G7 Carbis Bay progress report: advancing universal health coverage and global health through strengthening health systems, preparedness and resilience

Published 3 June 2021

Acknowledgements

The Presidency wishes to thank the G7 Accountability Working Group (AWG) members for their contributions in preparing case studies and examples of best practice for use in the report, as well as their comments and inputs during the development of the text.

Special thanks are also due to the international organisations and UN agencies that took time to provide information and data on their work on health system strengthening, Universal Health Coverage and preparedness for public health emergencies, and on G7 contributions to their activities and programmes in these sectors.

Finally, the UK Presidency would like to thank Dan Whitaker, Tim Shorten, and Public Health England Registrars Rachel Handley and Daniel Stewart for their support in preparing this report.

Throughout the report we use footnotes (Roman numerals – i, ii, iii etc.) and endnotes (Arabic numerals – 1, 2, 3 etc.) to provide additional information. Footnotes provide additional explanation on key points in the main text. Endnotes provide source information for supporting evidence.

G7 Accountability Working Group

Accountability and transparency are core G7 principles that help maintain the credibility of G7 leaders’ decisions. At the Summit in 2007 in Heiligendamm, Germany, G8 members introduced the idea of building a system of accountability.

In 2009, the Italian presidency formally launched the mechanism to achieve this accountability in L’Aquila and approved the first preliminary Accountability Report and the Terms of Reference for the G7 Accountability Working Group (AWG). Since the first comprehensive report was issued at Muskoka in 2010, the AWG has produced a comprehensive report reviewing progress on all G7 commitments every three years, along with sector- focused accountability reports in interim years.

These reports monitor and assess the implementation of development and development-related commitments made at G7 leaders’ summits, using methodologies based on specific baselines, indicators, and data sources. The reports cover commitments from the previous six years and earlier commitments still considered to be relevant. The AWG draws on the knowledge of relevant sectoral experts and its reports provide both qualitative and quantitative information.

Ministerial foreword

More than a year has passed since the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency. COVID-19 has destroyed lives and livelihoods around the globe, and has disproportionately affected the poorest and most vulnerable and marginalised, including women and girls. Its indirect impacts have seen essential health services, such as routine immunisations for children, disrupted.

However, it has also galvanised collective international action and shown the value of a shared response. The rapid development of vaccines has shown the power of human ingenuity. G7 Leaders are committed to accelerating global vaccine development and deployment to bring the pandemic to an end.

Accountability and transparency are core principles of the G7 and essential for the credibility of the decisions of Leaders. That’s why we measure the implementation of development commitments made at G7 Summits through regular G7 Progress Reports.

As we work to beat COVID-19 and build back better, this year’s report focuses on global health. Given the impact of the pandemic around the world, the report reviews progress against existing G7 commitments to work with low- and lower- middle income countries and our partners to build stronger health systems, achieve universal health coverage and improve global health security.

These commitments were made in the wake of the devastating Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2015 and as all countries committed to the ambitious vision of the Sustainable Development Goals.

We recognise that building resilient, equitable and inclusive health systems are the foundation for achieving our commitments. This means keeping our focus on leaving no one behind, promoting better health and well-being for all by ensuring that everyone, everywhere, has access to the quality health services they need, without the risk of being pushed into poverty.

It also means building resilience, protecting health and well-being, and taking a holistic One Health approach. This is about recognising the interconnections between human health, animal health and the health of our environment, and therefore tackling a wide range of threats including zoonotic diseases, antimicrobial resistance, and the health impacts of climate change.

This report sets out the encouraging progress that we have made on our existing commitments. But of course we know that there is much more to do.

G7 Leaders are committed to working together to shape a global recovery that promotes health and prosperity for all. Under the UK’s G7 Presidency and the Leaders’ Carbis Bay Summit – as well as through the efforts of G7 Foreign and Development, Finance, and Health Ministers – the G7 is showing its determination to continue leading the global recovery from coronavirus while also strengthening global resilience against future pandemics.

The Rt Hon Dominic Raab MP, First Secretary of State and Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs

The Rt Hon Matt Hancock MP, Secretary of State for Health and Social Care

Executive summary

At the 2015 G7 Elmau Summit, the 2016 Ise-Shima Summit and the 2017 Taormina Summit, G7 Leaders made ambitious commitments to work with low- and lower- middle income countries (LICs and LMICs) towards attaining Universal Health Coverage (UHC) with strong health systems and better preparedness for public health emergencies, and preventing and responding to future outbreaks.

This report reviews the progress made against these G7 commitments, which are assessed together because UHC and Global Health Security (GHS) are interlinked goals. Strong health systems are the foundation for UHC, for GHS and for sustainable progress in global health. Both UHC and GHS are important if we are to achieve health-related Sustainable Development Goals, leave no one behind, and to support overall economic growth and poverty reduction.

These commitments were built on longstanding G7 support to advancing global health. They reflected the renewed ambition set by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and responded to the urgent need exposed by the Ebola outbreak in West Africa for strong systems to prevent, detect and respond to health threats.

Developments since the commitments were made have underlined their continuing importance. At the UN High-Level Meeting on UHC in 2019, the global community recognised that the goal of UHC will not be attained by 2030 at the current rate of progress and came together to reaffirm political commitment and action to achieve this goal. Other health emergencies since 2015, including further Ebola outbreaks, Zika virus disease and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic have emphasised the need for strong public health systems.[footnote 1]. The UN Secretary-General recently highlighted how the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are further exacerbating these challenges and may seriously impair or reverse progress towards the SDGs.

Overall, G7 members have made considerable progress on their commitments through:

- mobilising financial and technical support for health systems, including essential pillars such as the health workers that enable the delivery of essential health services

- mobilising action on health systems through multilateral partners and in collaboration with international movements, such as UHC 2030

- working with LICs/LMICs to evaluate and develop the public health capacities required by the International Health Regulations (IHR) to prevent, detect and respond to public health events and emergencies and

- financing and providing assistance to key international mechanisms that support flexible and swift emergency responses in LICs/LMICs during pandemics and health emergencies

This has enabled G7 members to contribute to important achievements and impact. G7 members’ financing for health system strengthening rose from 38% in 2015 of all donor disbursements for general health to 47% in 2019. (footnote i) G7 support has contributed to partner countries’ efforts, including through domestic resource mobilisation, to achieve Universal Health Coverage and improve health security. There is evidence of progress, such as increases in health workers, with 14% more doctors and 17% more nurses and midwives reported across all World Health Organization (WHO) regions between 2015 and 2020. The G7 members have used their influence and leverage in key multilateral agencies and partnerships to strengthen the focus on and funding of health system strengthening and UHC. In the case of Gavi, The Vaccine Alliance, health system strengthening has grown from 21% of total spend in 2016 to 31% in 2019.

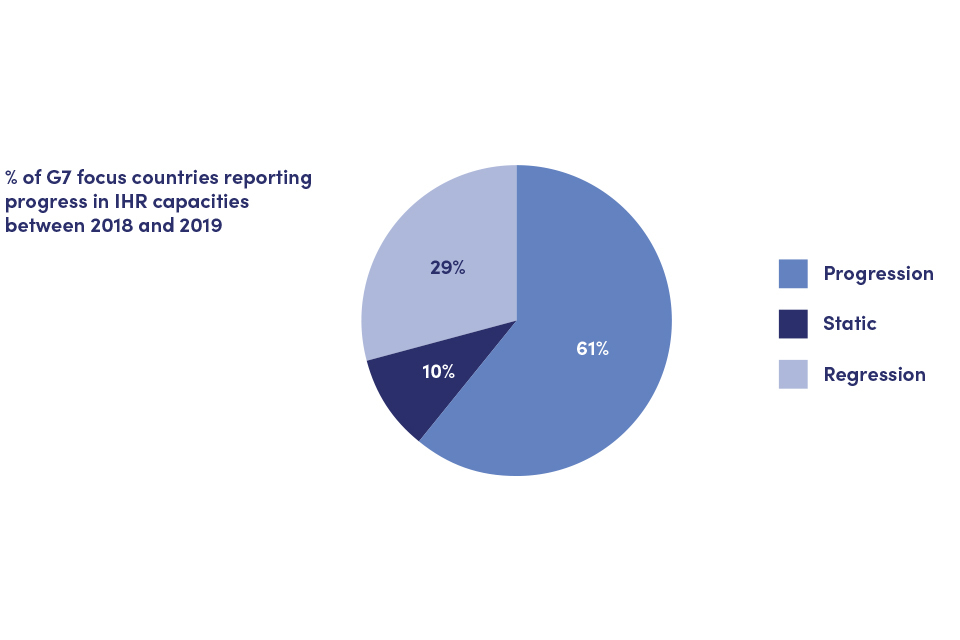

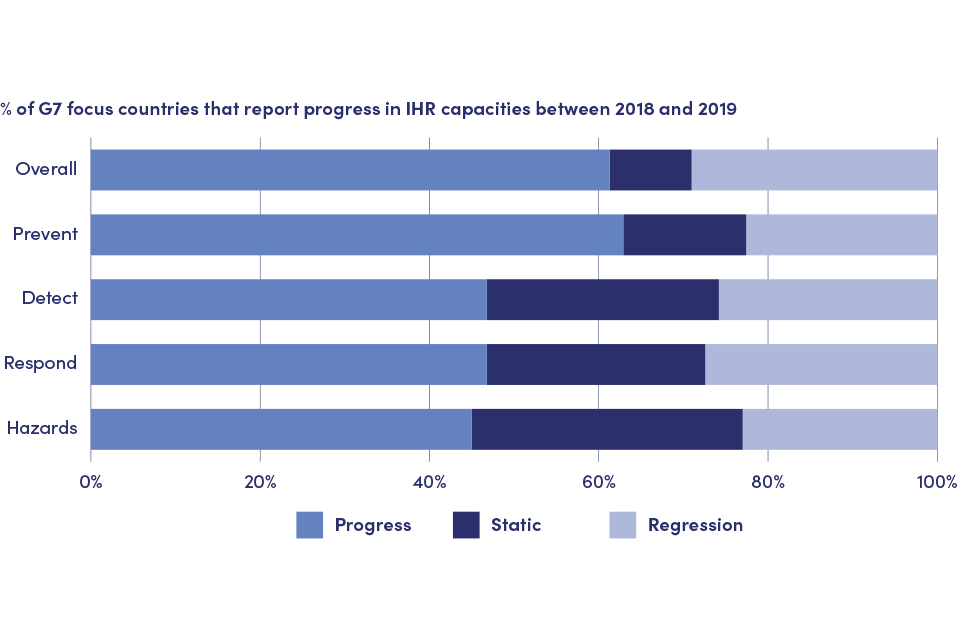

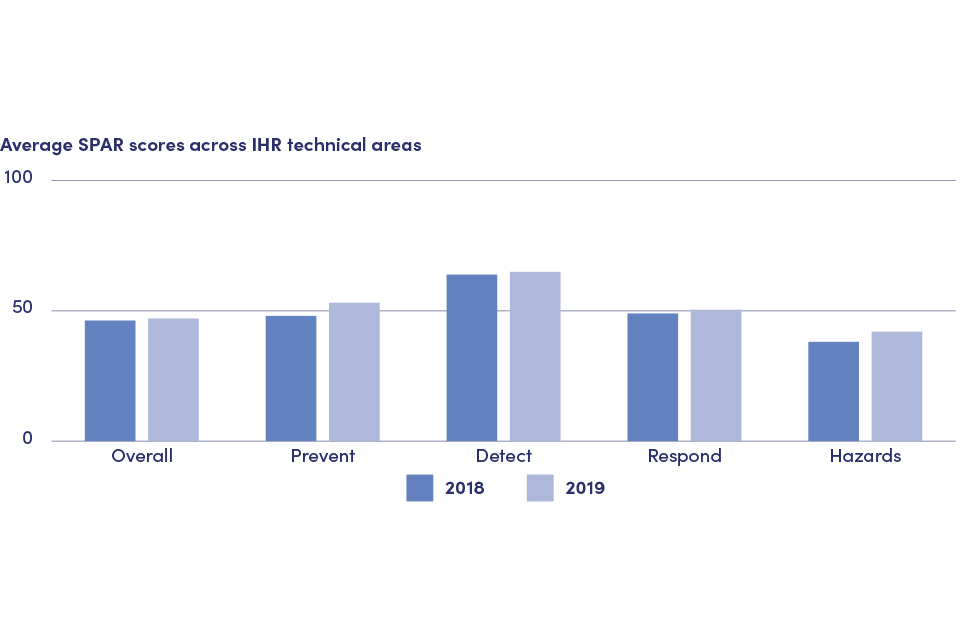

G7 support has also contributed to understanding and strengthening partner countries’ national core capacities to implement and comply with the IHR. This has enabled 61% of countries supported by the G7 to make progress in strengthening these capacities, which will support more effective responses to future emerging threats. G7 members’ support for emergency response financing mechanisms has enabled the WHO Contingency Fund for Emergencies (CFE) to release 43 separate allocations for 23 emergencies (footnote ii) in 22 countries in 2019. 84% of allocations were within 24 hours of request.

G7 members have acted collectively and individually to meet these commitments, with progress measured by a set of eight indicators agreed by the G7 Accountability Working Group. Case studies throughout the report illustrate the efforts being made by different G7 members.

Overall, G7 members have made considerable and important investments in health systems, UHC and GHS. However, at the current rate of progress, the goal of UHC will not be achieved by 2030 and there remain significant gaps that need to be addressed in order to strengthen health security. The challenges for achieving the SDGs, including on health, by 2030 remain significant, especially with the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. There is no room for complacency. The G7 continues to support LICs and LMICs to improve health outcomes and equity, and to strengthen our collective, global capacity to prevent, detect and respond to health emergencies in the spirit of solidarity and partnership.

Chapter 1: The context for the G7 commitments

Headline messages

-

the G7 made commitments on global health and health security in 2015 against a backdrop of the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals, and emerging threats to global health, mostly notably the Ebola outbreak in West Africa. These threats further exposed and reinforced the urgent need for collaboration and investment in systems to prevent, detect and respond to public health events. Since that time, health emergencies including further Ebola outbreaks, Zika and the COVID-19 pandemic have underlined the importance of this agenda

-

weaknesses in health systems, including barriers that marginalised populations may face, have been found to contribute to the slow progress towards global health goals, particularly in LICs and LMICs. In response, the global community has primarily sought to support LIC and LMIC governments in their health systems strengthening activities, especially through a primary health care approach, to make progress towards realising Universal Health Coverage (UHC)

-

developments since 2015 further underline that health system strengthening is not only essential for achieving UHC, but also for advancing Global Health Security (GHS). The world will only be prepared for ongoing and future public health threats if effective health systems are in place

-

health system strengthening, UHC, and GHS are interdependent, as are G7 commitments to all three agendas

-

a greater understanding of the complex nature of public health threats has highlighted the need for a multi-sectoral approach that goes beyond traditional health agendas, including through a One Health approach to global health (one that recognises the interconnections between human health, animal health and the health of our environment) to address antimicrobial resistance, zoonotic diseases (those that spread from animals to humans), emerging infectious diseases, and the impacts of climate change

Global health has been a long-standing priority for the G7. Health issues, such as HIV/AIDS, women and girl’s health, and sexual and reproductive health and rights, have consistently received the attention of G7 Leaders [footnote 2]. Support for coordinated international efforts to achieve the highest attainable standard of health for all, and the systems that deliver this, is in everybody’s interest.

In line with the remit of the Accountability Working Group (AWG) to monitor progress against the development-related commitments G7 Leaders have made, this report focuses on existing G7 Leaders’ ambitious commitments that seek to support the achievement of Universal Health Coverage (UHC) and Global Health Security (GHS) through strengthening health systems (Box 1).

Summary of G7 commitments reviewed in this accountability report

Commitment 9: Strengthen health systems, through bilateral programmes, multilateral structures and support to country-led health systems strengthening; promote Universal Health Coverage (UHC); and increase skilled health workforce.

Commitment 10: Prevent future outbreaks from becoming epidemics, support the implementation of International Health Regulations (IHR) through a coordinated approach, including through the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) and other multilateral initiatives, enable better preparedness, and swift initial responses by the WHO and other relevant organisations.

Why were these commitments important in 2015?

The West African Ebola outbreak that began at the end of 2013 tested collective global efforts for health security, and exposed alarming weaknesses in national health systems, public health functions, and international response efforts [footnote 3]. It was evident that achieving health security would require greater collective action to support progress to systematically assess and implement the core capacities required by the International Health Regulations (IHR) (footnote iii) and to prepare for future outbreaks of a similar nature [footnote 4].

This period also saw significant commitments from the international community in support of UHC and health system strengthening to address existing and often longstanding health needs and inequalities. Collective action on global health gained further traction through the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, when all UN Member States committed to the delivery of Universal Health Coverage by 2030, a goal which was re-affirmed in the UN Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage in 2019 [footnote 5]. Health system strengthening as been increasingly recognised as central to global health and critical to delivering equitable and sustainable health outcomes.

Box 1: Definitions of Universal Health Coverage, Health System Strengthening and Global Health Security

|# Universal Health Coverage (UHC) | Health system strengthening | Global Health Security (GHS) |—–|—-|—-| | Aims to achieve equity in health, where all individuals and communities receive the health services they need, when and where they need them, without suffering financial hardship | Comprises of strategies to improve a country’s health care systems to ensure better access, coverage, quality, or efficiency of health care functions | Is a state of freedom from the scourge of infectious disease, irrespective of origin or source. It is achieved through the policies, programmes, and activities taken to prevent, detect, respond to, and recover from biological threats.

[footnote 6], [footnote 7], [footnote 8]

The timeline, shown in Figure 1, charts G7 commitment to health systems strengthening, UHC and health security over the past two decades as part of the wider emphasis that the G7 has placed on improving global health outcomes during this period. Across this period, the G7 has made commitments in response to emerging threats, and in the context of the urgent need for coordinated support to promote the objectives of UHC and GHS through strengthening health systems. The timeline also reflects the growing international focus on cross-cutting global health threats such as climate change and antimicrobial resistance over this period.

British and Sierra Leonean medics work together at Connaught Hospital, Freetown Credit © Simon Davis/DFID

Figure 1: Timeline – global health threats, G7 commitments on global health, and significant events in terms of GHS, UHC and HSS

| Pre-2005 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global health threats: outbreaks & recognition of long-term problems | HIV, H5N1, SARS | H1N1 | MERS | Ebola | WHO announce PHEIC; Wild polio virus | Zika | Climate change;AMR | Climate change | COVID-19 | ||||||||

| G7 | Global Fund established in 2002 with significant support from G8 | G8 Toyako commit to investing in HSS | G8 Muskoka Declaration commits to HSS to reduce maternal, newborn and child deaths as part of the Muskoka Initiative | G7 Brussels Declaration recommits to HSS and endorses the Global Health Security Agenda | G7 Elmau commitment to UHC, HSS and GHS | G7 Ise-Shima agreements build on multi-sector work for GHS such as AMR and commit to support 76 countries in health emergency preparedness | G7 Taormina communiqué recommits to HSS and GHS | G7 Charlevoix communiqué recommits to HSS and GHS | G7 Health Ministers Meeting in Paris in 2019 endorses primary health care for UHC | ||||||||

| GHS | World Health Assembly adopts revised IHR | International Ministerial Conference Sharm el-Sheikh release One World One Health strategy & FAO-OIE-WHO Tripartite forms | FAO-OIE-WHO Tripartite strategic agreement on animal-humanecosystems interfaces G | WHO adopt the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework | Global Health Security Agenda launched | WHO develops Joint External Evaluation tool for IHR UN General Assembly High-Level Meeting on Antimicrobial Resistance | FAO-OIE-WHO Tripartite MoU on cooperation to tackle health risks at animal-human-ecosystems interface | WHO Health Emergency and Disaster Risk Management Framework; WHO launches pilot REMAP resource to support NAPHS | First meeting of One Health Global Leaders Group on Antimicrobial Resistance | ||||||||

| UHC | World Health Report: highlighting the need for investing in health | Ten year anniversary of the Abuja Declaration by African Union Members to increase health budgets | UN General Assembly endorses UFC | UHC included as core part of Sustainable Development Goals | WHO Astana Declaration on primary health care in UHC | UN General Assembly High Level Meeting on UHC | |||||||||||

| HSS | Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness highlights need for more co-ordinated health system financing for UHC; WHO Montreux Challenge to develop Global Health Systems Action Network | International Health Partnership (IHP+) forms to progress MDGs through more coordinated action on health aid and HSS WHO publishes HSS framework | IHP+ transforms into UHC2030 to respond to SDGs | Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All launched at UN General Assembly |

Developments since 2015: why these commitments have remained important

Since 2015, stalling progress in existing disease control efforts and the additional complex and emerging threats to national, regional and global health security, including Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), Ebola and Zika virus, and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, have influenced global understanding of what is needed to make progress on health system strengthening and towards UHC and GHS [footnote 9].

COVID-19 has shown that there remain weaknesses in the health systems and public health functions (footnote iv) critical for improving health outcomes and for health security at national, regional and international levels, including preventing, detecting and responding to the threat of a pandemic. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board set out the need for increased preparedness for global health emergencies, including the need to strengthen compliance with the International Health Regulations (2005) and for effective, accessible and efficient local health systems to support both preparedness and better health outcomes. In 2019, WHO forecasted that as many as five billion people could be left without full access to essential health services in 2030 if progress towards UHC did not accelerate, coverage would need to double in order to reach the SDG target of UHC for all by 2030. COVID-19 has also, at least in the short-term, worsened access to essential health services, further affecting progress towards UHC.

The burden of COVID-19 has struck inequitably at both a national and international level. In countries across the world, the most vulnerable are frequently those that have been hit the hardest by the pandemic. Successful responses to COVID-19 at a country-level have often been associated with how resilient, well-led and well-funded their health systems have been [footnote 10]. The COVID-19 pandemic has also demonstrated close links between its health and economic effects. For the first time in 20 years, global poverty may have increased with between 88 and 93 million additional people estimated to be living in extreme poverty in 2020 [footnote 11].

And yet the pandemic has provided an opportunity for the international community to take a renewed focus on global health, the need to strengthen health security, including through sustainable financing, and develop strong, well-resourced, resilient and inclusive national and international systems in health and other sectors. Though challenges undoubtedly remain, the success the international community has had in harnessing the power of science and innovation through initiatives such as the Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-A) and its COVAX facility has underlined the power of collaboration at an international level in ensuring the world can better respond to public health emergencies of international concern (PHEICs) [footnote 12].

The interaction of health system strengthening, UHC and GHS

It is important to recognise that UHC and GHS are interdependent, that strengthening health systems provides the basis for both UHC and GHS, and that all are necessary to achieve the SDG health-related goals.

Health system strengthening is what we do; universal health coverage, health security and resilience are what we want.

Kutzin & Sparkes, Bulletin of the WHO, 2016

Mobile health services reach herder families in remote areas of Mongolia. September 2016. ©WHO/Mongolia

UHC, by definition, includes access to the full spectrum of services including health promotion, prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care. Increasing access to quality and affordable health services through primary health care (PHC) supports healthier, more resilient populations and helps equip communities to prevent and respond to health threats like pandemics, antimicrobial resistance and the health impacts of climate change. Well-designed investments focused on health security can strengthen public health capacities to prevent, detect and respond to infectious diseases and the international spread of disease, particularly through the implementation of and compliance with the International Health Regulations (IHR). Overall public health capacities such as these support UHC. Public health emergencies like COVID-19 draw attention to health system strengths and weaknesses and can provide opportunities to focus political attention on investment and necessary improvements [footnote 13].

Health system strengthening has been increasingly acknowledged as a common route to achieve both UHC and GHS [footnote 14]. Strengthened health systems improve the access, quality, coverage, financial protection, and sustainability required for UHC and also provide the systems and resilience needed to detect and respond to outbreaks [footnote 15]. This unifying role for health system strengthening is one that is acknowledged in commitments made by the G7, having featured at every summit since 2015 [footnote 16].

Challenges ahead include securing sustainable investment in heath system strengthening to achieve UHC that can then deliver results across priority areas, from disease control to family planning and nutrition.

The challenges also extend beyond what is necessarily captured in frameworks for health systems or health security. The G7 Elmau Summit declaration and the G7 Ise-Shima Vision for Global Health show G7 leadership on working across multiple sectors through a One Health approach, tackling challenges such as antimicrobial resistance and the impacts of climate change to improve health outcomes. Lessons from COVID-19 have highlighted that a fully integrated approach to these complex public health hazards must remain a priority at this crucial juncture for us all.

Case study: G7 support for the access to COVID-19 tools accelerator. The G7 works together in the COVID-19 response, demonstrating the importance of effective coordination in response to health emergencies and of integrating health systems strengthening into international responses.

The Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACT-Accelerator) framework was set up in response to a call by G20 leaders in March 2020 [footnote 17] and was launched by WHO and international partners in April 2020. The initiative has demonstrated the importance of effective coordination in response to health emergencies and of integrating health system strengthening into international responses. The G7 has played a significant role in its funding, leadership and development since it was established.

The ACT-Accelerator brings together governments, health organisations, scientists, businesses, civil society, and philanthropists to support the coordinated development of tools to help tackle the COVID-19 pandemic [footnote 18]. Through the advances in research and development which have been supported by the framework, the ACT-Accelerator is delivering the tests, treatments and vaccines needed worldwide to address the harm done by COVID-19 [footnote 19].

The ACT-Accelerator is comprised of four pillars: diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccines. The fourth pillar, the Health Systems Connector, works across the other three. The vaccines pillar, otherwise known as COVAX, is led by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance and WHO. COVAX aims to support the rapid development and production of safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines and to provide them to those that need them most. All participating countries, regardless of income levels, have equal access to these vaccines once they are developed. The Diagnostics pillar is co-led by FIND, the global alliance for diagnostics, and the Global Fund, with WHO involvement. It aims to rapidly identify new diagnostics and to bring 500 million affordable, high quality diagnostics by mid-2021 to populations in low- and middle-income countries. The Therapeutics pillar is led by Unitaid and the Wellcome Trust, again with WHO assistance. It aims to develop, manufacture, procure and distribute 245 million treatments within 12 months for those same populations. The Health Systems Connector is convened by the World Bank, the Global Fund and WHO, and aims to strengthen vital parts of health systems and community networks, as well as supplying personal protective equipment (PPE).

Though challenges remain, including the need to increase manufacturing capacity to secure vaccine supplies, the ACT-Accelerator has made significant progress. It has developed rapid diagnostic tests and procured more than 64 million tests for low- and middle-income countries; supported the identification of the first-life saving therapy (dexamethasone) and procured 2.9 million doses; and procured more than $500 million of PPE. In addition, more than 69 million doses of vaccine have been shipped to COVAX countries [footnote 20].

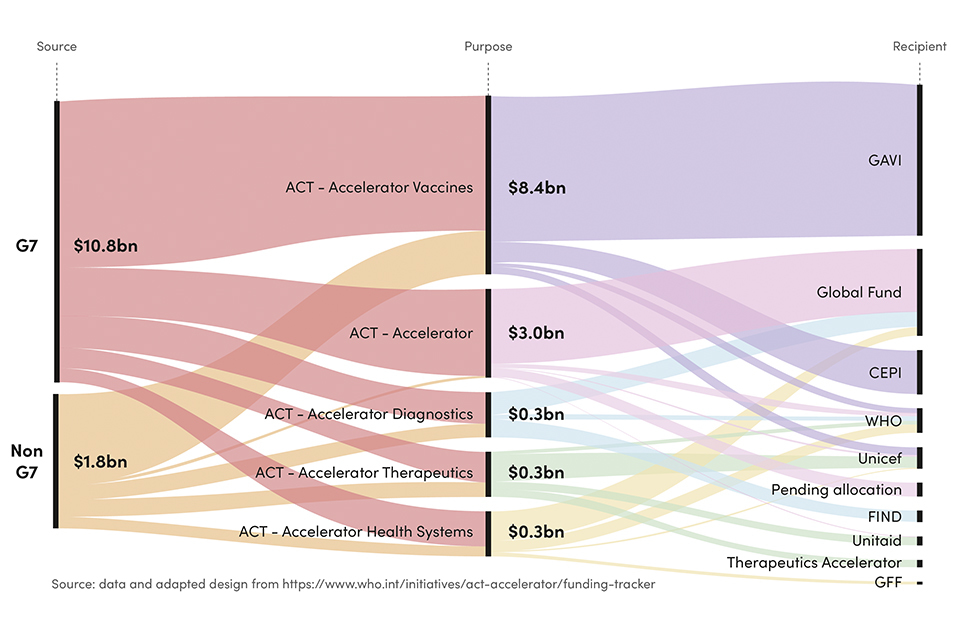

Details of the financial contributions G7 members have made so far to ACT-Accelerator are shown below in Figure 2.

Figure 2: ACT Accelerator G7 and non-G7 country commitments (footnote v)

Shows G7 and non-G7 country financial commitments to the four Act-A pillars and the international organisations that are recipients of that funding.

TDDAP supported health care workers in Chad establish Point of Entry processes and procedures. © DAI Global Health.

Conclusion

Strong health systems underpin Universal Health Coverage and Global Health Security. All three are interdependent and mutually reinforcing. Recognising this, the collaborative efforts of global actors for health, including the G7, have ensured that health systems strengthening, UHC and GHS agendas are centre stage for global policy and investment, supporting the international community to make progress towards meeting the ambitious health-related targets set by the SDGs. However, challenges remain [footnote 21]. These include ensuring close alignment of the health systems strengthening, UHC and GHS agendas, strengthening public health capacities and resilience, and addressing multi-sectoral challenges through One Health approaches to health security that also tackle issues such as antimicrobial resistance.

At their meeting in February 2021, G7 Leaders stated that recovery from COVID-19 must ‘build back better for all’ [footnote 22]. Ongoing prioritisation of health system strengthening to address infectious disease threats, including through a focus on equity, financial protection and the integration of a One Health approach, remains relevant as a way to deliver UHC and GHS [footnote 23]

Chapter 2: Attaining UHC with strong health systems and better preparedness for public health emergencies (Commitment 9)

Headline messages

-

the G7 has sustained stable investment in strengthening health systems, with an overall increase in funding through bilateral programmes since 2015, in addition to pooling investments in health systems through multilateral partners such as the World Health Organization (WHO)

-

the G7 has worked to ensure that health systems strengthening approaches have become more embedded and prioritised in the strategies and implementation of key multilateral partners and agencies such as WHO, the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, and the Global Financing Facility

-

G7 members have played a prominent role in promoting the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) agenda, supporting the UHC2030 initiative, programmes such as WHO UHC Partnership, and mobilising political commitment and solidarity for the goal of UHC. While progress is evident, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has placed previous gains at risk and has disproportionately impacted the poorest and most marginalised groups, including women and girls. UHC remains an ambitious goal to deliver by 2030

-

there has also been sustained G7 member focus on improving the health workforce in LICs and LMICs. This is visible both in policies such as ethical recruitment, and in large‑scale bilateral support to training and upstream health workforce interventions, such as revising university curriculums. Yet, while the trajectory is positive, progress remains gradual and a number of LICs have further to go to reach recommended health workforce density

The G7 has shown strong political commitment and leadership on health systems strengthening, Universal Health Coverage and preparedness for health emergencies. At Elmau (2015), Ise-Shima (2016) and at Taormina (2017) summits, G7 leaders made the following commitments:

-

we are therefore strongly committed to continuing our engagement in this field with a specific focus on strengthening health systems through bilateral programmes and multilateral structures. We are also committed to support country-led health system strengthening in collaboration with relevant partners including WHO

-

we commit to promote Universal Health Coverage (UHC) …We emphasize the need for a strengthened international framework to coordinate the efforts and expertise of all relevant stakeholders and various fora/ initiatives at the international level, including disease-specific efforts

-

we…commit to…strengthen(ing) policy making and management capacity for disease prevention and health promotion. We…commit to…building a sufficient capacity of motivated and adequately trained health workers

To measure progress against these commitments, G7 members identified targets against four indicators. This chapter summarises what G7 members have done collectively to make progress towards meeting these targets, drawing together examples of joint efforts and illustrative case studies of individual G7 member states’ support, and giving an assessment of the impact of G7’s collective efforts. This analysis complements the formal accountability reports produced every three years by the G7.

Indicator 9.1: Support to health system strengthening remains at least stable (measured by OECD-DAC CRS 121)

Health system strengthening can cover a wide range of activities. WHO’s definition of the health system uses six building blocks: health workforce; service delivery; information systems; medical products, vaccines and technologies; financing; and leadership and governance [footnote 24]. Inevitably, given the multi-faceted, complex nature of health systems, definitions of health system strengthening differ.

However, there is agreement that ‘strengthening’ involves investment that will produce a longer-term improvement in the efficiency or effectiveness of the health system. This represents a difference from ‘support’, which helps the health system continue to deliver services at an existing level of efficiency and/or effectiveness.

There is no single metric that measures health systems strengthening activities and financial contributions. Given this, Box 2 sets out the indicator that the G7 agreed to monitor progress on its commitment to strengthen health systems through funding of multilateral and bilateral programmes. While this does not capture the full extent of the G7 financial assistance for strengthening health systems, it tracks G7 financial assistance for activities that are seen as critical for the strengthening of health systems.(footnote vi)

Box 2: Indicator 9.1

Support to Health System Strengthening (HSS) remains at least stable (measured by OECD-DAC CRS 121). The baseline is 2015.

G7 action to meet this commitment

G7 members have a range of targeted health systems strengthening programmes and partnerships that support LICs and LMICs, with many health assistance programmes working in-country using a health systems approach to address priorities set by national governments through national health sector plans. Many of the G7 members’ programmes have supported the response to COVID-19 while maintaining access to essential health services. COVID-19 assistance programmes have also contained elements that aim to strengthen country health systems during COVID-19 response and recovery.

Beyond country programmes and partnerships, funding for health systems strengthening also goes through multilateral partners such as WHO, the Global Fund, Gavi, the Global Financing Facility, UN agencies, and the World Bank, or through the ACT-A initiative. G7 actions also influence the activities and priorities of other donors and partners; for example, the G20 prioritised health system strengthening at its 2017 Summit under Germany’s presidency, and Japan’s G20 presidency promoted UHC, including the agreement of the G20 Shared Understanding on the Importance of UHC Financing in Developing Countries.

Germany systematically includes health system strengthening priorities in bilateral support programmes, including focus on health workforce capacity development; rehabilitation of health facilities; supply chain management; and health financing. The EU also takes an explicit health system strengthening approach, providing funding to the six WHO building blocks of a health system, which includes a focus on health financing, sustainable health security preparedness and response, and providing effective data to support policy, planning and service delivery. The EU also plays a leading role in supporting, along with other G7 members, WHO UHC Partnership (see 9-3), which operationalises health systems strengthening in over 100 countries.

France has made health system strengthening one the four cross-cutting approaches of its global health strategy. In 2019, out of €545 million of Agence Française de Développement’s commitments in health and social protection, €327 million was recorded as contributing to health system strengthening. France also promotes health system strengthening through the French Muskoka Fund which works, through UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA and UN Women, in nine countries in West and Central Africa (Benin, Ivory Coast, Guinea, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Chad, Togo and Burkina-Faso) to promote sexual, reproductive, maternal, neonatal, child and adolescent health and nutrition (€110 million since 2010).

Among wider work addressing health system building blocks, Canada, Italy, Japan, UK and the US have programmes on strengthening sexual, reproductive, maternal, new-born, child and adolescent health services, which involves supporting and strengthening health systems. These services draw on every element of a national health system, and rely on good coordination and collaboration, each requiring different facets of the health system to come together.

A US focus on strengthening public financial management and health financing, including country reviews of resource allocation, is an important form of strengthening. It can help reform a country’s financial systems, which may be unable to absorb and process funds even when they are made available.

The UK has a range of programmes that strengthen health systems in countries. In Kenya, a comprehensive health systems strengthening approach to reduce maternal and newborn deaths reached over 1 million people between 2015 and 2018 and contributed to 72% of women giving birth in health facilities compared to 42% in 2013. In the Democratic Republic of Congo, UK support improved access to essential health services for over 9 million people.

In Ghana, UK support has aligned with the national government’s ‘Ghana Beyond Aid’ agenda to support more effective and efficient use of domestic resources, including through providing UK expertise to advise on evidence-based health priorities.

A health system strengthening approach is also important in fragile and conflict-affected states (FCAS). Canada, UK, US and the EU work together with other partners and donors to fund the Health Pooled Fund in South Sudan, which has enabled millions of children to receive preventive treatment for childhood diseases, expanded access for women to antenatal clinics, and established an effective health management information system. Italy has also supported the strengthening of the health systems in FCAS. An example of this, in Somalia, is included below, alongside a case study which illustrates Japan’s leadership on and support for health systems strengthening.

Case study: Italy. Italian contributions to health system strengthening in Somalia

While health system strengthening involves incremental adjustments to a functioning health sector in some countries, in others the system is being rebuilt almost from scratch after disaster or conflict. Italy’s €5 million of support to Somalia with ‘Restore operation and efficiency in the health sector and institutional strengthening (Novation agreement 2)’ is an example of this.

The programme is delivered in partnership with UNOPS, other UN agencies, and a procurement and project management agency. The work focuses on the rehabilitation of regional health facilities (in particular, maternal and neonatal wards), and the training of staff at these regional centres. It builds on an earlier successful Novation project which saw tertiary hospital rehabilitation in the Somali capital, Mogadishu, as well as the semi- independent territories of Somaliland and Puntland. The longer-term objective is to support achievement of UHC in Somalia.

Italy also supports concessional loans for improved infrastructure and quality of service delivery in other countries, such as Uganda (a €10 million project in remote areas in Karamoja), Ethiopia (€10 million for a transformation multi-donor fund managed by the Ministry of Health), in Guinea (with €20 million to strengthen the national Health system) and in Palestine (€10 million to build two new hospitals in Dura and in Halul).

Case study: Japan. Japan strengthens health systems through a focus on training, quality and improving management of hospitals

The G7’s 2016 Ise-Shima Vision for Global Health, led by Japan, made specific reference to “the pressing need for strong, resilient and sustainable health systems in Low Income Countries and Lower Middle Income Countries with limited resource and increased vulnerability”. Japan further raised global awareness of the need for health system strengthening through the adoption of the Tokyo Declaration at the UHC Forum in 2017. Japan also convened the UN Ministerial Meeting of the Group of Friends of UHC in 2020, which other G7 members also joined. In addition, Japan has provided support to a range of health system strengthening-focused programmes across Asia (e.g. Thailand, Laos and Fiji) and Africa (e.g. Egypt, Malawi, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe).

Some of this work has focused on how to raise the standard of hospital management, to improve both care quality and its effectiveness (e.g. care volumes). In many countries, health care management training is less widely established than clinical training.

In Laos, a continuous quality management system in hospitals was instituted in four southern provinces, which led to better treatment of outpatients, and improved service in relation to eclampsia and post-partum haemorrhage. Maternal care is globally a key equality issue, with large differences in outcomes between socioeconomic groups.

In Fiji and in African countries, Japan has been able to show how techniques originally developed in manufacturing such as 5S, Kaizen, and Total Quality Management can significantly raise quality within health systems, especially in hospitals.

In Thailand, health managers were trained, focusing on how to increase the financial sustainability of the national health system, including through reimbursement policies. All of these programmes are linked explicitly to the development of UHC (see Indicator 9.3), and also involve targeted improvements in the work environment for staff which can improve the health workforce, increasing motivation and reducing attrition. All represent ways to achieve more and higher standards of care from the same health system assets.

Latest evidence

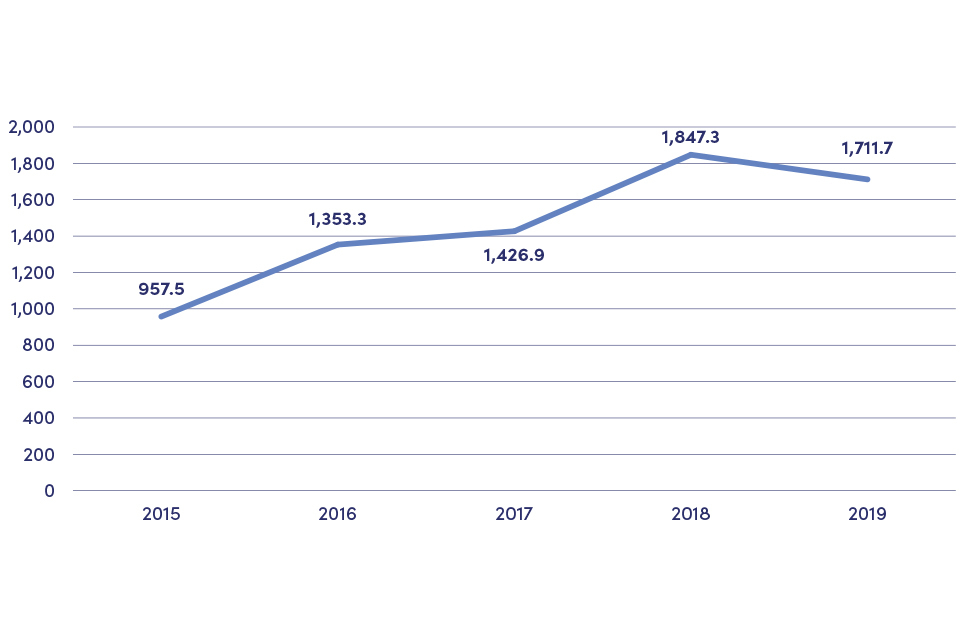

As Figure 3 shows, [footnote 25] G7 members’ disbursed funding for health systems strengthening has been broadly stable, around a rising trend between 2015 and 2019.

G7 disbursed funding peaked in 2018 at $1,847 million. While it declined slightly to $1,711 million in 2019, it remained significantly higher than the $957 million disbursed in 2015. This follows a similar trajectory to contributions by all donors, which rose from $2,489 million to $3,640 million over the 2015-2019 period. Figures for allocations in 2020/2021 are yet to be published and are not part of this report.

The share of G7 members’ contributions among all donor funding of health system strengthening as measured by OECD-DAC rose from 38% (footnote vii) in 2015 to 47% in 2019.

Figure 3: G7 disbursements on General Health (OECD CRS 121, 2015-19, constant $m)

Shows that G7 members’ disbursed funding for health systems strengthening has been broadly stable around a rising trend between 2015 and 2019.

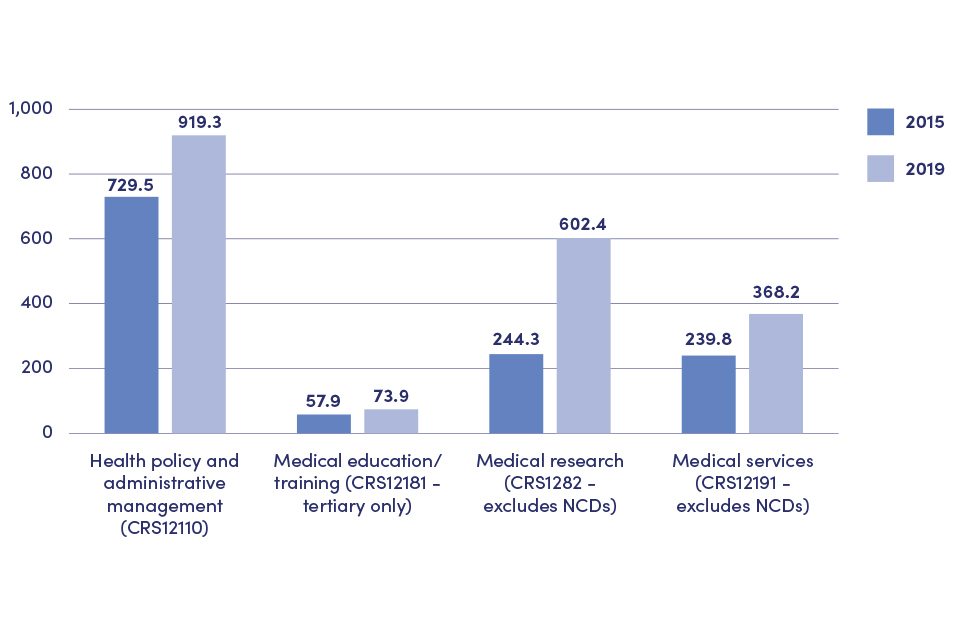

The following Figure shows that this increase in health systems strengthening funding is broad-based, with funding by all donors having risen over the period in each of the four categories within the OECD measure that is used as an indicator for health system strengthening funding by the G7.

Figure 4: Components of the OECD CRS 121 Category, all donors ($m)

Shows the increase in G7 funding for health systems strengthening is broad based with funding increasing in each of the 4 categories within the OECD measure used.

Indicator 9.2: Enhanced positioning of health system strengthening in strategies and operations of GFATM, Gavi, WHO and other multilateral organisations through G7 members

A strong health system can only be achieved if all partners in the health sector combine their efforts and investments towards a common goal. In particular, there are significant opportunities to use investments through multilateral partners such as the Global Fund and Gavi to fulfil their individual disease mandates and also strengthen national health systems, ensure greater sustainability and efficiencies, and improve broader health outcomes. All G7 members have close links with different multilaterals – as donors, board members or technical advisers – and agreed to focus on working together to enhance a health system strengthening approach in partnership with multilateral initiatives and partners.

To track this action, G7 members agreed to monitoring progress against the indicator outlined in Box 3.

Box 3: Indicator 9.2

Enhanced positioning of HSS in strategies and operations of GFATM, Gavi, WHO and other multilateral organisations through G7 members (measured by self-reporting, e.g. based on board meeting protocols). The baseline is 2016.

G7 action to meet this commitment

G7 members are the leading funders of many of these organisations, and have regularly used their influence to advance the health system strengthening agenda, often acting together and with other donors. This includes through the hosting of replenishment events. France hosted the Global Fund replenishment in 2019 and the UK hosted the Global Vaccines Summit in 2020 to support Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, raising unprecedented pledges of support – $14.02 billion for Global Fund over three years, and $8.8 billion for Gavi over five years – in a show of global solidarity.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has a particularly important mandate on health systems strengthening internationally. G7 engagement with WHO, its governing body the World Health Assembly, and voluntary contributions to WHO continue to support key priorities set through its General Programme of Work, including health systems strengthening and UHC, health emergencies, promoting wider health and well-being, and organisational reform. More detail on G7 support to the WHO’s UHC Partnership programme is provided in discussion on G7 support for advocacy on and mobilisation of the UHC agenda (see 9.3 below).

Germany and France, in collaboration with Japan and the UK, have played key roles in developing the position within the Global Fund’s agenda of Resilient and Sustainable Health Systems (the Global Fund’s term for health system strengthening). G7 members have promoted an integrated people-centred approach to UHC through systems strengthening investments across the three diseases that the Global Fund focuses on: HIV, tuberculosis and malaria. France, Germany and the UK all have complementary funds that specifically aim to strengthen the Global Fund’s role in strengthening health systems for UHC and contributing to health security. Examples of how these are used are outlined in the case studies in this section.

Similarly, strengthening the prominence of health system strengthening within Gavi has drawn on collaboration across G7 members and other partners. G7 members have engaged in the operational design of Gavi’s new Health System and Immunisation Strengthening (HSIS) Support Framework, advocating for UHC and HSIS to guide future work on immunisation and equity through Gavi’s zero-dose agenda to reach the millions of children still not receiving routine vaccines in Gavi-supported countries. G7 members have also supported the agreement of $500 million uplift in country support and resources to health systems strengthening in Gavi’s new strategic period, including ensuring that Gavi’s strategic goal on strengthening health systems has timely and measurable metrics at the country level to monitor performance and delivery.

Health systems strengthening is a key part of the approach of other multilateral agencies and partners. G7 members have worked with the Global Financing Facility as donors and partners to support the development of its 2021-2025 strategy. This has a focus on the development and implementation of government-led, prioritised and costed national investment cases that lay out the pathways to scaling up universal access to a basic package of reproductive, maternal, newborn, child and adolescent health and nutrition services along with critical health financing and system reforms to accelerate progress toward UHC. G7 partners also support the strategy development of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative, which plays a key role on health systems pillars such as strengthening supply chains, improving the technical capacity of health workers, and providing critical infrastructure that deliver not only polio vaccination but support surveillance systems, laboratory networks, and the provision of other health services to communities – all of which are important for overall health security.

The 2019 Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All, which brings together multilateral agencies to better support countries to accelerate progress towards the health- related SDGs, was developed in response to a proposal from Germany, Norway and Ghana. Other G7 members have provided inputs both through public consultations and participation in working groups on specific pillars of the Global Action Plan. Since 2016, G7 members have also helped shape health systems priorities and action through participation in the UHC2030 partnership (see below).

Case study: France. France actively promotes the health system strengthening agenda as one of the four cross-cutting approaches of its Global Health strategy

Case study for Commitment 9: Pape Adama is going to the Bignona health center (Casamance, Senegal) for a physiotherapy session, funded through the ACCESS project, implemented with the support of L’Initiative. L’Initiative supports beneficiary countries in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of funding allocated by the Global Fund à credit : © Anna Surinyach/Expertise France

In 2011, France created L’Initiative. The overall objective of this initiative is to help to build more effective responses to pandemics and to strengthen the capacity of civil society structures, national programmes and regional organisations. L’Initiative supports beneficiary countries in the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of funding allocated by the Global Fund. Since its inception, L’Initiative has established itself as a key player in the fight against pandemics with 522 technical missions (€41 million), 109 intervention projects (€93 million) and 6 operational research projects (€5 million) between 2011 and 2019. As an indirect French contribution to the Global Fund, L’Initiative is entrusted each year with a proportion of France’s contribution to the Global Fund, i.e. an average of €25 million per year from 2017-2019. For the 2020-2022 period, L’Initiative is stepping up its efforts: following the 6th Replenishment Conference of the Global Fund in Lyon in October 2019, the L’Initiative’s overall budget has increased to nearly €39 million annually and its allocation has risen to 9% of France’s contribution to the Global Fund. Its interventions – technical missions, resident expertise and extended duration funding – are implemented by Expertise France and are now focused on the health system challenges of 40 eligible countries.

France contributed to the creation of Unitaid, an organisation that seeks to enable equitable access to affordable diagnostics and treatments for HIV, malaria, tuberculosis and their co-infections as well as for child and maternal health, for low- and middle- income countries. During the last five years, France has helped Unitaid to develop a more comprehensive approach to strengthen health systems. France also renewed its financial contribution to Unitaid with €255 million for the 2020 to 2022 period.

At a bilateral level, the French Development Agency (AFD) is implementing significant projects aiming at supporting partner countries to strengthen their health systems and expand health coverage systems. For instance, since 2009 AFD has been implementing a €57.7 million project in Cameroon with KfW, a German government-owned development bank, aimed at improving health in the most vulnerable population (pregnant women and children) through supporting the decentralisation of the health system and strengthening the provision of health care (total AFD contribution to the project is €35.5 million).

In Mauritania, since 2008, the AFD has been supporting the development of an obstetric care package to ensure better supervision of pregnancies and birth, and initiated in 2019 a four-year €8 million project to provide immediate support to strengthen access to health care in fragile areas (Gorgol, Assaba, Guidimakha, Hodh El Gharbi, and Hodh Ech Chargui) and health system strengthening at national level to improve primary health care and maternal and child health. In 2019, AFD commitments in health and social protection amounted to a total of €545 million; €370 million were dedicated to health, including €327 million to health system strengthening.

As part of its response to the COVID-19 crisis, France provided a supplementary contribution of €50 million in 2020/2021 to support WHO’s efforts in health system strengthening and resilience.

Drawing on digital technology, French support has helped launch the WHO Academy in 2021, to offer personalised and multilingual online lifelong learning which is open to all health sector stakeholders. It is planned that this will reach 10 million people around the world by 2023.

Nurse Hedda and the triage team at Connaught Hospital, Freetown, Sierra Leone. © Simon Davis/DFID

Case study: Germany. Germany works with multilaterals to strengthen health systems

Working closely with partner G7 member states, Germany has helped make health system strengthening a priority topic at the board and committee level of several leading multilateral organisations. In doing so, it has been able to draw on decades of experience in regional and bilateral health system strengthening work, including as one of the funders of the BACKUP Health programme.

In the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (The Global Fund), Germany worked with France, the UK and Japan to position health system strengthening as a central part in the 2017 to 2022 strategy. This involved calling for a stronger health system strengthening focus at the March 2015’s board meeting, leading to Resilient and Sustainable Systems for Health (RSSH) becoming one of the four standalone objectives in the Strategy Framework that was approved later that year. Further German interventions ensured this translated into an increase for RSSH in the 2017 to 2019 and 2020 to 2022 funding allocations. The Global Fund’s RSSH team has also benefitted from staff secondments from Germany since 2018. In collaboration with other G7 partners, an RSSH Roadmap was developed in 2019 to strengthen the quality and impact of RSSH interventions. In the development of the next Global Fund strategy beyond 2022, Germany continues to promote RSSH as a priority topic.

Germany has worked with partners to play a similar role at Gavi, making health system strengthening a central component of programmatic sustainability efforts. Here, Germany has been able to use its vote on the Gavi Board, which is shared jointly with France, the EU, Luxembourg and Ireland. As a result, Gavi’s 5.0 Strategy (2021 to 2025) incorporates an enhanced HSS approach differentiated between short-term support and explicit longer-term strengthening, something that can be unclear in some health system strengthening work. Further advocacy helped ensure that Gavi’s health system strengthening funding to its partner countries for the Gavi 5.0 period also rose by $500 million to $1.7 billion in 2020.

Germany supports the World Health Organization (WHO) in strengthening health systems at various levels and significantly increased its contributions to the organisation in 2020. Jointly with Ghana and Norway, Germany asked WHO to guide the development of a Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All (GAP), which was launched in September 2019. Germany contributes to the global infrastructure in, for example, the Global Outbreak and Alert Network (GOARN), the Tripartite (FAO, WHO, OIE), the Digital Health Division and the GAP. In addition, it provides financial support to WHO regional offices and advises on projects in, for example, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and East African Community (EAC) regions.

Latest evidence

There is good evidence that many of the development partners supported by the G7 have shifted their policies and how they work to take on a stronger and more effective health systems approach, in part as a result of G7 actions.

Evidence of progress is visible through the efforts of many of the global health partners to embed health systems strengthening approaches, whether through revisions of strategies, general work plans or in the ongoing commitment to joint partnerships that progress the health system strengthening agenda. These include:

-

Within WHO, a strong health system strengthening approach is visible through:

- the prominence of health system strengthening as a key strategy within the three pillars of WHO’s General Programme of Work (2019 to 2022) and the appointment of an Assistant Director-General for Universal Health Coverage and Healthier Populations [footnote 26]

- the continued focus, including the use of the latest evidence from the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research unit, in operationalising the health systems ‘building block’ framework. For instance, strengthening health systems has been incorporated in the COVID-19 pandemic operational guidance [footnote 27] and the Primary Health Care operational framework [footnote 28]

- the prominent position of health system strengthening within WHO and partner initiatives, including the UHC Partnership, UHC2030, and the Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All. The UHC Partnership is one of the main vehicles within WHO for operationalising health system strengthening support. This is discussed in more detail under Indicator 9.3

-

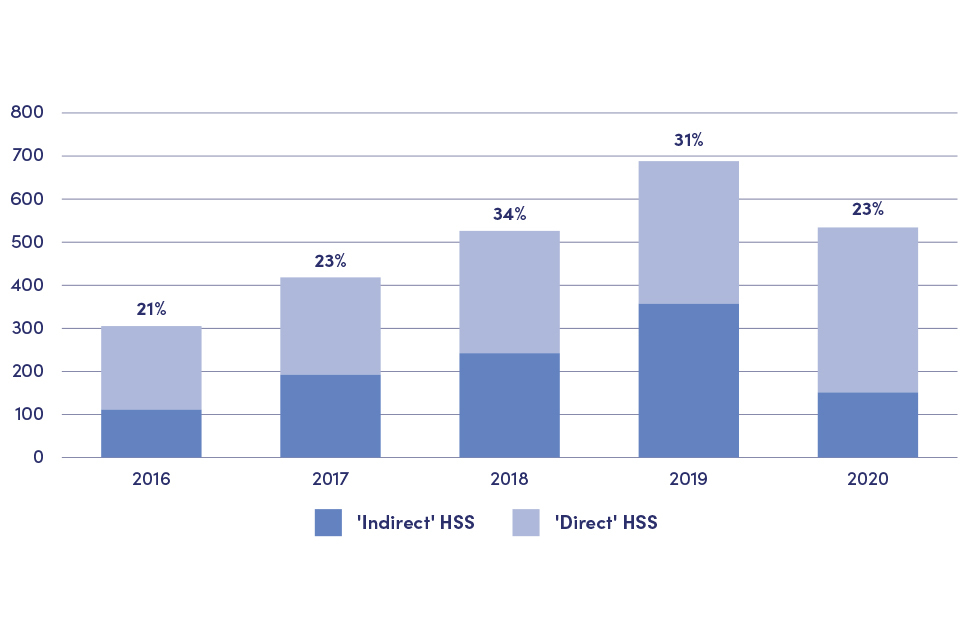

Gavi’s health system and immunisation strengthening framework (HSIS) was launched in 2016. This continued a trajectory that began with making health system strengthening funding available in 2006, while the 2021-2025 strategy further strengthens this commitment, with health system strengthening as its second pillar. Gavi’s Board agreed eight health system strengthening indicators for the new Strategy at its December 2020 meeting. As Figure 5 below shows, Gavi’s health system strengthening funding has grown from $305 million (footnote viii) (equivalent to 21% of total spend) in 2016, peaking at $688 million in 2019 (31%), before reducing to $534 million (23%) in 2020, reflecting the demands of the COVID-19 pandemic. During this period, G7 members’ contributions as a share of Gavi’s total budget have remained relatively constant at between 50% and 60%.

Sakina, 24, marks the finger of a child with indelible ink as a sign that he has been vaccinated during a national immunisation campaign supported by UK aid. © WHO Afghanistan/R.Akbar

Figure 5: GAVI, health system strengthening (HSS) spend, $m (and % of total Gavi spending) (footnote ix)

Shows that Gavi’s health system strengthening funding has grown from $305 million in 2016, peaking at $688 million in 2019, before reducing to $534 million in 2020.

-

The Global Fund’s 2017 to 2022 Strategy also has Resilient and Sustainable Health Systems (RSSH) as one of its four pillars. While its next strategy is still evolving, the Global Fund Board has expressed its expectation to constantly improve impact and quality of RSSH interventions to ensure sustainable outcomes on the three diseases on several occasions [footnote 29], [footnote 30]. The Global Fund’s health system strengthening funding is substantial though it has not expanded over this period: it stood at $2.97 billion in 2017 to 2019 (26% of the total) compared to $3.72 billion in 2015 to 2016 (29%).(footnote x) However, thanks to the successful replenishment hosted by France in 2019 (including increased G7 contributions), the Global Fund is planning to increase its annual RSSH interventions from $1 billion to $4 billion, as set out in the 2021 to 2023 investment case [footnote 31].

-

The World Bank’s Global Financing Facility (GFF) [footnote 32] was created in 2015, and has had a strong focus on strengthening health systems to support women, children and adolescents from the start. Over the last few years and in its 2021 to 2025 strategy, the GFF has made its health system strengthening approach clearer, including defining their support to build more resilient, equitable and sustainable health financing systems, working with the private sector, and supporting governments to ramp up provision of a broad scope of quality, affordable primary health care services critical for improving the health and nutrition of women, children and adolescents [footnote 33].

-

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) [footnote 34] also strengthens systems where needed to achieve its disease objective. GPEI’s most recent Polio Endgame Strategy (2019 to 2023) includes an explicit goal on integration, setting out GPEI’s role in contributing to strengthening immunisation and health systems to help achieve and sustain polio eradication, and ensuring that poliovirus surveillance is integrated with wider surveillance systems for other vaccine-preventable and communicable diseases [footnote 35].

-

Other UN bodies and agencies are also demonstrating a shift towards health system strengthening approaches. UNICEF’s Strategy for Health (2016 to 2030) [footnote 36] includes the aim to shift from vertical disease programmes to strengthening health systems and building resilience; UNDP’s HIV, Health and Development Strategy Note (2016 to 2021) [footnote 37] includes action areas to promote effective and inclusive governance and build resilient and sustainable systems for health; and Unitaid‘s 2017-2021 strategy [footnote 38] includes an investment commitment to invest in products which improve health systems, including through products that allow for decentralisation, that tackle more than one disease, and that put the person rather than the disease at the centre of care.

-

The Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator (ACTA-A), launched to combat the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, has health system strengthening as one of its four pillars (the Health Systems Connector, that works across the other three pillars), recognising that capacities and infrastructure need scaling up so that vaccines, diagnostics and therapeutics can be effectively delivered [footnote 39]. A key focus has been on harmonising data efforts, focusing on community and private sector engagement, and identifying key health financing bottlenecks.

The Global Action Plan for Healthy Lives and Well-being for All (GAP) [footnote 40] was launched at the UN General Assembly in 2019. It was developed in response to a request from the heads of government of Germany, Ghana and Norway – and later the UN Secretary-General – requesting that the Director-General of WHO and heads of other multilateral agencies streamline their collaboration and efforts. The GAP unites 13 organisations around focusing on the health-related SDGs, which explicitly involve health system strengthening in their attainment. These are: Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance; the Global Financing Facility for Women, Children and Adolescents (GFF); the International Labour Organization (ILO); The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (The Global Fund); the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); United Nations Development Programme (UNDP); United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); Unitaid; United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women); the World Bank Group; World Food Programme (WFP) and the World Health Organization (WHO). Under the Global Action Plan, the agencies are better aligning their ways of working to reduce inefficiencies and provide more streamlined support to countries.

Indicator 9.3: G7 financial and technical contributions for the establishment and strengthening of the International Health Partnership for UHC 2030 (UHC2030) and G7 engagement in UHC2030 activities

In 2015 there was a shift from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) set in 2000 to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that broadened the focus from specific health issues such as child mortality and HIV/AIDS to a more expansive ambition to ‘achieve good health and well-being for all at all ages’, with a target date of 2030.

This is epitomised in SDG 3 by target (3.8) to “achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all”.

UHC’s goal is to ensure equality of access, meaning that all people may benefit from a full range of quality health services, including prevention, promotion, treatment, rehabilitation and palliation, without risk of financial hardship. UHC can only be built upon the foundation of a well-functioning health system and so health system strengthening approaches are critical to the ambition of UHC.

Reflecting the spirit of partnership and solidarity promoted by the SDGs, the G7 agreed to track contributions to and engagement with the agenda to achieve UHC by 2030. The indicator for this commitment focuses on G7 support for UHC2030, which is a coordination and advocacy platform hosted by WHO and the World Bank (with the OECD expected to join as co-hosts) to advance the UHC agenda, evolving from the Millennium Development Goal- oriented International Health Partnership (IHP+). Reflecting the G7’s commitment to promote UHC, this section will also consider other activities by G7 members to advance efforts to advance UHC beyond support for UHC2030.

To track this action, G7 members agreed to monitoring progress against the indicator outlined in Box 4.

Box 4: Indicator 9.3

G7 financial and technical contributions for the establishment and strengthening of the International Health Partnership for UHC2030 (UHC2030) and G7 engagement in UHC2030 activities (measured by collective assessment based on the progress of UHC 2030). The baseline is 2016.

G7 action to meet this commitment

G7 members have assisted UHC2030 in several ways: direct investments to the UHC2030 secretariat through WHO; secondments; supporting the various networks that provide some of the technical expertise, such as the Social Health Protection Network (P4H) and the Health Data Collaborative; and through providing direct technical advice to the secretariat.

The EU has been a key funder of IHP+ and UHC2030 from the beginning, and Japan has made an annual contribution since 2017. Germany provides technical support and made a specific contribution to UHC2030 to assist with the UN High Level Meeting of 2019, while France is supporting the UHC2030 coalition financially (€4 million in 2020 to 2021) and the P4H network (€6 million in 2020 2021), which France helped create in 2007. France also currently sits on the UHC2030 Steering Committee as president of the high income country constituency.

Other G7 members have been active in UHC2030 technical working groups, and active in related health system strengthening initiatives such as the Health Data Collaborative, in which the UK is a donor representative, and through additional funding of the P4H network.

Beyond UHC2030, G7 members have also helped embed UHC in the global health policy agenda – for example, Japan supports the Partnership Program for UHC with the World Bank and the UK has worked with partners to strengthen the links between efforts to promote and advance UHC and those to address other challenges such as antimicrobial resistance. Japan also ensured a health system strengthening focus in the Declaration of the UHC Forum, held in Tokyo in 2017. All G7 members endorsed the UN General Assembly’s adoption of the political declaration on UHC at the UN High Level Meeting in 2019 [footnote 41].

The UHC Partnership, hosted by WHO, is funded mainly by G7 members (footnote xi) as Figure 6 shows.

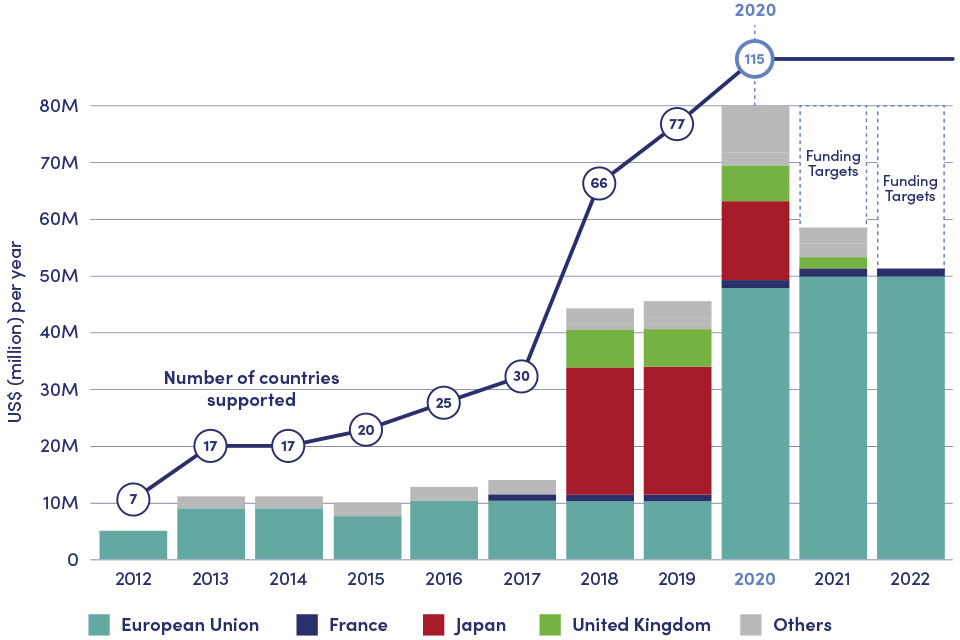

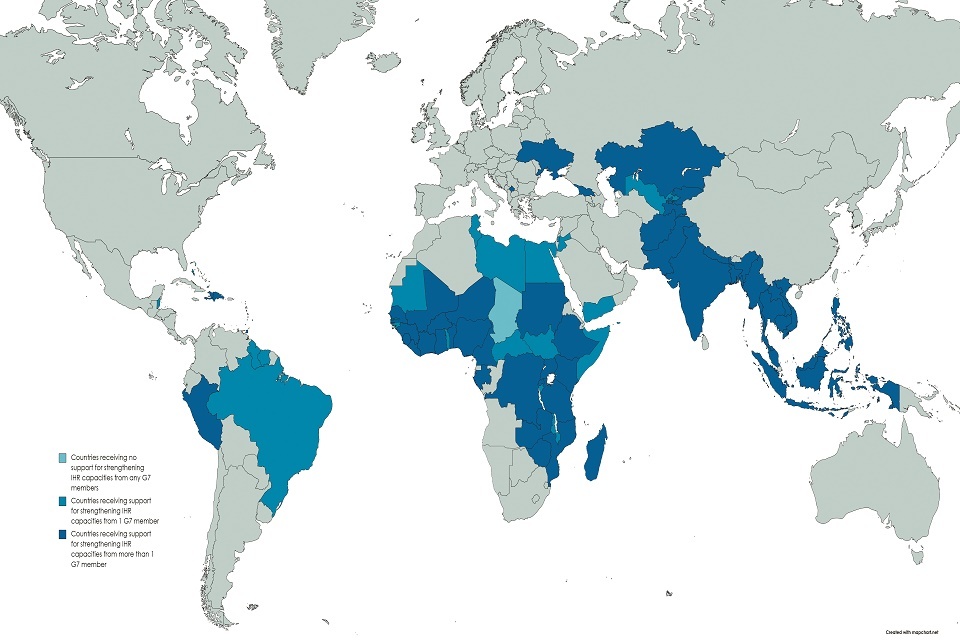

A proportion of the EU’s funding for the UHC Partnership supports UHC2030 activities, as set out in the EU’s case study below. The UHC Partnership promotes UHC by fostering policy dialogue on strategic planning and health systems governance, developing health financing strategies and supporting their implementation, and enabling effective development cooperation in countries. The G7’s support to the UHC Partnership has been part of its significant growth since it was established and it now supports health system strengthening activities in 115 countries.

Figure 6: Funding of the UHC Partners

Shows funding to the UHC Partnership from 2012 to 2020 has risen from $10 million to $80 million, and has mainly come from G7 countries.

Source: Approximate data, courtesy of the UHC Partnership.

Case study: Canada. Canada supports UHC through advancing equitable access to health services

Canada has maintained a focus on advancing gender equality, the empowerment of women and girls and addressing the needs of vulnerable communities and fragile states within the global move towards UHC. This is in harmony with the UHC2030 Global Compact which upholds equitable access, a rights-based approach, national leadership, and citizens’ engagement in health systems processes and decision-making, and to which Canada is a signatory.

This focus has been visible in significant investments made by Canada in health system strengthening and in promoting the health and rights of women, children and adolescents, as a contribution to UHC in a wide range of countries. Health system strengthening in support of UHC was a pillar of Canada’s flagship commitments to Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH) for over a decade, with total funding of $6.5 billion. Commitments included strengthening health systems, reducing the burden of disease, improving nutrition, and ensuring accountability for results. This followed from Canada’s earlier leadership on the Muskoka Initiative for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, launched at the G8 Summit in 2010.

Canada is now building on that legacy with a 10-year commitment to health and rights (2020 to 2030), with funding to reach $1.4 billion annually in 2023.

Another important equity-oriented avenue for Canadian UHC investments has been primary health care, now recognised as the most important channel for care if UHC objectives are to be met. Canada provides $60 million to the Mozambique Primary Health Care Strengthening Program, implemented through the World Bank in collaboration with the Global Financing Facility in Support of the Every Woman, Every Child initiative. The project seeks to advance the UHC agenda by strengthening the Mozambican health system and increasing coverage, access and quality of primary health care services, including sexual and reproductive health services, with a focus on underserved districts. Amongst others, the project aims to support the development of a sustainable human resources approach by developing the national community health workers’ programme and the deployment of trained health care workers in health facilities. Furthermore, it has supported an innovative approach by providing sexual and reproductive services in schools to adolescent girls and boys. In response to the public health emergency caused by COVID-19, the project has contributed to enable treatment centres to have increased human resources to respond to the crisis.

Canada is a significant contributor to the UHC activities on the part of WHO, the GFF and Stop TB. Following other G7 members, Canada is utilising the UHC Partnership to strengthen primary health care systems for COVID-19 response and resilience.

Case study: EU. The EU provides significant support to the UHC Partnership

The Children’s Hospital in Lao PDR provides a full range of services from primary care to family doctor consultations. It also offers child-friendly dental services. ©WHO/Ben Duncan

The EU initiated and played a leading role in the support of WHO’s health systems strengthening and UHC efforts, contributing €198 million to the UHC Partnership since its inception in 2011. The UHC Partnership’s activities includes funding for 120 technical advisers, now deployed across 115 countries, a significant increase from the seven countries supported in its first year. These advisers lead and coordinate policy dialogue between national governments and their development partners, focused on addressing issues across the six health system ‘building blocks’ where improvement is needed on the path to achieving UHC.

Particular attention is currently given to addressing non-communicable diseases, health security and primary health care. Since 2020, there has also been a focus on leveraging sustainable health, security preparedness and response to address the COVID-19 pandemic for UHC purposes. Many WHO country staff have been temporarily reassigned to focus on COVID-19 related activities during this time, demonstrating the flexibility of the UHC Partnership.

A logical framework provides specific indicators for the UHC Partnership’s objectives and specific results. Progress is monitored partly at the global level through a Multi-Donor Coordination Committee that meets bi-annually. On a quarterly basis, there is a review of 4-5 countries in each WHO region using a ‘live monitoring’ tool. The tool works to identify best practices and challenges – so that all countries can learn from each other in their move towards UHC. At country level, bilateral EU health delegations also assist in the monitoring of the UHC Partnership’s work, where there is an expectation that WHO advisers should remain additional and not substitute the Ministry of Health’s functions.

Latest evidence

UHC2030 has been established and has succeeded in bringing together different stakeholders in support of the UHC agenda. The paper ‘Healthy systems for universal health coverage – a joint vision for healthy lives’, co-initiated by Germany and Japan and facilitated by the EU, creates a common understanding of health system strengthening for UHC and defines principles and policy goals. It outlines key aims such as ensuring that UHC efforts “are appropriately informed by country needs” [footnote 42]. In the COVID-19 context, this has been reinforced by UHC2030’s paper on health emergencies and UHC [footnote 43].

UHC2030 has convened and ensured input from a wide range of constituencies including high income countries; multilateral organisations; foundations; LIC/LMICs; civil society; the private sector; and academia. This resulted in a critical set of ‘Key Asks from the UHC Movement’ [footnote 44] that influenced the UN High Level Meeting on UHC in 2019. UHC2030 uses the key asks and related commitments in the UHC Political Declaration [footnote 45] to steer ongoing efforts [footnote 46] to translate political commitment into collective action for UHC. UHC2030’s work on accountability for UHC commitments includes a flagship review in 2020 of the state of commitment to UHC that tracks progress from diverse stakeholders’ perspectives, contributing to broader lessons learnt as countries and the international community seek to advance the UHC agenda [footnote 47]. UHC2030 also supports the links between health system networks and related initiatives such as the Health Data Collaborative, the P4H network working on financing for UHC and social health protection, and the Global Health Workforce Network [footnote 48].

Beyond the advocacy and stakeholder engagement provided by UHC2030, there are mechanisms and programmes supported by the G7 that deliver direct operational support to countries. The WHO UHC Partnership, employing an annual budget of $80 million, provides support that is intentionally catalytic, helping countries access additional funding from elsewhere to move forward with UHC plans. The focus of WHO and other stakeholders is increasingly on primary health care as an effective vehicle to deliver UHC rapidly and equitably to most of the population.

Progress on the UHC agenda is monitored through UHC monitoring reports produced by WHO and the World Bank. The latest report in 2019 provided evidence of some progress towards UHC. Access to essential care has been expanding. A country level service coverage index has risen from a global average of 45 (out of 100) in 2000 to 66 in 2017, with gains across all regions and income groups [footnote 49].