Deter, disrupt and demonstrate – UK sanctions in a contested world: UK sanctions strategy

Published 22 February 2024

Foreword by the Foreign Secretary

We live in a more dangerous and uncertain world. A world marked by hostile states, terrorist organisations, cyber threats, criminal gangs, and a whole range of challenges to our democratic and economic system.

For Britain and our partners, sanctions are a vital tool for pursuing our interests and protecting our values. They send a signal. But they also have a tangible impact.

By targeting particular individuals or resources, they impose costs on those we target, thereby changing their calculus. Allied with adept diplomacy, they can constrain an adversary or deter them from an unwise course of action.

In just a few years, Britain has built up its own formidable sanctions capability. We implement measures agreed by the United Nations Security Council, but we also act alone or with smaller groups of countries when there is multilateral deadlock.

We are already seeing this capability in action across the world – deterring human rights abuses, disrupting Russia’s war machine or demonstrating our opposition to corruption.

Nevertheless, in the world of today, our sanctions need to be as effective as possible. That requires building partnerships. With close allies, with whom we coordinate to maximise impact and eliminate loopholes. With the private sector and civil society, so that the costs fall on those whose behaviour we wish to influence, rather than the innocent and vulnerable. And across the Government, harnessing the efforts and expertise of all Departments.

Preparing and announcing sanctions in the UK is one thing, making sure they are followed through – including in other countries – is another. We have increased investment in sanctions implementation and enforcement. We are cracking down on efforts to bypass our sanctions, including through closer cooperation with third countries and businesses. Our adversaries seek ways around our measures. It is our job to stop them doing so.

Effective sanctions also require strong legal foundations. The ability of individuals or entities to challenge our measures before a court is a mark of our values and respect for the rule of law. With the power to impose sanctions comes the obligation to do so lawfully.

We continue to adapt and reinforce our approach. In the Integrated Review Refresh, the Prime Minister announced a new Economic Deterrence Initiative to strengthen our sanctions’ impact. And we are working with allies to pursue all possible ways, in line with international law, to unlock the value of immobilised Russian sovereign assets to support Ukraine.

The world is changing rapidly. In the years since the landmark Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018, our approach to sanctions has evolved considerably. I am therefore delighted to unveil this strategy, setting out the priorities and principles that will shape our use of sanctions in the years ahead.

Sanctions must be effective. To give us more influence in the world. And to help keep Britain safe.

Executive summary

The UK has transformed its use of sanctions in recent years. We have deployed sanctions in innovative and impactful ways, including in our response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

We take a rigorous approach, carefully targeted to deter and disrupt malign behaviour and to demonstrate our defence of international norms. Our sanctions seek to isolate, restrict or change the behaviour of the actors targeted.

The UK’s sanctions help advance foreign and security priorities around the world. This includes restricting terrorist groups’ ability to receive arms and funds, controlling the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and tackling cyber gangs’ use of ransomware.

As part of the G7, the UN Security Council and through our partnerships with allies and the private sector, the UK is at the forefront of international leadership on sanctions.

We have reinforced all aspects of our sanctions activity. We have strengthened UK capability and legislation; enhanced collaboration across government; and invested further in sanctions implementation and enforcement.

This strategy sets out significant evolutions in the UK’s use of sanctions and how we will continue to make UK sanctions more effective. We will:

- undermine Russia’s ability to fund and wage its war against Ukraine, including by cracking down on efforts to get around sanctions

- address threats and malign activity through geographic and thematic sanctions regimes

- build international coalitions and take co-ordinated action with allies and partners to maximise the impact of our sanctions while deepening engagement with business, financial institutions and other stakeholders

- reinforce sanctions implementation and enforcement, including by helping UK businesses to understand and comply with sanctions and by taking robust action on non‑compliance

Across these areas, we will act effectively and responsibly by:

- using sanctions when they complement and reinforce other tools as part of a wider approach to achieving priority foreign policy and security objectives

- using the global reach of UN sanctions where it is possible to secure international agreement, harnessing our position as a permanent Security Council member

- minimising unintended consequences from sanctions within the UK and globally – including to protect humanitarian priorities; to address implications for businesses and for the UK and global economy; and to enable specified legitimate activity

- upholding legal rigour and transparency and responding to sanctions litigation

All our sanctions activity will continue to adapt to ensure we can respond to evolving threats and challenges.

Section 1: Foundations

1. The UK is adapting to a more dangerous and uncertain world. The UK’s Integrated Review Refresh sets out the implications of a more contested and volatile global context.[footnote 1] Geopolitical tensions are at their most intense since the end of the Cold War. The increasingly fragmented international system brings heightened risk, including the further spread of authoritarianism. Conflict and instability are on the rise and both state and non-state threats are growing and evolving. As the Integrated Review Refresh makes clear, “the most significant lesson is not just that the world is a more dangerous place, but that when challenged we are ready and able to respond, working quickly and effectively with our partners”.[footnote 2]

2. In this context, sanctions are a critical instrument of the UK’s foreign, national and security policy. Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, together with partners, the UK has deployed sanctions at unprecedented scale, scope and pace against a major economy and aggressor. Our sanctions approach has also evolved in other contexts – from tackling cyber gangs targeting UK infrastructure, to responding to Iranian human rights violations.

3. The context remains dynamic. Russia has had to resort to extensive, elaborate and costly means to try and work around sanctions. Designated individuals and entities are going to great lengths to try and obscure or hide their assets. At the UN, geopolitical tensions play out over sanctions, frequently blocking or diluting collective international action. Countries are reassessing their reliance on established financial systems and on the US dollar. They are taking steps to insulate themselves from the impact of current or future sanctions, posing further challenges to free trade and economic openness.

4. When the UK left the EU, it created new independent powers for when and how to use sanctions. While we continue to collaborate closely with the EU, the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (SAMLA) gives the UK autonomous powers to impose, implement, enforce and lift sanctions. The Act also allows us to uphold our international obligations in relation to UN sanctions.

5. SAMLA provides a wide range of measures to deny malign actors the benefits of interacting with the UK economy.[footnote 3] These measures can relate to finance, trade, transport or immigration. Measures such as travel bans and asset freezes can be targeted at specific individuals and entities through the process of designation (whereby they are added to the UK Sanctions List and HM Treasury’s Consolidated List). Other sanctions measures restrict activity in particular sectors or work by blocking access to resources, including through arms embargoes.[footnote 4]

6. This gives us significant practical powers. We can, for example: stop a human rights abuser from coming to the UK or doing any business with UK firms; require financial institutions to freeze the funds in a UK bank account that a corrupt leader has stolen from his country; or, block a warmongering state’s ships from our ports and aircraft from our skies. We also have new powers to disqualify a designated person from acting as a UK company director and to take steps to stop UK technology being used to fuel conflict.

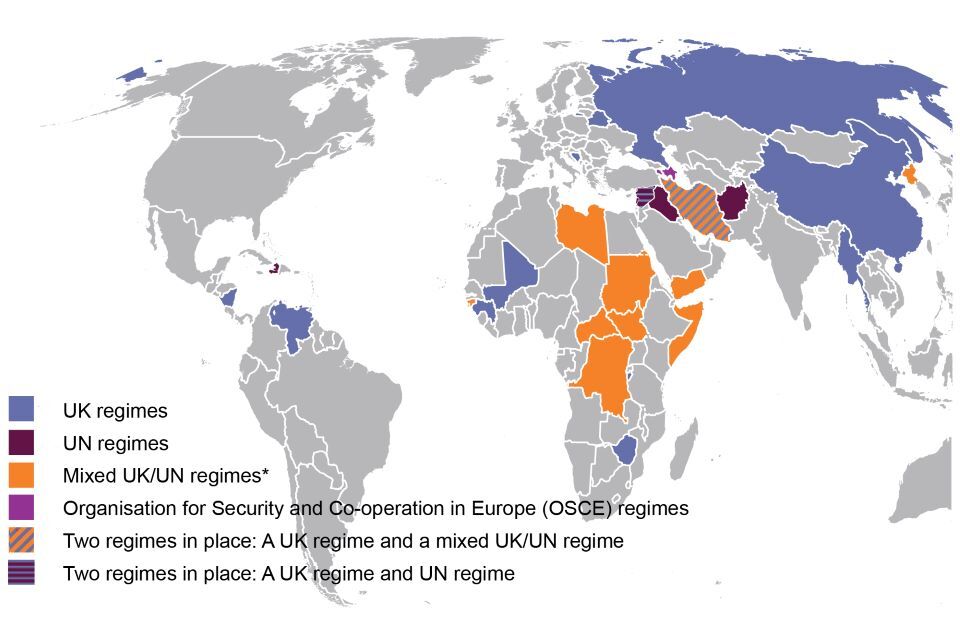

7. The UK has 36 live sanctions ‘regimes’ under SAMLA. These regimes are sets of sanctions measures focussed on specific countries or policy objectives, designed to achieve defined purposes and enshrined in legislation. The UK implements 2 further regimes through the Export Control Order 2008.[footnote 5] In addition to the UK’s autonomous regimes, we play a global leadership role on UN sanctions. The UK has 12 mixed UK/UN sanctions regimes and 7 UN-only sanctions regimes that it uses and maintains under SAMLA. A map of UK sanctions regimes can be found at Annex 1.

Core considerations

8. The UK deploys sanctions to DETER future or continued malign activity; to DISRUPT current malign activity; and to DEMONSTRATE our readiness to defend international norms. Our sanctions seek to isolate, restrict or change the behaviour of the actors targeted and to send a wider message.

9. We do not use sanctions lightly – we deploy them selectively and proportionately to complement other tools as part of a wider strategy. Sanctions will by no means be the right tool to use in all scenarios and, used in isolation, may have limited impact. Their contribution is part of wider efforts, including diplomatic, law enforcement and the implementation of other areas of UK policy. We look closely at specific contexts and the scope for sanctions to reinforce UK priorities, in line with our commitment to upholding international rules and norms. Our sanctions are consistent with international law.

10. We carefully design and target our sanctions. This includes drawing on evidence and information from a range of sources and ensuring every sanction complies with our domestic and international legal obligations, including our human rights obligations. We ensure our designations comply with the legal tests and criteria set out in our sanctions regulations, as debated and enacted by Parliament. When developing designations or designing wider measures we consider the balance between the impact on the intended target and on the UK domestically, as well as wider consequences in the target country and/or other countries. We consider whether a target has UK ties or UK-held assets such as properties or money in UK banks. We work to minimise any unintended consequences from sanctions and have provisions to enable legitimate activity and protect the delivery of humanitarian assistance. We assess sanctions effectiveness against a regime’s original objectives, changing circumstances and emerging evidence, making changes to our approach and measures as appropriate. We are investing in how we collect and assess data through our partnerships with academics and think tanks and by regularly sharing evidence and assessments with international partners.

11. We take action alongside others for maximum impact. Where we can secure timely international agreement, we initiate or support sanctions proposals at the UN given the strength of the global signal that UN sanctions send and their reach across all 193 UN Member States. Where this is not possible, we work to co-ordinate sanctions approaches and activity with our allies, such as the G7 and EU, to maximise collective impact – both in terms of the signal we send and increasing the practical reach of sanctions across multiple jurisdictions. This does not mean we will always take identical and simultaneous action – our respective sanctions regimes sometimes differ, as do the strategic objectives they serve.

12. The considerations set out in this strategy demonstrate the lengths the UK goes to ensure the strategic, proportionate and rigorous use of sanctions. This approach is consistent with overall G7-agreed principles set out in the context of Russia sanctions.[footnote 6]

Case study: Inside a sanctions designation

Once a minister approves the designation of an individual or entity and the official decision has been made, procedures follow to notify the designated party and the public. Where possible, the UK government sends a letter to the designated party informing them of the prohibitions they face. The online UK Sanctions List and HM Treasury’s Consolidated List are updated. Alerts are then sent to thousands of subscribers, including hundreds of banks that will immediately take steps to freeze any funds and other assets held by the designated party. As long as an individual or entity remains on the UK Sanctions List, and subject to an asset freeze, banks and others will prevent access to their frozen funds and assets without a relevant HM Treasury licence. The Home Office sends an equivalent alert for travel bans and determines whether the designated individual should be in scope of the ‘Authority to Carry Scheme 2023’. Under the Scheme, Border Force will refuse airline, ship and train operators the authority to carry the designated individual to the UK. If the individual is already living in the UK, the Home Office will, subject to our obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights and the 1951 Refugee Convention, cancel their leave to enter or remain in the UK in accordance with the law. In 2024, the UK will introduce a new type of prohibition across our sanctions regimes making it unlawful for a designated party under the UK’s autonomous sanctions regimes to act as a director of a UK company.

Banks and financial institutions freeze all assets held by a designated individual or entity within the UK’s jurisdiction.

Section 2: How UK sanctions support our foreign policy priorities

June 2023, Ukraine Recovery Conference in London. Photo credit: Simon Dawson/No 10 Downing Street.

Undermining Russia’s ability to wage war against Ukraine

13. Our sanctions against Russia are designed to deny Putin the means to continue his war. We are increasing pressure on Putin and his enablers; limiting access to key revenue sources and to critical goods and technology; and, isolating Russia on the world stage. Working with our closest allies, we have gone further than ever before in deploying sanctions against a major economy. We have taken major steps to cut Russia off from the global financial system; limit Russian energy-related revenues; and restrict Russia’s military‑industrial complex, including by banning all items with a potential military application. We have sanctioned over £20 billion (96%) of the goods that the UK traded with Russia in 2021. Goods imports plummeted by 94% in the year following the invasion, and goods exports fell by 74%, with a large proportion of the remaining exports being food, pharmaceuticals, and other humanitarian items. As of October 2023, over £22 billion of Russian assets were reported frozen as a result of UK financial sanctions. We have sanctioned 29 banks, accounting for over 90% of the Russian banking sector[footnote 7], and we have restricted the provision of UK and other G7 services that Russia relies on, impacting on revenues and taxes.

14. These efforts are having a significant and demonstrable impact over time. Export and energy revenues are falling and foreign reserves remain immobilised. Russia’s military is less able to procure modern capabilities. Without the collective impact of sanctions, we estimate that Russia would have over $400 billion more to fund its war machine – enough to fund the invasion for a further 4 years.[footnote 8]

Case study: Professional and business services sanctions against Russia

In 2022, the UK introduced sanctions to prohibit the provision of professional and business services to a “person connected with Russia” across 8 sectors: accounting; advertising; architectural; auditing; business and management consulting; engineering; IT consultancy and design; and, public relations. Applying prohibitions to broad categories of services has been a major innovation in how we use our legislative powers.

They have been designed to degrade Russia’s medium-term ability to maintain, upgrade and modernise its economy. They deny access to key UK services that enable business activity in Russia, reduce the tax revenues available to the Kremlin and help ensure that oligarchs are no longer able to use our services expertise to support and legitimise their business activities.

Case study: Trade sanctions against Russia

Export sanctions are restricting Russia’s access to crucial goods and technology. The UK has banned the export of every item that Ukraine has found Russia using on the battlefield to date. These include electronics, aircraft parts, and radio equipment. We will ban any additional battlefield items that Ukraine brings to our attention.

Import sanctions are preventing Russian goods from entering the UK. We have targeted a wide range of products that could generate revenue for Russia, from oil and liquefied natural gas to gold and metals.

15. We are tackling Russia’s efforts to route activity through other countries to try and bypass sanctions. This is a shared G7 commitment.[footnote 9] We are tackling military procurement networks and third country supply and assistance to Russia. We are also working with third countries on the risks of circumvention – including calling their attention to any spikes in the trade of sanctioned goods – and on how to strengthen enforcement. We provide guidance to the UK financial and business sectors to help them spot common tactics and suspicious transactions or dealings used to circumvent our sanctions.[footnote 10]

16. We have made important early progress. Together with the US and EU, teams of UK officials have travelled to countries in Central Asia, Eastern Europe and the Gulf to share concerns and build relationships. The UK and its closest allies have published a list of items critical to Russia’s battlefield capability, the Common High Priority Items List. This allows companies and authorities in third countries to focus their efforts on limiting supply chains that are helping sustain the Russian war effort. We have designated military suppliers, including Iranian drone manufacturers, as well as individuals who help oligarchs obscure their wealth.

17. Our work to tackle circumvention complements broader UK efforts to clamp down on illicit finance and the environment that enables it. For example, complex corporate structures can be used deliberately to obscure the ownership of assets. The UK is working to improve transparency around beneficial ownership,[footnote 11] including via the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023. We will continue to prioritise efforts to support international partners on this agenda, as set out in the Economic Crime Plan 2.[footnote 12] We have also worked with the Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies to increase transparency of beneficial ownership. Reforms will support efforts to tackle the growing threat of illicit finance and corruption and help ensure more effective sanctions enforcement. Written Ministerial Statements laid in December 2023 detail commitments made by the Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.[footnote 13]

Case study: Financial fixers and oligarch enablers

Alongside allies, the UK has taken co-ordinated action to target Russia’s financial enablers. These are individuals and companies that help oligarchs hide their wealth through the professional services they provide, including through the formation of shell companies and offshore trusts. A new measure, introduced in 2023, aims to prevent these sorts of actors from accessing trust services. Our sanctions package in April 2023 targeted the network of financial fixers linked to Alisher Usmanov and Roman Abramovich, following joint work across government to uncover the oligarchs’ financial networks. Further packages have targeted those who are helping the Kremlin to circumvent sanctions.

18. The UK will continue to work actively with G7 partners to ensure Russia pays for Ukraine’s long-term reconstruction. We have legislated to enable us to keep sanctions in place until Russia pays compensation to Ukraine. We are pursuing all lawful routes through which sanctioned Russian assets can be used to support Ukraine. We have introduced requirements for sanctioned individuals and entities under our Russia regulations to disclose assets they own, hold or control in the UK, or worldwide if the sanctioned party is a UK national or entity. Those holding assets in the UK on behalf of the Russian Central Bank, Ministry of Finance and National Wealth Fund must disclose them to HM Treasury. We are developing a voluntary process whereby sanctioned individuals may apply for sanctioned funds to be released for the express purpose of supporting Ukraine’s recovery and reconstruction.

March 2023, Ukrainian and British artillery crews stand ready to fire as a cohort of Ukrainian recruits come to the end of their training conducted by officers and soldiers of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. Photo credit: Corporal Rob Kane; © Crown copyright 2023.

Addressing threats and malign activity through geographic and thematic sanctions regimes

19. Beyond the Russia context, the UK’s sanctions – including sanctions agreed at the UN – support wider priorities. These include protecting the UK’s national security and international peace and stability; limiting funding and arms to terrorist groups; and controlling the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction.

20. We will continue to use sanctions to respond to live threats and deteriorating situations. For example, since the killing of Mahsa Amini and the brutal crackdown on protests in Iran, we have co-ordinated with international partners and sanctioned over 90 individuals – helping further expose the human rights violations committed by the Iranian regime. Following the October 2023 attacks in Israel, in co-ordination with the US, we used our counter-terrorism sanctions to target Hamas leaders and financiers as part of wider efforts to disrupt Hamas’s terrorist activities. We have also used sanctions against financiers and arms dealers to the Myanmar military as well as to bear down on the Wagner Group’s malign activity in Mali, Central African Republic and Sudan.

21. We will continue to use sanctions to address serious abuses and violations of human rights globally and to tackle serious corruption. This relates to our use of ‘Magnitsky’ sanctions regimes as well as human rights provisions in specific geographical regimes.

Case study: Tackling conflict-related sexual violence

Conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV) shatters lives and scars communities around the world. The involvement in, and authorisation of, sexual and gender-based violence, including the systematic use of rape, breaches international law. The UK is committed to use all levers at our disposal to prevent and address CRSV, as set out in the UK’s strategy on Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative.[footnote 14] The UK has been at the forefront of using sanctions to target perpetrators of conflict-related sexual violence – including in Mali, Syria and Myanmar.

Case study: Corruption in Lebanon

Corruption at the highest political levels in Lebanon has contributed to poverty and economic hardship. The UK, the US and Canada sanctioned the former Governor of the Central Bank of Lebanon, Riad Salameh, along with his close associates, for their involvement in the diversion of over $300 million from the Central Bank of Lebanon. The UK froze at least £35 million of UK assets owned by Salameh. Following our co-ordinated sanctions, Lebanon’s authorities froze the assets belonging to Salameh and his associates and lifted banking secrecy laws protecting them.

Case study: Russian cyber criminals

Ransomware is a significant national security threat. It involves criminal groups encrypting systems to prevent access to files and threatening to publish data, then demanding a ransom for decryption. Ransomware can damage UK businesses and affect the lives and wellbeing of people in the UK. In 2023, alongside the US, the UK sanctioned 18 Russian cyber criminals – the culmination of a complex investigation led by the National Crime Agency (NCA). Those sanctioned were members of a gang behind the Trickbot/Conti ransomware attacks, which included the hacking of critical infrastructure and hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The gang sought to target UK hospitals, schools, local authorities and businesses. Our action blocked gang members’ ability to travel to the UK or have any dealings with UK entities. It exposed the names and faces behind the anonymous attacks with the aim of disrupting networks and discouraging others from taking similar action.

22. We continue to evolve and adapt our sanctions regimes to ensure sanctions remain a tool that is fit for purpose. We can modify or create regimes to address changing contexts and priorities (eg Iran in 2023) and can revoke sanctions regimes that are no longer meeting priority objectives.

Case study: New Iran sanctions powers

Iran continues to threaten the security and stability of other countries through weapons proliferation and its network of regional proxies. This includes Ukraine and UK partners in the Middle East. Iran has also sought to kill or kidnap individuals outside of Iran, including in the UK. In December 2023, we introduced a new sanctions regime, giving us extensive powers to disrupt Iran’s hostile activities in the UK and around the world.

23. We will continue to use our role as a permanent member of the UN Security Council to support the Council’s primary responsibility for maintaining international peace and security. We will continue to work alongside other partners to uphold our UN obligations and show leadership on UN sanctions. We have supported sanctions to tackle Daesh terrorists, help address conflict and destabilisation in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and to target violent gang activity in Haiti. We have countered and called out harmful efforts to erode or block sanctions, including Russia’s veto of the Mali sanctions regime. The geopolitical backdrop for securing agreement and making progress remains challenging. Nonetheless, it is vital for the international community to support an effective UN sanctions architecture to respond to current and future threats. We will continue to:

- initiate proposals for sanctions designations and work with our partners on sanctions proposals in areas of common interest

- ensure the UK fully implements UN sanctions, including arms embargoes, and responds to requests from UN Member States to assist them in implementation and enforcement

- deliver UK and international objectives through the renewal of UN sanctions mandates (for example, the UK’s lead on Yemen and Somalia), including to adapt UN sanctions to evolving situations and priorities and by creating new UN sanctions mandates (for example, Haiti in 2022)

- engage partner countries on how sanctions can best help realise their priorities – for example, controlling the flow of weapons or tackling terrorist groups

Case study: UN sanctions against al-Shabaab

The UK has been helping ensure the effective use of UN sanctions to address the ongoing conflict impacting Somalia and to tackle the operation of al-Shabaab in East Africa. This includes adapting an arms embargo to better respond to Somalia’s security needs and given the Federal Government’s own steps. Innovative measures on the charcoal trade have restricted al-Shabaab’s revenue generation alongside designations against al-Shabaab leaders and key operatives, with criteria widened in 2022 to enable the Security Council to address activity outside of Somalia’s borders and bolster regional security.

October 2023, the UN Security Council unanimously adopts Resolution 2701 (2023) on Libya sanctions. At the UN Security Council, new UN sanctions regimes are established and existing regimes debated. Photo credit: UN Photo/Loey Felipe.

Responsible design of sanctions

24. We will continue to design mitigations to minimise the risk of negative unintended consequences arising from sanctions whilst also upholding the effectiveness of our measures. UK sanctions do not target basic food or medicines and we place strong emphasis on the UK’s humanitarian priorities. We work with partners to understand the actual or potential impact of sanctions on, for example, the operations of humanitarian actors, the UK economy, or the global supply and trade of critical goods. Where particular risks are identified, we consider appropriate mitigations and can, for example, exclude items from trade restrictions or set out in legislation specific circumstances under which sanctions prohibitions would not apply.

25. As appropriate, we can issue licences to grant permission for certain activities to take place which would otherwise be in breach of sanctions. This permission can either be given to specific individuals or entities who apply for a licence, or via a General Licence that individuals and entities can use on an ongoing basis if they meet specific conditions. Following the 2023 earthquakes near the Turkey-Syria border, for example, we issued 2 General Licences to further facilitate humanitarian relief efforts. We have issued General Licences under our Russia Sanctions Regime, including to ensure delivery of humanitarian assistance to Ukraine and to help facilitate the shipment of Russian food and fertiliser around the world. We have also issued a General Licence for humanitarian activity in Gaza and the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

26. We will bring forward legislation when parliamentary time allows, to introduce a tailored humanitarian ‘exception’ across the UK’s financial sanctions. As set out in the 2023 White Paper on International Development,[footnote 15] this will provide further assurances to particular humanitarian actors and to the financial sector that they can conduct legitimate humanitarian activity and make appropriate payments in areas where sanctioned individuals operate or administer territory. This will build on the UK’s role in helping secure UN Security Council Resolution 2664 – a landmark step that introduced a cross-cutting exemption to the asset freeze measures across UN sanctions regimes to further support humanitarian delivery.

February 2023, the UK delivers humanitarian aid for people affected by the earthquakes in Turkey and neighbouring Syria. The UK issued 2 General Licences to facilitate humanitarian relief efforts in Syria. Photo credit: FCDO.

Section 3: Building international coalitions and working with the private sector, civil society and other stakeholders

27. Effective sanctions require strong partnerships. This applies equally to government-to-government relationships and to the relationship between government and the private sector and other stakeholders. We will continue to invest in building these partnerships to amplify the impact and reach of sanctions and to help inform, develop and improve both UK and collective sanctions activity.

28. Sanctions work best when multiple countries act together. The UK continues to prioritise international leadership as an innovative, effective and collaborative sanctions partner. We work with our closest allies and partners to build strong sanctions coalitions, including across the G7 nations and with our Five Eyes and EU partners. This has been particularly important when agreement at the UN Security Council has not been possible. This approach allows us to share and develop ideas, pool expertise and extend our collective reach to maximise the impact of our sanctions and close loopholes.

Case study: Collaboration with the US and EU

Our collaboration spans sanctions strategy, design, implementation and enforcement, and tackling circumvention.

The 2023 Atlantic Declaration highlights the strength and depth of the US-UK collaboration on sanctions and sets out joint priorities.[footnote 16] 2023 saw the inaugural UK-US strategic sanctions dialogue, with the US State Department hosting a cross-government UK team together with US departments and agencies for in-depth sessions.[footnote 17] This complements routine collaboration and specific initiatives such as staff secondments and the partnership between the UK Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation (OFSI) and the US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC).[footnote 18]

UK-EU co-ordination includes regular engagement at all levels with EU Institutions and Member States, including a regular Sanctions Coordinators Forum bringing together senior officials from the EU and G7 states. Working from UK embassies and posts, UK officials with sanctions responsibilities in EU Member States and in Brussels facilitate co-ordination and information sharing. The UK, EU and US conduct joint diplomatic outreach to a range of third country jurisdictions to encourage steps to reduce the risk of sanctioned goods reaching Russia.

29. We work with partners across the world on shared sanctions priorities. We have supported countries as they develop their sanctions capabilities and have shared expertise and experience on implementation and enforcement. We also engage with questions and concerns globally about how sanctions operate – including addressing misinformation and pushing back on active disinformation about the intent and impact of sanctions.[footnote 19]

30. The private sector is critical to making sanctions work. Industry is at the forefront of effective sanctions implementation and continuous improvement of sanctions policy and design. It is essential that businesses understand the action we have taken and why, and that they comply with sanctions without unnecessarily stopping legitimate activity. In turn, private sector insights and feedback help the UK government, including to assess and address potential and material implications of sanctions activity for the UK and global economy. Their input also contributes to our anti-circumvention efforts, including tracking and tackling efforts to dodge sanctions. We have regular dialogues with industry representatives at public and private events. We will continue to invest in engagement with businesses across all sectors of the economy affected by sanctions.

Case study: Oil price cap

The Oil Price Cap (OPC) targets Russia’s most lucrative revenue stream – the export of crude oil and refined oil products such as petrol and diesel. The OPC limits the price at which Russia can sell these products globally while using G7+ services. This puts downward pressure on Russian oil revenues, while at the same time protecting energy market stability. As well as joint work with the G7 and EU in co-designing the measure, close collaboration with industry played an essential role. We held a series of outreach events with the oil, shipping, insurance, legal and financial sectors to refine the design of the OPC, reaching out to over 100 stakeholders. Feedback continues to inform HM Treasury’s comprehensive guidance to companies involved in the movement of Russian oil. A year after it came into force, the UK led work to improve the OPC. This was announced across the G7+, with updated guidance for industry and a joint statement committing to a focus on enforcement and compliance.[footnote 20] Collaboration with partners and industry will continue as Russia tries to work around the OPC.[footnote 21]

31. Our relationships with humanitarian organisations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) also help mitigate any risks of unintended consequences and support compliance with UK sanctions. The UK Tri-Sector Group, for example, brings together representatives from 3 sectors – UK government and regulators, financial institutions and civil society organisations. It enables dialogue to support humanitarian priorities whilst ensuring compliance with counter-terrorism and sanctions legislation. We also work with NGO coalitions in areas such as human rights and anti-corruption, including receiving verifiable information to strengthen our evidence base for targeted sanctions.

Section 4: A robust sanctions system – due process

32. The Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018 (SAMLA) provides a transparent and robust system of legal challenge and review. The right to legal challenge is a hallmark of a fair, open and democratic society. Designated individuals or entities may request key relevant information, request a ministerial review or bring a challenge in court.

33. Judgments to date have established important legal precedents. Overall, they show we are upholding our approach of ensuring sanctions are well-reasoned, in line with the law, and justified in view of their important foreign policy objectives. Judgments also provide helpful clarification of how the courts will approach the legal tests set out in our legislation, which we will incorporate in our approach to future sanctions decisions. The SAMLA framework is relatively new and our domestic law in relation to sanctions continues to evolve.

34. We keep our regimes, designations and measures under review to adapt to new developments and changing circumstances. We will not sustain designations if we no longer consider that we have reasonable grounds to suspect that individuals or entities meet the criteria, and we keep measures under review to ensure they remain appropriate for achieving the purposes of the regulations. Since SAMLA was enacted in 2018, we have introduced new regimes and measures and we have also lifted sanctions and amended or revoked regimes where appropriate. We will continue to develop ways to assess the impact and effectiveness of our diverse sanctions programmes in different contexts.

Case study: A key court judgment

Belarusian technology company, LLC Synesis, was designated in 2020 in relation to Synesis’s supply of surveillance technology that provided the capability to track down civil society and pro-democracy activists. This amounted to involvement in the commission of serious human rights violations or abuse and/or the repression of civil society or democratic opposition in Belarus. Early in 2023, the High Court heard Synesis’s challenge against its designation, the first such Court Review under SAMLA. The High Court handed down its judgment in March, finding comprehensively in favour of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) on all grounds. This case and others have demonstrated both the robustness of UK sanctions designations and the fairness and transparency of our legal framework.

Section 5: An enhanced approach across government and reinforcing sanctions implementation and enforcement

35. Delivering the objectives in this strategy involves cross-departmental collaboration on sanctions policy, design, targeting, implementation, enforcement and lifting. In recent years, the UK has significantly expanded and deepened its sanctions capability; reinforced cross-government co-ordination; and increased investment in sanctions implementation and enforcement. The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office has overall lead on the use of sanctions as a tool of foreign and security policy under the UK’s legislative framework through the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018. The Department for Business and Trade, HM Treasury, the Department for Transport and the Home Office play a leading role designing trade, financial, transport and immigration sanctions respectively, in close collaboration with the FCDO. A range of other government departments provide expert input on specific sectors and issues.

36. Sanctions implementation and enforcement mobilises the expertise of multiple departments, agencies and regulators. A summary of roles and responsibilities across government can be found at Annex 2.

- the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation within HM Treasury is responsible for the implementation and civil enforcement of financial sanctions

- the new Office of Trade Sanctions Implementation in the Department for Business and Trade will be responsible for the implementation and civil enforcement of certain trade sanctions, working closely with HM Revenue and Customs who enforce sanctions on the import and export of goods at the UK border

- the Department for Transport is responsible for the implementation and civil enforcement of transport sanctions

- HM Revenue and Customs, the National Crime Agency and others, including the Serious Fraud Office and local police forces, all have a role to play in the criminal enforcement of financial, trade and transport sanctions

- the Home Office implements and enforces immigration sanctions, through the wider immigration system

Case study: Creation of the Office of Trade Sanctions Implementation

In December 2023, the Department for Business and Trade announced the creation of a new unit to strengthen the implementation and enforcement of trade sanctions. The Office of Trade Sanctions Implementation (OTSI) will issue guidance to support businesses to comply with UK trade sanctions and will investigate potential breaches. OTSI will have a range of civil enforcement tools including the ability to levy monetary penalties. Where OTSI investigates and potentially finds more serious breaches, it will refer these to HM Revenue and Customs or other agencies for criminal enforcement. OTSI will be operational later in 2024.

37. UK sanctions apply in full in all UK Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies, either by Orders in Council or through individual jurisdictions’ own legislation. The Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies are responsible for sanctions implementation and enforcement in their jurisdictions, and we collaborate with them to share understanding and expertise. At an annual sanctions forum, we bring sanctions practitioners from the Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies together with policy leads in UK government to build knowledge, skills and share best practice.

38. We continue to invest in sanctions staffing and expertise across government. For example, the FCDO established a Sanctions Directorate in 2022 and more than doubled the number of sanctions staff working on sanctions following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. There have also been staffing increases in other UK government departments and agencies.[footnote 22] We are investing in capability to ensure that all staff working on sanctions have the necessary skills, knowledge and tools. We have expanded our international network of UK officials with sanctions responsibilities who enable information sharing and co-ordination.

39. The Economic Deterrence Initiative is central to improved sanctions implementation and enforcement as part of a wider focus on economic security. In March 2023, the Prime Minister announced a new Economic Deterrence Initiative, with up to £50 million of funding to help strengthen our diplomatic and economic tools to respond to and deter hostile acts. This includes an emphasis on sanctions implementation and enforcement, as well as the development of wider economic tools designed to protect the UK and strengthen its economic security and resilience. We will continue projects under the Economic Deterrence Initiative as a central part of delivering this strategy. Examples of activity funded through the Initiative can be found at Annex 3.

Case study: Sanctions enforcement at the UK border

UK Border Force officers search a cargo container. Photo credit: Home Office.

HM Revenue and Customs and Border Force make checks at the UK border to ensure goods are not being imported or exported in breach of sanctions regulations. At UK ports and airports, Border Force will stop and check goods where they have suspicions. Red flags include whether there is any link to a country that is subject to UK trade restrictions, including whether the goods are destined for a country that is used as a route for circumventing sanctions; and whether the description of goods is purposefully opaque or misleading. Border Force may conduct checks with technical experts within the Department for Business and Trade to ascertain whether the goods are controlled under UK trade sanctions regulations and whether the appropriate licences have been obtained. If Border Force identify a breach of sanctions rules, the goods are seized and a Notice of Seizure is issued. Cases are referred to HM Revenue and Customs to undertake criminal investigations, issue fines and refer cases to the relevant prosecution authority as appropriate.

Annex 1: UK sanctions regimes

* Mixed UK/UN regimes are regimes that ensure the UK meets its UN obligations, but allow for additional UK sanctions to be imposed in addition to UN sanctions.

UK regimes

- Belarus

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Burundi

- China, Macao and Hong Kong (Arms Embargo)

- Guinea

- Iran

- Mali

- Myanmar

- Nicaragua

- Russia

- Syria

- Venezuela

- Zimbabwe

UN regimes

- Afghanistan

- Haiti

- Iraq

- Lebanon (Arms Embargo)

- Lebanon (Assassination of Rafiq Hariri and others)

- Syria (Cultural Property)

Mixed UK/UN regimes

- Central African Republic

- Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Guinea-Bissau

- Iran (Nuclear)

- Libya

- Somalia

- South Sudan

- Sudan

- Yemen

Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) regimes

- Armenia and Azerbaijan (Arms Embargo)

All regimes

- Afghanistan

- Belarus

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Burundi

- Central African Republic

- Chemical Weapons

- Counter-Terrorism (Domestic)

- Counter-Terrorism (International)

- Cyber

- Democratic People’s Republic of Korea

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Global Anti-Corruption

- Global Human Rights

- Guinea

- Guinea-Bissau

- Haiti

- Iran

- Iran (Nuclear)

- Iraq

- ISIL (Daesh) and Al-Qaeda

- Lebanon (Arms Embargo)

- Lebanon (Assassination of Rafiq Hariri and others)

- Libya

- Mali

- Myanmar

- Nicaragua

- Russia

- Somalia

- South Sudan

- Sudan

- Syria

- Syria (Cultural Property)

- Unauthorised Drilling Activities

- Venezuela

- Yemen

- Zimbabwe

The Armenia and Azerbaijan arms embargo and the China, Macao and Hong Kong arms embargo are implemented through the Export Control Order 2008.

Annex 2: Roles and responsibilities across government

Foreign policy (definition of high-level policy objectives, sanctions regime design and strategy):

The Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office has overall lead on foreign policy.

| Sanctions delivery area | Trade sanctions | Financial sanctions | Transport sanctions | Immigration sanctions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures policy: design of sanctions measures within regimes* | Department for Business and Trade Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office |

HM Treasury Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office |

Department for Transport Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office |

Home Office Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office |

| Designations: decisions to apply certain sanctions measures to specific individuals, entities and ships** | Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office | Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office | Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office | Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office |

| Implementation: licensing, engagement and guidance | Department for Business and Trade, including the Office of Trade Sanctions Implementation | HM Treasury’s Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation | Department for Transport | Home Office |

| Civil enforcement: investigations and civil monetary penalties | Department for Business and Trade’s Office of Trade Sanctions Implementation | HM Treasury’s Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation | Department for Transport | Home Office |

| Criminal enforcement: investigations and criminal prosecution |

HM Revenue and Customs Police and Serious Fraud Office |

National Crime Agency Police and Serious Fraud Office |

National Crime Agency Police and Serious Fraud Office |

Home Office Police and Serious Fraud Office |

*There are a range of other departments that provide sector-specific advice on sanctions to inform policy, implementation and enforcement, including but not limited to: Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport; Department for Energy Security and Net Zero; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs; Department for Science, Innovation and Technology; Ministry of Defence; Ministry of Justice.#

**HM Treasury leads on designations under the UK’s domestic counter-terrorism sanctions regime.

Annex 3: Examples of how the Economic Deterrence Initiative will strengthen the effectiveness of UK sanctions

-

Establishment of the new Office of Trade Sanctions Implementation, which will work with partners across government and in industry to help ensure that businesses understand trade sanctions, and that they are properly implemented and enforced.

-

Reinforcement of the Office of Financial Sanctions Implementation, particularly through enhanced capability to implement novel financial sanctions, including the Oil Price Cap.

-

Additional support for HM Revenue and Customs to investigate and prosecute the most serious sanctions breaches, including expanded intelligence and data functions.

-

Specialist capability within the Joint Maritime Security Centre and the National Crime Agency, increasing the UK’s ability to detect and respond to breaches of maritime and transport related sanctions.

-

Work to expand the range of penalties that can be imposed for breaches of sanctions measures, to give our sanctions additional teeth.

-

Major investment in building lasting sanctions capability across government, recognising the specialist skills and expertise required.

-

Investment in our ability to manage sanctions litigation, through the establishment of specialist teams.

-

Expansion of the network of sanctions specialists in UK diplomatic missions to build collaboration with third countries and support intensified efforts to tackle sanctions circumvention.

-

A programme of targeted technical assistance for third countries, co-ordinated with EU and US partners.

-

Support to the Overseas Territories to strengthen their sanctions enforcement architecture.

Footnotes

-

HM Government. Integrated Review Refresh 2023 (PDF, 11.3 MB), March 2023 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

HM Government. Integrated Review Refresh 2023 (PDF, 11.3 MB), March 2023, page 4 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

Changes to primary legislation have also reinforced the UK’s sanctions framework. The Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Act 2022 amended SAMLA to enable designations to be made under urgent procedure, for a limited period of time, if they align with designations made by our partners and are in the public interest. The Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Act 2023 also amended SAMLA to enhance our ability to use Civil Monetary Penalties. ↩

-

Sanctions can be defined as publicly stated prohibitions and requirements that a state or groups of states impose to achieve specific foreign and security policy objectives, which legally limit the ways in which those in their jurisdiction can interact with target states, entities or individuals. The UK’s sanctions powers are contained within the Sanctions and Anti-Money Laundering Act 2018. They sit within the UK’s wider economic statecraft toolkit which includes other tools such as strategic export controls, tariffs and action through multilateral fora. ↩

-

HM Government. The Export Control Order 2008 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

For example, principles contained in ‘Annex to G7 Statement on Support for Ukraine’, June 2022 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

HM Government Analysis of Public Economic Data. ↩

-

HM Government Analysis of Public Economic Data. ↩

-

HM Government. G7 Leaders Statement, February 2023 (viewed on 22 January 2024). “We call on third-countries or other international actors who seek to evade or undermine our measures to cease providing material support to Russia’s war, or face severe costs. To deter this activity around the world, we are taking actions against third-country actors materially supporting Russia’s war in Ukraine”. ↩

-

For example, NCA warns of abuse of gold to evade sanctions - National Crime Agency. HM Government, November 2023 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

Beneficial ownership transparency refers to the requirements for corporate vehicles to collect and disclose information about their true beneficial owners in a register. ↩

-

HM Government. Economic Crime Plan 2 (2023 to 2026) (PDF, 1.6 MB), March 2023 (viewed on 22 January 2024). This also includes HM Treasury’s provision of technical assistance through the Financial Action Task Force - the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog. ↩

-

HM Government. Update on the implementation of publicly accessible registers of beneficial ownership in the Overseas Territories: Written statements - Written questions, answers and statements - UK Parliament, December 2023; Update on beneficial ownership transparency in the Crown Dependencies: Written statements - Written questions, answers and statements - UK Parliament, December 2023. ↩

-

HM Government. Preventing Sexual Violence in Conflict Initiative strategy, November 2022 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

HM Government. International development in a contested world: ending extreme poverty and tackling climate change, a white paper on international development, November 2023, pages 112 and 115 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

HM Government. The Atlantic Declaration (PDF, 144 KB), June 2023, pages 5 and 6 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

HM Government. Written statement by British Ambassador to the USA on the inaugural UK-US strategic sanctions dialogue, July 2023 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

For example, One Year On: The OFAC-OFSI Enhanced Partnership. HM Government, November 2023 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

For example, Global food security and Russia sanctions: EU-US-UK joint statement. HM Government, November 2022 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

HM Government. UK Maritime Services Ban and Oil Price Cap: Industry Guidance (PDF, 1.5 MB), December 2023 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

HM Government. G7 Leaders’ Statement, December 2023 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩

-

For example, OFSI Annual Review 2022 to 2023. HM Government, December 2023 (viewed on 22 January 2024). ↩