Digital Lifeline: A qualitative evaluation

Published 24 March 2022

Ministerial foreword from Rt Hon Nadine Dorries MP, Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport

Technology is now an integral part of everyday life — a fact that was made even starker when the COVID-19 pandemic forced the world online during lockdown. So it’s incredibly important that everyone in the UK has the digital skills and access to reap the benefits of being online and to participate fully in society. We want to ensure no one is left behind by the digital revolution, no matter what challenges they face.

In February 2021 we launched a £2.5 million Digital Lifeline Fund to reduce the digital exclusion of people with learning disabilities. The fund provided free devices, data and digital support to over 5000 people with learning disabilities who can’t afford to get online. The aim of the programme was to use digital inclusion to reduce the disproportionate negative effects of COVID-19 on people with learning disabilities, such as loneliness and lack of contact with support networks.

As this report shows, the fund has already had a hugely positive impact. Overall, 5,500 people have been given a tablet, as well as ongoing support to provide them with the basic skills and confidence to use it. Months later, our survey showed that most people were still using their tablet regularly to connect with friends and family, pursue hobbies and interests, keep themselves active and learn. Over half were using it once a day. Moreover, 91% of recipients experienced at least one benefit from the Digital Lifeline after 4 weeks, including feeling more confident, more connected, less lonely and that their digital skills had improved.

These results are testament to the value of offering support alongside the provision of devices, empowering individuals to be digitally active. I am proud of Digital Lifeline’s achievements, and thank Good Things Foundation for their support and delivery to make this such a successful project, which has made huge progress against my personal goal of ensuring that everyone in the UK has access to the benefits of the digital age.

Rt Hon Nadine Dorries MP

Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport

Foreword from Helen Milner, OBE, Chief Executive, Good Things Foundation

Digital Lifeline has been an overwhelming success and a true collaborative partnership programme. Together with our national and community partners we’ve exceeded our goal by far. The speed at which the programme was delivered was exceptional, reaching 5,500 digitally excluded people with learning disabilities in just a few months.

Nine in ten people supported say their lives have already got better, whether through helping them connect with loved ones, or friendship and support groups, or growing their confidence when online.

Thank you to our 146 community partners. Thank you to our national partners: AbilityNet, Learning Disability England, VODG: Voluntary Organisations Disability Group, and Digital Unite. And thank you to the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport for funding this life-changing initiative.

The pandemic exposed a deep digital divide. Digital Lifeline shows the benefits, but too many people with learning disabilities and disabled people are still left behind. It is time to fix the digital divide.

Helen Milner, OBE

Chief Executive, Good Things Foundation

Executive summary

Digital Lifeline aimed to use digital inclusion to alleviate the negative impacts of COVID-19 on people with learning disabilities by supplying 5,500 people with a Lenovo M10 tablet, 24GB data and basic digital skills training.

Digital Lifeline was an emergency response to COVID-19, which addressed a clear and pressing need. Without access to the internet during the pandemic, many people with learning disabilities experienced worsening mental and physical health; increased social isolation; and difficulty accessing essential services (ONS 2021; Seale 2020).

The programme was funded by the Department for Digital, Culture Media and Sport (DCMS), and delivered by Good Things Foundation, 146 community and coordination partners, and four specialist partners (AbilityNet, Digital Unite, Learning Disability England and Voluntary Organisations Disability Group).

In order to evaluate the short term impact of the programme, data was collected at baseline (when a beneficiary received their device), and around 2-4 weeks later. An Interim Report based on this data was published in September 2021. A qualitative evaluation was also commissioned to explore the longer term impact of Digital Lifeline. The qualitative evaluation aimed to:

-

Identify what constitutes meaningful digital inclusion support for people with learning disabilities;

-

Identify the ways in which this type of intervention supports the wider policy aim of reducing digital exclusion among people with learning disabilities;

-

Provide recommendations that inform organisations how to provide effective digital inclusion support for people with learning disabilities.

The findings from the evaluation demonstrate that Digital Lifeline has been a success, and highlight the considerable gains that can be achieved through true partnership working. Together, DCMS, Good Things Foundation, and its programme partners have delivered significant benefits for people with learning disabilities. Digital Lifeline has also shown what people with learning disabilities are able to achieve when given the right support.

Digital Lifeline has:

-

Provided 5,500 people with learning disabilities with vital access to a device, data and assistive technology, which, in turn, has helped them to access online products and services that they would otherwise not have been able to access; 91% of beneficiaries surveyed in the first few weeks reported at least one positive outcome.

-

Enabled people with learning disabilities to participate more fully in their local community and society. Through the digital skills support provided, beneficiaries have developed the confidence and ability to use their tablet to speak to friends and family, learn new things, engage with their hobbies and interests, and participate in community activities. When surveyed, 64% of beneficiaries agreed that their digital skills had improved, and the qualitative evaluation confirmed that beneficiaries had continued to build their digital skills in the months following. Learning digital skills also helped some people feel empowered to try new things.

-

Helped to mitigate, or reduce, inequalities that people with learning disabilities experience in other areas of their lives. Receiving a tablet has helped to reduce social isolation and feelings of loneliness by helping beneficiaries to maintain, deepen, or forge new connections with others. When surveyed, 52% of beneficiaries agreed that they felt less lonely as a result of receiving the device. Increased connection was also a key theme from the qualitative evaluation. People explained that receiving the device has helped them to feel happier, and more relaxed. Having a tablet also helped some to stay more active; 43 of the 57 beneficiaries we spoke to said they used their tablet for entertainment or doing fun activities.

-

Brought visibility to the needs and barriers faced by people with learning disabilities. Through the collection of baseline and impact data, and the qualitative data collected as part of this evaluation, Digital Lifeline has helped to fill some of the gaps in knowledge relating to the experiences of digitally excluded people with learning disabilities.

[Data source: An impact survey was completed by beneficiaries 2—4 weeks after receiving the device. It covered questions on: hours of support received/provided; skills achieved and other outcomes. 4,759 beneficiaries completed impact surveys.]

The learnings from this evaluation are useful to policy-makers, funders and practitioners, and highlight a number of factors that are essential for providing meaningful digital skills support to people with learning disabilities:

-

a long term connectivity solution that is affordable, and suitable for a person’s needs

-

a device that is given, not loaned

-

support to get online, provided by a trusted organisation or person

-

one-to-one support in the initial stages of digital learning

-

personalised support that takes into account the needs of the individual

-

ongoing support to repeat and build learning

-

using ‘hooks’ (such as hobbies or interests) to encourage engagement

-

using specialist support and assistive technology to aid learning

-

encouraging people to take ownership of their learning

-

support to help people and their support networks to stay safe online

-

including families, carers and support workers in digital skills training

Alongside the successes of Digital Lifeline, this evaluation has also highlighted that further intervention is needed in order to promote digital inclusion among people with learning disabilities.

1. Recommendations for policy makers

-

Embed digital inclusion into government policies and programmes to improve the lives of people with learning disabilities and disabled people more generally.

-

Promote digital inclusion for those at most risk of being left behind in the new Digital Strategy — such as disabled people and people with learning disabilities.

-

Recognise the value of community-based learning and development, and fund community organisations to help people build confidence and learn digital skills simultaneously.

-

Take action to reduce data poverty and address barriers to device ownership.

-

Address the data and knowledge gap in relation to people with learning disabilities. We still do not know enough about the digital experiences and barriers faced by people with learning disabilities and how this relates to wider characteristics of the population of people with learning disabilities.

2. Recommendations for funders

-

Take action to ensure that the beneficiaries supported through Digital Lifeline can continue to develop their skills.

-

Fund more, and longer term, digital inclusion programmes to support people with learning disabilities.

-

Invest in improving the digital access, skills and confidence of the social care workforce, disabled people’s organisations and self advocacy groups.

-

Provide funding to improve the digital access, skills and confidence of family members and informal carers, so they can, in turn, help the people they support to get online.

3. Recommendations for practitioners

-

Identify and address any organisational barriers to delivering digital inclusion support — such as gaps in digital infrastructure and/or a lack of digital confidence, motivation, and skills among staff and volunteers.

-

Support staff / volunteers to be confident in encouraging people with learning disabilities to explore the full potential of the internet.

-

Provide clear, accessible information about what digital and data support is being provided to avoid confusion.

1. Introduction

Being online has been a lifeline for many people during the pandemic. However, this has not uniformly been the case for the large number of people with learning disabilities many of whom are digitally excluded. Fifteen percent of disabled people have never been online, and 35% of people with learning or memory disabilities do not have the Essential Digital Skills for Life. Without access to the internet many people with learning disabilities have experienced worsening mental and physical health; increased social isolation; and difficulty accessing essential services (ONS 2020; ONS 2021; Seale 2020; Lloyds Bank 2021b).

Digital Lifeline was an emergency response to this clear and pressing need, providing 5,500 people with learning disabilities with a Lenovo M10 tablet, 24GB of data, and support to use the tablet and make it more accessible. Devices, data and support were provided to people with a learning disability who were over 18, living in England, and digitally excluded. The programme was open to people living independently in the community, in supported living, or with family carers. The programme was funded by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), and delivered by Good Things Foundation, AbilityNet and other programme partners.

Since March 2020 Good Things Foundation had successfully delivered ‘Everyone Connected’ (formerly DevicesDotNow) — securing donations to distribute devices, data connectivity and digital skills support to people who needed it. This ‘Everyone Connected’ model was the basis for the design of Digital Lifeline.

In delivering Digital Lifeline, Good Things Foundation led on partnership and project management; data collection and analysis; and recruitment, training and support for community partners. Good Things Foundation was supported in delivering Digital Lifeline by three categories of programme partners. Community partners identified eligible beneficiaries; distributed the devices and data to beneficiaries; and provided digital skills support to beneficiaries. Coordination partners assisted delivery; and received an additional grant payment to cover coordination costs (including engagement with beneficiaries, and the receipt, delivery and set-up of the devices on a larger scale). Specialist partners (AbilityNet, Digital Unite, Learning Disability England and Voluntary Organisations Disability Group) provided specialist support to beneficiaries, community partners, and coordination partners.

In order to evaluate the short term impact of the programme, data was collected at baseline (when a beneficiary received their device), and around 2—4 weeks later. The baseline survey collected information about demographics, goals and barriers. The early impact survey collected information about the type of support that had been provided, the skills that had been gained and other outcomes that had been achieved. Community partners were also invited to provide feedback on their experience delivering the programme via a short survey. An Interim Report based on this data was published in September 2021 (Good Things Foundation 2021a).

Digital Lifeline was set up as an emergency response, for delivery within a very tight timeframe. Therefore, while the data presented in the Interim Report is a helpful indication of impact, it is likely that it is an underestimate of what has been achieved through Digital Lifeline. For this reason, a qualitative evaluation was commissioned to explore the longer term impact of Digital Lifeline.

The qualitative evaluation took place between June and October 2021, and was led by Good Things Foundation, University of East London and RIX Social Researchers (peer researchers with learning disabilities).

The qualitative evaluation aimed to:

-

Identify what constitutes meaningful digital inclusion support for people with learning disabilities.

-

Identify the ways in which this type of intervention supports the wider policy aim of reducing digital exclusion among people with learning disabilities.

-

Provide recommendations that inform organisations how to provide effective digital inclusion support for people with learning disabilities.

This report explores the findings from this qualitative evaluation. The findings are based on:

-

a review of current academic, grey and policy literature;

-

focus groups and interviews with the people who received devices;

-

focus groups with the families / carers of those that received devices;

-

interviews with community partners who delivered devices, data and support.

For more information, see the methodology section of this report.

2. The context

2.1 What is a learning disability and how common is it within the UK?

A learning disability affects the way a person learns new things throughout their lifetime; it also affects the way a person understands information and how they communicate. People with learning disabilities can have difficulty understanding new or complex information, learning new skills and coping independently (NHS.co.uk n.d.). There are different types of learning disability which can be mild, moderate, severe or multiple and profound. The type of learning disability that a person has can impact the level of support they need (Mencap n.d.).

Data collected about the size and characteristics of the population of people with learning disabilities is inconsistent and incomplete. However, it is estimated that 1.5 million living in the UK have a learning disability (Mencap n.d.). An estimated 1.13 million people with learning disabilities in the UK are adults and 351,000 are children (Mencap n.d.).

2.2 What is digital exclusion?

Digital exclusion is about not having the access, skills, motivation or confidence to use the internet and benefit from the opportunities that digital provides (Good Things Foundation 2021c):

-

Digital access: A person may be digitally excluded because they do not have an internet connection; do not have an appropriate device; do not have access to the assistive technology they need; or cannot afford to pay for a connection, device, or assistive technology.

-

Digital skills: A person can be digitally excluded if they do not have the digital skills to get online. The Essential Digital Skills Framework outlines three categories of digital skills that a person may need. ‘Digital Foundation Skills’, underpin all essential digital skills (and include things like being able to turn on a device). ‘Essential Digital Skills for Life’, and ‘Essential Digital Skills for Work’ are the skills needed in a personal and work context in relation to: communicating, handling information and content, transacting, problem solving and being safe and legal online (Department for Education, 2019).

-

Digital motivation: A person can also become digitally excluded if they are not motivated to get online.

-

Digital confidence: A person may be digitally excluded if they do not have the self belief to be able to learn the skills they need to use the internet safely and effectively.

2.3 How does digital exclusion impact people with learning disabilities?

Disabled people make up a disproportionate number of those that do not have access to the internet. In figures released in 2020, the ONS estimated 15% of disabled people have never been online, whereas this figure was 3% among non-disabled people (ONS 2020). Among those with learning disabilities, digital access is unevenly distributed. Flynn et al. (2021) reported that people with profound and multiple learning disabilities have generally lower levels of internet access (57%) than people with learning disabilities who do not have profound and multiple learning disabilities (74%).

Poor accessibility can prevent disabled people from accessing the internet; and although more content is being designed to be accessible across devices, there is still evidence that a lack of online accessibility is a barrier for disabled people (Disability Unit 2021; Good Things Foundation 2016, Roscoe and Johns 2021; Scope 2020). Assistive technologies can be very helpful in making devices and technology more accessible. However the latest Lloyds Bank UK Consumer Digital Index (2021a) found that these technologies are more likely to be used by people with already high or very high digital engagement, and are therefore being underused by those that could benefit the most from them. The barriers which may stop disabled people from using assistive technologies include: cost; a lack of awareness, inadequate assessment, and insufficient funding (Boot et al. 2018; Department for Work and Pensions, Disability Unit, Equality Hub 2021).

Alongside lower levels of access, disabled people are also less likely to have the Essential Digital Skills they need than the UK population as a whole: 35% of people with learning or memory disabilities do not have the Essential Digital Skills for Life; and 47% of people with a learning or memory disability do not have the Essential Digital Skills for Work. In the UK population as a whole these figures are 21% and 36%, respectively (Lloyds Bank 2021b).

People with learning disabilities can also feel less motivated and less confident about going online due to previous negative learning experiences; a fear of admitting gaps in their knowledge; and negative attitudes towards disabled people in society more generally (Chadwick, Wesson and Fulwood 2013; Good Things Foundation 2018). Online safety may also be a concern for people with disabilities - as it is for many people more generally (Stone, Llewellyn and Chambers 2020).

People with learning disabilities can need personalised and long term support in order to grow their digital skills, motivation and confidence (Good Things Foundation 2018; Newman et al. 2016). However, this type of support is not always readily available. Many people with learning disabilities can miss out on the life-enriching experiences that the internet provides because their carers, support workers or families are not willing, or able, to support them to use the internet (Bradley 2021; Chadwick, Wesson, Fulwood 2013; Chadwick, Quinn and Fullwood 2016; Good Things Foundation 2016; Newman et al. 2016; Seale 2020).

2.4 Why is digital inclusion important for people with learning disabilities?

It is important to promote digital inclusion among people with learning disabilities to:

-

Facilitate access to essential goods and services: Society is becoming increasingly digital, and the ability to access public, voluntary and commercial goods and services is becoming more dependent on the ability to access and use the internet. Promoting digital inclusion is essential to ensuring people with learning disabilities are not locked out from accessing their basic rights and needs.

-

Promote active participation within society: Digital inclusion is not just about being able to access the opportunities that the internet affords, but also being able to make the most of them. In this context, supporting people with learning disabilities to make more of the potential of the internet is vital for them to be able to ‘participate, and live well and safely in a digital world’ (Stone 2021).

-

Engender visibility and recognition in data driven decision-making: Digital progress has meant that we are not just living in a digital society, but also a data society. In the context of algorithmic decision-making and online consultation, reducing digital exclusion is vital to ensuring that the needs of people with learning disabilities are surfaced and acted upon (Dencik, Hintz and Redden 2019; Ada Lovelace Institute 2021; Flynn et al 2021).

-

Reduce, or mitigate, wider inequalities: Analysis of the demographics of internet usage has demonstrated a clear association between digital exclusion and other forms of exclusion (Yates et al. 2020). Therefore, it is important to promote digital inclusion, not just as an end in its own right, but as a way to minimise and address the wider inequalities that people with learning disabilities face.

2.5 The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

The impact of the pandemic has been disproportionately severe for people with learning disabilities, both in terms of mortality rate from the virus itself, and also due to the impact of lockdown and the requirement to shield (House of Commons, 2021). The higher rates of digital exclusion among people with learning disabilities were a contributory factor in this.

During the pandemic, many health services were only available online, and whilst some people with learning disabilities were able to use technology to access these services, many were unable to do so due to barriers such as lack of digital skills, a lack of in-home support and lack of access to technology or the internet (Cebr 2021; Sense 2021; Seale 2020). This had serious consequences for their physical and mental health. The ONS (2021) reports that disabled people were more likely to say that coronavirus had affected their health (35% for disabled people, compared with 12% for non-disabled people); their access to healthcare for non-coronavirus related issues (40% compared with 19%); and their wellbeing (65% compared with 50%).

Digital barriers also impacted the extent to which people with learning disabilities were able to connect with others, and access support during the pandemic. While many people relied on online video calling and social media platforms to connect with others during lockdown, this opportunity was not available to the high proportion of people with learning disabilities without the access, skills, confidence or motivation to use the internet. Seale (2020) reports that many people with learning disabilities found themselves disconnected from their family, friends, community and support services during the pandemic. This reduction or removal of support increased social isolation and uncertainty, and contributed to increased feelings of loneliness, and worsening mental and physical health among people with learning disabilities (Scottish Commission for Learning Disability 2020; Seale 2020).

2.6 What actions are being taken to address digital exclusion experienced by people with learning disabilities?

2.6.1 What policy responses have there been?

Digital Lifeline was set up by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport as part of a cross-cutting Government response to addressing the disproportionately negative effects of COVID-19 on people with learning disabilities. It was an emergency and stand-alone initiative but one that connects to a range of policy areas, in particular the Government’s strategy on tackling loneliness (DCMS 2018) which recognises the power of digital inclusion in bringing groups of people together for social connections; and the recent Online Media Literacy Strategy (2021), which recognises the importance of helping people to understand about online safety, and build the skills to navigate the online environment in a safe way. (This is linked to the Draft Online Safety Bill currently progressing through Parliament.)

A new Digital Strategy is being developed led by DCMS. This may provide a valuable opportunity to strengthen commitments to digital inclusion, including for disabled people and people with learning disabilities, and to recognise the critical role that digital inclusion can play in contributing to post-COVID-19 recovery and the government’s levelling up agenda (Good Things Foundation 2021b).

With regard to disabled people, the Department for Work and Pensions, the Disability Unit and the Equality Hub published the National Disability Strategy in July 2021. This sets out the actions the government will take to improve the everyday lives of all disabled people across the UK. It outlines the aim for all government departments to embed approaches which: ensure fairness and equality; consider disability from the start; support independent living; increase participation; and deliver joined up responses.

2.6.2 What practical responses have there been?

COVID-19 exposed the cost of digital exclusion more clearly than ever before, and necessitated action from across communities, corporates and civil society. The practical emergency response by actors across society has been impressive. However, many of these responses took place in isolation — and there remains a lack of a joined up approach.

Some of the practical responses taken include: the donation and distribution of new devices (e.g. Everyone Connected, Connecting Scotland, and Digital Communities Wales); the donation and distribution of refurbished devices (e.g. Reboot); the zero-rating of some educational, health and voluntary sector emergency websites (such as Citizens Advice); and actions taken by telecoms providers such as the introduction or improvement of voluntary social tariffs, removing data caps and donating sims / vouchers.

There have been very few nationally coordinated initiatives to address digital exclusion among people with learning disabilities. One such initiative is led by Mencap with support from Digital Unite and Good Things Foundation to provide devices and digital skills support to people with learning disabilities through Mencap’s local and regional members. There have also been initiatives at county, city and community levels — for example 100% Digital Leeds is working with third sector partners across Leeds to improve digital inclusion and participation for people with learning disabilities and autism. However, provision is patchy and — in the context of the pandemic — Digital Lifeline bridged a major gap in national support for digitally excluded people with learning disabilities in England.

3. Delivering Digital Lifeline

3.1 Programme support provided by Good Things Foundation

Good Things Foundation is the UK’s leading digital inclusion charity. In delivering Digital Lifeline, Good Things Foundation led on procuring devices and data; partnership and project management; data collection and analysis; the recruitment of community and coordination partners to distribute the devices and provide support; and providing training and support to these community and coordination partners. In a survey (n=50) conducted with community partners in June 2021, most agreed that: the programme was well advertised and easy to apply to; that communication from Good Things Foundation was clear; and that the support provided by Good Things Foundation was helpful.

(The community partner survey captured the impacts of Digital Lifeline on beneficiaries and community partners, as well as feedback regarding the challenges presented by the programme. Community partners who had returned impact data by 10th June 2021 were invited to respond to the survey. Of the 126 community partners who were invited, 50 responded.)

3.2 The role of community and coordination partners

In delivering Digital Lifeline, Good Things Foundation worked with 146 community and coordination partners, to identify beneficiaries eligible for devices; to distribute these devices to beneficiaries; and to provide digital skills support to beneficiaries. Some of the community and coordination partners funded through the Digital Lifeline had already been part of Good Things Foundation’s Online Centres Network, while for others, it was the first time they had worked with Good Things Foundation.

Evolving the ‘Everyone Connected’ model, the Digital Lifeline Fund introduced the use of ‘coordination partners’ to increase the geographical reach of the programme, and to ensure that the programme could be delivered in the timeframe. Coordination partners assisted delivery and received an additional grant payment to cover coordination costs (including engagement with beneficiaries, as well as the receipt, delivery and setup of the devices on a larger scale). Over one-fifth of beneficiaries were supported by a coordination partner.

In a survey conducted with community partners in June 2021, all bar one said they had already supported people with learning disabilities prior to delivering Digital Lifeline; and a further 73% said they were experienced in supporting people with long term health conditions or disabilities in addition to a learning disability.

Nearly half (46%) of community partners said they provided care or support services (either in-house, in a specialised care facility, or through carers or support workers making home visits); 18% of community partners said they were specialist education providers; 6% offered community-based support; and 3% said they provided self advocacy or user led support.

The majority of community partners involved in Digital Lifeline (56%) said they were operating at a local level, enabling them to have strong ties to their communities. Over a quarter of partners (27%) said they had a national operation; and 7% said they are regional.

3.3 Digital Lifeline beneficiaries

Community partners identified beneficiaries who could benefit from a device through a range of methods including through their direct service delivery and through partnerships with other organisations.

We went through our database of clients that we were working with, targeted the ones that we felt were most isolated within that group, and then approached them, or their carers, to see whether or not a device like a tablet would help them to engage, or do shopping online, or whatever.

- Community Partner

Reflecting the aims of the programme, baseline data (n=5,356) found that most beneficiaries receiving devices reported having a learning disability (see Figure 1). A significant number reported additional impairments — for example, 32% said a condition or illness affected them socially or behaviourally; 27% said a condition or illness affected their mental health; and 24% said a condition or illness affected their mobility.

(Note: The baseline survey was completed by beneficiaries (with support from community and coordination partners) on receipt of their device. The survey covered beneficiary demographics, goals and barriers.)

Fifty three percent said they had a condition or illness that impacted a little on their ability to carry out daily activities; 38% said they had a condition or illness that impacted them a lot.

Figure 1: Self reported conditions (People could select more than one condition)

| Self reported conditions | Number of Digital Lifeline beneficiaries |

|---|---|

| Learning or understanding, or concentrating | 4,013 |

| Socially or behaviourally (for example autism, ADHD) | 1,706 |

| Mental health | 1,434 |

| Mobility (for example walking short distances or climbing stairs) | 1,280 |

| Memory | 1,073 |

| Dexterity (for example lifting and carrying objects, using a keyboard) | 786 |

| Vision (for example blindness or partial sight) | 565 |

| Stamina or breathing, or fatigue | 431 |

| Hearing (for example deafness or partial hearing) | 362 |

| Other (please specify) | 307 |

Digital Lifeline benefited people from a range of backgrounds and demographics:

-

People of all ages received devices: 41% of recipients were adults under 34 years old; 25% were aged 55 years or above. (Figure 2)

-

More men received devices than women: 57% men compared to 43% women. Four people chose “I’d prefer to describe myself” when asked for their gender (less than 0.1% of all beneficiaries). This category could include people who do not identify as either male or female.

-

Most recipients (83%) were from a white ethnic group. A significant minority were from black and minority ethnic groups. (Figure 3)

-

The majority of recipients reported living with adults other than a spouse or partner, in supported living accommodation or residential care. Very few lived with children. (Figure 4

Unfortunately, due to a lack of data on the demographics of the population of people with learning disabilities, it is not possible to determine whether Digital Lifeline beneficiaries were representative of the population of people with learning disabilities as a whole.

Figure 2: Breakdown of Digital Lifeline beneficiaries by age

| Age group | Share of Digital Lifeline beneficiaries |

|---|---|

| 16-24 years old | 20% |

| 25-34 years old | 21% |

| 35-44 years old | 17% |

| 45-54 years old | 18% |

| 55-64 years old | 16% |

| 65-74 years old | 7% |

| 75+ years old | 2% |

Figure 3: Breakdown of Digital Lifeline beneficiaries by ethnic group

| Ethnicity | Share of Digital Lifeline beneficiaries |

|---|---|

| White | 83% |

| Asian / Asian British | 8% |

| Black / African / Caribbean / Black British | 5% |

| Mixed | 2% |

| Other | 1% |

Figure 4: Breakdown of beneficiaries by household composition

| Household composition | Number of Digital Lifeline beneficiaries |

|---|---|

| I live with one or more other adults that are not my spouse / partner (aged 18 or over) | 2,289 |

| I live in supported living or residential care | 1,802 |

| I live on my own | 1,025 |

| I live with my spouse / partner (couple) | 213 |

| I live with one or more children (aged 17 and under) | 191 |

| None of the above | 81 |

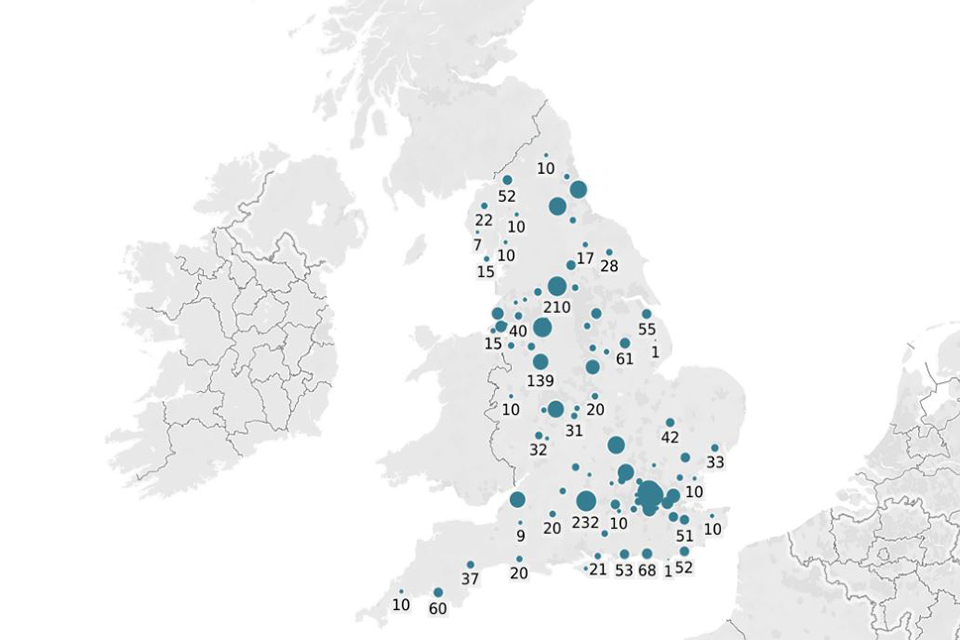

Beneficiaries were well represented in most areas of England. Figure 5 shows the number of baseline survey completions per Local Authority. [Note: 211 recipients did not have geographic data available from their community partners; some of the partners are national organisations so could have headquarters in London but distribute outside London, so this data is indicative but not fully representative of recipient locations.]

Figure 5: Geographic distribution of programme support

3.4 The device distribution process

Devices were predominantly delivered to beneficiaries’ homes by staff members or volunteers due to COVID-19 restrictions. Delivering devices by hand was beneficial as staff and volunteers were able to run through device setup and basics with the beneficiary upon receipt of the device. However, this was logistically challenging due to the time constraints of the project and, for those operating across a wider area, the geographic spread of beneficiaries.

Coordination partners were used where devices were being distributed across a wider geography — with logistics firms also sometimes playing a role if an organisation was operating across multiple locations. The use of coordination partners could add extra layers of complexity as it was important to have detailed record keeping processes in order to: stay on top of deadlines and follow-up with the recipients.

I’d say about fifty percent of [the devices] were hand-delivered. The other fifty percent was sent by recorded delivery because of people shielding, their location, or not being able to get out to them because a lot of our services were actually off-limits because of lockdown.

- Community Partner

We actually worked with partnership agencies. So we worked with an organisation that […] runs a couple of supported living places, and they had quite a few candidates who they fed through to us.

- Community Partner

3.5 The device set-up process

The processes that community partners used to set up devices for beneficiaries varied. Larger organisations, and those with larger reach, tended to find it more efficient to pre-load devices with a standard set of apps and resources (such as links to Learn My Way or their organisation website). (Learn My Way is an online platform run by Good Things Foundation offering free online courses to help people learn digital skills to stay safe and connected.) In contrast, smaller community partner organisations, with a more local focus, often had conversations with individual beneficiaries before giving them the device (which enabled them to add a selection of apps tailored to beneficiaries’ interests). It is worth noting that not all smaller, local organisations had the capacity to take this personalised approach.

We ensured that we had the tablets set up with each person’s own Google account. We connected the Mi-Fi straight away. All the apps were on there. The NHS app was on there. The video app was on there. The guide on how to use the tablet was on there. So what it meant for any user is once they connected the tablet up to the Mi-Fi device, they were able to access information straight away.

- Community Partner

3.6 Digital skill support provided by community partners

As part of their involvement with Digital Lifeline, community partners were funded £100 to provide basic digital skills support to beneficiaries. Community partners reported that the majority of the initial support provided to beneficiaries took place on a one-to-one basis — either remotely or face-to-face. Although the roll out of Digital Lifeline took place when COVID-19 restrictions were beginning to ease, many beneficiaries were still shielding, and many others still felt uncomfortable returning to group learning environments. Community partners were keen to provide support in an environment where the beneficiary felt safe, and one-to-one support was often the best way to meet this need.

The initial stages of support provided by community partners often focussed on the basics, such as turning on the device, connecting it to the MIFI unit and adjusting settings (e.g. changing the volume). Community partners commented that teaching beneficiaries these skills was often much easier to communicate one-to-one. One-to-one support in the initial stages was also beneficial in growing beneficiaries’ confidence because it allowed them to ask questions in a non-judgemental environment and learn at their own pace. Several community partners we spoke to also noted that providing support one-to-one, helped them to understand the support needs of their beneficiaries better.

A lot of the clients did need that one-on-one support throughout, one-to-one training and group sessions online.

- Community Partner

After the tablet was delivered to beneficiaries, and they had been shown the basics, many community partners provided a series of training sessions to further expand beneficiaries’ skills. In many instances these training sessions were fairly informal, however a small number of community partners put together a more structured ‘curriculum’ of topics. Most community partners also provided support in relation to staying safe online — either through formalised training, sharing resources, or offering informal guidance.

We gave out an easy-read staying safe online guide with every device, and then I said, “If you want further training, there’s training resources available so you can book in with [name] or you can phone me and we can give you further training resources on that.

- Community Partner

Following the initial period of support, community partners tried to follow up with beneficiaries on a regular basis. Despite not being funded to do so, many community partners are continuing to support beneficiaries to use their device several months later — either through one-to-one support, group sessions or via providing ‘troubleshooting advice’. A small number of community partners are also offering accredited IT courses.

Because of the groups that we work with, we engage with them on a weekly basis anyway, it’s easy for them to keep coming back to us. And that’s the main thing, is providing that support once the project’s finished.

- Community Partner

Community partners used a range of resources to support training sessions — but Learn My Way was the most mentioned among those we spoke to. That said, many community partners commented that Learn My Way, alone, was not sufficient to provide all teaching material — and that accessibility challenges made it challenging for beneficiaries to use Learn My Way for self-led learning.

During the delivery of the programme, 2,023 Digital Lifeline beneficiaries (37% of beneficiaries) logged onto the basic digital skills platform Learn My Way (provided by Good Things Foundation). Of those that logged in 371 (18%) started courses and 214 (11%) completed courses (based on analysis of Learn My Way usage). A substantial number of those not using Learn my Way said they were waiting for COVID-19 restrictions to ease fully before holding in person sessions using Learn My Way.

So we directed people to Learn My Way, because we started drafting up resources and then we saw all the resources on Learn My Way, which were short bite-sized pieces, easy to use. So we directed people along with staff teams as well, because it was free to sign up to Learn My Way.

- Community partner

3.7 The role of beneficiaries’ wider support network

Families and carers could play a vital role in whether or not a beneficiary was able to take part in the programme, and the extent to which they were able to benefit from having the device and data.

Most families and carers were excited and engaged with the programme from the start — and in a small number of cases families and carers played a connector role, referring other beneficiaries into the programme. However, community partners mentioned that there were also a sizable minority of families and carers who did not immediately recognise the value that the device could bring to the person they supported.

Families have referred other beneficiaries. They are important in providing care for people and have been very excited about this opportunity.

- Community partner

Families, carers and support workers could also play a very important role in providing informal support alongside the support provided by community partners — particularly if a beneficiary had higher support needs. Beneficiaries with higher support needs tended to make more progress in their digital confidence, motivation and skills if they had families, carers and support workers who were able and willing to spend the time supporting them to use their device.

We have such a broad range of customers. Non-verbal, blind, deaf. For someone like that, the carer does a lot. Carers do the physical facilitation of the device with a lot of customers. For more vulnerable customers, carers are highly involved.

- Community partner

I think it is very useful that people that are suffering from these mental disabilities have carers and family members that can also assist in building their skills […] we noticed that working with this particular group, there’s heightened anxiety and a need to constantly ask questions, not just at the times of designated support.

- Community partner

3.8 Accessibility-related support provided by AbilityNet

AbilityNet are experts in supporting people with disabilities to use technology. As part of the Digital Lifeline, AbilityNet ensured beneficiaries and community partners had access to: specialist advice and assessments about how to adapt devices to meet beneficiary needs; additional assistive equipment; training and information on accessibility and disability related considerations of the project through resources such as their Helpline service.

AbilityNet supported 971 beneficiaries (18% of the total 5,500 beneficiaries) with an initial and follow up assessment(s) and, where required, additional assistive or adaptive technology to support them to use their device. 371 people (38%) of those supported received a full needs assessment and further advice, and 2,354 items of equipment were provided to beneficiaries (AbilityNet 2021).

AbilityNet (2021) noted that the biggest barriers faced by those they supported were inputting text, understanding text and operating the tablet. The most used adjustments to devices were Action Blocks, Voice Assistants and magnification. AbilityNet also provided assistive hardware including external keyboards, styluses and cases.

The assessments were invaluable; I think that this should be used for all applicants as standard. Helped people identify things they needed - apps and extra equipment.

- Community partner

AbilityNet also provided training sessions to 121 community partners to help them better assist the people with learning disabilities they were supporting, and 101 community partners were also matched with a volunteer buddy to provide ongoing support beyond the project date (AbilityNet 2021).

It has been said that they [AbilityNet] are at the end of the phone if we need anything further, which is very reassuring, especially as we are supporting 60+ individuals with devices just in our service area alone.

- Community partner

3.9 Digital champion online training support provided by Digital Unite

Digital Unite are specialists in digital champion training, and as part of Digital Lifeline they have supported community partners of Digital Lifeline to embed digital inclusion into their services. Through the Aspire platform, they have provided online training and content for digital champions to develop their own skills, and teach those skills to others.

(Note: Data in this section is based on Aspire learning report, shared by Digital Unite: usage data up to end of October 2021).

By the end of October 2021, 69 community and coordination partners had accessed Digital Unite’s platform, and 288 Digital Unite ‘Champion’ online courses had been completed. The top resources accessed by Self-Advocates have been: the one-to-one session plan template; ‘Become a Zoom expert’ lesson plans; ‘Getting started with a laptop or desktop computer’ and a video on tips for communicating with people with learning disabilities. The following were also among the top resources viewed by Digital Champions overall: simple activities to get someone with a learning disability started with digital skills; the one-to-one session plan template; getting started with a laptop or desktop computer; the learner planning and review sheet; and getting started with social media.

Only a small number of community partners that we spoke to as part of the qualitative evaluation had accessed support through Digital Unite. Many of the community partners we spoke to commented that the type of support that Digital Lifeline felt less relevant for the stage — as not all beneficiaries were at the point where they were able to teach others. Digital Unite also reported that even when the lead contact for a community partner was willing to engage with Aspire, they often needed time, and support, to engage others within their organisation to take the offer up.

Among those who have accessed Aspire, there has been a high level of engagement with the learning content. Digital Lifeline learners spend longer exploring resources than the average Aspire user, and also report higher levels of satisfaction with the learning content. Ninety six percent of Digital Lifeline Aspire users recommend the training on the platform, and compared to the average learner, Digital Lifeline learners were more likely to say that: Aspire courses were relevant to their learning needs; Aspire courses had increased their knowledge; Aspire courses had increased their confidence; and that doing Aspire courses will help them to help others.

I’ve really enjoyed doing the Aspire courses. As I’m relatively new to the industry, I found that the platform was a great way to find the information that I needed, without feeling like it was a silly question!

- Community partner

Digital Unite was useful. Went on, looked at their courses and stuff and we ran through the Zoom session on there, and in fact I attended one of their seminars where they covered more about what they provide in terms of the service.

- Community partner

Many of the community partners we spoke to were open to exploring Aspire in the future, and suggested Digital Unite’s resources could be useful once beneficiaries had had the time to build their digital skills a bit more. Digital Unite will continue to provide access to the Aspire platform for community partners that were involved in delivering Digital Lifeline (and those that were unsuccessful in their funding application), until December 2021.

4. The beneficiary experience of Digital Lifeline

4.1 What barriers were beneficiaries facing to getting online?

The most commonly reported barriers to using the internet among beneficiaries were: having a disability or health condition (52%) and not being able to afford a device (43%) (Figure 6). These reflect the aims and selection criteria for the programme - and were successfully addressed through the Digital Lifeline (Good Things Foundation, 2021).

Figure 6: Beneficiary responses to the question: What prevents you from using the internet/using it more at home?

| Internet barriers | Number of Digital Lifeline beneficiaries |

|---|---|

| Difficult because of my disability or health condition | 2,776 |

| Not enough money / cannot afford it | 2,286 |

| Worried about the risks | 663 |

| Other (Please specify) | 409 |

| Not for people like me | 396 |

| Difficult because my area doesn’t have good broadband or mobile coverage | 387 |

| Difficult because English isn’t my first language | 204 |

4.2 What did beneficiaries want to use their device for?

When completing the baseline survey, beneficiaries were asked to select up to three goals for what they wanted to use their device to do. The most mentioned intended uses for the received devices were to: connect with friends and family; for interests and hobbies; and to connect with support groups or services (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Beneficiary responses to the question: What do you MOST want to be able to do when you get your device? (You can select up to three).

| Desired outcome from using device | Number of Digital Lifeline beneficiaries |

|---|---|

| To connect with friends and family | 3,628 |

| For interests and hobbies | 3,078 |

| To connect with support groups | 1,866 |

| For learning or training | 1,441 |

| For information, help or advice | 1,154 |

| For my health and wellbeing | 989 |

| To make life easier (e.g. online shopping) | 839 |

| To learn how to keep safe online | 522 |

| For work or business | 165 |

| For money or benefits | 127 |

| To help or care for my family | 52 |

4.3 How are beneficiaries using their devices?

As part of the qualitative evaluation, we followed up with 57 beneficiaries to understand the longer term impact of Digital Lifeline. The qualitative evaluation was conducted from July to October 2021 (which means that beneficiaries had had their device for several months).

Most beneficiaries we spoke to were still using their tablet regularly; and over half were using it at least once a day. The key activities that beneficiaries said they were using their tablet for aligned with their stated goals on receiving the device: the most common uses for devices were for connectivity and entertainment.

Many beneficiaries were using their tablets to connect with their families and friends, through video calls, or social media — and, among those who were not yet able to use their tablets for video-conferencing, many mentioned that this was the next thing they would like to learn.

I was pleased to get the tablet to communicate with people on the tablet and get to know people. It gives me some independence.

- Beneficiary

I know two young ladies have become very firm friends through that, and they talk about relationships and difficulties, and some quite serious stuff, but also light and fun stuff as well, so it’s a genuine friendship that two people have formed, never having met before.

- Community partner

Many beneficiaries were also using the tablets to explore their hobbies and interests. In some instances this entailed engaging with these hobbies and interests online; in others it could be searching for opportunities to engage with these hobbies and interests offline. A lot of the participants also mentioned the use of their device to stay active either via activities on Zoom such as Zumba classes or researching activities in the community and accessing those.

It’s helped us be active because we’ve looked up events around the city and then we go to them.

- Beneficiary

I use it for drawing pictures and music, I have sensory apps that are downloaded. It means that I can now listen to music and I can do my sensory stuff.

- Beneficiary

Many beneficiaries also reported using their tablets for the purpose of learning. In some instances this could entail learning new digital skills, in other cases this could link to their engagement with hobbies or interests.

I’ve been able to learn new skills and find things on my own.

- Beneficiary

I’m particularly proud of learning how to search for music bands. Everyone should have their own device because it makes them feel confident.

- Beneficiary

A small number of beneficiaries used their tablet to access online health services, online financial services, online shopping, or for work or volunteering. However, these were not common activities among those we spoke to. As we will explore later, the gaps in current usage may not be due to a lack of motivation — but rather a reflection of factors such as the level of ongoing support a beneficiary has access to, what types of activities they are encouraged to explore, and whether or not they can continue to access the internet after their data allowance has run out.

Zoom was new to a lot of people, and as we’re coming up with the health appointments, they’re being supported to use the device to talk to their GP locally.

- Community partner

He learnt how to repair bikes through using YouTube. And now he does a little bit of a repair on his friend’s bikes for a little bit of pocket money.

- Community partner

Case Study: Muhammad

Muhammad’s tablet allowed him to be more active, learn new things, become more comfortable with technology, grow in confidence and interact with others. He used his tablet so much he ran out of data.

When describing how he uses his tablet, Muhammad said, ‘it actually introduced me to a new hobby, which was drawing.’

He also explained that he had used the tablet to join a drama group.

‘In the drama group online, we were learning how to use a basic form of sign language to sing a song called Lean on Me.’

Muhammad also joined a shared reading group, describing it as ‘sharing things from your life. It was intriguing and interesting for people to be able to relate to each other and have a chat.’

In addition to this, Muhammad also used his tablet to represent his organisation at a community organising conference, where he ‘talked about setting up groups to facilitate for people who have been stuck and have not been able to get out of their houses.’

He said that ‘it felt good to be representing [my organisation]’.

(Names have been changed)

Case Study: Fatima

Fatima uses the tablet for her job, which involves creating games.

‘I use the tablet mainly for programs for creating games.’

She uses various programs, such as Sketchbook, Zoom and Photopea to create these games.

Even though Fatima has moderate communication difficulties, she is still able to use her tablet to pursue her passions through paid employment. Her story shows how important it is for people with learning disabilities to be trained and given opportunities for paid employment.

(Names have been changed)

4.4 Beneficiary feedback

All of the beneficiaries who gave feedback as part of the qualitative evaluation were happy to receive their device, and all except one had said that it made a difference to their life.

It would be useful for everyone to have a computer.

- Beneficiary

It was like a Christmas present for many of the people. And one of the questions we were asked, like, “Can we keep it?” It was just, “Of course. It’s yours.” I think it’s made a huge impact on the people.

- Community partner

Most beneficiaries had the appetite to continue using their device and were keen to expand their digital skills. Some of the activities that people wanted to learn included being able to access online health services, being able to pay bills online or access online banking, being able to use the internet for online shopping, and being able to use the internet for work or volunteering.

I would like to video call my family, do presentations on it and use it more for my volunteer role.

- Beneficiary

I’d like to do online shopping and see if I could purchase a ticket for a football match.

- Beneficiary

I want to settle my GP appointments and all of my appointments on my tablet but I just don’t know how.

- Beneficiary

Although lockdown restrictions were loosening at the time of our research (July - October 2021), many beneficiaries and community partners commented that there was still a large need for the tablets because things wouldn’t be going back to normal. A lot of beneficiaries were still cautious about the impacts of COVID-19 and were wary about leaving home. Both beneficiaries and community partners were also aware that many services would remain online even after the pandemic, and therefore that having a device and a connection remained very important.

4.5 What does meaningful support look like for beneficiaries?

Our research with community partners, beneficiaries and families and carers highlighted a number of learnings in relation to what constitutes meaningful digital inclusion support for people with learning disabilities. The successes of the support provided through Digital Lifeline were:

4.5.1 A new device that was given, not loaned

Beneficiaries really valued having a device that was theirs and that they owned. This was partly because it made them feel valued and recognised as an individual. However, it was also because owning the device allowed them to practice and experiment without having to worry about breaking it or having to give it back. A new device could also help to alleviate fears around safety — for example, one community partner mentioned that beneficiaries became worried if they had opened the device packaging before giving it to them.

Everyone should have their own tablet to keep in touch with their family.

- Beneficiary

Oh, I think they’ve definitely felt – because, you know, to get that and to feel like it’s yours and you own it, I think that’s definitely given them confidence to use it more often.

- Community partner

4.5.2 Support delivered by someone the beneficiary trusts

Receiving support from someone that beneficiaries know and trust was often vital to their engagement with the programme. Community partners played a crucial role in encouraging beneficiaries to use their tablet, and provided a safe environment for beneficiaries to grow their digital confidence.

Being supported by someone they know and trust has also made it easier for beneficiaries to reach out to ask for advice or guidance when they get stuck. This was important because it helped beneficiaries to overcome barriers in their learning journey. Community partners noted that after receiving devices and becoming familiar with using them, many beneficiaries were initiating communication themselves, rather than waiting for staff members to check in.

4.5.3 Support tailored to the stage in the learning journey

Community partners commented that one-to-one support was often crucial in the initial stages of digital learning, as it allowed beneficiaries to ask questions in a non-judgemental environment and to learn at their own pace. As beneficiaries became more confident, group training and support could also be effective to grow beneficiaries’ digital skills and facilitate peer learning — but community partners noted that this was more effective later in a beneficiary’s learning journey.

That’s been really useful, I think, because a lot of the people with autism or ADHD aren’t able to do group activities or engage in group activities easily. So … we’ve learnt a bit about that so we’ll actually do more one-to-ones with the people who need the individualised support.

- Community partner

4.5.4 Personalised support that takes into account the needs of the individual

Community partners noted that it was important to personalise support to the needs of the beneficiary, and that factors such as a beneficiary’s support needs, accessibility needs, age, levels of literacy and understanding of English could influence how they provide support. For example, several of the community partners noted that older beneficiaries tended to need greater support to understand the value of using the internet than younger beneficiaries — which, in turn, meant that community partners needed to provide more upfront support to break down motivational barriers among older beneficiaries. Other community partners noted that beneficiaries with severe or profound and multiple learning disabilities could require a higher level of, more regular, one-to-one support, than those with mild or moderate learning disabilities.

We did change our sessions, depending on, as I said, people with moderate learning disabilities, to those who are more severe. We had to change them and we had to, in a way, slow them down and we had to give more additional hours.

- Community partner

4.5.5 Using specialist support and assistive technology to aid learning

Community partners were pleasantly surprised by the extent to which assistive equipment helped beneficiaries to engage with their tablet. Community partners commented that assistive equipment and software was beneficial for all those using it — but were particularly surprised by the impact it had for people with higher support needs.

Some of the accessibility tools as well, like having the screen reader and things like that, for people who can’t read. That’s been great. I know that one lady has been working with a volunteer, and she’s managed to put an app for audiobooks on there.

- Community partner

AbilityNet has been great. They’ve given loads of training on the accessibility tools, they’ve been really helpful. We’ve been paired with a local volunteer coordinator there. He’s answered some technical questions for me.

- Community partner

Case Study: Lucy

The first thing Lucy did with her tablet was install a braille keyboard on it. She said: “We looked on the internet at downloading apps that were accessible for the blind, we got it from AbilityNet, and we were able to put a braille keyboard on it so that I can type in braille. […] it is amazing.”

She is now using her tablet for social media, Google and checking the weather.

She expressed the difference that having a tablet with a braille keyboard made in her life, saying: “It’s been brilliant. It’s opened up a lot of opportunities to be able to look up certain things on the internet and look up things in more depth.”

She also expressed interest and enthusiasm in learning how to do new tasks, including shopping online, FaceTime, sending emails, and listening to music.

(Names have been changed).

4.5.6 Using hooks to encourage engagement

Many community partners commented that linking digital skills training to the hobbies or interests of beneficiaries could help to overcome motivational barriers, and facilitate a fun way for beneficiaries to learn. For example, several community partners noted that using games and puzzles that were already familiar to beneficiaries (e.g solitaire or chess) were good ways to interest people in using a device, and build up skills such as using a touch screen in a fun and engaging way.

So we’ve got people that have been downloading apps for entertainment, whether that’s games or puzzles, or anything like that. People have been using YouTube for movies and entertainment. We’ve got people who are blind and non-verbal but they like to listen to music, so it’s quite useful for them to have apps for music.

- Community partner

4.5.7 Ongoing support to repeat and build learning

Community partners noted that people with learning disabilities must be allowed to learn at their own pace, and that acquiring digital skills cannot be rushed. Building confidence by regularly using the device for simple tasks such as playing games is essential before beneficiaries can progress to more complex tasks like online shopping and online banking. Using a device has to become habitual to ensure beneficiaries have the confidence to explore the internet in different ways. Staff members, volunteers, carers and family members often have to actively encourage device use before it becomes ingrained in a beneficiary’s routine.

So that’s something that we’ve instilled in the staff, is that we want regular and consistent use of [the device]. Persistency has definitely paid off. Because for a lot of our customers, you lose interest […] it will be forgotten about and it won’t be used.

- Community partner

So I’d say the motivation is there a lot of the time, but for a number of the beneficiaries, they still need prompting to remind them, and then they would be motivated. Like if you didn’t say to them in the morning, “Oh, do you want to use your tablet today?” they might not think about it.

- Community Partner

4.5.8 Encouraging people to take ownership of their learning

In order to ensure that beneficiaries realise long term digital skills gains, it is important that they are provided with the training to be able to use their tablet with as little support as possible. Community partners noted that it could sometimes be challenging to encourage people to take ownership of their learning, as they were used to having things done for them. However, community partners noted it was important to teach people how to do a task, and not do it for them. Beneficiaries needed to be shown how to do a new task and be given the opportunities to practice in different environments in order to embed their learning.

People forget. Our guys need repetition and practice, and when they’re not doing that all the time independently, because they’re quite used to sometimes being dependent. I think sometimes some customers can get used to depending on other people to do things for them. So I guess it’s remembering how to do very small things, sometimes, and that can be a barrier to progression as well.

- Community partner

4.5.9 Support to help beneficiaries and their support networks to stay safe online

Online safety could be a concern for beneficiaries, and their families, carers and support workers and many community partners developed online safety resources to allay these fears — either sending these resources out with the tablets, or uploading the resources onto the devices themselves. A sizable minority of community partners also provided online safety training to staff, volunteers, beneficiaries, families and carers. Many of these community partners noted that it was important to provide this training to beneficiaries’ wider network as well, as fears about online safety were not always coming from beneficiaries themselves.

Anxiety [about online safety] is generally higher amongst people with learning disabilities than the wider population […] and sometimes family members kind of feed those fears. “Make sure you’re very careful, make sure … Don’t do this. Don’t do that. Don’t share your thing with that.” And it just builds up this sense of something to be afraid of.

- Community partner

I’m not shopping online, I don’t trust the internet. I’m a bit worried about getting hacked.

- Beneficiary

Case Study: Kobe and Charles

Kobe and Charles are brothers. While they enjoy using their tablets and are quick learners, they both seem a bit afraid of technology.

The brothers rely heavily on their support worker and do not want to use their tablets independently because they are afraid of making a mistake with it. They do not want to bring their tablets home with them, so their tablets stay at the day centre.

When asked if there was anything they would like to do by themselves, the brothers replied: ‘We leave it where it is. No, it’s quite complicated. We don’t want to change it.’

(Names have been changed)

4.5.10 Including families, carers and support workers in digital skills training

Beneficiaries often reaped greater rewards if they were able to practice their digital skills on a regular basis at home. As a result, the role of families, carers and support workers could often be very important in the extent to which a beneficiary was able to progress with their device — particularly for beneficiaries with higher support needs.

I’d say, for certain people, I would arrange, when there was a family member or carer there, if that’s what they needed. And that was the key to getting them on really, because some people just needed somebody there to help them.

- Community partner

The extent to which a family or carer was willing or able to provide support was influenced by their engagement with the process; the time they had available; and their level of digital confidence, motivations and skills. While community partners could not influence the amount of time that families, carers and support workers had to provide support, they explained that including them in the digital skills support provided to beneficiaries could help to engage families and carers with the project, and grow their confidence in using the tablet.

4.6 What were the barriers to providing meaningful support?

As well as highlighting what worked well in the support provided by community partners, our research also highlighted a number of barriers that could stop community partners from being able to provide high quality support to beneficiaries. These barriers related to connectivity; confidence and skills gaps among those that support beneficiaries; and the timelines of Digital Lifeline delivery.

4.6.1 Connectivity barriers: Lack of a sustainable data solution

As it has now been several months since beneficiaries received their device, some beneficiaries have now used up their data allowance. Beneficiaries who do not have access to WIFI in their homes, are using their devices for activities that require a lot of data, or are sharing the device with other people in their household are more likely to have used up their data allowance.

A significant portion of the community partners we spoke to mentioned that they had provided guidance to beneficiaries about the types of activities that required large amounts of data. However, this could restrict beneficiaries from exploring the full remit of activities available to them online — not to mention the fact that the activities that people were most likely to want to do were often data intensive (e.g. communicating with family and friends).

A small number of community partners have tried to set beneficiaries up with affordable data packages but these are not accessible to everyone, and community partners mentioned that one-time data top ups are not sustainable in the long term. A small number have also applied for grants to buy beneficiaries extra data, either through Good Things Foundation or other organisations. Where possible, community partners have also been directing beneficiaries to use public WIFI — though this has safety implications if beneficiaries are using unsecured public WIFI to make payments or input any sensitive information which could be hacked.

Two particular customers then went in to buy their own data and if I recall, that wasn’t very cheap, actually, for what we wanted to use because it became like a learning aid for her children as well. So they used to do online classes on it, as well as watch YouTube videos.

- Community partner

The data was sufficient - as it says it’s for about two years - but it does depend on how you utilise it. My sister is quite good at limiting the amount of data she uses, she’s got to know that because I said you’ve got to use it then turn it off then you will save the data.

- Family / carer

4.6.2 Connectivity barriers: Communicating data limits to beneficiaries

Community partners noted that communicating what ‘data’ is and how it can be used was one of the most challenging topics to explain to beneficiaries. For example, several community partners mentioned that beneficiaries could become confused about the difference between the data amount (24GB), and the length of time the data was valid for (two years). Several of the community partners we spoke to had created information sheets about how data works, activities that use up data quickly, and what to do when data runs out — though these community partners mentioned that some beneficiaries still remained confused about what the data limit meant.

I think the challenge is just sort of understanding about the data, understanding what that actually means – you know, about gigabytes and megabytes and all of that, and actually half an hour video messaging call will probably suck up this much.

- Community partner

4.6.3 Confidence and skills barriers: Safety concerns from family, carers and community partners, limiting beneficiary learning

A lack of confidence, or concerns about safety, could lead community partner staff and volunteers to restrict the learning of people with learning disabilities.

Community partners were provided with guidance on the approach that they should take to safeguarding and online safety during Digital Lifeline (a copy is available from Good Things Foundation). This guidance outlined that the Digital Lifeline project team and community partners were expected to acknowledge that device beneficiaries are adults, and that community partners were expected to support people to make informed decisions about what they access online.

In general, community partners followed this guidance. However, there were a few instances where there was evidence of staff and volunteers restricting beneficiaries’ opportunities to receive and use their devices. For example, rather than providing online safety training to beneficiaries, one community partner mentioned that they were using the ability to be safe online as an eligibility criteria for the programme — during the risk assessment stage, they had considered a person’s perceived tendency towards unsafe online behaviours (such as online gambling) in whether or not to provide them with a device. Another community partner mentioned that, rather than allowing beneficiaries to take their tablets home, they had felt it was safer to keep the tablets at their centre for beneficiaries to use there. Several community partners had also made a decision not to access support from AbilityNet and Digital Unite because they thought that beneficiaries would be uncomfortable receiving support from a stranger.