Evaluation of the Volunteering Futures Fund

Published 18 September 2025

Applies to England

Evaluation of the Volunteering Futures Fund

Key terms and definitions

The table below describes how key terms have been used throughout the report

Key terms and definitions

| Term | Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Arts Council England (ACE) | Delivery partner for the VFF, responsible for delivering the majority of the fund for arts, culture, heritage, civil society, youth and sport initiatives involving volunteers. The fund was split across 19 projects running until March 2024. | |

| Beneficiaries | People and organisations who benefitted from the VFF programme. This includes the volunteers, organisations delivering projects and their staff members, and the service users of the projects. | |

| Common Minimum Dataset (CMD) | The minimum set of variables that all VFF funded projects had to collect data on through the data form which is then aggregated to report programme level data. | |

| Contribution analysis | A theory-based evaluation method used to assess impact through revising theories about how particular outcomes arose, with evidence collected used to either confirm or discount any alternative explanations. | |

| Data form | A form produced for the evaluation which outlined key areas which all VFF funded projects had to report data against. | |

| Delivery partners | There were three delivery partners in this programme: Arts Council England (ACE), Pears Foundation and NHS Charities Together (NHSCT). They were responsible for choosing the grantees, distributing the funds, and monitoring grantees. | |

| Digital volunteering | Volunteering which takes place digitally, either remotely or in person. | |

| Flexible volunteering | Volunteering where volunteer services offered have no regular pattern of commitment or a minimum stipulated number of hours. | |

| Formal volunteering | Giving unpaid help to groups or clubs, for example, leading a group, providing administrative support or befriending or mentoring people. | |

| Grantees | The collective term for organisations receiving a grant under the VFF programme to deliver a project. | |

| Match funding | Funds paid in proportion to funding being paid from other sources (e.g. fundraising through donations). | |

| Micro volunteering | Volunteering to do specific time-bound tasks that can be undertaken as one-off (e.g. collecting or delivering groceries, doing an errand, making telephone calls, or giving someone a lift). | |

| NHS Charities Together (NHSCT) | Delivery partner for the VFF, focused on funding health and social care related projects. The fund was split across 14 projects running until March 2023. | |

| Partners | Organisations working alongside the lead grantee to deliver the project or an element of a project. | |

| Pears Foundation | Delivery partner for the VFF, focussed on funding projects supporting children and young people, or disabled people. The fund was split across six projects running until March 2023. | |

| Programme | Refers to the Volunteering Futures Fund (VFF) programme. | |

| Regular volunteering | Volunteering where volunteer services are offered on a regular pattern of commitment (that is, each week at the same time). | |

| Volunteer retention | The ability for organisations involved to retain their volunteers for the expected period of volunteering. |

Key findings and recommendations

Key findings from the evaluation

-

The Volunteering Futures Fund (VFF) is a £7.4 million fund which aimed to support high quality volunteering opportunities for young people and those who experience barriers to volunteering, encourage innovation in volunteering practices and learn about the effectiveness of different volunteering models. It was launched in 2021 by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). At the time of the evaluation concluding in October 2023, across the three delivery partners, VFF funded projects had recruited 15,136 volunteers. Of these volunteers recruited, 43% were first-time volunteers.

-

The impact evaluation found that the funding package achieved its stated aims and objectives. It found strong evidence that the VFF supported volunteers from diverse backgrounds to engage in volunteering, and of subsequent impacts on these volunteers (such as increased confidence, wellbeing, and connection to local communities). It also found moderate evidence that organisations improved routes into regular volunteering and increased the number of volunteering opportunities available, and that funding led to improved services. However, at the time of the evaluation concluding in October 2023 (prior to completion of projects in March 2024), it had only found weak evidence to conclude that the funding increased learning about and understanding of new models of volunteering and what works well/less well for improving volunteer recruitment and diversity.

-

The VFF helped to improve services and collaboration across the voluntary sector. Data from grantee interviews shows that the VFF helped promote partnership working, which enabled the tailoring and personalisation of volunteering opportunities for target groups.

-

Although delivery partners felt that the overall fund objectives were broad enough to allow for a wide range of projects to be funded, time constraints both for applications and delivery limited the diversity of projects funded, with delivery partners making more a risk-averse selection of potentially less innovative projects.

-

The match-funding element of the VFF was particularly beneficial and was a facilitator for the success of projects. The funding gave grantees more flexibility with project delivery, allowing adaptations and opportunities for innovation and learning within projects.

-

Requirements for spending grants were challenging. NHS Charities Together (NHSCT) and Pears Foundation projects had to spend the DCMS portion of the grant in the Fund’s first financial year. This affected the way projects were chosen, as delivery partners chose projects that were capital-intensive and involved large investments in infrastructure early on.

-

Many grantees co-designed their projects with volunteers, which helped them design appealing activities. Pre-project outreach with schools and colleges was also important for expediting the recruitment of young and disabled volunteers.

Recommendations for future fund design and delivery

-

Increase timelines for delivery (and flexibility with grant spending within the delivery window) to allow for innovation within projects and sufficient time to build trust with new groups of volunteers.

-

Lengthen the application process to allow grantees to collaborate on applications with multiple partners.

-

Ensure that project timelines allow sufficient time to recruit new volunteer groups.

-

Ensure a range of volunteering modalities are offered across (and within) funded projects.

-

Offer volunteers greater ownership and agency in volunteering activities (e.g. through co-production).

Executive summary

Overview of the research

This report presents findings from an evaluation of the Volunteering Futures Fund (VFF) – a £7.4 million UK Government fund designed to support a range of volunteering opportunities for young people and those experiencing barriers to volunteering. The Fund aimed to support high quality volunteering opportunities and increase volunteer recruitment and retention, support long term diversification of volunteers in the voluntary sector, encourage innovation in volunteering practices and support the sector to learn about the effectiveness of different volunteering models (such as micro, flexible and digital volunteering). The Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) launched the Fund in 2021 with two strands of funded volunteering activities: (i) arts, culture, heritage, sport, civil society, and youth initiatives, delivered by Arts Council England (ACE); and (ii) community and youth initiatives involving volunteers, match-funded and delivered by Pears Foundation and NHS Charities Together (NHSCT). DCMS commissioned the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) and RSM UK Consulting LLP (RSM) to conduct a process and theory-based impact evaluation applying contribution analysis. The contribution analysis assessed evidence across all data sources in relation to developed contribution statements.

The evaluation aimed to understand:

-

How the Fund was designed, set-up and delivered;

-

Key lessons learned across the funded projects;

-

Key lessons learned about different volunteering models (micro, flexible, digital, other);

-

The impact of the Fund on improved volunteer recruitment and retention, and the diversity of volunteers recruited; and

The impact of the Fund on the outcomes for volunteers and organisations and the volunteering sector.

The evaluation report draws on findings from:

-

A Common Minimum dataset (CMD) which captured details of volunteer numbers, demographics (such as age, gender and ethnicity), and types of volunteering opportunities offered (modality and length);

-

In-depth interviews with grantees (n=18) and volunteers (n=36). Grantee interviews explored how the VFF was designed and delivered and gathered evidence about best practice and learning. Volunteer interviews explored volunteering experiences through the VFF, including motivations to volunteer, experiences of recruitment and impacts of volunteering; and

-

A delivery partner focus group with all three delivery partners (ACE, Pears Foundation and NHSCT). The focus group explored how the VFF was designed and delivered, including experiences and lessons learned from onward granting and the implementation of projects.

At the time of the evaluation concluding in October 2023, across the three delivery partners, VFF funded projects had recruited 15,136 volunteers. Of these volunteers recruited, 43% were first-time volunteers. Across opportunities, the most common volunteering modality was ‘other formal’ [footnote 1] (55%) compared to micro (15%), digital (7%) or flexible volunteering opportunities (23%). Key findings from the impact and process evaluation are set out below.

Impact evaluation findings

-

The overarching hypothesis for the VFF is: ‘Young people and people who face barriers to volunteering take up new volunteering opportunities, build new skills, improve their well-being and broaden their social networks, as a result of organisations targeting diverse groups, providing better support to volunteers, and offering new ways of volunteering’. The evidence gathered as part of this evaluation supports this overall hypothesis, by providing strong supporting evidence against two of the underlying contribution statements, and moderate evidence against three of the contribution statements. This suggests the funding package successfully achieved its stated aims and objectives.

-

Overall, the impact evaluation found strong evidence that the VFF supported volunteers from diverse backgrounds to engage in volunteering and delivered subsequent impacts for these volunteers (e.g. increased confidence and wellbeing). There was moderate evidence that organisations improved routes into regular volunteering and increased the number of volunteering opportunities available, and that funding led to improved services. However, at the time of the evaluation concluding in October 2023, there had only been weak evidence identified to conclude that the funding increased learning about and understanding of new models of volunteering and of what works well/less well for improving volunteer recruitment and diversity.

-

Although there was strong evidence to show that the funding programme encouraged participation of individuals from a range of backgrounds, there was more success reaching young volunteers than other groups. Interview data from grantees and volunteers indicated that projects successfully reduced barriers to volunteering through working closely with educational institutions and youth clubs, offering introduction sessions for volunteers, making venues more accessible, and regularly engaging with volunteers to build trust and provide support.

-

There is evidence that the VFF supported projects and organisations to increase volunteering opportunities, leading to improved outcomes for those seeking employment, particularly in relation to the development of skills and knowledge of the labour market. However, there is less evidence to suggest that this directly led to paid employment.

-

Looking at the wider impacts of the funding programme, evidence shows that the VFF contributed to improved services and increased collaboration across the sector. Data from grantee interviews shows that VFF funding helped foster partnership working and enabled tailored volunteering opportunities for target groups.

Key findings from the process evaluation

Design and delivery of the Fund

-

Delivery partners expressed that the Fund objectives were broad enough to allow for a diverse range of projects to be selected. However, short timelines for project selection and delivery significantly impacted the types of projects chosen. Delivery partners indicated they had to adopt a risk-averse approach, selecting grantees with existing volunteer networks and recruitment processes.

-

The Expression of Interest (EOI) stage impacted project selection. Delivery partners predominantly worked with organisations they had pre-existing relationships with, as these organisations had the knowledge and capacity to turn around EOIs quickly and to a higher quality.

-

Delivery partners indicated that grant spending requirements were challenging for grantees. Pears Foundation and NHSCT projects had a requirement to spend the DCMS portion of the grant within the first financial year of the Fund (by March 2022). This impacted project selection, as delivery partners opted to choose capital-intensive projects involving large investments in infrastructure at an early stage.

-

The match-funding element of Strand 2 of the VFF was hugely beneficial and was a facilitator for the success of projects. The funding enabled grantees to have more flexibility with project delivery, enabling adaptations and opportunities for innovation within projects.

Project level delivery findings

-

Grantees had mixed views on the application process, with some ACE grantees finding it time intensive owing to the need to submit within short time scales. However, Pears Foundation and NHSCT grantees felt the application process was proportionate to the amount of awarded funding.

-

Opinions on the monitoring and reporting process were mixed, with some grantees facing challenges with the requirements, particularly when new information was requested part way through delivery.

-

Grantees found support from delivery partners to be key to successful project set-up and delivery. They also benefited from partnerships with other organisations, which helped them to recruit volunteers and raise their profile in new areas. Many grantees co-designed their projects with volunteers, which helped them design activities that were attractive to young people.

-

Grantees used multiple recruitment strategies but found that face-to-face recruitment was most effective for volunteer recruitment, particularly where projects targeted young people. Recruitment was facilitated by using a range of volunteering models (e.g. flexible, micro, and digital).

-

Grantees explained they needed additional time and resources to build trust where they were trying to attract disabled volunteers or those who were more isolated or vulnerable. Grantees working with young volunteers found that reducing the time between sign-up and commencing activities was a critical strategy for successful recruitment and retention. Volunteers cited a range of factors that encouraged them to continue volunteering including positive experiences while volunteering (for example, increased wellbeing or learning new skills) and engaging in roles that had been tailored to their individual needs and interests.

Recommendations for future fund design and delivery:

-

Increase timelines for delivery (and flexibility with grant spending within the delivery window) to allow for innovation within projects and sufficient time to build trust with new groups of volunteers – this would help to ensure that volunteering projects attract individuals from all backgrounds. This would also enable further opportunities for learning and collaboration across the volunteering sector. The use of match-funding elements could aid with this through providing more flexibility to grantees with grant spending.

-

Lengthen the application process to allow grantees to collaborate on applications with multiple partners – the evaluation found that partnerships were key to engaging new groups of volunteers and trialling new approaches.

-

Ensure that project timelines allow sufficient time for volunteer recruitment – this will allow grantees to involve those who have not volunteered before or have barriers to volunteering (e.g. disabled volunteers). Additional time should be factored in both for working with gatekeepers (if applicable) and working with new volunteers.

-

Ensure a range of volunteering modalities are offered across (and within) funded projects – this includes micro, digital and flexible approaches as well as more traditional volunteering roles. Micro and flexible roles can help recruit those with barriers to volunteering. To aid volunteer retention, volunteering opportunities need to be flexible to volunteer needs and allow volunteers to change modality at different points in their volunteer journey or if their circumstances change.

-

Offer volunteers greater ownership and agency in volunteering activities – findings from the evaluation indicate that volunteers valued engaging with activities that adopted elements of co-production or enabled volunteers to guide their own volunteer journey, such as by choosing activities. By consulting with volunteers throughout the process of activity development, in open and ongoing feedback, projects can ensure greater retention of individual volunteers.

-

Ensure that future funds provide opportunities for collaboration across the sector – for example through delivery partner level events for grantees, or funding specific projects which build infrastructure for collaboration across the voluntary sector. The evaluation showed that collaboration between different projects is key to reaching new groups of volunteers and tailoring opportunities for target groups.

1. Introduction

The National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) and RSM UK Consulting LLP (RSM) were commissioned by the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) to conduct an evaluation of the Volunteering Futures Fund (VFF). The evaluation aimed to understand how the Fund was designed, set-up and delivered, lessons learned across projects, and the impact of the Fund on the outcomes for volunteers, organisations and the volunteering sector. The evaluation ran from October 2022 to October 2023. Although NHSCT and Pears Foundation projects finished delivery in March 2023, ACE projects are not scheduled to finish delivery until March 2024. Insights from ACE projects were gathered through grantee and volunteer interviews and CMD data collection, but the evaluation findings do not include the full picture of impact and reach for ACE projects.

1.1 Background to the VFF

The VFF is a £7.4 million fund which aimed to support high quality volunteering opportunities for young people and those who experience barriers to volunteering. It was launched in 2021 by DCMS and was delivered through three delivery partners: Arts Council England (ACE), NHS Charities Together (NHSCT) and Pears Foundation. The Fund aimed to test and trial solutions to known barriers to volunteering using micro, flexible and digital approaches. The VFF was delivered through two strands:

-

Strand 1: funding for volunteering projects across arts, culture, heritage, sport, civil society, and youth initiatives. This was delivered by ACE, which awarded £4.65 million of VFF funds across 19 projects running until March 2024.

-

Strand 2: funding for community and youth initiatives involving volunteers. This was match-funded and delivered by Pears Foundation (£550,000 across six projects) and NHSCT (£624,000 across 14 projects) until March 2023 [footnote 2].

The overarching objectives of the Fund included:

-

Improving the accessibility of volunteering, particularly among young people and those who experience barriers to volunteering (that is, volunteering rates tend to be lower among those who experience loneliness, those with disabilities and those from ethnic minority backgrounds);

-

Increasing the skills, wellbeing, and social networks of volunteers, and reducing levels of loneliness;

-

Encouraging and exploring innovation and scaling of volunteering practices that may have emerged during the pandemic;

-

Learning about the comparative effectiveness of different volunteering models (e.g. flexible, micro and digital) and recruitment approaches for engaging and sustaining volunteers;

-

Strengthening volunteer pipelines in DCMS sectors and widening participation in, engagement with and access to arts, culture, sport and heritage activities and places; and

-

Leveraging additional investment towards volunteering initiatives through a match funding challenge.

Previous research highlighted that certain groups are less likely to volunteer, including those who live in more deprived areas [footnote 3], potentially because there are fewer volunteering opportunities available. Volunteering is also less common among those aged 25 to 34 than older age groups [footnote 4]. Young people, volunteers from ethnic minority backgrounds, and disabled people are more likely to have had a negative experience of volunteering, with those from ethnic minority backgrounds having lower levels of volunteering satisfaction. Disabled volunteers are also more likely to say that volunteering had negatively impacted their health and wellbeing than non-disabled people [footnote 5]. The VFF targeted a range of people facing barriers to volunteering, with a focus on young people, disabled people, people from ethnic minority backgrounds and those living in deprived areas.

1.2 Report Structure

This report is divided into the following sections:

-

Chapter 2 provides a brief overview of the methodology for each work strand, including the research aims and contribution analysis approach.

-

Chapter 3 reports on findings from the Common Minimum Dataset (CMD), offering an overview of the volunteer recruitment for the VFF, including numbers and demographics of volunteers reached as well as modalities of volunteering opportunities.

-

Chapter 4 presents the process evaluation findings, drawing on evidence from the delivery partner focus group, grantee, and volunteer interviews.

-

Chapter 5 presents impact findings based on the contribution analysis. The section is structured by contribution statements, and evidence from across work strands is drawn on to assess the strength of evidence and alternative explanations for each contribution statement.

-

Chapter 6 offers conclusions and recommendations. The chapter provides a list of key findings, lessons learned, and recommendations for future fund design, delivery, and evaluation.

2. Methodology

2.1 Overview of the evaluation

Prior to the start of the evaluation, a feasibility study was commissioned by DCMS to develop evidence-based options for a robust and independent evaluation. This scoping work involved a desk review of relevant documents, grantee level discussions, discussions with non-funded applicants, and further development of the existing Theory of Change (ToC). A range of evaluation options were considered, including Quasi Experimental Design. However, they were not deemed feasible due to the challenge of identifying a suitable comparison group that could assess the individual and organisation-level outcomes, as well as the additional costs required for such an approach. Therefore, the recommended approach was a process evaluation and a theory-based impact evaluation applying contribution analysis [footnote 6]. Findings from both the process and theory-based impact evaluation are presented in this report. The following chapter provides an overview of the methodology for the evaluation. Full details of the methodology can be found in Appendix 2 .

2.2 Research Aims

Process evaluation research questions

Fund design

-

How was the Fund designed, including how were delivery partners and projects selected?

-

How appropriate were the design and objectives of the VFF?

Project set-up

-

How were projects implemented?

-

What types of projects were reached?

*What worked well and less well with the recruitment of volunteers?

- Which approaches worked to bring on-board first-time volunteers and those more likely to face barriers to volunteering?

Lessons learned

-

What were the strengths, weaknesses and lessons learned from different volunteering models (micro, flexible, digital, other)?

-

What, if any, were the unintended consequences of the programme (such as the impact on the services that volunteering organisations provide or run)?

-

What lessons could be learned for future interventions?

Theory-based impact evaluation research questions

-

What impact did the VFF have on outcomes for volunteers (i.e. is there a link between volunteering and improved wellbeing, reduced loneliness, increased feelings of community connectedness and the development of skills)?

-

What impact did the VFF have on outcomes for organisations (i.e. to what extent did organisations see an increase in volunteer recruitment and retention, and the diversity of volunteers recruited)?

-

How did impact vary by volunteering opportunity?

-

How did impacts vary for different groups of volunteers (e.g. young people, disabled people)?

2.3 Theory of Change

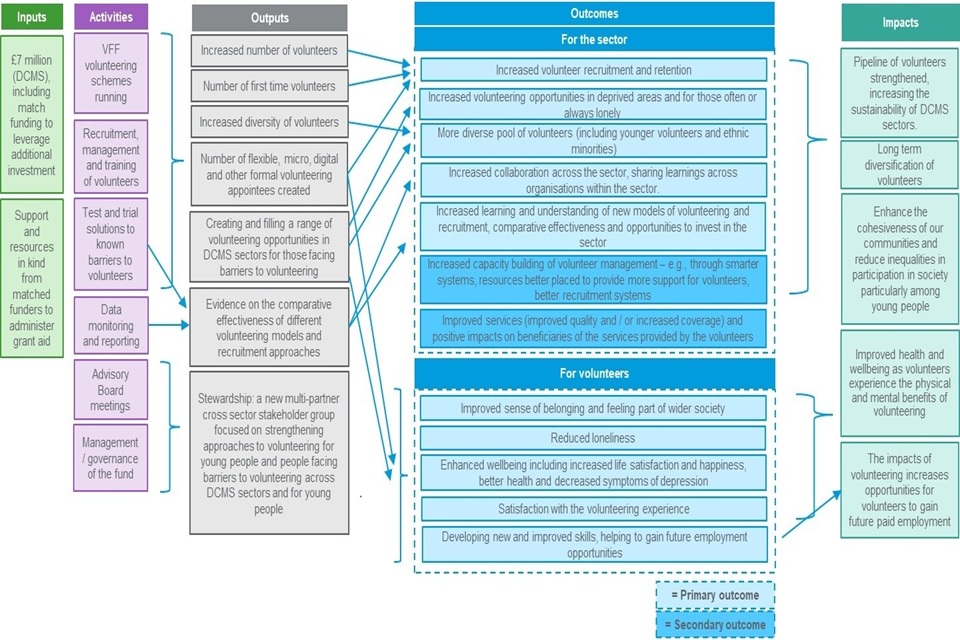

The Theory of Change (ToC) reflects how the VFF was expected to lead to changes for the organisations and individuals it supported (see Appendix 1). An initial ToC was provided to the evaluation team by DCMS. This was further during the feasibility study through a desk review of documentation and data relating to the VFF, discussions with grantees and a ToC workshop with DCMS.

2.4 Contribution analysis

The impact evaluation applied contribution analysis. Contribution analysis provides a pragmatic framework for evaluators to make credible causal claims where the ToC is complex, and infer whether the projects have made a difference and contributed to the impacts observed. The approach revises theories about how particular outcomes arose, with evidence collected to confirm or discount any alternative explanations. CMD, grantee and volunteer interview data, and data from the delivery partner focus group were triangulated to inform the contribution narrative and its assessment. This assessment was framed by six ‘contribution statements’ which were based on the VFF ToC (see Appendix 2). Relevant evidence that supported or conflicted with each statement was identified, allowing an assessment of whether the assumptions behind the VFF’s effectiveness were plausible, whether it was implemented as per the ToC and whether the chain of expected results occurred.

2.5 Common Minimum Dataset (CMD)

A Common Minimum Dataset was designed as part of the feasibility study for grantees to capture details of volunteer numbers, demographics, and types of volunteering opportunities offered (see Appendix 4). The final CMD form for ACE grantees will be submitted directly to ACE in March 2024. This data is not included in our CMD analysis and reporting as it is outside the evaluation’s scope. The CMD data presented in this report for ACE grantees therefore shows an incomplete picture of the reach of ACE projects.

2.6 Grantee interviews

In-depth interviews with grantees explored how the VFF was designed and delivered and gather evidence about best practice and learning. Interviews were conducted from December 2022 to February 2023. 18 grantees out of a total of 39 projects were sampled, between ACE (10/19), NHSCT (5/14) and Pears Foundation (3/6) projects. As some ACE projects were not due to start delivery with volunteers until after the interview period, we sampled to include those further along in recruitment of their volunteers.

2.7 Delivery Partner focus group

A focus group with representatives from all three delivery partners (ACE, NHSCT and the Pears Foundation) took place in May 2023 via Microsoft Teams. The focus group explored how the VFF was designed and delivered, including experiences and lessons learned from onward granting and the implementation of projects.

2.8 Volunteer interviews

In-depth interviews were conducted with 36 volunteers from 10 ACE projects [footnote 7] and sub-projects between March and July 2023. The “primary sampling criteria” was volunteering model (micro, flexible, digital, or other) and “secondary level criteria” ensured a range of demographics were included (e.g. gender, age, ethnicity, health and disability). The interviews explored volunteering experiences through the VFF, including motivations to volunteer, recruitment experiences, and any impacts of volunteering.

2.9 Timing of the Evaluation

The evaluation ran from October 2022 to October 2023. Although NHSCT and Pears Foundation projects finished delivery in March 2023, ACE projects are not scheduled to finish delivery until March 2024. Insights from ACE projects were gathered through grantee and volunteer interviews and CMD data collection, but the evaluation findings do not include the full picture of impact and reach for ACE projects [footnote 8]. This is a limitation of the evaluation and is discussed further in Chapter 6.

3. Overview of volunteer recruitment

This chapter reports on findings from the CMD, offering an overview of volunteer recruitment for the VFF, including the numbers and demographics of volunteers recruited and the modality and length of volunteering opportunities. For NHSCT and Pears Foundation projects, the data presented below covers the whole of their delivery period, with their final CMD forms submitted in March 2023. For ACE grantees, the data presented below is from September 2023, six months prior to the end of project delivery and therefore shows an incomplete picture of the reach of ACE projects (see section 2.9).

3.1 Numbers of volunteers recruited

Across the three delivery partners, VFF funded projects recruited 15,136 volunteers who were new to organisations (5,331 through ACE projects, 1,962 through NHSCT projects and 7,843 through Pears Foundation projects). Most volunteers were either recruited through Pears Foundation or ACE funded projects with 52% and 35% of volunteers respectively. Of the 15,136 volunteers recruited, 43% were first-time volunteers. This refers to people who have never formally volunteered (given unpaid help to groups or clubs) before and was self-defined by the volunteers. Table A2 in Appendix 3 details the full breakdown of first-time volunteers segmented by delivery partner.

3.2 Volunteer demographics

At the outset of the programme, VFF funded projects selected their target volunteer groups. The groups targeted were not mutually exclusive as projects could target more than one type of volunteer group. As illustrated in Table 1, most of the projects targeted young people aged 16 to 25, with 82% of projects falling into this category. The following volunteer groups were also targeted by many projects: people living in deprived areas (67%), disabled people (59%) and people from ethnic minority backgrounds (56%). Further detail on the breakdown of volunteer groups targeted by delivery partners can be found in Table A3 in Appendix 3.

Table 1: Volunteer groups targeted by projects (n=39)

Number of projects targeting different volunteer groups

| Universal | People from ethnic minority backgrounds | Young people (16 to 25) | People living in deprived areas | Disabled people | Other targeting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | 22 | 32 | 26 | 23 | 3 |

Across the programme, and when broken down by delivery partner, many more female volunteers were recruited than volunteers who were male, non-binary or self-defined their gender (Table 2). The totals provided for gender do not include all volunteers recruited through the projects as some projects chose to collect data on sex rather than gender. It was up to the grantees’ discretion whether to collect data on volunteer sex, gender or both. Seven projects across the Fund chose not to collect data on volunteers’ gender and therefore are not included in the tables. These seven projects accounted for 4,072 volunteers.

A large proportion of volunteers also fell into the following categories: young people (16-25) (38%), and those from ethnic minority backgrounds (16%). NHSCT projects predominantly recruited young people, with 99% of all volunteers recruited by these projects falling into this category. Pears Foundation projects typically had a lower representation of young people with just 14% of volunteers belonging to this age group. Among the recruited volunteers, ACE had a higher percentage of disabled volunteers, with 13% of their total volunteers being disabled, as opposed to 6% for Pears Foundation and 2% for NHSCT.

Table 2: Volunteer groups recruited[footnote 9]

| Type of volunteer groups reached | Number of volunteers: programme-wide |

Number of volunteers: ACE |

Number of volunteers: NHSCT |

Number of volunteers: Pears Foundation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young people (16 to 25) | 5798 | 2779 | 1939 | 1080 |

| Ethnic minorities | 2344 | 1014 | 394 | 936 |

| People with disabilities | 1146 | 631 | 37 | 478 |

| Male (Gender) | 1584 | 1391 | 97 | 96 |

| Female (Gender) | 3501 | 2393 | 433 | 675 |

| Non-binary/self-defined (Gender) | 332 | 305 | 8 | 19 |

| Total | 15136 | 5331 | 1962 | 7843 |

3.3 Modality of volunteering opportunities

At the outset of the programme, VFF funded projects outlined the modality or types of volunteering opportunities they planned to offer. As illustrated in Table 3, flexible volunteering projects were most targeted with 32 projects (82%) planning to include flexible opportunities. However, micro and digital volunteering opportunities were also largely targeted, with 28 projects (72%) planning to include micro opportunities and 28 projects (72%) planning to include digital opportunities. The ‘other formal’ category [footnote 10] was the least common at the outset of the programme, with 26 projects (67%) planning to recruit volunteers into this category. More detail on the breakdown of volunteering opportunities targeted by delivery partners can be found in Table A4 in Appendix 3.

When comparing the types of projects targeted at the outset of the programme to the types of project subsequently offered, the biggest change was seen with digital opportunities. At the outset of the programme 28 projects (72%) stated they were targeting digital opportunities compared to 23 projects (59%) which subsequently offered digital opportunities. There were also slightly fewer projects offering micro and flexible opportunities (26 (67%) and 30 projects (77%) offered compared to 28 (72%) and 32 (82%) targeted at the outset, respectively). In comparison, there were slightly more projects offering ‘other formal’ opportunities (27 projects, 69%) compared with the number targeting these at the outset of the programme (26 projects, 67%). However, volunteer modalities were not mutually exclusive, and many projects offered multiple volunteer modalities, so the total of all opportunities does not equal 39 (the total number of projects).

Table 3: Types of volunteering opportunities which were targeted at programme outset and subsequently offered (n=39)

Number of projects

| Micro | Flexible | Digital | Other formal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of projects targeting types of of volunteering opportunity at the outset of the programme) | 28 | 32 | 28 | 26 |

| Number of projects offering types of volunteering opportunity | 26 | 30 | 23 | 27 |

Table 4 below outlines the number of volunteers recruited in each type of volunteering model. The most common form of volunteering opportunity recruited into was ‘other formal’ with 55% of reported modalities being this type of opportunity. Volunteering opportunities categorised as ‘other formal’ include mixed modalities (e.g. digital and flexible) as well as regular volunteering opportunities which are not micro, flexible or digital. This helps account for the notably high number of volunteers categorised in ‘other formal’ volunteering opportunities. Not all grantees counted volunteers participating in multiple modalities as being in the ‘other formal’ category but instead counted the volunteer for each modality. While the volunteers were counted as a single volunteer in terms of total number of volunteers recruited, they contributed to more than one type of volunteering opportunity in Table 4.

ACE and NHSCT projects recruited more volunteers into flexible opportunities than ‘other formal’ opportunities, with these accounting for 36% and 45% of reported modalities respectively. Overall, fewer volunteers were recruited into micro and digital opportunities.

Table 4: Number of volunteers recruited in micro, flexible, digital, or ‘other formal’ volunteering opportunities[footnote 11]

Volunteer numbers by delivery partner

| Modality | Programme-wide | ACE | NHSCT | Pears Foundation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Micro | 2382 | 2087 | 178 | 117 |

| Flexible | 3685 | 2150 | 987 | 548 |

| Digital | 1199 | 258 | 213 | 728 |

| Other formal | 8742 | 1438 | 824 | 6480 |

3.4 Length of volunteering opportunities

As illustrated in Table 5, across the programme most volunteers were involved in long-term volunteering opportunities, defined as opportunities longer than six months or still ongoing. This represented 64% of the recorded volunteering opportunities where length of volunteering opportunities was reported. Conversely, 19% of volunteers were engaged in opportunities shorter than six months and 17% attended volunteering opportunities that were one-off.

There was a more even split across ACE projects, with 34% of volunteers taking part in one-off opportunities, 30% in short-medium opportunities, and 36% in long-term opportunities. In contrast, Pears Foundation and NHSCT volunteers were primarily recruited into long-term opportunities (Table 5).

Table 5: Length of volunteering opportunity[footnote 12][footnote 13]

Volunteer numbers by delivery partners

| Timescale | Programme-wide | ACE | NHSCT | Pears Foundation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-off | 2351 | 1790 | 276 | 285 |

| Short-medium | 2676 | 1577 | 727 | 372 |

| Long term | 9001 | 1939 | 1028 | 6034 |

4. Process evaluation findings

This chapter reports on findings from the process evaluation, drawing on evidence from the delivery partner focus group, grantee interviews, CMD data and volunteer interviews. The interviews were conducted with a selection of participants for each group and allowed us to capture the range and diversity of views and experiences, but are not statistically representative of the population. Therefore we do not give a sense of the scale and strength of their views as the sampling approach was not designed for this purpose. [footnote 14]

4.1 Design of the Fund

Impact of timelines on project selection and delivery

Delivery partners (ACE, Pears Foundation and NHSCT) had mixed views about the overall design of the Fund. Generally, the delivery partners felt the objectives set by DCMS for the Fund were very broad. This approach allowed them to select a more diverse range of projects and gave them more flexibility to focus on areas of their own particular interest. However, delivery partners felt that timelines for project selection and delivery were short which directly influenced the types of projects they selected. They took a more risk-averse approach by selecting grantees which had existing volunteer networks and recruitment processes as they felt grantees with little or no volunteer infrastructure might not successfully deliver within the short delivery timeframe.

In order to meet those timelines, we had to select projects where there was already that existing framework. If you want really innovative, new, dynamic projects that are grown from nothing, you couldn’t do it in the timelines we had.

- Delivery partner

Similarly, delivery partners felt that the short Expression of Interest (EOI) stage led them to predominantly select organisations they had pre-existing relationships with, despite receiving many EOIs from organisations they had not worked with before. They felt these organisations had the knowledge and capacity to produce EOIs much quicker, and to a higher quality. Delivery partners emphasised that the short timeframes limited the diversity of grantees selected and led to the selection of more risk-averse and (potentially) less innovative projects. Timelines also impacted the ability of projects to forge new partnerships or reach new volunteer groups.

Grant spending requirements

Grant spending requirements were cited as a challenge, particularly for NHSCT and Pears Foundation grantees. Projects had a requirement to spend the DCMS portion of the grant within the first financial year of the Fund (by 31st March 2022) [footnote 15]. To ensure grantees could complete all DCMS funded activities within that five-month period, delivery partners selected many capital-intensive projects, such as projects involving large investments in infrastructure at an early stage.

Match-funding element

Strand 2 of the VFF involved pilots match-funded and delivered by NHSCT and Pears Foundation. DCMS’ total funding of £1.17 million for Strand 2 was to be spent by March 2022 with the equal match-funding element, provided by delivery partners, to be spent by 2023. NHSCT and Pears Foundation delivery partners agreed that the match-funding element was hugely beneficial and was a facilitator for the success of projects. For example, one delivery partner explained that the match-funding enabled them to be much more flexible with grantees, allowing adaptation to delivery and opportunities for innovation within projects as the matched funding could be spent over a longer period.

4.2 Delivery of the VFF at project level

Application and monitoring

Pears Foundation and NHSCT grantees interviewed felt the application process was proportionate to the awarded funding. Many grantees cited their existing relationship with the delivery partner or support received from the delivery partner during the application process as a key facilitator. There were mixed views among ACE grantees, with some grantees finding the application process lengthy and required in a short turnaround. This was particularly the case for grantees working with downstream partners who needed to gather all partners’ data and evidence for the application form.

Views on monitoring and reporting were mixed. ACE grantees had more positive experiences with monitoring arrangements with many describing the forms as ‘light touch’ in comparison to their experience with other funders. Other grantees faced challenges with the requirements, particularly when new information, such as demographic data, was requested part way through delivery. Due to sensitivity issues, grantees also highlighted challenges collecting demographic data with new or vulnerable volunteers.

Project design, set-up, and delivery

A key facilitator to project set-up and delivery for grantees was support from the delivery partners, especially in helping them understand the monitoring processes and providing flexibility with any required changes to delivery. However, grantees who were not using a significant portion of their budget for capital investments (e.g. in technology or infrastructure) reported that it was challenging keeping to the planned spending requirements. In particular, Pears Foundation and NHSCT grantees highlighted that it was difficult spending the entire DCMS grant budget by 31st March 2022, the end of the first financial year of the grant.

We had a very short space of time to spend quite a large amount of that money… we had to spend [tens of thousands of pounds] within the space of about two months.

- NHSCT grantee

Partnerships between grantees and other downstream organisations played a pivotal role to successful project set-up and delivery. Partnerships were established for a variety of reasons, including supporting the recruitment of volunteers, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Several grantees established new partnerships to raise their organisation’s profile in new areas and reach groups they had not previously engaged with. ACE grantees working with multiple delivery partners utilised steering groups, advisory boards, or monthly meetings to foster collaboration and learning between partners.

Many grantees co-designed their projects with volunteers, particularly if their projects targeted young people. Co-design was used as an opportunity to assess what activities would attract young people into volunteering or to make adaptations to existing activities based on feedback. Co-design generally occurred very early on in the project and grantees emphasised the importance of allocating sufficient time for effective co-design within the overall project design. Many NHSCT grantees highlighted the importance of pre-project outreach with schools and colleges and young people, which expedited recruitment as it enabled them to mitigate against stringent, time-consuming NHS volunteer recruitment processes.

Volunteer recruitment

Volunteers described several ways they first heard about or became involved in VFF volunteering opportunities. These ranged from seeing advertisements on social media (in particular Facebook or Instagram), to finding out about opportunities through their own research or hearing about the opportunity through youth clubs or educational institutions (for example through a stall at a university fair).

Although grantees used multiple recruitment strategies, they reported that volunteer recruitment was generally slower than expected. Grantees found that face-to-face recruitment was the most effective, particularly where projects targeted young people by recruiting from places they frequent, such as schools or barbershops. For some grantees this was a tried and tested approach, while others, especially organisations targeting a new demographic of volunteers, were adopting it for the first time. Similarly, recruitment through word of mouth from existing volunteers was noted as effective. Social media was found to be a less effective approach; however, it is unclear whether this was because of poor implementation by grantees or their partners or other factors.

We’ve got social media up and running, the best way at the moment for us to recruit volunteers is to be out and about talking to people…I was surprised that social media hasn’t actually gone the way we thought it would.

- ACE grantee

Several grantees explained they needed additional time and resources to build trust where they were trying to attract disabled volunteers or those who were more isolated or vulnerable. In comparison to other volunteer groups, grantees felt that young people needed to be incentivised to engage in their activities (for example, by using the volunteering opportunity as work experience). Grantees working with young volunteers found that reducing the time between sign-up and the commencement of activities was also a critical strategy for successful recruitment and retention. This finding was mirrored in the volunteer interviews, with volunteers reporting that this maintained their motivation and enthusiasm to be involved.

Volunteers discussed several factors that were key to deciding whether to participate in volunteering. Clear and effective communication from organisations about what the volunteering would involve (including specific tasks and timings) was important, particularly for volunteers who had not volunteered before or were nervous about volunteering. Volunteers who needed flexibility in their role were reassured when they were told about flexibility early on and cited this as a factor in deciding to sign up. Volunteers appreciated when volunteering opportunities had a simple and easy recruitment process, such as signing up online using tick boxes rather than a written application, and a lack of tests or interviews. Volunteers felt this made opportunities more accessible to them.

That was partially what made it [the volunteering opportunity] more accessible because it’s not like I had to pass any tests or anything beforehand

- Volunteer

For young volunteers and disabled volunteers, recruitment through educational institutions was key, including advertising roles through work experience coordinators at schools and colleges, and making use of university networks and platforms, such as online job boards, to advertise opportunities. Interviews with volunteers also highlighted the need for tailored recruitment and onboarding approaches for different volunteers. One volunteer who struggled with their mental health described how someone came to their house to talk about the project, which they felt was a very positive start to their involvement.

Approaches for on-boarding first-time volunteers and those more likely to face barriers to volunteering

The successful approaches for volunteer recruitment outlined above, such as using social media and partnerships with educational institutions, were also successful with first-time volunteers and those facing barriers to volunteering. First-time volunteers, especially young people and disabled people, were likely to have been referred to the volunteering opportunity by a support worker, teacher or youth club leader. Participants from this group highlighted the importance of a welcome or introductory session to get to know the team and the other volunteers. They described how knowing people before the start of volunteering made them not feel like an outsider, as they had already built connections with other volunteers and staff. This was an important factor in their interest and motivation to volunteer. A key previous barrier to volunteering for this group was a lack of confidence. Volunteers mentioned that introductory sessions helped build their confidence and made them feel they were in a safe environment.

Volunteers who had previously faced barriers to volunteering or had negative experiences of volunteering found that the organisations were more responsive to their physical and emotional needs than the previous organisations they had volunteered with. A volunteer with a long-term health condition mentioned that the organisation always made sure they had somewhere to sit if needed which improved their volunteering experience.

Grantees interviewed described several key lessons learned for engaging first-time volunteers. They emphasised the importance of taking a proactive approach to recruitment and visiting places frequented by target volunteer groups such as schools, colleges, youth clubs, shopping centres and universities. Grantees also felt that it was important for project workers to engage with volunteers regularly, particularly those with additional needs, to build trust and provide support. However, many of these grantees also highlighted the resource-intensive nature of this approach.

Volunteer Retention

Grantees found that co-designing project activities with young people was effective in ensuring activities were relevant and had the buy-in from volunteers. They described how co-production led to projects that volunteers felt more ownership towards and were more interested in. Ensuring volunteers were assigned to activities/tasks they found relevant and passionate about was also key to successful retention.

Retention is higher when people are in volunteering roles they actually are interested in. I understand that for students it could be a time-limited opportunity: but that doesn’t mean it can’t be meaningful.

- Pears Foundation grantee

Volunteers also highlighted several factors that encouraged them to continue volunteering. These included being impacted positively by the role (e.g. through increased wellbeing, learning new skills or meeting new people) and roles tailored to individual needs and interests. Many organisations with flexible and micro opportunities had various volunteering opportunities available, which volunteers cited as a factor influencing retention, as they could engage with the most interesting opportunities for them.

For NHSCT grantees, partnering with schools and colleges for work experience aided retention as it guaranteed a certain number of volunteer hours. Both grantees and volunteers emphasised the importance of making volunteers aware of available opportunities and managing expectations early. A few grantees used celebratory events or gave awards to volunteers to show recognition for their input.

We’ve developed a long service award badge, so they get a badge for one year’s service and two years’ service…The engagement activities have definitely helped our retention, making it more fun for them.

- NHSCT grantee

Volunteers also appreciated projects that collected ongoing feedback from volunteers as they felt this improved their experiences and made them feel valued. One volunteer with a long-term health condition highlighted to an organisation that the online platform for volunteers did not include accessibility information about venues and appreciated that this was quickly changed after they discussed it with project staff.

Interviews with volunteers also identified several barriers to retention. These included volunteers feeling like their skills were not being fully utilised in their roles, a lack of communication about future volunteering opportunities and projects which were aimed at certain age groups (e.g. young people) not being able to accommodate volunteers in other projects once they become older than the targeted age range.

4.3 Strengths, weaknesses and lessons learned from the different volunteering models (micro, flexible, and digital volunteering)

Although there are clear distinctions between the models in terms of their definitions (see sections below), many grantees did not use the same terminology. Many volunteer roles were either not clearly defined as a particular type of volunteering or combined models (e.g. digital and flexible). Grantees who did not relate to the terminology used were therefore unable to comment on specific learnings or experiences compared to a ‘regular’ or existing model. Some volunteers who took part in VFF funded projects were also involved in regular volunteering and in some cases, volunteering models changed based on volunteer needs, for example a flexible opportunity becoming more regular volunteering if that suited a volunteer best. The following section draws on findings from the delivery partner focus group, grantee interviews and volunteer interviews.

Micro volunteering

Micro volunteering is defined as volunteering to do specific time-bound tasks that can be undertaken as one-off. Examples described by volunteers who took part in interviews included attending one-off conservation sessions, supporting with an anniversary event for a local arts venue or volunteering as an invigilator for a late-night museum event.

Fewer volunteers were recruited into micro-opportunities, as detailed in the CMD analysis in Table 4, with 2,382 volunteers recruited into these roles across the three delivery partners. Grantees who had delivered micro opportunities described using them in conjunction with other types of volunteering activities, with the opportunity for volunteers to progress to longer-term volunteering. A couple of NHSCT grantees explained their choice not to use micro-opportunities in their projects due to the lengthy nature of NHS recruitment processes. Because it includes extensive background checks and mandatory training, micro volunteering opportunities were not feasible to offer.

One-off opportunities, you can’t really integrate into volunteer services in the NHS because of the amount of training and time it takes to get all of your checks done just to volunteer for one day.

- NHSCT grantee

Volunteers described several positive aspects of micro volunteering. For those who hadn’t volunteered before, micro opportunities were a good opportunity to try out volunteering without a longer-term commitment. Because each micro volunteering session was stand alone, organisations often provided detailed information about what would happen during the volunteering session. Volunteers felt that this helped to break down barriers to volunteering as they could fully prepare for the session and therefore felt more confident. Volunteers also appreciated the fact that micro volunteering meant they could plan volunteering around other commitments related to work, study or family. This was particularly useful for volunteers with changing schedules, such as those with varying work schedules or university students. Micro volunteering opportunities worked particularly well for disabled volunteers who needed to attend sessions with their support worker. Because their time with their support worker(s) was limited, micro volunteering opportunities were easier to co-ordinate in relation to their support worker’s availability. This may not have been possible for some volunteers with a longer-term volunteering opportunity.

Volunteers also highlighted negative aspects related to micro volunteering. Volunteers who wanted to be involved in volunteering longer term or continue volunteering with the same organisation sometimes felt frustrated that micro opportunities were ‘one-off’ and some volunteers felt that organisations did not communicate well about whether there would be any future opportunities.

Flexible volunteering

Flexible volunteering is where volunteer services have no regular commitment pattern or a minimum stipulated number of hours. Examples described by volunteers who took part in interviews included volunteering opportunities where you can sign up for suitable shifts using an online platform (e.g. to steward during a theatre or music performance) or volunteering on a farm (e.g. looking after animals, planting) where there was flexibility on the days they could attend. This was the second most common volunteering mode across the programme, with 3,637 volunteers recruited into flexible volunteering opportunities.

In general, volunteers felt positive about flexible volunteering opportunities. Similar to micro opportunities, they highlighted that they could fit volunteering around other commitments, such as work or education.

If I’m like, ‘Oh, I know I signed on to this thing that’s tomorrow, but I’m really, really behind on my work,’ they’ll just be like, ‘Yes, don’t worry about it. Thanks for letting us know,’ and you can easily just sign off from the shifts on the app.

- Volunteer

Flexible volunteering allowed volunteers with long term, and often unpredictable, health problems to sign up to volunteer when they felt able – even last minute. This was particularly the case for grantees with online sign-up systems, enabling volunteers to sign up to or cancel sessions at short notice. Other benefits of flexible volunteering highlighted by volunteers included feeling more engaged with volunteering because the flexibility made it feel like a choice, rather than something they had to do. This was key for the engagement of volunteers who were apprehensive about volunteering or had previous negative experiences.

Volunteers also highlighted negative aspects of flexible volunteering. One example related to the fact that flexible opportunities had varied staff and volunteers at each session. This meant that for volunteers with complex and specific needs, these were not always known and therefore could not be met. This situation was described in contrast to other regular volunteering situations where staff could build longer term relationships with volunteers, making it easier to provide support. Some volunteers also felt that flexible volunteering didn’t provide the same structure as more regular volunteering slot (e.g. the same day each week), to enable them to plan around the volunteering role more easily. One disabled volunteer highlighted that a regular schedule would work better, allowing them to schedule attendance with their support worker.

Grantees and delivery partners were also asked about flexible volunteering and had mixed views on the success of these opportunities. Pears Foundation projects felt the approach was largely successful and was particularly attractive for volunteers with other time-consuming commitments such as caring for young children. As set out above with micro opportunities, a key barrier to delivery for NHSCT grantees again was difficulty recruiting for flexible roles within the constraints of NHS recruitment processes.

Digital volunteering

Digital volunteering is defined as volunteering which takes place digitally, either remotely or in person. Examples of this described in the grantee and volunteer interviews included volunteering involving local history research using a laptop provided by a funded project or digitalising museum archives. Only a few projects offered digital volunteering opportunities. This is reflected in the CMD analysis which reports just 1,191 digital volunteering opportunities were taken up across the three delivery partners (Table 4).

Interviews with grantees found that several projects had planned to offer digital volunteering at the outset of the programme but were unable to proceed with this approach in practice. These grantees generally found that there was less demand for digital opportunities than previously anticipated, and therefore shifted to other types of opportunities.

We thought we’d do more digital opportunities, but this hasn’t happened, we’ve had very low uptake. I was surprised that digital and social media use hasn’t actually gone the way we thought it would.

- ACE grantee

For the few grantees who did offer digital volunteering opportunities, it was reported that a high level of investment was required during their set-up phase to develop and establish the digital infrastructure required to deliver digital volunteering activities. A delivery partner highlighted that projects have potentially duplicated efforts in developing digital assets. For instance, they found that many of the grantees were individually investing in and creating portals for their volunteering opportunities and suggested the need for sharing knowledge on setting up digital assets to avoid unnecessary, duplicated costs across these organisations.

Volunteers interviewed described being able to use their own digital equipment if they wished or being provided with good quality digital equipment such as laptops, allowing them to easily do their volunteer role and appreciated the independence that digital volunteering gave them. Volunteers also appreciated the flexibility of working from home or from an office. Challenges highlighted by volunteers related to the supply of equipment. One volunteer described having to miss their volunteering session on occasion as there were not sufficient laptops for all volunteers.

Lessons learned from the different volunteering models

Volunteer interviews highlighted several lessons learned related to volunteering models. All three models had strengths and weaknesses. Although it was clear that micro and flexible opportunities appealed to those who had not volunteered before, there were no clear associations between models and the recruitment and retention of different groups. Whether a model worked for a particular volunteer was based on several personal factors, including the point at which a volunteer was in their volunteering journey. For example, for some volunteers micro volunteering was key to their initial recruitment but to stay involved longer-term, they would prefer a more formal arrangement with a regular schedule. Thus, allowing volunteers to change model at different points in their volunteer journey could facilitate the longer-term retention of young volunteers and those who experience barriers to volunteering. Interviews with volunteers also highlighted the challenges of digital equipment availability for digital volunteering and grantees described the high levels of investment needed in the set-up of digital volunteer projects. Going forward, funding for or availability of digital equipment should be considered when funding digital volunteering projects.

Delivery partners felt that whilst some valuable lessons were learned about volunteer recruitment and retention, they were not ground-breaking, and approaches taken often aligned with standard practices. They felt this was because the projects had little freedom to experiment and innovate (see section 4.1).

4.4 Lessons learned for future interventions

This chapter has set out how the Fund was delivered and some of the key challenges and successes related to delivery at both fund and project level. Several key lessons learned from the process evaluation are set out below.

-

Funders need to build in an appropriate amount of time if planning to reach new groups of volunteers, especially those who face barriers to volunteering

Delivery partners and grantees felt that for grantees to reach new groups of volunteers, the funding timelines should be lengthened.[footnote 16] As a result of the shorter timelines, delivery partners reported that they often selected projects with existing volunteer frameworks and recruitment processes with groups of volunteers they were familiar with and were not trialling new, innovative approaches with new groups.

-

Including match-funding elements within volunteering funds can allow greater flexibility for grantees and lead to new and innovative approaches

Delivery partners felt positively about the match-funding element of the Fund as it allowed grantees to be more flexible with their delivery which provided opportunity for adaptation and innovation.

-

Where projects are expected to involve multiple partners (or require partnership working to reach new volunteers), application processes should be lengthened to allow time for partners to feed in to or support with the application

ACE projects which involved multiple partners cited the need for a longer application window to establish new relationships and allow all parties to feed into the application. These partnerships were often key to engaging with new groups of volunteers.

-

Using a range of alternative volunteering models (micro, flexible, digital) can help recruit new volunteers, in particular disabled volunteers, volunteers in education and volunteers who have not volunteered before or have experienced previous barriers to volunteering.

To aid volunteer retention, volunteering opportunities need to be flexible to volunteer needs and allow volunteers to change model at different points in their volunteer journey or if their circumstances change. Grantees highlighted how some volunteers started in micro or flexible roles and then later chose to move to more regular volunteering which ensured long term retention. However, allowing volunteers to change model was not possible for some NHSCT grantees who could not offer micro-opportunities in their projects due to the lengthy nature of NHS recruitment processes.

-

Partnerships with educational establishments (e.g. universities, colleges and schools for students with special educational needs) were key to recruiting young and disabled volunteers

Particular successes included the use of university fairs and job boards to advertise volunteer roles and work experience co-ordinators promoting volunteer opportunities within colleges and schools.

-

Online platforms and apps for volunteers aided retention through communication about future opportunities and made it easier for flexible and micro volunteers to sign up to volunteering shifts

These platforms (such as MyImpact) enabled volunteers to see details of upcoming volunteering opportunities (including specific timing and accessibility information), sign up to volunteer, and cancel sessions if needed.

-

Giving volunteers agency in their role can improve impacts for volunteers and aid retention

This can be achieved through various interventions, including co-production, consulting volunteers about the broader project and ongoing feedback dialogues between volunteers and projects. Volunteers also highlighted how flexible volunteering can be empowering as they have the agency to choose when to volunteer.

-

Clear, regular, and engaging communication to volunteers is key to successful recruitment and retention, particularly for young people and those who experience barriers to volunteering

This includes providing clarity about what volunteering will involve (including activities and timings), and the recruitment process (e.g. making clear that there is no formal interview or written application).

5. Impact evaluation findings

This chapter presents the impact findings based on the contribution analysis. The sub-sections below are structured by contribution statement and evidence collected across all evaluation work strands (CMD, delivery partner focus group, grantee interviews, and volunteer interviews) was used to assess the strength of evidence for each contribution statement. Strength of evidence was evaluated in terms of how many sources of evidence there were for each statement, whether data supported or conflicted with the contribution statements, and how far the different sources of data supported each other. Drawing on this, strength of evidence for each contribution statement was assessed as ‘Strong’, ‘Moderate’, or ‘Weak’:

- Strong: numerous sources of evidence, with high convergence of findings;

- Moderate: moderate amount of evidence, with general convergence but possibly with conflicting results; and

- Weak: limited evidence, with limited convergence of findings.

It should be noted that although insights from ACE projects were gathered through grantee and volunteer interviews, and the CMD, projects are due to finish delivery in March 2024, after the delivery of this evaluation. The final CMD form for ACE grantees will be submitted directly to ACE in March 2024, meaning that CMD data shows an incomplete picture. This meant that less longer-term data on both organisational change and learning and volunteer impacts could be collected and are therefore not factored into the following contribution analysis.

5.1 Impact of the VFF on organisations and the voluntary sector

This section discusses how the VFF funding package impacted grantees and the voluntary sector more broadly. The funding’s impact is assessed in terms of how far the evidence collected supports contribution statement 1 (improving routes for individuals into regular volunteering) and contribution statement 2 (increasing understanding of new models of volunteering within organisations and across the sector).

Summary of evidence to support contribution statement 1

Contribution statement 1

VFF funding programme supported local projects and community organisations to improve routes for individuals into regular volunteering, either through increasing recruitment drives or improving rates of retention.

Overall, there is moderate evidence that the VFF supported local projects and organisations to improve routes for individuals into regular volunteering. At the time of the evaluation concluding in October 2023, CMD data showed that across all projects 15,136 volunteers had been recruited (of which 6,488 were first-time volunteers) with a 16% dropout rate. Grantees and delivery partners discussed learnings gained through the VFF about successful and unsuccessful approaches to recruitment and retention. However, delivery partners also emphasised that the short timeframes for project delivery limited the diversity of grantees they selected and led to the selection of more risk-averse and (potentially) less innovative projects.

| Evidence to support the contribution statement | Strength of evidence |

|---|---|

| At the time of the evaluation concluding in October 2023, CMD data showed that across all projects 15,136 volunteers had been recruited (of which 6,488 were first-time volunteers). Grantees had a mixed experience in terms of how effective their recruitment approaches were. This ranged from projects saying they had received lots of engagement from volunteers, feeling that they would exceed their target, reaching lots of new groups of people (including lots of young people), to others who felt they were on track and others who found the process very challenging. Grantees reported learning about effective ways to increase recruitment of volunteers for their projects. Grantees generally found the following approaches the most effective: face-to-face recruitment; going to spaces where people who face barriers to volunteering frequent; and utilising partners who have relationships with those who face barriers to volunteering. Grantees also discussed the less effective volunteer recruitment approaches, including the use of social media/online recruitment. Some grantees felt it was too early to assess. Volunteer interviews showed that micro and flexible approaches were appealing, particularly for volunteers who had limited previous volunteering experience.. Although delivery partners reported that improvements were made in terms of recruitment, they emphasised that the short timeframes limited the diversity of grantees selected and led to the selection of more risk-averse and (potentially) less innovative projects. | Moderate (CMD, grantee interviews, delivery partner focus groups, volunteer interviews) |

| At the time of the evaluation concluding in October 2023, CMD data showed a low dropout rate of 16% for volunteers. Grantees discussed a range of retention approaches they used. According to grantees, the most successful approaches included: co-designing activities/volunteering opportunities with volunteers; celebratory events and awards to show recognition for the efforts of volunteers; ensuring volunteers were assigned activities/tasks they found relevant and interesting; and, linking up with schools and colleges for work experience. Volunteer interviews showed that projects helped volunteers build confidence which helped retention. Co-production approaches also helped volunteers build confidence as they had more agency within projects and felt like their views and input were valued. Delivery partners reported that improvements were made in terms of retention but emphasised that the short timeframes limited the diversity of grantees selected and led to the selection of more risk-averse and (potentially) less innovative projects. | Moderate (CMD, grantee interviews, delivery partner focus groups, volunteer interviews) |

Contribution statement 2

VFF funding programme increased learning and understanding of new models of volunteering for organisations leading funded projects and a greater understanding of what worked well/less well with improving volunteer recruitment and diversity.

Summary of evidence to support contribution statement 2

Overall there is weak evidence to conclude that the VFF increased learning about and understanding of new models of volunteering and what works well/less well for improving volunteer recruitment and diversity. Although grantees reported using the VFF funding to trial volunteer recruitment and retention approaches, delivery partners felt that opportunities for significant learning within projects were limited due to the short delivery timescales. Many grantees did not use specific terminology around volunteer models and were unable to comment on specific learnings or experiences in comparison to a more regular or existing model. Due to the timing of interviews being early in their delivery phase, ACE grantees also felt it was difficult to comment on learnings from their projects overall. It is therefore possible that evidence for this contribution statement may have been stronger had ACE grantee interviews taken place later, or at the end, of their delivery phase. Delivery partners emphasised that the short timeframes led to the selection of more risk-averse projects which reduced learning about new models.

| Evidence to support the contribution statement | Strength of evidence |

|---|---|