European Social Fund and Youth Employment Initiative Leavers Survey Report 2016-2019

Published 2 March 2022

Applies to England

European Social Fund and Youth Employment Initiative Leavers Survey Report 2016-2019

Research on behalf of Department for Work and Pensions and European Commission

March 2022

DWP research report no. 1010

A report of research carried out by IFF Research on behalf of the Department for Work and Pensions.

Crown copyright 2022

You may re-use this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence

Or write to the:

Information Policy Team

The National Archives

Kew

London

TW9 4DU

Email: psi@nationalarchives.gov.uk

This document/publication is also available on our GOV.UK website

If you would like to know more about DWP research, email socialresearch@dwp.gov.uk

First published March 2022

ISBN 978-1-78659-359-7

Views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Department for Work and Pensions or any other government department.

Executive summary

This report provides findings for the England European Social Fund (ESF) and Youth Employment Initiative 2016-2018 Leavers (YEI) survey. The research was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) to explore the experiences of people in England who had recently left work-related courses/programmes funded through the ESF, including the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI). Specifically, the research sought to collect information about participants’ situation on entry to and six months after they have left ESF provision (to determine long-term outcomes), and participant views on the provision.

The research involved a large-scale quantitative telephone survey with 19,769 participants who had left the ESF provision between December 2015 and December 2018, and YEI provision between December 2015 and May 2019.

Some of the main findings from this research include:

- The ESF programme reached many people who faced labour market disadvantage. For many of those assisted, unemployment was an entrenched position.

- Provision was received very positively and views were consistently positive across Investment Priority and CFO.

- Improvements in soft-skills as a result of receiving ESF provision were widely reported, and participation appears to have greatly increased optimism about finding employment.

- Half of YEI leavers received a job offer in the six months following provision.

- Job outcomes across the ESF programme were quite common, and experienced by a range of leavers.

- The job outcome rate was comparable across all CFOs focussing on employability support (HMPPS, DWP and National Lottery Community Fund) and Direct Providers.

- Nearly all of those who received in-work support were still in employment six months later, a large minority reported progress at six months and nearly all reported improved prospects for the future.

- Positive employment outcomes should decrease welfare claimants, indeed the proportion of DWP participants claiming benefits decreased by a quarter between entry to provision and six months later.

- There was a slightly unexpected shift of some participants from being unemployed at the start of provision to being economically inactive six months after leaving; this happened for a third of participants unemployed on provision entry. Most commonly, these leavers were in education or training, or unable to work because of health at six months.

Acknowledgements

This report was commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). DWP is Managing Authority for the European Social Fund in England. The evaluation was part-funded by European Social Fund (ESF) technical assistance.

We would like to thank Will Farbrother and Nick Campbell in DWP’s ESF Evaluation Team for their guidance and contributions throughout the project, and to the members of the ESF Evaluation Steering Committee for their advice and expertise.

We would also like to thank all the participants that gave up their time to take part in the study. Without them of course, the research would not have been possible.

Authors

A large team of researchers worked on the study and contributed to the report.

Lorna Adams is a Director at IFF, where she has worked for 20 years. She specialises in studies in the employment and benefits field, particularly for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

Mark Winterbotham is a Director at IFF, where he has worked for 25 years specialising in labour market research.

Andrew Skone James is a Director at IFF, where he has worked for 10 years. He specialises in research in the learning and skills field. Christabel Downing is a Senior Research Manager at IFF, where she has worked for six years. Christabel specialises in evaluation, with a particular focus on work, welfare and wellbeing research.

Hamish Evans is a Research Executive and has worked at IFF Research for a year.

Other IFF researchers that have contributed to the project include Sam Selner, Catherine Turner and Libby Eastwood.

Abbreviations

| Acronym | Definition |

|---|---|

| BAME | Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic |

| CFO | Co-financing Organisation |

| CSR | Country Specific Recommendations |

| DWP | Department for Work and Pensions |

| ESF | European Social Fund (unless specified this refers to 2014-2020 ESF programme) |

| ESFA | Education and Skills Funding Agency |

| ESFD | European State Finance Database |

| EU | European Union |

| HMPPS | Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service, formerly National Offender Management Service |

| IP | Investment Priority |

| LEPs | Local Enterprise Partnerships |

| MA | Managing Authority |

| MI | Management Information – refers to participant level information collected by ESF providers |

| NEET | Not in Education, Employment or Training |

| NLCF | National Lottery Community Fund |

| YEI | Youth Employment Initiative |

Glossary of terms

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Basic skills | Basic skills are defined as entry level, level 1 or level 2 in English, maths or English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL; where English is not the participant’s ‘mother tongue’) |

| Category of region | The categorisation of regions as ‘less developed regions’, ‘transition regions’ or ‘more developed regions’: (a) less developed regions, whose GDP per capita is less than 75% of the average GDP of the EU-27; (b) transition regions, whose GDP per capita is between 75% and 90% of the average GDP of the EU-27; (c) more developed regions, whose GDP per capita is above 90% of the average GDP of the EU-27. The classification of regions under one of the three categories of regions was determined on the basis of how the GDP per capita of each region relates to the average GDP of the EU-27 for the same reference period (2007-2009). |

| Co-financing Organisations (CFOs) | Public bodies which bring together ESF and domestic funding for employment and skills so that ESF complements national programmes. Provision for the 2014-2020 Operational Programme was delivered through 4 Co-financing Organisations, the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA), DWP, National Lottery Community Fund (formerly Big Lottery Fund); Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Services (HMPPS, replacement of National Offender Management Service or ‘NOMS’), as well as direct providers. |

| Disadvantaged participants | In line with the European Commission definition, these are participants who: * Lived in a ‘jobless household’[footnote 1]; * Were a single adult household with dependent children; * Had no formal qualifications; * Lacked basic skills[footnote 2]; * Were homeless/living in a hostel at start of provision; * Were from an ethnic minority background; or * Had drug or alcohol dependency at start of provision. |

| Disability or long-term health condition | A physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on your ability to do normal daily activities. * ‘substantial’ is more than minor or trivial - e.g. it takes much longer than it usually would to complete a daily task like getting dressed * ‘long-term’ means 12 months or more |

| Economically Inactive | Those not working, and are either not looking for work, or not available for work. It includes the following groups: * participants in full or part-time education; * those not in employment because of sickness or disability; * those looking after the family or home full time; * those caring for an adult family member, relative or friend who has any long-standing illness, disability or infirmity; * those in a voluntary, unpaid role or internship (not a family business); and * those in prison. |

| European Social Fund (ESF) | The European Social Fund (ESF) is the European Union’s main fund for supporting employment in the member states of the European Union as well as promoting economic and social cohesion. |

| ESF provider | Refers to any or all organisations delivering ESF funded provision, including CFOs, opt-in organisations, direct bid providers, and intermediary bodies or organisations contracted by them to offer provision |

| Full-time work | Work for an employer in a paid role 30 hours or more per week. |

| Improved labour market situation | Persons in an improved labour market situation are those who are employed when entering ESF support and who, following the support, transited from precarious to stable employment, and/or from underemployment to full employment, and/or have moved to a job requiring higher competences / skills /qualifications, entailing more responsibilities, and/or received a promotion 6 months after leaving the ESF operation. |

| Jobless household | Jobless households are households where no member is in employment, i.e. all members are either unemployed or inactive. |

| Long-term unemployed | The definition of long-term unemployed varies with age: * Youth long-term unemployed (<25 years of age) = more than 6 months continuous spell of unemployment * Adult long-term unemployed (25 years of age or more) = more than 12 months continuous spell of unemployment |

| Part-time work | Work for an employer in a paid role less than 30 hours per week. |

| Precarious employment | Temporary employment with an employer or a work contract of limited duration. |

| Stable employment | Work for an employer with a permanent or open-ended contract. |

| Underemployed | Where an individual is working part-time but wanting full-time work. |

| Wrap around support | A combination of mentoring and 1:1 support that encourages retention in existing learning opportunities, rather than offer alternative learning pathways with limited progression routes. |

| Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) | The Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) is one of the main EU financial resources to support Youth Guarantee schemes[footnote 3]. The initiative was launched to provide support living in regions where youth unemployment was higher than 25 per cent. It ensures that in parts of Europe where the challenges are most acute, young people can receive targeted support. In England the YEI is aimed at 15-29 year old NEETs (Not in Employment, Education or Training). |

Summary

Introduction

The European Social Fund (ESF) was set up to improve employment opportunities in the European Union (EU) and thereby raise standards of living. The Department for Work and Pensions is the Managing Authority (MA) of ESF funds in England.

The ESF 2014-20 Operational Programme - part of the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) Growth Programme for England - aimed to deliver against priorities to increase labour market participation, promote social inclusion and develop the skills of the potential and existing workforce.

There are five investment priorities (IPs) underpinning the 2014-20 Operational Programme which directly benefit individuals:

- IP 1.1: access to employment for jobseekers and inactive people

- IP 1.2: sustainable integration into the labour market of young people, through ESF funding

- IP 1.3: sustainable integration into the labour market of young people, through Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) funding

- IP 1.4: active inclusion

- IP 2.1: increasing the skills of the current workforce, enhancing equal access to lifelong learning

Provision for the 2014-2020 Operational Programme was delivered through 4 Co-financing Organisations, the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA), DWP, National Lottery Community Fund (NLCF, formerly Big Lottery Fund); Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Services (HMPPS, replacement of National Offender Management Service or ‘NOMS’), as well as direct providers.

Research aims (Chapter 1)

The DWP commissioned IFF Research to conduct a study exploring the experiences of people in England who had recently left work-related training courses funded through the ESF, including the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI). Specifically, the research sought to collect information about participants’ situation on entry to and six months after they have left ESF provision (to determine long-term outcomes), and participant views on the provision. This information is also needed to meet European Commission requirements to supply Long-Term Results Indicators as set out in the Operational Programme.

The research is part of a wider evaluation programme to provide robust evidence of the impact of the 2014-2020 ESF in England.

Methodology (Chapter 1)

The research involved a large-scale quantitative telephone survey with participants who had left the ESF provision between December 2015 and December 2018, and YEI provision between December 2015 and May 2019. Leavers were contacted at least six months after leaving provision, with all fieldwork across the pilot and nine mainstage waves taking place between February 2017 and January 2020.

In total, 19,769 interviews were completed with ESF and YEI leavers across the pilot and mainstage, with an average response rate of 23 per cent.

Summary of findings

A wide variety of provision types were offered through the range of co-financing organisations (CFOs), from courses designed to reduce the risk of redundancy to those tackling the barriers to work specifically faced by current, or ex-offenders. With the study covering a wide coverage of this provision, any comparisons of outcomes across different types of provision should be made in this context.

Key groups and demographics (Chapter 2)

Approximately 560,000 individuals completed ESF provision between December 2015 and December 2018, and just under 50,000 completed YEI provision between December 2015 and June 2019 (the relevant timeframes for this research).

IPs 1.1 and 2.1 accounted for the greatest proportions of leavers (33 per cent and 28 per cent, respectively). Around one in five leavers (19 per cent) were under IP 1.4, while lower proportions fell under IPs 1.2 (12 per cent) and 1.3 (YEI, 8 per cent).

Each CFO had a corresponding focus by IP(s). HMPPS and National Lottery Community Fund provision both related entirely to IP 1.4, and the vast majority of DWP provision (90 per cent) related to IP 1.1. Direct Provider provision predominantly focused on IP 1.3 (62 per cent) but addressed all IPs, while Skills Funding Agency focused on all IPs except 1.3, with IPs 1.1 and 2.1 most common (34 and 39 per cent, respectively).

This relationship means that many of the findings by CFO are likely to be related to differences by IP and their target audiences.

Labour market status on entry (Chapter 2)

Just over half (56 per cent) of participants were unemployed and looking for work and 15 per cent were economically inactive on entry to the programme. Nearly one-third (29 per cent) were in employment.

The profile of labour market status within IP and CFO aligned with the focus of each priority:

- Most IP 2.1 participants (92 per cent) of were employed on entry, in line with the priority’s objective to address the basic skills and increase the skills levels of individuals in work; this group made up the majority of individuals employed. One in five (20 per cent) participants under IP 1.2 were also employed on entry; employment rates across all other IPs were extremely low.

- Owing to the ESFA having a large proportion of participants under IP 2.1, this was the only CFO with a considerable proportion of participants employed on entry (40 per cent). HMPPS and DWP participants were the most likely to be economically inactive on programme entry (35 per cent and 34 per cent).

More than four-fifths (82 per cent) of participants in work on entry to provision were working for an employer in a paid role. One in ten (10 per cent) were self-employed. Around three-quarters (74 per cent) of all employed participants were working full time, and the vast majority (90 per cent) were “fully employed”, i.e. they were working full time or working part-time and did not want to be working full time.

Most participants working for an employer were in stable employment (65 per cent), i.e. they were on a permanent or open-ended contract. Around one in seven were in temporary employment or that with a work contract of limited duration (also referred to as ‘precarious employment’, 14 per cent) or employment of unknown stability (13 per cent).

Overall, four per cent of participants were in training or education on entry to the programme.

The majority (85 per cent) of participants unemployed on entry cited barriers to work. Lack of recent working experience and/or availability of jobs were the most common prospect-related barriers to work, both cited by nearly half (48 per cent) of all unemployed participants. Concern around lack of recent experience was more common among YEI participants (59 per cent versus 47 per cent ESF only).

Barriers related to personal characteristics were less common overall, with just under half (49 per cent) of unemployed individuals facing no barriers in this regard. Significantly more ESF (31%) than YEI (18%) participants felt that their disability or health problem was making it harder for them to find work.

Programme experience (Chapter 3)

Support needs and assistance

Just over a quarter (27 per cent) of participants had parental/guardianship responsibilities for children under 18. Only four per cent received support/assistance with childcare responsibilities from their provider, the vast majority (91 per cent) were not offered this support.

Eight per cent had caring responsibilities for a family member, relative or friend. As with childcare, only a small minority (six per cent) received support/assistance in this regard; most (88 per cent) were not offered this support.

Around a quarter (26 per cent) had a mental or physical health condition, or illness expected to last 12 months or more. Approaching a third (31 per cent) of these participants received support and a further eight per cent were offered support.

Regardless of the support need and related assistance, the vast majority (at least 90 per cent across the three types) of participants were satisfied and just under three-quarters said they would have had difficulty attending the course without it.

Programme benefits and satisfaction

Views on the provision were broadly positive:

- Around nine in ten were satisfied with:

- Information and guidance they received on what would be delivered through the programme (88 per cent)

- Feedback and guidance they received during the programmes (87 per cent)

- Relevance of the programme to their specific needs (86 per cent).

- More than three-quarters of all leavers thought the difficulty of the course and the amount of time spent on the course was ‘about right’ (78 per cent for both difficulty and duration).

- The majority of participants reported forms of improved confidence and skill development as an outcome (e.g. self-confidence about working, 73 per cent; improvement ability to do things independently, 72 per cent).

- Nine in ten (90 per cent) participants employed at programme entry reported the course has had helped them in their work environment.

- Eight in ten participants (81 per cent) inactive or unemployed at entry reported that the course had helped them find a job or made it more likely they will find work.

- One in five (19 per cent) YEI participants undertook a traineeship as part of the programme. Nine in ten (89 per cent) who did were satisfied with their traineeship experience; 54 per cent were very satisfied.

- Assessing all the support received from the programme and how they may have benefited since, more than eight in ten (82 per cent) expressed satisfaction, with nearly half (46 per cent) saying were very satisfied.

Employment at six months (Chapter 4)

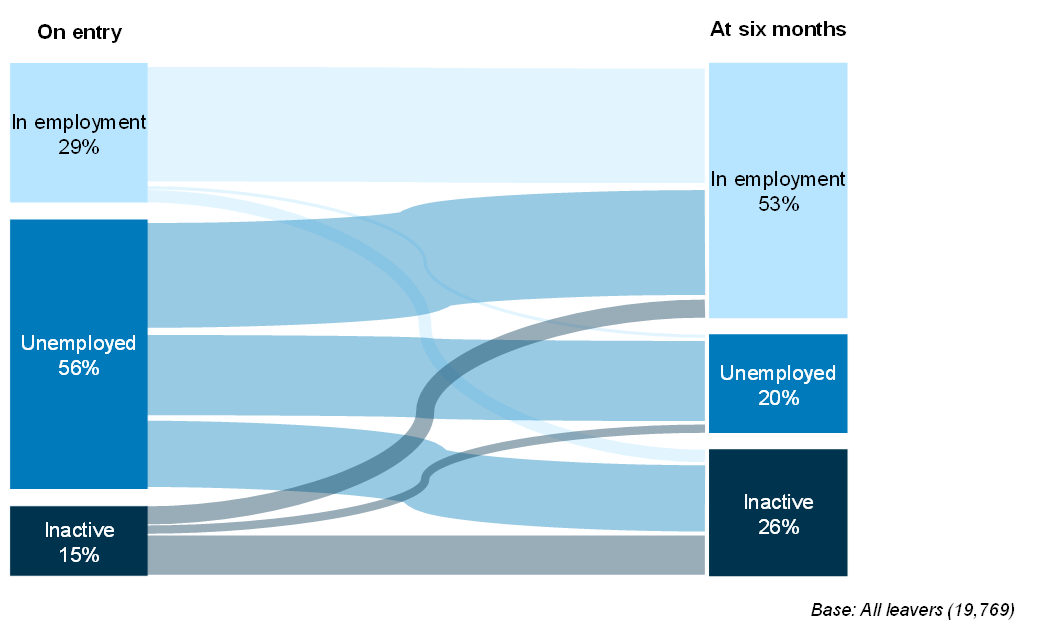

More than half (53 per cent) of individuals were in employment six months after leaving the programme compared to less than three in ten (29 per cent) at entry, representing a 24 percentage point increase in employment. While the proportion of individuals unemployed fell from 56 to 20 per cent, there was also a rise in the proportion economically inactive from 15 to 26 per cent.

Employment among ESF-only participants grew 22 percentage points, from 32 per cent to 54 per cent, while YEI-only participants increased from one per cent to 45 per cent. For both leaver groups, unemployment reduced while economic inactivity grew.

Nine per cent of all leavers were in education or training six months after leaving their provision (falling into the inactive group); this was more than double the proportion in education or training at time of entry (four per cent).

In terms of individual-level transitions, just over a quarter (26 per cent) of leavers had remained in employment, and a similar proportion (27 per cent) had moved into employment (three per cent had become inactive, one per cent were unemployed). More than two-fifths (43 per cent) of all participants remained unemployed or inactive. More than half of YEI participants (55 per cent) remained unemployed or inactive at six months compared to 42 per cent of ESF participants, yet more than two-fifths (44 per cent) under YEI moved into employment. In contrast ESF participants were much more likely to have been employed at the start of the programme, with 28 per cent remaining employed at six month and four per cent moving out of employment (compared to a negligible proportion of YEI). A quarter of ESF participants (26 per cent) moved into employment.

Type of employment

The proportions of leavers working for employer, self-employed or on an apprenticeship were largely unchanged compared to programme entry.

In terms of type of employment at six months versus programme entry, there was a very small rise in part-time employment (from 25 per cent to 28 per cent). Correspondingly, the proportion of participants underemployed rose modestly from nine per cent to 12 per cent.

Precarious employment for an employee – i.e. temporary employment or that with a work contract of limited duration - was more common at six months than on entry; 21 per cent compared to 14 per cent at programme entry were in precarious employment.

In-work outcomes

Among leavers that were employed on entry and at the 6-month point, around two-fifths (39 per cent) of participants reported being given more responsibility, a slightly lower proportion (36 per cent) reported a requirement for higher skills or competencies in their role, and almost a quarter (23 per cent) required a higher level of qualification.

Employed participants reported a range of other benefits or improvements to their job prospects compared to their situation on entering the programme. More than half of leavers had more opportunities for training (65 per cent), more job satisfaction (60 per cent), improved future pay and promotion prospects (57 per cent) and job security (52 per cent). Just under half (45 per cent) said they have received an hourly or annual pay rise over the six month period.

Individuals with improved labour market situations six months after leaving their course were more satisfied with their experience than those without (90 per cent compared to 85 per cent), although the vast majority of individuals without these improvements were still satisfied.

Conclusions (Chapter 5)

Some of the main conclusions that can be drawn from this research are that:

- The ESF programme reached many people who faced labour market disadvantage.

- For many of those assisted, unemployment was an entrenched position.

- Provision was received very positively and views were consistently positive across Investment Priority and CFO.

- Support with childcare or other care was not widespread.

- Improvements in soft-skills as a result of receiving ESF provision were widely reported.

- Participation appears to have greatly increased optimism about finding employment.

- Half of YEI leavers received a job offer in the six months following provision.

- Job outcomes across the ESF programme were quite common and experienced by a range of leavers.

- The job outcome rate was comparable across all CFOs focussing on employability support (HMPPS, DWP and NLCF) and Direct Providers.

- Nearly all of those who received in-work support were still in employment 6 months later, a large minority reported progress at 6 months and nearly all reported improved prospects for the future.

- Most leavers were satisfied with their provision; satisfaction was highest among those who were employed in entry.

- Positive employment outcomes should decrease welfare claimants, indeed the proportion of DWP participants claiming benefits reduced by a quarter between entry to provision and six months later.

- There was a slightly unexpected shift of some participants from being unemployed at the start of provision to being economically inactive 6 months after leaving; this happened for a third of participants unemployed on provision entry. Most commonly, these leavers were in education or training, or unable to work because of health at six months.

It is not possible for this research to definitively state whether these improvements in job situations would have happened without the receipt of provision funded through ESF. However other research is being conducted using administrative datasets to provide a counterfactual and will provide greater understanding of the impact of provision.

1. Introduction

The European Social Fund

The European Social Fund (ESF) was set up to improve employment opportunities in the European Union (EU) and thereby raise standards of living.

The European Social Fund (ESF) 2014-20 Operational Programme is part of the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF)[footnote 4] Growth Programme for England in 2014-2020. Its aim is to deliver the programme’s priorities to increase labour market participation, promote social inclusion and develop the skills of the potential and existing workforce, helping individuals fulfil their potential. Through the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) it also contributes to improving youth employment in areas with higher rates of youth unemployment by providing support for harder to reach NEET (not in employment, education or training) young people.

Objectives of the fund

The ESF is intended to promote the Europe 2020 objectives for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, with a primary focus on the latter[footnote 5]. Specifically, achievement targets related to employment, education and poverty reduction:

- Employment: 75% of the population aged 20-64 should be in employment. Aiming to raise to 75% the employment rate for women and men aged 20-64, through the greater participation of young people, older workers and low-skilled workers and the better integration of legal migrants.

- Social inclusion: 20 million less people across the EU should be at risk of poverty.

- Education: Improving education levels, in particular by aiming to reduce school drop-out rates to less than 10 per cent and by increasing the share of 30-34 years old having completed tertiary or equivalent education to at least 40%.

It also sought to contribute to the achievement of the relevant parts of the 2017 Country Specific Recommendations (CSRs) which are:

- Address skills mismatches, provide for skills progression, including continuing to strengthen the quality of apprenticeships and providing for other funded “Further Education” progression routes

Investment Priorities

Underpinning the 2014-20 ESF Programme are 3 ‘priority axes’, namely:

- Priority Axis 1: Inclusive Labour Markets, which combines activities to address employment and social inclusion issues

- Priority Axis 2: Skills for Growth

- Priority Axis 3: Technical Assistance \and 2. Priority Axis 1 addresses two ‘thematic objectives’:

- Thematic Objective 8: Promoting sustainable and quality employment and supporting labour mobility

- Thematic Objective 9: Promoting social inclusion, combating poverty and any discrimination

While Priority Axis 2 addresses one thematic objective:

- Thematic Objective 10: Investing in education, training and vocational training for skills and life-long learning

Table 1.1 below provides further detail on the Thematic Objectives and Investment Priorities chosen from the regulations which make up Priority Axis 1 and 2.

Within these priorities, certain audiences were identified for the Operational Programme to focus on; these are groups who face relative disadvantages in the labour market:

- people who were unemployed or economically inactive, especially disadvantaged groups such as people with disabilities, lone parents, older workers and ethnic minorities;

- women returners and other groups of women outside the labour market;

- young unemployed people, and especially those not in education, employment or training (NEET);

- people who lack basic skills, whether unemployed or already in the workforce.

Table 1.1 ESF Priority Axis and Investment Priorities

| Priority Axis | Thematic Objective | Investment Priority |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 1.1 (8i): Access to employment for jobseekers and inactive people, including the long term unemployed and people far from the labour market, also through local employment initiatives and support for labour mobility |

| 1 | 8 | 1.2 (8ii ESF): Sustainable integration into the labour market of young people (ESF) in particular those not in employment, education or training (NEET), including young people at risk of social exclusion and young people from marginalised communities, including through the implementation of the Youth Guarantee. |

| 1 | 8 | 1.3 (8ii YEI): Sustainable integration into the labour market of young people (YEI) in particular those not in employment, education or training, including young people at risk of social exclusion and young people from marginalised communities, including through the implementation of the Youth Guarantee. |

| 1 | 9 | 1.4 (9i): Active inclusion, including with a view to promoting equal opportunities and active participation, and improving employability. |

| 2 | 10 | 2.1 (10iii): Enhancing equal access to lifelong learning for all age groups in formal, non-formal and informal settings, upgrading the knowledge, skills and competences of the workforce, and promoting flexible learning pathways including through career guidance and validation of acquired competences. |

Youth Employment Initiative

The Youth Employment Initiative (YEI) is one of the main EU financial resources to support Youth Guarantee schemes[footnote 6]. The initiative was launched to provide support living in regions where youth unemployment was higher than 25 per cent. It ensures that in parts of Europe where the challenges are most acute, young people can receive targeted support.

Participants in YEI provision had to be NEET (not in employment, education or training), aged 15 to 29 and reside in an area eligible for the initiative.

Through England’s ESF Operational Programme (OP), flexibility to deliver YEI support to those aged up to 29 was provided to areas eligible for YEI funding. Eligible areas are determined at the level of Nomenclature of Units for Territorial Statistics (NUTS) areas, NUTS being a standard developed and regulated by the EU in order to reference the sub-division of countries for statistical purposes. There are four NUTS 2 regions in England eligible for YEI funding: Inner London, Merseyside, Tees Valley & Durham, and West Midlands. In addition, the following NUTS3 areas are eligible: Leicester, Nottingham, Kingston upon Hull, and Thurrock.

Typically, YEI support includes access to apprenticeships, traineeships, job placements and further education, amongst other employability assistance combined with wrap around[footnote 7] support for participants.

Co-financing organisations

The DWP has had overall responsibility for ESF funds in England 2007-20, and manages the England ESF programme at a national level.

ESF funds are distributed through ‘co-financing organisations’ (CFOs); public bodies which bring together ESF and domestic funding for employment and skills so that ESF complements national programmes.

Provision for the 2014-2020 Operational Programme was delivered through 4 co-financing organisations, the Education and Skills Funding Agency (ESFA), DWP, National Lottery Community Fund (formerly Big Lottery Fund); Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Services (HMPPS, replacement of National Offender Management Service or ‘NOMS’), as well as direct providers.

Types of provision

The provision on these courses/training programs can vary considerably. Some participants completed a course or studied towards a certificate in something work-related. Some did courses in English, maths or computer skills or had had training in how to look for work. Others received mentoring, coaching or other personalised support in work-related activities.

Research objectives

As part of the ESF 2014-20 Operational Programme, the DWP (as Managing Authority) was required to monitor and evaluate the programme. As part of meeting this requirement, the DWP commissioned IFF Research to conduct a study exploring the experiences of people in England who had recently left work-related training courses funded through the ESF, including the Youth Employment Initiative (YEI).

The main research aims were to:

1. To collect information about participants’ situation six months after they had left ESF provision; the 6-month point is key because it is on activities at this point that most of the ESF long-term indicators are based[footnote 8].

2. To measure the effectiveness of ESF and YEI for example through hard outcomes, such as employment situation, job progression etc., as well as participants’ perception of their own development (skills learned etc.).

3. To produce data on the experience and effectiveness of ESF and YEI, including participants’ perspectives. This will be used to inform ESF and YEI evaluations on effectiveness, efficiency and impact.

In addition to meeting requirements to evaluate the impact and effectiveness of the current ESF programme, the results will help the UK Government to decide which types of work-related training courses to fund in the future after exit from the European Union, and to improve the services they provide.

The research is part of a wider evaluation programme to provide robust evidence of the impact of the 2014-2020 ESF in England and generate evidence about what works and why, in helping disadvantaged groups and those furthest from the labour market to move closer to it, gain sustainable employment, attain skills and progress in-employment. Other sources of evidence include counterfactual analysis and qualitative case study work, and potential Cost Benefit Analysis

Methodology

The research involved a large-scale quantitative survey with participants who had left the ESF provision between December 2015 and December 2018, and YEI provision between December 2015 and May 2019. Interviews were conducted by computer assisted telephone interviewing (CATI).

The research also involved a follow-up survey among a subset of YEI leavers – individuals who were in employment six months after completing their provision. The purpose of this survey was to explore what individuals were doing 12 months post-provision. Findings for this research element are not explored in this report, but an overview is provided in Appendix B.

This section provides an overview of key sample and methodology information, further detail can be found in the Technical Appendix (Appendix A).

Sampling

All ESF and YEI providers were required to record and routinely share individual participant contact details with the DWP to support monitoring and evaluation. Following a matching process, sample was then transferred from the DWP to IFF Research.

A total of ten sample batches were transferred to IFF covering the pilot stage and 9 subsequent survey waves. Sample was cleaned and records removed if any of the following applied:

- No address (as unsuitable for mailout)

- No phone number

- Repeat leaver (i.e. included in a previous sample batch due to completion of earlier provision) or duplication within the same batch

- Leave date too early or too late

Beyond cleaning, sample selection was only applied to waves 8 and 9; a census approach was used for all other waves due to low sample volumes at these stages. For Wave 8, sample was only selected if it applied to an investment priority in which interview targets had not been met. Wave 9 consisted of YEI leavers only.

Further information on sample transfers and cleaning can be found in the Technical Appendix (Appendix A).

Table 1.2 provides detail on sample volumes received and used for each wave.

Table 1.2 Overview of sample received and starting sample, by wave[footnote 9]

| Wave | Sample supplied | Starting sample | % of sample supplied used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot | 1,143 | 183 | 16 |

| Wave 1 | 1,338 | 505 | 38 |

| Wave 2 | 1,836 | 1,321 | 72 |

| Wave 3 | 2,806 | 1,462 | 52 |

| Wave 4 | 5,819 | 1,982 | 34 |

| Wave 5 | 5,751 | 1,548 | 27 |

| Wave 6 | 6,533 | 1,340 | 21 |

| Wave 7 | 84,865 | 56,696 | 67 |

| Wave 8 | 229,136 | 22,022 | 10 |

| Wave 9* | 705 | 359 | 51 |

| Total | 339,932 | 87,418 | 26 |

*Wave 9 consisted of YEI leavers only

All useable sample was sent an introductory letter two weeks in advance of fieldwork starting to notify them of the research, its objectives, and giving them an opportunity to opt out via email or by leaving a voicemail message.

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire was designed to address the research objectives and collect the necessary indicator data across the priorities. Table 1.2 provides an overview of questionnaire coverage, the full questionnaire is presented in Appendix C.

| Section | Coverage of questions |

|---|---|

| Screener | Introducing the survey and confirming eligibility. |

| Section A: Status when started course | What the main activity of the participant was immediately before starting their provision. Details of employment, unemployment, qualification and skills, and benefits claimed (for DWP provision) were also collected. |

| Section B: Experience of the course | Participant support needs (child and other carer responsibilities, disability) and assistance, work-related skills and support gained, and satisfaction with the provision. For YEI leavers, details of traineeships. |

| Section C: Status six months after completing course | What participants were doing six months after completing their provision; details on employment, unemployment, qualification and skills, and benefits claimed (for DWP provision) were also collected. |

| Section D: YEI leavers | Job offers and opportunities in the six months following provision completion, among YEI leavers only. |

| Section E: Demographics information | Capturing information on living situation, six and gender, age, ethnicity, long-term limiting illness (LTLI), and sexual orientation. |

| Section F: Recontact questions | Whether participants are willing for their responses to be linked to other DWP held administrative records. For YEI leavers in employment at 6-month point, whether they are willing to be to be called back for a 12-month point survey[footnote 10] |

The questionnaire was tested through piloting and cognitive testing between Thursday 16th February 2017 and Tuesday 28th February 2017. Pilot interviews were completing with 24 individuals, and 19 of these participants went on to take part in a cognitive interview to check engagement, relevance and ease of understanding of the survey.

Fieldwork

Mainstage fieldwork took place across nine waves between March 2017 and January 2020. In total, 19,769 interviews were completed with ESF and YEI leavers across the pilot and mainstage, with an average conversion rate of 23 per cent.

Table 1.3 provides breakdown of the fieldwork dates, starting sample, number completes and conversion rates for each wave.

Table 1.4 Fieldwork dates, volumes and conversation rates by wave

| Wave | Fieldwork dates | Starting sample | Number of completes | Conversion rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot | 16/02/17 – 22/02/17 | 183 | 24 | 13 |

| Wave 1 | 28/03/17 – 27/04/17 | 505 | 90 | 18 |

| Wave 2 | 04/07/17 – 27/08/17 | 1,321 | 324 | 25 |

| Wave 3 | 18/10/17 – 07/12/17 | 1,462 | 310 | 21 |

| Wave 4 | 26/01/18 – 27/03/18 | 1,982 | 283 | 14 |

| Wave 5 | 08/05/18 – 09/06/18 | 1,548 | 203 | 13 |

| Wave 6 | 23/07/18 – 17/09/18 | 1,340 | 201 | 15 |

| Wave 7 | 26/11/18 – 01/05/19 | 56,013 | 14,748 | 26 |

| Wave 8 | 15/07/19 – 31/10/19 | 21,051 | 3,479 | 17 |

| Wave 9 | 06/01/20 – 31/01/20 | 359 | 107 | 30 |

| Total | 86,474 | 19,769 | 23 |

Table 1.4 shows the breakdown of sample and interview volumes, conversion rates and proportions of all completes by key subgroups. Due to participant and sample volumes, the vast majority of interviews were with ESF leavers (YEI and ESF leavers had similar response rates).

IP 1.1 accounted for the largest proportion of survey completes, followed by IP 2.1.

By CFO, the ESFA account for nearly three-quarters of sample completes due to participant and sample volumes. Unsurprisingly, HMPPS sample produced the lowest conversion rate; contact information was more likely to be invalid / out of date as many of these individuals had changed address etc. on leaving prison or their subsequent accommodation.

Table 1.5 Sample and interview volumes and response rates, by sample type, IP and CFO

| Subject | Starting sample (n) | Interviews achieved | Conversion rate (%) | % of all completes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type (st) YEI leavers | 10,054 | 2,213 | 22 | 11 |

| st ESF leavers | 77,364 | 17,556 | 23 | 89 |

| Investment Priority (IP) 1.1 (8i) | 24,646 | 7,387 | 30 | 37 |

| IP 1.2 (8ii ESF) | 13,024 | 2,177 | 17 | 11 |

| IP 1.3 (8ii YEI) | 10,054 | 2,213 | 22 | 11 |

| IP 1.4 (9i) | 11,241 | 2,048 | 18 | 10 |

| IP 2.1 (10iii) | 28,453 | 5,944 | 21 | 30 |

| CFO HMPPS | 4,160 | 286 | 7 | 1 |

| CFO DWP | 4,097 | 1,712 | 42 | 9 |

| CFO Direct provider | 13,735 | 3,151 | 23 | 16 |

| CFO NLCF | 1,345 | 399 | 30 | 2 |

| CFO ESFA | 64,081 | 14,221 | 22 | 72 |

Structure of the report

The remaining report chapters are structured as follows:

- Chapter 2 introduces the population profile, including the breakdown and interplay between sample type, demographics, investment priority and CFO. It also looks at the status of individuals on entry to provision in terms of demographics, employment, skills level and benefits claimed.

- Chapter 3 looks at experiences of the provision, including assistance for those with support needs, work-related skills gained and support/guidance provided, and overall satisfaction with the provision.

- Chapter 4 looks at what leavers are doing at the 6-point point and how this compares to what they were doing on entry to the programme. It identifies who had an improved labour market situation, as well as details of employment and training/education.

- Chapter 5 explores the job opportunities experienced by YEI leavers since leaving provision, including perceived quality and requirements for job roles offered.

- Chapter 6 provides conclusions.

- Appendix A is the Technical Appendix.

- Appendix B contains an overview (purpose, response rates) of the YEI leaver follow-up survey.

- Appendix C contains the full questionnaire.

- Appendix D contains the list of Direct Providers.

Reporting conventions

Unless otherwise stated, all differences commented on in this report are significant at the 95 per cent confidence level, meaning that we can be 95 per cent confident that a reported difference is a real one, as opposed to one resulting from the fact that we conducted a survey rather than a census of participants.

Data are not presented where unweighted base sizes are less than 50. In particular, this reduces the scope for YEI subgroup comparisons for some questions.

Differences by CFO have been highlighted throughout this report. However, any comparisons made in this way should be considered in the context of the varying nature of the provision delivered by the individual CFOs.

In the tables, the following conventions apply:

- ‘0’ zero

- ‘*’ greater than zero but less than 0.5 per cent

- ‘[x]’ figure to be treated with caution as base size less than 50

2. Demographics and status upon entry to provision

Understanding the population profile of leavers and the interplay between different groups is important when interpreting findings. This chapter explores characteristics of the population, for individuals who left provision in the relevant timeframe for this survey. This includes breakdowns by key groups (investment priority, CFO), demographics, and economic status on entry to the programme.

Chapter summary

ESF leavers (rather than YEI leavers) make up the vast majority of the population.

Leavers were most likely to fall under investment priorities (IPs) 1.1 and 2.1, and the Education & Skills Funding Agency CFO. CFOs focus on a particular IP or IPs; for example, HMPPS and National Lottery Community Lottery Fund are entirely focused on IP 1.4. In turn, there are demographic differences within IP, for example IPS 1.2 and 1.3 target younger people and all leavers were under 30 on entry, while participants from other IPs tended to be over 30. IP 2.1 had a notably lower proportion of disabled and/or disadvantaged leavers compared to other IPs.

Almost all YEI participants were either inactive or unemployed on entry to the programme, while three in ten ESF participants were in employment. As with demographics, there were patterns by IP in relation to economic status on entry, largely in line with the target audiences for each. The vast majority of IP 2.1 participants were employed on entry, in line with the priority’s objective to address the basic skills and increase the skills levels of individuals in work; this group make up the majority of individuals employed.

Disadvantaged individuals and those with a disability or long-term health condition showed lower rates of employment on entry and were more likely to be long-term unemployed than individuals without these characteristics.

The vast majority of participants in work on entry were “fully employed”, i.e. they were working full time or were working part-time and did not want to be working full time. Work tended to be paid and for an employer. Around two-thirds of these individuals working for an employer were in stable employment. Around half of unemployed individuals met the criteria for long-term unemployment.

2016-2018 population

MI showed that approximately 560,000 individuals completed ESF provision between December 2015 and December 2018, and just under 50,000 individuals completed a YEI provision between December 2015 and June 2019[footnote 11], as shown in Table 2.1.

Overall, Investment Priorities (IPs) 1.1 and 2.1 accounted for the greatest proportion of leavers. ESFA is by far the most prominent co-financing organisation (CFO), accounting for nearly three-quarters (72 per cent) of the population.

Table 2.1 Volume of leavers between December 2015 and June 2019, by IP and CFO

| Co-financing organisation | Total number of leavers | Proportion of population (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 609,972 | |

| ESF leavers | 560,208 | 92 |

| YEI leavers | 49,764 | 8 |

| Investment Priority 1.1 | 203,150 | 33 |

| Investment Priority 1.2 | 70,016 | 12 |

| Investment Priority 1.3 (YEI) | 49,764 | 8 |

| Investment Priority 1.4 | 114,417 | 19 |

| Investment Priority 2.1 | 172,625 | 28 |

| HMPPS | 24,046 | 4 |

| DWP | 49,006 | 8 |

| Direct Provider | 80,756 | 13 |

| NLCF | 19,299 | 3 |

| ESFA | 436,865 | 72 |

As shown in Figure 2.1, some CFOs are focused on particular IPs; for example, HMPPS and NLCF are entirely focused on IP 1.4 while the vast majority of DWP leavers fall into IP 1.1.

This means that many of the findings by CFO are likely to be related to differences by IP and their target audiences (demographic breakdowns by IP are explored in the next section of this chapter).

Figure 2.1 Investment Priority breakdown within CFO

| CFO | Base (All leavers) | IP 1.1 – % | IP 1.2 – % | IP 1.3 – % | IP 1.4 – % | IP 2.1 – % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All leavers | 19,769 | 33% | 11% | 8% | 19% | 28% |

| HMPPS | 286 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| DWP | 1,712 | 90% | 0% | 0% | 10% | 0% |

| Direct | 3,151 | 15% | 7% | 62% | 15% | 2% |

| NLCF | 399 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 100% | 0% |

| ESFA | 14,221 | 34% | 15% | 0% | 12% | 39% |

Base: All leavers (as shown)

Participant demographics

Table 2.2 presents the demographic breakdown of participants. Both overall and for ESF only and YEI only, participants were more likely to be male.

The most prominent difference between ESF only and YEI only participants was by age, largely due to age (being under 30) being a qualifying characteristic for YEI funded course/programme. As such, no YEI participants were over 30, while the majority of ESF participants were (60 per cent).

Although the majority for both, there was a slightly higher proportion of white participants among ESF participants (78 per cent compared to 73 per cent).

Table 2.2 Participant demographics, by sample type

| Sample type | All | ESF only | YEI only |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 58% | 58% | 60% |

| Female | 42% | 42% | 40% |

| Age on entry | |||

| 15 - 17 | 8% | 7% | 18% |

| 18 - 24 | 26% | 22% | 64% |

| 25 - 29 | 12% | 11% | 18% |

| 30-54 | 45% | 49% | 0% |

| 55+ | 10% | 11% | 0% |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 78% | 78% | 73% |

| BAME | 22% | 22% | 27% |

| Base | 19,769 | 17,556 | 2,213 |

Around two-thirds of the population (65 per cent) were disadvantaged; this was more common for YEI participants (73 per cent compared to 64 per cent ESF only). Individuals were classified as disadvantaged participants[footnote 12] if they:

- Lived in a ‘jobless household’[footnote 13];

- Were a single adult household with dependent children;

- Had no formal qualifications;

- Lacked basic skills[footnote 14];

- Were homeless/living in a hostel at start of provision;

- Were an ethnic minority; or

- Had drug or alcohol dependency at start of provision.

Two-fifths (37 per cent) had a disability or long-term health condition, although this was slightly less common among YEI participants (33 per cent compared to 37 ESF only).

Demographics by IP

There were some notable demographic differences by IP, most markedly by age, disadvantage and disability. All demographic differences are explored below.

Participants from IP 1.4 were more likely to be male (73 per cent) compared to all other IPs, while IPs 1.1 and 2.1 had the highest proportions of female participants (47 and 48 per cent, respectively).

Figure 2.2 IP by gender

| IP | Base (All leavers) | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 7,387 | 53% | 47% |

| 1.2 | 2,177 | 60% | 40% |

| 1.3 | 2,213 | 60% | 40% |

| 1.4 | 2,048 | 73% | 27% |

| 2.1 | 5,944 | 52% | 48% |

In line with their target audiences, leavers in IPs 1.2 and 1.3 were all aged under 30 years old on entry to the programme. The majority of participants in IPs 1.1, 1.4 and 2.1 were over 30 years old.

Figure 2.3 IP by age

| IP | Base (All leavers) | 15-17 | 18-24 | 25-29 | 30-54 | 55+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 7,387 | 2% | 20% | 12% | 51% | 15% |

| 1.2 | 2,177 | 49% | 51% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| 1.3 | 2,213 | 18% | 64% | 18% | 0% | 0% |

| 1.4 | 2,048 | 1% | 18% | 13% | 59% | 9% |

| 2.1 | 5,944 | 1% | 16% | 13% | 59% | 11% |

More than a quarter of participants in IPs 1.1-1.3 were BAME, compared to fewer than one in five in IPs 1.4 and 2.1.

Figure 2.4 IP by ethnicity

| IP | Base (All leavers) | White | BME |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 7,387 | 74% | 26% |

| 1.2 | 2,177 | 75% | 25% |

| 1.3 | 2,213 | 73% | 27% |

| 1.4 | 2,048 | 81% | 19% |

| 2.1 | 5,944 | 82% | 17% |

Participants in IP 2.1 were less likely than those in all other IPs to have a disability or long-term health condition or be disadvantaged (15 and 41 per cent). Conversely, those in IPs 1.1 and 1.4 had relatively high proportions of both.

Figure 2.5 Disability and disadvantaged within IP

| IP | Base (All leavers) | Disadvantaged | Disability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 7,387 | 79% | 48% |

| 1.2 | 2,177 | 62% | 35% |

| 1.3 | 2,213 | 73% | 33% |

| 1.4 | 2,048 | 72% | 54% |

| 2.1 | 5,944 | 41% | 15% |

Labour market characteristics

Just over half (56 per cent) of participants were unemployed and looking for work and 15 per cent were economically inactive on entry to the programme. Nearly one-third (29 per cent) were in employment.

In line with the provision’s focus on NEET individuals, a higher proportion of YEI participants – just over one-fifth (21 per cent) – were inactive on entry to their course/programme, and almost all others[footnote 15] were unemployed (78 per cent).

Entry status varied across IP and CFO, which one might expect given the different target audiences, themes and intended support provided under each.

The vast majority (92 per cent) of IP 2.1 participants were employed on entry, in line with the priority’s objective to address the basic skills and increase the skills levels of individuals in work; this group made up the majority of individuals employed. One in five (20 per cent) of participants under IP 1.2 were also employed on entry; employment rates across all other IPs were extremely low.

Owing to the CFO spanning all investment priorities and having a large proportion of participants under IP 2.1, the ESFA was the only CFO with a considerable proportion of participants employed on entry (40 per cent). HMPPS and DWP participants were the most likely to be economically inactive on programme entry (35 per cent and 34 per cent).

Figure 2.6 Employment status on programme entry, by sample type, Investment Priority and CFO

| Subject | Base (All leavers) | Inactive | Unemployed | In employment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type (st) YEI only | 2,213 | 21% | 78% | 1% |

| st ESF only | 17,556 | 14% | 54% | 32% |

| Investment Priority (IP) 1.1 | 7,387 | 15% | 84% | 2% |

| IP 1.2 | 2,177 | 26% | 54% | 20% |

| IP 1.3 | 2,213 | 21% | 78% | 1% |

| IP 1.4 | 2,048 | 23% | 76% | 1% |

| OIP 2.1 | 5,944 | 3% | 6% | 92% |

| CFO HMPPS | 286 | 35% | 64% | 1% |

| CFO DWP | 1,712 | 34% | 65% | 1% |

| CFO Direct | 3,151 | 26% | 70% | 4% |

| CFO NLCF | 399 | 28% | 71% | 1% |

| CFO ESFA | 14,221 | 9% | 51% | 40% |

| All leavers | 19,769 | 15% | 56% | 29% |

There were some entry status differences by key demographics:

- Gender: Men were more likely than women to be unemployed (60 per cent compared to 51 per cent), with a higher proportion of women in employment (33 per cent versus 26 per cent).

- Age: As might be expected, 15-17 year-olds were more likely than all other age groups to be inactive (42 per cent).

- Category of Region[footnote 16] The proportion of participants from less developed regions in employment was more than double that of participants from transitional or more developed regions (64 per cent versus 31 and 28 per cent).

- Disadvantaged: Disadvantaged participants were far less likely to be employed on entry (18 per cent versus 50 per cent not disadvantaged).

- Disability: One in nine participants (11 per cent) with a disability or long-term health condition were employed on entry, compared to two-fifths (40 per cent) of participants without.

- Ethnicity: White participants were more likely to be employed than their BAME counterparts (31 per cent compared to 22 per cent).

Overall, four per cent of participants were in training or education on entry to the programme. Most of these individuals were in college (56 per cent), typically full time (45 per cent of all in education). Just under one-third (31 per cent) were in school.

Employed on entry[footnote 17]

More than four-fifths (82 per cent) of participants who were employed on entry were working for an employer in a paid role. One in ten (10 per cent) were self-employed.

A small minority – six per cent – were employed as an apprentice; this increased to half (50 per cent) among participants aged 15-17.

Around three-quarters (74 per cent) of all employed participants were working full time. Men were more likely to be working full time (84 per cent compared to 63 per cent of women). The vast majority (90 per cent) of participants in work on entry were “fully employed”, i.e. they were working full time or working part-time and did not want to be working full time.

As shown in Figure 2.7, nearly two-thirds (65 per cent) of individuals working for an employer were doing so in ‘stable employment’, i.e. they were on a permanent or open-ended contract. Around one in five (21%) were in precarious employment and 13 per cent were in employment of unknown stability. Likelihood of being in stable employment increased with age, from 51 per cent among 15-17 to 80 per cent for 55+.

Figure 2.7 Hours worked, type of employment and employment contracts – this figure is made up of 3 charts

Type of employment contract

| Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Stable employment | 65% |

| Precarious employment | 21% |

| Unknown stability | 13% |

Base (All in employment except self-employed on entry) – 9,671

Type of employment

| Type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Self-employed | 9% |

| Employer in paid role | 86% |

| Apprenticeship | 5% |

Base (All in employment at six months) – 10,595

Hours working

| Hours | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Full-time | 72% |

| Part-time | 28% |

| Unknown | 1% |

Base (All in employment at six months) – 10,595

Unemployed but looking for work on entry

Around half of unemployed participants (53 per cent) had been out of paid employment and looking for work for at least six months when they started the programme, with two-fifths (39 per cent) looking for at least a year. Eight per cent had never had a job.

Overall, just over half (52 per cent) of unemployed individuals were long-term unemployed, meaning they were either under the age of 25 and had been looking for work for at least 6 months or over the age of 25 and had been looking for work for 12 months. Long-term unemployment was slightly less common among YEI only participants (50 per cent).

Among those unemployed, women were slightly more likely to have been long-term unemployed on entry (55 per cent compared to 50 per cent of men).

As well as showing lower rates of employment overall, among those unemployed disadvantaged individuals and those with a disability or long-term health condition were more likely to be long-term unemployed than individuals without these characteristics (55 versus 44 per cent and 61 versus 45 per cent, respectively), demonstrating the difficulties these participants face gaining employment.

Barriers to work

The majority (85 per cent) of participants unemployed on entry cited a prospect- or logistic-related barrier to work. As shown in Figure 2.8, lack of recent working experience and/or availability of jobs were the most common prospect-related barriers to work, both cited by nearly half (48 per cent) of all unemployed participants. Concern around lack of recent experience was more common among YEI participants (59 per cent versus 47 per cent ESF only).

Figure 2.8 Prospect – and logistical barriers to work for the unemployed

| Barriers | YEI only | ESF only | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Issues with citizenship/visa status | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Alcohol/drugs dependency | 2% | 4% | 3% |

| Criminal convictions | 4% | 9% | 9% |

| Caring responsibilities | 14% | 18% | 18% |

| Problems with transport or the cost of transport | 32% | 31% | 31% |

| Didn’t have right qualifications or skills | 40% | 40% | 40% |

| Few jobs available where you lived | 49% | 47% | 48% |

| Lack of recent experience of working | 59% | 47% | 48% |

| None of the above | 12% | 15% | 14% |

Base: All unemployed: YEI only – 1,706, ESF only – 9,374, All – 11,080

Barriers related to personal characteristics were less common overall, with just under half (49 per cent) of unemployed individuals facing no barriers in this regard. This proportion was higher among YEI participants (64 per cent). Reasons such as disability/problems with health or age were far more prominent among ESF participants, as shown in Figure 2.9.

Figure 2.9 Personal characteristic barriers to work for the unemployed

| Barrier | YEI only | ESF only | All |

|---|---|---|---|

| Your gender (including gender reassignment) counted against you | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Your religion or belief counted against you | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Your sexual orientation counted against you | 1% | 1% | 1% |

| Your ethnicity or race counted against you | 2% | 4% | 3% |

| You were pregnant or had a young baby | 5% | 4% | 4% |

| Your age counted against you | 15% | 24% | 23% |

| You had a disability or problems with your health | 18% | 31% | 30% |

| None of the above | 64% | 49% | 51% |

Base: All unemployed: YEI only – 1,706, ESF only – 9,374, All – 11,080

Benefits claimed on entry

Just over four-fifths (83 per cent) participants on DWP CFO provision were on state benefits on entry. This proportion was higher among:

- IP 1.4 (92 per cent compared to 82 per cent in IP 1.2);

- Disadvantaged participants (85 per cent compared to 76 per cent not);

- Individuals with a long-term health condition or disability (85 per cent compared to 76 per cent without)

Most commonly, DWP participants were claiming Jobseeker’s Allowance (50 per cent of all entering DWP provision). Employment Support Allowance and Universal Credit were also relatively common (15 and 12 per cent, respectively).

Figure 2.10 Benefits claimed on entry, among DWP leavers

| Benefits | At entry |

|---|---|

| Don’t know | 2% |

| Other | 0% |

| Council Tax Benefit | 0% |

| Carers Allowance | 0% |

| Child Benefit | 1% |

| Housing Benefit | 2% |

| Incapacity Benefit | 2% |

| Tax Credit | 2% |

| Personal Independence Payment (PIP) | 3% |

| Income Support | 4% |

| Disability Living Allowance (DLA) | 4% |

| Universal Credit | 12% |

| Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) | 15% |

| Jobseeker’s Allowance | 50% |

Base (All DWP leavers) 1,712

3. Course/programme experience

This chapter presents findings on how leavers found the course/programme they attended. It explores views on provision guidance and relevance, and its impact on work-related skills. It also presents findings for individuals with specific support needs, i.e. leavers who had childcare or other caring responsibilities, and those with a long-term health condition; whether these needs were supported and experience in this regard. The chapter concludes with a focus on the traineeship experiences among YEI leavers.

Chapter summary

Views on the provision were generally very positive. Most leavers were satisfied with the information provided about and as part of their provision, and felt the provision was relevant to their specific needs. More than three-quarters of leavers felt courses/programmes were pitched at the right level of difficulty and were about the right length.

Leavers tended to report positive impacts of the provision on job prospects. The vast majority of participants who were employed on entry to the provision felt it had helped them in the work environment, while a similar proportion of unemployed participants felt it had helped move them into or nearer to employment.

BAME, disadvantaged leavers and leavers with a long-term health condition were more likely to receive job search advice/guidance, but BAME leavers were the only group among these to be more likely to cite related benefits (such as improved self-confidence and communication skills) as a result.

Younger participants were also more likely to have received job search advice/support through the provision and report work-related benefits. IPs focused on younger participants (IP 2.1 and IP 1.3) showed similar patterns.

Participants with caring responsibilities (for a child or otherwise) were rarely offered support or assistance in this regard through their provider. Offers and uptake of support was more common among participants with a long-term health condition or disability. Regardless of support need, the vast majority of individuals who received assistance were satisfied with the support, and around three-quarters felt they would have faced difficulties attending the provision without it.

Views on the programme

Course/programme design

Guidance and relevance

Programme leavers were broadly satisfied with guidance for and relevance of their provision. Specifically, around nine in ten were satisfied with the information and guidance they received on what would be delivered through the programme (88 per cent), the feedback and guidance they received during the programmes (87 per cent), and the relevance of the programme to their specific needs (86 per cent).

Except for YEI leavers being slightly more satisfied with the relevance of the programme (88 per cent compared to 85 per cent of ESF leavers), satisfaction was broadly aligned between these two groups (see Figure 3.1).

As shown in Figure 3.1, leavers in IP 2.1 were more likely to be satisfied with all guidance and relevance, while those in IP 1.1 and 1.4 showed lower satisfaction than average. By CFO, DWP participants showed lower levels of satisfaction for all three questions relating to guidance and support.

Figure 3.1 Proportion satisfied with programme aspects by sample type, IP and CFO

| Subject | All leavers | Satisfied with relevance of support | Satisfied with feedback/guidance during programme | Satisfied with guidance/info on what will be delivered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample type (st) YEI only | 2,213 | 88% | 87% | 89% |

| st ESF only | 17,556 | 85% | 87% | 88% |

| st All leavers | 19,769 | 86% | 87% | 88% |

| Investment Priority (IP) 1.1 | 7,387 | 82% | 84% | 86% |

| IP 1.2 | 2,177 | 88% | 89% | 89% |

| IP 1.3 | 2,213 | 88% | 87% | 89% |

| IP 1.4 | 2,048 | 81% | 84% | 86% |

| IP 2.1 | 5,944 | 91% | 91% | 92% |

| CFO HMPPS | 286 | 81% | 82% | 86% |

| CFO DWP | 1,712 | 79% | 81% | 84% |

| CFO Direct | 3,151 | 86% | 86% | 88% |

| CFO NLCF | 399 | 85% | 88% | 89% |

| CFO ESFA | 14,221 | 87% | 88% | 89% |

Leavers from less developed regions were generally more satisfied than average: 94 per cent expressing satisfaction for the guidance on what would be delivered and the relevance of the provision, and 95 per cent were satisfied with the feedback and guidance given during the course/programme.

Overall, seven per cent of leavers were dissatisfied with all three elements of the provision. Leavers with slightly higher dissatisfaction levels included:

- Those disadvantaged (eight per cent versus five per cent non-disadvantaged)

- BAME (eight per cent versus six per cent among white people)

- Disabled participants (nine per cent compared to five per cent among those without a disability or long-term health condition)

Course/ programme difficulty

More than three-quarters of all leavers (78 per cent) thought the difficulty of the provision was ‘about right’. Six per cent thought it was ‘too difficult’ and 13 per cent ‘too easy’. Results were similar for the amount of time spent on the course/programme and the amount of support received; 78 per cent said this was ‘about right’, nine per cent ‘too much’ and 11 per cent ‘too little’.

Figure 3.2 Participant views on level of difficulty and amount of time on programme – this figure is made up of 2 charts

Level of difficulty of programme

| Level | Percentage |

|---|---|

| About right | 78% |

| Too difficult | 6% |

| Too easy | 13% |

| Don’t know | 3% |

Base (All leavers) 19,769

Amount of time on programme or support received

| Level | Percentage |

|---|---|

| About right | 78% |

| Too much | 9% |

| Too little | 11% |

| Don’t know | 2% |

Base (All leavers) 19,769

ESF participants were slightly more likely than YEI participants to find the provision too difficult (six per cent versus four per cent). By CFO, DWP and National Lottery Community Fund (NLCF) participants were the most likely to find it too difficult (both eight per cent). Among IPs this measure was highest for 1.1 (eight per cent) and 1.4 (seven per cent).

The proportion of participants that found the course/programme too difficult rose with age, from two per cent of 15-17 year olds to nine per cent among 55+ year olds.

Generally, satisfaction with time and support on the programme was consistent across different leaver groups. The groups most likely to report they received too little time and support included HMPPS (18 per cent) and NLCF (16 per cent) participants, and those under IP 1.4 (14 per cent).

Participants living with a disability or a long-term health condition were more likely than those without to say they received insufficient time/support (14 per cent compared to nine per cent). Similarly, BAME participants were slightly more likely than white participants to report the same (13 per cent versus 10 per cent), as were disadvantaged participants compared to non-disadvantaged (12 per cent versus nine per cent).

Participants with support needs

A significant minority of participants entered the programme with additional responsibilities outside of work or were living with a long-term health condition. Just over a quarter (27 per cent) had parental/guardianship responsibilities for children under 18. A similar proportion (26 per cent) had a mental or physical health condition, or illness expected to last 12 months or more. A slightly smaller proportion (eight per cent) had caring responsibilities for a family member, relative or friend.

As could be expected given the focus of YEI on young people, participants under this programme were far less likely than those under ESF to have parental responsibilities at programme entry (14 per cent versus 29 per cent). As shown in Figure 3.3, they were also slightly less likely to be living with a long-term health condition (23 per cent versus 27 per cent).

Participants under IP 1.2 (four per cent) and 1.3 (14 per cent) were less likely than average to be parents, whereas two-fifths (40 per cent) of 2.1 participants were parents or guardians.

By CFO a slightly smaller proportion of DWP (19 per cent) and Direct Provider (17 per cent) participants were parents compared to 30 per cent of ESFA participants.

Participants under IP 1.1 and 1.4 were more likely to be carers (10 and 11 per cent, respectively) and/or have a disability or long-term condition (35 and 42 per cent, respectively).

Approaching two-thirds of DWP participants (63 per cent) had a long-term health condition at programme entry, far higher than any other CFO, although this was also the case for significant minorities under HMPPS (44 per cent) and the NLCF (41 per cent).

Figure 3.3 Proportion of participants with responsibilities outside work or a long-term health condition by CFO and IP – this figure is made up of 3 charts

Sample type

| Sample type | Base (All leavers) | Long-term health condition | Caring responsibilities | Childcare responsibilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEI only | 2,213 | 23% | 6% | 14% |

| ESF only | 17,556 | 27% | 8% | 29% |

| All leavers | 19,769 | 26% | 8% | 27% |

Investment Priority

| Investment Priority | Base (All leavers) | Long-term health condition | Caring responsibilities | Childcare responsibilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | 7,387 | 35% | 10% | 28% |

| 1.2 | 2,177 | 19% | 5% | 4% |

| 1.3 | 2,213 | 23% | 6% | 14% |

| 1.4 | 2,048 | 42% | 11% | 27% |

| 2.1 | 5,944 | 9% | 6% | 40% |

Co-financing Organisation (CFO)

| CFO | Base (All leavers) | Long-term health condition | Caring responsibilities | Childcare responsibilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMPPS | 286 | 44% | 9% | 25% |

| DWP | 1,712 | 63% | 9% | 19% |

| Direct | 3,151 | 31% | 7% | 17% |

| NLCF | 399 | 41% | 13% | 24% |

| ESFA | 14,221 | 20% | 8% | 30% |

As shown in Figure 3.4, there was much variation in responsibilities by demographic, and in terms of long-term health condition or illness. More than a third of women (37 per cent) had parental responsibilities at programme entry compared to one in five men (21 per cent). They were also slightly more likely to have caring responsibilities (10 per cent versus seven per cent). As could perhaps be expected, the older the participant the more likely they were to have a long-term health condition or illness; around one in six (16 per cent) 15-17 year olds had one rising to more than a third (35 per cent) among 55+ year olds.

Figure 3.4 Proportion of participants with responsibilities outside work or a long-term health condition by age and gender

| Gender/age | Base (All leavers) | Long-term health condition | Caring responsibilities | Childcare responsibilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 19,769 | 26% | 8% | 27% |

| Males | 10,977 | 27% | 7% | 21% |

| Females | 8,783 | 26% | 10% | 37% |

| 15-17 | 1,649 | 16% | 4% | 2% |

| 18-24 | 5,254 | 22% | 6% | 9% |

| 25-29 | 2,317 | 24% | 7% | 32% |

| 30-54 | 8,325 | 29% | 10% | 46% |

| 55+ | 2,224 | 35% | 10% | 8% |

BAME participants were slightly more likely than white participants to have parental responsibilities (35 per cent versus 25 per cent), slightly more likely to be carers (nine per cent versus eight per cent) but less likely to be living with a long-term condition (18 per cent versus 29 per cent).

Support provided

Most participants (91 per cent) with childcare responsibilities were not offered support or assistance from their provider in relation to these responsibilities. Four per cent received support and a further three per cent were offered support but did not take it up[footnote 18].

Of those that received support, nine in ten (90 per cent) were satisfied with the support they received, with just five per cent not satisfied. Almost three-quarters (73 per cent) said that they would have faced difficulties attending the provision or support programme without the support they received for childcare. This is summarised in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5 Experience of childcare support on programme – this figure is made up of 3 charts

Childcare support

| Base (All with childcare responsibilities at entry) | Refused to say | Not offered support | Was offered support | Received support |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5,391 | 1% | 91% | 3% | 4% |

Satisfaction with support for childcare responsibilities

| Satisfaction | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Satisfied | 90% |

| Not satisfied | 5% |

| Don’t know | 4% |

| Refused | 0% |

Base (All who received childcare support) 221

Difficulties attending without childcare support

| Difficulties | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Yes | 73% |

| No | 24% |

| Don’t know | 2% |

| Refused | 0% |

Base (All who received childcare support) 221

Participants on a YEI programme were most likely to receive childcare support (12 per cent) or to have been offered support (10 per cent). This compared to three per cent receiving support and three per cent being offered under ESF.

Similar to childcare, most participants with caring responsibilities (88 per cent) were not offered support or assistance from their provider. Six per cent received support while five per cent were offered support but didn’t use it. Only a very small number of participants (89) were asked about their satisfaction with this support, but indicative results suggest the vast majority were satisfied (97 per cent) and they would have had difficulty attending without it (73 per cent).