Evaluation of the Personal Support Package

Published 20 July 2021

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

DWP research report no. 1000

A report of research carried out by NatCen on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2021.

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, visit The National Archives or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk.

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk.

First published July 2021.

ISBN 978-1-78659-338-2

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

Introduction

The Personal Support Package (PSP) was introduced from April 2017 for new claimants in the Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) work-related activity group (WRAG) and their equivalents in the Universal Credit (UC) Limited Capability for Work (LCW). Eligibility was later widened to all ESA and UC Health Journey claimants. PSP is funded for 4 years.

The PSP offer consisted of tailored support from Jobcentre Plus (JCP) work coaches, plus a wide range of new initiatives as described in Annex A. This evaluation focussed on the implementation and delivery of the first 18 months of PSP as a whole, and the implementation and delivery of the Health and Work Conversation (HWC) as an initiative integral to the PSP. The evaluation consisted of a large-scale survey of 1,808 claimants who were eligible for PSP plus qualitative research with claimants and JCP staff in four case study areas that were delivering a PSP initiative, Journey to Employment (J2E) and two areas that were not delivering J2E. The HWC research consisted of a survey of 1,006 ESA and UC claimants who had experience of the HWC and was complemented by three qualitative case studies focussed on implementation and delivery of the HWC.

PSP key findings

Claimants health and readiness for work

The most commonly reported health condition among claimants in the PSP survey was a mental health condition (83% of respondents).

The majority of claimants (93%) reported having more than one health condition or disability.

Among claimants currently out of work 60% said they could work in the future if their health improved, 31% said their health ruled out work now and in the future and a small proportion (9%) could work now if the right join or support was available.

Support offered and taken up as part of PSP

Around two-thirds of claimants (65%) recalled being offered some form of general support, such as help with job search, condition management, money management or developing an action plan and 42% of all claimants took up at least one of the options offered.

14% of claimants recalled being offered one of the four external programmes highlighted in the PSP survey (namely the J2E, Work Choice, Work and Health Programme and, Specialist Employability Support), and 7% took up a place on one of these programmes. Claimants took up the support for a variety of reasons including for work-related reasons, to improve their health, to build confidence and not being sure if participation was voluntary.

Similarly, a range of reasons for not taking up support were reported, with the most common barriers being poor physical or mental health, a lack of confidence and the provision not being suitable for claimants’ needs for example, when mental health treatment was prioritised over PSP provision.

Experiences of and outcomes from PSP support

Three quarters (75%) of claimants in the PSP survey who said they received support from a work coach reported that they had found it helpful. The majority of claimants (59%) felt the support provided had been suitable to their needs.

Around two-fifths (42%) of claimants said that their confidence increased as a result of the support and advice they had received from their work coach.

46% of claimants said that the support and advice received had increased their motivation to find work.

Nearly half (44%) of respondents who had taken up support reported participating in work-related activities as a result of the support received, this included 13% who had found some form of work.

Key findings from the Health and Work Conversation (HWC)

The purpose of the HWC is to help individuals identify their health, personal and work goals, draw out their strengths, make realistic plans for the future and build their resilience and motivation. For ESA claimants, four techniques, ‘About me’, ‘My values’, ‘My 4 Steps’ and ‘Action Plans’ are used during a mandatory work focused interview prior to the Work Capability Assessment (WCA). For UC claimants on a health journey these can be used throughout the claimant journey, at work coach’s discretion.

Delivery of the HWC

The format and content of HWC training that staff reported receiving varied significantly in terms of duration and format. More experienced staff did not report gaining new skills but those who were less experienced reported developing in-depth interviewing skills on the training.

The majority of claimants in the HWC survey could recall experiences of one or more of the four HWC techniques, although a substantial minority (41%) did not recall experience of any techniques.

Overall, claimants were comfortable with the topics covered by the HWC, but they were less comfortable discussing their health than they were discussing their qualifications, work or money.

The qualitative research across both ESA and UC case study areas found that work coaches did not always use all four HWC techniques for a variety of reasons, including claimant’s health and time constraints.

Engagement with the HWC

For ESA claimants, the HWC was prior to the WCA which created a challenge for some ESA claimants, who were concerned that if they engaged in work-related discussions, this may prejudice the outcome of their WCA.

Claimants reported that location and surroundings could have a negative impact on engagement.

Both JCP staff and claimants perceived that the HWC and accompanying techniques were less effective for certain claimant groups, particularly those closest to and furthest from the labour market.

Where no HWC follow-up took place, almost half of all claimants felt it would have been useful.

Overall, claimants participating in the HWC survey felt comfortable with the HWC, with UC claimants highlighting that their on-going relationship with their work coach provided a strong framework for building relationships.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank colleagues at the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) who managed and supported this evaluation; Sophie Gerrard, Susanna Greenwood, Will McKinnon, Jo O’Shea, Sarah Kenny, Catherine Flynn and Janet Allaker.

We would also like to thank colleagues from Jobcentre Plus offices and external providers who gave up their time to participate in an interview. We are also grateful for ESA and UC claimants who took the time to participate in this research.

Finally, we would like to thank colleagues at the National Centre for Social Research, particularly to Ionela Bulceag, Sal Mohammed and Emma Sayers who provided support with the qualitative fieldwork.

The authors

This report was authored by researchers at the National Centre for Social Research:

Amelia Benson, Senior Researcher

Tim Buchanan, Research Director

Joe Crowley, Senior Researcher

Malen Davies, Research Director

Anna Marcinkiewicz, Senior Researcher

Katariina Rantanen, Researcher

Bethany Thompson, Research Assistant

Karen Windle, Director of the Health and Social Care team

Glossary of terms

Access to Work – a programme that helps disabled people start or stay in work. It provides practical and financial support to those who have a disability or a long term physical or mental health condition.

Access to Work Mental Health Support Service (AtW MHSS) – a programme that provided six-month support for claimants with a potential start date with an employer, but who were unsure of their ability to sustain employment without support.

Claimant - Throughout this report, the term ‘claimant’ is used to describe those benefit recipients who were eligible for support under the PSP.

Claimant Commitment – an agreement formed with Universal Credit claimants, comprising their job search or other requirements.

Community Partner (CP) – a specialist role employed by Jobcentre Plus for their expertise and local knowledge of disability issues. Worked with work coaches, local third sector organisations and employers to build relationships and strengthen their understanding of disabilities. The role ceased on 31st March 2019.

Disability Employment Adviser (DEA) – specialist Jobcentre Plus staff who provide support and advice to JCP work coaches and other staff to support their work with claimants who have a health condition or disability.

District Provision Tool – a locally updated intranet site for Jobcentre Plus staff, with information on local support and initiatives suitable for DWP claimants.

Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) – a type of unemployment benefit offering financial support to people who are not in work due to a health condition or disability.

Personal Support Package (PSP) – a suite of programmes and initiatives introduced in 2017 to support people who are not in work due to a health condition or disability move closer to employment.

Health and Work Conversation (HWC) – a mandatory work-focused interview for ESA claimants which is scheduled at the beginning of their claim and held prior to their Work Capability Assessment. For UC claimants, HWC techniques can be spread out across several appointments and work coaches can use their discretion to use the most appropriate elements.

Jobcentre Plus work coach – frontline DWP staff based in Job Centres who deliver personalised support and interventions across all benefits, coaching and supporting claimants into work by challenging, motivating, providing personalised advice and applying knowledge of local labour markets.

Journey to Employment (J2E) – Peer-led job clubs delivered by Disabled Peoples’ User Led Organisations / voluntary organisations.

Limited Capability for Work group (LCW) – claimants are placed in the LCW group after the WCA, when the claimant’s ability to work is reduced by their physical or mental health condition and it is not reasonable to require them to work.

Limited Capability for Work Related Activity (LCWRA) – claimants are placed in the LCWRA group after the WCA, when their ability to work is so limited by their physical or mental health condition that they are not required to work or to undertake any work-related activity.

Permitted Work – This is paid employment that ESA claimants can undertake if they work less than 16 hours per week and earn up to a maximum of £125.50 per week.

Provider – an organisation external to the Jobcentre Plus, providing a contracted employment support programme or service for claimants.

Single Point of Contact (SPOC) – a member of Jobcentre Plus staff selected to manage the relationship with providers of Personal Support Package initiatives and promote their provision within the Jobcentre Plus.

Small Employer Adviser (SEA) – a specialist that works with local small employers to identify opportunities for claimants with health conditions or disabilities and match people to jobs under the Small Employer Offer. The role ceased on 31st March 2019.

Small Employer Offer (SEO) – a PSP initiative where Small Employer Advisers work with local small employers to identify opportunities and match people to jobs.

Specialist Employability Support (SES) – a programme delivered by a range of provider organisations, to support people with a disability or health condition and complex support needs.

Support Group – people claiming ESA and UC are placed into different groups depending on the extent to which their illness or disability affects their ability to work. Those claiming ESA in the Support Group and those claiming UC in the Limited Capability for Work or Work-Related Activity group are considered to have such severe health conditions that there is no current prospect of them being able to undertake work or work-related activities.

Universal Credit (UC) – a DWP monthly benefit for those out of work or on a low income, replacing six previous benefits and tax credits including Jobseeker’s Allowance, Employment and Support Allowance, Income Support, Child Tax Credit, Working Tax Credit and Housing Benefit.

Universal Credit health journey – a group of people who have a health condition and/or disability which restricts their ability to work and claim Universal Credit. Claimants have either provided acceptable medical evidence prior to the Work Capability Assessment or been found to have Limited Capability to Work or Limited Capability for Work Related Activity after a Work Capability Assessment.

Work and Health Programme (WHP) – a programme mostly delivered by external providers, providing personal support to improve the claimant’s skills, manage their health condition and match claimants to jobs.

Work Capability Assessment (WCA) – an assessment that measures the extent to which illness or disability affects one’s ability to work, undergone by all ESA claimants and those UC claimants with a disability or health condition that prevents or limits their ability to find work.

Work Choice (WC) – a specialist disability employment programme delivered by a range of provider organisations, that offered work entry support and up to two years in-work support for people with disabilities. Referrals to Work Choice stopped in 2017.

Work Coach Team Leader – a member of Jobcentre Plus staff who manages and supports a team of work coaches.

Work-Related Activity Group (WRAG) – people claiming ESA are placed into two groups depending on the extent to which their illness or disability affects their ability to work. The work-related activity group are required to have regular interviews with an work coach and undertake work-related activities.

List of abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Explanation |

|---|---|

| CP | Community Partner |

| EA | Employer Adviser |

| DEA | Disability Employment Adviser |

| DWP | Department for Work and Pensions |

| ESA | Employment and Support Allowance |

| PSP | Personalised support package |

| HWC | Health and Work Conversation |

| J2E | Journey to Employment |

| JCP | Jobcentre Plus |

| JSA | Jobseeker’s Allowance |

| SEA | Small Employer Adviser |

| SEO | Small Employer Offer |

| SES | Specialist Employability Support |

| UC | Universal Credit |

| WC | Work Choice |

| WCA | Work Capability Assessment |

| WHP | Work and Health Programme |

| WRAG | Work-Related Activity Group |

Summary

Introduction

The Personal Support Package (PSP) was introduced from April 2017 for new claimants in the Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) Work Related Activity Group (WRAG) and their equivalents in the Universal Credit (UC) Limited Capability for Work Group (LCW). Eligibility was later widened to all ESA and UC Health journey claimants.

The PSP offers an enhanced menu of employment support options designed to be tailored to people’s individual needs and move ESA and Universal Credit (UC) claimants on a health journey closer to work. PSP is funded for four years from April 2017.

The PSP offer for year 1 (April 2017- March 2018) consisted of tailored support from JCP work coaches, plus a wide range of new and existing initiatives aimed at both work coaches and claimants (as described in Annex A). Some support was scheduled to run throughout the 4-year period, while other support was only planned to run between 12 to 18 months.

Evaluation approach

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) commissioned the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) to evaluate the implementation and delivery of the first 18 months of PSP as a whole, and the implementation and delivery of the Health and Work Conversation (HWC) as an initiative integral to the PSP.

The evaluation of the PSP aimed to explore:

- Jobcentre Plus (JCP) staff views and experience of the implementation and delivery of the PSP

- eligible claimants’ reasons for taking up or not taking up support offered as part of the PSP

- claimants’ perceptions of the support offered by the PSP

- early outcomes of PSP support

The PSP research consisted of a survey with ESA and UC claimants who were eligible for the PSP (a total of 1,808 claimants participated), plus four qualitative case studies focused on the implementation and delivery of the Journey to Employment (J2E) programme, and an additional two case studies undertaken in areas which did not offer J2E. The latter focused on the implementation and delivery of all PSP strands.

The evaluation of the Health and Work Conversation aimed to explore:

- JCP staff and claimants’ experiences of the implementation and delivery of the HWC

- whether effective goals were set and followed up as part of the HWC

- any potential improvements to the HWC

The HWC research consisted of a survey of 1,006 ESA and UC claimants who had experience of the HWC and was complemented by three qualitative case studies with staff and claimants, focussed on implementation and delivery of the HWC.

PSP key findings

Claimants health, readiness for and attitudes towards work

The most commonly reported health condition among claimants in the PSP survey was a mental health condition (83%).

The majority of claimants (93%) reported having more than one health condition or disability.

Three-quarters of claimants (75%) reported that their health condition or disability caused them at least moderate problems when carrying out daily activities.

The majority of claimants in the PSP survey (93%) perceived their health as a barrier to returning to work.

Among claimants currently out of work 60% said they could work in the future if their health improved, 31% said their health ruled out work now and in the future and a small proportion (9%) could work now if the right job or support was available.

Staff awareness and understanding of the PSP

Staff awareness of the aims of the PSP and the initiatives under it was varied.

Some staff were able to identify all elements that constitute the PSP, but it was more common for staff to know of only some of the initiatives available to claimants and be unaware that existing provision had been altered or expanded to be incorporated into the PSP.

This may in part be a consequence of the staggered rollout of some elements of PSP and the fact that some elements were only available in selected districts.

Type of support offered to claimants as part of PSP

Staff referred and signposted claimants to four main types of provision: Pre-employment support / training; In-work support; Health and Disability- related services and other general provision.

Around two-thirds of claimants (65%) identified being offered some form of general support, such as activities that supported them with their job search, managing their health, making lifestyle changes, or developing an action plan.

14% recalled being offered one of the four external programmes highlighted in the PSP survey.

Decision-making and referrals to PSP and general provision

A range of factors influenced whether claimants were offered support, the most significant of which were severity of their health condition and proximity to the labour market.

Similarly, a range of factors influenced which provision work coaches referred claimants to. These included staff awareness of provision, promotion of provision by other staff, the work coach’s relationship with particular providers and feedback of provision from previous referrals.

Perceived likelihood of acceptance onto a programme and staff workload also played a part in determining referral pathways.

Support taken-up

Among all claimants responding to the PSP survey, 65% recalled being offered general support by their work coach, and 42% of all claimants reported taking up at least one of the support options offered.

This support included external provision, advice on managing their health condition or disability, money management, applying for jobs, making general lifestyle changes, accessing locally available support for their health condition, and developing an action plan.

In terms of the external PSP programmes highlighted in the survey, 7% of claimants said they took up at least one of these four initiatives (J2E, Work and Health Programme (WHP), Specialist Employability Support (SES) and Work Choice (WC)). Take-up was highest for J2E.

Reasons for taking up provision included wanting support with job applications, health-related issues, and confidence building.

From the qualitative analysis, there were three interrelated factors that influenced whether a claimant took up the offer of support: claimant motivation, the voluntary nature of participation and encouragement from work coaches and providers.

Barriers to taking-up support

A range of reasons for not taking up support were reported, the most common barriers being poor physical or mental health, and lack of confidence/anxiety. In the case studies it was also reported that support was not taken up because the provision was not suitable for claimants’ health needs, for example, when mental health treatment was prioritised over PSP provision.

For some claimants participating in the case studies, there was concern about the negative financial implications of moving into work. Negative perceptions of employment support also prevented participation.

Experiences of support

Experiences of support were largely positive. Three quarters (75%) of claimants in the PSP survey who said they received support from a work coach reported that they had found it helpful. The majority of claimants (59%) felt the support provided had been suitable to their needs.

Those who said that their health ruled out work now and in the future were more likely (60%) to report that support they received was not suited to their needs compared to those who could return to work straight away in the right job (45%).

The qualitative case studies found that views on the J2E programme among those who engaged in part or in all of the programme were particularly positive. On the whole, J2E participants found the peer support valuable, and both claimants and staff viewed J2E providers positively.

However, a peer support setting was not always appropriate for people with social anxiety.

Outcomes from PSP support

Around two-fifths (42%) of claimants who had accessed support said that their confidence increased as a result of the support and advice they had received from their work coach.

46% of claimants said that the support and advice received had increased their motivation to find work.

Qualitative interviews with claimants indicate that the drivers of improvement were increased confidence in managing their own health condition, improvements in self-esteem, and confidence in looking for work.

Nearly half (44%) of claimants who had taken up support reported participating in work-related activities as a result of the support received. This included volunteering or education and training.

Among those who took up support, 12% found some form of work. 8% had found permitted work, 3% had found part-time work, and 3% full-time work.

Those who reported no increase in confidence or motivation to find work as a result of advice and support from their work coach gave the following reasons for it: health barriers, the fact that their confidence/motivation did not depend on support from their work coach, and a lack of support from their work coach.

Key findings from the Health and Work Conversation (HWC)

The purpose of the HWC is to help individuals to identify their health, personal and work goals, draw out their strengths, make realistic plans for the future, and build their resilience and motivation.

Training staff to conduct the HWC

The format and content of HWC training that staff reported receiving varied significantly. The duration of the training ranged from one hour to two days, and it was delivered in a range of formats including face-to-face training, e-learning, and as part of the wider UC work coach training programme.

Staff who undertook the longer training reported HWC training gave them a good understanding of the purpose and structure of the HWC. Less experienced staff valued learning new skills and improving their in-depth interviewing skills.

Delivery of the HWC

The majority of claimants recalled discussing their health / ability to work with work coaches, even if they could not remember the four individual techniques used. Many claimants in the HWC survey could recall taking part in one or more of the four HWC techniques (“About Me”, “My Values”, “My 4 Steps”, “Action Plan”), although a substantial minority (41%) did not recall using any techniques.

Recall of individual components of the HWC varied by both claimant characteristics and by claimant journey.

Overall, claimants were comfortable with the topics covered by the HWC. However, it is important to note that, in general, they were less comfortable discussing their health than other topics. This may in part be a consequence of the use of open plan settings for the HWC[footnote 1].

The qualitative ESA and UC case studies found that work coaches did not always use all four HWC techniques.

Factors affecting engagement with the HWC

A range of operational constraints and personal characteristics affected engagement in the HWC.

For ESA claimants, the HWC was prior to the Work Capability Assessment (WCA). The timing created a challenge for ESA claimants, who were concerned that if they engaged in work-related discussions, this may prejudice the outcome of their WCA.

Claimants reported that location and surroundings had a negative impact on engagement, with open plan offices limiting the extent to which they could discuss personal or private issues.

Both JCP staff and claimants perceived that the HWC and accompanying techniques were less effective for certain claimant groups, particularly those closest to and furthest from the labour market.

Goal setting and follow-up

Around a third of claimants (30%) recalled agreeing actions or goals in their meetings with work coaches.

Claimants on ESA were most likely to set physical and mental health related goals, whilst those on UC were more likely to set work-related goals. This could be connected to the timing of the HWC, which can occur much later in UC.

Work coaches felt that the policy intention of claimants setting their own goals was essential to ensure ownership and follow through with the goals that were set.

Where no HWC follow-up took place, almost half of all claimants felt it would have been useful (48% of ESA claimants and 49% of UC).

Conclusions of PSP and HWC

PSP

Overall, the claimant perspective on support and advice received from their work coach was positive, with three quarters of claimants in the PSP survey finding the support provided either ‘very’ or ‘fairly’ helpful.

Reported outcomes were more mixed, with two fifths of claimants who took up support saying that the support and advice they had been offered by their work coach had increased their confidence and motivation to move closer to work. Similarly, direct work-related outcomes were mixed. Among those who took up some form of support, 44% said they engaged in work-related activity as a result of the support, such as volunteering, training, education or employment.

Running throughout both the quantitative and qualitative findings, there is a clear thread about the role played by type and severity of health condition or disability and the wider factors influencing distance from the labour market (such as age and education) in determining which claimants are likely to benefit most from support and advice offered by their work coach.

The findings indicate that tailoring and targeting of support is important to ensure claimants’ main barriers to work are addressed and the support meets their needs. Those with severe health conditions are likely to benefit from help targeted at supporting them to overcome their health and confidence related barriers, whereas those closer to the labour market benefit, with less severe conditions, will continue to benefit from work-focused support.

HWC

A significant minority of claimants did not recall taking part in any HWC techniques. While this will undoubtedly be driven by the challenge of recognising and recalling the specific initiatives in some instances, it is worth reflecting that the claimants least likely to recall the techniques were those who were furthest from the labour market. It is with these claimants that staff reported tailoring or choosing not to use HWC techniques. Building rapport and having adequate time and an appropriate setting to use HWC techniques were central to staff delivering the HWC as it was designed.

HWC techniques were felt to be less effective for those who were furthest from the labour market. It was also felt to be less useful for those closest to the labour market, with a job to return to. Similarly, it was felt to be less useful for older people close to retirement or those who had complex needs, such as drug and alcohol dependency.

However, overall, claimants in the HWC survey felt comfortable with the HWC, with UC claimants for example, highlighting that their on-going relationship with their work coach provided a strong framework for building relationships. Half of claimants in the HWC survey, who did not have a follow-up, would have liked one.

1. Introduction

1.1 Policy context

In 2017, the Government made a commitment to supporting one million disabled people into work over the next 10 years and working to ensure that everybody is given the opportunity to reach their potential. The 2017 Command Paper ‘Improving Lives: Work, Health and Disability’ outlined a range of actions to achieve this goal.

This included the introduction of an enhanced offer of employment support for Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) or Universal Credit (UC) claimants on a health journey, called the Personal Support Package (PSP). The PSP encompasses a range of employment support which can be tailored to people’s individual needs with the overall aim of moving people closer to the labour market or into work.

The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) commissioned the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) to evaluate the implementation and delivery of the PSP as a whole, and the implementation and delivery of the Health and Work Conversation (HWC), an initiative integral to PSP.

1.2 Aims of the evaluation

The overarching aims of the PSP evaluation were to explore:

- Jobcentre Plus (JCP) staff views and experiences of the implementation and delivery of the PSP

- PSP eligible claimants’ reasons for taking up/not taking up support

- perceptions of support among PSP eligible claimants who took it up

- early outcomes of PSP support

The overarching aims of the HWC evaluation were to explore:

- JCP staff and claimants’ experiences of the implementation and delivery of the HWC

- whether claimant goals were set and followed-up after the HWC

- any further improvements to the HWC needed

Alongside NatCen’s evaluation, DWP has commissioned independent evaluations of the Small Employer Offer (SEO) and the Work and Health Programme (WHP); both of which are elements of the PSP.

1.3 Overview of the Personal Support Package

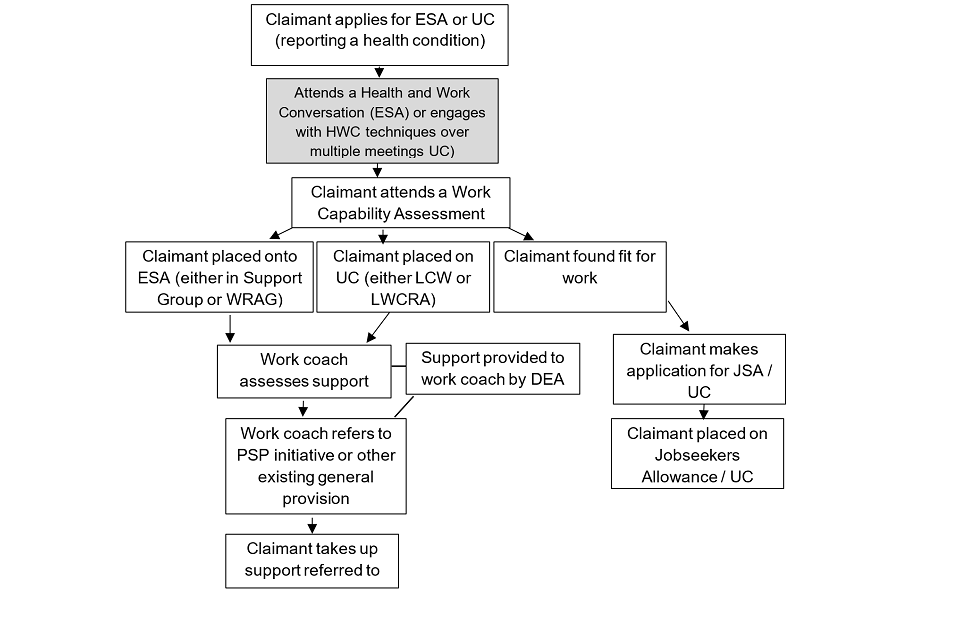

The PSP includes a range of measures and initiatives that aim to support ESA or UC claimants on a health journey. The individual components of PSP are outlined below, and the anticipated claimant journey is set out in Figure 1.1. The PSP package is scheduled to cover four years from April 2017. This research focuses on the package delivered within the first year to 18 months from April 2017 to November 2018.

1.3.1 PSP initiatives

During the first year of the PSP the package covered tailored support delivered by a JCP work coach plus a number of additional strands listed below.

New Initiatives

1. Small Employer Offer (SEO)

2. Journey to Employment (J2E)

3. Mental Health Training for work coaches

4. Community Partners - new JCP job roles

Extra places on existing provision

5. Work Choice

6. Work and Health Programme (WHP)

7. Specialist Employability Support (SES)

8. Access to Work Mental Health Support Service (MHSS)

Proofs of Concept (small scale tests in selected areas)

9. JCP led Personalised Support

10. Specialist Advice

11. Local Supported Employment

12. Young Persons Supported Work Experience

13. Work Related Activity Group (WRAG) intensive support

Other

14. Extra DEAs to support work coaches and other staff

15. Health and Work Conversation

Details of each initiative are provided in Annex A.

1.3.2 Health and Work Conversation (HWC)

The Health and Work Conversation (HWC) was launched in 2017 as part of the PSP. It is a mandatory work-focused interview for ESA claimants that is scheduled at the beginning of the claim and held prior to their Work Capability Assessment (WCA). For UC claimants, the HWC is not delivered in a single mandatory appointment, rather work coaches are encouraged to use elements of the HWC in their regular meetings with claimants on a health journey.

The purpose of the HWC is to help individuals to identify their health and work goals, draw out their strengths, make realistic plans and build resilience and motivation. The HWC comprises of 4 techniques:

- “About me”: A form that the claimant completes prior to or at the start of the HWC. It includes questions on claimant’s interests and skills, the effect of health on the claimant’s life, previous employment, and self-reported support needs

- “My Values”: An optional exercise used to encourage claimants to become more open to challenges

- “My 4 Steps”: A 4-step process where the claimant identifies a specific goal they would wish to achieve (for example, undertaking voluntary work), details any internal obstacles or barriers and sets out a plan to overcome those obstacles

- “Action Plan”: The purpose of the action plan is to support claimants to overcome external obstacles (for example, housing or debt issues). The outcomes of this exercise are measurable actions. For example, the claimant might find out more about a particular area online, or the work coach might refer the individual to further support across the DWP. For UC claimants, actions are recorded in the Claimant Commitment which can include both voluntary and agreed mandatory actions

Figure 1.1 Claimant journey

1.4 Methods

A mixed method approach was employed to evaluate both the PSP as a whole and the HWC in particular.

The quantitative strand of the research consisted of two large-scale national surveys of claimants, one focused on the PSP and one on the HWC.

The qualitative research applied a case study approach for both PSP and HWC. For the evaluation of the PSP, this involved in-depth interviews with JCP staff, ESA and UC claimants who had been offered and/or taken up one of the four PSP strands highlighted in the research (J2E, WHP, SES and WC), and externally contracted providers of employment support. The HWC case studies involved observations of HWCs, interviews with JCP staff, and ESA and UC claimants on a health journey who had experience of HWC techniques.

1.4.1 Quantitative methods

1.4.2 PSP survey

A quantitative telephone survey of 20 minutes was undertaken with ESA and UC claimants who were eligible for the PSP across England, Scotland and Wales. The survey took place between August and November 2018. In total, 1,808 individuals took part in the survey.

Sample and response rates

The sample issued for the PSP survey included 24,141 claimants. Of the initial sample 2,590 did not have valid phone numbers and were excluded from the final sample size used to calculate response rates. A further 738 were screened out because they reported that they had not attended the Job Centre. The sample issued for the PSP survey by DWP included 20,813 claimants and the survey achieved a response rate of 9%. An important requirement for this study was to ensure inclusion of those claimants who chose to access one of the four externally provided strands of PSP that were highlighted in the research (J2E, WHP, SES and WC) as well as those who did not take up any of these options.

Questionnaire

A total of eight cognitive interviews were carried out on a number of the survey questions prior to finalising the questionnaire. Cognitive interviews aim to investigate how people understand specific questions and how they recall information.

The full questionnaire and the cognitive interview report can be found in the technical report.

Weighting

Findings were weighted to the profile of all those eligible for PSP support at the start of the survey by gender, age group, region, and broad disability type (for example, mental health condition and physical health condition). Full details can be found in the technical report.

1.4.3 HWC survey

A quantitative telephone survey of 20 minutes was undertaken with ESA and UC claimants on a health journey who were eligible for HWC across England, Scotland and Wales. The survey took place between November and December 2018. In total, 1,006 individuals took part in the survey; 500 UC claimants on the health journey and 506 ESA claimants.

Sample and response rates

The sample issued for the HWC survey by DWP included 1,091 ESA and 4,663 UC claimants and achieved response rates of 46% and 11% respectively. DWP provided 2,228 ESA and 13,144 UC contacts. Two screener questions were introduced to ensure that claimants attended meetings at the Job Centre since the start of their ESA/UC claim and that they had a health condition; this screened out 137 ESA and 619 UC claimants. The difference in response rate may be explained by the different time points from which the samples were drawn. The ESA sample was drawn on a weekly basis between 22th October and 12th November 2018 to capture claimants who had undergone their HWC within the last four weeks. This ‘immediacy’ may have encouraged a greater response. In contrast, the UC sample was drawn at a single time point (22nd October 2018). This resulted in the inclusion of those UC claimants who had been claiming this benefit for a range of time periods, and who might not have had their HWC recently.

Weighting

Findings were weighted to the profile of all those eligible for HWC at the time of the survey, by age/sex and region. Full details can be found in the technical report.

Questionnaire

Pilot interviews were conducted with 30 claimants; 16 with UC claimants and 14 with ESA claimants. These telephone interviews took an average of 20 minutes. The pilot questionnaire included the following sections: participant demographic characteristics, experience of the HWC, setting goals, follow-up meetings, and perceived outcomes of the HWC. Following the pilot, a series of changes were made to the mainstage questionnaire. The final questionnaire can be found in the technical report.

1.4.4 Interpreting quantitative findings

The quantitative findings are based on frequencies and cross-tabulations of questions included in both surveys. This report explores how (and if) experiences and views of claimants differ by a range of socio-demographic factors including age, gender and education, as well as variables collected as part of both surveys on self-reported health status and attitudes towards work. All percentages cited in this report are based on the weighted data and are rounded to the nearest whole number. All differences described in the text (between different groups of people) are statistically significant at the 95% level or above. This means that we can be 95% sure that any difference we find in the survey data represents a difference in the total ESA /UC benefit population. Further details of significance testing and analysis are included in the technical report. All figures presented in the report include valid percentages excluding ‘don’t know’ responses.

Analysis on the impact of support covers all those who had received support from their work coach, as well as support from the four PSP strands highlighted in this research (J2E, WHP, SES and WC). The WHP, whilst part of the PSP, is a large-scale intervention that is subject to a separate evaluation.

1.4.5 Qualitative methodology

PSP case studies

Six case studies were conducted between May 2018 and September 2018. Four case studies focused on the implementation and delivery of the J2E initiative. The remaining two explored the wider implementation and delivery of the PSP in areas where J2E was not available. Case studies were selected to ensure the sample included JCP Districts in both rural and urban areas and there was a mix of areas where UC been rolled out for new claimants and places where this was yet to happen.

Within each case study, telephone and face-to-face group interviews were conducted with work coaches, Work Coach Team Leaders and Disability Employment Advisors (DEA). Telephone interviews were carried out with Community Partners, J2E providers and Small Employer Advisors (SEA), whilst telephone or face-to-face interviews were held with claimants who had either taken up a place on one of the four external PSP strands highlighted in the research or had been offered but declined this support. A total of 74 interviews were conducted.

HWC case studies

Three case studies were conducted between June and September 2018. Case studies were selected to ensure the sample included a mix of areas where UC been rolled out for new claimants and places where this was yet to happen. Additionally, a mix of rural and urban locations were included to take account of differences driven by local labour market conditions.

Each case study included one-day observation of HWC appointments, telephone interviews with work coaches, Work Coach Team Leaders and DEAs and a mix of telephone and face-to-face interviews with claimants who had some experience of the HWC techniques. In total 52 interviews were conducted.

1.4.6 Interpreting qualitative findings

The reporting of qualitative findings deliberately avoids using numerical language, as qualitative methods are designed to explore issues in depth rather than generate data which can be analysed numerically. The qualitative samples have been purposively selected to ensure the achieved sample has range and diversity. This approach to sampling is a hallmark of quality in qualitative research.

Verbatim quotes are used throughout the report to illuminate findings. Quotes from JCP staff and external providers are labelled to indicate job role, whether UC was live in the case study areas and whether J2E was available. Quotes from claimants are labelled to indicate the benefit type and whether J2E was available in the case study area.

1.5 Limitations

The following limitation should be considered when reading these evaluation findings; the PSP and HWC surveys and qualitative case studies relied upon claimants’ recall of their meetings with the work coach, support offered or taken-up. Recall of HWC techniques may have been difficult owing to claimants attending multiple appointments with their work coach, specifically in the UC context.

1.6 Report outline

This report presents the findings from the qualitative case studies (i.e. J2E, the wider PSP initiatives and the HWC) and quantitative claimant surveys (PSP and HWC).

Chapter Two draws on findings from the PSP survey of claimants and describes the claimants’ attitudes to and feelings about work.

Chapter Three uses data from the PSP case studies and claimant survey to explore the types of support claimants were offered.

Chapter Four draws on the same data and describes the types of support taken-up. This chapter also outlines the barriers and facilitators to take-up of support.

Chapter Five presents findings from the HWC case studies and claimant survey.

Chapter Six draws on all the data collected from across the case studies and both surveys identifying the perceived claimant outcomes.

Finally, Chapter Seven provides suggested improvements to the PSP and HWC.

2. PSP Claimant Survey – Impact of health on attitudes to work

This chapter describes claimants’ health alongside their attitudes towards paid work now and in the future, drawing out differences within the claimant group.

Although this evaluation focuses on the take-up and outcomes achieved as a result of engagement with PSP initiatives, both the PSP and HWC surveys also explored claimants’ attitudes to health and work. This was important as attitudes to health and work for claimants with a health condition or disability are likely to have implications on the level of take-up of support offered, as well as the types of outcomes claimants might achieve.

2.1 Claimants’ health

All claimants who responded to the PSP survey had a health condition or disability and many had multiple complex health needs. The majority of claimants reported that their condition affected them in at least two ways (93%). Over eight out of ten (83%) of claimants reported that their condition or illness affected their mental health. The most commonly reported condition was mental health, reported by 83% of claimants (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1 Whether claimants’ condition or illness affects them in any of the following areas

| Condition or illness | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Mental health | 83% |

| Learning or concentrating | 64% |

| Stamina, fatigue or breathing | 55% |

| Mobility | 56% |

| Memory | 53% |

| Dexterity | 42% |

| Social or behavioural | 40% |

| Vision | 22% |

| Hearing | 15% |

| Other | 7% |

Base: All respondents (1808). Note: PSP claimants could select more than one answer option at this question so the percentages in the figure do not total one hundred.

When claimants were asked to choose the main way in which their health condition affected them (for example, vision, memory, mental health), two main issues emerged. Mental health was the most commonly reported way in which participants’ health affected them, identified by 41% of people, followed by mobility related issues, reported by 18%. No other main health condition was selected by more than 4% of claimants. A further fifth (22%) of claimants responded to say that the different areas they were affected in were equally important and they could not choose between them.

There were differences by age, with younger people more likely to report mental health as their main health condition (48% of 16 to 24-year-olds compared with 28% of 55 to 78-year olds). In relation to mobility issues, 28% of 55 to 78-year-olds reported these as their main health condition compared with 11% of 16 to 24-year olds. To identify the severity of people’s health conditions, claimants were asked how much their health condition or disability limited their ability to carry out everyday activities. 15% said that they had no or slight problems carrying out everyday activities. Around a third (31%) described their problems carrying out everyday activities as moderate, with around a quarter (28%) identifying these as severe. 16% of claimants said they were unable to carry out their everyday activities (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 How much health condition/disability limits everyday activities

| Level of problem | Percentage |

|---|---|

| No problems carrying out everyday activities | 5% |

| Slight problems | 10% |

| Moderate problems | 31% |

| Severe problems | 28% |

| Unable to carry out everyday activities | 16% |

| Differs too much to say | 10% |

Base: All respondents (1798)

2.2 Readiness to work

In the PSP survey 91% of claimants were not in paid employment. Of these, over half were out of work and had been claiming ESA or UC for more than two years. Those who were not in paid employment were asked what, in their view was, preventing them from finding work. Claimants were offered a number of barriers to choose from and the majority (93%) reported that their health condition or disability was a barrier to finding work. Although a fifth of claimants (21%) reported more than one barrier to finding work, health was the most commonly reported reason that was stopping claimants from working, followed by a lack of confidence in applying for jobs (8%).

Figure 2.3: Duration of current benefit claim

| Duration | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Less than 3 months | 3% |

| 3 months or more but less than 6 months | 3% |

| 6 months or more but less than a year | 11% |

| Between 1 and 2 years | 29% |

| More than 2 years | 53% |

Base: all those claiming benefits at the time of the survey (1645)

Among claimants in the PSP survey who were not in work, nearly a third (31%) reported that their health condition ruled out work now and in the future. A further 60% felt that work might be a possibility in the future if their health improved. 9% reported they could seek paid work now, if the right job and/or support was available (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4: Readiness to work

| Readiness to work | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Health rules out work now and in the future | 31% |

| Might be able to work in the future if health improves | 60% |

| Could work now if right job/support was available | 9% |

Base: All respondents currently not in work (1532)

Claimants in the PSP survey who were not in paid employment were also asked to what extent they would like to find paid employment in the future (either full or part-time). A majority of these claimants (64%) said they would like to work to a great or some extent. Under a fifth (19%) said that they would not like to work at all (Figure 2.5).

Figure 2.5 Extent to which claimants would like to work in the future

| Extent | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Not at all | 19% |

| A little | 17% |

| To some extent | 25% |

| To a great extent | 39% |

Base: All respondents currently not in work (1482)

When claimants in the PSP survey who were not currently in work were asked when they might be ready to undertake paid work, a third (33%) estimated that they may be ready within the next twelve months. A further third envisaged that they would be able to work in the more distant future (19% in between one to two years’ time and 22% in 2 years or more). A quarter (26%) felt they would never be able to work (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6 When in the future claimants will be able to undertake paid work

| When | Percentage |

|---|---|

| In the next year | 33% |

| In between 1 and 2 years | 19% |

| Later than 2 years | 22% |

| Never | 26% |

Base: All respondents currently not in work (1224)

2.3 Differences in attitudes to work

Attitudes to work amongst claimants in the PSP survey, who were not in paid employment at the time of the survey, differed by the severity of their health condition. Nearly half (47%) of those who were unable to carry out every day activities said they could not work (now or in the future) owing to their health status, compared with 13% of those who had no problems carrying out everyday activities. This measure of how severe people’s health condition is based on a survey question how much people’s health problems affect their ability to perform everyday activities. Answer options ranged from having no problems, to slight, moderate, or severe problems, to being unable to carry them out at all. Where severity of health condition is referred to elsewhere in the report, it is this question being to measure it.

Differences in attitudes to work were also observed in relation to the type of health condition reported by claimants in the survey. Those with mobility-related health conditions were more likely to say that this ruled out work now or in the future, compared with those living with mental health conditions (47% compared with 20%) (Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7 Attitudes towards work, by main health condition

| Attitude | Mental health | Mobility |

|---|---|---|

| Health rules out work, now and in the future | 20% | 47% |

| Currently unable to work, might be able to in the future if health improves | 70% | 49% |

| Could work now if right job/support was available | 9% | 4% |

Base: All respondents currently not in work who reported mobility or mental health as their main health condition (mental health: 589; mobility: 294)

Claimants in the PSP survey attitudes to work also differed depending on their age, education, and length of benefit claim. Those groups more likely to identify that their health condition ruled out work as an option, now or in the future, included:

- those 55 and over: 47% of those aged 55 and over compared to 12% of 16-24-year olds

- those with no qualifications: 39% of those with no qualifications compared with 25% with A levels or above

- those claiming benefits for more than 2 years: 34% compared with 26% of those claiming for less than 6 months

2.4 Summary

The most commonly reported health condition or disability were mental health conditions, reported by 83% of claimants. The vast majority of claimants also had more than one health condition, with 93% of claimants reporting 2 or more.

Health was the main barrier identified as affecting claimants’ ability to enter into paid employment, reported by 93% of claimants, with the next most commonly reported barrier (a lack of confidence in applying for jobs), reported by only 8%.

The majority of claimants in the PSP survey (60%) reported that they might be able to work in the future if their health improved, with 9% saying they could work now if the right job/support was available.

Around a third of claimants (31%) reported that their health status ruled out work as an option now or in the future. This view was more prevalent among claimants whose health conditions limited their daily activities; those with mobility-related health conditions; in the older age groups (over 55); among those with no qualifications; and those who reported claiming benefits for more than 2 years.

3. Support offered under the Personal Support Package

This chapter explores staff awareness and understanding of the PSP and the processes for offering and referring ESA and UC claimants to support, including PSP initiatives. This chapter also covers staff views of factors that affected support offered to claimants.

3.1 Staff awareness and understanding of the PSP

3.1.1 Awareness of the PSP aims and initiatives

Awareness of the PSP aims differed among staff, with newer colleagues being less familiar with the PSP programme compared to more established colleagues.

Staff awareness of specific PSP initiatives also varied widely. There were examples of work coaches and Work Coach Team Leaders who were able to identify all initiatives offered as part of the PSP (Initiatives are described in further detail in Annex A). It was more common for staff to be able to identify only some of the initiatives within the PSP. For example, there were staff who did not realise that as part of the introduction of the PSP, extra spaces or support had been ring-fenced on the Work and Health Programme (WHP) or Access to Work for Mental Health Support Services. There was also limited knowledge that additional spaces had been funded on Work Choice (WC).

The range in levels of awareness is likely to be due to three factors. Firstly, some of the PSP strands were only available in selected areas and others were introduced via a staggered roll-out. Secondly, staff may have been aware of some strands under terms different to the descriptions used in the research interviews. Finally, workload pressures may have meant that staff had limited time to absorb all the PSP information circulated, for example, the fact that extra places on some existing programmes were now badged as part of the PSP offer.

Awareness of the increased numbers of Disability Employment Advisers (DEAs) and the introduction of Community Partners as part of the PSP similarly varied. Although the role of the DEA changed prior to the launch of the PSP, there were staff who had mistakenly associated the change in role focus (from a claimant-facing position to an advisory role working primarily with Jobcentre Plus staff) as part of the PSP, while others perceived the change to be related to the roll-out of UC. There were examples of staff initially lacking any awareness of the role of Community Partners, although this changed as Community Partners became more visible and integrated themselves into Jobcentre Plus (JCP). For other staff, although they were familiar with the Community Partners as individuals, there was limited understanding of how the role related to the PSP. In some circumstances (when PSP was first launched), Community Partners felt that there was a lack of clarity among all staff about their role and those of the DEA and Small Employer Adviser (SEA). This lack of clarity led Community Partners to feel cautious around interacting with the role of DEAs in supporting work coaches and the role of SEAs when contacting local employers.

There is a lot of overlap with what the small employer advisers do, what the Community Partners do, what the employer advisers do, what the DEA coaches do. I don’t think it was clearly thought through where the remits were and where the boundaries were, so there was a lot of dancing around each other because people were frightened of stepping on each other’s toes.

(Community Partner, ESA)

Over time, as staff across all grades in JCPs became more familiar with their role and the support they could provide. Community Partners reported that positive working relationships developed, and DEAs and/or work coaches began to approach them for advice and support about specific cases.

The PSP qualitative case studies indicated that PSP was introduced to staff in a variety of ways. There were a range of ways work coaches and DEAs had learned about the PSP, including through:

- attendance at launch/presentation given to staff by a team leader

- online via either e-learning, email or the DWP intranet

- one-to-one discussions with managers or other staff such as SEAs

- presentations about specific initiatives (rather than the PSP as a whole)

- team meetings

- workshops on delivering PSP

View on how PSP was introduced to staff were mixed. Some work coaches and DEAs reported being dissatisfied with the way PSP had been introduced. In some circumstances work coaches were dissatisfied because they perceived that their team leaders lacked knowledge of the PSP, which made it difficult to get a comprehensive overview. Other work coaches felt that the eligibility criteria had initially been unclear, making it challenging to identify who the PSP was targeting (although this was resolved once the eligibility criteria had been broadened to include any ESA claimant or UC claimant on a health journey). There were also mixed views on whether written information via email was a helpful way to introduce the PSP. In some circumstances, staff felt that there was too much information to absorb, while others reported that the information was too limited. Finally, work coaches and DEAs reported that there had been a time lag between launch and implementation, which made it more difficult to retain and use any information. This last finding may be in part a reflection of the staggered rollout of some of the PSP strands. There were a group of DEAs who were happy with the way PSP had been introduced. In particular, they found presentations from JCP staff and provider organisations, which provided details of the support on offer to claimants, a useful way of understanding different strands of the PSP.

3.2 Type of employment support offered

Evidence from the staff interviews suggest that claimants were referred or sign-posted to four main types of provision, these were:

- pre-employment support or training including PSP initiatives but also other specific provision such as nationally-recognised Security Industry Authority (SIA) and Construction Skills Certification Scheme (CSCS) training, and employability courses delivered by the National Careers Service. Claimants were also offered work experience through the JCP

- in-work support for those who had found and started work. Support was also offered through the Access to Work and Access to Work Mental Health programmes. However, there were few examples of this being offered

- health and disability-related services including NHS mental health services. For example, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for customers with anxiety, depression or stress; Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and autism support; and drug- and alcohol-dependency recovery support

- other general provision focused on soft-skill development, including confidence building, basic IT skills, reading courses and local social groups

Staff became aware of provision via a variety of sources, including:

- knowledge from work coaches, DEAs and Community Partners

- District Provision Tool (DPT), a locally updated database of health and disability related support that all JCP staff can access

- internal documents using software such as OneNote that listed training and general provision

- providers’ visits to the JCPs to promote the support available.

3.3 Decision-making and selection of PSP strands and existing general support options

3.3.1 Roles and responsibilities of Jobcentre Plus staff

In all PSP case study areas, work coaches were the main decision-makers when considering which support to offer to claimants, in line with the policy design. Work coaches decided which support options were suitable for a claimant, discussed their ideas with the claimant, and managed the referral process where relevant. Several factors that influenced decision-making are discussed below in 3.3.2 and 3.3.3.

In exploring which support options are available and suitable for a claimant, work coaches were able to access advice and support from DEAs.

DEAs were also able to offer three-way conversations with the work coach and claimant. The extent to which DEAs were utilised by work coaches depended, in part, on the work coach’s experience. Long serving work coaches were more likely to report feeling confident that they could identify the right support for claimants without the need of DEA support.

Work coaches and DEAs across all case study areas reported that DEAs were not always available to offer support owing to their own high workloads.

Community Partners reported that initially they had been instructed to support work coaches by upskilling them to offer appropriate advice and support to claimants, rather than provide direct support to claimants. While this continued to be a key part of their role, in case study areas where J2E was not available, some Community Partners explained that over time they began to provide support to claimants via three-way appointments with the claimant and work coach.

What they [work coaches] find most valuable is these three-way interviews where I talk to a customer and actually share some of my own lived experience, that very special bit of my role which isn’t there for other civil servants. Claimants are responding to that and they’re working with work coaches in a way they hadn’t before, yes.

(Community Partner, UC)

Work coaches described using other sources of support to help decide which support options would be appropriate for a claimant. This included:

- less experienced work coaches accessing advice from those with more experience

- engaging in case-conferences[footnote 2] with other work coaches (and DEAs)

- speaking to providers directly about what the provision will involve

- referring to internal emails which promoted provision

3.3.2 Staff and provider factors affecting referrals to external provision

There were multiple factors that influenced which external provision work coaches referred claimants to. These were:

- staff awareness of provision

- work coach relationship with external provider

- feedback from previously referred claimants

- programme availability and the likelihood of acceptance

- staff workload

Staff awareness of provision

Staff reported that their awareness of the provision on offer was an important determinant of the referrals that were made.

The District Provision Tool was one information source used by work coaches in identifying available initiatives, although some staff had difficulties accessing this on-line tool due to a lack of training on how to do so. Other sources of information included the Disability Hub (an internal source of information), other on-line guidance and information from other JCP staff. Since some work coaches were not aware of all external provision some staff were more likely to use well-promoted initiatives. For example, WHP was highly visible within Jobcentre Plus as referral numbers were closely monitored. This visibility had a positive impact on work coach referrals.

For some provision, such as J2E, there was a designated lead role at the JCP known as the Single Point of Contact, who played an important part in increasing referrals by keeping the provision at the forefront of work coaches’ minds, even when providers were not present.

Relationships with providers

The relationship between individual providers and staff was an important factor in encouraging referrals. For example, J2E providers reported that they aimed to develop good relationships with staff by spending time at the Jobcentre Plus and getting to know work coaches on a one-to-one basis. Building rapport with staff helped them to explain the benefit of their projects. Providers across all programmes also attended events at JCPs to encourage referrals. For example, one work coach reported that biannual health fairs were established where existing providers of general support could meet staff and explain the aims of their provision.

Relationship-building was reported as particularly important when provision was based on cohort entry. For example, J2E providers reported that they worked particularly closely with the JCP staff when a new 12-week programme was due to start. This had a positive impact on referral numbers; providers and JCP staff reported that as relationships strengthened, referrals increased.

Towards the end - it was a … bit of a false start to us, but towards the end I think the working relationship with our community employment specialist (role within J2E) was really getting there and she was becoming part of the work coach team.

(Work Coach Team Leader, UC)

Feedback from previous referrals

Work coaches found it helpful to hear from the providers about the progress of the claimants that they had referred as this demonstrated the potential benefits of the provision. Similarly, claimants themselves gave feedback to work coaches during and after their participation. Positive feedback received from claimants encouraged future referrals. Similarly, claimants themselves gave feedback to work coaches during and after their participation. Positive feedback received from claimants encouraged future referrals to both existing general provision or PSP initiatives on offer, while negative outcomes or bad feedback discouraged referrals to both types of provision.

The provision you use is very much based upon … your experience, I suppose, of that provision. It’s really hard. You shouldn’t have it, but you do. You have your, I wouldn’t say favourites, but you know what I’m saying. You have those that you think have got more chance of success, I guess.

(Work Coach, ESA)

Ease of acceptance onto provision

A further factor that influenced the number of referrals to provision was the ease of acceptance onto the provision. Referrals to other specific provision such as programmes being run by a Further Education college, were viewed positively as work coaches reported hearing quickly whether the claimant they had referred had been accepted onto the provision. Work Coach Team Leaders and DEAs reported it was particularly difficult to promote referrals to PSP initiatives when work coaches had lots of information about other specific provision which they found simple to refer to in contrast to specific PSP initiatives such as the WHP. Some staff were reluctant to refer to PSP providers where acceptance was not guaranteed.

Staff workload

Staff found the Specialist Employability Support (SES) referral process complex, in particular where the provider was based outside of the local area. In these circumstances staff had to spend long periods of time organising for a provider to visit the local JCP to meet the claimant. This was reported as time-consuming and difficult to do when staff had large caseloads. Some staff reported that the relative ease of referring to specific providers influenced which provision they offered to claimants.

The introduction of UC was also perceived by DEAs and Work Coach Team Leaders to make it difficult for work coaches to focus on referrals to external provision. During the UC training period, such activity was viewed as a competing priority, particularly when staff were out of the office for several weeks of training.

3.3.3 Staff views on claimant factors affecting referrals to external provision

JCP staff and providers identified several claimant-related factors that affected referrals to external provision initiatives.

Eligibility

As outlined in the introduction, when the PSP was launched, eligibility criteria for the initiatives was initially limited to ESA WRAG claimants (and UC equivalents) who had made an application for ESA or UC since April 2017. Work coaches found at the early stages of the PSP, the number of eligible claimants was very small.

At the time the [Personal Support Package] came about there was a huge backlog of work capability assessments … And that’s why we had so few people who had the right outcome decision for it.

(DEA, ESA)

Difficulty engaging claimants

JCP staff reported that it took time to build the necessary relationships with claimants that could facilitate the discussion of external provision. Staff reported particular challenges in building engagement for claimants for those that had previously been in the Support Group and had therefore not been required to attend regular appointments with their work coach.

Health condition

The severity of a claimant’s health condition was a factor in determining whether claimants were offered support as well as the type of support offered. Staff acknowledged that it would be inappropriate to ask claimants with more severe health conditions to attend certain types of provision. For example, one work coach stated:

I think [offering support] depends on the severity of their health as to what they can manage first and foremost … I would work out what they feel they can manage, it might be just interaction with me to start with to build their confidence because some find it so difficult just to get into the office, you know.

(Work Coach, ESA)

Some PSP strands were perceived as suiting claimants with particular health conditions. For example, some work coaches felt that the WHP was appropriate for claimants with mental health conditions as it provided the long-term support they were perceived as requiring. In contrast, one work coach reported that the J2E programme was not suitable for claimants who had social anxiety and/or depression as this was perceived to limit their ability to interact in a group setting (J2E is a peer support job club in a group setting).

Other claimant characteristics

Staff also reported that a range of other claimant characteristics influenced the choice of support options. For example, where claimants had drug or alcohol dependency, support to deal with this was prioritised over work-related support. Similarly, where claimants were perceived to have ‘chaotic lifestyles’, they were deemed as unsuitable for work-related support.

The duration of support was also reported as a consideration for some JCP staff. For example, the long-term support offered by WHP and SES might be seen as more appropriate for claimants with more significant barriers to work.

Proximity to the labour market and claimant motivation

Work coaches described some support options were targeted at different groups of claimants. For example, the WHP was identified as a better fit for people who would be ready for work within twelve months, while Work Choice was more appropriate for claimants who need longer term help. Work coaches also indicated that the motivation of claimants was important to consider. Willingness to move forward with their job search was identified as a factor in referrals made to the J2E programme.

3.3.4 Other factors affecting referrals

Location

Location of the provider or claimant was also felt to influence the take-up of local or PSP provision, as claimants preferred to attend provision closest to them:

[A factor that influences referrals] is the provision local. Like I say with [this] one it’s really close to the Jobcentre. Lots of people feel comfortable going there. They like the area … I hear that people feel quite comfortable that it’s going to be delivered locally and they understand exactly where they’re going.

(Work Coach, ESA)

3.4 Summary

There were varying levels of knowledge and awareness of the aims and initiatives of the PSP among JCP staff. There was broad awareness of individual initiatives and the provision available to claimants, with some staff aware of all PSP initiatives. However, others expressed limited awareness that the initiatives were part of the PSP or that existing support services had been altered or expanded as part of the PSP. A lack of uniformity in the way the PSP was introduced (in terms of staggered roll out and local differences in initiatives available) made it difficult for work coaches to understand the overarching offer available to claimants.

Work coaches were the main decision makers in suggesting which support options to offer claimants. DEAs assisted work coaches to do this through one-to-one support and/or three-way conversations between themselves, work coaches and claimants. In some circumstances, where Community Partners had specific specialist health knowledge, they also had three-way conversations with work coaches and claimants.

The qualitative case studies indicate that a range of factors influenced what provision was offered to PSP eligible claimants. These included: if staff were aware of the provision; the extent to which some provision had been promoted across JCP; staff relationships with providers; feedback and outcomes from prior referrals to provision the availability of spaces on the provision, and the likelihood of acceptance; and staff workload.

Staff also reported that claimant characteristics affected whether staff offered and/or referred claimants to local provision and PSP support. Perceived barriers (or enablers) included: eligibility of the claimant; type and extent of health condition; the location of provision; and the claimant’s proximity to the labour market.

4. Take-up of support

This chapter draws on the PSP claimant survey and PSP qualitative case studies. It discusses the support taken-up by claimants, including the factors that influenced take-up, experiences of support taken-up, any barriers encountered to participation, and reasons for dropping out of support.

4.1 Type of support taken-up

4.1.1 Support offered and taken-up

As discussed earlier in the report, PSP covers a wide range of both existing and new initiatives (including work coach support), which are focussed on helping claimants with health conditions and disabilities move closer to work. Consequently, the PSP survey explored claimants’ recall of all advice and support which they may have been offered by their work coach since the introduction of the PSP (April 2017).

Support offered

Claimants were asked about a list of possible support work coaches could offer them or refer on to, such as help applying for jobs or CV writing, but also more general support, including helping building confidence, advice on how to manage money, training to develop IT skills. The survey also asked specific questions about four externally delivered programmes within the PSP package, namely Journey to Employment (J2E), Work and Health Programme (WHP) and Specialist Employability Support (SES) and Work Choice (WC).

Overall, 65 % of claimants reported being offered one or more of the support options as summarised in Figure 4.1 below. The most commonly mentioned support option was developing an action plan (reported by 34 % of claimants).

Figure 4.1 Types of support offered by the work coach

| Type of support | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Developing an action plan | 34% |

| Info about local support | 29% |

| Training in how to look for work | 27% |

| Help to find voluntary work | 25% |

| Help with applying for jobs | 25% |

| Help building confidence | 23% |

| Help to find work experience | 21% |

| Group sessions with peers | 20% |

| Advice to manage health | 18% |

| Help with IT skills | 16% |