Cyber Essentials scheme process evaluation

Published 22 June 2023

Executive summary

The modern digital age presents significant opportunities for organisations, as well as complexities and risks. The UK government, as part of its commitment to making the UK the safest place in the world to start and grow a digital business, has set out ambitious policies to protect the UK in cyberspace. These are set out in its National Cyber Strategy 2022.

The government-owned Cyber Essentials scheme aims to help organisations of all sizes defend themselves against the most common cyber threats and reduce their online vulnerability. It defines a focused set of five technical controls which offer cost-effective, basic cyber security, via two levels of certification:

-

Cyber Essentials (CE): The basic verified self-assessment option

-

Cyber Essentials Plus (CE Plus): As above, but independent technical verification is also carried out by the Certification Body

Cyber Essentials is operated in partnership between the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT)[footnote 1] and the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). It is delivered through the IASME Consortium Ltd. (IASME).

The government wishes to increase the number of organisations holding Cyber Essentials.

A total of 132,094 Cyber Essentials certificates have been awarded since the scheme began. IASME’s latest records (as of the end of May 2023) show a total of 27,027 unique Cyber Essentials certified organisations across the UK in the past 12 months, with 35,434 total certifications awarded in the past 12 months. The difference between the two figures denotes 8,407 Plus certifications which are counted additionally to standard Cyber Essentials certifications.

Analysis shows steady year-on-year-growth, for example fewer than 500 certificates were issued per month in January 2017, rising to just under 3,500 in the month of January 2023.

Since Cyber Essentials certification is renewed annually, it is important to note that the figures in the preceding two paragraphs do not take into account any that may have lapsed.

Throughout this report, the term Cyber Essentials is used to refer to the overall scheme (including both levels mentioned above) and the separate terms CE and CE Plus are used when referring to one particular level.

Evaluation aims

In December 2022, the (then) Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), commissioned Pye Tait Consulting to undertake a process evaluation of the Cyber Essentials scheme. This is supplemented by a feasibility study for a subsequent impact evaluation to be conducted at a later date. The findings are intended to enable DSIT, NCSC and IASME to ascertain whether the current implementation approach is working and allowing the scheme to meet its objectives.

Methodology

The evaluation methodology comprised the following main components:

-

Rapid desk research to understand relevant policy, developments and existing research and evaluation findings in relation to Cyber Essentials (January 2023)

-

12 qualitative interviews with strategic stakeholders that have close involvement with Cyber Essentials, including representatives from government and industry (UK, including devolved nations) as well as IASME, NCSC and a sample of former Accreditation Bodies. (January 2023)

-

Online survey of Certification Bodies[footnote 2] (95 responses), representing a 30% response rate of the total population of 315 mailed Certification Bodies

-

Online survey spanning current Cyber Essentials users (528 responses) and lapsed Cyber Essentials users (47 responses)

-

Small-scale phone survey of organisations that had never held Cyber Essentials (74 responses based on a 60-85 target)

Cyber Essentials decision-making

Among surveyed current and lapsed users, the standard CE certification is the most commonly held. CE Plus is more prevalent among large organisations, for which it accounts for just over half (51%) of certifications, compared to just 17% among micro organisations.

The small sample of lapsed users had held their certification for varying lengths of time, with drop-offs highest after the first year (45%) then 32% after two years and 21% after three or more years.

Among micro organisations, overall responsibility for certification is most commonly handled by the owner or manager. The larger the size-band of the organisation, the more common it is to place overall responsibility for Cyber Essentials certification in the hands of a dedicated in-house IT or data security specialist.

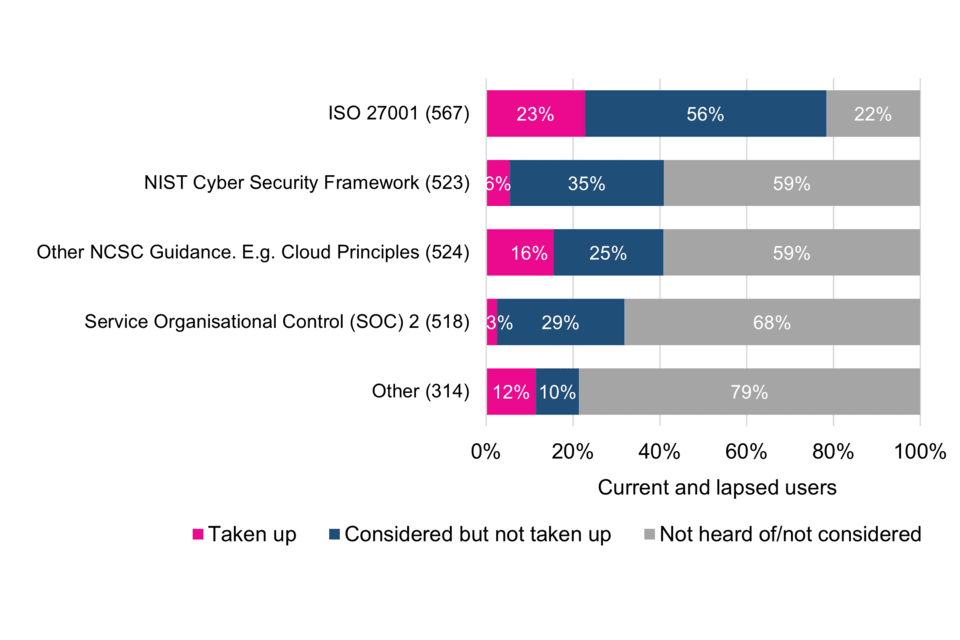

With the exception of the ISO 27001 standard on Information Security and Management, which more than half (56%) of Cyber Essentials users had considered and a further 23% taken up, most had not heard of or considered other specific schemes and standards asked about in the survey.

Some organisations believe that Cyber Essentials provides a benchmark standard that companies ought to naturally strive for, even if considering other security schemes or standards such as ISO 27001. Others reflected on the differences between Cyber Essentials and other schemes, indicating that they each have their own place in the market.

Qualitative insights reveal that Cyber Essentials is broadly regarded by users as a basic and accessible security standard compared to other schemes or standards. However, large organisations in particular expressed the view that ISO 27001 is more rigorous and appropriate to their setting.

Factors driving Cyber Essentials certification

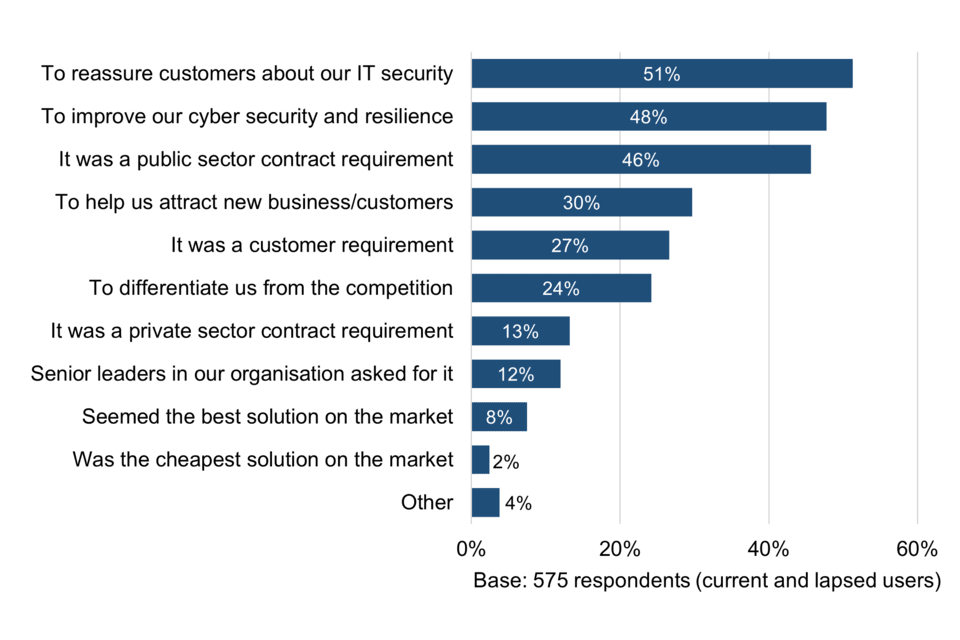

When asked why their organisation first decided to become Cyber Essentials certified, current and lapsed users mentioned a range of factors, including those which are reactive to others’ requirements and perceived needs, and those which are proactively aimed at benefiting their own organisation.

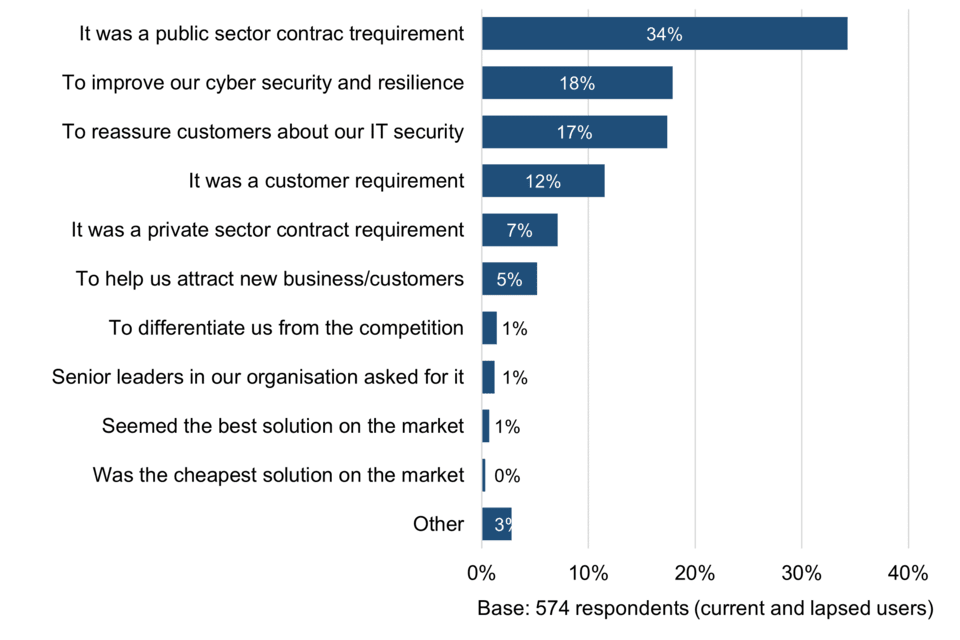

The most common single main reason (mentioned by just over a third, 34%) is that Cyber Essentials is a requirement of a public sector contract. Micro businesses in particular appear to be less strongly motivated by improving their own cyber security and resilience, and more strongly motivated by external influencers such as customer or contractual requirements. This suggests that Cyber Essentials certification is, in some cases, serving as a means to an end – a view also reflected in some of the qualitative feedback.

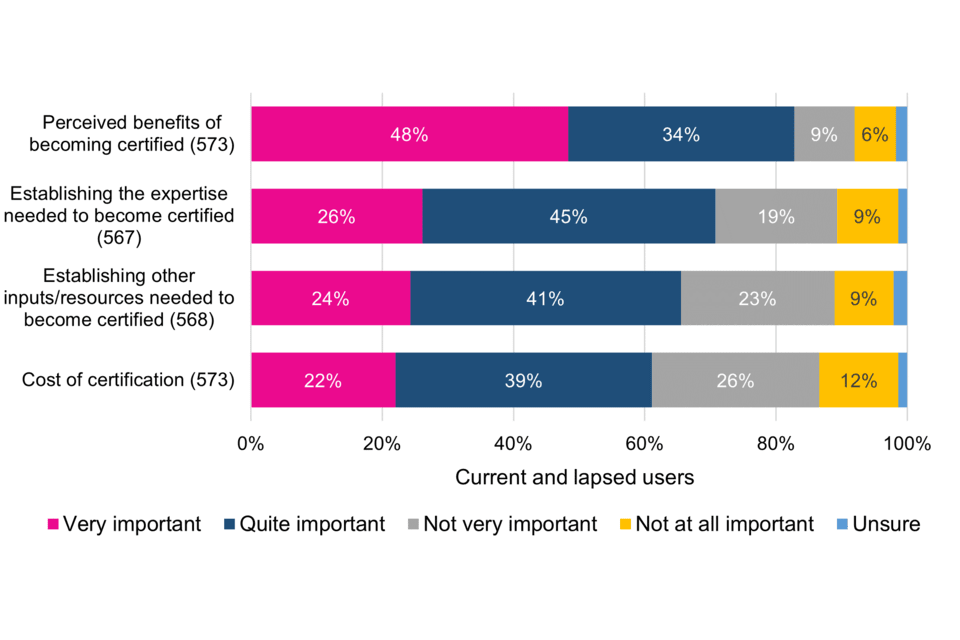

The majority of respondents (82%) consider it important to understand the perceived benefits of becoming Cyber Essentials, and most also place importance on planning various logistical inputs in terms of expertise, resources and costs. This makes it essential that organisations are clear from various information and guidance what the Cyber Essentials scheme expects of them.

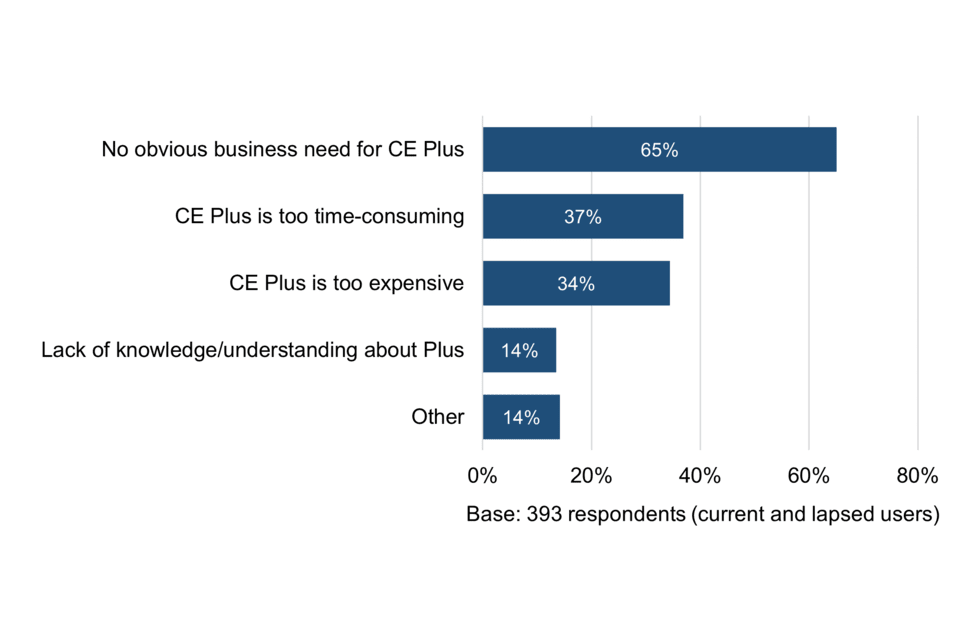

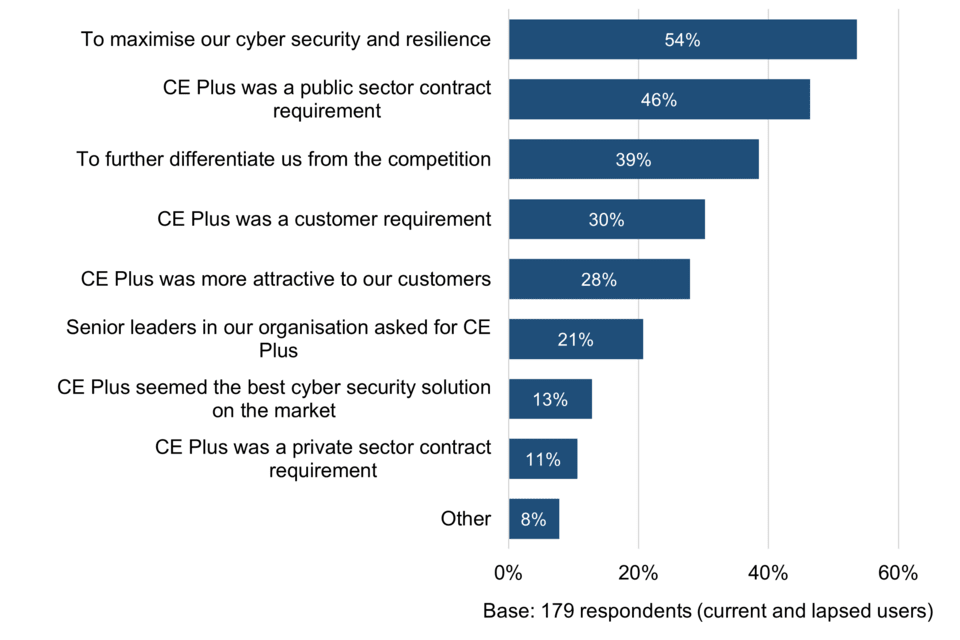

The most prominent reason for current and lapsed users opting for CE as opposed to CE Plus was that they saw no obvious need for CE Plus (65% of respondents). Conversely, most of those opting for CE Plus did so to maximise cyber security and resilience (54%).

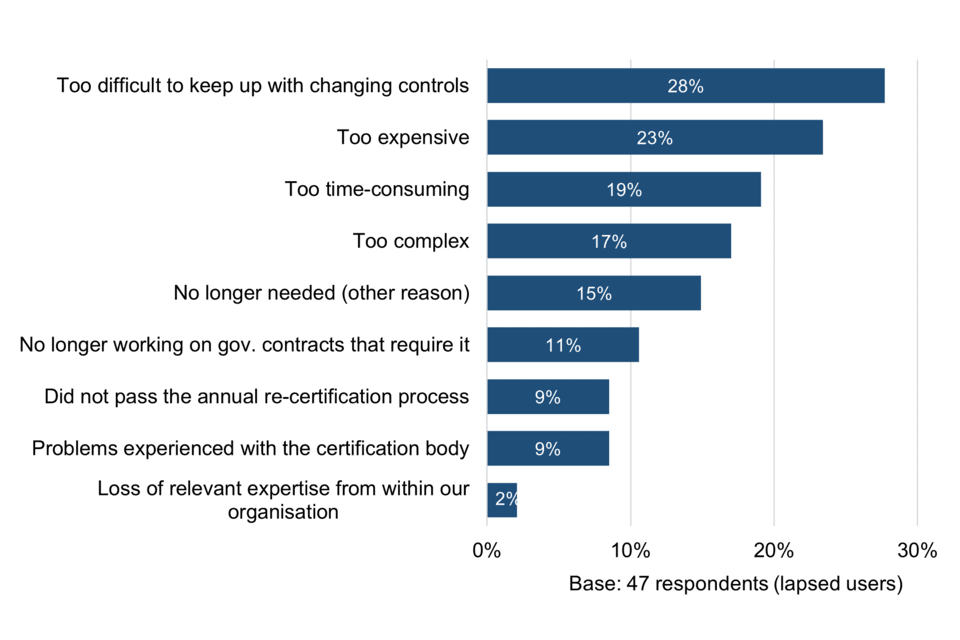

The top three reasons for Cyber Essentials certification lapsing, each mentioned by a minority of respondents, are that it was too difficult to keep up with changing controls (28%), too expensive (23%) and too time-consuming (19%). This points to some challenges in a scheme which by its very nature is prescriptive rather than risk-based.

Cyber Essentials information and guidance

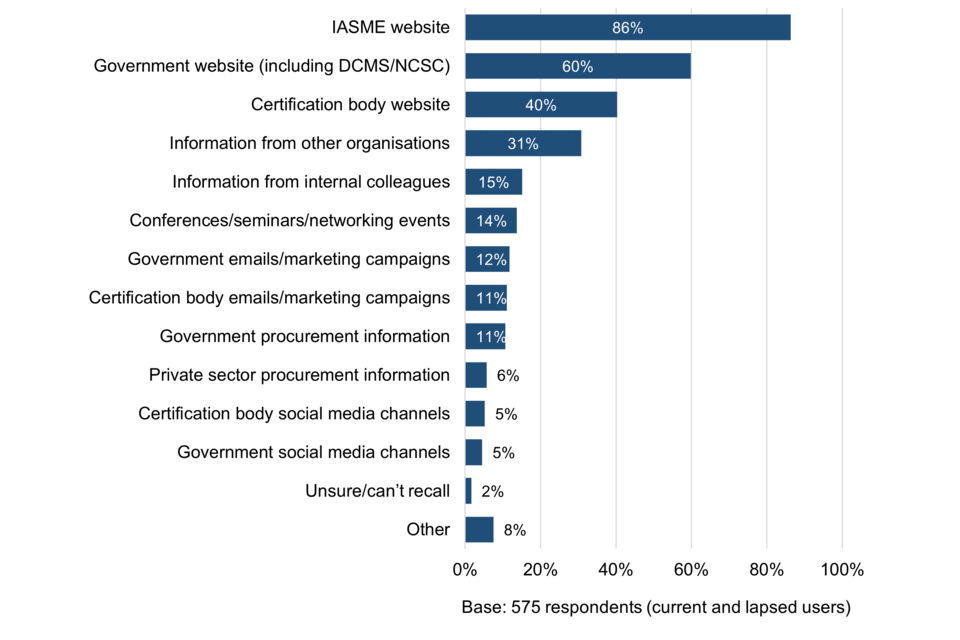

The most widely accessed information and guidance sources about Cyber Essentials include the IASME website, followed by NCSC, DCMS and Certification Body websites. This suggests that organisations are generally accessing information from trusted sources. Large organisations are more inclined to draw on a wider range of sources including conferences, seminars and networking events.

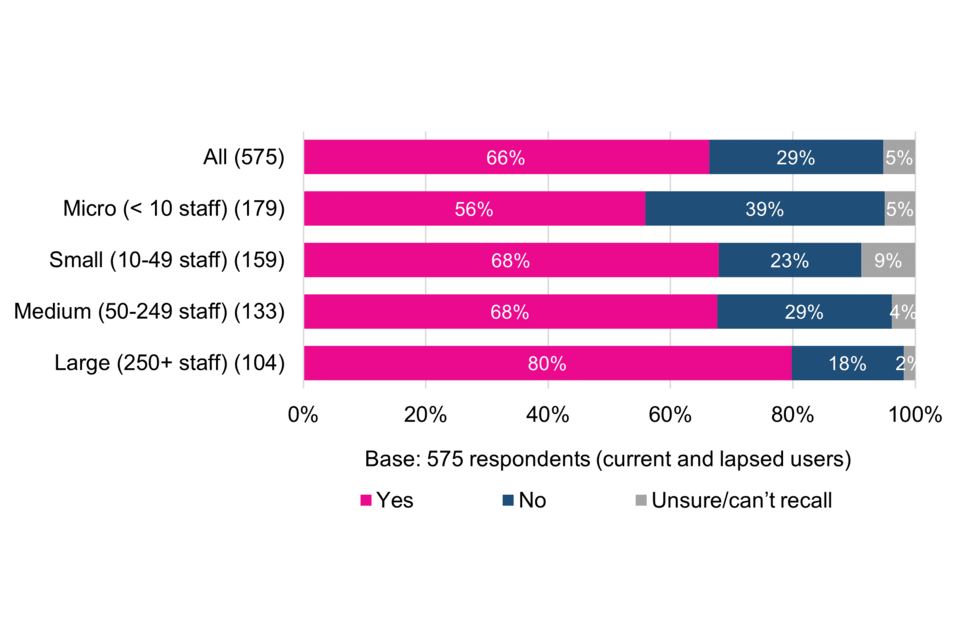

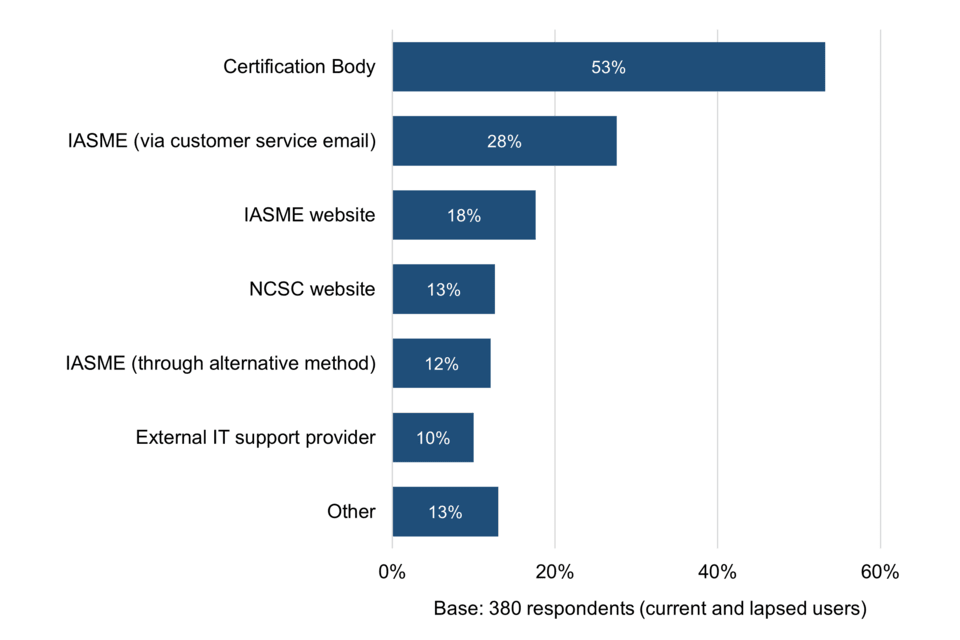

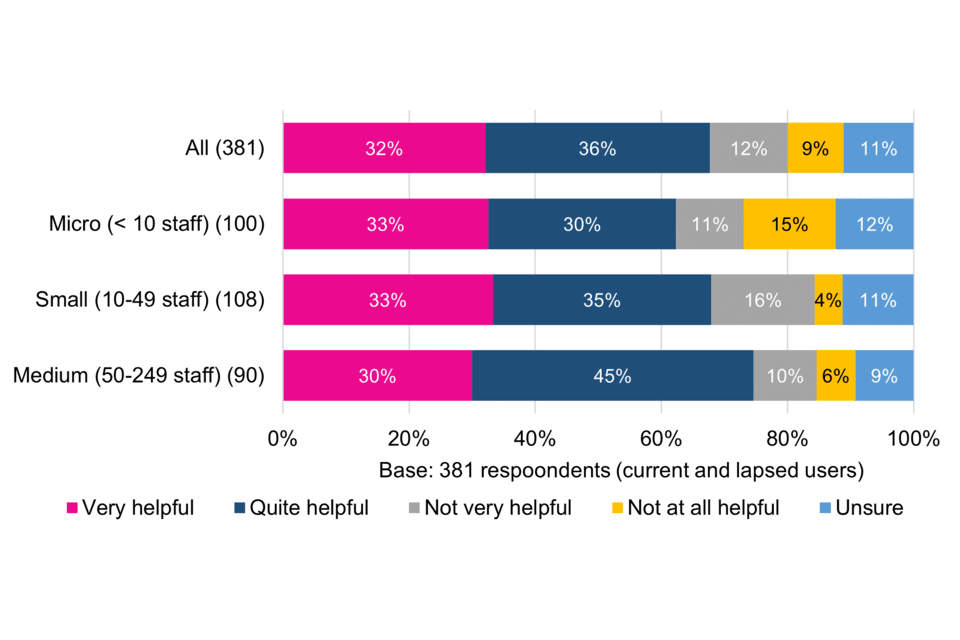

Two thirds of current and lapsed users (66%) needed to ask questions or seek help during the certification process. The figure is 80% among large organisations, indicating a need for more bespoke support appropriate to the complexities of their organisation. The most common place to turn to is the Certification Body (53%), making it important that Certification Bodies are open and willing to provide the assistance needed to help organisations achieve the ultimate end goal of becoming more cyber resilient.

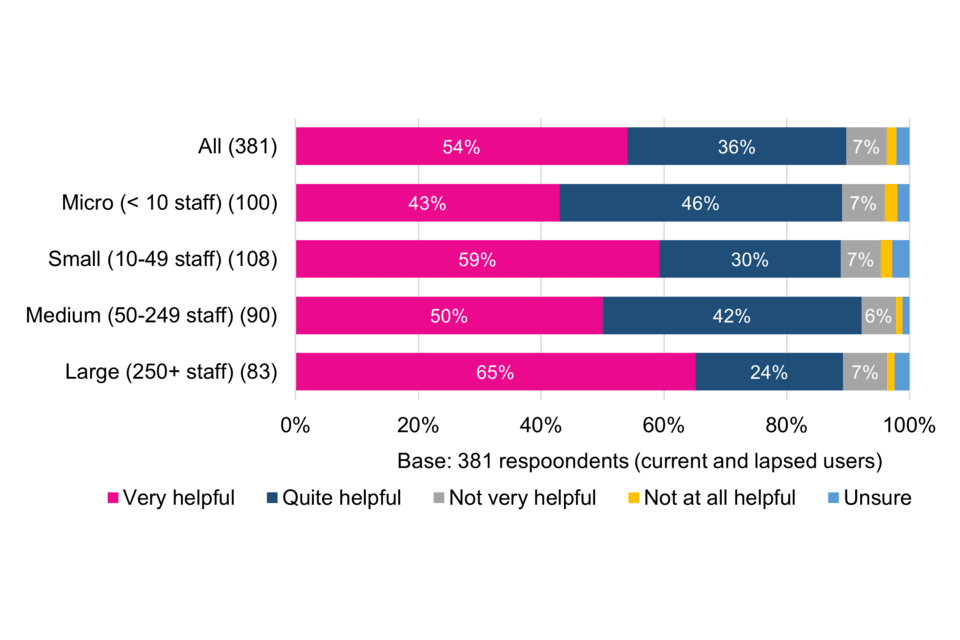

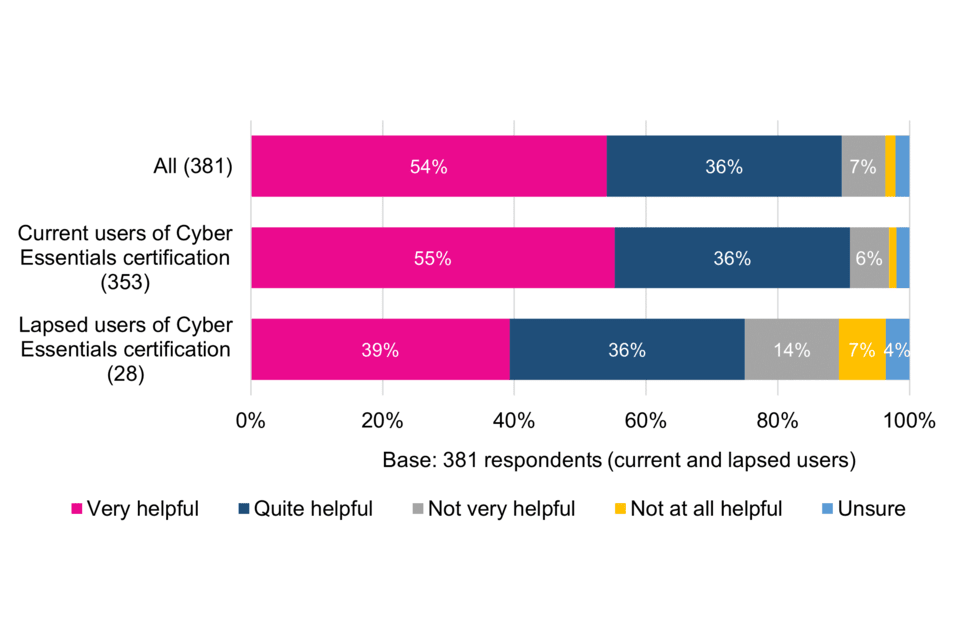

Support during the certification process is generally viewed positively, with more than half of respondents (54%) describing it as very helpful and 36% quite helpful. More than a fifth (21%) of lapsed users describe support as not very or not at all helpful – three times higher than the proportion of current users – which may have contributed to these organisations’ decisions not to renew.

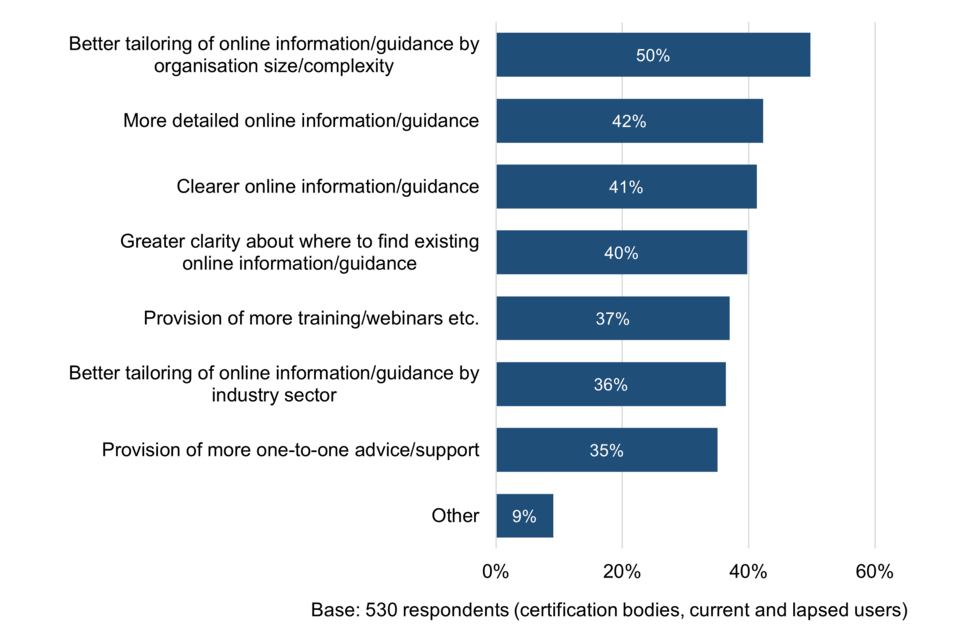

Some concerns raised by survey respondents are that existing scheme guidance adopts a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach which does not adequately speak to or benefit certain types and sizes of organisation. Indeed, half of current and lapsed users (50%) would like to see better tailoring of online information and guidance by organisation size or complexity, followed by more detailed guidance (42%) and clearer guidance (41%).

The majority also call for greater clarity around Cyber Essentials assessment requirements, especially where elements can be too easily open to interpretation. For their part, several Certification Bodies stressed the need to provide more foundational information to help users understand the importance of cyber security and threats in a more general sense.

Cyber Essentials customer journey

The overall cost and time involved for organisations to obtain certification varies considerably between organisations and especially between size-bands. The overall mean spend (excluding outliers) is estimated at £4,941. This factors in resources needed to meet the technical controls such as consultancy support and changes to hardware, software and updated policy implementation.

Whilst cost and time were not among the main difficulties cited by users in their customer journey, the fact that these featured among the top three reasons for certification lapsing suggests that cost and time stresses are almost certainly being felt by some organisations. This points to a potential need to review the pricing structure for Cyber Essentials.

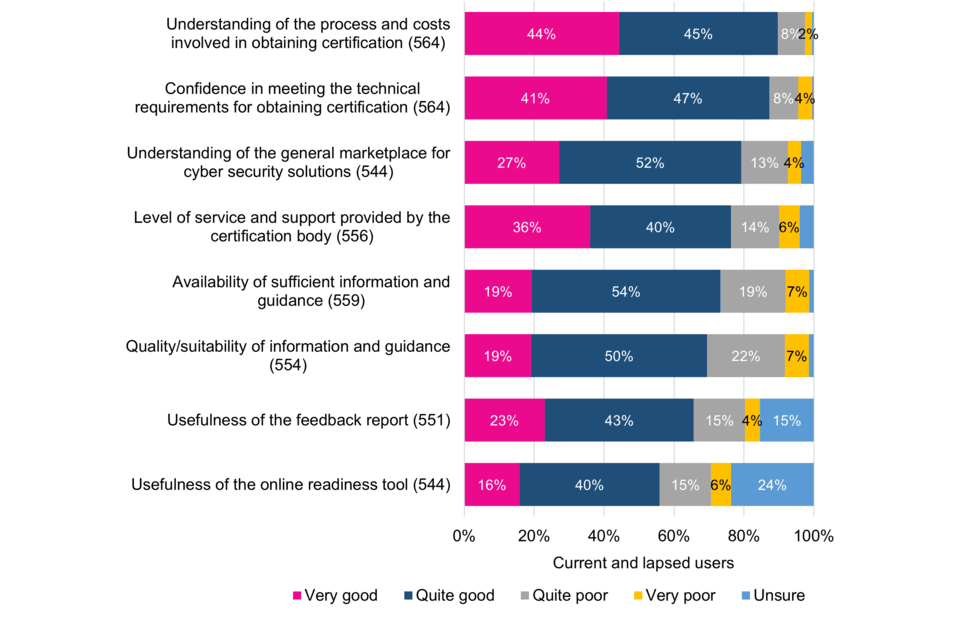

On the whole, most surveyed current and lapsed users have had a positive certification experience, with the majority rating various specific aspects of the customer journey as very or quite good. However, and building on the previous section, the quality and suitability of information and guidance is considered by more than a quarter (29%) to be very or quite poor.

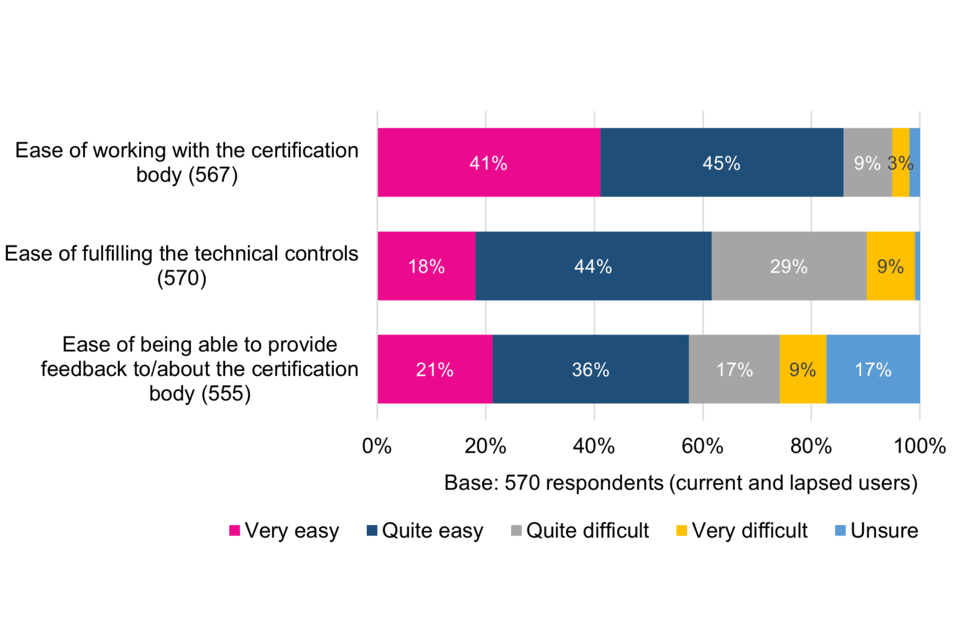

The vast majority of surveyed current and lapsed users (86%) report working with their Certification Body to have been very or quite easy, which is important given the reliance many organisations place on their Certification Body for support. However, views are more divided on the ease of fulfilling the technical controls. Whilst the majority (62%) consider this very or quite easy, more than a third (38%) do not.

Qualitative insights reveal that the most positive aspects of the customer journey relate to: i) feedback, support and guidance from Certification Bodies and assessors; ii) ease of completing the process; and iii) improving security. The most difficult aspects relate to: i) lack of clarity or understanding of aspects of the process; ii) difficulties meeting the technical controls; and iii) keeping up with changes.

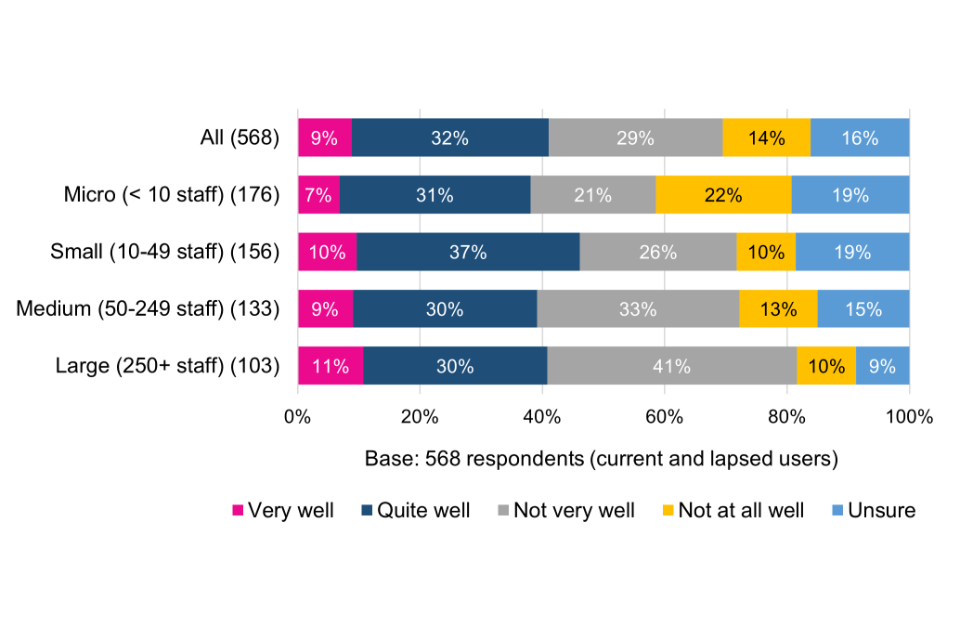

On a perceptual scale from 1 (not at all appropriate) to 10 (completely appropriate) organisations rate the technical controls at a moderate 7.1. Among micro and large organisations, the means are lower (6.6 and 6.5 respectively) – a significant difference. There appear to be distinct issues facing the largest and smallest organisations. For large organisations, the controls can be difficult to implement at scale due to IT infrastructure complexities. For micro organisations, the main challenge lies in the perceived cost, time and expertise required to implement them, especially where they lack access to an expert IT resource.

Academic institutions also appear to face unique barriers, as evidenced from this and other research. The prevalence of Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) practices in these settings has led to some of these organisations expressing concern about their perceived ability to meet the requirements of Cyber Essentials.

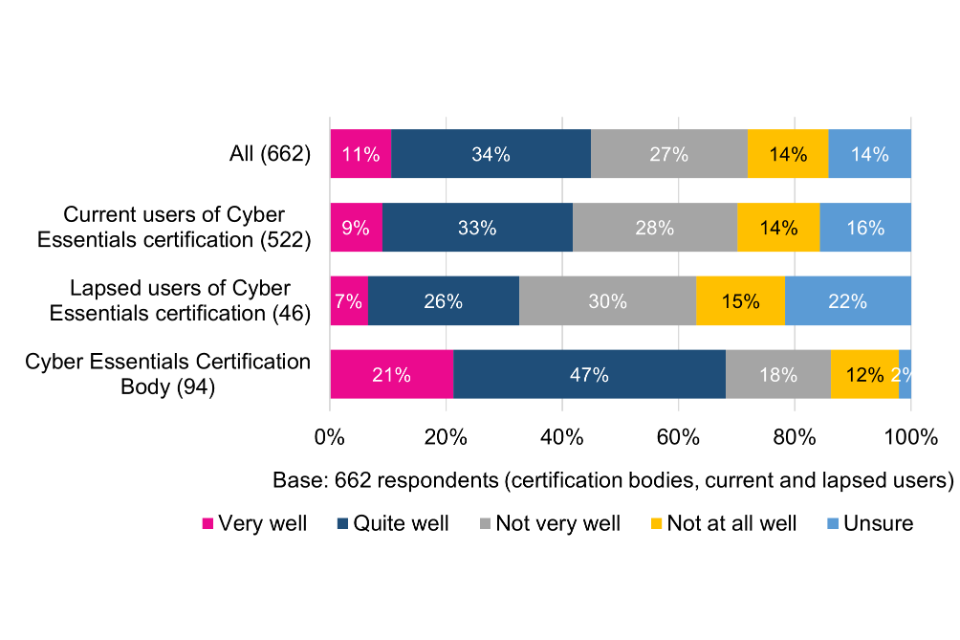

There is a significant difference between the perspectives of Certification Bodies and of current and lapsed users in how well changes to control arrangements are communicated. Only a minority of current and lapsed users consider changes to have been communicated very or quite well, which points to a possible disconnect in how well Certification Bodies believe certain communications have been deployed compared with the user base.

Cyber Essentials scheme effectiveness and improvement

With respect to Cyber Essentials scheme governance, strategic stakeholders say partnership working has increased. They suggest that it could be strengthened by a greater commitment to transparency, sharing information that would benefit all parties, and taking on board feedback with a view to making changes that would serve the greater good.

In terms of scheme implementation, strategic stakeholders (representatives from government and industry) stressed the challenge of the current ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach where there are quite different challenges to implementing cyber security measures by organisations of different types, sizes and sectors. As such they advocate more in-built flexibilities where this would be possible. The Pathways pilot project (cf. section 1.2) is one example of this.

In relation to consistency of work between Certification Bodies, a minority of stakeholders questioned the appropriateness of Certification Bodies fulfilling the dual roles of assessor and advisor to organisations seeking certification. However, this argument needs to be balanced against the importance users place on the support they get from Certification Bodies and the ultimate goal, which is about building organisations’ protection against threats.

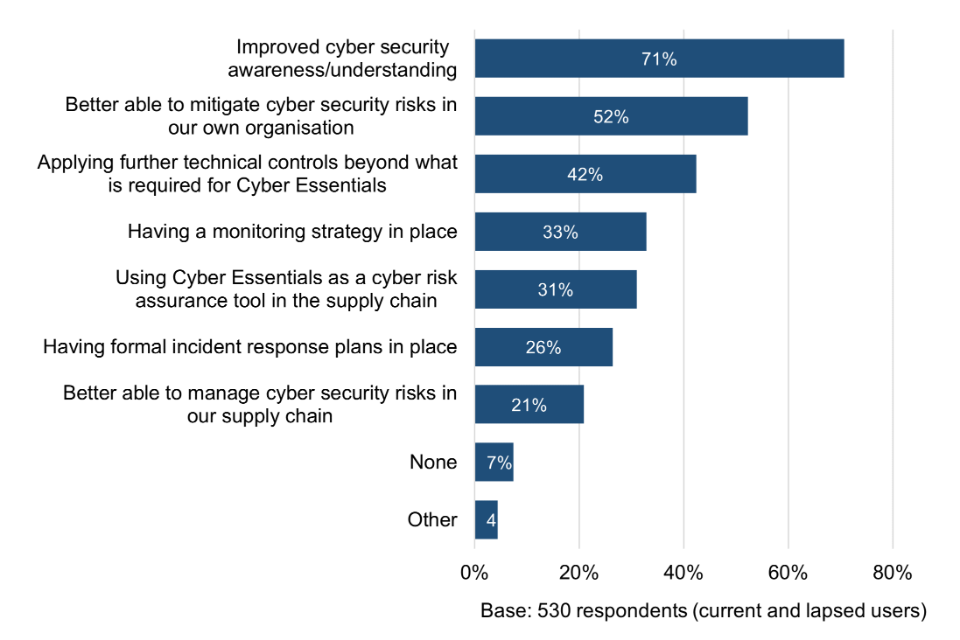

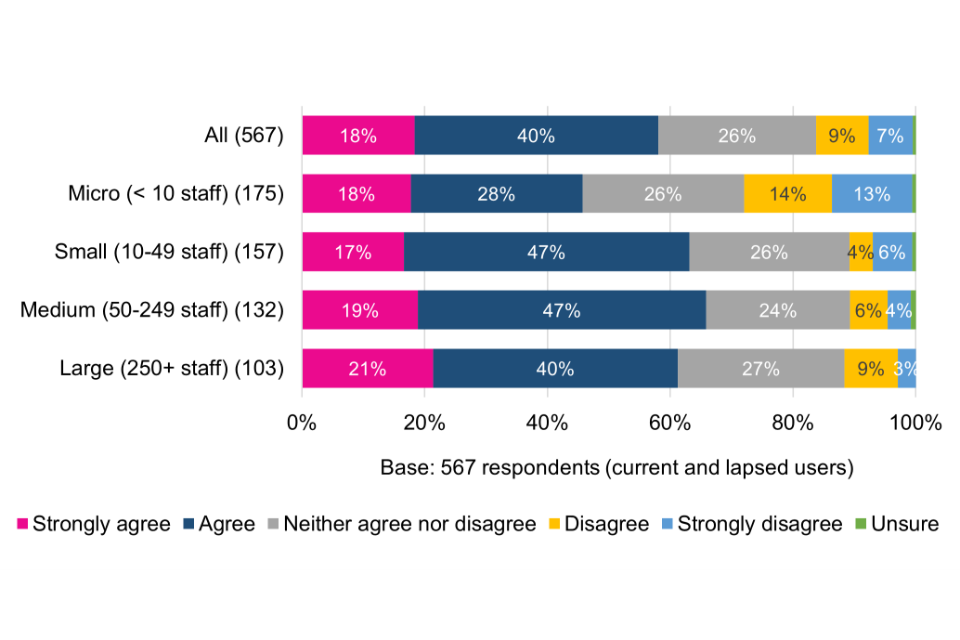

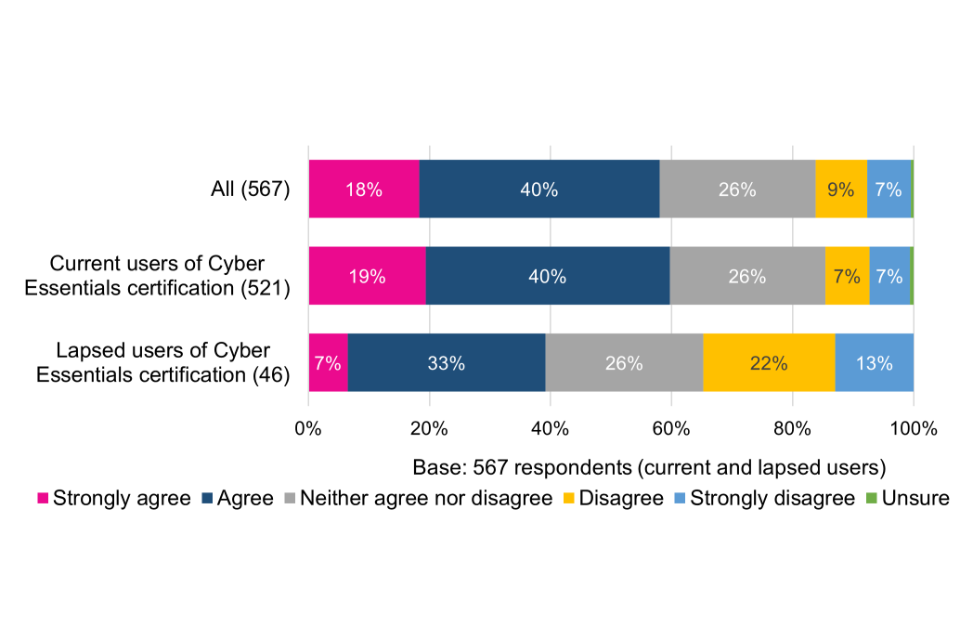

The majority of current and lapsed users believe that going through the Cyber Essentials process has improved their cyber security awareness and understanding (71%) and, as a result, they are better able to mitigate cyber security risks in their own organisation (52%).

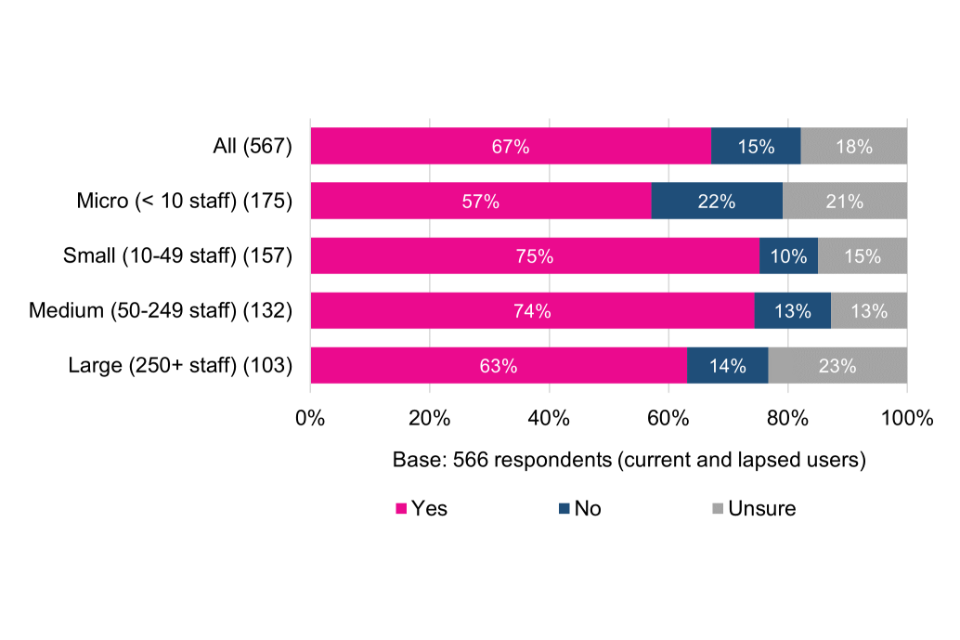

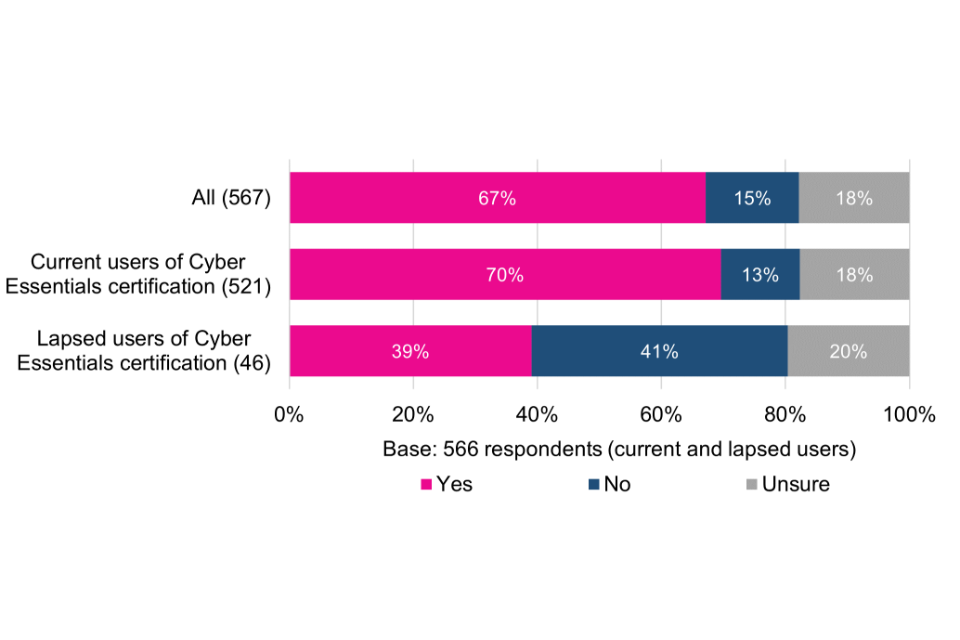

Just over two thirds (67%) would recommend Cyber Essentials to others. These users, especially registered charities and trusts, view the scheme as cost-effective and accessible. Users that would not recommend Cyber Essentials to others do not typically believe that the controls are applicable or relevant to the workings of their own organisation. This points to a need to consider how, if at all, the controls could be more flexible or adaptable.

Current and lapsed users were asked to what extent they agree that the Cyber Essentials scheme overall represents good value for money. The emerging picture is mixed. While the majority (58%) strongly agree or agree, just over a quarter (26%) are ambivalent and a minority (16%) disagree or strongly disagree. This offers an opportunity to help organisations better understand what they are getting in return for their investment.

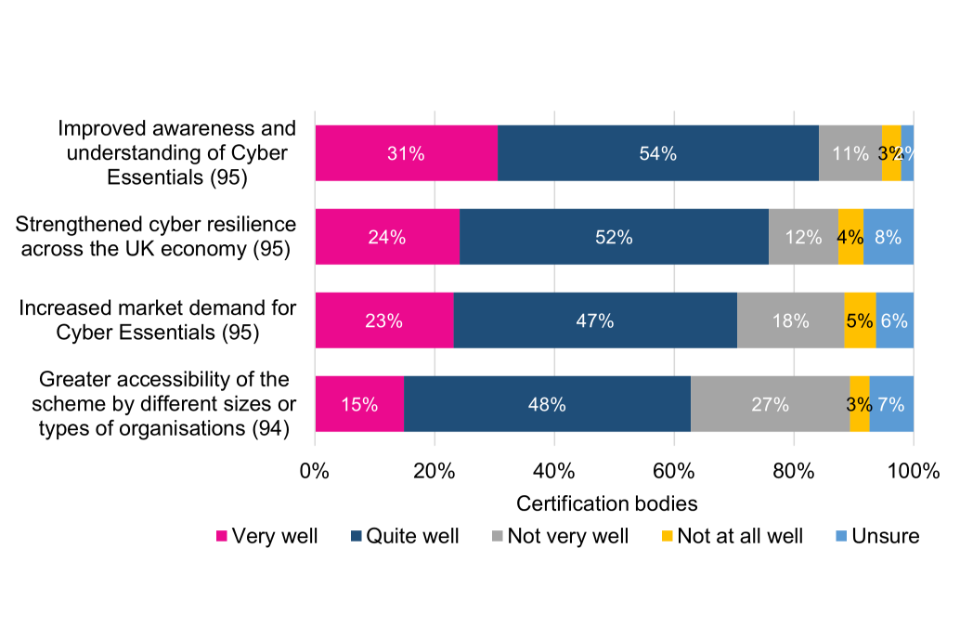

Certification Bodies, which were also asked about the scheme’s effectiveness and improvement, compliment it for providing an effective and accessible security baseline for certified organisations. However, a key perceived challenge is that users and potential users lack a sufficiently detailed understanding about cyber security. These findings emphasise the importance of more effectively conveying to current and prospective users the importance of cyber security, why they should take it seriously and how Cyber Essentials provides a cost-effective solution to starting that journey.

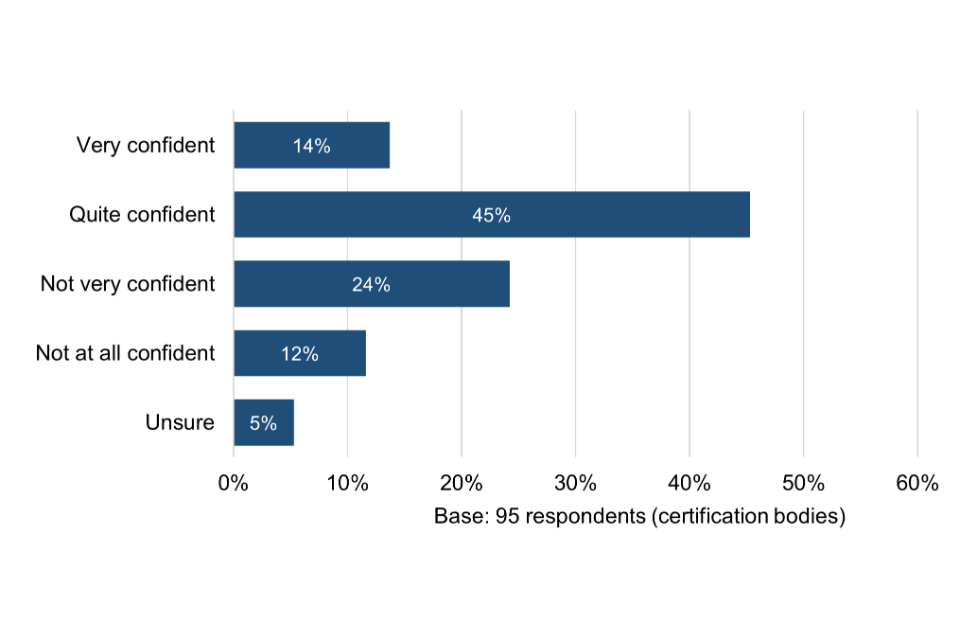

The majority of Certification Bodies (59%) are very or quite confident that the Cyber Essentials scheme is being delivered consistently by different Certification Bodies, although 36% are not very or not at all confident. Most mentioned differing requirements, standards and capabilities between Certification Bodies as being potential reasons for lack of consistency.

All surveyed organisations were asked in what ways they think the Cyber Essentials scheme could be improved in the future, with suggestions falling into the following five main themes: i) better tailoring and scalability; ii) improvements in communication, guidance and support; iii) reduced cost; iv) quality and scrutiny of assessments; and v) synergy with other security schemes.

Non-users of Cyber Essentials

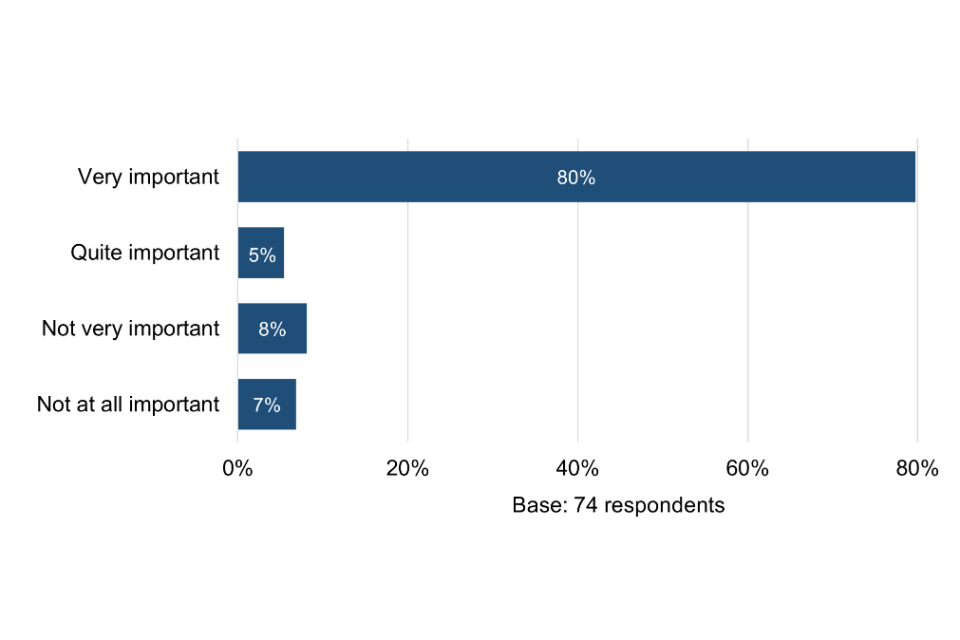

Among 74 surveyed organisations that have never held Cyber Essentials, eight in ten consider cyber security very important to their organisation. However, of the 15% answering not very or not at all important, all are micro organisations. These businesses could therefore be the hardest to engage in terms of future take-up.

The minority stating ‘not very or not at all important’ mentioned mainly doing business on their phone, doing little business online, using paper-based records, being content to use free internet security software and in one case not trusting the government.

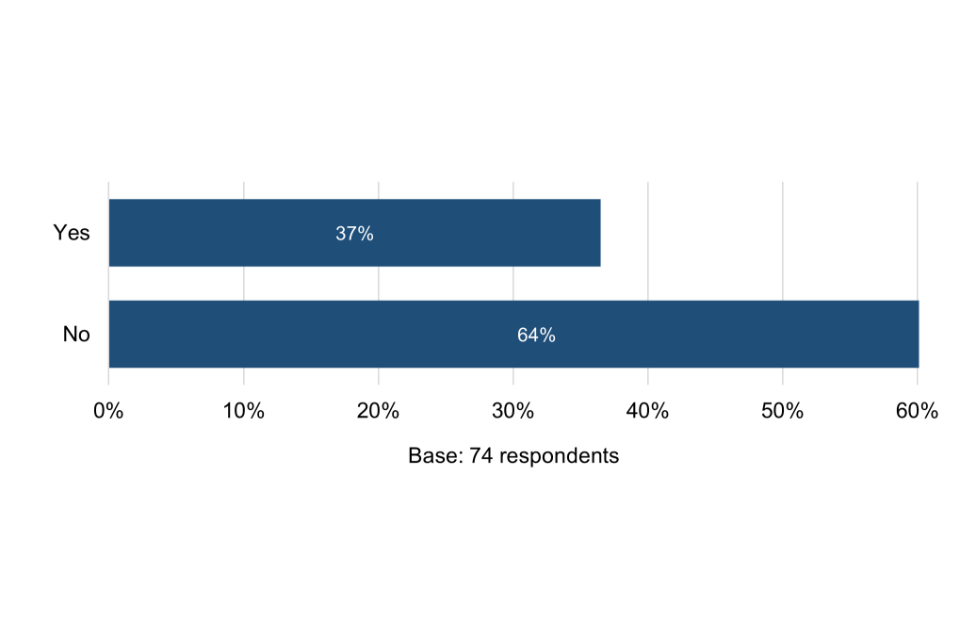

Almost two thirds (64%) of the 74 surveyed organisations that have never held Cyber Essentials had not heard of it prior to taking part in the survey. The vast majority had also not heard of other specified cyber security schemes or standards, which points to a potential target market for Cyber Essentials that may lack cyber security and an understanding of the importance of becoming more cyber secure.

Among 11 of these organisations that had hitherto heard of and considered taking up Cyber Essentials, their main reasons for not taking it up were that they considered it too time-consuming or lacking compatibility with different devices. These are issues that marketing, information and guidance could potentially help to address where there are misconceptions.

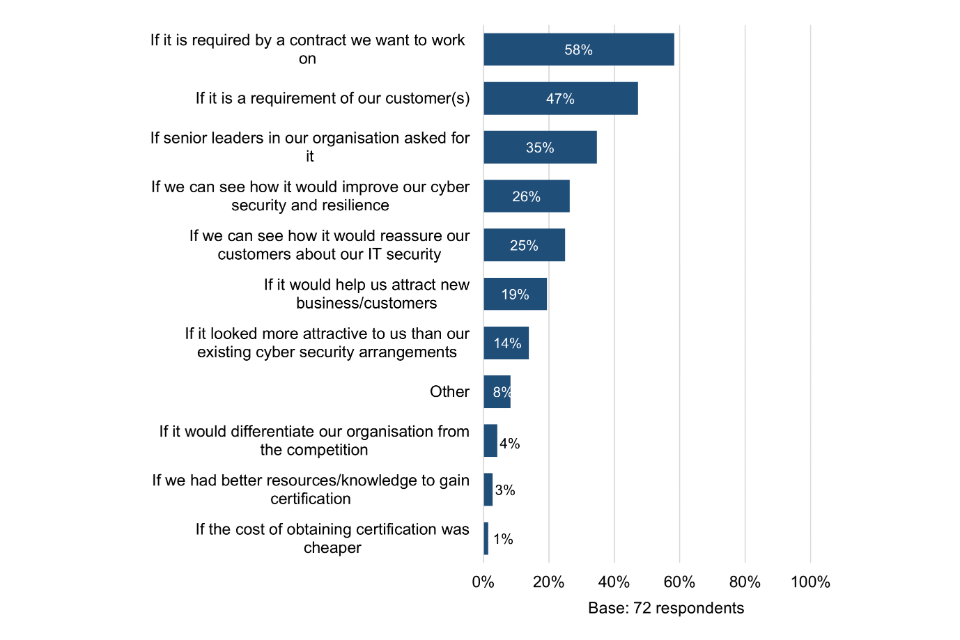

All 74 organisations were asked what would be needed for their organisation to consider obtaining Cyber Essentials certification in the future. The top three answers are primarily reactive, including: if it is required by a contract we want to work on (58%), if it is a requirement of our customer(s) (47%) and if senior leaders in our organisation asked for it (35%).

Many non-Cyber Essentials users indicated that they would be interested in finding out more about the scheme, had an open mind about it, would be willing to discuss it with their third-party IT providers (as appropriate) and, in some cases, are considering reviewing their cyber security needs in the near future. These responses indicate potential opportunities to improve awareness and understanding of Cyber Essentials in the market, including its value.

Conclusions

The following are top-level conclusions. More detail on each is provided in section 8.1.

-

The most common reasons for adopting Cyber Essentials are reactive rather than proactive, risking the scheme being perceived as a “hoop to jump through” in order to fulfil contract requirements.

-

Stronger focus should be placed on promoting the dangers and threats associated with conducting business online, so organisations can better appreciate why a cyber security solution such as Cyber Essentials is important.

-

There is evidence that the certification process is making a positive difference to users’ cyber behaviours, although there is a mixed picture concerning perceived value for money.

-

The cost and time inputs needed to go through the certification process vary widely between organisations, with high costs (including, but not limited to, scheme pricing) potentially affecting take-up and retention of Cyber Essentials certification.

-

Some of the largest and smallest organisations face substantial yet quite different obstacles to meeting the technical controls, indicating inherent challenges to the scheme’s prescriptive (i.e. rather than risk-based) and one-size-fits-all concept.

-

Updates to the technical control requirements are clearly important but communications about changes – especially major updates – appear to be inadequate and are not sufficiently timely for organisations to plan ahead.

-

Existing information and guidance could be improved with better tailoring and simplification for different types and sizes of organisation.

-

There is a clear market opportunity for Cyber Essentials among organisations that have never been certified under the scheme and which consider cyber security very important.

-

Anecdotal evidence points to pockets of weakness in the rigour of the Cyber Essentials assessment process. This could be overcome through education and guidance aimed at users in relation to cyber threats, risks and potential consequences, as well as the benefits of becoming more cyber resilient.

Recommendations

The following are top-level recommendations aimed at DSIT, IASME and NCSC to consider as part of a coordinated approach. More detail on each is provided in section 8.2.

1. Increase awareness and understanding about cyber security threats and provide users with an informed choice about the most appropriate solution for them.

a. Help to build a more foundational awareness among organisations of the importance of being cyber secure.

b. Develop more and better information about the features and benefits of the Cyber Essentials scheme in comparison to alternative schemes and standards.

c. Consider not mandating Cyber Essentials in public sector procurement contracts where suitable alternatives are already held.

2. Improve information, tools and guidance aimed at current and potential users.

a. Provide more and better information to articulate the differences between the standard and Plus schemes.

b. Produce more information and training resources via webinars, videos and infographics to help convey key aspects of the Cyber Essentials scheme.

c. Improve the clarity and simplicity of scheme information and guidance.

d. Produce and share best practice case studies on the customer journey.

e. Consider introducing an online chat interface.

f. Deploy user testing to help improve the clarity of assessment questions.

3. Provide more tailored information to different types and sizes of business, and consider more targeted and high-profile marketing and communications.

a. This could include tools to help organisations self-assess whether Cyber Essentials is right for their organisation and setting.

b. Consider a targeted marketing campaign to other key enablers in the cyber security space, such as IT support sector businesses.

c. Consider producing and running hard-hitting media adverts about the risks of a cyber breach – via television, radio or social media depending on the costs involved.

4. Consider the feasibility of adapting aspects of the Cyber Essentials scheme to be more responsive to current user needs.

a. Build in flexibilities where possible, especially those which would help large organisations and academic institutions to meet the technical controls.

b. Put in place a coordinated communications plan to more frequently and timeously distil information through Certification Bodies about changes and updates to control arrangements.

e. Explore further the relative merits of increasing the length of certification to three years, albeit with annual audits comparable to ISO 27001.

d. Allow more time for organisations to provide additional information in response to requests during the assessment process.

e. Review the scheme’s pricing structure, for example explore further whether the fee for assessment is a barrier to certification, or consider a more nuanced approach to assessment fees, such as a special rate for startups or lower reassessment costs at annual renewal.

5. Commit to strengthening scheme robustness and transparency

a. Consider how the scheme is positioned in relation to other NCSC schemes to ensure there is no risk of competing narratives.

b. Actively encourage organisations to provide regular feedback to IASME and NCSC.

c. Continue to work collaboratively with Certification Bodies towards greater consistency.

d. Consider an education campaign, potentially combined with more robust protocols to guard against organisations potentially providing false information in order to gain Cyber Essentials certification.

1. Introduction

This chapter sets the scene by explaining the UK government’s commitment to ensuring a cyber secure economy, providing background information about the government-backed Cyber Essentials scheme and how it works, and presenting the evaluation aims, objectives and methodology. It also presents a brief rundown of key evidence and statistics from approximately the last five years that are relevant to the process effectiveness of the Cyber Essentials scheme.

1.1 UK cyber resilience

The world is now more connected than ever before, with technology driving extraordinary opportunity, innovation and progress. However, the pace of change in the digital age also gives rise to additional complexity and risk.

The UK government is committed to making the UK the safest place in the world to be online and the best place in the world to start and grow a digital business. A key aspect of this is the government’s National Cyber Strategy (NCS) 2022 which sets out ambitious policies to protect the UK in cyberspace, backed by a £2.6 billion investment to put technology at the heart of plans for national security.

Under Pillar 2 of the Strategy – building a resilient and prosperous digital UK – the government has set the following objectives to 2025:

-

Improve the understanding of cyber risk to drive more effective action on cyber security and resilience

-

Prevent and resist cyber attacks more effectively by improving management of cyber risk within UK organisations and providing greater protection to citizens

-

Strengthen resilience at national and organisational level to prepare for, respond to and recover from cyber attacks

As part of this effort, the government aims to continue to promote take-up of accreditations and standards such as the Cyber Essentials certification scheme.

1.2 About Cyber Essentials

Cyber Essentials is a government-owned scheme that was developed to help organisations of all sizes defend against the most common cyber threats. It provides reassurance to organisations and their customers that systems are more resilient to basic cyber-attacks.

The scheme has three main functions, aimed at increasing the cyber resilience of the wider economy by raising the baseline of cyber security. These functions are:

-

To help organisations put in place fundamental technical controls that increase their resilience and build their confidence in their security posture

-

To enable organisations to manage third-party cyber security risks, receiving assurance from suppliers and partners that they have implemented core technical controls effectively

-

To provide Cyber Essentials certification for organisations in order to give assurance of basic cyber hygiene to the market (consumers, customers, suppliers and other business partners)

The purpose of implementing these measures is to significantly reduce an organisation’s vulnerability. Indeed, the government’s Procurement Policy Note 09/14 introduced a mandatory requirement for Cyber Essentials certification for organisations working on UK central government contracts to meet certain criteria, notably where this involves handling personal information and providing certain ICT products and services.

It should be noted that Cyber Essentials does not offer a silver bullet to protect against all cyber security risks. For example, it is not designed to address more advanced, targeted attacks, hence organisations facing these threats should consider additional measures as part of their security strategy. What Cyber Essentials does do is define a focused set of controls which offer cost-effective, basic cyber security for organisations of all sizes. It protects certified organisations against common cyber threats which are readily available for attackers to employ who themselves have little technical expertise.

There are two levels of certification:

-

Cyber Essentials: This is the basic verified self-assessment option. The scheme is centred around five technical controls designed to significantly reduce the impact of common cyber attack approaches.

Steps to certification typically involve working with a Certification Body to apply for an online assessment account, paying the relevant certification fee, completing the online assessment, and supporting documents, and submitting this information for review, resulting in the award of a certificate valid for one year.

-

Cyber Essentials Plus: Takes the same approach and aims to put the same protections in place but in this case, independent technical verification is also carried out by the Certification Body.

Throughout this report, the term Cyber Essentials is used to refer to the overall scheme (including both levels mentioned above) and the separate terms CE and CE Plus are used when referring to one particular level.

The five technical controls are:

-

Firewall configuration: Prevents unauthorised access to or from private networks

-

Secure configuration: Ensures that systems are configured in the most secure way for the needs of the organisation

-

User access control: Ensures that only those who should have access to systems access them at the appropriate level

-

Malware protection: Ensures that virus and malware protection is installed and up to date, including application ‘allow’ listing

-

Security update management: Ensures that the latest supported hardware, software and cloud services are used, and that the necessary patches supplied by vendors have been applied

The technical controls are reviewed on a 12-month rolling basis and ensure that the Cyber Essentials scheme continues to help UK organisations guard against the most common cyber threats. In 2022, a major update was made to the technical controls – the biggest since the scheme started in 2014. Updates to technical controls are published online with an ‘effective from’ date. All applications started on or after that date are subject to the new requirements and associated assessment questions.

Governance and delivery mechanisms

Cyber Essentials is a government scheme, operated in partnership between the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT)[footnote 3] and the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). It is delivered through the IASME Consortium Ltd. (IASME). The scheme launched on 5th June 2014 and, from April 2020, IASME became the NCSC’s sole Cyber Essentials partner responsible for the management and delivery of the scheme. Prior to that, it was delivered by five Accreditation Bodies, which included IASME.

Partnership meetings between IASME and NCSC take place once a quarter and create a platform to discuss the collaborative relationship and any strategic issues that may arise. These meetings are in addition to weekly business as usual meetings, marketing and communications meetings and customer service meetings. A technical working group is also in place to review and update the technical requirements of the scheme. The input of NCSC’s subject matter experts also helps to ensure Cyber Essentials controls align with evolving threats and attack vectors.

IASME has accredited over 300 Certification Bodies[footnote 4], comprising over 800 individual assessors, across the UK which are trained and licensed to certify organisations to the Cyber Essentials Scheme.

Latest available Cyber Essentials uptake data

The government wishes to increase the number of organisations holding Cyber Essentials. A total of 132,094 Cyber Essentials certificates have been awarded since the scheme began. IASME’s records (as of the end of May 2023) show a total of 27,027 unique Cyber Essentials certified organisations across the UK in the past 12 months, with 35,434 total certifications. The difference between the two figures denotes 8,407 CE Plus certifications which are counted additionally to CE.

Trend analysis shows steady growth, with fewer than 500 certifications issued per month in January 2017, rising to just under 3,500 in January 2023. In the calendar year of 2022, there were 24,300 CE certifications, of which 16,554 were recertifications and 7,746 new certifications. Since Cyber Essentials certification is renewed annually, the above figures do not take into account any that may have lapsed.

Monthly data from April 2021 also shows a steady growth in the number of accredited Certification Bodies, from 269 in April 2021 to 315 in January 2023.

Scheme developments

In November 2021, NCSC and IASME completed a major technical review of the scheme, the results of which informed the updated January 2022 requirements that make up the controls. The update includes revisions to the use of cloud services, as well as home working, multi-factor authentication, password management, security updates and more. Cyber Essentials-certified organisations are required to meet revised control requirements when seeking renewal of their Cyber Essentials certification.

NCSC recently launched a Funded Cyber Essentials Programme which, according to published information, offers “some small organisations in high-risk sectors” practical support at no cost to help put baseline cyber security controls in place. The initiative, funded by government and delivered by IASME, will see eligible organisations receive 20 hours of expert support to help implement the five technical controls needed to gain Cyber Essentials certification.

As part of another scheme, qualified Cyber Advisors will be able to offer consultancy services to help their customers understand and meet the five technical controls. Organisations who have a qualified Cyber Advisor on their staff will be able to apply to become an NCSC Assured Service Provider to deliver these services. It should be noted that NCSC will be looking to extend the scope of Cyber Advisor services to cover aspects of basic cyber security other than Cyber Essentials over the coming years.

Additionally, for large organisations with complex IT infrastructure, IASME is working with NCSC on a Pathways pilot project. Based on the typical risk scenario outlined above, Pathways offers a route to test the veracity of alternative technical controls an organisation may have implemented to protect itself from such commodity attacks. This will involve deploying a set of tests similar to a simulated attack and organisations that pass will achieve a Cyber Essentials Plus certificate. The results of the pilot are expected in the second quarter of 2023 with the potential for wider roll-out if deemed successful. The scheme is likely to be comparatively more expensive than Cyber Essentials Plus due to the more specialist expertise needed in the assessment stage.

1.3 Evaluation aims and objectives

In December 2022, the (then) Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), commissioned Pye Tait Consulting to undertake a process evaluation of the Cyber Essentials scheme. This is supplemented by a feasibility study for a subsequent impact evaluation to be conducted at a later date. The findings are intended to enable DSIT, NCSC and IASME to ascertain whether the current implementation approach is working and allowing the scheme to meet its objectives.

The evaluation objectives can be summarised as follows:

-

Identify organisations’ Cyber Essentials certification characteristics, decision-making and motivations for becoming Cyber Essentials certified

-

Explore organisations’ views on Cyber Essentials information and guidance

-

Understand how aspects of the Cyber Essentials customer journey work in practice

-

Determine how well the scheme is perceived to be operating

-

Offer suggestions for improving the scheme

-

Set out the feasibility for a possible subsequent impact evaluation

The feasibility study for a subsequent impact evaluation can be found in Appendix 1.

1.4 Methodology and participant numbers

The evaluation methodology comprised the following main components:

| Component | Details | Dates |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid desk research | To understand relevant policy, developments and existing research and evaluation findings in relation to Cyber Essentials | January 2023 |

| 12 qualitative strategic stakeholder interviews | Conducted with representatives from government and industry (UK, including devolved nations) as well as IASME, NCSC and a sample of former Accreditation Bodies | January 2023 |

| Online survey of Certification Bodies | 95 responses, representing a 30% response rate of the total population of 315 mailed Certification Bodies | 27 January – 17 February 2023 |

| Online survey spanning current and lapsed Cyber Essentials users | 528 responses (current users) 47 responses (lapsed users) |

27 January – 17 February 2023 |

| Small-scale phone survey of organisations that had never held Cyber Essentials | 74 responses | February 2023 |

The online survey of Certification Bodies was facilitated with the support of IASME.

The online survey link for current and lapsed users was sent by email to Certification Bodies for onward email distribution to their own users. It was also distributed by IASME to a further sample of users for which IASME held contact details and consent to take part in market research.

The phone survey of organisations that had never held Cyber Essentials (hereinafter referred to as non-Cyber Essentials organisations) was intentionally small-scale to provide a gauge of attitudes, perceptions and motivations among this audience to supplement evidence from those that had already been through the process.

Due to the protracted approach to distributing the online survey link to current and lapsed users, the total number invited to take part through Certification Bodies is not known. This prohibits a response rate being accurately calculated for these audiences.

Overall margins of error

Survey of Certification Bodies: Based on a population of 315 Certification Bodies, a total of 95 survey responses yields an overall margin of error for the survey of ±8.4% at the 95% confidence level.

Survey of current users: Based on a total count of 24,955 Cyber Essentials certified organisations in the month of survey launch (IASME, January 2023), a total of 528 survey responses from current users yields an overall margin of error for the survey of ±4.2% at the 95% confidence level.

Margins of error have not been calculated for the surveys of lapsed users and non-users since these surveys are very small scale and the findings should therefore be treated with extreme caution.

It should be noted that margins of error are inevitably higher for questions not answered by all respondents and where cross-tabulations of the results are performed.

1.5 About the presentation of findings in this report

This report presents the findings of the process evaluation by theme, with the perceptions of strategic stakeholders threaded throughout to complement survey insights on similar topics and questions.

Chapters 2 to 6 present the survey results using narrative descriptions and charts. These are supplemented (where applicable) by tables showing further breakdowns. Some questions were asked of all respondent groups (i.e. Certification Bodies, current and lapsed users) and some only of certain respondents.

The base number of respondents, along with the respondent groups applicable to a particular survey question, are shown in each chart. These appear either in the Y axis labels (to show bases per respondent group) or below the X axis (to show overall respondents) depending on the type of question.

Most survey results from current and lapsed users show cross-tabulations by employment size-band. This is on the assumption that organisation size is a key influencing criterion in relation to the opportunities and barriers to obtaining Cyber Essentials certification. Size-bands have been defined as follows:

-

Micro (fewer than 10 staff)

-

Small (10-49 staff)

-

Medium (50-249 staff)

-

Large (250+ staff)

There are a small number of exceptions where breakdowns by size-band are not displayed – either where this would require a substantial amount of tabulated data or where base numbers are low.

Statistical significance tests have been carried out on certain questions to assess whether differences in the distribution of results per size-band and per organisation type (Certification Bodies, current and lapsed users, as applicable) are due to chance or whether they represent meaningful differences between the groups. The term ‘significant’ is therefore used throughout this report to denote statistically significant differences.

Chapter 7 presents findings separately from the smaller number of organisations that have never held Cyber Essentials certification. For this cohort, not all results are expressed in percentage terms or using charts or tables, i.e. where the base number to a question falls below 40 responses.

A detailed breakdown of survey respondent numbers by different profiling characteristics (including employment size-band) can be found in Appendix 2.

The overarching evaluation questions, along with the two survey questionnaires aimed at: i) current and lapsed users; and ii) non-users of Cyber Essentials, are available as a separate Annex to this report.

1.6 Process effectiveness – evidence to date

A limited body of recent research relating to cyber resilience and cyber security measures has paid discrete attention to Cyber Essentials. This section summarises key findings from key recent publications where broadly relevant to this process evaluation.

In summary, existing research pays strong attention to aspects of Cyber Essentials awareness among users, motivations for becoming certified (including differences by size-band of organisation) and barriers to uptake. However, insights to date have been more limited with respect to the detail of the customer journey, helpfulness of support received, and views on how specific aspects of scheme processes could be strengthened. These are areas which this evaluation explores in particular detail, combining survey research that draws comparisons between different audience groups, combined with perceptions of strategic stakeholders.

Firstly, the Cyber Security Breaches Survey 2022 (based on responses from 1,243 businesses and 424 charities) found just 16% of surveyed businesses to be aware of Cyber Essentials. However, there has been a steady increase over the past seven years with awareness having doubled from 8% in 2017. Awareness as recorded by this survey is highest among large organisations (62%), followed by medium-sized organisations (49%) leading to the conclusion that more could be done to raise awareness of Cyber Essentials among small and micro organisations.

The Cyber Security Longitudinal Study is focused on medium and large businesses (50+ employees) and high-income charities (annual income of more than £1 million). The findings from Wave Two (December 2022, which surveyed 1,741 organisations) found an increase compared to Wave One (a year earlier) in the proportion of organisations certified to at least one of three standards asked about in the study: CE, CE Plus, or the ISO 27001 Standard for Information Security Management Systems. For example, between Wave One and Wave Two the proportion rose from 32% to 40% among businesses, and from 29% to 36% among charities. It found Cyber Essentials to be most often adhered to by businesses (25%) and charities (28%) compared to other certifications, with both shares higher than in Wave One.

The Review of Cyber Essentials influence on cyber security attitudes and behaviours in UK organisations (2020) involving 542 organisations, identified that Cyber Essentials-certified organisations were more likely than their non-certified counterparts to be:

-

Aware of the risks posed by cyber-attacks (including at a senior level)

-

Confident that they were protected from these attacks

-

Implementing cyber security controls, including taking steps beyond the technical controls required to become certified

-

Positive about the scheme, particularly its impact on customer and investor confidence

On the one hand, this suggests that messaging and processes through the Cyber Essentials scheme are making a tangible difference. However, the same research indicated that, for medium-sized and large organisations in particular, Cyber Essentials seemed to be reinforcing existing attitudes and behaviours rather than driving them.

A main indicated barrier to more organisations becoming certified was an apparent lack of knowledge about the scheme overall, including its costs and value. Another finding from the research among organisations that had yet to be certified was that a large minority felt that they were already following some or even all of the technical controls (with 25% claiming to follow all of them). Key recommendations from the above study included the need to improve awareness and knowledge of Cyber Essentials among non-certified businesses, encourage organisations to look for Cyber Essentials across their supply chains and use certification as an opportunity to drive other behaviours and awareness.

In their 2021 article A cyber situational awareness model to predict the implementation of cyber security controls and precautions by SMEs, Karen Renaud and Jacques Ophoff, citing sources, asserted that there are signs of improving awareness among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) of the cyber security domain. They argue that this “could be attributed to more focused cyber security awareness campaigns targeting SMEs”.

The same article describes the Cyber Essentials scheme as providing advice and certification, and the Cyber Aware campaign of providing sole traders and small businesses with a bespoke action plan to improve their cyber security. However, it adds, citing sources, that “there is an unwritten assumption that SMEs will seek out advice related to precautions to be taken from reliable sources”, which it says “is likely to be naïve”. It also highlights that SMEs can be unaware that the threats they are being warned about are relevant to them, whilst at the same time lacking resources to deal with them.

This evidence points to the theory – as noted by Steven Kemp (2022) in Exploring public cybercrime prevention campaigns and victimization of businesses: A Bayesian model averaging approach – that providing cyber security advice does not necessarily promote organisational behaviour change; there is a complex relationship between knowledge of threats and responses and changes in behaviour.

Osborn and Simpson (2017) in their journal article On small-scale IT users’ system architectures and cyber security: A UK case study highlighted how costs can impede smaller companies following standards designed to foster good cyber security practices. They specifically mentioned how business processes in smaller organisations and the perceived complexity of the Cyber Essentials programme could combine to limit uptake.

Renaud and Ophoff, in their (unpublished) 2021 report What is Preventing UK SMEs from taking Cyber Security Precautions?, identified the following obstacles to uptake:

Advice issues

-

Government advice not being useful

-

Too much advice

-

Uncertainty

-

Information avoidance

-

Poor understanding of strong password requirements

Perceptions

-

Realisation of need for more resources

-

Realisation of need for more support

-

Halo effect (a perception that current practices are so good that they cannot be improved upon)

-

Feeling insignificant

Social

-

No pressure from customers

-

Employees not supporting each other

In 2023, Vodafone published a report titled The business of cyber security: protecting SMEs in the changing world of work. Although this report does not include information regarding the sampling and survey methodology used, it asserts that with the cyber security risks faced by SMEs coming in various guises, help is needed, and that for some businesses, there is a real risk of loss of staff and even of business collapse. The report points to a lack of basic digital skills as well as a vast disconnect between how vulnerable most business leaders think they are and how vulnerable they are in reality.

Vodafone’s polling of over 400 SMEs shows the extent to which these organisations are currently experiencing attempted cyber attacks, the scale of the risk they pose and what – if anything – they are doing about it.

Key findings are summarised as follows:

-

Almost one in five (19%) of SMEs polled said that an average cyber attack deemed to cost £4,200 (a figure prompted to respondents based on an average taken from the Cyber Security Breaches Survey) would destroy their business

-

The majority (54%) had experienced an attempted cyber attack in the past 12 months

-

18% said their business was not protected with cyber security software and a further 5% did not know

-

Only 28% were aware of the Cyber Essentials scheme – with more SMEs saying they had heard of a cyber security product that does not actually exist

The report remarks that many SMEs are insufficiently persuaded or lack the knowledge and finance they need to put that protection in place. It adds that the government should do more to support the delivery of local cyber security skills and welcomes progress that has been made with the establishment of nine regional Cyber Resilience Centres (CRCs) across England and Wales.

Finally, the National Cyber Resilience Centre Group (NCRCG) is a not-for-profit company, funded and supported by the Home Office, in conjunction with policing and other partners. It aims to strengthen the reach of cyber resilience across the business community, particularly among SMEs and supply chains. The nine CRCs are mapped according to the location of each police Regional Organised Crime Unit. Each CRC retains regional leadership and the freedoms to deliver tailored, trusted and affordable support to local organisations.

2. Cyber Essentials decision-making

This chapter explores how Cyber Essentials certification has been implemented and managed by surveyed current and lapsed users of the scheme, including why they opted for a particular level of certification. It also looks at which other schemes and standards users have considered or taken up (with reasons), their main motivations for taking up Cyber Essentials and – where appropriate – why certification lapsed.

2.1 Characteristics of certification

Level of certification

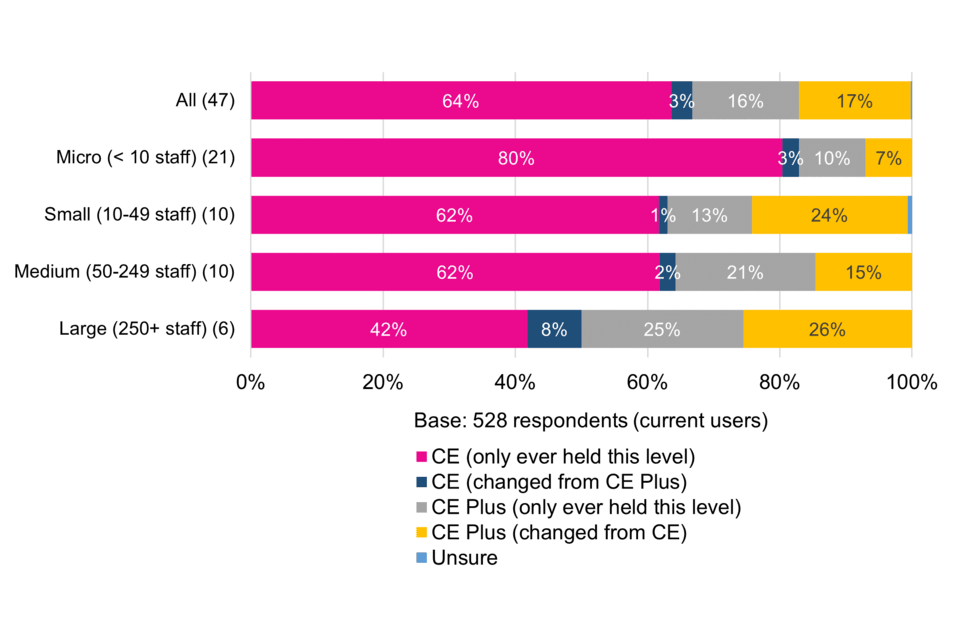

Firstly, looking at the levels of Cyber Essentials certification held by surveyed current users, CE is more common than CE Plus. Almost two thirds (64%) have only ever held CE, compared to less than a fifth (16%) who have only ever held Plus. There is a much stronger prevalence of users changing from CE to CE Plus than those changing from CE Plus to CE.

The proportion of micro organisations that have only ever held CE is significantly higher (80%) than other size-bands. Similarly, the proportion of large organisations that have only ever held CE Plus (a quarter, 25%) or changed to CE Plus (26%) is significantly higher than micro businesses (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Level of Cyber Essentials held (current users by size-band)

Figure 1

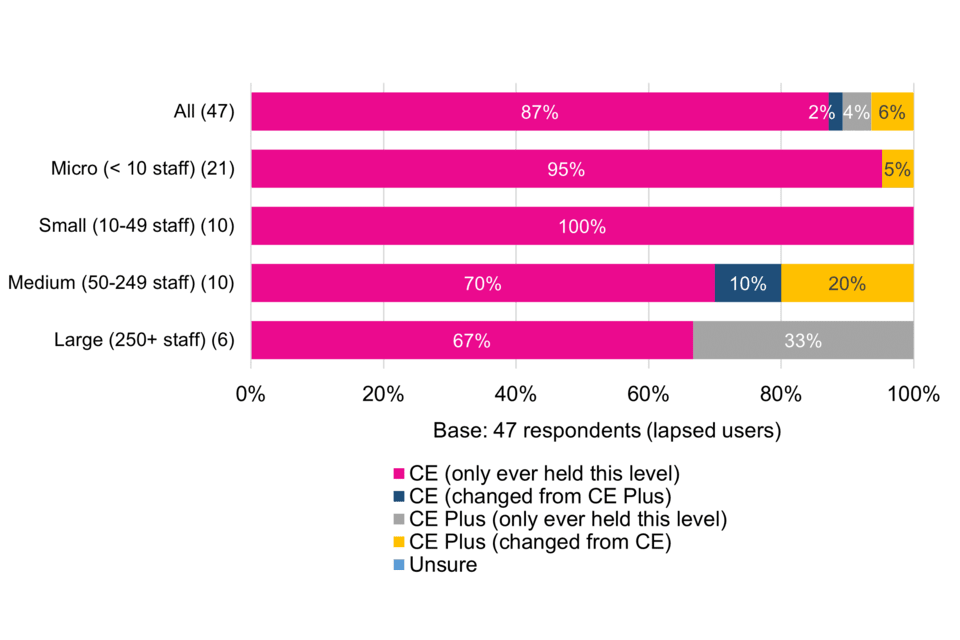

Among surveyed organisations whose Cyber Essentials certification has lapsed, the vast majority (87%) had only ever held the standard level. Among medium and large organisations whose certification lapsed, there is a greater prevalence of Plus having been previously held (the difference between large and micro organisations is significant).

A fifth (20%) of medium sized firms changed to CE Plus at some point before their certification lapsed, suggesting that this may only have been needed it for a certain period of time or that they did not wish to maintain it for another reason (Figure 2). Factors motivating organisations to take up certification or allow it to lapse are explored further in Chapter 3.

Figure 2 Level of Cyber Essentials previously held (by size-band)

Figure 2

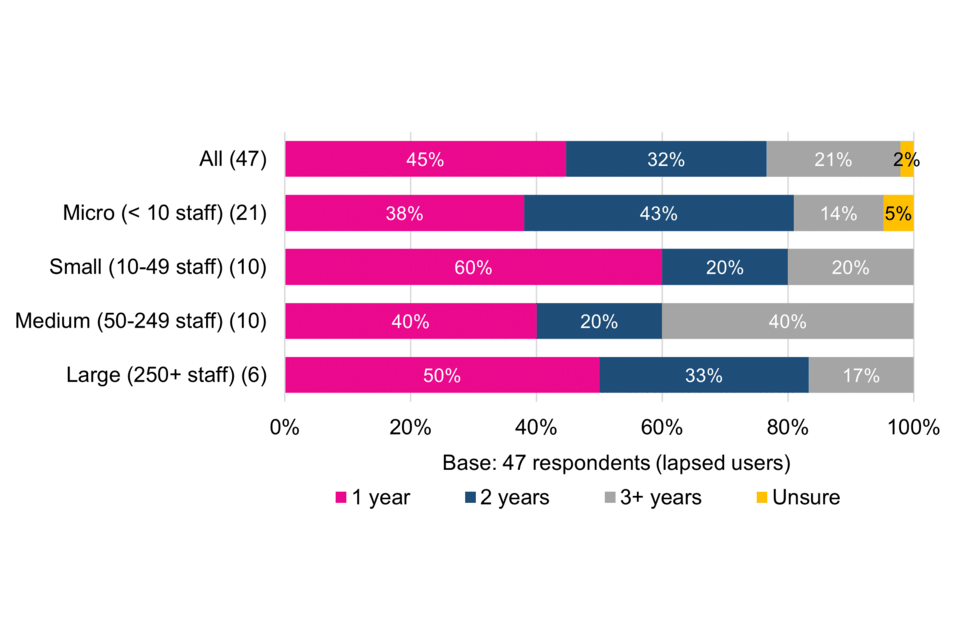

Length of time certification held

The small sample of lapsed users report having held their certification for varying lengths of time, with drop-offs highest after one year (45%) then 32% after two years and 21% after three or more years (Figure 3).

The pattern is similar across the size-bands. Whilst an above average 40% of surveyed medium sized organisations reported having held their certification for three or more years before it lapsed, this is not statistically significant given the low base numbers involved.

Figure 3 Total time Cyber Essentials certification previously held (by size-band)

Figure 3

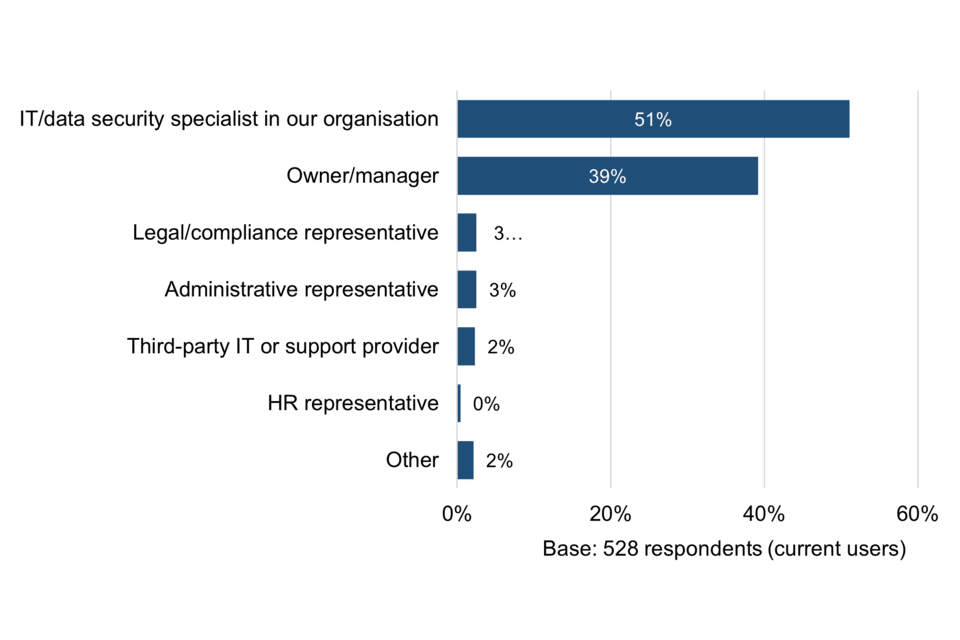

2.2 Responsibility for certification

Among organisations that currently hold Cyber Essentials, the vast majority (90%) assign overall responsibility for certification to either the owner or manager, or to the IT or information security specialist within their organisation (Figure 4). This could mean that these organisations are either confident in meeting the scheme’s requirements without the need for external consultancy support or would like help if they had access to it.

Figure 4 Assignment of Cyber Essentials overall certification responsibilities

Figure 4

Reported job roles classified as ‘Other’ include: associate; compliance; director (operations); director (industry solutions); project manager; service delivery manager; technical director.

Analysis by size-band reveals that, among micro businesses, overall responsibility for certification is far more commonly handled by the owner or manager – a significant difference compared with small, medium and large organisations. This is probably due to having less dedicated in-house IT support.

The larger the size-band of the organisation, the more common it is to place overall responsibility for Cyber Essentials certification in the hands of a dedicated in-house IT or data security specialist. For example, this occurs in 84% of large businesses compared with 17% of micro businesses compared – a significant difference (Table 1).

Table 1 Assignment of Cyber Essentials overall certification responsibilities (by size-band)

| Business function | All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49 staff) | Medium (50-249 staff) | Large (250+ staff) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 528 | 158 | 149 | 123 | 98 |

| IT/data security specialist in our organisation | 51% | 17% | 48% | 74% | 84% |

| Owner/manager | 39% | 76% | 36% | 19% | 11% |

| Legal/compliance representative | 3% | 1% | 4% | 2% | 3% |

| Administrative representative | 3% | 4% | 4% | - | - |

| Third-party IT or support provider | 2% | 2% | 3% | 2% | 1% |

| HR representative | 0% | - | 1% | 1% | - |

| Other | 2% | 1% | 5% | 2% | 1% |

2.3 Consideration and take-up of other schemes and standards

Several strategic stakeholders[footnote 5] interviewed for the research described Cyber Essentials as “lighter touch” than other schemes and standards relating to cyber security, such as ISO 27001 and NIST. The implicit message here is that the Cyber Essentials scheme’s intention of offering protection against common threats compares negatively against other schemes that are reportedly “offering stronger security”. This has implications for the Cyber Essentials scheme in terms of ensuring its intended position in the market is clear to prospective users, including what it does and does not do.

One stakeholder was complimentary about the scheme but added that you “get what you pay for”, arguing that larger organisations would typically only benefit from Cyber Essentials to meet an external requirement, especially if they already had stronger standards in place.

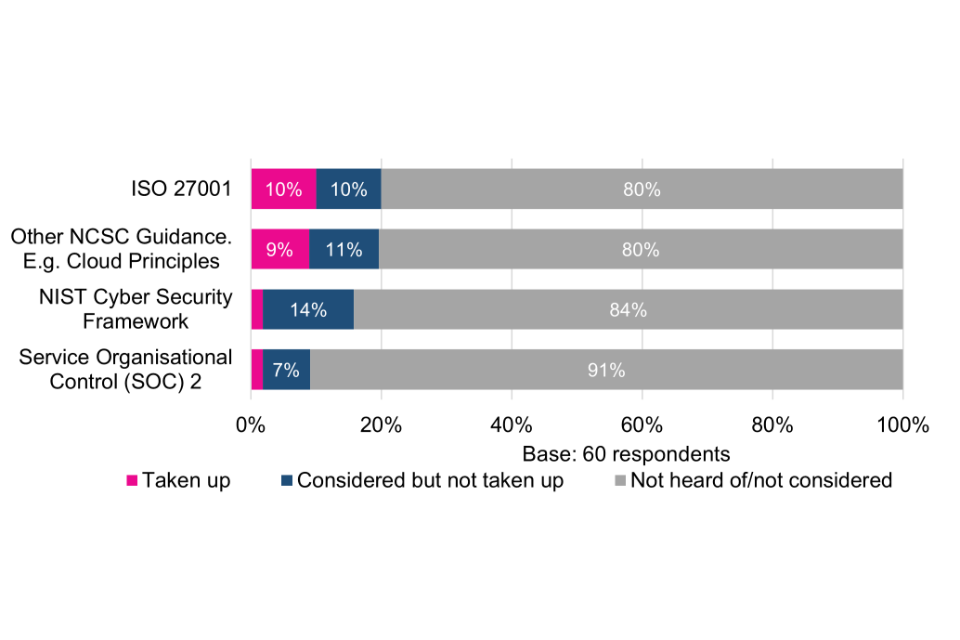

Current and lapsed Cyber Essentials users were asked which, from a list of other specific cyber security schemes, standards and principles, they had also considered or taken up. The proportions taking up or considering taking up the ISO 27001 standard on Information Security and Management are significantly higher than for the other listed schemes, standards and principles. Indeed, the majority had not heard of or considered each of the others (Figure 5).

The data suggests that Cyber Essentials could be providing a solution to a market that might not otherwise have considered another option. In cases where organisations hold more than one solution, e.g. Cyber Essentials in tandem with ISO 27001, this could mean that Cyber Essentials is complementary to other products. Conversely – and especially where Cyber Essentials is mandated in government contracts, as discussed in the next section – it could mean that some organisations feel no choice but to adopt both.

Figure 5 Consideration and take-up of other schemes and standards

Figure 5

The most common schemes and standards classified as ‘Other’ included: ISO 9001 (6 responses) IASME Cyber Assurance, also referred to by some respondents as IASME Governance (7 responses), CIS Critical Controls (5 responses), PCI-DSS (4 responses), ISO 27701 (2 responses) and NHS Digital Toolkit (2 responses).

Looking across the size-bands, the proportion of surveyed micro organisations that have taken up ISO 27001 is significantly lower than other size-bands, while the proportion of large organisations that have taken up NIST, NCSC Guidance and SOC 2 is significantly higher than some or all of the other size-bands in (Table 2). This suggests that comparatively larger organisations may be more cyber aware and more discerning in finding a solution that works for their organisation and operating context.

Table 2 Consideration of other schemes and standards (by size-band)

| ISO 27001 | All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49 staff) | Medium (50-249 staff) | Large (250+ staff) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taken up | 23% | 10% | 25% | 36% | 26% |

| Considered but not taken up | 56% | 56% | 50% | 50% | 70% |

| Not heard of/not considered | 22% | 35% | 25% | 14% | 4% |

| NIST Cyber Security Framework | All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49 staff) | Medium (50-249 staff) | Large (250+ staff) |

| Taken up | 6% | 5% | 2% | 4% | 14% |

| Considered but not taken up | 35% | 26% | 29% | 46% | 51% |

| Not heard of/not considered | 59% | 69% | 69% | 50% | 35% |

| Other NCSC Guidance. E.g. Cloud Principles | All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49 staff) | Medium (50-249 staff) | Large (250+ staff) |

| Taken up | 16% | 13% | 9% | 19% | 27% |

| Considered but not taken up | 25% | 17% | 27% | 27% | 36% |

| Not heard of/not considered | 59% | 70% | 64% | 55% | 37% |

| Service Organisational Control (SOC) 2 | All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49 staff) | Medium (50-249 staff) | Large (250+ staff) |

| Taken up | 3% | 1% | - | 3% | 9% |

| Considered but not taken up | 29% | 23% | 27% | 34% | 40% |

| Not heard of/not considered | 68% | 76% | 73% | 64% | 51% |

In comparing responses to the same question between current and lapsed Cyber Essentials users, the most notable difference between the two groups is that more than double the proportion of current users (24%) to lapsed users (11%) report having taken up ISO 27001 – a significant difference (Table 3).[footnote 6] However, it should be noted when looking at these results that there is no evidence that lapsed users are any more or less likely to have taken up other schemes or standards.

With the exception of ISO 27001, the majority within both groups had not heard of any of the other specified schemes, standards and principles before completing the survey. With respect to organisations that no longer hold Cyber Essentials, this could mean, for example, an increased exposure to cyber threats, or that they might have implemented the controls once and no longer feel that certification is necessary. The government, NCSC and IASME could potentially do more to help current users understand why a certain baseline level of cyber security is important.

Table 3 Consideration of other schemes and standards (by current and lapsed users)

| ISO 27001 | All | Current Cyber Essentials users | Lapsed Cyber Essentials users |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taken up | 23% | 24% | 11% |

| Considered but not taken up | 56% | 56% | 57% |

| Not heard of/not considered | 22% | 21% | 33% |

| NIST Cyber Security Framework | All | Current Cyber Essentials users | Lapsed Cyber Essentials users |

| Taken up | 6% | 6% | 5% |

| Considered but not taken up | 35% | 36% | 32% |

| Not heard of/not considered | 59% | 59% | 64% |

| Other NCSC Guidance. E.g. Cloud Principles | All | Current Cyber Essentials users | Lapsed Cyber Essentials users |

| Taken up | 16% | 15% | 21% |

| Considered but not taken up | 25% | 26% | 21% |

| Not heard of/not considered | 59% | 59% | 59% |

| Service Organisational Control (SOC) 2 | All | Current Cyber Essentials users | Lapsed Cyber Essentials users |

| Taken up | 3% | 2% | 5% |

| Considered but not taken up | 29% | 30% | 27% |

| Not heard of/not considered | 68% | 68% | 68% |

Views on how Cyber Essentials compares with other schemes or standards

Cyber Essentials is broadly regarded by users as a basic and accessible security standard compared to others. For example, many smaller organisations recognise that Cyber Essentials is cost-effective and sufficiently easy to obtain when balanced alongside the scale of their operations.

Unlike ISO 27001, [Cyber Essentials] sets an actual security standard (pass or fail) which is important. It is achievable for most organisations if they have the will and it’s not too expensive.

– Current user of Cyber Essentials, small employer, private business

[We were] pressured to become ISO 27001 [certified] but realised this was excessive. CE Plus was agreed as an acceptable alternative.

– Current user of Cyber Essentials, small employer, registered charity/trust

Opinion is more divided among large organisations. Some believe that Cyber Essentials provides a benchmark standard that companies ought to naturally strive for, even if considering other security schemes or standards such as ISO 27001. Others reflected on the differences between Cyber Essentials and alternative schemes, indicating that they each have their own place in the market.

Cyber Essentials helps set expectations for obtaining other certifications. Some of its policies and procedures are relevant in other schemes.

– Current user of Cyber Essentials, large employer, private business

Cyber Essentials is a well put together, functional and meaningful set of controls and helps our business develop, maintain and improve our cyber security posture.

– Current user of Cyber Essentials, large employer, private business

[It’s] different horses for different courses: ISO 27001 is risk based, externally audited, deeply embedded into [business as usual] management systems, governing all internet security related activity on a daily basis. Cyber Essentials is a point in time, pass or fail assessment based on NCSC norms.

– Current user of Cyber Essentials, large employer, private business

Where an organisation deems that it needs an alternative (for example ISO 27001) this raises the question that it could be placing an additional burden upon these organisations if they are also required to adopt Cyber Essentials as part of a procurement requirement.

Chapter 2 Summary Box

Among surveyed current and lapsed users, the standard CE certification is the most commonly held. CE Plus is more prevalent among large surveyed organisations, for which it accounts for just over half (51%) of certifications, compared to just 17% among micro organisations.

Among surveyed current and lapsed users, the standard CE certification is the most commonly held. CE Plus is more prevalent among large organisations, for which it accounts for just over half (51%) of certifications, compared to just 17% among micro organisations.

The small sample of lapsed users had held their certification for varying lengths of time, with drop-offs highest after the first year (45%) then 32% after two years and 21% after three or more years.

Among micro organisations, overall responsibility for certification is most commonly handled by the owner or manager. The larger the size-band of the organisation, the more common it is to place overall responsibility for Cyber Essentials certification in the hands of a dedicated in-house IT or data security specialist.

With the exception of the ISO 27001 standard on Information Security and Management, which more than half (56%) of Cyber Essentials users had considered and a further 23% taken up, most had not heard of or considered other specific schemes and standards asked about in the survey.

Some organisations believe that Cyber Essentials provides a benchmark standard that companies ought to naturally strive for, even if considering other security schemes or standards such as ISO 27001. Others reflected on the differences between Cyber Essentials and other schemes, indicating that they each have their own place in the market.

Qualitative insights reveal that Cyber Essentials is broadly regarded by users as a basic and accessible security standard compared to other schemes or standards. However, large organisations in particular expressed the view that ISO 27001 is more rigorous and appropriate to their setting.

3. Factors driving Cyber Essentials certification

3.1 Motivations for taking up Cyber Essentials

Strategic stakeholders (representatives from government and industry) interviewed for the research view the main motivations for organisations becoming Cyber Essentials certified as:

-

Being a commercial requirement (where mandated by government contracts)

-

Cyber Essentials being considered a simpler, more straightforward and cheaper solution than ISO 27001 and the NIST Cyber Security Framework

-

To help grow their business

-

To make a big difference to their cyber resilience (for smaller organisations)

One stakeholder observed that the reputational benefit associated with having the Cyber Essentials badge on their website does not appear to be as prominent now as it was a few years ago. This could be due to Cyber Essentials take-up gaining ground, becoming more established in the market and increasingly being seen as a must-have – especially for those working on government contracts.

Reasons for first becoming Cyber Essentials certified

A range of factors are behind why surveyed organisations chose to become Cyber Essentials certified. Some of these react to the needs of other organisations, while others serve to benefit the organisation becoming certified proactively.

The three most popular responses are: to reassure customers about IT security (51%), to improve cyber security and resilience (48%) and to meet public sector contract requirements (46%). (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Reasons for first becoming Cyber Essentials-certified

Figure 6

The most common responses classified as ‘Other’ include: to meet insurance requirements, being part of a pilot programme and as a speculative or learning opportunity to see what Cyber Essentials was like.

Analysis by size-band reveals that the proportion of small, medium and large organisations motivated to take up Cyber Essentials to improve their own cyber security and resilience is significantly higher than among micro businesses (Table 4). Once again, this suggests that more could be done to help the smallest organisations understand why they should be more cyber secure, including how Cyber Essentials goes beyond off-the-shelf anti-virus software, and the risks and consequences of not having a suitable baseline level of security in place.

Table 4 Reasons for first becoming Cyber Essentials-certified (by size-band)

| All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49 staff) | Medium (50-249 staff) | Large (250+ staff) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 575 | 179 | 159 | 133 | 104 |

| To reassure customers about our IT security | 51% | 42% | 57% | 59% | 48% |

| To improve our cyber security and resilience | 48% | 34% | 60% | 50% | 52% |

| It was a public sector contract requirement | 46% | 48% | 42% | 46% | 49% |

| To help us attract new business/customers | 30% | 27% | 37% | 26% | 28% |

| It was a customer requirement | 27% | 22% | 31% | 26% | 28% |

| To differentiate us from the competition | 24% | 24% | 30% | 23% | 16% |

| It was a private sector contract requirement | 13% | 11% | 11% | 15% | 19% |

| Senior leaders in our organisation asked for it | 12% | 6% | 15% | 13% | 18% |

| Seemed the best solution on the market | 8% | 5% | 12% | 8% | 6% |

| Was the cheapest solution on the market | 2% | 5% | 1% | 2% | 1% |

| Other | 4% | 2% | 3% | 8% | 4% |

Cyber Essentials and Plus help to ‘open doors’ to opportunities for partnerships and research engagement.

– Current user of Cyber Essentials, large employer, academic institution

[It’s important] to show that despite being a small business we are capable of [performing] as well as any larger business.

– Current user of Cyber Essentials, micro employer, private business

Further analysis on this question by type of organisation reveals that surveyed private sector businesses were comparatively less inclined to pursue Cyber Essentials to improve their own cyber security and resilience than other organisation types. Some 44% of private businesses selected this option compared to more than three quarters of registered charities and trusts, non-governmental organisations, and national or local government.

Two thirds of academic institutions (66%) said they were motivated to take up Cyber Essentials because it was a requirement of a public sector contract – the highest percentage across all organisation types and compared to 46% on average.

The vast majority of registered charities and trusts regard Cyber Essentials positively, irrespective of size.

It’s an achievable and recognised framework, at a reasonable cost.

– Current user of Cyber Essentials, medium employer, registered charity/trust

I like Cyber Essentials due to its NCSC connections which I think give it more weight as a scheme.

– Current user of Cyber Essentials, medium employer, registered charity/trust

Single main reason for first becoming Cyber Essentials certified

All surveyed organisations were asked to narrow their choice of motivating factors down to one main reason for first becoming Cyber Essentials certified. Again, a range of reasons were given, although the most common (mentioned by just over a third, 34%) is that Cyber Essentials was a requirement of a public sector contract (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Single main reason for first becoming Cyber Essentials-certified

Figure 7

Looking across the size-bands, the most common reason for taking up Cyber Essentials in all cases is that it was a public sector contract requirement (Table 5). Larger organisations seem more likely to seek certification due to an internal motivation to improve their cyber security, whereas smaller organisations appear more focused on the benefit of reassuring customers. Indeed, the proportion of large, medium and small organisations motivated to take up Cyber Essentials to improve their own cyber security and resilience is significantly higher than among micro businesses.

Table 5 Single main reason for first becoming Cyber Essentials-certified (by size-band)

| All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49 staff) | Medium (50-249 staff) | Large (250+ staff) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base | 574 | 179 | 159 | 132 | 104 |

| It was a public sector contract requirement | 34% | 40% | 30% | 33% | 35% |

| To improve our cyber security and resilience | 18% | 10% | 20% | 19% | 28% |

| To reassure customers about our IT security | 17% | 20% | 20% | 18% | 9% |

| It was a customer requirement | 12% | 12% | 9% | 11% | 14% |

| It was a private sector contract requirement | 7% | 6% | 7% | 9% | 8% |

| To help us attract new business/customers | 5% | 8% | 7% | 2% | 3% |

| Other | 3% | 2% | 1% | 7% | 2% |

| To differentiate us from the competition | 1% | 2% | 3% | - | - |

| Senior leaders in our organisation asked for it | 1% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Seemed the best solution on the market | 1% | - | 2% | 1% | - |

| Was the cheapest solution on the market | 0% | 1% | - | - | - |

Importance of specific factors in becoming Cyber Essentials certified

Current and lapsed users were asked how important each of four particular factors were as part of their decision-making process to take up Cyber Essentials (Figure 8).

The majority considered all four factors to be very or quite important, especially understanding the ‘perceived benefits of becoming Cyber Essentials certified’. Logistical inputs in terms of expertise, resources and cost are all clearly important, making it essential that organisations are clear from information and guidance what is expected of them as part of the certification process (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Importance of specific factors in decision-making process to take up Cyber Essentials

Figure 8

Analysis by size-band reveals that the majority of organisations per band consider each of these factors to be very or quite important (Table 6).

However, there are significant differences by size-band on the matter of cost, with smaller organisations appearing to be much more cost sensitive. For example, the proportion of micro organisations viewing cost as very important (32%) is significantly higher than small, medium and large organisations. Furthermore, the proportion of large organisations describing cost as not very or not at all important (57%) is significantly higher than the other size-bands.

Table 6 Importance of specific factors in decision-making to take up Cyber Essentials (by size-band)

| Perceived benefits of becoming Cyber Essentials certified | All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49) | Medium (50-249) | Large (250+) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very important | 48% | 44% | 54% | 49% | 48% |

| Quite important | 34% | 34% | 30% | 37% | 39% |

| Not very important | 9% | 8% | 11% | 11% | 8% |

| Not at all important | 6% | 12% | 4% | 2% | 4% |

| Unsure | 2% | 2% | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Establishing the expertise needed to become Cyber Essentials certified | All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49) | Medium (50-249) | Large (250+) |

| Very important | 26% | 26% | 30% | 24% | 22% |

| Quite important | 45% | 41% | 43% | 51% | 45% |

| Not very important | 19% | 17% | 15% | 19% | 26% |

| Not at all important | 9% | 14% | 11% | 5% | 5% |

| Unsure | 1% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 2% |

| Establishing other inputs/resources needed to become Cyber Essentials certified | All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49) | Medium (50-249) | Large (250+) |

| Very important | 24% | 23% | 26% | 20% | 31% |

| Quite important | 41% | 37% | 47% | 44% | 37% |

| Not very important | 23% | 23% | 20% | 29% | 23% |

| Not at all important | 9% | 14% | 7% | 5% | 8% |

| Unsure | 2% | 3% | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Cost of certification | All | Micro (< 10 staff) | Small (10-49) | Medium (50-249) | Large (250+) |

| Very important | 22% | 32% | 21% | 19% | 11% |

| Quite important | 39% | 35% | 47% | 43% | 31% |

| Not very important | 26% | 22% | 22% | 26% | 37% |

| Not at all important | 12% | 10% | 9% | 12% | 20% |

| Unsure | 1% | 2% | 2% | - | 2% |

When asked what other factors (if any) played a part in their decision to take up Cyber Essentials, the majority of current and lapsed clients took the opportunity to re-emphasise the importance of meeting contractual, funding or tender requirements. Linked to this, many reiterated the point that Cyber Essentials is often a requirement for public sector work and is often listed as desirable, if not mandatory, for other types of work.

Additional factors important for organisations in deciding whether to take up Cyber Essentials include demonstrating good business practices and standards, and remaining competitive and improving security in a cost-effective way, including with low entry and maintenance requirements.

3.2 Rationale for the choice of certification level

The most prominent reason for surveyed current and lapsed users opting for CE as opposed to CE Plus was no obvious need for CE Plus (65% of respondents) followed by CE Plus being perceived as too time-consuming (37%) and too expensive (35%) (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Reasons for preferring CE over CE Plus

Figure 9

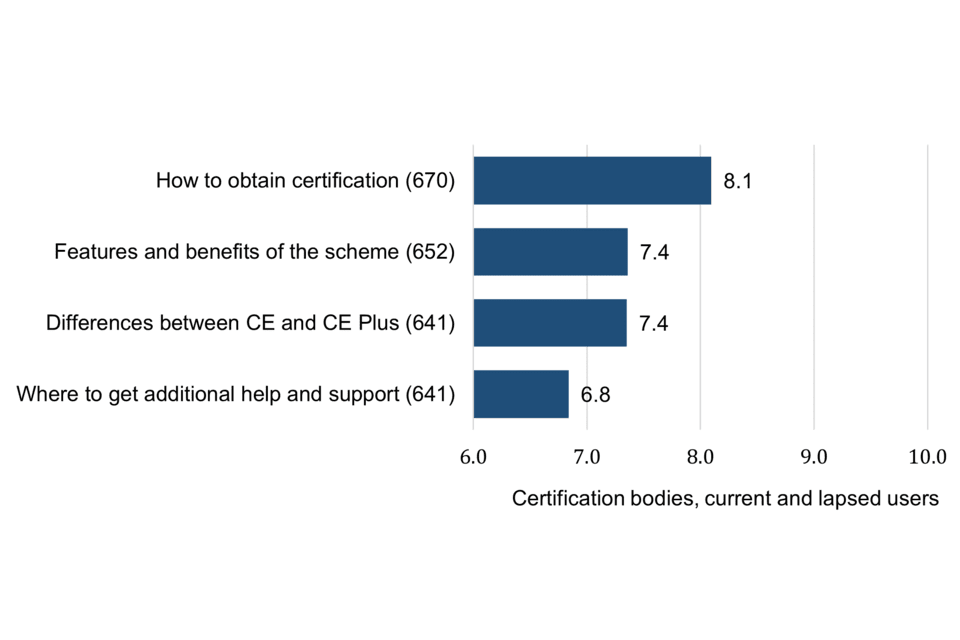

Responses categorised as ‘Other’ include: perceived challenges and difficulties around passing the audit; wanting to take Cyber Essentials one step at a time and not being ready yet for Plus (but often with the ambition to raise the level); Plus not being required by users or contractors; and not wanting to share data with a third party.