, Twitter or Linkedin | 2% |

| On the website of a Global Talent endorsing body | 1% |

| Another way | 9% |

| Don’t know | 1% |

Base: All participants (307)

How those surveyed first heard about the Global Talent visa depended on their field of work. For instance, survey participants working in academia most commonly first heard about the visa through their university or institution (33%), while those who worked in the business sector most commonly first heard about the Global Talent visa through a friend or family member (38%).

In-depth interview participants who first heard about the visa through their employer or university said it was suggested as a way for them to move to or remain in the UK for a new job, or to continue their research through PhDs and fellowships.

I actually heard about the Global Talent visa from the CEO of the company that I’m working for now […]. It was just a matter of us trying to figure out how to get me here.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

Some in-depth interview participants who were already living in the UK on a different visa when they applied pointed out that their employers (or, in the case of students, their place of study) they were affiliated with at the point of applying were not aware of the Global Talent visa, which they attributed to its relatively recent introduction. This encouraged participants to follow more informal channels to find out about the visa, such as blogs, online message boards and one participant who discovered the visa through YouTube videos.

Not many people know about this. Even universities are still catching up with it.

Global Talent visa holder, in-country applicant.

2.2 Decision making factors

Visa holders taking part in the survey were asked to select the factors that were important to them when considering coming to or remaining in the UK. These were grouped into themes to understand their relative importance, including: ‘career or jobs’; ‘professional environment’; ‘familiarity with the UK’; ‘facilities and institutions; ‘aspects of the Global Talent visa’; and ‘access to services’.

The most common factors related to ‘careers or jobs’: 94% selected one or more factors related to this, including opportunities for career progression (84%), and role opportunities that matched their specific skills (79%).

Figure 2.2 Importance of factors related to ‘career or jobs’

Which, if any, of the following factors were important to you when considering coming to, or remaining in, the UK to work and live?

| Factor | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Career / job (NET) | 94% |

| Opportunities for career progression | 84% |

| Opportunity for a role which matched your specific skills | 79% |

| Attractive pay and benefits | 41% |

Base: All participants (307)

Overall, 90% of visa holders surveyed selected one or more factors related to their ‘professional environment’, including opportunities to make a success of their career (78%) or the international standing and prestige of institutions related to their work (75%). The importance of internationally recognised institutions was particularly noted among participants who applied for their visa from outside the UK, with 81% selecting this as a consideration when deciding whether to move to the UK, compared with 70% of visa holders who applied in-country.

Figure 2.3 Importance of factors related to the professional environment

Which, if any, of the following factors were important to you when considering coming to, or remaining in, the UK to work and live?

| Factor | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Professional environment (NET) | 90% |

| Opportunities to make a success of your career | 78% |

| International standing and / or prestige of institutions related to your work | 75% |

| Opportunity to work in a professional environment where you are judged by your skills | 75% |

| Access to professional networks (eg opportunity to work with leading experts and peers) | 74% |

| Ease of setting up a business | 28% |

Base: All participants (307)

Familiarity with or connections to the UK were also important to participants when they were considering moving to or remaining in the UK. Overall, 82% of visa holders surveyed selected one or more factors linked to this, including 71% who selected familiarity with the English language and 55% who selected personal networks (such as family or friends in the UK).

Figure 2.4 Importance of factors related to fitting into the UK

Which, if any, of the following factors were important to you when considering coming to, or remaining in, the UK to work and live?

| Factor | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Fitting into the UK (NET) | 82% |

| Familiarity with English language | 71% |

| Personal networks (eg family and friends) in the UK | 55% |

| Familiarity with British culture | 52% |

Base: All participants (307)

Features of the Global Talent visa, such as the application process and content of the visa, were an important consideration for 69% of visa holders (experience of and views on the visa application process are covered in more detail in chapter 3).

Figure 2.5 Importance of factors related to the Global Talent visa

Which, if any, of the following factors were important to you when considering coming to, or remaining in, the UK to work and live?

| Factor | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Visa (NET) | 69% |

| The content of the visa and what it allows you to do in the UK | 64% |

| The visa application process | 38% |

Base: All participants (307)

Just under four in five (78%) of those surveyed said one or more factors related to facilities and institutions were important to them when considering living and working in the UK. This included facilities to support their work (68%) and availability of funding to support their work (61%).

Access to perceived high quality UK public services, such as healthcare, was important to just over half of visa holders surveyed (54%). UK public services were more likely to be important or a consideration for visa holders surveyed who included dependants on their application than those who did not (65% compared with 50%). Meanwhile, the ability to transfer pensions, social security or healthcare benefits from another country was a motivating factor for only 9% of visa holders.

Participants were asked to rank factors that were important to them when deciding whether to move to or remain in the UK, choosing up to three from most to least important. This reinforced the focus placed on career and professional environment: three quarters of visa holders (74%) included one or more factors related to their career or job as one of the three most important factors. Factors related to professional environment also ranked highly (65%).

In comparison, fitting into the UK was selected by a third of visa holders (34%). Fewer visa holders ranked administrative factors and the visa itself as important when compared to other factors (see figure 2.6 below).

Figure 2.6 Factors ranked in the top three most important when deciding whether to move to or remain in the UK

Which, if any, of the following factors were important to you when considering coming to, or remaining in, the UK to work and live? (% ranked in top 3 choices)

| Factor | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Career / job | 74% |

| Professional environment | 65% |

| Fitting into the UK | 34% |

| Facilities and institutions | 29% |

| Visa | 18% |

| Administration | 11% |

Base: All participants (307)

The survey findings were echoed by in-depth interview participants, who said they were motivated to live and work in the UK because their field of work was valued and there were opportunities to work with experts in their field and as part of internationally renowned institutions.

The UK has been a great place for doing scientific research. It’s known to concentrate a great deal of time and money on scientific research. The [number] of scientists that have come out of the UK has been innumerable.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country.

In-depth interview participants also praised the UK, and London in particular, for its diversity. This made them feel welcome and accepted. Many also highlighted the value of this to their work, noting that diversity spurred creativity and provided the opportunity to collaborate with experts from around the world.

Particularly when you go to the creative industries in London, there’s a lot of cultural diversity and that is always interesting […] When people with very different ideas are put together […] they […] bring out new things. And that happens in different spots in the UK, it’s not just London.

Global Talent visa holder, in-country.

In-depth interview participants with experience living in the UK also highlighted personal ties as an important consideration.

Visa holders interviewed who previously lived in countries without a healthcare system that was free at the point of use or free statutory education were particularly attracted by the UK’s public services for themselves and for their dependants. One participant with a young child described the free education in the UK as a “major factor” attracting them to move to the UK over other countries.

The role of the Global Talent visa in decision making

When asked about the overall influence of the Global Talent visa on their decision to apply to work and live in the UK, 80% of visa holders said it had influenced their decision. Over half (56%) said it had influenced their decision to a great extent (see figure 2.7 below).

Figure 2.7 The extent to which the Global Talent visa influenced visa holders’ decisions to apply to work and live in the UK

To what extent, if at all, did the Global Talent visa influence your decision to apply to work and live in the UK?

| Extent | Percentage |

|---|---|

| To a great extent | 56% |

| To some extent | 24% |

| Hardly at all | 6% |

| Not at all | 11% |

| Don’t know | 3% |

Visa holders surveyed who said the Global Talent visa was an important consideration for them were also asked about the specific aspects of the visa that attracted them. The opportunity to settle in the UK and to be endorsed by a recognised body in their field were both selected by over three quarters of visa holders surveyed (78% and 77% respectively).

Figure 2.8 Aspects of the Global Talent visa that attracted visa holders

Which, if any, of the following aspects of the Global Talent visa attracted you to move to or remain in the UK?

| Aspect | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Opportunity to settle in the UK | 78% |

| Eligibility to be endorsed by a recognised body in your field | 77% |

| Opportunity to extend the visa | 62% |

| Opportunity for an accelerated route to settlement (in 3 years instead of 5) | 60% |

| Ease of application | 50% |

| Research related absences did not affect eligibility for settlement | 31% |

| Opportunity to fast-track the endorsement application | 23% |

| Application fees | 21% |

| It was the only route that was available | 1% |

Base: Participants motivated by applying for the Global Talent visa (213)

In-depth interview participants also felt that the Global Talent visa represented an acknowledgement of their individual merit and dedication to their field of work; one participant described it as a ‘brand’ that verified the visa holders’ talent and skills. Participants hoped that this would benefit their careers, and some felt it had already (explored further in chapter 4).

Once we get this visa, it’s not about the visa itself, it’s about the opportunities you will get on top of this visa.

Global Talent visa, out of country.

Nonetheless, two thirds of visa holders surveyed (66%) said they would have applied for a different visa to move to or remain in the UK had the Global Talent visa not existed.

Three-fifths of participants (61%) said they considered applying for a different visa to move to or remain in the UK before applying for a Global Talent visa. Of those, two thirds (67%) said they considered applying for the Skilled Worker visa (formally the Tier 2 (General) visa).

In-depth interview participants also mentioned that, had the Global Talent visa not been available, the Skilled Worker visa seemed like the most realistic option for them to move to, or stay in, the UK. Views of other visa routes were less positive with the perceived lower success rates of the Tier 1 (Entrepreneur) visa and Start-up visas making them less appealing.

Had the Global Talent visa not been available, around one in five (18%) visa holders surveyed said they would have applied for a visa for another country, with Canada and the USA the most commonly mentioned. [footnote 11] Smaller numbers mentioned other countries, including Germany, Australia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Singapore. In-depth interview participants believed that Canada and the United States offered similar types of visas to attract talented migrants.

Chapter 3: Experiences of the visa application process

This chapter outlines the findings on visa holders’ views and experiences of the endorsement and visa application process.

Key findings

Satisfaction with the visa application process was high among those surveyed: 93% were satisfied with the overall process, 92% with the endorsement process and 86% with the main visa application process.

Four in five (79%) said the quality of written guidance for the endorsement process was good, although participants said there were areas where additional guidance would have been beneficial, such as what types of evidence to include.

Most visa holders surveyed (80%) received the endorsement decision within the amount of time expected. However, a third (33%) cited a faster application process for endorsement as a recommended improvement. In-depth interview participants found the endorsement process more time intensive than the main application.

Nine in ten surveyed (90%) said the main visa application form was easy to complete. In-depth interview participants who had applied for other UK visas said that applying for a Global Talent visa was less burdensome as they did not need to include financial documents or evidence of English language proficiency.

Similar to the endorsement process, most visa holders surveyed (74%) received the visa application decision within the amount of time expected. In the in-depth interviews, visa holders requested more clarity on how long the decision would take to help manage plans.

Views about the fairness of the different fees associated with the visa were mixed. Overall, around three fifths of those surveyed (63%) thought the total application fee was fair, compared with a third (33%) who felt it was unfair. In contrast, a greater proportion said the Immigration Health Surcharge was unfair than fair (59% and 34%). Half (52%) of visa holders surveyed who applied with dependant relatives thought the fees for dependants were unfair, while 46% thought that they were fair.

3.1 Satisfaction with the application process

Overall satisfaction with the application process was high, with 93% of visa holders surveyed saying they were either very or fairly satisfied with the whole process. This was reflected across visa holder types, including both in-country and out of country applicants.

Figure 3.1 Satisfaction with Global Talent visa application process as a whole

Overall, how satisfied or dissatisfied were you with the Global Talent visa application process as a whole?

| Satisfaction | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Very satisfied | 67% |

| Fairly satisfied | 26% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 5% |

| Fairly dissatisfied | 2% |

| Very dissatisfied | 0% |

| Don’t know | 1% |

Base: All participants (307)

The high level of satisfaction with the overall process was reflected in visa holders’ views about the two different stages of the application process: endorsement (92%) and main visa application (86%).

Figure 3.2 Satisfaction with the endorsement and visa application processes

Endorsement application process: How satisfied or dissatisfied were you with the following?

| Satisfaction | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Very satisfied | 72% |

| Fairly satisfied | 20% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 6% |

| Fairly dissatisfied | 2% |

| Very dissatisfied | 0% |

Visa application process: How satisfied or dissatisfied were you with the following?

| Satisfaction | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Very satisfied | 61% |

| Fairly satisfied | 25% |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 8% |

| Fairly dissatisfied | 4% |

| Very dissatisfied | 2% |

3.2 The endorsement process

Choosing an endorsing body

Most visa holders surveyed (83%) felt the eligibility criteria for endorsement were clear. This was reinforced by in-depth interview participants, who described deciding which endorsing body to apply through as straightforward, given they could choose the most relevant endorsing body for their area of expertise.

There is a description of all the different fields of science, that they were well equipped to adjudicate, and my field was listed in there, so I felt quite confident that that was the right one.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

The field of expertise for academics and researchers could fall under more than one of the four “science” bodies (see figure 1.1). Participants said this caused some initial confusion, but upon reviewing the endorsing bodies in more detail, they felt able to decide.

UKVI staff interviewed by the Home Office said that the addition of UKRI as an endorsing body contributed to an increase in applicants applying for endorsement through the wrong endorsing body.

Completing the endorsement application

Visa holders surveyed reported positive experiences of the process of applying for endorsement. Over four in five (84%) visa holders surveyed said the form itself was easy to complete, with the same proportion finding the process open and transparent.

UKVI staff interviewed by the Home Office also thought the endorsement process was working well, describing it as smoother and more straightforward than other visa routes. Staff praised the good communication and leadership in the UKVI team. UKVI staff also found that the switch to electronic submission of evidence was more efficient than posting it. This change was attributed by staff to a move towards greater efficiency within UKVI.

Figure 3.3 Views on the endorsement process

Now thinking about both the different stages of the process (endorsement and visa application), do you agree or disagree with the following statements about the endorsement process?

| Statement | Percentage disagree | Percentage agree | Percentage neither agree nor disagree |

|---|---|---|---|

| There was clear information about how long it would take to receive a decision | 8% | 86% | 5% |

| Application process as open and transparent | 5% | 84% | 10% |

| Application form was easy to complete | 7% | 84% | 9% |

| Criteria of who is eligible to apply was clear | 7% | 83% | 9% |

| Application was clear about the information you’d need to provide and didn’t provide any information you didn’t expect | 5% | 82% | 13% |

| The decision took the amount of time you expected it to take | 15% | 80% | 4% |

| Quality of written guidance was good | 7% | 79% | 15% |

| Time it took to complete and submit the application took much longer than expected | 57% | 30% | 11% |

Base: All participants (307)

While in-depth interview participants also had positive experiences of the endorsement process on the whole, some commented that the endorsement application was more time intensive than the visa application. Participants attributed this to the time required to find and organise their evidence and to identify and contact references.

It was a little surprising how involved the endorsement process was and how effectively uninvolved in comparison the actual visa process was. I got the impression that they were fairly equal in terms of what you need to compile and workload, but the visa process was maybe ten percent of the effort that the actual endorsement was.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

Almost half of visa holders surveyed (47%) said they received help with their endorsement application: one fifth (21%) received help from their place of work, while 16% received help from a family member or friend, and 12% from a lawyer, immigration advisor or immigration representative (see figure 3.4 below). [footnote 12]

Figure 3.4 Help with the endorsement application

Now thinking about the process for endorsement, did you get help from anyone when completing your endorsement application form?

| Help | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Yes, from my place of work | 21% |

| Yes, from a friend or family member | 16% |

| Yes, from a lawyer immigration adviser or immigration representative | 12% |

| Yes, from the endorsing body | 2% |

| No | 51% |

Base: All participants (307)

Visa holders surveyed endorsed by UKRI were more likely than average to say they received help from their place of work (45% compared with 21%). This may be because research organisations supporting an endorsement application to UKRI are required to provide a statement of guarantee and grant paperwork to support their application.

Clarity and guidance on the endorsement process

Four in five visa holders surveyed (82%) thought the endorsement application was clear about the information they needed to provide, and a similar proportion (79%) said the quality of written guidance about the endorsement process was good.

When asked to consider what, if anything, could be done to improve the endorsement process, the most common responses across both the survey and in-depth interviews related to the guidance: two fifths (41%) of visa holders surveyed wanted more guidance about what the endorsement process involves. Similarly, nearly half of visa holders surveyed (47%) wanted clearer guidance on the information they needed to provide (see figure 3.5 below). This was also reflected in the experiences of in-depth interview participants, who described not always being sure what evidence to include in their application for endorsement.

[It asks you to] provide two evidence of innovation, two evidences of impact. What does innovation mean? What does impact mean? Like, what are the metrics for this? If you provide what they say, example, evidence, if you were to provide that you would never get an endorsement. So, like, it’s just super arbitrary.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

Figure 3.5 Suggested improvements to the endorsement process

What, if anything, do you think could be done to improve the endorsement process?

| Improvement | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Clearer guidance on the information you need to provide | 47% |

| More guidance about what the process will involve | 41% |

| A faster application process | 33% |

| Clearer information about how long the process will take | 30% |

| Clarity on who is eligible / criteria for eligibility | 4% |

| Clarity on referee / recommendations | 3% |

| Other | 4% |

| Do not think anything could be improved | 23% |

Base: All participants (307). Responses ≥2%.

Some in-depth interviewees felt advice on the UK government website was too general and did not provide examples specific enough to their circumstances. This made it hard for them to understand what evidence they needed to include. This was particularly the case for those working outside research organisations (such as in creative industries and technology), who felt the guidance was more suited to academics and researchers. This was also reflected in the survey: visa holders endorsed by Arts Council England were more likely than average to disagree that the quality of the written guidance was good (15% compared with 7%).

UKVI staff interviewed by the Home Office noted that many applicants provided more supporting evidence than necessary. This made processing applications more administratively burdensome for staff. UKVI staff recommended clearer guidance on acceptable types and quantities of evidence, as well as more guidance on choosing an endorsing body.

In addition, some in-depth interview participants mentioned issues navigating the gov.uk website, as they found relevant information was spread across different webpages and appendices. In light of this, some in-depth interview participants reflected that a single downloadable guidance document would be useful. While some in-depth interview participants received advice and guidance on the endorsement process through other routes (such as their professional networks or experiences of successful applicants posted online), they felt that this was not sufficient.

In order to make the endorsement process smoother and less burdensome, participants requested more guidance and detail on:

- what information and evidence should be included by people writing recommendation letters

- the specific format that evidence should be uploaded in (such as online links, screenshots or PDFs) and templates to provide evidence in

- the technical expertise of the person reviewing their application, so that they knew whether to include technical explanations and whether the person reviewing would understand the nature of their work

In-depth interview participants also suggested that adapting the guidance to be more specific and include case studies and videos from people with different professional backgrounds would encourage more people to apply (particularly those who may be unaware they are eligible).

Receiving an endorsement decision

Most visa holders surveyed agreed there was clear information about how long it would take to receive an endorsement decision (86%) and received the decision within the anticipated time frame (80%) (see figure 3.3). In-depth interview participants were also happy with the decision-making timescale and noted it was sometimes quicker than expected.

So, once you have the letter, you send it, and it’s supposed to take one week. I got my answer the next day. So, that was really good.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

When asked about improvements to the endorsement process, one third of survey participants (33%) wanted a faster application process, while a similar proportion (30%) wanted clearer information about how long the process will take.

Visa holders surveyed who were endorsed by Arts Council England were more likely than average to suggest improvements to timings: 44% felt the endorsement application process could be faster and the same proportion (44%) said information on timings could be clearer (compared with 33% and 30% overall respectively). This may be because there is no fast-track endorsement process for Arts Council England applicants. Certainly, visa holders with fast-tracked endorsement applications were less likely to say that the application took longer than they expected compared to those whose applications had not been fast-tracked (23% compared with 35%).

On receiving their endorsement, some in-depth interview participants expressed surprise that the confirmation came in the form of an email, as they expected a more formal statement of endorsement. One participant initially mistook the confirmation for a phishing email. Instead, participants suggested that a PDF attachment or certificate would appear more official.

That was quite shocking. I was thinking, ‘Maybe it’s a phishing email or something.’ Because, it didn’t really look real, and because it was a very quick process’.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

3.3 Experience of the visa application process

Completing the application and timings

Overall, visa holders surveyed were positive about the experience of completing the visa application: nine in ten (90%) said the form was easy to complete, with the same proportion saying that the eligibility criteria were clear, and that the application was clear about the information they needed to provide. A similar proportion (85%) felt the visa application process was open and transparent.

Figure 3.6 Views on the visa application process

Now thinking about both the different stages of the process (endorsement and visa application), do you agree or disagree with the following statements about the visa application process?

| Statement | Percentage disagree | Percentage agree | Percentage neither agree nor disagree |

|---|---|---|---|

| Application form was easy to complete | 5% | 90% | 5% |

| Criteria of who is eligible to apply was clear | 3% | 90% | 7% |

| Application was clear about the information you’d need to provide and didn’t provide any information you didn’t expect | 5% | 90% | 5% |

| Application process was open and transparent | 6% | 85% | 8% |

| Quality of written guidance was good | 6% | 85% | 9% |

| There was clear information about how long it would take to receive a decision | 16% | 77% | 6% |

| The decision took the amount of time you expected it to take | 21% | 74% | 4% |

| Time it took to complete and submit the application took much longer than expected | 68% | 22% | 9% |

Base: All participants (307)

In-depth interview participants also reported that the visa application process was clear and straightforward. Those who had applied for other UK visas noted that applying for a Global Talent visa was less burdensome as they did not need to include financial documents or evidence of English language proficiency.

[The visa application process] was okay, that was not a big hassle at all because yes the endorsement is the most important thing. The rest is just like your documents […] and you have to go there [to register your] […] biometric[s] […] On that matter I think that was super, it was quite efficient to be honest.

Global Talent visa holder, in country applicant.

Despite high levels of satisfaction with the visa application process overall, visa holders felt additional guidance would be helpful in a similar way to the endorsement process. When asked what could be improved, a third of visa holders surveyed (33%) said they would have liked more guidance about what the process involves, while 38% wanted clearer guidance on the information they needed to provide. In-depth interview participants also wanted clearer guidance on the process of applying for dependants.

Another area of improvement identified by some in-depth interview participants applying from outside the UK was visa application arrangements in the country they applied from. Some participants found it difficult to get an appointment to register their biometrics. Others felt unsafe at appointments due to an absence of COVID-19 safety measures or commented that visa centre staff were unhelpful. However, this appeared largely confined to a few specific visa registration centres, rather than a wider issue across centres.

While over three quarters of visa holders surveyed (77%) felt that there was clear information about how long it would take to receive a decision, 31% felt the visa application process could be improved by having clearer information on timings. Visa holders surveyed who were endorsed by Arts Council England were more likely than average to want clearer information on timings (43% compared with 31% overall). Similarly, around three quarters of visa holders surveyed (74%) received a decision within anticipated timescales, while a third (33%) felt the process would be improved by being faster.

In-depth interview participants were generally satisfied with application decision-making timescales. Some participants who had been advised by the visa registration centre that a decision could take up to three months were surprised at how quickly they had received their visa. While this was positive for some, the unexpectedness of this created inconvenience for others. For example, one participant who expected the process to take longer was then unable to move to the UK within the three-month period on their entry clearance stamp. Overall, in-depth interview participants felt a clearer indication of how long a decision would take would be helpful for future applicants.

Global talent visa fees

Views on Global Talent visa fees were mixed. Overall, almost two-thirds of visa holders surveyed (63%) felt the total application fee (including the endorsement and visa application fee) was fair, while a third (33%) felt it was unfair. In contrast, when asked specifically about the Immigration Health Surcharge, a greater proportion (59%) thought it was unfair than fair (34%).

For both fees, visa holders surveyed who were fast-tracked were more likely than those who were not fast-tracked to say that the fees were unfair, although the reasons for this are not clear:

- 46% of visa holders whose applications were fast-tracked said the overall application fee was not fair compared with 25% whose applications were not-fast-tracked

- 66% of those whose applications were fast-tracked said the Immigration Health Surcharge fee was unfair, compared with 55% those whose applications were not fast-tracked

In-depth interview participants also expressed mixed views towards the application fees. Those who were more favourable thought the fees provided value for money given the benefits associated with the visa (including access to healthcare and a route to settlement in the UK). However, some participants felt the fees were unfairly high, particularly those endorsed by Arts Council England who had faced challenges in finding work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Others felt the fees were too expensive given the overall intention of the visa to attract talented people to the UK. In some cases, participants had their fees paid for by their place or work, or the costs were included as part of their funding or fellowship.

Figure 3.7 Opinions on the fairness of the fees of the Global Talent visa

Thinking about the costs involved in the application process and the benefits attached to a Global Talent visa, to what extent do you think the fee for each of the following was fair or unfair?

| Fairness of fee | Percentage unfair | Percentage fair | Don’t know |

|---|---|---|---|

| The total application fee (including endorsement and visa application) | 33% | 63% | 5% |

| The annual immigration health surcharge | 59% | 34% | 7% |

Base: All participants (307)

Two in five visa holders surveyed (41%) felt that clearer information on the Immigration Health Surcharge would improve the visa application process. Similarly, in-depth interview participants had not always expected this fee, or the requirement to pay for all years at once. As a result, some in-depth interview participants reduced the number of years they applied for, while others borrowed money from family members to cover the fees or used their savings. A number of in-depth interview participants fed back that the Immigration Health Surcharge payment should be staggered to make it more affordable and manageable.

A few in-depth interview participants also highlighted difficulties in paying the Immigration Health Surcharge and felt that the process could be simplified. For example, one participant was unable to use a European credit card. Another participant was unable to pay for the number of years they wanted due to the currency exchange rate and credit card limits. A specific challenge raised by some in-depth interview participants who applied in-country and switched onto the Global Talent visa was the process of obtaining a refund for Immigration Health Surcharge payments already made for years outstanding on their previous visa. Participants in this situation said that the guidance on how to obtain a refund was not clear.

Looking specifically at the fees for additional dependant relatives (such as a partner or child), 52% of visa holders surveyed who applied with dependant relatives thought the fees associated with this were unfair, while 46% thought that they were fair. In-depth interview participants generally considered the fees for dependants to be expensive. Some in-depth interview participants struggled to pay the fees: one participant was unable to afford the fees for their whole family, which resulted in relatives living apart. Much like the Immigration Health Surcharge, participants suggested a staggered approach to payments.

Chapter 4: Professional contributions and future intentions

This chapter outlines findings on visa holders’ professional experiences and perceived contribution to the UK, as well as their views regarding settling in the UK in the future.

Visa holders’ professional experience in the UK was generally positive. Most visa holders surveyed were in employment of some kind (95%) and almost all (99%) agreed that their current job suited their skills and experience. The most common annual salary band was between £31,200 and £51,999 (49%).

In open-end survey responses, the most common type of professional contribution visa holders said they had made related to conducting a wide range of research (30%), while 7% of visa holders surveyed mentioned presenting and publishing books and academic papers. In-depth interviews revealed that some participants planned to publish and present their research in future, although they were not yet at this stage.

Responses from in-depth participants demonstrated the diverse contributions of visa holders across their areas of expertise. Participants felt that their professional achievements were enabled by factors that contributed to the decision to apply for the visa – for example, the flexibility of not being tied to one employer. This flexibility also afforded participants greater opportunities to negotiate pay or promotion, due to the comparative ease of switching jobs and employers.

Access to specific UK job markets and experts in these areas were said to have created professional opportunities for participants, facilitating their contribution to the UK. However, the COVID-19 pandemic had limited access to some sectors, such as the arts.

While in-depth interview participants identified some potential barriers to settlement in the UK identified (such as the impact of the UK leaving the European Union), most spoke about their intention to settle. Participants were motivated by the opportunity to build on the contributions they had already made and access to professional networks in the UK relative to other countries. Other benefits of settlement included personal networks, feeling welcome in the UK, and access to government-funded health and education services.

4.1 Employment status and wages

On the whole, visa holders’ professional experience in the UK was positive. Most visa holders surveyed were in employment of some kind (95%) and almost all (99%) agreed that their current job suited their skills and experience.

- Three quarters of visa holders surveyed (75%) were in full-time paid employment. Researchers and those sponsored by UKRI and the Royal Society were more likely than average to be in full-time paid employment (89% of academics and 96% of those sponsored by UKRI and the Royal Society, compared with 75% overall). [footnote 13]

- One in six (17%) visa holders surveyed were self-employed. Those surveyed endorsed by Arts Council England and those in the creative industries were more likely to be self-employed than average (63% and 73% respectively, compared with 17% overall).

- Fewer visa holders were in part-time employment (3%) or unemployed (2%).

Figure 4.1: Employment status

Which of the following options best describes your current employment situation?

| Employment status | Percentage |

|---|---|

| In full-time paid employment (including if you are on furlough) | 75% |

| Self-employed | 17% |

| In part-time paid employment (under 35 hours per week including if you are on furlough) | 3% |

| Unemployed | 2% |

| Other | 2% |

Base: Participants currently living in the UK on a Global Talent visa (283)

Around half of visa holders surveyed (49%) had an annual salary of between £31,200 and £51,999. This rose to nearly three-quarters (72%) of those working in academia.

One-fifth of visa holders surveyed (22%) were earning between £52,000 and £149,999, which rose to 60% among those endorsed by Tech Nation. Those endorsed by Tech Nation also exclusively made up the 3% of visa holders earning more than £150,000.

Just under a fifth of visa holders surveyed overall (18%) were earning less than £31,199. Those endorsed by Arts Council England and those working in creative industries were more likely than average to be earning less than £31,199 (53% and 57% respectively).

Figure 4.2: Annual salary before tax

What is your current annual salary before tax?

| Annual salary | Percentage |

|---|---|

| £150,000 or more | 3% |

| £52,000 - £149,999 | 22% |

| £31,200 - £51,999 | 49% |

| £15,600 - £31,999 | 14% |

| Under £15,600 | 4% |

Base: Participants currently living in the UK on a Global Talent visa and who are currently employed (268)

4.2 Professional contributions

A majority of visa holders surveyed (89%) named a way they had contributed professionally to the UK or to their field of work since their visa was granted. Looking at open-ended question responses, the largest proportion of visa holders said their contribution related to conducting research (30%). This was higher than this average among those surveyed who worked in academia (50%), and those endorsed by UKRI (62%) and Royal Society (48%). This is likely to reflect he high proportion of academics and researchers endorsed by these bodies. Related to this, 7% of visa holders surveyed mentioned presenting and publishing books and academic papers. In-depth interviews revealed that many visa holders working in research were not at this stage yet but planned to publish and present their research in future.

One in ten visa holders surveyed (10%) mentioned contributing through teaching or mentoring. This was more common than average among those endorsed by Arts Council England (21%) and those working in the creative industries (24%). This may reflect a shift in focus among those working in the creative industries with fewer opportunities to perform or exhibit work during the COVID-19 pandemic: just 2% of participants mentioned performing or putting on exhibitions. Other responses varied from conducting wider academic work (5%) and setting up a business (5%).

Figure 4.3: Participants’ contributions to the UK and to their field of work

| Field of work | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Conducted research | 30% |

| Teaching / mentoring | 10% |

| Developing new technology / materials | 8% |

| Publishing books and research papers | 7% |

Survey responses and in-depth interviews demonstrated the diverse contributions of visa holders, which mirrored their diverse areas of expertise. Alongside the themes above, some other notable contributions included:

- researching and developing new systems and processes, for example, supporting international cooperation on global issues such as human rights or cyber-security, or improving NHS systems

- developing new products, such as financial products and new sustainable materials

- researching and developing new medical treatments (such as cancer treatments)

- providing advice to companies to support their growth

- community development work through the arts

- supporting the effort to combat COVID-19, with contributions ranging from conducting scientific research to understand how the virus is transmitted, developing new types of face masks, and research into the diagnosis and treatment of patients

When asked in the in-depth interviews, visa holders felt that their professional achievements had been enabled by similar factors that appealed to them when deciding to apply for a Global Talent visa (explored in Chapter 2). Participants described how the flexibility and duration of the Global Talent visa facilitated their professional development and contribution in several ways. As a result of not being tied to a specific employer, in-depth interview participants said they were able to make more valuable, diverse and innovative contributions.

For some, this meant that they were able to carry on consultancy or freelance work, opening up opportunities to contribute to projects that some felt would not be available under a Skilled Worker (formally Tier 2) visa. For example, one participant working for a “small and innovative” start-up company felt this would not be possible under a Skilled Worker (formally Tier 2) visa as, in their experience, these types of company rarely had the internal processes necessary to sponsor talented people from overseas.

I have freedom in terms of working with different employers with start-up employers that don’t even have the ability to sponsor someone from outside of the UK. Also, normally the companies that do the development and innovation it’s normally small start-up companies where they rely on funds so these companies are not normally fully established, and they cannot sponsor people.

Global Talent visa holder, in-country applicant.

Some participants felt that this flexibility afforded them greater opportunities and confidence to negotiate pay or promotion, as they were not tied to one employer. Participants also linked the reputation of the visa to securing prestigious positions, by giving them a competitive edge.

If I’m applying for any job, any position, and they come to know that I am holding a Global Talent visa, they do give me priority over the other candidates …this is the [biggest] advantage of the Global Talent visa.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

More generally, the stability and flexibility of having a Global Talent visa gave participants greater peace of mind that they would not have to leave the UK after a certain period of time and uproot their personal lives. This meant they could be creative and focus on their career development, as well as look ahead to a future in the UK (explored further below).

Case study 1: contribution to the UK

Before switching to a Global Talent visa, Kareem was working in the UK on a Tier 2 visa in the technology industry. He remained at the same company once his Global Talent visa was granted and negotiated a pay rise – which he attributed to the flexibility afforded by the Global Talent visa to shop around for offers from different employers.

Kareem appreciated the freedom afforded by the Global Talent visa to undertake consultancy work for different employers. This allowed him to offer his skills to companies to solve problems and support their growth and also increased his UK tax contributions as a higher rate taxpayer.

Due to the stability and earning potential afforded by his visa, Kareem bought a house and had moved his savings and investments to the UK. He hoped to remain in the UK long-term and take advantage of the accelerated route to settlement.

Kareem is pleased with the opportunities for tech growth in the UK – including outside London in cities across the UK and planned to set up his own tech business once he settles in the UK.

Access to specific UK job markets was said to have created professional opportunities for participants, facilitating their contribution to the UK. For example, those endorsed by Tech Nation highlighted the buoyancy of the UK economy and the large, diverse and growing technology sector as providing fulfilling career opportunities. Where participants owned businesses, for some the UK provided a platform to expand globally and was said to open up markets in both Europe and the USA. Participants attributed this to the favourable time zone for working with companies globally, as well as a similar work culture and expectations in the UK compared with American companies.

From the UK we’ve got much higher horizons of doing business globally […] we see that in Europe we are being perceived well in innovative communities.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

Case study 2: contribution to the UK

After completing her PhD in her home country in a very specialised area of microbiology, Sofia moved to the UK to pursue an exciting job offer from a small science start-up company in a large UK cities outside of London.

Sofia was happy to work in an environment where her knowledge and expertise were valued and did not think she would have found another job that was so suited to her skills and experience.

Since starting the position, Sofia felt that she was able to make an important contribution to the company at a pivotal point in their trajectory. She enjoyed spending time with her colleagues in the lab and working as part of a team of like-minded people who share her interests. She described the city she lives in as a friendly, vibrant place where she hopes to settle with her partner in the future.

All these factors facilitated collaboration, which was said to be further enabled by the general diversity of UK cities (and London in particular). This contrasted with initial concerns held by some participants about potential negative attitudes towards immigrants in the UK, and the potential for racism and discrimination; some feared the UK had become less welcoming following its departure from the European Union. Despite these fears, most participants said they had been welcomed and had a positive experience since arriving in the UK, although some European citizens said they felt a general sense of being unwelcome in the UK.

[People in the UK are] open to build trust to welcome new people, new members, immigrants and that’s amazing. The UK is very open towards new people, towards new businesses. They don’t perceive us as competitors, they perceive us as contributors, as synergetic, you know, mutually beneficial partners […].

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

Case study 3: contribution to the UK

Matias was conducted postdoctoral biomedical research into treatments for diseases. His supervisor recommended that he apply for a Global Talent visa when his postdoctoral research contract was coming up for renewal, so that he could continue his research. As a Global Talent visa holder, Matias no longer felt stressed about having to leave the UK once his contract ended and felt he had more control over his career.

Since being granted a Global Talent visa Matias published research papers, collaborated with other researchers on publications and exhibitions and worked on a STEM summer school project for students.

Matias felt being in the UK has made a positive difference to his career. The laboratory where he conducted his research was supportive and diverse and he had found interesting people to collaborate with on his research.

I have a lot of opportunities here to grow professionally. I’ve got good collaborators. Even within the lab, we are a diverse team, we are people from every place. It’s a good work environment.

Living in a large, diverse city also helped Matias to feel welcome and accepted in his new home. He was planning to apply for permanent residency soon.

While a majority of visa holders surveyed said they had made some kind of professional contribution, 7% said that they did not know what they had contributed, and 1% said that COVID-19 had disrupted their plans. Where in-depth interview participants felt that they had not had the opportunity to contribute, this was generally because they had only recently moved to the UK, or due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic was also said to have made it harder for some to integrate into new positions

Since I’ve been here, I’ve been to [the university] once, and that’s one of the biggest problems for me because we need that socialisation environment for your progress. So, then you’ll stay at home all the time, it is not good for improving your personal skills.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

For those working in the creative industries the closure of venues (including concert halls, theatres, galleries and museums) reduced job opportunities.

There’s a lot of work that I would like to be doing but haven’t been able to reach the networks of because they’re so shuttered by COVID-19.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

Case study 4: contribution to the UK

After finishing her masters in London, Amara applied for the Global Talent visa to continue working as an artist. She felt her artistic contributions were recognised, valued and supported in the UK, comparing this favourably to her experience in her home country. She also felt that art was not as appreciated in her home country compared to the UK.

Amara planned to use her art and work with other artists to develop communities, with a focus on young people. She was applying for grants for projects as the creative industries recovered from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Amara felt that being endorsed by the Arts Council made her more respected professionally and had opened the door to new opportunities. Since her visa was granted, she had joined the board of an international arts body and felt she was making a positive difference in the arts industry.

Amara was considering settling in the UK in the future with her dependants and was excited about the positive impact she would be able to make through her work with local UK communities.

In-depth interview participants also spoke about their plans for future contributions. These included:

- academic contributions such as ongoing publications and conferences and generally continuing to build the reputation of their research institution

- creative contributions to the arts, such as holding concerts and tours and open studios or theatres

- starting or growing companies, including expanding into new global markets

Some in-depth interview participants said that additional support to find employment in the UK for themselves and their dependants would be helpful. Specifically, they mentioned: guidance on how to apply for a National Insurance number and how to register as self-employed; information about paying taxes in the UK; and advice from endorsing bodies about where to find job opportunities relevant to their, or their partners’, field of work. Some felt this additional support would attract more international talent from creative fields and also young researchers.

The other difficult thing to navigate for me has been […] which taxes I have to pay […]. None of that was on my radar until I called a tax professional and he told me all about it after I moved here. […] [It] could be a little more transparent, I think. At least make us aware that we’re going to have to look into that for ourselves.

Global Talent visa holder, out of country applicant.

4.3 Looking to the future

While views on settlement were not directly explored in the survey, the relative attractiveness of the opportunity to settle, compared with other aspects of the visa, was explored among those who said the visa was an important factor in their overall decision to live and work in the UK. Among this group, a high proportion (78%) selected the opportunity to settle and three in five (60%) were attracted by the accelerated route to settlement.

In-depth interview participants highlighted the additional security settlement would give to them, their families and their careers / businesses. Some thought the additional security would enable them to be more productive in their professional lives.